DRC PIN Urban Poverty Report

DRC PIN Urban Poverty Report

DRC PIN Urban Poverty Report

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

ACRONYMSACF.....................Action Contre la FaimAREU...................Afghanistan Research and Evaluation UnitARTF...................Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust FundCS.......................Case StudyCSI......................Coping Strategy IndexCSO.....................Central Statistics OrganisationDDS.....................Dietary Diversity Score<strong>DRC</strong>.....................Danish Refugee CouncilFAO.....................Food and Agriculture OrganisationFCS.....................Food Consumption ScoreFGD.....................Focus Group DiscussionHFIAS..................Household Food Insecurity Access ScaleIDLG....................Independent Directorate for Local GovernanceIDP.......................Internally Displaced PersonIFPRI...................International Food Policy Research InstituteJICA....................Japanese International Cooperation AgencyGDMA..................General Directorate for Municipal AffairsGiZ.......................Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale ZusammenarbeitKII........................Key Informant InterviewKIS.......................Kabul Informal SettlementKSP.....................Kabul Solidarity ProgrammeKURP...................Kabul <strong>Urban</strong> Reconstruction ProgrammeLRRD...................Linking Relief, Rehabilitation and DevelopmentMICS...................Multi-Indicator Cluster SurveyMOLSAMD..........Ministry of Labour, Social Affairs, Martyrs and DisabledMoPH..................Ministry of Public HealthMoRR..................Ministry of Refugees and RepatriationMRRD..................Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and DevelopmentMUDA..................Ministry of <strong>Urban</strong> Development AffairsNGO.....................Non-Government OrganisationNNS.....................National Nutrition SurveyNSP.....................National Solidarity ProgrammeNRVA...................National Risk and Vulnerability Assessment<strong>PIN</strong>......................People in NeedPSU.....................Primary Sampling UnitUNHCR................United Nation High Commissioner for RefugeesUNODC................United Nation Office on Drugs and CrimeVAM.....................Vulnerability Analysis and MappingWASH..................Water, Sanitation, HygieneWB.......................World BankWFP.....................World Food ProgrammeWHH....................Welt Hunger HilfeExecutiveSummaryThis urban poverty study showsalarmingly high levels of poverty andfood insecurity and low levels ofresilience in the main Afghan cities.The urban poor are the first impactedby the slowdown of the Afghaneconomy and the political turmoil linkedto the presidential elections and arenow in distress.4 <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong>

esilience remain scarce in the city.The main interventions working onlivelihoods are small-scale, shorttermvocational training, of whichimpact remains limited given thepoor level of skills that beneficiariesusually reach, the lack oflinks to the market and the overallsaturated urban labour markets.Although a small number of actorstry to address issues of food securityand households’ resiliencein the city, the study showed thatbuilding resilience of urban householdsneeds long-term programmingon key issues that can bringactual transformation: education(especially for women), structuralimprovement of the business andproductive sectors, and social protectionmechanisms in particular.• Beyond the informal settlements,addressing widespread urbanpoverty – This study proved thatRecommendations for all stakeholdersurban poverty is widespread – andincreasing – beyond the limits ofthe few areas identified by nationaland international actors. In particular,households with specificprofiles and pockets of poverty areto be found everywhere in the cityand cannot be easily type-case byconvenient indicators and descriptors.Yet most of the assistanceis concentrated on a few smallsettlements: across the 5 cities,12% of non-residents of the KISreported having received assistance,compared to 30% for KISresidents.Addressing the poverty and resiliencegap in urban populationsshould be a priority for nationaland international stakeholders in acontext of growing urbanisation inthe country. This requires long-termand sustained interventions from bothnational and international actors.Build the resilience of urban households through a long-termcommitment to:Access to basic services: Bridge the gap betweencities in terms of access to basic services,as they play a key role in building resilience in thelong run. Community-based programming, basedon community contribution in cash and labourforce, is a sustainable way of improving andmaintaining basic services in the city and shouldbe further supported. Donors should maintaintheir focus on infrastructure investments, lookingat the gaps in other cities than Kabul, and especiallyfocusing on Kandahar, where the situation isconsiderably worse, especially when it comes toaccess to electricity.Access to education and literacy: This studyshowed that education is a determinant of householdresilience. It is also a safeguard againstinter-generational transmission of poverty. Yet,access to education is still unevenly distributedacross the 5 major cities and by gender: living inthe city does not guarantee access to education.Long-term commitment to education projects –especially those aimed at increasing girls’ accessto high school and higher education – should stillbe at the top of the agenda.Workforce qualification: Vulnerability and foodinsecurity in the cities are first and foremost aproblem of access to stable livelihoods. Structuralchanges are required for the urban workforce todiversify their skills and step away from casuallabour that keeps households in a circle of debtand poverty. Designing long-term programmesof qualification for urban skills – specialising inservices and business management in particular –would help reduce the increasing gap between theurban labour supply and demand.Recognize an urban geography of poverty by adjustingtargeting to the profiles of poverty in the cities:At the community level: The study has shownthat IDP households were particularly vulnerablebut that poverty and lack of resilience werewidespread beyond the limit of the informal settlementsidentified by the KIS Task Force, as peopleother than IDPs and IDPs living outside the KIS arealso vulnerable. The geographic scope of interventionsshould therefore increase beyond the KIS.Communities with a concentration of IDP households,especially those who have been recentlydisplaced,should be targeted as a priority, butprogramming should also focus on other vulnerablehouseholds whether from the host communityor with different migratory profiles.At the household level: Use fine targeting methodo-Address urban households’ difficulties in accessing food by:Building on existing female livelihoodstrategies: This study did observe forms oflivelihood accessible to women (albeit in a limitedscale). Usually home-based, they include tailoring,sewing, pistachio shelling, cleaning chickpeas,cleaning wool etc. These represent interestingopportunities for women to be economically active.Yet, the study shows that women’s weak positionin the labour market means that they work for extremelylow salaries. Organisations could work onbuilding the bargaining power of these women bysetting up cooperatives of production and playingan intermediary role in salary negotiations.logies: the Resilience Index: the study shows thatthere was little stratification amongst urbanpoor. Targeting is highly challenging and should bebased on a solid combination of indicators to avoidarbitrary delineation between poor groups. Oneoption is to opt for blanket targeting of hot spotsof poverty and food insecurity in urban areas.Another option – especially if resources arelimited – is to base targeting on a refined grid ofselection criteria. The study points at key variablesto identify the most vulnerable householdsin the city. A simplified resilience index (detailedin the recommendation section below) based onproxy means allows for a robust identification ofthe poorest. This system can be explained to communitiesto avoid resentment.Developing specific protection and livelihoodprogrammes for households with addictedmembers: The study shows that these householdsare at particular risk, as addicts often use anyincome or asset available to purchase drugs. Drugaddiction being stigmatised, these households losethe support of their communities, leaving childrenand women in a situation of high vulnerability. Addictionwas also a significant predictor for foodinsecurity. While drug addiction is increasing inAfghan cities, the response of national and internationalactors should be built up to prevent situationsof extreme vulnerability. Organisations like<strong>DRC</strong> with a specific focus on displaced populationsshould also take addiction into account in theirprogramming as drug use and associated risksare particularly high – and increasing – amongreturnees. The issue of addiction among returneehouseholds from Pakistan and Iran is a questionthat <strong>DRC</strong> should approach through a regionalstrategy, as drug use often starts in exile.Building long-term mechanisms of socialprotection: <strong>Urban</strong> households suffer from a lackof safety nets and the dissolution of communitybasedprotection mechanisms. Yet, this studyshowed that mechanisms of social protection –such as the pension distributed to the disabledand victims of mines – could have a real impact onfood security. Investing in sustainable systems ofsocial protection should therefore be a priority tofill the gap left by receding systems of communityand religious charity. In particular, the trainingof social workers embedded in the communitiesshould be a priority to identify households at particularrisk and improve the referral mechanisms– within and outside communities.10 <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong> 11

Tailor awareness raising campaigns and training to the gapidentified within households to increase food security andimprove nutritionTarget male members of households withtraining on food literacy: The study showedthat male members of households are in chargeof purchasing food in a large majority of urbanhouseholds. The poor diets of urban householdsalso show a low level of awareness about thebenefits of diversified diets. Men should thereforebe targeted as a priority by awareness-raisingcampaigns surrounding food. The study found thatfood budget was often the key determinant of foodchoices, meaning that training on food literacyshould include components on budget-managementand take into account the constraint of lowbudgets.Increase awareness raising about hygienepractices surrounding food, especially forwomen: The survey shows that levels of awarenessabout appropriate hygiene practices are stilllow amongst the urban poor, leading to increasedrisks of diarrhoea, especially for children. Specifictraining on hygiene requirements for food preparationshould be provided. This could be incorporatedinto entrepreneurial or social activitiesoffered for women – a class on food safety in mealpreparation for example. Community kitchens area good model to follow for this type of interventionsin urban settings.Raise awareness about the impact of teaconsumption during meal on iron absorption:Tea consumption during meal inhibit the absorptionof iron, an issue particularly problematicwhen no enhancing factors (fish, meat etc.) areconsumed as is the case for most Afghan households.Advocate for tea to be consumed betweenmeals instead of during the meal to address theproblem of iron deficiency, particularly for pregnantwomen, women and children.Significantly build up awareness raising onadequate breastfeeding practices: Breastfeedingpractices were found to be highly inadequateto provide for infants’ nutrition needs in thecities. A large effort of awareness-raising shouldtarget mothers but also female health workersworking on deliveries in public clinics for themto provide adequate information and care afterthe birth. At the community level, women centrescombined with EDC centres could be establishedwithin the communities as places where careand development services for young children areeasily available, along with training focusing onbreastfeeding.TABLE OF CONTENTSEXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................................................ 5INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................................15Background And Objectives Of The Study................................................................................. 15Research Objectives..................................................................................................................... 17Research Framework................................................................................................................... 17Structure Of The <strong>Report</strong>.............................................................................................................. 21METHODOLOGY......................................................................................................................................22Building A Resilience Score......................................................................................................... 22Geographic Scope......................................................................................................................... 23Quantitative Data.......................................................................................................................... 23Qualitative Data............................................................................................................................. 25Constraints And Limitations........................................................................................................ 272. VULNERABILITY AND FOOD INSECURITY: THE PLIGHT OF AFGHAN CITIES................................29A. <strong>Urban</strong> Profiling: Key Migratory Patterns.............................................................................. 31B. High Levels Of Vulnerability And Food Insecurity In The Cities......................................... 35C. Satisfying Levels Of Access To Basic Services................................................................... 473. DETERMINANTS OF FOOD INSECURITY AND LACK OF RESILIENCE................................. 52A. The Impact Of Migration & Displacement On Food Insecurity And Vulnerability............ 56B. Social Vulnerabilities: Key Drivers Of Food Insecurity And Lack Of Resilience.............. 61C. Education And Access To Services Limit Vulnerability....................................................... 71D. Food Availability: High At The Community Level, Low At The Household Level................ 73E. Food Utilisation: Problematic Hygiene Practices................................................................. 744. RESISTING TO SHOCKS: URBAN MECHANISMS OF RESILIENCE.............................................81A. Which Shocks Impact <strong>Urban</strong> Households?............................................................................ 83B. How Do The <strong>Urban</strong> Poor Resist Economic Shocks?............................................................ 855. CONCLUSION - PROGRAMMING FOR THE URBAN POOR...........................................................92Gaps In Existing <strong>Urban</strong> Programming........................................................................................ 94Recommendations.......................................................................................................................101ANNEXES..............................................................................................................................................114REFERENCES.......................................................................................................................................12412 <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong> 13

1IntroductionBackground and Objectivesof the Study“Even if the diversity of food available ishigher in urban areas, the rate of foodinsecurity is also higher. Because in the city,you have to pay for a lot of other things, notonly food items. Households have to pay fortheir rent, for electricity… So in terms of thequantity of food that households are able toaccess in the city, urban households areactually worse-off.”Pic. 1.1 Photo credit: Lalage SnowA new urbanity – definedas an urban lifestyle, withurban characteristicsand traits – is blooming inAfghanistan, supported byan estimated 5.7% annualurban growth rate since2001 1 . Still in majorityrural, the country is joiningthe global trend of urbanisationwith at least 30% ofthe population now livingin cities, 50% of which inKabul 2 . According to theWorld Bank, the urbanpopulation should represent40% of the Afghanpopulation by 2050 3 . Wheninsecurity plagues the restof the country, Afghanurban areas are oftenperceived as rare safehavens. Much of the country’sstability rests nowin the capacity of urbancentres to remain strongeconomic and social hubs.14 <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong> 15

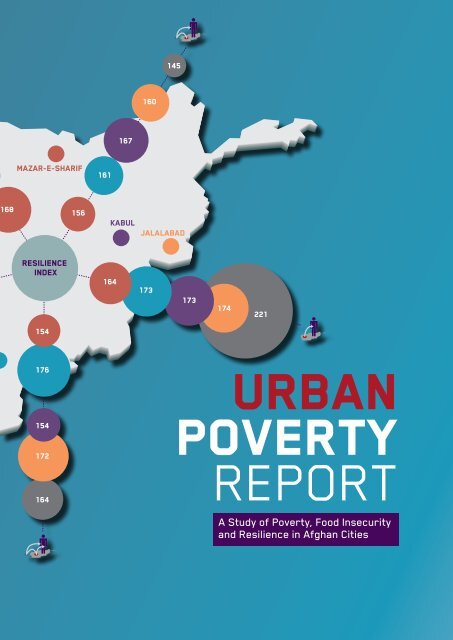

Afghanistan’s rapid urbanization is theresult of migration and displacement dynamics:rural to urban migration, economicmigration, significant conflict-induced internaldisplacement fuelled by high levels ofinsecurity, especially in the remote districts,and sudden displacements of populationdue to natural disasters such as drought,landslides and floods. Displacement trendsare on the rise as Afghanistan completesa full security and political transition, withvisible signs of instability and heightenedconflict directly impacting civilians. Afghan citiesare often perceived as better-off than ruralareas as they benefit from:• Security from conflict, which is on therise in most rural districts;• Prosperity in a country where poverty,un- and under-employment are prevalent;• Availability of basic services where accessto water, electricity and health isstill an everyday challenge in the majorityof provinces and many rural areas.A few urban centres are the recipients ofmost displacement patterns: Kabul firstand foremost, and the four other importantregional capitals: Herat and Mazar-e-Shariffor their booming economy; Kandahar andJalalabad as bastions of relative securityin provinces where insecurity in rural areasis increasing. Afghanistan counts todayover 6 million Afghan refugee returnees andapproximately 1 million internally displacedpersons – the majority of whom migrateto urban areas with little or no intentionto return home 4 . At a time of decreasingvoluntary returns to Afghanistan – 11,000refugees returning as of July 2014 (UN-HCR) – economic migrants and internallydisplaced persons (IDPs) now composemost of the influx of populations towardsthe cities today. The urban population profileis changing as a result.Afghan cities are at the intersection of twomajor dynamics: multiform migration tourban areas and economic drawdown thatpoint to urban poverty as one of the acutechallenges for Afghanistan in the comingyears. The urban challenge in 2014Afghanistan is three-fold:1. National and municipal authorities lackthe financial and technical capacitiesto manage displacement. The questionof unregulated urbanisation is increasinglyturning into a heated political issuein spite of recent legislative improvements.In particular, the IDP Policy supportedby the Ministry of Refugees andRepatriation (MoRR) and UNHCR, theInformal Settlement Upgrading policy,which should soon be finalised, and theNational Food Security Policy open theway for a more solid legal framework fornational authorities and international actorsto operate. Yet, urban poverty is stilla ‘black box’ for many actors operatingin Afghanistan 5 . In 2014, necessaryservices and infrastructure, social andlegal frameworks and non-governmentalsupport are not in place to tackle thischallenge.2. Informal settlements are burgeoningwith new groups settling in areas fallingoutside of out-dated municipal plans,making it difficult for municipalities toprovide adequate levels of services topeople living there. These informal settlementsare now a common feature ofAfghan cities and represent an estimated80% of the Kabul population and69% of its residential land 6 . While populationshave invested in these areasand develop them in some ways, theseincreasingly represent pockets of urbanpoverty. Strikingly, the latest 2011-2012National Risk and Vulnerability Assessment(NRVA) noted an increase in foodinsecurity between 2007 and 2011 inurban areas, reporting an augmentationfrom 28.3% of the urban population to34.4% in 2011-12 7 .3. <strong>Urban</strong> poverty is on the rise with worryingsigns of economic collapse inAfghanistan: national economic growthhas slowed down significantly under thecumulative effect of the withdrawal ofinternational military forces, reductionof international funding and reduction ofprivate investments due to the currentinstable political context 8 . Construction,transportation and services sectors thathad benefited from the internationalpresence are now in decline, discombobulatingthe dynamism of the urbaneconomy.Where is the data to inform policymakers?In the absence of a census, data are lackingto inform policies and programmes inurban areas. In a city like Kabul, assistanceand knowledge are concentrated on themain group that has been identified asneeding humanitarian assistance: InternallyDisplaced People (IDPs) within the KabulInformal Settlements (KIS) 9 . Outside theselittle is known about urban poverty. This iseven truer for many international organisationsand donors, which have focused effortson rural areas for the past decade andhave only recently turned their attention tothe challenges faced by Afghan cities.Research ObjectivesThe objectives of the study are three-fold:Building KnowledgeThe research providesevidence-based analysis onthe levels of food security,vulnerability and resilience ofthe Afghan urban population. Inparticular, it compares migrationgroups (host community,Internally Displaced Persons(IDPs), returnees and economicmigrant), across the fivemajor Afghan cities – Kabul,Herat, Jalalabad, Mazar-e-Sharif and Kandahar – andacross gender.Informing ProgrammingThe study provides actionablerecommendations for <strong>PIN</strong> and<strong>DRC</strong> to develop their urbanprogramming. In particular,both organisations plan ondeveloping urban livelihoodprojects, including urban agricultureprojects, and will userecommendations to informtargeting and implementationfor pilot programmes inMazar-e-Sharif, Herat andJalalabad.Precise data on levels of poverty,vulnerability or food security in the citiesare lacking, as is a precise identification ofvulnerable sub-groups, across gender, ageor migration history.On the other hand, a precise knowledge ofthe nature of resilience in the Afghan urbanpopulation is also lacking: what mechanismsprevent households and communitiesfrom starvation? What factors makesome households more resilient to shocksand instability than others? What strategies,if any, do individuals, householdsand communities build up to survive anddevelop in difficult environments?The present research was commissionedby the Danish Refugee Council (<strong>DRC</strong>) andPeople in Need (<strong>PIN</strong>) to fill this knowledgegap and uncover the nature, level andcomplexity of poverty, food security and resilienceamongst Afghan urban householdsand communities. <strong>DRC</strong> and <strong>PIN</strong> commissionedthis study in the framework of atwo-year project funded by the EuropeanUnion under its ‘Linking Relief, Rehabilitationand Development’ (LRRD) programme.AdvocacyThis research unlocks solutionsto the challenges ofurban poverty. It provides evidenceand recommendationsfor national and internationalactors on the strategic andprogrammatic adjustmentsneeded to better apprehendurban poverty and food insecurity.4. See Samuel Hall-NRC-IDMC-JIPS (2012), Challenges of IDP Protection – Research Study on the protection of internally displaced persons in Afghanistan. 5. Quote from aKey Informant Interview (KII) with an NGO-worker in Kabul. 6. World Bank (2005), ‘Why and how should Kabul upgrade its informal settlements’ in Kabul <strong>Urban</strong> Policy Notes,Series n.2, p.1. 7. Central Statistics Organisation, (2014), National Risk and Vulnerability Assessment 2011-12, Afghanistan Living Conditions Survey. Kabul, CSO, p. 51.8. World Bank (2013), Afghanistan Economic Update, p.3. Available at https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/16656/820120WP0WB0Af0Box0379855B00PUBLIC0.pdf 9. Kabul Informal Settlements (KIS) are 50 locations identified by the humanitarian community and the Ministry of Refugees and Repatriation (MoRR) for thedistribution of humanitarian assistance, especially in the winter. An official list is kept and updated by the KIS task force, gathering the main organisations working in these areas.16 <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong> 17

KEY RESEARCH QUESTIONS 4 PILLARS OF FOOD SECURITY 11What are the determinantsof food insecurityand vulnerability in urbanareas?Who are the urban poor? What is the impact of displacement,migration and return on poverty and food insecurity?<strong>Poverty</strong> LineProportion of food in total household expenditureFood Consumption ScoreHousehold Food Insecurity Access ScaleCoping Strategy IndexSources of income and type of employmentWhat is the level of access to basic services?Distance to nearest health facility and schoolWater systemElectricityWhat are the determinants of food insecurity?By migratory profilesRegression analysis of factors impacting vulnerabilityAVAILABILITY access use - utilisation stabilitySufficient quantities of foodavailable on a consistentbasisThe ability for household toproduce and or purchase thefood needed by all householdmembers to meet their dietaryrequirements and foodpreferences as well as the assetsand services necessaryto achieve and maintain anoptimal nutritional status.Based on knowledge ofbasic nutrition and care, aswell as adequate water andsanitation, each member ofthe household is able to getan intake of sufficient andsafe food adequate to eachindividual’s physiologicalrequirements. Additionally,an individual’s health statuscan affect her/his ability toabsorb or utilize nutrientsfrom food.1. Ecker, O & Breisinger, C (2012): The Food Security System, A new Conceptual Framework. IFPRI Discussion Paper.Food security can be a temporarystate as it depends onthe stability of supply and accessto food. This can be impactedby prices and weathervariability as well as politicaland economic shocks.How resilient are theurban poor and based onwhich mechanisms?How can programming bestaddress urban food insecurityand vulnerability?Research FrameworkMain Concepts and Definitions1. Themes and Indicators:Food Security, Vulnerabilityand ResilienceThis research was designed with thekey concepts of food security, vulnerabilityand resilience. With the reductionof poverty, hunger and malnutrition byhalf by 2015 as the first of the MillenniumDevelopment Goals (MDGs), resilienceis attracting more and more attention inthe humanitarian and development community.Yet its definition – and perhapsmore importantly, its practical applications– remain flimsy. In a country whererobust mechanisms linking humanitarianWhat is the level of resilience of the urban poor?How does it vary across migratory groups and gender?What specific shocks impact food security in urban areas?What are the ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ coping strategies householdsrely on in urban areas?Where are the gaps in the coverage of urban food insecurity?Which type of interventions would help building up the resilienceof urban poor?and development assistance are still beingdeveloped, words like resilience provide aconceptual transition beyond emergencyrelief, care and maintenance, to longerterm solutions.Key concepts used for this research aredefined as follows:Food Security‘Food Security exists when all people,at all times, have physical, social andeconomic access to sufficient, safe andnutritious food for a healthy and active life’(1996 World Food Summit). Food securityis necessary to maintain optimal nutritionalstatus, in terms of both caloric intakeand sufficient quality (variety and micronutrientintake) 10 . Practitioners further• The concept of resilience is complementarydefined the components of food securityrisks/hazards’ 13 vulnerability, using cut-off points adaptedduring the 2009 World Food Summit,which pointed at four main pillars necessaryto understand the factors underpinningfood security at the household level.Food insecurity, particularly in the longterm,to that of vulnerability: it is‘the ability of groups or communitiesto cope with external stresses and disturbancesas a result of social, politicaland environmental change 14 .has an impact on nutritional status(micronutrient deficiencies, stunting,wasting, etc.), which can in turn affectboth physical and mental health. Althoughfood insecurity largely stems from povertyor income inequality, it is not a necessaryresult of poverty. Additionally, food insecurityhas been identified among householdsclassified as non-poor. 12The concept of resilience provides a goodbasis to analyse households’ and communities’strategies to prevent and cope withcrises that may endanger their food security,as it draws a dynamic picture of foodsecurity, whereby components other thanaccess to food are taken into account.There is little consensus amongst stakeholderson how to measure resilience. TheVulnerability and Resilience:Both concepts of vulnerability and resilienceare useful as they offer a dynamicpresent study used the FAO-EU resiliencetool, which takes into account a largerange of factors affecting resilience:understanding of poverty. They proposea multi-faceted concept of poverty that • Social Safety Netsgoes beyond access to food and income • Access to Basic Servicesand takes into account dimensions such • Assetsas access to services or household’s • Income and Food Accessadaptability to shocks:• Adaptive Capacity 15• Vulnerability is ‘the degree to which asystem is susceptible to and unable tocope with adverse effects of specificIn order to collect comparable data, theresearch was based on existing standardindicators of food security, poverty and10. FAO, Food Insecurity Information for Action, Practical Guides, 2008. 11. Ecker, O & Breisinger, C (2012): The Food Security System, A new Conceptual Framework. IFPRI12. Nord, M., Andrews, M. & Carlson, S., 2005. Household Food Security in the United States, 2004, USDA Economic Research Service. Available at: http://www.ers.usda.gov/Publications/ERR11/ 13. IPCC, (2001) 14. Adger (2000), ‘Social and ecological resilience: are they related?’ in Progress in Human Geography, 24:347. 15. EU-FAO, ‘MeasuringResilience : A Concept Note on the Resilience Tool’. in Food Security Information for Decision-Making – Concept Note18 <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong> 19

to the Afghan context. A resilience scorewas also calculated taking into accountthe five main dimensions of resiliencementioned above and using context-specificcut-off points for each indicators. Theresearch team developed the resiliencescore based on the FAO-EU model anddrawing upon a similar system developedby People in Need in Mazar-e-Sharif forease of comparison 16 .Each component o f household resilienceis assessed through a series of indicatorsto generate a composite index ofhousehold resilience. “This index gives anoverall quantitative “resilience score” thatclearly shows where investments needs tobe made to further build resilience” 172. Target Groups:Comparing MigrationGroupsThe research is based on the comparisonof levels of resilience across four key migratorygroups: returnees, IDPs, economicmigrants and host community, usingstandard definitions for each of them:Concept Definition SourceStructure of the <strong>Report</strong>The report will be structured as follows:• Chapter 1: Introduction and Methodology– introduces the research context,the objectives of the study andthe analytical framework it was basedupon. It gives a detailed overview ofthe methodology used for the study.• Chapter 2: <strong>Urban</strong> Profiling – focuseson assessing levels of food insecurityand vulnerability in the 5 targeted citiesand across groups under scrutiny.• Chapter 4: Resilience of the <strong>Urban</strong>Poor – looks at coping mechanismsand analyse resilience amongst theurban poor.• Chapter 5: Recommendations forAction – will analyse existing programminggaps and suggest recommendationsfor <strong>PIN</strong> and <strong>DRC</strong> as well as forother stakeholders.Internallydisplacedpersons“Persons or groups of persons who have been forced or obliged toflee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, in particularas a result of or in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict,situations of generalised violence, violations of human rightsor natural or human-made disasters, and who have not crossed aninternationally recognised State border.” IDPs are considered to bein displacement until they are able to find a durable solution. The UNrecognises three main durable solutions: return to the place of origin,local integration or re-settlementUN Guiding Principles onInternal Displacement(as cited in “Challengesof IDP Protection”• Chapter 3: Determinants of <strong>Urban</strong><strong>Poverty</strong> – analyses the main determinantsof vulnerability and foodinsecurity and looks at the four pillarsdetailed above.RefugeesAny person who “owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted forreason of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular socialgroup or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality andis unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protectionof that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outsidethe country of his former habitual residence as a result of suchevents, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it. ”1967 Protocol relating tothe Status of RefugeesReturneesThose who have gone through the process of return, “the act orprocess of going back.” In this study, the term refers to returnedrefugees. Returnees are considered as such until they are fully ‘reintegrated’in their society of origin. Reintegration can be defined as“a process that should result in the disappearance of differences inlegal rights and duties between returnees and their compatriots andthe equal access of returnees to services, and opportunities “2013 UNHCR StatisticalOnline PopulationDatabase2004 UNHCR Handbookfor Repatriation and ReintegrationActivities, p.5EconomicMigrantsThose who choose to move in order to improve their lives and livingconditions, internationally or within a country. Economic migrants aretreated very differently under international law.UNHCR Refugee Protectionand Mixed MigrationHostCommunityA community that has IDP, returnee or migrant households livingamongst non-migrant householdsAdapted from UNHCR:IDPS in Host Families andHost communities.16. See Annex.2 for detailed breakdown of the resilience score per indicator. 17. Ibid, p.1.20 <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong> 21

MethodologyTargeted Cities - Quantitative SurveyBuilding a Resilience ScoreThis research was designed to providerepresentative data of both the urbanpopulation of the five main Afghan citiesand the main migration groups living inthese cities. Based on a series of quantitativeand qualitative tools, the methodologyoffers opportunities to triangulateinformation through a household survey,a community survey and qualitative data.Quantitative tools were designed usingstandard indicators in use in the country tocreate a robust index of urban resilience.These key variables were combined tocreate a resilience score based on cut-offpoints adapted to the Afghan context. Thedetail of the resilience score is available inAnnex.KEY INDICATORS OF FOOD SECURITY AND POVERTYFood SecurityVulnerabilityEarly Child DevelopmentQuantitative Component of the ResearchSurvey of 5,411 householdsSurvey of 149 communities• Food Consumption Score (FCS): a proxy indicator measuringcaloric intake and diet quality at the household level based onthe past 7 days food consumption recall for the household.• Household Dietary Diversity Score (HDDS)• Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS), which isbased on the perception of households of their level of foodsecurity and the usual responses that household would giveto a situation of food insecurity 18 .• Coping Strategy Index (CSI)• Per capita consumption to compare household based on the2011-2012 official poverty line of 1,710 AFN per person permonth• Monthly Income• % of food in total household expenditure• Dependency Ratio• Household Asset• Debt and Savings• Access to basic services• Access to assistance• Literacy and Education• Initiation of Breastfeeding• Exclusive breastfeeding18. Coates, J, Swindale, A and Bilinsky, P (2007), Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for measurement of household food access: Indicator guide v3. Washington,DC: FHI 360/FANTA.Qualitative Component of the Research45 Focus Group Discussions28 Case Studies42 Key Informant InterviewsGeographic ScopeResearch and data collection were conductedover the months of May and June2014 in five major Afghan cities: Kabul,Herat, Jalalabad, Mazar-e-Sharif, Kandahar.These cities were selected for thestudy because they represent the mainurban hubs of the country and allow theresearch to have a wide geographic span,covering five of the main regions of thecountry. These cities are also of specialinterest for <strong>PIN</strong> and <strong>DRC</strong>’s programmingQuantitative DataHousehold Survey (5,410)Questionnaire – The household surveywas based on a questionnaire of 94closed questions. The questionnaire wasdeveloped so as to comprise the migrationprofile of households, and the mainstandard indicators to measure povertyand food security of households, indicatorsof hygiene and breastfeedingpractices as well as key socio-economicindicators. A rapid overview of the keyfood security and poverty indicators usedfor the study is provided in annex.Sampling – The household survey includedfour main categories of respondents ineach city: local residents, returnees, IDPsand economic migrants. The sample sizeaimed at capturing 270 respondents percategory for a total of 1,080 respondentsper city and 5,400 respondents in total.This sample size gives us representativedata at the city level with a statistical rigorof 5% of margin of error and 95% confidencelevel.Within each city, the sampling was basedon a grid approach, to allow for a comprehensivecoverage of the cities. Inorder to include informal settlements inthe study, cities were not defined basedon their administrative boundaries but ontheir physical characteristics: cities wheredefined as spaces with a continuum ofdense residential areas. Each city was dividedinto Primary Sampling Units (PSUs)based on a grid approach. A total of 30to 34 PSUs were defined per city so as toensure a geographic mapping that coversvarious socio-economic categories acrosseach part of the cities, including informalsettlements. The field teams cover 30 to34 PSUs in 10 days in each city based onthe following sampling strategy:22 <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong> 23

• to avoid bias and to respect culturalconventions, FGDs were conductedwith groups of male and groups of femalerespondents separately. Groupsof 5 to 7 respondents were gatheredfor each FGD. In each city, to theextent possible, a same number ofFGDs were conducted with men andwith women. FGD were moderatedby national consultants and based onstructured guidelines covering variousaspects of intra-households issuesrelated to poverty and food security,including access to livelihoods,seasonality, purchasing habits andhygiene practices.Qualitative Data CollectionTable 1.3• Case Studies (25) – Case studiesaimed at capturing the experience andspecific challenges faced by vulnerablemembers of the communities,including female-headed households,widows, elderly heading householdsand families with disabled or addictedmembers. Case studies were conductedthrough a one-to-one in-depthinterview based on a series of openquestions.• Key Informant Interviews (42) – Aseries of KIIs was conducted at thenational and city level in order to getperspective from practitioners and keystakeholders on the issue of food securityand urban poverty. KIIs targeteddonors, Non-Governmental Organisations(NGOs) operating in urbanenvironment, UN agencies workingon related issues and governmentalactors (at the ministerial and municipallevel). Key informant interviews lastedapproximately one hour and wereconducted based on semi-structuredguidelines and adjusted to each kindof respondents, based on their area ofexpertise to collect the most relevantdata from each of them.The following table summarises qualitativedata collected for this research:Constraints and LimitationsImpact of Afghan Presidential Elections– Most of the fieldwork for this study wasconducted during the presidential electionsin Afghanistan. This had an effect onboth:• The sample, as teams were not ableto reach their targets in Jalalabad andHerat because of the second roundand as a tense security context forcedteams to be cautious and avoid certainareas in the city;• The findings, as elections have had abrutal effect on the Afghan economy,stopping investments and reducingdemand for daily labour significantlyin the months before the elections.The elections have had a negativeimpact on the livelihoods, income andfood security of the urban poor. Theresults of the present study are likelyto have been impacted by this difficulteconomic environment and this studyrepresents a snapshot of the difficultsituation mid-2014.Exclusion Bias of the wealthiest areas– The wealthiest areas of cities are difficultto survey because it raises importantsecurity issues for the field teams, as theyare composed of highly secured compounds,often protected by armed guardsand checkpoints. They have not been includedin the sample 20 . There is thereforean exclusion bias of the wealthiest areasof the cities and a focus on middle classand poor areas of each city. Yet, the gridapproach did allow for a large geographiccoverage of urban areas.Complex identification of migration patterns– Most Afghan households are characterisedby complex migration history,a complexity that can hardly be capturedby a quantitative survey. In particular,causes and motivations to move are morecomplex that the dichotomy betweeneconomic migrant and internally displacedhouseholds, leading to difficulties in theidentification of these groups. Often,households have moved in response toa combination of intricate factors. Forthe purpose of this research, team leaderswith years of experience of workingon migration-related issues trained enumeratorsspecifically for them to be ableto go round the problem of identificationthrough follow-up questions to respondentsbut categories of IDPs and economicmigrants must not be considered aswatertight, as they overlap very often inpractice.Impact of seasonality on findings – Thesurvey was conducted in May and June,i.e. is in the post-harvest period for all thefive cities. This is considered as the bestperiod in terms of food security. Yet, asshown in the research below, the impactof seasonality on urban markets andaccess to food for urban households islimited as households’ livelihoods are nottied to agriculture and food supply in thecity is not largely reduced. The impact ofseasonality on the findings is thereforelimited.Challenges with data collection in Kandahar– Kandahar appeared as an outlieron some food security indicators, possiblythe result of a different understanding ofthe question by enumerators using Pashto.A series of call backs was organisedto check and triangulate the data. Thistriangulation showed a difference in theresults found for the Food ConsumptionScore as the second round of data collectionfound a FCS more in line with the profileof the city and of other urban centres.The findings from this triangulation wereintegrated in section 2.Overview of Qualitative Data Collection26 <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong> 27

lower proportion of IDPs in Herat (13%) issurprising given how heated the issue ofinternal displacement is for the capital ofthe Western region. This low result can beexplained by several factors, including thefact that Herat counts important settlementsof protracted IDPs outside the limitof the city, such as Maslakh, and that theIDP settlements inside the city (Minaret orKareezak for example were surveyed lateron during the data collection, hence notincluded in the random sample on whichthese results are based). Still, the lowerproportion of IDPs in Herat shows that theproportion of IDPs spread out in the city isperhaps lower than stakeholders considersit to be. In the mix of factors that leadhouseholds to live their place of origin tosettle to the city of Herat, a lot of themrank economic necessity first.Displaced households moving to Afghanistan’surban centres stem almostexclusively from rural areas. While Mazare-Sharifand Kabul attract substantialnumbers of arrivals from other provinces,apparently as hubs of work opportunities,migration to the other cities stemsin majority from rural areas in the sameprovince. Rural backgrounds mean thatdisplaced households settle in the cityInternal Displacement and its reasonsFigure 2-1unprepared to the specificities of life inthe city, in particular in terms of economicopportunities, making integration in urbansocio-economic structures more difficult.Conflict fuelling internaldisplacementInternal displacement is first and foremosta consequence of conflict andpersecution. Yet, Mazar-e-Sharif countsa higher proportion of natural-disasterinduced IDPs, a fact that can be explainedby the recurring droughts that touch theNorthern and Central regions, pushingpeople to abandon their place of origin tomove to Mazar-e-Sharif (figur 2-1).The bulk of city inhabitants arrived in thecity they currently live in more than threeyears ago as reported by 76% (±2%) ofrandomly-selected respondents. Lookingspecifically at IDPs shows that a largepart of this population has now enteredprotracted displacement with 28% of theIDPs who set up more than three yearsago having moved to the city between 5and 10 years ago and 37% between 11and 20 years ago. The impact of the timein displacement on poverty is analysedfurther in section 3.15098157132630% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%Why did you move to this city?Figure 2-2Pull Factors - Why did you move to this city?‘We don’t haveparticular relationswith thePashtun of ourcommunity becausewe don’tspeak the samelanguage. Butthey live theirlives, we live oursand we do nothave any problemswith oneanother.’FGD Women, Herat, Naw Abad<strong>Urban</strong> Assistance Programmesare not a pull factorIt is important to note that the existenceof assistance programme onlyseems to play a very marginal rolein the decision-making of uprootedpopulations. Given the scarcity ofassistance programme targetingurban population as a whole, it isunlikely that assistance is an importantfactor. This is an importantfinding given the debate on urbanassistance fuelling more displacement,especially when it comesto the Kabul Informal Settlements(KIS). This study goes against thiscommon assumption that urbanprogrammes of assistance will encouragefurther displacement andmigration, as other much strongerfactors determine the choice ofhouseholds to move to the fivebiggest Afghan cities.Social integration in the city:The importance of socialnetworksAfghan urban centres are attractivehubs as they are perceived asoffering what remote rural areascannot – or cannot anymore – offerrural populations: job opportunities,safety and basic services. Evenwhen urban labour markets aresaturated and basic services overstretched,it is the “myth of the city”that bring people to the cities: figure2.3 (below) shows that the existenceof work opportunities in the cities(50.5%), security in urban areas(39.7%) and the existence of existingnetworks (24.3%) are the threemain pull factors determining thechoice of destination for displacedand returnee populations. The existenceof social networks is fundamentalin influencing the choice oftheir destination, confirming pastresearch 22 . Indeed, as relatives areone of the primary sources of supportand potential assistance, theirpresence in the city is crucial fornewly-arrived households. Qualitativedata showed that most householdswere satisfied about theirmove to the city and did not faceparticular challenges integrating.In particular, only very rarely intercommunitytensions were reported.Patterns of residency varied significantlylocation by location and donot allow to conclude on a certaintrend: certain areas see householdsfrom different ethnic groups andInternal Displacement and its reasons (n= 741)22. Harpviken, Kristian Berg (2009) Social Networks and Migration in Wartime Afghanistan. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.32 <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong> 33

Food consumption score (FSC)Food consumption score by cityFigure 2-8Figure 2-9Food Consumption Score (Random Sample)On the food expenditure scale, Mazar-e-Sharif displays particularly alarming levelswith over half of its urban poor (55% ±4%) dedicating more than 60% of theirtotal household spending to the purchaseof food. On the whole, two out of five ofthe surveyed households fit this criterion.The Food Security and AgricultureCluster (FSAC), which conducted a foodsecurity survey in 2013 with a large ruralcomponent, had found 28% of householdsconsidered to have a poor accessto food) 30 . As the FSAC Assessment waslargely conducted in the post-harvestseason, it is likely that rural householdswould spend less of their total expenditureon food. Still, except in Mazar-e-Sharif, amajority of urban households spend morethan half their budget on non-food items,indicating a certain diversity of expenditures.Qualitative fieldwork suggests thatrent, electricity, transportation and healthexpenses are also important in the budgetof urban households.Uncertain food security in urbanareasFindings on food security largely corroborateindicators of poverty, drawinga rather bleak picture. <strong>Urban</strong> areas arecharacterised by high levels of food insecurityacross the board, despite notablevariations across cities. The followingsection examines these variations in thequality of urban diets and access to foodof households amongst the urban population.Food Consumption ScoreAccording to the Food ConsumptionScore (FCS), which weighs the differenttypes of food consumed during the previousweek, 20% (±2%) of urban Afghanssuffer from poor food consumption, whilea further third are borderline, leaving lessthan half with acceptable levels of consumption,despite the fact that the surveywas conducted post-harvest.Categories were defined based on theclassification established by the FSACwith a FCS below 28 considered to bepoor, between 28.1 and 42 borderline andabove 42 acceptable 31 as shown in figure 2-8.While worrying, these figures indicate aslightly higher level of food security inthe biggest Afghan cities than in the restof the country, if compared to the findingsof the NRVA. The latter found 34.4%of urban households to be food insecurealthough NRVA’s calculation is based oncalorie intake 32 . If broken down by city, thesurvey found significant differences: thefood consumption score which measurescaloric intake and the quality of diet at ahousehold level yields surprisingly positiveresults for the city of Kandahar, with 80%Food consumption score by city(± 4%) of inhabitants enjoying acceptablefood consumption. Conversely, only 30%to 50% of those surveyed in other citiescould claim this status. Mazar-e-Sharifand Herat present the higher proportionsof households with poor food consumptionwith respectively 31% and 25% ofhouseholds reporting poor levels of foodconsumption in both these cities.Given the fact that Kandahar representedan outlier on this indicator, a secondround of data collection was organisedto check and triangulate the data on foodconsumption in the Southern city. Thesecond set of data was collected basedon a random selection of households fromthe first survey. The data was collectedthree months later and in different conditions,hence is not directly comparable,but provides a robust basis to triangulatethe FCS in Kandahar 33 .The second round of data collection inKandahar suggests a profile of the population’sfood consumption more alignedwith the four other cities, as shown infigure -2-10.According to this smaller sample, 47%of households enjoyed acceptable foodFSC in KandaharFigure 2-10FSC in Kandahar – Second data collectionconsumption, 29% of them were borderlineand 24% had poor food consumption.This still puts Kandahar at the topof the 5 cities in terms of the proportionof households reaching acceptable foodconsumption, alongside Jalalabad. On theother hand, it does point at a significantissue of food security in the city given theproportion of households having poor orborderline food consumption.Given the high level of food insecurityfound by this study in Kandahar, andgiven the profile of the four other cities interms of food consumption, policy makersshould not over-estimate Kandahar’s30. Ibid. 31. Ibid, p.36 32. NRVA 2011-12, p. 53.33. 246 households were randomly selected from the first sample and were asked the same questions on food consumption than during the first survey.38 <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong> 39

Dietary Diversity per cityTable 2-1:Dietary Diversity per city. Numbers represent the average number of days per week that each food group is consumed.Dietary diversity was also measuredthrough the household dietary diversityscore (HDDS) recording all the food consumedby a household over the past 24hours per food groups.These various indicators of dietary diversityshow:• The poverty of urban diets ingeneral, as cereals (usually bread)remain the basis of urban poor’sdiets. Eating meat, fruit, or dairyproducts remain relatively rare evenfor urban households. This wasconfirmed by the qualitative data,which showed that meat was usuallyconsumed once a week in the bestcases to once a month in general.Eggs were a more common sourceof protein. Most households reportedeating bread and vegetables,accompanied by tea, for the threemeals of the day. Tea consumptionat mealtime inhibits iron absorption,limiting utilization of nutrients, a keyaspect of food security. Fruits werealso often considered to be too expensivefor households’ budgets.• Compared to the national figuresfound by the NRVA, the general dietarydiversity has decreased amongurban households, a likely consequenceof a decrease in purchasingpower since 2011. For example, theNRVA found an average of 2.6 daysof protein consumption per weeknationally and 3.3 days per week inurban areas35. This survey found amaximum of 1.88 days of consumptionof proteins per week identifiedamong the population in Kandahar.While the consumption of sugar andoil is equivalent to that found in theNRVA, the consumption of tubers,dairy products and fruit is lessimportant amongst the householdssurveyed for this study. The onlypositive finding is the fact that theconsumption of vegetables is significantlyhigher among urban householdsthan recorded in the NRVAranging from 3.1 days on average inHerat to 5.38 in Mazar-e-Sharif.positive results based on the FCS collectedin the first survey. Kandahar’s inhabitantsenjoy higher levels of dietary diversity(see below) but poor food consumption isstill an issue for the city.Looking at dietary diversity providesanother way to assess the quality ofurban diets based on the diversity of foodcomponents that households consume 34and to qualify the results of the food consumptionscore to see if variations acrosscities have to do with the diversity of foodavailable in each city.34. Household dietary diversity calculated with a 7-day recall periodHousehold Dietary Diversity per cityTable 2-2:Dietary Diversity Score by CityFigure 2-11Dietary Diversity per City – 7-day recall. Red (1 to 4): Poor; Yellow (5 to 7): borderline; Dark green (8-9): acceptable.Household Dietary Diversity per city (24-hour recall)40 <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong> 41

• Vegetables are seen as affordable,especially compared to fruit or meat.Does you menu vary a lot?No, not a lot. Only with the season.How often do you eat meat?Once every two weeksHow often do you eat vegetables? A few times a weekHow often do you eat fruit?It depends on seasons. Once a week or soDoes you menu vary a lot? Sometimes we cook bolani!How often do you eat meat?We may be able to eat chicken once a month.How often do you eat vegetables? We eat vegetables oftenbecause they are one of the cheapest food we can get.How often do you eat fruit?We never eat fruit because they are expensive.• Looking at dietary diversity unveilssignificant differences between thecities, with households in Kandaharreporting a more diversified diet, withthe highest average number of days ofconsumption of proteins, a significantlyhigher average of days of consumptionof dairy products than the othercities (4.98) and a higher average consumptionof tubers. Mazar-e-Sharif onthe other hand shows a significantlyless satisfying profile in dietary diversity,with the worst averages on severalkey food groups, in particular protein(0.45). Vegetables are an exception,as Mazar-e-Sharif scores high for theaverage number of days of consumptionof vegetables. These findings areconfirmed when looking at households’food consumption over the past24 hours: Kandahar shows the highestproportions of households havingconsumed key food groups such asprotein, vegetables and dairy products,while Mazar-e-Sharif consistentlyshows low consumption of thesefood groups. The higher consumptionof dairy products in Kandahar canbe linked to the higher proportion ofhouseholds owning livestock (23%),compared to other cities. Overall, thelowest household dietary diversityscore was recorded in Mazar-e-Sharif.These differences in dietary diversity andquality explain why Kandahar and Jalalabadscored higher on the FoodDoes you menu vary a lot?No, not much because we have to save money.How often do you eat meat?Once every monthHow often do you eat vegetables?Every day, usually for dinner.How often do you eat fruit? Never.Does you menu vary a lot?No, not much because we have to save money.How often do you eat meat?Once every monthHow often do you eat vegetables?Every day, usually for dinner.How often do you eat fruit? Never.Food insecurity by cityFigure 2-12HFIAS breakdown by cityConsumption Score, as the consumptionof dairy products and proteins representthe highest weights in the FCS comparedto other food groups. One explanation fora better dietary diversity in Kandahar andJalalabad is the proximity with Pakistan,from where food products are importedfor cheaper prices. This difference in foodprices also explains why Mazar-e-Shariffares poorly on the food expenditure ratioindicator. Qualitative data showed thathouseholds in Kandahar report frequentlyeating eggs and dogh (traditional liquidyogurt).“Even if the diversity of food available ishigher in urban areas, the rate of food insecurityis also higher. Because in the city,you have to pay for a lot of other things, notonly food items. Households have to pay fortheir rent, for electricity… So in terms of thequantity of food that households are able toaccess in the city, urban households are actuallyworse-off.”KII – WFP, KabulHousehold Food Insecurity Access ScaleThe Household Food Insecurity AccessScale (HFIAS) is based on the principlethat “the experience of food insecuritycauses predictable reactions and responsesthat can be captured and quantified” 36 .It shows whether households experiencedanxiety related to accessing food in theprevious month and if they reduced thequantity and quality of their food 37 . Morethan half the residents of the coveredlocations are characterised as “severelyfood insecure” according to the HouseholdFood Insecurity Access scale, andthat number rises to 84% (±1%) when the“moderately food insecure” are included.For example, nearly one household in fivereported at least one family member goingwithout food for a day at least once in theprevious four weeks.This indicator also showed marked differenceof levels of food security among thecities, following roughly the same trend aspoverty, with the exception of Kandahar,which stands out with the highest level offood insecurity despite its moderate povertylevel and relatively good profile basedon the food consumption score. (Figure2-12)It is also of some interest that the citiesthat enjoy the highest proportions ofhouseholds with acceptable food consumption– Jalalabad, Kandahar– also sufferfrom the highest proportions of severefood insecurity. Because the measuresdiffer – with the FCS focusing on overalladequacy of consumption and the HFIAS36. Coates, J., Swindale, A., Bilinsky, P. (2007) Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Household Food Access Indicator Guide (v.3). Washington,DC : FHI 360/FANTA. p. 1 37. FAO (2008), <strong>Report</strong> on Use of the HFIAS and HDDS in two survey rounds in Manica and Sofala Provinces, Mozambique. p. 3.42 <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong> 43

Accessing Health Facilities: Easier in Kabul and HeratTABLE 2-4access to piped waterFIGURE 2-15Piped Water: Inexistent in KandaharStark difference also appears betweencities when looking at access to piped waterAccess to Health Facility per cityAccessing Health Facilities: Easier inKabul and HeratArea observations show clear patterns bycity in terms of access to basic services,with Kabul and Herat benefiting fromeasier access to health facilities, whilethe average distance to a health facilityis significantly higher in Mazar-e-Sharifand Kandahar, and to a lesser extentJalalabad, as highlighted in table 2.3. Thisreflects the various levels of investmentsin the public infrastructure of each city.Public Electricity: widespread but notequally reliableA vast majority of communities (83.9%)reported being connected to the publicgrid, across the board, with only Kabulreporting a slightly lower proportion(74.3%), a fact that can be linked to thehigher proportion of IDP settlements –usually excluded from public basic services– than in the other cities. Within thecommunities, and also to a large extent90 to 100% of households were reportedto be benefiting from electricity, a fact thatconfirms the findings of the householdssurvey where 79% of households reportedhaving access to public grid and an additional4% to solar electricity. Overall,the level of access to public electricityis high across the 5 cities targeted andconfirm the impact of living in a city onaccess to public services, as only 63.8%of rural households reported having hadaccess to any source of electricity in thepast month for the NRVA 42 .Yet, the main differences appear when itcomes to the reliability of access to electricity,as Kandahar appears to be significantlydisadvantaged compared to the4 other cities. This could even get worseas electricity provision is expected todeteriorate with the withdrawal of internationaltroops. In 28% of communitiessurveyed, electricity was considered tobe not reliable (several power cuts a day)or not reliable at all (days without electricity).On the other hand 29% of communitieshad access to very reliable and43% to reliable electricity (a few powercuts per week). Here there are significantdifferences between cities with Kandaharby far in the worst situation as 48% ofcommunities said that access to electricitywas not reliable and 32% said that itwas not reliable at all. On the other end ofthe spectrum, Mazar-e-Sharif and Heratfare much better. Kandahar’s poor accessto reliable electricity is also confirmed bythe household survey as households inKandahar were much more likely to reportlong cuts of electricity (37% vs. 11% inthe overall sample) and much less likely toreport reliable access to electricity all day(6% vs. 45% in the overall sample).For piped water as well, Herat benefits froma better provision of public services, whileKandahar is significantly disadvantaged withonly 5% of communities reporting access topiped water. To compensate for the absenceof piped water, a majority of communitiesrely on wells dug inside households’ compounds,in Kandahar and in other cities alike.Private wells are a reliable source of safewater, as long as deep waters are not contaminatedby pollution. As soon as water isprovided through a pipe system, communitieshave to pay through a system of metersmeasuring their consumption.In 94% of communities visited,there was no public sewagesystem. In general, people rely onsceptic tanks within their owncompounds and organise at thecommunityPrices reported varied from 25 AFA per cubicmeter to 40-50 AFA depending on areas.When households rely on wells for water,they do not have to pay for their consumption.In the absence of proper sewage system, therisk of contamination of underground wateris increasing in Afghan cities. The topologyof Kabul and the high rates of informalsettlements make it a challenge for basicservice provision to the increasing number ofhouseholds living on the slopes of the hills ofthe city, especially when it comes to sewagesystem and piped water schemes.42. NRVA (2013), p. ivArea Observations - % of communities reporting access to piped water per city48 <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong> 49

Key findings - section 3Current conditions of the urbanpoor vary dramatically basedon their migration history: IDPs– especially recently-displaced –are at a clear disadvantage• Economic migrants and returneestend to do as well or better thanthose who never left, in terms ofprecarity, while IDPs live under considerablystarker conditions.• 36% of IDPs have poor foodconsumption based on the FSC,compared to 26-27% for economicmigrants and only 16 to 18% ofreturnee households.• 68 (±3%) of IDPs are categorizedas “severely food insecure”, whilereturnees matched residents at58-59%, with economic migrantsfaring best at 49 (±3%).• Higher levels of vulnerability andfood insecurity translate into significantlylower levels of resilienceof IDP households. IDPs were ata clear disadvantage in Herat andJalalabad, Kabul and Kandahar to alesser extent.• The present study confirms thatnewly-displaced fare significantlyworse than other IDPs and urbanpoor more generally.• Lack of access to adequatehousing and to land are two typesof vulnerability particularly prevalentamongst urban IDPs.Extreme vulnerability fuelled bysocial vulnerabilities: femaleheadedhouseholds, addictionand forms of employment as keydrivers of vulnerability• A regression analysis showed thatthe main determinants of extremevulnerability were a) belonging to afemale-headed household; b) havinga single source of income in thehousehold; c) addiction and d) toa lesser extent casual labour as amain source of income.• Having a disabled member ofhousehold (male adult) appearedas a counter-indication for foodinsecurity, although it did have animpact on poverty. This suggeststhat the pension received by disabledpeople has a positive impactof households’ resilience.• Seasonality of casual labour makeswinter a particularly difficult seasonfor urban poor, except in Jalalabadwhere seasonality has a more limitedimpact.• Education on the other hand is astrong determinant of food securityand of resilience for urbanhouseholds. A significant gapremains between genders in termsof literacy, reducing women’sabi-lity to cope with shocks.Food Security in the city isimpacted by access to incomeand nutrition security bt poorhygiene practices• Food availability is not a major determinantof food insecurity within thetargeted Afghan cities, which do notsuffer from food shortages. Little pricevolatility exists based on seasonalitybut food prices have increased overthe past 5 years. In contrast to ruralareas, seasonality only contributes tofood insecurity through casual labourin the five Afghan cities studied.• <strong>Urban</strong> households cannot rely on selfproductionto complement their foodintake as only a marginal proportionof households own livestock (13%) orgrow produce (7%), further reducingtheir ability to absorb income shocks.• Hygiene practices and awareness remainproblematic in many households.Only 33% of respondents reportedwashing their hands before eatingand only 21% of female respondentsanswered before preparing food. Poorhygiene practices are a risk factor fordiarrheal disease and poor nutritionalstatus, especially for under-five-yearoldchildren.54 <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong> 55

Mean resilience index by city and migration statusFigure 3-3Overall, this comparison of vulnerabilityand food insecurity levels across migrationgroups show that forced displacementis a stronger determinant ofpoverty and vulnerability than return.Returnees come back to the country withsets of skills and networks that increasedtheir resilience upon return. Furthermore,returnees often had time to prepare fortheir return and benefited from variousforms of assistance upon return, in particularUNHCR’s return package, whichincludes a cash grant and shelter assistancefor a large proportion of returnees 45 .Some movements of returns had beencarefully planned ahead, like for examplethe Hazara community of Jebrail in thecity of Herat, who had purchased landbefore moving back to the city.The internally displaced on the other handare usually forced to leave suddenly andhave little choice in the decision to leave.In majority coming from rural areas (seeabove), they lack the skill set, literacyand urban habits that would facilitatetheir arrival. Unlike economic migrants,they also have to leave rapidly and withlittle preparation, putting them at risk ofdire poverty, especially in the first yearsof their displacement. The community ofeconomic migrants of Darbi Iraq in Heratfor example is a good example of howcommunities and households preparetheir migration to mitigate the risks theywill face upon arrival:“People started arriving from Badghis,from Shindan, from Pashtun Zargan,from Guzarra (districts of Herat province)to settle here. Mostly, these familiesmoved because they had no workin their place of origin. There are only2 IDP families in the community. Mostof the people own their house here. Ingeneral, they bought their house herebefore coming to the neighbourhood.They bought the old houses, the emptyhouses of the area. Poor people settledhere because the land is very cheap: 3beswa cost 500, 000 Afs.”Darbi IraqCommunity Leader, Herat CityRecently displaced households:vulnerable among the vulnerableThe situation of IDPs in Herat suggeststhat some stratification exists amongstIDPs based on their time in displacement,a trend noted by NRC and UNHCRduring an IDP profiling in 2014 in Kabulcity 46 . The present study confirms thatthe newly-arrived are amongst the mostvulnerable groups as the newly-arrivedIDPs fared significantly worse than theaverage urban poor in this study:Mean Resilience Index by City and Migration StatusNotably, residents of Kabul who never lefthave the lowest average resilience scoreof all groups, with all migrants in Kabulat a considerable disadvantage (20-40points). Of further interest is that Heratireturnees, who overwhelmingly spenttime in Iran, are significantly more resilientthan even the residents who remained.This indicates that Iranian returnees derivedsome advantage abroad that madethem more resilient than other groupsupon return. Literacy and education aretwo of the benefits of having spent sometime in Iran. It must be noted that theresults in Herat are linked to the inclusionin the sample of the recent caseloads ofIDPs who arrived from Badghis and Ghorprovinces at the end of 2013 and havesettled in Herat in the camps of Kareezak,Pashtan, and Shahee Dayee checkpoint.Given their recent arrival and dire livingconditions, these IDPs present very highlevels of vulnerability and food insecurity,a reminder that integration in the city’ssocio-economic fabric is particularlydifficult to achieve for those who areforcibly displaced.Recently displaces households224 IDP respondents reportedhaving been displaced less thanone year ago in the entire sample,168 of whom are in Herat city.The main indicators show a sharpdifference in well-being betweenthis group and the means of all respondentsand of protracted IDPs:• HFIAS: Recently displaced IDPsscore a mean of 15.4 (±0.9)compared to a general populationmean of 10.0• On the household hungerscore, recently displacedhouseholds also score higher,with 2.15 compared to ageneral mean of 1.1. With amargin of error of 0.2 andscores ranging between 1 and6, this is a significant gap.• The mean consumption expenditureof recently displacedhouseholds is considerablylower than the entiresample at 962 AFA against1322 AFA for the entire sample.• Finally, the mean resiliencescore of recently displacedhouseholds is significantlyhigher than the generalpopulation mean at 208.5 (± 5points) against 157.9 for theentire sample 47 .>Both in terms of poverty and offood security, recently displacedhouseholds live in considerabledistress and enjoy significantlyworse living conditions than theaverage urban households.45. See MGSoG-Samuel Hall(2013), Evaluation of UNHCR Shelter Assistance Programme. 46. KII with UNHCR and NRC 47. Two-tailed test for the means of the group; 95% confidence interval.58 <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>Report</strong> 59