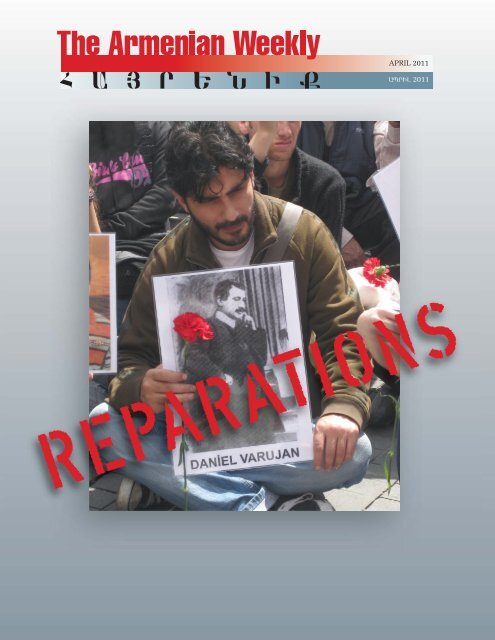

Armenian Weekly April 2011 Magazine

Armenian Weekly April 2011 Magazine

Armenian Weekly April 2011 Magazine

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

ContributorsGeorge Aghjayan is a fellow of theSociety of Actuaries. His primary area offocus is the demographics of westernArmenia and is a frequent contributor tothe <strong>Armenian</strong> <strong>Weekly</strong>. He is chairman ofthe <strong>Armenian</strong> National Committee (ANC)of Central Massachusetts and resides inWorcester with his wife and three children.A graduate of the University ofMichigan Law School and ColumbiaUniversity Graduate School ofJournalism, Michael Bobelian is alawyer and author whose work has coveredissues ranging from corporatewrongdoing to foreign affairs to highereducation. His reportage has appeared on Forbes.com, in theAmerican Lawyer <strong>Magazine</strong>, Legal Affairs <strong>Magazine</strong>, and theWashington Monthly. Bobelian is the author of Children of Armenia:A Forgotten Genocide and the Century-Long Struggle for Justice, thecritically acclaimed book published by Simon & Schuster in 2009.Ayda Erbal is writing her dissertation in thedepartment of politics at New York University.Her work focuses on the politics of changinghistoriographies in Turkey and Israel. She isinterested in democratic theory, democraticdeliberation, the politics of “post-nationalist”historiographies in transitional settings, andthe politics of apology. She is a publishedshort-story writer andworked as a columnist for the Turkish-<strong>Armenian</strong> newspaper Agos from 2000–03.Burcu Gürsel grew up in Istanbul,received her degrees from the University ofChicago and the University of Pennsylvania(Comparative Literature), and currentlyholds a postdoctoral fellowship at Forum Transregionale Studien,Berlin. Who knows where she will be next year. Burcu considers herselfa beginner in things <strong>Armenian</strong>.Marc A. Mamigonian is the Director ofAcademic Affairs of the National Associationfor <strong>Armenian</strong> Studies and Research (NAASR).He is the editor of the publications Rethinking<strong>Armenian</strong> Studies (2003) and The <strong>Armenian</strong>sof New England (2004) and is the author orco-author of several scholarly articles on thewritings of James Joyce.Knarik O. Meneshian was born inAustria. She received her degree in literatureand secondary education in Chicago, Ill.Her works have been published in “TeachersAs Writers,” “American Poetry Anthology,”and other American publications. She hasauthored a book of poems titled Reflections,and translated from <strong>Armenian</strong> to EnglishRev. D. Antreassian’s book The Banishment of Zeitoun andSuedia’s Revolt.Michael Mensoian, J.D./Ph.D, isprofessor emeritus in Middle East and politicalgeography at the University ofMassachusetts, Boston, and a retired majorin the U.S. army. He writes regularly for the<strong>Armenian</strong> <strong>Weekly</strong>.Khatchig Mouradian is a journalist,writer and translator. He was an editor of theLebanese-<strong>Armenian</strong> Aztag Daily from 2000to 2007, when he moved to Boston andbecame the editor of the <strong>Armenian</strong> <strong>Weekly</strong>.He is a PhD student in Holocaust andGenocide Studies at Clark University. HisThe <strong>Armenian</strong> <strong>Weekly</strong>The <strong>Armenian</strong> <strong>Weekly</strong><strong>April</strong> <strong>2011</strong>USPS identificationstatement 546-180ENGLISH SECTIONEditor: Khatchig MouradianCopy-editor: Nayiri ArzoumanianArt Director: Gina PoirierARMENIAN SECTIONEditor: Zaven TorikianProofreaders: Garbis ZerdelianDesigner: Vanig Torikian,3rd Eye CommunicationsTHE ARMENIAN WEEKLY(ISSN 0004-2374)is published weekly by theHairenik Association, Inc.,80 Bigelow Ave,Watertown, MA 02472.Periodical postage paid inBoston, MA and additionalmailing offices.This special publication has aprint run of 10,000 copies.The opinions expressed in thisnewspaper, other than in the editorialcolumn, do not necessarilyreflect the views of THEARMENIAN WEEKLY.Manager: Armen KhachatourianSales Manager: Karine GalstianTEL: 617-926-3974FAX: 617-926-1750E-MAIL:armenianweekly@hairenik.comWEB: www.armenianweekly.com4| THE ARMENIAN WEEKLY | <strong>April</strong> <strong>2011</strong>

articles, interviews and poems have appeared in publicationsworldwide. Mouradian has lectured extensively and participatedin conferences in Armenia, Turkey, Cyprus, Lebanon, Syria,Austria, Switzerland, Norway and the U.S.Originally from a family farm in NorthDakota, Kristi Rendahl lived andworked in Armenia from 1997–2002 andvisits the country whenever possible. Sheworks with non-profit organizations inher consulting practice (www.rendahlconsulting.com)and is pursuing a doctoratein public administration. Through hertravels, she has met <strong>Armenian</strong>s in Lebanon, Syria, Jordan,Ethiopia, and across the U.S. Currently, Kristi resides in St. Paul,Minn. She is a columnist for the <strong>Armenian</strong> <strong>Weekly</strong>.Harut Sassounian is the publisher ofThe California Courier, a weekly newspaperbased in Glendale, Calif. He is the presidentof the United <strong>Armenian</strong> Fund, acoalition of the seven largest <strong>Armenian</strong>-American organizations. He has a master’sdegree in international affairs fromColumbia University and an MBA fromPepperdine He has been decorated by the president and primeminister of the Republic of Armenia, and the heads of the<strong>Armenian</strong> Apostolic and Catholic churches. He is also the recipientof the Ellis Island Medal of Honor.Talin Suciyan is an Istanbul <strong>Armenian</strong>journalist who lived in Armenia from2007–08. She is currently based in Munich,where she is pursuing her graduate studiesand serves as a teaching fellow at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität. She has contributedregularly to Agos (from 2007–10)and other Turkish newspapers.Henry C. Theriault earned his Ph.D. inPhilosophy from the University ofMassachusetts, with a specialization in socialand political philosophy. He is currentlyProfessor in and Chair of the PhilosophyDepartment at Worcester State University,where he has taught since 1998. Since 2007,he has served as Co-Editor-in-Chief of thepeer-reviewed journal Genocide Studies and Prevention and hasbeen on the Advisory Council of the International Association ofGenocide Scholars. His research focuses on philosophicalapproaches to genocide issues, especially genocide denial, longtermjustice, and the role of violence against women in genocide.He has lectured widely in the United States and internationally.Uğur Ümit Üngör is a postdoctoralresearch fellow at the Centre for WarStudies, University College Dublin. He wasborn in 1980 and studied sociology and historyat the Universities of Groningen,Utrecht, Toronto, and Amsterdam. His mainarea of interest is the historical sociology ofmass violence and nationalism in the modernworld. He has published on genocide, in general, and on theRwandan and <strong>Armenian</strong> genocides, in particular. He finished hisPh.D., titled “Young Turk Social Engineering: Genocide,Nationalism, and Memory in Eastern Turkey, 1913–1950” at thedepartment of history of the University of Amsterdam.Tom Vartabedian is a retiredjournalist with the Haverhill Gazette,where he spent 40 years as an awardwinningwriter and photographer. Hehas volunteered his services for thepast 47 years as a columnist and correspondentwith the <strong>Armenian</strong> <strong>Weekly</strong>.He resides with his wife Nancy, a retired schoolteacher. They areparents of three AYF children: Sonya, Ara, and Raffi.We would like to thank the following page sponsorsMr. and Mrs. Onnig and ClarisseChoepdjian, and their children inmemory of their sister and aunt,Nairi TerianMr. and Mrs. Sam and Rina Alajajian,and their children in memory of theirfather and grandfather, Hagop SarianMr. and Mrs. Stephen and AngeleDulgarian in memory of Loutfig andHeranoushe Gumuchian,genocide survivorsMr. and Mrs. Toros and KarenChoepdjian in memory of his father,Arakel CheupdjianMrs. and Mrs. Hovig and SilvaSaghrian, and their children in memoryof their parents and grandparents,Vartevar and Yeghisapet SaghrianMrs. and Mrs. Khoren and SedaAshgian, and their children in memoryof their parents and grandparents,Ashgian and HayrabedianPearl Mooradian in memory of herhusband, Hagop MooradianVahe Kchigian in memory of hisfather, Varujan KchigianZarmuhi Nshanian in memory of herhusband, Hagop “Jack” NishanianVarujan Ozcand

FOR THE RECORDConfiscation & ColonizationTHE YOUNG TURKSeizure of <strong>Armenian</strong>PropertyBy Uğur Ümit Üngör“Leave all your belongings—your furniture, your beddings,your artifacts. Close your shops and businesses with everythinginside. Your doors will be sealed with special stamps. On yourreturn, you will get everything you left behind. Do not sellproperty or any expensive item. Buyers and sellers alike will beliable for legal action. Put your money in a bank in the name of arelative who is out of the country. Make a list of everything youown, including livestock, and give it to the specified official sothat all your things can be returned to you later.You have ten days to comply with this ultimatum.” 1—GOVERNMENT PROMULGATION HANGED IN PUBLIC PLACES IN KAYSERI, JUNE 15, 1915.6‘‘| THE ARMENIAN WEEKLY | <strong>April</strong> <strong>2011</strong>

FOR THE RECORDA 1918 photo of the <strong>Armenian</strong> church in Trabzon, which was used as a depot and distribution center for confiscatedproperty. (Copyright Raymond Kévorkian and Paul Paboudjian, Les Arméniens à la veille du génocide.)INTRODUCTIONThis article is based on a forthcomingmonograph on theexpropriation of OttomanArme nians during the 1915genocide. 2 It will paraphrasesome of the main arguments of the book,which details the emergence of Turkish economicnationalism, offers insight into theeconomic ramifications of the genocidalprocess, and describes how the plunder wasorganized on the ground. The book discussesthe interrelated nature of property confiscationinitiated by the Young Turk regime andits cooperating local elites, and offers newinsights into the functions and beneficiariesof state-sanctioned robbery. Drawing onsecret files and unexamined records fromeight languages, the book presents new evidenceto demonstrate how <strong>Armenian</strong>s sufferedsystematic plunder and destruction,and how ordinary Turks were assigned arange of property for their progress.This two-way policy is captured in thetwo concepts of confiscation and colonization.The book uses the concept of confiscationto capture the involvement of anextensive bureaucratic apparatus and illustratethe legal facade during the dispossessionof <strong>Armenian</strong>s. Furthermore, it willdeploy the concept of colonization todenote the redistribution of their propertyas a form of internal colonization. Together,these concepts best encapsulate the twinprocesses of seizing property from<strong>Armenian</strong>s, and reassigning it to Turks. 3The book is situated in the field of genocidestudies, and starts off by asking questionsthat have been answered fairlysatisfactorily for other genocides such as theHolocaust and the Rwandan Genocide: Wasconfiscation of the victim group’s propertieseconomically motivated as a mere instrumentfor material gain? Did the Young Turkregime distribute <strong>Armenian</strong> property tolocal elites in exchange for support for thegenocide? In other words, did they simplybuy their loyalty by appealing to their senseof economic self-interest? Or did the localelite support the destruction and expropriationout of ideological convictions? Finally,what was the scope of the dispossessionprocess? In other words, how wide was thecircle of profiteurs? Did just the Young Turkelite, from the imperial capital down to theprovincial towns, profit from it, or did muchwider classes in Turkish society benefit?The book consists of seven chapters thatcan be divided into three sections. Chapterstwo and three constitute the first section andwill discuss main issues such as ideology andlaw. Chapter two, entitled “Ideological foundations:constructing the Turkish ‘nationaleconomy,”’ will trace the evolution of theTurkish-nationalist ideology of building apurely Turkish “national economy” withinthe multi-ethnic Ottoman economic landscape.It will discuss how the Young TurkParty envisioned such a Turkish economy tocome into being by analyzing the writings ofleading Young Turk ideologues. Rather thanmacro-economic analyses of Ottomanfinancial policy in the early 20th century, thechapter will investigate how the party imaginedthe role of the state and the economicprogress of the ethnic Turkish population.Immediately following it is chapterthree, entitled “Legal foundations: using thejustice system for injustice.” This chapterwill closely analyze the many laws and<strong>April</strong> <strong>2011</strong> | THE ARMENIAN WEEKLY | 7

Üngördecrees that the Young Turk regime passedto provide a veneer of legality to theircrimes. It will seek to answer the question:Why did the Young Turk regime feel theneed to pass elaborate laws on the status ofwartime <strong>Armenian</strong> property? It will discussnot only the laws that were adopted by theregime, but also the legal status of<strong>Armenian</strong> property. The chapter will distinguishthe legal provenance of land andimmovable property versus movables.Chapter four, “The dispossession of<strong>Armenian</strong>s during the genocide, 1915–1918,”constitutes a section in itself. It will examinethe development of the genocide and traceYoung Turk economic policies towards the<strong>Armenian</strong> population from the Young Turkcoup d’état in 1913 to the fall of the regimein 1918. It will chart how this policy movedfrom boycott to discrimination, into confiscationand outright plunder, resulting in themass pauperization of the victims. It identifiesmain currents and developments of thisruthless policy and how it affected Ottoman<strong>Armenian</strong> communities. The chapter ismeant to be a general introduction to thenext three important chapters.The third and last section of the bookcomprises chapters five and six. They areeach in-depth case studies of several importantprovinces in the Ottoman Empire.Chapter five, “Adana: the cotton belt,” will bethe first of two case studies that describe theorganized plunder of <strong>Armenian</strong>s and thesubsequent deployment and allocation of<strong>Armenian</strong> property to Turks. It will focus onthe southern city of Adana, where<strong>Armenian</strong>s were employed in cotton fields,and describe how the local Young Turks dispossessed<strong>Armenian</strong>s and assigned the propertyto Turkish refugees from the Balkans.Chapter six, “Diyarbekir: the land of copperand silk,” is the second and last case study,concentrating on the southeastern region ofDiyarbekir, famous for its copper and silkproducts. Here, economic life in the bazaarwas dominated by <strong>Armenian</strong> artisans. Thechapter will de scribe how the local perpetratorsparticipated in the destruction of their<strong>Armenian</strong> neighbors and were rewarded bythe central authorities. It will also focus onlarge-scale corruption and embezzlement. 4Finally, chapter seven, the conclusion,will re-center the main questions posed inthis introduction and draw the general conclusionsof each chapter together. It willreport in a direct style how and why the<strong>Armenian</strong>s were dispossessed during thegenocide, how this affected local econo -mies, and how ordinary Turks profitedfrom the expropriation campaign.CONFISCATIONThe <strong>Armenian</strong> Genocide consistedof an overlapping set ofprocesses: elite homicides,deportations, massacres, forcedassimilation, destruction ofmaterial culture, and our current theme,expropriation. Although these dimensionsof the genocide differed and were carriedout by different agencies, they converged intheir objective: destruction. By the end ofthe war, the approximately 2,900 Anatolian<strong>Armenian</strong> settlements (villages, towns,neighborhoods) were depopulated and themajority of its inhabitants dead. Whatmade the massacres genocidal is that thegenocide targeted the abstract category ofgroup identity, in that all <strong>Armenian</strong>s, loyalor disloyal, were destroyed.The qualitative leap in the elimination ofthe <strong>Armenian</strong>s from the Ottoman economyreached an important acceleration with theproclamation of war and the abolishment ofthe capitulations. The abrogation of thecapitulations was a unilateral breach ofinternational law and a catalyst that channelizedhigh levels of power into the YoungTurks’ hands. “Turkification” could now besystematized into a comprehensive empirewidepolicy of harassment, organized boycotts,violent attacks, exclusions fromprofessional associations and guilds, andmass dismissals of <strong>Armenian</strong> employeesfrom the public service and plunder of theirbusinesses in the private sector.The confiscation process began rightafter the deportation of the <strong>Armenian</strong> owners.As a rule of thumb, no prior arrangementswere made regarding the properties.The Committee of Union and Progress(CUP) launched both the deportation andthe dispossession of <strong>Armenian</strong>s well beforethe promulgation of any laws or officialdecrees. The deportation decrees of May23, 1915 and the deportation law of May27, 1915 were issued after the deportationshad already begun. Decrees and lawsmerely served to unite the hitherto diversepractices and render the overall policymore consistent. So too was the CUP’sapproach to confiscation. Telegrams to variousprovinces ordering the liquidation ofimmovable property were followed by thestreamlined program of June 10, 1915 thatestablished the zkey agency overseeing theliquidation process—the AbandonedProperties Commission (Emvâl-ı MetrukeKomisyonu). These were not yet christened“Liquidation Commissions,” but neverthelessmostly fulfilled that function.Officially, there were 33 commissionsacross the country, and in towns without any,the local CUP chapter often took charge ofthe tasks. These consisted of inventorizing,liquidating, appropriating, and allocating<strong>Armenian</strong> property. The most detailed andreliable information we have about the commissionsis from Germans stationedin the Ottoman Empire. For example,Deutsche Bank staff members recognizedthat the Ottoman Bank collaborated in theendeavour. 5 From its correspondence withthe provinces, the German ambassador concludedthat the confiscation process wentthrough two phases: the direct liquidation ofall unplundered <strong>Armenian</strong> property by theAbandoned Properties Commission, and thetransfer of the revenues to the Ottoman Bankthat held responsibility for the money. 6According to André Mandelstam, in 1916 asum of 5,000,000 Turkish lira (the equivalentof 30,000 kilograms of gold) was depositedby the Ottoman government at the Reichs -bank in Berlin. This astronomic amount ofmoney was most probably the aggregate ofall <strong>Armenian</strong> bank accounts, as well as thetotal sum gained from the liquidations in theprovinces. 7 Furthermore, German diplomatsargued that the commissions worked in tandemwith the Grand Vezirate, the FinanceMinistry, and the Justice Ministry. 8 Theentire operation was supervised by theInterior Ministry, which was tasked with anenormous amount of coordination andrecordkeeping. These records have survivedand I will draw on them extensively to outlinethe process of dispossession.At the outset, the problem of propertywas a concomitant effect of the deportationsand there was probably no blueprintfor it written by Talaat Pasha and his henchmen.Throughout 1915 and 1916, the8| THE ARMENIAN WEEKLY | <strong>April</strong> <strong>2011</strong>

FOR THE RECORDInterior Ministry issued hundreds of directives,orders, decrees, and injunctions toprovincial, district, and city authorities.When deportation came, it recorded thenames, professions, and properties of<strong>Armenian</strong>s, before expropriating them andliquidating their immovables. Severalempire-wide decrees sketched the contoursof the confiscation policy. Liquidationentailed auctioning and selling the propertyto the lowest, not highest, bidder. To thisend, on Aug. 29, 1915 the Interior Ministrywired a circular telegram summoningauthorities to auction abandoned <strong>Armenian</strong>strategies to avoid seizure of their property.These included transferring property tonon-Ottoman <strong>Armenian</strong>s, sending it abroadto family members, giving valuables toAmerican missionaries and consuls, mailingit directly to their new residences at theirfinal destinations. It is these kinds of prohibitionsthat shed light on the rationalebehind the expropriations. They stronglysuggest that there was no intention of eithercompensating <strong>Armenian</strong>s fairly for their dispossession,or offering them any prospect ofa future return to their homes. HilmarKaiser has rightly concluded that theseIt is these kinds of prohibitions that shed light on the rationale behindthe expropriations. They strongly suggest that there was no intentionof either compensating <strong>Armenian</strong>s fairly for their dispossession, oroffering them any prospect of a future return to their homes.property for the benefit of the local Turkishpopulation. 9 As this order sufficed for theongoing deportations, preparations weremade for future ones. On Nov. 1, 1915, theministry ordered the drawing up of lists of“<strong>Armenian</strong> merchants from provinces whohave not yet been transported to otherregions,” including details on their tradingfirms, real estate, factories, the estimatedworth of all their belongings, informationon their relatives living abroad, and whetherthey were working with foreign businesspartners. 10 To preclude jurisdictional disputesfrom arising, the ministry admonishedthat the only agency authorized toorganize the expropriation was theAbandoned Properties Commission. 11Talaat and the Interior Ministry hepresided over were soon facing two acuteproblems: ambiguity regarding the formsand provenance of property, and delimitingthe scope of the expropriations. An exampleof the former trend was a questionasked by the provincial authorities ofAleppo, namely whether only Apostolic<strong>Armenian</strong>s were to be expropriated or alsoProtestant and Catholic ones. By then, thedefinition of the victim group had alreadytransformed from a religious definitionbased on the millet system, to a nationaldefinition. Thus, the ministry arbitratedthat the targets were not only Apostolic<strong>Armenian</strong>s but all “<strong>Armenian</strong>s.” 12 TheGerman consul of Trabzon remarked thatunder this law, technically, “an <strong>Armenian</strong>converted to Islam would then be deportedas a Mohammedan <strong>Armenian</strong>.” 13Other provinces wondered what to dowith the property of undeported <strong>Armenian</strong>s,often military families. The ministry orderedthat for now, they would be allowed to keeptheir property. 14 In another case, three governorsasked for advice on how to handle thesowed fields of <strong>Armenian</strong> farmers. The ministryadmitted that the abstract decrees didnot always correspond to the existing conditionson the ground and ordered: “Theseneed to be reaped and threshed under thesupervision of the Abandoned PropertiesCommissions and provided for by the fundsfor the expenses of the settlers. Report withintwo days how many soldiers or labourersfrom the population, and which kinds ofmachines and tools and utensils are neededto harvest the crops.” 15These prescriptive provisions were supplementedby prohibitive rules. Those<strong>Armenian</strong>s who anticipated that the deportationswere a temporary measure countedon renting out their houses, stables, barns, orshops to neighbors and acquaintances. Butthe ministry prohibited this practice. 16 Those<strong>Armenian</strong>s who attempted to sell their propertyto foreigners and other Christians (suchas Greeks or Christian Arabs) were alsocounteracted. It issued a circular telegramprohibiting “decidedly” (suret-i katiyyede)the sale of any land or other property to foreigners.17 Furthermore, the government prohibited<strong>Armenian</strong>s from a whole host ofrestrictions were “a plain admission of officialcriminal intent.” 18A more precise explanation perhaps laysin a revealing telegram sent by the governmentto Balıkesir District. It read that theexpropriation needed to be carried out to“ensure that the transported population willno longer have any connection to possessionsand ownership” (nakledilen ahalininalâka-ı mülkiyet ve tasarrufu kalmamasınıtemîn). 19 In other words, the relationshipbetween <strong>Armenian</strong>s and their propertyneeded to be definitively severed to bringabout a lasting “de-Armenization” of theland. Three years later, the German consulat Trabzon, Heinrich Bergfeld, correctlynoted that the most important decision hadbeen depriving the landowners of the rightto dispose of their immovable property. Atthe end of the war, he reflected on the fate ofthe <strong>Armenian</strong> deportees: “If one believesthey cannot be allowed to definitively returnto their old homes, one should at least givethem the general permission to make use oftheir real estate through sale or rent, andtemporarily allow them to go to their homelandsfor this purpose.” 20 This would turnout to be a naive proposition.<strong>April</strong> <strong>2011</strong> | THE ARMENIAN WEEKLY | 9

FOR THE RECORDThe government offered ordinary Turksincredible prospects of upward social mobility.With a giant leap forward, a nation ofpeasants, pastoralists, soldiers, and bureaucratswould now jumpstart to the level of thebourgeoisie, the “respectable” and “modern”middle classes. The groups who benefitedmost from this policy were the landownersand the urban merchants. 30 When shortagesarose in 1916, the party leadership allowedthat group of merchants close to the party tomonopolize import, supply, and distribution.Defrauda tion and malpracticeoccurred in this alliance by individual partymembers and merchants who enrichedthemselves at the expense of the Istanbulites.As the genocide was raging in full force,Turkish settlers were on their way. Localpreparations were needed in order to lodgethe settlers successfully. The ministry iteratedits request for economic and geographicdata on the emptied <strong>Armenian</strong>villages. In order to send settlers to theprovinces, the local capacities to “absorb”them had to be determined. The InteriorMinistry requested information on thenumber of <strong>Armenian</strong> householdsdeported, whether the emptied villageswere conducive to colonization by settlers,and if so, how many. 31 It also demandeddata on the size of the land, number offarms, and potential number of settlerhouseholds. 32 The books were kept precisely.According to Talaat’s own notebook,in 1915 the amount of property allocatedto settlers was: 20,545 buildings, 267,536acres of land, 76,942 acres of vineyards,7,812 acres of gardens, 703,491 acres ofolive groves, 4,573 acres of mulberry gardens,97 acres of orange fields, 5 carts,4,390 animals, 2,912 agricultural implements,and 524,788 planting seeds. 33Last but not least, the CUP elite tookthe cream of the crop of <strong>Armenian</strong> propertyfor itself. Ahmed Refik observed thecolonization process:Silence reigns in Eskişehir...Theelegant <strong>Armenian</strong> houses around thetrain station are bare as bone. Thiscommunity, with its wealth, its trade,its superior values, became subject tothe government’s order, emptied itshouses...now all emptied houses,valuable rugs, stylish rooms, itsclosed doors, are basically at thegrace of the refugees. Eskişehir’smost modernized and pretty houseslay around the train station...Alarge <strong>Armenian</strong> mansion for theprinces, two canary-yellow adjacenthouses near the Sarısu bridge toTalaat Bey and his friend CanbolatBey, a wonderful <strong>Armenian</strong> mansionin the <strong>Armenian</strong> neighborhood toTopal İsmail Hakkı. All the housesconvenient for residing near the trainstation have all been allocated to theelite of the Ittihadists. 34Even Sultan Mehmed Reşad V receivedhis share. This process of assigning the verybest property to Young Turks was intensifiedafter 1919 by the Kemalists. Indeed,possibly the most important recipient ofthe redistribution of <strong>Armenian</strong> propertieswas the state itself.The various Ministries (Education,Health, Justice) greatly benefited from thecolonization process. The Interior Ministrygranted them permission to choose from<strong>Armenian</strong> property buildings it wanted touse as their offices. The state, led by theCUP, was lavished with property up to thehighest levels. A famous example of confiscated<strong>Armenian</strong> property is the story of theKasabian vineyard house in Ankara. InDecember 1921, amidst the Greco-TurkishWar, Mustafa Kemal was touring the areawhen he noticed the splendid house of thewealthy Ankara jeweler and merchantKasabian. The house had been occupied bythe noted Bulgurluzâde family after theKasabians had been dispossessed anddeported. Mustafa Kemal liked the houseand bought it from Bulgurluzâde TevfikEfendi for 4,500 Turkish lira. From then on,the compound has been known as theÇankaya Palace (Çankaya Köşkü), theofficial residence of the president of Turkeyup to today. 35 CONCLUSIONThe expropriation of Ottoman<strong>Armenian</strong>s was necessary for thedestruction process in general.Dispossessed and up rooted, theOttoman Arme nians’ chances ofsurvival and maintenance gradually shrunkto a minimum. Every step in the persecutionprocess contributed to the weakening andemasculating of <strong>Armenian</strong>s. It robbed themnot only of their possessions, but also ofpossibilities for escape, refuge, or resistance.The more they were dispossessed, the moredefenseless they became against Young Turkmeasures.The structure of this process can be analyzedat three levels: the macro, meso, and<strong>April</strong> <strong>2011</strong> | THE ARMENIAN WEEKLY | 11

Üngörmicro-levels, bearing in mind the relevantconnections between the three levels. Themacro-level concerns the context and structureof the political elite that led the empire towar and genocide. They launched the policiesout of ideological conviction: the war offeredan indispensable opportunity to establish the“national economy” through “Turkification.”They created a universe of impunity in whichevery institution and individual below themcould think of <strong>Armenian</strong>s as outlawed andtheir property as fair game, up for grabs. If itis the opportunity that creates the crime, thenTalaat created an opportunity structure inwhich ordinary Turks came to plunder on amass scale.Now the second level enters into force.Within the structure of national policy werenestled developments such as complex decision-makingprocesses, the necessity andlogic of a division of labor, the emergence ofspecialized confiscation units, and the segregationand destruction of the victim group.This level was characterized by competition,contestation, and clashes over coveted property.Local elites and state institutions suchas the army, several ministries, the fiscalauthorities, the provincial government, andthe party, collaborated for their own reasons.The main agencies were the police, militia,and civil administration. Several ministrieswere involved in the expropriation processand benefited greatly from it, most notablythe Ministries of Education, Justice, Finance,Health, and Interior. The Ottoman Bankand the Agricultural Bank exploited theprocess unscrupulously for their own ends.The effects of the economic war against the<strong>Armenian</strong>s raise questions about the implicationof these institutions.At the micro-level, the process facilitatedhundreds of thousands of individualthefts of deported victims, carried out byordinary Turks. The mechanisms that propelledplunder were horizontal pull-factorsand incentives (zero-sum competition withother plunderers), and vertical pressure(the beginning of the process did not containprecise decrees but was open for liberalinterpretation). Thus, ordinary Turks profitedin different ways: Considerable sectionsof Ottoman-Turkish society werecomplicit in the spoliation. Whereas in thecountryside a Hobbesian world ofunchecked power was unleashed, in thecities, the CUP launched a more careful,restrained path due to firmly establishedand complex social and bureaucratic structures.This level is in particular importantto study the material benefits that accruedto figures within the Young Turk Party. Inan in-depth study of the phenomenon ofclass in Turkey, Çağlar Keyder concludedthat “there was usually one-to-one correspondencebetween the roster of theCommittee of Union and Progress localorganization and the shareholders of newcompanies.” 36 Yusuf Akçura too, reflectedafter the war on the CUP’s economic policiesin the past decade and concluded thatin Anatolia, “the Muslim real estate ownersand business elite have completelyembraced the Committee of Union andProgress.” 37 These arbitrary, corrupt, andnepotistic activities took place behind thejuridical facade of government decree.But history is full of unforeseen andunintended consequences of policies andideologies. The great unintended consequenceof the Young Turk government’sdispossession of <strong>Armenian</strong>s was the opportunityit offered local Turks for self-enrichment.To the Interior Ministry, this was notacceptable nor accepted: Individual embezzlerswere punished by having their rights to<strong>Armenian</strong> property revoked. Those with tiesto local Young Turk Party bosses or enoughsocial status and potential to mobilize peoplegot away with their “crime within a crime.”One can perhaps even conclude that theYoung Turk government bought the domesticloyalty of the Turkish people throughthese practices—initially irresponsible, thenoutright criminal. The <strong>Armenian</strong> Genocidewas a form of state formation that marriedcertain classes and sectors of Ottoman societyto the state. It offered those Turks a fasttrackto upward social mobility. So the knifehad cut both ways, for the Young Turk movementrepresented the drive to couple socialequality with national homogeneity andpolitical purity.As <strong>Armenian</strong>s went from riches toruins, Turks went from rags to riches. But<strong>Armenian</strong> losses cannot simply beexpressed in sums, hectares, and assets. Theideology of “national economy” did notonly assault the target group economically,but also in their collective prestige, esteem,and dignity. Apart from the objective consequencesof material loss, the subjectiveexperiences of immaterial loss were inestimable.Proud craftsmen, who had oftenfollowed in their ancestors’ footsteps ascarpenters, cobblers, tailors, or blacksmiths,now lost their livelihoods. Thegenocide robbed them not only of theirassets but also of their professional identities.Zildjian, the world’s largest cymbalproducer, was headed by two brothers who12| THE ARMENIAN WEEKLY | <strong>April</strong> <strong>2011</strong>

FOR THE RECORDescaped persecution because during thewar they happened to be in the UnitedStates. 38 The Zildjians are world famousand renowned. But entire generations ofother famous artisan families disappearedwith their businesses, extinguishing thename and quality of certain brands. Gonewere the Dadians, Balians, Duzians,Demirjibashians, Bezjians, Vemians,Tirpanjians, Shalvarjians, Cholakians, andmany other gifted professionals.The assets of these and other Arme -nians were re-used for various purposes:settling refugees and settlers, constructingstate buildings, supplying the army, andindeed, the deportation program itself.This leads me to the grim conclusion thatthe Ottoman <strong>Armenian</strong>s financed theirown destruction. aENDNOTES1 Mae M. Derdarian, Vergeen: A Survivor of the<strong>Armenian</strong> Genocide (Los Angeles: Atmus, 1996),p. 38.2 Uğur ܢmit Üngör and Mehmet Polatel,Confiscation and Destruction: The Young TurkSeizure of <strong>Armenian</strong> Property (London/NewYork: Contin uum, <strong>2011</strong>).3 For an argument along these lines, see: DonaldBloxham, “Internal Coloniza tion, Inter-imperialConflict and the <strong>Armenian</strong> Genocide,” in: A.Dirk Moses (ed.), Empire, Colony, Genocide:Conquest, Occupation, and Subaltern Resistancein World History (New York: Berghahn, 2008),pp. 325–342.4 For a study of Young Turk rule in Diyarbekir,see: Uğur Ümit Üngör, The Making of ModernTurkey: Nation and State in Eastern Anatolia,1913–1950 (Oxford: Oxford University Press,<strong>2011</strong>).5 Politisches Archiv Auswärtiges Amt (GermanForeign Ministry Archives, PAAA), BotschaftKonstantinopel 98, Bl. 1–3, Deutsche BankIstanbul branch to Germany embassy, Nov. 17,1915.6 PAAA, Botschaft Konstantinopel 96, Bl. 98-105,Hohenlohe-Langenburg to Erzurum, Sept. 3,1915.7 André Mandelstam, La Société des Nations et lesPuissances devant le problème arménien (Beirut:Association Libanaise des UniversitairesArméniens, 1970), pp. 489–493.8 PAAA, Botschaft Konstantinopel 98, Bl.4, Vice-Consul Ziemke to Istanbul Consulate, Nov. 16,1915.9 Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi (Ottoman PrimeMinisterial Archives, BOA) DH.ŞFR 55/330,Interior Ministry to all provinces, Aug. 29, 1915.10 BOA, DH.ŞFR 57/241, Interior Minis try to allprovinces, Nov. 1, 1915.11 BOA, DH.ŞFR 57/61, Interior Ministry toEski ehir, Oct. 17, 1915.12 BOA, DH.ŞFR 57/37, Interior Ministry toAleppo, Oct. 16, 1915.13 Quoted in: Ara Sarafian (ed.), United StatesOfficial Records on the <strong>Armenian</strong> Genocide1915–1917 (London: Gomidas Institute, 2004), p.154.14 BOA, DH.ŞFR 70/79, Interior Ministry toDiyarbekir, Nov. 23, 1916.15 BOA, DH.ŞFR 54/301, Interior Min istry to Sivas,Diyarbekir, Mamuret-ul Aziz, July 5, 1915.16 BOA, DH.ŞFR 56/269, Interior Ministry toCanik, Oct. 3, 1915.17 BOA, DH.ŞFR 55/280, Interior Ministry to allprovinces, Aug. 28, 1915.18 Kaiser, “<strong>Armenian</strong> Property,” p. 68.19 BOA, DH.ŞFR 55/66, Interior Ministry to Karesi,Aug. 17, 1915.20 PAAA, R14104, Trabzon consul Bergfeld toReichskanzler Hertling, Sept. 1, 1918.21 Hilmar Kaiser, “Genocide at the Twilight of theOttoman Empire,” in: Donald Bloxham & A.Dirk Moses (eds.), The Oxford Handbook ofGenocide Studies (Oxford: Oxford UniversityPress, 2010), pp. 365–385.22 Kerem Öktem, “The Nation’s Imprint:Demographic Engineering and the Change ofToponymes in Republican Turkey,” in:European Journal of Turkish Studies, vol.7(2008), at: http://ejts.revues.org/index2243.html.23 BOA, DH.ŞFR 59/239, Interior Ministry to allprovinces, Jan. 6, 1916.24 BOA, DH.ŞFR 60/129, Interior Ministry toTrabzon, Jan. 26, 1916.25 BOA, DH.ŞFR 60/275, Interior Ministry toKayseri, Feb. 8, 1916.26 BOA, DH.ŞFR 61/31, Talaat to all provinces, Feb.16, 1916.27 BOA, DH.ŞFR 64/39, Interior Ministry to allprovinces, May 16, 1916.28 According to one study, the CUP’s economic“Turkification” official, Kara Kemal, set up 70firms during the war. Osman S. Kocahanoğlu,İttihat-Terakki’nin Sorgulanması ve Yargı lanması(Istanbul: Temel, 1998), p. 33.29 “Ey Türk! Zengin ol,” in: İkdam, Jan. 11, 1917.30 Çağlar Keyder, “İmparatorluk’tan Cumhuriyet’eGeçişte Kayıp Burjuvazi Aranıyor,” ToplumsalTarih, vol.12, no.68 (1999), pp. 4–11.31 BOA, DH.ŞFR 53/113, Interior Ministry to allprovinces, May 25, 1915.32 BOA, DH.ŞFR 59/107, Interior Ministry toAnkara, Bursa, Kayseri, Konya, and Sivas, Dec.27, 1915.33 Murat Bardakçı, Talât Paşa’nın Evrak-ıMetrûkesi (Istanbul: Everest, 2008), p. 95.34 Ahmed Refik, Kafkas Yollarında: ki Komite İkiKıtâl (Istanbul: Temel, 1998), p. 136.35 Soner Yalçın, “Çankaya Köşkü’nün ilk sahibiErmeni’ydi,” Hürriyet, March 25, 2007.36 Çağlar Keyder, State and Class in Turkey: AStudy in Capitalist Develop ment (London:Verso, 1987), p. 63.37 Yusuf Akçuraoğlu, Siyaset ve ktisad HakkındaBirkaç Hitabe ve Makale (Istanbul: Yeni Matbaa,1924), p. 27.38 See www.zildjian.com/en-US/about/timeline.ad2.<strong>April</strong> <strong>2011</strong> | THE ARMENIAN WEEKLY | 13

FOR THE RECORDSHATTERING50 YEARS OF SILENCE1965 and the birth of the modern campaign for justiceBy Michael BobelianOn the morning of <strong>April</strong> 24, 1965, students from Yerevan’s universitiesskipped class. At a time and place when poets were nearly as popularand influential as celebrities are today, one of Soviet Armenia’s greatestpoets recited his defiant poem written for the 50th anniversary ofthe genocide in a small theatre: “We are few, but we are called<strong>Armenian</strong>s.” Baruyr Sevag’s poem exclaimed that no matter how few orweak <strong>Armenian</strong>s may be in the world, no matter how “death had fallen inlove” with this ancient tribe, they shall “feel proud” for being <strong>Armenian</strong>s. Thefinal line of his poem cried out defiantly that the <strong>Armenian</strong>s would grow andthrive, now and forever: “We are, we shall be, and become many.” Dead silencefollowed. Few had heard such exclamatory speeches within the rigid confinesof Soviet life before. Doing so usually meant chastisement or worse,imprisonment. The students in the audience, infused with stridency after listeningto the poem, then left the theatre to join other students acrossYerevan to make their way to the city center for an unprecedented undertaking.They were about to make history by partaking in the first major publiccommemoration of the <strong>Armenian</strong> Genocide.<strong>April</strong> <strong>2011</strong> | THE ARMENIAN WEEKLY | 15

BobelianEarlier in the day, the Catholicos, whoselong graying beard and gentle eyes gavehim a grandfatherly appearance that addedto his palpable spirituality, had overseen amemorial prayer commemorating thegenocide overflowing with attendees at theChurch’s headquarters.The youth descending on the center ofSoviet Armenia’s capital wanted more thanprayers to mark this occasion. They wantedpolitical action. Carrying signs that read “Ajust solution to the <strong>Armenian</strong> Question”and “Our lands” along with enlarged photosof genocide victims, the students, joined bytheir professors and Soviet Armenia’s leadingintellectuals, artists, and writers, poppedin to businesses and homes to recruit otherson this sunny day during which a wispyspring breeze kept the shade cool. With noprevious experience in organizing demonstrations—one participantdescribed the students’ tactics as “primitive”—the processionfumbled along to Lenin Square driven as much, if not more, bycuriosity as militancy. Various government buildings and the city’sbest hotel ringed the oval-shaped public space used to hold communistrallies. Gathering in front of a granite Lenin statue erectedduring World War II—the largest of the ubiquitous iconic shrinesdotting the U.S.S.R—the students saturated the square and soonspilled into the adjacent streets. The demonstrators muddled theirway through the city as some sang nationalistic songs, while othersscreamed a cacophony of anti-Turkish declarations.Though free of Joseph Stalin’s terror, this was still the SovietUnion, a place where propaganda monopolized every facet of publiclife. Newspapers like Pravda published the government’s credos.Kinder garteners through university graduates studied and regurgitatedthe canonic teachings of Marx and Lenin. Government officialsauthorized public events staged to conform to this strict dogma. Thisdemonstration had received no such permission from the state. Theprotestors understood that this one act might permanently derailtheir careers, placing them in shabby homes and dreary jobs insteadof leading government ministries. They knew that many could bearrested, or worse, jailed or banished to Siberia to suffer in isolationand exile. The sight of KGB officers in plain sight further fueled theirfears. Though nervous and worried, they pressed on. Thegroundswell of emotion on this day was simply too strong.Holding the largest concentration of <strong>Armenian</strong>s in the world,Soviet Armenia would have been best suited to press the <strong>Armenian</strong>case against Turkey. If the first <strong>Armenian</strong> Republic had thrived, itcould have pursued reparations and human rights trials against theYoung Turks, and maintained territorial claims against Turkey. Butthe republic gave way to a rigid Soviet policy that reduced politicalactivity by the population of Soviet Armenia to a standstill—evenwhen it came to the genocide. The U.S.S.R. had prohibited <strong>Armenian</strong>scholars from studying the tragedy. It extinguished any chance oferecting a public memorial. It censored those who brought up thetopic. And it refused to sponsor <strong>Armenian</strong> claims against Turkey.As the setting sunformed a silhouettebehind Mount Ararat,the crowd, nowbulging to 100,000,surrounded the greystonedopera house atthe center of the cityadorned with Greekcolumns, arches,and semicircularlayers sitting atopeach other.Geo-political interests in corrallingTurkey away from its NATO alliance did notcompletely explain Soviet policy. WhenLenin and his ideological brethren broughtcommunist revolution to Russia, they envisioneda world in which Soviet citizenswould, in due time, cast off their allegiancesto ethnicity and religion. This vision of theSoviet citizen had no room for nationalisticaims. As a uniquely <strong>Armenian</strong> saga, the genocidedid not accord to this ecumenical communistideology. Soviet authorities tookevery means to smother any talk of the genocide,even among those who lived throughthe tragedy.Yet, on this day, <strong>Armenian</strong>s refused tostand silent any longer.As the setting sun formed a silhouettebehind Mount Ararat, the crowd, nowbulging to 100,000, surrounded the grey-stoned opera house at thecenter of the city adorned with Greek columns, arches, and semicircularlayers sitting atop each other. By now, survivors of thegenocide had joined the crowd, injecting the younger protestorswith added adrenaline. To appease the growing demand for a publiccommemoration, authorities had decided to hold a modest ceremonyfor about 250 people in the opera house. Though the KGBvetted the guest list to prevent any unexpected incidents, it tookimmense lobbying by Soviet Armenia’s leadership to their superiorsin Moscow to proceed with the event.Inside the performance hall, leading representatives of theSoviet <strong>Armenian</strong> government convened along with the Catholi cos.A senior government official spoke first, followed by a world-classastrophysicist. Compared to the reserved performance inside theopera house, the demonstrators listening on loudspeakers outsidehad grown rowdy, choking off transportation in Yerevan and shuttingdown universities and businesses. Though tame compared tothe riots of America and Europe during the 1960’s—with no looting,widespread vandalism, or violence—the demonstration heatedup as organizers delivered speeches insisting on Soviet sponsorshipof <strong>Armenian</strong> demands. The protestors wanted to submit a petitionto those inside the opera house. When the guards refused to grantthem entry, the students pushed against the barricades placed infront of the opera house and threw stones at its windows. Aftersome deliberation, the authorities declined to call in the army,instead employing the municipal security force to entangle with theprotestors to avoid bloodshed. The sight of their sons and daughtersin the crowd made some officers reluctant to move against the protestorswith alacrity. Embarrassment turned others away from facingtheir children. Instead, firemen blasted high-powered hosesfrom the building’s windows to keep the demonstrators at bay.These proved feeble in the face of the energized crowd. Pumpingtheir fists into the air, the demonstrators repeatedly shouted “Ourlands, our lands” in a chorus.When the astrophysicist finished, the crowd outside grewincreasingly antagonistic. The opera’s windows shattered amidst the16| THE ARMENIAN WEEKLY | <strong>April</strong> <strong>2011</strong>

FOR THE RECORDcontinuous volley of missiles. Soaked in water, the demonstratorsfinally overwhelmed the barriers, barging into the main hall andflooding it with screams. Shocked by the population’s strong resolvefor action, most everyone in attendance fled from a rear exit of thebuilding. The Catholicos remained behind. Respect for his positiontemporarily silenced the boisterous crowd. “My dear children,” hestarted to tell the restless listeners in his grandfatherly way. Before hegot more than a few words out, shouts and jeers continued.The leaders of Soviet Armenia elected not to order massarrests. Within a year, however, the fallout from the unexpecteddemonstration led to their downfall as the chieftains in Moscowinstalled more stringent satraps to quash such nationalistic outbursts.The Soviet government’s only concession to the <strong>Armenian</strong>fervor was to erect a memorial honoring the victims of the genocide.But it refused to do anymore. It would neither alter its foreignpolicy nor sponsor <strong>Armenian</strong> claims against Turkey. As such,Soviet Armenia never again served as a staging point for the<strong>Armenian</strong> quest for justice. Instead, the demonstration’s biggestimpact came not in changing the policy of the U.S.S.R., but servingas an inspiration for <strong>Armenian</strong>s throughout the diaspora. Andit was the diaspora—and not Soviet Armenia—that struggled forjustice for decades to come.* * *President Herbert Hoover wrote in his memoir: “ProbablyArmenia was known to the American school child in 1919only a little less than England.” That was no longer true in1965. A human rights disaster that had inspired the firstmajor international humanitarian movement had largely disappearedfrom the world’s consciousness by its 50th anniversary.One could not find a single museum, monument of noteworthiness,research center, or even a comprehensive publication aboutthe genocide.On the 50th anniversary of the genocide, the <strong>Armenian</strong>s of thediaspora were finally prepared to take that extraordinary stepneeded to remind the world of the forgotten genocide. In Beirut, allof the <strong>Armenian</strong> political parties came together to speak in front of85,000 people packed inside a stadium. Thousands marched in centralAthens. In Paris, <strong>Armenian</strong>s marched down the ChampsElysees; 3,000 attended a memorial mass in Notre Dame. More than12,000 participated in Buenos Aires. <strong>Armenian</strong>s in Milan, Montreal,Syria, Egypt, and Australia also staged events, as did <strong>Armenian</strong>Americans. Boston’s <strong>Armenian</strong>s held a ceremony in a Catholiccathedral as well as a rally in John Hancock Hall. In San Francisco,300 mourners marched in silence to a cathedral; others held a vigilin front of City Hall. <strong>Armenian</strong>s held events in Illinois, California,Connecticut, Michigan, New Jersey, Wis consin, Massachusetts,Rhode Island, Washington, D.C., Ohio, Virginia, and smaller communitiesthroughout the country.Few people encapsulated the meaning of the genocide to a newgeneration more than Charles Metjian, who organized a demonstrationin New York. The 30-something fire departmentemployee was not much of a 1960’s radical. Despite caring for agrowing family and working two jobs, however, he took it uponhimself to organize a march to the United Nations. Metjian hadnever met his grandfather, yet the sight of his childhood friendsinteracting with their own made him long for the mythical patriarch.The childhood stories Metjian had heard of how Ottomansoldiers had hacked his grandfather’s body to pieces outside hishome, cutting off his arm and finally killing him with a blow tothe head, remained etched in Metjian’s mind. The bind betweengrandfather and grandson—between a victim and his descendant—remainedstrong despite the passage of 50 years. “Time hasneither changed nor lessened this crime…committed againstyou,” Metjian wrote in an open letter to the grandfather he hadnever known. “I vow I will make every effort to make fruitful thejustice that is long overdue to you.”Metjian urged others to join him. “The choice is yours,” hewrote to all <strong>Armenian</strong>s before the <strong>April</strong> 24th march. “He who callshimself an <strong>Armenian</strong> comes to this Bridge; either he crosses it and“He who calls himself an<strong>Armenian</strong> comes to this Bridge;either he crosses it and Honorshis people or he falls back anddissipates himself from hisHeritage.”Honors his people or he falls back and dissipates himself from hisHeritage.” Metjian’s message was clear: All <strong>Armenian</strong>s, no matterhow far removed in time and space from the dark days of 1915,owed it to their ancestors to fight for justice.Numerous pamphlets rehashing old arguments of resurrectingthe Treaty of Sèvres went out to governments across the world. Butsomething was different. The genocide began to take on a life of itsown, detaching itself from the broader historical narrative that haddefined the contours of <strong>Armenian</strong> claims against Turkey in thepast. Historically, <strong>Armenian</strong>s had linked the genocide to theirdesires for their ancestral lands and to a specific place, a homeland,where they would be entitled to self-rule and self-determination.That link remained, but starting in 1965, it began to come apart. Adecade or two later, <strong>Armenian</strong>s hardly mentioned the pledges ofthe post-World War I era in their pursuit of justice; instead, theyfocused almost exclusively on the genocide as a distinct event. Nolonger confined to <strong>Armenian</strong> families and community gatherings,the catastrophe became the focal point of <strong>Armenian</strong> political aspirations,a never-ending source of mobilization replenished byTurkish denial. As other cultural markers faded or lost their appealto a younger, assimilating population, the genocide and the pursuitof justice associated with it gradually displaced the longing for ahomeland as a central element of <strong>Armenian</strong> identity.This new focal point for political action combined with heightenedpolitical awareness not seen since the post-World War I era<strong>April</strong> <strong>2011</strong> | THE ARMENIAN WEEKLY | 17

Bobeliantranslated into action. The Illinois, California, and Massachusettslegislatures passed resolutions marking the genocide, as did a myriadof cities and towns. Forty-two Congressman, including SenatorEdward Kennedy (D-Mass.), honored the 50th anniversary inAmerica’s most hallowed legislative chamber.* * *The Turkish response to this unexpected uprising verged onthe hysterical. After many years in which news of <strong>Armenian</strong>sbarely registered in Turkey, the flurry of activity in 1965 sentshockwaves through Turkey’s ruling elite. Turkish newspapersissued bitter denunciations. Diplomats countered Arme n ianclaims in the press. The Turkish Embassy urged the State Departmentto squash declarations made on behalf of the <strong>Armenian</strong>s byAmerican politicians. Its ambassador asked for the removal of a tinygenocide monument erected at an <strong>Armenian</strong> senior citizen center inNew Jersey because, he insisted, despite being on private property, itwas “easily visible to all passersby on a busy street corner and, therefore,legally public property.” Some Turkish officials, unable to appreciatethat the American government could not simply ban protestors,blamed the U.S. government for the demonstrations.A member of the Turkish Embassy in Washington urged readersof the New York Times that in dealing with the “dark days…thebest thing to do now would be to forget them….” That was just theproblem. Turkey wanted to forget a past that <strong>Armenian</strong>s could notforget. Too many survivors lived on with traumatic memories thatrefused to fade away. Too many of their children and grandchildrenheard stories of lost relatives, tormented deaths, and a neverendingdespair that 50 years had failed to heal. By obliteratingtheir shared past, Turkey was erasing the defining event of the<strong>Armenian</strong> experience. One group could not get its way withoutforcing the other to overturn decades of memories. The irreconcilablepositions could only result in one victor and one loser.* * *Just as the resurrection of the genocide began, the Cold Wardivisions that had divided the <strong>Armenian</strong> Diaspora began tofade. Though <strong>Armenian</strong> factions remained deeply suspiciousof each other, the détente between the United States and theSoviet Union filtered down to the <strong>Armenian</strong>s. There was even talkof Church unity.The <strong>Armenian</strong> Revolutionary Federa tion (ARF), the most politicallyengaged segment of the community, shifted its policy. While itremained steadfastly anti-Soviet, its Cold War agenda began torecede as the genocide took prominence, making the quest for justiceagainst Turkey, and not the Soviet Union, the party’s primaryaim. The death of its leadership held over from the <strong>Armenian</strong>Republic—like Simon Vratsian and Reuben Darbinian—during the1960’s contributed to this shift as the ARF turned its significantpolitical connections and mobilization efforts to the genocide.Likewise, the aspirations of the survivor generation of returningto the lost homeland offered little appeal for their descendantswho had never lived on <strong>Armenian</strong> soil. The generation that cameof age after the genocide had set roots in new nations. The sentimentalattachment to a mythical homeland did not remain.William Saroyan reflected the psyche of this generation. Born inCalifornia, in 1964 he travelled to the home of his ancestors inBitlis, Turkey, after numerous attempts over a span of many years.Despite finding the very spot of his family’s house, Saroyan realizedthat his family’s roots had been completely torn out. No foundationremained to make his return possible. “I didn’t want toleave,” Saroyan said of his visit. “But it’s not ours.”Swayed by the civil rights, student rights, and anti-war movements,the <strong>Armenian</strong> youth in America viewed the genocide asanother injustice to fight for, an injustice for which they maintaineda personal investment. They refused to cower meekly likethe survivors. Instead, having inherited a sound economic andcommunal foundation from the survivors who had spent theirlives rebuilding, they possessed the luxury to mount a politicalcampaign. The experience of the genocide manifested itself differentlyin these younger generations. The psychologicaldefenses used to contend with and evade the persistent strain ofthe genocide had contributed to the silence of the survivors.Their offspring had not witnessed its horrors first-hand, and assuch, had the necessary detachment to reawaken the forgottenepisode of history. At the same time, with only a generation ortwo between survivors and the children of the 1960’s, the psychologicalscars of the genocide endured. The ongoing failure toestablish truth prohibited the natural healing process from takingeffect.In an era when many Americans began to search for their roots,<strong>Armenian</strong> Americans inevitably confronted the genocide at everyturn. They came to realize that so much of who they were was begottenin the apocalyptic days of 1915. The rise of identity politics, amovement that came to prominence in the 1960’s, in which groupsbegan to come together and identify themselves by shared historicalgrievances, encouraged the younger <strong>Armenian</strong>s’ campaign for justice.An overpowering sense of obligation to their ancestral legacyalong with its unresolved trauma gave them the sustained emotionalenergy needed to carry on a decades-long struggle with Turkey.Instead of the genocide’s horrors ceasing with the death of the survivors,these horrors transplanted into their descendants and overshadowed<strong>Armenian</strong> identity for generations to come.* * *Leading up to 50th anniversary of the genocide, several<strong>Armenian</strong> American newspapers published a long essayauthored by the gifted writer, Leon Surmelian. “The time hascome for <strong>Armenian</strong>s to stand up and be counted,” Surmeliannoted. “For too long now we have been the forgotten people of thewestern world. And we deserve to be forgotten if we take no action,now.” Surmelian was correct: The world had forgotten the<strong>Armenian</strong>s.Starting in 1965, <strong>Armenian</strong>s across the world, whether inSoviet Armenia or the diaspora, whether partisan or apolitical,resurrected the genocide from its dormancy and refused to remainforgotten any longer. a18| THE ARMENIAN WEEKLY | <strong>April</strong> <strong>2011</strong>

FOR THE RECORDA Demographic Narrative ofDIYARBEKIRPROVINCEBased on Ottoman RecordsBy George Aghjayan‘‘My central argument is thatthere is no majorcontradiction not only between differentOttoman materials, but also betweenOttoman and foreign archival materials. So,it is erroneous to assume that the Ottomandocuments (referring here mostly to thedocuments from the Prime MinistryArchive) were created solely in order toobscure the actions of the Ottomangovernment ...Ottoman archival materialssupport and corroborate the narrative of<strong>Armenian</strong> Genocide as shown in thewestern Archival sources.” (Emphasis mine)—TANER AKCAM IN “THE OTTOMAN DOCUMENTSAND THE GENOCIDAL POLICIES OF THE COMMITTEEFOR UNION AND PROGRESS (ITTIHAT VE TERAKKI)TOWARD THE ARMENIANS IN 1915,”GENOCIDE STUDIES AND PREVENTION, 1:2,(SEPTEMBER 2006): 127–148.BACKGROUNDAfter reading the above by Historian Taner Akcam, it occurred tome that similar assumptions are reflected in the study of pre-World War I populations within the Ottoman Empire. This is particularlytrue of the various estimates of the <strong>Armenian</strong> populationprior to the <strong>Armenian</strong> Genocide.To date, those studying the <strong>Armenian</strong> population of theOttoman Empire have either accepted Ottoman registrationrecords as the sole source for analysis while dismissing the recordsof the <strong>Armenian</strong> Patriarchate, or vice versa. Occasionally, the “suspect”records are critiqued prior to dismissal, but more often thannot they are dismissed superficially or ignored altogether.Using the Diyarbekir province as an example, I plan to analyzeunder what scenarios Ottoman government and <strong>Armenian</strong>Patriarchate records are consistent and thus complimentary.SOURCESThere existed within the Ottoman Empire a long tradition of taxregisters. Throughout the 19th century, a more ambitious registrationsystem developed. At first, adult males were the primary objectivefor tax and military objectives. Later efforts can be viewed asthe foundation for demographic analysis and governmental policydecisions. However, even with gradual improvements in enumeration,the Ottoman registration system never approached full coverageof the population.<strong>April</strong> <strong>2011</strong> | THE ARMENIAN WEEKLY | 19

AghjayanWhile not exhaustive, the following are some of the weaknessesin the data gleaned from Ottoman records:d Women and children were undercounted;d Registers containing non-Muslims have never been analyzed(only summary data have come to light thus far);d Registration systems are inherently inferior to a census;d The sparseness of data complicates evaluation;d There is some evidence of manipulation;d Borders between districts and provinces frequentlychanged and thus complicate comparisons;d While detailed records do not exist, summary informationhas appeared in a number of sources, primarily inOttoman provincial yearbooks and governmentdocuments.During this same period and for many of the same reasons, the<strong>Armenian</strong> Patriarchate began an effort at enumerating the <strong>Armenian</strong>population. Similarly, there are inherent weaknesses in the patriarchatedata that include, but are not limited to, the following:d Population estimates for Muslims were often includedeven though the patriarchate had no way of gatheringsuch data;d The patriarchate censuses were often timed with politicalobjectives;d The sparseness of data makes it difficult or impossible todevelop a population timeline;d Detailed records are lacking and there is little hope furtherdata will come to light;d There is evidence of undercountingchildren and other gaps in data.The primary source for patriarchate datafor 1913–14 can be found in two sources:Raymond H. Kevorkian and Paul B.Paboudjian’s “Les Armeniens dansl’Empire Ottoman a la veille du genocide”(Paris: Les Editions d’Art et d’HistoireARHIS, 1992) and Teotik, “Goghgota HaiHogevorakanutian” ed. Ara Kalaydjian(New York: St. Vartan’s Press, 1985).ANALYSISWhile most scholars have used theOttoman statistics unadjusted or made simpleaggregate level adjustments, historianJustin McCarthy utilized stable populationtheory in an attempt to compensate for theknown deficiencies. McCarthy’s work isoften cited with frequent praise and occasionalcriticisms, but rarely from a mathematicalperspective.40,00035,00030,00025,00020,00015,00010,0005,0000Ages0–4Ages5–9McCarthy utilizes age-specific data from the early 1890’s tocalculate an adjustment factor that corrects the aggregate populationfor the undercounting of women and children. He does so byfitting the known data for males over the age of 15 to standard lifetables he deems representative of the population at the time andthen doubles the corrected male population to arrive at the totalpopulation. Once the adjustment factor is calculated, McCarthyapplies this to data from 1914 and then utilizes population growthrates to extrapolate back and forth in time. The graph displays hisadjustments for the Diyarbekir province.There are many issues with such a methodology. First andforemost, applying corrections based on the recorded population20 years prior is highly questionable and McCarthy fails to fullyappreciate the implications. The methodology is further hamperedby the existence of only one source for the reporting of populationby age groups.In the specific example of the Diyarbekir province, McCarthynotes that the growth in recorded population from 1892 to 1914 isunrealistically high. He speculates that the reason is due to improvedenumeration of the population. Yet, he still applies the same correctionfactor calculated from earlier data without consideration thatsome of the improved counting could have originated in the groupsthat the factor is meant to correct (i.e., women and children).In addition, as can be seen from the graph, McCarthy smootheda dip in the recorded male population aged 35–39. However, this isthe age group that would have been affected by the Russo-TurkishWar of 1877–78. Stable population theory must be utilized cau-Diyarbekir Province 1892/3 dataUndercounting of ChildrenRecorded FemalesUndercounting of WomenImpact of 1877/8 Russo-Turkish/WarAges Ages Ages Ages Ages Ages Ages Ages Ages Ages Ages Ages Ages Ages Ages Ages10–14 15–19 20–24 25–29 30–34 35–39 40–44 45–49 50–54 55–59 60–64 65–69 70–74 75–79 80–84 85–90Recorded MalesAdjusted MalesAges90–This page is sponsored by Deneb Karentz20| THE ARMENIAN WEEKLY | <strong>April</strong> <strong>2011</strong>

FOR THE RECORDtiously so as not to remove thevery real demographic impact ofhistorical events. The issuebecomes more acute when it isunderstood that the factor thusderived is applied unadjusted tothe 1914 population. In essence,the recorded males aged 35–39in 1914 are being adjusted by afactor derived from the populationof males who fought in the1877–78 war when quite reasonablythey should not have beenadjusted at all.While population by age isonly available in the 1892–93data, the breakdown by genderis available for other time periodsand the ratio of males tofemales varies by ethnicity andyear of enumeration. The adjustment,which McCarthy appliedto all ethnicities equally, shouldbe viewed with caution. In fact,while the data limits the abilityto reflect ethnic differences, it isa mistake to assume no such differencesexist.While the ratio of recorded males to females for Muslims inthe Diyarbekir province was traditionally around 1.20, by 1911the ratio had dropped to 1.04. Conversely, the ratio for <strong>Armenian</strong>swas traditionally around 1.05 but had jumped to over 1.17. Whatcan we make of this dramatic change and what are the implicationswhen estimating the <strong>Armenian</strong> population? The interpretationis complicated by the expectation that the ratio of <strong>Armenian</strong>men to women should have dropped dramatically following theHamidian Massacres of 1894–96, which targeted almost exclusivelymen. However, this could have partially been offset by theforced conversion of <strong>Armenian</strong> women to Islam. In addition, thereis the emigration of <strong>Armenian</strong> males to consider.Another way to state the problem is to refine McCarthy’smethodology for the differences in male to female ratios. Based onthe life table McCarthy employed, he arrived at a factor of 1.1313to adjust the male population for the undercounting of young boys.The overall factor, then, for any time period and ethnicity wouldequal (2 * 1.1313) / (1 + females / males). McCarthy’s resultingadjustment factor based on 1893 data and that ignores ethnicity is1.2142 (through an error in McCarthy’s calculations, he uses1.2172). If instead one were to use the 1911 data, the adjustmentfor Muslims would be 1.1525, while 1.2146 for <strong>Armenian</strong>s.There is the additional issue of the extraordinary growth inthe recorded Muslim population while not quite to the samePopulation by districtTotal <strong>Armenian</strong>s PatriarchatePopulation <strong>Armenian</strong>s / Total / OttomanDiyarbekir Province<strong>Armenian</strong> Patriarchate (1913–14) 105,528 146.3%1330 Nufus (1914) 602,170 72,124 12.0%1329 Ottoman document 522,171 64,535 12.4%1312 Salname (1890–91) 397,884 56,196 14.1%Census 1 (pre-1890) 369,030 50,804 13.8%Chermik, Palu, Siverek<strong>Armenian</strong> Patriarchate (1913–14) 37,446 310.4%1330 Nufus (1914) 120,224 12,064 10.0%1329 Ottoman document 115,346 11,912 10.3%1312 Salname (1890–91) 122,814 20,115 16.4%Census 1 (pre-1890) 112,494 20,663 18.4%Other areas<strong>Armenian</strong> Patriarchate (1913/–14) 68,082 113.4%1330 Nufus (1914) 481,946 60,060 12.5%1329 Ottoman document 406,826 52,623 12.9%1312 Salname (1890–91) 275,070 36,081 13.1%Census 1 (pre-1890) 256,536 30,141 11.7%extent in the <strong>Armenian</strong> population. McCarthy attributes this toimproved enumeration and assumes the improvement is equivalentfor all ethnicities. That was not the case and in particularthe areas with the greatest concentration of <strong>Armenian</strong>s exhibitedthe least amount of growth. Not surprisingly, these are alsothe areas with the greatest differences between the <strong>Armenian</strong>population indicated by the patriarchate with that of theOttoman records.As can be seen from the table above, prior to the HamidianMassacres <strong>Armenian</strong>s accounted for almost 20 percent of the populationin the regions of Chermik, Palu, and Siverek. On the eveof World War I, according to Ottoman records this proportion haddwindled to 10 percent. When compared to the <strong>Armenian</strong>Patriarchate figures, these three areas account for ~25K of the~33K difference, even though only one-third of the <strong>Armenian</strong>population resided in those districts.SUMMARYEven prior to the Hamidian Massacres, Ottoman records indicateda decline in the number of <strong>Armenian</strong>s within the Diyarbekirprovince. It was not until 1900 that the <strong>Armenian</strong> male populationrecovered, either due to improved enumeration or as part of thepost-massacre demographic rebirth.This page is sponsored by Emma Soghoian in memory of her husband, Galoost Soghoian<strong>April</strong> <strong>2011</strong> | THE ARMENIAN WEEKLY | 21

AghjayanThe central question is under what assumptions do we accountfor the difference between an <strong>Armenian</strong> population of 72,124 asstated within Ottoman records to the 105,528 stated by the<strong>Armenian</strong> Patriarchate?If we begin with the 1911 Ottoman document, which seemsto represent the population as of 1905–06, the <strong>Armenian</strong> malepopulation is stated as 34,645. The first adjustment is to accountfor the undercounting of male children. As we have alreadyseen, McCarthy assumed 1.1313 based on data from 1892. If wedo not adjust the male population aged 35–39, which assumesthe dip is due to higher deaths from the 1877–78 war, then theadjustment is 1.1215. The fundamental problem is that therecorded population is 80 percent Muslim and there is no way todiscern whether <strong>Armenian</strong> children were undercounted to agreater or lesser extent.In addition, the total population grew by ~26 percent between1892 and 1906. A more reasonable growth rate would have been10–11 percent. The additional growth has been assumed to comefrom better enumeration. So, one could assume that no adjustmentneed be made for the undercounting of children since improvementsin enumeration entirely came from those under the age of15. While that is probably not a reasonable assumption, it is a possibilitythat children were counted to a greater or lesser extent in1906 than in 1892.In addition, there is the matter of the reasonableness of the lifetable that McCarthy has chosen. It is beyond the scope of this articleto address this issue, but for these reasons I prefer a range ofassumptions. Here I will assume three different adjustments forthe undercounting of male children: 10 percent (low), 12.5 percent(mid), and 15 percent (high).Low Mid High1906 Recorded <strong>Armenian</strong> Males 34,645 34,645 34,6451906 Adjusted <strong>Armenian</strong> Males 38,110 38,976 39,842The Muslim population grew by ~14 percent between 1329Ottoman document and the 1330 Nufus (which is thought to representthe population as of 1914), while the <strong>Armenian</strong> populationgrew by ~12 percent. Again, this represents better enumerationplus normal population growth. Either the <strong>Armenian</strong> populationgrew at a slower pace or there were greater improvements in registeringMuslims than <strong>Armenian</strong>s. For this purpose, let’s assume10 percent, 12 percent, and 14 percent, respectively.Low Mid High1914 Adjusted <strong>Armenian</strong> Males 41,920 43,653 45,420Interestingly, this is about 6,000 less than what might beexpected based on the growth in the Muslim population. Basedon other estimates of the time, this would be an estimate for thenumber of <strong>Armenian</strong> deaths during the Hamidian Massacrescombined with emigration in the intervening years.As pointed out earlier, you cannot simply double the malepopulation to arrive at the total population, as <strong>Armenian</strong> malesexhibited deaths and emigration beyond those of females. In addition,conversion to Islam needs to be accounted for. I am going toassume a range of between 0 and 4,000 <strong>Armenian</strong> women convertedto Islam in the years between 1890 and 1914.Low Mid High1914 Adjusted <strong>Armenian</strong> 85,841 91,305 9 6 , 8 3 9Total PopulationThis represents a difference from the patriarchate figures of 9–23percent. From 1890 to 1914, the population of Diyarbekir displayedgrowth rates that indicate improved registration. Over that period,there was no indication that the trend had leveled or even slowed.Thus, omissions of men over the age of 15 may still have existed.In addition, there is ample evidence that even in developedcountries the undercounting of minorities is greater than the restof society. For instance, even in the 1990 United States census,African Americans are undercounted almost five times that ofwhites. Hispanics are undercounted to an even greater extent.Further, the omission rates for African Americans have been estimatedto be greater for males aged 15–40 than for ages 5–15.This is not to say that <strong>Armenian</strong>s within the Ottoman Empireand African Americans within the United States would exhibit thesame rates of omission in census enumerations, but it does indicatethat differences between ethnicities is a reasonable assumption.One area that should be looked to for evidence of undercountingof <strong>Armenian</strong>s, whether purposeful or not, is the town ofChungush. <strong>Armenian</strong> sources indicate a very large <strong>Armenian</strong> population,yet Ottoman records as late as 1900 indicate only one villagecontaining non-Muslims in the Chermik District whereChungush was located (as well as the towns of Adish and Chermikwhich also contained <strong>Armenian</strong>s). The Ottoman records indicatethe <strong>Armenian</strong> population dropped from almost 6,000 in this districtto less than 800. The population was well above 10,000 and closerto 15,000. This alone could explain much of the difference.The analysis above, to a large extent, assumed that the undercountingin the Ottoman registration system was equivalent for<strong>Armenian</strong>s and Muslims. That was most likely not the case. Buteven with that assumption, the Ottoman records indicate theimpact on the <strong>Armenian</strong> population of policies initiated by theOttoman government.Imperfect data is the norm in historical demography.However, even with the flaws in available information, much canbe learned from such analysis as that above. The goal is not toarrive at a definitive number of <strong>Armenian</strong>s, but more to understandthe issues that must be overcome to fully understand themagnitude of the crime that was committed. aThis page is sponsored by Jeanmarie Papelian22 | THE ARMENIAN WEEKLY | <strong>April</strong> <strong>2011</strong>