By Brian Hearn - Oklahoma Humanities Council

By Brian Hearn - Oklahoma Humanities Council

By Brian Hearn - Oklahoma Humanities Council

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

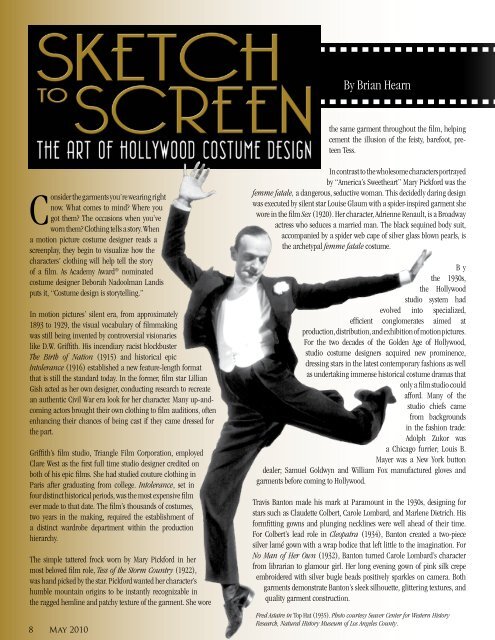

<strong>By</strong> <strong>Brian</strong> <strong>Hearn</strong>the same garment throughout the film, helpingcement the illusion of the feisty, barefoot, preteenTess.Consider the garments you’re wearing rightnow. What comes to mind? Where yougot them? The occasions when you’veworn them? Clothing tells a story. Whena motion picture costume designer reads ascreenplay, they begin to visualize how thecharacters’ clothing will help tell the storyof a film. As Academy Award ® nominatedcostume designer Deborah Nadoolman Landisputs it, “Costume design is storytelling.”In motion pictures’ silent era, from approximately1893 to 1929, the visual vocabulary of filmmakingwas still being invented by controversial visionarieslike D.W. Griffith. His incendiary racist blockbusterThe Birth of Nation (1915) and historical epicIntolerance (1916) established a new feature-length formatthat is still the standard today. In the former, film star LillianGish acted as her own designer, conducting research to recreatean authentic Civil War era look for her character. Many up-andcomingactors brought their own clothing to film auditions, oftenenhancing their chances of being cast if they came dressed forthe part.Griffith’s film studio, Triangle Film Corporation, employedClare West as the first full time studio designer credited onboth of his epic films. She had studied couture clothing inParis after graduating from college. Intolerance, set infour distinct historical periods, was the most expensive filmever made to that date. The film’s thousands of costumes,two years in the making, required the establishment ofa distinct wardrobe department within the productionhierarchy.The simple tattered frock worn by Mary Pickford in hermost beloved film role, Tess of the Storm Country (1922),was hand picked by the star. Pickford wanted her character’shumble mountain origins to be instantly recognizable inthe ragged hemline and patchy texture of the garment. She wore8 May 2010In contrast to the wholesome characters portrayedby “America’s Sweetheart” Mary Pickford was thefemme fatale, a dangerous, seductive woman. This decidedly daring designwas executed by silent star Louise Glaum with a spider-inspired garment shewore in the film Sex (1920). Her character, Adrienne Renault, is a Broadwayactress who seduces a married man. The black sequined body suit,accompanied by a spider web cape of silver glass blown pearls, isthe archetypal femme fatale costume.B ythe 1930s,the Hollywoodstudio system hadevolved into specialized,efficient conglomerates aimed atproduction, distribution, and exhibition of motion pictures.For the two decades of the Golden Age of Hollywood,studio costume designers acquired new prominence,dressing stars in the latest contemporary fashions as wellas undertaking immense historical costume dramas thatonly a film studio couldafford. Many of thestudio chiefs camefrom backgroundsin the fashion trade:Adolph Zukor wasa Chicago furrier; Louis B.Mayer was a New York buttondealer; Samuel Goldwyn and William Fox manufactured gloves andgarments before coming to Hollywood.Travis Banton made his mark at Paramount in the 1930s, designing forstars such as Claudette Colbert, Carole Lombard, and Marlene Dietrich. Hisformfitting gowns and plunging necklines were well ahead of their time.For Colbert’s lead role in Cleopatra (1934), Banton created a two-piecesilver lamé gown with a wrap bodice that left little to the imagination. ForNo Man of Her Own (1932), Banton turned Carole Lombard’s characterfrom librarian to glamour girl. Her long evening gown of pink silk crepeembroidered with silver bugle beads positively sparkles on camera. Bothgarments demonstrate Banton’s sleek silhouette, glittering textures, andquality garment construction.Fred Astaire in Top Hat (1935). Photo courtesy Seaver Center for Western HistoryResearch, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

Adrian Adolph Greenberg, who came to be known simply as Adrian, was hired asMetro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s chief costume designer in 1928. One of the highlights ofAdrian’s tenure at MGM was the opulent production of Marie Antoinette (1938),which involved thousands of costumes and ballooned the film’s budget to a thenunheard of $3 million. It was Adrian’s versatility for the differing goals of both fashionand costume that enabled him to start his own fashion house in 1941. Undoubtedly,Adrian is best remembered for his iconic ruby sequined slippers, clicked into history byJudy Garland in The Wizard of Oz (1939), as well as the broad shoulder pads createdfor Joan Crawford that became a significant fashion trend in the 1940s.Walter Plunkett came to Hollywood hoping to be an actor, but found work in the late1920s at the RKO studio where he set up the costume department. It was here thatproducer David O. Selznick discovered him for the important task of clothing thehundreds of characters in Gone with the Wind (1939), one of the most important“costume pictures” ever made.Of all the costume designers of Hollywood’s Golden Age, Edith Head is surely the bestknown, most prolific, and most decorated, having won more Oscars ® than any otherwoman—eight. She borrowed a fellow student’s sketches, which she passed off asher own to get her foot in the door as a costume sketch artist at Paramount. Sheapprenticed under Travis Banton, eventually replacing him as chief costume designerin 1938, a position she held for 30 years. Her combination of work ethic, economicalmanagement, studio diplomacy, and wily careerism brought the work of the costumedesigner into the spotlight.Two of Edith Head’s Academy Awards ® were for Audrey Hepburn’s first two starringroles in Roman Holiday (1953) and Sabrina (1954). Head’s position as costumedesigner was complicated by Hepburn’s rapport with the young Parisian fashiondesigner Hubert de Givenchy. Hepburn’s impeccable taste and Givenchy’s designs forher contemporary characters quickly made her an instant style icon, even thoughGivenchy did not receive screen credit until Funny Face (1957). Of her long timecollaborator, Hepburn commented, “Givenchy’s creations always gave me a sense ofsecurity and confidence, and my work went more easily in the knowledge that I lookedabsolutely right . . . In a certain way one can say that Hubert de Givenchy has ‘created’me over the years.”It is worth noting that in 1967 the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences madethe decision to merge what were previously two categories for costume design: blackand white, primarily given to contemporary films, and color, the given choice formusicals, epics, and fantasy films. Since that time, only a couple of designers havewon the top prize for contemporary costume design, despite the fact that contemporarycostumes represent the majority of film work today. Audiences expect to see everydayclothing which is often mistaken for a lack of design; on the contrary, just as muchthought and research is required to create a convincing contemporary character. EllenMirojnick, veteran costume designer, said about her craft:<strong>Oklahoma</strong> <strong>Humanities</strong> 9

Cary Grant and Deborah Kerr in An Affair to Remember (1957). Photo courtesy GeorgeEastman House Motion Picture Department Collection.10 May 2010Fred Astaire in Top Hat(1935). Photo courtesy SeaverCenter for Western HistoryResearch, Natural HistoryMuseum of Los AngelesCounty.

You gotta know what’s in the character’scloset before you’re ready to dressthe character for the role. What’s intheir mind, and what’s in their past?In love, what are they willing togive up? What’s their chemistrywith other people? It makes mefurious [that] the work that goesinto these contemporary films isn’t publiclyappreciated by the academy. Designing the film,thinking through who that character is and how to createhim visually, is an art—whether it’s off a piece of paper pattern Ihave fabricated in the work room or off a rack at Bloomingdale’s. IfI dress them in something from the real world, it’s because it’s 100percent appropriate.Male film costumes often portray professions: an astronaut fromApollo 13 (1995), a firefighter from Backdraft (1991), andbookmaker “Ace” Rothstein in Casino (1995). Some comefrom the imaginary worlds of comic books and animation,including Christopher Reeve’s iconic Supermancostume, Dick Tracy’s yellow fedora and trenchcoat worn by Warren Beatty in the 1990film, and the leather jacket andbladed gloves worn by HughJackman as Wolverinein the recent X-Menfilms. The Americancowboy, an earlyfixture of the Western film genre, wasrepresented by garments and accessoriesworn by silent stars William S. Hart andTom Mix. The evolution of Western filmscan be seen in garments worn by JohnWayne, Robert Redford, Tom Selleck, andHeath Ledger.In Audrey Hepburn’s presentation of the Oscar ® for Best Costume Design in1986, she stated, “The costume designer is not only essential but is vital, forit is they who create the look of the character without which no performancecan succeed. Theirs is a monumental job, for they must be not only artists, buttechnicians, researchers, and historians!”Hollywood costumes provide a fascinating walkabout through the historyof American film and shed light on the unique contributions of costumedesigners. The unheralded creativity and craftsmanship of those designershelped make motion pictures the dominant art form of the 20 th century. Theirefforts trace our shared cultural heritage of clothing the human form.<strong>Brian</strong> <strong>Hearn</strong> is Film Curator at the <strong>Oklahoma</strong> City Museum of Art.<strong>Oklahoma</strong> <strong>Humanities</strong> 11