On the Hoof - Livestock Trade in Darfur

On the Hoof - Livestock Trade in Darfur

On the Hoof - Livestock Trade in Darfur

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>On</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Hoof</strong><strong>Livestock</strong> <strong>Trade</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong>

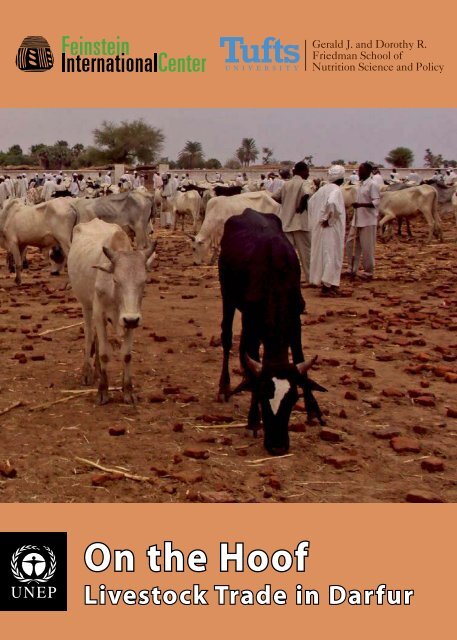

http://unep.org/Sudan/First published <strong>in</strong> September 2012 by <strong>the</strong> United Nations Environment Programme© 2012, United Nations Environment ProgrammeUnited Nations Environment ProgrammeP.O. Box 30552, Nairobi, KENYATel: +254 (0)20 762 1234Fax: +254 (0)20 762 3927E-mail: uneppub@unep.orgWeb: http://www.unep.orgThis publication may be reproduced <strong>in</strong> whole or <strong>in</strong> part and <strong>in</strong> any form for educational or non-profit purposes without specialpermission from <strong>the</strong> copyright holder provided acknowledgement of <strong>the</strong> source is made. No use of this publication may be made forresale or for any o<strong>the</strong>r commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission <strong>in</strong> writ<strong>in</strong>g from UNEP. The contents of this volumedo not necessarily reflect <strong>the</strong> views of UNEP, or contributory organizations. The designations employed and <strong>the</strong> presentations do notimply <strong>the</strong> expressions of any op<strong>in</strong>ion whatsoever on <strong>the</strong> part of UNEP or contributory organizations concern<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> legal status ofany country, territory, city or area or its authority, or concern<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.Report authors: Margie Buchanan-Smith and Abdul Jabbar Abdulla Fadul,with Abdul Rahman Tahir and Yacob AkliluCover image: © <strong>Darfur</strong> Development and Reconstruction Agency:Fora Boranga livestock market, West <strong>Darfur</strong>Report layout: Bridget SnowCover design: Matija PotocnikMaps: UNOCHA, SudanPr<strong>in</strong>ted by: New Life Pr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g Press, KhartoumUNEP promotesenvironmentally sound practicesglobally and <strong>in</strong> its own activities. Thispublication is pr<strong>in</strong>ted on recycled paperus<strong>in</strong>g eco-friendly practices. Our distributionpolicy aims to reduce UNEP’s carbon footpr<strong>in</strong>t.

<strong>On</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Hoof</strong><strong>Livestock</strong> <strong>Trade</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong>

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThe authors are extremely grateful to <strong>the</strong> many traders, government officials, and o<strong>the</strong>rstakeholders whom we <strong>in</strong>terviewed, often at length, for <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation <strong>the</strong>y provided and for<strong>the</strong>ir support and cooperation. Anita Yeomans did an excellent job sourc<strong>in</strong>g and review<strong>in</strong>grelevant literature on <strong>the</strong> livestock trade and livestock production <strong>in</strong> Sudan and beyond. Dr.Abdelatif Ahmed Mohamed Ijaimi provided access to <strong>in</strong>valuable data and analysis of <strong>the</strong> livestocktrade at <strong>the</strong> national level. Insights <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> dynamics of <strong>in</strong>dividual markets <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong> were madepossible through <strong>the</strong> tireless work of a team of local researchers. Youssif Abaker was an excellentnote-taker at <strong>the</strong> analysis workshop with <strong>the</strong> local researchers, and Edward Howat helped withpreparation of <strong>the</strong> graphs. The authors would like to thank a number of peer reviewers whocommented on an earlier draft of this report: Roy Behnke, Helen Young, Magda Nassef, OmerHassan El Dirani, Saverio Krätli, Jack Van Holst Pelekaan, and Brendan Bromwich. The study’sconclusions and recommendations were extensively discussed with Salih Abul Mageed El Douma,Omer Hassan El Dirani, Youssif El Tayeb, Afaf Rahim, and Magda Nassef, and were sharpened as aresult. The <strong>Darfur</strong> Development and Reconstruction Agency has facilitated <strong>the</strong> study <strong>in</strong> manyways, from logistical support to comment<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong> analysis and advis<strong>in</strong>g on dissem<strong>in</strong>ation.Thanks are also due to Tamreez Amirzada, UNOCHA Khartoum for <strong>the</strong> production of <strong>the</strong> maps.F<strong>in</strong>ally, special thanks to Helen Young for her cheerful and unfail<strong>in</strong>g support and encouragementto this study, and to Magda Nassef and <strong>the</strong> UNEP team for all <strong>the</strong>ir support <strong>in</strong> Sudan.This study was funded by UKAID under <strong>the</strong>ir support to UNEP’s Sudan IntegratedEnvironment Project.4

9. <strong>Trade</strong> <strong>in</strong> hides and sk<strong>in</strong>s............................................................................. 5010. Conclusions and recommendations.............................................................. 5210.1 Conclusions....................................................................................................... 5210.2 Recommendations............................................................................................. 54Acronyms ...................................................................................................... 57References...................................................................................................... 58Annex 1 Research team carry<strong>in</strong>g out <strong>the</strong> study.................................................. 61Annex 2 Analysis of trad<strong>in</strong>g costs <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong>’s livestock trade................................ 636

Executive SummaryThis study set out to understand what hashappened to <strong>the</strong> livestock trade <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> greater<strong>Darfur</strong> region dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> conflict years: how it hasresponded to <strong>the</strong> constantly shift<strong>in</strong>g conflictdynamics s<strong>in</strong>ce 2003, how it has adapted, and towhat extent (if at all) it has recovered. It also setout to identify how <strong>the</strong> livestock trade can besupported <strong>in</strong> order to better susta<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> livelihoodsof different groups <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong>, both while<strong>the</strong> conflict cont<strong>in</strong>ues and <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> longer term tosupport <strong>the</strong> eventual recovery of <strong>Darfur</strong>’s economyand to contribute to <strong>the</strong> national economy. Itis estimated that <strong>Darfur</strong>’s livestock account forbetween one-quarter and one-third of Sudan’slivestock resources post-secession.Sudan’s national export trade <strong>in</strong> livestock andmeat, oriented towards <strong>the</strong> Middle East, is heavilydependent on a small number of markets—SaudiArabia, Egypt, and Jordan—mak<strong>in</strong>g it vulnerableto chang<strong>in</strong>g trade regimes <strong>in</strong> those markets and tolos<strong>in</strong>g its market share to competitor export<strong>in</strong>gcountries that have more sophisticated productionand market<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>frastructure, especially as welfare,hygiene, and disease control regulations becomestricter <strong>in</strong> livestock-import<strong>in</strong>g countries. Dur<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> years of petroleum wealth <strong>in</strong> Sudan, <strong>the</strong>livestock sector received ra<strong>the</strong>r little attention <strong>in</strong>terms of government policy and <strong>in</strong>vestment,although this now seems to be chang<strong>in</strong>g, withrenewed government <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> livestocksector and <strong>the</strong> role it can play <strong>in</strong> future economicgrowth <strong>in</strong> Sudan post-secession.<strong>Darfur</strong>’s livestock trade was immediately andbadly affected by <strong>the</strong> conflict. Early on, <strong>in</strong> 2003–4,when large numbers of rural households weredisplaced, loot<strong>in</strong>g of livestock was widespread.Prices plummeted as distress sales of livestocksoared, and many of <strong>the</strong> looted animals were soldquickly and locally, usually for meat consumption.Many livestock traders went out of bus<strong>in</strong>ess and/or were bankrupted <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>se early years; o<strong>the</strong>rsswitched to trade <strong>in</strong> less-risky commodities.Large-scale livestock traders from Omdurmanwithdrew from <strong>Darfur</strong>’s livestock markets becauseof <strong>in</strong>security and <strong>the</strong> risks associated with trekk<strong>in</strong>ganimals on <strong>the</strong> hoof, effectively transferr<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> risk of trekk<strong>in</strong>g livestock to central Sudan tosmaller-scale <strong>Darfur</strong>i traders. By March 2011,<strong>the</strong>re were signs of limited recovery <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong>’slivestock trade as some large-scale traders fromOmdurman returned to <strong>the</strong> region, especially toSouth <strong>Darfur</strong>, but this recovery is fragile andcould be threatened by shift<strong>in</strong>g conflict dynamics.All traders <strong>in</strong>terviewed for this study recounteda contraction <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> volume of livestock tradeddur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> conflict years, of at least 50%, sometimesmore, and a deteriorat<strong>in</strong>g quality of livestockbrought to <strong>the</strong> market compared with <strong>the</strong>pre-conflict years. Most secondary livestockmarkets have contracted <strong>in</strong> terms of volume ofsales, and many primary village markets <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong>have been closed s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> conflict began. Therehas been a sharp fall <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> number of livestocktraders operat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong>, as well as an ethnicconcentration of livestock traders dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>conflict years, reported <strong>in</strong> all markets <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong>visited for this study. In some parts of <strong>the</strong> region,agreements have been forged between o<strong>the</strong>rwisehostile groups to secure access to trade where<strong>the</strong>re are mutual livelihood and economic <strong>in</strong>terests,show<strong>in</strong>g how trade can be a bridge torebuild<strong>in</strong>g relationships between o<strong>the</strong>rwise hostilegroups, and of <strong>the</strong> benefits to all concerned and to<strong>the</strong> economy when this succeeds.<strong>Livestock</strong> traders have adapted to <strong>the</strong> conflictenvironment by switch<strong>in</strong>g to more secure yetlonger and more circuitous trekk<strong>in</strong>g routes. Theyhave reduced <strong>the</strong> number of animals mov<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> as<strong>in</strong>gle herd to reduce exposure to loot<strong>in</strong>g andnow employ armed guards to accompany <strong>the</strong>herds. Each of <strong>the</strong>se adaptations has substantially<strong>in</strong>creased <strong>the</strong> transport costs per head of livestock.Overall, trad<strong>in</strong>g costs have soared dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>conflict years, ris<strong>in</strong>g by 100 to 700% comparedwith 2002, not only due to <strong>the</strong> hir<strong>in</strong>g of armedguards for protection but also due to <strong>the</strong> paymentof fees at numerous checkpo<strong>in</strong>ts on many routes,and due to substantially <strong>in</strong>creased formal taxes. AJune 2012 • ON THE HOOF: The <strong>Livestock</strong> <strong>Trade</strong> In <strong>Darfur</strong> 7

major grievance amongst livestock traders is that<strong>the</strong>y see little benefit from pay<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>flated taxes <strong>in</strong>terms of improved market <strong>in</strong>frastructure orservices. Instead, much of <strong>the</strong> market <strong>in</strong>frastructure<strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong> and along <strong>the</strong> trekk<strong>in</strong>g routesappears to be deteriorat<strong>in</strong>g.No livestock traders <strong>in</strong>terviewed for this study<strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong> had accessed formal credit, a majorconstra<strong>in</strong>t to livestock trad<strong>in</strong>g, as <strong>the</strong> amount ofcapital needed to trade has soared dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>conflict years. Although <strong>the</strong> livestock market<strong>in</strong>gsystem <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong> and Omdurman has longdepended upon <strong>in</strong>formal credit arrangements,<strong>the</strong>se carry <strong>the</strong>ir own risks, and some traders havegone out of bus<strong>in</strong>ess when o<strong>the</strong>rs have defaultedon payments on credit.Cross-border trade with Libya, Chad, andCAR has long been a feature of <strong>Darfur</strong>’s livestocktrade, much of it <strong>in</strong>formal. Although Egypt isofficially Sudan’s most important market for <strong>the</strong>export of camels, <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong> <strong>the</strong> export trade toLibya is currently preferred, ma<strong>in</strong>ly because of <strong>the</strong><strong>in</strong>formality of <strong>the</strong> trade and lack of regulation.Recent political upheavals <strong>in</strong> both Egypt andLibya temporarily disrupted <strong>the</strong> camel trade,although it has s<strong>in</strong>ce resumed. Cross-border trade<strong>in</strong> livestock between West <strong>Darfur</strong> and Chad wasalso disrupted by political hostilities between <strong>the</strong>respective governments, but has resumed s<strong>in</strong>ce2010. There has been some shift <strong>in</strong> market activitydur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> conflict years away from <strong>the</strong> longdistancetrade of animals, with its associated risks,to <strong>the</strong> local slaughter of livestock to meet <strong>Darfur</strong>’sgrow<strong>in</strong>g demand for meat. The rapid and distortedprocess of urbanization <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong> dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>conflict years has triggered an emerg<strong>in</strong>g andimportant local meat <strong>in</strong>dustry.Despite <strong>Darfur</strong>’s prom<strong>in</strong>ence as one ofSudan’s most important livestock-produc<strong>in</strong>g areasand as a major contributor to livestock exports,<strong>the</strong> region has only one poorly function<strong>in</strong>gslaughterhouse, located <strong>in</strong> Nyala. Plans to constructa new abattoir <strong>in</strong> Nyala are progress<strong>in</strong>g veryslowly, and an abattoir constructed <strong>in</strong> Gene<strong>in</strong>a hasnever been completed, yet such facilities couldplay a critical role <strong>in</strong> stimulat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Darfur</strong>’s livestocktrade and <strong>in</strong> efficiency ga<strong>in</strong>s if livestock no longerhad to be trekked on <strong>the</strong> hoof to Omdurman,especially dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> dry season.<strong>Trade</strong> <strong>in</strong> hides and sk<strong>in</strong>s, an importantby-product of <strong>the</strong> livestock trade, has flourished <strong>in</strong><strong>Darfur</strong> dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> conflict years, ma<strong>in</strong>ly focusedon West Africa. Most of <strong>the</strong> hides and sk<strong>in</strong>s areexported directly, for example through El Fasherand Gene<strong>in</strong>a, and transported overland.Although <strong>the</strong>re are some such positive trendsto report, <strong>the</strong> overall picture that emerges is ofmany <strong>in</strong>efficiencies <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> way that <strong>Darfur</strong>’slivestock are currently traded, exacerbated by <strong>the</strong>much-<strong>in</strong>creased trad<strong>in</strong>g costs associated with <strong>the</strong>conflict, which fur<strong>the</strong>r reduces <strong>the</strong> competitivenessof Sudan’s livestock exports. The livestocksector and livestock trade will be critical to <strong>the</strong>eventual recovery of <strong>Darfur</strong>’s economy and to <strong>the</strong>recovery of rural livelihoods. Plann<strong>in</strong>g on how tosupport such a recovery, as <strong>in</strong>clusively as possible,can start now.8

SUDAN: <strong>Darfur</strong> - Markets covered under this studySeptember 2012LibyaEgyptChadSudanEritreaEthiopiaC.A.R.South SudanNORTH DARFUREl MalhaCHADEl Gene<strong>in</strong>aSaraf Omra!El FasherWEST DARFURZal<strong>in</strong>geiTeraijNORTHKORDOFANFora BorangaCENTER DARFURSilgoUmlabbasaNyalaSOUTH DARFURMarkundiAssalayaEd DaienUmm DukhnRehaid Al BerdiRajajAboriEl TomatEl FurdosAbujabra AbumatarigAbusenaidraSOUTHKORDOFANCAREAST DARFURLEGENDMarkets coveredPrimary RoadSecondary RoadState boundaryInternational boundaryAbyei AreaUndeterm<strong>in</strong>ed boundarySOUTH SUDAN30 kmCreation date: 11 September 2012 Sources: Boundary(CBS,IMWG), Settlement(OCHA).Map created by OCHAThe boundaries and names shown and <strong>the</strong> designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by <strong>the</strong> United Nations.F<strong>in</strong>al boundary between <strong>the</strong> Republic of Sudan and <strong>the</strong> Republic of South Sudan has not yet been determ<strong>in</strong>ed. F<strong>in</strong>al status of <strong>the</strong> Abyei area is not yet determ<strong>in</strong>ed.June 2012 • ON THE HOOF: The <strong>Livestock</strong> <strong>Trade</strong> In <strong>Darfur</strong> 9

1. Introduction1.1 Why this study?<strong>Livestock</strong> is one of <strong>Darfur</strong>’s ma<strong>in</strong> economicassets and a central component of most rurallivelihoods. It is estimated that <strong>the</strong> region accountsfor one-quarter to one-third of Sudan’s livestockproduction. 1 The greater <strong>Darfur</strong> region has longbeen a major exporter of camels, cattle, and sheep,while goats are mostly traded and consumedlocally. The outbreak of conflict <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong> <strong>in</strong> 2003has badly affected <strong>the</strong> livestock sector. There waswidespread loot<strong>in</strong>g of livestock <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> early yearsof <strong>the</strong> conflict, affect<strong>in</strong>g traders as well asproducers, as so much of <strong>the</strong> livestock trade<strong>in</strong>volves trekk<strong>in</strong>g animals over long distances. Thisbecame a risky bus<strong>in</strong>ess. As <strong>the</strong> conflict cont<strong>in</strong>ued,o<strong>the</strong>r constra<strong>in</strong>ts have affected <strong>the</strong> livestock trade;for example, a heavy taxation burden, althoughsome trad<strong>in</strong>g opportunities have also opened up.The significance of <strong>the</strong> livestock sector to <strong>Darfur</strong>’seconomy at <strong>the</strong> macro level, and to livelihoods at<strong>the</strong> micro level, means that recovery of <strong>the</strong>livestock sector and of livestock trade will be keyto <strong>the</strong> long-term economic recovery of <strong>the</strong>region. S<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> secession of South Sudan and<strong>the</strong> loss of oil revenue, <strong>the</strong> livestock sector is of<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g importance to Sudan’s economy at <strong>the</strong>national level.The purpose of this study is to understandwhat has happened to <strong>the</strong> livestock trade <strong>in</strong><strong>Darfur</strong> dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> conflict years, and to identifyhow trade can be supported. The specificobjectives are, first, track<strong>in</strong>g how <strong>the</strong> livestocktrade has been impacted by <strong>the</strong> conflict <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong>s<strong>in</strong>ce 2003, how trade has adapted, and <strong>the</strong> extentto which it has recovered, <strong>in</strong> order to betterunderstand <strong>the</strong> impact on <strong>the</strong> livelihoods ofdifferent groups <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong> and <strong>the</strong> implications for<strong>Darfur</strong>’s future. The second objective is to identifyways <strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong> livestock trade can besupported to better susta<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> livelihoods ofdifferent groups <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong> while <strong>the</strong> conflictcont<strong>in</strong>ues, and, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> longer term, to support <strong>the</strong>eventual recovery of <strong>Darfur</strong>’s economy, andcontribute to <strong>the</strong> economy at <strong>the</strong> national level. Itbuilds on earlier studies dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> conflict yearsthat have looked at <strong>the</strong> livestock sector andlivestock trade. 2The study is part of UNEP’s “SudanIntegrated Environment Project” (SIEP). Led by<strong>the</strong> Fe<strong>in</strong>ste<strong>in</strong> International Center (FIC) of TuftsUniversity, <strong>the</strong> study feeds <strong>in</strong>to Tufts’ overallresearch program on livelihoods <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong> thatbegan <strong>in</strong> 2004. Carried out over a twelve-monthperiod between February 2011 and February2012, this <strong>in</strong>-depth study of <strong>the</strong> livestock tradecomplements ongo<strong>in</strong>g monthly monitor<strong>in</strong>g oftrade and markets that <strong>the</strong> non-governmentalorganization (NGO), <strong>the</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong> Developmentand Reconstruction Agency (DRA), is manag<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> North and West <strong>Darfur</strong> through localcommunity-based organizations (CBOs) withadvisory <strong>in</strong>put from Tufts University. Toge<strong>the</strong>r,both of <strong>the</strong>se market research <strong>in</strong>itiatives aim todeepen understand<strong>in</strong>g and analysis of how <strong>the</strong>conflict is impact<strong>in</strong>g on trade and thus to identifyhow livelihoods can be supported through market<strong>in</strong>terventions and how market <strong>in</strong>frastructure canbe ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed through <strong>the</strong> conflict years to speed<strong>Darfur</strong>’s eventual economic recovery when <strong>the</strong>reis greater peace and stability. These <strong>in</strong>itiatives alsoaim to identify peace-build<strong>in</strong>g opportunitiesthrough trade. This livestock trade studycomplements a parallel <strong>in</strong>itiative by <strong>the</strong> Fe<strong>in</strong>ste<strong>in</strong>International Center on pastoralism, which aimsto promote understand<strong>in</strong>g of pastoralist livelihoodsystems among local, national, and <strong>in</strong>ternationalstakeholders and to streng<strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> capacity ofpastoralist leaders, organizations, and o<strong>the</strong>radvocates to articulate <strong>the</strong> rationale for pastoralism<strong>in</strong> Sudan. The livestock trade study <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong> and<strong>the</strong> project on pastoralism are be<strong>in</strong>g carried out <strong>in</strong>close collaboration, both be<strong>in</strong>g components of <strong>the</strong>environment and livelihoods <strong>the</strong>me of <strong>the</strong> SIEP.1Based on 2011 figures from <strong>the</strong> M<strong>in</strong>istry of Animal Resources, Fisheries and Range, for Sudan after <strong>the</strong> secession of SouthSudan.2See, for example, Young et al. (2005), El Dukheri et al. (2004).10

Susta<strong>in</strong>able livestock production is critical tolivestock trade, domestically and <strong>in</strong>ternationally,and thus to economic growth. Well-managed andsupported by clear and coherent policies, both cancontribute to susta<strong>in</strong>able natural resourcemanagement. Poorly managed, both canunderm<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> susta<strong>in</strong>able management of naturalresources and be destructive. Indeed, whereo<strong>the</strong>rwise hostile groups have overcome <strong>the</strong>irdifferences <strong>in</strong> order to cont<strong>in</strong>ue livestock trad<strong>in</strong>g,<strong>the</strong>re may be potential to extend thiscollaboration to <strong>the</strong> co-management of naturalresources.This report presents <strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs of <strong>the</strong>livestock trade study. It beg<strong>in</strong>s with an overviewof <strong>the</strong> livestock trade <strong>in</strong> Sudan, its significance to<strong>the</strong> economy, and provides a description of <strong>the</strong>evolv<strong>in</strong>g policy context—section 2. Section 3describes <strong>the</strong> livestock trade <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong> pre-conflictand provides an overview of how <strong>the</strong> livestocktrade has contracted dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> conflict years.Section 4 analyzes how market activity has shifted<strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong> <strong>in</strong> response to <strong>the</strong> conflict, both <strong>in</strong>terms of <strong>the</strong> market network and <strong>in</strong> terms oflivestock trade routes, draw<strong>in</strong>g on primary datacollected dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> study. The chang<strong>in</strong>g profileof livestock traders <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong> is presented <strong>in</strong>Section 5, which shows <strong>the</strong> concentration ofmarket power dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> conflict years. Section 6shows how <strong>the</strong> costs of trad<strong>in</strong>g have soared s<strong>in</strong>ce2003 based on an analysis of data collected dur<strong>in</strong>g2011. Section 7 draws out <strong>the</strong> implications of <strong>the</strong>study’s f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs for livestock production, andpresents a couple of hypo<strong>the</strong>ses about howlivestock production and ownership <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong>appears to have changed dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> conflict years,accord<strong>in</strong>g to feedback from traders and o<strong>the</strong>rstakeholders <strong>in</strong>terviewed dur<strong>in</strong>g 2011. Section 8assesses how cross-border livestock trad<strong>in</strong>g from<strong>Darfur</strong> has been affected dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> conflict yearsand shows <strong>the</strong> grow<strong>in</strong>g significance of domesticmeat consumption with<strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong>. <strong>Trade</strong> <strong>in</strong> hidesand lea<strong>the</strong>r from <strong>Darfur</strong> appears to be grow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>importance; this is reviewed <strong>in</strong> Section 9. F<strong>in</strong>ally,section 10 presents <strong>the</strong> conclusions from <strong>the</strong> studyand makes recommendations about how <strong>the</strong>livestock trade <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong> can be supported <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>immediate and longer-term future.1.2 MethodologyThis study builds on previous research <strong>in</strong>to<strong>the</strong> livestock trade <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong> and how it has beenimpacted by conflict, <strong>in</strong> particular “LivelihoodsUnder Siege,” (Young et al, 2005), whichprovided an account and analysis of <strong>the</strong> earlyimpact of <strong>the</strong> conflict on <strong>the</strong> livestock market, anda subsequent study carried out <strong>in</strong> 2007 <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong>’sstate capitals: “Adaptation and Devastation,”(Buchanan-Smith and Fadul, 2008) which beganto show how <strong>the</strong> livestock trade had adapted fouryears <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> conflict. This most recent studyprovides an overview of how n<strong>in</strong>e years ofwidespread conflict have impacted on <strong>the</strong>livestock trade, with a particular focus on <strong>the</strong> stateof <strong>the</strong> livestock trade <strong>in</strong> 2011.The first step was draw<strong>in</strong>g up a set of researchquestions to guide <strong>the</strong> study. See Box 1.Subsequent steps <strong>in</strong> carry<strong>in</strong>g out <strong>the</strong> study were asfollows:1. A review of secondary documentation onlivestock trad<strong>in</strong>g, pr<strong>in</strong>cipally from Sudanbut also more broadly, for example, from<strong>the</strong> Horn of Africa, to ensure this studyprovides added value by build<strong>in</strong>g onprevious work and exist<strong>in</strong>g knowledge.2. A period of fieldwork to collect primarydata <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong>’s state capitals: El Fasher,El Gene<strong>in</strong>a, and Nyala. This was carriedout <strong>in</strong> March 2011 by four seniorresearchers, each with exist<strong>in</strong>g knowledgeand experience of <strong>the</strong> livestock trade <strong>in</strong><strong>Darfur</strong>. (See Annex 1). Key <strong>in</strong>formant<strong>in</strong>terviews were conducted with differenttypes of livestock traders <strong>in</strong> each marketvisited, purposively selected to berepresentative of <strong>the</strong> range of traderscurrently engaged <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> livestock trade.Interviews were also carried out withgovernment officials who adm<strong>in</strong>ister <strong>the</strong>livestock market and collect taxes, withherders employed by traders on <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>livestock trad<strong>in</strong>g routes throughout andbeyond <strong>Darfur</strong>, and with o<strong>the</strong>rstakeholders and resource people,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g academics, who have data and<strong>in</strong>formation about <strong>the</strong> sector.June 2012 • ON THE HOOF: The <strong>Livestock</strong> <strong>Trade</strong> In <strong>Darfur</strong> 11

3. A review of official statistics andgovernment policy on livestock trad<strong>in</strong>g wascarried out by a national consultant <strong>in</strong>Khartoum, <strong>in</strong> order to identify trends andto understand <strong>the</strong> macro policyenvironment with<strong>in</strong> which <strong>Darfur</strong>’slivestock trade is operat<strong>in</strong>g (Ijaimi, 2011).4. A second period of more detailed fieldwork<strong>in</strong> 14 markets across <strong>the</strong> three <strong>Darfur</strong>states was completed between April andJune 2011. (See <strong>the</strong> map for marketsresearched dur<strong>in</strong>g this study). Ten localresearchers were recruited to carry outthis phase of <strong>the</strong> study, most of whomwere agricultural officers and assistant vets<strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong>, familiar with <strong>the</strong>ir local marketand hav<strong>in</strong>g strong contacts with livestocktraders and producers. See Annex 1. Thisteam of local researchers was tra<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> a2-day workshop <strong>in</strong> El Fasher <strong>in</strong> March2011, provided with questionnaires and ashort report form to complete, and metaga<strong>in</strong> for a 3-day analysis workshop <strong>in</strong>Khartoum <strong>in</strong> June 2011.5. Interviews with livestock traders andexporters <strong>in</strong> Omdurman were carried out<strong>in</strong> January/February 2012.6. The f<strong>in</strong>al analysis of all <strong>the</strong> data andmaterials ga<strong>the</strong>red was carried out <strong>in</strong>February/March 2012.This study relies on both quantitative andqualitative data, some of it drawn from secondarysources, while much of it is primary data collecteddur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> respective periods of field work.Quantitative data cover <strong>in</strong>dicators such as prices,trad<strong>in</strong>g costs, and estimates of numbers of tradersand numbers of livestock traded. We have<strong>in</strong>dicated where <strong>the</strong>se are estimates, and <strong>the</strong>refore<strong>the</strong> numbers need to be treated with caution.Qualitative data cover issues such as trade routes,trader profiles, and evidence of geographical shifts<strong>in</strong> market activity. In order to capture <strong>the</strong> impactof <strong>the</strong> conflict on trade, <strong>in</strong>terviewees were askedto make comparisons between <strong>the</strong> livestock trade<strong>in</strong> 2011 and <strong>in</strong> 2002, before conflict <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong> waswidespread. These comparisons often rely onrecall, as reliable written records are scarce.Carry<strong>in</strong>g out primary research <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> current<strong>Darfur</strong> environment is challeng<strong>in</strong>g and subject tomany constra<strong>in</strong>ts. Pr<strong>in</strong>cipal amongst <strong>the</strong>se are:(1) <strong>in</strong>security and restricted access to anumber of markets with<strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong>: a teamof local researchers based <strong>in</strong> each of <strong>the</strong>semarkets was <strong>the</strong>refore recruited andtra<strong>in</strong>ed to overcome this constra<strong>in</strong>t;(2) <strong>the</strong> dynamic and fluid situation <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong>,which means that data and analysis canquickly become outdated: where possible<strong>the</strong> team has done follow-up monitor<strong>in</strong>gto ensure that early f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs are stillrelevant or to update <strong>the</strong>m, but <strong>the</strong>rapidly-chang<strong>in</strong>g environment should beborne <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d when consider<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs of this study;(3) traders be<strong>in</strong>g suspicious of questions and<strong>in</strong>-depth <strong>in</strong>terviews and <strong>the</strong>reforereluctant to participate. The team usedlocal networks and trusted personalrelationships to overcome this constra<strong>in</strong>t;(4) at <strong>the</strong> national level, <strong>the</strong> lack of officialstatistics on some aspects of livestocktrad<strong>in</strong>g, for example, <strong>the</strong> relative share ofdomestic versus <strong>in</strong>ternational trade andnumbers of livestock exported from<strong>Darfur</strong>, has been a constra<strong>in</strong>t. Also, officialstatistics prior to July 2011 refer to Sudan<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g South Sudan, although thisstudy is be<strong>in</strong>g completed after secessionand <strong>the</strong>refore makes recommendations for<strong>the</strong> newly def<strong>in</strong>ed (nor<strong>the</strong>rn) Sudan. Thelack of official statistics is even more acuteat <strong>the</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong> level, constra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>quantitative analysis that was possible.In carry<strong>in</strong>g out a study of this k<strong>in</strong>d, it hasbeen important to generate support for <strong>the</strong> workfrom government and o<strong>the</strong>r stakeholders: <strong>the</strong> factthat it has been carried out at a time whengovernment is giv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>creased attention to <strong>the</strong>livestock sector and its potential as a source ofeconomic growth has <strong>in</strong>tensified <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong>, andsupport for, <strong>the</strong> work.The study aims to address an ambitious list ofresearch questions. Where it was not possible toprovide conclusive answers, <strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs are posedas hypo<strong>the</strong>ses that require fur<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>vestigation; forexample, <strong>in</strong> response to question 3 <strong>in</strong> Box 1 on<strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> producers of livestock currently traded<strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong>.12

Box 1.Research questions that <strong>the</strong> study sets out to answer(1) Overall, how has <strong>the</strong> livestock trade been affected by, and how has it responded to, <strong>the</strong>constantly shift<strong>in</strong>g dynamics of conflict <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong> s<strong>in</strong>ce 2003? How has it adapted, and towhat extent (if at all) has <strong>the</strong> livestock trade recovered?(2) Specifically, how has <strong>the</strong> volume and value of <strong>the</strong> livestock trade <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong> been affectedby <strong>the</strong> conflict, and how has this impacted on livestock exports from Sudan? How doesthis compare with o<strong>the</strong>r factors affect<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> livestock trade <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> last decade?(3) Who are <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> producers of livestock currently traded <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong>, and how does thiscompare with <strong>the</strong> pre-conflict years?(4) How has <strong>the</strong> market cha<strong>in</strong> for livestock been affected by <strong>the</strong> conflict, from producers toconsumers/exporters?(5) How has <strong>the</strong> concentration of market power amongst different livestock traders changeddur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> conflict years; for example, geographically and ethnically? Who trades withwhom? What determ<strong>in</strong>es access to <strong>the</strong> livestock market (<strong>in</strong> order to become a trader),and how has this been impacted by <strong>the</strong> conflict context?(6) How have trad<strong>in</strong>g routes changed throughout <strong>the</strong> period of <strong>the</strong> conflict, and why? Whatdoes this tell us about security and conflict dynamics?(7) How have trad<strong>in</strong>g and transaction costs <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> livestock trade been affected by <strong>the</strong>conflict? What are <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>creased risks, and who bears <strong>the</strong> cost of those risks? What canwe learn from an analysis of trad<strong>in</strong>g costs about current <strong>in</strong>efficiencies <strong>in</strong> livestock trad<strong>in</strong>gand how <strong>the</strong>se could be resolved?(8) How significant is cross-border trade <strong>in</strong> livestock from <strong>Darfur</strong> (eg., <strong>in</strong>to Chad, CentralAfrican Republic, and Libya), formally and <strong>in</strong>formally, and who is <strong>in</strong>volved?(9) What are <strong>the</strong> implications of all of <strong>the</strong> above for <strong>the</strong> livelihoods of different groups <strong>in</strong><strong>Darfur</strong>, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g current and former (ie., pre-conflict) pastoralists, agro-pastoralists, andfarmers?(10) What are <strong>the</strong> implications for all of <strong>the</strong> above for susta<strong>in</strong>able livestock production andtrade <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong>’s economy <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> future?The livestock trade <strong>in</strong> Sudan is almost entirelydom<strong>in</strong>ated by men. Therefore, this study hasma<strong>in</strong>ly been carried out through <strong>in</strong>terview<strong>in</strong>gmale traders. Because of lack of access to livestockproducers, few women were <strong>in</strong>terviewed as key<strong>in</strong>formants, which is clearly a gap. The commercial<strong>in</strong>volvement of women <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> livestock sector isma<strong>in</strong>ly <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> trade of livestock products, such asmilk and lea<strong>the</strong>r. <strong>Trade</strong> <strong>in</strong> hides and sk<strong>in</strong>s has beenexplored briefly, but it was beyond <strong>the</strong> resourcesof <strong>the</strong> study to carry out a full analysis of trade <strong>in</strong>livestock products. This is a gap which needs to befilled for a truly gendered analysis of <strong>the</strong> trade <strong>in</strong>livestock and associated products.June 2012 • ON THE HOOF: The <strong>Livestock</strong> <strong>Trade</strong> In <strong>Darfur</strong> 13

2. An overview of Sudan’s livestock trade and <strong>the</strong> policy context2.1 The significance of livestock production<strong>in</strong> SudanS<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> discovery of oil <strong>in</strong> Sudan <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>mid-1990s, petroleum has been hugely importantto Sudan’s economy. As a result, Sudan enjoyedone of <strong>the</strong> highest growth rates <strong>in</strong> Africa between2000 and 2009, of almost 8% p.a. But even dur<strong>in</strong>gthis period, agriculture was significantly moreimportant to GDP (Gross Domestic Product) thanpetroleum, and much of this was due to <strong>the</strong>livestock sector. See Figure 1. In terms of exports,however, petroleum eclipsed <strong>the</strong> agriculturalsector. Hav<strong>in</strong>g accounted for about 80% ofnational exports before oil was discovered, <strong>the</strong>contribution of crops and livestock comb<strong>in</strong>eddropped to between 5 and 10% of nationalexports after 2000. See Figure 2.This has changed abruptly with <strong>the</strong> secessionof South Sudan <strong>in</strong> July 2011. With 75% of knownoil reserves <strong>in</strong> South Sudan, <strong>the</strong> loss of revenue to<strong>the</strong> economy of Sudan is serious. It has rapidlyreverted to an economy much more dependenton agriculture, with its fluctuat<strong>in</strong>g levels of annualproduction. The loss of oil revenue is associatedwith a rapid deterioration <strong>in</strong> macro-economic<strong>in</strong>dicators, as oil accounted for 75% of Sudan’sforeign exchange. Foreign exchange reserves arelow and <strong>in</strong>flation is runn<strong>in</strong>g at around 30%,accord<strong>in</strong>g to official data at <strong>the</strong> time of writ<strong>in</strong>g.This has contributed to renewed government<strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> livestock sector and <strong>the</strong> role it canplay <strong>in</strong> future economic growth <strong>in</strong> Sudan. SeeSection 2.3 below.Indeed, <strong>the</strong> significance of livestock relative tocrop production <strong>in</strong> Sudan’s domestic economy has<strong>in</strong>creased. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> Central Bureau ofStatistics (CBS) (quoted <strong>in</strong> Behnke, 2012),livestock now accounts for more than 60% ofagriculture’s total contribution to GDP and cropproduction less than 40%, despite <strong>the</strong> fact that <strong>the</strong>latter has been given most attention bygovernment and <strong>in</strong> policy <strong>in</strong>itiatives. See section2.3 below. As a proportion of agricultural exports,<strong>the</strong> ris<strong>in</strong>g contribution of livestock is strik<strong>in</strong>g.Between <strong>the</strong> late 1950s and early 1970s, livestockaccounted for 3 to 6% of all agricultural exports.Between <strong>the</strong> late 1990s and 2009, livestockaccounted for 27 to 47% of agricultural exports,depend<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong> year (Ibid.).Before <strong>the</strong> secession of South Sudan, it waswidely quoted that <strong>the</strong> greater <strong>Darfur</strong> regionaccounted for one-fifth of Sudan’s livestockresources; <strong>the</strong> proportion was believed to be verysimilar for camels, cattle, sheep, and goats (WorldBank, 2007). It is now believed that <strong>Darfur</strong>’slivestock resources account for approximatelyone-quarter to one-third of Sudan’s livestockresources post-secession. However, such estimatesshould be treated with caution, as <strong>the</strong> last livestockcensus was carried out <strong>in</strong> 1975, more than 35years ago. S<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong>n, official statistics on livestockproduction have been extrapolated, based onprojected growth rates and models that <strong>in</strong>dicatelivestock numbers <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g rapidly dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>1990s. Bennke’s (2012) recent comparison of <strong>the</strong>f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs of state-level exercises to count livestockand projections based on <strong>the</strong> 1975 censusillustrates why it is important to treat <strong>the</strong>seextrapolated figures with caution. In <strong>the</strong> three,now five (East, South, Central, West, and North)<strong>Darfur</strong> states, <strong>the</strong>re have been no attempts toupdate livestock figures s<strong>in</strong>ce 1975. Not only have<strong>the</strong>re been significant droughts s<strong>in</strong>ce 1975, <strong>the</strong> lastn<strong>in</strong>e years of violent conflict have had a seriousimpact on livestock hold<strong>in</strong>gs and onconcentration of ownership. In <strong>the</strong>secircumstances, it is unwise to attempt an estimateof current livestock numbers.2.2 An overview of <strong>the</strong> livestock trade <strong>in</strong>Sudan, with a focus on livestock exports<strong>Livestock</strong> are a key component of most rurallivelihoods <strong>in</strong> Sudan, and especially <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong>,whe<strong>the</strong>r as a productive asset for meat and milk,and/or as a form of capital. <strong>Trade</strong> <strong>in</strong> livestock andlivestock products is an essential part of rurallivelihood strategies. Sometimes livestock andlivestock products may be traded betweenlivelihood groups; for example, betweenpastoralists and farmers as <strong>the</strong> former sell animalsto purchase gra<strong>in</strong> and o<strong>the</strong>r foodstuff and as <strong>the</strong>latter <strong>in</strong>vest <strong>in</strong> animals, often with <strong>in</strong>come from14

Figure 1. Contribution of <strong>the</strong> agricultural sector to GDP <strong>in</strong> SudanSource: Central Bureau of Statistics, unpublished data, taken from Behnke (2012)Figure 2. Contribution of <strong>the</strong> agricultural sector to national exports <strong>in</strong> SudanSource: Central Bureau of Statistics, unpublished data, taken from Behnke (2012)sell<strong>in</strong>g part of <strong>the</strong> harvest. <strong>Livestock</strong> are also soldto butchers for domestic meat consumption.Long-distance trade <strong>in</strong> livestock has long been apart of Sudan’s economy: <strong>the</strong> “40 Days Road”—Darb El Arbae<strong>in</strong>—for trekk<strong>in</strong>g camels from <strong>Darfur</strong>and Kordofan to Egypt, for example, is believed tohave existed for centuries. Official figures do not<strong>in</strong>dicate <strong>the</strong> relative significance of domesticversus <strong>in</strong>ternational trade, 3 although <strong>the</strong> growth <strong>in</strong>livestock exports <strong>in</strong> recent decades—see below—may have acted as a stimulus to livestockproduction, especially to sheep production.Indeed, Behnke (2012) suggests that <strong>the</strong>re hasbeen a reorientation of livestock production tosatisfy external markets.3Informally, experts estimate that <strong>the</strong> value of domestic trade <strong>in</strong> livestock is many times greater than <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational trade<strong>in</strong> livestock <strong>in</strong> Sudan.June 2012 • ON THE HOOF: The <strong>Livestock</strong> <strong>Trade</strong> In <strong>Darfur</strong> 15

The ma<strong>in</strong> methods for export<strong>in</strong>g livestock andmeat from Sudan are as follows:• shipp<strong>in</strong>g live sheep, goat, camels, and cattleto <strong>the</strong> Middle East through Port Sudanand Suak<strong>in</strong>• trekk<strong>in</strong>g camels on <strong>the</strong> hoof to Libya andto Egypt• trekk<strong>in</strong>g cattle from Sudan (<strong>Darfur</strong>) toChad and <strong>the</strong> Central African RepublicFigure 3. Sudan’s export of live sheep and goats• fly<strong>in</strong>g chilled meat (from small stock, cattle,and camels), ma<strong>in</strong>ly from abattoirs aroundKhartoum, to <strong>the</strong> Middle East, andoccasionally from Nyala <strong>in</strong> South <strong>Darfur</strong>.(ICRC, 2005a)While most of this is formal trade, recorded <strong>in</strong>official statistics, <strong>the</strong>re is a significant component of<strong>in</strong>formal cross-border trade, particularly fromSource: MoARF&RFigure 4. Sudan’s export of live cattle and camelsSource: MoARF&R16

<strong>Darfur</strong>, for example <strong>the</strong> camel trade to Libya.Live sheep are Sudan’s most importantlivestock export and <strong>the</strong> volume of trade hastrebled s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> early 1980s, although <strong>the</strong>re is highvariability year on year. See Figure 3. Indeed, <strong>the</strong>export of live sheep and goats accounts for morethan 90% of Sudan’s total livestock export earn<strong>in</strong>gsaveraged over a number of years. This is followedby <strong>the</strong> export of live camels, which <strong>in</strong>creasedrapidly <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> mid- to late- 1990s as demand forcamel meat <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>in</strong> Egypt. See Figure 4. Amuch smaller number of live cattle are exported;<strong>in</strong>stead, most are slaughtered with<strong>in</strong> Sudan and <strong>the</strong>meat is exported. Official statistics on Sudan’s meatexports only date back to 2003, although Sudan hasbeen export<strong>in</strong>g meat s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> 1970s. Beef nowaccounts for approximately 65% of Sudan’s totalmeat exports. See Figure 5.Most of Sudan’s livestock and meat exportsare dest<strong>in</strong>ed for <strong>the</strong> Middle East, particularly SaudiArabia, which accounts for over 90% of Sudan’sexport of live sheep and goats. 4 The export of livesheep peaks dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> two months prior to <strong>the</strong>annual Hajj festival. Saudi Arabia is a rapidlygrow<strong>in</strong>g market for meat and for live animals as<strong>the</strong> population becomes more urbanized, as<strong>in</strong>comes rise, and as <strong>the</strong> immigrant workerpopulation <strong>in</strong>creases (Dirani et al., 2009). TheSaudi market for live animals is estimated to begrow<strong>in</strong>g at a rate of 8% p.a.Although Saudi Arabia is Sudan’s mostimportant export market for livestock, Sudan ismuch less significant to Saudi Arabia. Between1998 and 2009 Sudan accounted for an annualaverage of 24% of Saudi Arabia’s total imports oflive sheep and goats (by value). Between 2000 and2007, Sudan accounted for 18% of Saudi Arabia’stotal imports of mutton (by value). 5 The ma<strong>in</strong>export market for Sudanese beef has been Jordan,and, s<strong>in</strong>ce 2010, also Egypt. This reveals Sudan’sexposure to a small number of export markets—three <strong>in</strong> particular, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, andEgypt. This leaves Sudan highly vulnerable tochang<strong>in</strong>g trade regimes and/or demand with<strong>in</strong>those markets. The consequences of such highexposure have been evident on at least twooccasions s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> 2000s. In2000/01, Saudi Arabia banned <strong>the</strong> import ofsheep from eight African countries, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gSudan, because of an outbreak of Rift Valley Fever<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn part of <strong>the</strong> k<strong>in</strong>gdom. This wasrepeated <strong>in</strong> 2006/07 because of an outbreak ofviral hemorrhagic fever (VHF). The devastat<strong>in</strong>gimpact on Sudan’s export earn<strong>in</strong>gs can be seen <strong>in</strong>Figure 6. Overall, Sudan is <strong>in</strong> danger of los<strong>in</strong>g itsshare of <strong>the</strong> market, <strong>in</strong> Saudi Arabia <strong>in</strong> particular,Figure 5. Sudan’s export of meatSource: unpublished data from <strong>the</strong> M<strong>in</strong>istry of Foreign <strong>Trade</strong>4Accord<strong>in</strong>g to unpublished data from <strong>the</strong> M<strong>in</strong>istry of Foreign<strong>Trade</strong>.5Accord<strong>in</strong>g to unpublished data from <strong>the</strong> M<strong>in</strong>istry of Foreign <strong>Trade</strong>.June 2012 • ON THE HOOF: The <strong>Livestock</strong> <strong>Trade</strong> In <strong>Darfur</strong> 17

as o<strong>the</strong>r export<strong>in</strong>g countries with moresophisticated production and market<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>frastructure emerge as major competitors.Australia has become a major competitor <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>live sheep market. Sudan lost its market share ofsheep meat to Saudi Arabia <strong>in</strong> 2008 and 2009, to<strong>the</strong> benefit of Pakistan, Ethiopia, and India. SeeFigures 7a and 7b.Sudan’s imports of live animals and of meatare m<strong>in</strong>imal: <strong>in</strong> 2002 this represented less than 2%of <strong>the</strong> value of its exports for live animals and justover 1% of its exports of meat (FAO, 2005).2.3 The policy contextS<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>in</strong>dependence, <strong>the</strong> livestock sector hasbeen relatively neglected by government policy <strong>in</strong>Sudan, which has long favored crop productionFigure 6. Sudan’s export earn<strong>in</strong>gs from livestockSource: Central Bank of SudanFigures 7a. and 7b. Sudan’s market share of Saudi sheep meat imports, 2007 and 2009Source: unpublished data from <strong>the</strong> M<strong>in</strong>istry of Foreign <strong>Trade</strong>18

and especially <strong>the</strong> expansion of semi-mechanizedra<strong>in</strong>fed agriculture, often at <strong>the</strong> expense oflivestock production and pastoral livelihoods. 6Dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> years of oil production before SouthSudan seceded, <strong>the</strong> attention given by governmentto both crops and livestock dim<strong>in</strong>ishedconsiderably. Although <strong>the</strong>re have been a numberof ambitious government plans and strategies,most recently <strong>the</strong> Agricultural RevivalProgramme (ARP) cover<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> period 2008 to2011, implementation of <strong>the</strong>se plans has tended tobe weak and <strong>the</strong>ir impact limited. The ARP,which has just entered a second phase from 2012to 2016, aimed at moderniz<strong>in</strong>g livestockproduction, improv<strong>in</strong>g market efficiency, andadd<strong>in</strong>g value through process<strong>in</strong>g. 7 However,progress has been limited (although it didrehabilitate Suak<strong>in</strong> quarant<strong>in</strong>e facilities <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> firstphase); this study did not pick up evidence of howthis has benefited <strong>the</strong> livestock trade <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong>.Government policy on livestock hastraditionally emphasized animal health andvacc<strong>in</strong>ation programs, often at <strong>the</strong> expense ofwider concern for animal production issues andlivestock market<strong>in</strong>g. The control and eradicationof R<strong>in</strong>derpest through vacc<strong>in</strong>ation has been ahigh priority. 8 Initially, vacc<strong>in</strong>ations were providedfree of charge, but dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> 2000s this switchedto an emphasis on cost recovery and <strong>the</strong> role of<strong>the</strong> private sector <strong>in</strong> supply<strong>in</strong>g veter<strong>in</strong>ary drugs(ICRC, 2005b). While some commentatorslament decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g government support to diseasecontrol (Ibid.), o<strong>the</strong>rs highlight how Sudan’s livequarant<strong>in</strong>e system has served its export trade,especially compared with parts of Somalia(Somaliland and Puntland), which had no statesanctionedquarant<strong>in</strong>e system and were <strong>the</strong>reforeunable to export live sheep to Saudi Arabiabetween 2001 and 2009, while Sudan faced <strong>the</strong>ban for just one year (Behnke, 2012).<strong>On</strong>e of <strong>the</strong> most significant changes <strong>in</strong>government policy affect<strong>in</strong>g Sudan’s livestocktrade was <strong>the</strong> disband<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Livestock</strong> andMeat Market<strong>in</strong>g Corporation (LMMC) <strong>in</strong> 1992.A government parastatal and service provider, <strong>the</strong>LMMC had supported livestock trade through <strong>the</strong>development of market <strong>in</strong>frastructure, especiallydur<strong>in</strong>g its first phase, runn<strong>in</strong>g certa<strong>in</strong> markets andattempt<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>in</strong>troduce an open auction system(see below), <strong>the</strong> provision of market <strong>in</strong>formationand support to <strong>the</strong> livestock export trade. With<strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> greater <strong>Darfur</strong> region, <strong>the</strong> LMMC managedNyala and Ed Daien livestock markets <strong>in</strong> South<strong>Darfur</strong>, El Fasher and Mellit livestock markets <strong>in</strong>North <strong>Darfur</strong>, and El Gene<strong>in</strong>a livestock market <strong>in</strong>West <strong>Darfur</strong>. It also ran subsidized tra<strong>in</strong>s carry<strong>in</strong>glivestock from Nyala to Omdurman. When <strong>the</strong>LMMC was dissolved <strong>in</strong> 1992, its assets werepassed onto <strong>the</strong> Animal Resources Bank (ARB),which had a commercial livestock market<strong>in</strong>garm—<strong>the</strong> Animal Resources Service Company.However, <strong>the</strong> bank has s<strong>in</strong>ce become acommercial high street bank and all livestockmarket<strong>in</strong>g is now done by <strong>the</strong> private sector(ICRC, 2005b). This change <strong>in</strong> governmentpolicy is still lamented by many livestock tradersand is associated with a concentration of marketpower s<strong>in</strong>ce. Whereas many traders had worked asagents of <strong>the</strong> LMMC, <strong>the</strong> number of exportersappeared to decl<strong>in</strong>e when <strong>the</strong> LMMC wasabolished; for example, <strong>the</strong> number of live sheepexporters decl<strong>in</strong>ed from 350 <strong>in</strong> 1985 (many wereagents of <strong>the</strong> LMMC) to 21 <strong>in</strong> 1995 (Dirani et al.,2009), and are believed to be even fewer today.This concentration of market power wasexacerbated by <strong>the</strong> government’s decision <strong>in</strong> 2003to allocate authority for Sudan’s livestock exportsto <strong>the</strong> Gulf countries to only one trader. Fivemajor traders had previously dom<strong>in</strong>ated <strong>the</strong>term<strong>in</strong>al livestock market <strong>in</strong> Sudan, butgovernment decided to restructure <strong>the</strong> exporttrade follow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> 2000/2001 collapse oflivestock exports, effectively remov<strong>in</strong>gcompetition and creat<strong>in</strong>g a monopoly (Fahey andLeonard, 2007). This cont<strong>in</strong>ued until 2005. Anumber of Sudan’s livestock exporters have gonebankrupt over <strong>the</strong> years, and were jailed for <strong>the</strong>ir<strong>in</strong>ability to pay back bank loans (Aklilu, 2002a).Without <strong>the</strong> LMMC, <strong>the</strong>re is no s<strong>in</strong>glegovernment body at federal level with a strategic6See, for example, Fahey and Leonard (2007).7See <strong>the</strong> Executive Program for Agricultural Revival, April 2008.8Pioneer<strong>in</strong>g work by researchers from Tufts University who developed a r<strong>in</strong>derpest vacc<strong>in</strong>e that could be transported torural areas without refrigeration was critical to this achievement. See http://vet.tufts.edu/pr/20110629.html (lastviewed 22 June 2012).June 2012 • ON THE HOOF: The <strong>Livestock</strong> <strong>Trade</strong> In <strong>Darfur</strong> 19

mandate for promot<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> livestock trade,domestically and <strong>in</strong>ternationally, despite <strong>the</strong>importance of this sector to <strong>the</strong> national economy.Instead, a range of government bodies have someresponsibility for livestock market<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gstate and locality adm<strong>in</strong>istrations, <strong>the</strong> M<strong>in</strong>istry ofForeign <strong>Trade</strong> (MoFT) and <strong>the</strong> M<strong>in</strong>istry ofAnimal Resources, Fisheries and Range(MoARF&R). <strong>Livestock</strong> traders have to deal withall of <strong>the</strong>se bodies as well as banks, customs,transport companies, etc. (Aklilu, 2002a). TheMoFT created a Live Animals and Meat ExportPromotion Council <strong>in</strong> 2004, which wasapparently effective <strong>in</strong> eas<strong>in</strong>g some governmentrestrictions on exporters, but livestock producerswere not well-represented on <strong>the</strong> Council (Ibid.).The ARP established a series of commoditycouncils, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g a livestock council compris<strong>in</strong>gthree committees for livestock, meat, and lea<strong>the</strong>rrespectively. The objective is to promote strategiesand policies for develop<strong>in</strong>g livestock, particularlythrough coord<strong>in</strong>ation of all activities <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>commodity cha<strong>in</strong> up to <strong>the</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t of consumption,from research through production, process<strong>in</strong>g, andquality control. It is judged to be one of <strong>the</strong> moreeffective of <strong>the</strong> n<strong>in</strong>eteen councils established by<strong>the</strong> ARP 9 and has drawn government decisionmakers’attention to some of <strong>the</strong> constra<strong>in</strong>ts tolivestock market<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g high taxation andfees and poor animal health services, as a result ofwhich government has taken action to rehabilitate<strong>the</strong> quarant<strong>in</strong>e facilities <strong>in</strong> Port Sudan and <strong>in</strong>Khartoum North, and to establish an exportpromotion fund held by <strong>the</strong> Bank of Sudan. At<strong>the</strong> time of writ<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>the</strong> World Bank MDTF(Multi-Donor Trust Fund) project is work<strong>in</strong>gwith MoARF&R to develop a strategy fordevelop<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> livestock sector.With <strong>the</strong> demise of <strong>the</strong> LMMC, livestockmarkets became <strong>the</strong> responsibility of <strong>the</strong>respective locality <strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong>y were located.Effectively, responsibility for manag<strong>in</strong>g livestockmarkets has been decentralized to state andlocality levels, where <strong>the</strong>y are regarded primarilyas a source of <strong>in</strong>come, and <strong>the</strong>re is little evidenceof those tax revenues be<strong>in</strong>g re<strong>in</strong>vested to support<strong>the</strong> livestock sector (Dirani et al., 2009). As withtrade <strong>in</strong> most o<strong>the</strong>r agricultural produce,numerous taxes and fees are applied to livestock.An analysis of available studies <strong>in</strong> 2002 showedthat “taxes and fees constitute up to 27% of <strong>the</strong>cost of <strong>the</strong> exported animal and may go up to40% if fodder is <strong>in</strong>cluded” (Aklilu, 2002a, 69).A more recent World Bank study records taxesand fees account<strong>in</strong>g for 14 to 20% of totalmarket<strong>in</strong>g costs when animals from westernSudan are transported on <strong>the</strong> hoof and sold on<strong>the</strong> domestic market, and averag<strong>in</strong>g around 13% iftransported by truck (M<strong>in</strong>a and Van HolstPelekaan, 2010). This is fur<strong>the</strong>r explored <strong>in</strong>relation to <strong>the</strong> livestock trade <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong> <strong>in</strong> section6 below, which shows <strong>the</strong> extent to which locallyimposed taxes have risen. It is widely acceptedthat Sudan has one of <strong>the</strong> heaviest and mostcomplex taxation regimes <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> region (Aklilu,2002a).There have been various attempts over <strong>the</strong>years to <strong>in</strong>troduce an auction system for Sudan’sma<strong>in</strong> livestock markets, widely regarded as anefficient method for livestock trad<strong>in</strong>g because of<strong>the</strong> transparency of market <strong>in</strong>formation associatedwith open auction. 10 The LMMC establishedeleven market centers with weigh<strong>in</strong>g scales andauction yards before it was disbanded, but <strong>the</strong>sefailed, apparently because <strong>the</strong> system wassabotaged by brokers who did not support it, andan auction system required immediate cashpayments whereas Sudan’s livestock trad<strong>in</strong>g systemhas traditionally been based on trust and credit(Aklilu, 2002a). More recently, a projectsupport<strong>in</strong>g livestock markets, funded by <strong>the</strong>MDTF and adm<strong>in</strong>istered by <strong>the</strong> World Bank, hasonce aga<strong>in</strong> attempted to <strong>in</strong>troduce an auctionsystem <strong>in</strong>to six markets that it is rehabilitat<strong>in</strong>g,although none is <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong>: <strong>the</strong> closest is Ghibeishmarket <strong>in</strong> West Kordofan, important for sheep. 11In terms of livestock production, a majorpiece of legislation that could affect <strong>the</strong> livestocktrade is <strong>the</strong> 2010 Agriculture and AnimalProducers’ Act. If endorsed by <strong>the</strong> GeneralAssembly, this would effectively cancel <strong>the</strong>Organizations of Farmers and Pastoralists Act of9Accord<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> ARP report on <strong>the</strong> performance of <strong>the</strong> councils <strong>in</strong> 2011.10This contrasts with <strong>the</strong> “Silent Auction System” that prevails <strong>in</strong> Sudan, which means that livestock prices are hard to obta<strong>in</strong>and market <strong>in</strong>formation is not readily available (Aklilu, 2002b).11Ghibeish, El Nihood, El Khowei, Abo Zabad <strong>in</strong> North Kordofan state, El Damazeen <strong>in</strong> Blue Nile state, and S<strong>in</strong>ja <strong>in</strong>S<strong>in</strong>nar state.20

1992. Producer Associations would replace <strong>the</strong>Pastoralist Union and Farmers Union and would<strong>in</strong>clude traders. There is concern that this wouldreduce <strong>the</strong> voice and representation of small-scalelivestock producers (Young et al., 2012).S<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> secession of South Sudan and <strong>the</strong>abrupt fall <strong>in</strong> oil revenues, federal government <strong>in</strong>Khartoum has once aga<strong>in</strong> turned its attention tolivestock (as well as agriculture) as a potentialdriver of economic growth and source of foreignexchange. 12 However, lack of resources appears tobe constra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g efforts and at <strong>the</strong> time of writ<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong>re is no evidence <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> three <strong>Darfur</strong> states ofany new government <strong>in</strong>vestment.2.4 <strong>Livestock</strong> exports: <strong>the</strong> major constra<strong>in</strong>tsAlthough Sudan’s export trade <strong>in</strong> livestockand livestock products shows an upwards trendoverall, it faces many constra<strong>in</strong>ts, which could haltfuture growth and development <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> face of<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g and more aggressive competition fromo<strong>the</strong>r major livestock export<strong>in</strong>g countries <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>future. This <strong>in</strong> turn could impact on futuregrowth of <strong>the</strong> livestock trade <strong>in</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong>, of whichexports are an important component. Dirani et al.(2009) have explored some of <strong>the</strong>se constra<strong>in</strong>ts <strong>in</strong>relation to exports of live sheep and sheep meat,while o<strong>the</strong>r authors have documented <strong>the</strong> factorsconstra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g livestock exports more generally.Some of <strong>the</strong> most significant constra<strong>in</strong>ts are<strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g:(1) Globalization of trade regimes is result<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly strict welfare, hygiene, anddisease control regulations <strong>in</strong> livestockimport<strong>in</strong>g countries <strong>in</strong> Europe and <strong>the</strong>Middle East (ICRC, 2005b). In SaudiArabia, Sudan’s ma<strong>in</strong> export market, <strong>the</strong>reis <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g demand for chilled andfrozen meat, which demands morerigorous <strong>in</strong>spection and certificationsystems. Sudan does not currently haveadequate policies, veter<strong>in</strong>ary services, orphysical <strong>in</strong>frastructure to support itslivestock trade <strong>in</strong> respond<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong>semore rigorous requirements, especiallywhen compet<strong>in</strong>g with new suppliers likeAustralia, Brazil, New Zealand, and <strong>the</strong>European Union (EU) that are betterequipped to comply with such regulations(Idriss, 2008).(2) High dependence on a small number ofexport markets, particularly Saudi Arabiaand Egypt, leaves Sudan’s export tradevulnerable to national bans and/orchang<strong>in</strong>g trade regimes. There is also ahigh level of variability <strong>in</strong> Saudi’s demandfor live sheep annually, which <strong>in</strong> turnaffects Sudan’s export trade (Ijaimi, 2011).(3) Sudan’s major livestock produc<strong>in</strong>g areasare located far from Khartoum and farfrom its ma<strong>in</strong> export markets. Lack of<strong>in</strong>frastructure means that most livestockare trekked on <strong>the</strong> hoof to Khartoum.Dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> dry season, when water andgraz<strong>in</strong>g are scarce, this is an <strong>in</strong>efficientform of transportation that takesconsiderable time and has negativeconsequences for <strong>the</strong> health and qualityof <strong>the</strong> animals and for <strong>the</strong> quality of <strong>the</strong>meat (Dirani et al., 2009).(4) The extent to which Sudan’s livestocktrade is broker-dom<strong>in</strong>ated is said to be“without any parallel <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> region”(Aklilu, 2002a, 57). Animals may changehands between two and six times between<strong>the</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t of purchase and <strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>al po<strong>in</strong>tof sale, between <strong>Darfur</strong> and Khartoum,for example (Ibid.). How this impacts onmarket efficiency of <strong>the</strong> supply cha<strong>in</strong> forlivestock, however, requires fur<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>vestigation.(5) For live sheep, Sudan’s ma<strong>in</strong> livestockexport, <strong>the</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and test<strong>in</strong>g ofanimals for export happens late <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>cha<strong>in</strong>, result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a high level ofrejection: 31% of sheep offered for exportbetween 1997 and 2005 were rejected.This <strong>in</strong>creases costs and reducescompetitiveness. Lack of capacity toscreen and test animals at <strong>the</strong> primary<strong>in</strong>spection stage thus contributes tomarket <strong>in</strong>efficiency (Dirani et al., 2009).12See, for example, <strong>the</strong> 2011 National Salvation Plan, and <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terim Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP).June 2012 • ON THE HOOF: The <strong>Livestock</strong> <strong>Trade</strong> In <strong>Darfur</strong> 21

(6) Limited or no access by livestock tradersto formal credit is ano<strong>the</strong>r constra<strong>in</strong>t,fur<strong>the</strong>r discussed <strong>in</strong> relation to traders <strong>in</strong><strong>Darfur</strong> <strong>in</strong> section 6.2 below.(7) Official exporters of livestock must use<strong>the</strong> official exchange rate, although this iscurrently far below <strong>the</strong> black marketexchange rate and means, for example,that sheep cannot be sold <strong>in</strong> Saudi Arabiaprofitably. This is driv<strong>in</strong>g some exportersout of <strong>the</strong> livestock trade andencourag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formal export trad<strong>in</strong>g/smuggl<strong>in</strong>g.Many of <strong>the</strong>se constra<strong>in</strong>ts relate to <strong>the</strong> policycontext for livestock trad<strong>in</strong>g, and/or could beaddressed through government strategies andpolicies that support <strong>the</strong> livestock trade. Ways ofaddress<strong>in</strong>g some of <strong>the</strong>se constra<strong>in</strong>ts are explored<strong>in</strong> section 10.2 below.22