Untitled - Engineers Without Borders USA

Untitled - Engineers Without Borders USA

Untitled - Engineers Without Borders USA

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Acknowledgements<br />

The Legacy Foundation would like to thank the following<br />

persons and organizations for their important contributions<br />

to the lessons learned in the development and<br />

extension of briquette technology.<br />

Dr. Ben Bryant, Professor Emeritus, (retired) University<br />

of Washington Forest Products Laboratories, Seattle<br />

Washington who developed the first briquette press and<br />

continues to be a guide in the technology development.<br />

Malawi: Harry Chuma, Principal Secretary Ministry of<br />

Energy and Mines, Lilongwe Malawi; Wisdom Mulango<br />

Nkhomano Center for Development; Sue Clasby, Peace<br />

Corps Volunteer with the AIDS Orphans project Balaka;<br />

the women’s groups of Mchinji and Mangochi districts<br />

especially the senior trainers Stanford Noa and Frederick<br />

Banda; Anna Erdelmann and Esther Chirwa of the Urban<br />

Poverty Alleviation Project/GTZ; Sean Southey of UNDP;<br />

Marijke Mooij of a private Dutch consortia and Godfrey<br />

Sabiti, UNHCR.<br />

Kenya: Christopher, Elizabeth and Nicholas Wood,<br />

project designers, program managers and equipment<br />

suppliers; Mary and Francis Kavita, lead trainers; Charles<br />

Njiroge, Francis Oloo and the women of the Kangemi<br />

Women’s Empowerment Center; Stephen Gitonga,<br />

ITDG Kenya.<br />

Peru: Carlos Olivera, Pablo Arujo, Nestor Valesco Castilla,<br />

Bill Davis and John Wilcox of ADRA; Mario Carrion of<br />

Canel 9; the women’s groups in Mosocllacta, Q’quea and<br />

Chiaquilccasa communidades en la departamente del<br />

Cusco, Juan Ponce de Leon and Txema Torrebada; the<br />

faculty of the National University of San Antonia Abad del<br />

Cusco and Juan Ponce de Leon and Txema for translation<br />

assistance.<br />

Mali: Enterprise Works Worldwide staff; Youshaou Traore,<br />

translator; Adame Ba extension trainer; Abdullaye Dem<br />

technician and Affa Sammassekou, thresher device designer<br />

and manufacturer.<br />

THE LEGACY FOUNDATION 2003 — Fuel Briquettes: A Users Manual<br />

Haiti: Dr. Keith Flannagan of World Concern; Richard<br />

Ireland, Peace Corps Volunteer and extension trainer.<br />

Zimbabwe: Claudio Dembezeka of the Mukuvisi<br />

Woodlands Center Education; Emmanual Koro of the<br />

Africa Resources Trust (ART); Gus Le Breton, Southern<br />

Africa for Indigenous Resource Use (SAFIRE); Steve Murray<br />

of Action Magazine; Ramson Choto of the Ministry of<br />

Energy and Mines and the ZIMTRUST organisation.<br />

Mexico: Nancy and Robert Hall; Juan Pablo Tapia Cruz<br />

of DESMUNI; Porfirio and Xavier briquette technology<br />

technicians<br />

Uganda: Uganda Industrial Research Institute; Dr. Mike<br />

Foster and Charles Sembatya of Sasakawa Global 2000.<br />

Ashland Oregon: Dr. Owen McDougal - Southern<br />

Oregon University Chemistry professor and principal<br />

investigator on briquette technology applications.<br />

Other supporters of the briquette technology<br />

development include:<br />

Steve Troy of Sustainable Village; Claire and Jack Fincher/<br />

practitioners; Mike Stanley/ Media Development; Kirsten<br />

Paul/ Web site development; Jeff Stanley/ sound and<br />

video graphics; Peter Stanley/ extension training; <strong>USA</strong>ID;<br />

The Jane Marcher Foundation; UNDP; <strong>USA</strong>ID; ADRA; Plan<br />

International; GTZ and UNHCR; Special thanks to Michael<br />

Lee (idesigncom.com) for his graphics design expertise<br />

and patience in the production of this series of briquette<br />

manuals.

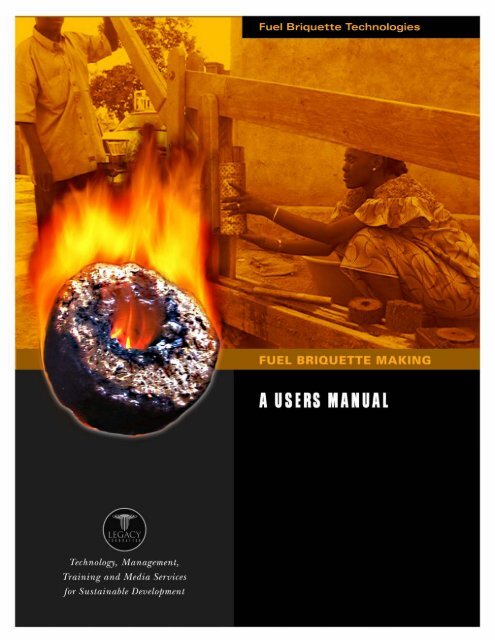

FUEL BRIQUETTES MAKING:<br />

A USERS MANUAL<br />

© 2003, The Legacy Foundation<br />

THE LEGACY FOUNDATION 2003 — Fuel Briquettes: A Users Manual

Table of Contents<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

The Art of Making Fuel Briquettes 2<br />

The Process of Making Fuel Briquettes 4<br />

Step 1. Organizing the Fuel Briquette Making Equipment 4<br />

The Fuel Briquette Press Kit 4<br />

Step 2. Material Collection 5<br />

Step 3. Material Processing: The Most Important Part 6<br />

Drying and Chopping the Materials 6<br />

Decomposing the Materials 8<br />

Creating Fuel Briquette Recipes 9<br />

Mixing/Blending the Materials after Decomposition.<br />

Testing the readiness of the decomposed/pounded<br />

9<br />

material for pressing 10<br />

Step 4. Pressing the Briquettes 12<br />

The Pressing Process in Detail 13<br />

Step 5. Drying and Storage 16<br />

Sample Basic Recipes 17<br />

Generic Recipe One: Scrap Paper Based Recipes 17<br />

Generic Recipe Two: Agro Residue Based Content 17<br />

Basic Burning Techniques and Fuel Briquette Usage 18<br />

Fuel Briquette Production by a Group 19<br />

Work organization for a group of six fuel briquette makers 19<br />

Conclusion 20<br />

THE LEGACY FOUNDATION 2003 — Fuel Briquettes: A Users Manual

INTRODUCTION<br />

Fuel Briquettes - made from everyday agricultural and commercial<br />

residues such as weeds, leaves, sawdust, rice husks, carton board and<br />

scrap paper – are a unique, yet well proven technology.<br />

In many parts of the world, people are making this new and modern<br />

fuel and saving time, saving energy, saving our environment and creating<br />

income. Fuel briquettes are unique because they provide a fuelwood<br />

alternative from resources that are right under your feet or in<br />

your wastebasket! Fuel briquettes can be made relatively quickly at a<br />

low cost to the manufacturer or consumer and can be adapted and<br />

applied in a wide variety of settings, making the resource appropriate,<br />

sustainable and renewable.<br />

The Legacy Foundation and its partners have tested the fuel briquettemaking<br />

process over ten years in a wide variety of environments and<br />

conditions – in urban and suburban and rural areas in Malawi, Haiti,<br />

Kenya, Zimbabwe, Nicaragua, Peru, Mali and the United States. The<br />

producers who have participated in fuel briquette training have<br />

become expert in the process and able to adapt their own conditions,<br />

materials and environment to the fuel briquette production process.<br />

This manual provides all that is required to make a fuel briquette press<br />

kit. Other manuals in our series include Fuel Briquette Press Kit: A<br />

Construction Manual - a step by step guide in making fuel briquettes,<br />

Fuel Briquettes: A Trainers Manual a guide to expand fuel briquette making<br />

into a community project and Fuel Briquettes: Theory and<br />

Applications From Around the World which includes a recipe book for<br />

the experienced fuel briquette maker to expand the variety and types<br />

of fuel briquettes made and their applications.<br />

THE LEGACY FOUNDATION 2003 — Fuel Briquettes: A Users Manual

The Art of Making Fuel<br />

Briquettes<br />

What are fuel briquettes? Fuel briquettes are a low<br />

cost, locally made fuel for cooking or heating that<br />

offer an alternative to the use of firewood. Fuel briquettes<br />

are made from grass leaves, straw or other<br />

agricultural waste products. The basic process that<br />

will be described in detail in this manual involves<br />

collecting the dry materials, pounding or grinding<br />

them to a certain consistency, mixing the materials<br />

with water, allowing the ‘mash’ to sit for a period of<br />

time, pressing the mash into a fuel briquette using a<br />

specially designed press, allowing the briquettes to<br />

dry and finally burning the fuel briquettes exactly as<br />

one would burn firewood.<br />

Varieties of Fuel Briquettes Around the World<br />

2 THE LEGACY FOUNDATION 2003 — Fuel Briquettes: A Users Manual<br />

Over the years of experience in fuel briquette making<br />

on Legacy Foundation sponsored projects, there<br />

have evolved about 100 different fuel briquette<br />

‘recipes’. Each offers a slightly different texture,<br />

aroma and benefit according to the need and<br />

application<br />

The variety of fuel briquette materials is as diverse as<br />

the communities where fuel briquettes can be<br />

made. Some producers use eucalyptus leaves (blue<br />

gum) to drive out mosquitoes with minimal smoke.<br />

Others use cedar needles to provide a nice aroma in<br />

their hearth while others make cedar fuel briquettes<br />

just to store in the closet to preserve clothes during<br />

the rainy season. Still others make fuel briquettes<br />

out of paper to provide an extended use for junk<br />

mail and other waste paper. Neem leaves offer the<br />

benefits of the Neem tree while the use of Water

Hyacinth controls this aquatic scourge weed.<br />

Addition of rice husks will lower the cost of the fuel<br />

briquette for short intensive burning applications.<br />

Charcoal fines and sawdust on the other hand greatly<br />

extend the heat intensity and duration for cooking<br />

meat. Mango leaves work better than guava and<br />

coconut better than banana fronds, and so on, as<br />

the experiences from the field in dozens of nations<br />

emerge. All types of fuel briquettes provide an<br />

income generating option for the local population.<br />

The heat values differ according to which type or<br />

types of materials are used. The coarse remains of<br />

maize milling, blended with aquatic weeds, such as<br />

the water hyacinth, provide a long slow burn of up<br />

to 1 to 1.5 hours for preparing beans. Sawdust and<br />

wastepaper blends work well for roasting or cooking<br />

meat with their hotter, but shorter burning time.<br />

One can as well use charcoal fines with more fibrous<br />

residues for high temperature cooking while cleaning<br />

up the environment.<br />

This manual will get you started on the process of<br />

fuel briquette making by providing the basic concepts<br />

of fuel briquette making, using the most readily<br />

available and easiest to use materials. We start<br />

with recipes that include waste paper or ‘Junk Mail’<br />

and ordinary grass, straw and leaves. In providing<br />

the basics, we hope to inspire you to experiment<br />

with your own available materials until the best<br />

material combinations are found to fit your own<br />

needs and requirements. Once you have acquired<br />

the basic skills through use of this Fuel Briquette<br />

Making; A Users Manual, a companion manual Fuel<br />

Briquettes: Theory and Applications from Around the<br />

World, provides extensive detail on a wide variety of<br />

actual blends in use and their applications. This<br />

advanced manual is available through the Legacy<br />

Foundation. The following provides the basics steps<br />

of fuel briquette making.<br />

There Are Five Steps In Making Fuel<br />

Briquettes:<br />

1. Organizing the Fuel Briquette Making<br />

Equipment<br />

2. Collecting the Materials<br />

3. Processing the Materials<br />

4. Pressing the Fuel Briquettes<br />

5. Drying and Storing the Fuel Briquettes<br />

THE LEGACY FOUNDATION 2003 — Fuel Briquettes: A Users Manual<br />

3

The Process of Making Fuel Briquettes<br />

Step 1. Organizing the Fuel Briquette<br />

Making Equipment<br />

Before we look at the fuel briquette making process, it is necessary to<br />

get all of the equipment together. This section describes all of the<br />

equipment required before the fuel briquette making can begin.<br />

The Fuel Briquette Press Kit<br />

A Fuel Briquette Press Kit consists of the following:<br />

■ A wooden hand press<br />

■ Two mold sets<br />

■ A plastic tarpaulin or black PVC sheet film of 5 meters by 2 meters in<br />

size, for drying and composting. Heavy-duty plastic sheet is preferred as<br />

shown below, right.<br />

■ 4 large metal pails or plastic buckets, as used for washing clothes, or<br />

kids. Two are shown below.<br />

■ Two - three large mortar and pestles, used in pounding maize; optional<br />

for higher production is a hand thresher or motor powered maize or<br />

hammer mill with a modified screen.<br />

■ Water: 200 - 250 liters is consumed gradually, throughout a full day's<br />

production effort. However to initiate production, another 200 liters<br />

should be available. Remember that this will be recycled throughout<br />

the day.<br />

Complete instructions on the construction of the Fuel Briquette Press<br />

Kit are provided in Legacy Foundation’s companion guide:<br />

Fuel Briquette Press Kit: A<br />

Construction Manual.<br />

4 THE LEGACY FOUNDATION 2003 — Fuel Briquettes: A Users Manual<br />

Wooden Hand Press<br />

Mold Sets — 2 each<br />

(from top left) center GS guide pipe, wood<br />

piston with cap plate at bottom end, divider<br />

washer and wood base plate with its centering<br />

ring and (bottom) white perforated PCV<br />

cylinder.<br />

Plastic Tarpaulin

Step 2. Material Collection<br />

A wide range of materials can be used for fuel briquette<br />

making. The types of raw materials used in<br />

fuel briquette making include: ground nut shells,<br />

rice husks, tree leaves (mango, eucalyptus, guava,<br />

cashew, blue gum, capale, sandrela, etc. etc.), grass,<br />

straw, maize covers, water algae and plants (including<br />

water hyacinth), banana leaves, flower petals,<br />

paper and on and on to any number of materials<br />

which might be available to the creative fuel briquette<br />

maker. In all cases it is important to remember<br />

that using natural residues, only dried brown<br />

leaves or grasses and the more dried straws are<br />

used. “Fresher” / greener material contains soil<br />

minerals which do not work in fuel briquette making<br />

because they do not burn well and cause smoke.<br />

Other ‘pre-processed materials’ like charcoal fines,<br />

sawdust, wood chips and waste paper can also be<br />

added. Paper readily breaks down and can serve as a<br />

starter fuel briquette material in that it binds other<br />

materials without the normal required processing<br />

time and effort of chopping and partial decomposition.<br />

If only agro residues are used, from 4 to 8 hectares<br />

of active farmland will usually be required for a fulltime<br />

press operation, reaching a market of up to<br />

500 persons per day. The amount of dry agro<br />

residues required however can decrease by as<br />

much as 40% when these other pre-processed<br />

materials are included in the mixture.<br />

Each fuel briquette maker will quickly find a unique<br />

recipe with its own burning characteristics from a<br />

given area for his/her own cooking needs. Let us<br />

know the recipes you discover so that others may<br />

continue to benefit from your experience!<br />

Overall, the list of materials is almost as long as the<br />

types of agricultural residue available to the fuel<br />

briquette makers. The only limit to the variety of fuel<br />

briquette making materials is thus far based on the<br />

limit of one’s imagination and skill in looking at their<br />

own environment. While thermal properties of the<br />

individual ingredients can provide a guide in some<br />

cases, they are, as yet, of little use in predicting heat<br />

efficiency and duration of the blended fuel briquette.<br />

These values depend far more on the skill in processing<br />

the material and ones choice of blends and the<br />

management of the production process itself. The<br />

most skilled producers are usually those with extensive<br />

practical knowledge of their own environment.<br />

The most important step to ensure efficient highquality<br />

production of fuel briquettes is the continuous<br />

supply and processing of selected agro-residue<br />

materials.<br />

Using the basic labor intensive technology described<br />

in this manual, 125 to 150 kgs. (dry weight) of<br />

processed material will be required by one fuel briquette-manufacturing<br />

group using one press kit, per<br />

each working day. The balance between agricultural<br />

residues and those already processed such as sawdust,<br />

charcoal fines, rice husks etc., determines the<br />

amount of each required but the total weight per<br />

day consumed will still be the same.<br />

Grass / straw<br />

Maize leaves<br />

mill waste<br />

Misc. leaves<br />

Paper & cardboard<br />

Sawdust<br />

Resource collection for a community production group in Mchinji<br />

Malawi, Central Africa.<br />

Some recommended ways to supply the fuel briquette<br />

production with materials include:<br />

■ Community participation, where all members of<br />

the village supply bags of raw materials and are<br />

compensated with a proportional amount of fuel<br />

briquettes in return.<br />

■ Participation by school children who bring a<br />

small bundle of raw materials to school each<br />

morning and produce their family’s weekly fuel<br />

supply after school.<br />

■ Individuals contracted to provide bags of raw<br />

materials to a production site and in return receive<br />

an appropriate compensation for their work.<br />

THE LEGACY FOUNDATION 2003 — Fuel Briquettes: A Users Manual<br />

5

6<br />

This service can also be provided by local<br />

posho/Maize/flour millers at the equivalent of<br />

their normal operating charges per minute or<br />

hour. (Unless they are using their mill for animal<br />

feed, they will tend to do the resource milling for<br />

fuel briquettes only at the end of the day so they<br />

can clean the mill for the next morning’s flour<br />

production).<br />

Every community will develop its own optimum<br />

collection approach. No matter how the materials<br />

are collected, it is important to note that they are<br />

going to accumulate into an unsightly and possibly<br />

unsanitary mess, unless provision is made for their<br />

processing.<br />

Step 3. Material Processing: The<br />

Most Important Part<br />

Introduction<br />

Fuel briquette making theory is based on the<br />

tendency of natural fibers to interlock when<br />

combined with other by-products of agro processing.<br />

The objective is to create a material that will act<br />

like VELCRO without the introduction of any<br />

glue, resin or other artificial binders.<br />

The processing of fuel briquette making materials is<br />

the key step in fuel briquette work. It involves chopping,<br />

wetting and ‘resting’ of the materials until the<br />

materials are ready to be pressed. The principle on<br />

which the fuel briquettes are bound together is<br />

basically a mechanical process in which naturally<br />

occurring residues are first chopped, then softened<br />

through partial decomposition. They are then<br />

blended with other agro residues or pre-processed<br />

residues such as sawdust, charcoal fines, and or rice<br />

husks, in a simple water slurry. This blending<br />

process causes the fibers to be randomly redistributed<br />

throughout the mass, and to entangle and<br />

interlock into a solid mass as the mass is compressed<br />

and dewatered. There is no chemical binder<br />

used in this fuel briquette making process.<br />

THE LEGACY FOUNDATION 2003 — Fuel Briquettes: A Users Manual<br />

Though this manual will provide the fuel briquette maker<br />

with the basic steps in the process, it must be emphasized<br />

that the fuel briquette making process requires practice,<br />

practice, practice and testing, testing, testing until the fuel<br />

briquette maker gets the ‘feel’ for the materials and the<br />

best fuel briquette making composition and combination.<br />

The manual can describe the process, the fuel briquette<br />

maker will fully understand the process only through production.<br />

As one becomes more experienced in the fuel briquette<br />

making process s/he will learn that applying time and<br />

water to decay agro residues at a controlled rate is<br />

more of an acquired art than a textbook learned skill.<br />

Drying and Chopping the Materials<br />

The process of material preparation (drying and chopping)<br />

may involve hand pounding or, manually driven<br />

threshing/chopping technologies, or machines process-<br />

ing depending on the economics and resources of the<br />

site. Whether a hand or mechanized process is used to<br />

prepare the materials, it has to pass the “squeeze” test<br />

noted below:<br />

The first step in preparing materials is to dry them and<br />

chop them. Several methods can be used for this<br />

process:<br />

1. The basic method is using a mortar and pestle. The<br />

dried agricultural residues are added in small batches to<br />

the mortar and pestle (see above) and pounded until<br />

they are the size of ‘corn flakes’ or the size of an<br />

adult’s ‘thumbnail’.

With the hand process, one would use a combination<br />

of pounding in a mortar and pestle followed by<br />

partial decomposition and blending again in the<br />

same mortar and pestle. The mortar and pestle provides<br />

the best texture for fuel briquette material;<br />

however, it is an extremely labor intensive process.<br />

A production group can find itself using up to 70%<br />

its production labor using a mortar and pestle. For<br />

this reason we recommend the use of a mortar and<br />

pestle only for training and entry level production<br />

or in situations where there is little capital for equipment<br />

investment and a relative abundance of<br />

unskilled and unemployed labor.<br />

2. Another method would be to use a variety of<br />

hand operated threshing or field-chopping technologies<br />

that break up the materials into the optimum<br />

size/shape far faster than hand pounding.<br />

These are commonly available in agriculture<br />

research institutes and development projects. With<br />

the manually operated thresher chopper equipment,<br />

the processing can be greatly accelerated<br />

because material size and shape is altered to greatly<br />

accelerate decomposition and or softening. Legacy<br />

Foundation has developed a specialized hand<br />

Legacy Foundation's hand- operated thresher, masher chopper: Uganda<br />

thresher for this purpose. It can provide chopped<br />

residues sufficient for two press groups per day<br />

under most conditions. Information on how to<br />

order this hand thresher can be found on the<br />

Legacy Foundation web site: www.legacyfound.org<br />

3. In the district centers and the more urban areas<br />

of developing nations, mechanized technologies<br />

may be a wiser choice for chopping. The mechanized<br />

process involves a chipper, lawn shredder or a<br />

lawnmower with a mulcher attachment, or a common<br />

hammer mill commonly known as a Maize/<br />

Posho/Chigayo/Molino. The chipper or shredder or<br />

hammer mill needs to be fitted with a screen/sieve<br />

of a 5/8” to 3/4” (15 to 20mm) diameter hole size.<br />

These machines can greatly assist the process of<br />

chopping the materials and free up much labor for<br />

production. A six to eght Hp (~4 to 6 Kw) hammer<br />

mill can process the residues needed for up to six<br />

press groups.<br />

5 Kilowatt Hammer-mill:<br />

Mosocllacta, Cusco, Peru<br />

5 Kilowatt Hammer-mill:<br />

Bamaco, Mali<br />

THE LEGACY FOUNDATION 2003 — Fuel Briquettes: A Users Manual<br />

7

Decomposing the Materials<br />

Decomposing most agricultural residue material follows<br />

the usual agricultural composting process,<br />

except that earth is not added. In preparing agro<br />

residue material for fuel briquette making we are<br />

only interested in separating or weakening the bond<br />

between the pithy material and the fibers. We do<br />

not want to let the decomposition proceed to the<br />

point of breaking down all material and creating<br />

topsoil.<br />

Depending upon how much time would be<br />

required for their decomposition, 6 to 14 rows of<br />

materials wrapped in plastic as seen below, each up<br />

to 50cm height x 1 meter width x 5 meters in<br />

length, can be present at the a fully operational fuel<br />

briquette production site at any one time.<br />

Left: Plastic tarp folded over chopped residues<br />

Each such pile would be in progressively further stages<br />

of decomposition, such that each day a new pile is<br />

added and one is removed for use in production.<br />

Note:<br />

The use of pre processed residues such as sawdust,<br />

charcoal fines or rice husks can reduce the<br />

above suggested agro-residue processing volume<br />

by 40% as these pre-processed wastes are<br />

simply blended into the agro-residues when the<br />

latter are ready.<br />

8 THE LEGACY FOUNDATION 2003 —fuel briquettes —A Users Manual<br />

As with composting, natural material decomposes<br />

quickly when you keep it covered, moist and out of<br />

the wind. Some material will require only a few<br />

days; others will require several weeks depending<br />

upon the local climate and the material used. The<br />

materials should be left to decompose until they<br />

become soggy and warm to the touch. The pestle<br />

or a rake may be used for further breaking up and<br />

mixing the materials to assure uniformity in the<br />

stage of decomposition. Eventually this pile of<br />

residue begins to heat up through its own internal<br />

“decay” process.<br />

Note:<br />

The fibers should not be left to decompose or<br />

burn up beyond this point. If left too long, they<br />

will begin to break down like compost, generating<br />

basically, a rich humus, which does not, to<br />

our experience, burn very well.<br />

If discarded oil drums or discarded water tanks are<br />

available, they can be used to provide a continuous<br />

feed composter. Bolt or weld the tanks together to<br />

form an open vertical stack 1.2 to 2 meters height<br />

and elevate them above the ground. Make a removable<br />

opening at the bottom through which you can<br />

rake out the “ripe” material (a sliding gate is the<br />

best), while fresh material is added to the top. The<br />

rate of feeding and removal depends highly upon<br />

local climate and material conditions.<br />

The time required for decomposition depends upon<br />

the season and the material type. Generally allow<br />

two weeks in a hot/dry season and up to six weeks<br />

in a cold season, with times for decomposition during<br />

the rainy seasons falling somewhere in between.<br />

Where you cannot yet use such materials immediately,<br />

they can be raked out into an open flat pile with<br />

no cover to stop or at least dramatically slow down<br />

further decomposition. Once interrupted and left in<br />

dry, open, aerobic conditions, the prepared material<br />

can be stored until it is needed. Leaving it in dark<br />

humid conditions however, will further soften and<br />

destroy fiber strength resulting in a useless fuel bri-

quette making material. It will in other words fail the<br />

"ooze" test (see the section below).<br />

Mixing/Blending The Materials<br />

After Decomposition.<br />

Once the materials have been suitably decomposed<br />

they are ready for blending. They are diluted in<br />

water and mixed into a coarse paste or sludge consistency<br />

so that they can be easily added to the<br />

mold. This mixing also ensures that the fibers are<br />

randomly distributed throughout the mass around<br />

them.<br />

Several methods can be used to ensure that this<br />

sludgy mass of agricultural compost is actually ready<br />

for molding — either on its own or as a base material<br />

for other more granular materials (sawdust, rice<br />

husks, charcoal fines etc.).<br />

The average farmer we have trained picks up the<br />

idea in less than two days. It is often a more daunting<br />

task for those who are perhaps more "educated",<br />

have lost their sense of a feel for the natural environment.<br />

Mixing & blending resources during training in Cusco, Peru.<br />

Note:<br />

The choice of which process to apply is far less<br />

difficult if you understand the theory, namely<br />

that the material has to break down sufficiently,<br />

to expose fibers and pith, so that they will interlock<br />

when saturated with water and then compressed<br />

and de-watered.<br />

Creating Fuel Briquette Recipes<br />

With the individual composted materials processed<br />

and ready, it remains to determine the right proportions<br />

of adding other materials like charcoal fines,<br />

paper, rice husks, etc., each for the desired heating<br />

effect. Fuel briquettes can be made to provide a hot<br />

and quick burn (with rice husks, sawdust and waste<br />

paper) or a long and slow burn (using coarse maize<br />

flour from the maize mill, water hyacinth and other<br />

very well decomposed vegetation).<br />

The mixtures can be used for industrial applications<br />

and brick making (using Tobacco bale paper and<br />

assorted leaves), to general cooking (using leaves<br />

field grasses/straws and waste paper), to other specialized<br />

applications: For example, fuel briquettes<br />

made with up to 25% cedar wood chips provide a<br />

very pleasant aroma for space heating. Fuel briquettes<br />

made with up to 75% eucalyptus leaves<br />

have been reported to be effective in repelling some<br />

insects, including mosquitoes. This is accomplished<br />

without the acrid smoke one experiences in burning<br />

a pile of leaves but, rather, through preheating and<br />

emission of their natural aroma before actual combustion<br />

in the fireplace.<br />

The degree to which these fibrous and pithy materials<br />

can be mixed will vary according to the quality,<br />

maturity and specific type of each material. The<br />

Legacy Foundation’s, Fuel Briquettes: Theory and<br />

Applications from Around the World, describes some<br />

of the variations that have been developed through<br />

various fuel briquette making projects. Each area and<br />

each season produces an almost infinite variety of<br />

resources for fuel briquette making and each new<br />

THE LEGACY FOUNDATION 2003 — Fuel Briquettes: A Users Manual<br />

9

variation has its own ideal proportions. What we<br />

repeatedly have discovered is that the village<br />

trainees exhibit a detailed knowledge not only of<br />

their own local resources but how to utilize them in<br />

fuel briquette making. Every fuel briquette maker<br />

should be encouraged to develop their own recipes<br />

from the materials that are available to them. The<br />

key always is to ensure that the material mixture<br />

passes the test of readiness for pressing.<br />

Testing the readiness of the<br />

decomposed/pounded material<br />

for pressing<br />

These simple tests require one’s own hand, nothing<br />

more. There are numerous quantitative analogues<br />

for describing the characteristics these tests, such as<br />

porosity, permeability, plasticity/elasticity, shear and<br />

tensile strength, and someone will surely get a very<br />

useful master’s degree from a full analysis of the<br />

hydraulic and engineering characteristics of the<br />

material. For now however, our interests are more<br />

toward reaching large numbers of the globe’s citizens<br />

whose strengths lie more in their keen perception<br />

of their own natural resources and local historical<br />

knowledge, than in verbal representation per se.<br />

We therefore communicate the characteristics of the<br />

material through development of a certain “feel” of<br />

it through three simple field tests, as they provide<br />

the most replicable, practical and easily conveyed<br />

measurement tool for material assessment amongst<br />

the majority of the producers and users of these fuel<br />

briquettes.<br />

All three tests involve scooping a representative<br />

handful of well-mixed material out of a slurry of the<br />

proposed mixtures and squeezing it by making a<br />

tight fist.<br />

■ The "ooze" test: if the material oozes through<br />

your fingers on squeezing your fist, it is too<br />

”ripe”. The fibers are either insufficient in number<br />

or those which are present have been<br />

destroyed by too much decomposition. Add<br />

more fibers and test again. Oozing is equivalent<br />

to over cooking the material: indeed it means<br />

that you are well on the way to making topsoil:<br />

however topsoil does not usually burn very well.<br />

10 THE LEGACY FOUNDATION 2003 — Fuel Briquettes: A Users Manual<br />

■ The "spring back" test: if you notice that on<br />

opening your fist after squeezing, the material<br />

expands by more than say 10% of its original<br />

diameter or length, then the material requires<br />

further decomposition or pounding, or re-mixing<br />

with better material. Generally however, it is better<br />

to prepare the material correctly in the first<br />

place, rather than trying to cover up the mistake<br />

by adding more material. The material must<br />

retain imprint of closed fist, as above, neither<br />

oozing through the fingers nor feeling “spongy”<br />

to the touch.<br />

Spring back test material must retain imprint of closed fist neither<br />

oozing through the fingers nor feeling “spongy” to the touch.<br />

■ The "shake" test: a good fuel briquette material<br />

will not fall apart when held over the upper 1/2<br />

portion and shaken vertically a few times as one<br />

would move a salt shaker. Samples that fall apart<br />

during such shaking will require more fibrous<br />

material (chopped grasses/straws, stems, fibrous<br />

leaves, choir fiber etc.<br />

Shake test for blended agro- residues, prior to their use in briquetting

The process is like “home” cooking with pinches of<br />

ingredients here and there until you get the right<br />

consistency for a fuel briquette that will not be<br />

spongy nor fall apart. You will quickly discover that<br />

the mixtures vary according to not only the type of<br />

materials used but the maturity or readiness of these<br />

materials to dis-aggregate and re-bond in a water<br />

slurry.<br />

NOTE: While the above tests apply to agro residues,<br />

other agro-processed materials such as charcoal<br />

fines, sawdust and rice husks act primarily as fillers. if<br />

too much filler is added, the mixture will not conform<br />

to the above guidelines at all and the fuel briquette<br />

will not ‘hold together. For example, rarely<br />

can one add more than 50% sawdust, by volume, to<br />

waste paper and still have the mixture pass the three<br />

tests above. The practical maximum proportion of<br />

sawdust to agro-residues (by dry weight) for example,<br />

should be about 35%.<br />

Users Notes:<br />

THE LEGACY FOUNDATION 2003 — Fuel Briquettes: A Users Manual<br />

11

Step 4. Pressing the Briquettes<br />

The heart of the operation is pressing the prepared<br />

materials into burnable fuel briquettes.<br />

Hand Press Kit in Uganda, with molds, basin, sawdust and misc.<br />

leaves fuel briquettes.<br />

Each batch of material prepared for fuel briquette<br />

production will most likely be different due to the<br />

normal variability of the material and natural variations<br />

in the stage of decomposition. We have provided<br />

several existing recipes in the latter section of<br />

this manual to get you started, but you will quickly<br />

discover that it much depends upon local conditions<br />

in your particular area--and upon your own skill as<br />

the "cook". Therefore, if possible, it is helpful if the<br />

user obtains initial advice from experienced fuel briquette<br />

makers.<br />

Once the selection of mixtures is determined and<br />

the material has been prepared, the actual production<br />

of fuel briquettes is a simple labor-intensive<br />

process.<br />

The fuel briquette press shown above is rugged,<br />

reliable and in use in a wide variety of cultures and<br />

climatic conditions.<br />

This model of the hand press is designed for use in<br />

a production team of four to eight persons. A team<br />

of six persons, which plans and manages a steady<br />

supply of processed materials, will be able to produce<br />

750-1000 fuel briquettes per 8 hr. day (includ-<br />

12 THE LEGACY FOUNDATION 2003 — Fuel Briquettes: A Users Manual<br />

ing the materials processing). This is sufficient to<br />

meet the fuelwood demands of 75 to 90 families<br />

per day. <strong>Without</strong> good management and advance<br />

planning for materials, the process can slow to a<br />

frustrating one third of this output with the same<br />

labor input! Enough cannot be said about the need<br />

for advance planning of materials.<br />

Theoretically, one could simply use their hands to<br />

make fuel briquettes. The problem is that for some<br />

materials, there is need for higher pressure than the<br />

hands can exert. As well, in all fuel briquettes there<br />

needs to be some uniformity of size and appearance<br />

for marketing purposes: one's hands rarely provide<br />

such a uniform shape.<br />

Another reason for using the press to make fuel briquettes,<br />

rather than ones hands, is that we desire a<br />

uniform hole in the center to optimize the drying<br />

and the burning effect. Fuel briquettes made without<br />

a center hole take twice as long to dry. A solid<br />

cake will actually offer less effective heat than the<br />

hollow shape because the center hole functions like<br />

a combined chimney and insulated combusiton<br />

chamber. The chimney creates a cleaner and more<br />

efficient burn and makes ignition far more rapid.<br />

Center hole generates considerable heat in most cooking and heating<br />

conditions. This blend from Mali uses field straw, rice husks and<br />

waste carton board. It is burning in a simple three stone fireplace.

The Pressing Process in Detail<br />

The layout of the press and the briquette process is as follows:<br />

A training group in Chaquilccasa, Cusco Department, Peru<br />

side view (press elongated for illustrative purposes)<br />

THE LEGACY FOUNDATION 2003 — Fuel Briquettes: A Users Manual<br />

13

1. The first step in fuel briquette making is to mix<br />

the materials: The materials are mixed in a container<br />

or 1/3 of oil drum (~ 75 liters volume) and<br />

then saturated with water to the consistency of a<br />

soup or thick porridge.<br />

2. Set the cylinder atop the base plate of the mold,<br />

set the center pipe into the cylinder seating it in<br />

the center guide hold of the base plate. The<br />

"slop" mix is then scooped and poured into the<br />

cylinder as shown in Peru (below). Depending on<br />

the kind of material and the desired size of the<br />

fuel briquette, two to three scoopfuls of material<br />

are added to fill the mold 2/3rds to 3/4ths full. If<br />

desired a divider washer can be slid down over<br />

the center pipe at this point and a similar portion<br />

of material is then again poured into the<br />

mold.<br />

3. Once the mold set is filled to the top, the piston<br />

is inserted over the center pipe and pressed<br />

down by hand to rid the mold of excess water<br />

and loose air cavities as shown in Peru (above<br />

top). Depending upon the material being used<br />

and the size desired in the resulting fuel briquettes,<br />

the piston may need to be removed and<br />

14 THE LEGACY FOUNDATION 2003 — Fuel Briquettes: A Users Manual<br />

more material added. In either event, the piston<br />

should rest not less than 1” (2.5 cm) inside the<br />

cylinder before actual pressing. The resulting<br />

assembly is called a charged mold and is ready<br />

for pressing.<br />

4. Lift the handle of the press to its maximum<br />

height. Place the charged mold set - the filled<br />

plastic pipe, the base plate, the center guide<br />

pipe and the piston as one unit, on the bottom<br />

beam with piston aligned vertically beneath the<br />

top beam. Slide the assembled mold set back as<br />

far as it can go toward the rear legs (opposite<br />

end to the handle-end legs) while just touching<br />

the top beam. Making sure that the piston and<br />

cylinder remain in vertical alignment and that<br />

they remain on center between the top and bottom<br />

beams. The handle is then lowered in one<br />

continuous motion, until it can go no further<br />

(below): the operator should not have to jump<br />

on it, nor should it require more than one person<br />

to operate. Steady downward pressure has<br />

the effect of forcing remaining “free” water out

of the mold while allowing the randomly aligned<br />

fibers to interlock, forming a strong tight mass<br />

when the material dries out.<br />

Once the handle is all the way down, lift it again<br />

to its maximum extent and shift the mold set,<br />

again, as far to the rear as possible. Repeat the<br />

steady downward motion of the handle until it<br />

can go no further.<br />

Depending upon the type of material and size of<br />

the charge, you may need to repeat this step a<br />

third time to compress the cake as much as possible<br />

as shown in the pictures (below) from Peru.<br />

5. Ejecting the fuel briquette<br />

Lift the handle all the way to the top as shown<br />

below in Mali.<br />

Remove the base plate from plastic pipe and<br />

piston and shift the latter assembly over rest the<br />

cylinder on the Ejection Lip located inside the<br />

front legs of the press as shown above. The ejection<br />

lip is a small piece of angle iron or ribbed<br />

metal strip located halfway up the front legs.<br />

Press the handle downward gently as shown<br />

(above) in Peru. As the piston now travels further<br />

downward, unimpeded by the base plate,the<br />

fuel briquettes are forced out the base of the<br />

cylinder. You should have your hands ready to<br />

catch them to avoid damaging them as they fall<br />

out.<br />

THE LEGACY FOUNDATION 2003 — Fuel Briquettes: A Users Manual<br />

15

6. The center pipe is removed from the emerged<br />

fuel briquette(s) and PRESTO, you have your first<br />

fuel briquette(s) as shown below in Peru and<br />

Mali.<br />

7. The mold assembly is then re-assembled and<br />

filled with material, for another cycle.<br />

Step 5. Drying and Storage<br />

The fuel briquette should be carefully moved aside<br />

to dry with minimum handling, where it can be<br />

assured of an even air flow, protected from rain, but<br />

in open windy areas as much as possible.<br />

16 THE LEGACY FOUNDATION 2003 — Fuel Briquettes: A Users Manual<br />

Fuel briquettes are best dried when they are positioned<br />

to let air flow evenly across their whole surface.<br />

Where you are faced with only a flat unventilated<br />

surface, set the fuel briquettes down on their<br />

rounded side, not on their flat ends.<br />

Fuel briquettes generally take three to six days to dry<br />

in direct sunlight and up to eight days in cloudy<br />

conditions. Note that if the starchy material, left<br />

over from maize milling, or other impervious material<br />

is used in the mixture, drying can require up to<br />

twice this amount of time again.<br />

While drying in the sun is ideal, fuel briquettes can<br />

be dried under a well-ventilated roof out of the sun,<br />

as long as the above guidelines are adhered to.<br />

One can use an elevated bed of small thin reeds or<br />

sticks, corrugated metal sheeting (a corrugated<br />

metal roof top works very well) wire mesh, or other<br />

material to support the fuel briquettes as long as it<br />

promotes airflow all round the fuel briquette in an<br />

even fashion.<br />

In some areas, briquettes make wonderful food for<br />

ants, termites, etc. In this case it is necessary to use<br />

some form of barrier to protect the briquettes.<br />

The same black plastic sheeting used during materials<br />

preparation works well. In colder climates, some<br />

are using basic solar dryers made of wood poles and<br />

UV-sensitized, clear plastic sheeting to dry the<br />

briquettes.

Sample Basic Recipes<br />

There are two generic recipes or blends for fuel<br />

briquette making.<br />

‘Paper based’ blends provide one alternative and<br />

“Agro residue based’ blends provide another. The<br />

theory of binding is the same and almost any combination<br />

of the two is possible, but the process of<br />

preparing the material is a bit different.<br />

Described below are the two distinct methods.<br />

These recipes assume use of only basic equipment.<br />

The use of hand operated or mechanized equipment<br />

will greatly reduce the labor involved but the principles<br />

for good fuel briquette making remain the<br />

same.<br />

Generic Recipe One:<br />

Scrap Paper Based Recipes<br />

This recipe may or may not include agro residues<br />

1. Soak bucket of scrap paper in an ordinary pail of<br />

water for two days or so, until the paper can be<br />

readily torn into pieces about 1” in diameter.<br />

2. Collect four pails of dried grass/straws/leaves.<br />

If necessary, lay them out to dry in the sun until<br />

they become crispy. The required time can very<br />

widely depending on the temperature and<br />

humidity at the location.<br />

3. Pound the soaked paper adding water as necessary<br />

until the fibers are soft and the mass sticks<br />

together like crude paper mache or bread dough.<br />

4. Pound the dry leaves in the mortar where upon<br />

they should break up readily into something the<br />

size of ‘corn flakes’. Some break up more easily<br />

when wet, others when dry.<br />

5. Mix the broken leaves by the handful with the<br />

paper in a bucket or pail. Add water as necessary<br />

to give the mixture the consistency of a “slop”<br />

for want of a better word. This may require up to<br />

80% of the total volume being water. By volume<br />

you would want about 25% to 40% paper and<br />

from 75% down to 60% leaves.<br />

6. Follow the instructions in Step 4 (above): Pressing<br />

a Fuel briquette.<br />

The use of Scrap Paper makes the process relatively<br />

easy because you do not have to rely on decomposition<br />

of the agro residues to do the binding. That is<br />

accomplished by the paper which breaks apart easily<br />

and rapidly. You will however be restricted to the<br />

location where scrap paper is readily available. You<br />

will also be limited as to the kind of cooking or<br />

heating aroma you can produce.<br />

Generic Recipe Two:<br />

Agro Residue Based Content<br />

including miscellaneous leaves grasses<br />

and straws, stems fronds, etc. without<br />

any paper<br />

1. First pound the dry brown and somewhat brittle<br />

leaves grasses, straws, etc., into cornflake<br />

/thumbnail-sized pieces in the mortar and pestle.<br />

2. Soak the pounded leaves grasses and straws etc.,<br />

then spread them out under dark plastic tarpaulin<br />

or heavy plastic sheeting which is placed in<br />

the sunlight. Once the residues are added, fold<br />

over the sheet to make long rows, which are<br />

protected from the sun and wind. Add water<br />

every few days as necessary to keep the mass<br />

humid (but not soaked) to speed up decomposition.<br />

Mixing the grasses with leaves, particularly<br />

more resistant leaves, is reported by some to also<br />

accelerate decomposition.<br />

3. Keep a daily eye on the mixture to note when it<br />

begins to soften and heat up. This can require<br />

from one week to four weeks or more, depending<br />

on material type and climate. As with the<br />

decomposition process, this may not occur uniformly<br />

throughout the mass. It might be necessary<br />

to turn the row over to accomplish uniform<br />

decomposition. Do this by opening up the plastic<br />

sheet and lifting it in a jerking motion all<br />

along one side. Repeat with the same motion on<br />

the other side and re-cover.<br />

Some prefer to make the batches in smaller<br />

amounts, using plastic sacks, homemade or purchased,<br />

discarded water tanks or simply open<br />

pits for containing the material. The same principles<br />

for decomposing and testing the mass apply<br />

for any configuration selected<br />

THE LEGACY FOUNDATION 2003 — Fuel Briquettes: A Users Manual<br />

17

4. When the mass becomes sludgy and warm, it is<br />

time to stop the decomposition process by<br />

opening the plastic and exposing the mass to<br />

the wind and sunlight. If it shows signs of actually<br />

burning it is time to stop decomposition<br />

immediately because the fibers which are needed<br />

for binding the material together are being<br />

disintegrated. Drying the mass out in open sunlight<br />

with plenty of airflow, will preserve it for<br />

later use, or if you prefer, you can use it directly.<br />

5. The art of good agro residue-based fuel briquette<br />

making is largely determined by the art of<br />

material processing. Knowing when to interrupt<br />

decomposition is the key part of material processing.<br />

When you are ready to actually press<br />

the fuel briquette you proceed with step 4<br />

above, paying special attention to the ‘squeeze’<br />

and ‘ooze’ and ‘spring back’ tests.<br />

6. While the use of only agro residues is more challenging,<br />

it is far more rewarding in terms to the<br />

increased varieties of aromas and cooking and<br />

heating applications open to fuel briquette user.<br />

It will also enable you to apply the skills in<br />

almost any environment, quite independent of<br />

the more urban environments upon which the<br />

paper based recipes depend.<br />

Whether paper based of agro-residue based fuel<br />

briquettes are made, the addition of pre-processed<br />

commercial residues can reduce by up to one-half<br />

the total volume of agro residue and/or paper material<br />

required. Such wastes as sawdust wood chips,<br />

rice husks, coffee hulls, coir dust or charcoal fines<br />

are added to either of the above preparations with<br />

the caution that once mixed into either of the<br />

above bases, the blend should still pass the squeeze<br />

test. Generally one cannot add more than 50% of<br />

these materials, (often not more than 40% of these<br />

“commercially processed” granular materials), without<br />

causing the blend to become too spongy and<br />

fall apart in the testing process<br />

18 THE LEGACY FOUNDATION 2003 — Fuel Briquettes: A Users Manual<br />

Basic Burning Techniques and<br />

Fuel Briquette Usage<br />

There are three burning techniques to<br />

remember<br />

Air Flow<br />

Good airflow is critical to a good burn with these<br />

fuel briquettes. It is particularly important to allow<br />

good air access to the bottom of the fuel briquette.<br />

Failure to do so will result in a smoky burn.<br />

Ash Removal<br />

Fuel briquettes produce ash and while this is handy<br />

for fertilizer or soap making, it can clog the airflow<br />

unless removed during each burn.<br />

Position<br />

For any one type of fuel briquette, you will get a<br />

longer and more efficient flame if you keep the fuel<br />

briquette upright, letting it burn primarily through<br />

the center hole. This is due to the chimney effect of<br />

the hole, which raised the combustion temperature<br />

and makes the burn far more efficient. If you desire<br />

only quick and widely diffused heat, then break the<br />

fuel briquette into three or four pieces by stomping<br />

on its round side with your foot. For any given type<br />

of fuel briquette, this will ensure a faster start up but<br />

with a quicker burn. Even with this method, try to<br />

ensure that the pieces are raised slightly off the<br />

ground to let air underneath.<br />

Cooking<br />

Fuel briquettes can be burned using a three stone<br />

open fire, a wood stove, a small metal cooking<br />

stove, a barbecue/brai or in any other stove normally<br />

used for wood or charcoal cooking.<br />

Other Potential Uses<br />

With the right recipe fuel briquettes can be used as a<br />

mosquito repellant, a room freshener, a cloth fumigant<br />

or a source of fuel for brick burning!<br />

The Legacy Foundation Fuel Briquettes: Theory and<br />

Applications from Around the World provides detailed<br />

recipes and fuel briquette usage options.

Fuel Briquette Production<br />

by a Group<br />

The press lends itself to operation with six to eight<br />

persons community income producing group. A<br />

group, with optimum material availability and in full<br />

operation can produce 750 to 1000 fuel briquettes<br />

in one day.<br />

Work organization for a group of<br />

six fuel briquette makers<br />

For a community project and the production of 750-<br />

1000 fuel briquettes a day, six workers are required<br />

for full utilization of one press (the number should<br />

not be less than 4 nor larger than 8).<br />

■ One person is the handle operator.<br />

■ Two persons are the mold chargers and actual<br />

fuel briquette molders (these persons work on<br />

opposite sides of the press, such that when one is<br />

filling their mold, the other is compressing and<br />

ejecting the fuel briquette from theirs). In this<br />

way, the press is kept in constant motion.<br />

■ Two persons are pounders and mixers of<br />

materials and,<br />

■ One person who gathers material and hauls completed<br />

fuel briquettes away to the drying site.<br />

The work is rotated amongst the team, mainly to<br />

relieve the pounders and mixers who have the<br />

most demanding task.<br />

The Legacy Foundation Fuel Briquettes: A Trainers<br />

Manual, provides a detailed plan for establishing and<br />

maintaining a fully operational briquette-making<br />

business.<br />

Users Notes:<br />

THE LEGACY FOUNDATION 2003 — Fuel Briquettes: A Users Manual<br />

19

20 THE LEGACY FOUNDATION 2003 — Fuel Briquettes: A Users Manual<br />

Conclusion<br />

The Fuel briquettes you make have great potential<br />

to be used for fuel that will save our environment<br />

and provide many with employment.<br />

While no social taboos against fuel briquette making<br />

exist to our experience, it is nonetheless a new<br />

product and one that will challenge traditional fuel<br />

wood usage in any part of the world. Fuel briquettes<br />

therefore require strong initial promotion to<br />

gain wide public acceptance. They cannot be introduced<br />

casually. Fuel briquettes must be treated like<br />

a new product and become as popular as, for example,<br />

Coca-Cola. The broad public acceptance is<br />

what attracts the entrepreneurs to produce a<br />

positive economic and social impact in your area.<br />

Legacy Foundation provides:<br />

■ Other training guides in the fuel briquette<br />

making process,<br />

■ Comprehensive training of trainer programs<br />

and services,<br />

■ Marketing support and<br />

■ Technical consulting and backstopping for those<br />

committed to fuel briquette making.<br />

For further information on training programs, or to<br />

order other manuals, please visit The Legacy<br />

Foundation's web site: www.legacyfound.org<br />

We are building a global fuel<br />

briquette making network and<br />

welcome your input and insights.

Technology, Management,<br />

Training and Media Services<br />

for Sustainable Development<br />

4886 Highway 66 Ashland, Oregon, 97520 <strong>USA</strong><br />

Tel: 541 • 448-1559<br />

Fax: 541 • 488-6402<br />

E-mail: info@legacyfound.org<br />

Web Site: www.legacyfound.org