Following Odysseus Not the end of the world Amarna city of light ...

Following Odysseus Not the end of the world Amarna city of light ...

Following Odysseus Not the end of the world Amarna city of light ...

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

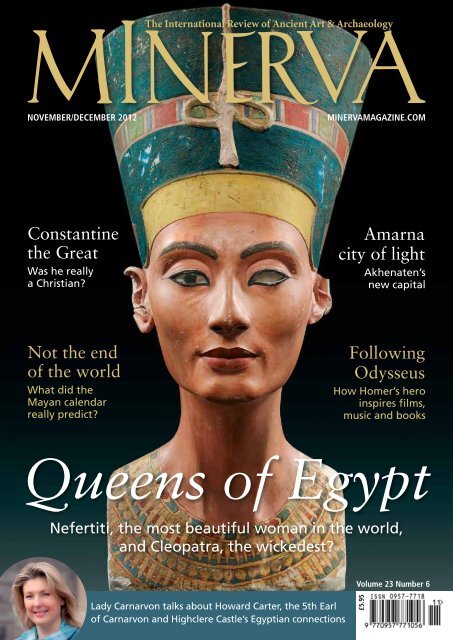

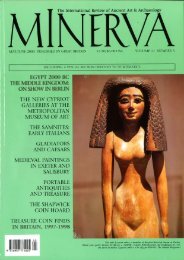

NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2012minervamagazine.comConstantine<strong>the</strong> GreatWas he reallya Christian?<strong>Amarna</strong><strong>city</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>light</strong>Akhenaten’snew capital<strong>Not</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>end</strong><strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>world</strong>What did <strong>the</strong>Mayan cal<strong>end</strong>arreally predict?<strong>Following</strong><strong>Odysseus</strong>How Homer’s heroinspires films,music and booksQueens <strong>of</strong> EgyptNefertiti, <strong>the</strong> most beautiful woman in <strong>the</strong> <strong>world</strong>,and Cleopatra, <strong>the</strong> wickedest?Volume 23 Number 6Lady Carnarvon talks about Howard Carter, <strong>the</strong> 5th Earl<strong>of</strong> Carnarvon and Highclere Castle’s Egyptian connections£5.95

in<strong>the</strong>newsrecent stories from <strong>the</strong> <strong>world</strong> <strong>of</strong> ancient art and archaeologyA Roman shipwreck in AntibesA team <strong>of</strong> French archaeologists from <strong>the</strong>Institut National de RecherchesArchéologiques Préventives (INRAP) haveuncovered a Roman shipwreck in Antibesin what was once part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> bustlingancient port <strong>of</strong> Antipolis. It all started witha routine exploration prior to <strong>the</strong> building<strong>of</strong> an underground car park on <strong>the</strong> site <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> ancient harbour basin, which silted upin antiquity and today is located between<strong>the</strong> modern marina and <strong>the</strong> ramparts.A preliminary diagnosis carried out in2007 by core-boring (<strong>the</strong> bottom <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ancient port is 4 to 5 metres below today’ssea level) revealed archaeological materialfrom <strong>the</strong> third century BC to roughly <strong>the</strong>sixth century AD, and <strong>the</strong> possibility <strong>of</strong>finding a shipwreck was not ruled out.Excavation proper could only start whenseawater was pumped out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> basin, inearly 2012. Layers <strong>of</strong> sediment wereexamined and numerous objects extracted.Because <strong>the</strong> sediment was below sea level, i<strong>the</strong>lped to preserve organic material such aswood, lea<strong>the</strong>r (used for <strong>the</strong> soles <strong>of</strong> shoes)and cork (stoppers for amphorae). Thewreck itself was uncovered during <strong>the</strong>excavation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> last section, lying on itsside in shallow water (less than 1.60metres below <strong>the</strong> ancient sea level), and<strong>the</strong> preserved section is over 15 metres.In conjunction with <strong>the</strong> Camille JullianCentre, INRAP commissioned a specialistin naval archaeology to analyse andinterpret this important find.The remains consist <strong>of</strong> a keel andseveral hull planks joined toge<strong>the</strong>r bythousands <strong>of</strong> wooden pegs inserted intomortises hollowed out in <strong>the</strong> planks.About 40 transverse ribs (shown right) arelying on top, some fixed to <strong>the</strong> hull bymetal pins. The wood used is mainlyconifer. Parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> hull are reinforced bylead plating held in place by small nails.Tool marks (saw and adze) are also clearlyvisible, as is <strong>the</strong> pitch used to make <strong>the</strong>hull watertight. This was a medium-sizedtrading sailing boat (20-22 metres long, 6-7metres wide, with a hold about 3 metresdeep). The fact that <strong>the</strong> hull was not builtover a frame and that <strong>the</strong> ribs were only<strong>the</strong>re to reinforce it, confirm <strong>the</strong> datingsuggested both by stratigraphy and by <strong>the</strong>ceramics collected near <strong>the</strong> vessel: around<strong>the</strong> second century AD. The ship can beclassified as a typical imperial Roman vesseltrading in <strong>the</strong> western Mediterranean. Thewreck has been taken apart and sent <strong>of</strong>f to<strong>the</strong> ARC-Nucléart laboratory in Grenoble,which specialises in treating ancientwaterlogged wood. In 18 months’ time it willbe reassembled and exhibited in Antibes.Nicole BenazethWinner <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Minerva/Peten Travels Prize DrawIn our January/February issue we announceda Prize Draw for a 16-day archaeologicaltour <strong>of</strong> Ancient Anatolia for two (worthover £6,500). Here, <strong>the</strong> lucky winner,Roald Knutsen, describes his trip:‘When I heard that I had been fortunateenough to win <strong>the</strong> Hittites and Phrygianstour arranged by Peten Travels <strong>of</strong> Istanbul(www.petentour.com), I could hardly believemy luck. My personal interest in <strong>the</strong> regionlies in <strong>the</strong> ancient trade routes that led eastalong <strong>the</strong> famed Silk Road, so here was a rareopportunity not to be missed.‘It is difficult to outline briefly all wesaw, as we visited so many importantancient sites scattered across <strong>the</strong> Anatolianplain. But I will say that at each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m– ranging from <strong>the</strong> Phrygian capital <strong>of</strong>Gordion, near <strong>the</strong> tomb <strong>of</strong> King Midas’fa<strong>the</strong>r, to <strong>the</strong> incredible 10,000-year-oldsite <strong>of</strong> Catal Höyük, an ancient <strong>city</strong> whichonce had a population <strong>of</strong> 8,000 people –we were welcomed and guided round <strong>the</strong>mby <strong>the</strong> excavation director himself or asenior archaeologist. Their enthusiasm wasboundless and infectious, and <strong>the</strong>ir patiencewas unexpected and exemplary.‘Besides <strong>the</strong>se two famous excavations,our tour also included Kaman-Kale Höyük,Pteria, Alaca Höyük, ŞSapinuwa, <strong>the</strong> <strong>city</strong>remains <strong>of</strong> Bogazköy-Hattusa, Kültepe andAçik Höyük, <strong>the</strong> neo-Hittite rock relief <strong>of</strong>King Warpalawas at <strong>the</strong> mountain site <strong>of</strong> Ivriz.‘We saw buildings from all periods, ancientto early medieval, temples and o<strong>the</strong>r sacredplaces, ancient sculpture and excellently laidoutmodern museums displaying <strong>the</strong> mostimportant finds. Outstanding for me wasto see one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> three surviving cuneiformtexts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> peace treaty between <strong>the</strong> Hittiteleader Muwatalli and <strong>the</strong> Egyptian pharaohRamesses II after <strong>the</strong> Battle <strong>of</strong> Kadesh.‘Throughout <strong>the</strong> tour, put toge<strong>the</strong>r by MrsIffet Ozgonul, Director <strong>of</strong> Peten Travels,we were accompanied by an excellent andknowledgeable guide and supported byMinerva. If ancient Anatolia interests you,don’t hesitate – book your place now.’Minerva/Peten Travels Prize Draw winner RoaldKnutsen by <strong>the</strong> Sphinx Gate at <strong>the</strong> entrance toAlaca Höyük, a Hittite <strong>city</strong> on <strong>the</strong> Anatolian plain.Photo by Simon Critt<strong>end</strong>enMinerva November/December 20123

in<strong>the</strong>newsLost Roman town resurfacesHaving lain dormant for 1,500 years, <strong>the</strong>town <strong>of</strong> Interamna Lirenas, 50 miles south<strong>of</strong> Rome, has been rediscovered and ischanging scholars’ view <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> nature <strong>of</strong>Roman colonial settlements.Long known about from <strong>the</strong> writings <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> Roman historian Livy and <strong>the</strong> Greekgeographer Strabo, Interamna Lirenas hadalways been seen as a quiet town <strong>of</strong> littleconsequence, which followed <strong>the</strong> standardtemplate <strong>of</strong> urban development. But <strong>the</strong>recent work <strong>of</strong> a collaborative projectinvolving Cambridge University, <strong>the</strong> BritishSchool at Rome, <strong>the</strong> British Academy and<strong>the</strong> Italian State Archaeological Service hasshed more <strong>light</strong> on this supposed backwater.The exact location <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> town, in <strong>the</strong>Liri Valley in Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Lazio, was gleanedfrom ancient sources. The fact that it wasstill unexcavated, and was thought tohave developed relatively little during <strong>the</strong>Imperial Roman era, made <strong>the</strong> town anideal candidate to accurately reflectoriginal colonial settlement features.Led by Martin Millett, LaurencePr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Classical Archaeology atCambridge and Fellow <strong>of</strong> FitzwilliamCollege, and Dr Alessandro Launaro,Postdoctoral Fellow at <strong>the</strong> British Academyand Fellow <strong>of</strong> Darwin College, <strong>the</strong> teamknew that a full-scale excavation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>site, which covers more than 25 hectares,would be impractical, so <strong>the</strong>y started withgeophysical mapping.By using a combination <strong>of</strong> scientifictechniques – ground-penetrating radar andmagnetometry – <strong>the</strong> team began to buildup a picture <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> original street plan, andspecific features came to <strong>the</strong> fore.The greatest surprise was <strong>the</strong> appearance<strong>of</strong> a building with radially arranged wallsand tiered seats within, which soonrevealed itself to be a Roman <strong>the</strong>atre.This suddenly changed <strong>the</strong> perception<strong>of</strong> this town as a small settlement.With its dominant temple and forum,Interamna Lirenas distinguishes itselfconsiderably from nearby Fregellae,which is also on <strong>the</strong> Via Latina – <strong>the</strong>principal road leading south-east out <strong>of</strong>Rome – and which was previously thoughtto be a comparable colonial town.Millett explained <strong>the</strong> significance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>find: it challenges <strong>the</strong> formerly held viewthat Rome projected a certain image <strong>of</strong>itself by building all colonial towns to apattern, and hence organising what <strong>the</strong>communities’ priorities would be, a viewthis discovery now challenges.There are hopes that excavation maybegin again in earnest in summer 2013,starting with <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn corner, whichincorporates <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>atre and <strong>the</strong> forum,this would hopefully allow <strong>the</strong> precisedating <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se structures. The local mayorhopes to turn what is know an unassumingstretch <strong>of</strong> farmland into an archaeologicalpark in <strong>the</strong> future.Ge<strong>of</strong>f LowsleyDental detritus reveals useful factsThe idea <strong>of</strong> picking throughsomeone else’s dental detrituswould fill most <strong>of</strong> us withhorror, but it is by doing exactlythis that Christina Warriner,<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Centre for EvolutionaryMedicine at <strong>the</strong> University<strong>of</strong> Zurich, is gleaning valuableinformation about <strong>the</strong> lives<strong>of</strong> Iranian miners who died2,000 years ago.Archaeological geneticistsstudy some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> more unusualelements <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> material remains<strong>of</strong> our ancestors to gain aninsight into <strong>the</strong> past. Fromanimal, plant and bacterialremains to human tissue, boneand teeth, all <strong>the</strong> biomoleculesleft in what was once livingcan pass down a vast amount<strong>of</strong> information about <strong>the</strong>surrounding environment.Warriner explained howmillions <strong>of</strong> threads <strong>of</strong> DNAbelonging to bacteria thatinhabited <strong>the</strong> mouth and throatare captured in dental calculus(commonly called plaque).Extracting and examining<strong>the</strong>se DNA threads should‘allow us to investigate <strong>the</strong>long-term evolutionary history<strong>of</strong> human health and disease,right down to <strong>the</strong> genetic code<strong>of</strong> individual pathogens, and itshould allow us to reconstruct adetailed picture <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> dynamicinterplay between diet, infectionand immunity that occurredthousands <strong>of</strong> years ago’.Her particular area <strong>of</strong> interestis <strong>the</strong> mummies <strong>of</strong> miners from<strong>the</strong> salt mines <strong>of</strong> Chehr Abad,in north-west Iran, dating from<strong>the</strong> 4th century BC to <strong>the</strong> 4thcentury AD. The bodies <strong>of</strong> menwere naturally preserved bydesiccation when <strong>the</strong> salt minescollapsed. Unlike Egyptianmummies, <strong>the</strong>y did not have<strong>the</strong>ir organs removed and,incredibly, some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> tissueis still intact.The aim <strong>of</strong> her project is t<strong>of</strong>ind evidence for an inheritedgenetic trait, a deficiency in<strong>the</strong> enzyme G6PD (glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase),which causes anaemia, aparticularly common conditionin modern-day Iran.It has been postulated thatmany <strong>of</strong> today’s digestivedisorders may be precipitatedby modern food-productiontechniques causing an imbalancein <strong>the</strong> bacteria within <strong>the</strong> gut.It is possible that identifying <strong>the</strong>bacteria carried by our ancestorscould help to determine what isa healthy balance.This type <strong>of</strong> study need not belimited to digestive conditions,however. Warriner explains:‘Diseases and disorders such asperiodontitis, heart disease,allergies and diabetes all have anevolutionary component relatedto <strong>the</strong> fact that we live in adifferent environment to <strong>the</strong> onein which our bodies evolved.’So we may also learn valuablelessons that can help in modernmedical treatment.While dentists tell us to brushour teeth regularly, we arefortunate that those before uswere not schooled in dentalhygiene, as we now have thisinvaluable archaeologicalrecord written in <strong>the</strong>ir plaque.Ge<strong>of</strong>f LowsleyChristina Warriner examines amandible showing dental calculusand ante-mortem tooth loss in aDNA clean labcourtesy <strong>of</strong> Christina Warinner4

Ancient obsidian trade inSyria reflects current conflictDr Ellery Frahm, an archaeologistfrom <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Sheffield,has revealed <strong>the</strong> origin andtrading routes <strong>of</strong> razor-sharpstone tools 4,200 years ago inSyria, where many ancient sitesare under threat due to<strong>the</strong> current conflict.An interdisciplinary researchteam hopes this new discovery,which has major implicationsfor understanding <strong>the</strong> <strong>world</strong>’sfirst empire, will help tohigh<strong>light</strong> <strong>the</strong> importance <strong>of</strong>protecting Syria’s heritage.Obsidian, naturally occurringvolcanic glass, is smooth, hard,and far sharper than a surgicalscalpel when fractured, makingit a highly desirable raw materialfor crafting stone tools duringmost <strong>of</strong> human history. In fact,obsidian tools continued to beused throughout <strong>the</strong> ancientMiddle East for millennia after<strong>the</strong> introduction <strong>of</strong> metals,and obsidian blades are stillused today as scalpels in somespecialised medical procedures.Researchers from socialand earth sciences studiedobsidian tools excavated from<strong>the</strong> archaeological site <strong>of</strong> TellMozan, in Syria. Using newmethods and technologies, <strong>the</strong>team successfully uncovered <strong>the</strong>hi<strong>the</strong>rto unknown origins andmovements <strong>of</strong> this coveted rawmaterial during <strong>the</strong> Bronze Age,more than four millennia ago.Most obsidian at Tell Mozan,and surrounding archaeologicalsites, came from volcanoes some200km away in Eastern Turkey;this can be confirmed by models<strong>of</strong> ancient trade developed byarchaeologists over <strong>the</strong> last fivedecades. However, <strong>the</strong> teamalso discovered a set <strong>of</strong> exoticartefacts made from obsidianoriginating from a volcanoin central Turkey, three timesfur<strong>the</strong>r away. Just as importantas <strong>the</strong>ir distant origin is where<strong>the</strong> artefacts were found: a royalpalace courtyard.They were left <strong>the</strong>re during<strong>the</strong> height <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>world</strong>’s firstempire, <strong>the</strong> Akkadian Empire– <strong>the</strong> Akkadians invaded Syriain <strong>the</strong> Bronze Age. These findshave exciting implications forunderstanding links betweenresources and empires in <strong>the</strong>Middle East.Dr Frahm, Marie CurieExperienced Research Fellowat <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Sheffield’sDepartment <strong>of</strong> Archaeology,who led <strong>the</strong> research said: ‘Thisis a rare, if not unique, discoveryin Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Mesopotamiathat enables new insightsinto changing Bronze Ageeconomics and geopolitics. Wecan identify where an obsidianartefact originated because eachvolcanic source has a distinctive“fingerprint”. This is whyobsidian sourcing is a powerfulmeans <strong>of</strong> reconstructing pasttrade routes, social boundaries,and o<strong>the</strong>r information thatallows us to engage in majorsocial science debates.’<strong>Not</strong> only did Dr Frahm andhis collaborators identify <strong>the</strong>particular volcano where <strong>the</strong>obsidian originated, <strong>the</strong>y wereable to pinpoint two particularareas on <strong>the</strong> exact flank <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>mountain where it was collected.Such specifi<strong>city</strong> was possibleusing a combination <strong>of</strong> scientifictechniques, including a portableX-ray analyser and instrumentsthat measure weak magneticsignals within rocks.The earliest techniques <strong>of</strong>matching Middle East obsidianartefacts to <strong>the</strong>ir volcanicorigins were developed partlyat <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Sheffield byColin Renfrew, Lecturer in <strong>the</strong>Department <strong>of</strong> Prehistory andArchaeology from 1965 to 1972.Dr Frahm commented: ‘Studying<strong>the</strong> use and origin <strong>of</strong> obsidianreveals some compellingparallels with <strong>the</strong> modern-dayMiddle East and has resonancewith issues that <strong>the</strong> region facestoday. For example, we thinkthat invading powers, intent oncontrolling access to valuableresources, would have facedresistance to occupation fromsmall states across <strong>the</strong> regionruled by peoples who wereethnic minorities elsewhere in<strong>the</strong> Middle East.‘A mountain insurgency couldhave resulted in a blockade<strong>of</strong> natural resources, and <strong>the</strong>colonisers may have been forcedto instead seek resources frommore distant sources and forgealliances with o<strong>the</strong>r regionalpowers to raise <strong>the</strong>ir status. Thiswas 4,200 years ago during <strong>the</strong>31Bronze Age – <strong>the</strong> parallels to<strong>the</strong> recent history <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> area areextraordinary. I went to Syria asan American after <strong>the</strong> US hadcalled Syria part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> “Axis<strong>of</strong> Evil”, and only had positiveexperiences <strong>the</strong>re. The degree <strong>of</strong>hospitality I encountered wasextraordinary. Perfect strangerstook me into <strong>the</strong>ir homes duringmy journey from Damascusto <strong>the</strong> site, which involved anine-hour bus-ride through <strong>the</strong>desert. I was welcomed, fed,<strong>of</strong>fered a shower and change<strong>of</strong> clo<strong>the</strong>s, introduced to familyand fri<strong>end</strong>s, and shown around.‘The current situation inSyria is tragic and precarious.It can be so overwhelming andheartbreaking that I have to takea break from it which, unlike <strong>the</strong>people who are living through<strong>the</strong> fighting, I have <strong>the</strong> luxury<strong>of</strong> doing. Whatever <strong>the</strong> futureholds, <strong>the</strong>re will be a lot <strong>of</strong> workto do <strong>the</strong>re, both humanitarianand archaeological, and I’mvery much interested in <strong>the</strong>interfaces between <strong>the</strong>m. Howcan archaeology perhaps helpSyria recover from this?’• Dr Frahm’s original paper ispublished online in <strong>the</strong> Journal<strong>of</strong> Archaeological Research atwww.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305440311004857.University <strong>of</strong> sheffield21. Dr Ellery Frahm, Marie CurieExperienced Research Fellowat <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Sheffield’sDepartment <strong>of</strong> Archaeology.2. Some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ancient obsidianblades, dating from 4,200 yearsago, excavated at <strong>the</strong> site.3. The site <strong>of</strong> Tell Mozan in Syriais situated near <strong>the</strong> border withTurkey and Iraq.Minerva November/December 20125

in<strong>the</strong>newsMystery red head identifiedA fine, Roman, red porphyryhead, recently sold by <strong>the</strong>Temple Gallery in London,has been identified as that <strong>of</strong> aTetrarch, dating from <strong>the</strong> early4th century AD.Because <strong>of</strong> its Julio-Claudianhairstyle, at first glance <strong>the</strong>head appears to belong to <strong>the</strong>beginning <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Roman Imperialperiod, circa 50 BC – circa AD 50.But this retrospective look wasprobably intentional becauseany dynasty, particularly duringinsecure times – and <strong>the</strong>se timeswere indeed insecure – wouldclearly want to proclaim itslegitimacy by linking itself to animpressive imperial lineage.There is a very similarexample in <strong>the</strong> Vatican (exceptthat it is a complete bust) thatis said to be Constantius II(d. 361). This bust, now in<strong>the</strong> Museo Pio Clementi, wasacquired in 1772 from PrincessCornelia Costanza Barberiniso, unlike <strong>the</strong> famous porphyrysarcophagi <strong>of</strong> Constantine andHelena, it cannot be said thatthis item has resided on <strong>the</strong>Vatican Hill since late Romantimes – but that is not to say<strong>the</strong> bust has not been in Romesince it was made. This and<strong>the</strong> London head are closelyrelated, made at <strong>the</strong> same time6and possibly in <strong>the</strong> same atelier,probably in Rome.The style <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Londonhead is quite different to <strong>the</strong>more crude style <strong>of</strong> porphyrysculpture emanating fromEastern Europe – like that<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> massive, full-lengthTetrarchs (scandalously lootedfrom Constantinople in 1204)that now stand outside <strong>the</strong>Duomo in Venice.Roman portraiture hadbecome increasingly lessrealistic by <strong>the</strong> <strong>end</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>3rd century, as easily datablecoins show, and images <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>emperor and members <strong>of</strong> hisfamily were hardly portraits butmore properly representations<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> high <strong>of</strong>fice that <strong>the</strong>y held.The London head is inexcellent condition. The face hasbeen polished in recent times –during <strong>the</strong> Renaissance or later(<strong>the</strong>re is no way <strong>of</strong> knowingexactly when) – but despite this<strong>the</strong> original form has not beenmarkedly altered.Still apparent is <strong>the</strong> e<strong>the</strong>real,ra<strong>the</strong>r dreamy expression <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> eyes and countenance, firstused in AD 313 or shortlybefore, at about <strong>the</strong> timewhen Christianity became <strong>the</strong>Rome’s state religion although,in fact, this look is derivedFour views <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> red porphyry head <strong>of</strong> a Tetrarch recently identified byRichard Falkiner at <strong>the</strong> Temple Gallery in London. This head is related toone in <strong>the</strong> Vatican and two o<strong>the</strong>rs (still attached to <strong>the</strong>ir original pillars)in <strong>the</strong> Louvre. The back view clearly shows how this one was damagedwhen it was wrenched from its column.from posthumous images <strong>of</strong>Alexander <strong>the</strong> Great, who diedin 323 BC, particularly on <strong>the</strong>coins <strong>of</strong> Lysimachus (d. 281 BC).It seems to me that <strong>the</strong>London head is one <strong>of</strong> anoriginal group <strong>of</strong> four; <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rthree being <strong>the</strong> Vatican head andtwo o<strong>the</strong>r busts, still attached to<strong>the</strong>ir original pillars, that are in<strong>the</strong> Louvre. Like <strong>the</strong>m, both <strong>the</strong>Vatican and <strong>the</strong> London headswere also originally attachedto pillars. This is demonstratedby similar damage to <strong>the</strong> back<strong>of</strong> both heads. The back <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> London head has a chipand <strong>the</strong> hair below it down to<strong>the</strong> nape <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> neck has beenre-cut and <strong>the</strong> back <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> neckshows re-polishing. The surface<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> hair on <strong>the</strong> rest <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>head shows some wear but <strong>the</strong>re-cut hair is crisp and new. TheVatican head exhibits similartraits and this damage is clearlywhere <strong>the</strong> integral plain supporthas been torn away.This corpus constitutes agroup <strong>of</strong> four heads that wouldbe consistent with <strong>the</strong>ir being aset <strong>of</strong> Tetrarchs. The attributionis fur<strong>the</strong>r streng<strong>the</strong>ned by <strong>the</strong> factthat this group <strong>of</strong> four heads isnot replicated elsewhere.It should be conceded that<strong>the</strong> two examples in <strong>the</strong> Louvrehave been recorded as <strong>the</strong> heads<strong>of</strong> Nerva (AD 96-98) and Trajan(AD 98-117). There is also aporphyry head <strong>of</strong> Trajan in <strong>the</strong>Glypto<strong>the</strong>que Ny Carlsberg,Copenhagen that is probablyco-eval with <strong>the</strong>m, althoughit might date to <strong>the</strong> early 2ndcentury AD.Recent research, however,suggests later dates (early4th century) for both <strong>the</strong>Copenhagen and Louvre headsas <strong>the</strong> earlier dates that havebeen attributed to <strong>the</strong>m arebefore Imperial porphyry wasmore generally available.The identification <strong>of</strong> this newhead at <strong>the</strong> Temple Gallery isan exciting event matched onlyby my finding, in 1993, <strong>of</strong>ano<strong>the</strong>r porphyry (<strong>the</strong> head <strong>of</strong>an emperor) that now residesin <strong>the</strong> Ashmolean Museum.Richard FalkinerMinerva November/December 2012temple gallery/claire nathan

ObituaryMr Mellaartcomfortable caves and a hunter-ga<strong>the</strong>rerexistence, to settle beside <strong>the</strong> spring atJericho and build a village based on agricultureand <strong>the</strong> domestication <strong>of</strong> animals –<strong>the</strong> first definite evidence <strong>of</strong> a link between<strong>the</strong> historical past and prehistory, some timearound 9500 BC. It was Jimmy’s scepticismthat had been <strong>the</strong> trigger for this momentousdiscovery.James Mellaart was born in 1925 inLondon, <strong>of</strong> a Dutch fa<strong>the</strong>r and an Irishmo<strong>the</strong>r. The family moved to Amsterdamin 1932, where his mo<strong>the</strong>r died and hisfa<strong>the</strong>r remarried, moving in 1940 moved toMaastricht. As a young man Jimmy workedat <strong>the</strong> National Museum <strong>of</strong> Antiquitiesin Leiden and studied Egyptology. Hereturned to England in 1947 to start a BA atUniversity College in London.Jimmy was conspicuously proud <strong>of</strong> hisScots ancestry, as a member <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Maclartyclan, a branch <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Macdonalds. Thisled to a fervent admiration <strong>of</strong> everythingScottish and a lifetime’s happy consumption<strong>of</strong> whisky, one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> many <strong>end</strong>earingaspects <strong>of</strong> his singular personality.In England he participated in one <strong>of</strong>Kathleen Kenyon’s postwar excavations atSutton Walls, an Iron Age site in south-westEngland. He graduated from <strong>the</strong> Institute<strong>of</strong> Archaeology in 1951, and was promptlygiven a two-year Fellowship at <strong>the</strong> BritishInstitute <strong>of</strong> Archaeology at Ankara (BIAA).There he devoted himself to exploring much<strong>of</strong> south-western Turkey, ei<strong>the</strong>r on foot orusing buses and trains for transport. It was<strong>the</strong>n that he revealed his remarkable stamina,tireless in his search for Chalcolithicand Bronze Age sites, <strong>of</strong> which he foundnumerous examples, including Beycesultan.He also learned fluent colloquial Turkishby staying overnight in villages anywherehe could find a bed, and being interrogatedby his inquisitive hosts about his motivesbefore being allowed to go to sleep.In 1952 he met Arlette Cenani, whom hemarried in 1954 and who bore him a son,Alan, in 1955. This was also <strong>the</strong> momentwhen <strong>the</strong> curious incident <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> DorakAffair happened. As he told <strong>the</strong> story, he wasaccosted while on a train journey to Izmirby an attractive young Greek woman, AnnaPapastrati, wearing an ancient gold bracelet.She took him into her confidence, told him<strong>the</strong> bracelet was part <strong>of</strong> a fabulous treasurehoard reputedly unear<strong>the</strong>d in <strong>the</strong> village <strong>of</strong>Dorak in Bursa province. She <strong>the</strong>n invitedhim back to her house to see <strong>the</strong> hoard andallowed him to draw it and to make notesabout it. In return he gave his word to keepMinerva November/December 2012it secret (which he did) until she told himhe could release <strong>the</strong> news. But she and <strong>the</strong>hoard both vanished into thin air. In 1958,he revealed his manuscript <strong>of</strong> over 60,000words and annotated drawings, which were<strong>the</strong>n published in <strong>the</strong> Illustrated LondonNews. This caused a sensation, and a publicoutcry in Turkey, which accused him <strong>of</strong>being a party to a criminal <strong>the</strong>ft. He denied<strong>the</strong> charge, and an indep<strong>end</strong>ent investigationby <strong>the</strong> BIAA exonerated him. The entiremanuscript has remained locked up by <strong>the</strong>BIAA till this very day. The few individualswho have seen it were astonished by <strong>the</strong>depth and detail <strong>of</strong> his record, which wentway beyond <strong>the</strong> imagination <strong>of</strong> any scholar.The truth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Dorak Affair has gone withJimmy to his grave.Arlette was his devoted partner at thistime and remained so for <strong>the</strong> rest <strong>of</strong> his life.I remember meeting both <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m when Iwas passed on by Kathleen to Seton Lloyd,Director <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> BIAA, to work as a draughtsmanbetween her seasons at Jericho, followedby a similar instruction to SinclairHood, Director <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> British School <strong>of</strong>Archaeology in A<strong>the</strong>ns, to keep me occupiedin A<strong>the</strong>ns and subsequently at Knossos.At Beycesultan, where Seton Lloyd andJimmy were working in tandem, I again waspaid a nominal sum, and accommodated in atent in <strong>the</strong> grounds <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> old AnatolianThe formidable archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon,or <strong>the</strong> Great Sitt, as she was known to <strong>the</strong> Arabworkmen who helped her excavate Jerichoduring <strong>the</strong> 1950s. (Photograph PA)house in <strong>the</strong> village which housed <strong>the</strong> archaeologists.One day, working on <strong>the</strong> site, I contractedsunstroke and was carried back to <strong>the</strong>village in a bullock cart. Arlette, who wasacting as interpreter, photographer and generalmanager, took a maternal interest in myrecovery. Later I stayed with <strong>the</strong> Mellaarts inArlette’s stepfa<strong>the</strong>r’s magnificent wooden yaliat Kanlica, on <strong>the</strong> Asian side <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Bosphorus.Sadly it was destroyed by a fire which alsoburnt many <strong>of</strong> Jimmy’s excavation notes.Seton Lloyd was a highly intelligent manwho early on recognised Jimmy’s extraordinarytalents, making him Assistant Director<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> BIAA from 1959 to 1961 and, as Ihave said, jointly excavating Beycesultanwith him. The only thing that disconcertedme was <strong>the</strong> fact that Jimmy proceeded toredraw all my pottery drawings. I realisedmany years later that this was not because<strong>the</strong>y were inaccurate, but simply to etch<strong>the</strong> images in his own prodigious memory.That this can happen I can testify from myown experience, for I can remember almostto this day thousands <strong>of</strong> drawings I madeat Jericho, which are indelibly etched intomy consciousness.I also remember being asked to make acopy <strong>of</strong> a wall painting at Beycesultan which<strong>the</strong>y were convinced depicted a man leapingover a bull’s horns. I simply could notsee this, and decided I would just copy <strong>the</strong>marks on <strong>the</strong> wall as best I could. They wereperfectly happy with <strong>the</strong> result.Jimmy’s real moment <strong>of</strong> glory came withhis discovery <strong>of</strong> Çatal Höyük in 1958 andits subsequent excavation. This conclusivelyproved that <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> mankindwas not limited to <strong>the</strong> Levant and <strong>the</strong>Fertile Crescent, but ext<strong>end</strong>ed westwardinto <strong>the</strong> Cenani Anatolian heartland. Thisrevolutionary discovery gave him fame andsecured his immortality. Its extensive settlementand extraordinary array <strong>of</strong> artefactscan be dated to circa 7500-5700 BC.Finally established as Lecturer inAnatolian Archaeology at <strong>the</strong> Institute <strong>of</strong>Archaeology in London, and disdainful<strong>of</strong> committees and any formal academicresponsibilities, James Mellaart inspiredgenerations <strong>of</strong> young scholars with his sheerenthusiasm and breadth <strong>of</strong> knowledge.His name has been linked to <strong>the</strong> concept<strong>of</strong> genius, which he may well have been.But for his many fri<strong>end</strong>s he will be rememberedmuch more as a lovable human being,with all those eccentricities that made himutterly unique.• James Mellaart(14 November 1925–29 July, 2012)9

Egyptian archaeology<strong>Amarna</strong><strong>city</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>light</strong>2 3 4It is 100 years this December since <strong>the</strong> <strong>world</strong>-famous painted head <strong>of</strong> Queen Nefertitiwas discovered at <strong>Amarna</strong>. Barry Kemp, who has been working on <strong>the</strong> site since 1977,shares his findings about <strong>the</strong> <strong>city</strong> <strong>of</strong> Akhenaten and its peopleHistory has its colourfulepisodes. For ancientEgypt none is more sothan <strong>the</strong> 17-year reign<strong>of</strong> Pharaoh Akhenaten. From aposition <strong>of</strong> unassailable authority,he set out to change <strong>the</strong> character<strong>of</strong> Egyptian kingship, creating animage <strong>of</strong> himself that is still uncomfortableto encounter and a simplifiedstate religion that asserted that<strong>the</strong> only worthwhile object <strong>of</strong> venerationwas <strong>the</strong> disc <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sun, <strong>the</strong>Aten. In pursuit <strong>of</strong> a mission to confoundand to cleanse, he chose anempty stretch <strong>of</strong> desert beside <strong>the</strong>1. Upper part <strong>of</strong> acolossal statue <strong>of</strong>Akhenaten. Karnak.Sandstone H. 6ft 8in.2. Statue thought tobe Akhenaten. Yellowstone. H. 25in.3. Relief showingAkhenaten andNefertiti making<strong>of</strong>ferings to <strong>the</strong> Aten.Limestone. H. 4ft 2in.4. Painted head <strong>of</strong>Nefertiti. Limestone/gypsum. H. 19.5in.Nile to be <strong>the</strong> new place where hisgod could be properly venerated,on ground that was uncontaminatedthrough prior associationwith gods or humans. He namedit Akhetaten, ‘The Horizon <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> Aten’. Lying roughly halfwaybetween modern Cairo and Luxor,it survives as a major archaeologicalsite now known as Tell el-<strong>Amarna</strong>or, more simply, <strong>Amarna</strong>. All thatis novel about <strong>the</strong> ideas and culture<strong>of</strong> Akhenaten’s reign, and controversialabout <strong>the</strong> personal histories<strong>of</strong> those involved, is summed up in<strong>the</strong> term to which <strong>the</strong> place namehas given rise, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Amarna</strong> Period.Akhenaten was not an asceticlooking for a life <strong>of</strong> isolated contemplationin <strong>the</strong> desert. Heremained ruler <strong>of</strong> Egypt and <strong>of</strong> asubstantial empire, and continuedto think in terms <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> grandarchitectural style that was so firmlyrooted in Egypt. The <strong>city</strong> he creatednow strikes an odd note, however,a compromise between grand visionand a limited acceptance <strong>of</strong> whatstate power could achieve in <strong>city</strong>creation. For himself and his god hebuilt palaces and temples at irregularintervals along a seven-kilometrePHOTOGRAPHS: 1 & 3 © Egyptian Museum, Cairo.2. Musée du Louvre, Paris. 4. © State Museum <strong>of</strong> Berlin.Minerva November/December 201211

5 8line that must have been close to <strong>the</strong>river. A cluster towards <strong>the</strong> middle,called in modern times <strong>the</strong> CentralCity, was clearly his centre <strong>of</strong> government.It included <strong>the</strong> ‘House <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> Aten’, <strong>the</strong> main temple to <strong>the</strong>sun god. A mud-brick wall encloseda flat expanse <strong>of</strong> desert measuring800 by 300 metres (around 40football pitches). Almost lost in thisspace were two stone-built templesthat were, appropriately enough fora cult <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> visible sun, series <strong>of</strong>open courts entered through traditional-lookingpylon gateways. Thecourts were filled with rectangularstone <strong>of</strong>fering tables that toge<strong>the</strong>rnumbered around 900. They wereinsufficient, however, to satisfy <strong>the</strong>king’s desire to display <strong>the</strong> scale <strong>of</strong>his piety, so a field <strong>of</strong> 920 extra oneswere built from mud bricks in a corner<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> great enclosure.The <strong>of</strong>fering tables were not symbols.Contemporary pictures <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>temple show <strong>the</strong>m piled with food<strong>of</strong>ferings and incense. The groundoutside housed a huge food depotwhere bread and meat, in particular,were prepared. Workingout how <strong>the</strong> system functionedis a research exercise in itself.The idea behind it, that largetemples were major providers<strong>of</strong> food and o<strong>the</strong>r commoditiesto <strong>the</strong> community, was not new.Akhenaten seems, in a spirit <strong>of</strong>literalism, to have wanted tomake <strong>the</strong> scale <strong>of</strong> his piety and<strong>the</strong> people’s dep<strong>end</strong>ence on <strong>the</strong>Aten fully visible. It was <strong>the</strong> ultimatestep in accounting transparency,in which everything was laidout in rows. For <strong>the</strong>re can be littledoubt that, after display beneath<strong>the</strong> sun, <strong>the</strong> destination <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> foodwas Akhenaten’s court and at least aportion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>city</strong>’s inhabitants.Akhenaten took his court andan important part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> administrationwith him to <strong>Amarna</strong>.Senior <strong>of</strong>ficials relied on junior <strong>of</strong>ficials,and all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m had extensivehouseholds. Among <strong>the</strong>m werepeople who manufactured thingsfor <strong>the</strong> court, including fine sculpture.In <strong>the</strong> <strong>end</strong>, probably as manyas 30,000 people moved <strong>the</strong>re.They did not find a ready-made<strong>city</strong> to inhabit, only a flattish, op<strong>end</strong>esert surface not marked out withroads. But very quickly, <strong>the</strong> arrivingcommunities organised <strong>the</strong>mselvesand built neighbourhoods that werelike villages, centred on <strong>the</strong> largerhouses <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>of</strong>ficials. If <strong>the</strong> resultresembles <strong>the</strong> plan <strong>of</strong> a squatter<strong>city</strong>, irregular but not haphazard, itmatched <strong>the</strong> expectations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> richand powerful <strong>of</strong>ficials who ran <strong>the</strong>country. The life <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>city</strong> spanned65. Painted terracottapot, New Kingdom,18th Dynasty, 1351-1334. © State Museum<strong>of</strong> Berlin. Photograph:Sandra Steiss.6. Head <strong>of</strong> an <strong>Amarna</strong>princess. Yellow-brownquartzite. H. 7.5in.© Egyptian Museum,Cairo.7. A section <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>‘Princesses Panel’wall painting foundinside <strong>the</strong> King’sHouse at <strong>Amarna</strong>.H. 38cm. W. 65cm.© AshmoleanMuseum, Oxford.7<strong>the</strong> period between Akhenaten’sfifth regnal year and his 17th andlast, and a few years beyond that, atotal <strong>of</strong> around 15 to 17 years.The successor kings, beginningwith Tutankhamun, rejectedAkhenaten’s ideas, withdrew <strong>the</strong>court to <strong>the</strong> old centres <strong>of</strong> powerand had <strong>the</strong> stone buildings demolishedso that <strong>the</strong>ir stones could bereused as building material. Themyriad houses were abandoned.<strong>Amarna</strong> was never lost, however.It remained visible – first asa ruin, <strong>the</strong>n as a spread <strong>of</strong> sandcoveredmounds – until archaeologistsbegan to excavate it at <strong>the</strong> <strong>end</strong><strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 19th century. Some <strong>of</strong> its decoratedrock tombs remained openand became home to a Christian12

Egyptian archaeology10monastic community in <strong>the</strong> earlycenturies AD. The scenes on <strong>the</strong>irwalls, and <strong>the</strong> content <strong>of</strong> hugeboundary tablets that Akhenatenhad had carved into <strong>the</strong> perimetercliffs, alerted European visitors to<strong>the</strong> character <strong>of</strong> Akhenaten’s reignfrom early in <strong>the</strong> 19th century.Excavation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>city</strong> began witha single six-month season, spanning1891 and 1892, carried out by <strong>the</strong>British archaeologist WM FlindersPetrie, assisted by Howard Carter,<strong>the</strong>n on his first assignment inEgypt. His one season was enoughto satisfy his curiosity, and he neversought to return. Some 15 yearslater, in 1907, <strong>the</strong> Egyptian governmentgranted a permit to workat <strong>Amarna</strong> to Ludwig Borchardt8. and 9. side and frontviews <strong>of</strong> a workingmodel for Nefertiti’shead. New Kingdom,18th Dynasty, 1351-1334. © State Museum<strong>of</strong> Berlin. Photograph:Sandra Steiss.10. Model <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mainpart <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ‘House <strong>of</strong>Aten’, <strong>the</strong> Long Templeat <strong>the</strong> front <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>enclosure at <strong>Amarna</strong>.© Model and photoby Eastwood Cook;concept by MallinsonArchitects.11. Map <strong>of</strong> <strong>Amarna</strong>© Barry Kemp.9<strong>of</strong> Berlin. Although working in<strong>the</strong> name <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft (German OrientalSociety), he was funded directlyby one wealthy Berlin textile merchantand philanthropist, JamesSimon. Borchardt set out on along-term, methodical excavation<strong>of</strong> much <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>city</strong>. Through thishe hoped to achieve two things.One was a detailed exploration <strong>of</strong>its architecture (reflecting his ownearly training as an architect); <strong>the</strong>o<strong>the</strong>r was <strong>the</strong> discovery <strong>of</strong> objectsand works <strong>of</strong> art that would grace<strong>the</strong> rapidly growing collections <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> Berlin Museum, by this time acultural showpiece for Germany’sambitions.In both he was quickly successful.In three seasons, between 1911and <strong>the</strong> spring <strong>of</strong> 1914, he and hissmall team excavated and mademeticulous plans <strong>of</strong> a huge part<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> main residential sector <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> <strong>city</strong>. The culmination came on6 December, 1912. In a small roomin <strong>the</strong> house <strong>of</strong> a sculptor, probablynamed Thutmose, lay an extraordinarycollection <strong>of</strong> sculptor’s modelsand related material, among <strong>the</strong>m abrightly painted limestone head andshoulders <strong>of</strong> a woman, instantlyidentifiable by her distinctive crownas Queen Nefertiti, Akhenaten’s wife.The head, with <strong>the</strong> rest <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>Thutmose material, passed through<strong>the</strong> Cairo Museum divisions systemand, following export to Berlin,became <strong>the</strong> property <strong>of</strong> JamesSimon. He subsequently presentedit all to <strong>the</strong> Berlin Museum. There itremains, <strong>the</strong> head <strong>of</strong> Nefertiti almostas much a symbol <strong>of</strong> Berlin as it is <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> Egyptian tourist industry.To mark <strong>the</strong> centenary <strong>of</strong> its discovery,<strong>the</strong>re is an exhibition in<strong>the</strong> impressive setting <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> NeuesMuseum, <strong>the</strong> part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> museumensemble in Berlin which is hometo <strong>the</strong> Egyptian collection and isitself only recently restored from <strong>the</strong>ruin that was left at <strong>the</strong> <strong>end</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>Second World War.The outcome <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> First WorldWar, and <strong>the</strong> increasing feeling inEgypt that <strong>the</strong> head <strong>of</strong> Nefertitishould be returned, meant <strong>the</strong><strong>end</strong> <strong>of</strong> Borchardt’s expedition. Inits place, from 1921 to 1936, <strong>the</strong>London-based Egypt ExplorationSociety fielded an annual expeditionkeycultivated landexcavated <strong>city</strong>unexcavated <strong>city</strong>11NKmodern villageboundary stelaquarriesNorth Cityrock-cut tombNorth Riverside PalaceNorth PalaceDesert AltarsVNorth TombsNorth SuburbGreat Aten TempleGreat PalaceSmall Aten TempleCentral CityUriver Nile'River Temple'Main City SouthMain City NorthWorkmen's Villagehouse <strong>of</strong> Thutmoseto <strong>the</strong> Royal TombStone VillageSouth SuburbKom el-NanaEl-MangaraMaru-AtenSouth Tombs

Egyptian archaeologythat continued where Borchardt left<strong>of</strong>f, gradually moving from ancienthouses to Akhenaten’s temples andpalaces. By 1936, with <strong>the</strong> completion<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> excavation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> CentralCity, <strong>the</strong> site’s attraction had sufficientlydiminished for <strong>the</strong> work tobe abandoned.The archaeology <strong>of</strong> that era hada style and set <strong>of</strong> expectations <strong>of</strong>its own. It took advantage <strong>of</strong> cheaplocal labour to dig on a large scale.It sought ‘discoveries’ – and itdep<strong>end</strong>ed for its funding on beingable to provide a stream <strong>of</strong> suitableobjects to foreign museums and<strong>the</strong>ir patrons, taking advantage <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> system by which <strong>the</strong> Egyptiangovernment allowed foreign expeditionsto export a share <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> finds.I started working at <strong>Amarna</strong>in 1977, with a set <strong>of</strong> ideas inkeeping with <strong>the</strong> new times. Thesocial and economic processes bywhich ancient societies workedand how <strong>the</strong>y manifested <strong>the</strong>mselvesin <strong>the</strong> details <strong>of</strong> buildings andobjects were hot topics. Settlementarchaeology was becoming a subjectin its own right. It seemedworthwhile to document what wasin <strong>the</strong> ground in immensely greaterdetail than before and to bring in awider range <strong>of</strong> experts in order toextract more and different kinds <strong>of</strong>information. We were starting touse computers and it was exciting.I saw <strong>Amarna</strong>’s unique combination<strong>of</strong> <strong>city</strong>-size scale and narrow interval<strong>of</strong> time as perfect for developingan investigation <strong>of</strong> this kind.What made <strong>Amarna</strong> as a <strong>city</strong> tick?12. and 13. side andfront views <strong>of</strong> ahead <strong>of</strong> Nefertiti.Granodiorite. NewKingdom, 18thDynasty, 1351-1334.© State Museum <strong>of</strong>Berlin. Photograph:Sandra Stelb.14. Relief showingAkhenaten, his wifeNefertiti and <strong>the</strong>irthree daughtersba<strong>the</strong>d in <strong>the</strong> divine<strong>light</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Aten.New Kingdom, 18thDynasty, 1351-1334.Limestone. H. 33cm.W. 39cm. © StateMuseum <strong>of</strong> Berlin.Photograph:Margarete Busing.12 13Akhenaten and Nefertiti were barelyin my mind. Once again <strong>the</strong> workwas under <strong>the</strong> auspices <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> EgyptExploration Society, largely usinggovernment funds channelled to<strong>the</strong>m by <strong>the</strong> British Academy.This kind <strong>of</strong> archaeology does notprovide quick and easy answers. Thequantity <strong>of</strong> humdrum finds – tens <strong>of</strong>thousands <strong>of</strong> potsherds, shelf aftershelf <strong>of</strong> boxes <strong>of</strong> charcoal fragmentsthat are gold to archaeo-botanists– is almost overwhelming. In <strong>the</strong>35 years that have followed, sometimesbuffeted by difficult conditionsin Egypt, we (myself and <strong>the</strong><strong>Amarna</strong> team) have carried outexcavations <strong>of</strong> limited scale at aseries <strong>of</strong> places that cover <strong>the</strong> spectrumfrom small to large houses,royal buildings and now an extensivecemetery where <strong>the</strong> ordinaryinhabitants were buried and whosebones represent an entirely new kind<strong>of</strong> evidence for <strong>the</strong> life <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> people.Sometimes, as with <strong>the</strong> bones, <strong>the</strong>evidence tells a tale directly. More<strong>of</strong>ten it fuels debate. How far wasAkhenaten’s society one directedfrom above and what scope was leftfor individual responsibility? Was ittightly or loosely organised? As <strong>the</strong>discussion and thinking about <strong>the</strong>site has continued, Akhenaten hasmoved to a more prominent place.Did he care about his people or not?And what about his religious drive?Did it generate <strong>the</strong> kind <strong>of</strong> intolerancethat we might expect? Here <strong>the</strong>answer seems to be no, for <strong>Amarna</strong>emerges as a particularly rich sourcefor <strong>the</strong> archaeology <strong>of</strong> domestic religionthat, in its visible manifestations,paid little heed to <strong>the</strong> Aten.As with <strong>the</strong> humanities in general,<strong>the</strong>re are no final answers. Each newgeneration changes <strong>the</strong> questionsand terms <strong>of</strong> debate. Those whocome in <strong>the</strong> future will find, in ourpublications, archives and materialstored on site, <strong>the</strong> raw material fortaking research forward as to howEgyptian society evolved. n14• The <strong>Amarna</strong> Trust (www.amarnatrust.com) is a registeredcharity that supports a broadprogramme <strong>of</strong> fieldwork(www.amarnaproject.com) runin agreement with <strong>the</strong> EgyptianMinistry <strong>of</strong> State for Antiquities.• The City <strong>of</strong> Akhenaten andNefertiti: <strong>Amarna</strong> and Its Peopleby Barry Kemp (£29.95) ispart <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> series New Aspects<strong>of</strong> Antiquity, general editorColin Renfrew, published byThames & Hudson.• In <strong>the</strong> Light <strong>of</strong> <strong>Amarna</strong>, anexhibition celebrating <strong>the</strong>discovery <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> bust <strong>of</strong> Nefertiti100 years ago and including600 objects from, or related to,<strong>Amarna</strong>, opens at <strong>the</strong> NeuesMuseum in Berlin (www.neuesmuseum.de) on 6 Decemberand runs until 13 April 2013.Minerva November/December 2012

InterviewRoaming withRomerEgyptologist, historian and archaeologist John Romer tells Diana Bentley how hemoved from studying stained glass to digging in <strong>the</strong> Valley <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> KingsWhen John Romer entered <strong>the</strong>Royal College <strong>of</strong> Art in 1966to study <strong>the</strong> art <strong>of</strong> stainedglass, little did he thinkthat it would lead him all <strong>the</strong> way backto ancient Egypt. But when he saw a noteposted on <strong>the</strong> Stained Glass Department’snoticeboard asking for artists to join<strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Chicago’s EpigraphicSurvey in Luxor, he leapt at <strong>the</strong> chance.‘I’d been interested in ancient Egypt since Iwas a child. I gave a lecture on <strong>the</strong> Pyramidsat school when I was 12, and <strong>the</strong> first bookI purchased was Wallis Budge’s Guide to<strong>the</strong> British Museum’s Egyptian Collections,price 1/3d,’ he recalls. Romer and his newwife Beth, a fellow art student who laterbecame an archaeologist, set <strong>of</strong>f for Egypttoge<strong>the</strong>r, and an <strong>end</strong>uring and mutual passionfor <strong>the</strong> country and its long, enthrallinghistory was born.The renowned archaeologist, author andtelevision presenter remembers how hefelt when he first arrived <strong>the</strong>re: ‘My initialimpressions, during a night drive from <strong>the</strong>airport, were unforgettable. Hot, marvellouslyperfumed air, dark streets, with littlefires lit on <strong>the</strong> pavements and people in galabeyasflitting in and out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> shadows.’In Luxor <strong>the</strong> Romers set to work as epigraphicartists, although at first <strong>the</strong>y found<strong>the</strong> ancient temples disappointing.‘I couldn’t see what all <strong>the</strong> fuss was about,’he says. ‘It took years <strong>of</strong> working in <strong>the</strong>mto appreciate <strong>the</strong>ir beauty – you have tobe able to look through <strong>the</strong> dust and ruin.’The sites were also disconcertingly disordered:‘Thebes looked like an explosion hadoccurred, with mummies lying all around.’Never<strong>the</strong>less, after working six days a weekin <strong>the</strong> temples, <strong>the</strong> Romers spent <strong>the</strong> seventhlooking at o<strong>the</strong>r monuments and, like o<strong>the</strong>rartists before <strong>the</strong>m, including <strong>the</strong> leg<strong>end</strong>aryHoward Carter, <strong>the</strong>y became increasinglydrawn to archaeology. Fortunately, <strong>the</strong> environmentwas perfect for those keen to learn.‘Chicago House, <strong>the</strong> very grand headquarters<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Chicago’sOriental Institute Epigraphic Survey in16Luxor, was a centre <strong>of</strong> archaeology and hada superb library. I spent all my waking hoursreading and asking an extraordinary range<strong>of</strong> archaeologists what <strong>the</strong>y were doingand why,’ Romer explains. ‘So Beth and Ihad seen dozens <strong>of</strong> digs before we wereemployed to work on one.’The Valley <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Kings especiallyattracted <strong>the</strong> couple’s interest. After manyyears <strong>of</strong> working privately at <strong>the</strong> site, <strong>the</strong>yorganised and ran an expedition to makegeological, epigraphic and conservationalstudies between 1977 and 1979.‘It was <strong>the</strong> first ever at that site, which<strong>the</strong>n was little known or cared about byEgyptolgists. <strong>Not</strong> much had been done sinceHoward Carter’s day and it was sufferinggreatly because <strong>of</strong> a rise in tourism,’ Romerexplains. ‘We needed a base in <strong>the</strong> valley tostore our equipment, and Ramesses XI wasa huge open and largely empty tomb whichseemed perfect for that task. Carter, in fact,had used it as a store and a dining roomwhen he excavated Tutankhamun.’Before <strong>the</strong>y could use <strong>the</strong> tomb, however,<strong>the</strong> debris within it had to be cleared away.‘That’s when we realised that most <strong>of</strong> thisdebris was very ancient, that <strong>the</strong> tomb wasonly half finished and had been used at <strong>the</strong><strong>end</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> New Kingdom as a storeroomfor <strong>the</strong> royal mummies. So we found lots<strong>of</strong> extraordinary stuff. It was <strong>the</strong> first tombto be excavated in <strong>the</strong> valley since Carter’swork on Tutankhamun. It was tense workand very exciting but, none<strong>the</strong>less, a sideshow to <strong>the</strong> expedition’s main task <strong>of</strong>conservation, <strong>of</strong> which I am very proud.Virtually all <strong>the</strong> later work in <strong>the</strong> Valley <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> Kings stems from some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> brilliantwork <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> specialists who worked on <strong>the</strong>expedition and later wrote articles in ourreports,’ he says.The team also found that despite its aridappearance, <strong>the</strong> valley was subject to flooding,so work was undertaken to lessen <strong>the</strong>damaging effect <strong>of</strong> water on <strong>the</strong> tombs.Much work was also done to clean up <strong>the</strong>area and organise its tourist facilities.‘The ticket <strong>of</strong>fice lay in <strong>the</strong> middle <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>valley and buses and taxis were driving rightinto it,’ Romer recalls.In 1979 he and his wife, toge<strong>the</strong>r withsome American colleagues, also founded<strong>the</strong> Theban Foundation, based in Berkeley,Minerva November/December 2012

California. A body dedicated to <strong>the</strong> conservationand documentation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RoyalTombs <strong>of</strong> Thebes, many <strong>of</strong> its ideas havebeen taken up. This resulted in <strong>the</strong> ThebanMapping Project. Now run by <strong>the</strong> AmericanUniversity in Cairo, <strong>the</strong> project provides acomprehensive database <strong>of</strong> Thebes and hasan extensive website.Today Romer is still publishing reportsstemming from this early expedition. Vividmemories <strong>of</strong> those early days also remain:‘The tombs were entirely beautiful, quietand dark, with <strong>the</strong> scent <strong>of</strong> cedarwood in<strong>the</strong>m,’ he says. Since <strong>the</strong>n, Egyptian archaeologyhas evolved considerably.‘It has entirely changed from <strong>the</strong> dayswhen I first went <strong>the</strong>re. Then it was largelysand-shovelling to recover more inscriptions.Now <strong>the</strong>re are pr<strong>of</strong>essionally traineddirt archaeologists digging difficult siteswith great skill to discover <strong>the</strong> ways <strong>of</strong> life<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ancient people. They are slowly writinga new history for ancient Egypt.’None<strong>the</strong>less, funding is now more difficultto obtain and <strong>the</strong> situation in Egypthas greatly changed. ‘New excavationhas been stopped in Upper Egypt – which isactually no bad thing, as those sites requiremore conservation than exploration,’he comments.O<strong>the</strong>r developments also cause him concern.‘Parts <strong>of</strong> Egyptology have becomefilled with unsuitable jargon from o<strong>the</strong>racademic disciplines. Introducing mockscientificjargon into what is fundamentallya humanistic discipline has led to parts <strong>of</strong>a lovely old subject becoming nastily politicised,ancient history employed to providea pedigree for <strong>the</strong> modern Western <strong>world</strong>,’he says. One chilling example in his bookis where great tombs were referred to asexamples <strong>of</strong> ‘<strong>the</strong> conspicuous consumption<strong>of</strong> prestige commodities by an elite’.His favourite figure from <strong>the</strong> early days <strong>of</strong>archaeology, he says, is Flinders Petrie.‘He was a crusty individualist who virtuallyinvented Egyptian archaeology. He wasusually irascible, <strong>of</strong>ten wrong, but upfrontwith his personal opinions, an incrediblyhard worker who had something interestingto say about everything he came across– and certainly he was a lover <strong>of</strong> old Egypt.’John Romer has proved to be that too andhas been rewarded, he says, by embracing<strong>the</strong> country as it is today.‘Village life in modern Egypt has had ahuge effect upon me – not because I thinkpeople <strong>the</strong>re today live like ancient Egyptians,but simply because <strong>the</strong>y have shown mebeautiful and viable alternatives to myWestern way <strong>of</strong> life. The Egyptian landscape,too, has had a pr<strong>of</strong>ound effect upon me. I’mamazed at how many European and USscholars never bo<strong>the</strong>r to visit <strong>the</strong> countrieswhich <strong>the</strong>y sp<strong>end</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir lives studying.’Working on his books and televisiondocumentaries allows him to immersehimself in a range <strong>of</strong> diverse subjects. TheMinerva November/December 2012documentaries in particular, which includeAncient Lives, Testament, The Valley <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>Kings and Byzantium: The Lost Empire,have been demanding and intellectuallybracing.‘I want to know more about things thanI do already, and <strong>the</strong>re’s nothing like writinga television series to discover <strong>the</strong> gaps inyour knowledge <strong>of</strong> a subject,’ he insists. ‘It’sa trem<strong>end</strong>ous amount <strong>of</strong> work. But workingon Bible history, Hellenism and Byzantiumhave been very useful to my work withancient Egypt too. Like modern Egypt, <strong>the</strong>yhave shown me o<strong>the</strong>r ways <strong>of</strong> being besideslife in <strong>the</strong> modern West and o<strong>the</strong>r ways<strong>of</strong> approaching ancient history as well –Egyptology is very compartmentalised.’There are common elements in <strong>the</strong> subjectshe has chosen, as he explains: ‘They’reall based in <strong>the</strong> Eastern Mediterranean, <strong>the</strong>yall start from <strong>the</strong> assumption that <strong>the</strong> pastwas very, very different from today, and<strong>the</strong>y all deal in arts and crafts that have hadextraordinary longevity. To that extent, Ithink that <strong>the</strong>y’re all linked to my havingmade stained glass windows, too.’He was prompted to write his latest book,A History <strong>of</strong> Ancient Egypt: From <strong>the</strong> FirstFamers to <strong>the</strong> Great Pyramid, by a belief thatpeople like himself, who have been workingon ancient Egyptian material for some time,should set down <strong>the</strong>ir vision <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> place. Amajor deficiency <strong>of</strong> Egyptology is, he says,that <strong>the</strong>re are no up-to-date accounts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>entire civilisation written by a single voice.‘The problem with history by committee isthat <strong>the</strong>re is no coherent vision <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> subject.I think it’s a good discipline to work out ideasright down to <strong>the</strong> point where <strong>the</strong>y becomenarratives that anyone can understand. It’smuch harder than writing academic articles,which only have to make sense to a few.’His book is <strong>the</strong> first consistent account<strong>of</strong> Egypt’s early history, as opposed to adescription <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> surviving remains strungtoge<strong>the</strong>r on a single time-line. It starts withan absorbing account <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> exploration <strong>of</strong>some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> earliest excavated settlementsalong <strong>the</strong> Nile. Where did <strong>the</strong>se people comefrom? He says he tries not to speculate:‘People “come out <strong>of</strong> nowhere” because<strong>the</strong>y come and go so easily from <strong>the</strong> archaeologicalrecord. As far as <strong>the</strong> first inhabitants<strong>of</strong> Egypt are concerned, I suppose it dep<strong>end</strong>swhe<strong>the</strong>r or not you follow <strong>the</strong> popular “out<strong>of</strong> Africa” scenario for modern humans. Ifyou do, perhaps <strong>the</strong>re’s a case for sayingthat some people travelling north out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>Rift Valley decided to go no fur<strong>the</strong>r. As to<strong>the</strong> first farmers, <strong>the</strong>y could ei<strong>the</strong>r have been<strong>the</strong> desc<strong>end</strong>ants <strong>of</strong> those same peoples, orsettlers from <strong>the</strong> Levant and Anatolia whoalready had developed <strong>the</strong> technologies <strong>of</strong>farming. That <strong>the</strong>y skilfully and quicklyadapted <strong>the</strong> rhythms <strong>of</strong> rain-irrigated economiesto that <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Nile Valley flood plainshows great practical knowledge <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> localenvironment. Perhaps, as with almost everythingelse that happened in <strong>the</strong> distant past,we’ll never know.’Romer does, however, disagree with some<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> popular ideas about <strong>the</strong> Egyptian pharaohs:‘They weren’t despots and <strong>the</strong>y didn’tenslave people,’ he maintains. ‘As to slavery,it seems to me that in its present usage, <strong>the</strong>concept revolves around money and propertyvalues, nei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>of</strong> which were aroundin ancient Egypt – nor incidentally, was <strong>the</strong>modern concept <strong>of</strong> freedom.’One <strong>of</strong> his favourite projects was AncientLives, a series he made in <strong>the</strong> 1980s about avillage <strong>of</strong> artists in ancient Egypt.‘It was a de<strong>light</strong> to make and people stillremember those films – parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir scenarioare now on <strong>the</strong> Luxor tourist circuit,although at that time no one could haveforeseen <strong>the</strong> tourist tidal wave to come.’He is now engrossed in writing a second,self-contained volume on <strong>the</strong> later history <strong>of</strong>ancient Egypt (due for publication in 2014)at his base in Tuscany, where he and Bethhave lived for many years. ‘We’ve grown tolove <strong>the</strong> country and its culture and we’vebeen here so long now that when I land atRome or Pisa I feel I’m coming home.’Does he feel that <strong>the</strong>re is a growing interestin history and archaeology?‘Yes, I suppose <strong>the</strong>re is, although sometimesI think that it’s a funny sort <strong>of</strong> interest.Classics, for example, always makes methink <strong>of</strong> Arnold <strong>of</strong> Rugby and Billy Bunter.Let’s hope it’s not all nostalgia for an agethat never was, but a fascination for a pastthat was remarkable, fresh and interestingwith something new to teach us.’His work has undoubtedly fired <strong>the</strong> imagination<strong>of</strong> readers and television audiences.‘Every so <strong>of</strong>ten someone s<strong>end</strong>s me a <strong>the</strong>sisor a book <strong>the</strong>y’ve written with a note tellingme that something I’ve done has encouraged<strong>the</strong>m to take up <strong>the</strong>ir present pr<strong>of</strong>ession,’John Romer tells me with evident and welldeservedsatisfaction. nA History <strong>of</strong> Ancient Egypt: From <strong>the</strong>First Farmers to <strong>the</strong> Great Pyramid byJohn Romer is published in hardbackby Allen Lane at £25.17

CleopatraIs this <strong>the</strong>wickedestwomanDavid Stuttardgoes beyondscathing Romanpropagandaand Hollywood’sglamorous imagesin search <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>real Cleopatrain history?Mention <strong>the</strong> nameCleopatra to anyone,and <strong>the</strong>y willno doubt immediatelyconjure up <strong>the</strong>ir own image<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Egyptian queen. For many, itis an image which has been shapedby film and television: ElizabethTaylor in <strong>the</strong> 1963 epic Cleopatra;Lyndsey Marshal in HBO’s blockbusterseries Rome; even AmandaBarrie in Carry on Cleo. O<strong>the</strong>rswill think <strong>of</strong> stage versions <strong>of</strong> herlife: Shakespeare’s Antony andCleopatra; Shaw’s Caesar andCleopatra. Yet o<strong>the</strong>rs may see in<strong>the</strong>ir mind’s eye <strong>the</strong> seductive paintings<strong>of</strong> 19th-century artists, suchas Alma-Tadema or Jean-AndréRixens, who de<strong>light</strong>ed in <strong>the</strong> opportunityto paint <strong>the</strong> suicidal queenbare-breasted, her robe falling tantalisinglyfrom her shoulders, or,better still, fully naked.Throughout history, so manypeople have interpreted Cleopatrain so many different ways that it isalmost impossible to discover <strong>the</strong>real person behind <strong>the</strong> myth. Yet<strong>the</strong> reality (or what we know <strong>of</strong> it)is even more intriguing than <strong>the</strong> fiction.Born in 69 BC into <strong>the</strong> murderous,incestuous and faction-rivenfamily <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Ptolemies (desc<strong>end</strong>ents<strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong> Alexander <strong>the</strong> Great’s181Macedonian generals) who hadalready ruled Egypt for well over200 years, Cleopatra possessedan undoubted charisma. Plutarch,whose biography <strong>of</strong> Mark Antonyshe effectively hijacks, writes <strong>of</strong> her:‘Her own beauty, so we are told,was not <strong>of</strong> that incomparable kindwhich instantly captivates <strong>the</strong>beholder. But <strong>the</strong> charm <strong>of</strong> her presencewas irresistible and <strong>the</strong>re wasan attraction in her person and hertalk, toge<strong>the</strong>r with a peculiar force<strong>of</strong> character which pervaded herevery word and action, and laid allwho associated with her under itsspell. It was a de<strong>light</strong> merely to hear<strong>the</strong> sound <strong>of</strong> her voice, with which,like an instrument <strong>of</strong> many strings,she could pass effortlessly from onelanguage to ano<strong>the</strong>r.’What she lacked in beauty (and,judging from depictions on her owncoinage, even Plutarch’s descriptionmay be best described as gallant),Cleopatra more than made upfor in intellect. She had grown upin Alexandria, home to <strong>the</strong> famousLibrary and Museum and at thattime a leading centre <strong>of</strong> learning,and she had made maximum use <strong>of</strong>its facilities. Plutarch goes on: ‘Inher interviews with barbarians sheseldom required an interpreter, butconversed with <strong>the</strong>m quite unaided,21. Silver denariusshowing Antony,obverse (left) ,andCleopatra, reverse,struck at a travellingmint. 32 BC. D. 1.85cm.British Museum.whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>y were Ethiopians,Troglodytes, Hebrews, Arabians,Syrians, Medes or Parthians. Infact, she is said to have becomefamiliar with <strong>the</strong> speech <strong>of</strong> manyo<strong>the</strong>r peoples besides, although <strong>the</strong>rulers <strong>of</strong> Egypt before her had nevereven troubled to learn <strong>the</strong> Egyptianlanguage, and some had never givenup <strong>the</strong>ir native Macedonian dialect.’Despite her undoubted assets,when she became queen in 51 BC,Cleopatra was faced with almostinsuperable difficulties. Rome,whose power and population hadmushroomed in <strong>the</strong> previous threegenerations, had already identifiedEgypt’s fertile cornfields as aMinerva November/December 2012

potential solution to its ownfood shortages, while inEgypt, domesticpolitical rivalriesmeant that shewas soon at warwith Ptolemy XIIIher younger bro<strong>the</strong>r(and husband, at leastin name). And, as ifthat were not enough,Cleopatra was a womanin what (internationally)was quite definitely aman’s <strong>world</strong>. For her evento survive required not onlytena<strong>city</strong>, ruthlessness anddiplomacy, but also luck – and32. The Death <strong>of</strong>Cleopatra by Jean-André Rixens, 1874.H. 200cm. W. 290cm.Musée des Augustins,Toulouse.3. Fragment <strong>of</strong> amarble relief showingan erotic scene ina boat, possibly asavage caricature<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> love-affairbetween Antony andCleopatra. Probablyfrom Italy. 1st centuryBC-1st century AD.H. 36cm. W. 40cm.British Museum.luck favoured her for 20 years.By chance, just when it seemed asthough her army was about to bedefeated by Ptolemy XIII, JuliusCaesar arrived in Alexandria andthrew his weight behind <strong>the</strong> queen.An inveterate womaniser as well asa consummate general, <strong>the</strong> victoriousCaesar subsequently left Egyptonly weeks before she gave birth to<strong>the</strong>ir son, Caesarion. For Cleopatra,it was a perfect outcome.With Caesar’s continuing support,her position, both domesticallyand internationally, was secured,and understanding perfectly <strong>the</strong>power <strong>the</strong>ir child bestowed onher, she twice made <strong>the</strong> long sea19