MORE THAN RAIN - Utviklingsfondet

MORE THAN RAIN - Utviklingsfondet

MORE THAN RAIN - Utviklingsfondet

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

M o r e t h a n r a i n :<br />

Climatic Ch a n g e Vulnerability Fo r Sm a l l Sc a l e Fa r m e r s In Nic a r a g u a<br />

Climate change is gradually being<br />

felt by communities all over the<br />

world. Changes in temperature and<br />

rainfall patterns are already contributing<br />

to increasing the vulnerability of many<br />

of the poor in developing countries. In<br />

Nicaragua the weather pattern has changed<br />

dramatically. This creates another factor of<br />

vulnerability for small scale farmers with<br />

few or no other options to secure their<br />

livelihoods.<br />

Based on information and data from local<br />

farmers in Nicaragua, this publication will<br />

assess how climate change is affecting the<br />

situation for farmers, and how they are<br />

working towards limiting vulnerability to<br />

changing conditions. The study has been<br />

conducted with cooperation from the<br />

Centre for Promotion of Rural and Social<br />

Development (CIPRES) in Nicaragua.<br />

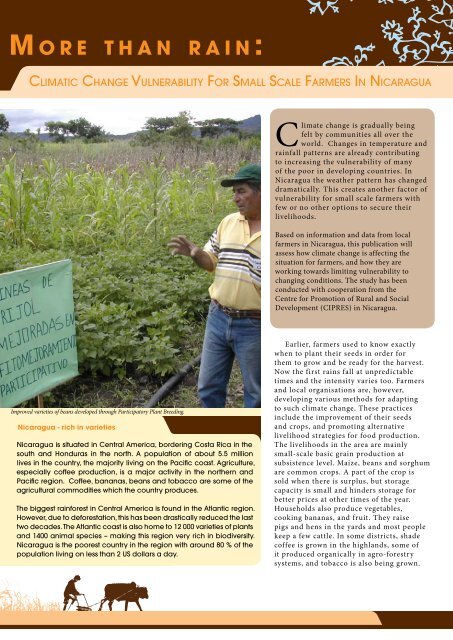

Improved varieties of beans developed through Participatory Plant Breeding.<br />

Nicaragua - rich in varieties<br />

Nicaragua is situated in Central America, bordering Costa Rica in the<br />

south and Honduras in the north. A population of about 5.5 million<br />

lives in the country, the majority living on the Pacific coast. Agriculture,<br />

especially coffee production, is a major activity in the northern and<br />

Pacific region. Coffee, bananas, beans and tobacco are some of the<br />

agricultural commodities which the country produces.<br />

The biggest rainforest in Central America is found in the Atlantic region.<br />

However, due to deforestation, this has been drastically reduced the last<br />

two decades. The Atlantic coast is also home to 12 000 varieties of plants<br />

and 1400 animal species – making this region very rich in biodiversity.<br />

Nicaragua is the poorest country in the region with around 80 % of the<br />

population living on less than 2 US dollars a day.<br />

Earlier, farmers used to know exactly<br />

when to plant their seeds in order for<br />

them to grow and be ready for the harvest.<br />

Now the first rains fall at unpredictable<br />

times and the intensity varies too. Farmers<br />

and local organisations are, however,<br />

developing various methods for adapting<br />

to such climate change. These practices<br />

include the improvement of their seeds<br />

and crops, and promoting alternative<br />

livelihood strategies for food production.<br />

The livelihoods in the area are mainly<br />

small-scale basic grain production at<br />

subsistence level. Maize, beans and sorghum<br />

are common crops. A part of the crop is<br />

sold when there is surplus, but storage<br />

capacity is small and hinders storage for<br />

better prices at other times of the year.<br />

Households also produce vegetables,<br />

cooking bananas, and fruit. They raise<br />

pigs and hens in the yards and most people<br />

keep a few cattle. In some districts, shade<br />

coffee is grown in the highlands, some of<br />

it produced organically in agro-forestry<br />

systems, and tobacco is also being grown.<br />

1

Climatic Ch a n g e Vulnerability Fa c t o r s Fo r Sm a l l Sc a l e Fa r m e r s in Nic a r a g u a<br />

The study area and project site<br />

Nicaragua (project area in green)<br />

The study was carried out in the Municipalities of<br />

Condega, Pueblo Nuevo (both in the Department of<br />

Estelí), and Totogalpa (Department of Madriz). CIPRES<br />

has been working for more than seven years in these<br />

areas. CIPRES is advising and accompanying small<br />

farmers in the application of sustainable agricultural<br />

practices that include the improvement of their crops.<br />

The three municipalities cover an area of 739.3<br />

km2 and have a population of approximately 65,<br />

people. The project area is located in the North<br />

Region of Nicaragua.<br />

The Central North Macro Region has been<br />

classified as a Dry Zone because of its low rainfall.<br />

Due to the presence of cordilleras, massifs, and valleys,<br />

the local climate, has spatial and temporal distribution<br />

of precipitation. Nicaragua has a tropical savannah<br />

climate with variations according to elevation (semiwet<br />

in the highlands and dry in the lowlands).<br />

Climatic risks and local vulnerability<br />

Nicaragua is one of the poorest countries in<br />

Latin-America, with a GDP per capita of US3,2<br />

compared to 13,5 in its neighbouring country Costa<br />

Rica. A poor welfare system, unequal distribution of<br />

wealth and resources, and decades of conflict are other<br />

reasons that have led to extreme poverty. Many families<br />

have lost their livelihood assets; they have low levels<br />

of education and limited access to healthcare. The<br />

lack of information about sustainable agriculture has<br />

resulted in unsustainable practices and monoculture<br />

designed and oriented to an external market. All this<br />

has put strain on and deteriorated the natural resource<br />

base. The break up and eventual disintegration of many<br />

families of migrants along with a high proportion<br />

of households run by single women (temporally or<br />

permanently) are also expressions of the vulnerability<br />

that the communities have to deal with daily.<br />

Climate change in Nicaragua<br />

The climate is unpredictable and extreme weather<br />

has become more common. During the course of<br />

a year, there can be both drought and hurricanes.<br />

Drought alternated with excessive rainfall, making<br />

farmers vulnerable since they are not able to be<br />

prepared or respond to such extreme weather<br />

patterns. Furthermore, the effects of climate changes<br />

come in addition to the degradation of the natural<br />

resource base because of agro-chemicals, overcultivation<br />

of soils, deforestation, slash-and-burn<br />

agriculture and deterioration of water sources.<br />

People in the countryside are no longer able to<br />

predict the weather patterns. Before they could plan<br />

agricultural activities following signs from nature but<br />

now, local predictions are no longer effective. Both<br />

the occurrence of drought as well as late rainy seasons,<br />

have changed the best time for planting basic grains.<br />

Social dimension and people’s perception of climate change<br />

Global warming has created many new challenges and problems all<br />

around the world. Climate change is predominantly noticed through<br />

changes in weather patterns, temperatures, amount of precipitation<br />

etc. For many poor farmers this has a direct impact on their livelihoods,<br />

forcing them to change their agricultural practices. This change is<br />

neither easy nor cheap, creating more insecurity for the already<br />

marginalized farmers.<br />

In this analysis we consider past and current climate stress by looking<br />

at subjective experiences of climatic events. The experienced climatic<br />

variability and change is crucial in an adaptation analysis, because<br />

the outcomes depend not only on the meteorological qualities of a<br />

weather pattern or extreme event, but also on contextual factors that<br />

influence people’s vulnerability and their capacity to adapt. Thus, a<br />

minor drought might have serious consequences for some, while others<br />

may experience relatively small consequences of a serious drought.<br />

Such understanding makes it possible to design measures that support<br />

poor people in their own efforts and make use of existing strengths and<br />

opportunities. The analysis therefore argue that adaptation measures<br />

needs to move beyond climate risks and physical adaptation<br />

measures, to include the social context and people’s perception of<br />

climate change, in order to build their capacity and resilience to cope<br />

with barriers and thresholds.<br />

2

Drought<br />

The most frequent and damaging expression of<br />

climate change in this area is the irregularity of the<br />

rainy season. In Nicaragua, the rainy season runs<br />

from May to October, and when rainfall is less than<br />

normal in volume and frequency, a drought occurs.<br />

Because these changes are associated with El Niño,<br />

droughts show no predictable pattern and their effects<br />

are devastating, especially in the dry zone.<br />

One of the main effects of drought is degradation<br />

of water sources. Water sources are often unprotected<br />

because of the deforestation and degradation. The<br />

soil has little infiltration capacity, hence the rain<br />

carries away the soil surface layer. Rivers have lower<br />

flows and many creeks easily dry up when there is<br />

drought or overflow in the rainy season. Sources of<br />

water become gradually scarcer and the pollution is<br />

more concentrated because of low flows or stagnation.<br />

Only in areas with dense forest cover some water<br />

sources has been preserved.<br />

The soil also loses fertility by being carried off by<br />

the winds after it is converted into dust under direct<br />

solar radiation. The erosive processes become worse<br />

and there is a greater propensity for landslides and<br />

landslips. These impoverished and compacted soils<br />

limit possibilities for growing crops, especially if there<br />

is only a minimum of water available.<br />

Cattle require stable temperatures for adequate<br />

development. During droughts, temperatures rise,<br />

pastures do not grow well, and there is a general<br />

shortage of food for them. Due to lack of water, the<br />

cattle do not develop properly and milk production<br />

falls. In addition, cattle and pigs suffer miscarriages<br />

and some die. Farmers have to sell their animals in<br />

order to cover their losses. Droughts occur irregularly,<br />

either with the rainy season coming late (not until<br />

July) or with dry spells (of up to one month) during<br />

the rainy season, or rainfall is low and dispersed over<br />

the period.<br />

El Niño - the Southern Oscilation<br />

El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a general term used to describe<br />

both warm (El Niño) and cool (La Niña) ocean-atmosphere events<br />

in the tropical Pacific. El Niño and La Niña are officially defined as<br />

sustained sea surface temperature anomalies of magnitude greater<br />

than 0.5°C across the central tropical Pacific Ocean. Historically, it has<br />

occurred at irregular intervals of 2-7 years and has usually lasted one<br />

or two years.<br />

ENSO is associated with floods, droughts, and other disturbances in a<br />

range of locations around the world. These effects, and the irregularity<br />

of the ENSO phenomenon, make predicting it very difficult. The IPCC<br />

claims that ENSO is the dominant mode of climate variability in Latin<br />

America and is the natural phenomenon with the largest socioeconomic<br />

impacts.<br />

2007 was a year when typical effects from La Niña were experienced<br />

in Nicaragua: dry at the start, wet and cold at the end. Because of the<br />

rainfall deficit at the beginning of the rainy season in May, June, and<br />

July, the planting of basic grains did not begin until late June. Hence<br />

the first bean crop could not be harvested as it should be during the<br />

canícula (the warmest period of the year); but only in August and<br />

harvesting coincided with the work of the second planting. The crops<br />

were then affected by the low temperatures in October and there<br />

were major losses of the basic grains harvest. The next cycle also had<br />

low yields and low quality grains because of these alterations. Due to<br />

these harvest losses, many farmers were left indebted.<br />

3

Climatic Ch a n g e Vulnerability Fa c t o r s Fo r Sm a l l Sc a l e Fa r m e r s in Nic a r a g u a<br />

Adaptation to climatic<br />

changes and vulnerability<br />

Participatory plant breeding (PPB)<br />

For centuries farmers have been<br />

domesticating and improving varieties of<br />

basic grains by means of ancestral practices,<br />

generating the biological diversity that<br />

characterised the region. This diversity has<br />

been their principal tool for dealing with<br />

the unpredictable nature of the climate,<br />

and the heterogeneity of environments in<br />

order to guarantee farmers food security.<br />

The Participatory plant breeding Meso-<br />

America (PPB-MA) rescues and improves<br />

these ancestral practices by combining<br />

farmers traditional knowledge with scientific<br />

development. Researchers and farmers work<br />

together in developing stronger and better<br />

food plants that are better suited to variable<br />

climate conditions.<br />

CIPRES has been accompanying and<br />

advising groups of farmers in Pueblo Nuevo<br />

and Condega for more than seven years and<br />

in Totogalpa more recently, with the purpose<br />

of increasing and improving the production<br />

of quality seed with methods controlled by<br />

farmers.<br />

The local approach<br />

Unlike with conventional plant breeding,<br />

in participatory plant breeding the farmer is<br />

a key actor in the decision-making process,<br />

especially in selecting the plants with the<br />

characteristics that are of interest to them.<br />

They select those that will develop better<br />

in the conditions of their farms – at the<br />

level of micro-zones - that are resistant to<br />

drought, pests, and diseases, with good plant<br />

size, greater yield, and better quality of the<br />

final product in terms of taste, nutritional<br />

qualities and forage for animals. Farmers<br />

apply their criteria in selecting the material<br />

and evaluating it.<br />

PPB is particularly relevant in the context<br />

of these communities, where the most<br />

fundamental resources for guaranteeing their<br />

basic livelihood have been lost.<br />

In PPB, the trials were made in the<br />

parcels of the farmers – under natural<br />

conditions. Thus the plants were being<br />

improved and developed in different settings<br />

and exposed to environmental changes such<br />

as drought, high relative humidity, high<br />

temperatures, flooding, etc. Work has been<br />

done with local varieties of maize, beans,<br />

sorghum and millón that were gathered and<br />

introduced into different agro-ecological<br />

conditions at different elevations. Advanced<br />

lines and families have also been introduced,<br />

after crossing with the local varieties; have<br />

created a broad genetic diversity.<br />

The Collaborative Programme for<br />

Particpatory Plant Breeding in Meso-America<br />

The Collaborative Programme for Participatory Plant Breeding in Meso-America<br />

(PPBMA) was initiated in 2001. Groups and agencies from the region and CIPRES<br />

joined the program, in particular to access good quality seeds that would<br />

enable them to improve yields and begin to improve their quality of life.<br />

In contrast to modern development of plants, that often take place in seed<br />

companies’ laboratories. Participatory plant breeding takes place in the<br />

farmers’ field. Farmers receive knowledge and training before carrying out<br />

cross breeding and research to develop suitable seeds for their climate, soil<br />

and taste.<br />

The farmers have the lead and control over the whole process in the programme,<br />

and decide on the attributes he or she wants to improve. In Totogalpa, the work<br />

of plant breeding begun by the CIAT-CIRAD, and CIPRES continued with the<br />

process, moving it ahead. The link with CIAT (International Centre for Tropical<br />

Agriculture) is maintained and it still provides genetic material for sorghum as<br />

well as technical assistance.<br />

The plant breeding project being executed in Nicaragua is part of the<br />

Collaborative Programme for Participatory Plant Breeding in Meso-America,<br />

with particular emphasis on the participation of the farmers in decision-making<br />

and their access to knowledge for improving the varieties of basic grains they<br />

cultivate. This programme has facilitated alliances between different actors,<br />

with farmers and their organisations playing an important role in the process,<br />

as well as governmental institutions, NGOs, universities, cooperation agencies,<br />

and national and international research centres.<br />

The linking of experiences developed in the countries through the PPB-MA<br />

as regional liaison allows for exchanging experiences, having references,<br />

making comparisons, and sharing what is learned at the regional level with an<br />

expanded horizon for all the actors.<br />

Human resources are key to the success of any plant breeding activity. Farmers<br />

are intrinsic breeders because they possess knowledge about the behaviour<br />

of their materials and about local productive conditions. Such knowledge is<br />

complementary to the experiences and capacities for scientific analysis that<br />

the professional breeder may have. Plant breeding must also be considered in<br />

terms of empowerment. The capacity to acquire or develop decision-making<br />

power, is necessary to achieve long-term development objectives. This means<br />

that farmers and the community must develop the capacity to make decisions,<br />

from both technical and organizational points of view.<br />

4

Adaptation through strengthening of<br />

farmers organisations and networking<br />

In order to work with participatory<br />

plant breeding, the Nicaraguan farmers<br />

have required their own autonomous<br />

organisation to represent them.<br />

In late 24 the farmers from Pueblo<br />

Nuevo created the COSENUP RL (New<br />

Union of Producers Multiple Services<br />

Cooperative, Limited Responsibility)<br />

whereby the members have proposed the<br />

goal of producing and commercialising<br />

improved seeds. For this, they are forming a<br />

commercialisation committee, another one<br />

for seeds, and others for credit, education,<br />

and research.<br />

As indications of their level of growth<br />

and self-managed undertakings, the<br />

COSENUP is strengthening ties and<br />

establishing alliances with other farmers’<br />

organisations - including three youth<br />

organisations. COSENUP also provides<br />

temporary coverage to groups of farmers<br />

from Totogalpa and Somoto.<br />

Farmers’ decision of organising<br />

themselves into cooperatives such as<br />

COSENUP RL, has been successful. In<br />

these communities, more and more families<br />

exchange information, knowledge, strategies,<br />

and agricultural products. They give each<br />

other mutual support, search for solutions<br />

to common problems affecting them, and<br />

combine their efforts.<br />

In just a few years, these cooperatives<br />

have been making themselves into solid<br />

organisations. They have matured and<br />

developed. The collaboration with NGOs,<br />

academia and government organisations<br />

has enabled them to scale up their actions<br />

and goals. They are acquiring capital goods<br />

under collective ownership: a wet coffee<br />

processing plant in Condega, a chicken<br />

farm in Pueblo Nuevo, and a collection and<br />

storage centre. They are increasingly making<br />

greater commitments and their decisions<br />

are responding to economic, social and<br />

environmental analysis among others. They<br />

aim to create jobs that will contribute to<br />

improving the socioeconomic situation of<br />

their communities.<br />

Women groups<br />

Collective action is making it possible<br />

for the families to make changes and<br />

undertake initiatives that would not be<br />

possible otherwise. For example in Pueblo<br />

Nuevo, groups of women have been<br />

organised in the communities to work with<br />

family gardens, using organic and agroecological<br />

practices, with better results<br />

and without endangering their health or<br />

polluting the surroundings. Strengthening<br />

farmers’ organisations and networks,<br />

with a special focus on the inclusion of<br />

women in these activities, enhance peoples’<br />

ability to adapt to climate changes.<br />

Adaptation through<br />

Diversifying Production Practices<br />

More and more farmers are making<br />

relevant changes in their production<br />

practices adopting agro-ecological methods<br />

that are environmentally-friendly. Farmers<br />

are:<br />

• Planting branches of trees that<br />

will take root along their fence<br />

lines, and ploughing back weeds<br />

into the soil;<br />

• Planting and incorporating cover<br />

crops and applying compost in<br />

order to recover fertility;<br />

• Undertaking soil conservation<br />

work in order to have more<br />

infiltration of water and to retain<br />

the soil;<br />

• Practicing natural regeneration.<br />

They do not cut down young trees<br />

and only use dead branches.<br />

Crop rotation and diversification on<br />

the farms is a strategy that the farmers are<br />

practicing primarily to have food all year<br />

round, but also to generate income when<br />

there is a surplus. Farmers combine crops<br />

in the parcel or yard, such as squashes,<br />

onions, sweet peppers, yucca/cassava and<br />

cooking bananas.<br />

In addition to being a sound practice<br />

for the soil, diversification has contributed<br />

to improved food security of the families,<br />

and to a certain degree helping them to<br />

overcome the dependency on basic grains,<br />

diversifying and improving the family<br />

diet, producing feed for animals, and<br />

earning income. They reduce their risks by<br />

diversifying and building their farm assets.<br />

If conditions become adverse, at least one<br />

of these crops will produce. By planting<br />

some crops during the first cropping season,<br />

and others in the second, they become less<br />

vulnerable to the erratic rains, pests and low<br />

market prices.<br />

5

Climatic Ch a n g e Vulnerability Fa c t o r s Fo r Sm a l l Sc a l e Fa r m e r s in Nic a r a g u a<br />

Strategies for Economic Growth<br />

In order to get beyond production<br />

for survival and generate income,<br />

some families are beginning to<br />

experiment on a small scale with<br />

product value adding. Individually or<br />

collectively, for example, some women<br />

are making sweets and marmalades.<br />

They package dry flowers, marmalades<br />

and make wine that they sell in the<br />

local markets. As cooperatives, they<br />

are producing poultry and organic<br />

coffee, among other products, on a<br />

greater scale. The more processed the<br />

food crops are, the more economic<br />

value is added to the products.<br />

Crop<br />

Yields per manzana*<br />

without PPB (averages)<br />

Somoto<br />

Pueblo Nuevo<br />

and Condega<br />

Yields per<br />

manzana<br />

with PPB (cw =<br />

hundredweight)<br />

% increase<br />

Maize 8 cw 15 cw 22.5 cw 50 - 180%<br />

Beans 17 cw 12 cw 22 cw 30 - 83%<br />

Sorghum 12 cw 12 cw 18 cw 50%<br />

*Manzana is a measure for land area, 0,7 ha.<br />

Source: Regional coordination, PPBMA, 2007.<br />

The value of<br />

local cultural practices<br />

Ancestral survival strategies are<br />

reintroduced, such as exchanging<br />

agricultural products. A mediería,<br />

which means a farmer who owns land<br />

work half-and-half with a landless<br />

farmer. Modalities for this vary, but<br />

generally, the one with more resources<br />

contributes with seed. This practice<br />

especially benefits those farmers<br />

who lost their arable land due to<br />

Hurricane Mitch.<br />

People’s capacity to adapt<br />

Many small farmers in these<br />

communities have suffered a total loss<br />

of their crops on repeated occasions,<br />

due to factors such as pest outbreaks<br />

and lack of rain. Climate variability<br />

now constitutes an additional threat<br />

factor. This is affecting the food security<br />

of their families, as food is in short<br />

supply for both people and livestock.<br />

The capacity to adapt to climate change<br />

varies between individuals and groups.<br />

The majority of the population in the<br />

region has knowledge and skills of<br />

growing maize, beans and sorghum,<br />

some vegetables and fruits, as well as<br />

in traditional animal husbandry. They<br />

also have traditional knowledge on how<br />

to interpret and predict weather and<br />

seasons, but since the patterns have<br />

changed, this knowledge is less accurate<br />

today than before.<br />

In the Northern zone of Nicaragua<br />

important livelihood assets are<br />

land, animals, seeds and the work<br />

capacity of women, men, youth and<br />

children. People have little access to<br />

technologies which could strengthen<br />

their food security and incomes. There<br />

has been limited cooperation, little<br />

exchange of products or services, little<br />

organization of activities, and few<br />

community initiatives. However, people<br />

demonstrate through these projects<br />

that they have the capacity to enter into<br />

valuable cooperation for the community<br />

as a whole.<br />

As a result of the activities, less<br />

people choose to migrate, and engage<br />

themselves in the improvements of<br />

agricultural techniques. Vulnerability<br />

and poverty is still present in the project<br />

area, but the project activities have<br />

increased the capacity of households and<br />

communities to respond to the threats<br />

they are facing.<br />

What does this mean for<br />

reducing local vulnerability?<br />

The effects of changes in climate are<br />

one of the main causes of alterations<br />

in the cultivation of basic grains in<br />

the last few decades, either because of<br />

the occurrence of drought, hurricanes,<br />

and/or excessive rainfall or because<br />

of the ecological alterations caused by<br />

those phenomena such as depletion<br />

of soils and water sources, alterations<br />

in the populations of insects that<br />

sometimes become pests, and the<br />

occurrence of illnesses.<br />

Farmers are achieving greater yields<br />

and better quality in their production<br />

under different agro-ecological<br />

conditions, at the same time as having<br />

improved food security and meeting<br />

the dietary needs of their families and<br />

livestock. They are broadening the<br />

possibilities for income generation since<br />

they themselves produce the seeds they<br />

need, and as their crops require less<br />

and less chemical inputs since the new<br />

varieties developed through PPB are less<br />

input demanding.<br />

The new locally adapted varieties and<br />

improved lines of crops are giving better<br />

results than other seeds in terms of yield<br />

(see table below), resistance to drought,<br />

resistance to the pest Mosaico Dorado, and<br />

better quality sorghum and beans in terms<br />

of taste, cooking time, and yield of sorghum<br />

flour (more tortillas from less flour).<br />

Farmers are restoring their livelihoods,<br />

reducing their vulnerability, and making<br />

better use of their resources.<br />

The farmers have also had the<br />

possibility to take advantage of the<br />

contribution of scientists and validate<br />

the behaviour of the crosses in the<br />

research centres. Participatory plant<br />

breeding has therefore enabled farmers<br />

to reduce their vulnerability and the<br />

risks that are run with the frequent<br />

changes in climate by having seeds that<br />

are resistant to different factors. This<br />

also results in important savings that<br />

allows them to lower their production<br />

costs, thanks to the production of their<br />

own seed. The table above shows how<br />

yields of maize, beans and sorghum<br />

have increased significantly after<br />

introducing PPB.<br />

6

Santos Luis Merlo Olivera, Community of El Rosario, Pueblo Nuevo.<br />

Santos Luis Merlo Olivera was seriously affected by Hurricane Mitch in 1998. He<br />

has three parcels in an area of six manzanas (measurement of land area). He<br />

grows basic grains and when he can, vegetables. He also has one or two cows<br />

for household consumption. He has access to water on his farm for irrigation,<br />

and he has taken advantage of this for doing trials with participatory plant<br />

breeding during the dry season.<br />

With Mitch, he lost a good part of his land. The soil was washed away by the<br />

water, leaving a rock-strewn field in its wake.<br />

“You can’t do anything with that land now. It’s not even good as a paddock.”<br />

So even after such a long time the impact of hurricane Mitch is felt by<br />

Nicaraguan farmers.<br />

Luis Merlo, however, is now a proud participant in the PPB-MA project.<br />

“The participatory plant breeding project is just what the doctor ordered.<br />

Improving the seeds is very important. We are looking for varieties that can<br />

withstand drought in order to deal with the [climatic] changes.”<br />

A change from using maize as a staple crop towards the more drought resistant<br />

crop, sorghum, has been made by many PPB farmers.<br />

“Sorghum is a substitute for maize and work is being done on varieties that<br />

would be productive, good for feed, resistant, and with a short growing cycle.<br />

They help us through the effects of the drought and bring increased yields.”<br />

Luis Merlo says that through the PPB-MA programme, farmers have acquired<br />

more information and knowledge<br />

on how to adapt and change their<br />

agricultural production in order to<br />

overcome the changing weather<br />

conditions.<br />

”What we have gone through has<br />

made us understand better what the<br />

new practices to take should be.”<br />

Summary<br />

Climate change and variability have, and<br />

will in the future, have great impact on the<br />

lives of small scale farmers in Nicaragua. The<br />

unpredictable rainy seasons have severe effects<br />

for farmers as they lose important crops and<br />

hence income and food. Destructive hurricanes<br />

leave families without houses, devastate roads<br />

cutting people off from markets, school and<br />

other services, as well as destroying crops and<br />

endangering the lives of people and livestock.<br />

The consequences of climate change therefore<br />

increase peoples’ vulnerability.<br />

However, methods for improving<br />

farmers’ adaptive capacity, such as practising<br />

participatory plant breeding and conserving<br />

local biodiversity of plants and crops, have<br />

proved successful. Through participatory<br />

plant breeding, the farmers have had the<br />

opportunity to improve their seeds.<br />

The improved food security also reduces<br />

vulnerability to non-climatic shocks and<br />

changes, since food security is not so vulnerable<br />

to outside stresses due to these new ways of<br />

working. Also nutrition, health and income<br />

levels can improve through securing sufficient<br />

production of foods. Thus the quality of life<br />

of the involved households can be improved<br />

despite lack of other jobs, lack of social security<br />

systems, low and irrelevant education or weak<br />

health care. These vulnerability factors also need<br />

to be changed, but it depends to a large extent<br />

on national governments and international<br />

agencies and organisations. The Project<br />

activities increase the number of livelihood<br />

options which are viable under current socioeconomic<br />

conditions and current climate<br />

variability and change, and people’s capacity to<br />

make use of those opportunities. Thus, such<br />

project activities can be seen as a kind of first aid<br />

measure to reduce poor families’ vulnerability.<br />

Lucia Umanzor, Tresurer of the New<br />

Dawn Cooperative, Cofradía, Pueblo Nuevo<br />

Lucila Umanzor has seen the direct effects of joining the PPB programme. Her<br />

economic situation has improved and she does not have to leave the country<br />

in order to earn enough money to take care of her family. By raising greater<br />

awareness on natural resource management as well as providing farmers with<br />

knowledge on how to do agriculture in a sustainable manner, CIPRES strengthens<br />

farmers’ capacity to adapt to the climate changes as well as other stresses.<br />

“I used to migrate to Costa Rica where I could earn a living. When I found out about<br />

the PPB programme, I decided to stay in Nicaragua and work the land. I have a<br />

small piece of land but me and my husband get a lot from that little piece. Two years<br />

ago there was almost no water in the wells, but now it is returning.”<br />

7

More than Rain<br />

This publication is part of the report<br />

“More than Rain - Identifying sustainable<br />

pathways for climate adaptation and<br />

poverty reduction”.<br />

The first objective of this study is to<br />

look at how climate change impacts<br />

farmers and poor people in the<br />

respective countries. Then it is important<br />

to understand and discuss the links<br />

between climate change adaptation,<br />

development, and poverty reduction<br />

and present the notion of sustainable<br />

adaptation measures. The second<br />

objective is to identify how sustainable<br />

adaptation measures can look like in<br />

specific, on-the-ground development<br />

projects. Finally, it is our aim to<br />

present some guiding principles for<br />

identifying activities and strategies<br />

that both reduce poverty and<br />

increase the capacity of households<br />

and communities to respond to<br />

climatic variability and change. In<br />

order to attain these objectives, it has<br />

been fundamental to get the farmers’<br />

feedback on the experienced climate<br />

risks, causes of vulnerability and their<br />

ability to adapt.<br />

More than rain has been a cooperation<br />

between the Development Fund in<br />

Norway, CIPRES in Nicaragua, REST<br />

in Ethiopia, LI-BIRD in Nepal and the<br />

Global Environmental Change and<br />

Human Security project at the University<br />

of Oslo (GECHS). GECHS has provided a<br />

solid analysis of the work we are doing<br />

which increases our understanding of<br />

what climate change and vulnerability<br />

means for local populations and their<br />

livelihoods.<br />

The full report and case studies can be<br />

downloaded from:<br />

www.utviklingsfondet.no/morethanrain<br />

The information in this presentation<br />

is based on Cabal, S.A.’s report<br />

“Documentation of climate change<br />

for the Development Fund” done in<br />

Nicaragua, and on an analysis of<br />

various climate studies presented in<br />

the report “More than Rain - identifying<br />

sustainable pathways for climate<br />

adaptation and poverty reduction”<br />

made by Global Environmental<br />

Change and Human Security Project<br />

(GECHS) at the University of Oslo.<br />

CIPRES<br />

El Centro para la Promoción, la Investigación y el Desarrollo Rural y<br />

Social (CIPRES) is a Nicaraguan NGO established by people dedicated<br />

to a welfare based economic approach in the Nicaraguan rural areas.<br />

CIPRES works as a socio-economic support center aiming to raise the<br />

living standards of local producers, cooperatives and agricultural<br />

labourers. The organisation cooperates and networks with several other<br />

local, national and international NGOs, national institutions and farmer<br />

unions devoted to agriculture, farmers’ and rural issues. They work<br />

directly with more than 10000 families in 10 departments on the pacific<br />

coast of Nicaragua.<br />

CIPRES supports rural families and rural workers in general, defending<br />

their land rights, improving agricultural production, commercialization<br />

through encouraging small scale farming, diversification of production,<br />

inclusion of women working outside home and development of artisan<br />

work, amongst other things. CIPRES also conducts related studies and<br />

experiments, soil analysis, produce seeds, organise fairs and training<br />

sessions, facilitate the exchange of farmers’ experiences and produce<br />

educational material such as videos and written publications.<br />

The Development Fund (<strong>Utviklingsfondet</strong>) has worked together with<br />

CIPRES for 8 years. The Development Fund and CIPRES collaborate closely<br />

on the implementation of the Participatory Plant Breeding Programme in<br />

Mesoamerica (PPB-MA), as well as other project activities related to the<br />

organisation of rural cooperatives and small-scale farming innovations<br />

and linkages to markets.<br />

The Development Fund is a Norwegian<br />

independent non-government organisation<br />

(NGO). We support environment- and<br />

development projects through local partners<br />

in Asia, Africa and Latin America. We believe<br />

that the fight against poverty must be based<br />

on sustainable management of natural<br />

resources in local communities.<br />

<strong>Utviklingsfondet</strong> / The Development Fund<br />

www.utviklingsfondet.no<br />

8