Lagos is the ground of the films, not just in the sense that ... - myweb

Lagos is the ground of the films, not just in the sense that ... - myweb

Lagos is the ground of the films, not just in the sense that ... - myweb

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Lagos</strong> <strong>is</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>ground</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> <strong>films</strong>, <strong>not</strong> <strong>just</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>sense</strong> <strong>that</strong> when camerasare turned on, <strong>the</strong>y makeimages <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong>, but also<strong>that</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>films</strong> are a meansfor Nigerians to come toterms with <strong>the</strong> city andeveryth<strong>in</strong>g it embodies.

Nollywood <strong>in</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong>,<strong>Lagos</strong> <strong>in</strong> Nollywood FilmsJonathan HaynesNollywood—<strong>the</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong>-based Nigerian film <strong>in</strong>dustry—hasbecome <strong>the</strong> third-largest film <strong>in</strong>dustry <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> world, and it <strong>is</strong>by far <strong>the</strong> most powerful purveyor <strong>of</strong> an image <strong>of</strong> Nigeria todomestic and foreign populations. It cons<strong>is</strong>ts <strong>of</strong> many smallproducers work<strong>in</strong>g with t<strong>in</strong>y amounts <strong>of</strong> capital; it <strong>the</strong>reforehas <strong>not</strong> been able to build its own spaces—studios, <strong>the</strong>aters,<strong>of</strong>fice complexes—and rema<strong>in</strong>s nearly <strong>in</strong>v<strong>is</strong>ible <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong>cityscape, apart from film posters and <strong>the</strong> <strong>films</strong> <strong>the</strong>mselves,d<strong>is</strong>played for sale as cassettes or video compact d<strong>is</strong>cs. Materialconstra<strong>in</strong>ts and <strong>the</strong> small screens for which <strong>the</strong> <strong>films</strong>are designed shape <strong>the</strong> images <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong> <strong>that</strong> appear <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>m.Nigerian videos differ markedly from typical African celluloid<strong>films</strong>, both <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir “film language” and <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir handl<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> city. They present <strong>Lagos</strong> as a turbulent and dangerouslandscape, where class div<strong>is</strong>ions are extreme but permeable,and enormous wealth does <strong>not</strong> buy <strong>in</strong>sulation from chaosand m<strong>is</strong>ery. They show supernatural forces permeat<strong>in</strong>g allsocial levels, particularly <strong>the</strong> wealthiest. A shared real<strong>is</strong>m,born <strong>of</strong> location shoot<strong>in</strong>g and common strategies for imag<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> desires and fears <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> audience, creates a considerablecoherence <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> representation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong>, despite <strong>the</strong> size andvariety <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> city and <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dustry.Concurrent with <strong>the</strong> r<strong>is</strong>e <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Nollywood video film <strong>in</strong>dustry has been anew v<strong>is</strong>ibility, on certa<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>tellectual horizons, <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong> metropol<strong>is</strong>—or“megacity,” as it has been dubbed, as its population approaches 15 million.(It <strong>is</strong> projected by <strong>the</strong> United Nations to reach 23 million by 2015—whichwould make <strong>Lagos</strong> <strong>the</strong> third-largest city <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> world.) The city owes its newv<strong>is</strong>ibility to its serv<strong>in</strong>g as an example and case study <strong>in</strong> d<strong>is</strong>cussions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>world’s urban future. On <strong>the</strong> one hand, <strong>the</strong>re <strong>is</strong> a genre <strong>of</strong> lurid descriptions<strong>of</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong> as urban “apocalypse”—a term <strong>that</strong> foreign v<strong>is</strong>itors seem to f<strong>in</strong>dunavoidable, as <strong>the</strong>y f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>in</strong> it <strong>the</strong> ultimate expression <strong>of</strong> anarchic urbancatastrophe, environmental destruction, and human m<strong>is</strong>ery; its “crime, pollution,and overcrowd<strong>in</strong>g make it <strong>the</strong> cliché par excellence <strong>of</strong> Third World

africa today 132 Nollywood <strong>in</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong>, <strong>Lagos</strong> <strong>in</strong> Nollywood Filmsurban dysfunction” (Kaplan 2000:15). On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand, <strong>the</strong>re <strong>is</strong> a postmodern<strong>is</strong>t-<strong>in</strong>flectedcelebration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cop<strong>in</strong>g mechan<strong>is</strong>ms and creative forms<strong>of</strong> self-organization <strong>of</strong> a population whose ability to survive contradictsord<strong>in</strong>ary common <strong>sense</strong>, accompanied by an argument about <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>ability <strong>of</strong>conventional modes <strong>of</strong> understand<strong>in</strong>g to expla<strong>in</strong> what permits th<strong>is</strong> survival.The lead<strong>in</strong>g figure <strong>in</strong> th<strong>is</strong> trend <strong>is</strong> <strong>the</strong> Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas, whohas been conduct<strong>in</strong>g a study <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong> with students <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Harvard School<strong>of</strong> Design’s Project on <strong>the</strong> City. <strong>Lagos</strong> has figured prom<strong>in</strong>ently <strong>in</strong> major artexhibitions <strong>in</strong> London (Century City, 2001), Barcelona (Africas: The Art<strong>is</strong>tand <strong>the</strong> City, 2001), and, most <strong>in</strong>fluentially, Kassel, where <strong>the</strong> exhibitionDocumenta 11 (2002), curated by Okwui Enwezor, <strong>in</strong>cluded a weeklongforum held <strong>in</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong>. These shows emphasize <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>genuity <strong>of</strong> people struggl<strong>in</strong>gto survive <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> slums and <strong>in</strong>formal economic sector <strong>of</strong> African cities,<strong>the</strong> manic energy <strong>that</strong> pervades city life, and urban art<strong>is</strong>ts’ creativity (for areview <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se d<strong>is</strong>courses on <strong>Lagos</strong>, see Gandy 2005). 1The celebratory character <strong>of</strong> Koolhaas’s po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>of</strong> view has been criticizedon several scores: <strong>that</strong> it ignores <strong>the</strong> suffer<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> poor and <strong>the</strong>predation <strong>of</strong> many arrangements <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formal sector (Gandy 2005; Packer2006); <strong>that</strong> it obscures <strong>the</strong> h<strong>is</strong>torical processes through which th<strong>in</strong>gs gotto be how <strong>the</strong>y are and who <strong>is</strong> responsible for <strong>the</strong>m (Gandy 2005); <strong>that</strong> iteffectively takes <strong>of</strong>f <strong>the</strong> table <strong>the</strong> possibilities for rational and progressivepolitical and economic change (Gandy 2006); and <strong>that</strong> it overestimates <strong>the</strong>extent to which cop<strong>in</strong>g with adversity <strong>is</strong> stimulat<strong>in</strong>g, ra<strong>the</strong>r than depress<strong>in</strong>g(Subirós 2001b). But, <strong>the</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>that</strong> ex<strong>is</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g vocabularies and analyticalframes <strong>of</strong> reference from urban plann<strong>in</strong>g and o<strong>the</strong>r d<strong>is</strong>cipl<strong>in</strong>es are trapped<strong>in</strong> an almost entirely negative contemplation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong>’s deficiencies andfailures and are <strong>in</strong>adequate <strong>in</strong> show<strong>in</strong>g how th<strong>in</strong>gs actually operate needsto be given its due.Nollywood <strong>is</strong> an extraord<strong>in</strong>ary example <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sort <strong>of</strong> cop<strong>in</strong>g mechan<strong>is</strong>m<strong>that</strong> keeps Africa alive: out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> impossibility <strong>of</strong> produc<strong>in</strong>g celluloid<strong>films</strong> <strong>in</strong> Nigeria (because <strong>of</strong> economic collapse and social <strong>in</strong>security) came ahuge <strong>in</strong>dustry, constructed on <strong>the</strong> slenderest <strong>of</strong> means and without anyone’sperm<strong>is</strong>sion (Haynes 1995). Cruelly constra<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> its material circumstances,it <strong>is</strong> a heroic act <strong>of</strong> self-assertion—on <strong>the</strong> part <strong>of</strong> Nigeria <strong>in</strong> general, and <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>in</strong>dividual filmmakers. Franco Sacchi’s documentary film Th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> Nollywoodnicely captures its personality: people are kept go<strong>in</strong>g through <strong>the</strong> seriocomicobstacle course <strong>of</strong> mak<strong>in</strong>g a film under Nigerian conditions by a desperateneed to hope and dream, by <strong>the</strong> legendary Nigerian resilience and humor, andby a peculiarly African mixture <strong>of</strong> resignation and determ<strong>in</strong>ation.In 2002, when <strong>the</strong> term Nollywood was co<strong>in</strong>ed, it met with oppositionfrom Nigerians who thought it suggested <strong>that</strong> Nigerian filmmak<strong>in</strong>g wasonly a copy <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> American model, Hollywood. It <strong>is</strong> here to stay becauseit expresses <strong>the</strong> general Nigerian desire for a mass enterta<strong>in</strong>ment <strong>in</strong>dustry<strong>that</strong> can take its rightful place on <strong>the</strong> world stage, but both <strong>the</strong> term and <strong>the</strong>phenomenon need to be read as signs <strong>that</strong> <strong>the</strong> global media environment hasbecome multipolar, ra<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>that</strong> Hollywood’s example <strong>is</strong> unavoidable

(Haynes 2005). Despite an undeniable imitative element (Nollywood drawson a great number <strong>of</strong> cultural <strong>in</strong>fluences, domestic and foreign, Hollywoodamong <strong>the</strong>m), Nollywood fundamentally does <strong>not</strong> resemble Hollywood oranyth<strong>in</strong>g else—apart from its smaller sibl<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>the</strong> Ghanaian video film <strong>in</strong>dustry.The geographers Sallie Marston, Keith Woodward, and John Paul JonesIII make a radical <strong>the</strong>oretical argument for understand<strong>in</strong>g Nollywood <strong>not</strong>as an example <strong>of</strong> scalar models <strong>of</strong> hierarchical relationships (<strong>the</strong> dom<strong>in</strong>antmodel <strong>in</strong> d<strong>is</strong>cussions <strong>of</strong> globalization), which would <strong>in</strong>evitably f<strong>in</strong>d Nollywoodto be a defective imitation <strong>of</strong> Hollywood, but as an example <strong>of</strong> specificallysituated, localized social activity, networked with o<strong>the</strong>r sites, <strong>that</strong>produces someth<strong>in</strong>g fundamentally different from Hollywood <strong>in</strong> production,d<strong>is</strong>tribution, consumption, and aes<strong>the</strong>tics (2007).Salimata Wade, ano<strong>the</strong>r geographer, makes a po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>that</strong> overlaps withKoolhaas’s observation about <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>adequacy <strong>of</strong> Western categories to describe<strong>the</strong> realities <strong>of</strong> African cities. As Pep Subirós reports her conversation,she says<strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> problem with African cities, at least those <strong>in</strong> WesternAfrica, <strong>is</strong> one <strong>of</strong> perception and representation. The differences<strong>that</strong> ex<strong>is</strong>t <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> images, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> viewpo<strong>in</strong>ts, and <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> aspirations<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> key urban players. Especially between politiciansand managers on <strong>the</strong> one hand and ord<strong>in</strong>ary people on <strong>the</strong>o<strong>the</strong>r. (2001a:20–21)africa today 133 Jonathan HaynesThe former th<strong>in</strong>k like Europeans, Wade says, see<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>frastructural problemsand so on; <strong>the</strong> latter br<strong>in</strong>g with <strong>the</strong>m (from <strong>the</strong> villages from which most<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m emigrated) views and habits <strong>that</strong> cause <strong>the</strong>m to neglect facilitiesprovided for <strong>the</strong>m, or to remake <strong>the</strong>m to suit <strong>the</strong>ir own purposes. The city<strong>the</strong>y <strong>in</strong>habit or want to <strong>in</strong>habit <strong>is</strong> <strong>not</strong> <strong>the</strong> one <strong>the</strong> authorities understand orwant to build.The commercial success <strong>of</strong> Nollywood <strong>films</strong> depends on <strong>the</strong>ir expression<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>of</strong> view—<strong>the</strong> values, desires, and fears—<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir popularaudience, and <strong>the</strong>refore <strong>the</strong>y help us see what <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>tended viewers see orwant to see when <strong>the</strong>y look at <strong>the</strong>ir city. These images differ d<strong>is</strong>t<strong>in</strong>ctly fromthose familiar from o<strong>the</strong>r African c<strong>in</strong>ematic and literary traditions.<strong>Lagos</strong> <strong>is</strong> where Nollywood <strong>is</strong> primarily located, and for budgetaryreasons its <strong>films</strong> are always shot on location, most <strong>of</strong>ten <strong>in</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong>, whichserves as <strong>the</strong> <strong>ground</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>films</strong>, <strong>not</strong> <strong>just</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> immediate <strong>sense</strong> <strong>that</strong> whencameras are turned on, <strong>the</strong>y make images <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong> (or one might even say,<strong>Lagos</strong> imposes its images on <strong>the</strong>m), but also <strong>that</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>films</strong> are a means forNigerians to come to terms—v<strong>is</strong>ually, dramatically, emotionally, morally,socially, politically, and spiritually—with <strong>the</strong> city and everyth<strong>in</strong>g it embodies.Nollywood’s imag<strong>in</strong>ation forms <strong>the</strong> city’s images, mak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>m publicemblems <strong>of</strong> fear and desire. Nollywood <strong>is</strong> a part <strong>of</strong> <strong>that</strong> cityscape, an element<strong>in</strong> its v<strong>is</strong>ual culture. Th<strong>is</strong> cityscape <strong>is</strong> a resource <strong>that</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>films</strong> shareand an environment <strong>that</strong> shapes <strong>the</strong>m materially. Th<strong>is</strong> essay explores <strong>the</strong>se

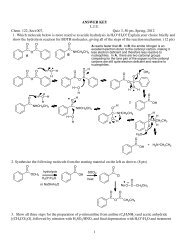

eciprocal relationships, always with an eye to material circumstances,aim<strong>in</strong>g to describe <strong>the</strong> specificities <strong>that</strong> give Nollywood its character.Nollywood <strong>in</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong>africa today 134 Nollywood <strong>in</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong>, <strong>Lagos</strong> <strong>in</strong> Nollywood FilmsNigerian video film production began <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> late 1980s as a humble popularartform, but it has grown <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> third-largest film <strong>in</strong>dustry <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> world,produc<strong>in</strong>g more than 1,500 titles per year (National Film and Video CensorsBoard 2006). The image <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Nigerian nation, literally and metaphorically,<strong>is</strong> now largely shaped by <strong>the</strong>se <strong>films</strong>, which have become wildly popularacross <strong>the</strong> African cont<strong>in</strong>ent and beyond. Video film <strong>is</strong> <strong>the</strong> primary expressivemedium through which <strong>Lagos</strong> makes itself v<strong>is</strong>ible, both to itself and toexternal audiences.<strong>Lagos</strong> <strong>is</strong> <strong>the</strong> center <strong>of</strong> Nigeria’s filmmak<strong>in</strong>g and film d<strong>is</strong>tribution, asit <strong>is</strong> <strong>the</strong> center <strong>of</strong> most <strong>of</strong> Nigeria’s <strong>in</strong>dustrial and commercial activity, but<strong>the</strong>re are o<strong>the</strong>r important Nigerian filmmak<strong>in</strong>g centers, <strong>not</strong>ably Kano, <strong>in</strong>nor<strong>the</strong>rn Nigeria, home to a large, parallel, but almost entirely separateHausa video <strong>in</strong>dustry. The term Nollywood refers pr<strong>in</strong>cipally to sou<strong>the</strong>rnNigerian, Engl<strong>is</strong>h-language <strong>films</strong>, whose d<strong>is</strong>tribution <strong>is</strong> largely controlled byIgbo marketers, but which are made by people from <strong>the</strong> full range <strong>of</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rnNigerian ethnicities. Nollywood has come <strong>in</strong>to general use as <strong>the</strong> name<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Nigerian video film <strong>in</strong>dustry, but when used <strong>in</strong> th<strong>is</strong> way, <strong>the</strong> termobscures <strong>the</strong> Hausa branch and Yoruba-language video production based <strong>in</strong><strong>Lagos</strong>, though <strong>the</strong> Yoruba production partly overlaps with <strong>that</strong> <strong>of</strong> Nollywood.The term <strong>in</strong>cludes film production and market<strong>in</strong>g centers <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> easternNigerian cities <strong>of</strong> Enugu, Onitsha and Aba, which are <strong>in</strong>tegrated with <strong>the</strong>market<strong>in</strong>g system based <strong>in</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong>.The central paradox <strong>of</strong> Nollywood <strong>is</strong> <strong>that</strong> it <strong>is</strong> a huge <strong>in</strong>dustry, employ<strong>in</strong>gthousands <strong>of</strong> people and generat<strong>in</strong>g large (if largely unverifiable) revenues,but it <strong>is</strong> built on t<strong>in</strong>y capital formations. Cheap and easily operatedvideo technology allowed it to ar<strong>is</strong>e as an <strong>in</strong>formal-sector activity, likeo<strong>the</strong>r African “popular arts,” such as Congolese pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>the</strong> designs andproverbs pa<strong>in</strong>ted on trucks, and Yoruba travel<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ater (Barber 1987, 2000;Fabian 1978; Haynes and Okome 1998). The film <strong>that</strong> “opened <strong>the</strong> market,”Kenneth Nnebue’s Liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Bondage 1 (1992), was made for a few hundreddollars. An extremely dysfunctional d<strong>is</strong>tribution system and rampant piracymake large <strong>in</strong>vestments <strong>in</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gle <strong>films</strong> r<strong>is</strong>ky, hold<strong>in</strong>g average budgets downto about U.S. $20,000. The <strong>in</strong>dustry rema<strong>in</strong>s d<strong>is</strong>engaged from banks, governmentloans, and o<strong>the</strong>r formal sector sources <strong>of</strong> capital; it still cons<strong>is</strong>ts <strong>of</strong>myriad very-small-scale producers, who make each new film on <strong>the</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>itsfrom <strong>the</strong> last, or on advances from marketers.As a result, <strong>the</strong> Nigerian film <strong>in</strong>dustry has had no money with whichto construct its own v<strong>is</strong>ible spaces. Nollywood <strong>is</strong> <strong>not</strong> a place: it cons<strong>is</strong>ts <strong>of</strong>nodes scattered across <strong>Lagos</strong> and beyond, lost <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> metropol<strong>is</strong>. Idumota,<strong>the</strong> center <strong>of</strong> market<strong>in</strong>g and f<strong>in</strong>ance, <strong>is</strong> a market <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> oldest part <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong>;

Figure 1. Video cassettes on sale <strong>in</strong> Idumota Market, <strong>the</strong> heart <strong>of</strong> Nollywoodmarket<strong>in</strong>g. Photo by Jonathan Haynesafrica today 135 Jonathan Haynesits streets are narrow, filthy, and packed with people and handcarts haul<strong>in</strong>gplastic buckets, consumer electronic goods, and cloth (figure 1). V<strong>is</strong>it<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>major marketers <strong>in</strong>volves balanc<strong>in</strong>g on boards thrown over open sewers andpenetrat<strong>in</strong>g damp warrens <strong>of</strong> crumbl<strong>in</strong>g concrete.The producers are scattered mostly around <strong>the</strong> neighborhoods <strong>of</strong> Surulereand Ikeja, on <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>land, where <strong>the</strong>re are few proper sidewalks and <strong>the</strong>streets may become nearly impassable when it ra<strong>in</strong>s, but <strong>the</strong>re are fashionboutiques and <strong>in</strong>ternational-style fast-food restaurants, and a forest <strong>of</strong> cellphonetowers and satellite d<strong>is</strong>hes r<strong>is</strong>es above air-conditioned <strong>in</strong>ternet cafésand <strong>in</strong>ternational telephone call-centers, all powered by generators dur<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> frequent blackouts—<strong>in</strong>dependent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> national grid and aimed at <strong>the</strong>sky. Here where Nigerian <strong>films</strong> are produced it <strong>is</strong> surpr<strong>is</strong><strong>in</strong>gly hard to buy orrent <strong>the</strong>m—video shops are almost entirely dom<strong>in</strong>ated by American <strong>films</strong>.The masses who consume Nollywood <strong>films</strong> live <strong>in</strong> poorer neighborhoods.The producers occupy modest bungalows or <strong>of</strong>fice spaces on side streets.They have small edit<strong>in</strong>g studios, <strong>of</strong>ten with respectable digital equipment,and keep <strong>the</strong>ir digital cameras locked <strong>in</strong> closets, but <strong>the</strong>y have no productionstudios and sound stages.For years, <strong>the</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciple meet<strong>in</strong>g place for actors and producers wasW<strong>in</strong>i’s Guest House, where <strong>the</strong> floor was sticky with beer and <strong>the</strong> furniturewas apt to tear one’s cloth<strong>in</strong>g. Under pressure to relocate by neighbors upsetby <strong>the</strong> no<strong>is</strong>e, <strong>the</strong> frequent blockage <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> street, and <strong>the</strong> difficulty <strong>of</strong> d<strong>is</strong>t<strong>in</strong>gu<strong>is</strong>h<strong>in</strong>gaspir<strong>in</strong>g actresses from prostitutes, <strong>the</strong> film people moved fromW<strong>in</strong>i’s to O’Jez’s, a more attractive nightclub and restaurant, located <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>

africa today 136 Nollywood <strong>in</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong>, <strong>Lagos</strong> <strong>in</strong> Nollywood FilmsFigure 2. A scene from The K<strong>in</strong>gmaker set at O’Jez Nightclub, <strong>Lagos</strong>.National Stadium. The stadium itself <strong>is</strong> a hulk<strong>in</strong>g ru<strong>in</strong>, <strong>the</strong> field overgrown,<strong>the</strong> equipment ripped out and carried away by thieves, and <strong>the</strong> environshaunted by armed robbers, but O’Jez’s <strong>is</strong> spruce and hums with activity,a suitable home for a vibrant, r<strong>is</strong><strong>in</strong>g pr<strong>of</strong>essional community: it has goodsound and light systems; and downstairs <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> courtyard, film people carryon animated conversations over tables crowded with beer bottles, peppersoup, and cellphones (figure 2).The exhibition sector <strong>of</strong> Nollywood <strong>is</strong> peculiarly hard to see. Vide<strong>of</strong>ilms are commonly (if confus<strong>in</strong>gly, for Americans) called “home videos” <strong>in</strong>Nigeria, because <strong>that</strong> <strong>is</strong> where <strong>the</strong>y are normally viewed: <strong>in</strong> domestic space,away from <strong>the</strong> public eye. The horrendous crime rates and general breakdown<strong>of</strong> public order <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1990s was an essential condition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> videoboom: go<strong>in</strong>g out to <strong>the</strong>aters at night became too dangerous. The <strong>the</strong>aters<strong>in</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong> all closed; many were turned <strong>in</strong>to churches or warehouses. A fewgleam<strong>in</strong>g multiplexes have appeared recently, but <strong>the</strong>y show American <strong>films</strong>.At <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> social spectrum, small video parlors serve <strong>the</strong> poor,<strong>of</strong>fer<strong>in</strong>g access to Nollywood via a wooden bench and a video monitor. Thosewho can<strong>not</strong> afford <strong>the</strong> very modest entrance fee for a video parlor ga<strong>the</strong>r onstreet corners to watch <strong>the</strong> monitors set up on vendors’ stalls (Okome 2007).Newly released <strong>films</strong> may be screened <strong>in</strong> rented public spaces rang<strong>in</strong>g fromuniversity auditoriums to <strong>the</strong> most elegant cultural venues <strong>in</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong>. Filmfestivals and award ceremonies are becom<strong>in</strong>g regular occurrences and attract

glitter<strong>in</strong>g crowds to fancy places, but <strong>the</strong>se are fleet<strong>in</strong>g occasions; <strong>the</strong> <strong>films</strong>are <strong>not</strong> at home <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>se places.Telev<strong>is</strong>ion stations broadcast <strong>films</strong> <strong>in</strong>to homes and frequently showtrailers. A capillary d<strong>is</strong>tribution system serves a d<strong>is</strong>persed audience <strong>of</strong> workersas <strong>the</strong>y return home: small shops and street stalls sell <strong>films</strong>; even morepeople patronize thousands <strong>of</strong> video rental shops. Film posters decorate <strong>the</strong>seestabl<strong>is</strong>hments and are plastered anywhere <strong>the</strong>y will stick—a ubiquitouselement <strong>of</strong> v<strong>is</strong>ual street culture. These are fairly small posters: <strong>the</strong> smallbudgets <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>films</strong>, <strong>the</strong> <strong>not</strong>orious reluctance <strong>of</strong> marketers to spend muchon publicity, and a scarcity <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ters <strong>that</strong> can produce large posters mean<strong>that</strong> billboard-sized images are rare, and <strong>the</strong> absence <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>aters means anabsence <strong>of</strong> marquee-sized spaces to fill.Like <strong>the</strong> jackets <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> video cassettes and video compact d<strong>is</strong>cs, <strong>the</strong>posters provide splashes <strong>of</strong> vivid color <strong>in</strong> an <strong>of</strong>ten dreary cityscape. Theyare normally identical or closely related to <strong>the</strong> jackets—which <strong>is</strong> to say<strong>the</strong>y are designed to work on a small scale. Their function <strong>is</strong> to scream forattention <strong>in</strong> a saturated market. Almost <strong>in</strong>variably <strong>the</strong>y are crowded withactors’ faces. As <strong>in</strong> any commercial c<strong>in</strong>ema culture, a star system <strong>is</strong> responsiblefor sell<strong>in</strong>g <strong>films</strong>, and for an audience <strong>of</strong> uncerta<strong>in</strong> literacy, faces servebetter than names. Posters and jackets are always mechanically reproduced;<strong>the</strong>re <strong>is</strong> <strong>not</strong>h<strong>in</strong>g like <strong>the</strong> tradition <strong>of</strong> “folk art” film posters <strong>in</strong> Ghana (Wolfe2000). The need for small but recognizable images <strong>of</strong> specific actors woulditself d<strong>is</strong>courage hand pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g, and <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dustrial scale and rate <strong>of</strong> Nollywoodfilm production requires mechanical reproduction. In any case, naïvefolk art runs counter to <strong>the</strong> ethos and aspiration <strong>of</strong> Nollywood. Liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>Bondage 1 <strong>is</strong> considered <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>augural film <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> video boom, <strong>not</strong> becauseit was <strong>the</strong> first Nigerian feature film on video, but because it was <strong>the</strong> firstto be packaged <strong>in</strong> a full-color pr<strong>in</strong>ted jacket and wrapped <strong>in</strong> cellophane,like an imported American or Indian film (Madu Chikwendu, personalcommunication; Haynes 2007) (see color <strong>in</strong>sert 6).Video compact d<strong>is</strong>cs are becom<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> dom<strong>in</strong>ant medium for Nollywood<strong>films</strong> <strong>in</strong> Nigeria. The v<strong>is</strong>ual quality <strong>of</strong> VCDs <strong>is</strong> poorer than <strong>that</strong> <strong>of</strong>DVDs; it <strong>is</strong> about <strong>the</strong> same as <strong>that</strong> <strong>of</strong> a pr<strong>is</strong>t<strong>in</strong>e VHS tape, but considerablybetter than <strong>that</strong> <strong>of</strong> a videotape <strong>that</strong> has spent a week out <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> tropical sunon a hawker’s shelf and <strong>is</strong> <strong>the</strong>n played on a mach<strong>in</strong>e full <strong>of</strong> Harmattan dust.Brian Lark<strong>in</strong> observes <strong>that</strong> <strong>the</strong>ories <strong>of</strong> media generally assume <strong>that</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir<strong>in</strong>frastructures work perfectly—which <strong>is</strong> far from <strong>the</strong> case <strong>in</strong> Nigeria, whereaudiences experience <strong>films</strong> by way <strong>of</strong> “cheap tape recorders, old telev<strong>is</strong>ions,videos <strong>that</strong> are <strong>the</strong> copy <strong>of</strong> a copy <strong>of</strong> a copy to <strong>the</strong> extent <strong>that</strong> <strong>the</strong> image <strong>is</strong>permanently blurred, <strong>the</strong> sound resolutely opaque” (Lark<strong>in</strong> 2004:314). Th<strong>is</strong>technology <strong>is</strong> embedded <strong>in</strong> liv<strong>in</strong>g rooms shared with cry<strong>in</strong>g babies, or <strong>in</strong>video parlors full <strong>of</strong> shout<strong>in</strong>g adolescents—social environments <strong>that</strong> shapeand color <strong>the</strong> experience <strong>of</strong> film view<strong>in</strong>g (Lark<strong>in</strong> 2000, 2002, and forthcom<strong>in</strong>g).The whole bus<strong>in</strong>ess <strong>is</strong> subject to <strong>the</strong> vagaries <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> electrical powergrid, which has been deteriorat<strong>in</strong>g for decades and <strong>is</strong> commonly described as“epileptic.” Blackouts are unpredictable but rout<strong>in</strong>e and <strong>of</strong>ten long-last<strong>in</strong>g,africa today 137 Jonathan Haynes

and when <strong>the</strong> electricity goes <strong>of</strong>f, <strong>the</strong> images d<strong>is</strong>appear, except <strong>in</strong> homes withgenerators powerful enough to run video equipment as well as a refrigeratorand lights. Mov<strong>in</strong>g pictures are evanescent by nature; <strong>in</strong> Nigeria, <strong>the</strong>yhave a particularly lurch<strong>in</strong>g, fragile ex<strong>is</strong>tence. Nollywood <strong>films</strong> have littlesupport<strong>in</strong>g material culture around <strong>the</strong>m, and so when <strong>the</strong> electricity goes<strong>of</strong>f, <strong>the</strong>re <strong>is</strong> <strong>not</strong> much to look at. Still <strong>the</strong>y shape <strong>the</strong> national imag<strong>in</strong>ation,build<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir empire <strong>in</strong> people’s heads.africa today 138 Nollywood <strong>in</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong>, <strong>Lagos</strong> <strong>in</strong> Nollywood Films<strong>Lagos</strong> <strong>in</strong> Nollywood <strong>films</strong>The urban scene <strong>is</strong> fundamental <strong>in</strong> Nigerian <strong>films</strong> (Okome 2003). Not allNollywood <strong>films</strong> are set <strong>in</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong>, 2 but Nollywood <strong>is</strong> <strong>in</strong>conceivable withoutit—its personality, dynam<strong>is</strong>m, <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>ite aston<strong>is</strong>h<strong>in</strong>g stories, and gar<strong>is</strong>hglamour—and <strong>Lagos</strong> <strong>is</strong> <strong>the</strong> most common sett<strong>in</strong>g.The first th<strong>in</strong>g to say about how <strong>Lagos</strong> appears on screen <strong>is</strong> <strong>that</strong> it doesso <strong>in</strong> various gu<strong>is</strong>es <strong>in</strong> thousands <strong>of</strong> <strong>films</strong>, reflect<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> size and complexity<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> city and <strong>the</strong> film <strong>in</strong>dustry. The videos are at home at nearly all sociallevels, and some directors (e.g., Chico Ejiro) and directors <strong>of</strong> photography(e.g., Jonathan Gbemutuor) have d<strong>is</strong>t<strong>in</strong>ctive v<strong>is</strong>ual styles. Still, <strong>the</strong> <strong>films</strong>share strong commonalities—<strong>not</strong> because <strong>the</strong>y are <strong>the</strong> products <strong>of</strong> a consolidatedmass-culture <strong>in</strong>dustry mobiliz<strong>in</strong>g large amounts <strong>of</strong> capital to delivera standardized product, and <strong>not</strong> because <strong>the</strong>y are shaped <strong>in</strong> any significantway by government <strong>in</strong>fluence: 3 <strong>the</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>films</strong> <strong>is</strong> a collectively producedrepresentation because <strong>the</strong> film <strong>in</strong>dustry <strong>is</strong> heavily imitative andgeneric—which <strong>is</strong> <strong>the</strong> generative structure <strong>of</strong> African popular culture andits commercial bas<strong>is</strong> (Barber 1987, 2000; Haynes and Okome 1998). Materialconditions impose certa<strong>in</strong> features on nearly all <strong>films</strong>. Location shoot<strong>in</strong>g—one <strong>of</strong> those features—creates a common real<strong>is</strong>m, a mass <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terchangeable,conventionally framed shots <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong> streets and compounds, lav<strong>is</strong>hparlors and ord<strong>in</strong>ary bedrooms, hospitals, and <strong>of</strong>fices. Common desires lard<strong>the</strong> <strong>films</strong> with standard images <strong>of</strong> luxury automobiles, huge houses, andexpensive clo<strong>the</strong>s. Common fears take v<strong>is</strong>ible form by employ<strong>in</strong>g familiargeneric resources—melodrama, crime film, and various conventional means<strong>of</strong> represent<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> supernatural.The <strong>films</strong> are made so fast (shoot<strong>in</strong>g typically takes about two weeks,and <strong>of</strong>ten less), on such m<strong>in</strong>uscule budgets, and under such unrelent<strong>in</strong>gcommercial pressures, <strong>that</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual art<strong>is</strong>ts have few resources and littletime to realize a d<strong>is</strong>t<strong>in</strong>ctive v<strong>is</strong>ion. “Art directors” now sometimes appear<strong>in</strong> film credits, but <strong>the</strong> ability to control <strong>the</strong> look <strong>of</strong> a film <strong>is</strong> limited. Allshoot<strong>in</strong>g <strong>is</strong> done on location because, as <strong>not</strong>ed earlier, Nollywood does <strong>not</strong>have <strong>the</strong> capital to construct its own spaces. Interior scenes are shot <strong>in</strong>houses borrowed for a few days, so <strong>the</strong> color <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> walls beh<strong>in</strong>d an actorcan<strong>not</strong> be changed. Nollywood <strong>films</strong> have acquired enough social prestige<strong>that</strong> wealthy people like to have <strong>the</strong>ir houses featured <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>m, but <strong>the</strong>crews are <strong>the</strong>re on sufferance and have no real rights. Light<strong>in</strong>g <strong>is</strong> a neglected

art, seldom used creatively; filmmakers th<strong>in</strong>k <strong>the</strong>y can get along without itbecause <strong>the</strong>ir video cameras are good at pick<strong>in</strong>g up ambient light. Thoughdirectors are accused <strong>of</strong> lik<strong>in</strong>g to create traffic jams (Nebo 2000:52–53),<strong>the</strong>ir ability to control <strong>the</strong> life <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong> streets <strong>is</strong> precarious at best. Time <strong>is</strong>as hard to control as space: film narratives rout<strong>in</strong>ely sprawl across generations,but <strong>the</strong>y never attempt to reproduce <strong>the</strong> look <strong>of</strong> a h<strong>is</strong>torical periodo<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>the</strong> present. Budgetary reasons are doubtless overwhelm<strong>in</strong>glyresponsible for <strong>the</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> h<strong>is</strong>torical ver<strong>is</strong>imilitude, and aga<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>abilityto control space <strong>is</strong> significant: <strong>the</strong>re <strong>is</strong> no back lot on which to construct aperiod street, and even a room where period props could be stored may bedifficult to come by. 4The v<strong>is</strong>ual dimension, compared with dialog and narrative, <strong>is</strong> lessimportant <strong>in</strong> Nigerian video <strong>films</strong> than it <strong>is</strong> <strong>in</strong> most c<strong>in</strong>ema cultures. Themost highly developed arguments about <strong>the</strong> v<strong>is</strong>ual aspect <strong>of</strong> African <strong>films</strong>—chiefly <strong>the</strong> work <strong>of</strong> a l<strong>in</strong>e <strong>of</strong> Francophone critics (Barlet 2000; Gardies 1989;Gardies and Haffner 1987) th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g perhaps primarily <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> stark Sahelianlandscapes <strong>in</strong> <strong>films</strong> from Senegal, Mali, Burk<strong>in</strong>a Faso, and Niger—havestressed <strong>the</strong> image as <strong>the</strong> carrier <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>ound symbolic, social, and politicalmean<strong>in</strong>gs. The importance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> image <strong>is</strong> emphasized by slow pac<strong>in</strong>g andan envelop<strong>in</strong>g silence. Silence <strong>is</strong> <strong>the</strong> essential <strong>ground</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Mand<strong>in</strong>go <strong>sense</strong><strong>of</strong> art and language (Barlet 2000:145), but <strong>the</strong> coastal peoples <strong>of</strong> Nigeria areexceptionally voluble, and <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>films</strong> tend to be crowded, frenetic, and no<strong>is</strong>y,like <strong>the</strong> film posters, cassette jackets, and <strong>Lagos</strong> itself. Nollywood <strong>films</strong> aretailored to <strong>the</strong> small, low-resolution screens on which <strong>the</strong>y appear. They arenarrative-driven and talky, like <strong>the</strong> soap operas (both domestic and imported)and Lat<strong>in</strong> American telenovelas which make up a large part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir DNA. As<strong>the</strong> director Don Pedro Obaseki says, Nigerian video <strong>films</strong> were born <strong>of</strong> telev<strong>is</strong>ion,<strong>not</strong> c<strong>in</strong>ema, <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir personnel (many <strong>of</strong> whom came fromtelev<strong>is</strong>ion soap operas), aes<strong>the</strong>tics, and video technology (Obaseki 2005). In<strong>the</strong>ir early days, nearly all Nigerian video <strong>films</strong> had a d<strong>is</strong>t<strong>in</strong>ctively leaden,slow-mov<strong>in</strong>g quality; many still do, but on <strong>the</strong> whole, <strong>the</strong>y have evolved <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> direction <strong>of</strong> a br<strong>is</strong>ker, <strong>in</strong>ternational pr<strong>of</strong>essional style <strong>of</strong> shoot<strong>in</strong>g andedit<strong>in</strong>g. Th<strong>is</strong> movement tends to underm<strong>in</strong>e arguments for an essentialAfrican film language and to encourage us to see practical reasons for some<strong>of</strong> its supposed features. A static medium shot <strong>is</strong> an easier way to capture aconversation than <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational standard shot-reverse-shot pattern, forexample, if one <strong>is</strong> work<strong>in</strong>g with one camera and actors who are improv<strong>is</strong><strong>in</strong>gfrom a scenario, ra<strong>the</strong>r than recit<strong>in</strong>g l<strong>in</strong>es from a script.Nollywood <strong>films</strong> are full <strong>of</strong> close-ups because <strong>the</strong>y are made for telev<strong>is</strong>ionscreens. It <strong>is</strong> fundamentally a c<strong>in</strong>ema <strong>of</strong> faces, which need to be seen <strong>in</strong>close-up because we need to see <strong>the</strong> tears stream<strong>in</strong>g down <strong>the</strong>m or o<strong>the</strong>rw<strong>is</strong>eget close to <strong>the</strong> emotions generated by almost <strong>in</strong>variably melodramatic plots(Haynes 2000:22–29). Th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> an aes<strong>the</strong>tic <strong>of</strong> immediate impact, plung<strong>in</strong>gus <strong>in</strong>to each moment and milk<strong>in</strong>g it for everyth<strong>in</strong>g it <strong>is</strong> worth, ra<strong>the</strong>r thansubord<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g every element <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> film to an overall <strong>sense</strong> <strong>of</strong> design (Barber1987:46–48; Barrot 2005). There <strong>is</strong> some truth <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> frequently repeatedafrica today 139 Jonathan Haynes

africa today 140 Nollywood <strong>in</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong>, <strong>Lagos</strong> <strong>in</strong> Nollywood Films<strong>not</strong>ion about African c<strong>in</strong>ema favor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> collective and <strong>the</strong>refore preferr<strong>in</strong>gmedium shots to close-ups, but <strong>the</strong> Igbo and Yoruba and o<strong>the</strong>r sou<strong>the</strong>rnNigerian cultures <strong>that</strong> underlie Nollywood <strong>films</strong> place strong emphas<strong>is</strong> on<strong>in</strong>dividual<strong>is</strong>m—<strong>in</strong>dividual dynam<strong>is</strong>m, <strong>in</strong>dividual dest<strong>in</strong>y, self-realizationthrough <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dependent pursuit <strong>of</strong> money (on <strong>the</strong> Yoruba, see Barber 2000and Barber and Waterman 1995). <strong>Lagos</strong> <strong>is</strong> <strong>not</strong>oriously a place where all forms<strong>of</strong> social solidarity break down, leav<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dividuals struggl<strong>in</strong>g for <strong>the</strong>ir survivaland advancement, each aga<strong>in</strong>st all (Oha 2001). The close-up carries<strong>the</strong>se mean<strong>in</strong>gs.Objects are also frequently shot <strong>in</strong> close-up, commodity fet<strong>is</strong>h<strong>is</strong>mclearly motivat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> l<strong>in</strong>ger<strong>in</strong>g, even lascivious camerawork. When <strong>the</strong>camera repeatedly returns to <strong>the</strong> label on a bottle <strong>of</strong> w<strong>in</strong>e (Glamour Girls2), product placement <strong>is</strong> doubtless <strong>in</strong>volved. Most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> luxury objects—clo<strong>the</strong>s, cars, houses—are borrowed from shops, car dealerships, or <strong>in</strong>dividuals.Wealth <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> most tangible, desired forms <strong>is</strong> fundamental to <strong>the</strong> lure<strong>of</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong> and <strong>is</strong> at <strong>the</strong> heart <strong>of</strong> Nollywood imagery and <strong>the</strong>matics. “It’s nowI know I have come to <strong>Lagos</strong>!” crows a mercenary woman who has f<strong>in</strong>allygotten a man to give her a new car <strong>in</strong> Liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Bondage 2.The <strong>films</strong> never<strong>the</strong>less pull back to give us <strong>the</strong> larger picture <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> city, and <strong>the</strong> real<strong>is</strong>m <strong>that</strong> comes with location shoot<strong>in</strong>g compensatesfor many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> limitations d<strong>is</strong>cussed above. Everyth<strong>in</strong>g we see <strong>is</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong>,both what <strong>the</strong> camera <strong>is</strong> focus<strong>in</strong>g on, and what we can see over <strong>the</strong> actors’shoulders—which <strong>is</strong> <strong>of</strong>ten tremendously reveal<strong>in</strong>g. Of course <strong>the</strong>se imagesare shaped, part <strong>of</strong> a project <strong>of</strong> representation. It <strong>is</strong> <strong>not</strong> easy to imag<strong>in</strong>e orpicture th<strong>is</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gularly <strong>in</strong>coherent city.As Mat<strong>the</strong>w Gandy writes, <strong>Lagos</strong> from its orig<strong>in</strong>s has been markedby extreme <strong>in</strong>come <strong>in</strong>equality and a conceptual split between <strong>the</strong> colonial/European/modern/world city and <strong>the</strong> “native” areas, left to fend for <strong>the</strong>mselvesunder <strong>the</strong> presumed authority <strong>of</strong> “tradition” because, <strong>in</strong> fact, <strong>the</strong>city’s rulers had no <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> pay<strong>in</strong>g for a comprehensive urban <strong>in</strong>frastructure.By now, only a t<strong>in</strong>y proportion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> city functions as an <strong>in</strong>tegratedmetropol<strong>is</strong>: <strong>the</strong> percentage <strong>of</strong> households connected to <strong>the</strong> piped watersystem has fallen from 10 percent <strong>in</strong> 1960 to 5 percent now; only 1 percentare connected to a closed sewer system. In <strong>the</strong> absence <strong>of</strong> any real pretenseat <strong>the</strong> prov<strong>is</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> municipal services, <strong>the</strong> population lives <strong>in</strong> atomizedunits, at every social level. The wealthy build walled compounds with <strong>the</strong>irown security guards, boreholes for water, and generators. In middle-classneighborhoods (such as Surulere and Ikeja, where <strong>the</strong> film producers arebased) <strong>the</strong> streets are gated and manned by neighborhood-supported securityguards <strong>in</strong> an attempt to fend <strong>of</strong>f gangs <strong>of</strong> armed robbers. The poor, left to<strong>the</strong>ir own devices <strong>in</strong> two hundred slums spread throughout <strong>the</strong> city, have nosuch physical security. Remnants <strong>of</strong> collective forms <strong>of</strong> social organizationma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> some order, but as (for <strong>in</strong>stance) traditional conceptions <strong>of</strong> whoseresponsibility it <strong>is</strong> to keep a shared compound clean break down, trash pilesup. “Traditional rulers” <strong>of</strong> various k<strong>in</strong>ds exert <strong>in</strong>fluence; normally, <strong>the</strong>irroles have become highly exploitative. Functions such as prov<strong>is</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> water

are <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> hands <strong>of</strong> even more predatory figures, who charge exorbitant feesand block moves to provide runn<strong>in</strong>g water because it would reduce <strong>the</strong>irbus<strong>in</strong>ess. As Gandy emphasizes, <strong>the</strong>re <strong>is</strong> an ideological vacuum where <strong>the</strong>reshould be a public sphere, or ra<strong>the</strong>r a spl<strong>in</strong>ter<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to ethnic and religiousextrem<strong>is</strong>ms and <strong>the</strong> pursuit <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual advancement through patronagenetworks, strategies <strong>that</strong> prom<strong>is</strong>e a measure <strong>of</strong> control over immediateenvironments <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> face <strong>of</strong> an admittedly <strong>in</strong>tractable whole. Th<strong>is</strong> means<strong>that</strong> <strong>the</strong> situation <strong>is</strong> likely to stay <strong>the</strong> same because <strong>the</strong>re <strong>is</strong> <strong>in</strong>sufficientpolitical pressure to br<strong>in</strong>g about <strong>the</strong> needed enormous <strong>in</strong>vestments <strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>frastructure. It also means <strong>that</strong> coherence <strong>is</strong> hard to achieve, even on <strong>the</strong>conceptual level, ei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong> popular consciousness, or at <strong>the</strong> urban-plann<strong>in</strong>glevel (Gandy 2006).Of course almost every African city <strong>is</strong> a mess; <strong>Lagos</strong> <strong>is</strong> only <strong>the</strong> biggest.The two–cities-<strong>of</strong>-colonial<strong>is</strong>m <strong>the</strong>me was articulated <strong>in</strong> classic formby Frantz Fanon <strong>in</strong> The Wretched <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Earth (1968), and Roy Armes hasshown how it <strong>in</strong>forms <strong>the</strong> treatment <strong>of</strong> space <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> symbolically found<strong>in</strong>gfilm <strong>of</strong> African c<strong>in</strong>ema, Ousmane Sembene’s Borom Sarret (Malkmus andArmes 1991:186–187). Franço<strong>is</strong>e Pfaff <strong>in</strong>troduces a study <strong>of</strong> “African Citiesas C<strong>in</strong>ematic Texts” <strong>in</strong> Francophone African celluloid filmmak<strong>in</strong>g by say<strong>in</strong>g“Nowhere but <strong>in</strong> contemporary African cities <strong>is</strong> <strong>the</strong> clash between traditionand modernity better expressed. And it <strong>is</strong> prec<strong>is</strong>ely <strong>the</strong> dramatic rendition<strong>of</strong> th<strong>is</strong> <strong>the</strong>me <strong>that</strong> lies at <strong>the</strong> core <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> greatest number <strong>of</strong> African <strong>films</strong>,especially those set <strong>in</strong> urban contexts” (Pfaff 2004:89).It <strong>is</strong> possible to f<strong>in</strong>d Nollywood <strong>films</strong> <strong>in</strong> which a polarity between“tradition” and “modernity” <strong>is</strong> operat<strong>in</strong>g, but th<strong>is</strong> polarity does <strong>not</strong> structure<strong>the</strong> imagery <strong>of</strong> Nollywood <strong>films</strong> <strong>in</strong> general. The architecture and monumentsassociated with colonial<strong>is</strong>m <strong>that</strong> Pfaff f<strong>in</strong>ds so prevalent are almost entirelyabsent; <strong>the</strong> population <strong>of</strong> Nollywood, as <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong>, <strong>is</strong> young and does <strong>not</strong>remember <strong>the</strong> colonial era. The high end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong> cityscape was formedby <strong>the</strong> era <strong>of</strong> oil-boom-fueled heroic national aspiration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1960s and1970s, with its freeways and grandiose public build<strong>in</strong>gs, and <strong>the</strong> era <strong>of</strong> neoliberalkleptocracy <strong>that</strong> followed. Money, ra<strong>the</strong>r than race, has for decades been<strong>the</strong> structur<strong>in</strong>g pr<strong>in</strong>ciple, and though class div<strong>is</strong>ions are exceptionally sharpand v<strong>is</strong>ible <strong>in</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong>, <strong>the</strong>y are permeable (Olaniyan 2004:89–90)—doubtlessmuch more permeable <strong>in</strong> imag<strong>in</strong>ation than <strong>in</strong> reality, and Nollywood <strong>is</strong> allabout sell<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> dream <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual advancement. As has been frequentlyobserved, <strong>the</strong> hope <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual advancement has been a formidable obstacleto <strong>the</strong> formation <strong>of</strong> class consciousness <strong>in</strong> Nigeria (Barber 1987; Jeyifo 1984;Waterman 1990; Williams 1974). Wealthy neighborhoods are now desired,ra<strong>the</strong>r than seen under <strong>the</strong> sign <strong>of</strong> exclusion, alienation, and d<strong>is</strong>orientation,as <strong>in</strong> Borom Sarret. 5 Rich and poor coex<strong>is</strong>t on <strong>in</strong>timate terms <strong>in</strong> a state<strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>complete class formation. Many extended families <strong>in</strong>clude someonewith money, or at least a relationship with a wealthy patron; no extendedfamily <strong>is</strong> without many poor relations. Hopes for spectacular social promotionand fear <strong>of</strong> social collapse are almost universal and are <strong>the</strong> essentialsocioemotional matrix <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> images <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>films</strong>.africa today 141 Jonathan Haynes

africa today 142 Nollywood <strong>in</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong>, <strong>Lagos</strong> <strong>in</strong> Nollywood FilmsThere <strong>is</strong> immense wealth <strong>in</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong>. Between 1971 and 2006, Nigeriaearned more than $400 billion <strong>in</strong> oil revenues, <strong>of</strong> which an estimated$50–100 billion was siphoned <strong>of</strong>f through fraud and corruption; between2006 and 2020, <strong>the</strong> country <strong>is</strong> expected to make $750 billion more (Lubeck,Watts, and Lipschutz 2007:5, 7). Much or most <strong>of</strong> th<strong>is</strong> money has flowedabroad, rapidly, or gone elsewhere <strong>in</strong> Nigeria, but <strong>Lagos</strong> has gotten morethan its share, and it <strong>is</strong>, with <strong>the</strong> new political capital, Abuja, <strong>the</strong> preem<strong>in</strong>entshowcase for wealth. No amount <strong>of</strong> money, however, can buy completesegregation from ambient m<strong>is</strong>ery and danger. Unlike o<strong>the</strong>r megacities—suchas Bombay, Dhaka, Manila, and São Paulo, which concentrate <strong>the</strong>ir poor<strong>in</strong> d<strong>is</strong>crete satellite cities—<strong>Lagos</strong> has poverty <strong>that</strong> permeates all but a fewenclaves (Packer 2006:68). Almost all streets have broken surfaces and arebordered by trash, open sewers, and petty commerce. No street <strong>is</strong> safe fromdaylight armed robbery and carjack<strong>in</strong>g. All th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> v<strong>is</strong>ible as a camera tracksa fancy SUV through <strong>Lagos</strong>. Tejumola Olaniyan gives an example <strong>of</strong> howdifficult it <strong>is</strong> to produce an exclusive image:Dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> reign <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>famous dark-goggled tyrant GeneralSani Abacha (November 1993–June 1998), h<strong>is</strong> propagandamach<strong>in</strong>e produced a video, Nigeria: World Citizen, to burn<strong>is</strong>hh<strong>is</strong> image and <strong>the</strong> image <strong>of</strong> Nigeria he had dragged <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong>mud. The clips <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong> <strong>that</strong> appeared <strong>in</strong> it were all high-angleshots <strong>of</strong> tower<strong>in</strong>g skyscrapers. The vertigo <strong>in</strong>duced immediatelytells you <strong>that</strong> someth<strong>in</strong>g <strong>is</strong> am<strong>is</strong>s far before you are ableto make <strong>sense</strong> <strong>of</strong> it: conventional eye-level shots <strong>that</strong> wouldhave shown people on <strong>the</strong> streets are m<strong>is</strong>s<strong>in</strong>g. Yes, <strong>the</strong> dirt on<strong>Lagos</strong> streets <strong>is</strong> so legendary <strong>that</strong> it subverts any attempt toperfume it over by propaganda. (Olaniyan 2004:101)But Nollywood has found ways to romanticize <strong>the</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong> cityscape,chiefly by pull<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> camera far back for establ<strong>is</strong>h<strong>in</strong>g shots <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fancier,greener residential areas <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> city, or <strong>the</strong> skyl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>of</strong> high-r<strong>is</strong>e build<strong>in</strong>gs on<strong>Lagos</strong> Island. A favorite shot—<strong>is</strong> it actually <strong>the</strong> same one, recycled from filmto film?—<strong>is</strong> taken from a tall build<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Ikoyi, look<strong>in</strong>g over Five CowriesCreek to <strong>the</strong> exclusive realm <strong>of</strong> Victoria Island. Ano<strong>the</strong>r common solution<strong>is</strong> to shoot at night, when lights sparkle and darkness hides <strong>the</strong> squalor.Improbably, traffic on <strong>the</strong> freeways and major streets provides images <strong>of</strong>urban glamour and mobility (Tears for Love); aga<strong>in</strong>, shoot<strong>in</strong>g at night helps(Dead End). The <strong>not</strong>orious <strong>Lagos</strong> traffic jams never appear (Haynes 2006).These establ<strong>is</strong>h<strong>in</strong>g shots seem to be emulat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> look <strong>of</strong> Hollywood <strong>films</strong>,and <strong>the</strong>y <strong>of</strong>ten occur <strong>in</strong> romantic <strong>films</strong> or at romantic moments to providean image <strong>of</strong> a desired good life <strong>in</strong> a normal city (Violated 1).Particular iconic build<strong>in</strong>gs are seldom featured (cf. Pfaff 2004). Politically,th<strong>is</strong> doubtless reflects <strong>the</strong> fact <strong>that</strong> Nigeria was under military ruledur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> r<strong>is</strong>e <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> video <strong>films</strong>, and filmmakers were understandablycautious about stick<strong>in</strong>g a camera <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> rulers’ faces, even if <strong>the</strong>y had been

allowed to do so. In any case, until 1991, political power was centered <strong>in</strong>Dodan Barracks on <strong>Lagos</strong> Island, which presents a blank wall to <strong>the</strong> city,and <strong>the</strong>n moved to <strong>the</strong> new capital, where <strong>the</strong> videos have a weak foothold.Public <strong>in</strong>stitutions do <strong>not</strong> function, as everyone knows well, so <strong>the</strong>re <strong>is</strong> littlereason to show <strong>the</strong>m. Economic power spr<strong>in</strong>gs from <strong>the</strong> oil wellheads <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>Niger Delta and <strong>the</strong>n cascades through myriad, <strong>of</strong>ten secret networks. Thevideos represent th<strong>is</strong> sort <strong>of</strong> wealth through totaliz<strong>in</strong>g shots <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> whole<strong>Lagos</strong> skyl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>of</strong> tall build<strong>in</strong>gs, or through more or less randomly chosenexamples <strong>of</strong> sleek <strong>of</strong>fice build<strong>in</strong>gs and extravagant mansions with fancifulcurved concrete work <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> modern Nigerian style. The videos havean obsessive <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> people who tap <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> sources <strong>of</strong> wealth—<strong>the</strong>irhouses, parties, and cars. Film cultures everywhere give d<strong>is</strong>proportionateattention to <strong>the</strong> élite, <strong>of</strong> course; here, social turbulence, moral spectacle,and cynical political analys<strong>is</strong> are an <strong>in</strong>tegral part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> v<strong>is</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> a privilegedlifestyle. As Pierre Barrot acutely observes, though Nollywood frankly aimsat be<strong>in</strong>g an enterta<strong>in</strong>ment <strong>in</strong>dustry, it does <strong>not</strong> turn away from <strong>the</strong> “wounds”<strong>of</strong> society, as (for <strong>in</strong>stance) <strong>the</strong> far more escap<strong>is</strong>t Lat<strong>in</strong> American telenovelasdo: on <strong>the</strong> contrary, Nollywood deals with <strong>the</strong>se <strong>is</strong>sues constantly (Barrot2005:64–65).The ambient chaos <strong>is</strong> apt to show around <strong>the</strong> edges <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> image unlesscare <strong>is</strong> taken to exclude it; even <strong>that</strong> establ<strong>is</strong>h<strong>in</strong>g shot from a tall build<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> Ikoyi, if it pans <strong>in</strong>land to <strong>the</strong> streets below, may seem to develop anexploratory quality (Illegal Bro<strong>the</strong>rs), though Nollywood shies away from<strong>the</strong> tendentious shots <strong>of</strong> garbage piles and traffic jams <strong>that</strong> are irres<strong>is</strong>tible t<strong>of</strong>oreign documentary filmmakers (Suffer<strong>in</strong>g and Smil<strong>in</strong>g). These realities aretoo familiar to need comment; people watch movies to see someth<strong>in</strong>g else.The social anxieties <strong>that</strong> underlie most Nollywood <strong>films</strong> are apt tobe expressed less through direct, social real<strong>is</strong>t images <strong>of</strong> social chaos ordanger than through <strong>the</strong> plots, which <strong>of</strong>ten follow savage campaigns forsocial advancement <strong>that</strong> take a toll on <strong>in</strong>nocent victims or illustrate socialprecariousness through tales <strong>of</strong> families ru<strong>in</strong>ed by unemployment, hospitalbills, or <strong>the</strong> death <strong>of</strong> a breadw<strong>in</strong>ner which makes it impossible to pay schoolfees (Haynes 2002). Such stories take place mostly <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> standard <strong>in</strong>teriorspaces <strong>of</strong> homes, <strong>of</strong>fices, and hospitals, but <strong>the</strong>y may culm<strong>in</strong>ate by melodramaticallydump<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir protagon<strong>is</strong>ts out <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> streets, where <strong>the</strong>y searchva<strong>in</strong>ly for work (Dy<strong>in</strong>g for <strong>the</strong> Nation; Shame), a lost child (Onome 2), or apatron (Dry Leaves), solicit as a prostitute (Domitilla), sit amid householdfurniture after be<strong>in</strong>g evicted (Died Wretched), or eat garbage as a rav<strong>in</strong>glunatic (Liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Bondage 2).The dangers <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong> life are imaged directly <strong>in</strong> crime <strong>films</strong>, which are<strong>of</strong>ten topical and generally respond to anxieties about violent crime. Some<strong>films</strong> <strong>in</strong> th<strong>is</strong> genre convey <strong>the</strong> terror <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> denizens <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong> with grittyreal<strong>is</strong>m; o<strong>the</strong>rs sympa<strong>the</strong>tically—and melodramatically—explore <strong>the</strong> socialpressures <strong>that</strong> produce crim<strong>in</strong>als (Owo Blow; Rattlesnake); o<strong>the</strong>rs seem tobe constructed mostly out <strong>of</strong> recycled <strong>in</strong>ternational film culture. Variousstrands <strong>of</strong> iconography have been developed: images <strong>of</strong> gangsters modeledafrica today 143 Jonathan Haynes

africa today 144 Nollywood <strong>in</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong>, <strong>Lagos</strong> <strong>in</strong> Nollywood Filmspartly on actually ex<strong>is</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Lagos</strong> “area boys” and partly on American andCh<strong>in</strong>ese (Bloody M<strong>is</strong>sion) <strong>films</strong>; 6 equally menac<strong>in</strong>g vigilantes, based closelyon <strong>the</strong> black-clad, amulet-wear<strong>in</strong>g Bakassi Boys, who operated <strong>in</strong> easternNigeria around 2000 (McCall 2004); and slicker, frankly Americanized actionfilm heroes revel<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> high-tech gear and deal<strong>in</strong>g with <strong>in</strong>ternational conspiracies<strong>in</strong> clean, modern landscapes <strong>that</strong> hardly ex<strong>is</strong>t <strong>in</strong> Nigeria (Blue Sea,State <strong>of</strong> Emergency). There have been some highly eroticized treatments <strong>of</strong>gangsters, both male (Rattlesnake) and female (Outkast). Filmmakers areapprentic<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>mselves to <strong>the</strong> arts <strong>of</strong> American film violence, but <strong>the</strong>irbudgets sharply limit what <strong>the</strong>y can shoot up or blow up. I believe Rituals(1997) <strong>is</strong> <strong>the</strong> first Nigerian film <strong>in</strong> which a car <strong>is</strong> destroyed—a landmark for<strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dustry.Half <strong>the</strong> population <strong>of</strong> <strong>Lagos</strong> lives on a dollar a day, and <strong>the</strong>se people do<strong>not</strong> get proportional screen time <strong>in</strong> Nollywood <strong>films</strong>, but Nigerian filmmakersare on easy and <strong>in</strong>timate terms with <strong>the</strong> life <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> poor. The low-budgetreal<strong>is</strong>m <strong>that</strong> spr<strong>in</strong>gs from <strong>just</strong> go<strong>in</strong>g somewhere and film<strong>in</strong>g conveys a lot<strong>of</strong> truth—seldom do we see Hollywood- or Bollywood-style representations<strong>of</strong> poverty, <strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong> hovels constructed on sound stages are too largeand well-lighted and <strong>the</strong> actors wear <strong>the</strong>atrical rags. A sturdy tradition <strong>of</strong>comedy <strong>in</strong> Yoruba, Pidg<strong>in</strong>, and Engl<strong>is</strong>h deal<strong>in</strong>g with ord<strong>in</strong>ary people liv<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> a shared urban compound descends from <strong>the</strong> Yoruba travel<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>atertradition and from <strong>the</strong> classic 1980s Nigerian telev<strong>is</strong>ion situation comedies,like Ken Saro-Wiwa’s Basi and Company. The laughter <strong>is</strong> generated <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>struggle for survival <strong>in</strong> a world full <strong>of</strong> tricksters and predators (<strong>Lagos</strong> NaWah!; see Oha 2001). The <strong>in</strong>spired satire Holygans <strong>is</strong> set at about <strong>the</strong> sameclass level. Pidg<strong>in</strong>phone exponents <strong>of</strong> th<strong>is</strong> tradition <strong>of</strong>ten appear <strong>in</strong> Shakespeareanfashion as comic servants—gatemen, househelp—<strong>in</strong> <strong>films</strong> about<strong>the</strong>ir social superiors.The fact <strong>that</strong> public space <strong>is</strong> <strong>in</strong>coherent and art<strong>is</strong>tically unmanageableencourages retreat <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> family compound and <strong>the</strong> genre <strong>of</strong> domesticmelodrama, <strong>the</strong> dom<strong>in</strong>ant mode <strong>of</strong> Nollywood film. Nigerian film culturehas <strong>the</strong> upward social bias normal <strong>in</strong> film cultures around <strong>the</strong> world, preferr<strong>in</strong>gto set its stories <strong>in</strong> attractive large houses, or even <strong>in</strong> luxurious mansions.As Birgit Meyer has observed (speak<strong>in</strong>g about Ghanaian videos, though<strong>the</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>is</strong> equally valid for Nigerian ones), an attraction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>films</strong> for<strong>the</strong>ir audiences, who overwhelm<strong>in</strong>gly live <strong>in</strong> modest circumstances, <strong>is</strong> <strong>that</strong><strong>the</strong>y purport to provide a glimpse beh<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> high walls and impos<strong>in</strong>g gates<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> wealthy, which shut out <strong>the</strong> rest <strong>of</strong> society to shelter bourgeo<strong>is</strong> nuclearfamilies (Meyer 1999:110).Beh<strong>in</strong>d those walls, scenes <strong>of</strong> luxury unfold; what happens <strong>is</strong> <strong>in</strong>variablymelodramatic, and it frequently <strong>in</strong>volves <strong>the</strong> occult. As Meyer argues,mak<strong>in</strong>g spiritual forces v<strong>is</strong>ible <strong>is</strong> a crucial function <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> video <strong>films</strong> (Meyer2002a, 2002b, 2003; Oha 2001). The occult permeates all social environments<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> world <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> videos, and while one can f<strong>in</strong>d examples where it <strong>is</strong> associatedwith <strong>the</strong> primitive or village world, as opposed to urban modernity(Narrow Escape), more <strong>of</strong>ten it <strong>is</strong> <strong>in</strong>tegral to <strong>the</strong> representation <strong>of</strong> modernity