Case 7-2011: A 52-Year-Old Man with Upper Respiratory Symptoms ...

Case 7-2011: A 52-Year-Old Man with Upper Respiratory Symptoms ...

Case 7-2011: A 52-Year-Old Man with Upper Respiratory Symptoms ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

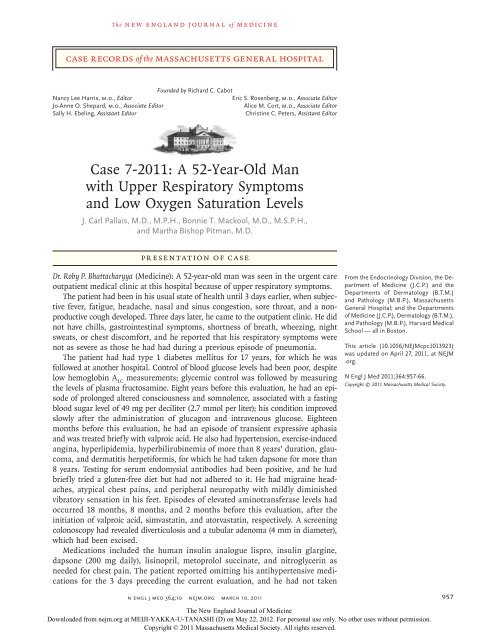

T h e n e w e ngl a nd j o u r na l o f m e dic i n ecase records of the massachusetts general hospitalFounded by Richard C. CabotNancy Lee Harris, m.d., EditorEric S. Rosenberg, m.d., Associate EditorJo-Anne O. Shepard, m.d., Associate EditorAlice M. Cort, m.d., Associate EditorSally H. Ebeling, Assistant EditorChristine C. Peters, Assistant Editor<strong>Case</strong> 7-<strong>2011</strong>: A <strong>52</strong>-<strong>Year</strong>-<strong>Old</strong> <strong>Man</strong><strong>with</strong> <strong>Upper</strong> <strong>Respiratory</strong> <strong>Symptoms</strong>and Low Oxygen Saturation LevelsJ. Carl Pallais, M.D., M.P.H., Bonnie T. Mackool, M.D., M.S.P.H.,and Martha Bishop Pitman, M.D.Pr esen tation of C a seDr. Roby P. Bhattacharyya (Medicine): A <strong>52</strong>-year-old man was seen in the urgent careoutpatient medical clinic at this hospital because of upper respiratory symptoms.The patient had been in his usual state of health until 3 days earlier, when subjectivefever, fatigue, headache, nasal and sinus congestion, sore throat, and a nonproductivecough developed. Three days later, he came to the outpatient clinic. He didnot have chills, gastrointestinal symptoms, shortness of breath, wheezing, nightsweats, or chest discomfort, and he reported that his respiratory symptoms werenot as severe as those he had had during a previous episode of pneumonia.The patient had had type 1 diabetes mellitus for 17 years, for which he wasfollowed at another hospital. Control of blood glucose levels had been poor, despitelow hemoglobin A 1c measurements; glycemic control was followed by measuringthe levels of plasma fructosamine. Eight years before this evaluation, he had an episodeof prolonged altered consciousness and somnolence, associated <strong>with</strong> a fastingblood sugar level of 49 mg per deciliter (2.7 mmol per liter); his condition improvedslowly after the administration of glucagon and intravenous glucose. Eighteenmonths before this evaluation, he had an episode of transient expressive aphasiaand was treated briefly <strong>with</strong> valproic acid. He also had hypertension, exercise-inducedangina, hyperlipidemia, hyperbilirubinemia of more than 8 years’ duration, glaucoma,and dermatitis herpetiformis, for which he had taken dapsone for more than8 years. Testing for serum endomysial antibodies had been positive, and he hadbriefly tried a gluten-free diet but had not adhered to it. He had migraine headaches,atypical chest pains, and peripheral neuropathy <strong>with</strong> mildly diminishedvibratory sensation in his feet. Episodes of elevated aminotransferase levels hadoccurred 18 months, 8 months, and 2 months before this evaluation, after theinitiation of valproic acid, simvastatin, and atorvastatin, respectively. A screeningcolonoscopy had revealed diverticulosis and a tubular adenoma (4 mm in diameter),which had been excised.Medications included the human insulin analogue lispro, insulin glargine,dapsone (200 mg daily), lisinopril, metoprolol succinate, and nitroglycerin asneeded for chest pain. The patient reported omitting his antihypertensive medicationsfor the 3 days preceding the current evaluation, and he had not takenFrom the Endocrinology Division, the Departmentof Medicine (J.C.P.) and theDepartments of Dermatology (B.T.M.)and Pathology (M.B.P.), MassachusettsGeneral Hospital; and the Departmentsof Medicine (J.C.P.), Dermatology (B.T.M.),and Pathology (M.B.P.), Harvard MedicalSchool — all in Boston.This article (10.1056/NEJMcpc1013923)was updated on April 27, <strong>2011</strong>, at NEJM.org.N Engl J Med <strong>2011</strong>;364:957-66.Copyright © <strong>2011</strong> Massachusetts Medical Society.n engl j med 364;10 nejm.org march 10, <strong>2011</strong> 957The New England Journal of MedicineDownloaded from nejm.org at MEIJI-YAKKA-U-TANASHI (D) on May 22, 2012. For personal use only. No other uses <strong>with</strong>out permission.Copyright © <strong>2011</strong> Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

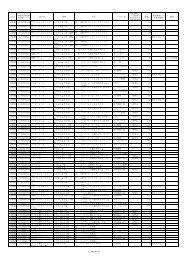

T h e n e w e ngl a nd j o u r na l o f m e dic i n eatorvastatin for the previous 2 weeks, nor hadhe taken aspirin, ranitidine, or latanoprost ophthalmicdrops recently. He had received influenzaand pneumococcal vaccines in the past. Helived <strong>with</strong> his wife and worked in an office. Hiswife had been ill <strong>with</strong> respiratory and gastrointestinalsymptoms approximately 1 week beforethis evaluation. He drank alcohol moderately,had never smoked, and did not use illicit drugs.His father had died at <strong>52</strong> years of age from metastaticcolon cancer, both parents had had hypertension,his mother and sister had migraines, andan uncle had type 1 diabetes; there was no otherfamily history of autoimmune diseases.On examination, the patient appeared to becomfortable, <strong>with</strong>out respiratory distress. The skinwas pale. The blood pressure was 164/75 mm Hg,the pulse 81 beats per minute, the temperature37.7°C, the respiratory rate 12 to 16 breaths perminute, and the oxygen saturation (tested onmultiple digits of both hands and feet) 85 to90% while the patient was breathing ambient air.The body-mass index (BMI) (the weight in kilogramsdivided by the square of the height inmeters) was 32. Capillary refill occurred in 2 to3 seconds, and there was no clubbing, cyanosis,or ulcerations. The remainder of the examinationwas normal. On further review of the patient’srecord, the oxygen saturation had been 89% and86%, 17 months and 15 months before thisevaluation, respectively, as measured by pulseoximetry (most likely <strong>with</strong> different oximeters)while he was breathing ambient air.The white-cell count, differential count, plateletcount, and levels of total protein, albumin,globulin, alkaline phosphatase, and aspartateand alanine aminotransferases were normal;other laboratory-test results are shown in Table 1.A chest radiograph was normal. Fluticasone nasalspray was prescribed, and the patient was discharged<strong>with</strong> instructions to follow up <strong>with</strong> hisinternist for additional laboratory studies.Two months later, he returned to the outpatientclinic for routine follow-up; he had resumedtaking atorvastatin. On examination, he appearedto be comfortable. The respiratory rate was 12 to16 breaths per minute, and the oxygen saturation88% while he was breathing ambient air.The BMI was 32.8, and the blood pressure, pulse,and temperature were normal. The remainder ofthe examination was normal. The white-cellcount, differential count, and platelet count werenormal. The levels of electrolytes, protein, albumin,globulin, alkaline phosphatase, aspartateTable 1. Laboratory Data.*VariableReference Range,Adults† On Evaluation 2 Mo LaterHematocrit (%) 41.0–53.0 (men) 41.7 37.8Hemoglobin (g/dl) 13.5–17.5 (men) 13.8 12.3Mean corpuscular volume (μm 3 ) 80–100 92 92Erythrocyte count (×10 –6 /liter) 4.50–5.90 (men) 4.54 4.13Red-cell distribution width (%) 11.5–14.5 14.2 15.9Reticulocytes (%) 0.5–2.5 6.6Hemoglobin A 1c (%) 3.80–6.40 4.70Calculated mean blood glucose (mg/dl) 88Glucose (mg/dl) 70–110 227Fructosamine (μmol/liter) 200–285 403Bilirubin (mg/dl)Total 0.0–1.0 2.4 2.6Direct 0.0–0.4 0.7 0.8Lactate dehydrogenase (U/liter) 110–210 405* To convert the values for glucose to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.05551. To convert the values for bilirubin to micromolesper liter, multiply by 17.1.† Reference values are affected by many variables, including the patient population and the laboratory methods used. Theranges used at Massachusetts General Hospital are for adults who are not pregnant and do not have medical conditionsthat could affect the results. They may therefore not be appropriate for all patients.958n engl j med 364;10 nejm.org march 10, <strong>2011</strong>The New England Journal of MedicineDownloaded from nejm.org at MEIJI-YAKKA-U-TANASHI (D) on May 22, 2012. For personal use only. No other uses <strong>with</strong>out permission.Copyright © <strong>2011</strong> Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

case records of the massachusetts gener al hospitaland alanine aminotransferases, calcium, iron,iron-binding capacity, and ferritin were normal,as were hemoglobin electrophoresis, the aniongap, and tests of renal function; other test resultsare shown in Table 1.A diagnostic test was performed.Differ en ti a l Di agnosisDr. J. Carl Pallais: I am aware of the diagnosis inthis case. Two striking features are the repeatedlylow oxygen saturation levels as measured bypulse oximetry (SpO 2 ), despite the patient’s normalphysical examination and chest radiograph,and the unexpectedly low hemoglobin A 1c measurements,despite the patient’s reportedly poorglycemic control and elevated fructosamine levels.Causes of Low Oxygen Saturationon Pulse OximetryHypoxemiaPulse oximeters rely on the differential absorptionof oxyhemoglobin and reduced hemoglobinat two wavelengths of light, 660 nm and 940 nm,to estimate the functional saturation of oxygen(oxygen saturation in arterial blood). The functionalsaturation of oxygen is calculated as oxyhemoglobindivided by the sum of oxyhemoglobinand reduced hemoglobin. By measuring theamount of light absorbed at each wavelength duringarterial pulses and factoring out the “static”background absorption, pulse oximeters calculatean arterial absorption ratio that is then convertedto oxygen saturation readings <strong>with</strong> the useof empirically derived data. 1Low SpO 2 measurements are a common indicatorof hypoxemia. 2 Acute (as opposed to chronic)causes of hypoxemia (e.g., pneumonia andpulmonary embolism) are frequently associated<strong>with</strong> clinical signs and symptoms, such as airhunger, diaphoresis, tachypnea, and tachycardia.These clinical markers may be masked in severalchronic pulmonary and cardiovascular conditions,despite low SpO 2 readings. 3 In this patient,the repeatedly low pulse oximetry measurementsover the course of months to years,<strong>with</strong>out acute signs of hypoxemia, suggest achronic cause. However, the absence of clubbing,jugular venous distention, abnormal cardiac orlung findings on examination, and polycythemia,as well as the normal appearance of the heartand lungs on chest radiographs, argue stronglyagainst chronic hypoxemia. Although chronichypoxemia can be associated <strong>with</strong> remarkableclinical compensation, it still leaves patients <strong>with</strong>limited reserves. In this patient, who probablyhas a viral infection of the upper airway, thenormal vital signs and unremarkable examinationprovide additional support for the suppositionthat hypoxemia was not the cause of his lowSpO 2 values.Measurement ErrorsWithout other evidence of hypoxemia, factorsthat interfere <strong>with</strong> pulse oximetry measurementsneed to be considered in this case. 1,2 The normalphysical examination and the multiple low SpO 2measurements that were made <strong>with</strong> different devicesat different times make it unlikely thattechnical artifacts or inadequate detection of arterialpulse waves explains the low readings. Thenormal hemoglobin electrophoresis rules outrare hemoglobin variants that can alter the lightabsorptionspectra of hemoglobin and producefalsely low SpO 2 readings. 4,5 Some hemoglobinspecies, such as sulfhemoglobin and methemoglobin,have characteristic light-absorption spectrathat can result in falsely low SpO 2 values. 4This patient had not been exposed to sulfonamides,but he did take dapsone, which suggeststhat methemoglobinemia is the cause of the lowSpO 2 values. 6Dapsone and MethemoglobinemiaMethemoglobin is formed when the iron moleculein heme is oxidized from its ferrous (Fe 2+ )form to its ferric (Fe 3+ ) state. Methemoglobinnormally accounts for less than 2% of total hemoglobin.It is formed at a low rate through theprocess of oxygen transport, and the rate of formationis balanced by its reduction back to theferrous state by cytochrome-b 5 reductase. Althoughmethemoglobinemia can be caused by inheritedmutations affecting its reduction, acquired causesare much more common and result from increasedmethemoglobin formation. 4 Dapsone use is oneof the most common causes of acquired methemoglobinemia,accounting for nearly half thecases in a large case series. 6 Dapsone undergoesN‐hydroxylation by various P-450 enzymes in theliver to form N-hydroxy dapsone, and it is thismetabolite, rather than the drug itself, that resultsin methemoglobinemia. This hydroxylamineproduct mediates the oxidation of the iron moleculeof heme to produce methemoglobin in adose-dependent fashion. 7n engl j med 364;10 nejm.org march 10, <strong>2011</strong> 959The New England Journal of MedicineDownloaded from nejm.org at MEIJI-YAKKA-U-TANASHI (D) on May 22, 2012. For personal use only. No other uses <strong>with</strong>out permission.Copyright © <strong>2011</strong> Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

case records of the massachusetts gener al hospitaldeficiency, dapsone causes severe hemolysis, sinceless reduced glutathione is available to handlethe oxidative injury. Unlike substances that causehemolysis only in persons <strong>with</strong> G6PD deficiency,dapsone can cause hemolysis in persons <strong>with</strong>normal G6PD levels, albeit in a less severe form. 7<strong>Old</strong>er erythrocytes may be more susceptible todapsone-induced destruction, owing to waningG6PD activity. 9 This patient had many markers ofhemolysis, including unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia,an elevated lactate dehydrogenase level,and reticulocytosis. Since he had only mild anemiadespite the moderately high dapsone dose, itis likely that he had normal G6PD activity.Because older erythrocytes are more susceptibleto oxidative injury 9 and contain more glycatedhemoglobin than do younger cells, the mechanismby which dapsone induces red-cell destructionmay have a particularly profound effect in loweringhemoglobin A 1c levels. Several case reportshave shown that dapsone artificially lowers hemoglobinA 1c levels. 24-27 One study of patients<strong>with</strong> diabetes in whom dapsone was administeredafter islet-cell transplantation showed thatdapsone lowered hemoglobin A 1c levels but hadno effect on fructosamine levels. 28 This result isconsistent <strong>with</strong> the findings in this patient, whohad low-to-normal hemoglobin A 1c levels despiteelevated fructosamine levels.SummaryIn summary, dapsone is the likely cause of thispatients low SpO 2 levels and falsely low hemoglobinA 1c levels (Fig. 1). This case illustrates theimportance of understanding potential pitfalls inthe measurement of such values as oxygen saturationand hemoglobin A 1c and reminds us thatclinically significant hemolysis can occur <strong>with</strong>the use of dapsone, even in patients <strong>with</strong>outG6PD deficiency.Dr. Nancy Lee Harris (Pathology): Dr. Bhattacharyya,would you tell us your thinking when yousaw this patient?Dr. Bhattacharyya: My reasoning was similar tothat of Dr. Pallais. The discordance between thepatient’s hemoglobin A 1c level and his glucoseand fructosamine readings, as well as his unconjugatedhyperbilirubinemia, made me suspectthat dapsone-induced hemolysis was causing thelow hemoglobin A 1c measurements and unconjugatedhyperbilirubinemia. A review of hospitalrecords from 2001 subsequently confirmed thatTable 2. Factors Affecting Hemoglobin A 1c Measurements.*Factors that decrease hemoglobin A 1c levelsDecreased mean red-cell ageDecreased red-cell life span owing to hemolysis (from congenital causes, immune-mediatedcauses, drugs, or illness such as disseminated intravascularcoagulation or malaria), liver disease, or splenomegalyIncreased % of young red cells (reticulocytes) owing to erythropoietintherapy, hemorrhage, or hemolysisTransfusionsHigh doses of vitamins C and EHuman immunodeficiency virus infectionDialysisPregnancyFactors that increase hemoglobin A 1c levelsIncreased mean red-cell ageIncreased red-cell life span owing to splenectomyDecreased % of young red cells (reticulocytes) such as in aplastic anemiaIron deficiencyIncreasing age of personFactors <strong>with</strong> various effects on hemoglobin A 1c levels†HemoglobinopathiesNonglucose adductsCarbamylation (uremia)Acetylation (salicylates)Acetaldehyde (alcohol)HypertriglyceridemiaOpiate addictionPotential variantsRed-cell permeabilityGlycation efficiency* Data are from Nathan et al., 14 Bloomgarden, 19 NGSP, 20 and Saudek et al. 22† The effects largely depend on the assay method.his hemoglobin A 1c level was markedly elevatedbefore he started dapsone therapy. Venous bloodshowed a methemoglobin level of 9.7%, as measuredby CO-oximetry. A subsequent arterialsample showed a partial pressure of arterial oxygen(PaO 2 ) that was normal at 83 mm Hg (referencerange, 80 to 100) and an oxygen saturationof 96%. The sample was obtained while the patientwas breathing ambient air and had an oxygensaturation of 87% as measured by pulse oximetry,confirming the incorrect pulse oximetryreading. The arterial blood methemoglobin levelwas 16.5%, and the venous level, in a sampledrawn at the same time, was 11.5%. Despite thenormal PaO 2 value, the arterial sample had a darkappearance that is characteristic of methemoglobinemia.n engl j med 364;10 nejm.org march 10, <strong>2011</strong> 961The New England Journal of MedicineDownloaded from nejm.org at MEIJI-YAKKA-U-TANASHI (D) on May 22, 2012. For personal use only. No other uses <strong>with</strong>out permission.Copyright © <strong>2011</strong> Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

T h e n e w e ngl a nd j o u r na l o f m e dic i n eFigure 1. Dapsone-Induced Methemoglobinemia and Red-Cell Destruction Resulting in Artificially Low Oxygen Saturation and HemoglobinA 1c Measurements.Dapsone is converted into a hydroxylamine metabolite by cytochrome P-450 enzymes in the liver. N-hydroxy dapsone causes the oxidationof the heme moiety, which results in the formation of methemoglobin. Methemoglobinemia causes falsely low oxygen saturationlevels as measured by pulse oximetry (SpO 2 ) by changing the light absorption ratios of pulse oximeters. N-hydroxy dapsone also causesred-cell destruction through oxidative damage. The increased susceptibility of older erythrocytes to oxidative injury due to waning glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity and the resulting reticulocytosis lower the average red-cell age and artificially lower hemoglobin A 1cmeasurements. Cimetidine decreases the formation of the hydroxylamine metabolite by inhibiting various cytochrome P-450 enzymes.Clinic a l Di agnosisDapsone-induced methemoglobinemia and hemolysis,resulting in falsely low SpO 2 and hemoglobinA 1c measurements.Dr . J. C a r l Pa ll a is’s Di agnosisDapsone-induced methemoglobinemia and hemolysis,resulting in falsely low SpO 2 and hemoglobinA 1c measurements.962n engl j med 364;10 nejm.org march 10, <strong>2011</strong>The New England Journal of MedicineDownloaded from nejm.org at MEIJI-YAKKA-U-TANASHI (D) on May 22, 2012. For personal use only. No other uses <strong>with</strong>out permission.Copyright © <strong>2011</strong> Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

case records of the massachusetts gener al hospitalDiscussion of M a nagemen tDr. Bhattacharyya: After the diagnosis was established,the issue of how to manage the dermatitisherpetiformis became critical.Dr. Bonnie T. Mackool: This patient has dermatitisherpetiformis, an intensely pruritic, papulovesiculareruption (called “herpetiform” because of thegrouped distribution of vesicular lesions) 29,30 thattypically develops between 30 and 40 years ofage, more commonly in men. 31 Although this patientdoes not have the gastrointestinal symptomsof celiac disease, 32-36 dermatitis herpetiformis isan autoimmune condition related to gluten sensitivity,31 and as many as 92% of patients reportedlyhave evidence of gluten-sensitive enteropathyon endoscopy. 35,36 The intense pruritus and sometimesthe burning or stinging associated <strong>with</strong>lesions of dermatitis herpetiformis severely affectthe quality of life, as they did in this patient.Since dermatitis herpetiformis is a manifestationof gluten sensitivity, the mainstay of treatmentis a lifelong gluten-free diet, just as it is forceliac disease. 37-40 Dietary treatment may alleviatethe gastrointestinal symptoms of celiac diseaseafter as short a period as 2 weeks, but cutaneoussymptoms typically require 5 to 12 monthsfor partial improvement and up to 2 years forcomplete improvement <strong>with</strong> a gluten-free dietalone. 41 For this reason, dapsone is used duringthe first several months of a gluten-free diet,until the diet controls the symptoms. Dapsoneprovides dramatic improvement <strong>with</strong>in 24 to 36hours, often after the first dose. Side effects, inaddition to methemoglobinemia and hemolysis,include agranulocytosis, liver dysfunction, andperipheral neuropathy. Since most side effectsare dose-related, the aim is to decrease the doseafter several months of a gluten-free diet andeventually eliminate the use of dapsone. 42,43 Acomplete blood count and liver-function testsshould be performed regularly, and the methemoglobinlevel should be monitored accordingto the patient’s symptoms and coexisting conditions.43 All potential side effects of dapsoneshould be discussed <strong>with</strong> the patient.Other medications, such as sulfapyridine, 44,45colchicine, azathioprine, cyclosporine, tetracycline,nicotinamide, and topical and systemic glucocorticoids,and ultraviolet light may offer somerelief from dermatitis herpetiformis, but they areless effective than dapsone. It is crucial that thispatient be persuaded to adhere to a gluten-freediet, which will not only prevent the recurrenceof dermatitis herpetiformis and eliminate theneed for dapsone but also provide protectionagainst the development of gastrointestinal lymphoma,a known and often fatal complication ofuntreated gluten sensitivity. 46Dr. Bhattacharyya: Dapsone had dramaticallyimproved the patient’s disabling cutaneous symptoms,and he was unwilling to discontinue themedication, despite the associated complications.He indicated that he would rather give up insulinthan dapsone. Repeat testing for endomysialantibodies and testing for tissue transglutaminasewere positive. Nevertheless, he was stronglyopposed to initiating a gluten-free diet, since hisdiet was already restricted by the diabetes. In consultation<strong>with</strong> a gastroenterologist, a duodenalbiopsy was recommended.Pathol o gic a l DiscussionDr. Martha Bishop Pitman: The patient’s diagnosisof dermatitis herpetiformis had been established8 years earlier by examination of a 3-mm punchbiopsyspecimen of the skin, which revealed accumulationsof neutrophils and eosinophils thatformed small microabscesses at the tips of adjoiningdermal papillae (Fig. 2A). Direct immunofluorescencestaining for IgA highlighted a granulardeposition pattern at the dermal–epidermaljunction, which is the diagnostic hallmark of thedisease. 32,34<strong>Upper</strong> gastrointestinal endoscopy revealedmild erythema and nodularity and subtle scallopingof the plicae circulares in the duodenum.Histologic examination of a biopsy specimenshowed blunted and atrophic villi, crypt hyperplasia,and marked intraepithelial lymphocytosis,features that are diagnostic of celiac disease(Fig. 2B, 2C, and 2D).The patient now has three diagnoses — type1 diabetes mellitus, dermatitis herpetiformis, andceliac disease — but does he really have threediseases, or just one? Dermatitis herpetiformis isthe cutaneous manifestation of celiac disease.Patients <strong>with</strong> celiac disease, our patient, and mostpatients <strong>with</strong> dermatitis herpetiformis have elevatedtissue transglutaminase levels, as well as anti–endomysial IgA antibodies in their serum. 32,47,48Patients <strong>with</strong> dermatitis herpetiformis also haveantibodies to the closely related epidermal trans-n engl j med 364;10 nejm.org march 10, <strong>2011</strong> 963The New England Journal of MedicineDownloaded from nejm.org at MEIJI-YAKKA-U-TANASHI (D) on May 22, 2012. For personal use only. No other uses <strong>with</strong>out permission.Copyright © <strong>2011</strong> Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

T h e n e w e ngl a nd j o u r na l o f m e dic i n eABCDFigure 2. Biopsy Specimens and Findings from <strong>Upper</strong> Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.A punch-biopsy specimen of a skin lesion from 8 years earlier (Panel A, hematoxylin and eosin) shows spongiosis ofthe epidermis and small subepidermal vesicles (inset), <strong>with</strong> an accumulation of neutrophils and eosinophils formingsmall microabscesses at the tips of adjoining dermal papillae (arrow), features that are consistent <strong>with</strong> dermatitisherpetiformis. <strong>Upper</strong> gastrointestinal endoscopy (Panel B) revealed mild erythema and nodularity and subtle scalloping(arrows) of the plicae circulares in the duodenum. (Image courtesy of Dr. Michael Thiim.) The duodenal-biopsyspecimen (Panel C, hematoxylin and eosin) shows blunted and atrophic villi (long arrow), crypt hyperplasia (shortarrows), and marked intraepithelial lymphocytosis, features that establish the diagnosis of celiac disease. Immunoperoxidasestaining <strong>with</strong> anti-CD3, which stains T cells brown, highlights the marked intraepithelial lymphocytosisin the damaged villi (Panel D).glutaminase, the purported autoantigen in theskin and the most sensitive serologic marker fordermatitis herpetiformis. 11,49,50In the majority of patients <strong>with</strong> dermatitisherpetiformis, enteropathy is mild or asymptomatic,resulting in the under diagnosis of celiacdisease. After a diagnosis of celiac disease hasbeen established, a diagnosis of dermatitis herpetiformisis made in approximately 5 to 10% ofpatients. 51,<strong>52</strong> Examination of intestinal-biopsyspecimens obtained from patients <strong>with</strong> dermatitisherpetiformis and symptoms suggestive ofceliac disease has shown that 69% of these patientshave classic evidence of intestinal injurymimicking that of celiac disease, and 93% haveevidence of mucosal injury manifested as intraepitheliallymphocytosis. 32An association between type 1 diabetes mellitusand celiac disease has long been well established,but the high prevalence (approximately10% of children and 2% of adults <strong>with</strong> type 1diabetes also have celiac disease) has been reportedmore recently. 53 The relationship between thesetwo inflammatory diseases is believed to haveboth a genetic and an environmental basis. Thediseases share an association <strong>with</strong> the HLA classII locus HLA-DQB1 on chromosome 6p21. Genomewideassociation studies have identified8 chromosome regions outside the HLA regionin celiac disease 54 and 15 non-HLA regions in964n engl j med 364;10 nejm.org march 10, <strong>2011</strong>The New England Journal of MedicineDownloaded from nejm.org at MEIJI-YAKKA-U-TANASHI (D) on May 22, 2012. For personal use only. No other uses <strong>with</strong>out permission.Copyright © <strong>2011</strong> Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

case records of the massachusetts gener al hospitalpatients <strong>with</strong> type 1 diabetes mellitus. 55,56 Anotherstudy showed seven shared alleles in thesetwo disorders, which suggested a common biologicmechanism. 57 Combinations of specificalleles, together <strong>with</strong> epigenetic influences andchance, lead to these various autoimmune-relatedinflammatory conditions, which may appear asa single condition in some persons and as combineddiseases in others.Thus, this patient may have just one underlyingpathobiologic condition, manifested as type 1diabetes mellitus, dermatitis herpetiformis, andceliac disease.Dr. Harris: Dr. Bhattacharyya, would you tell uswhat happened <strong>with</strong> this patient?Dr. Bhattacharyya: Since the patient initially declinedto discontinue or lower the dapsone dose,we started treatment <strong>with</strong> cimetidine. Cimetidinehas been shown to decrease dapsone-inducedmethemoglobinemia by reducing the formationof the toxic hydroxylamine metabolite throughthe inhibition of several cytochrome P-450 enzymes,<strong>with</strong>out affecting the therapeutic activityof dapsone. 44 When the patient was receivinghigh doses of cimetidine, the methemoglobinlevels dropped from a range of 9 to 16% to approximately6%. After the results of the duodenalbiopsy were reported, the patient’s wife removedgluten-containing foods from the house,so that the patient is on a gluten-free diet at leaston weekends. Even though he does not adhere tothe diet while at work, we were able to successfullyreduce his dose of dapsone to 100 mg perday. One year after the diagnosis, his methemoglobinlevel was 2.1%. The lactate dehydrogenaseand bilirubin levels have improved but continueto be slightly elevated, and the hemoglobin A 1clevel continues to be low, despite poor glycemiccontrol, so the patient still has dapsone-inducedhemolysis. His caregivers are encouraging betteradherence to the gluten-free diet.Dr. Lloyd Axelrod (Diabetes Unit): Given the highsensitivity and specificity of serologic tests forceliac disease, what was the indication for a duodenalbiopsy?Dr. Pallais: Intestinal biopsy remains the definitivemethod of establishing the diagnosis ofceliac disease, although its role in high-risk personssuch as this patient is debated. Since thepatient was asymptomatic, he may not have fullyappreciated his risk of enteropathy, and thisprobably contributed to his resistance to start agluten-free diet. Indeed, after the biopsy, weheard that he modified his diet to decrease hisgluten intake.Dr. Axelrod: If a patient adheres to and has atherapeutic response to a gluten-free diet, wouldit perhaps not be necessary to do a biopsy?Dr. Pallais: That is probably correct.A NAT OMIC A L DI AGNOSESGluten sensitivity, <strong>with</strong> dermatitis herpetiformisand celiac disease.Methemoglobinemia and nonimmune hemolysisdue to dapsone, resulting in falsely low oxygensaturation levels as measured by pulse oximetryand falsely low hemoglobin A 1c levels.This case was presented at the Medical <strong>Case</strong> Conference.Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available <strong>with</strong>the full text of this article at NEJM.org.We thank Dr. David Dudzinski, who first considered the diagnosesof methemoglobinemia and hemolysis in this patient,for contributions to the case history; Drs. Daniela Kroshinskyand James L. Young for providing recent follow-up information;and Dr. David Nathan for contributions regarding thefactors that affect measurements of hemoglobin A 1c.References1. Tremper KK, Barker SJ. Pulse oximetry.Anesthesiology 1989;70:98-108.2. <strong>Case</strong> Records of the MassachusettsGeneral Hospital (<strong>Case</strong> 23-2004). N Engl JMed 2004;351:380-7.3. Pierson DJ. Pathophysiology and clinicaleffects of chronic hypoxia. Respir Care2000;45:39-51.4. Haymond S, Cariappa R, Eby CS, ScottMG. Laboratory assessment of oxygenationin methemoglobinemia. Clin Chem2005;51:434-44.5. Zur B, Hornung A, Breuer J, et al.A novel hemoglobin, Bonn, causes falselydecreased oxygen saturation measurementsin pulse oximetry. Clin Chem 2008;54:594-6.6. Ash-Bernal R, Wise R, Wright SM.Acquired methemoglobinemia: a retrospectiveseries of 138 cases at 2 teachinghospitals. Medicine (Baltimore) 2004;83:265-73.7. Jollow DJ, Bradshaw TP, McMillanDC. Dapsone-induced hemolytic anemia.Drug Metab Rev 1995;27:107-24.8. Barker SJ, Tremper KK, Hyatt J. Effectsof methemoglobinemia on pulse oximetryand mixed venous oximetry. Anesthesiology1989;70:112-7.9. Wright RO, Lewander WJ, Woolf AD.Methemoglobinemia: etiology, pharmacology,and clinical management. Ann EmergMed 1999;34:646-56.10. Guay J. Methemoglobinemia related tolocal anesthetics: a summary of 242 episodes.Anesth Analg 2009;108:837-45.11. Armbruster DA. Fructosamine: structure,analysis, and clinical usefulness.Clin Chem 1987;33:2153-63.12. Bunn HF, Haney DN, Kamin S, GabbayKH, Gallop PM. The biosynthesis ofhuman hemoglobin A1c: slow glycosylationof hemoglobin in vivo. J Clin Invest1976;57:16<strong>52</strong>-9.13. Staley MJ. Fructosamine and proteinn engl j med 364;10 nejm.org march 10, <strong>2011</strong> 965The New England Journal of MedicineDownloaded from nejm.org at MEIJI-YAKKA-U-TANASHI (D) on May 22, 2012. For personal use only. No other uses <strong>with</strong>out permission.Copyright © <strong>2011</strong> Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

case records of the massachusetts gener al hospitalconcentrations in serum. Clin Chem 1987;33:2326-7.14. Nathan DM, Kuenen J, Borg R, ZhengH, Schoenfeld D, Heine RJ. Translatingthe A1C assay into estimated average glucosevalues. Diabetes Care 2008;31:1473-8.[Erratum, Diabetes Care 2009;32:207.]15. International Expert Committee reporton the role of the A1C assay in the diagnosisof diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009;32:1327-34.16. Standards of medical care in diabetes— 2010. Diabetes Care 2010;33:Suppl 1:S11-S61.17. Mendlovic DB, Whitehouse FW, ForebackCC. The why and wherefore of fructosamine.Henry Ford Hosp Med J 1992;40:149-51.18. Tahara Y, Shima K. Kinetics of HbA1c,glycated albumin, and fructosamine andanalysis of their weight functions againstpreceding plasma glucose level. DiabetesCare 1995;18:440-7.19. Bloomgarden ZT. A1C: recommendations,debates, and questions. DiabetesCare 2009;32(12):e141-e147.20. Factors that interfere <strong>with</strong> GHB(HbA1c) test results. NGSP 2010. (http://www.ngsp.org/factors.asp.)21. Saudek CD, Derr RL, Kalyani RR. Assessingglycemia in diabetes using selfmonitoringblood glucose and hemoglobinA1c. JAMA 2006;295:1688-97.22. Saudek CD, Herman WH, Sacks DB,Bergenstal RM, Edelman D, DavidsonMB. A new look at screening and diagnosingdiabetes mellitus. J Clin EndocrinolMetab 2008;93:2447-53.23. Cohen RM, Smith EP. Frequency ofHbA1c discordance in estimating bloodglucose control. Curr Opin Clin NutrMetab Care 2008;11:512-7.24. Albright ES, Ovalle F, Bell DS. Artificiallylow hemoglobin A1c caused by useof dapsone. Endocr Pract 2002;8:370-2.25. Bertholon M, Mayer A, Francina A,Thivolet CH. Interference of dapsone inHbA1c monitoring of a type I diabetic patient<strong>with</strong> necrobiosis lipoidica. DiabetesCare 1994;17:1364.26. Serratrice J, Granel B, Swiader L, et al.Interference of dapsone in HbA1c monitoringof a diabetic patient <strong>with</strong> polychondritis.Diabetes Metab 2002;28:508-9.27. Tack CJ, Wetzels JF. Decreased HbA1clevels due to sulfonamide-induced hemolysisin two IDDM patients. Diabetes Care1996;19:775-6.28. Froud T, Faradji RN, Gorn L, et al.Dapsone-induced artifactual a1c reductionin islet transplant recipients. Transplantation2007;83:824-5.29. Duhring L. Dermatitis herpetiformis.JAMA 1884;3:225.30. Fry L, Keir P, McMinn RM, Cowan JD,Hoffbrand AV. Small-intestinal structureand function and haematological changesin dermatitis herpetiformis. Lancet 1967;2:729-33.31. Gawkrodger DJ, Blackwell JN, GilmourHM, Rifkind EA, Heading RC, BarnetsonRS. Dermatitis herpetiformis: diagnosis,diet and demography. Gut 1984;25:151-7.32. Alonso-Llamazares J, Gibson LE,Rogers RS III. Clinical, pathologic, andimmunopathologic features of dermatitisherpetiformis: review of the Mayo Clinicexperience. Int J Dermatol 2007;46:910-9.33. Caproni M, Antiga E, Melani L, FabbriP. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatmentof dermatitis herpetiformis. J EurAcad Dermatol Venereol 2009;23:633-8.34. Fry L, Seah PP. Dermatitis herpetiformis:an evaluation of diagnostic criteria.Br J Dermatol 1974;90:137-46.35. Fry L, Seah PP, McMinn RM, HoffbrandAV. Lymphocytic infiltration of epitheliumin diagnosis of gluten-sensitiveenteropathy. BMJ 1972;3:371-4.36. Galvez L, Falchuk ZM. Dermatitis herpetiformis:gastrointestinal association.Clin Dermatol 1991;9:325-33.37. Fry L, McMinn RM, Cowan JD, HoffbrandAV. Effect of gluten-free diet ondermatological, intestinal, and haematologicalmanifestations of dermatitis herpetiformis.Lancet 1968;1:557-61.38. Idem. Gluten-free diet and reintroductionof gluten in dermatitis herpetiformis.Arch Dermatol 1969;100:129-35.39. Pink IJ, Creamer B. Response to agluten-free diet of patients <strong>with</strong> the coeliacsyndrome. Lancet 1967;1:300-4.40. Hardman CM, Garioch JJ, LeonardJN, et al. Absence of toxicity of oats inpatients <strong>with</strong> dermatitis herpetiformis.N Engl J Med 1997;337:1884-7.41. Garioch JJ, Lewis HM, Sargent SA,Leonard JN, Fry L. 25 <strong>Year</strong>s’ experience ofa gluten-free diet in the treatment of dermatitisherpetiformis. Br J Dermatol 1994;131:541-5.42. Katz SI, Hall RP III, Lawley TJ, StroberW. Dermatitis herpetiformis: the skin andthe gut. Ann Intern Med 1980;93:857-74.43. Leonard JN, Fry L. Treatment andmanagement of dermatitis herpetiformis.Clin Dermatol 1991;9:403-8.44. Coleman MD. Dapsone: modes of action,toxicity and possible strategies forincreasing patient tolerance. Br J Dermatol1993;129:507-13.45. Paniker U, Levine N. Dapsone and sulfapyridine.Dermatol Clin 2001;19:79-86.46. Lewis HM, Renaula TL, Garioch JJ,et al. Protective effect of gluten-free dietagainst development of lymphoma in dermatitisherpetiformis. Br J Dermatol 1996;135:363-7.47. Chorzelski TP, Jablonska S. IgA lineardermatosis of childhood (chronic bullousdisease of childhood). Br J Dermatol 1979;101:535-42.48. Dieterich W, Ehnis T, Bauer M, et al.Identification of tissue transglutaminaseas the autoantigen of celiac disease. NatMed 1997;3:797-801.49. Marietta EV, Camilleri MJ, Castro LA,Krause PK, Pittelkow MR, Murray JA.Transglutaminase autoantibodies in dermatitisherpetiformis and celiac sprue.J Invest Dermatol 2008;128:332-5.50. Sárdy M, Kárpáti S, Merkl B, PaulssonM, Smyth N. Epidermal transglutaminase(TGase 3) is the autoantigen of dermatitisherpetiformis. J Exp Med 2002;195:747-57.51. Egan CA, O’Loughlin S, Gormally S,Powell FC. Dermatitis herpetiformis:a review of fifty-four patients. Ir J Med Sci1997;166:241-4.<strong>52</strong>. Gawkrodger DJ, Vestey JP, O’MahonyS, Marks JM. Dermatitis herpetiformis andestablished coeliac disease. Br J Dermatol1993;129:694-5.53. Mäki M, Mustalahti K, Kokkonen J,et al. Prevalence of celiac disease amongchildren in Finland. N Engl J Med 2003;348:2517-24.54. Hunt KA, Zhernakova A, Turner G,et al. Newly identified genetic risk variantsfor celiac disease related to the immuneresponse. Nat Genet 2008;40:395-402.55. Cooper JD, Smyth DJ, Smiles AM, et al.Meta-analysis of genome-wide associationstudy data identifies additional type 1 diabetesrisk loci. Nat Genet 2008;40:1399-401.56. Todd JA, Walker NM, Cooper JD, et al.Robust associations of four new chromosomeregions from genome-wide analysesof type 1 diabetes. Nat Genet 2007;39:857-64.57. Smyth DJ, Plagnol V, Walker NM, et al.Shared and distinct genetic variants intype 1 diabetes and celiac disease. N EnglJ Med 2008;359:2767-77.Copyright © <strong>2011</strong> Massachusetts Medical Society.Lantern Slides Updated: Complete PowerPoint Slide Sets from the Clinicopathological ConferencesAny reader of the Journal who uses the <strong>Case</strong> Records of the Massachusetts General Hospital as a teaching exercise or reference material is now eligible toreceive a complete set of PowerPoint slides, including digital images, <strong>with</strong> identifying legends, shown at the live Clinicopathological Conference (CPC)that is the basis of the <strong>Case</strong> Record. This slide set contains all of the images from the CPC, not only those published in the Journal. Radiographic, neurologic,and cardiac studies, gross specimens, and photomicrographs, as well as unpublished text slides, tables, and diagrams, are included. Every year 40sets are produced, averaging 50-60 slides per set. Each set is supplied on a compact disc and is mailed to coincide <strong>with</strong> the publication of the <strong>Case</strong> Record.The cost of an annual subscription is $600, or individual sets may be purchased for $50 each. Application forms for the current subscription year,which began in January, may be obtained from the Lantern Slides Service, Department of Pathology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA02114 (telephone 617-726-2974) or e-mail Pathphotoslides@partners.org.966n engl j med 364;10 nejm.org march 10, <strong>2011</strong>The New England Journal of MedicineDownloaded from nejm.org at MEIJI-YAKKA-U-TANASHI (D) on May 22, 2012. For personal use only. No other uses <strong>with</strong>out permission.Copyright © <strong>2011</strong> Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.