Chapter 11 Production of Scotch and Irish whiskies: their history and ...

Chapter 11 Production of Scotch and Irish whiskies: their history and ...

Chapter 11 Production of Scotch and Irish whiskies: their history and ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

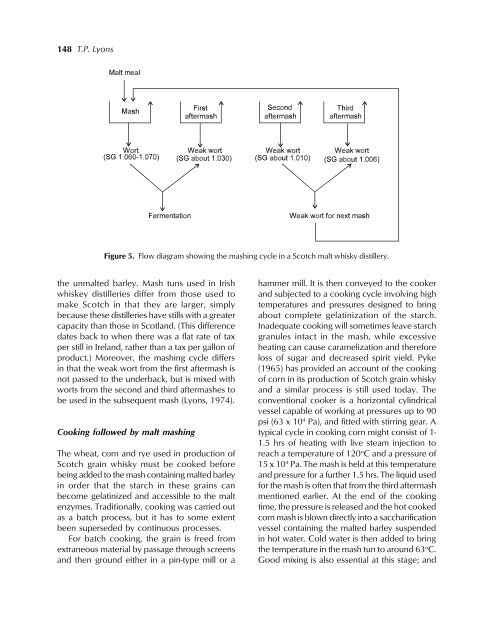

148 T.P. LyonsFigure 5. Flow diagram showing the mashing cycle in a <strong>Scotch</strong> malt whisky distillery.the unmalted barley. Mash tuns used in <strong>Irish</strong>whiskey distilleries differ from those used tomake <strong>Scotch</strong> in that they are larger, simplybecause these distilleries have stills with a greatercapacity than those in Scotl<strong>and</strong>. (This differencedates back to when there was a flat rate <strong>of</strong> taxper still in Irel<strong>and</strong>, rather than a tax per gallon <strong>of</strong>product.) Moreover, the mashing cycle differsin that the weak wort from the first aftermash isnot passed to the underback, but is mixed withworts from the second <strong>and</strong> third aftermashes tobe used in the subsequent mash (Lyons, 1974).Cooking followed by malt mashingThe wheat, corn <strong>and</strong> rye used in production <strong>of</strong><strong>Scotch</strong> grain whisky must be cooked beforebeing added to the mash containing malted barleyin order that the starch in these grains canbecome gelatinized <strong>and</strong> accessible to the maltenzymes. Traditionally, cooking was carried outas a batch process, but it has to some extentbeen superseded by continuous processes.For batch cooking, the grain is freed fromextraneous material by passage through screens<strong>and</strong> then ground either in a pin-type mill or ahammer mill. It is then conveyed to the cooker<strong>and</strong> subjected to a cooking cycle involving hightemperatures <strong>and</strong> pressures designed to bringabout complete gelatinization <strong>of</strong> the starch.Inadequate cooking will sometimes leave starchgranules intact in the mash, while excessiveheating can cause caramelization <strong>and</strong> thereforeloss <strong>of</strong> sugar <strong>and</strong> decreased spirit yield. Pyke(1965) has provided an account <strong>of</strong> the cooking<strong>of</strong> corn in its production <strong>of</strong> <strong>Scotch</strong> grain whisky<strong>and</strong> a similar process is still used today. Theconventional cooker is a horizontal cylindricalvessel capable <strong>of</strong> working at pressures up to 90psi (63 x 10 4 Pa), <strong>and</strong> fitted with stirring gear. Atypical cycle in cooking corn might consist <strong>of</strong> 1-1.5 hrs <strong>of</strong> heating with live steam injection toreach a temperature <strong>of</strong> 120 o C <strong>and</strong> a pressure <strong>of</strong>15 x 10 4 Pa. The mash is held at this temperature<strong>and</strong> pressure for a further 1.5 hrs. The liquid usedfor the mash is <strong>of</strong>ten that from the third aftermashmentioned earlier. At the end <strong>of</strong> the cookingtime, the pressure is released <strong>and</strong> the hot cookedcorn mash is blown directly into a saccharificationvessel containing the malted barley suspendedin hot water. Cold water is then added to bringthe temperature in the mash tun to around 63 o C.Good mixing is also essential at this stage; <strong>and</strong>