to download the event program - 2011 - Perth International Arts ...

to download the event program - 2011 - Perth International Arts ...

to download the event program - 2011 - Perth International Arts ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

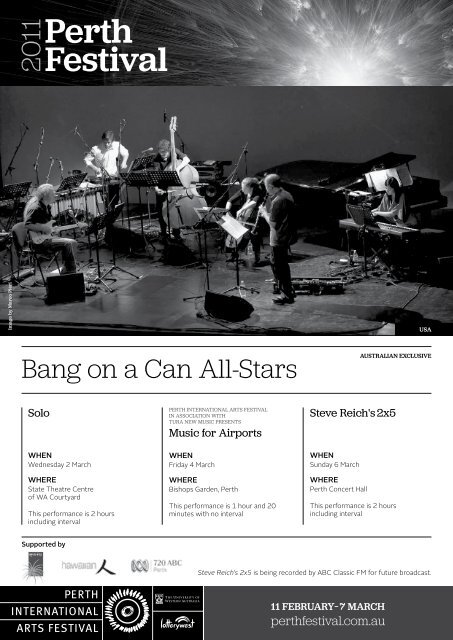

Image by Marco Pieri<br />

USA<br />

Bang on a Can All-Stars<br />

AUSTRALIAN EXCLUSIVE<br />

Solo<br />

WHEN<br />

Wednesday 2 March<br />

WHERE<br />

State Theatre Centre<br />

of WA Courtyard<br />

This performance is 2 hours<br />

including interval<br />

<strong>Perth</strong> INTERNATIONAL <strong>Arts</strong> Festival<br />

in association with<br />

tura new music presents<br />

Music for Airports<br />

WHEN<br />

Friday 4 March<br />

WHERE<br />

Bishops Garden, <strong>Perth</strong><br />

This performance is 1 hour and 20<br />

minutes with no interval<br />

Steve reich's 2x5<br />

WHEN<br />

Sunday 6 March<br />

WHERE<br />

<strong>Perth</strong> Concert Hall<br />

This performance is 2 hours<br />

including interval<br />

Supported by<br />

Tura Logo<br />

Steve Reich's 2x5 is being recorded by ABC Classic FM for future broadcast.<br />

11 February– 7 March<br />

perthfestival.com.au

2<br />

BANG ON A CAN ALL-STARS<br />

Ashley Bathgate<br />

Robert Black<br />

Vicky Chow<br />

David Cossin<br />

Mark Stewart<br />

Evan Ziporyn<br />

Cello<br />

Bass<br />

Piano and Keyboards<br />

Percussion<br />

Electric Guitar<br />

Clarinets<br />

Founded in 1992 by Bang on a Can co-founders Michael<br />

Gordon, David Lang and Julia Wolfe, Bang on a Can All-Stars<br />

quickly forged a distinct identity and have come <strong>to</strong> be known<br />

world-wide for <strong>the</strong>ir ultra-dynamic live performances and<br />

recordings of <strong>to</strong>day’s most innovative music.<br />

A new generation of virtuosic and passionate performers was<br />

needed <strong>to</strong> make this music come alive. These new players<br />

needed new skills. They had <strong>to</strong> be able <strong>to</strong> cross musical<br />

boundaries and be at home with many styles and technologies.<br />

And <strong>the</strong>y had <strong>to</strong> be amazing. Michael, David and Julie quickly<br />

started assembling a core of such exciting, dedicated and<br />

versatile players, and <strong>the</strong>se performers started showing up<br />

with regularity from festival <strong>to</strong> festival. Out of this core, in<br />

1992, <strong>the</strong>y assembled <strong>the</strong> Bang on a Can All-Stars.<br />

The instrumentation itself shows <strong>the</strong> aes<strong>the</strong>tic intention for<br />

which <strong>the</strong> All-Stars were designed. Clarinets, cello, keyboard,<br />

electric guitar, bass, and drums – it is part rock band and part<br />

amplified chamber group. Constructed specifically <strong>to</strong> blur<br />

<strong>the</strong> lines between classical and pop ensembles, <strong>the</strong> line-up<br />

was chosen <strong>to</strong> give voice <strong>to</strong> a huge range of music and styles,<br />

and <strong>the</strong> players have <strong>the</strong> musical backgrounds and abilities<br />

<strong>to</strong> match. Each player is completely at home with new music<br />

but has lived somewhere else as well – collaborating with<br />

Yo-Yo Ma, leading a gamelan, backing Mikhail Baryshnikov,<br />

<strong>to</strong>uring with Paul Simon and Bob Dylan. The players bring <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

o<strong>the</strong>rworldly experiences back <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir life with <strong>the</strong> All-Stars,<br />

and <strong>the</strong>ir mixing creates an intense, hard-rocking approach <strong>to</strong><br />

performance that no o<strong>the</strong>r group can match.<br />

Like <strong>the</strong> Bang on a Can Festival, <strong>the</strong> All-Stars have a<br />

powerful mission – <strong>to</strong> give <strong>the</strong> most persuasive and exciting<br />

performances of <strong>the</strong> most genre-defying music in <strong>the</strong><br />

world. They go about <strong>the</strong>ir mission in a few different ways<br />

– by performing and recording definitive versions of <strong>the</strong><br />

groundbreaking music of our day, by working closely with a<br />

diverse assortment of musical masters from our and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

cultures, and by commissioning actively new works from both<br />

<strong>the</strong> unknown and <strong>the</strong> famous, from all walks of musical life.<br />

Toge<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong> All-Stars have worked in unbelievably close<br />

collaborations with some of <strong>the</strong> most important musicians of<br />

our time, including Philip Glass, Steve Reich, Meredith Monk,<br />

Brian Eno, Ornette Coleman, Sonic Youth’s Thurs<strong>to</strong>n Moore,<br />

Don Byron, Burmese circle drum master Kyaw Kyaw Naing, Iva<br />

Bit<strong>to</strong>va, Nobukazu Takemura, Terry Riley, Glenn Branca, Cecil<br />

Taylor, DJ Spooky and Louis Andriessen. The All-Stars have<br />

formed lasting relationships with many of <strong>the</strong>se musicians,<br />

commissioning and performing <strong>the</strong>ir works, recording <strong>the</strong>m<br />

and <strong>to</strong>uring <strong>the</strong>m all over <strong>the</strong> world.<br />

The All-Stars are one of <strong>the</strong> most active <strong>to</strong>uring contemporary<br />

ensembles, on <strong>the</strong> road for much of <strong>the</strong> year in such venues<br />

as Carnegie Hall, <strong>the</strong> Venice Biennale, <strong>the</strong> Holland Festival,<br />

The Next Wave Festival at <strong>the</strong> Brooklyn Academy of Music,<br />

<strong>the</strong> Sydney Olympics, UCLA’s Royce Hall, London’s Barbican<br />

Center, Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall and Paris’s Theatre<br />

De La Ville and appearing as regulars at numerous festivals<br />

in Italy, Scandinavia and throughout Eastern Europe. They<br />

are also active in <strong>the</strong> recording studio, with discs on awardwinning<br />

discs on Cantaloupe and Nonesuch, and a certified<br />

hit on Point, <strong>the</strong>ir live reconstruction of Brian Eno’s ambient<br />

landmark Music for Airports.<br />

The Bang on a Can All-Stars, with <strong>the</strong>ir unparalleled musicality,<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir international <strong>to</strong>uring, award-winning CDs and far-ranging<br />

commissioning <strong>program</strong>s, have become one of <strong>the</strong> most<br />

powerful ambassadors for contemporary music in <strong>the</strong> world.<br />

For all <strong>the</strong>ir efforts, Musical America recognised <strong>the</strong> All-Stars<br />

in 2004 as Ensemble of <strong>the</strong> Year. ‘One of <strong>the</strong> most visceral<br />

performing groups around,’ <strong>the</strong> Independent raved.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> 21st century, <strong>the</strong> All-Stars continue <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

ambassadorship, bringing <strong>the</strong>ir brand of beauty <strong>to</strong> concert halls<br />

across <strong>the</strong> world. ‘We roll in<strong>to</strong> <strong>to</strong>wn with a fantastic <strong>program</strong> of<br />

semi-popular music, and people come,’ explains guitarist Mark<br />

Stewart. ‘They don’t know what it is, and <strong>the</strong>y say afterwards,<br />

‘What is this? Why don’t we hear this more? Who are you?<br />

Where did you come from? Is <strong>the</strong>re more music like this?’ It’s a<br />

little bit like <strong>the</strong> Lone Ranger. ‘Who are you masked man?’ ‘Our<br />

work here is done. We must move on.’’<br />

http://bangonacan.org/<br />

Image by Christine Southworth

3<br />

Tom Johnson<br />

Failing<br />

A former music critic at Village Voice, Tom Johnson is a<br />

conceptual composer with a provocative wit who highlights<br />

odd aspects of <strong>the</strong> music world and uses <strong>the</strong>m <strong>to</strong> make a<br />

piece. ‘Failing was written in 1975 at a time when composers<br />

were writing impossible music <strong>to</strong> play, so complex and<br />

involved,’ says soloist Robert Black. ‘I feel Tom is making a<br />

comment on that his<strong>to</strong>rical moment in new music, parodying<br />

that whole impossible music <strong>to</strong> play.’<br />

Image by Stephanie Berger<br />

SOLO<br />

The individual All-Stars show <strong>the</strong>ir stunning<br />

virtuosity in a <strong>program</strong> of solo performances.<br />

WHEN<br />

Wednesday 2 March<br />

This performance is 2 hours including an interval<br />

WHERE<br />

State Theatre Centre of WA Courtyard<br />

Steve Reich (born 1936) Electric Counterpoint (1987)<br />

Tom Johnson (born 1939) Failing (1975)<br />

Andy Akiho (born 1979) Vick(i/y) (2008)<br />

David Cossin (born 1972) A.C.T.<br />

INTERVAL<br />

David Lang (born 1957) Press Release (1991)<br />

Michael Gordon (born 1956) Industry (1993)<br />

Evan Ziporyn (born 1959) Be in (1991)<br />

ROBERT BLACK<br />

Andy Akiho<br />

Vick(i/y)<br />

Vick(i/y) is a solo prepared piano work that uses audi<strong>to</strong>ry and<br />

structural palindromes throughout <strong>the</strong> work <strong>to</strong> symbolise <strong>the</strong><br />

subtle differences that lie beneath an assumed symmetrical<br />

structure or state of being. The bell-like preparation notes<br />

of diminishing pulses, which are continuously interrupted by<br />

<strong>the</strong> conventional notes, represent a consistent, yet fading<br />

image of a forgotten dream. My goal was <strong>to</strong> create a miniature<br />

percussion ensemble with <strong>the</strong> piano by incorporating extended<br />

instrument preparation and composition techniques inspired by<br />

John Cage, George Crumb, Béla Bartók and Jacob Druckman.<br />

The piece was written for and dedicated <strong>to</strong> Vick(i) Ray and<br />

Vick(y) Chow, two amazing contemporary pianists who have<br />

been a major musical inspiration for me over <strong>the</strong> past two<br />

years. It was composed in Oc<strong>to</strong>ber 2008 and premiered by<br />

Chow on November 1 at The S<strong>to</strong>ne in New York City. Ray gave<br />

<strong>the</strong> West Coast premiere in 2009.<br />

Note by Andy Akiho<br />

David Cossin<br />

A.C.T.<br />

A.C.T. (Amplified Cardboard Tube) is as much as a piece as it<br />

is an instrument. A.C.T. is a structured improvisation. Through<br />

amplifying this found instrument using control feedback I can<br />

create a singing drum. And I can accompany myself with a real<br />

time looping sampler (Echoplex) that records instantaneously<br />

what I play.<br />

Note by David Cossin<br />

David Lang<br />

Press Release<br />

I wrote Press Release in 1991 for Evan Ziporyn. When you<br />

compose for one person, you can’t get all <strong>the</strong> colours that you’d<br />

have with an ensemble or orchestra, so you have <strong>to</strong> imagine<br />

some sort of interesting problem. I wanted <strong>to</strong> do something<br />

that was really rhythmic. The original idea behind this piece<br />

BANG ON A CAN FOUNDERS<br />

Steve Reich<br />

Electric Counterpoint<br />

Electric Counterpoint was originally composed for guitarist<br />

Pat Me<strong>the</strong>ny as <strong>the</strong> third in a series of pieces (first Vermont<br />

Counterpoint for flute followed by New York Counterpoint<br />

for clarinet) all dealing with a soloist playing against a prerecorded<br />

tape of <strong>the</strong>mselves. In Electric Counterpoint <strong>the</strong><br />

soloist pre-records as many as ten guitars and two electric<br />

bass parts and <strong>the</strong>n plays <strong>the</strong> final 11th guitar part live against<br />

<strong>the</strong> tape. I would like <strong>to</strong> thank Pat Me<strong>the</strong>ny for showing me<br />

how <strong>to</strong> improve <strong>the</strong> piece in terms of making it more idiomatic<br />

for <strong>the</strong> guitar.<br />

Note by Steve Reich<br />

Image by Peter Serling<br />

DAVID LANG<br />

MICHAEL GORDON<br />

JULIA WOLFE

4<br />

was that of a high melody alternating with a low bass line, so<br />

that you get a high pop and a low pop switching back and forth<br />

as fast as possible, and <strong>the</strong>se two worlds coexist. I wanted <strong>the</strong><br />

upper melody <strong>to</strong> be recognisable and <strong>the</strong> bot<strong>to</strong>m bass line <strong>to</strong><br />

be recognisable, <strong>to</strong> be a real bass line, a driving funk thing. In<br />

classical music, <strong>the</strong> bass is only <strong>the</strong>re <strong>to</strong> support <strong>the</strong> melody,<br />

which is where <strong>the</strong> action is. But <strong>the</strong> bass line is <strong>the</strong> place where<br />

funk music really shines. Who has <strong>the</strong> best bass lines in <strong>the</strong><br />

business? I am a big James Brown fan, and, I thought, if you want<br />

a bass line, you got <strong>to</strong> go <strong>to</strong> James. So I made <strong>the</strong> key changes<br />

sound like James Brown. Because of <strong>the</strong> way <strong>the</strong> bass clarinet<br />

works, I thought you’d have <strong>to</strong> press <strong>the</strong> keys down <strong>to</strong> make all<br />

<strong>the</strong> low notes, and you’d release <strong>the</strong> keys <strong>to</strong> make <strong>the</strong> high notes<br />

... Press Release. I was really proud of myself because I thought<br />

I had made this funny joke, and <strong>the</strong>n of course Evan said, ‘You<br />

know, a lot of those high notes you play with all your fingers<br />

down, and a lot of those low notes you play with all your fingers<br />

up.’ But I didn’t think it was worth it <strong>to</strong> change <strong>the</strong> title.<br />

Michael Gordon<br />

Industry<br />

When I wrote Industry in 1993, I was thinking about <strong>the</strong><br />

Industrial Revolution, technology, how instruments are <strong>to</strong>ols<br />

and how industry has crept up on us and is all of a sudden<br />

overwhelming. I had this vision of a 100-foot cello made out of<br />

steel suspended from <strong>the</strong> sky, a cello <strong>the</strong> size of a football field,<br />

and, in <strong>the</strong> piece, <strong>the</strong> cello becomes a hugely dis<strong>to</strong>rted sound.<br />

VICKY CHOW<br />

I wrote this piece for Maya Beyser, a previous member of<br />

<strong>the</strong> All-Stars, and it was an incredible process. I would fax<br />

her <strong>the</strong> music and she’d play it <strong>to</strong> me over <strong>the</strong> phone. We did<br />

this maybe ten times, trying things out. She was constantly<br />

teaching me about <strong>the</strong> cello, and I was making her play things<br />

that were really awkward and dark.<br />

Note by Michael Gordon<br />

Evan Ziporyn<br />

Be in<br />

My earliest goal in life – formulated during a 1968 trip <strong>to</strong> San<br />

Francisco with my parents – was <strong>to</strong> be a hippie. My family drove<br />

our Ford Country Squire from Chicago; we went <strong>to</strong> Haight-<br />

Ashbury <strong>to</strong> gawk, and I was hooked. At age 13 I spent a week<br />

at my aunt’s Ann Arbor commune and my aspirations were<br />

confirmed. Only later was this replaced by <strong>the</strong> marginally more<br />

respectable goal of writing music. The two remain intertwined:<br />

anything I’ve done that was musically worthwhile was made<br />

possible by <strong>the</strong> 60s. Everyone who was anyone was reaching<br />

out <strong>to</strong> non-western music – not just S<strong>to</strong>ckhausen and The<br />

Beatles, but also BJ Thomas and <strong>the</strong> Partridge Family – all<br />

‘went raga’ at some point or ano<strong>the</strong>r. Much of my work is built<br />

around <strong>the</strong> anomalies and contradictions of cross-cultural<br />

exchange, but in this piece <strong>the</strong>re are no such problems:<br />

gestures from a variety of genres are combined as if all that<br />

were needed <strong>to</strong> make <strong>the</strong>m get along were good will and<br />

positive energy. Would that it were so ...<br />

ASHLEY BATHGATE<br />

The original version of Be in was written very quickly, for<br />

a group called ‘Evan and <strong>the</strong> All-stars’, which gave a single<br />

performance in Hartford, in 1991. I had only recently gotten<br />

my first computer – a MacPlus with a 20MB external hard<br />

drive – and this was one of <strong>the</strong> first pieces I didn’t notate by<br />

hand. Surprise surprise, <strong>the</strong> system crashed, I lost everything,<br />

so what you will hear is only a memory of <strong>the</strong> piece I originally<br />

wrote. It has had several o<strong>the</strong>r incarnations, re-orchestrated for<br />

<strong>the</strong> Michael Gordon Philharmonic, for a baroque-folk consort,<br />

for string orchestra, and for clarinet choir. This new version, for<br />

ano<strong>the</strong>r set of All-Stars, brings it all back home. The C-drone<br />

that starts <strong>the</strong> piece is homage <strong>to</strong> Terry Riley and <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> late<br />

violist John Lad, who played it dozens of time, and who was<br />

himself a participant in <strong>the</strong> original ‘be-in’ in San Francisco on<br />

January 14, 1967, <strong>the</strong> official start of <strong>the</strong> Age of Aquarius.<br />

Note by Evan Ziporyn<br />

EVAN ZIPORYN

5<br />

<strong>Perth</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> Festival in Association with<br />

Tura New Music Presents<br />

MUSIC FOR AIRPORTS<br />

Brian Eno’s 1978 seminal concept album<br />

WHEN<br />

Friday 4 March<br />

This performance is 1 hour and 20 minutes with no interval<br />

WHERE<br />

Bishops Garden, <strong>Perth</strong><br />

Brian Eno (born 1948)<br />

Music for Airports (1978)<br />

Burning Airlines Gives You So Much More (1974)<br />

Everything Merges in<strong>to</strong> Night<br />

Special Guests<br />

Anita Furhmann, Katie How, Molly Johnson, Brianna Louewen,<br />

Courtney Pitman, Rachel Scott, Philippa Tan, Shamara<br />

De Tissera from St George's Ca<strong>the</strong>dral Consort Choir<br />

Michael Howell and Christie Sullivan (flute), Philip Everall<br />

(bass clarinet), Paul Wright (violin), Noeleen Wright and Jon<br />

Tooby (cello), Callum G'Froerer and Jenny Coleman (trumpet),<br />

Tilman Robinson and Bruce Thompson (trombone)<br />

Brian Eno Music for Airports<br />

When we first heard Music for Airports in <strong>the</strong> late 70s/early<br />

80s it was like a door cracking open. This record-long piece<br />

was mesmerising, dreamy, intense and meant <strong>to</strong> be played in<br />

or thought of as fitting in<strong>to</strong> a specific environment. It was a<br />

redefinition of how we relate <strong>to</strong> music in our everyday lives.<br />

Brian Eno was exploring <strong>the</strong> question of where music could<br />

go. Could its home lie somewhere outside of <strong>the</strong> muzak of<br />

eleva<strong>to</strong>rs and dentists’ offices and outside of <strong>the</strong> concert hall<br />

as well? Could it exist somewhere in between?<br />

Eno was essentially defining Ambient music. Twenty years ago<br />

<strong>the</strong>re were no Ambient departments in record s<strong>to</strong>res. There<br />

were no New Age or techno sections, no chill rooms. Music for<br />

Airports kicked off a whole web of musics that hadn’t existed<br />

previously. But <strong>the</strong> unique fac<strong>to</strong>r about Eno’s work was that<br />

although it could and can exist in <strong>the</strong> background of everyday<br />

life it is music that carries potency and integrity that goes far<br />

beyond <strong>the</strong> incidental. It's music that is carefully, beautifully,<br />

brilliantly constructed and its compositional techniques rival<br />

<strong>the</strong> most intricate of symphonies.<br />

What Eno didn’t imagine was that his piece would be realised<br />

with live musicians. In his analog studio, methodically stringing<br />

out bits of tape and looping <strong>the</strong>m over <strong>the</strong>mselves, he hadn’t<br />

anticipated that a new generation of musicians would take his<br />

music out of <strong>the</strong> studio and perform it on live instruments in a<br />

public forum. At Bang on a Can, we have always searched for<br />

<strong>the</strong> redefinition of music, exploring <strong>the</strong> boundaries outside of<br />

what is expected. This project represents a fur<strong>the</strong>r step in this<br />

exploration. After 20 years, where does this landmark piece fit<br />

in<strong>to</strong> our ever expanding definition? The effect has only begun.<br />

The Music for Airports revolution is just beginning <strong>to</strong> unfold.<br />

The live realisation of Music for Airports stays close <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

source. We have had <strong>the</strong> great pleasure of sharing <strong>the</strong> project<br />

plans with Brian Eno along <strong>the</strong> way. We are indebted <strong>to</strong> him<br />

for giving us <strong>the</strong> experience of getting inside and out of this<br />

monumental work.<br />

Note by Michael Gordon, David Lang, Julia Wolfe, 1998<br />

Brian Eno<br />

Brian Eno is one of <strong>the</strong> most pivotal artists in modern music.<br />

As a musician, producer and collabora<strong>to</strong>r he has worked<br />

closely with U2, David Bowie, Peter Gabriel, David Byrne and<br />

many o<strong>the</strong>rs. As a solo artist he has created some of <strong>the</strong> most<br />

influential music of our age, most notably as <strong>the</strong> driving force<br />

behind ambient music.<br />

His early schooling was in visual art, where he steeped himself<br />

in <strong>the</strong> avant garde and gradually began <strong>to</strong> explore music as<br />

an ever-changing form of contemporary art. In 1971 he was<br />

co-founder of Roxy Music, syncing atmospheric <strong>to</strong>nality and<br />

early electronic experimentation with <strong>the</strong> band’s rock/pop<br />

sensibilities. The collaboration lasted for two albums before<br />

Eno branched out in<strong>to</strong> more surreal electronic realms in solo<br />

albums Here Come <strong>the</strong> Warm Jets and Taking Tiger Mountain<br />

(by Strategy). Through <strong>the</strong> early and mid-1970s he moved in<strong>to</strong><br />

more minimalist terri<strong>to</strong>ry, <strong>event</strong>ually creating what he termed<br />

‘ambient’ – low-volume music intended <strong>to</strong> modify <strong>the</strong> listener’s<br />

perception of his or her environment, including <strong>the</strong> conscious<br />

experience of time.<br />

The first real product of Eno’s idea was 1975’s Discreet Music,<br />

which evolved after he spent weeks in a body cast recovering<br />

from a car accident. Forced <strong>to</strong> listen <strong>to</strong> hospital music –<br />

often 18th century harp music played at a low volume – he<br />

pondered <strong>the</strong> effect of music on <strong>the</strong> environment, as well as<br />

active and passive listening. With ambient, instead of imposing<br />

an idea through a composition, he sought <strong>to</strong> remove <strong>the</strong><br />

human element, creating a space for stillness and emotional<br />

detachment, while allowing <strong>the</strong> mind <strong>to</strong> wander in and out of<br />

awareness. Discreet Music led <strong>to</strong> his Ambient Series: Music for<br />

Airports (Ambient 1); The Plateaux of Mirror (Ambient 2); Day<br />

of Radiance (Ambient 3); and On Land (Ambient 4).<br />

According <strong>to</strong> Eno, Music for Airports was conceived while<br />

waiting <strong>to</strong> board his plane on a Sunday morning in Cologne,<br />

Germany. The light was perfect, millions had been spent on <strong>the</strong><br />

architecture of <strong>the</strong> terminal and yet <strong>the</strong> music was horrible. No<br />

one had considered <strong>the</strong> impact of sound on <strong>the</strong> environment.<br />

He went away thinking of music in <strong>the</strong> public space and<br />

about <strong>the</strong> rituals of flight, which attended <strong>to</strong> practical but not<br />

emotional needs. He conceived of a soundscape that would:<br />

last for an extended period of time; wouldn’t interfere with<br />

human communication (necessitating <strong>the</strong> use of <strong>to</strong>nes higher<br />

or lower than human voices); and would be undiminished by<br />

interruptions such as flight announcements. Not wishing <strong>to</strong><br />

trivialise <strong>the</strong> act of being 40,000 feet above <strong>the</strong> Earth in a<br />

machine, he also hoped <strong>to</strong> create music that would calm <strong>the</strong><br />

individual and give a sense of being suspended in <strong>the</strong> universe<br />

– part of a larger existence where one might feel his or her life<br />

or death was not profoundly important.<br />

Over <strong>the</strong> past several decades, Brian Eno has worn many hats.<br />

He has produced numerous albums, scored films and a video<br />

game, presented <strong>the</strong> Turner Prize and has recently become<br />

an advocate of architects considering <strong>the</strong> need for areas of<br />

personal refuge in public spaces – echoing <strong>the</strong> principles found<br />

in ambient works such as Music For Airports.

6<br />

STEVE REICH'S 2x5<br />

The All-Stars let loose on six phenomenal<br />

pieces in a night of high adrenaline, ferocious<br />

rhythms and razor-sharp playing.<br />

WHEN<br />

Sunday 6 March<br />

This performance is 2 hours including an interval<br />

WHERE<br />

<strong>Perth</strong> Concert Hall<br />

David Lang (born 1957) Cheating, Lying, Stealing (1993)<br />

Julia Wolfe (born 1958) Believing (1997)*<br />

Steve Reich (born 1936) 2x5 (2009)*<br />

with special guest Derek Johnson<br />

INTERVAL<br />

Michael Gordon (born 1956) For Madeline (2009)*<br />

Thurs<strong>to</strong>n Moore (born 1958) Stroking Piece #1 (2003)*<br />

Steve Martland Horses of Instruction (1995)<br />

with special guest Paul Tanner<br />

*Australian Premiere<br />

David Lang<br />

Cheating, Lying, Stealing<br />

A couple of years ago, I started thinking about how so often<br />

when classical composers write a piece of music, <strong>the</strong>y are<br />

trying <strong>to</strong> tell you something that <strong>the</strong>y are proud of and like<br />

about <strong>the</strong>mselves – here’s this big gushing melody, see how<br />

emotional I am. Or, here’s this abstract hard-<strong>to</strong>-figure-out<br />

piece, see how complicated I am, see my really big brain. I am<br />

more noble, more sensitive, I am so happy. The composer<br />

really believes he or she is exemplary in this or that area. It’s<br />

interesting, but it’s not very humble. So I thought, What would<br />

it be like if composers based pieces on what <strong>the</strong>y thought<br />

was wrong with <strong>the</strong>m? Like, here’s a piece that shows you<br />

how miserable I am. Or, here’s a piece that shows you what a<br />

liar I am, what a cheater I am. I wanted <strong>to</strong> make a piece that<br />

was about something disreputable. It’s a hard line <strong>to</strong> cross.<br />

You have <strong>to</strong> work against all your training. You are not taught<br />

<strong>to</strong> find <strong>the</strong> dirty seams in music. You are not taught <strong>to</strong> be<br />

low-down, clumsy, sly and underhanded. In Cheating, Lying,<br />

Stealing, although phrased in a comic way, I am trying <strong>to</strong> look<br />

at something dark. There is a swagger, but it is not trustworthy.<br />

In fact, <strong>the</strong> instruction on <strong>the</strong> score for how <strong>to</strong> play it says:<br />

Ominous funk.<br />

Note by David Lang<br />

Julia Wolfe<br />

Believing<br />

The title for Believing came <strong>to</strong> me after <strong>the</strong> music had been<br />

written. During <strong>the</strong> time I was working on <strong>the</strong> piece I had been<br />

listening <strong>to</strong> a song by John Lennon called ‘Tomorrow Never<br />

Knows’. It’s a fantastic song – very psychedelic – written at a<br />

time when <strong>the</strong> Beatles were exploring spiritual questions. You<br />

can hear it in <strong>the</strong> music, and in <strong>the</strong> words. There’s a line, ‘It is<br />

believing’ that comes back again and again. Believing is such<br />

a powerful word – full of optimism and struggle. It’s hard <strong>to</strong><br />

believe and it’s liberating <strong>to</strong> believe. The music is very much<br />

written for <strong>the</strong> Bang on a Can All-Stars. It is my second piece<br />

Image by Jeff Herman<br />

STEVE REICH<br />

for <strong>the</strong> group and I feel that I have really gotten inside <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

sound. Believing was commissioned by NPS Dutch Radio for<br />

<strong>the</strong> Bang on a Can All-Stars. I am very grateful for <strong>the</strong>ir support<br />

for this work.<br />

Note by Julia Wolfe<br />

Steve Reich<br />

2x5<br />

My first thought was that with two electric basses I could write<br />

interlocking bass lines that would be clearly heard. This would<br />

not be possible on acoustical basses played pizzica<strong>to</strong>. I <strong>the</strong>n<br />

began <strong>to</strong> think about two pianos and two electric basses being<br />

<strong>the</strong> mo<strong>to</strong>r for a piece that would use electric guitars and small<br />

drum kit as well. The classic rock combination of two electric<br />

guitars, electric bass, drums and piano seemed perfect – so<br />

long as it was a doubled quintet resulting in two basses, two<br />

pianos, two drums and four electric guitars. This made possible<br />

interlocking canons of identical instruments. The piece can be<br />

played ei<strong>the</strong>r with five live musicians and five pre-recorded or<br />

with ten musicians.<br />

2x5 is clearly not rock and roll. Like any o<strong>the</strong>r composition, it's<br />

completely notated while rock is generally not. 2x5 is chamber<br />

music for rock instruments.<br />

We're living at a time when <strong>the</strong> worlds of concert music and<br />

popular music have resumed <strong>the</strong>ir normal dialogue after a<br />

brief pause during <strong>the</strong> 12 <strong>to</strong>ne/serial period. This dialogue has<br />

been active, I would assume, since people have been making<br />

music. We know from notation that it was active throughout<br />

<strong>the</strong> Renaissance with <strong>the</strong> folk song L'homme Armè used in<br />

masses by composers from Dufay <strong>to</strong> Palestrina. During <strong>the</strong><br />

Baroque period dance forms were used by composers from<br />

Froberger and Lully <strong>to</strong> Bach and Handel. Later we have a folk<br />

songs in Haydn's 104th, Beethoven's 6th, Russian folk songs in<br />

Stravinsky's early ballets, Serbo Croatian folk music throughout<br />

Bar<strong>to</strong>k, hymns in Ives, folk songs and jazz in Copland, <strong>the</strong><br />

entire works of Weill, Gershwin and Sondheim and on in<strong>to</strong> my<br />

own generation and beyond. Electric guitars, electric basses<br />

and drum kits, along with samplers, syn<strong>the</strong>sisers and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

electronic sound processing devices are now part of notated<br />

concert music. The dialogue continues.<br />

Note by Steven Reich<br />

Michael Gordon<br />

For Madeline<br />

I spent most of 2009 going in and out of synagogues <strong>to</strong> say<br />

Kaddish, <strong>the</strong> Jewish prayer of mourning, for Madeline. Of<br />

course she wouldn’t have approved. She was a communist.<br />

Madeline lived in a different world, a world of transplanted<br />

Yiddish secular culture. I realised all of this only much later.<br />

There’s plenty of time <strong>to</strong> think about <strong>the</strong>se things in synagogue<br />

because <strong>the</strong>re are numerous prayers and who can concentrate

7<br />

on so many of <strong>the</strong>m? Madeline loved music and she would take<br />

me <strong>to</strong> concerts when I was little. I would fall asleep but that<br />

didn’t deter her. She wanted me <strong>to</strong> love music as much<br />

as she did but she certainly did not want me <strong>to</strong> be a composer.<br />

Madeline, are you listening? I dedicate this piece <strong>to</strong><br />

your memory.<br />

Note by Michael Gordon<br />

Thurs<strong>to</strong>n Moore<br />

Stroking Piece #1<br />

Stroking Piece #1 was written as a fairly typical example<br />

of a mid-period Sonic Youth-centric guitar instrumental:<br />

an episode of dynamic build with resultant <strong>to</strong>ne-shards<br />

culminating in a noise improvisation/meditation released<br />

in<strong>to</strong> repetition as thought-stroke release. Stroking Piece #1<br />

was commissioned for <strong>the</strong> Bang on a Can All-Stars with <strong>the</strong><br />

generous contributions from <strong>the</strong> members of <strong>the</strong> Bang on a<br />

Can People’s Commissioning Fund.<br />

inherited. The struggle <strong>to</strong> achieve this task mirrors <strong>the</strong> struggle<br />

people live with, particularly in a political sphere. In a recent<br />

article, Steve reveals his commitment <strong>to</strong> this cause: ‘The late<br />

20th century is racked with doubts, skeptical of certainties,<br />

scornful of ready-made panaceas, unsure about <strong>the</strong> future.<br />

This fear of <strong>the</strong> future has created a culture of nostalgia. The<br />

past is seen as an infinitely more comforting place where<br />

problems can be ignored. In <strong>the</strong> face of this huge regression,<br />

both of political will and poverty of imagination, music has a<br />

function as never before – not <strong>to</strong> reflect reality (all art does<br />

that anyway) but <strong>to</strong> confront it: music as a weapon against<br />

despair. This is <strong>the</strong> challenge that faces <strong>the</strong> contemporary<br />

composer... Music should be a protest for human values, a<br />

prophecy for change. In an apocalyptic world, it gives <strong>the</strong><br />

possibility, however remote, of affirmation.’<br />

Note by David Lang<br />

Steve Martland<br />

Horses of Instruction<br />

Steve Martland’s compositions contain a driving vernacular<br />

sense of being music of our time, of <strong>the</strong> street, of pop culture,<br />

yet <strong>the</strong>y are organised with a tremendous amount of clarity.<br />

Essential <strong>to</strong> his work is <strong>the</strong> conviction that his pieces are being<br />

dropped in<strong>to</strong> a struggle and <strong>the</strong>y have <strong>the</strong> power <strong>to</strong> influence<br />

that struggle, that music exists in a political world. Classical<br />

music is all about authority and respecting what you have<br />

learned in <strong>the</strong> past. Like his teacher, Louis Andriessen, Steve is<br />

a revolutionary. His music is not about beautiful orchestration<br />

or beautiful notes, but about musicians working <strong>to</strong>ge<strong>the</strong>r with<br />

a common difficult task, challenging <strong>the</strong> musical ideas we have<br />

Image by Peter Serling<br />

MARK STUART<br />

DAVID COSSIN<br />

AEG OGDEN (PERTH) PTY LTD<br />

STATE THEATRE CENTRE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA<br />

General Manager .............................................................................................................................. Brendon Ellmer<br />

Deputy General Manager .................................................................................................. Alice Jorgensen<br />

Technical Manager ................................................................................................................................ Graham Piper<br />

Operations Manager ......................................................................................................................... Lorraine Rice<br />

State Theatre Centre of Western Australia is managed<br />

by AEG Ogden (<strong>Perth</strong>) Pty Ltd Venue Manager for <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Perth</strong> Theatre Trust Venues<br />

AEG OGDEN (PERTH) PTY LTD<br />

PERTH CONCERT HALL<br />

General Manager ......................................................................................................................................... Andrew Bolt<br />

Deputy General Manager (Acting) ..................................... Miranda Lancaster-Allen<br />

Technical Manager .................................................................................................................................. Peter Robins<br />

Event Coordina<strong>to</strong>r ......................................................................................................................... Penelope Briffa<br />

<strong>Perth</strong> Concert Hall is managed by AEG Ogden<br />

(<strong>Perth</strong>) Pty Ltd, Venue Manager for <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Perth</strong> Theatre Trust Venues<br />

AEG OGDEN (PERTH) PTY LTD<br />

Chief Executive ............................................................................................................................ Rodney M Phillips<br />

Hawaiian is a passionate supporter of<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Arts</strong> in our community and proud<br />

<strong>to</strong> host Bang on a Can All-Stars for <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>2011</strong><strong>Perth</strong> Festival<br />

THE PERTH THEATRE TRUST<br />

Chairman ................................................................................................................................................... Dr Saliba Sassine<br />

www.hawaiian.com.au

founDer<br />

partners<br />

principal sponsors<br />

premier sponsors<br />

meDia partner<br />

This <strong>event</strong> powered by<br />

major sponsors<br />

public funDing partners<br />

Department of Education<br />

Department of Education<br />

Department of Culture and <strong>the</strong> <strong>Arts</strong><br />

Department of Culture and <strong>the</strong> <strong>Arts</strong><br />

Tourism Western Australia<br />

Tourism Western Australia<br />

Public Transport Authority<br />

Public Transport Authority<br />

international<br />

funDing boDies<br />

supporting sponsors<br />

A O’Meehan & Co – Grain & Grainfed<br />

Albany Chamber of Commerce & Industry<br />

Albany Public Library<br />

Avant Card<br />

Barnesby Ford Chrysler Jeep<br />

Bay Merchants<br />

BOC Limited<br />

Brett and Annie Fogarty<br />

Community Newspaper Group<br />

Drum Media <strong>Perth</strong><br />

Fremantle Press<br />

Friends of <strong>the</strong> Festival<br />

Fusion H2O<br />

Greenhouse St Georges Terrace<br />

H+H Architects<br />

Hanover Bay Studio Apartments<br />

HarperCollins Australia<br />

Instant Toilets and Showers<br />

Lincolns Accountants and Business Advisers<br />

Macmahon<br />

Must Winebar<br />

Oranje Trac<strong>to</strong>r Wine<br />

<strong>Perth</strong>Web<br />

RTRFM 92.1<br />

State Library of Western Australia<br />

The Brisbane Hotel<br />

The Byrneleigh<br />

The George<br />

Tom’s Kitchen<br />

X-Press Magazine<br />

Western Australian Museum – Albany<br />

<strong>2011</strong> private giving <strong>program</strong> Donors<br />

Bernard and Jackie Barnwell<br />

In memory of Dr Stella Barratt-Pugh<br />

Dr Susan Boyd<br />

Brenda Buchanan<br />

Janette Brooks<br />

Coral Carter and Terry Moylan<br />

Penny and Ron Crittal<br />

John Chandler and Barbara Whittle<br />

Dr David Cooke<br />

Joanne Cruickshank<br />

Marco D’Orsogna<br />

Helen Fenbury<br />

Des Gurry<br />

SC Hicks<br />

James and Freda Irenic<br />

Janet King<br />

Stephen Kobelke<br />

Louis I and Miriam Landau<br />

Kathy and Max Macarthur<br />

Peter Mallabone<br />

Gaye and John McMath<br />

Claire Phillips<br />

Margaret O’Halloran<br />

J Rivalland<br />

Andrea Shoebridge<br />

Maureen Smith<br />

Spinifex Trust<br />

Professor Fiona Stanley<br />

Gene Tilbrook<br />

Diana Warnock<br />

Christine Wheeler<br />

Dr Hea<strong>the</strong>r Whiting and Richard Hatch<br />

Margaret Whitter<br />

Dr Helen Wildy<br />

Michael Wise<br />

Wendy Wise and Nick Mayman<br />

Mrs Brigid Woss<br />

Anonymous (12)<br />

<strong>2011</strong> meDici Donors<br />

Zelinda Bafile<br />

Peter and Tracey Bacich<br />

Brans Antiques & Art<br />

Peter Burns<br />

Mike and Liz Carrick<br />

Dr David Cooke<br />

Alan R Dodge AM<br />

Grant and Cathy Donaldson<br />

Marco D’Orsogna<br />

Adrian and Michela Fini<br />

Paul and Susanne Finn<br />

Annie and Brett Fogarty<br />

Graham Forward and Jacqui Gilmour<br />

Terry Grose and Rosemary Sayer<br />

Mack and Evelyn Hall<br />

Sue and Peter Harley<br />

Kerry Harmanis<br />

Dale Harper and Derek Gascoine<br />

Richard and Nina Harris<br />

Maxine Howell-Price<br />

Adam Lenegan<br />

Peter and Lynne Leonhardt<br />

Murray and Suzanne McGill<br />

Ian and Jayne Middlemas<br />

Michael Murphy and Craig Merrey<br />

Helen and John Owenell<br />

Mimi and Willy Packer<br />

Richard Payne and Cim Sears<br />

Philip Griffiths Architects<br />

Pearl Proud<br />

Bill Repard and Jane Prendiville<br />

Sam and Dee Rogers<br />

Peter Smith and Alexandrea Thompson<br />

Gary and Jackie Steinepreis<br />

Craig Suttar<br />

Dr Phillip and Jill Swarbrick<br />

Sue Thomas<br />

Thompson Estate Vineyard<br />

Joe and Debbie Throsby<br />

Tim and Chris Ungar<br />

Ian and Margaret Wallace<br />

Kieran Wong<br />

Michael and Edit Wood<br />

Melvin Yeo<br />

Anonymous (3)<br />

tHe festival WisHes <strong>to</strong> tHanK<br />

Printed on 100% Recycled Paper<br />

Supported by Environmental Sustainability Partner Synergy