primates_in_peril_2012_2014_full_report

primates_in_peril_2012_2014_full_report

primates_in_peril_2012_2014_full_report

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

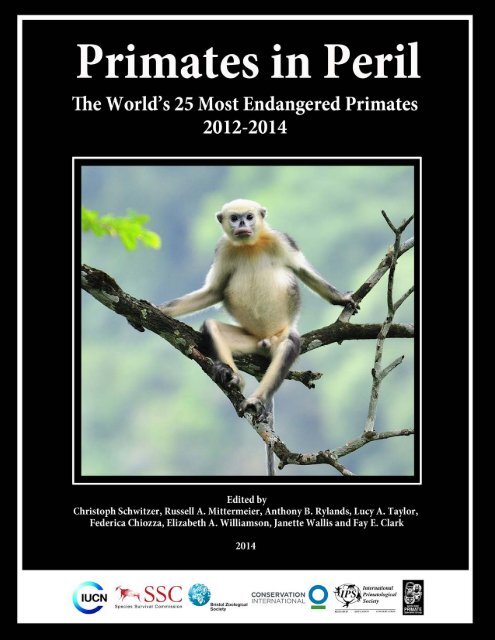

Front cover photo:Male Tonk<strong>in</strong> snub-nosed monkey Rh<strong>in</strong>opithecus avunculus © Le Van Dung

Primates <strong>in</strong> Peril:The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates<strong>2012</strong>–<strong>2014</strong>Edited byChristoph Schwitzer, Russell A. Mittermeier, Anthony B. Rylands,Lucy A. Taylor, Federica Chiozza, Elizabeth A. Williamson,Janette Wallis and Fay E. ClarkIllustrations by Stephen D. NashIUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG)International Primatological Society (IPS)Conservation International (CI)Bristol Zoological Society (BZS)

This publication was supported by the Margot Marsh Biodiversity Foundation and the Humane Society International.Published by:Copyright:IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS),Conservation International (CI), Bristol Zoological Society (BZS)©<strong>2014</strong> Conservation InternationalAll rights reserved. No part of this <strong>report</strong> may be reproduced <strong>in</strong> any form or byany means without permission <strong>in</strong> writ<strong>in</strong>g from the publisher.Inquiries to the publisher should be directed to the follow<strong>in</strong>g address:Russell A. Mittermeier, Chair, IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group,Conservation International, 2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500, Arl<strong>in</strong>gton, VA 22202, USA.Citation (<strong>report</strong>): Schwitzer, C., Mittermeier, R. A., Rylands, A. B., Taylor, L. A., Chiozza, F., Williamson, E. A.,Wallis, J. and Clark, F. E. (eds.). <strong>2014</strong>. Primates <strong>in</strong> Peril: The World’s 25 Most EndangeredPrimates <strong>2012</strong>–<strong>2014</strong>. IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), InternationalPrimatological Society (IPS), Conservation International (CI), and Bristol ZoologicalSociety, Arl<strong>in</strong>gton, VA. iv+87pp.Citation (species): Mbora, D. N. M. and Butynski, T. M. <strong>2014</strong>. Tana River red colobus Piliocolobus rufomitratus(Peters, 1879). In: C. Schwitzer, R. A. Mittermeier, A. B. Rylands, L. A. Taylor, F. Chiozza,E. A. Williamson, J. Wallis and F. E. Clark (eds.), Primates <strong>in</strong> Peril: The World’s 25 MostEndangered Primates <strong>2012</strong>–<strong>2014</strong>, pp. 20–21. IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG),International Primatological Society (IPS), Conservation International (CI), andBristol Zoological Society, Arl<strong>in</strong>gton, VA.Layout andillustrations:Available from:Pr<strong>in</strong>ted by:© Stephen D. Nash, Conservation International, Arl<strong>in</strong>gton, VA, and Department ofAnatomical Sciences, Health Sciences Center, Stony Brook University, StonyBrook, NY, USA.Jill Lucena, Conservation International, 2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500, Arl<strong>in</strong>gton,VA 22202, USA. E-mail: j.lucena@conservation.org Website: www.primate-sg.orgTray, Glen Burnie, MDISBN: 978-1-934151-69-3ii

ContentsAcknowledgements.........................................................................................ivThe World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates: <strong>2012</strong>–<strong>2014</strong>..........................................1Africa .........................................................................................................................10Rondo dwarf galago (Galagoides rondoensis) ....................................................................11Roloway monkey (Cercopithecus roloway) ...........................................................................14Bioko red colobus (Piliocolobus pennantii pennantii) .......................................................17Tana River red colobus (Piliocolobus rufomitratus) .......................................................20Grauer’s gorilla (Gorilla ber<strong>in</strong>gei graueri) .........................................................................22Madagascar ............................................................................................................... 25Madame Berthe’s mouse lemur (Microcebus berthae) ...................................................26Sclater’s black lemur or Blue-eyed black lemur (Eulemur flavifrons) ...........................29Red ruffed lemur (Varecia rubra) ....................................................................................33Northern sportive lemur (Lepilemur septentrionalis) ....................................................36Silky sifaka (Propithecus candidus) .......................................................................................38Indri (Indri <strong>in</strong>dri) ..................................................................................................................44Asia....................................................................................................48Pygmy tarsier (Tarsius pumilus) ..........................................................................................49Javan slow loris (Nycticebus javanicus) ................................................................................51Pig-tailed snub-nosed langur (Simias concolor) ...............................................................55Delacour’s langur (Trachypithecus delacouri) .....................................................................57Golden-headed langur or Cat Ba langur (Trachypithecus poliocephalus)........................59Western purple-faced langur (Semnopithecus vetulus nestor) .......................................61Grey-shanked douc monkey (Pygathrix c<strong>in</strong>erea) ................................................................65Tonk<strong>in</strong> snub-nosed monkey (Rh<strong>in</strong>opithecus avunculus) ..................................................67Cao-Vit or Eastern black-crested gibbon (Nomascus nasutus) .......................................69Neotropics ................................................................................................................72Variegated or Brown spider monkey (Ateles hybridus) .................................................73Ecuadorian brown-headed spider monkey (Ateles fusciceps fusciceps) .........................75Ka’apor capuch<strong>in</strong> (Cebus kaapori) .......................................................................................77San Martín titi monkey (Callicebus oenanthe) .................................................................79Northern brown howler (Alouatta guariba guariba) .........................................................81Editors’ addresses .....................................................................................................84Contributors’ addresses .............................................................................................84iii

AcknowledgementsThe <strong>2012</strong>–<strong>2014</strong> iteration of the World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates was drawn up dur<strong>in</strong>g anopen meet<strong>in</strong>g held dur<strong>in</strong>g the XXIV Congress of the International Primatological Society (IPS),Cancún, 14 August <strong>2012</strong>, and was published as a series of Species Fact Sheets (Mittermeier etal. <strong>2012</strong>).Here, we present an extended version of the <strong>2012</strong>–<strong>2014</strong> list, with more comprehensive<strong>in</strong>formation about the threats fac<strong>in</strong>g these <strong>primates</strong> and with bibliographic references cited <strong>in</strong>the text. We have updated the species profiles from the 2008–2010 edition for those speciesrema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g on the list, and added additional profiles for newly listed species.This publication is a jo<strong>in</strong>t effort of the IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group, the InternationalPrimatological Society, Conservation International, and the Bristol Zoological Society.We are most grateful to the Margot Marsh Biodiversity Foundation for provid<strong>in</strong>g significantsupport for research and conservation efforts on these endangered <strong>primates</strong> through thedirect provision of grants and through the Primate Action Fund, adm<strong>in</strong>istered by Ms. EllaOutlaw of the President’s Office at Conservation International. Over the years, the foundationhas provided support for the tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g workshops held before the biennial congresses of theInternational Primatological Society and helped primatologists to attend the meet<strong>in</strong>gs to discussthe composition of the list of the world’s 25 most endangered <strong>primates</strong>.We would like to thank all of the authors who contributed to the f<strong>in</strong>al <strong>2012</strong>–<strong>2014</strong> version:Thomas M. Butynski, Drew T. Cron<strong>in</strong>, Dong Thanh Hai, Leonardo Gomes Neves, Nanda Grow,Sharon Gursky-Doyen, Ha Thang Long, Gail W. Hearn, Le Khac Quyet, Andrés L<strong>in</strong>k, LongYoncheng, Edward E. Louis, Jr., David N. M. Mbora, W. Scott McGraw, Fabiano R. Melo, AlbaLucia Morales Jiménez, Paola Moscoso-R., Tilo Nadler, K. Anna I. Nekaris, V<strong>in</strong>cent Nijman,Stuart Nixon, John F. Oates, Lisa M. Paciulli, Erw<strong>in</strong> Palacios, Richard J. Passaro, Erik R. Patel,Andrew Perk<strong>in</strong>, Phan Duy Thuc, Mart<strong>in</strong>a Raffel, Guy H. Randriatah<strong>in</strong>a, Matthew Richardson,E. Johanna Rode, Christian Roos, Rasanayagam Rudran, Livia Schäffler, Daniela Schrudde,Roswitha Stenke, Jatna Supriatna, Maurício Talebi, Diego G. Tirira, Bernardo Urbani, JanVermeer, Sylviane N. M. Volampeno and John R. Zaonarivelo.ReferenceMittermeier, R.A., C. Schwitzer, A.B. Rylands, L.A. Taylor, F. Chiozza, E.A. Williamson and J.Wallis (eds.). <strong>2012</strong>. Primates <strong>in</strong> Peril: The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates <strong>2012</strong>–<strong>2014</strong>. IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), ConservationInternational (CI), Arl<strong>in</strong>gton, VA, and Bristol Conservation and Science Foundation, Bristol,UK. 40pp.iv

The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates: <strong>2012</strong>-<strong>2014</strong>Here we <strong>report</strong> on the seventh iteration of the biennial list<strong>in</strong>g of a consensus of the 25 primate species consideredto be among the most endangered worldwide and the most <strong>in</strong> need of conservation measures.The <strong>2012</strong>–<strong>2014</strong> list of the world’s 25 most endangered <strong>primates</strong> has five species from Africa, six from Madagascar,n<strong>in</strong>e from Asia, and five from the Neotropics (Table 1). Madagascar tops the list with six species. Vietnam has five,Indonesia three, Brazil two, and Ch<strong>in</strong>a, Colombia, Côte d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ecuador,Equatorial Gu<strong>in</strong>ea, Ghana, Kenya, Peru, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, and Venezuela each have one.The changes made <strong>in</strong> this list compared to the previous iteration (2010–<strong>2012</strong>) were not because the situation of then<strong>in</strong>e species that were dropped (Table 2) has improved. In some cases, for example, Varecia variegata, the situationhas <strong>in</strong> fact worsened. By mak<strong>in</strong>g these changes we <strong>in</strong>tend rather to highlight other, closely-related species endur<strong>in</strong>gequally bleak prospects for their survival. An exception may be the greater bamboo lemur, Prolemur simus, forwhich recent studies have confirmed a considerably larger distribution range and larger estimated population sizethan previously assumed. However, severe threats to this species <strong>in</strong> eastern Madagascar rema<strong>in</strong>.N<strong>in</strong>e of the <strong>primates</strong> were not on the previous (2010–<strong>2012</strong>) list (Table 3). Seven of them are listed as among theworld’s most endangered <strong>primates</strong> for the first time. The Tana River red colobus and the Ecuadorian brownheadedspider monkey had already been <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> previous iterations, but were subsequently removed <strong>in</strong> favourof other highly threatened species of the same genera. The <strong>2012</strong>–<strong>2014</strong> list now conta<strong>in</strong>s two members each of thesegenera, thus particularly highlight<strong>in</strong>g the severe threats they are fac<strong>in</strong>g.Dur<strong>in</strong>g the discussion of the <strong>2012</strong>–<strong>2014</strong> list at the XXIV Congress of IPS <strong>in</strong> Cancún <strong>in</strong> <strong>2012</strong>, a number of otherhighly threatened primate species were considered for <strong>in</strong>clusion (Table 4). For all of these, the situation <strong>in</strong> the wildis as precarious as it is for those that eventually made it on the list.1

Table 1. The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates <strong>2012</strong>–<strong>2014</strong>AfricaGalagoides rondoensis Rondo dwarf galago TanzaniaCercopithecus roloway Roloway monkey Côte d’Ivoire, GhanaPiliocolobus pennantii pennantii Bioko red colobus Equatorial Gu<strong>in</strong>ea (Bioko Is.)Piliocolobus rufomitratus Tana River red colobus KenyaGorilla ber<strong>in</strong>gei graueri Grauer’s gorilla DRCMadagascarMicrocebus berthae Madame Berthe’s mouse lemur MadagascarEulemur flavifrons Sclater’s black lemur MadagascarVarecia rubra Red ruffed lemur MadagascarLepilemur septentrionalis Northern sportive lemur MadagascarPropithecus candidus Silky sifaka MadagascarIndri <strong>in</strong>dri Indri MadagascarAsiaTarsius pumilus Pygmy tarsier Indonesia (Sulawesi)Nycticebus javanicus Javan slow loris Indonesia (Java)Simias concolor* Pig-tailed snub-nosed langur Indonesia (Mentawai Is.)Trachypithecus delacouri Delacour’s langur VietnamTrachypithecus poliocephalus Golden-headed or Cat Ba langur VietnamSemnopithecus vetulus nestor Western purple-faced langur Sri LankaPygathrix c<strong>in</strong>erea Grey-shanked douc monkey VietnamRh<strong>in</strong>opithecus avunculus Tonk<strong>in</strong> snub-nosed monkey VietnamNomascus nasutus Cao-Vit or Eastern black-crested gibbon Ch<strong>in</strong>a, VietnamNeotropicsAteles hybridus Variegated spider monkey Colombia, VenezuelaAteles fusciceps fuscicepsEcuadorian brown-headedEcuadorspider monkeyCebus kaapori Ka’apor capuch<strong>in</strong> BrazilCallicebus oenanthe San Martín titi monkey PeruAlouatta guariba guariba Northern brown howler Brazil* The pig-tailed snub-nosed langur Simias concolor had previously been classified as Nasalis concolor and referred to as such <strong>in</strong> the <strong>2012</strong>–<strong>2014</strong> Top 25 Fact sheets.2

Table 2. Primate species <strong>in</strong>cluded on the 2010–<strong>2012</strong> list that were removed from the <strong>2012</strong>–<strong>2014</strong> list.AfricaPiliocolobus epieni Niger Delta red colobus NigeriaMadagascarProlemur simus Greater bamboo lemur MadagascarVarecia variegata Black-and-white ruffed lemur MadagascarAsiaTarsius tumpara Siau Island tarsier Indonesia (Siau Is.)Macaca silenus Lion-tailed macaque IndiaPongo pygmaeus pygmaeus Northwest Bornean orangutan Indonesia (West Kalimantan, Borneo),Malaysia (Sarawak)NeotropicsCebus flavius Blond capuch<strong>in</strong> BrazilCallicebus barbarabrownae Barbara Brown’s titi monkey BrazilOreonax flavicaudaPeruvian yellow-tailed woollymonkeyPeruTable 3. Primate species that were added to the <strong>2012</strong>–<strong>2014</strong> list. The Tana River red colobus and the Ecuadorianbrown-headed spider monkey were added to the list after previously be<strong>in</strong>g removed. The other seven species arenew to the list.AfricaPiliocolobus rufomitratus Tana River red colobus KenyaMadagascarMicrocebus berthae Madame Berthe’s mouse lemur MadagascarVarecia rubra Red ruffed lemur MadagascarIndri <strong>in</strong>dri Indri MadagascarAsiaTarsius pumilus Pygmy tarsier Indonesia (Sulawesi)NeotropicsAteles fusciceps fuscicepsEcuadorian brown-headed spider EcuadormonkeyCebus kaapori Ka’apor capuch<strong>in</strong> BrazilCallicebus oenanthe San Martín titi monkey PeruAlouatta guariba guariba Northern brown howler Brazil3

Table 4. Primate species considered dur<strong>in</strong>g the discussion of the <strong>2012</strong>–<strong>2014</strong> list at the IPS Congress <strong>in</strong> Cancúnthat did not make it onto the list, but are also highly threatened.AfricaPiliocolobus preussi Preuss’s red colobus Cameroon, NigeriaGorilla gorilla diehli Cross River gorilla Nigeria, CameroonPan troglodytes ellioti Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzee Nigeria, CameroonMadagascarCheirogaleus sibreei Sibree’s dwarf lemur MadagascarHapalemur alaotrensis Lac Alaotra bamboo lemur MadagascarEulemur c<strong>in</strong>ereiceps White-collared brown lemur MadagascarPropithecus perrieri Perrier’s sifaka MadagascarAsiaNasalis larvatus Proboscis monkey Indonesia (Borneo)Presbytis comata Grizzled leaf monkey IndonesiaRh<strong>in</strong>opithecus strykeri Myanmar snub-nosed monkey Myanmar, Ch<strong>in</strong>aNomascus ha<strong>in</strong>anus Ha<strong>in</strong>an black-crested gibbon Ch<strong>in</strong>a (Ha<strong>in</strong>an)Nomascus leucogenysNorthern white-cheekedLaos, Vietnam, Ch<strong>in</strong>ablack-crested gibbonNeotropicsChiropotes satanas Black bearded saki BrazilLeontopithecus caissara Black-faced lion tamar<strong>in</strong> BrazilSagu<strong>in</strong>us bicolor Pied tamar<strong>in</strong> BrazilCallicebus caquetensis Caquetá titi monkey Colombia4

Photos of some of the Top 25 Most Endangered Primates. From top to bottom, left to right: 1. Microcebus berthae (photo by John R. Zaonarivelo);2. Nomascus nasutus (female)(photo by Xu Yongb<strong>in</strong>); 3. Nomascus nasutus (male) (photo by Xu Yongb<strong>in</strong>); 4. Alouatta guariba guariba (photoby Leonardo Gomes Neves); 5. Cercopithecus roloway (photo by S. Wolters, WAPCA); 6. Indri <strong>in</strong>dri (photo by Russell A. Mittermeier); 7. Simiasconcolor (juvenile)(photo by Richard Tenaza); 8. Callicebus oenanthe (photo by Russell A. Mittermeier); 9. Varecia rubra (photo by Russell A.Mittermeier); 10. Lepilemur septentrionalis (photo by Edward E. Louis, Jr.); 11. Trachypithecus poliocephalus (photo by Tilo Nadler); 12. Gorillaber<strong>in</strong>gei graueri (photo by Russell A. Mittermeier); 13. Propithecus candidus (photo by Iñaki Relanzón); 14. Galagoides rondoensis (photo byAndrew Perk<strong>in</strong>); 15. Pygathrix c<strong>in</strong>erea (photo by Tilo Nadler); 16. Piliocolobus p. pennantii (photo by R. A. Bergl).5

Rondo Dwarf GalagoGalagoides rondoensis Honess <strong>in</strong> K<strong>in</strong>gdon, 1997Tanzania(<strong>2012</strong>)Andrew Perk<strong>in</strong>Weigh<strong>in</strong>g approximately 60 g, this is the smallest of allgalago species (Perk<strong>in</strong> et al. 2013). It is dist<strong>in</strong>ct fromother dwarf galagos <strong>in</strong> its dim<strong>in</strong>utive size, a bottlebrush-shapedtail, its reproductive anatomy, and itsdist<strong>in</strong>ctive “double unit roll<strong>in</strong>g call” (Perk<strong>in</strong> and Honess2013). Current knowledge <strong>in</strong>dicates that this speciesoccurs <strong>in</strong> two dist<strong>in</strong>ct areas, one <strong>in</strong> southwest Tanzanianear the coastal towns of L<strong>in</strong>di and Mtwara, the otherapproximately 400 km further north, above the RufijiRiver, <strong>in</strong> pockets of forest around Dar es Salaam. Onefurther population occurs <strong>in</strong> Sadaani National Park,approximately 100 km north of Dar es Salaam. Rondodwarf galagos have a mixed diet of <strong>in</strong>sects and fruit,often feed close to the ground, and move by verticalcl<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g and leap<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the shrubby understorey.They build daytime sleep<strong>in</strong>g nests, which are often <strong>in</strong>the canopy (Bearder et al. 2003). As with many small<strong>primates</strong>, G. rondoensis is probably subject to predationby owls and other nocturnal predators. Among these,genets, palm civets and snakes <strong>in</strong>voke <strong>in</strong>tense episodesof alarm call<strong>in</strong>g (Perk<strong>in</strong> and Honess 2013).Over the last decade, the status of G. rondoensishas changed from Endangered <strong>in</strong> 2000 to CriticallyEndangered <strong>in</strong> 2008 on the IUCN Red List (Perk<strong>in</strong> et al.2008). It has an extremely limited and fragmented range<strong>in</strong> a number of remnant patches of Eastern AfricanCoastal Dry Forest (sensu Burgess and Clarke 2000;p.18) <strong>in</strong> Tanzania, namely those at Zaran<strong>in</strong>ge forest(06°08’S, 38°38’E) <strong>in</strong> Sadaani National Park (Perk<strong>in</strong>2000), Pande Game Reserve (GR) (06°42’S, 39°05’E),Pugu/Kazimzumbwi (06°54’S, 39°05’E) (Perk<strong>in</strong> 2003,2004), Rondo (NR) (10°08’S, 39°12’E), Litipo (10°02’S,39°29’E) and Ziwani (10°20’S, 40°18’E) forest reserves(FR) (Honess 1996; Honess and Bearder 1996). Newsub-populations were identified <strong>in</strong> 2007 near L<strong>in</strong>ditown <strong>in</strong> Chitoa FR (09°57’S, 39°27’E) and Ruawa FR(09°44’S, 39°33’E), and <strong>in</strong> 2011 <strong>in</strong> Noto Village ForestReserve (09°53’S, 39°25’E) (Perk<strong>in</strong> et al. 2011, 2013.)and <strong>in</strong> the northern population at Ruvu South ForestReserve (06°58’S, 38°52’E). Specimens of G. rondoensis,orig<strong>in</strong>ally described as Galagoides demidovii phasma,11Rondo dwarf galago (Galagoides rondoensis)(Illustration: Stephen D. Nash)were collected by Ionides from Rondo Plateau <strong>in</strong>1955, and Lumsden from Nambunga, near Kitangari,(approximately 10°40’S, 39°25’E) on the MakondePlateau <strong>in</strong> Newala District <strong>in</strong> 1953. Doubts surroundthe persistence of this species on the Makonde Plateau,which has been extensively cleared for agriculture.Surveys there <strong>in</strong> 1992 failed to detect any extantpopulations (Honess 1996).

No detailed surveys have been conducted to assesspopulation sizes of G. rondoensis. Distribution surveyshave been conducted, however, <strong>in</strong> the southern (Honess1996, Perk<strong>in</strong> et al. <strong>in</strong> prep.) and northern coastal forestsof Tanzania (29 surveyed) and Kenya (seven surveyed)(Perk<strong>in</strong> 2000, 2003, 2004; Perk<strong>in</strong> et al., 2013). Absolutepopulation sizes rema<strong>in</strong> undeterm<strong>in</strong>ed but recentsurveys have provided estimates of density (3–6/ha atPande Game Reserve [Perk<strong>in</strong> 2003] and 8/ha at PuguForest Reserve [Perk<strong>in</strong> 2004]) and relative abundancefrom encounter rates (3–10/hr at Pande Game Reserveand Pugu/Kazimzumbwi Forest Reserve [Perk<strong>in</strong> 2003,2004]) and 3.94/hr at Rondo Forest Reserve (Honess1996). There is a clear and urgent need for further surveysto determ<strong>in</strong>e population sizes <strong>in</strong> these dw<strong>in</strong>dl<strong>in</strong>g forestpatches.In 2008, it was <strong>report</strong>ed that the total area of forest <strong>in</strong>which G. rondoensis is currently known to occur doesnot exceed 101.6 km² (Pande GR: 2.4 km², Rondo FR:25 km², Ziwani FR: 7.7 km², Pugu/Kazimzumbwi FR:33.5 km², Litipo FR: 4 km², Zaran<strong>in</strong>ge forest: 20 km²,Chitoa FR: 5 km², and Ruawa FR 4 km²) (M<strong>in</strong>imum areadata source: Burgess and Clarke 2000; Doggart 2003;Perk<strong>in</strong> et al. <strong>in</strong> prep.). New data on forest area change<strong>in</strong>dicates that while two new sub-populations have beendiscovered; the overall area of occupancy hovers around100 km². 2008 and <strong>2014</strong> forest-area estimations are asfollows: Zaran<strong>in</strong>ge 2008: 20 km², <strong>2014</strong>: 15 km²; Pande2008: 2.4 km², <strong>2014</strong>: 2.4 km²; Pugu/Kazimzumbwe2008: 33.5 km², <strong>2014</strong>: 9 km²; Ruvu South 2008: 20 km²,<strong>2014</strong>: 10 km²; Ruawa 2008: 4 km², <strong>2014</strong>: 4 km²; Litipo2008: 4 km², <strong>2014</strong>: 3 km²; Chitoa 2008: 4 km², <strong>2014</strong>: 5km²; Noto 2008: 21 km², <strong>2014</strong>: 20 km²; Rondo 2008:25 km², <strong>2014</strong>: 25 km²; Ziwani 2008: 7.7 km², <strong>2014</strong>: 1km². The total forest area estimates are as follows - 2008:101.6 km², <strong>2014</strong>: 94.4 km².The major threat fac<strong>in</strong>g this species is loss of habitat.All sites are subject to some level of agriculturalencroachment, charcoal manufacture and/or logg<strong>in</strong>g.All sites, except Pande (Game Reserve), Zaran<strong>in</strong>ge(with<strong>in</strong> Saadani National Park) and Rondo (NatureReserve), are national or local authority forest reservesand as such nom<strong>in</strong>ally, but <strong>in</strong> practice m<strong>in</strong>imally,protected. S<strong>in</strong>ce 2008, there have been changesresult<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> protection of two forests.The Noto plateau forest, formerly open village land, ispart of a newly created village forest reserve, and theRondo Forest Reserve has now been declared a newNature Reserve, both are important for Rondo galagoconservation given their relatively large size. Givencurrent trends <strong>in</strong> charcoal production for nearby Dar esSalaam, the forest reserves of Pugu and Kazimzumbwiwere predicted to disappear over the next 10–15 years(Ahrends 2005). Pugu/Kazimzumbwe as well as RuvuSouth have seen cont<strong>in</strong>ued and predicted losses to therampant charcoal trade s<strong>in</strong>ce Ahrends (2005) study.Pande, as a Game Reserve, is perhaps more secure,and Zaren<strong>in</strong>ge forest, be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a National Park, is themost protected part of the range of G. rondoensis. In thesouth, the Noto, Chitoa and Rondo populations are themost secure, as they are buffered by tracts of woodland.The type population at Rondo is buffered by woodlandand P<strong>in</strong>us plantations managed by the Rondo ForestryProject, and is now a Nature Reserve. Litipo, and RuawaFRs are under threat from border<strong>in</strong>g village lands.Ziwani is now mostly degraded scrub forest, thicket andgrassland.Conservation action is urgently needed by: monitor<strong>in</strong>grates of habitat loss, survey<strong>in</strong>g new areas for remnantpopulations, estimat<strong>in</strong>g population size, reassess<strong>in</strong>g thephylogenetic relationships of the sub-populations and<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g awareness. There is emerg<strong>in</strong>g data (vocaland penile morphological) that the northern andsouthern populations may be phylogenetically dist<strong>in</strong>ctwith important taxonomic implications. As such theconservation of all sub-populations is important.Across its known range, the Rondo galago can befound <strong>in</strong> sympatry with a number of other galagos,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g two much larger species <strong>in</strong> the genusOtolemur: Garnett’s galago O. garnettii (Least Concern,Butynski et al. 2008a), and the thick-tailed galago, O.crassicaudatus (Least Concern, Bearder 2008). TheRondo galago is sympatric with the Zanzibar galago,Galagoides zanzibaricus (Least Concern, Butynski et al.2008b), <strong>in</strong> the northern parts of its range (for example,<strong>in</strong> Zaran<strong>in</strong>ge forest, Pugu/Kazimzumbwi FR and PandeGR). In the southern parts of its range (for example, <strong>in</strong>Rondo, Litipo and Noto), the Rondo galago is sympatricwith Grant’s galago, Galagoides granti (Least Concern,Honess et al. 2008).A new project to address these conservation andresearch issues is be<strong>in</strong>g implemented this year. Targetedconservation <strong>in</strong>itiatives are tak<strong>in</strong>g place <strong>in</strong> Ruvu SouthFR, Chitoa FR and Noto VFR.12

ReferencesAhrends, A. 2005. Pugu Forest: go<strong>in</strong>g, go<strong>in</strong>g. Arc Journal17: 23.Bearder, S.K. 2008. Otolemur crassicaudatus. In: IUCN2013. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version2013.2. . Accessed 16 March<strong>2014</strong>.Bearder, S. K., L. Ambrose, C. Harcourt, P. E. Honess,A. Perk<strong>in</strong>, S. Pullen, E. Pimley and N. Svoboda. 2003.Species-typical patterns of <strong>in</strong>fant care, sleep<strong>in</strong>g siteuse and social cohesion among nocturnal <strong>primates</strong> <strong>in</strong>Africa. Folia Primatologica 74: 337–354.Burgess, N. D. and G. P. Clarke. 2000. Coastal Forestsof Eastern Africa. IUCN – The World ConservationUnion, Gland, Switzerland, and Cambridge, UK.Butynski, T. M., S. K. Bearder, S. and Y. de Jong. 2008a.Otolemur garnettii. In: IUCN 2013. IUCN Red List ofThreatened Species. Version 2013.2. . Accessed 16 March <strong>2014</strong>.Butynski, T. M., Y de Jong, A. Perk<strong>in</strong>, S. K. Bearder andP. Honess. 2008b. Galagoides zanzibaricus. In: IUCN2013. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version2013.2. . Accessed 16 March<strong>2014</strong>.Doggart, N. (ed.). 2003. Pande Game Reserve: ABiodiversity Survey. Tanzania Forest ConservationGroup, Technical Paper 7. Dar es Salaam.Perk<strong>in</strong>, A. 2000. A Field Study of the ConservationStatus and Diversity of Galagos <strong>in</strong> Zaran<strong>in</strong>ge Forest,Coast Region, Tanzania. Report of WWF-Tanzania,Dar-es-Salaam.Perk<strong>in</strong>, A. 2003. Mammals. In: Pande Game Reserve: ABiodiversity Survey, N. Doggart (ed.), 95pp. TanzaniaForest Conservation Group, Technical Paper 7. Dar esSalaam.Perk<strong>in</strong>, A. 2004. Galagos of the Coastal Forests andEastern Arc Mtns. of Tanzania – Notes and Records.Tanzania Forest Conservation Group, Technical Paper8. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.Perk<strong>in</strong>, A., S. K. Bearder, P. Honess and T. M. Butynski.2008. Galagoides rondoensis. In: IUCN 2013. IUCNRed List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. . Accessed 16 March <strong>2014</strong>.Perk<strong>in</strong>, A., S. K. Bearder and J. Karlsson. In prep. Galagosurveys <strong>in</strong> Rondo, Litipo, Chitoa, Ruawa, Ndimbaand Namatimbili forests, L<strong>in</strong>di Region, southeasternTanzania.Perk<strong>in</strong>, A., B. Samwel and J. Gwegime. 2011. Go<strong>in</strong>g forgold <strong>in</strong> the Noto Plateau, SE Tanzania. Arc Journal 26:14–16.Perk<strong>in</strong>, A.W., P. E. Honess and T. M. Butynski. 2013.Mounta<strong>in</strong> dwarf galago Galagoides or<strong>in</strong>us. In: Mammalsof Africa: Volume II: Primates, T. Butynski, J. K<strong>in</strong>gdonand J. Kal<strong>in</strong> (eds.), pp. 452–454. Bloomsbury Publish<strong>in</strong>g,London.Honess, P. E. 1996. Speciation among galagos (Primates,Galagidae) <strong>in</strong> Tanzanian forests. Doctoral thesis, OxfordBrookes University, Oxford, UK.Honess, P. E. and S. K. Bearder. 1996. Descriptions ofthe dwarf galago species of Tanzania. African Primates2: 75–79.Honess, P. E., A. Perk<strong>in</strong>, S. K. Bearder, T. M. Butynskiand Y. de Jong. 2008. Galagoides granti. In: IUCN 2013.IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2.. Accessed on 16 March <strong>2014</strong>.K<strong>in</strong>gdon, J. 1997. The K<strong>in</strong>gdon Field Guide to AfricanMammals. Academic Press, London.13

Roloway MonkeyCercopithecus diana roloway (Schreber, 1774)Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire(2002, 2006, 2008, 2010, <strong>2012</strong>)W. Scott McGraw & John F. OatesRoloway monkey (right) (Cercopithecus diana roloway) and Diana monkey (left) (Cercopithecus diana diana)(Illustrations: Stephen D. Nash)There are two subspecies of Cercopithecus diana, bothhighly attractive, arboreal monkeys that <strong>in</strong>habit theupper Gu<strong>in</strong>ean forests of West Africa (Grubb et al.2003). Groves (2001) considers the two subspecies to besufficiently dist<strong>in</strong>ct to be regarded as <strong>full</strong> species. Of thetwo forms, the Roloway (C. d. roloway) which is knownfrom Ghana and central and eastern Côte d’Ivoire, ismore seriously threatened with ext<strong>in</strong>ction; it is classifiedas Endangered (Oates et al. 2008), but its status shouldbe upgraded to Critically Endangered.The roloway subspecies is dist<strong>in</strong>guished by its broadwhite brow l<strong>in</strong>e, long white beard and yellow thighs.Roloway monkeys are upper-canopy specialists thatprefer undisturbed forest. Destruction and degradationof their habitat and relentless hunt<strong>in</strong>g for the bushmeattrade have reduced their population to small, isolatedpockets. Miss Waldron’s red colobus (Procolobus badiuswaldroni) once <strong>in</strong>habited many of the same forest areasas the Roloway, but is now almost certa<strong>in</strong>ly ext<strong>in</strong>ct(Oates 2011). Unless more effective conservation actionis taken, there is a strong possibility that the Rolowaymonkey will also disappear <strong>in</strong> the near future.have failed to confirm the presence of these monkeys <strong>in</strong>any reserves <strong>in</strong> western Ghana, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Bia NationalPark, Krokosua Hills Forest Reserve, Subri River ForestReserve and Dadieso Forest Reserve (Oates 2006;Gatti 2010; Buzzard and Parker <strong>2012</strong>; Wiafe 2013),although it is possible that the Ankasa ConservationArea still conta<strong>in</strong>s a few <strong>in</strong>dividuals (Magnuson 2003;Gatti 2010). The Kwabre forest <strong>in</strong> the far southwesterncorner of the country is the only site <strong>in</strong> Ghana at whichany Roloways have been <strong>report</strong>ed as seen by scientistsor conservationists <strong>in</strong> the last decade; surveys at thissite were made by West African Primate ConservationAction <strong>in</strong> 2011 and <strong>2012</strong> (WAPCA <strong>2012</strong>). Kwabreconsists of fragments of swamp forest along the lowerTano River, adjacent to the Tanoé forest <strong>in</strong> Côted’Ivoire; WAPCA has launched a community-basedconservation project with villages around Kwabre,and collaboration with conservation efforts <strong>in</strong> Tanoé.Meanwhile, further efforts should be made to ascerta<strong>in</strong>whether any Roloway monkeys still survive <strong>in</strong> theAnkasa, because this site has significant conservationpotential and Roloways have been <strong>report</strong>ed there <strong>in</strong> therelatively recent past.Over the last 40 years Roloway monkeys have been In neighbour<strong>in</strong>g Côte d’Ivoire, the Roloway’s status issteadily extirpated <strong>in</strong> Ghana. Several recent surveys equally dire. Less than ten years ago Roloways were14

known or strongly suspected to exist <strong>in</strong> three forests:the Yaya Forest Reserve, the Tanoé forest adjacent tothe Ehy Lagoon, and Parc National des Iles Ehotilé(McGraw 1998, 2005; Koné and Akpatou 2005). Surveysof eighteen areas between 2004 and 2008 (Gonedelé Biet al. 2008, <strong>2012</strong>) confirmed the presence of Rolowaysonly <strong>in</strong> the Tanoé forest suggest<strong>in</strong>g that the Rolowaymonkey may have been elim<strong>in</strong>ated from at least twoforest areas (Parc National des Iles Ehotilé, Yaya ForestReserve) with<strong>in</strong> the last decade. Subsequent surveyscarried out <strong>in</strong> southern Côte d’Ivoire suggest a handfulof Roloways may still survive <strong>in</strong> two forest reservesalong the country’s coast. On 21 June <strong>2012</strong>, Gonedelé biSery observed one Roloway <strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>in</strong> the DassiokoSud Forest Reserve; however, Roloways have not beenlocated <strong>in</strong> this forest reserve s<strong>in</strong>ce, despite regularpatrols there (Bitty et al. 2013; Gonedelé Bi et al. <strong>in</strong>review). In <strong>2012</strong>, Gonedelé Bi and A. E. Bitty observedRoloways <strong>in</strong> Port Gauthier Forest Reserve, and <strong>in</strong>October 2013, Gonedelé Bi obta<strong>in</strong>ed photographs ofmonkeys poached <strong>in</strong>side this reserve, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g an imagepurported to be a Roloway. The beard on this <strong>in</strong>dividualappears short for a Roloway, rais<strong>in</strong>g the possibility thatsurviv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dividuals <strong>in</strong> this portion of the <strong>in</strong>terfluvialregion may <strong>in</strong> fact be hybrids. The Dassioko Sud andPort Gauthier Forest Reserves are described as coastalevergreen forests and both are heavily degraded due toa large <strong>in</strong>flux of farmers and hunters from the northernportion of the country (Bitty et al. 2013). Gonedelé Biand colleagues, <strong>in</strong> cooperation with SODEFOR (Sociétéde Développement des Forêts) and local communities,have organized regular forest patrols aimed at remov<strong>in</strong>gillegal farmers and hunters from both reserves.Nevertheless, the most recent surveys have failed tolocate liv<strong>in</strong>g Roloways <strong>in</strong> either reserve (Gonedelé Biand Bitty 2013) mean<strong>in</strong>g that the only forest <strong>in</strong> Côted’Ivoire where Roloways are confirmed to exist is theTanoé forest adjacent to the Ehy Lagoon. This wet forestalso harbours one of the few rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g populations ofwhite-naped mangabeys <strong>in</strong> Côte d’Ivoire. Efforts ledby I. Koné and <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g several organizations (CEPA,WAPCA) helped stop a large palm oil company fromfurther habitat degradation and a community-basedconservation effort has helped slow poach<strong>in</strong>g with<strong>in</strong>this forest (Koné 2008). Unfortunately, hunt<strong>in</strong>g stilloccurs <strong>in</strong> Tanoé and the primate populations with<strong>in</strong> itare undoubtedly decreas<strong>in</strong>g (Gonedelé Bi et al. 2013). Asthe potential last refuge for Roloways and White-napedmangabeys, the protection of the Tanoé forest should bethe highest conservation priority. By any measure, theRoloway monkey must be considered one of the mostcritically endangered monkeys <strong>in</strong> Africa and appears tobe on the verge of ext<strong>in</strong>ction (Oates 2011).ReferencesBitty, E. A., S. Gonedelé Bi and W. S. McGraw. 2013.Accelerat<strong>in</strong>g deforestation and hunt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> protectedreserves jeopardize <strong>primates</strong> <strong>in</strong> southern Côte d’Ivoire.American Journal of Physical Anthropology Supp. 56:81–82.Buzzard, P. J. and A. J. A. Parker. <strong>2012</strong>. Surveys from theSubri River Forest Reserve, Ghana. African Primates 7:175–183.Gatti, S. 2010. Status of Primate Populations <strong>in</strong> ProtectedAreas Targeted by the Community Forest BiodiversityProject. Unpublished <strong>report</strong>, West African PrimateConservation Action (WAPCA), Accra, Ghana.Gonedelé Bi, S. and A. E. Bitty. 2013. Conservation ofthreatened <strong>primates</strong> of Dassioko Sud and Port Gauthierforest reserves <strong>in</strong> coastal Côte d’Ivoire. F<strong>in</strong>al Report toPrimate Conservation Inc., Charlestown, RI.Gonedelé Bi, S., I. Koné, J.-C. K. Béné, A. E. Bitty,B. K. Akpatou, Z. Goné Bi, K. Ouattara and D. A.Koffi. 2008. Tanoé forest, south-eastern Côte d’Ivoireidentified as a high priority site for the conservation ofcritically endangered <strong>primates</strong> <strong>in</strong> West Africa. TropicalConservation Science 1: 265–278.Gonedelé Bi, S., J.-C. K. Béné, A. E. Bitty, A. N’Guessan,A. D. Koffi, B. Akptatou and I. Koné. 2013. Rolowayguenon (Cercopithecus diana roloway) and white-napedmangabey (Cercocebus atys lunulatus) prefer mangrovehabitats <strong>in</strong> Tanoé Forest, southeastern Ivory Coast.Ecosystems and Ecography 3: 126.Gonedelé Bi, S, I. Koné, A. E. Bitty, J.-C. K. Béné,B. Akptatou and D. Z<strong>in</strong>ner. <strong>2012</strong>. Distribution andconservation status of catarrh<strong>in</strong>e <strong>primates</strong> <strong>in</strong> Côted’Ivoire (West Africa). Folia Primatologica 83: 11–23.Gonedelé Bi S., E. A. Bitty and W. S. McGraw. In review.Conservation of threatened <strong>primates</strong> <strong>in</strong> Dassioko Sudand Port Gauthier forest reserves: use of field patrols toassess primate abundance and illegal human activities.Groves, C. P. 2001. Primate Taxonomy. SmithsonianInstitution Press, Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC.15

Grubb, P., T. M. Butynski, J. F. Oates, S. K. Bearder, T.R. Disotell, C. P. Groves and T. T. Struhsaker. 2003.An assessment of the diversity of African <strong>primates</strong>.International Journal of Primatology 24: 1301–1357.Koné, I. 2008. The Tanoé Swamp Forest, a poorly knownhigh conservation value forest <strong>in</strong> jeopardy <strong>in</strong> southeasternCôte d’Ivoire. Unpublished Report.Koné, I. and K. B. Akpatou. 2005. Recherche en Côted’Ivoire de trois s<strong>in</strong>ges gravement menaces d’ext<strong>in</strong>ction.CEPA Magaz<strong>in</strong>e 12: 11 –13.Magnuson, L. 2003. F<strong>in</strong>al Brief: Ecology andConservation of the Roloway Monkey <strong>in</strong> Ghana.Unpublished <strong>report</strong>, Wildlife Division of Ghana,Forestry Commission, Ghana.McGraw, W. S. 1998. Surveys of endangered <strong>primates</strong><strong>in</strong> the forest reserves of eastern Côte d’Ivoire. AfricanPrimates 3: 22–25.McGraw, W. S. 2005. Update on the search for MissWaldron’s red colobus monkey (Procolobus badiuswaldroni). International Journal of Primatology 26: 605–619.Oates, J. F. 2006. Primate Conservation <strong>in</strong> the Forestsof Western Ghana: Field Survey Results, 2005–2006.Report to the Wildlife Division, Forestry Commission,Ghana.Oates, J. F. 2011. Primates of West Africa: A Field Guideand Natural History. Conservation International,Arl<strong>in</strong>gton, VA.Oates, J. F., S. Gippoliti and C. P. Groves. 2008.Cercopithecus diana ssp. roloway. In: IUCN 2013. IUCNRed List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. . Accessed 16 March <strong>2014</strong>.WAPCA. <strong>2012</strong>. Annual Report. West African PrimateConservation Action, Accra, Ghana.Wiafe, E. 2013. Status of the Critically EndangeredRoloway monkey (Cercopithecus diana roloway) <strong>in</strong> theDadieso Forest Reserve, Ghana. African Primates 8:9–15.16

Bioko Red ColobusPiliocolobus pennantii pennantii (Waterhouse, 1838)Bioko Island, Equatorial Gu<strong>in</strong>ea(2004, 2006, 2010, <strong>2012</strong>)Drew T. Cron<strong>in</strong>, Gail W. Hearn & John F. OatesPennant’s red colobus monkey Piliocolobus pennantii ispresently regarded by the IUCN Red List as compris<strong>in</strong>gthree subspecies: P. pennantii pennantii of Bioko, P. p.epieni of the Niger Delta, and P. p. bouvieri of the CongoRepublic. Some accounts give <strong>full</strong> species status toall three of these monkeys (Groves 2007; Oates 2011;Groves and T<strong>in</strong>g 2013). P. p. pennantii is currentlyclassified as Endangered (Oates and Struhsaker 2008).Piliocolobus pennantii pennantii may once have occurredover most of Bioko, but it is now probably limited to anarea of less than 300 km² with<strong>in</strong> the Gran Caldera anda 510 km² range <strong>in</strong> the Southern Highlands ScientificReserve (GCSH) (Cron<strong>in</strong> et al. 2013). Low numbers ofP. p. pennantii may have persisted through the 1980s <strong>in</strong>Pico Basile National Park (330 km²) (Gonzalez Kirchner1994), but there have been no confirmed historicalor current sight<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> the area. Another isolatedpopulation was believed to exist <strong>in</strong> the southeasternextent of the GCSH; however, recent surveys did notuncover any evidence of this monkey and it is probablyextirpated <strong>in</strong> that area (Cron<strong>in</strong> 2013).Bioko red colobus (Piliocolobus pennantii pennantii)(Illustration: Stephen D. Nash)P. p. pennantii is threatened by bushmeat hunt<strong>in</strong>g,most notably s<strong>in</strong>ce the early 1980s when a commercialbushmeat market appeared <strong>in</strong> the town of Malabo(Butynski and Koster 1994). Follow<strong>in</strong>g the discoveryof offshore oil <strong>in</strong> 1996, and the subsequent expansionof Equatorial Gu<strong>in</strong>ea’s economy, ris<strong>in</strong>g urban demandled to <strong>in</strong>creased numbers of primate carcasses <strong>in</strong> thebushmeat market (Morra et al. 2009; Cron<strong>in</strong> 2013). InNovember 2007, a primate hunt<strong>in</strong>g ban was enactedon Bioko, but it lacked any realistic enforcement andcontributed to a spike <strong>in</strong> the numbers of monkeys <strong>in</strong> themarket. Between October 1997 and September 2010,a total of 1,754 P. p. pennantii were observed for sale<strong>in</strong> the market (Cron<strong>in</strong> 2013). The rate of occurrenceof P. p. pennantii carcasses <strong>in</strong> the market though, hasbeen consistently less than more common <strong>primates</strong> onBioko, suggest<strong>in</strong>g that its restricted range is passivelyprotect<strong>in</strong>g the rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g population from significanthunt<strong>in</strong>g.The average price paid <strong>in</strong> the Malabo market for anadult P. p. pennantii <strong>in</strong> 2008 was about US$50 (D. T.17

Cron<strong>in</strong>, unpubl. data). This is well over twice the costof the readily available, high quality whole chicken andbeef at the same market. Similar high prices are paidon Bioko for all seven species of monkeys and for bothspecies of duikers. Ma<strong>in</strong>land carcasses are now alsoregularly shipped to Malabo for sale suggest<strong>in</strong>g thattransport costs are covered by the high profits relativeto those <strong>in</strong> Nigeria, Cameroon, or Rio Muni (Morraet al. 2009). Bushmeat on Bioko is, obviously, now a‘luxury food’ (Hearn et al. 2006). The cont<strong>in</strong>ued highflow of <strong>primates</strong>, duikers and other wildlife <strong>in</strong>to theMalabo bushmeat market <strong>in</strong>dicates that neither of theprotected areas is receiv<strong>in</strong>g adequate management andthat exist<strong>in</strong>g hunt<strong>in</strong>g laws lack enforcement from thegovernment of Equatorial Gu<strong>in</strong>ea.Of the other two subspecies of P. pennantii, Bouvier’s redcolobus P. p. bouvieri of east-central Republic of Congohas not been observed alive by scientists for at least 25years, rais<strong>in</strong>g concerns that it may be ext<strong>in</strong>ct (Oates1996; Struhsaker 2005). The habitat of the Niger Deltared colobus P. p. epieni <strong>in</strong> southern Nigeria has beenseverely degraded by logg<strong>in</strong>g, the surviv<strong>in</strong>g monkeysface ever-<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g hunt<strong>in</strong>g pressure, and there is noprotected area with<strong>in</strong> its range (Oates 2011).Red colobus monkeys are probably more threatenedthan any other taxonomic group of <strong>primates</strong> <strong>in</strong> Africa(Oates 1996; Struhsaker 2005, 2011), and the statusof the western African forms is especially precarious.Preuss’s red colobus P. preussi of western Cameroon andsoutheastern Nigeria is Critically Endangered (Oateset al. 2008) as a result of relentless hunt<strong>in</strong>g, and MissWaldron’s red colobus P. badius waldroni of eastern Côted’Ivoire and western Ghana is now almost certa<strong>in</strong>lyext<strong>in</strong>ct (Oates 2011). All rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g West African redcolobus populations and their habitats therefore requirerigorous protection. Such protection would also greatlyassist the conservation of many sympatric threatenedprimate taxa. On Bioko this would <strong>in</strong>clude the BiokoPreuss’s monkey Cercopithecus preussi <strong>in</strong>sularis, theBioko red-eared monkey C. erythrotis erythrotis, theGolden-bellied crowned monkey C. pogonias pogonias,the Bioko greater white-nosed monkey C. nictitansmart<strong>in</strong>i, the Bioko black colobus C. satanas satanas,and the Bioko drill Mandrillus leucophaeus poensis.Protection of P. pennantii epieni and P. preussi and theirhabitats on the ma<strong>in</strong>land would benefit populations ofNigeria-Cameroon chimpanzees Pan troglodyes ellioti,Ebo Forest gorillas Gorilla gorilla subsp., CameroonPreuss’s monkey Cercopithecus preussi preussi, Nigerianwhite-throated guenon Cercopithecus erythrogasterpococki, Ma<strong>in</strong>land drill Mandrillus leucophaeus poensisand Red-capped mangabey Cercocebus torquatus.ReferencesButynski, T. M. and S. H. Koster. 1994. Distributionand conservation status of <strong>primates</strong> <strong>in</strong> Bioko Island,Equatorial Gu<strong>in</strong>ea. Biodiversity and Conservation 3:893–909.Cron<strong>in</strong>, D. T. 2013. The Impact of Bushmeat Hunt<strong>in</strong>gon the Primates of Bioko Island, Equatorial Gu<strong>in</strong>ea.Department of Biology. Drexel University, Philadelphia.PA.Cron<strong>in</strong>, D. T., C. Riaco and G. W. Hearn. 2013. Survey ofthreatened monkeys <strong>in</strong> the Iladyi River Valley Region,Southeastern Bioko Island, Equatorial Gu<strong>in</strong>ea. AfricanPrimates 8: 1–8.Gonzàlez Kirchner, J. P. 1994. Ecología y Conservaciónde los Primates de Gu<strong>in</strong>ea Ecuatorial. Ceiba Ediciones,Cantabria, Spa<strong>in</strong>.Groves, C. P. 2007. The taxonomic diversity of theColob<strong>in</strong>ae of Africa. Journal of Anthropological Sciences85: 7–34.Groves, C. P. and N. T<strong>in</strong>g. 2013. Pennant’s red colobusPiliocolobus pennantii. In: Handbook of the Mammalsof the World. Volume 3. Primates, R. A. Mittermeier, A.B. Rylands and D. E. Wilson (eds.), pp.707–708. LynxEdicions, Barcelona.Hearn, G., W. A. Morra and T. M. Butynski. 2006.Monkeys <strong>in</strong> Trouble: The Rapidly Deteriorat<strong>in</strong>gConservation Status of the Monkeys on Bioko Island,Equatorial Gu<strong>in</strong>ea. Report, Bioko BiodiversityProtection Program, Glenside, Pennsylvania.Morra, W., G. Hearn, and A. J. Buck. 2009. The marketfor bushmeat: Colobus satanas on Bioko Island.Ecological Economics 68: 2619–2626.Oates, J. F. 2011. Primates of West Africa: A Field Guideand Natural History. Conservation International,Arl<strong>in</strong>gton, VA.18

Oates, J. F. 1996. African Primates: Status Survey andConservation Action Plan. Revised edition. IUCN,Gland, Switzerland.Oates, J. F. and T. T. Struhsaker. 2008. Procolobuspennantii ssp. pennantii. In: IUCN 2013. IUCN RedList of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. . Accessed on 17 March <strong>2014</strong>.Oates, J. F., T. T. Struhsaker, B. Morgan, J. L<strong>in</strong>der and N.T<strong>in</strong>g. 2008. Procolobus preussi. In: IUCN 2013. IUCNRed List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. . Accessed 17 March <strong>2014</strong>.Struhsaker, T. T. 2005. The conservation of red colobusand their habitats. International Journal of Primatology26: 525–538.Struhsaker, T. T. 2011. The Red Colobus Monkeys:Variation <strong>in</strong> Demography, Behavior, and Ecology ofEndangered Species. Oxford University Press, Oxford.19

Tana River Red ColobusPiliocolobus rufomitratus (Peters, 1879)Kenya(2002, 2004, 2006, 2008, <strong>2012</strong>)David N. M. Mbora & Thomas M. ButynskiTana River red colobus (Piliocolobus rufomitratus)(Illustration: Stephen D. Nash)Gallery forests along the lower Tana River, Kenya, arepart of the East African Coastal Forests BiodiversityHotspot. The forests are the only habitat for two endemic<strong>primates</strong>: the Tana River red colobus, Piliocolobusrufomitratus, and the Tana River mangabey, Cercocebusgaleritus Peters, 1879. Piliocolobus rufomitratus isclassified as one of four subspecies of Procolobusrufomitratus on the IUCN Red List of 2008, which isstill current. The other three are Procolobus r. oustaleti(Trouessart, 1906), Procolobus r. tephrosceles (Elliot,1907), and Procolobus r. tholloni (Milne-Edwards,1886). Here, we follow Groves (2005, 2007; Grovesand T<strong>in</strong>g 2013) <strong>in</strong> plac<strong>in</strong>g all red colobus monkeys <strong>in</strong>the genus Piliocolobus, and rufomitratus and the othersubspecies mentioned above as <strong>full</strong> species. Piliocolobusrufomitratus is currently classified as Endangered onthe IUCN Red List (Butynski et al. 2008). Both theTana River red colobus and the Tana River mangabey<strong>in</strong>habit forest fragments (size range, about 1 ha to 500ha) along a 60-km stretch from Nkanjonja to Mitapani(01°55’S, 40°05’E) (Butynski and Mwangi 1995; Mboraand Meikle 2004). There are another six sympatric<strong>primates</strong> <strong>in</strong> the area, but only the red colobus andmangabey are endemic and entirely forest dependent.The current population of the Tana River red colobusis less than 1,000 <strong>in</strong>dividuals and decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, and whilethe population of the mangabey is a little larger, it too isdecl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. Indeed, recent genetic analyses have shownthat the effective population sizes of the two speciesare less than 100 <strong>in</strong>dividuals (Mbora and McPeek, <strong>in</strong>revision).Several factors render the long-term survival of the TanaRiver red colobus and mangabey bleak and precarious.First, forest is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly be<strong>in</strong>g cleared for agriculturalexpansion, and the rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g patches used as a sourceof build<strong>in</strong>g materials and a variety of non-timber forestproducts. Second, <strong>in</strong> January 2007, the High Courtof Kenya ordered the annulment of the Tana RiverPrimate National Reserve (TRPNR) because, the court20

found, that the reserve had not been established <strong>in</strong>accordance with the law. About half of the rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gforest was legally protected <strong>in</strong> TRPNR, and thereforeno habitat of the Tana River red colobus and mangabeyis legally protected at the present time. Third, habitatloss outside the TRPNR was exacerbated by the failureof the Tana Delta Irrigation Project (TDIP). TDIP wasa rice-grow<strong>in</strong>g scheme managed by the Tana and AthiRivers Development Authority that had protected forestpatches on their land.Despite the troubles highlighted here, there is reasonfor hope for the Tana River forests and the endemicmonkeys. One of us (Mbora) has ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed a researchproject <strong>in</strong> the area over the years. In 2011, Mboracollaborated with Lara Allen to ascerta<strong>in</strong> how andwhy local people exploited the Tana forests, <strong>in</strong> orderto identify opportunities and constra<strong>in</strong>ts for possibleconservation action. The study found that the Pokomopeople of Tana have a comprehensive traditional systemof natural resource use, conservation and management,and a strong desire to preserve the flora and faunaof the forests as part of their heritage. They stronglysupport community development <strong>in</strong>itiatives related tothe conservation of natural resources as these delivertangible benefits to the people and their environment.Partly galvanized by the participatory nature of theresearch, an organization called the Ndera CommunityConservancy has now been established <strong>in</strong> Tana. Thesole mission of this formally registered communitybasedorganization is to protect and conserve about halfof the forest patches formerly with<strong>in</strong> the TRPNR, andimprove the viability of particular forest patches outsidethe Reserve. The Ndera Community Conservancy iswork<strong>in</strong>g with government conservation <strong>in</strong>itiatives andis mak<strong>in</strong>g some progress. However, <strong>in</strong> order for thecommunity to make significant progress <strong>in</strong> enhanc<strong>in</strong>gthe viability of the habitat of the Tana River red colobus,the support of <strong>in</strong>ternational conservation agencies isneeded. With community structures, government, andthe <strong>in</strong>ternational conservation community work<strong>in</strong>gtogether, the prospects for the long-term viability ofTana River <strong>primates</strong> can be greatly improved.ReferencesButynski, T. M. and G. Mwangi. 1995. Census of Kenya’sendangered red colobus and crested mangabey. AfricanPrimates 1: 8–10.Butynski, T. M., T. T. Struhsaker and Y. de Jong. 2008.Procolobus rufomitratus ssp. rufomitratus. In: IUCN2013. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version2013.2. . Accessed 17 March<strong>2014</strong>.Groves, C. P. 2005. Order Primates. In: Mammal Speciesof the World, D. E. Wilson and D. M. Reeder (eds),pp.111–184. The Johns Hopk<strong>in</strong>s University Press,Baltimore, MD.Groves, C. P. 2007. The taxonomic diversity of theColob<strong>in</strong>ae of Africa. Journal of Anthropological Sciences85: 7–34.Groves, C. P. and N. T<strong>in</strong>g. 2013. Tana River red colobusPiliocolobus rufomitratus. In: Handbook of the Mammalsof the World. Volume 3. Primates, R. A. Mittermeier, A.B. Rylands and D. E. Wilson (eds.), p.709. Lynx Edicions,Barcelona.Mbora, D. N. M. and D. B. Meikle. 2004. Forestfragmentation and the distribution, abundance andconservation of the Tana River red colobus (Procolobusrufomitratus). Biological Conservation 118: 67–77.Mbora, D. N. M. and L. Allen. 2011. The Tana Forests‘People for Conservation and Conservation for People’Initiative (PCCP): Preserv<strong>in</strong>g the Habitat of the TanaRiver Red Colobus (Procolobus rufomitratus) and theTana River Mangabey (Cercocebus galeritus) ThroughCommunity Conservation and Development <strong>in</strong>Tana River District, Kenya. F<strong>in</strong>al Report on Phase 1,Mohamed b<strong>in</strong> Zayed Species Conservation Fund, AbuDhabi.Mbora, D. N. M and M. A. McPeek. In revision. Howmonkeys see a forest: population genetic structure <strong>in</strong>two forest monkeys. Conservation Genetics.21

Grauer’s GorillaGorilla ber<strong>in</strong>gei graueri Matschie, 1914Democratic Republic of Congo2010, <strong>2012</strong>Stuart Nixon & Elizabeth A. WilliamsonGrauer’s gorilla (Gorilla ber<strong>in</strong>gei graueri) (Illustration: Stephen D. Nash)The largest of the four subspecies of Gorilla, Grauer’sgorilla (Gorilla ber<strong>in</strong>gei graueri), is listed on CITESassociated with abandoned agricultural clear<strong>in</strong>gs, m<strong>in</strong>esand villages (e.g., Schaller 1963; Nixon et al. 2006).Appendix I and classified as Endangered on the IUCNRed List (Robb<strong>in</strong>s et al. 2008). Grauer’s gorillas <strong>in</strong>habit S<strong>in</strong>ce the 1950s, habitat conversion has beenmixed lowland forest and the montane forests of theAlbert<strong>in</strong>e Rift escarpment <strong>in</strong> the eastern DemocraticRepublic of Congo (DRC). Formerly known as theeastern lowland gorilla, the name is mislead<strong>in</strong>g as thistaxon ranges between approximately 600 m and 2,900m above sea level. While relatively little is known aboutthe ecology and behaviour of Grauer’s gorilla, their dietis rich <strong>in</strong> herbs, leaves, bark, lianas and v<strong>in</strong>es, seasonallyavailablefruit, bamboo (at the higher altitudes), and<strong>in</strong>vertebrates (e.g., Schaller 1963; Yamagiwa et al.2005). These gorillas opportunistically raid fields tofeed on crops and are often found <strong>in</strong> regenerat<strong>in</strong>g forestwidespread, while a proliferation of 12-gauge shotgunshas facilitated the hunt<strong>in</strong>g of large mammals, result<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> the local ext<strong>in</strong>ction of gorillas <strong>in</strong> many areas (Emlenand Schaller 1960; P. Anderson, pers. comm.). Threatsto their survival were exacerbated throughout the 1990sand early 2000s with persistent conflict <strong>in</strong> the GreatLakes region of Africa. Refugees, <strong>in</strong>ternally displacedpeople and armed groups settled throughout easternDRC, putt<strong>in</strong>g enormous pressure on natural resources,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the national parks. Destruction of highaltitudeforest for timber and charcoal productioncont<strong>in</strong>ue to threaten the isolated gorilla populations22

that persist <strong>in</strong> the North Kivu highlands, while poach<strong>in</strong>gto feed artisanal m<strong>in</strong>ers and associated armed groupspresents the most serious and immediate threat. Largenumbers of military personnel stationed <strong>in</strong> rural areasand numerous rebel groups active throughout the regionhave been heavily implicated <strong>in</strong> illegal m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g activitiesand facilitate access to the firearms and ammunition thatfuel the ongo<strong>in</strong>g civil conflict (United Nations 2010).Kahuzi-Biega National Park (KBNP) is a centre of illegalresource extraction, largely under the control of rebelmilitia. Meanwhile, DRC’s protected area authority (theCongolese Institute for Nature Conservation – ICCN)rema<strong>in</strong>s chronically underf<strong>in</strong>anced and its staff poorlyequipped. ICCN faces conflicts not only with localcommunities but also with armed groups, and highlydedicated ICCN personnel have been killed <strong>in</strong> the l<strong>in</strong>eof duty.NGOs are work<strong>in</strong>g with the government authoritiesto support protected area rehabilitation and developconservation programmes, and <strong>in</strong> <strong>2012</strong> IUCN publisheda conservation strategy with clear priorities for Grauer’sgorillas (Maldonado et al. <strong>2012</strong>). The establishment ofaccurate basel<strong>in</strong>es on the abundance and distributionof this subspecies and the threats to their survival isurgently needed to guide the future implementationof the action plan. Four, broadly-def<strong>in</strong>ed populationcentres are recognized: Maïko-Tayna-Usala (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gMaïko National Park and adjacent forests, Tayna NatureReserve, Kisimba-Ikoba Nature Reserve and the Usalaforest), Kahuzi-Kasese (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the lowland sector ofKBNP and adjacent forests), and the Itombwe Massif.Additional isolated populations are found <strong>in</strong> Masisi,the highland sector of KBNP and Mt. Tshiaberimu<strong>in</strong> Virunga National Park. In the 1990s, Hall et al.(1998) estimated that the total population numbered8,660–25,500 <strong>in</strong>dividuals, despite substantial habitatloss and several localized ext<strong>in</strong>ctions. The largestknown population, <strong>in</strong> the lowland sector of KBNP, hass<strong>in</strong>ce undergone a catastrophic 80% decl<strong>in</strong>e (Ams<strong>in</strong>iet al. 2008). Elsewhere, 50% reductions have beendocumented (Wildlife Conservation Society, unpubl.data) and a recent analysis of ape habitat across Africaestimates that suitable environmental conditionsfor Grauer’s gorillas have decl<strong>in</strong>ed by 52% s<strong>in</strong>ce the1990s (Junker et al. <strong>2012</strong>). Acknowledg<strong>in</strong>g gaps <strong>in</strong>our knowledge, data collated dur<strong>in</strong>g the past 14 years<strong>in</strong>dicate that Grauer’s gorilla numbers are likely tobeen reduced to 2,000–10,000 <strong>in</strong>dividuals (Nixon et al.<strong>2012</strong>). In collaboration with ICCN and the Max PlanckInstitute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, aconsortium of <strong>in</strong>ternational NGOs has <strong>in</strong>itiated a twoyearproject to assess the status of Grauer’s gorilla acrossits range.In the face of ongo<strong>in</strong>g political and economic <strong>in</strong>stability<strong>in</strong> eastern DRC, the threats are likely to rema<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>tensefor the foreseeable future, and concerted action toprotect Grauer’s gorilla is needed. In its favour, a highlylocalized distribution <strong>in</strong> discrete populations enablesefficient prioritization of valuable resources, and arecent <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> the KBNP highland population (WCSunpublished data) is evidence that highly-targetedconservation efforts can be successful even <strong>in</strong> the faceof acute pressures.ReferencesAms<strong>in</strong>i, F., O. Ilambu, I. Liengola, D. Kujirakw<strong>in</strong>ja, J.Hart, F. Grossman and A. J. Plumptre. 2008. The Impactof Civil War on the Kahuzi-Biega National Park: Resultsof Surveys between 2000–2008. Wildlife ConservationSociety, Institut Congolais pour la Conservation de laNature, K<strong>in</strong>shasa, DRC.Emlen, J. T. and G. B. Schaller. 1960. Distribution andstatus of the mounta<strong>in</strong> gorilla (Gorilla gorilla ber<strong>in</strong>gei).Zoologica 45: 41–52.Hall, J. S., K. Saltonstall, B.-I. Inogwab<strong>in</strong>i and I. Omari.1998. Distribution, abundance and conservation statusof Grauer’s gorilla. Oryx 32: 122–130.Junker, J., S. Blake, C. Boesch, G. Campbell, L. du Toit, C.Duvall, A. Ekobo, G. Etoga, A. Galat-Luong, J. Gamys,J. Ganas-Swaray, S. Gatti, A. Ghiurghi, N. Granier, J.Hart, J. Head, I. Herb<strong>in</strong>ger, T. C. Hicks, B. Huijbregts,I. S. Imong, N. Kumpel, S. Lahm, J. L<strong>in</strong>dsell, F. Maisels,M. McLennan, L. Mart<strong>in</strong>ez, B. Morgan, D. Morgan, F.Mul<strong>in</strong>dahabi, R. Mundry, K. P. N’Goran, E. Normand,A. Ntongho, D. T. Okon. C. A. Petre, A. Plumptre, H.Ra<strong>in</strong>ey, S. Regnaut, C. Sanz, E. Stokes, A. Tondossama,S. Tranquilli, J. Sunderland-Groves, P. Walsh, Y. Warren,E. A. Williamson and H. S. Kuehl. <strong>2012</strong>. Recent decl<strong>in</strong>e<strong>in</strong> suitable environmental conditions for African greatapes. Diversity and Distributions 18: 1077–1091.Maldonado, O., C. Avel<strong>in</strong>g, D. Cox, S. Nixon, R. Nishuli,D. Merlo, L. P<strong>in</strong>tea and E. A. Williamson. <strong>2012</strong>. Grauer’sGorillas and Chimpanzees <strong>in</strong> Eastern DemocraticRepublic of Congo (Kahuzi-Biega, Maïko, Tayna andItombwe Landscape): Conservation Action Plan <strong>2012</strong>–23

2022. IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group, M<strong>in</strong>istryof Environment, Nature Conservation and Tourism,Institut Congolais pour la Conservation de la Nature,and Jane Goodall Institute, Gland, Switzerland.Nixon, S., E. Emmanuel, K. Mufabule, F. Nixon, D.Bolamba and P. Mehlman. 2006. The Post-conflictStatus of Grauer’s Eastern Gorilla (Gorilla ber<strong>in</strong>geigraueri) and Other Wildlife <strong>in</strong> the Maïko NationalPark Southern Sector and Adjacent Forests, EasternDemocratic Republic of Congo. Unpublished <strong>report</strong>,Institut Congolais pour la Conservation de la Natureand Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International, Goma,DRC.Nixon. S., A. J. Plumptre, L. P<strong>in</strong>tea, J. A. Hart, F. Ams<strong>in</strong>i,E. Bahati, Delattre, C. K. Kaghoma, D. Kujirakw<strong>in</strong>ja, J.C. Kyungu, K. Mufabule, R. Nishuli and P. Ngobobo.<strong>2012</strong>. The forgotten gorilla; historical perspectivesand future challenges for conserv<strong>in</strong>g Grauer’s gorilla.Abstract #641. XXIV Congress of the InternationalPrimatological Society, Cancún, Mexico.Robb<strong>in</strong>s, M., J. A. Hart, F. Maisels, P. Mehlman, S. Nixonand E. A. Williamson. 2008. Gorilla ber<strong>in</strong>gei ssp. graueri.In: IUCN 2013. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.Version 2013.2. . Accessed 16March <strong>2014</strong>.Schaller, G. B. 1963. The Mounta<strong>in</strong> Gorilla: Ecology andBehavior. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL.United Nations. 2010. F<strong>in</strong>al <strong>report</strong> of the Group ofExperts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo. UnitedNations Security Council, New York.Yamagiwa, J., A. K. Basabose, K. Kaleme and T. Yumoto.2005. Diet of Grauer’s gorillas <strong>in</strong> the montane forest ofKahuzi, Democratic Republic of Congo. InternationalJournal of Primatology 26: 1345–1373.24

Madame Berthe’s Mouse LemurMicrocebus berthae Rasoloarison et al., 2000Madagascar(<strong>2012</strong>)Christoph Schwitzer, Livia Schäffler, Russell A. Mittermeier, Edward E. Louis Jr. & Matthew RichardsonMorondava River (Schmid and Kappeler 1994; Schwaband Ganzhorn 2004). There, it is known to occur <strong>in</strong>Ambadira Forest and <strong>in</strong> the Kir<strong>in</strong>dy Classified Forest,as well as <strong>in</strong> the narrow corridor connect<strong>in</strong>g the tworegions (part of the Menabe-Antimena Protected Area).It was formerly found <strong>in</strong> the Andranomena SpecialReserve as well, but has likely been extirpated there.Madame Berthe’s mouse lemur(Microcebus berthae)(Illustration: Stephen D. Nash)The species occurs <strong>in</strong> dry deciduous lowland forest(from sea level to 150 m). It feeds on fruits and gums,and relies heavily on sugary <strong>in</strong>sect excretions and animalmatter dur<strong>in</strong>g the harsh dry season (Dammhahn andKappeler 2008a). Madame Berthe’s mouse lemur hasa promiscuous mat<strong>in</strong>g system based on testis size, thepresence of sperm plugs <strong>in</strong> females’ vag<strong>in</strong>as, and sizedimorphism (Schwab 2000). While both sexes of M.berthae engage <strong>in</strong> daily periods of torpor, decreas<strong>in</strong>gtheir metabolism and body temperature to reduceenergy expenditure, they do not enter prolonged torpordur<strong>in</strong>g the dry season (Ortmann et al. 1997; Schmidet al. 2000). The most common diurnal rest<strong>in</strong>g sites ofthis species are tangles of th<strong>in</strong> branches surrounded byleaves, but they also use old nests of Mirza, tree holes,and rolled bark found <strong>in</strong> trees. Sleep<strong>in</strong>g sites are locatedfrom 2.5 to 12 m above ground. Males seem to distributetheir sleep<strong>in</strong>g sites over a larger area than females, andfemales reuse the same sleep<strong>in</strong>g site more often thanmales.Microcebus berthae, with a body mass of 31 g and ahead-body length of 9.0–9.5 cm, is the smallest of themouse lemurs (and very likely the world’s smallestprimate; Rasoloarison et al. 2000). It was discovered <strong>in</strong>the Kir<strong>in</strong>dy Forest <strong>in</strong> 1992 and was orig<strong>in</strong>ally thoughtto be Microcebus myox<strong>in</strong>us (Mittermeier et al. 2010).It is found <strong>in</strong> the central Menabe region of westernMadagascar south of the Tsiribih<strong>in</strong>a and north of the26Madame Berthe’s mouse lemur appears to be entirelysolitary. Individuals do not form sleep<strong>in</strong>g groups and,with the exception of females with young, usually sleepalone. Dur<strong>in</strong>g the night, males and females forageseparately. Home ranges, however, are extensivelyoverlapp<strong>in</strong>g, with those of the males (4.9 ha) be<strong>in</strong>g muchlarger than those of the females (2.5 ha) (Dammhahnand Kappeler 2005). The nightly path averages 4470 mfor males and 3190 m for females. Microcebus berthaeis sympatric with M. mur<strong>in</strong>us <strong>in</strong> the Kir<strong>in</strong>dy ClassifiedForest; the two seem to avoid <strong>in</strong>terspecific competitionby means of spatial segregation, thereby mak<strong>in</strong>gthe distribution of both rather patchy (Schwab and

Ganzhorn 2004; Dammhahn and Kappeler 2008b). Ingeneral, M. berthae appears to be more localized thanM. mur<strong>in</strong>us. Population densities have been estimatedat 30–180 <strong>in</strong>dividuals/km² <strong>in</strong> forest patches where itoccurs (suggest<strong>in</strong>g high localized densities), but theoverall generalized density is about 80 <strong>in</strong>dividuals/km² (Schäffler <strong>2012</strong>; Schäffler and Kappeler, <strong>in</strong> press).Population densities <strong>in</strong> Ambadira Forest tend to behigher than <strong>in</strong> Kir<strong>in</strong>dy Forest, and the population islargely conf<strong>in</strong>ed to the most suitable core areas <strong>in</strong> the<strong>in</strong>terior of the range, far from the range boundary(Schäffler <strong>2012</strong>; Schäffler and Kappeler, <strong>in</strong> press).Microcebus berthae is classified as Endangered(Andra<strong>in</strong>arivo et al. 2011). The extent of occurrencecovers less than the remnant forest cover of 710 km²(Z<strong>in</strong>ner et al. 2013), and the area of occupancy isconsiderably smaller than previously assumed basedon geographic range borders (Schäffler <strong>2012</strong>; Schäfflerand Kappeler, <strong>in</strong> press). The geographic range isseverely fragmented, and its extent of occurrence,area of occupancy, and the quality of its habitat areall decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. It is threatened ma<strong>in</strong>ly by slash-andburnagriculture and logg<strong>in</strong>g, and is particularlysensitive to anthropogenic disturbances. Sensitivityto fragmentation is evident as the species is onlyfound <strong>in</strong> core areas of extensive forests, and theregional distribution pattern reveals susceptibility tohabitat degradation and spatial avoidance of humanenvironments (Schäffler <strong>2012</strong>; Schäffler and Kappeler,<strong>in</strong> press). In 2005 the total population of this specieswas estimated at no more than 8000 adult <strong>in</strong>dividualsliv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a handful of forests (Schwab and Ganzhorn2004), most of which are at higher risk of destructionand fragmentation now than they were 10 years ago.Schäffler and Kappeler (<strong>in</strong> press) gave a higher estimateof 40,000 <strong>in</strong>dividuals, but did not discrim<strong>in</strong>ate betweenadults and juveniles. Pressure on the forests of thecentral Menabe is strong, and deforestation cont<strong>in</strong>ueson a large scale. To quantify recent forest loss, Z<strong>in</strong>ner etal. (2013) used a series of satellite images (1973–2010)for estimat<strong>in</strong>g annual deforestation rates. The overallrate was 0.67%, but it accelerated to over 1.5% dur<strong>in</strong>gcerta<strong>in</strong> periods, with a maximum of 2.55% per yearbetween 2008 and 2010. Not all areas <strong>in</strong> the forest blockof the central Menabe were affected similarly. Areassurround<strong>in</strong>g exist<strong>in</strong>g clear<strong>in</strong>gs showed the highest lossesof largely undisturbed forest. If deforestation cont<strong>in</strong>uesat the same rate as dur<strong>in</strong>g the last years, 50% of the 1973forest cover will be gone with<strong>in</strong> the next 11–37 years(Z<strong>in</strong>ner et al. 2013). Madame Berthe’s mouse lemur isnot be<strong>in</strong>g kept <strong>in</strong> captivity (ISIS <strong>2014</strong>).27A conservation action plan for Kir<strong>in</strong>dy-Ambadira(Central Menabe) was published recently (Markolf et al.2013) as part of the IUCN Lemur Conservation Strategy2013–2016 (Schwitzer et al. 2013a). The conservationobjectives for this area as laid out <strong>in</strong> the action plan areadditional ecological research and threat analyses of theendemic fauna; improved environmental education; andimmediate-term threat mitigation actions such as the<strong>in</strong>troduction of short-cycle chicken farm<strong>in</strong>g. MadameBerthe’s mouse lemur is also a priority species for ex situconservation measures (Schwitzer et al. 2013b).ReferencesAndra<strong>in</strong>arivo, C., V. N. Andriahol<strong>in</strong>ir<strong>in</strong>a, A. T. C.Feistner, T. Felix, J. U. Ganzhorn, N. Garbutt, C.Golden, W. B. Konstant, E. E. Louis Jr., D. M. Meyers,R. A. Mittermeier, A. Perieras, F. Pr<strong>in</strong>cee, J. C.Rabarivola, B. Rakotosamimanana, Rasamimanana, H.,J. Ratsimbazafy, G. Raveloar<strong>in</strong>oro, A. Razafimanantsoa,Y. Rumpler, C. Schwitzer, R. Sussman, U. Thalmann,L. Wilmé and P. C. Wright. 2011. Microcebus berthae.In: IUCN 2013. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.Version 2013.2. . Accessed 17March <strong>2014</strong>.Dammhahn, M. and P. M. Kappeler. 2005. Social systemof Microcebus berthae, the world’s smallest primate.International Journal of Primatology 26: 407–435.Dammhahn, M. and P. M. Kappeler. 2008a. Comparativefeed<strong>in</strong>g ecology of sympatric Microcebus berthae andM. mur<strong>in</strong>us. International Journal of Primatology 29:1567–1589.Dammhahn, M. and P. M. Kappeler. 2008b. Small-scalecoexistence of two mouse lemur species (Microcebusberthae and M. mur<strong>in</strong>us) with<strong>in</strong> a homogeneouscompetitive environment. Oecologia 157: 473–483.ISIS. <strong>2014</strong>. Zoological Information ManagementSystem (ZIMS) version 1.7, released 27 January <strong>2014</strong>.ISIS, Apple Valley, MN.Markolf M., P. M. Kappeler, R. Lewis and I. A. Y. Jacky.2013. Kir<strong>in</strong>dy–Ambadira (Central Menabe). In: Lemursof Madagascar: A Strategy for Their Conservation 2013–2016, C. Schwitzer et al. (eds.), pp.113–115. IUCN SSCPrimate Specialist Group, Bristol Conservation andScience Foundation, and Conservation International,Bristol, UK.