yBg7W

yBg7W

yBg7W

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

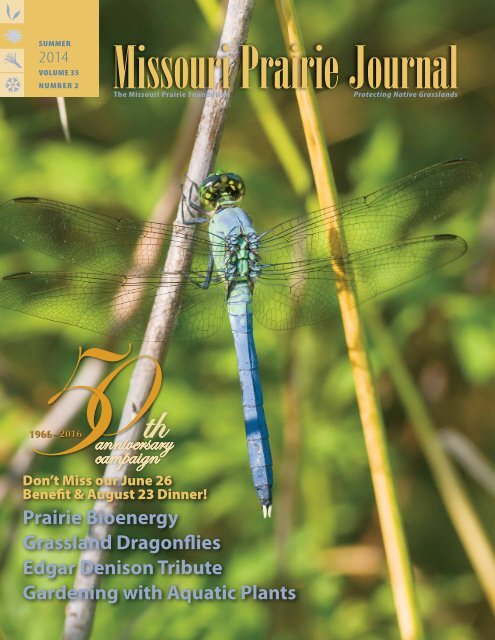

summer2014Volume 35Number 2Missouri Prairie JournalThe Missouri Prairie FoundationProtecting Native GrasslandsthanniversarycampaignDon’t Miss our June 26Benefit & August 23 Dinner!Prairie BioenergyGrassland DragonfliesEdgar Denison TributeGardening with Aquatic Plants

Message from the PresidentIt seems like just a couple of years ago I was preparing a talk for the40 th anniversary of the Missouri Prairie Foundation. Now, we are gearingup to celebrate the 50 th in 2016 by launching our 50 th AnniversaryFundraising Campaign this summer. Time flies when you are having fun, andit is a pleasure to play a role in preserving remaining prairies, knowing thesenow rare natural communities have been around for several thousand years.I feel strongly that, if we study them, these remnant prairies hold the keysfor many solutions to 21 st century challenges such as food and energy security,economic development, and biodiversity adaptation to climate change.We have an example of one such creativesolution in this issue, “Grassland RestorationMPF membershave made thisnearly 50-year-oldorganization andits conservationaccomplishmentspossible. I inviteall members tojoin me in takingpart in our 50thAnniversaryCampaign, to investin future prairieprotection.to Renewable Energy.” The article describesMPF Technical Advisor Rudi Roeslein’s multidisciplinaryapproach to an environmentalproblem that harnesses ecosystem servicesof prairie plants to provide bioenergy, cleanwater, wildlife habitat, and carbon sequestration.Roeslein’s plan is a shining example ofwhat is possible.As we move forward into the second halfcentury of our conservation work, we welcomeyour involvement and ideas to expandour organization and apply knowledge gainedfrom ancient, remnant plant communities forlandscape-scale solutions to environmentalchallenges.I look forward to seeing you at our Prairies& Pollinators event on June 26 in Kansas Cityand our MPF Annual Dinner to benefit MPFon August 23 in Springfield, featuring Dr.Peter Raven as our guest speaker. Please see theback cover for details about these exciting eveningsand other upcoming events. I hope youenjoy this issue.Jon R. Wingo, PresidentMissouri Prairie Foundation Grow Native!Committee Chair Carrie Coyne, holdingLUSH Charity Pot Lotion, with, from left,Elaine Chollet, Sara Stoker, and KelseyEversmeyer of LUSH Cosmetics. Manythanks to LUSH for its 2014 supportof the Missouri Prairie Journal and forhosting MPF in its St. Louis Galleriastore on May 3.The mission of the Missouri Prairie Foundation (MPF)is to protect and restore prairie and othernative grassland communities throughacquisition, management, education, and research.OfficersPresident Jon Wingo, Wentzville, MOImmediate Past President Stanley M. Parrish, Walnut Grove, MOVice President Doris Sherrick, Peculiar, MOVice President of Science and Management Bruce Schuette, Troy, MOSecretary Van Wiskur, Pleasant Hill, MOTreasurer Laura Church, Kansas City, MODirectorsSusan E. Appel, Leawood, KSDale Blevins, Independence, MOGlenn Chambers, Columbia, MOBrian Edmond, Walnut Grove, MOMargo Farnsworth, Smithville, MOPage Hereford, St. Louis, MOScott Lenharth, Nevada, MOWayne Morton, M.D., Osceola, MOSteve Mowry, Trimble, MODonnie Nichols, Warsaw, MOJan Sassmann, Bland, MOBonnie Teel, Rich Hill, MOPresidential AppointeesDoug Bauer, St. Louis, MOGalen Hasler, M.D., Madison, WIRick Thom, Jefferson City, MOEmeritusBill Crawford, Columbia, MOBill Davit, Washington, MOLowell Pugh, Golden City, MOOwen Sexton, St. Louis, MOTechnical AdvisorsMax Alleger, Clinton, MOJeff Cantrell, Neosho, MOSteve Clubine, Windsor, MODennis Figg, Jefferson City, MOMike Leahy, Jefferson City, MODr. Quinn Long, St. Louis, MORudi Roeslein, St. Louis, MOJames Trager, Pacific, MOStaffCarol Davit, Executive Director and Missouri Prairie Journal Editor,Jefferson City, MORichard Datema, Prairie Operations Manager, Springfield, MOCarol Davit2 Missouri Prairie Journal Vol. 35 No. 2

MPFupdatePrairie Conservation, Education, and OutreachNative Bee Expert Mike Arduser andMPF Executive Director Carol Davit atthe Maritz Green Vendor Fair on May 7,sharing the importance of prairie,pollinators, and native plants withMaritz employees.MPF Board Member Scott Lenharthrecently found additional species atStilwell Prairie: the fall-bloomingdowny gentian (Gentiana puberulenta),above, Indian turnip (Pediomelumesculentum), blue star (Amsoniaillustris), and biscuitroot (Lomatiumfoeniculaceum).Casey GalvinThe year-round management of the Missouri Prairie Foundation’s (MPF’s) prairies requiresrelentless vigilance and hard physical labor. This work is carried out daily by MPF’s PrairieOperations Manager Richard Datema, and also regularly by board members and volunteersScott Lenharth, Stan Parrish, and Brian Edmond. Many other members volunteer as well, and allefforts are greatly appreciated.The results of their diligence are evident in the high number of native prairie species sustainedon MPF land, and documented in such reports as the Golden Prairie Floristic Integrity Reportprepared by Justin Thomas of the Institute for Botanical Training, funded by MPF in 2013.MPF continues aggressive restoration of its Stilwell Prairie, a 376-acre tract in Vernon County.Thanks to funding from a Missouri Bird Conservation Initiative Grant, a Missouri ConservationHeritage Foundation grant, funding from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and contributionsfrom MPF members, more than 90 acres of this tract were cleared of trees through the work ofa tree-grinding contractor. Datema also is controlling fescue and sericea lespedeza, and handcutting woody invasives as part of MPF’s Stilwell Prairie Restoration Plan. A WHIP contract from theNatural Resources Conservation Service, secured through the efforts of MPF board member ScottLenharth, is making possible the restoration planting of eight hillside acres at Stilwell.MPF is also working to continually improve its management methods. Led by Vice Presidentof Science and Management Bruce Schuette, MPF is working to refine the use of herbicides tocontrol invasives while also protecting prairie shrubs, and adjusting prescribed burning protocolsto benefit the broadest number of prairie species.MPF has exciting news regarding prairie pollinators: we are able to contract with Native BeeExpert Mike Arduser, recently retired from the Missouri Department of Conservation, to conductseveral pollinator surveys on MPF land in 2014, as well as carry out some outreach and educationendeavors.From January to May, MPF staff, several board members, and other volunteers engaged innumerous outreach activities to present the prairie conservation message and promote the useof native plants. Numerous Missouri Master Naturalists, led by Judy Payne, organized and staffedan MPF and Grow Native! booth at the Kansas City Metro Lawn & Garden Show. Four MPF boardmembers gave presentations or staffed booths at events: President Jon Wingo, to the EasternBeekeepers Association; Vice President Doris Sherrick, to employees of MRI Global in Kansas City;Board Member Dale Blevins at the Independence, MO Green Living Expo; and Emeritus BoardMember Bill Davit at the East Central College Earth Day event.MPF Executive Director Carol Davit gave a presentation to the Washington UniversityWomen’s Club, and had booths at the Western Nursery and Landscape Association; at KirkwoodEarth Day, with Grow Native! Committee Member Bill Ruppert, volunteers and MPF members Billand Joyce Davit, and Jane Schaefer, who administers MPF’s membership database; at WholeFoods Market® on Brentwood in St. Louis; at the Monsanto Employees Earth Day with MPF memberand volunteer Lee Phillion; at LUSH Fresh Cosmetics in the Galleria mall with Jane Schaefer, MPFmember and volunteer Caroline Sant, and Grow Native! Committee Chair Carrie Coyne; and atthe Maritz Corporation Green Vendor Fair, with Mike Arduser.Numerous events are scheduled for later this summer and fall, including the Prairies &Pollinators MPF Benefit on June 26 in Kansas City and MPF’s Annual Dinner Benefit featuringDr. Peter Raven, president emeritus of the Missouri Botanical Garden, on August 23 in Springfield.Details on these and other events are listed on the back cover. We hope to see you there, and wewelcome your participation in MPF’s 50th Anniversary Campaign, which we are launching thissummer. You are the reason MPF has accomplished so much, and your help will be critical to thenext 50 years.– Carol Davit, executive director and Missouri Prairie Journal editor4 Missouri Prairie Journal Vol. 35 No. 2

Prairie ResearchGolden Prairie Botanical ReportAt the end of 2013, the Institute forBotanical Training (IBT) completed its43-page Golden Prairie Floristic IntegrityReport, the result of 2013 field work andanalysis conducted by Justin Thomas ofIBT. Funded by MPF, the report quantifiesthe floristic richness, diversity, evenness,dominance, Native C-value, andFloristic Quality Index mean at GoldenPrairie, as well as provides baseline datafor monitoring the vegetation at GoldenPrairie. A PDF of the report is available atwww.moprairie.org/Prairie-Research/.To date in 2014, a contractor and MPF’s Prairie Operations Manager Richard Datema have cleared90 acres of small trees/heavy brush from MPF’s 376-acre Stilwell Prairie. Above are three views ofthe work (left, before; right, after): Top, looking west toward Kansas. This area of prairie includesMead’s milkweed. Middle, looking east/northeast, large brush areas have been removed and manytrees girdled. The bottomland shown here contains some extensive areas of prairie cordgrass.Bottom, looking north of the previous view.MPF Acquires Land in JoplinWith funding from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, in early May, MPF acquired a newproperty: 8.1 acres within the City of Joplin, which MPF will reconstruct to native prairiespecies. After five years, MPF will convey the land to the City of Joplin, which will make theland part of its park system.“The Service is delighted to work with partners like the Missouri Prairie Foundation andthe City of Joplin to provide the public with a prairie experience within the city limits ofJoplin,” said Scott Hamilton, biologist with the Fish and Wildlife Service. “It is our mission towork with others to conserve, protect, and enhance fish, wildlife, plants, and their habitatsfor the continuing benefit of the American people.”MPF is honored to take on this work, which will increase the biodiversity of the areaand create additional natural space for the people of Joplin to enjoy. Tony Robyn, City ofJoplin recovery planner, stated, “In our post-2011 disaster recovery planning, the citizensexpressed an interest in developing more recreational opportunities and we view this as adynamic, value-added enhancement to nurture a healthy and diverse community.”photos by Scott LenharthThis rush, Juncus brachyphyllus, had beenlisted as a state historic species until JustinThomas of the Institute for Botanical Trainingdiscovered it at Golden Prairie in 2013.Many thanks to Jeff and Hallie Sale of VintonSupply Company of Springfield, MO for donatingfour backpack sprayers to MPF, valued at$376. The sprayers will be used to spot sprayinvasive species on MPF prairies. Thank you,Jeff and Hallie Sale, for your generosity!From left, Vinton Supply Company employeeJean Rudd, and owners Jeff and Hallie Salewith the four backpack sprayers the Salesdonated to MPF early in 2014.Justin ThomasRichard Datema6 Missouri Prairie Journal Vol. 35 No. 2

Shown here, at 40X magnification, are bluemycorrhizae (AMF) on square plant root cells,from plants collected on dolomite glades. Thestructures inside the cells are the arbuscules,formed by the AMF, where AMF exchangesresources with the plant.Justin ThomasMycorrhizal Researchon MPF PrairiesAlice Tipton, a graduate student at theUniversity of Missouri-Columbia, willconduct research at multiple MPF sitesin 2014 as part of a large Missouri grasslandmycorrhizal study. Mycorrhizalinteractions are relationships betweenfungi and plants in which the fungi providethe plant with nutrients and waterin exchange for some of the plant’scarbon resources.These relationships are ancient,dating back to the first land plants onearth. More than 80 percent of landplants make mycorrhizal relationships with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF),which are also the most common mycorrhizal fungi associating with prairie plants.Some prairie plants cannot grow without AMF. Surveys in other grasslands haveshown that AMF diversity is strongly associated with plant diversity, and that agriculturaldisturbances and invasive plant species can alter AMF communities belowground.Tipton will be working at MPF’s La Petite Gemme Prairie, Stilwell Prairie,Schwartz Prairie, and many other prairie and glade sites across southern Missouri. Thesurvey will examine the diversity and richness of AMF taxa living on plant roots inrestored and remnant glades and prairies of different land use histories and soil types.Tipton will genetically sequence AMF DNA and use these sequences to identify differenttaxa of AMF living in and on grassland plant roots.This research will help identify whether current grassland restoration practicesare restoring the community of AMF needed by native plants, and whether it maybe helpful to begin implementing soil microbial restoration in Missouri grasslands.Tipton’s research is funded through the Missouri Department of Conservation’sWildlife Diversity Fund.Burns & McDonnell Hosts MPFBoard MeetingThe engineering firm Burns &McDonnell hosted the April 12, 2014MPF board of directors meeting anda tour for members of the stormwatermanagement features on the grounds ofits world headquarters in Kansas City.Many thanks to Burns & McDonnellRestoration Biologists Randy Root andDennis Haag for making arrangementsfor the meeting and for leading the tour.From left are Dennis Haag, Gordon Shaw, andRandy Root of Burns & McDonnell, who led thetour of the engineering firm’s numerous nativerain gardens and other features designed toslow and filter stormwater runoff.Carol DavitCarol DavitA large number of shrubsand trees supplied by ForrestKeeling Nursery was a newfeature this year.Jill EricksonMPF Kansas City Plant Sale a Phenomenal SuccessMany thanks to the dedication and hard work of the 35 volunteers and native plant vendors whocontributed to the breaking of yet another sales record for the annual MPF April native plant sale at theCity Market in Kansas City on April 19 and 26.With sales of native wildflowers, grasses, vines, shrubs, and trees supplied by Missouri WildflowersNursery, Forrest Keeling Nursery, and Applied Ecological Services, MPF netted more than $11,000 duringthe two very busy Saturday mornings. The funds will be allocated for MPF’s prairie conservation work.Special thanks to Doris and Bob Sherrick, who have spearheaded the sale for many years, and BillFessler, who is the Sherricks’ apprentice for heading up future plant sales. Other volunteers who put inmany hours at the sales were Susan Appel, Darlene Arnett, Barbara Baker, Ronny Berry, Dale Blevins,Paula Diaz, Jill Erickson, Spencer Ernst, Margo Farnsworth, Dennis Gredell, Bob Hansen, JamesHart, Vicky Hart, Dan Haus, Deb Haus, Gary House, Jamie Jepson, Lance Jessee, Linda Lehrbaum,Sid Lehrbaum, Glenn Longworth, Steve Mann, Holly Mehl, Jim Pascoe, Diane Rush, MartySchuettpelz, Sandy Slusher, Bonnie Teel, Jim Wells, Van Wiskur, Lori Wohlschlager, and Joan Zeller.Vol. 35 No. 2 Missouri Prairie Journal 7

thanniversarycampaignForeverPrairies Now andMissouri was once blanketed with 15 million acres of tallgrass prairie,covering one-third of the state. Much of the state also harboredprairie species in open woodlands, savannas, and glades. Thesenative grasslands are a vital part of Missouri’s biological heritage.Today less than one percent of original native prairie remains,in fewer than 90,000 scattered acres. Many of these remnants areunder constant threat of land conversion.Whether for the birds that nest under cover of the tall grass,the many species both above and below ground that can be foundnowhere else on earth, or the memories of early pioneers seekingnew opportunities, our remaining prairies define the richness ofour past and the promise for our future, and must be protected forfuture generations.Through increased prairie conservation, restoration, andoutreach, the Missouri Prairie Foundation will protect morepollinators and other wildlife, clean more water, sequester morecarbon, and bring more beauty home in the landscaping of ourcommunities. For nearly 50 years, the Missouri Prairie Foundationhas been honoring our prairie heritage, protecting prairies for ourgrandchildren, and encouraging the use of native plants.Nearly 50 years ago, the founders of the Missouri PrairieFoundation took a stand to ensure that Missouri will always haverich, beautiful prairies. As its 50th Anniversary approaches, theMissouri Prairie Foundation presents all prairie enthusiasts andlovers of native landscapes with a golden opportunity to invest infuture prairie protection by contributing to the Missouri PrairieFoundation’s 50th Anniversary Campaign.8 Missouri Prairie Journal Vol. 35 No. 2

Campaign Goal—$4 million in gifts and pledgesThis campaign fundraising goal will enable the Missouri Prairie Foundation (MPF)to purchase more land, steward it carefully, and increase and sustain the staffingnecessary to continue building support for prairie and native plants.How MPF Will AllocateCampaign Funds$1 million for annual operating expenses from 2014 to 2016$1 million for new land acquisitions, so MPF is financiallyprepared to act promptly to save a prairie parcel from beingplowed under. While MPF has recently received funds thatare being used to acquire prairie parcels, it is vital that MPF’sAcquisition Fund, with a current balance of just $32,000,continue to receive funds so MPF is prepared to acquireprairies when they become available.$1 million for MPF’s Stewardship Fund, to provide a securesource of funding for future prairie stewardship expenses.$1 million for MPF’s Permanent Endowment Fund, toprovide a permanent source of funds for non-stewardshipoperating expenses.www.HenryDomke.comMDCMPF’s Schwartz Prairie/www.HenryDomke.com50th Anniversary CampaignFunds Received, Awarded, orPledged To DateSeveral recent generous gifts, pledges, grants, and awards,including those listed below, are moving MPF toward itscampaign goal:$750,000 Award for Prairie Acquisition in Jasper and NewtonCounties from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and theMissouri Department of Natural Resources$555,266 from the Estate of Ms. Linden Trial, for prairieacquisition, stewardship, outreach, education, and research$162,495 Award for Land Acquisition and Restoration in theCity of Joplin from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service andthe Missouri Department of Natural Resources$100,000 Grant from the Robert J. Trulaske, Jr. FamilyFoundation, for prairie acquisition$79,143 from the Joseph C. Koster Revocable Trust, for areaof greatest need$50,000 pledged from Mr. Rudi Roeslein, for area of greatestneed$30,000 from Dr. Clifford Welsch, and an additional $90,000pledged, for prairie acquisition$16,840 from LUSH Fresh Handmade Cosmetics, to helpunderwrite 2014 Missouri Prairie Journal expensesHow You Can Help MPFReach Its 50th AnniversaryCampaign GoalMPF has established Prairie Champion and Prairie Patrongiving opportunities for individuals, businesses, philanthropicfoundations, and others with the means to give cash orsecurities at the following levels:Prairies Now and Forever Champion $1 Million or MoreBig Bluestem Champion $500,000 or MorePrairie-Chicken Champion $250,000 or MoreSunflower Champion $100,000 or MoreMonarch Champion $50,000 or MoreBlazingstar Champion $25,000 or MoreGold Patron $10,000 or MoreSilver Patron $5,000 or MoreM. J. Hatfieldwww.HenryDomke.comVol. 35 No. 2 Missouri Prairie Journal 9

Putting Your Donation to WorkBelow are examples of the ways your gift can make a difference.With a $1 million gift,• MPF could purchase several hundred acres of native prairie• or protect and steward its 2,600 acres of native andrestored prairie for about five years• or protect and steward about 700 acres of prairie inperpetuity• or meet its $1 million permanent endowment goal duringthis campaignWith a $500,000 gift,• MPF could purchase 150 to 300 acres of native prairie• or protect and steward its 2,600 acres of native andrestored prairie for more than two and a half years• or protect and steward about 300 acres of prairie inperpetuity• or meet half of its $1 million permanent endowment goalWith a $250,000 gift,• MPF could purchase roughly 100 acres of native prairie• or protect and steward its 2,600 acres of native andrestored prairie for about 15 months• or protect and steward about 150 acres of prairie inperpetuity• or meet one quarter of its $1 million permanentendowment goalWith a $100,000 gift,• MPF could fund the production of the Missouri PrairieJournal for more than three years• or fund production of the Missouri Prairie Journal, otheroutreach and education activities, and its Grow Native!program for one yearCampaign Membership GoalsYour annual membership dues are critical to the operation ofMPF. MPF is grateful to all members, at each level, for joiningand sustaining their memberships.To broaden its membership support, which will increaseMPF’s prairie protection capacity and also strengthenthe collective voice for prairie conservation, MPF hasestablished the following membership goals to reach by 2016:• Grow membership to 2,000 or more by 2016. As of May 2014,MPF membership is at 1,650 individuals/families/groups. TheMPF goal is to attract and sustain at least 350 new members atthe regular to sustaining member levels ($35 to $500) by 2016.• Welcome 50 or more new lifetime members by 2016. A giftof $1,000 or more (lump sum; cash or securities) entitles anAllen Woodliffe• or protect and steward its 2,600 acres of native andrestored prairie for about nine months• or protect and steward about 60 acres of prairie inperpetuityWith a $50,000 gift,• MPF could protect and steward its 2,600 acres of nativeand restored prairie for about four and a half months• or protect and steward about 30 acres of prairie inperpetuityWith a $25,000 gift,• approximately 7.5% of MPF’s annual operating budgetwould be metGifts at the $1 million, $500,000, $250,000, $100,000,$50,000, or $25,000 levels can be designated to any of severalMPF funds to address particular conservation interests to thedonor.A $10,000 or a $5,000 gift• will help fund MPF’s annual operating budget, includingstewardship, outreach, and education costsEach contribution moves MPF closer tofulfilling its campaign goals, and each donor isan honored supporter. Gifts or pledges may be lumpsums or annual amounts. Prairie Champions andPrairie Patrons receive significant recognition and agenerous package of amenities. For more information,please call 573-356-7828, email info@moprairie.com,or see the Donate page at www.moprairie.org.individual, family, or organization to lifetime membershipin MPF and complimentary admittance for two to the MPFAnnual Dinner. With 50 or more new lifetime members, MPFwill have more than 150 total lifetime members.• Recognize 30 or more lifetime members as Crawford &Christisen Compass Society Members in 2014, in 2015, and in2016. Lifetime members who make an annual gift of $1,000or more (cumulative or lump sum in a calendar year) aremembers (year gift is made) of the Crawford & ChristisenCompass Society and invited to the annual Society dinner. TheSociety is named for MPF’s co-founders Bill Crawford and DonChristisen, who set the direction for MPF’s permanent prairieprotection.Bruce SchuetteChristine Torlina10 Missouri Prairie Journal Vol. 35 No. 2

MDCHow to Make A Campaign Gift of Cash or SecuritiesTo make a tax-deductible, 50th Anniversary FundraisingCampaign gift of cash, please send a check toMissouri Prairie Foundation50th Anniversary CampaignCommunity Foundation of the OzarksP.O. Box 8960Springfield, MO 65801Phil KoenigCarol DavitIf you are making a tax-deductible campaign gift of securities,please contact MPF at 888-843-6739 or view the Donate page atwww.moprairie.org.Brian EdmondBruce SchuetteAs the Treasurer of the Missouri Prairie Foundation, I am in a unique position toevaluate the organization’s fiscal strengths and weaknesses. The past five years havebeen tremendous for MPF in terms of opportunities for growth: prairies have beenadded, Grow Native! was acquired, funding sources have been strengthened anddiversified. The establishment of a control environment to ensure MPF’s continuedexpansion and success has been embraced by MPF’s Board of Directors and implementedthroughout the organization by our staff. MPF’s Executive Director, CarolDavit, has been a driving force in these efforts. I believe that under Carol’s directionthe organization has the opportunity to continue to expand dynamically, and withcomplete fiscal responsibility. For these reasons, I felt comfortable investing in MPFby becoming a life member.—Laura Church, Missouri Prairie Foundation TreasurerI have pledged the contribution of $50,000 to MPF because I believe it is a lean,effective, and passionate voice for the restoration and preservation of an extremelyimportant ecosystem that may vanish in our lifetime. Without MPF’s constant vigilance,promotion, and making people aware of the ecological, environmental, andsocial impacts of the loss of this valuable part of our heritage we will certainly losethe remaining few tracts of prairie. Not until I joined MPF and participated in thegrassland vs. cropland debate did I realize the significant role that our prairies playin clean water, soil erosion and health, flooding, CO 2sequestration, wildlife habitat,pollinators, and so many other ecological services that are yet to be fully appreciated.This is a cause to which I have dedicated not only money, but also a significant partof my time and business efforts in order to help restore our native prairie to its rightfuland prominent role in a healthy and vibrant environment. I hope you will joinme in this noble and important cause.—Rudi Roeslein, CEO, Roeslein and AssociatesI’ve always loved the Missouri countryside. But it was not until my sister Linden’sdeath in 2012, and her bequest to the Missouri Prairie Foundation, that I began totruly appreciate the Missouri prairie. I’ve also come to appreciate the people in theMissouri Prairie Foundation, their enthusiasm for saving and restoring Missouriprairie, their knowledge,Foreverand their willingness to volunteer their time and expertiseto this great cause. I’m thrilled that my sister’s bequest has become part of the MPF’s50th anniversary campaign. She was a modest, unassuming person, and in manyrespects the Missouri prairie mirrors her spirit.—Mike Trial, Missouri Prairie Foundation MemberPrairies Now andVol. 35 No. 2 Missouri Prairie Journal 11

FromGrassland RestorationtoRenewable EnergyHow MPF Planted Seeds for aLarge Sustainable Energy InitiativeBy Sheldon RipsonSome ideas come out of the blue. But an idea taking shapein the hog barns and rolling hills of northern Missouricame out of the green—the grasslands revered by an entrepreneur,industrialist, and dedicated conservationist. MissouriPrairie Foundation (MPF) technical advisor Rudi Roeslein lovesnative prairie for its beauty and unique set of ecological services.Now Roeslein is staking his reputation on an ambitious goal ofreturning 30 million acres of highly erodible land to native grasslandsin 30 years.Roeslein’s business intuition tells him the only way that canhappen is by creating an economic model for landowners toplant native grasses. And that is exactly what he intends to do.“We hope to come up with another crop for farmers: thenatural prairie grasses that have grown here for thousands ofyears,” Roeslein said. “I’m not saying this is a silver bullet. Butthis is a potential solution for challenges like protecting waterquality, preventing soil erosion, safeguarding pollinator services,and increasing wildlife habitat. If there is an economic value forthese ecological services, it will be a better source of income thanplanting crops in areas where they are not sustainable.”Major Northern Missouri ProjectEarly in 2014 Roeslein’s company,Roeslein Alternative Energy, announceda $100 million renewable energy initiativewith Murphy-Brown of Missouri(MBM). MBM and its parent companySmithfield Foods, the world’s largest hogproducer, own nearly 50,000 acres innorthern Missouri.“I’m really encouraged by this project,”said Brian Paulsen, MBM Directorof Environmental Health and Safety.“I’m excited by Rudi, the team he’sput together, and the model he’s puttogether. He’s got the front side figuredout and the back side. No one else hasdone that. This will be good for northMissouri, good for the environment,good for everyone.”Top, a prairie planting at Murphy-Brown ofMissouri, initiated in 2008 thanks to a partnershipof the Missouri Prairie Foundation, theMissouri Department of Conservation, theU.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the NaturalResources Conservation Service.12 Missouri Prairie Journal Vol. 35 No. 2

Frank OberleRAEThe Key: Anaerobic DigestionAt the heart of the process is anaerobicdigestion (AD). In the absence of oxygen,naturally occurring microorganismsextract methane from animal manureand organic matter. Rather than sit in anopen lagoon, the waste is moved into acovered lagoon or tank. The microorganismscreate biogas, which rises to the topof the digester. The biogas is collectedand cleaned of impurities like sulfur.What remains is the same molecule asnatural gas (98 percent methane, alsoknown as biomethane), which can becompressed (CNG) or liquefied (LNG)for use as transportation fuel and/orinjected in the U.S. natural gas grid system.The residue can be used as naturalfertilizer, and the water can be safelyused for irrigation. Odor emissions arereduced by 98 percent.The 2013 edition of Biogas: AnAll-Rounder noted that “using liquid orsolid manure from livestock in a biogasplant is particularly good for the climate.It constitutes a pre-processing step as itmakes the livestock manure more tolerablefor plants and reduces methaneemissions during storage and spreadingon fields and pastures. The neighborhoodalso gains an added bonus, sincethe odor emissions when spreadingfermented products are considerablylower than with conventional slurry.”Roeslein seeks to harness AD ina large-scale way. Barn scrapers willmove waste from approximately 1.5million hogs into nearly 100 existinglagoons fitted with impermeable covers.Methane production could begin latein 2014. When completed, CNGproduction could approach 20 milliongallons annually.“If you really look at animalmanure, it’s a waste byproduct ofplant material. There is carbon valuethere. We will harvest the carbon usinganaerobic digestion. Then we’ll take theremaining sludge and put it into the soilas a valuable nutrient. The N, P, and Kare still there. The digester captured thevalue,” Paulsen said.Injecting digested manure intosoil provides about one metric ton inbenefits per acre per year thanks tocarbon dioxide stored in the soil fromthe manure (0.8 metric ton) and lowernitrous oxide emissions (0.2 metricton). Nitrogen in synthetic fertilizer orundigested manure volatizes to releasenitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas about298 times more potent than carbonVol. 35 No. 2 Missouri Prairie Journal 13

Prescribed burning of one of the prairie plantings at Murphy-Brown of Missouri, and on facingpage, the initial winter seeding of prairie plants on the property in 2008.dioxide. Methane that reaches the atmosphereis 20 times more destructive thancarbon dioxide.MBM officials say the project willlower production costs, increase efficiency,and help surrounding communities.“There will be significant benefitsto the environment from theselagoon covers. We’ll reduce our carbonfootprint. We’ll reduce our landapplication efforts,” said Bill Homann,MBM Director of Administration andCompliance. “We are clearly aligningourselves with a project our parent companywill strongly support.”Native Grassesas a New Energy CropNext Roeslein envisions using biogasharvested from restored native grasslandsto produce more Renewable NaturalGas (RNG). Germany in 2012 had7,600 AD systems using energy crops togenerate biogas. The industry accountsfor 41,000 jobs and 6.5 billion Euros insales. MBM officials have identified landnear waterways where grass could beplanted as buffers, harvested, and addedto digesters to produce biogas.“We said we’d work with him onthat, but it’s in the infant stage,” Paulsensaid. “We’ve got several thousand acresup here and some could be called unproductive.What could be done to makeit productive? Would it be better to useanother kind of grass here?”“If we can improve the output withthe same asset base by adding prairiegrasses to the manure maybe we’ll getanother 20, 50, or even 100 percentoutput,” Roeslein said. “In addition tobeing bullet-proof environmentally weare increasing asset value by utilizingland differently. Hopefully this will be amodel for other farmers.”Roeslein’s Introduction to PrairieRoeslein bought the first of his threefarms in 1992 shortly after startingRoeslein & Associates, the St. Louisbasedengineering, modular fabrication,and construction services firm. An avidoutdoorsman, Roeslein started plantingnative grasses after noticing large deerwhile hunting on the Kansas prairie. Hereasoned the deer got large by eatingdeep-rooted native forbs and legumes,which can extract water and nutrientsnon-native plants can’t reach. Wildlifephotographer and MPF partner FrankOberle provided native grass seed forRoeslein’s farms. Oberle introducedRoeslein to MPF past president SteveMowry, who later suggested thatRoeslein serve on the MPF board.Roeslein began thinking aboutusing plant life for biofuel while conductinga controlled burn on his farm.Derrick Poeslein“There was a tremendous amount ofenergy being released. So I wondered ifthere was a way to harness this. That waskind of the spark,” Roeslein said.MPF, Mowry, and Oberle encouragedPremium Standard Farms (the predecessorcompany of MBM) to begin aproject in 2008 that included 400 acresof grassland restoration. The MissouriDepartment of Conservation and theU.S. Fish and Wildlife Service consultedand offered technical support. Thanksto funding from the Natural ResourcesConservation Service’s WHIP program,today the prairie restoration is robustwith high numbers of wildflower species,a large volume of native grass, andincreased wildlife in the prairie habitat.“There’s no better example in thestate of how to emulate an ecosystemon 400 acres in a short period of time.That was the beginning of a philosophicalchange on how to get diverse plantuse. MPF was able to prove we can planthigh quality grasslands very easily,”Oberle said.Roeslein was on the MPF boardduring discussions about environmentalchallenges for the project after heavyrains filled nearby livestock lagoons.Roeslein wondered whether anaerobicdigestion could help those kinds ofproblems while also providing a sourceof renewable energy, so he arranged tomeet with Premium Standard Farms.“When he learned about the situation,Rudi had the cogs working thewhole time thinking about taking anecological difficulty and making everyonecome out better,” Mowry said.“Steve and I went with Rudi for thepresentation. He said we’ll take all themanure you can give us and we’ll make apositive outcome,” Oberle said.Roeslein credits the meeting forallowing the project to begin. It starteda two-year collaborative effort leading tothe joint venture. Roeslein Alternative14 Missouri Prairie Journal Vol. 35 No. 2

Energy will own the natural gas from theproject and MBM will retain the rightsto the compost material that is the otherby-product of anaerobic digestion.“We had experimented with impermeablelagoon covers, which wouldn’tallow rainfall to accumulate. We werejust flaring off the gas. Then Rudi andhis team started talking about using thecovered lagoons like digesters that couldcapture the gas. Rudi brought in somefolks to really look at ways to utilize thatgas profitably,” Homann said.“At the time everyone in the renewableenergy industry was focusing onethanol and using biomass from energycrops like corn, corn stover, or nonnativegiant miscanthus to producemore ethanol from second-generationprocesses that were still not proven technology,”Roeslein said. “My concernwas they were focusing on biomass yieldand not ecological services. No one wastalking about what would happen fromconverting additional marginal land intobiomass production, like ConservationReserve Program lands, without consideringecological services and wildlifehabitat.”Obstacles and OpportunityRoeslein’s business model seeks to tapinto the natural gas boom. There isa growing market for diesel-poweredvehicles converting to natural gas, whichis less expensive and burns 90 percentcleaner than diesel. Roeslein AlternativeEnergy is actively engaged with largecustomers interested in converting fleetsto CNG or LNG. Many find the sustainabilityof RNG attractive and theprice advantage compelling.“It will take time for truckers andfleets to get comfortable that they canhave access to the gas at convenient locations,that it’s not a fad, or that the pricesare not going to change to eliminate thefinancial advantage. Eventually, becauseFrank Oberleof high natural gas supplies and its popularityaround the world, it will be widelyadopted in the U.S.,” Roeslein said.Roeslein also knows it will take timeand examples of success to restore highlyerodible crop ground to native grasslands.He is collaborating with conservationexperts to develop best practices.Missouri Department of ConservationPrivate Land Conservationist JohnMurphy developed and helped implementa comprehensive management planon Roeslein’s Putman County farm.“We saw a lot of potential in seedingerodible acreage and restoring existingremnants, and Rudi and his sonDerrick immediately began workinghard. Seeing the project six years later,it has far exceeded my expectations,”Murphy said. One of the experimentsinvolves converting highly erodible landto native grasses for RNG production.“Currently, the closest analog tothat is hay production for financial gain.When there are financial incentives forhay ground, people do that today. Thisis not some great leap into an unfamiliararea,” Murphy said.Chris Woodson of the U.S. Fishand Wildlife Service in Columbia, MOapplauds efforts to use grassland as biomassfor energy, provided it is well managed.“If it is harvested 100 percent everyyear down to nothing that really is nodifferent than grazing non-native coolseasonfescue down to nothing everyyear. It does more harm than benefit.Rudi is promoting a percentage of it tobe harvested every year, 30 to 50 percent.That’s good because these systemsneed it,” Woodson said.Roeslein believes action is urgent forland stewardship, using waste as energy,and realizing that human actions affectthe entire planet’s species.“We are going from seven billionto nine billion people in the next 50years possibly. The decisions we makeright now are going to have a dramaticimpact,” Roeslein said. “I don’t foreseethat in the next couple years we’ll haveall the solutions. But I’m prepared towalk the long crooked path and see itto fruition. Aldo Leopold promoted theethos that land is a living organism thatshould be treated with respect and notas a disposable commodity. ‘A thing isright if it tends to preserve the integrity,stability and beauty of a biome. It iswrong if it tends otherwise.’ I believethis mission is right.”Sheldon Ripson is a veteran electronicjournalist and media executive basedin St. Louis. He presently operates RSCommunications, a strategic communicationsconsulting firm for businesses andnon-profit organizations.Vol. 35 No. 2 Missouri Prairie Journal 15

Prairie InvertebratesInvertebrates: the little things that run the world –E.O. WilsonPrairie Odonates Dragonflies and Damselflies of our GrasslandsOdonate images by ©Richard Day/Daybreak ImageryAn Interview with Richard DayIn 2013, the Missouri PrairieFoundation (MPF) contracted asurvey of dragonflies and damselflies(also referred to as “Odonates”)from nine MPF upland prairies andone bottomland prairie owned byThe Nature Conservancy (TNC).Photographer and entomologistRichard Day conducted the survey, thefunding of which was made possiblethrough the bequest from Ms. LindenTrial to MPF in 2012 and 2013.Ms. Trial was an entomologistspecializing in dragonflies anddamselflies with the MissouriDepartment of Conservation from1972 until her retirement in 1999.An avid field researcher, Ms. Trialdiscovered the rare Hine’s emeralddragonfly in Reynolds County, MO in1999. Her contributions to dragonflydata are widely used in both state andnational conservation projects.In the interview below, Daydiscusses the results of his 2013survey and shares information aboutdragonfly and damselfly ecology.—Carol Davit, EditorMDC/Cliff WhiteYou recorded a total of 35 dragonfliesand damselflies during the survey of10 tracts of land owned by MPF andTNC. Is this high, or low, for uplandprairies, and why?I would say it’s about normal or slightlylow. There was very little water onthese tracts, which of course determinespopulation. When water was present, itwas in ponds, which probably had fishin them and would keep the dragonflylarvae population lower than fishless,shallow prairie potholes.What is the total number of Odonatespecies in the entire tallgrass prairieregion?My personal perspective would be fewerthan 50 to 70 depending on habitat,location, and water.Does habitat fragmentationimpact upland grassland Odonatepopulations, or is the limiting factoravailable fresh water?Water.What do Odonates eat?Any insects including other dragonfliesor damselflies. A dragonfly can consume15 to 18 percent or more of its ownbody weight a day.What eats Odonates?Frogs, spiders, and birds are some of thetop predators. Purple martins are voraciouspredators of dragonfly populationsand also other birds in the swallow family,such as tree swallows.Are some Odonate species more, orless, tolerant of poor water quality?Odonata larvae can be very sensitiveto water-related issues. Pollution fromdevelopment and agriculture is a threat.Animal waste from farms and ranchescan threaten an ecosystem if not managedproperly. Mismanaged pastures andstorage facilities are ongoing concerns.Overgrazing exposes soils and makesthem more vulnerable to erosion andinvasion of undesirable plants. Whenlivestock graze and trample vegetation,Linden Trial conducting fieldwork; above, a blue dasher (Pachydiplax longipennis).16 Missouri Prairie Journal Vol. 35 No. 2

Top, the pond at Penn-Sylvania Prairie provides habitat for larvae of Odonates and other aquatic macroinvertebrates. Above, at left, is an easternforktail (Ischnura verticalis) at Schwartz Prairie, and at right, a jade clubtail (Arigomphus submedianus) at Marmaton River Bottoms Wet Prairie.Vol. 35 No. 2 Missouri Prairie Journal 17

Prairie InvertebratesInvertebrates: the little things that run the world –E.O. WilsonA female banded pennant (Celithemis fasciata) at Penn-Sylvania Prairie.they can reduce diversity and preventthe regeneration of native plants.Cropland produces more erosionand sedimentation than any othersource, because of the repeated exposureof large expanses of bare soil. Erosionby water and wind can be severe whensoil is not protected by vegetation.Sediment from erosion threatens someof our nation’s most vital watersheds,and together with nutrients and toxins,can degrade our rivers, streams, ponds,and lakes, making them inhospitable foraquatic life.What specific grassland habitatshave the greatest species diversity ofOdonates? Where would you expectto find the most?The habitat that includes fishless wetlandsor streams flowing through them.Perennial streams are not as productive.There is much to be learned aboutOdonates, such as how many speciesare in decline, and from which specificnatural community types. Currently,researchers don’t have all the answers,which demonstrates how important it isfor us to continue conducting researchon Odonates!”Richard Day has been photographingprofessionally for 30 years. In theearly 2000s, a job he had photographingdragonflies developed his interestin these insects, and he spent the nextseveral years learning about them withDr. Tim Cashatt from the IllinoisState Museum. Day went on to conductseveral presence/absence surveysfrom 2006 to 2012 for the IllinoisDepartment of Natural Resources insouth-central Illinois. Day has alsobeen involved in surveying and a mark/recapture study in Missouri for the federallyendangered Hine’s Emerald from2007 to present, and has also workedon projects for the Hine’s Emerald inIllinois in 2010-2011 and 2013 and2014.Natural Historyof the OrderOdonataThe Class Insecta is the largest class oforganisms and accounts for more than 75percent of all animal species. The OrderOdonata is one of 31 orders of insectsand is the one to which dragonflies anddamselflies belong. “Odonates” is the termoften used to refer to both dragonfliesand damselflies. There are two sub-orders:Anisoptera (Dragonflies) and Zygoptera(Damselflies). Odonata is a word derivedfrom odonto- meaning tooth, which refersto the strong teeth found in most adults.The main difference betweendragonflies and damselflies is thatdragonfly wings are outstretched at alltimes. Damselflies fold their wings backalong their abdomens when resting.An exception is the family Lestidae(Spreadwings), which rest with their wingspartly outspread. Damselflies are alsousually much smaller and more delicatethan dragonflies—most are between aninch or two in length.Odonates live as aquatic insectsbefore maturing into flying insects.Weather changes influence how longdragonflies live. Most species in Missouricomplete their life cycles in one year. Afew, especially those species that lay theireggs in temporary water, mature quicklyand emerge as adults in less than a year, aslong as the weather is warm.Some larger species may need morethan 12 months to mature before theyemerge from the water. Those that live instreams without any flow during portionsof the year also may take longer.Odonates are predators, both whenimmature in the water and as adults on the18 Missouri Prairie Journal Vol. 35 No. 2

wing. Adults catch and eat their food asthey fly. Only occasionally do they need toland to eat. Usually they eat small insects,but sometimes you can see them catch abutterfly or a cicada.Immature Odonates, as do all insects,shed their skin as they grow larger. Whenthey are ready to transform into adults,they climb above the water beforebreaking out of that last skin. Some willclimb up plant stems; you may find theskins they leave behind on cattails or otherplants.Some stream-dwelling Odonatesmay crawl out onto tree branches or othervegetation before they emerge as adults.Some species transform into adults ongravel or sand bars near the water’s edge.Newly emerged adults need timeto inflate their wings so they can hardenenough to fly. Just after emerging, anadult dragonfly is extremely vulnerable.Predators, including insect-eating birds,consume many of them, leaving behindnothing but their bright shiny wings.At least 65 species of dragonflies livein Missouri. A determined search of theAbove left is the pond at Golden Prairie; at right is a male spangled skimmer (Libellula cyanea) and belowis a male calico pennant (Celithemis elisa). Both species were photographed at Penn-Sylvania Prairie.state will likely uncover more species.Many common dragonflies live throughoutthe state, but a few species are restrictedto only parts of Missouri. The Ozarksregion contains the most species. Thespecialized habitats there also support agreater variety of species. In addition, moredragonfly surveys have been conducted inthis region than elsewhere in the state.—information from “Pond Dragons,”by Linden Trial published in theMissouri Conservationist, July 2000, andfrom Richard DayPrairie Odonate Survey ResultsBetween June 2 and August 12, 2013,Richard Day surveyed nine MPF tractsof land and one owned by TNC. Surveyswere conducted between the hoursof 7:00 a.m. and 7:30 p.m. by randomwalks in these tracts. Day collectedOdonates with an aerial insect net.After collection, Day preserved thespecimens and sent them to the EnnsEntomology Museum at the Universityof Missouri where they are housed.Day’s survey yielded a total of35 Odonate species from all sites.Numbers of species by prairie areas follows: Golden Prairie: 12; Penn-Sylvania Prairie: 19; Coyne Prairie: 8;Welsch Tract: 10; La Petite Gemme: 8;Schwartz Prairie: 19; Stilwell Prairie: 16;Marmaton River Bottoms Wet Prairiepreserve (owned by TNC): 15; Denisonand Lattner Prairies: 15.The full survey report is available atwww.moprairie.org/prairie-research/.Vol. 35 No. 2 Missouri Prairie Journal 19

EdgarA Tribute toW. D enisonBy Carol Davit and Scott WoodburyIn April 2014, the City ofKirkwood, MO, and manyof its residents celebratedthe life and works of one ofits most notable residents:Edgar W. Denison. Anextraordinary man witha wide range of interests,Denison was an amateurnaturalist, botanist, pianist,artist, photographer,woodworker, geologist,paleontologist, teacher, apioneering recycler, andenthusiastic promoter ofnative plant gardening.This beautiful drift of blue-eyed Mary (Collinsia verna) at Shaw Nature Reserve’s WhitmireWildflower Garden originated from a gift of seed from Denison.Scott WoodburyThe Natural HistorianDenison was born in Stuttgart, Germanyin 1904 and immigrated to the UnitedStates in 1927. He spent a lifetimeenjoying wildflowers, first as a student inGermany, then as an amateur botanistleading hikes in Missouri.Denison later became one ofMissouri’s most celebrated wildflowerenthusiasts through his popular fieldguide, Missouri Wildflowers, which haseducated and continues to instructthousands of Missourians about the20 Missouri Prairie Journal Vol. 35 No. 2

Dr. Peter Raven, president emeritus of theMissouri Botanical Garden, provided remarksat the Edgar Denison Tribute Garden dedicationin Kirkwood on April 19. At right, in theMissouri Prairie Foundation’s Grow Native!booth is Grow Native! Committee member BillRuppert, who helped organize the month-longDenison celebration.Kirkwood Mayor Art McDonnell shared theKirkwood City Council Proclamation, whichproclaimed April as Edgar Denison Month.Missouri Botanical Garden Kemper CenterOutdoor Supervisor June Hutson, left, andGrow Native! Committee Member Bill Ruppertunveiled the Edgar Denison Tribute Garden onApril 19.Robert WeaverRobert WeaverRobert WeaverCelebrationThe Edgar DenisonThanks to the inspiration and organization of several residents of Denison’shometown, the City of Kirkwood, Kirkwood Living Green, Shaw NatureReserve, Webster Groves Nature Study Society, and Kirkwood in Bloomhighlighted the life and legacy of Edgar Denison through the month of April 2014.Kirkwood resident Gwyn Wahlmann planted the seed for the idea of a Denisoncelebration. “Twelve years ago a visit to see the spring ephemerals at EmmeneggerNature Park prompted me to buy a wildflower field guide at Powder Valley,” saidWahlmann. A volunteer there said, ‘You know, the guy who wrote this was aKirkwood resident.’ I asked around, and everyone who had known Edgar seemed tohave a charming story to tell. It was clear he was a very special and unique person.“Walter Smith, George Yatskievych, and Scott Woodbury respondedimmediately to the idea of a special Edgar Denison event, and it took some time,but thanks to the efforts of many wonderful people, plans developed into a wholemonth of events celebrating Edgar’s life, values, and interests.”Kirkwood Mayor Art McDonnell proclaimed April as Edgar Denison Month atthe April 3 City Council Meeting.The Edgar Denison Nature Education Series of native plant-related talks andpresentations was organized, presented by noted natural community, native plant,and gardening experts, and hosted by the Kirkwood Public Library. In addition, anexhibit of Denison’s wildflower illustrations was displayed in the Powder ValleyConservation Nature Center through the month.Kirkwood’s celebrated Edgar Denison Day/Earth Day on April 19 at the Farmer’sMarket. In addition to many nature and native plant exhibitors, Mayor McDonnelldedicated an Edgar Denison Tribute Garden, featuring many of Denison’s favoriteplants. The garden, designed by Missouri Botanical Garden Kemper Center OutdoorSupervisor and Kirkwood resident June Hutson, with plants donated from severalnurseries and gardeners, is along the Kirkwood Farmer’s Market Greenway, and is aliving tribute to Edgar Denison.To learn more about Denison, visit the Edgar W. Denison Wikipedia page,newly created thanks to journalist Robert Weaver, with contributions from severalDenison devotees.state’s wildflowers. First published in1972 by the Missouri Department ofConservation, it is now in its sixth editionand remains a best seller.Missouri Prairie Foundation (MPF)members are familiar with DenisonPrairie, the 160-acre original prairie inBarton County whose purchase in 1993was made possible thanks to a generousgift from Denison and his wife Ruth.While he loved prairie, Denison wasinterested in the native plants and naturalhistory of all of Missouri’s naturalcommunities, and through his tirelesswork and ceaseless curiosity, inspiredcountless conservation professionals andnative plant enthusiasts.Denison led native plant hikes,lectured, taught botany, and translatedthe hand-written German script of Dr.George Engelman, a St. Louis physicianand botanist. In addition to beingan MPF member, Denison was activelyinvolved with the Missouri Native PlantSociety and the Webster Groves NatureStudy Society.Denison was recognized for his conservationcontributions, with two awardsfrom the Missouri Native Plant Society,the Erna R. Eisendrath MemorialVol. 35 No. 2 Missouri Prairie Journal 21

Education Award in 1985 and the JulianA. Steyermark Award in 1993, and byinduction into the Missouri Departmentof Conservation Hall of Fame in 1994.The Kirkwoodian andNative GardenerAfter immigrating to the U.S. at the ageof 22, Denison soon settled in Kirkwoodwith his wife, Ruth, an artist and silversmith.Denison’s garden at his homewas a showplace where visitors were welcome.He grew more than 1,000 speciesof plants, often potting extras to set onthe curb for passersby.A modern-day Johnny Appleseed,Denison grew native plants from seedbecause he felt they should not be dug inthe wild (and other conservationists concur!).He maintained a blue-eyed Marypatch in his garden where he could easilycollect seed to give away.From shirt-pockets full of seed,Denison sowed blue-eyed Maryalong Hidden Valley and the RiverTrails at Shaw Nature Reserve and atEmmenegger Nature Park in Kirkwood.He shared seed for countless otherpatches growing at the homes of friendsand neighbors, who were given orsnitched seed from beneath the boughsof the old white oak by his sidewalk onAdams Street.There were several other plants thatDenison passed around St. Louis; plantslike rose turtlehead, southern blue flagiris, and New England aster, to name afew. They were usually given with theappropriate pedigree to a good homeand with strict planting instructions.Denison once dug up a gift tree at aEdgar Denison giving a tour of his garden toShaw Nature Reserve volunteers in 1992.neighbor’s to see if it had been plantedcorrectly. It was, and he planted it back,satisfied that his instructions had beenfollowed.Despite all of his volunteer workand explorations of the natural world,Denison did have a professional careeras well. He worked as a cost engineer forUnion Electric for 37 years, retiring in1969.Less than a month after his death in1993 at the age of 88, friends and familygathered at Shaw Nature Reserve to paytribute and share their memories. At thiscelebration of his life, Dr. Peter Raven,now president emeritus of the MissouriBotanical Garden, said in conclusion,“In the glades and prairies and woods ofMissouri, Edgar Denison will always bealive with us teaching, urging, and challengingus to continue to do everythingpossible to enjoy, to cherish, and to preservethe wild things that make this sucha wonderful place to live.”Carol Davit is the executive director of the Missouri Prairie Foundation and editor of theMissouri Prairie Journal. Scott Woodbury is the curator of the Whitmire Wildflower Garden atShaw Nature Reserve, and serves on MPF’s Grow Native! Committee.Scott Woodbury“As a horticulturestudent at Mizzou,Mr. Denison’s plantsharinggenerositywas extremely helpfulto assist our studentefforts to develop theWoodland and FloralGardens behind the Agriculture Building.Back in the late 1970s, herbaceous nativeplants were extremely difficult to find in thenursery trade and he donated such nativewoodland classics as celandine poppy andVirginia bluebells. These and other donatedplants helped to realize the Missouri nativeemphasis of this outdoor learning laboratory.”—Bill Ruppert,National Nursery Products-St. Louis“Edgar’s gardencontained awonderment of plantsthat reflected hiseclectic appreciationof nature. I shallalways treasure thetimes I visited thegarden and listened to all his stories abouteach botanical treasure. I had no idea thatsomeday I would own this garden and becomethe caretaker of such a collection. It is a joy togarden in such a space with its rich historicalconnections.”—June Hutson, Missouri Botanical GardenKemper Center Outdoor Supervisor andcurrent owner of Denison’s homeMBG“It is impossible tothink of Missouriwildflowers withoutalso bringing tomind the late, greatMissouri naturalistand gardener, EdgarDenison. Through hisadvocacy for native plants and their habitats,his generous spirit, and his gift to Missourianseverywhere in the wonderful MissouriWildflowers field guide, Edgar made a lastingimpression on anyone interested in nature inthe state.”—Dr. George Yatskievych,Curator, Director–Flora of Missouri ProjectJefferson PradoAllen Woodliffe22 Missouri Prairie Journal Vol. 35 No. 2

The D enison Prairie Stewardship FundAllen WoodliffeElizabeth McIntyreCarol DavitThe Missouri Prairie Foundation (MPF)purchased the 160-acre Denison Prairie in1993, thanks to a generous gift from EdgarDenison and is wife Ruth. Since that time, MPF hasannually controlled woody brush and invasive,herbaceous species on the property. You can helpfulfill MPF’s 50th Anniversary Fundraising Campaignby donating to the Edgar and Ruth Denison PrairieStewardship Fund.The Fund goal is $235,000, which wouldprovide a permanent funding source to enable MPFto protect this prairie long into the future. To makea contribution of cash or securities to this fund,send a check to Missouri Prairie Foundation, c/oMartinsburg Bank, P.O. Box 856, Mexico, MO 65265-0856, and indicate “Denison Fund” on the check.To make a gift of securities please contact MPF at888-843-6739 or view the Donate page at www.moprairie.org.Nearly 300 native plant species are documented from DenisonPrairie, including pale purple coneflower (Echinacea pallida), top,and at far left, blue hearts (Buchnera americana). Denison Prairiewas the site of MPF’s 2013 Prairie BioBlitz, where nature enthusiastsenjoyed tent camping and learned about prairie plants and animalsfrom leaders like ornithologist Dana Ripper.Vol. 35 No. 2 Missouri Prairie Journal 23

Missouri’sNativeAquaticsChose native aquatic plants to landscape lakes and ponds,and for water gardens in pools or containers.Becky EricksonBy Ann WakemanThere is great joy in havinga backyard water garden,for the beauty of the plantsand to observe wildlife thatgathers there. Natural looking,in-ground water gardensand even large ceramicpots or other containers ona patio present additionalways to landscape with andenjoy native plants. Thereare numerous referencesto building a water garden,so this article will focus onaquatic native plants, and myexperience with using them inwater gardens.Water Garden Ecology: A BriefPrimerSubmerged portions of all aquatic plantsprovide habitats for many aquatic invertebrates.These small creatures—such asdragonfly larvae—in turn are prey forfish, amphibians, reptiles, and ducks.After aquatic plants die, their decompositionby bacteria and fungi providesfood, called “detritus” for many aquaticinvertebrates. In addition, waterfowl,game birds, and songbirds will consumeseeds of aquatic plants like soft rush.Emergent vegetation providesperching places for many adult, wingedinsects. Such vegetation is critical aswell for dragonflies, mayflies, and otheraquatic insects because the nymphs crawlup it when they emerge from water tobecome free-flying adults.Richard dayTo jump start your water garden’sweb of life, add a bucket of water from anearby pond, if available. That will introducemillions of beneficial micro-organismsto help keep the system in check.Invariably, especially as the waterwarms in spring, you will likely see asmall algal “bloom” in your water garden.I pull out larger, floating masses ofthe algae in early spring; it’s a great additionto the compost pile.To bloom well in containers, waterlilies and other aquatic plants needperiodic fertilizer applications. Whenapplying fertilizer to your submerged,potted aquatic plants, be sure to get itpushed deeply into the soil to help preventfuture algal growth. That will feedthe plant, not leach excess nutrients intothe water, which will contribute to algaegrowth.Other aquatic plants that can showup in your water garden are floatingnatives like duckweed (Lemna sp.) andbladderwort (Utricularia vulgaris). I findthem interesting additions, not problems.If too abundant, however, you canharvest them and add them to compostor mulch. Watermeal—which is a kind24 Missouri Prairie Journal Vol. 35 No. 2

Becky EricksonMDCOn facing page, pickerel weed and below, a double-striped bluet damselfly (Enallagma basidens),one of many aquatic insects that benefit from native water plants. Above are native water lilies,which can be white- or pink-flowered.of duckweed and the world’s smallestflowering plant—can rapidly become anuisance. Remove it as soon as possible.Water Garden Preparation andMaintenanceContainer water gardens can feature oneto several plants, planted in individualpots or all together. Use heavy soil likegarden soil and clay, not potting soil,which is too lightweight and will float.An elevated or free-standing containerwill warm up more than if the samecontainer were plunged into the ground.Smaller container water gardens placedin full sun may overheat, stressing plantsand fish. Having midday shade stillallows enough sun for blooming plants.Consider having two water gardencontainers, one for water lilies and softrush that need standing water, and a secondwet soil container for marsh milkweed,cardinal flower, and copper iris.The native plants in this articlecan be found at Missouri’s native plantnurseries and many garden centers thatcarry natives. Consult www.grownative.org, Resource Guide, for a list of plantsuppliers.Maintenance on a container watergarden is minimal: natural predators likedragonflies and bats can help controlmosquitoes, but if they become a nuisance,add Mosquito Dunks monthlyto your container or pool to control thelarvae; trim spent vegetation; and overwinterfree-standing containers in anunheated garage. I also tidy up the previousyear’s stems in early spring to allowsun to reach the water for warming, andI pull out leaves that have blown in andsunk to the bottom. Every three yearsor so in early summer, I drain the pooland clean out the silt from the bottom. Idon’t like to do this annually because ofthe insects and frogs that like some mudin the bottom for overwintering.Ann’s Top Picks for Water GardensOur native water lilies (Nymphaea odorata)come in white or pink and are fragrant.If both white- and pink-floweredplants are planted in the same pond orpool, they will cross and you will havefuture plants with a wide range of whiteto deep pink blooms. To bloom well,water lilies require full sun, as well as regularfertalizing if grown in pools or tubs.At top is the native southern blue flag, andabove is duckweed, a native flowering plantthat likely will appear on its own in your watergarden. If you find it bothersome, simply scoopit out and add it to your compost pile.In mud bottom pools or ponds, theirroots are able to take up sufficient nutrients.Water lilies can reproduce by seed,but mostly by way of small tuber “buds”that float and disperse to new territory.To go with those lilies are our native irisspecies, which like having their feet wet.Southern blue flag (Iris virginica) withblues from intense, nearly purple to paleblue and, rarely, even white. These 30-to 40-inch-tall plants bloom in mid- tolate May, for about two weeks. Southernblue flag is vigorous, so it is best plantedwhere it can form large clumps. This irisalso can re-seed well.The 18- to 24-inch-tall copper iris (Irisfulva) is native to southeastern Missouri,but is winter hardy through most of thestate. Not as vigorous as southern blueflag, copper iris is quite happy grownin pots on a shelf of a water garden.Becky EricksonVol. 35 No. 2 Missouri Prairie Journal 25

MDCMDCBecky EricksonCopper iris blooms right after southernblue flag. While their blooms may notbe as large as blue flag’s, they are magnetsfor hummingbirds. Flower colorranges from lighter, rusty orange tovarying shades of terra cotta. Copper iristends to go semi-dormant after the seedsmature in August until late fall whenthey send up new leaves before winter.Besides being one of the most beautifulflowering aquatics, the 2- to 4-foottall pickerel weed (Pontederia cordata)offers many wildlife uses. Erect, spadeshapedleaves clasp pickerel weed’s spikespacked with numerous individual bluestar-shaped flowers, which are importantpollen producers for many pollinators.The flowers provide continuous floweringfrom June to October. Dragonfliesand damselflies lay their eggs on pickerelweed stems near the water surface, andpickerel and other fish seek shelter inpickerel weed clumps, hence the commonname.Water plantain (Alisma trivale) is ascharming as its name Alisma, of Celticorigin meaning water. Water plantaingrows in muddy shorelines to shallowwater. Tiny white flowers grace thefeathery flowering stalk. May throughSeptember, growing 18 to 30 inches.Water plantain reproduces by seed anddoesn’t crowd other species.Water canna, also called powdery thalia(Thalia dealbata), is statuesque with thelargest leaves of any North Americanplant other than palms. Water cannagrows 3 to 5 feet above the water withclusters of dusty violet flowers thatattract hummingbirds. Missouri is onthe northern range of water canna, soroots need to be covered by 18 to 24inches of water, or the container broughtindoors to survive winter.Native to wet prairies, moist ditches,and marshes, marsh milkweed (Asclepiasincarnata) is happy with damp feet. This3- to 5-foot tall plant prefers moist soilrather than standing water. Its clusters ofpink flowers are a favorite nectar sourcefor butterflies, and the leaves are a preferredfood source of the monarch butterflycaterpillar.All three native species of arrowhead orduck potato have white, three-petalledflowers in whorls of three on a spike:broadleaf arrowhead (Sagittaria latifolia),lance-leaf arrowhead (S. rigida),and grass-leaf arrowhead (S. graminea).Broadleaf arrowhead can grow to astately 6 feet tall, making it less suitablefor a small to medium container. Thisspecies has the leaf shape we think of asan arrowhead, and its tuber is the sizeof a large walnut. I have it in my 4 by6-foot pool because muskrats eat it outof our pond, and I really like it. Theother two species are able to hang on inour pond, perhaps because the tubersare much smaller. All arrowheads addaesthetic value to landscaped ponds andaround docks. They spread by tubers—the “duck potatoes.”MDC26 Missouri Prairie Journal Vol. 35 No. 2

This row, from far left on facing pageare copper iris, water plaintain,water canna, grassleaf arrowhead,spike rush, and sweet flag. The lowerphoto on the facing page is marshmilkweed, a preferred milkweed ofmonarch butterfly caterpillars, whicheat the leaves. Marsh milkweed alsoprovides nectar for many butterfliesand other insects.Becky EricksonMDCMDCThe grass-like spike rushes (Eleocharissp.) often grow around edges of pondsand are important for shoreline stabilization.These 24-inch-tall rushes rankvery high for frog and fish fry habitat,and waterfowl eat the seeds. The mostappropriate rush for a small water gardenwould be the blunt spike rush (E.obtusa). Another attractive species forlarger ponds is the square-stem spikerush (E. quadrangulata).Lizard’s tail (Saururus cernuus) hasstems up to 4 feet, and has shiny, darkgreen heart-shaped leaves. Many smallwhite, orange-like fragrant flowers arein spikes that form an arching, tail-likeshape. As the seeds develop, the “tail”takes on a wrinkled appearance like alizard’s tail. Lizard’s tail forms coloniesfrom spreading rhizomes, so be sure tochoose an area with ample space whenplanting.Sweet flag, (Acorus calamus), with its30- to 40-inch-tall upright, swordshaped,sweet-smelling leaves make agraceful backdrop for any lake. Sweetflag has long been planted as a wetlandfilter, and, for smaller ponds, is a betteralternative to cattails. Propagation isby root division in spring. Appropriatefor lakes, sweet flag is a graceful alternativeto native yet invasive cattails,though it may not outcompete them.Aquatics suitable for containersand smaller water gardensWater lilies (Nymphaea odorata)Southern blue flag (Iris virginica)Copper iris (Iris fulva)Soft rush (Juncus effusus)Water plantain (Alisma trivale)Spike rush (Eleocharis obtusa)Mud plantain (Heteranthera reniformis)*Bladderwort (Utricularia vulgaris)Arrowhead, duck potato (Sagittaria sp.)Marsh milkweed (Asclepias incarnata)*Pickerel weed (Pontederia cordata)Cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis)*Blue lobelia (Lobelia siphilitica)**Prefers moist soil, not standing waterQuickly spreading, aggressive,or large aquatics more suitedfor larger water gardens, ponds,and lakesWater canna, also called powdery thalia(Thalia dealbata)Bulrush species from the genusSchoenoplectus, formerly ScirpusSweet flag (Acorus calamus)Lizard tail (Saururus cernuus)Spike rush (Eleocharis quadrangulata)Broadfruit bur reed (Sparganiumeurycarpum)Marsh mallow (Hibiscus sp.)Arrowheads (Sagittaria graminea,S. latifolia)Water parsnip (Sium suave)Button bush (Cephalanthus occidentalis)Spatterdock (Nuphar lutea)More information on Missouri’snative aquatic plantsWater Plants for Missouri Ponds by JamesR. Whitley, Barbara Bassett, Joe G.Dillard, Rebecca A. HaefnerHow to Establish Aquatic Plants in YourPond: http://mdc.mo.gov/sites/default/files/resources/2010/09/9808_6784.pdfRecommended references forwater gardening in containershttp://urbanext.illinois.edu/watergarden/container.cfmhttp://watergarden.com/pages/build_wg.htmlhttp://deepgreenpermaculture.com/diy-instructions/building-a-smallwater-garden/Recommended references forwater garden constructionhttp://deepgreenpermaculture.com/diyinstructions/building-a-small-watergarden/http://urbanext.illinois.edu/watergarden/container.cfmhttp://watergarden.com/pages/build_wg.htmlIn addition to gardening with aquaticnative plants, Ann Wakeman maintains andimproves the 10-acre savanna she and herhusband created with Missouri natives.Visitors are most welcome to come seewhat can be done with small acreages;contact Ann at mike-ann@socket.net.Vol. 35 No. 2 Missouri Prairie Journal 27

Native Warm-Season Grass News • Summer 2014A Landowner’s Guide To Wildlife-Friendly GrasslandsSteve Clubine was busy trapping greater prairie-chickens in Kansas fortranslocation to Illinois this past spring, and so has an abbreviated“Native Warm-Season Grass News” in this issue. Watch for news of histrip in the fall/winter issue of the Missouri Prairie Journal.—Carol Davit, Missouri Prairie Journal editorDonnie NicholsPrairie GrouseTechnical Council MeetingIn October 2013, I visited the northern prairies of Minnesotawith the Missouri Department of Conservation’s Prairie-Chicken Recovery Team, to attend the 25 th Prairie GrouseTechnical Council meeting at Crookston. Besides presentationof prairie-chicken and sharp-tailed grouse studies and status, weenjoyed a field trip to Glacial Ridge National Wildlife Refuge(closed due to government shutdown so we had to look overthe fence at the patch-burn grazing for habitat management)and some other Minnesota public grasslands. Between thetwo trips, I saw more invasive plant problems than I ever careto again—narrowleaf and hybrid cattails, Canada thistle, andReed canarygrass in particular. They also have more problemsthan do we with sweet clover, but at least they don’t have sericealespedeza or severe problems with tall fescue.At our stop at Stipa and Tympanicus Prairies southeastof Crookston, we saw great prairie diversity and a few prairiegrouse (greater prairie-chicken and sharp-tailed grouse bothuse the areas) roosts, and a greater prairie-chicken was flushed.It was depressing to learn that both these tracts, 162 and848 acres, respectively, had until last spring been surroundedby several sections of private native prairie or ConservationReserve Grasslands that now are corn or soybeans.Another important point, which Len Gilmore of theMissouri Department of Conservation and I noted during ourhunting expedition before the meeting, is most of the publicprairie and remaining CRP grasslands were difficult for usto walk across and were too dense for prairie grouse habitat.Fortunately, many of the Minnesota Department of NaturalResource (MDNR) administrators hunt grouse and are awareof the challenge this poses for these particular species. We weretold that MDNR administrators have instructed area managersto develop grazing management plans for at least 50,000 acresof these grasslands by spring 2014. Such plans will incorporatelight to moderate grazing and patch-burn grazing that willimprove nesting and brood habitat for these grouse and providevegetative structure for flora and fauna at each end of the habitatscale.Ask SteveQuestion: If summer rains create very wet soils,I’m concerned about getting our prairie cut for hay.When is it too late to hay without hurting it?Answer: If you hay as late as mid-August, the native warmseasongrasses may be weakened a bit by not having as muchtime to rebuild root carbohydrates before frost, but effectsaren’t lasting unless it is continuously hayed late. Forbs willbenefit slightly from less grass competition. If you’re concernedabout maintaining optimum grass yield, hay earlier next yearto allow more time for root rebuilding. Forage quality will belower due to lower protein and higher lignin in late cut hay.Another option is to hay only half this year, let the otherhalf rest, and reverse the acreages next year. Hay yields oftendouble on the rested tract, offsetting the lost of the unhayedhalf and reducing harvest (mowing and raking) cost.Historically, big prairie contractors began cutting in lateJune and continued into September, but to ensure balance,often began the next year with the last prairie cut. Varyingmanagement, for example, different cutting dates, grazing someyears with varying start dates, burning at different times, etc.,are all means to healthier, more diverse prairie. No treatmentresults in long lasting change.Question: Can I cut hay higher to reduce damagefrom late cutting and maintain future yield?Answer: Cutting higher than the optimum 3" to 4" for prairiewon’t help much because the growth point is already wellabove that. Cutting height isn’t as important as cutting date forconsistent yields. Cut as early in July as feasible, but rememberwhat I said above about mixing up management for diverseprairie.Also, remember that about eight pounds of phosphorusand 22 pounds of potassium are removed with each 1,000-pound bale, effectively mining the soil of these and other nutrientsover time. You need to replace these nutrients from timeto time with phosphorus and potash fertilizer even though thecost of fertilizer usually equals the value of the hay harvested.28 Missouri Prairie Journal Vol. 35 No. 2