Confronting the Terrorism of Boko Haram in Nigeria - Resourcedat

Confronting the Terrorism of Boko Haram in Nigeria - Resourcedat

Confronting the Terrorism of Boko Haram in Nigeria - Resourcedat

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

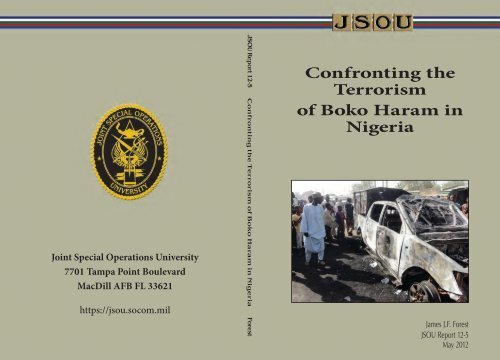

On <strong>the</strong> cover: Residents <strong>in</strong>spect a police patrol van outside Shekapolice station <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn <strong>Nigeria</strong>n city <strong>of</strong> Kano on 25 January2012. The van was burned <strong>in</strong> bomb and shoot<strong>in</strong>g attacks on <strong>the</strong>police station <strong>the</strong> previous night by approximately 30 members <strong>of</strong><strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>, wound<strong>in</strong>g a policeman and kill<strong>in</strong>g a female visitor,accord<strong>in</strong>g to residents. Photo used by permission <strong>of</strong> Newscom.

<strong>Confront<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>Terrorism</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Boko</strong><strong>Haram</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Nigeria</strong>James J.F. ForestJSOU Report 12-5The JSOU PressMacDill Air Force Base, Florida2012

This monograph and o<strong>the</strong>r JSOU publications can be found at https://jsou.socom.mil. Click on Publications. Comments about this publication are <strong>in</strong>vited andshould be forwarded to Director, Strategic Studies Department, Jo<strong>in</strong>tSpecial Operations University, 7701 Tampa Po<strong>in</strong>t Blvd., MacDill AFB FL 33621.*******The JSOU Strategic Studies Department is currently accept<strong>in</strong>g written works relevantto special operations for potential publication. For more <strong>in</strong>formation pleasecontact <strong>the</strong> JSOU Research Director at jsou_research@socom.mil. Thank you foryour <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> JSOU Press.*******This work was cleared for public release; distribution is unlimited.ISBN 978-1-933749-70-9

The views expressed <strong>in</strong> this publication are entirely those <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> author and do not necessarily reflect <strong>the</strong> views, policy,or position <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> United States Government, Department<strong>of</strong> Defense, United States Special Operations Command, or<strong>the</strong> Jo<strong>in</strong>t Special Operations University.

Recent Publications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> JSOU PressStrategic Culture and Strategic Studies: An Alternative Framework forAssess<strong>in</strong>g al-Qaeda and <strong>the</strong> Global Jihad Movement, May 2012, RichardShultzUnderstand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Form, Function, and Logic <strong>of</strong> Clandest<strong>in</strong>e Insurgentand Terrorist Networks: The First Step <strong>in</strong> Effective CounternetworkOperations, April 2012, Derek Jones“We Will F<strong>in</strong>d a Way”: Understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Legacy <strong>of</strong> Canadian SpecialOperations Forces, February 2012, Bernd HornW<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g Hearts and M<strong>in</strong>ds <strong>in</strong> Afghanistan and Elsewhere, February 2012,Thomas H. HenriksenCultural and L<strong>in</strong>guistic Skills Acquisition for Special Forces: Necessity,Acceleration, and Potential Alternatives, November 2011, Russell D. HowardOman: The Present <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Context <strong>of</strong> a Fractured Past, August 2011, RobyBarrett2011 JSOU and NDIA SO/LIC Division Essays, July 2011USSOCOM Research Topics 2012Yemen: A Different Political Paradigm <strong>in</strong> Context, May 2011, Roby BarrettThe Challenge <strong>of</strong> Nonterritorial and Virtual Conflicts: Reth<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g Counter<strong>in</strong>surgencyand Counterterrorism, March 2011, Stephen SloanCross-Cultural Competence and Small Groups: Why SOF are <strong>the</strong> waySOF are, March 2011, Jessica Glicken TurnleyInnovate or Die: Innovation and Technology for Special Operations,December 2010, Robert G. Spulak, Jr.Terrorist-Insurgent Th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g and Jo<strong>in</strong>t Special Operational Plann<strong>in</strong>gDoctr<strong>in</strong>e and Procedures, September 2010, Laure PaquetteConvergence: Special Operations Forces and Civilian Law Enforcement,July 2010, John B. AlexanderHezbollah: Social Services as a Source <strong>of</strong> Power, June 2010, James B. Love

ForewordIn this monograph counterterrorism expert James Forest assesses <strong>the</strong>threat <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong> poses to <strong>Nigeria</strong> and U.S. national security <strong>in</strong>terests.As Dr. Forest notes, <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong> is largely a local phenomenon, though onewith strategic implications, and must be understood and addressed with<strong>in</strong>its local context and <strong>the</strong> long stand<strong>in</strong>g grievances that motivate terroristactivity. Dr. Forest deftly explores <strong>Nigeria</strong>’s ethnic fissures and <strong>the</strong> role <strong>of</strong>unequal distribution <strong>of</strong> power <strong>in</strong> fuel<strong>in</strong>g terrorism. Indeed, <strong>the</strong>se conditions,comb<strong>in</strong>ed with <strong>the</strong> ready availability <strong>of</strong> weapons, contribute to <strong>Nigeria</strong>’s o<strong>the</strong>rsecurity challenges <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g militancy <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Niger Delta and organizedcrime around <strong>the</strong> economic center <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> country, Lagos.Born <strong>of</strong> colonial rule <strong>the</strong> modern state <strong>of</strong> <strong>Nigeria</strong> conta<strong>in</strong>s a multitude <strong>of</strong>ethno l<strong>in</strong>guistic groups and tribes, religious traditions, and local histories.This complexity, spread out across diverse environments from <strong>the</strong> coastalsou<strong>the</strong>rn lowlands to <strong>the</strong> dry and arid north, has long posed a daunt<strong>in</strong>gchallenge to governance and stability. <strong>Nigeria</strong> has had 14 heads <strong>of</strong> state s<strong>in</strong>ce<strong>in</strong>dependence <strong>in</strong> 1958—many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se have taken power by military coup,while only five, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> current president Goodluck Jonathan, havebeen elected. Approximately half <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> population is Christian, <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rhalf Muslim, add<strong>in</strong>g a religious dimension to <strong>Nigeria</strong>’s contested politicallife. Many groups feel economically and politically marg<strong>in</strong>alized, a situationthat <strong>in</strong>creased follow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> discovery <strong>of</strong> significant oil reserves <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NigerDelta and <strong>of</strong>fshore. Corruption is rife and state <strong>in</strong>stitutions are weak.It is with<strong>in</strong> this larger context that a group call<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>mselves <strong>Boko</strong><strong>Haram</strong>, a Hausa term mean<strong>in</strong>g “Western education is forbidden,” appeared<strong>in</strong> 2009 and has attacked <strong>Nigeria</strong>, a key U.S. ally. Government entities, suchas police stations and politicians (both Christian and Muslim), as well aso<strong>the</strong>rs who <strong>the</strong>y feel act <strong>in</strong> an ‘un-Islamic’ manner have been <strong>the</strong> primaryfocus <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se attacks. The sect, which is loosely organized and conta<strong>in</strong>snumerous disagree<strong>in</strong>g factions, is centered <strong>in</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>astern <strong>Nigeria</strong>. Most<strong>of</strong> its members are from <strong>the</strong> Kanuri tribe; it has little follow<strong>in</strong>g among o<strong>the</strong>rethnic groups <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> region or o<strong>the</strong>r parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>Nigeria</strong>. Why <strong>the</strong>n, do somef<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> group’s violent ideology attractive?To meet <strong>the</strong> security challenges posed by <strong>the</strong> <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong> and o<strong>the</strong>rs,Dr. Forest advocates <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>telligence-led polic<strong>in</strong>g and trust build<strong>in</strong>gix

About <strong>the</strong> AuthorJames J.F. Forest, Ph.D. is an associate pr<strong>of</strong>essorat <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> MassachusettsLowell, where he teaches undergraduate andgraduate courses on terrorism, weapons <strong>of</strong> massdestruction, and security studies. He is also asenior fellow with <strong>the</strong> Jo<strong>in</strong>t Special OperationsUniversity.Dr. Forest is <strong>the</strong> former Director <strong>of</strong> <strong>Terrorism</strong>Studies at <strong>the</strong> United States Military Academy.Dur<strong>in</strong>g his tenure on <strong>the</strong> faculty (2001-2010) hetaught courses <strong>in</strong> terrorism, counterterrorism,<strong>in</strong>formation warfare, <strong>in</strong>ternational relations,comparative politics, and sub-Saharan Africa. He also directed a series <strong>of</strong>research <strong>in</strong>itiatives and education programs for <strong>the</strong> Combat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Terrorism</strong>Center at West Po<strong>in</strong>t, cover<strong>in</strong>g topics such as terrorist recruitment, tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g,and organizational knowledge transfer. Dr. Forest was selected by <strong>the</strong>Center for American Progress and Foreign Policy as one <strong>of</strong> “America’s mostesteemed terrorism and national security experts” and participated <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>irannual <strong>Terrorism</strong> Index studies (2006-2010). He has been <strong>in</strong>terviewed bymany newspaper, radio, and television journalists, and is regularly <strong>in</strong>vitedto give speeches and lectures <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> U.S. and o<strong>the</strong>r countries. He has published14 books and dozens <strong>of</strong> articles <strong>in</strong> journals such as <strong>Terrorism</strong> andPolitical Violence, Contemporary Security Policy, Crime and Del<strong>in</strong>quency,Perspectives on <strong>Terrorism</strong>, <strong>the</strong> Cambridge Review <strong>of</strong> International Affairs,<strong>the</strong> Georgetown Journal <strong>of</strong> International Affairs, <strong>the</strong> Journal <strong>of</strong> PoliticalScience Education, and Democracy and Security. He has also served as anadvisor to <strong>the</strong> Future <strong>of</strong> War panel for <strong>the</strong> Defense Science Board, and hastestified before committees <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> U.S. Senate.His recent books <strong>in</strong>clude: Weapons <strong>of</strong> Mass Destruction and <strong>Terrorism</strong>,2nd edition (McGraw-Hill, 2011, with Russell Howard); Influence Warfare:How Terrorists and Governments Fight to Shape Perceptions <strong>in</strong> a War <strong>of</strong> Ideas(Praeger, 2009); Handbook <strong>of</strong> Defence Politics: International and ComparativePerspectives (Routledge, 2008, with Isaiah Wilson); Counter<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Terrorism</strong> andInsurgency <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> 21st Century (3 volumes: Praeger, 2007); Teach<strong>in</strong>g Terror:xi

Strategic and Tactical Learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Terrorist World (Rowman & Littlefield,2006); Homeland Security: Protect<strong>in</strong>g America’s Targets (3 volumes: Praeger,2006); The Mak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> a Terrorist: Recruitment, Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and Root Causes (3volumes: Praeger, 2005).Dr. Forest received his graduate degrees from Stanford University andBoston College, and undergraduate degrees from Georgetown Universityand De Anza College.xii

PrefaceThe Islamic sect <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong> has been a security challenge to <strong>Nigeria</strong>s<strong>in</strong>ce at least 2009, but <strong>the</strong> group has recently expanded its terroristattacks to <strong>in</strong>clude <strong>in</strong>ternational targets such as <strong>the</strong> United Nations build<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> Abuja <strong>in</strong> August 2011. In November 2011, <strong>the</strong> U.S. Department <strong>of</strong> Stateissued an alert for all U.S. and Western citizens <strong>in</strong> Abuja to avoid majorhotels and landmarks, based on <strong>in</strong>formation about a potential <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>attack. Their attack capabilities have become more sophisticated, and <strong>the</strong>reare <strong>in</strong>dications that members <strong>of</strong> this group may have received tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>bomb-mak<strong>in</strong>g and o<strong>the</strong>r terrorist tactics from al-Qaeda-affiliated groups <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> north and/or east <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>ent. A spate <strong>of</strong> attacks aga<strong>in</strong>st churchesfrom December 2011 through February 2012 suggests a strategy <strong>of</strong> provocation,through which <strong>the</strong> group seeks to spark a large scale sectarian conflictthat will destabilize <strong>the</strong> county. These are troubl<strong>in</strong>g developments <strong>in</strong> analready troubled region, and <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational community is focus<strong>in</strong>g an<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g amount <strong>of</strong> attention on <strong>the</strong> situation.This monograph explores <strong>the</strong> orig<strong>in</strong>s and future trajectory <strong>of</strong> <strong>Boko</strong><strong>Haram</strong>, and especially why its ideology <strong>of</strong> violence has found resonanceamong a small number <strong>of</strong> young <strong>Nigeria</strong>ns. It is organized <strong>in</strong> sequentiallayers <strong>of</strong> analysis, with chapters that exam<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> grievances that motivatemembers and sympathizers <strong>of</strong> <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>, sociopolitical factors thatsusta<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir ideological resonance and operational capabilities, and how<strong>the</strong> <strong>Nigeria</strong>n government has responded to <strong>the</strong> threat <strong>of</strong> terrorism <strong>in</strong> recentyears. Special attention is given to <strong>the</strong> role <strong>of</strong> nongovernmental entities<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> fight aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>—community and religious entities thathave considerable <strong>in</strong>fluence among potential recruits and supporters <strong>of</strong> thisgroup. These entities can play an important role <strong>in</strong> counter<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> group’sideology and <strong>the</strong> socioeconomic and religious <strong>in</strong>securities upon which itsresonance is based. Based on this analysis, <strong>the</strong> monograph concludes byidentify<strong>in</strong>g ways <strong>in</strong> which <strong>Nigeria</strong> could respond more effectively to <strong>the</strong>threat posed by <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>, and provides some thoughts for how <strong>the</strong>U.S., and particularly Special Operations Forces, may contribute to <strong>the</strong>seefforts. The observations provided <strong>in</strong> this JSOU monograph are based on<strong>in</strong>terviews conducted dur<strong>in</strong>g a research trip to <strong>Nigeria</strong> and via email, as wellas extensive analysis <strong>of</strong> academic publications and open source documents.xiii

The security situation <strong>in</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn <strong>Nigeria</strong> is very dynamic and constantlyevolv<strong>in</strong>g, thus a list <strong>of</strong> resources is <strong>of</strong>fered <strong>in</strong> Appendix B for those <strong>in</strong>terested<strong>in</strong> additional <strong>in</strong>formation.xiv

AcknowledgmentsProduc<strong>in</strong>g this research monograph required assistance from a number <strong>of</strong><strong>in</strong>dividuals. To beg<strong>in</strong> with, I must extend my s<strong>in</strong>cere thanks to MukhtariShitu, Ibaba Samuel Ibaba, Jennifer Giroux, Peter Nwilo, Freedom Onouha,Lieutenant Colonel Matt Sousa, and Thomas Maettig for <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>valuableassistance <strong>in</strong> arrang<strong>in</strong>g local <strong>in</strong>terviews <strong>in</strong> <strong>Nigeria</strong>, to <strong>in</strong>clude places that Imost likely wouldn’t have been able to visit o<strong>the</strong>rwise. Of course, any errors<strong>of</strong> fact or <strong>in</strong>terpretation <strong>in</strong> this monograph are entirely my own. Also, <strong>the</strong>pr<strong>of</strong>essional and adm<strong>in</strong>istrative staff at <strong>the</strong> Jo<strong>in</strong>t Special Operations Universityprovided a broad range <strong>of</strong> critical logistics support for my researchtrips to West Africa, and I am very grateful for all <strong>the</strong>ir efforts and patience.Fur<strong>the</strong>r gratitude is given to Dr. Kenneth Poole and his senior colleagues <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> Strategic Studies Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> university, who graciously allowedme <strong>the</strong> flexibility to adapt a previously envisioned (but ultimately untenable)research project on West Africa <strong>in</strong>to this focused study <strong>of</strong> <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>.F<strong>in</strong>ally, I give thanks to my family—Alicia, Chloe, and Jackson—for <strong>the</strong>irpatience and support.xv

Forest: <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>1. Introduction<strong>Nigeria</strong>, a key strategic ally <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> U.S., has come under attack by a radicalIslamic sect known as <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong> (a Hausa term for “Westerneducation is forbidden”). It <strong>of</strong>ficially calls itself “Jama’atul Alhul SunnahLidda’wati wal Jihad” which means “people committed to <strong>the</strong> propagation<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Prophet’s teach<strong>in</strong>gs and jihad.” As its name suggests, <strong>the</strong> group isadamantly opposed to what it sees as a Western-based <strong>in</strong>cursion that threatenstraditional values, beliefs, and customs among Muslim communities <strong>in</strong>nor<strong>the</strong>rn <strong>Nigeria</strong>. In an audiotape posted on <strong>the</strong> Internet <strong>in</strong> January 2012,a spokesman for <strong>the</strong> group, Abubakar Shekau, even accused <strong>the</strong> U.S. <strong>of</strong>wag<strong>in</strong>g war on Islam. 1 As will be described <strong>in</strong> this monograph, <strong>the</strong> group islargely a product <strong>of</strong> widespread socioeconomic and religious <strong>in</strong>securities,and its ideology resonates among certa<strong>in</strong> communities because <strong>of</strong> bothhistorical narratives and modern grievances.Members <strong>of</strong> <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong> are drawn primarily from <strong>the</strong> Kanuri tribe(roughly 4 percent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> population), who are concentrated <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>asternstates <strong>of</strong> <strong>Nigeria</strong> like Bauchi and Borno, and <strong>the</strong> Hausa and Fulani(29 percent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> population) spread more generally throughout most <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn states. Kanuri also <strong>in</strong>habit regions across <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn border<strong>in</strong>to Niger, and <strong>the</strong>re is evidence to suggest that <strong>the</strong>se tribal relationshipsfacilitate weapons traffick<strong>in</strong>g and o<strong>the</strong>r cross-border smuggl<strong>in</strong>g transactions,but this is <strong>the</strong> extent to which <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>’s activities go outside<strong>Nigeria</strong>. While it is very much a locally-oriented movement, <strong>the</strong> group hasnot yet attracted a significant follow<strong>in</strong>g among <strong>Nigeria</strong>ns <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r tribal orethnic backgrounds. Fur<strong>the</strong>r, it has thus far proven difficult for <strong>the</strong> group t<strong>of</strong><strong>in</strong>d sympathizers or anyone who would help <strong>the</strong>m facilitate attacks fur<strong>the</strong>rsouth, thus <strong>the</strong> majority <strong>of</strong> attacks have taken place with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> north (andprimarily nor<strong>the</strong>astern corner) <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> country. S<strong>in</strong>ce 2009, <strong>the</strong> group hasattacked police stations and patrols, politicians (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g village chiefs anda member <strong>of</strong> parliament), religious leaders (both Christian and Muslim),and <strong>in</strong>dividuals whom <strong>the</strong>y deem to be engaged <strong>in</strong> un-Islamic activities,like dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g beer. <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong> has also carried out several mass casualtyattacks and is <strong>the</strong> first militant group <strong>in</strong> <strong>Nigeria</strong> to embrace <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> suicidebomb<strong>in</strong>gs. A representative list <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se attacks is provided <strong>in</strong> Appendix A<strong>of</strong> this monograph.1

Forest: <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>factions as “evil.” The authors <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> leaflet, assert<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> legacy <strong>of</strong> founderMohammed Yusuf, distanced <strong>the</strong>mselves from attacks on civilians and onhouses <strong>of</strong> worship. 6 Some local observers now discrim<strong>in</strong>ate between a Kogi<strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>, Kanuri <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>, and Hausa Fulani <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>. And<strong>the</strong>re are also <strong>in</strong>dividuals or groups <strong>of</strong> armed thugs whose attacks on banksor o<strong>the</strong>r targets are blamed on <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>; <strong>in</strong> some cases, <strong>the</strong> perpetratorswill even claim <strong>the</strong>y are members <strong>of</strong> <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>, when <strong>in</strong> truth <strong>the</strong>y aremotivated more by crim<strong>in</strong>al objectives than by <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>’s core ideologicalor religious objectives.Help<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Nigeria</strong> confront this complex, multifaceted terrorist threat is<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> U.S. and <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational community. In early 2012,<strong>Nigeria</strong>n President Goodluck Jonathan declared a state <strong>of</strong> emergency <strong>in</strong> fourstates—Yobe, Borno, Plateau, and Niger—<strong>in</strong> concert with <strong>the</strong> deployment <strong>of</strong>armed forces, <strong>the</strong> temporary clos<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational borders <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rnregions, and <strong>the</strong> establishment <strong>of</strong> a special counterterrorism force. Should<strong>the</strong> country’s latest efforts to confront and defeat <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong> fail, <strong>the</strong> terroristviolence could worsen, underm<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g an already fragile regime andpossibly spill<strong>in</strong>g over <strong>in</strong>to neighbor<strong>in</strong>g countries. As <strong>the</strong> region’s largest oilsupplier, <strong>the</strong> global economic impact <strong>of</strong> a prolonged campaign <strong>of</strong> terrorismcould be severe. The human toll <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> terrorist violence is also reach<strong>in</strong>gvery worrisome levels; several hundred <strong>Nigeria</strong>ns were killed or <strong>in</strong>jured <strong>in</strong><strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong> attacks <strong>in</strong> just <strong>the</strong> first two months <strong>of</strong> 2012.This study is <strong>of</strong>fered as a resource for those engaged <strong>in</strong> policy or strategicdeliberations about how to assist <strong>Nigeria</strong> <strong>in</strong> confront<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> threat <strong>of</strong> <strong>Boko</strong><strong>Haram</strong>. The observations provided here are based on <strong>in</strong>terviews conducteddur<strong>in</strong>g a research trip to <strong>Nigeria</strong> and via email, as well as extensive analysis<strong>of</strong> academic publications and open source documents. The monograph isespecially <strong>in</strong>tended as a useful background for members <strong>of</strong> U.S. SpecialOperations Forces (SOF) with <strong>in</strong>terests (or mission assignments) <strong>in</strong> sub-Saharan Africa. Much <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> analysis illustrates <strong>the</strong> complex and <strong>in</strong>tersect<strong>in</strong>gk<strong>in</strong>ds <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation needed to understand <strong>the</strong> phenomenon <strong>of</strong> modernreligiously-<strong>in</strong>spired domestic terrorism, so it should hopefully be useful to<strong>the</strong> general counterterrorism practitioner as well. It seeks to address severalbasic questions, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g: How did <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong> emerge? Is it differentfrom o<strong>the</strong>r terrorist groups? What do SOF leaders need to know about <strong>Boko</strong><strong>Haram</strong>, and what does it represent <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> broader security challenges <strong>in</strong><strong>Nigeria</strong> or West Africa? And f<strong>in</strong>ally, what might SOF—if called upon—want3

JSOU Report 12-5or need to do <strong>in</strong> response to <strong>the</strong> terrorist threat <strong>of</strong> <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>? To beg<strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> discussion, this <strong>in</strong>troductory chapter reviews <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>mes addressed<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> monograph and expla<strong>in</strong>s how <strong>the</strong>se relate to <strong>the</strong> research literature<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> field <strong>of</strong> terrorism studies.Conceptual Framework and Organization <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Monograph<strong>Terrorism</strong> is a highly contextual phenomenon. Indeed, <strong>the</strong> old maxim that“all politics is local” holds true for political violence as well. We sometimeshear a lot <strong>of</strong> talk about terrorism as if it were a monolithic, easily understoodterm, but it is really <strong>the</strong> opposite. <strong>Terrorism</strong> is a complex issue thathas been studied and debated for several decades. In fact, <strong>the</strong>re are dozens<strong>of</strong> compet<strong>in</strong>g def<strong>in</strong>itions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> term, not only among scholars but amongpolicymakers and government agencies as well. But one th<strong>in</strong>g holds constant—terroristattacks do not occur <strong>in</strong> a vacuum, but are <strong>in</strong>stead a product<strong>of</strong> complex <strong>in</strong>teractions between <strong>in</strong>dividuals, organizations, and environments.7 Fur<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong>re are many different k<strong>in</strong>ds <strong>of</strong> terrorism, def<strong>in</strong>ed primarilyby ideological orientations like ethno-nationalism, left-w<strong>in</strong>g, religious,and so forth. And just like <strong>the</strong>re are many different k<strong>in</strong>ds <strong>of</strong> terrorism, <strong>the</strong>reare many different k<strong>in</strong>ds <strong>of</strong> contexts <strong>in</strong> which terrorism occurs.With<strong>in</strong> each context, we f<strong>in</strong>d a variety <strong>of</strong> grievances that motivate <strong>the</strong>terrorist group and its supporters, along with th<strong>in</strong>gs that facilitate terroristactivities. From decades <strong>of</strong> research on <strong>the</strong>se grievances and facilitators, twoprimary <strong>the</strong>mes appear most salient for this research monograph on <strong>Boko</strong><strong>Haram</strong>: preconditions, or “th<strong>in</strong>gs that exist,” and triggers, or “th<strong>in</strong>gs thathappen.” 8 Chapter 2 thus provides a brief exam<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Nigeria</strong>’s politicalhistory, with an emphasis on how <strong>the</strong> government has struggled to developlegitimacy among its citizens. Of particular note, as Alex Thurston recentlyobserved, state legitimacy is at its weakest <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>ast. 9 Naturally, <strong>the</strong>early history <strong>of</strong> West Africa is also salient: centuries <strong>of</strong> slave traders robbed<strong>the</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>ent <strong>of</strong> its most productive laborers, <strong>the</strong>n came <strong>the</strong> era <strong>of</strong> colonizationby Western European powers, followed by <strong>in</strong>dependence movements,civil wars, and military coups. However, due to space constra<strong>in</strong>ts, Chapter2 does not delve much <strong>in</strong>to this deeper history, and focuses just on <strong>the</strong> post<strong>in</strong>dependenceera <strong>of</strong> <strong>Nigeria</strong>.This is followed <strong>in</strong> Chapter 3 with a discussion <strong>of</strong> key grievances thatare shared by most <strong>Nigeria</strong>ns. Generally speak<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>the</strong> research literature4

Forest: <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>describes grievances as structural reasons for why <strong>the</strong> ideology resonatesamong a particular community, and can <strong>in</strong>clude a broad range <strong>of</strong> politicalissues like <strong>in</strong>competent, authoritarian, or corrupt governments, as well aseconomic issues like widespread poverty, unemployment, or an overall lack<strong>of</strong> political or socioeconomic opportunities. <strong>Terrorism</strong> is most <strong>of</strong>ten fueledby <strong>in</strong>dividuals and groups who are very dissatisfied with <strong>the</strong> status quo, andhave come to believe <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> need to use violence because <strong>the</strong>y see no o<strong>the</strong>rway to facilitate change. In essence, <strong>the</strong>y draw on what Harvard psychologistJohn Mack described as a reservoir <strong>of</strong> misery, hurt, helplessness, and ragefrom which <strong>the</strong> foot soldiers <strong>of</strong> terrorism can be recruited.” 10 Clearly, onecan f<strong>in</strong>d such a reservoir <strong>in</strong> many parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>Nigeria</strong>, and <strong>in</strong>deed throughoutmuch <strong>of</strong> sub-Saharan Africa.<strong>Terrorism</strong> is also seen as a violent product <strong>of</strong> an unequal distribution <strong>of</strong>power on local, national, or global levels. The unequal distribution <strong>of</strong> powerfeeds a perception <strong>of</strong> “us versus <strong>the</strong>m,” a perception found <strong>in</strong> all ideologiesassociated with politically violent groups and movements. The hardshipsand challenges “we” face can be framed <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> what “<strong>the</strong>y” are or what“<strong>the</strong>y” have done to us. From this perspective, “we” desire a redistribution <strong>of</strong>power <strong>in</strong> order to have more control over our dest<strong>in</strong>y, and one could arguethat many terrorist groups use violence as <strong>the</strong> way to br<strong>in</strong>g this about. AsBruce H<strong>of</strong>fman notes, terrorism is “<strong>the</strong> deliberate creation and exploitation<strong>of</strong> fear through violence or <strong>the</strong> threat <strong>of</strong> violence <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> pursuit <strong>of</strong> politicalchange . . . [and] to create power where <strong>the</strong>re is none or to consolidate powerwhere <strong>the</strong>re is very little.” 11 There are few places on earth where <strong>the</strong> unequaldistribution <strong>of</strong> power is more common than <strong>in</strong> sub-Saharan Africa. And<strong>in</strong> <strong>Nigeria</strong>, ethnic fissures are politicized and negatively impact a person’soverall quality <strong>of</strong> life and <strong>the</strong>ir relative power to br<strong>in</strong>g about change. Fur<strong>the</strong>r,Muslims <strong>in</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>rn <strong>Nigeria</strong> at one po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>in</strong> history enjoyed considerablymore power relative to o<strong>the</strong>rs <strong>in</strong> West Africa, but <strong>the</strong>y have witnessed <strong>the</strong> fall<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sokoto Caliphate, <strong>the</strong> rise <strong>of</strong> Western European colonization followedby successive military regimes, and now a secular democracy. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore,unemployment and illiteracy are highest <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>Nigeria</strong>,where Muslims are predom<strong>in</strong>ant. In essence, power—or lack <strong>the</strong>re<strong>of</strong>—playsan important role <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> narrative <strong>of</strong> <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>.Government corruption is also cited by many researchers as a frequentmotivator beh<strong>in</strong>d collective political violence, and is highlighted <strong>in</strong> Chapter3. In states where such corruption is endemic, resources, privileges, and5

JSOU Report 12-5advantages are reserved for a select group <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> people or rul<strong>in</strong>g elite. Corruptionencumbers <strong>the</strong> fair distribution <strong>of</strong> social services and adds ano<strong>the</strong>rlayer to <strong>the</strong> resentment caused by <strong>the</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> political participation. The rest<strong>of</strong> society, because <strong>the</strong>y have no voice, is ignored or placated. This corruptionerodes <strong>the</strong> government’s legitimacy <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> eyes <strong>of</strong> its citizens. 12 In <strong>Nigeria</strong>, as<strong>in</strong> much <strong>of</strong> West Africa, a comb<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> statist economic policies (build<strong>in</strong>gon <strong>the</strong> early post-<strong>in</strong>dependence nationalization <strong>of</strong> former colonial private<strong>in</strong>dustries) comb<strong>in</strong>ed with patronage systems to create an environment <strong>in</strong>which <strong>the</strong> state became seen as a means <strong>of</strong> access to wealth, ra<strong>the</strong>r than ameans to serve <strong>the</strong> people.When a government fails to adhere to <strong>the</strong> conventional social contractbetween government and <strong>the</strong> governed, its citizens become disenchantedand seek <strong>the</strong> power to force change. This, <strong>in</strong> turn, has resulted <strong>in</strong> a variety<strong>of</strong> revolutionary movements throughout history. Corrupt governments seekto ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> and <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>the</strong>ir power over o<strong>the</strong>rs and over resources by anymeans necessary, while <strong>the</strong> powerless see <strong>the</strong> corruption and look for ways tocombat it—even through violent acts <strong>of</strong> terrorism, as that may be perceivedas <strong>the</strong>ir only form <strong>of</strong> recourse. InWhen a government fails to adhereto <strong>the</strong> conventional social<strong>the</strong> African context, corruption has<strong>in</strong>deed been a common underly<strong>in</strong>gcontract between government andfactor <strong>in</strong> various forms <strong>of</strong> politicalviolence, and is cited <strong>of</strong>ten by<strong>the</strong> governed, its citizens becomedisenchanted and seek <strong>the</strong> power<strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong> as one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> motivat<strong>in</strong>gcauses for <strong>the</strong>ir campaign <strong>of</strong>to force change.terror.Beyond grievances, <strong>the</strong> study <strong>of</strong> terrorism also looks at a range <strong>of</strong> facilitators,loosely def<strong>in</strong>ed as <strong>the</strong> structural or temporary conditions at <strong>the</strong> communityor regional level that provide <strong>in</strong>dividuals and organizations withample opportunities to engage <strong>in</strong> various forms <strong>of</strong> terrorist activity. Chapter4 looks specifically at security challenges that have plagued <strong>Nigeria</strong> formany years, focus<strong>in</strong>g on three hotspots <strong>in</strong> particular: militants <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NigerDelta (sou<strong>the</strong>ast), organized crime <strong>in</strong> Lagos (southwest), and <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>,based ma<strong>in</strong>ly <strong>in</strong> Borno and Bauchi states (nor<strong>the</strong>ast). In all three cases, <strong>the</strong>rise <strong>of</strong> violence has been aided by <strong>the</strong> availability <strong>of</strong> small arms and lightweapons. 13 Meanwhile, traffickers <strong>in</strong> drugs, humans, and weapons cohabitwith <strong>the</strong> warlords, militia leaders, and political opportunists <strong>in</strong> an environmentthat precludes good governance and judicial oversight. 14 Countries6

Forest: <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>like <strong>Nigeria</strong> with a robust “shadow economy”—economic activities that areunderground, covert, or illegal—can provide an <strong>in</strong>frastructure for terroristorganizations to operate <strong>in</strong>, whereby f<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g becomes easier and detect<strong>in</strong>git becomes more difficult. 15Chapter 5 <strong>the</strong>n turns to look at <strong>the</strong> organization <strong>of</strong> <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong> itself.Here, <strong>in</strong> addition to describ<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> group’s formation and <strong>in</strong>itial leadership,we also have to look at how potential triggers may contribute to <strong>the</strong> emergence<strong>of</strong> a religiously oriented terrorist group like this. While <strong>the</strong> preconditionsfor terrorism are aplenty <strong>in</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn <strong>Nigeria</strong>, <strong>the</strong> tough questionsto answer here <strong>in</strong>clude: What has led to <strong>the</strong> current outbreak <strong>of</strong> violence,predom<strong>in</strong>ately, but not exclusively, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> form <strong>of</strong> <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>? Have conditionssomehow worsened <strong>in</strong> recent years? Is <strong>the</strong> violence largely a result <strong>of</strong> aparticularly popular radicaliz<strong>in</strong>g agent? Studies <strong>of</strong> terrorism have described“triggers” as specific actions, policies, and events that enhance <strong>the</strong> perceivedneed for action with<strong>in</strong> a particular environment. These are very dynamicand time-relevant, and seized upon by <strong>the</strong> propagandists <strong>of</strong> terrorist organizations<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir attempts to enhance <strong>the</strong> resonance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir ideology. A triggerfor action can be any number <strong>of</strong> th<strong>in</strong>gs: a change <strong>in</strong> government policy,like <strong>the</strong> suspension <strong>of</strong> civil liberties, a bann<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> political parties, or <strong>the</strong><strong>in</strong>troduction <strong>of</strong> new censorship and draconian antiterrorist laws; an erosion<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> security environment (like a massive <strong>in</strong>flux <strong>of</strong> refugees, or a naturaldisaster that diverts <strong>the</strong> government’s attention away from monitor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>group); a widely-publicized <strong>in</strong>cident <strong>of</strong> police brutality or <strong>in</strong>vasive surveillance;and even a coup, assass<strong>in</strong>ation, or o<strong>the</strong>r sudden regime change. 16 Insome <strong>in</strong>stances, a trigger may occur <strong>in</strong> an entirely different country. Forexample, <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>vasion and subsequent occupation <strong>of</strong> Iraq by U.S.-led coalitionforces has been l<strong>in</strong>ked to major terrorist attacks <strong>in</strong> Madrid (2004) andLondon (2005), as well as <strong>in</strong> Iraq itself.A trigger does not necessarily need to be a relatively quick or conta<strong>in</strong>edevent. For example, research by Paul Ehrlich and Jack Liu suggests thatpersistent demographic and socioeconomic factors can facilitate transnationalterrorism and make it easier to recruit terrorists. 17 Specifically, <strong>the</strong>ydescribe how <strong>in</strong>creased birth rates and <strong>the</strong> age composition <strong>of</strong> populations<strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countries affects resource consumption, prices, governmentrevenues and expenditures, demand for jobs, and labor wages. In essence,<strong>the</strong>se demographic and socioeconomic conditions could lead to <strong>the</strong> emergence<strong>of</strong> more terrorism and terrorists for many decades to come. Similarly,7

JSOU Report 12-5<strong>the</strong> National Intelligence Council’s 2025 Project report notes that pend<strong>in</strong>g“youth bulges” <strong>in</strong> many Arab states could contribute to a rise <strong>in</strong> politicalviolence and civil conflict. 18 This is particularly salient with regard to <strong>Nigeria</strong>:nearly half <strong>the</strong> population is under <strong>the</strong> age <strong>of</strong> 19.Any potential triggers are far more likely to enhance a terrorist organization’sideological resonance when <strong>the</strong> structural conditions describedearlier are already a source <strong>of</strong> grievances. A trigger could also be an eventthat leads to new opportunities for terrorism. For example, a sudden regimechange may create an anarchic environment <strong>in</strong> which groups f<strong>in</strong>d greaterfreedom to obta<strong>in</strong> weapons and conduct crim<strong>in</strong>al and violent activity. Terroristgroups will usually seize any opportunity to capitalize on events fromwhich <strong>the</strong>y could benefit strategically, tactically, or operationally.This leads us to <strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong> <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>: What events or contextualchanges might <strong>the</strong>y be capitaliz<strong>in</strong>g on to support <strong>the</strong>ir ideological rationalefor violent attacks? To beg<strong>in</strong>, <strong>the</strong> president <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> country, Goodluck Jonathan,is a Christian from <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>ast <strong>of</strong> <strong>Nigeria</strong>. In his 2011 re-election,virtually <strong>the</strong> entire nor<strong>the</strong>rn part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> country voted for <strong>the</strong> oppositioncandidate. Riots erupted <strong>in</strong> various cities when <strong>the</strong> election results wereannounced, despite <strong>the</strong> assurances <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>dependent observers that <strong>the</strong> vot<strong>in</strong>ghad <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>the</strong> fewest “irregularities” <strong>in</strong> <strong>Nigeria</strong>’s democratic history.Meanwhile, a grow<strong>in</strong>g sense <strong>of</strong> economic malaise has been felt throughout<strong>the</strong> country for some time, and is most palpable <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> north, which hasroughly half <strong>the</strong> gross domestic product (GDP) per capita as <strong>the</strong> south. Alongstand<strong>in</strong>g history <strong>of</strong> corruption and patronage at <strong>the</strong> federal, state, andlocal levels <strong>of</strong> government is a source <strong>of</strong> widespread dissatisfaction towardpoliticians, <strong>the</strong> legal system, and law enforcement, and <strong>the</strong>se sentiments maybe found <strong>in</strong> greater depths and concentration <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> north than elsewhere<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> country. As will be explored later <strong>in</strong> this monograph, several politicaland socioeconomic changes over <strong>the</strong> past several years can be identified aspotential triggers beh<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> recent and grow<strong>in</strong>g threat <strong>of</strong> violence <strong>in</strong>flictedby members <strong>of</strong> <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>. But <strong>in</strong> addition to <strong>the</strong>se, a useful dimensionfor analysis is <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> slow wan<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> power and <strong>in</strong>fluence amongMuslim leaders <strong>in</strong> a democratic <strong>Nigeria</strong>.8

Forest: <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>Ideological and Religious DimensionsA terrorist group’s ideology plays a vital role <strong>in</strong> an <strong>in</strong>dividual’s decision toengage <strong>in</strong> terrorist activity by sanction<strong>in</strong>g harmful conduct as honorableand righteous. An ideology is an articulation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> group’s vision <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>future, a vision which its adherents believe cannot be achieved without <strong>the</strong>use <strong>of</strong> violence. These ideologies typically articulate and expla<strong>in</strong> a set <strong>of</strong>grievances <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g socioeconomic disadvantages and a lack <strong>of</strong> justice orpolitical freedoms that are seen as legitimate among members <strong>of</strong> a targetaudience, along with strategies through which <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> violence is meantto address those grievances. 19 Usually, but not always, <strong>the</strong> strategies <strong>the</strong>y putforward require jo<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g or at least support<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> organization—thus, anideology also provides a group identity and highlights <strong>the</strong> common characteristics<strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividuals who adhere to, or are potential adherents <strong>of</strong>, <strong>the</strong>ideology. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to Assaf Moghadam, “ideologies are l<strong>in</strong>ks betweenthoughts, beliefs and myths on <strong>the</strong> one hand, and action on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand... [provid<strong>in</strong>g] a ‘cognitive map’ that filters <strong>the</strong> way social realities are perceived,render<strong>in</strong>g that reality easier to grasp, more coherent, and thus moremean<strong>in</strong>gful.” 20Research by Andrew Kydd and Barbara Walter <strong>in</strong>dicates that terroristorganizations are usually driven by political objectives, and <strong>in</strong> particular,“five have had endur<strong>in</strong>g importance: regime change, territorial change,policy change, social control and status quo ma<strong>in</strong>tenance.” 21 These objectiveshave led to terrorist groups form<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Ireland, Italy, Egypt,Germany, Sri Lanka, Japan, Indonesia, <strong>the</strong> Philipp<strong>in</strong>es, <strong>the</strong> United States,and many o<strong>the</strong>r nations. The members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se groups have viewed terrorismas an effective vehicle for political change, <strong>of</strong>ten po<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g to historicalexamples <strong>of</strong> terrorism driv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> United States (and later Israel) out <strong>of</strong>Lebanon, and conv<strong>in</strong>c<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> French to pull out <strong>of</strong> Algeria. Ethnic separatistgroups like <strong>the</strong> Liberation Tigers <strong>of</strong> Tamil Eelam <strong>in</strong> Sri Lanka <strong>the</strong> AbuSayyaf Group <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Philipp<strong>in</strong>es and <strong>the</strong> Euskadi Ta Askatasuna <strong>in</strong> Spa<strong>in</strong>all want <strong>the</strong> power to form <strong>the</strong>ir own recognized, sovereign entity, carvedout <strong>of</strong> an exist<strong>in</strong>g nation-state, and believe terrorist attacks can help <strong>the</strong>machieve this objective. Groups engaged <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Middle East <strong>in</strong>tifada—like<strong>the</strong> Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade, Hamas, <strong>the</strong> Palest<strong>in</strong>ian Islamic Jihad, and<strong>the</strong> Palest<strong>in</strong>e Liberation Front—want <strong>the</strong> power to establish an Islamic Palest<strong>in</strong>ianstate. O<strong>the</strong>r groups want <strong>the</strong> power to establish an Islamic state9

JSOU Report 12-5<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir own region, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Ansar al-Islam <strong>in</strong> Iraq <strong>the</strong> Armed IslamicGroup <strong>in</strong> Algeria Al-Gama ‘a al-Islamiyya <strong>in</strong> Egypt <strong>the</strong> Islamic Movement<strong>of</strong> Uzbekistan <strong>in</strong> Central Asia 22 Jemaah Islamiyah <strong>in</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>ast Asia andal-Qaeda. In all cases, <strong>the</strong>se groups seek power to change <strong>the</strong> status quo, t<strong>of</strong>orge a future that <strong>the</strong>y do not believe will come about peacefully, and aredeterm<strong>in</strong>ed to use terrorism as a means to achieve <strong>the</strong>ir objectives.A terrorist group’s ideology plays a central role <strong>in</strong> its survival. Frompolitical revolutionaries to religious militants, ideologies <strong>of</strong> violence andterrorism must have resonance; that is, an ideology has no motivat<strong>in</strong>g powerunless it resonates with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> social, political, and historical context <strong>of</strong> thosewhose support <strong>the</strong> organization requires. The resonance <strong>of</strong> an organization’sideology is largely based on a comb<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> persuasive communicators, <strong>the</strong>compell<strong>in</strong>g nature <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> grievances articulated, and <strong>the</strong> pervasiveness <strong>of</strong>local conditions that seem to justify an organization’s rationale for <strong>the</strong> use<strong>of</strong> violence <strong>in</strong> order to mitigate those grievances. When an organization’sideology resonates among its target audience, it can <strong>in</strong>fluence an <strong>in</strong>dividual’sperceptions and help determ<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> form <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir “decision tree,” a menu<strong>of</strong> potential options for future action that may <strong>in</strong>clude terrorism. Thus, thismonograph will focus particular attention on <strong>the</strong> ideology that has beenarticulated by leaders and spokespeople <strong>of</strong> <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong> <strong>in</strong> recent years.At <strong>the</strong> same time, it is important to recognize that support for terrorismamong community members can rise and fall over time and is <strong>in</strong>fluencedby <strong>the</strong> choices made by <strong>in</strong>dividuals with<strong>in</strong> an organization about <strong>the</strong> k<strong>in</strong>ds<strong>of</strong> terrorist activities <strong>the</strong>y conduct. How organizations choreograph violencematters; <strong>in</strong> particular, terrorist groups must avoid counterproductiveviolence that can lead to a loss <strong>of</strong> support with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> community. Thischallenge confronts <strong>the</strong> leaders <strong>of</strong> <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>, and is explored later <strong>in</strong> thismonograph as a potential vulnerability <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> group.Overall, successful terrorist organizations capitalize on an environment<strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong>ir ideology resonates and <strong>the</strong>ir grievances are considered legitimateby smart, competent <strong>in</strong>dividuals who are <strong>the</strong>n motivated to act ei<strong>the</strong>rwith or on behalf <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> organization. The likelihood <strong>of</strong> ideological resonanceis greater when members <strong>of</strong> a community are desperate for justice,social agency, human dignity, a sense <strong>of</strong> belong<strong>in</strong>g, or positive identity whensurrounded by a variety <strong>of</strong> depress<strong>in</strong>gly negative environmental conditions,and <strong>in</strong>tense outrage, or hatred <strong>of</strong> a specific entity because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>iractions (real or perceived). How a local environment susta<strong>in</strong>s a terrorist10

Forest: <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>organization depends largely on how <strong>in</strong>dividuals with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> communityview <strong>the</strong> opportunities for that organization’s success. The past also matters:Is <strong>the</strong>re a history <strong>of</strong> political violence ei<strong>the</strong>r locally or with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> surround<strong>in</strong>gregion? Are <strong>the</strong>re regional examples <strong>of</strong> successes or failures <strong>of</strong> terrorism?These and o<strong>the</strong>r questions, addressed later <strong>in</strong> this monograph, <strong>in</strong>form ourunderstand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> how a terrorist group like <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong> has come to exist,and how it is attract<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dividuals to support <strong>the</strong>ir cause.F<strong>in</strong>ally, our analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong> must take <strong>in</strong>to account researchon why some <strong>in</strong>dividuals may choose direct <strong>in</strong>volvement <strong>in</strong> actions thatkill, while o<strong>the</strong>rs choose to engage <strong>in</strong> activities like provid<strong>in</strong>g fund<strong>in</strong>g, safehavens, or ideological support for a terrorist group. A variety <strong>of</strong> factors <strong>in</strong>fluencea person’s decision to engage <strong>in</strong> terrorist activity—from k<strong>in</strong>ship andideology to <strong>the</strong> availability <strong>of</strong> weapons and crim<strong>in</strong>al network connections.Scholars have also cited <strong>the</strong> importance <strong>of</strong> a person’s hatred <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs, desirefor power or revenge, despair, risk tolerance, unbreakable loyalty to friendsor family who are already <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> a violent movement, prior participation<strong>in</strong> a radical political movement, thirst for excitement and adventure,and many o<strong>the</strong>r types <strong>of</strong> motivations.Over <strong>the</strong> years, psychologists have sought to illum<strong>in</strong>ate a unique set<strong>of</strong> attributes that contribute to terrorism. There is clearly a demand forthis among policymakers and <strong>the</strong> general public who seek clarity <strong>in</strong> whatis <strong>in</strong> fact a very complex problem. 23 However, <strong>the</strong> most common result <strong>of</strong>research <strong>in</strong> this area actually reveals a pattern <strong>of</strong> “normalcy”—that is, <strong>the</strong>absence <strong>of</strong> any unique attribute or identifier that would dist<strong>in</strong>guish one<strong>in</strong>dividual from ano<strong>the</strong>r. Andrew Silke recently observed how researchon <strong>the</strong> mental state <strong>of</strong> terrorists has found that <strong>the</strong>y are rarely mad, andvery few suffer from personality disorders. 24 Accord<strong>in</strong>g to John Horgan,“Many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> personal traits or characteristics [identified <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> research]as belong<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> terrorist are nei<strong>the</strong>r specific to <strong>the</strong> terrorist nor serveto dist<strong>in</strong>guish one type <strong>of</strong> terrorist from ano<strong>the</strong>r. . . There are no a-prioriqualities [<strong>of</strong> an <strong>in</strong>dividual] that enable us to predict <strong>the</strong> likelihood <strong>of</strong> risk <strong>of</strong><strong>in</strong>volvement and engagement” <strong>in</strong> terrorism. 25 Likewise, Clark McCauley hasobserved that “30 years <strong>of</strong> research has found little evidence that terroristsare suffer<strong>in</strong>g from psychopathology,” 26 and Marc Sageman agrees, not<strong>in</strong>ghow “experts on terrorism have tried <strong>in</strong> va<strong>in</strong> for three decades to identify acommon predisposition for terrorism.” 2711

JSOU Report 12-5Overall, <strong>the</strong>re is no s<strong>in</strong>gle psychology <strong>of</strong> terrorism, no unified <strong>the</strong>ory. 28The broad diversity <strong>of</strong> personal motivations for becom<strong>in</strong>g a terrorist underm<strong>in</strong>es<strong>the</strong> possibility <strong>of</strong> a s<strong>in</strong>gle, common “terrorist m<strong>in</strong>dset.” Thus, pr<strong>of</strong>il<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>dividuals based on some type <strong>of</strong> perceived propensity to conductterrorist attacks becomes extremely difficult, if not altoge<strong>the</strong>r impossible. 29This is critical for <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nigeria</strong>n authorities to understand about terrorism:should <strong>the</strong>y make <strong>the</strong> false assumption (which many governments <strong>in</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rcountries have made) that terrorists can be identified by some sort <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>il<strong>in</strong>g,<strong>the</strong>ir effort to defeat <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong> will be counterproductive, andpossibly even exacerbate <strong>the</strong> current security challenge.The research <strong>in</strong>dicates that <strong>in</strong>dividuals from virtually any backgroundcan choose to engage <strong>in</strong> terrorist activity. Thus, an especially promis<strong>in</strong>garea <strong>of</strong> research on <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual risk <strong>of</strong> terrorist activity uses phrases andmetaphors like “pathways to radicalization” and “staircase to terrorism”to describe a dynamic process <strong>of</strong> psychological development that leads an<strong>in</strong>dividual to participate <strong>in</strong> terrorist activity. 30 In one particularly noteworthyexample, Max Taylor and John Horgan <strong>of</strong>fer a framework for analyz<strong>in</strong>gdevelopmental processes—“a sequence <strong>of</strong> events <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g steps or operationsthat are usefully ordered and/or <strong>in</strong>terdependent”—through whichan <strong>in</strong>dividual becomes <strong>in</strong>volved with (and sometimes abandons) terroristactivity. 31 Their research highlights <strong>the</strong> importance <strong>of</strong> understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>dynamic context that <strong>in</strong>dividuals operate <strong>in</strong>, and how <strong>the</strong> relationshipsbetween contexts, organizations, and <strong>in</strong>dividuals affect behavior. 32 Thisreturns us to <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>itial discussion provided <strong>in</strong> this chapter: context is key.Each day, countless <strong>in</strong>dividuals grapple with situations and environmentalconditions that may generate feel<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> outrage and powerlessness, amongmany o<strong>the</strong>r potential motivators for becom<strong>in</strong>g violent. But an <strong>in</strong>dividual’sview <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se situations and conditions—and how to respond appropriatelyto <strong>the</strong>m—is clearly <strong>in</strong>fluenced by <strong>the</strong>ir family members, peers, and personalrole models, educators, religious leaders, and o<strong>the</strong>rs who help <strong>in</strong>terpret andcontextualize local and global conditions. Because <strong>the</strong>se <strong>in</strong>terpretive <strong>in</strong>fluencesplay such a key role <strong>in</strong> how an <strong>in</strong>dividual responds to <strong>the</strong> challenges<strong>of</strong> everyday life events and trends that generate political grievances amongmembers <strong>of</strong> a particular community, we sometimes see a contagion effect,whereby an <strong>in</strong>dividual’s likelihood <strong>of</strong> becom<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> terrorism is<strong>in</strong>creased because <strong>the</strong>y know or respect o<strong>the</strong>rs who have already done so.Fur<strong>the</strong>r, as Taylor and Horgan note, “There is never one route to terrorism,12

Forest: <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>but ra<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>re are <strong>in</strong>dividual routes, and fur<strong>the</strong>rmore those routes andactivities as experienced by <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual change over time.” 33The dynamics <strong>of</strong> an <strong>in</strong>dividual’s connections to o<strong>the</strong>rs—<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g, forexample, family, friends, small groups, clubs, gangs, and diasporas—alsohelp an <strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>in</strong>terpret <strong>the</strong> potential legitimacy <strong>of</strong> an organization thathas adopted terrorism as a strategy. Individuals are <strong>of</strong>ten <strong>in</strong>troduced to <strong>the</strong>fr<strong>in</strong>ges <strong>of</strong> violent extremist groups by friends, family members, and authorityfigures <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir community, among o<strong>the</strong>rs. 34 For example, psychologistSageman has argued that social bonds play a central role <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> emergence<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> global Salafi jihad, <strong>the</strong> movement whose members comprise organizationslike al-Qaeda and its affiliates <strong>in</strong> North Africa and Sou<strong>the</strong>ast Asia. 35 Asdescribed earlier, an organization that is perceived as legitimate is <strong>the</strong>n ableto exert <strong>in</strong>fluence on <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual’s perceptions <strong>of</strong> environmental conditionsand what to do about <strong>the</strong>m. Thus, <strong>the</strong> religious dimension <strong>of</strong> <strong>Boko</strong><strong>Haram</strong>’s ideology—and its perceived capability <strong>of</strong> provid<strong>in</strong>g that criticallegitimacy—must be taken <strong>in</strong>to account.For many contemporary terrorist groups, a compell<strong>in</strong>g ideology playsa central role at <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tersection <strong>of</strong> religious, political, and socioeconomicgrievances, organizational attributes, and <strong>in</strong>dividual characteristics. Religioncan be a powerful motivator for all k<strong>in</strong>ds <strong>of</strong> human action, becauseas psychologist John Mack has noted, religion “deals with spiritual or ultimatehuman concerns, such as life or death, our highest values and selves,<strong>the</strong> roots <strong>of</strong> evil, <strong>the</strong> existence <strong>of</strong> God… Religious assumptions shape ourm<strong>in</strong>ds from childhood, and for this reason religious systems and <strong>in</strong>stitutionshave had, and cont<strong>in</strong>ue to have, extraord<strong>in</strong>ary power to affect <strong>the</strong> course <strong>of</strong>human history.” 36 Like many religious terrorist groups around <strong>the</strong> world,<strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>’s ideology portrays <strong>the</strong> world <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> an epic strugglebetween good and evil, and <strong>the</strong>y are conv<strong>in</strong>ced <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir own revealed truthfrom God. Many religious terroristgroups share a common beliefthat <strong>the</strong>y are follow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> will<strong>of</strong> God, and that only <strong>the</strong> truebelievers are guaranteed salvationand victory.<strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>’s ideology portrays <strong>the</strong>world <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> an epic strugglebetween good and evil...At <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual level, Harvard researcher Jessica Stern describes howfor religious extremists “<strong>the</strong>re is no room for <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r person’s po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>of</strong>view. Because <strong>the</strong>y believe <strong>the</strong>ir cause is just, and because <strong>the</strong> population13

JSOU Report 12-5<strong>the</strong>y hope to protect is purportedly so deprived, abused, and helpless, <strong>the</strong>ypersuade <strong>the</strong>mselves that any action—even a he<strong>in</strong>ous crime—is justified.They believe that God is on <strong>the</strong>ir side.” 37 For <strong>the</strong>se <strong>in</strong>dividuals, religion hashelped <strong>the</strong>m simplify an o<strong>the</strong>rwise complex life, and becom<strong>in</strong>g part <strong>of</strong> aradical movement has given <strong>the</strong>m support, a sense <strong>of</strong> purpose, an outlet <strong>in</strong>which to express <strong>the</strong>ir grievances (sometimes related to personal or socialhumiliation), and “new identities as martyrs on behalf <strong>of</strong> a purported spiritualcause.” 38 In <strong>the</strong>ir eyes, <strong>the</strong> superiority <strong>of</strong> God’s rules provides <strong>the</strong>mwith a feel<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> justification for violat<strong>in</strong>g man-made rules aga<strong>in</strong>st violentatrocities. Do<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> bidd<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> a higher power demands sacrifice but alsomeans fewer limits on violence. It’s easier to kill if you th<strong>in</strong>k you’re do<strong>in</strong>gGod’s will; violence is seen as necessary <strong>in</strong> order to save oneself, one’s family,or even <strong>the</strong> world.In terms <strong>of</strong> environmental conditions and grievances, <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>’sideology articulates a vision <strong>of</strong> social and political order that is more pureand religiously grounded. As <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>’s found<strong>in</strong>g leader Yusuf preached,“Our land was an Islamic state before <strong>the</strong> colonial masters turned it to a kafirland. The current system is contrary to true Islamic beliefs.” 39 <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>’sideology describes how white European colonial powers drew l<strong>in</strong>es on amap <strong>in</strong> a somewhat arbitrary and capricious plan to carve up <strong>the</strong> Africancont<strong>in</strong>ent, and <strong>in</strong> many cases empowered local tribes—frequently, many<strong>of</strong> which had embraced Christianity—to rule as proxy landlords until <strong>the</strong>end <strong>of</strong> WWII and a wave <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>dependence movements that saw <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong>colonial rule. But what came next has been even worse: rampant corruptionamong a political and wealthy elite that is heavily <strong>in</strong>vested <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> status quo;a huge gap between aspirations <strong>of</strong> <strong>Nigeria</strong>’s youth and <strong>the</strong> opportunitiesprovided by <strong>the</strong> system for achiev<strong>in</strong>g a better life; a lack <strong>of</strong> critical <strong>in</strong>frastructureand basic support services; a history with long periods <strong>of</strong> militarydictatorship and political oppression; a swell<strong>in</strong>g population amid economicdespair; and a system <strong>in</strong> which entrenched ethnic identities are politicizedand constra<strong>in</strong> opportunities for meritocratic advancement or for be<strong>in</strong>g ableto worship one’s faith <strong>in</strong> accordance with a strict <strong>in</strong>terpretation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Koran.The cumulative result <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se th<strong>in</strong>gs is an environment <strong>in</strong> which radicalextremist ideologies can thrive among communities that see <strong>the</strong>mselves aspolitically and economically disadvantaged and marg<strong>in</strong>alized.Throughout <strong>the</strong> Muslim communities <strong>of</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn <strong>Nigeria</strong> today, <strong>the</strong>reis a sense <strong>of</strong> unease and <strong>in</strong>security about <strong>the</strong> spiritual and moral future <strong>of</strong>14

Forest: <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong><strong>the</strong>ir children, and concern about <strong>the</strong> fad<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>fluence <strong>of</strong> religious leaderslike <strong>the</strong> Sultan <strong>of</strong> Sokoto. 40 In addition, <strong>the</strong>re are also specific political andsocioeconomic frustrations found predom<strong>in</strong>antly <strong>in</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn <strong>Nigeria</strong>—poverty, unemployment, and lack <strong>of</strong> education are much higher here than<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> rest <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> country. <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>, like o<strong>the</strong>r religious terrorist groupsthroughout <strong>the</strong> world, thus capitalizes on local conditions by <strong>of</strong>fer<strong>in</strong>g envisionedsolutions to <strong>the</strong> grievances shared by <strong>the</strong> surround<strong>in</strong>g communities.They portray <strong>the</strong> situation <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> a Muslim population oppressed bynon-Muslim rulers, <strong>in</strong>fidels, and apostates backed by s<strong>in</strong>ister forces that<strong>in</strong>tend to keep <strong>the</strong> local Muslim communities subservient. Its followers arereportedly <strong>in</strong>fluenced by <strong>the</strong> Koranic phrase: “Anyone who is not governedby what Allah has revealed is among <strong>the</strong> transgressors.” 41 More on <strong>Boko</strong><strong>Haram</strong>’s ideology, and <strong>the</strong> underly<strong>in</strong>g reasons why it resonates among particularcommunities <strong>in</strong> <strong>Nigeria</strong>, will be provided <strong>in</strong> Chapter 5.The f<strong>in</strong>al two chapters <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> monograph explore ways <strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong>response to <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong> can be made more effective. To beg<strong>in</strong>, because <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> group’s ideology and attack patterns, <strong>the</strong>y are clearly a <strong>Nigeria</strong>n problemrequir<strong>in</strong>g a <strong>Nigeria</strong>n solution. There have been no attacks attributed to <strong>Boko</strong><strong>Haram</strong> outside <strong>Nigeria</strong>, and most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir attacks have occurred with<strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong>ir traditional area <strong>of</strong> operation with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn states <strong>of</strong> Bauchi andBorno. Thus, this is clearly a domestic terrorist problem, one that mostobservers believe <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nigeria</strong>n government can handle. However, <strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>alchapter <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> monograph <strong>of</strong>fers some observations for what <strong>the</strong> U.S. and <strong>the</strong><strong>in</strong>ternational community might be able to <strong>of</strong>fer <strong>Nigeria</strong>’s government andnongovernmental entities to aid <strong>the</strong>m <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir fight aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>Boko</strong> <strong>Haram</strong>.Fur<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> event that SOF personnel are called upon to help <strong>the</strong> <strong>Nigeria</strong>ngovernment <strong>in</strong> some capacity, this monograph exam<strong>in</strong>es some implications<strong>of</strong> this analysis that should be useful for a SOF readership.SummaryTo sum up, this study is organized around a sequence <strong>of</strong> conceptual build<strong>in</strong>gblocks. First, because history is such a vital dimension <strong>of</strong> anyone’s perceptionabout <strong>the</strong> world and <strong>the</strong>ir place with<strong>in</strong> it, a brief political history <strong>of</strong><strong>Nigeria</strong> is provided. The next two chapters exam<strong>in</strong>e grievances that negativelyimpact <strong>the</strong> relationship between citizens and <strong>the</strong> state, and securitychallenges that stem from <strong>the</strong>se grievances. The monograph <strong>the</strong>n explores15