Overt Nominative Subjects in Infinitival Complements Cross - NYU ...

Overt Nominative Subjects in Infinitival Complements Cross - NYU ...

Overt Nominative Subjects in Infinitival Complements Cross - NYU ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

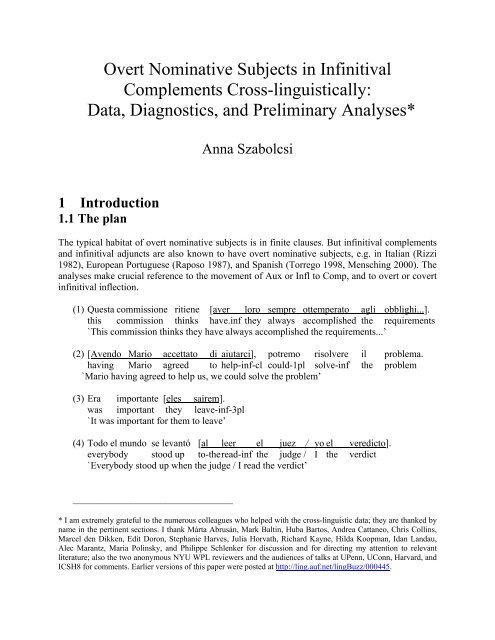

<strong>Overt</strong> <strong>Nom<strong>in</strong>ative</strong> <strong>Subjects</strong> <strong>in</strong> Inf<strong>in</strong>itival<strong>Complements</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>-l<strong>in</strong>guistically:Data, Diagnostics, and Prelim<strong>in</strong>ary Analyses*Anna Szabolcsi1 Introduction1.1 The planThe typical habitat of overt nom<strong>in</strong>ative subjects is <strong>in</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ite clauses. But <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival complementsand <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival adjuncts are also known to have overt nom<strong>in</strong>ative subjects, e.g. <strong>in</strong> Italian (Rizzi1982), European Portuguese (Raposo 1987), and Spanish (Torrego 1998, Mensch<strong>in</strong>g 2000). Theanalyses make crucial reference to the movement of Aux or Infl to Comp, and to overt or covert<strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival <strong>in</strong>flection.(1) Questa commissione ritiene [aver loro sempre ottemperato agli obblighi...].this commission th<strong>in</strong>ks have.<strong>in</strong>f they always accomplished the requirements`This commission th<strong>in</strong>ks they have always accomplished the requirements...’(2) [Avendo Mario accettato di aiutarci], potremo risolvere il problema.hav<strong>in</strong>g Mario agreed to help-<strong>in</strong>f-cl could-1pl solve-<strong>in</strong>f the problem`Mario hav<strong>in</strong>g agreed to help us, we could solve the problem’(3) Era importante [eles sairem].was important they leave-<strong>in</strong>f-3pl`It was important for them to leave’(4) Todo el mundo se levantó [al leer el juez / yo el veredicto].everybody stood up to-the read-<strong>in</strong>f the judge / I the verdict`Everybody stood up when the judge / I read the verdict’_________________________________* I am extremely grateful to the numerous colleagues who helped with the cross-l<strong>in</strong>guistic data; they are thanked byname <strong>in</strong> the pert<strong>in</strong>ent sections. I thank Márta Abrusán, Mark Balt<strong>in</strong>, Huba Bartos, Andrea Cattaneo, Chris Coll<strong>in</strong>s,Marcel den Dikken, Edit Doron, Stephanie Harves, Julia Horvath, Richard Kayne, Hilda Koopman, Idan Landau,Alec Marantz, Maria Pol<strong>in</strong>sky, and Philippe Schlenker for discussion and for direct<strong>in</strong>g my attention to relevantliterature; also the two anonymous <strong>NYU</strong> WPL reviewers and the audiences of talks at UPenn, UConn, Harvard, andICSH8 for comments. Earlier versions of this paper were posted at http://l<strong>in</strong>g.auf.net/l<strong>in</strong>gBuzz/000445.

<strong>NYU</strong> Work<strong>in</strong>g Papers <strong>in</strong> L<strong>in</strong>guistics, Volume 2: Papers <strong>in</strong> Syntax, Spr<strong>in</strong>g 2009 3overt nom<strong>in</strong>atives occur <strong>in</strong>side the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival complement. Second, much like English,Hungarian entirely lacks pronom<strong>in</strong>al doubles of the Italian sort; therefore it elim<strong>in</strong>ates theconfound. Third, go<strong>in</strong>g further, the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival verb <strong>in</strong> the relevant sentences does not occur <strong>in</strong> an<strong>in</strong>itial, “Comp-like” position. This <strong>in</strong>dicates that our k<strong>in</strong>d of overt nom<strong>in</strong>ative subject is notcont<strong>in</strong>gent on “Infl-to-Comp”. Fourth, Hungarian has optionally <strong>in</strong>flected <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itives, but they arenever complements of control verbs, and their overt subjects are <strong>in</strong>variably <strong>in</strong> the dative, not <strong>in</strong>the nom<strong>in</strong>ative (Tóth 2000). This <strong>in</strong>dicates that overtness of the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival subject does notdepend on a richly <strong>in</strong>flected <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itive. Therefore the phenomenon we are concerned with is notidentical to the one illustrated <strong>in</strong> (1) through (4).This paper proposes that the critical feature of these examples is that the overt <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itivalsubject agrees with the f<strong>in</strong>ite verb <strong>in</strong> person and number. This seems trivial <strong>in</strong> the case of control(s<strong>in</strong>ce the f<strong>in</strong>ite subject b<strong>in</strong>ds the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival one), but it will be argued that rais<strong>in</strong>g complementsallow for the same k<strong>in</strong>d of overt nom<strong>in</strong>ative subjects, and there agreement with the f<strong>in</strong>ite rais<strong>in</strong>gverb is more surpris<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong> the absence of DP-movement to the matrix.Specifically, it will be proposed that these overt <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival subjects enter <strong>in</strong>to a longdistanceAgree relation with a f<strong>in</strong>ite <strong>in</strong>flection. Furthermore the same f<strong>in</strong>ite <strong>in</strong>flection may Agreewith more than one subject. Multiple agreement is necessary <strong>in</strong> the control cases (although not<strong>in</strong> the rais<strong>in</strong>g cases). In these respects the proposal is consonant with Ura (1996), Hiraiwa (2001,2005) and Chomsky (2008).The ma<strong>in</strong> goal of this paper is to survey cross-l<strong>in</strong>guistic data, some of which make it likelythat many languages besides Italian and Hungarian exhibit the k<strong>in</strong>d of overt <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival subjectsexemplified by (5)-(6), and some of which suggest that tantaliz<strong>in</strong>gly similar data from otherlanguages may require a different analysis. The languages to be discussed <strong>in</strong>clude, besides Italianand Hungarian, Mexican Spanish, Brazilian Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, F<strong>in</strong>nish, ModernHebrew, Turkish, Norwegian, and Shupamem (Grassfield Bantu). Unless otherwise <strong>in</strong>dicated, allthe data come from my own field work. Draw<strong>in</strong>g from the literature a brief comparison withbackward control/rais<strong>in</strong>g and copy control/rais<strong>in</strong>g data will be offered <strong>in</strong> the end.The rest of this <strong>in</strong>troduction briefly recaps the state of the art <strong>in</strong> connection with overtnom<strong>in</strong>ative subjects and fleshes out a prelim<strong>in</strong>ary account of the cross-l<strong>in</strong>guistic variation.This paper will not attempt either a def<strong>in</strong>itive classification of the languages surveyed or adef<strong>in</strong>itive and unified theoretical account of overt nom<strong>in</strong>atives.1.2 A bird’s eye view of the state of the artThe follow<strong>in</strong>g descriptive claims are widely believed to hold at least of well-studied Europeanlanguages:(11) “No overt subjects <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival complements”Inf<strong>in</strong>itival complements of subject-control verbs and subject-to-subject rais<strong>in</strong>g verbs donot have overt nom<strong>in</strong>ative subjects.(12) “No overt controllees”In control constructions the controllee DP is not an overt pronoun.What would these facts, if they are <strong>in</strong>deed facts, follow from?Given the copy theory of movement/cha<strong>in</strong>s (Chomsky 1995, 2000) and the possibility that

<strong>NYU</strong> Work<strong>in</strong>g Papers <strong>in</strong> L<strong>in</strong>guistics, Volume 2: Papers <strong>in</strong> Syntax, Spr<strong>in</strong>g 2009 4control is an <strong>in</strong>stance of movement/cha<strong>in</strong> formation (Hornste<strong>in</strong> 1999, Boeckx & Hornste<strong>in</strong>, toapp., Bowers, to app.), it is <strong>in</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciple possible for overt DPs to occur <strong>in</strong> the subject positionsmentioned <strong>in</strong> (11). Languages might choose to pronounce all copies, or just some lower copy.The fact that this does not rout<strong>in</strong>ely happen calls for an explanation; the usual assumption is thatthe highest copy is privileged, possibly subject to Bobaljik’s (2002:251) M<strong>in</strong>imize Mismatchpr<strong>in</strong>ciple: “(To the extent possible) privilege the same copy at PF and LF”. Instead or <strong>in</strong> addition,it may be that the highest copy must be pronounced to supply the f<strong>in</strong>ite clause with an overtsubject (cf. the EPP), and/or it may be that lower copies are simply unpronounceable. In oldendays the Case Filter plus the <strong>in</strong>ability of <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival <strong>in</strong>flection to assign abstract Case preventedthe subjects of <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival complements of control and subject-to-subject rais<strong>in</strong>g verbs from be<strong>in</strong>gpronounced (<strong>in</strong> the absence of ECM, <strong>in</strong>flected <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itives, etc.); more recently Null Case wassupposed to expla<strong>in</strong> why PRO is covert (Mart<strong>in</strong> 2001). However, the l<strong>in</strong>k between abstract Caseand morphological case has been severed and the usefulness of postulat<strong>in</strong>g abstract Case hasbeen called <strong>in</strong>to question by Marantz (1991), McFadden (2004), and others. What takes the placeof Case <strong>in</strong> licens<strong>in</strong>g the pronunciation of DPs? Pronouns have been argued to require someagreement relation <strong>in</strong> order to be fully specified (see Kratzer 2006 on bound pronouns, andSigurdsson 2007 for ground<strong>in</strong>g) and all DPs have been argued to need a valued T feature(Pesetsky and Torrego 2006).Turn<strong>in</strong>g to (12), the absence of overt pronom<strong>in</strong>al controllees may simply follow fromsome of the considerations above. If <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival subjects are generally not pronounceable, then an<strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival control complement cannot have an overt subject. It must have a PRO or a pro subject,or no subject at all if it is just a VP (Babby & Franks 1998, Wurmbrand 2003). But Landau’s(2004) theory of control covers both <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itives and subjunctives, and subjunctive clausesrout<strong>in</strong>ely have overt subjects. It is therefore remarkable that Landau’s calculus of control takes itfor granted that the control complement has a null subject. There seems to be some, perhapsunspoken assumption about control that results <strong>in</strong> the controllee always be<strong>in</strong>g phonetically null.Semantic assumptions may do part of the work. Chierchia (1989) proposed that control <strong>in</strong>volvesa so-called de se read<strong>in</strong>g and that PRO is a de se anaphor. But the fact that overt pronouns alsohave de se read<strong>in</strong>gs, and the more recent assumption that control may also <strong>in</strong>volve pro <strong>in</strong>stead ofPRO <strong>in</strong>dicate that more needs to be said. So perhaps “No overt controllees” could result from aconspiracy of the above considerations and more or less <strong>in</strong>dependent facts about obviation. SeeFarkas (1985) for an example of overt controlled pronouns <strong>in</strong> Romanian.My impression of the state of the art is that the theories I am familiar with do not predict(11) and (12) <strong>in</strong> a straightforward manner. But neither do these theories seem to say exactlywhere these generalizations are expected to fail. The present paper supplements the knowncounterexamples with further data that <strong>in</strong>dicate that (11) and (12) are descriptively <strong>in</strong>correct.1.3 A prelim<strong>in</strong>ary account of the cross-l<strong>in</strong>guistic variationUnless otherwise <strong>in</strong>dicated, the data <strong>in</strong> this paper come from my own field work. I amimmensely grateful to the colleagues who made themselves available for multiple rounds ofquestion<strong>in</strong>g. They are thanked by name where the <strong>in</strong>dividual languages are discussed. I hasten toadd that the <strong>in</strong>terpretation of the data as support<strong>in</strong>g or not support<strong>in</strong>g an <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival subjectanalysis is <strong>in</strong>variably m<strong>in</strong>e; my sources may or may not agree with it.Accord<strong>in</strong>g to my present understand<strong>in</strong>g, the languages I have <strong>in</strong>vestigated fall <strong>in</strong>to threema<strong>in</strong> categories: they either have overt nom<strong>in</strong>atives <strong>in</strong> both rais<strong>in</strong>g and control complements, or

<strong>NYU</strong> Work<strong>in</strong>g Papers <strong>in</strong> L<strong>in</strong>guistics, Volume 2: Papers <strong>in</strong> Syntax, Spr<strong>in</strong>g 2009 5at most <strong>in</strong> rais<strong>in</strong>g complements, or <strong>in</strong> neither. In what follows the term “overt <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itivalsubjects” will be shorthand for “overt nom<strong>in</strong>ative subjects of <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival complements of controland rais<strong>in</strong>g verbs”.overt nom<strong>in</strong>ative subjects <strong>in</strong> overt nom<strong>in</strong>ative subjects <strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival rais<strong>in</strong>g complements <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival control complementsYes Possibly No Yes possibly NoHungarian * *Italian * *Spanish * *Br.Portuguese * *Romanian * *M.Hebrew * *Russian * *F<strong>in</strong>nish * *English * *French * *German * *Dutch * *“Yes” <strong>in</strong> a column <strong>in</strong>dicates that I am fairly confident that the nom<strong>in</strong>ative DP is located <strong>in</strong>sidethe complement clause, and that it is, or can be, the subject, as opposed to an emphatic element.“Possibly” <strong>in</strong> the rais<strong>in</strong>g case <strong>in</strong>dicates that the examples have a particular word order and<strong>in</strong>terpretation, but it is not clear yet whether the nom<strong>in</strong>ative DP is located <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itivalcomplement or <strong>in</strong> the matrix. “Possibly” <strong>in</strong> the control case <strong>in</strong>dicates that I have not yet beenable to exclude the emphatic pronoun analysis; this may be due to my lack of expertise or,maybe, the given language does not offer clear clues.What dist<strong>in</strong>guishes the “yes” languages (that have some overt <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival subjects) from the“no” languages (that do not have any)? One idea may be that overt <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival subjects arepossible where the default case is nom<strong>in</strong>ative. This is immediately falsified by German, wherethe default case is nom<strong>in</strong>ative (McFadden 2006) but overt <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival subjects are not found. Asecond idea may be that the dist<strong>in</strong>ctive property of the “yes” languages is that they have visiblyor covertly <strong>in</strong>flected <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itives, cf. Raposo (1987). At least Hungarian <strong>in</strong>dicates that the twophenomena do not pattern together. Hungarian has optional overt <strong>in</strong>flection <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itivalcomplements of impersonal predicates, but the subjects of these are <strong>in</strong>variably <strong>in</strong> the dative, not<strong>in</strong> the nom<strong>in</strong>ative (Tóth 2000). Also, Hungarian has no overt nom<strong>in</strong>ative subjects <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itivaladjuncts like (4), which Torrego has analyzed as <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g pro-drop <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival <strong>in</strong>flection(although it does <strong>in</strong> somewhat archaic un<strong>in</strong>flected participial adjuncts). So it seems that overtsubjects <strong>in</strong> rais<strong>in</strong>g/control complements are not generally dependent on the special features of<strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival <strong>in</strong>flection. A third idea may be that the “yes” languages are all null subject ones. Butcolloquial Brazilian Portuguese is not a null subject language, and colloquial Mexican Spanishappears to avoid null subjects as well. Nevertheless, the overt nom<strong>in</strong>ative subject judgments arethe same <strong>in</strong> the colloquial varieties.I propose that the key observation is that the critical nom<strong>in</strong>ative DP, although located

<strong>NYU</strong> Work<strong>in</strong>g Papers <strong>in</strong> L<strong>in</strong>guistics, Volume 2: Papers <strong>in</strong> Syntax, Spr<strong>in</strong>g 2009 6with<strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival complement, agrees with a superord<strong>in</strong>ate f<strong>in</strong>ite verb <strong>in</strong> person and number.This suggests (13):(13) Hypothesis re: long-distance agreementA sufficient condition for nom<strong>in</strong>ative subjects <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival complements to be overt isif the relevant features of a superord<strong>in</strong>ate f<strong>in</strong>ite <strong>in</strong>flection are transmitted to them (say <strong>in</strong>the manner of long-distance Agree). The cross-l<strong>in</strong>guistic variation <strong>in</strong> the availability ofovert <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival subjects has to do with variation <strong>in</strong> feature transmission.The fundamental deficiency <strong>in</strong> the “no” languages must be that the relevant f<strong>in</strong>ite <strong>in</strong>flectionalfeatures are not transmitted to the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival subject. Could it be that feature transmissionrequires some k<strong>in</strong>d of clause union that only the “yes” languages possess? Not likely. On onehand, German and Dutch have certa<strong>in</strong> clause union phenomena but no overt <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival subjects.More importantly, overt subjects <strong>in</strong> Hungarian, Italian, Spanish, etc. happily occur <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itivalconstructions that do not exhibit any k<strong>in</strong>d of <strong>in</strong>dependently recognizable clause union. I concludethat the “transparency” of <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival clauses is not at issue.Let us first focus on control constructions. They have thematic subjects both <strong>in</strong> the f<strong>in</strong>itematrix and <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival complement. For all we know, the f<strong>in</strong>ite subject must always be alegitimately nom<strong>in</strong>ative DP. Deictically <strong>in</strong>terpreted null pronom<strong>in</strong>al subjects occur <strong>in</strong> exactly thesame environments as their overt counterparts or as lexical DPs. But then one and the same f<strong>in</strong>ite<strong>in</strong>flection must take care of the f<strong>in</strong>ite subject and the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival one. This suggests (14):(14) Hypothesis re: the multi-agreement parameterLanguages vary as to whether a s<strong>in</strong>gle f<strong>in</strong>ite <strong>in</strong>flection may share features with morethan one nom<strong>in</strong>ative DP.These hypotheses suggest the possibilities laid out <strong>in</strong> (15), which <strong>in</strong>corporates multi-agreement.Which of the three options is realized <strong>in</strong> a language depends on the needs of expletives and howmulti-agreement is constra<strong>in</strong>ed.(15) Configurations that might allow overt <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival subjects:a. (...) Rais<strong>in</strong>g-V f<strong>in</strong>ite [ DP nom V <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itive ...b. DP nom Rais<strong>in</strong>g-V f<strong>in</strong>ite [ DP nom V <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itive ...c. DP nom Control-V f<strong>in</strong>ite [ DP nom V <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itive ...In (15a) the matrix clause has no thematic subject, and the constellation is legitimate if thelanguage does not need a nom<strong>in</strong>ative expletive <strong>in</strong> the subject position but, <strong>in</strong>stead, it may have anon-nom<strong>in</strong>ative topic, or may go without a topic and possibly move the verb <strong>in</strong>to a higher <strong>in</strong>itialposition. If one of these circumstances obta<strong>in</strong>s, only the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival subject needs to agree withthe f<strong>in</strong>ite <strong>in</strong>flection and so (15a) does not even require multi-agreement.If the language needs a nom<strong>in</strong>ative expletive <strong>in</strong> the f<strong>in</strong>ite subject position, the question iswhether multi-agreement requires all the DPs l<strong>in</strong>ked to the same <strong>in</strong>flection to be bound together.If co-b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g is required, (15b) is not possible, s<strong>in</strong>ce an expletive cannot b<strong>in</strong>d, or be co-bound

<strong>NYU</strong> Work<strong>in</strong>g Papers <strong>in</strong> L<strong>in</strong>guistics, Volume 2: Papers <strong>in</strong> Syntax, Spr<strong>in</strong>g 2009 7with, a thematic DP. If multi-agreement only requires non-conflict<strong>in</strong>g (unifiable) morphologicalfeatures on the DPs <strong>in</strong>volved, then (15b) is possible.F<strong>in</strong>ally, multi-agreement makes (15c) possible, as long as control, which obviously<strong>in</strong>volves b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g, does not lead to a Condition C violation. In other words, <strong>in</strong> (15c) the controllerDP may be a null or overt pronoun, or a name, or an operator – but the controllee DP may onlybe a pronoun, which can be bound from outside its local doma<strong>in</strong>.Although the theoretical options are fairly clear, whether the conditions for (15a) or for(15b) obta<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> a language is a difficult matter. For example, it is debated whether somelanguages that have no overt nom<strong>in</strong>ative expletives have phonetically null ones or not. So theanalysis of languages like Russian and F<strong>in</strong>nish, where overt <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival subjects occur at most <strong>in</strong>rais<strong>in</strong>g constructions is especially delicate; is that LO-scop<strong>in</strong>g nom<strong>in</strong>ative DP really <strong>in</strong>side the<strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival clause? I will make suggestions but will not be able to provide def<strong>in</strong>itive analyses. Atthe same time, Russian/F<strong>in</strong>nish-type languages are extremely important. The reason<strong>in</strong>g abovesuggests that it is easier for a language to have overt nom<strong>in</strong>ative subjects <strong>in</strong> rais<strong>in</strong>g complements(15a) than <strong>in</strong> control complements (15c). But at least <strong>in</strong> the sample I have studied onlyRussian/F<strong>in</strong>nish-type languages have overt subjects <strong>in</strong> rais<strong>in</strong>g but not <strong>in</strong> control complements. Ifthey turn out to be misanalyzed (and no other language steps <strong>in</strong>to their place), that would castdoubt upon the approach proposed above. Therefore the data are <strong>in</strong>cluded, despite the unsettledstate of the analysis.Feature transmission might fail for <strong>in</strong>dependent reasons. H. Koopman (p.c.) has observedthat the ma<strong>in</strong> demarcation l<strong>in</strong>e between “yes” and “no” languages may correlate with the positionof the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival verb. In the clear “no” languages”, French, English, German, and Dutch,<strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival verbs occupy a lower position than either their f<strong>in</strong>ite counterparts <strong>in</strong> the samelanguages or their <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival counterparts <strong>in</strong> Hungarian, Italian, etc. This may preventtransmission of the features of the matrix <strong>in</strong>flection to the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival subject. Such considerationscould yield a further nuanced picture, but I cannot pursue them <strong>in</strong> this paper.2 Develop<strong>in</strong>g the diagnostics -- HungarianObta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the relevant data requires two th<strong>in</strong>gs. One is careful attention to the truth conditions ofcerta<strong>in</strong>, sometimes colloquial, sentences. We shall see that the nom<strong>in</strong>ative DPs we are concernedwith always scope <strong>in</strong>side the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival clause (exhibit what I will call the LO read<strong>in</strong>g). Thesecond crucial task is to show that these DPs are <strong>in</strong>deed the subjects of <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival clauses, asopposed to somehow displaced f<strong>in</strong>ite subjects or emphatic elements. A detailed discussion ofHungarian will be used for the purpose of develop<strong>in</strong>g the diagnostics. Well-establishedgeneralizations as well as some new facts about Hungarian make it pla<strong>in</strong> that some of theHungarian examples def<strong>in</strong>itely <strong>in</strong>volve <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival subjects. The fact that other Hungarianexamples pattern entirely consistently with these, and the fact that examples from Italian,Spanish, etc. seem to pattern consistently with the Hungarian data make it plausible that theyrepresent the same phenomena. But I will not attempt to expla<strong>in</strong> why overt <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival subjects <strong>in</strong>Italian, Spanish, etc. occur <strong>in</strong> exactly those word order positions where they do, and why someword orders are ambiguous <strong>in</strong> one language but not <strong>in</strong> another. Such detailed analyses have to beleft to the experts.The structure of this section is as follows. Section 2.1 sets out to familiarize the English

<strong>NYU</strong> Work<strong>in</strong>g Papers <strong>in</strong> L<strong>in</strong>guistics, Volume 2: Papers <strong>in</strong> Syntax, Spr<strong>in</strong>g 2009 8speak<strong>in</strong>g reader with the mean<strong>in</strong>gs of the sentences this paper focuses on. 2.2 argues that ournom<strong>in</strong>ative DP is located <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival complement, and section 2.3, that it is none other thanthe subject of that complement. Section 2.4 discusses agreement with the f<strong>in</strong>ite verb. Section 2.5comments on the de se <strong>in</strong>terpretation of the subjects of control complements.The discussion of the other languages will presuppose that the reader is familiar with thedetailed analysis of Hungarian, and will be much shorter.2.1 What do these sentences mean?The reason why this question is critical is that the nom<strong>in</strong>ative DPs under <strong>in</strong>vestigation are scopetak<strong>in</strong>g operators or are modified by scope tak<strong>in</strong>g particles like `too’ and `only’, and <strong>in</strong> thesentences where they are claimed to occur <strong>in</strong>side the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival clause they take scope with<strong>in</strong> thatclause, carry<strong>in</strong>g what will be called the LO read<strong>in</strong>g. Many of the LO read<strong>in</strong>gs are not expressible(without complicated circumscription) unless the language makes overt <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival subjectsavailable. Other LO read<strong>in</strong>gs may be expressible, but not unambiguously. Thus the raison d’êtrefor the overtness of such subjects is to satisfy an <strong>in</strong>terface need and to m<strong>in</strong>imize the mismatchbetween PF and LF. I propose to <strong>in</strong>terpret this <strong>in</strong>terface need as one that calls for a systematicway to express a particular k<strong>in</strong>d of truth-conditional content, even though <strong>in</strong> some <strong>in</strong>stances thereis an alternative, ambiguous expression available. Roughly the same <strong>in</strong>terpretation is needed toexpla<strong>in</strong> why Hungarian generally offers a way to <strong>in</strong>dicate scope relations <strong>in</strong> surface structure (seee.g. Brody & Szabolcsi 2003), even though some of those truth-conditional contents would beexpressible <strong>in</strong> less transparent ways as well, as <strong>in</strong> English.The fact that English, French, German, and Dutch lack overt <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival subjects of the sortunder discussion has the practical consequence that the reader of this paper may f<strong>in</strong>d it difficultto form an <strong>in</strong>tuitive grasp of the examples. The goal of this section is to set the stage by giv<strong>in</strong>g an<strong>in</strong>formal sense of their mean<strong>in</strong>gs. We use English sentences that do not have the same structuresas the Hungarian ones but have similar mean<strong>in</strong>gs.First consider rais<strong>in</strong>g. Perlmutter (1970) showed that English beg<strong>in</strong> has a rais<strong>in</strong>g version.We use the aspectual rais<strong>in</strong>g verb beg<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>stead of seem, for two reasons. One is that Hungarianlátszik `seem’ primarily takes either <strong>in</strong>dicative or small clause complements and does not easilycomb<strong>in</strong>e with <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itives. Thus us<strong>in</strong>g beg<strong>in</strong> lays better groundwork for the rest of the paper.Another reason is that the truth conditional effect of an operator scop<strong>in</strong>g either <strong>in</strong> the matrix or <strong>in</strong>the complement is much sharper with the aspectual predicate than with the purely <strong>in</strong>tensionalone; we can get two logically <strong>in</strong>dependent read<strong>in</strong>gs. Consider two scenarios and sentence (18).(16) The HI scenario: Total numbers grow<strong>in</strong>g, number of first-timers decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gIn April, 4 actresses got their first good reviews and then cont<strong>in</strong>ued to get ones.In May, another 2 actresses got their first good reviews and then cont<strong>in</strong>ued to get ones.No other changes happened.(17) The LO scenario: Total numbers decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, number of first-timers stay<strong>in</strong>g the sameIn April, 10 actresses got good reviews, 4 among them for the first time.In May, 8 of the above 10 actresses didn’t get good reviews. But another 4 actresses gottheir first good reviews.No other changes happened.

<strong>NYU</strong> Work<strong>in</strong>g Papers <strong>in</strong> L<strong>in</strong>guistics, Volume 2: Papers <strong>in</strong> Syntax, Spr<strong>in</strong>g 2009 9(18) Fewer actresses began to get good reviews <strong>in</strong> May.(a) `Fewer actresses got their first good reviews <strong>in</strong> May than earlier’(b) `It began to be the case <strong>in</strong> May that fewer actresses overall were gett<strong>in</strong>g goodreviews than earlier’(18) is ambiguous. Read<strong>in</strong>g (a) is true <strong>in</strong> the HI scenario but false <strong>in</strong> the LO one. It will belabeled the HI read<strong>in</strong>g. Read<strong>in</strong>g (b) is false <strong>in</strong> the HI scenario and true <strong>in</strong> the LO one. It will becalled the LO read<strong>in</strong>g, and this is the one relevant to us. Crucially, on the LO read<strong>in</strong>g we are not<strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> who began to get good reviews but, rather, what k<strong>in</strong>d of overall situation began toobta<strong>in</strong>.Given that neither the predicate get good reviews nor the predicate beg<strong>in</strong> to get goodreviews have agentive subjects (i.e. <strong>in</strong>stigators of an action), beg<strong>in</strong> is def<strong>in</strong>itely a rais<strong>in</strong>g verb onthe (b), LO read<strong>in</strong>g. (It is plausibly also a rais<strong>in</strong>g verb on the (a), HI read<strong>in</strong>g of (18). This latterfact is irrelevant to us though.) In English (18) the LO read<strong>in</strong>g appears to be a result of “scopereconstruction” <strong>in</strong> the presence of A-movement, similarly to the classical example below (May1985 and many others, though see Lasnik 1999 for arguments aga<strong>in</strong>st reconstructiom):(19) A unicorn seems to be approach<strong>in</strong>g.HI `There is a particular unicorn that seems to be approach<strong>in</strong>g’LO `It seems as though a unicorn is approach<strong>in</strong>g’In English the availability of the LO read<strong>in</strong>g with beg<strong>in</strong> is facilitated by the presence of atemporal adjunct. In Hungarian the two read<strong>in</strong>gs of (18) would be expressed us<strong>in</strong>g differentconstituent orders, and no temporal adjunct is necessary to obta<strong>in</strong> the LO read<strong>in</strong>g. Moreover, theLO read<strong>in</strong>g is available with all operators, whereas <strong>in</strong> English the choice is delicate.(20) Kevesebb színésznő kezdett el jó kritikákat kapni.fewer actress began.3sg prt good reviews.acc get.<strong>in</strong>fHI `Fewer actresses got their first good reviews’(21) Elkezdett kevesebb színésznő kapni jó kritikákat.prt-began.3sg fewer actress get.<strong>in</strong>f good reviews.accLO `It began to be the case that fewer actresses overall were gett<strong>in</strong>g good reviews’Next consider control. The particle too associates with different DPs <strong>in</strong> (22) and (23). Theexample most relevant to us is (23): here too associates with the PRO subject of be tall. Krifka(1998) argues that postposed stressed additive particles, like English too, may associate evenwith a phonetically null element if that is a contrastive topic <strong>in</strong> his sense. The well-knownread<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> (22) is the HI read<strong>in</strong>g; the more novel one <strong>in</strong> (23) the LO read<strong>in</strong>g.(22) Mary wants/hates to be tall. I want/hate to be tall too.HI `I too want/hate it to be the case that I am tall’(23) Mary is tall. I want/hate to be tall too.LO `I want/hate it to be the case that I too am tall’

<strong>NYU</strong> Work<strong>in</strong>g Papers <strong>in</strong> L<strong>in</strong>guistics, Volume 2: Papers <strong>in</strong> Syntax, Spr<strong>in</strong>g 2009 10If too attaches to the matrix subject, the want-example is still ambiguous, see (24). But thevariant with hate lacks the LO read<strong>in</strong>g; the sequence <strong>in</strong> (25b) is <strong>in</strong>coherent.(24) a. Mary wants to be tall. I too want to be tall.HI `I too want it to be the case that I am tall’b. Mary is tall. I too want to be tall.LO `I want it to be the case that I too am tall’(25) a. Mary hates to be tall. I too hate to be tall.HI `I too hate it that I am tall’b. Mary is tall. #I too hate to be tall.Intended: LO `I hate it that I too am tall’In Hungarian the two read<strong>in</strong>gs are expressed by different constituent orders, <strong>in</strong> a manner parallelto (20) and (21).(26) Én is szeretnék / utálok magas lenni.I too would-like.1sg / hate.1sg tall be.<strong>in</strong>fHI `I too want/hate it to be the case that I am tall’(27) Szeretnék / Utálok én is magas lenni.would-like.1sg / hate.1sg I too tall be.<strong>in</strong>fLO `I want/hate it to be the case that I too am tall’To summarize, when a nom<strong>in</strong>ative DP is associated with a suitable scope-tak<strong>in</strong>g operator,English can express LO read<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> both control and rais<strong>in</strong>g constructions. But these read<strong>in</strong>gscome about <strong>in</strong> specifically scope-related ways, by “scope reconstruction” or <strong>in</strong> view of the abilityof postposed additive particles under stress to associate with PRO. The reader should bear theseread<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d when contemplat<strong>in</strong>g the Hungarian examples that carry LO read<strong>in</strong>gs, but thispaper will not <strong>in</strong>vestigate English any further.This paper focuses on Hungarian examples that unambiguously carry the LO read<strong>in</strong>g, suchas (21) and (27). Here the whole nom<strong>in</strong>ative DP occurs <strong>in</strong> a special position. It will be arguedthat this is the position of the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival subject.2.2 “Our nom<strong>in</strong>ative DP” is located <strong>in</strong>side the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival clauseThe present section argues that the nom<strong>in</strong>ative DP <strong>in</strong> examples like (21) and (27) is located<strong>in</strong>side the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival clause, and the next section argues that it is the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival subject. Until suchtime as the arguments are completed, the DP under <strong>in</strong>vestigation will be neutrally referred to as“our nom<strong>in</strong>ative DP”.Recall that <strong>in</strong> the Hungarian sentences carry<strong>in</strong>g LO read<strong>in</strong>gs, our nom<strong>in</strong>ative DPs occur <strong>in</strong>postverbal position. Hungarian is known to map scope relations to l<strong>in</strong>ear order and <strong>in</strong>tonation(see Brody and Szabolcsi 2003, among many others), so this may seem like a simple <strong>in</strong>stance ofthe same correspondence. Indeed, DP is `DP too’ may occur either preverbally or postverbally <strong>in</strong>mono-clausal examples and so (27) by itself is not diagnostic. The ma<strong>in</strong> reason why the particleis `too’ was used above is that it helped conjure up English counterparts. The placement of csak

<strong>NYU</strong> Work<strong>in</strong>g Papers <strong>in</strong> L<strong>in</strong>guistics, Volume 2: Papers <strong>in</strong> Syntax, Spr<strong>in</strong>g 2009 12same sequence occurs <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival clauses that exhibit what they call “the English order”, i.e. nosuperficially noticeable restructur<strong>in</strong>g. This descriptive claim has never been contested. Compare,for example, f<strong>in</strong>ite (36) and <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival (37). The l<strong>in</strong>ear and scopal order of operator phrases <strong>in</strong> thepreverbal field is topic (RefP), quantifier (DistP), and focus (with or without csak `only’) <strong>in</strong> bothcases.(36) Holnap m<strong>in</strong>denről (csak) én beszélek.tomorrow everyth<strong>in</strong>g-about only I talk-1sg`Tomorrow everyth<strong>in</strong>g will be such that it is me who talks about it/only I talk about it’(37) Szerettem volna holnap m<strong>in</strong>denről (csak) én beszélni.would.have.liked-1sg tomorrow everyth<strong>in</strong>g-about only I talk-<strong>in</strong>f`I would have liked it to be the case that tomorrow everyth<strong>in</strong>g is such that it is me whotalks about it/ only I talk about it’These orders make it pla<strong>in</strong> that csak én occupies the same focus position <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival clauseas <strong>in</strong> the f<strong>in</strong>ite one. There is simply no other way for it to occur where it does. Crucial to us is thefact that constituent order shows our nom<strong>in</strong>ative DPs to be located <strong>in</strong>side the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival clause.Thus the bracket<strong>in</strong>g is as follows:(27’) Szeretnék [én is magas lenni].(35’) Szeretnék [nem én lenni magas].(37’) Szerettem volna [holnap m<strong>in</strong>denről (csak) én beszélni].Example (37) argues for two further po<strong>in</strong>ts. First, it shows that our nom<strong>in</strong>ative DP does nothave to immediately follow either the matrix or the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival verb and thus to be governed by it,to use older term<strong>in</strong>ology. An arbitrarily long sequence of operators may separate it from thematrix verb, and the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival verb never precedes it. Therefore its overtness cannot be due to“Exceptional Case Mark<strong>in</strong>g” or to “Infl-to-Comp” movement.A second important po<strong>in</strong>t has to do with the absence of clause union (restructur<strong>in</strong>g). Thesuspicion might have arisen that the phenomenon we are <strong>in</strong>vestigat<strong>in</strong>g somehow requires clauseunion. The long operator sequence <strong>in</strong> (37) already <strong>in</strong>dicates that its <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival clause is not areduced complement; Koopman & Szabolcsi (2000: Chapter 6) argue that it is a full CP. Furtherevidence that clause union is not <strong>in</strong>volved comes from the <strong>in</strong>ventory of matrix verbs. Considerutál `hate’, cross-l<strong>in</strong>guistically not a restructur<strong>in</strong>g verb, and el-felejt `forget’. El-felejt has aprefix, and prefixal verbs never restructure <strong>in</strong> Hungarian. Both verbs take <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itivalcomplements that conta<strong>in</strong> overt nom<strong>in</strong>atives; <strong>in</strong> fact, all subject control verbs do.(38) Utálok csak én dolgozni.hate-1sg only I work-<strong>in</strong>fLO `I hate it that only I work’(39) Nem felejtettem el én is aláírni a levelet.not forgot-1sg pfx I too sign-<strong>in</strong>f the letter-accLO `I didn’t forget to br<strong>in</strong>g it about that I too sign the letter’ (cf. I remembered to sign ittoo)

<strong>NYU</strong> Work<strong>in</strong>g Papers <strong>in</strong> L<strong>in</strong>guistics, Volume 2: Papers <strong>in</strong> Syntax, Spr<strong>in</strong>g 2009 13Szabolcsi (2005) discussed the control data above and tentatively concluded that Hungarian hasovert subjects <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival complements.As we saw <strong>in</strong> the preced<strong>in</strong>g section, not only control but also rais<strong>in</strong>g complements exhibitthe phenomenon at hand. Szabolcsi (2005) mentioned examples with elkezd `beg<strong>in</strong>’ and thefuturate verb fog, but glossed over the fact that they <strong>in</strong>volve rais<strong>in</strong>g, not control. Bartos (2006a)and Márta Abrusán (p.c.) drew attention to their rais<strong>in</strong>g character. The arguments fromconstituent order apply to rais<strong>in</strong>g complements exactly as they do to control complements, so Iadd the brackets around the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival clause right away.(40) Nem én kezdtem el [éjszaka dolgozni].not I began-1sg pfx at.night work.<strong>in</strong>fHI `It is not me who began to work at night’(41) Elkezdtem [nem én dolgozni éjszaka].began-1sg not I work-<strong>in</strong>f at.nightLO `It began to be the case that it is not me who works at night’(42) Csak én nem fogok [dolgozni éjszaka].only I not will-1sg work-<strong>in</strong>f at.nightHI `I am the only one who will not work at night’(43) Nem fogok [csak én dolgozni éjszaka].not will-1sg only I work-<strong>in</strong>f at.nightLO `It is not go<strong>in</strong>g to be the case that only I work at night’(44) Holnap fogok [m<strong>in</strong>denkivel csak én beszélni].tomorrow will-1sg everyone-with only I talk-<strong>in</strong>fLO `Tomorrow is the day when for everyone x, only I will talk with x’We conclude that <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival complements of both subject control verbs and subject-tosubjectrais<strong>in</strong>g verbs <strong>in</strong> Hungarian can conta<strong>in</strong> an overt nom<strong>in</strong>ative DP.2.3 “Our nom<strong>in</strong>ative DP” is the subject of the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival clause2.3.1 An argument from B<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g TheoryWe have seen that our nom<strong>in</strong>ative DP is located <strong>in</strong>side the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival clause, but does it orig<strong>in</strong>atethere? One important argument comes from the B<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g Theory.The crucial observation is that the nom<strong>in</strong>ative DP <strong>in</strong>side a control complement can only bea personal pronoun whereas the one <strong>in</strong>side a rais<strong>in</strong>g complement can be a referential DP. This isexactly as expected if the DP orig<strong>in</strong>ates <strong>in</strong> the complement clause. In the case of control, ournom<strong>in</strong>ative DP is bound by the matrix subject (an overt one or dropped pro). If the two are not <strong>in</strong>the same local doma<strong>in</strong>, a pronoun can be so bound (Condition B), but a referential expressioncannot (Condition C). Thus we do not expect to f<strong>in</strong>d lexical DPs <strong>in</strong> the subject position of thecontrol complement. Indeed, (46) is sharply degraded as compared to (45):

<strong>NYU</strong> Work<strong>in</strong>g Papers <strong>in</strong> L<strong>in</strong>guistics, Volume 2: Papers <strong>in</strong> Syntax, Spr<strong>in</strong>g 2009 14(45) Utálna m<strong>in</strong>dig csak ő kapni büntetést.would-hate.3sg always only he get.<strong>in</strong>f punishment.acc`He would hate it if always only he got punished’(46) *Utálna m<strong>in</strong>dig csak Péter kapni büntetést.would-hate.3sg always only Peter get.<strong>in</strong>f punishment.acc<strong>in</strong>tended: `Peter would hate it if always only he got punished’On the other hand, the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival complement of a rais<strong>in</strong>g verb is not bound by another DP withan <strong>in</strong>dependent thematic role; it is free to be a pronoun or a lexical DP. This is what we f<strong>in</strong>d.(47) Elkezdett m<strong>in</strong>dig csak Péter kapni büntetést.began-3sg always only Peter get.<strong>in</strong>f punishment.acc`It began to be the case that always only Peter got punished’The contrast <strong>in</strong> (46)-(47) is multiply important. First, it cl<strong>in</strong>ches the Hungarian analysis.Second, it serves as an important diagnostic tool for work on other languages. And third, thiscontrast h<strong>in</strong>ts at the proper analysis. It makes it less likely for example that we are deal<strong>in</strong>g with acase of backward control (with or without control-as-rais<strong>in</strong>g). The default prediction of thebackward control analysis would be that the lower subject can be pronounced as is, withoutbe<strong>in</strong>g somehow reduced to a pronoun. This is <strong>in</strong>deed what the backward control literature f<strong>in</strong>ds(Pol<strong>in</strong>sky and Potsdam 2002, Alexiadou et al. 2008; though see Boeckx et al. 2007). Thus thetheoretical challenge is not just to account for when a lower l<strong>in</strong>k <strong>in</strong> a cha<strong>in</strong> can be spelled out <strong>in</strong> apronom<strong>in</strong>al form – we are fac<strong>in</strong>g the general question of when a DP can be pronounced.2.3.2 A potential confound <strong>in</strong> cross-l<strong>in</strong>guistic counterpartsThe fact that our nom<strong>in</strong>ative DP <strong>in</strong> control complements must be a pronoun opens the way for apotential confound. Perhaps that nom<strong>in</strong>ative DP is not the subject, just a “pronom<strong>in</strong>al double” ofthe real PRO or pro subject? This question arises especially because languages like Italian,Spanish, and Modern Hebrew have such pronom<strong>in</strong>al doubles <strong>in</strong> mono-clausal examples:(48) Gianni è andato solo lui a Milano.`As for Gianni, only he went to Milan’It turns out that <strong>in</strong> Hungarian, just like <strong>in</strong> English, such examples are simply ungrammatical. Letus consider two potential cases; first, emphatic pronouns. In Hungarian emphatics are reflexives(maga) and not personal pronouns (ő), as po<strong>in</strong>ted out <strong>in</strong> Szabolcsi (2005).(49) a. Péter maga is dolgozott. b. Péter nem maga dolgozott.Peter himself too worked Peter not himself worked`Peter himself worked too’ `Peter didn’t work himself’(50) a. *Péter ő is dolgozott. b. *Péter nem ő dolgozott.Peter he too worked Peter not he worked

<strong>NYU</strong> Work<strong>in</strong>g Papers <strong>in</strong> L<strong>in</strong>guistics, Volume 2: Papers <strong>in</strong> Syntax, Spr<strong>in</strong>g 2009 15(51) a. (Ő) maga is dolgozott. b. (Ő) nem maga dolgozott.he himself too worked he not himself worked`He himself worked too’`He didn’t work himself’(52) a. *Ő ő is dolgozott. b. *Ő nem ő dolgozott.he he too worked he not he workedSecond, consider pronom<strong>in</strong>al placeholders for 3rd person left dislocated expressions. In mydialect (which may or may not co<strong>in</strong>cide with the Budapest, or urban, variety) these placeholdersare distal demonstratives, never personal pronouns. (The construction belongs to the spokenlanguage and would not be found <strong>in</strong> the writ<strong>in</strong>g of educated speakers. In this respect it contrastssharply with our nom<strong>in</strong>ative DPs, which do not violate the norm of the literary language.)(53) a. Péter az dolgozott. b. A fiúk azok dolgoztak.Peter that worked the boys those worked`Peter worked’`The boys worked’To identify such placeholders, it is to be noted that they practically cliticize to the topic andcannot be separated or focused:(54) a. *Péter tegnap az dolgozott. b. *Péter csak az dolgozott.Peter yesterday that worked Peter only that workedPronom<strong>in</strong>al subjects do not participate <strong>in</strong> this construction:(55) a. *Én az dolgozott/dolgoztam.I that worked-3sg/worked-1sgb. *Ő az dolgozott.he that worked-3sgI am aware that there are speakers who use the personal pronoun ő <strong>in</strong> the place of demonstrativeaz:(56) a. Péter ő dolgozott. b. A fiúk ők dolgoztak.Peter he worked the boys they worked`Peter worked’`The boys worked’This fact could be a confound if only such speakers, but not speakers like myself, acceptednom<strong>in</strong>ative personal pronouns <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival complements and if the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival construction weresimilarly restricted to 3rd person. This is not the case. All the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival data reported <strong>in</strong> thispaper are perfect for speakers like myself, who do not use (56).These facts show that the Hungarian control construction under discussion has no possiblesource <strong>in</strong> emphatic or placeholder pronouns.

<strong>NYU</strong> Work<strong>in</strong>g Papers <strong>in</strong> L<strong>in</strong>guistics, Volume 2: Papers <strong>in</strong> Syntax, Spr<strong>in</strong>g 2009 162.3.3 Complemented pronounsBut we can do even better. Postal (1966) observed that personal pronouns <strong>in</strong> English may take anoun complement. This observation is one of the cornerstones of the hypothesis that suchpronouns are determ<strong>in</strong>ers.(57) We l<strong>in</strong>guists and you philosophers should talk more to each other.(58) You troops go South and you troops go North.Such complemented pronouns do not <strong>in</strong>duce a Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple C violation:(59) We know that only we l<strong>in</strong>guists can do this.If Condition C is the only reason why our nom<strong>in</strong>ative DP <strong>in</strong> a control complement must bepronom<strong>in</strong>al, then we predict that the pronouns we analyze as overt subjects can take a nouncomplement. This is <strong>in</strong>deed the case. The grammaticality of (60) was observed by Anikó Lipták(Huba Bartos, p.c.). The same possibility exists with rais<strong>in</strong>g verbs, as <strong>in</strong> (61):(60) Szeretnénk csak mi nyelvészek kapni magasabb fizetést.would.like-1pl only we l<strong>in</strong>guists get-<strong>in</strong>f higher salary-acc`We would like it to be the case that only we l<strong>in</strong>guists get a higher salary’(61) Elkezdtünk nem mi nyelvészek ülni az első sorban.began-1pl not we l<strong>in</strong>guists sit-<strong>in</strong>f the first row-<strong>in</strong>`It began to be the case that not we l<strong>in</strong>guists sit <strong>in</strong> the first row’And similarly with numerals:(62) Szeretnénk csak mi háman kapni magasabb fizetést.would.like-1pl only we three.sfx get-<strong>in</strong>f higher salary-acc`We would like it to be the case that only we three get a higher salary’(63) Elkezdtünk nem mi hárman ülni az első sorban.began-1pl not we three.sfx sit-<strong>in</strong>f the first row-<strong>in</strong>`It began to be the case that not we three sit <strong>in</strong> the first row’The cross-l<strong>in</strong>guistic significance of complemented pronouns is that <strong>in</strong> Italian they do notfunction as emphatic or placeholder pronouns <strong>in</strong> mono-clausal examples:(64) Context: The philosophers say, `Only we philosophers work’. The l<strong>in</strong>guists reply,(i) Guarda che noi abbiamo lavorato sodo anche noi!look that we have.1pl worked hard also we(ii) *Guarda che noi abbiamo lavorato sodo anche noi l<strong>in</strong>guisti!look that we have.1pl worked hard also we l<strong>in</strong>guistsHence, if noi l<strong>in</strong>guisti occurs <strong>in</strong>side control complements with the characteristic <strong>in</strong>terpretation

<strong>NYU</strong> Work<strong>in</strong>g Papers <strong>in</strong> L<strong>in</strong>guistics, Volume 2: Papers <strong>in</strong> Syntax, Spr<strong>in</strong>g 2009 18(68) Elkezdtek [csak a fiúk dolgozni éjszaka].began-3pl only the boys work-<strong>in</strong>f at.nightLO: `It began to be the case that only the boys work at night’The fact that the pronoun <strong>in</strong> (66) agrees with the f<strong>in</strong>ite control verb is not very surpris<strong>in</strong>g; afterall, it is controlled by the subject of that verb. Agreement with the matrix verb is moreremarkable <strong>in</strong> the rais<strong>in</strong>g examples (67)-(68), s<strong>in</strong>ce we have no evidence of én and a fiúk everoccurr<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the matrix clause.If the matrix agreement morpheme is removed, effectively turn<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>flection <strong>in</strong>to 3sg,which <strong>in</strong> most verb classes is morphologically unmarked, all these become a word salad:(69) ***Utál [ csak én dolgozni].hate.3sg only I work-<strong>in</strong>f(70) ***Nem fog [csak én dolgozni éjszaka].not will.3sg only I work-<strong>in</strong>f at.night(71) ***Elkezdett [csak a fiúk dolgozni éjszaka].began.3sg only the boys work-<strong>in</strong>f at.nightWhen agreement is not possible, there is no nom<strong>in</strong>ative <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival subject. This predicts,correctly, that <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival complements of object control verbs have no nom<strong>in</strong>ative subjects, s<strong>in</strong>cethe matrix verb is committed to agree with a different argument. Compare object controlkényszerít `force’ with the agree<strong>in</strong>g unaccusative version, kényszerül `be forced’:(72) *Kényszerítettek (téged) [te is dolgozni].forced.3pl you,sg.acc you,sg.nom too work-<strong>in</strong>f(73) Kényszerültél [te is dolgozni].was.forced.2sg you,sg too work-<strong>in</strong>fLO `You (sg.) were forced to work too’As is the case with nom<strong>in</strong>atives <strong>in</strong> general, the pert<strong>in</strong>ent agreement must be subject- and notobject-agreement. So (74), where the verb, exceptionally <strong>in</strong> the language, agrees not only withthe 1sg subject but also with the 2person object, patterns exactly as (72):(74) *Kényszerítettelek (téged) [te is dolgozni].forced.3pl+2pers you,sg.acc you,sg.nom too work-<strong>in</strong>fAgreement has to be “completely matched”:(75) *Kényszerülünk [én/te is dolgozni].are.forced.1pl I.nom/you,sg.nom too work.<strong>in</strong>fLikewise there are no overt nom<strong>in</strong>ative subjects <strong>in</strong> free-stand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itives that function as rudeor military imperatives:

<strong>NYU</strong> Work<strong>in</strong>g Papers <strong>in</strong> L<strong>in</strong>guistics, Volume 2: Papers <strong>in</strong> Syntax, Spr<strong>in</strong>g 2009 19(76) (*Maga is) Távozni!you too leave-<strong>in</strong>f`Leave!’The possibility of overt nom<strong>in</strong>ative subjects with controlled purpose adjuncts is dubious. I cannotdecide whether they are marg<strong>in</strong>ally acceptable:(77) Péter a balkonon aludt. ?? Bementem a hálószobába én is aludni.`Peter was sleep<strong>in</strong>g on the balcony. I went <strong>in</strong> the bedroom to sleep too’Further support<strong>in</strong>g evidence is offered by consider<strong>in</strong>g “imposters” <strong>in</strong> the sense of Coll<strong>in</strong>sand Postal (2008); roughly, names or def<strong>in</strong>ites “act<strong>in</strong>g as” first person pronouns. As the authorsobserve, imposters do not give rise to Condition C effects <strong>in</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> circumstances:(78) I i th<strong>in</strong>k that Daddy i should get the prize. [Daddy speak<strong>in</strong>g](79) I i believe that this reporter i deserves the credit. [the reporter speak<strong>in</strong>g](80) shows that Hungarian has imposters:(80) Father wants to go somewhere alone and child <strong>in</strong>sists on accompany<strong>in</strong>g him.Father says:Azt hiszem, hogy csak Apukának kellene menni.that-acc believe-1sg that only Daddy-dat should go-<strong>in</strong>f`I(=Daddy) th<strong>in</strong>k that only Daddy should go’The question is whether <strong>in</strong> the control cases, the overt nom<strong>in</strong>ative subject <strong>in</strong> the embedded clausecan be an imposter or not. (81a) is good, but (81b) with an imposter, signaled by the 1sgagreement, is <strong>in</strong>coherent:(81) a. Jobb szeretne csak Apuka menni.better would-like-3sg only Daddy go-<strong>in</strong>f`Daddy would like to go on his own'b.*Jobb szeretnék csak Apuka menni.better would-like-1sg only Daddy go-<strong>in</strong>fAs a reviewer po<strong>in</strong>ts out, this conforms to the proposed analysis, show<strong>in</strong>g the importance ofmatched agreement features.2.4.2 Inflected <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itivesHungarian has a narrower range of <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival complements than English, so not all examples thatmight come to the reader’s m<strong>in</strong>d can be tested. However, there is an important case to consider.Inflected <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itives <strong>in</strong> Portuguese take nom<strong>in</strong>ative subjects (Raposo 1987):

<strong>NYU</strong> Work<strong>in</strong>g Papers <strong>in</strong> L<strong>in</strong>guistics, Volume 2: Papers <strong>in</strong> Syntax, Spr<strong>in</strong>g 2009 20(82) Era importante [eles sairem].was important they leave-<strong>in</strong>f-3pl`It was important for them to leave’Hungarian has optionally <strong>in</strong>flected <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itives. The suspicion might arise that the nom<strong>in</strong>ativesubjects <strong>in</strong> Hungarian <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itives are related to phonetically overt or covert <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival <strong>in</strong>flection.But this is unlikely. Inflected <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itives <strong>in</strong> Hungarian occur only as complements of impersonalpredicates that do not carry person-number agreement and, as Tóth (2000) discusses <strong>in</strong> detail,they always have dative subjects:(83) Fontos volt / Sikerültimportant was / succeededa. ... délre elkészülni / elkészülnöm.by.noon be.ready-<strong>in</strong>f be.ready-<strong>in</strong>f-1sg`to be ready / for me to be ready by noon’b. ... nekem is délre elkészülni / elkészülnöm.dative.1sg too by.noon be.ready-<strong>in</strong>f be.ready-<strong>in</strong>f-1sg`for me too to be ready by noon’c. ... az ebédnek délre elkészülni / elkészülnie.the lunch.dative by.noon be.ready-<strong>in</strong>f be.ready-<strong>in</strong>f-3sg`for the lunch to be ready by noon’(Example (83b) is ambiguous: the dative DP `for me’ could be either the experiencer of thematrix predicate or the subject of the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itive. In (83c) the dative DP `for the lunch’ cannot bean experiencer, only the subject of `to be ready by noon’.)Tóth’s observations are important, because they show a crucial difference betweenHungarian and Portuguese <strong>in</strong>flected <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itives. Even if <strong>in</strong>flected <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itives do license overtnom<strong>in</strong>atives <strong>in</strong> Portuguese and <strong>in</strong> other languages, <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival <strong>in</strong>flection cannot be the universalprecondition for the existence of overt nom<strong>in</strong>ative subjects <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itives. This supports theconclusion that the critical factor is agreement with a f<strong>in</strong>ite verb.When the control or rais<strong>in</strong>g verb itself is an <strong>in</strong>flected <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itive, its own <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itivalcomplement cannot have an overt nom<strong>in</strong>ative subject. The presence of a dative DP `for me’would not make a difference:(84) *Fontos volt [akarnom [én is jó jegyeket kapni]].important was want.<strong>in</strong>f.1sg I.nom too good grades.acc get.<strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>tended: `It was important for me to want that I too get good grades’(85) *Fontos volt [nem elkezdenem [én is rossz jegyeket kapni]].important was not beg<strong>in</strong>.<strong>in</strong>f.1sg I.nom too bad grades.acc get.<strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>tended: `It was important for me not to beg<strong>in</strong> to get bad grades too’This confirms that the verbal agreement be of the k<strong>in</strong>d that normally licenses nom<strong>in</strong>ativesubjects; we have seen above that agreement on <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itives never do that.The f<strong>in</strong>ite clause whose verb agrees with the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival subject need not be subjacent tothat <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival clause. In (86) the <strong>in</strong>terven<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itives akarni `want-<strong>in</strong>f’ and elkezdeni `beg<strong>in</strong>-

<strong>NYU</strong> Work<strong>in</strong>g Papers <strong>in</strong> L<strong>in</strong>guistics, Volume 2: Papers <strong>in</strong> Syntax, Spr<strong>in</strong>g 2009 21<strong>in</strong>f’ do not carry <strong>in</strong>flection, although they could agree with én if they were f<strong>in</strong>ite.(86) Nem fogok akarni elkezdeni [én is rossz jegyeket kapni].not will-1sg want-<strong>in</strong>f beg<strong>in</strong>-<strong>in</strong>f I -nom too bad grades-acc get-<strong>in</strong>f`I will not want to beg<strong>in</strong> [to get bad grades too]’2.4.3 One f<strong>in</strong>ite verb, multiple overt subjectsThe examples discussed so far conta<strong>in</strong>ed only one overt subject, either <strong>in</strong> the f<strong>in</strong>ite or <strong>in</strong> an<strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival clause. The examples were natural, because Hungarian is an Italian-type null subjectlanguage: unstressed subject pronouns are not pronounced. But notice that pro subjects occur <strong>in</strong>the same environments as overt subjects. Therefore not only the overt <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival subject but alsothe null f<strong>in</strong>ite subject must agree with the f<strong>in</strong>ite verb. In other words, our control constructionsrequire multiple agreement. The availability of multiple agreement is the default assumption <strong>in</strong>M<strong>in</strong>imalism. Support for this analysis comes from the fact that it is perfectly possible formultiple overt subjects to co-occur with a s<strong>in</strong>gle agree<strong>in</strong>g f<strong>in</strong>ite verb. The sentences belowrequire a contrastive context, but when it is available, they are entirely natural and <strong>in</strong>deed theonly way the express the <strong>in</strong>tended propositions. Imag<strong>in</strong>e a situation where a group of people,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g János, is faced with a crowded bus: some will certa<strong>in</strong>ly have to walk.(87) János nem akart [megpróbálni [csak ő menni busszal]]John not wanted.3sg try.<strong>in</strong>f only he go.<strong>in</strong>f bus.with`John didn’t want to try to be the only one who takes the bus’(88) Én se akarok [csak én menni busszal]I-neither want.1sg only I go.<strong>in</strong>f bus.with`Neither do I want to be the only one who takes the bus’(89) Senki nem akart [csak ő menni busszal]nobody not wanted.3sg only he/she go.<strong>in</strong>f bus.with`Nobody wanted to be the only one who takes the bus’(90) Nem akarok [én is megpróbálni [csak én menni busszal]]not want.1sg I too try.<strong>in</strong>f only I go.<strong>in</strong>f bus.with`I don’t want to be another person who tries to be the only one who takes the bus’The status of multiple overt subjects <strong>in</strong> rais<strong>in</strong>g constructions is not clear to me:(91) ?János elkezdett [csak ő kapni szerepeket.John began.3sg only he get.<strong>in</strong>f roles-acc]`It began to be the case that only John got roles’(92) ?* Nem fogok [én is elkezdeni [nem én kapni szerepeket]]not will.1sg I too beg<strong>in</strong>.<strong>in</strong>f not I get.<strong>in</strong>f roles-acc`It will not happen to me too that it beg<strong>in</strong>s to be the case that it is not me who getsroles’

<strong>NYU</strong> Work<strong>in</strong>g Papers <strong>in</strong> L<strong>in</strong>guistics, Volume 2: Papers <strong>in</strong> Syntax, Spr<strong>in</strong>g 2009 22Hungarian does not have overt expletives, and it is generally thought not to have phoneticallynull ones either. If this is correct then simple rais<strong>in</strong>g examples will not necessitate multipleagreement; only the overt <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival subject wants to agree with the f<strong>in</strong>ite verb.To summarize, this section has shown that overt nom<strong>in</strong>ative <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival subjects <strong>in</strong>Hungarian are strictly dependent on person-number agreement with the f<strong>in</strong>ite verb. Thisagreement is not only <strong>in</strong>-situ but it can skip <strong>in</strong>terven<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival clauses. It may also <strong>in</strong>volve as<strong>in</strong>gle <strong>in</strong>flection and multiple DPs.2.5 De se pronouns and controlThe most commonly recognized <strong>in</strong>terpretations of overt pronouns are the bound, coreferential,and free ones. But there is a f<strong>in</strong>er dist<strong>in</strong>ction between de re or de se read<strong>in</strong>gs. The coreferentialor bound <strong>in</strong>terpretations only pay attention to de re truth conditions. The de se read<strong>in</strong>g ariseswhen the antecedent is the subject of a propositional attitude verb and is “aware” that thecomplement proposition perta<strong>in</strong>s to him/herself. The follow<strong>in</strong>g example, modified from Maier(2006), highlights the de re—de se dist<strong>in</strong>ction. We tape the voices of different <strong>in</strong>dividuals, playthe tapes back to them, and ask them who on the tape sounds friendly. Now consider thefollow<strong>in</strong>g description of what happens:(93) John judged that only he sounded friendly. (where he=John)We are consider<strong>in</strong>g the case where he refers to John, i.e. the voice sample John picked out isJohn’s own. But John may or may not recognize that the voice sample is his own. The pla<strong>in</strong> de retruth conditions do not care about this dist<strong>in</strong>ction. But we may dist<strong>in</strong>guish the special case whereJohn is actually aware that the referent of he is identical to him, i.e. where he expresses anattitude towards himself (his own voice). This is the de se read<strong>in</strong>g.De se read<strong>in</strong>gs are relevant to us because, as Chierchia (1989) observed, <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival controlconstructions are always de se. There is no way to construe (94) with John hav<strong>in</strong>g the desire butnot be<strong>in</strong>g aware that it perta<strong>in</strong>s to him himself; (95) on the other hand can be so construed. Asthe standard demonstration goes, John may be an amnesiac war hero, who is not aware that themeritorious person he nom<strong>in</strong>ates for a medal is himself. In this situation (95) can be true but (94)is false.(94) John wanted to get a medal. (only de se)(95) John wanted only him to get a medal. (de re or de se)Both de re and de se read<strong>in</strong>gs occur with quantificational antecedents as well:(96) Every guy wanted to get a medal. (only de se)(97) Every guy wanted only him to get a medal. (de re or de se)The standard assumption is that coreferential/bound pronouns <strong>in</strong> propositional attitudecontexts are ambiguous between de re and de se; only controlled PRO is designated as a de seanaphor. This view is <strong>in</strong>itially confirmed by the <strong>in</strong>terpretation of those subjunctives that areexempt from obviation, i.e. where they can be bound by the matrix subject.In Hungarian, subjunctive complements of volitional verbs are exempt from obviation <strong>in</strong> at

<strong>NYU</strong> Work<strong>in</strong>g Papers <strong>in</strong> L<strong>in</strong>guistics, Volume 2: Papers <strong>in</strong> Syntax, Spr<strong>in</strong>g 2009 23least two cases (Farkas 1992). One is where the matrix subject does not bear a responsibilityrelation to the event <strong>in</strong> the complement proposition. For Farkas (1992), responsibility is thehallmark of canonical control.(98) Miért tanul Péter olyan sokat?Nem akarja, hogy pro rossz jegyet kapjon.not want.3sg that pro bad grade-acc get.subj.3sg`Why does Peter study so hard? He doesn’t want that he get a bad grade’The person who gets the grade does not bear full responsibility for what grade he/she gets, s<strong>in</strong>cesomeone else assigns the grade. The subjunctive <strong>in</strong> (98) has a null subject, but it could be madeovert if it bears stress. If such pronouns bear stress, even the non-agentive predicate <strong>in</strong> thecomplement is not necessary. I believe the reason is that the responsibility relation is necessarilyimpaired. One may be fully responsible for whether he/she takes the bus, but not for whetherhe/she is the only one to do so:(99) Nem akarja, hogy ő is rossz jegyet kapjon.`He doesn’t want that he too get a bad grade’(100) Nem akarta, hogy csak ő menjen busszal.` He didn’t want that only he take the bus’It is important to observe now that the coreferential/bound non-obviative overt subject ofthe subjunctive <strong>in</strong> Hungarian can be <strong>in</strong>terpreted either de re or de se. E.g.,(101) A(z amnéziás) hős nem akarta, hogy csak ő kapjon érdemrendet.the amnesiac hero not wanted.3sg that only he get-subj-3sg medal-acc`The (amnesiac) hero did not want that only he get a medal’de re or de seThis contrasts sharply with the <strong>in</strong>terpretation of the overt <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival subject of controlcomplements, as observed by Márta Abrusán, p.c.:(102) A(z amnéziás) hős nem akart csak ő kapni érdemrendet.the amnesiac hero not wanted.3sg only he get-<strong>in</strong>f medal-acc`The (amnesiac) hero did not want it to be the case that only he gets a medal’only de seThe <strong>in</strong>terpretation of (102) differs from that of the run-of-the-mill control construction (103) just<strong>in</strong> what the operator csak `only’ attached to the subject contributes.(103) A(z amnéziás) hős nem akart PRO érdemrendet kapni.the amnesiac hero not wanted.3sg medal-acc get-<strong>in</strong>f`The (amnesiac) hero did not want to get a medal’only de se

<strong>NYU</strong> Work<strong>in</strong>g Papers <strong>in</strong> L<strong>in</strong>guistics, Volume 2: Papers <strong>in</strong> Syntax, Spr<strong>in</strong>g 2009 24The same observations hold for all the other Hungarian control verbs, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g utál `hate’,elfelejt `forget’, etc. So,(104) Abrusán’s Observation About De Se PronounsThe overt pronoun <strong>in</strong> the subject position of <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival control complements is<strong>in</strong>terpreted exclusively de se.The standard assumption is that the de se <strong>in</strong>terpretation of PRO is a matter of the lexicalsemantics of PRO. What we see, however, is that an obligatorily controlled <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival subject isalways <strong>in</strong>terpreted de se, irrespective of whether it is null (PRO) or an overt pronoun. There aretwo possibilities now. One is that our overt pronouns are simply phonetically realized <strong>in</strong>stancesof PRO, the de se anaphor. The other is that de se <strong>in</strong>terpretation is forced on any pronom<strong>in</strong>al bythe semantics of the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival control relation. This latter position seems preferable.Descriptively, it fits better with the fact that <strong>in</strong> other, non-control propositional attitude contextsthe overt pronouns are optionally <strong>in</strong>terpreted de re or de se, and that non-de se PRO is perfectlypossible <strong>in</strong> non-controlled contexts (viz., arbitrary PRO). This position also holds out the hopethat once the semantics of <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival control is better explicated, the obligator<strong>in</strong>ess of the de seread<strong>in</strong>g is expla<strong>in</strong>ed. The lexical de se anaphor proposal would simply stipulate that controlconstructions only accept lexical de se anaphors as subjects.Languages differ <strong>in</strong> exactly what exemptions from obviation they allow <strong>in</strong> subjunctives,but the de se <strong>in</strong>terpretation of overt <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival control subjects is a diagnostic to look for whenone wishes to ascerta<strong>in</strong> whether a language exhibits the same phenomenon as Hungarian.3. Other languages that may have overt <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival subjects<strong>in</strong> both control and rais<strong>in</strong>g: Italian, Mexican Spanish,Brazilian Portuguese, Modern Hebrew, Romanian, andTurkishWith this background I turn to the discussion of data from other languages. I will be assum<strong>in</strong>gthat the reader has read the more detailed discussion perta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g to Hungarian.3.1 Italian (thanks to Raffaella Bernardi, Ivano Caponigro, and especially Andrea Cattaneofor data and discussion)3.1.1 ControlItalian is a good language to start with, because for many speakers certa<strong>in</strong> word ordersdisambiguate the relevant read<strong>in</strong>gs. We start with control. Negation is <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the first set ofexamples just <strong>in</strong> order to make the truth conditional differences sharper. The overt subject ishighlighted by underl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g; this does not <strong>in</strong>dicate stress.In (105), preverbal solo lui takes maximal scope: it scopes over both negation and theattitude verb `want’. In (106), sentence f<strong>in</strong>al solo lui is ambiguous. On what I call the HI read<strong>in</strong>git takes matrix scope, though this is not identical to the one observed <strong>in</strong> (105), because it rema<strong>in</strong>swith<strong>in</strong> the scope of negation. What we are really <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> is the LO read<strong>in</strong>g (under bothnegation and the attitude verb).