Working Papers in Literacy, Culture, and Language Education

Working Papers in Literacy, Culture, and Language Education

Working Papers in Literacy, Culture, and Language Education

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

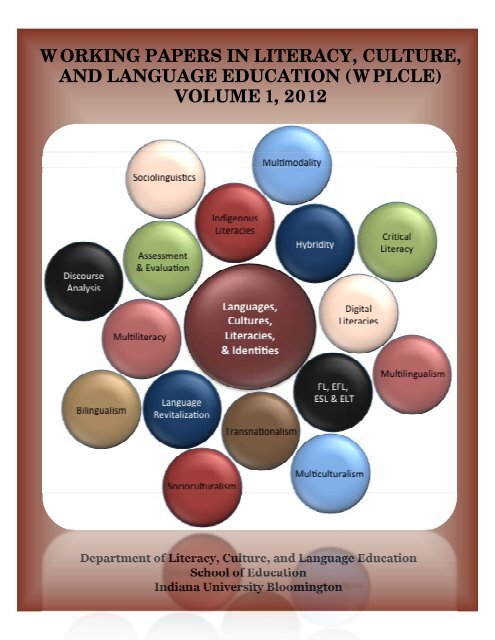

WORKING PAPERS IN LITERACY, CULTURE,AND LANGUAGE EDUCATION (WPLCLE)VOLUME 1, 2012Department of <strong>Literacy</strong>, <strong>Culture</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Language</strong> <strong>Education</strong>School of <strong>Education</strong>Indiana University Bloom<strong>in</strong>gton

EDITORIAL BOARDFounder & Editor<strong>in</strong>ChiefSerafín M. CoronelMol<strong>in</strong>aManag<strong>in</strong>g EditorBita H. ZakeriAssistants to the EditorsBeth BuchholzAlfreda CleggY<strong>in</strong>gS<strong>in</strong> ChenSang Jai ChoiValerie CrossOphelia Hsiangl<strong>in</strong>g HuangHsiaoChun S<strong>and</strong>ra HuangYi Ch<strong>in</strong> HsiehSheri JordanJames KigamwaHyeKyung KimHsiaoCh<strong>in</strong> KuoYi Ch<strong>in</strong>g LeeEr<strong>in</strong> LemrowJaehan ParkStacy PenalvaJulie RustBryce SmedleyChristy WesselPowellChiChuan YangJaeSeok YangDonna Sayers AdomatStephanie CarterJames DamicoD. Ted HallMary Beth H<strong>in</strong>esMitzi LewisonCarmen Med<strong>in</strong>aADVISORY BOARDWEBMASTERSSerafín M. CoronelMol<strong>in</strong>aJaehan ParkLarry MikuleckyMartha NyikosFaridah PawanBeth Lewis SamuelsonRaymond SmithKaren Wohlwend

Copyright © 2012 <strong>Work<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Papers</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Literacy</strong>, <strong>Culture</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Language</strong> <strong>Education</strong> (WPLCLE), <strong>and</strong> therespective authors.All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced <strong>in</strong> any form by any means, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gphotocopy<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> record<strong>in</strong>g, or by any <strong>in</strong>formation storage or retrieval system (except for brief quotations <strong>in</strong>critical articles or reviews) without written permission from WPLCLE or the respective authors.<strong>Work<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Papers</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Literacy</strong>, <strong>Culture</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Language</strong> <strong>Education</strong> (WPLCLE)School of <strong>Education</strong>, Indiana UniversityW.W. Wright <strong>Education</strong> Build<strong>in</strong>g201 N. Rose Ave., Room #3044Bloom<strong>in</strong>gton, IN 47405‐1006Phone: (812) 856‐8270Fax: (812) 856‐8287E‐mail: wplcle@<strong>in</strong>diana.eduWebsite: http://education.<strong>in</strong>diana.edu/Home/tabid/13967/Default.aspxPAGE | ii

AcknowledgementsThe <strong>Work<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Papers</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Literacy</strong>, <strong>Culture</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Language</strong> <strong>Education</strong> (WPLCLE) is a projectvery near <strong>and</strong> dear to my heart. Despite the immense amount of time <strong>and</strong> effort I havespent <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g the concept, <strong>and</strong> formatt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> edit<strong>in</strong>g this first volume, I could nothave brought it to publication alone. Both the creation of the WPLCLE <strong>and</strong> the editorialprocess of the present volume are the result of the cont<strong>in</strong>ued support, hard work, <strong>and</strong>dedication of many people. First of all, my profound gratitude goes to Mary Beth H<strong>in</strong>es, theformer Chair, <strong>and</strong> Larry J. Mikulecky, the current Chair of the Department of <strong>Literacy</strong>,<strong>Culture</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Language</strong> <strong>Education</strong> (LCLE) for their k<strong>in</strong>d support. They helped me presentthis case before the Executive Associate Deans of the School of <strong>Education</strong> at that time, DonHossler <strong>and</strong> Jack Cumm<strong>in</strong>gs, who graciously provided vital resources for the operations ofthe WPLCLE.After I f<strong>in</strong>ished develop<strong>in</strong>g the content, Pratima Dutta <strong>and</strong> Jon Lawrence helped medesign the website, <strong>and</strong> upload the <strong>in</strong>itial content. Subsequently, I publicized this newpublication venue widely, <strong>and</strong> recruited graduate student volunteers to fill key positionssuch as Manag<strong>in</strong>g Editor, Assistants to the Editors, <strong>and</strong> Webmasters. I was fortunate to f<strong>in</strong>dwonderful people who fulfilled their respective roles <strong>in</strong> WPLCLE exceptionally. My heartfeltthanks go to all of them for their dedicated collaboration. I am also deeply grateful to mycolleagues <strong>in</strong> LCLE for agree<strong>in</strong>g to serve on the Advisory Board, <strong>and</strong> for theirencouragement <strong>and</strong> moral support to make this <strong>in</strong>itiative happen.My special thanks go to Bita H. Zakeri, who provided me <strong>in</strong>valuable assistance <strong>in</strong> herrole as Manag<strong>in</strong>g Editor, designed the cover of the present volume, <strong>and</strong> drafted theIntroduction. I also owe a debt of gratitude to <strong>in</strong>stitutions, friends, colleagues, <strong>and</strong> socialmedia venues from Indiana University <strong>and</strong> from around the world for their help <strong>in</strong>publiciz<strong>in</strong>g the WPLCLE Call for <strong>Papers</strong> locally <strong>and</strong> globally.Last but not least, I am profoundly grateful to all the contributors to this volume forchoos<strong>in</strong>g WPLCE to publish their work. My deepest gratitude also goes to the Departmentof <strong>Literacy</strong>, <strong>Culture</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Language</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> the School of <strong>Education</strong> for host<strong>in</strong>g theWPLCE website <strong>and</strong> for support<strong>in</strong>g this new publication venue. Without the generousassistance of all these f<strong>in</strong>e people <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutions, WPLCLE would never have become areality, <strong>and</strong> this volume would never have seen light of day.Bloom<strong>in</strong>gton, Indiana, March 5, 2012Serafín M. CoronelMol<strong>in</strong>aPAGE | iii

TABLE OF CONTENTSContributors ............................................................................................................................................................ viIntroductionSerafín M. CoronelMol<strong>in</strong>a & Bita H. Zakeri .......................................................................................... 1LANGUAGE, CULTURE, IDENTITY, AND BILINGUALISM ................................................................... 6Inga <strong>Language</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Culture</strong> Revitalization <strong>in</strong> Putumayo, ColombiaValerie Cross & Serafín M. CoronelMol<strong>in</strong>a ............................................................................................ 7Background <strong>and</strong> Motivation of Students Study<strong>in</strong>g a Native American <strong>Language</strong> at theUniversity LevelJuliet L. Morgan ............................................................................................................................................. 27Complexities of Immigrant Identity: Issues of <strong>Literacy</strong>, <strong>Language</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Culture</strong> <strong>in</strong> theFormation of IdentityBita H. Zakeri .................................................................................................................................................. 50Students Writ<strong>in</strong>g across <strong>Culture</strong>s: Teach<strong>in</strong>g Awareness of Audience <strong>in</strong> a Co‐curricularService Learn<strong>in</strong>g ProjectBeth Lewis Samuelson & James Chamwada Kigamwa ................................................................... 69The Curriculum as <strong>Culture</strong>s <strong>in</strong> Conflict: Explor<strong>in</strong>g Monocultural <strong>and</strong> MulticulturalIdeologies through the Case of Bil<strong>in</strong>gual <strong>Education</strong>Juanjuan Zhu & Steven P. Camicia ......................................................................................................... 88LITERACY STUDIES .......................................................................................................................................... 106One Story, Many Perspectives: Read<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> Writ<strong>in</strong>g Graphic Novels <strong>in</strong> the ElementarySocial Studies ClassroomErica Christie ................................................................................................................................................ 107St<strong>and</strong>ard Written Academic English: A Critical AppraisalLaura (Violeta) Colombo ......................................................................................................................... 125A Skype‐Buddy Model for Blended Learn<strong>in</strong>gCarmen E. Macharaschwili & L<strong>in</strong>da Skidmore Cogg<strong>in</strong> ................................................................. 141Look<strong>in</strong>g for Children Left Beh<strong>in</strong>d: American <strong>Language</strong> Policies <strong>in</strong> a Multil<strong>in</strong>gual WorldSuparna Bose ................................................................................................................................................ 161PAGE | iv

<strong>Literacy</strong> Programs for Incarcerated Youth <strong>in</strong> the United StatesDiana Brace .................................................................................................................................................. 184ENGLISH AS A SECOND AND FOREIGN LANGUAGE ......................................................................... 198Strategy‐Based Read<strong>in</strong>g Instruction Utiliz<strong>in</strong>g the CALLA Model <strong>in</strong> an ESL/EFL ContextYoungMee Suh ............................................................................................................................................ 199The Challenges of Teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> Learn<strong>in</strong>g English Literature <strong>in</strong> L2 Context: The Case ofJunior Secondary Schools <strong>in</strong> BotswanaDeborah Aden<strong>in</strong>hun Adeyemi ................................................................................................................ 213The Effectiveness of Correct<strong>in</strong>g Grammatical Errors <strong>in</strong> Writ<strong>in</strong>g Classes: An EFL Teacher’sPerspectiveHyeKyung Kim ............................................................................................................................................ 227Undocumented Mexican Immigrants <strong>in</strong> Adult ESL Classrooms: Some Issues to ConsiderSheri Jordan .................................................................................................................................................. 238Book Review<strong>Language</strong> Learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> Teacher <strong>Education</strong>: A Sociocultural Approach, edited by MargaretHawk<strong>in</strong>gs, Clevedon, UK: Multil<strong>in</strong>gual Matters, 2004Craig D. Howard .......................................................................................................................................... 251PAGE | v

ContributorsDeborah Aden<strong>in</strong>hun Adeyemi holds a Doctor of <strong>Education</strong> degree from the University ofSouth Africa (UNISA) <strong>in</strong> English <strong>Language</strong> <strong>Education</strong>. She is presently a senior lecturer <strong>in</strong>the Department of <strong>Language</strong>s <strong>and</strong> Social Sciences <strong>Education</strong> at the University of Botswana.Her Master of <strong>Education</strong> degree is from the University of Botswana <strong>in</strong> English <strong>Language</strong><strong>Education</strong>, <strong>and</strong> she earned her BS <strong>in</strong> English <strong>Education</strong> from Indiana University,Bloom<strong>in</strong>gton, USA. She specializes <strong>in</strong> <strong>Language</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Education</strong> issues <strong>and</strong> pedagogy. Herpublications have appeared <strong>in</strong> the Journal of the International Society for Teacher <strong>Education</strong>(JISTE), Journal of <strong>Education</strong>al Enquiry, New Horizons <strong>in</strong> <strong>Education</strong>, <strong>and</strong> Academic ExchangeQuarterly, to mention a few.Suparna Bose is currently a graduate student work<strong>in</strong>g on a Master’s degree <strong>in</strong> <strong>Literacy</strong>,<strong>Culture</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Language</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> the School of <strong>Education</strong> at Indiana University,Bloom<strong>in</strong>gton. She is <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> English as a Second <strong>Language</strong>, multil<strong>in</strong>gualism,multiculturalism, <strong>and</strong> race relations <strong>in</strong> the contemporary world. She is orig<strong>in</strong>ally from India<strong>and</strong> holds a Master’s degree <strong>in</strong> English Literature, specializ<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the Renaissance. She hastaught English literature <strong>and</strong> ESL <strong>in</strong> India, S<strong>in</strong>gapore <strong>and</strong> Japan. She speaks English, Bengali<strong>and</strong> H<strong>in</strong>di.Diana Brace is a graduate student <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Literacy</strong>, <strong>Culture</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Language</strong> <strong>Education</strong>department. She holds a Bachelor’s degree <strong>in</strong> Journalism <strong>and</strong> Mass Communication fromthe University of Iowa, as well as certification <strong>in</strong> secondary English <strong>and</strong> Journalismeducation from the same <strong>in</strong>stitution. Her research <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>in</strong>clude adolescent literacies,critical literacy, literacy identities, social justice education, crim<strong>in</strong>al justice reform, <strong>and</strong> howthese <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>in</strong>tersect with education <strong>in</strong> the crim<strong>in</strong>al justice system.Steven P. Camicia is an Assistant Professor <strong>in</strong> the School of Teacher <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong>Leadership at Utah State University. His research focuses on curriculum <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>struction <strong>in</strong>the areas of perspective consciousness, social justice, global education, <strong>and</strong> democraticdecision mak<strong>in</strong>g processes.L<strong>in</strong>da Skidmore Cogg<strong>in</strong> is a doctoral student <strong>in</strong> <strong>Literacy</strong>, <strong>Culture</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Language</strong> at IndianaUniversity, Bloom<strong>in</strong>gton. Her research <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>in</strong>clude literacy learn<strong>in</strong>g through multiplemodalities <strong>and</strong> children as producers of multimodal texts.Laura (Violeta) Colombo holds a Master’s <strong>in</strong> Intercultural Communication <strong>and</strong> she holds adoctorate <strong>in</strong> <strong>Language</strong>, <strong>Literacy</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Culture</strong> from the University of Maryl<strong>and</strong>, BaltimoreCounty. Her research <strong>in</strong>terests are academic writ<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> foreign languages, especially at theuniversity level, <strong>and</strong> second language education.PAGE | vi

CONTRIBUTORSPAGE | viiSerafín M. CoronelMol<strong>in</strong>a is an Assistant Professor <strong>in</strong> the Department of <strong>Literacy</strong>,<strong>Culture</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Language</strong> <strong>Education</strong> at Indiana University, Bloom<strong>in</strong>gton. He is an educationall<strong>in</strong>guist <strong>and</strong> sociol<strong>in</strong>guist. Dr. Coronel‐Mol<strong>in</strong>a received his Bachelor’s degree from RicardoPalma University <strong>in</strong> Peru; his Master’s degree from The Ohio State University, <strong>and</strong> his Ph.D.from the University of Pennsylvania. He has published articles <strong>in</strong> Quechua, English <strong>and</strong>Spanish, <strong>and</strong> has presented papers nationally <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternationally. His research is of an<strong>in</strong>terdiscipl<strong>in</strong>ary nature, draw<strong>in</strong>g on fields as diverse as sociol<strong>in</strong>guistics, l<strong>in</strong>guisticanthropology, literacy studies, policies <strong>and</strong> politics of language, pragmatics, <strong>and</strong> history ofthe Andes.Erica M. Christie is a doctoral c<strong>and</strong>idate <strong>in</strong> Curriculum <strong>and</strong> Instruction at IndianaUniversity with a m<strong>in</strong>or <strong>in</strong> Social Foundations of <strong>Education</strong>. The title of her dissertation is“Reorient<strong>in</strong>g Service Learn<strong>in</strong>g: Teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> Learn<strong>in</strong>g for Social Justice <strong>in</strong> an ElementaryClassroom.” She holds a Master of Science <strong>in</strong> Elementary <strong>Education</strong> from Indiana University<strong>and</strong> a Bachelor of Arts <strong>in</strong> Sociology from Bowdo<strong>in</strong> College. Erica previously worked as anelementary teacher <strong>in</strong> Indianapolis, Indiana. Her research <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>in</strong>clude social studieseducation, service learn<strong>in</strong>g, curriculum <strong>in</strong>tegration, <strong>and</strong> critical literacy.Valerie Cross is a Ph.D. student <strong>in</strong> the department of <strong>Literacy</strong>, <strong>Culture</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Language</strong><strong>Education</strong> at Indiana University. She received her Bachelor’s degree from FurmanUniversity <strong>in</strong> Spanish <strong>and</strong> Psychology, <strong>and</strong> her Master’s <strong>in</strong> Teach<strong>in</strong>g English to Speakers ofOther <strong>Language</strong>s from Indiana University <strong>in</strong> 2007. Valerie has taught ESL at IndianaUniversity <strong>and</strong> the Universidad de Oriente <strong>in</strong> Yucatan, Mexico. Her research <strong>in</strong>terests<strong>in</strong>clude <strong>in</strong>digenous language ma<strong>in</strong>tenance, bil<strong>in</strong>gual education, <strong>and</strong> language teacherdevelopment.Craig D. Howard is a Ph.D. c<strong>and</strong>idate at Indiana University <strong>in</strong> Instructional SystemsTechnology <strong>and</strong> the assistant editor of the International Journal of Designs for Learn<strong>in</strong>g. Heholds a Master of Arts from Teachers College, Columbia University <strong>in</strong> TESOL, <strong>and</strong> hastaught ESL at the City University of New York <strong>and</strong> EFL at K<strong>and</strong>a University of InternationalStudies <strong>in</strong> Chiba, Japan. His research focuses on develop<strong>in</strong>g methods for teach<strong>in</strong>g discourseskills to both native <strong>and</strong> non‐native speakers.Sheri Jordan has taught adult ESL for over 15 years, ma<strong>in</strong>ly <strong>in</strong> adult education <strong>and</strong>university programs on the West Coast of the United States. She is currently f<strong>in</strong>ish<strong>in</strong>g hercoursework <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Literacy</strong>, <strong>Culture</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Language</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Ph.D. program at IndianaUniversity. At IU, she has also taught Multicultural <strong>Education</strong>, Critical <strong>Literacy</strong> <strong>in</strong> theContent Areas, <strong>and</strong> other undergraduate <strong>and</strong> graduate courses <strong>in</strong> the School of <strong>Education</strong>.James Chamwada Kigamwa is a Ph.D. C<strong>and</strong>idate <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Literacy</strong>, <strong>Culture</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Language</strong><strong>Education</strong> Department at Indiana University. Prior to start<strong>in</strong>g the doctoral program at IU,he was <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> regional literacy efforts <strong>in</strong> eastern Africa.HyeKyung Kim is a doctoral c<strong>and</strong>idate <strong>in</strong> the Department of <strong>Literacy</strong>, <strong>Culture</strong>, <strong>and</strong><strong>Language</strong> <strong>Education</strong> at Indiana University. Before pursu<strong>in</strong>g her doctoral degree <strong>in</strong> the US,she taught for almost ten years at the college level <strong>in</strong> South Korea. At IU, she has taughtSocio/Psychol<strong>in</strong>guistic Applications to Read<strong>in</strong>g Instruction <strong>and</strong> Instructional Issues <strong>in</strong><strong>Language</strong> Learn<strong>in</strong>g for English Teachers. Her research <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>in</strong>clude teacher education

PAGE | viiiCONTRIBUTORSfor non‐native EFL/ESL teachers, bil<strong>in</strong>gual education for EFL/ESL children, EFL/ESLteacher <strong>and</strong> learner identity, <strong>and</strong> issues of World Englishes.Carmen E. Macharaschwili is a doctoral student <strong>in</strong> <strong>Literacy</strong>, <strong>Culture</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Language</strong><strong>Education</strong> at Indiana University, Bloom<strong>in</strong>gton. Carmen teaches <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Education</strong>Department at Holy Cross College <strong>and</strong> for the Alliance for Catholic <strong>Education</strong> English as aNew <strong>Language</strong> Program at the University of Notre Dame. Her research <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>in</strong>cludetechnology <strong>in</strong> the classroom, bil<strong>in</strong>gual education, family literacy, <strong>and</strong> cross‐cultural literacy.Juliet L. Morgan is currently pursu<strong>in</strong>g a Master of Arts <strong>in</strong> Applied L<strong>in</strong>guistic Anthropologyat the University of Oklahoma. She received a Bachelor’s degree <strong>in</strong> Spanish <strong>and</strong> Frenchfrom the University of Arkansas <strong>in</strong> 2009. In addition to research<strong>in</strong>g the Native Americanlanguage classes <strong>in</strong> higher education <strong>in</strong> Oklahoma, she is writ<strong>in</strong>g her thesis on theclassificatory verb system <strong>in</strong> Pla<strong>in</strong>s Apache. She <strong>in</strong>tends to graduate <strong>in</strong> Spr<strong>in</strong>g of 2012.Beth Lewis Samuelson is an Assistant Professor of <strong>Literacy</strong>, <strong>Culture</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Language</strong><strong>Education</strong> at the Indiana University School of <strong>Education</strong>, where she teaches classes <strong>in</strong>literacy theory <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> the English as a Second <strong>Language</strong> <strong>and</strong> World <strong>Language</strong>s teachereducation programs. She is an educational l<strong>in</strong>guist with a strong background <strong>in</strong> languagelearn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> cross‐cultural experience <strong>in</strong> non‐Western contexts. She was a 2006Spencer/National Academy of <strong>Education</strong> Postdoctoral Fellow <strong>and</strong> a f<strong>in</strong>alist <strong>in</strong> the 2006National Council of Teachers of English Promis<strong>in</strong>g Researcher competition. Her research<strong>in</strong>terests <strong>in</strong>clude language awareness <strong>and</strong> the flows of English literacy practices acrossglobal boundaries. She has particular <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>in</strong> underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g the nature of metaknowledgeabout language <strong>and</strong> the role that it plays <strong>in</strong> literacy learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong>communication. Dr. Samuelson received a 2012 Margot Stern Strom Teach<strong>in</strong>g Award fromFac<strong>in</strong>g History <strong>and</strong> Ourselves.YoungMee Suh teaches undergraduate <strong>and</strong> graduate students <strong>in</strong> Korea, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g theory<strong>and</strong> practice <strong>in</strong> secondary school English for pre‐service <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>‐service teachers, generalEnglish read<strong>in</strong>g for freshmen <strong>and</strong> sophomores, <strong>and</strong> vocabulary tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g for English majorstudents. Her research <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>in</strong>clude strategy‐based language teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>an EFL context, material development for EFL classes, <strong>and</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g teachers forprofessional development.Bita H. Zakeri is a doctoral student <strong>in</strong> <strong>Literacy</strong>, <strong>Culture</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Language</strong> <strong>Education</strong> at IndianaUniversity. Her research <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>in</strong>clude ESL/EFL research <strong>and</strong> literacy development <strong>in</strong>various cultures, with particular focus on immigrant identity, especially the ways <strong>in</strong> whichimmigrants negotiate identities <strong>in</strong> various social, political, <strong>and</strong> personal spaces. She isespecially concerned with issues of equity, equality, <strong>and</strong> social justice. Her previousresearch backgrounds <strong>in</strong>clude 18 th ‐ <strong>and</strong>19 th ‐century British Literature <strong>and</strong> early Easternliterature, as well as African‐American literature. Her <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> literature partnered withher experiences as an ESL student <strong>and</strong> immigrant, <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> various cultures, <strong>and</strong> passionfor teach<strong>in</strong>g, are the driv<strong>in</strong>g forces beh<strong>in</strong>d her research <strong>in</strong> literacy studies.Juanjuan Zhu is a doctoral student <strong>in</strong> Curriculum <strong>and</strong> Instruction at Utah State University.Her research <strong>in</strong>terests are foreign/second language education, human rights education,<strong>and</strong> comparative analysis of citizenship education through language classrooms betweenCh<strong>in</strong>a <strong>and</strong> the US.

IntroductionSerafín M. CoronelMol<strong>in</strong>aBita H. ZakeriThe <strong>Work<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Papers</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Literacy</strong>, <strong>Culture</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Language</strong> <strong>Education</strong> (WPLCLE) is an annualpeer‐reviewed onl<strong>in</strong>e publication that provides a forum for faculty <strong>and</strong> students to publishresearch papers with<strong>in</strong> a conceptual framework that values the <strong>in</strong>tegration of theory <strong>and</strong>practice <strong>in</strong> the field of <strong>Literacy</strong>, <strong>Culture</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Language</strong> <strong>Education</strong>. The mission of thisjournal is twofold: (1) to promote the exchange of ideas <strong>and</strong> dissem<strong>in</strong>ation of research, <strong>and</strong>(2) to facilitate academic exchange between students, faculty, <strong>and</strong> scholars from around theworld.Publications <strong>in</strong> WPLCLE are full‐length articles deal<strong>in</strong>g with the follow<strong>in</strong>g areas ofresearch: first‐ <strong>and</strong> second‐language acquisition, macro‐ <strong>and</strong> micro‐sociol<strong>in</strong>guistics <strong>in</strong>education, l<strong>in</strong>guistic anthropology <strong>in</strong> education, language policy <strong>and</strong> plann<strong>in</strong>g from local<strong>and</strong> global perspectives, language revitalization, pragmatics <strong>in</strong> language teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g, literacy, biliteracy <strong>and</strong> multiliteracy, hybrid literacies, bil<strong>in</strong>gual education,multil<strong>in</strong>gual <strong>and</strong> multicultural education, classroom research on language <strong>and</strong> literacy,discourse analysis, technology <strong>in</strong> language teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g, language <strong>and</strong> gender,language teach<strong>in</strong>g professional development, quantitative <strong>and</strong> qualitative research onlanguage <strong>and</strong> literacy education, language related to curriculum design, assessment <strong>and</strong>evaluation, English as a foreign or second language, multimodal literacies, new literacies orelectronic/media/digital literacies. Among other areas of publication <strong>in</strong>terest of theWPLCLE are the New <strong>Literacy</strong> Studies, home <strong>and</strong> workplace literacy, <strong>in</strong>digenous literaciesof the Americas, sociocultural approaches to language <strong>and</strong> literacy education, secondlanguage<strong>in</strong>struction <strong>and</strong> second‐language teacher education, literacy as social practice,critical literacy, early literacy, practitioner <strong>in</strong>quiry/teacher research, children’s literacy,African‐American literacies, Lat<strong>in</strong>o/Hispanic literacies, cross‐l<strong>in</strong>guistic <strong>and</strong> cross‐culturalliteracy practices, heritage language <strong>and</strong> culture ma<strong>in</strong>tenance <strong>and</strong> loss, <strong>and</strong> local <strong>and</strong> global(transnational) literacies.This volume marks the first collection of fourteen essays <strong>and</strong> one book reviewchosen from an array of submissions for our <strong>in</strong>augural 2012 publication. The papers areorganized thematically as follows: (1) <strong>Language</strong>, <strong>Culture</strong>, Identity, <strong>and</strong> Bil<strong>in</strong>gualism; (2)<strong>Literacy</strong> Studies; <strong>and</strong> (3) English as a Second <strong>and</strong> Foreign <strong>Language</strong>. With<strong>in</strong> these thematicunits, the articles are organized accord<strong>in</strong>g to related topics.The first thematic unit, <strong>Language</strong>, <strong>Culture</strong>, Identity, <strong>and</strong> Bil<strong>in</strong>gualism, is comprised offive articles that together cover topics rang<strong>in</strong>g transnationally from the Americas toEurope, the Middle East, <strong>and</strong> Africa. The first article of this section, entitled “Inga <strong>Language</strong><strong>and</strong> <strong>Culture</strong> Revitalization <strong>in</strong> Putumayo, Colombia,” is a collaborative work written byPAGE | 1

INTRODUCTION PAGE | 2Valerie Cross <strong>and</strong> Serafín M. Coronel‐Mol<strong>in</strong>a. This essay discusses the rise of <strong>and</strong> concernwith Quechua language ma<strong>in</strong>tenance due to an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> Quechua–Spanish bil<strong>in</strong>gualism<strong>and</strong> the use of Spanish with<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>digenous communities <strong>and</strong> classrooms. Based on research<strong>in</strong> second language acquisition (SLA), language revitalization, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>tercultural bil<strong>in</strong>gualeducation, this work highlights suggestions to improve recent efforts to overcome themany overt <strong>and</strong> covert challenges to bil<strong>in</strong>gual education implementation <strong>in</strong> Putumayo,Colombia. This article attempts to br<strong>in</strong>g such forms of resistance to the surface <strong>and</strong> providesuggestions for overcom<strong>in</strong>g them, <strong>in</strong> hopes of facilitat<strong>in</strong>g the grassroots‐<strong>in</strong>itiated languagepolicy <strong>and</strong> plann<strong>in</strong>g goals of cultural revitalization <strong>and</strong> language shift reversal that arealready <strong>in</strong> place.The second article, “Background <strong>and</strong> Motivation of Students Study<strong>in</strong>g a NativeAmerican <strong>Language</strong> at the University Level,” by Juliet Morgan, follows first‐ through fourthsemesteruniversity‐level Native American language learners at the University ofOklahoma. The data for this study was collected through a survey designed to discover whois enroll<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Cherokee, Cheyenne, Choctaw, Muscogee Creek, <strong>and</strong> Kiowa at the Universityof Oklahoma, <strong>and</strong> why these <strong>in</strong>dividuals choose to study these languages. The study workstoward an underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of whether these students are motivated by <strong>in</strong>tegrative or<strong>in</strong>strumental factors <strong>and</strong> how underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g these students’ backgrounds <strong>and</strong> motivationscan <strong>in</strong>form teach<strong>in</strong>g methods.The third article, “Complexities of Immigrant Identity: Issues of <strong>Literacy</strong>, <strong>Language</strong>,<strong>and</strong> <strong>Culture</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Formation of Identity” by Bita H. Zakeri, is primarily concerned with thesocial struggles of immigrant <strong>and</strong> ESL students with language, identity, <strong>and</strong> culture. Thiswork discusses some of the major hurdles faced by immigrants <strong>in</strong> English‐speak<strong>in</strong>gsocieties <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> academic <strong>in</strong>stitutions as they struggle to adapt to a new social sphere, <strong>and</strong>change, lose, <strong>and</strong> ga<strong>in</strong> new identities. Us<strong>in</strong>g autoethnographical data <strong>and</strong> literature <strong>in</strong> thisarea, Zakeri discusses issues of immigrant identity <strong>and</strong> literacy from a twofold perspective:(a) a lack of attention to immigration <strong>and</strong> acculturation phenomena; <strong>and</strong> (b) theimportance of underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g immigrant students’ experiences <strong>and</strong> the need fordiversification of teachers <strong>and</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g methods.The fourth article, “Students Writ<strong>in</strong>g across <strong>Culture</strong>s: Teach<strong>in</strong>g Awareness ofAudience <strong>in</strong> a Co‐curricular Service Learn<strong>in</strong>g Project” by Beth Lewis Samuelson <strong>and</strong> JamesChamwada Kigamwa, exam<strong>in</strong>es a model for out‐of‐school literacy <strong>in</strong>struction us<strong>in</strong>gavailable l<strong>in</strong>guistic <strong>and</strong> cultural models for teach<strong>in</strong>g audience awareness across cultures.The literacy model described engages undergraduate <strong>and</strong> secondary students <strong>in</strong> a crossculturalstory‐tell<strong>in</strong>g exchange <strong>and</strong> calls for anticipat<strong>in</strong>g the needs of young readers who donot share l<strong>in</strong>guistic or cultural backgrounds. Samuelson <strong>and</strong> Kigamwa outl<strong>in</strong>e the processof help<strong>in</strong>g the writers to underst<strong>and</strong> their Rw<strong>and</strong>an audience, <strong>and</strong> highlight some of thel<strong>in</strong>guistic <strong>and</strong> cultural issues that arose <strong>in</strong> the early drafts <strong>and</strong> persisted throughout theedit<strong>in</strong>g process despite direct feedback. Through workshops they discussed availablel<strong>in</strong>guistic <strong>and</strong> cultural designs; <strong>in</strong> their research, they track some of the responses of thewriters. The paper closes with exam<strong>in</strong>ation of a story from the third volume for evidencethat the writers had addressed the needs of the Rw<strong>and</strong>an readers <strong>in</strong> their stories.The fifth article, “The Curriculum as <strong>Culture</strong>s <strong>in</strong> Conflict: Explor<strong>in</strong>g Monocultural<strong>and</strong> Multicultural Ideologies through the Case of Bil<strong>in</strong>gual <strong>Education</strong>” by Juanjuan Zhu <strong>and</strong>

PAGE | 3 INTRODUCTIONSteven P. Camicia, argues that curriculum contentions are cultural struggles. To illustratethis issue, they exam<strong>in</strong>e contention surround<strong>in</strong>g which <strong>and</strong> how languages are taught <strong>in</strong> thecurriculum. Zhu <strong>and</strong> Camicia locate this struggle with<strong>in</strong> their positionalities, as a departurepo<strong>in</strong>t for their analysis of compet<strong>in</strong>g ideologies surround<strong>in</strong>g language <strong>and</strong> curriculum.Us<strong>in</strong>g a dialogical methodology to exam<strong>in</strong>e tensions between monocultural <strong>and</strong>multicultural ideologies, the authors provide an illustration through an imag<strong>in</strong>ary dialoguebetween them, Eric D. Hirsch, <strong>and</strong> Mikhael Bakht<strong>in</strong>. Based on the struggles located <strong>in</strong> thebodies of the authors <strong>and</strong> the imag<strong>in</strong>ary dialogue of two cultural theorists, they concludethat a monological curriculum represents the dom<strong>in</strong>ation of one cultural group over others,rather than confirm<strong>in</strong>g the pedagogical <strong>and</strong> social rationales provided by opponents ofmultil<strong>in</strong>gual education.The second thematic unit of this volume, called <strong>Literacy</strong> Studies, is composed of sixarticles that cover a spectrum of issues <strong>in</strong> this area. The first of the articles <strong>in</strong> this section(effectively the sixth of the issue), entitled “One Story, Many Perspectives: Read<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong>Writ<strong>in</strong>g Graphic Novels <strong>in</strong> the Elementary Social Studies Classroom,” by Erica Christie,exam<strong>in</strong>es the ways elementary students underst<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> retell a complex social studiesstory us<strong>in</strong>g multiple textual formats. Third‐grade students were exposed to a picture book<strong>and</strong> graphic novel version of the true story of Alia Muhammad Baker, a courageous Iraqilibrarian. After reflect<strong>in</strong>g on the texts, students re‐narrated the story; many chose to writegraphic novels. Students expressed high levels of <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> graphic novels, exhibited newperspectives on the Iraq War <strong>and</strong> active citizenship, <strong>and</strong> utilized key features of graphicnovels to tell complex <strong>and</strong> multilayered social stories.The seventh article is entitled “St<strong>and</strong>ard Written Academic English: A CriticalAppraisal,” by Laura (Violeta) Colombo. In this essay, Colombo applies the postulates ofGramsci, Bourdieu <strong>and</strong> Canagarajah to show how dom<strong>in</strong>ant structures arereproduced <strong>in</strong> scientific communication worldwide. Colombo argues that thesestructures do not allow nondom<strong>in</strong>ant epistemologies <strong>and</strong> ways of produc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong>communicat<strong>in</strong>g science to participate <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>ternational arena. She proposes thata critical appraisal of each of the terms present <strong>in</strong> SWAE is the first step towards amore democratic conceptualization of science communication, where thest<strong>and</strong>ards are seen not only as <strong>in</strong>nocuous means of communication but also asideologically charged fictitious universals.The eighth article, “A Skype‐Buddy Model for Blended Learn<strong>in</strong>g,” coauthoredby Carmen E. Macharaschwili <strong>and</strong> L<strong>in</strong>da Skidmore Cogg<strong>in</strong>, explores thebenefits of onl<strong>in</strong>e learn<strong>in</strong>g. The authors discuss onl<strong>in</strong>e learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> higher education<strong>and</strong> some of the challenges universities face <strong>in</strong> provid<strong>in</strong>g students with qualityeducation experiences through distance learn<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> meet<strong>in</strong>g the students’ needsfor engagement <strong>and</strong> challenge with<strong>in</strong> a collaborative framework. They proposeways that Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) could be used to provide face‐to‐faceparticipation <strong>in</strong> a traditional classroom us<strong>in</strong>g a unique “Skype buddy” system. Theauthors exam<strong>in</strong>e experiences related to the satisfaction, benefits, challenges, <strong>and</strong>surprises of each of the participants (Skype buddies, professors, <strong>and</strong> otherstudents <strong>in</strong> the class) <strong>in</strong> two doctoral sem<strong>in</strong>ars.

INTRODUCTION PAGE | 4The n<strong>in</strong>th essay, “Look<strong>in</strong>g for Children Left Beh<strong>in</strong>d: American <strong>Language</strong> Policies <strong>in</strong> aMultil<strong>in</strong>gual World” by Suparna Bose, discusses ramifications of the 2010 Census reports, asubstantial <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> language‐m<strong>in</strong>ority populations, <strong>and</strong> the atmosphere of distrusttowards bil<strong>in</strong>gual <strong>and</strong> bidialectal people felt by ma<strong>in</strong>stream American society. The authorexam<strong>in</strong>es the process of assimilation, immersion, <strong>and</strong> silenc<strong>in</strong>g of immigrant/m<strong>in</strong>oritycultures, result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the loss of their identity. Bose argues that the negative effects of thisloss can be observed <strong>in</strong> lower self‐esteem, lower grades, <strong>and</strong> ris<strong>in</strong>g school dropout rates oflanguage‐m<strong>in</strong>ority children today. She then recommends ways to <strong>in</strong>crease themarketability of future American citizens, both monol<strong>in</strong>gual <strong>and</strong> bil<strong>in</strong>gual, <strong>in</strong> an era ofglobalization <strong>and</strong> the plurality of the English language.The last article of the second thematic unit is “<strong>Literacy</strong> Programs for IncarceratedYouth <strong>in</strong> the US.” This article, written by Diana Brace, collects <strong>and</strong> analyzes research onliteracy programs <strong>in</strong> juvenile correctional facilities. Her research uncovers a troubled<strong>in</strong>stitution lack<strong>in</strong>g resources <strong>and</strong> clear solutions. Brace suggests that this reveals the needfor new approaches to research on <strong>in</strong>carcerated youths’ literacy learn<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> calls forresearch that <strong>in</strong>vestigates how the literacy identities of <strong>in</strong>carcerated youth can be utilizedto <strong>in</strong>crease literacy learn<strong>in</strong>g both with<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> outside the correctional facility. The authorfurther suggests that this goal could best be achieved under a theoretical framework<strong>in</strong>formed by the theories of Bakht<strong>in</strong>, Freire, <strong>and</strong> Peck, Flower, <strong>and</strong> Higg<strong>in</strong>s.The third <strong>and</strong> f<strong>in</strong>al thematic unit, entitled English as a Second <strong>and</strong> Foreign <strong>Language</strong>,is composed of four articles. The first of these, article number eleven <strong>in</strong> the issue, is entitled“Strategy‐Based Read<strong>in</strong>g Instruction Utiliz<strong>in</strong>g the CALLA Model <strong>in</strong> an ESL/EFL Context,” byYoung‐Mee Suh. It explores four English read<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>structional approaches that areprimarily used <strong>in</strong> ESL/EFL read<strong>in</strong>g classes: Experience‐Text‐Relationship, ReciprocalTeach<strong>in</strong>g Approach, Transactional Strategy Instruction, <strong>and</strong> the Cognitive Academic<strong>Language</strong> Learn<strong>in</strong>g Approach. Each read<strong>in</strong>g approach is based on read<strong>in</strong>g strategy<strong>in</strong>struction, <strong>and</strong> students are considered active learners <strong>in</strong> these paradigms. Target<strong>in</strong>gpostsecondary school students whose English read<strong>in</strong>g proficiency levels are between<strong>in</strong>termediate <strong>and</strong> high‐<strong>in</strong>termediate, the author illustrates each stage of the CALLA<strong>in</strong>structional model <strong>and</strong> provides a sample lesson plan. ESL/EFL teachers may utilize thedemonstration or the lesson plan <strong>in</strong> a real teach<strong>in</strong>g situation to help learners be successfulESL/EFL readers while <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g their content knowledge <strong>and</strong> language proficiency.The twelfth article, “The Challenges of Teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> Learn<strong>in</strong>g English Literature <strong>in</strong>the L2 Context: The Case of Junior Secondary Schools <strong>in</strong> Botswana” by Deborah Aden<strong>in</strong>hunAdeyemi, discusses the ways various Motswana policy documents have advocated for anenlightened <strong>and</strong> well‐<strong>in</strong>formed society <strong>and</strong> the provision of a ten‐year basic education as afundamental human right of the country’s citizens. It is aga<strong>in</strong>st this background that thepaper discusses the importance of English literature <strong>in</strong> the Junior Secondary School (JSS)curriculum <strong>and</strong> exam<strong>in</strong>es the challenges faced by teachers <strong>and</strong> students <strong>in</strong> theteach<strong>in</strong>g/learn<strong>in</strong>g process that can hamper the achievement of the country’s educational<strong>and</strong> social goals.The thirteenth article, “The Effectiveness of Correct<strong>in</strong>g Grammatical Errors <strong>in</strong>Writ<strong>in</strong>g Classes: An EFL Teacher’s Perspective” by Hye‐Kyung Kim, reveals that the role ofgrammar <strong>in</strong>struction to help students reduce errors <strong>in</strong> L2 writ<strong>in</strong>g is under debate: Truscott

PAGE | 5 INTRODUCTIONclaims that error correction is largely <strong>in</strong>effective <strong>and</strong> harmful, whereas Ferris argues thatstudents need feedback on their grammatical errors. Kim emphasizes that grammarcorrection is considered to be one of the most important forms of feedback. This chapterexam<strong>in</strong>es the role of grammar correction <strong>in</strong> L2 writ<strong>in</strong>g on the basis of these controversies<strong>and</strong> discusses some pedagogical implications of error correction for teach<strong>in</strong>g writ<strong>in</strong>g, withparticular reference to her own experience of teach<strong>in</strong>g EFL writ<strong>in</strong>g classes <strong>in</strong> South Korea.The f<strong>in</strong>al article, “Undocumented Mexican Immigrants <strong>in</strong> Adult ESL Classrooms:Some Issues to Consider” by Sheri Jordan, argues that with anti‐immigrant sentimentspermeat<strong>in</strong>g the media, policy, <strong>and</strong> public discourse throughout the United States, littleroom seems to exist for underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g what drives Mexican migrants northward. Jordanframes her argument with<strong>in</strong> a discussion of the historical conditions lead<strong>in</strong>g to USimmigration policy, negative discourses <strong>and</strong> stereotypes <strong>in</strong> the American media <strong>and</strong> public,<strong>and</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g Mexican migration <strong>in</strong> spite of great sacrifice, <strong>and</strong> the choices of <strong>in</strong>dividualsto migrate to the US. Educators of adult ESL students need a framework, which the authoroutl<strong>in</strong>es, as they encounter these students <strong>in</strong> the classroom. This framework comb<strong>in</strong>esFreire’s “pedagogy of the oppressed” with a transformative pedagogy that rel<strong>in</strong>quishesdeficit models <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>vites student knowledge <strong>in</strong>to the classroom.This first volume of WPLCLE ends with a book review by Craig Howard on the bookentitled <strong>Language</strong> Learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> Teacher <strong>Education</strong>: A Sociocultural Approach, edited byMargaret Hawk<strong>in</strong>s. Howard provides an <strong>in</strong>‐depth review of the articles <strong>in</strong> this collection,highlight<strong>in</strong>g the book’s value for researchers <strong>and</strong> practitioners of language teach<strong>in</strong>g.

LANGUAGE, CULTURE, IDENTITY, ANDBILINGUALISM

Inga <strong>Language</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Culture</strong> Revitalization <strong>in</strong> Putumayo,ColombiaValerie CrossSerafín M. CoronelMol<strong>in</strong>aAbstractIncreas<strong>in</strong>g levels of Quechua–Spanish bil<strong>in</strong>gualism <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>creased use of Spanish with<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>digenous communities <strong>and</strong> classrooms have given rise to concern about Quechua languagema<strong>in</strong>tenance (Hornberger, 1988, 1998, 1999; Hornberger & CoronelMol<strong>in</strong>a, 2004). Thepresent <strong>in</strong>vestigation is prelim<strong>in</strong>ary <strong>and</strong> explores the possibility of bil<strong>in</strong>gual <strong>in</strong>terculturaleducation to promote Quechua (Inga) language revitalization <strong>in</strong> the Putumayo region ofColombia. Because of the large role that school<strong>in</strong>g has played <strong>in</strong> the language shift process,Inga language revitalization efforts have focused on implement<strong>in</strong>g use of the Inga language<strong>in</strong> schools. This paper offers suggestions based on research <strong>in</strong> second language acquisition(SLA), language revitalization, <strong>and</strong> bil<strong>in</strong>gual <strong>in</strong>tercultural education to improve recent efforts<strong>and</strong> overcome the many overt <strong>and</strong> covert challenges that exist to bil<strong>in</strong>gual educationimplementation <strong>in</strong> Putumayo, Colombia. This article attempts to br<strong>in</strong>g such forms ofresistance to the surface <strong>and</strong> provide suggestions for overcom<strong>in</strong>g them, <strong>in</strong> hopes of facilitat<strong>in</strong>gthe grassroots<strong>in</strong>itiated language plann<strong>in</strong>g goals of culture revitalization <strong>and</strong> revers<strong>in</strong>glanguage shift that are already <strong>in</strong> place.IntroductionIn the present context of cultural, economic, <strong>and</strong> political globalization, world languageswith <strong>in</strong>ternational status cont<strong>in</strong>ue to ga<strong>in</strong> perceived value, while local languagescorrespond<strong>in</strong>gly lose value or “currency” <strong>in</strong> the global language market (McCarty, 2003).Increas<strong>in</strong>g levels of Quechua–Spanish bil<strong>in</strong>gualism <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>creased use of Spanish with<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>digenous communities <strong>and</strong> classrooms have given rise to concern about Quechualanguage ma<strong>in</strong>tenance (Hornberger, 1988, 1998, 1999; Hornberger & Coronel‐Mol<strong>in</strong>a,2004). The present <strong>in</strong>vestigation is prelim<strong>in</strong>ary, as the authors have not yet conducted fieldwork <strong>in</strong> the Putumayo region of Colombia. The authors draw on other Andean <strong>and</strong> bil<strong>in</strong>gualresearch to explore the possibility of bil<strong>in</strong>gual <strong>in</strong>tercultural education to promote Quechualanguage revitalization <strong>in</strong> the Putumayo region of Colombia. More specifically, the paper isan attempt to portray the present l<strong>in</strong>guistic <strong>and</strong> educational situation of Colombian Ingas,as well as to outl<strong>in</strong>e forms of resistance <strong>and</strong> possibility of bil<strong>in</strong>gual Inga‐Spanish education<strong>in</strong> Putumayo.Follow<strong>in</strong>g a brief overview of Quechua language shift, this paper focuses on the Ingacontext <strong>in</strong> Colombia. The historical role of schools <strong>in</strong> Inga communities, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g their<strong>in</strong>fluence on language shift from Inga to Spanish, will then be addressed. Because of thePAGE | 7

PAGE | 8CROSS & CORONEL‐MOLINAlarge role that school<strong>in</strong>g has played <strong>in</strong> the language shift process, Inga languagerevitalization efforts have focused on implement<strong>in</strong>g the use of the Inga language as amedium (versus as a school subject) <strong>in</strong> schools. The present paper focuses on the result<strong>in</strong>gbil<strong>in</strong>gual education efforts <strong>in</strong> Putumayo, Colombia, highlight<strong>in</strong>g some potentialimpediments <strong>in</strong> the present program <strong>and</strong> curricular design as well as various other formsof resistance to the efforts. Suggestions are made to improve the present bil<strong>in</strong>gualeducation situation based on second language acquisition (SLA), language revitalization,<strong>and</strong> bil<strong>in</strong>gual <strong>in</strong>tercultural education research. While we acknowledge that there existmany overt <strong>and</strong> covert challenges to bil<strong>in</strong>gual education implementation <strong>in</strong> Putumayo, thispaper attempts to br<strong>in</strong>g such forms of resistance to the surface <strong>and</strong> provide suggestions forovercom<strong>in</strong>g them <strong>in</strong> hopes of facilitat<strong>in</strong>g the grassroots‐<strong>in</strong>itiated language plann<strong>in</strong>g goal ofrevers<strong>in</strong>g language shift.Quechua <strong>Language</strong> ShiftIn the midst of comparable histories that <strong>in</strong>clude resist<strong>in</strong>g years of European colonizationattempts, similar experiences <strong>and</strong> challenges have emerged across diverse Quechuaspeak<strong>in</strong>gcommunities. One such challenge has been the function of Spanish as a significanttool of colonization <strong>and</strong> its status as the national language of many of the countries where<strong>in</strong>digenous communities reside (Coronel‐Mol<strong>in</strong>a, 1999, 2007; Hornberger, 1987). <strong>Language</strong>has served as an important means of preservation of Quechua culture <strong>and</strong> civilization aswell as resistance aga<strong>in</strong>st coloniz<strong>in</strong>g forces (Carlosama Gaviria, 2001). In the context of<strong>in</strong>creased contact with the Spanish language <strong>in</strong> the last five centuries, trends of languageshift toward use of Spanish <strong>and</strong> bil<strong>in</strong>gualism have become <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly prevalent (for acomprehensive def<strong>in</strong>ition <strong>and</strong> literature review of language shift, see Coronel‐Mol<strong>in</strong>a,2009).With<strong>in</strong> many Quechua communities, Spanish is commonly learned at a young age,result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> high levels of ‘bil<strong>in</strong>gualism,’ understood here as native‐like productive <strong>and</strong>receptive comm<strong>and</strong> of two languages. Generational differences <strong>in</strong> the occurrence ofbil<strong>in</strong>gualism among <strong>in</strong>digenous persons are vast <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the context of recentescalation of contact with non<strong>in</strong>digenous national populations, due to immigration as wellas other factors (Coronel‐Mol<strong>in</strong>a, 1999; Harvey, 1994; Hornberger, 2000). Quechualanguage ma<strong>in</strong>tenance has become an issue of concern <strong>in</strong> light of the recently <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>grates of language shift away from Quechua (Hornberger, 1988, 1998, 1999; Hornberger &Coronel‐Mol<strong>in</strong>a, 2004).Colombian Inga ContextPresent L<strong>in</strong>guistic RealityAccord<strong>in</strong>g to Colombia’s 2005 census (DANE, 2005), of Colombia’s 41,468,384 totalpopulation, about 3.4% or 1,392,623 are considered ethnically <strong>in</strong>digenous <strong>and</strong> represent avast diversity of <strong>in</strong>digenous groups. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to DANE (2007), 64 American Indianlanguages are spoken <strong>in</strong> Colombia, represent<strong>in</strong>g 13 language families. Inga is one suchlanguage, <strong>and</strong> is spoken by Ingano populations found mostly <strong>in</strong> rural areas <strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> aroundthe Putumayo department of southwest Colombia as well as <strong>in</strong> urban areas such as Bogotá.The ethnic population of Ingas is approximately 17,860, <strong>and</strong> the Inga language is one of

INGA LANGUAGE & CULTURE REVITALIZATION PAGE | 9many dialects of Quechua (Ethnologue, 2005). Inga, also known as Highl<strong>and</strong> Inga, is spokenby approximately 16,000 people, 12,000 of whom reside <strong>in</strong> Colombia, mostly <strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> aroundthe department of Putumayo <strong>in</strong> Colombia (Ethnologue, 2005). Ingas <strong>and</strong> other <strong>in</strong>digenousgroups represent 21% of the total population <strong>in</strong> the department of Putumayo (DANE,2005). Despite the laws that have been passed to protect the rights of <strong>in</strong>digenouslanguages, Spanish cont<strong>in</strong>ues to be the official language <strong>in</strong> the state <strong>in</strong>stitutions of Colombia(<strong>Education</strong> Project, 2003).Inga <strong>Language</strong> Shift <strong>in</strong> the Putumayo RegionSoler Castillo (2003) <strong>in</strong>vestigated degrees of bil<strong>in</strong>gualism <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>digenous (Inga) attitudestoward Spanish <strong>and</strong> the Inga dialect of Quechua <strong>in</strong> the rural Inga town of Santiago <strong>in</strong> thedepartment of Putumayo, Colombia <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> the urban area of Santafé <strong>in</strong> the department ofBogotá, Colombia. The comparison of these two locations resulted from hypotheses that theIngas <strong>in</strong> Bogotá, most of whom migrated from Santiago, are los<strong>in</strong>g their language <strong>and</strong>culture at an accelerated rate compared to their rural counterparts due to the <strong>in</strong>creasedcontact with the city culture. In her research, Soler Castillo found similar generationaltrends <strong>in</strong> comm<strong>and</strong> of the Inga language <strong>in</strong> both locations. The adults (older than 26) arefully bil<strong>in</strong>gual Inga–Spanish, <strong>and</strong> the youth (15–25 years) <strong>and</strong> children (9–14 years) are notconsidered fully bil<strong>in</strong>gual because though they have good comprehension of Inga, theyspeak it <strong>in</strong>frequently. Adults have proficiency <strong>in</strong> both languages but prefer to speak Inga <strong>in</strong>the majority of contexts, <strong>and</strong> younger members prefer to use Spanish <strong>in</strong> almost all contexts.Despite the stark generational division <strong>in</strong> bil<strong>in</strong>gualism <strong>and</strong> language use found among IngaQuechua speakers of these communities, Soler Castillo describes the general l<strong>in</strong>guisticattitudes toward both Inga <strong>and</strong> Spanish as very positive across ages.The recent shift toward use of Spanish over Inga <strong>in</strong> various contexts reflects political<strong>and</strong> cultural pressures <strong>and</strong> may be cause for concern <strong>in</strong> terms of Inga languagepreservation. Social dynamics <strong>and</strong> language choice are complicated even further for themany Ingas that migrate to urban areas <strong>in</strong> search of work (Soler Castillo, 2003). Due togreater contact with Spanish speakers, Inga families liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> urban areas communicatemostly <strong>in</strong> Spanish or a form of Inga laced with Spanish loan words <strong>and</strong> syntax, whereasthose <strong>in</strong> rural areas have a tendency to communicate <strong>in</strong> Inga (<strong>Education</strong> Project, 2003).With<strong>in</strong> families with higher education levels, as well as <strong>in</strong> families with one non<strong>in</strong>digenousparent, Spanish tends to be the primary language spoken. Inga children raised <strong>in</strong> ahousehold <strong>in</strong> which they have extensive contact with the gr<strong>and</strong>parents or elders of thefamily have the highest probability of grow<strong>in</strong>g up bil<strong>in</strong>gual (<strong>Education</strong> Project, 2003).Role of School<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Inga <strong>Language</strong> ShiftThe shift <strong>in</strong> language use from Quechua to Spanish is especially evident upon exam<strong>in</strong>ationof the use of the two languages with<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>digenous classrooms. School<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> colonialcontexts is one specific doma<strong>in</strong> where the dom<strong>in</strong>ant language is often <strong>in</strong>stantiated at theexpense of the <strong>in</strong>digenous languages present <strong>in</strong> the society (Coronel‐Mol<strong>in</strong>a, 1999, 2007).Schools run by members of the coloniz<strong>in</strong>g society have historically served as a tool ofcolonization <strong>and</strong> have played an important role <strong>in</strong> promot<strong>in</strong>g language shift toward thelanguage of colonization (Carlosama Gaviria, 2001; Hornberger, 1987). Carlosama Gaviria(2001) describes the <strong>in</strong>stantiation of school<strong>in</strong>g by members of the dom<strong>in</strong>ant, coloniz<strong>in</strong>g

PAGE | 10 CROSS & CORONEL‐MOLINApopulation as a tool of submission <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>tegration of <strong>in</strong>digenous groups <strong>in</strong>to the majoritysociety. He claims that this coloniz<strong>in</strong>g attempt is realized through methods <strong>and</strong> strategiesaimed at ridd<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>digenous pupils of their cultural identities <strong>in</strong> favor of adoption of thenational majority culture, which is thought or claimed to be more civilized.In light of the sociohistorical context of many <strong>in</strong>digenous populations, one canunderst<strong>and</strong> more completely the role that schools have historically had, <strong>and</strong> the embeddedideologies <strong>and</strong> expectations of the role of schools with<strong>in</strong> communities. As most schools <strong>in</strong>these particular Quechua communities were founded for the sole purpose of teach<strong>in</strong>gcommunity members Spanish <strong>and</strong> were to be ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed as separate entities from the restof the community, it is not surpris<strong>in</strong>g that all teach<strong>in</strong>g has historically been conducted <strong>in</strong>Spanish <strong>and</strong> the school is ideologically <strong>and</strong> physically positioned on the periphery of thecommunity. As has been observed <strong>in</strong> other Andean <strong>and</strong> non‐Andean language revitalizationcontexts, such position<strong>in</strong>g can negatively affect student learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> deter <strong>in</strong>digenouscommunity member <strong>in</strong>volvement <strong>in</strong> education <strong>and</strong> curriculum plann<strong>in</strong>g affect<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>digenous children (García, 2005; Harvey, 1994).Schools <strong>in</strong> Inga communities <strong>in</strong> the Putumayo Valley of Colombia are no differentfrom those highlighted above, hav<strong>in</strong>g long been associated with colonization. <strong>Education</strong>al<strong>in</strong>stitutions have contributed to the hegemony of the Spanish language with<strong>in</strong> the<strong>in</strong>digenous communities of Colombia. In the case of the Inga communities <strong>in</strong> the Putumayoregion, the mission of assimilation has been enacted through board<strong>in</strong>g schools <strong>in</strong> whichteach<strong>in</strong>g is exclusively <strong>in</strong> Spanish, children are separated from their families <strong>and</strong> culture,<strong>and</strong> use of traditional Inga dress <strong>and</strong> the Inga language have been prohibited <strong>and</strong> replacedby ma<strong>in</strong>stream Spanish language <strong>and</strong> culture (<strong>Education</strong> Project, 2003). As outl<strong>in</strong>ed byFishman (1991), attempts to distance <strong>in</strong>digenous students from their culture can be apowerful tool <strong>in</strong> reduc<strong>in</strong>g symbolic power <strong>and</strong> agency, especially coupled with bann<strong>in</strong>g useof the native language (Bourdieu 1991). School<strong>in</strong>g historically based on colonization <strong>and</strong>taught by non<strong>in</strong>digenous outsiders had <strong>and</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>ues to have many important implicationsfor language medium <strong>and</strong> classroom curricula. As Carlosama Gaviria (2001) asserts,teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Colombia has been based on one model with the objective of “civiliz<strong>in</strong>g” <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>struct<strong>in</strong>g the “Indian” about how to <strong>in</strong>tegrate <strong>in</strong>to the national society.With<strong>in</strong> the context of vary<strong>in</strong>g levels of bil<strong>in</strong>gualism, both <strong>in</strong>digenous <strong>and</strong>non<strong>in</strong>digenous teachers <strong>in</strong> Inga schools use Spanish as the mode of <strong>in</strong>struction. The Ingastudents from rural communities who do not know Spanish are at an early disadvantage <strong>in</strong>the Spanish‐dom<strong>in</strong>ated educational system. As Hornberger (2006) po<strong>in</strong>ts out based onresearch with Quechua communities <strong>in</strong> Puno, Peru, attribution of a naturally shy <strong>and</strong>reserved personality to Quechua children discounts <strong>and</strong> veils the possibility that thesechildren may be quiet <strong>in</strong> the classroom due to the language barrier that many experience.The early disadvantage is evident <strong>in</strong> the frequent obligation of Inga‐speak<strong>in</strong>g students torepeat primary grades, especially the first year of school (<strong>Education</strong> Project, 2003). Whilesome of these students do learn Spanish as a second language eventually (at least oralcommunication skills), the early school<strong>in</strong>g experiences <strong>in</strong> a language they do notunderst<strong>and</strong> coupled with the dem<strong>and</strong> that they repeat grades are likely to contribute tonegative school attitudes <strong>and</strong> a high drop‐out rate. The frequent occurrence of early dropoutamong Inga schoolchildren may be reflected <strong>in</strong> the drastically higher population of

INGA LANGUAGE & CULTURE REVITALIZATION PAGE | 11students <strong>in</strong> the first grade (more than 100) <strong>and</strong> relatively few students enrolled <strong>in</strong> the sixthgrade or beyond (less than 20) (<strong>Education</strong> Project, 2003).<strong>Language</strong> Revitalization<strong>Language</strong> policy <strong>and</strong> plann<strong>in</strong>g (LPP) efforts have been explored <strong>and</strong> theorized by manyscholars <strong>in</strong> a variety of contexts (Canagarajah, 2005; Cooper, 1989; Fishman, 1991; H<strong>in</strong>ton& Hale, 2001; Kaplan, 1994; Kaplan & Baldauf, 1997; McCarty, 2011; Ricento, 2006, amongothers). Concern about language shift <strong>and</strong> death, <strong>and</strong> the possibility of revers<strong>in</strong>g languageshift <strong>and</strong> of revitalization of endangered languages have become a major focus <strong>in</strong> LPPresearch (Crystal, 2000; Fishman, 1991; Grenoble <strong>and</strong> Whaley, 2006; H<strong>in</strong>ton <strong>and</strong> Hale,2001). Follow<strong>in</strong>g Coronel‐Mol<strong>in</strong>a’s (1999, 2007) framework of language shift <strong>in</strong> particularsocial doma<strong>in</strong>s, language revitalization is def<strong>in</strong>ed by K<strong>in</strong>g (2001) as “the attempt to addnew l<strong>in</strong>guistic forms or social functions to an embattled m<strong>in</strong>ority language with the aim of<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g its uses or users” (p. 23). This notion of revitalization of languages that havebeen threatened or partially lost implies a situated context of multiple languages assignedunequal degrees of power or status. For these reasons, <strong>in</strong>digenous language plann<strong>in</strong>g mustalso <strong>in</strong>corporate plann<strong>in</strong>g for the other, often “dom<strong>in</strong>ant” language(s) present <strong>in</strong> thecontext (Hornberger, 2006; Karam, 1974). In contrast to the notion of languagema<strong>in</strong>tenance, which focuses more on ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> strengthen<strong>in</strong>g immigrant <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>digenous languages, language revitalization requires deliberate efforts by the speakers ofthe language <strong>and</strong> tends to orig<strong>in</strong>ate with<strong>in</strong> the speech communities (Fishman, 1991;Hornberger, 2006). Hornberger <strong>and</strong> K<strong>in</strong>g (1996) also emphasize the necessity of<strong>in</strong>volvement of present <strong>and</strong> future speakers of a language <strong>in</strong> the process of <strong>in</strong>digenouslanguage revitalization, an <strong>in</strong>volvement that must also be present <strong>in</strong> the implementation ofmultil<strong>in</strong>gual education <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>digenous contexts (see also Hornberger, 2006).Inga <strong>Language</strong> RevitalizationInga language revitalization efforts have emerged largely from the grassroots level, <strong>and</strong> thecommunity‐level concerns about revers<strong>in</strong>g language shift <strong>and</strong> revitaliz<strong>in</strong>g the Ingalanguage have been <strong>in</strong>extricably l<strong>in</strong>ked to cultural revitalization concerns. Also, languagerevitalization efforts <strong>in</strong> the Putumayo have centered around the <strong>in</strong>corporation of Inga <strong>in</strong>the community schools. For that reason, it is logical to exam<strong>in</strong>e the history of the efforts tochange the school<strong>in</strong>g context along with the accompany<strong>in</strong>g national policies that havesupported these efforts. Cultural revitalization efforts will also be briefly addressed,followed by a section <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g a more critical exam<strong>in</strong>ation of the bil<strong>in</strong>gual educationefforts <strong>in</strong> the Putumayo.In the 1970s <strong>and</strong> 1980s, grassroots movements <strong>in</strong>volved people with<strong>in</strong> the Ingacommunity voic<strong>in</strong>g a need to establish their own educational system, one that is culturallyrelevant for <strong>in</strong>digenous students <strong>and</strong> which <strong>in</strong>corporates the Inga language <strong>in</strong> thecurriculum. Musu Runakuna (“New People”) is among the <strong>in</strong>digenous organizations thathave called for research <strong>and</strong> support for improv<strong>in</strong>g education with<strong>in</strong> their communities,<strong>and</strong> specifically for the <strong>in</strong>corporation of Inga <strong>in</strong> community schools (T<strong>and</strong>ioy Jansasoy,personal communication, November 3, 2008). This is often referred to as “etnoeducación”(ethno‐education) <strong>in</strong> Colombia, <strong>and</strong> as Educación Intercultural Bil<strong>in</strong>güe (“InterculturalBil<strong>in</strong>gual <strong>Education</strong>”) <strong>in</strong> other Spanish‐speak<strong>in</strong>g countries (Carlosama Gaviria, 2001).

PAGE | 12 CROSS & CORONEL‐MOLINAAddress<strong>in</strong>g the lack of native Inga teachers <strong>and</strong> consequently the need for preparation of<strong>in</strong>digenous teachers followed.Follow<strong>in</strong>g the grassroots dem<strong>and</strong>s for educational policy change, the nationalgovernment of Colombia passed numerous laws support<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>digenous education. TheGeneral Law of <strong>Education</strong> (Law 115 <strong>in</strong> 1994) <strong>in</strong> Colombia, which followed theConstitutional Reform of 1991, <strong>and</strong> Decree 804 (1995) provided an impetus for support<strong>in</strong>gimproved education <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>digenous communities of Colombia (M<strong>in</strong>isterio de EducaciónNacional, República de Colombia). The need <strong>and</strong> desire for educational improvements <strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>digenous communities, particularly <strong>in</strong> the Inga communities of the Sibundoy Valley, areclearly evident, but actual change <strong>and</strong> development is still <strong>in</strong> the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g stages.Inga <strong>Culture</strong> RevitalizationUnderly<strong>in</strong>g the possibility of language revitalization must be a unified communityconsciousness of the endangered status of the language, <strong>and</strong> efforts to revitalize must be<strong>in</strong>itiated at the grassroots level (Coronel‐Mol<strong>in</strong>a 1999, 2005, 2007; Hornberger & K<strong>in</strong>g1996, 1998, 2001). Grassroots support seems to be dependent upon a valu<strong>in</strong>g of not onlythe <strong>in</strong>digenous language but also of the group’s cultural practices. Fishman (1991)describes cultural dislocation as a disruption of traditional cultural practices oftenresult<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a decrease <strong>in</strong> collective control <strong>in</strong> communities. As previously mentioned,Fishman (1991) asserts that along with social <strong>and</strong> physical/demographic dislocations,cultural dislocations can contribute to a complicated language shift process result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> thereduction of power <strong>and</strong> agency (Bourdieu, 1991). Because of the <strong>in</strong>tricate l<strong>in</strong>k between<strong>in</strong>digenous language <strong>and</strong> cultural identity (Coronel‐Mol<strong>in</strong>a & Qu<strong>in</strong>tero, 2010; Hornberger,1988; Hornberger & Coronel‐Mol<strong>in</strong>a, 2004; Howard, 2007; K<strong>in</strong>g, 2000), <strong>in</strong>herent <strong>in</strong>language revitalization (<strong>and</strong> multil<strong>in</strong>gual education) efforts must be the promotion ofvalu<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>digenous cultural practices <strong>and</strong> identity.As mentioned above, Inga language revitalization concern <strong>and</strong> efforts are l<strong>in</strong>ked tocultural revitalization, with their success possibly <strong>in</strong>terdependent. In this way, a precursorfor success of bil<strong>in</strong>gual programs which promote the teach<strong>in</strong>g of Inga language <strong>and</strong> cultureis promotion of Inga cultural revitalization. While national laws that promote <strong>and</strong> celebratethe ethnic diversity of Colombia abound, <strong>in</strong>digenous groups still experience muchdiscrim<strong>in</strong>ation. Soler Castillo (2003) discusses the discrim<strong>in</strong>ation that Ingas experience <strong>in</strong>schools <strong>and</strong> communities <strong>in</strong> urban areas like Bogotá. On the grassroots level <strong>in</strong> both urban<strong>and</strong> rural communities, appreciation of the Inga culture must be shared <strong>in</strong> the face ofglobalization <strong>and</strong> the presence of national culture, before unified community support ofbil<strong>in</strong>gual education can flourish. This Inga cultural renaissance or revitalization has beenpromoted by various <strong>in</strong>digenous leaders <strong>and</strong> groups. The Musu Runakuna group has been<strong>in</strong>strumental <strong>in</strong> promot<strong>in</strong>g the rights of Ingas <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> renew<strong>in</strong>g Inga cultural traditionswith<strong>in</strong> communities <strong>in</strong> the Putumayo s<strong>in</strong>ce the 1980s (T<strong>and</strong>ioy Jansasoy, personalcommunication, November 3, 2008). In addition to petition<strong>in</strong>g the government <strong>and</strong>work<strong>in</strong>g for political rights, the Musu Runakuna has consulted elders of the communityabout cultural traditions which they have worked to restore. Along with culturalrevitalization efforts, pockets of grassroots language plann<strong>in</strong>g efforts have emerged topromote Inga language education.