View and print the complete guide in a pdf file. - Utah ...

View and print the complete guide in a pdf file. - Utah ...

View and print the complete guide in a pdf file. - Utah ...

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Elizabeth’s Engl<strong>and</strong>In his entire career, William Shakespeare never once set a play <strong>in</strong> Elizabethan Engl<strong>and</strong>.His characters lived <strong>in</strong> medieval Engl<strong>and</strong> (Richard II), France (As You Like It), Vienna(Measure for Measure), fifteenth-century Italy (Romeo <strong>and</strong> Juliet), <strong>the</strong> Engl<strong>and</strong> ruled byElizabeth’s fa<strong>the</strong>r (Henry VIII) <strong>and</strong> elsewhere—anywhere <strong>and</strong> everywhere, <strong>in</strong> fact, exceptShakespeare’s own time <strong>and</strong> place. But all Shakespeare’s plays—even when <strong>the</strong>y were set <strong>in</strong>ancient Rome—reflected <strong>the</strong> life of Elizabeth’s Engl<strong>and</strong> (<strong>and</strong>, after her death <strong>in</strong> 1603, thatof her successor, James I). Thus, certa<strong>in</strong> th<strong>in</strong>gs about <strong>the</strong>se extraord<strong>in</strong>ary plays will be easierto underst<strong>and</strong> if we know a little more about Elizabethan Engl<strong>and</strong>.Elizabeth’s reign was an age of exploration—exploration of <strong>the</strong> world, exploration ofman’s nature, <strong>and</strong> exploration of <strong>the</strong> far reaches of <strong>the</strong> English language. This renaissanceof <strong>the</strong> arts <strong>and</strong> sudden flower<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> spoken <strong>and</strong> written word gave us two greatmonuments—<strong>the</strong> K<strong>in</strong>g James Bible <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> plays of Shakespeare—<strong>and</strong> many o<strong>the</strong>rtreasures as well.Shakespeare made full use of <strong>the</strong> adventurous Elizabethan attitude toward language.He employed more words than any o<strong>the</strong>r writer <strong>in</strong> history—more than 21,000 differentwords appear <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> plays—<strong>and</strong> he never hesitated to try a new word, revive an old one, ormake one up. Among <strong>the</strong> words which first appeared <strong>in</strong> <strong>pr<strong>in</strong>t</strong> <strong>in</strong> his works are such everydayterms as “critic,” “assass<strong>in</strong>ate,” “bump,” “gloomy,” “suspicious,” “<strong>and</strong> hurry;” <strong>and</strong> he<strong>in</strong>vented literally dozens of phrases which we use today: such un-Shakespeare expressions as“catch<strong>in</strong>g a cold,” “<strong>the</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d’s eye,” “elbow room,” <strong>and</strong> even “pomp <strong>and</strong> circumstance.”Elizabethan Engl<strong>and</strong> was a time for heroes. The ideal man was a courtier, an adventurer,a fencer with <strong>the</strong> skill of Tybalt, a poet no doubt better than Orl<strong>and</strong>o, a conversationalistwith <strong>the</strong> wit of Rosal<strong>in</strong>d <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> eloquence of Richard II, <strong>and</strong> a gentleman. In addition toall this, he was expected to take <strong>the</strong> time, like Brutus, to exam<strong>in</strong>e his own nature <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>cause of his actions <strong>and</strong> (perhaps unlike Brutus) to make <strong>the</strong> right choices. The real heroesof <strong>the</strong> age did all <strong>the</strong>se th<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>and</strong> more.Despite <strong>the</strong> greatness of some Elizabethan ideals, o<strong>the</strong>rs seem small <strong>and</strong> undignified, tous; marriage, for example, was often arranged to br<strong>in</strong>g wealth or prestige to <strong>the</strong> family, withlittle regard for <strong>the</strong> feel<strong>in</strong>gs of <strong>the</strong> bride. In fact, women were still relatively powerless under<strong>the</strong> law.The idea that women were “lower” than men was one small part of a vast concern withorder which was extremely important to many Elizabethans. Most people believed thateveryth<strong>in</strong>g, from <strong>the</strong> lowest gra<strong>in</strong> of s<strong>and</strong> to <strong>the</strong> highest angel, had its proper position <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> scheme of th<strong>in</strong>gs. This concept was called “<strong>the</strong> great cha<strong>in</strong> of be<strong>in</strong>g.” When th<strong>in</strong>gs were<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir proper place, harmony was <strong>the</strong> result; when order was violated, <strong>the</strong> entire structurewas shaken.This idea turns up aga<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> aga<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> Shakespeare. The rebellion aga<strong>in</strong>st Richard IIbr<strong>in</strong>gs bloodshed to Engl<strong>and</strong> for generations; Romeo <strong>and</strong> Juliet’s rebellion aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>the</strong>irparents contributes to <strong>the</strong>ir tragedy; <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> assass<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>in</strong> Julius Caesar throws Rome <strong>in</strong>tocivil war.Many Elizabethans also perceived duplications <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> cha<strong>in</strong> of order. They believed, forexample, that what <strong>the</strong> sun is to <strong>the</strong> heaves, <strong>the</strong> k<strong>in</strong>g is to <strong>the</strong> state. When someth<strong>in</strong>g wentwrong <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> heavens, rulers worried: before Julius Caesar <strong>and</strong> Richard II were overthrown,comets <strong>and</strong> meteors appeared, <strong>the</strong> moon turned <strong>the</strong> color of blood, <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r bizarreastronomical phenomena were reported. Richard himself compares his fall to a prematuresett<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> sun; when he descends from <strong>the</strong> top of Fl<strong>in</strong>t Castle to meet <strong>the</strong> conquer<strong>in</strong>g8<strong>Utah</strong> Shakespeare Festival351 West Center Street • Cedar City, <strong>Utah</strong> 84720 • 435-586-7880

Bol<strong>in</strong>gbroke, he likens himself to <strong>the</strong> driver of <strong>the</strong> sun’s chariot <strong>in</strong> Greek mythology:“Down, down I come, like glist’r<strong>in</strong>g Phaeton” (3.3.178).All <strong>the</strong>se ideas f<strong>in</strong>d expression <strong>in</strong> Shakespeare’s plays, along with hundreds of o<strong>the</strong>rs—most of <strong>the</strong>m not as strange to our way of th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g. As dramatized by <strong>the</strong> greatestplaywright <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> history of <strong>the</strong> world, <strong>the</strong> plays offer us a fasc<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g glimpse of <strong>the</strong>thoughts <strong>and</strong> passions of a brilliant age. Elizabethan Engl<strong>and</strong> was a brief skyrocket of art,adventure, <strong>and</strong> ideas which quickly burned out; but Shakespeare’s plays keep <strong>the</strong> best partsof that time alight forever.(Adapted from “The Shakespeare Plays,” educational materials made possible by Exxon,Metropolitan Life, Morgan Guaranty, <strong>and</strong> CPB.)<strong>Utah</strong> Shakespeare Festival351 West Center Street • Cedar City, <strong>Utah</strong> 84720 • 435-586-78809

History Is Written by <strong>the</strong> VictorsFrom Insights, 1994William Shakespeare wrote ten history plays chronicl<strong>in</strong>g English k<strong>in</strong>gs from <strong>the</strong> timeof <strong>the</strong> Magna Carta (K<strong>in</strong>g John) to <strong>the</strong> beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g of Engl<strong>and</strong>’s first great civil war, <strong>the</strong>Wars of <strong>the</strong> Roses (Richard II) to <strong>the</strong> conclusion of <strong>the</strong> war <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> reunit<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> twofactions (Richard III), to <strong>the</strong> reign of Queen Elizabeth’s fa<strong>the</strong>r (Henry VIII). Between<strong>the</strong>se plays, even though <strong>the</strong>y were not written <strong>in</strong> chronological order, is much of <strong>the</strong><strong>in</strong>terven<strong>in</strong>g history of Engl<strong>and</strong>, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> six Henry IV, Henry V, <strong>and</strong> Henry VI plays.In writ<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>se plays, Shakespeare had noth<strong>in</strong>g to help him except <strong>the</strong> st<strong>and</strong>ardhistory books of his day. The art of <strong>the</strong> historian was not very advanced <strong>in</strong> this period,<strong>and</strong> no serious attempt was made to get at <strong>the</strong> exact truth about a k<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> his reign.Instead, <strong>the</strong> general idea was that any nation that opposed Engl<strong>and</strong> was wrong, <strong>and</strong> thatany Englishman who opposed <strong>the</strong> w<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g side <strong>in</strong> a civil war was wrong also.S<strong>in</strong>ce Shakespeare had no o<strong>the</strong>r sources, <strong>the</strong> slant that appears <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> history booksof his time also appears <strong>in</strong> his plays. Joan of Arc opposed <strong>the</strong> English <strong>and</strong> was notadmired <strong>in</strong> Shakespeare’s day, so she is portrayed as a comic character who w<strong>in</strong>s hervictories through witchcraft. Richard III fought aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>the</strong> first Tudor monarchs <strong>and</strong>was <strong>the</strong>refore labeled <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Tudor histories as a vicious usurper, <strong>and</strong> he duly appears <strong>in</strong>Shakespeare’s plays as a murder<strong>in</strong>g monster.Shakespeare wrote n<strong>in</strong>e of his history plays under Queen Elizabeth. She did notencourage historical truthfulness, but ra<strong>the</strong>r a patriotism, an exultant, <strong>in</strong>tense convictionthat Engl<strong>and</strong> was <strong>the</strong> best of all possible countries <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> home of <strong>the</strong> most favoredof mortals. And this patriotism brea<strong>the</strong>s through all <strong>the</strong> history plays <strong>and</strong> b<strong>in</strong>ds <strong>the</strong>mtoge<strong>the</strong>r. Engl<strong>and</strong>’s enemy is not so much any <strong>in</strong>dividual k<strong>in</strong>g as <strong>the</strong> threat of civil war,<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> history plays come to a triumphant conclusion when <strong>the</strong> threat of civil war isf<strong>in</strong>ally averted, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> great queen, Elizabeth, is born.Shakespeare was a playwright, not a historian, <strong>and</strong>, even when his sources were correct,he would sometimes juggle his <strong>in</strong>formation for <strong>the</strong> sake of effective stagecraft. He wasnot <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> historical accuracy; he was <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> swiftly mov<strong>in</strong>g action <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong> people. Shakespeare’s bloody <strong>and</strong> supurb k<strong>in</strong>g seems more conv<strong>in</strong>c<strong>in</strong>g than <strong>the</strong> realRichard III, merely because Shakespeare wrote so effectively about him. Shakespearemoved <strong>in</strong> a different world from that of <strong>the</strong> historical, a world of creation ra<strong>the</strong>r thanof recorded fact, <strong>and</strong> it is <strong>in</strong> this world that he is so supreme a master.10<strong>Utah</strong> Shakespeare Festival351 West Center Street • Cedar City, <strong>Utah</strong> 84720 • 435-586-7880

Mr. Shakespeare, I Presumeby Diana Major SpencerFrom Insights, 1994Could <strong>the</strong> plays known as Shakespeare’s have been written by a rural, semi-literate,uneducated, wife-desert<strong>in</strong>g, two-bit actor who spelled him name differently each of <strong>the</strong>six times he wrote it down? Could such a man know enough about Roman history, Italiangeography, French grammar, <strong>and</strong> English court habits to create Antony <strong>and</strong> Cleopatra, TheComedy of Errors, <strong>and</strong> Henry V? Could he know enough about nobility <strong>and</strong> its tenuousrelationship to royalty to create K<strong>in</strong>g Lear <strong>and</strong> Macbeth?Are <strong>the</strong>se questions even worth ask<strong>in</strong>g? Some very <strong>in</strong>telligent people th<strong>in</strong>k so. On <strong>the</strong>o<strong>the</strong>r h<strong>and</strong>, some very <strong>in</strong>telligent people th<strong>in</strong>k not. Never m<strong>in</strong>d quibbles about how a l<strong>in</strong>eshould be <strong>in</strong>terpreted, or how many plays Shakespeare wrote <strong>and</strong> which ones, or whichof <strong>the</strong> great tragedies reflected personal tragedies. The question of authorship is “TheShakespeare Controversy.”S<strong>in</strong>ce Mr. Cowell, quot<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> deceased Dr. Wilmot, cast <strong>the</strong> first doubt about Williamof Stratford <strong>in</strong> an 1805 speech before <strong>the</strong> Ipswich Philological Society, nom<strong>in</strong>ees for<strong>the</strong> “real author” have <strong>in</strong>cluded philosopher Sir Francis Bacon, playwright ChristopherMarlowe, Queen Elizabeth I, Sir Walter Raleigh, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> earls of Derby, Rutl<strong>and</strong>, Essex,<strong>and</strong> Oxford--among o<strong>the</strong>rs.The arguments evoke two premises: first, that <strong>the</strong> proven facts about <strong>the</strong> WilliamShakespeare who was christened at Holy Tr<strong>in</strong>ity Church <strong>in</strong> Stratford-upon-Avon on April26, 1564 do not configure a man of sufficient nobility of thought <strong>and</strong> language to havewritten <strong>the</strong> plays; <strong>and</strong>, second, that <strong>the</strong> man from Stratford is nowhere concretely identifiedas <strong>the</strong> author of <strong>the</strong> plays. The name “Shakespeare”—<strong>in</strong> one of its spell<strong>in</strong>gs—appears onearly quartos, but <strong>the</strong> man represented by <strong>the</strong> name may not be <strong>the</strong> one from Stratford.One group of objections to <strong>the</strong> Stratford man follows from <strong>the</strong> absence of any recordthat he ever attended school—<strong>in</strong> Stratford or anywhere else. If he were uneducated, <strong>the</strong>arguments go, how could his vocabulary be twice as large as <strong>the</strong> learned Milton’s? Howcould he know so much history, law, or philosophy? If he were a country bumpk<strong>in</strong>, howcould he know so much of hawk<strong>in</strong>g, hound<strong>in</strong>g, courtly manners, <strong>and</strong> daily habits of <strong>the</strong>nobility? How could he have traveled so much, learn<strong>in</strong>g about o<strong>the</strong>r nations of Europe <strong>in</strong>enough detail to make <strong>the</strong>m <strong>the</strong> sett<strong>in</strong>gs for his plays?The assumptions of <strong>the</strong>se arguments are that such rich <strong>and</strong> noble works as thoseattributed to a playwright us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> name “Shakespeare” could have been written only bysomeone with certa<strong>in</strong> characteristics, <strong>and</strong> that those characteristics could be distilled from<strong>the</strong> “facts” of his life. He would have to be noble; he would have to be well-educated; <strong>and</strong>so forth. On <strong>the</strong>se grounds <strong>the</strong> strongest c<strong>and</strong>idate to date is Edward de Vere, seventeen<strong>the</strong>arl of Oxford.A debate that has endured its peaks <strong>and</strong> valleys, <strong>the</strong> controversy catapulted to center stage<strong>in</strong> 1984 with <strong>the</strong> publication of Charlton Ogburn’s The Mysterious William Shakespeare.Ogburn, a former army <strong>in</strong>telligence officer, builds a strong case for Oxford—if one canhurdle <strong>the</strong> notions that <strong>the</strong> author wasn’t Will Shakespeare, that literary works should beread autobiographically, <strong>and</strong> that literary creation is noth<strong>in</strong>g more than report<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> factsof one’s own life. “The Controversy” was laid to rest—temporarily, at least—by justicesBlackmun, Brennan, <strong>and</strong> Stevens of <strong>the</strong> United States Supreme Court who, after hear<strong>in</strong>gevidence from both sides <strong>in</strong> a mock trial conducted September 25, 1987 at AmericanUniversity <strong>in</strong> Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, D.C., found <strong>in</strong> favor of <strong>the</strong> Bard of Avon.Hooray for our side!<strong>Utah</strong> Shakespeare Festival351 West Center Street • Cedar City, <strong>Utah</strong> 84720 • 435-586-788011

A Nest of S<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g BirdsFrom Insights, 1992Musical development was part of <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tellectual <strong>and</strong> social movement that <strong>in</strong>fluencedall Engl<strong>and</strong> dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Tudor Age. The same forces that produced writers like Sir PhilipSidney, Edmund Spenser, William Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, John Donne, <strong>and</strong> FrancisBacon also produced musicians of correspond<strong>in</strong>g caliber. So numerous <strong>and</strong> prolific were<strong>the</strong>se talented <strong>and</strong> imag<strong>in</strong>ative men—men whose reputations were even <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir own dayfirmly established <strong>and</strong> well founded—that <strong>the</strong>y have been frequently <strong>and</strong> aptly referred toas a nest of s<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g birds.One such figure was Thomas Tallis, whose music has officially accompanied <strong>the</strong> Anglicanservice s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> days of Elizabeth I; ano<strong>the</strong>r was his student, William Boyd, whose varietyof religious <strong>and</strong> secular compositions won him <strong>in</strong>ternational reputation.Queen Elizabeth I, of course, provided an <strong>in</strong>spiration for <strong>the</strong> best efforts of Englishmen,whatever <strong>the</strong>ir aims <strong>and</strong> activities. For music, she was <strong>the</strong> ideal patroness. She was anaccomplished performer on <strong>the</strong> virg<strong>in</strong>al (forerunner to <strong>the</strong> piano), <strong>and</strong> she aided herfavorite art immensely <strong>in</strong> every way possible, bestow<strong>in</strong>g her favors on <strong>the</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gers <strong>in</strong> chapel<strong>and</strong> court <strong>and</strong> on <strong>the</strong> musicians <strong>in</strong> public <strong>and</strong> private <strong>the</strong>atrical performances. To <strong>the</strong> greatcomposers of her time, she was particularly gracious <strong>and</strong> helpful.S<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g has been an <strong>in</strong>tegral part of English life for as long as we have any knowledge.Long before <strong>the</strong> music was written down, <strong>the</strong> timeless folk songs were a part of ourAnglo-Saxon heritage. The madrigals <strong>and</strong> airs that are enjoyed each summer at <strong>the</strong> <strong>Utah</strong>Shakespeare Festival evolved from <strong>the</strong>se traditions.It was noted by Bishop Jewel <strong>in</strong> l560 that sometimes at Paul’s Cross <strong>the</strong>re would be6,000 people s<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g toge<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>and</strong> before <strong>the</strong> sermon, <strong>the</strong> whole congregation always sanga psalm, toge<strong>the</strong>r with <strong>the</strong> choir <strong>and</strong> organ. When that thunder<strong>in</strong>g unity of congregationalchorus came <strong>in</strong>, “I was so transported <strong>the</strong>re was no room left <strong>in</strong> my whole body, m<strong>in</strong>d, orspirit for anyth<strong>in</strong>g below div<strong>in</strong>e <strong>and</strong> heavenly raptures.”Religious expression was likely <strong>the</strong> dom<strong>in</strong>ant musical motif of <strong>the</strong> Elizabethan period;however, <strong>the</strong> period also saw development of English stage music, with Morley, JohnWilson, <strong>and</strong> Robert Johnson sett<strong>in</strong>g much of <strong>the</strong>ir music to <strong>the</strong> plays of Shakespeare. Themasque, a semi-musical enterta<strong>in</strong>ment, reached a high degree of perfection at <strong>the</strong> court ofJames I, where <strong>the</strong> courtiers <strong>the</strong>mselves were sometimes participants. An educated person of<strong>the</strong> time was expected to perform music more than just fairly well, <strong>and</strong> an <strong>in</strong>ability <strong>in</strong> thisarea might elicit whispered comments regard<strong>in</strong>g lack of genteel upbr<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g, not only <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ability to take one’s part <strong>in</strong> a madrigal, but also <strong>in</strong> know<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> niceties of musical <strong>the</strong>ory.Henry Peacham wrote <strong>in</strong> The Compleat Gentleman <strong>in</strong> l662 that one of <strong>the</strong> fundamentalqualities of a gentleman was to be able to “s<strong>in</strong>g your part sure, <strong>and</strong>...to play <strong>the</strong> same uponyour viol.”Outside <strong>the</strong> walls of court could be heard street songs, ligh<strong>the</strong>arted catches, <strong>and</strong> ballads,all of which <strong>in</strong>dicates that music was not conf<strong>in</strong>ed to <strong>the</strong> ca<strong>the</strong>drals or court. We stillhave extant literally hundreds of ballads, street songs, <strong>and</strong> vendors’ cries that were sungor hummed on <strong>the</strong> street <strong>and</strong> played with all <strong>the</strong>ir complicated variations on all levels ofElizabethan society.Instruments of <strong>the</strong> period were as varied as <strong>the</strong> music <strong>and</strong> peoples, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>strument<strong>and</strong> songbooks which rema<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> existence today are <strong>in</strong>dicative of <strong>the</strong> high level of excellenceenjoyed by <strong>the</strong> Elizabethans. Songbooks, ma<strong>in</strong>ly of part-songs for three, four, five, <strong>and</strong> six12<strong>Utah</strong> Shakespeare Festival351 West Center Street • Cedar City, <strong>Utah</strong> 84720 • 435-586-7880

voices exist today, as do books of dance music: corrantos, pavans, <strong>and</strong> galliards. Recordsfrom one wealthy family <strong>in</strong>dicate <strong>the</strong> family owned forty musical <strong>in</strong>struments, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gtwelve viols, seven recorders, four lutes, five virg<strong>in</strong>als, various brasses <strong>and</strong> woodw<strong>in</strong>ds, <strong>and</strong>two “great organs.” To have use for such a great number of <strong>in</strong>struments implies a fairly largegroup of players resident with <strong>the</strong> family or stay<strong>in</strong>g with <strong>the</strong>m as <strong>in</strong>vited guests, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>players of <strong>the</strong> most popular <strong>in</strong>struments (lutes, virg<strong>in</strong>als, <strong>and</strong> viols) would be play<strong>in</strong>g fromlong tradition, at least back to K<strong>in</strong>g Henry VIII. In short, music was as necessary to <strong>the</strong>public <strong>and</strong> private existence of a Renaissance Englishman as any of <strong>the</strong> basic elements of life.The <strong>Utah</strong> Shakespeare Festival musicians perform each summer on au<strong>the</strong>ntic replicasof many of <strong>the</strong>se Renaissance <strong>in</strong>struments. The music <strong>the</strong>y perform is au<strong>the</strong>ntic from <strong>the</strong>Elizabethan period, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>struments are made available for audience <strong>in</strong>spection <strong>and</strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g.<strong>Utah</strong> Shakespeare Festival351 West Center Street • Cedar City, <strong>Utah</strong> 84720 • 435-586-788013

But however he got <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>atre <strong>and</strong> to London, he had made a very def<strong>in</strong>iteimpression on his competitors by 1592, when playwright Robert Greene attackedShakespeare as both actor <strong>and</strong> author: “‘There is an upstart Crow, beautified with ourfea<strong>the</strong>rs, that with his Tiger’s heart wrapt <strong>in</strong> a Player’s hide, supposes he is as well ableto bombast out a blank verse as <strong>the</strong> best of you: <strong>and</strong> . . . is <strong>in</strong> his own conceit <strong>the</strong> onlyShake-scene <strong>in</strong> a country’” (G. B. Harrison, Introduc<strong>in</strong>g Shakespeare [New York: Pengu<strong>in</strong>Books, Inc., 1947], 1).We don’t often th<strong>in</strong>k of Shakespeare as primarily an actor, perhaps because most ofwhat we know of him comes from <strong>the</strong> plays he wrote ra<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>the</strong> parts he played.Never<strong>the</strong>less, he made much of his money as an actor <strong>and</strong> sharer <strong>in</strong> his company: “Atleast to start with, his status, his security derived more from his act<strong>in</strong>g skill <strong>and</strong> his eye forbus<strong>in</strong>ess than from his pen” (Kay, 95). Had he been only a playwright, he would likely havedied a poor man, as did Robert Greene: “In <strong>the</strong> autumn of 1592, Robert Greene, <strong>the</strong> mostpopular author of his generation, lay penniless <strong>and</strong> dy<strong>in</strong>g. . . . The players had grown richon <strong>the</strong> products of his bra<strong>in</strong>, <strong>and</strong> now he was deserted <strong>and</strong> alone” (Harrison, 1).While Shakespeare made a career of act<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>the</strong>re are critics who might dispute his act<strong>in</strong>gtalent. For <strong>in</strong>stance, almost a century after Shakespeare’s death, “an anonymous enthusiastof <strong>the</strong> stage . . . remarked . . . that ‘Shakespear . . . was a much better poet, than player’”(Schoenbaum, 201). However, Shakespeare could have been quite a good actor, <strong>and</strong> thisstatement would still be true. One sign of his skill as an actor is that he is mentioned <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>same breath with Burbage <strong>and</strong> Kemp: “The accounts of <strong>the</strong> royal household for Mar 15[1595] record payments to ‘William Kempe William Shakespeare & Richarde Burbageseruantes to <strong>the</strong> Lord Chamberla<strong>in</strong>’” (Kay, 174).Ano<strong>the</strong>r significant <strong>in</strong>dication of his talent is <strong>the</strong> very fact that he played <strong>in</strong> Londonra<strong>the</strong>r than tour<strong>in</strong>g o<strong>the</strong>r less lucrative towns. If players were to be legally reta<strong>in</strong>ed bynoblemen, <strong>the</strong>y had to prove <strong>the</strong>y could act, <strong>and</strong> one means of demonstrat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>irlegitimacy was play<strong>in</strong>g at court for Queen Elizabeth. The more skilled companies obta<strong>in</strong>ed<strong>the</strong> queen’s favor <strong>and</strong> were granted permission to rema<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> London.Not all companies, however, were so fortunate: “Sussex’s men may not have been quiteup to <strong>the</strong> transition from rural <strong>in</strong>n-yards to <strong>the</strong> more dem<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g circumstances of courtperformance. Just before <strong>the</strong> Christmas season of 1574, for example, <strong>the</strong>y were <strong>in</strong>spected(‘perused’) by officials of <strong>the</strong> Revels Office, with a view to be<strong>in</strong>g permitted to performbefore <strong>the</strong> queen; but <strong>the</strong>y did not perform” (Kay, 90). Shakespeare <strong>and</strong> his company, on<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r h<strong>and</strong>, performed successfully <strong>in</strong> London from <strong>the</strong> early 1590s until 1611.It would be a mistake to classify William Shakespeare as only a playwright, even <strong>the</strong>greatest playwright of <strong>the</strong> English-speak<strong>in</strong>g world; he was also “an actor, a sharer, a memberof a company” (Kay, 95), obligations that were extremely relevant to his plays. As a man of<strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>atre writ<strong>in</strong>g for a company, he knew what would work on stage <strong>and</strong> what would not<strong>and</strong> was able to make his plays practical as well as brilliant. And perhaps more importantly,his <strong>the</strong>atrical experience must have taught him much about <strong>the</strong> human experience, abouteveryday lives <strong>and</strong> roles, just as his plays show us that “All <strong>the</strong> world’s a stage, / And all<strong>the</strong> men <strong>and</strong> women merely players” (As You Like It, 2.7.149-50).<strong>Utah</strong> Shakespeare Festival351 West Center Street • Cedar City, <strong>Utah</strong> 84720 • 435-586-788015

Shakespeare’s Audience:A Very Motley CrowdFrom Insights, 1992When Shakespeare peeped through <strong>the</strong> curta<strong>in</strong> at <strong>the</strong> audience ga<strong>the</strong>red to hear his first play, helooked upon a very motley crowd. The pit was filled with men <strong>and</strong> boys. The galleries conta<strong>in</strong>eda fair proportion of women, some not too respectable. In <strong>the</strong> boxes were a few gentlemen from<strong>the</strong> royal courts, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> lords’ box or perhaps sitt<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong> stage was a group of extravagantlydressed gentlemen of fashion. Vendors of nuts <strong>and</strong> fruits moved about through <strong>the</strong> crowd. Thegallants were smok<strong>in</strong>g; <strong>the</strong> apprentices <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> pit were exchang<strong>in</strong>g rude witticisms with <strong>the</strong> pa<strong>in</strong>tedladies.When Shakespeare addressed his audience directly, he did so <strong>in</strong> terms of gentle courtesy orpleasant raillery. In Hamlet, however, he does let fall <strong>the</strong> op<strong>in</strong>ion that <strong>the</strong> groundl<strong>in</strong>gs (those on <strong>the</strong>ground, <strong>the</strong> cheapest seats) were “for <strong>the</strong> most part capable of noth<strong>in</strong>g but dumb shows <strong>and</strong> noise.”His recollections of <strong>the</strong> pit of <strong>the</strong> Globe may have added vigor to his ridicule of <strong>the</strong> Roman mob <strong>in</strong>Julius Caesar.On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r h<strong>and</strong>, <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>atre was a popular <strong>in</strong>stitution, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> audience was representative ofall classes of London life. Admission to st<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g room <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> pit was a penny, <strong>and</strong> an additionalpenny or two secured a seat <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> galleries. For seats <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> boxes or for stools on <strong>the</strong> stage, stillmore was charged, up to sixpence or half a crown.Attendance at <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>atres was astonish<strong>in</strong>gly large. There were often five or six <strong>the</strong>atres giv<strong>in</strong>gdaily performances, which would mean that out of a city of one hundred thous<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>habitants,thirty thous<strong>and</strong> or more spectators each week attended <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>atre. When we remember that alarge class of <strong>the</strong> population disapproved of <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>atre, <strong>and</strong> that women of respectability were notfrequent patrons of <strong>the</strong> public playhouses, this attendance is remarkable.Arrangements for <strong>the</strong> comfort of <strong>the</strong> spectators were meager, <strong>and</strong> spectators were often disorderly.Playbills seem to have been posted all about town <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>atre, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> title of <strong>the</strong> piece wasannounced on <strong>the</strong> stage. These bills conta<strong>in</strong>ed no lists of actors, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>re were no programs,ushers, or tickets. There was usually one door for <strong>the</strong> audience, where <strong>the</strong> admission fee wasdeposited <strong>in</strong> a box carefully watched by <strong>the</strong> money taker, <strong>and</strong> additional sums were required atentrance to <strong>the</strong> galleries or boxes. When <strong>the</strong> three o’clock trumpets announced <strong>the</strong> beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g of aperformance, <strong>the</strong> assembled audience had been amus<strong>in</strong>g itself by eat<strong>in</strong>g, dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g, smok<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong>play<strong>in</strong>g cards, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>y sometimes cont<strong>in</strong>ued <strong>the</strong>se occupations dur<strong>in</strong>g a performance. Pickpocketswere frequent, <strong>and</strong>, if caught, were tied to a post on <strong>the</strong> stage. Disturbances were not <strong>in</strong>frequent,sometimes result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> general riot<strong>in</strong>g.The Elizabethan audience was fond of unusual spectacle <strong>and</strong> brutal physical suffer<strong>in</strong>g. Theyliked battles <strong>and</strong> murders, processions <strong>and</strong> fireworks, ghosts <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>sanity. They expected comedy toabound <strong>in</strong> beat<strong>in</strong>gs, <strong>and</strong> tragedy <strong>in</strong> deaths. While <strong>the</strong> audience at <strong>the</strong> Globe expected some of <strong>the</strong>sesensations <strong>and</strong> physical horrors, <strong>the</strong>y did not come primarily for <strong>the</strong>se. (Real blood <strong>and</strong> torture wereavailable nearby at <strong>the</strong> bear bait<strong>in</strong>gs, <strong>and</strong> public executions were not uncommon.) Actually, <strong>the</strong>rewere very few public enterta<strong>in</strong>ments offer<strong>in</strong>g as little brutality as did <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>atre.Elizabethans attended <strong>the</strong> public playhouses for learn<strong>in</strong>g. They attended for romance,imag<strong>in</strong>ation, idealism, <strong>and</strong> art; <strong>the</strong> audience was not without ref<strong>in</strong>ement, <strong>and</strong> those look<strong>in</strong>g forfood for <strong>the</strong> imag<strong>in</strong>ation had nowhere to go but to <strong>the</strong> playhouse. There were no newspapers, no16<strong>Utah</strong> Shakespeare Festival351 West Center Street • Cedar City, <strong>Utah</strong> 84720 • 435-586-7880

magaz<strong>in</strong>es, almost no novels, <strong>and</strong> only a few cheap books; <strong>the</strong>atre filled <strong>the</strong> desire for storydiscussion among people lack<strong>in</strong>g o<strong>the</strong>r educational <strong>and</strong> cultural opportunities.The most remarkable case of Shakespeare’s <strong>the</strong>atre fill<strong>in</strong>g an educational need is probably thatof English history. The growth of national patriotism culm<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> English victory over <strong>the</strong>Spanish Armada gave dramatists a chance to use <strong>the</strong> historical material, <strong>and</strong> for <strong>the</strong> fifteen yearsfrom <strong>the</strong> Armada to <strong>the</strong> death of Elizabeth, <strong>the</strong> stage was deluged with plays based on <strong>the</strong> eventsof English chronicles, <strong>and</strong> familiarity with English history became a cultural asset of <strong>the</strong> Londoncrowd,Law was a second area where <strong>the</strong> Elizabethan public seems to have been fairly well <strong>in</strong>formed,<strong>and</strong> successful dramatists realized <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>fluence that <strong>the</strong> great development of civil law <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>sixteenth century exercised upon <strong>the</strong> daily life of <strong>the</strong> London citizen. In this area, as <strong>in</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs,<strong>the</strong> dramatists did not hesitate to cultivate <strong>the</strong> cultural background of <strong>the</strong>ir audience wheneveropportunity offered, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> ignorance of <strong>the</strong> multitude did not prevent it from tak<strong>in</strong>g an <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong> new <strong>in</strong>formation <strong>and</strong> from offer<strong>in</strong>g a receptive hear<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> accumulated lore of lawyers,historians, humanists, <strong>and</strong> playwrights.The audience was used to <strong>the</strong> spoken word, <strong>and</strong> soon became tra<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> blank verse, delight<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> monologues, debates, puns, metaphors, stump speakers, <strong>and</strong> sonorous declamation. The publicwas accustomed to <strong>the</strong> act<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> old religious dramas, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> new act<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong>spoken words were listened to caught on rapidly. The new poetry <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> great actors who recitedit found a sensitive audience. There were many moments dur<strong>in</strong>g a play when spectacle, brutality,<strong>and</strong> action were all forgotten, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> audience fed only on <strong>the</strong> words. Shakespeare <strong>and</strong> hiscontemporaries may be deemed fortunate <strong>in</strong> hav<strong>in</strong>g an audience essentially attentive, eager for<strong>the</strong> newly unlocked storehouse of secular story, <strong>and</strong> possess<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> sophistication <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>terest tobe fed richly by <strong>the</strong> excitements <strong>and</strong> levities on <strong>the</strong> stage.<strong>Utah</strong> Shakespeare Festival351 West Center Street • Cedar City, <strong>Utah</strong> 84720 • 435-586-788017

In London itself, <strong>the</strong> new Globe, <strong>the</strong> best <strong>the</strong>atre <strong>in</strong> (or ra<strong>the</strong>r just outside of) <strong>the</strong> city,was <strong>in</strong> an area with a large number of prisons <strong>and</strong> an unpleasant smell. “Garbage hadpreceded actors on <strong>the</strong> marshy l<strong>and</strong> where <strong>the</strong> new playhouse was erected: `flanked witha ditch <strong>and</strong> forced out of a marsh’, accord<strong>in</strong>g to Ben Jonson. Its cost . . . <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>the</strong>provision of heavy piles for <strong>the</strong> foundation, <strong>and</strong> a whole network of ditches <strong>in</strong> which<strong>the</strong> water rose <strong>and</strong> fell with <strong>the</strong> tidal Thames” (Garry O’Connor, William Shakespeare: APopular Life [New York: Applause Books, 2000], 161). The playgoers came by water, <strong>and</strong><strong>the</strong> Globe, <strong>the</strong> Rose, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Swan “drew 3,000 or 4,000 people <strong>in</strong> boats across <strong>the</strong> Thamesevery day” (161). Peter Levi says of Shakespeare’s London, “The noise, <strong>the</strong> crowds, <strong>the</strong>animals <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir dropp<strong>in</strong>gs, <strong>the</strong> glimpses of gr<strong>and</strong>eur <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> amaz<strong>in</strong>g squalor of <strong>the</strong> poor,were beyond modern imag<strong>in</strong>ation” (49).Engl<strong>and</strong> was a place of fear <strong>and</strong> glory. Public executions were public enterta<strong>in</strong>ments.Severed heads decayed on city walls. Francis Bacon, whom Will Durant calls “<strong>the</strong> mostpowerful <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>fluential <strong>in</strong>tellect of his time” (Heroes of History: A Brief History ofCivilization from Ancient Times to <strong>the</strong> Dawn of <strong>the</strong> Modern Age [New York: Simon &Schuster, 2001], 327), had been “one of <strong>the</strong> persons commissioned to question prisonersunder torture” <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1580s (Levi 4). The opportune moment when Shakespeare became<strong>the</strong> most successful of playwrights was <strong>the</strong> destruction of Thomas Kyd, “who broke undertorture <strong>and</strong> was never <strong>the</strong> same aga<strong>in</strong>,” <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> death of Christopher Marlowe <strong>in</strong> a tavernbrawl which was <strong>the</strong> result of plot <strong>and</strong> counterplot—a struggle, very probably, betweenLord Burghley <strong>and</strong> Walter Ralegh (Levi 48).Shakespeare, who must have known <strong>the</strong> rumors <strong>and</strong> may have known <strong>the</strong> truth, cannothave helped shudder<strong>in</strong>g at such monstrous good fortune. Still, all of <strong>the</strong> sights, smells, <strong>and</strong>terrors, from <strong>the</strong> birdsongs to <strong>the</strong> screams of torture, from <strong>the</strong> muddy tides to <strong>the</strong> ties ofblood, became not only <strong>the</strong> textures <strong>and</strong> tonalities of Shakespeare’s life, but also <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>spiration beh<strong>in</strong>d his plays.<strong>Utah</strong> Shakespeare Festival351 West Center Street • Cedar City, <strong>Utah</strong> 84720 • 435-586-788019

20Ghosts, Witches, <strong>and</strong> ShakespeareBy Howard WatersFrom Insights, 2006Some time <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> mid 1580s, young Will Shakespeare, for reasons not entirely clear tous, left his home, his wife, <strong>and</strong> his family <strong>in</strong> Stratford <strong>and</strong> set off for London. It was a timewhen Elizabeth, “la plus f<strong>in</strong>e femme du monde,” as Henry III of France called her, hadoccupied <strong>the</strong> throne of Engl<strong>and</strong> for over twenty-five years. The tragedy of Mary Stuart waspast; <strong>the</strong> ordeal of Essex was <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> future. Sir Francis Drake’s neutralization of <strong>the</strong> SpanishArmada was pend<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> rumors of war or <strong>in</strong>vasion blew <strong>in</strong> from all <strong>the</strong> great ports.What could have been more excit<strong>in</strong>g for a young man from <strong>the</strong> country, one who wasalready more than half <strong>in</strong> love with words, than to be headed for London!It was an excit<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> frighten<strong>in</strong>g time, when <strong>the</strong> seven gates of London led to a mazeof streets, narrow <strong>and</strong> dirty, crowded with tradesmen, carts, coaches, <strong>and</strong> all manner ofhumanity. Young Will would have seen <strong>the</strong> moated Tower of London, look<strong>in</strong>g almost likean isl<strong>and</strong> apart. There was London Bridge crowded with tenements <strong>and</strong> at <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rnend a cluster of traitors’ heads impaled on poles. At Tyburn thieves <strong>and</strong> murderers dangled,at Limehouse pirates were trussed up at low tide <strong>and</strong> left to wait for <strong>the</strong> water to rise over<strong>the</strong>m. At Tower Hill <strong>the</strong> headsman’s axe flashed regularly, while for <strong>the</strong> vagabonds <strong>the</strong>rewere <strong>the</strong> whipp<strong>in</strong>g posts, <strong>and</strong> for <strong>the</strong> beggars <strong>the</strong>re were <strong>the</strong> stocks. Such was <strong>the</strong> London of<strong>the</strong> workaday world, <strong>and</strong> young Will was undoubtedly mentally fil<strong>in</strong>g away details of wha<strong>the</strong> saw, heard, <strong>and</strong> smelled.Elizabethan people <strong>in</strong> general were an emotional lot <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> ferocity of <strong>the</strong>ir enterta<strong>in</strong>mentreflected that fact. Bear-bait<strong>in</strong>g, for example, was a highly popular spectator sport, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>structure where <strong>the</strong>y were generally held was not unlike <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>atres of <strong>the</strong> day. A bear wascha<strong>in</strong>ed to a stake <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> center of <strong>the</strong> pit, <strong>and</strong> a pack of large dogs was turned loose to bait,or fight, him. The bear eventually tired (fortunately for <strong>the</strong> rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g dogs!), <strong>and</strong>, well,you can figure <strong>the</strong> rest out for yourself. Then <strong>the</strong>re were <strong>the</strong> public hang<strong>in</strong>gs, whipp<strong>in</strong>gs,or draw<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> quarter<strong>in</strong>gs for an afternoon’s enterta<strong>in</strong>ment. So, <strong>the</strong> violence <strong>in</strong> some ofShakespeare’s plays was clearly directed at an audience that reveled <strong>in</strong> it. Imag<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> effectof hav<strong>in</strong>g an actor pretend to bite off his own tongue <strong>and</strong> spit a chunk of raw liver that hehad carefully packed <strong>in</strong> his jaw <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> faces of <strong>the</strong> groundl<strong>in</strong>gs!Despite <strong>the</strong> progress<strong>in</strong>g enlightenment of <strong>the</strong> Renaissance, superstition was still rampantamong Elizabethan Londoners, <strong>and</strong> a belief <strong>in</strong> such th<strong>in</strong>gs as astrology was common (RalphP. Boas <strong>and</strong> Barbara M. Hahna, “The Age of Shakespeare,” Social Backgrounds of EnglishLiterature, [Boston: Little, Brown <strong>and</strong> Co., 1931] 93). Through <strong>the</strong> position of stars manyElizabethans believed that com<strong>in</strong>g events could be foretold even to <strong>the</strong> extent of mapp<strong>in</strong>gout a person’s entire life.Where witches <strong>and</strong> ghosts were concerned, it was commonly accepted that <strong>the</strong>y existed<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> person who scoffed at <strong>the</strong>m was considered foolish, or even likely to be cursed.Consider <strong>the</strong> fact that Shakespeare’s Macbeth was supposedly cursed due to <strong>the</strong> playwright’shav<strong>in</strong>g given away a few more of <strong>the</strong> secrets of witchcraft than <strong>the</strong> weird sisters may haveapproved of. For a time, productions experienced an uncanny assortment of mishaps <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>juries. Even today, it is often considered bad luck for members of <strong>the</strong> cast <strong>and</strong> crew tomention <strong>the</strong> name of <strong>the</strong> production, simply referred to as <strong>the</strong> Scottish Play. In preach<strong>in</strong>ga sermon, Bishop Jewel warned <strong>the</strong> Queen: “It may please your Grace to underst<strong>and</strong> thatwitches <strong>and</strong> sorcerers with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>se last few years are marvelously <strong>in</strong>creased. Your Grace’s<strong>Utah</strong> Shakespeare Festival351 West Center Street • Cedar City, <strong>Utah</strong> 84720 • 435-586-7880

subjects p<strong>in</strong>e away, even unto death; <strong>the</strong>ir color fadeth; <strong>the</strong>ir flesh rotteth; <strong>the</strong>ir speech isbenumbed; <strong>the</strong>ir senses bereft” (Walter Bromberg, “Witchcraft <strong>and</strong> Psycho<strong>the</strong>rapy”, TheM<strong>in</strong>d of Man [New York: Harper Torchbooks 1954], 54).Ghosts were recognized by <strong>the</strong> Elizabethans <strong>in</strong> three basic varieties: <strong>the</strong> vision or purelysubjective ghost, <strong>the</strong> au<strong>the</strong>ntic ghost who has died without opportunity of repentance, <strong>and</strong><strong>the</strong> false ghost which is capable of many types of manifestations (Boas <strong>and</strong> Hahn). Whena ghost was confronted, ei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong> reality or <strong>in</strong> a Shakespeare play, some obviousdiscrim<strong>in</strong>ation was called for (<strong>and</strong> still is). Critics still do not always agree on which of <strong>the</strong>sethree types haunts <strong>the</strong> pages of Julius Caesar, Macbeth, Richard III, or Hamlet, or, <strong>in</strong> somecases, why <strong>the</strong>y are necessary to <strong>the</strong> plot at all. After all, Shakespeare’s ghosts are a capriciouslot, mak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>mselves visible or <strong>in</strong>visible as <strong>the</strong>y please. In Richard III <strong>the</strong>re are no fewerthan eleven ghosts on <strong>the</strong> stage who are visible only to Richard <strong>and</strong> Richmond. In Macbeth<strong>the</strong> ghost of Banquo repeatedly appears to Macbeth <strong>in</strong> crowded rooms but is visibleonly to him. In Hamlet, <strong>the</strong> ghost appears to several people on <strong>the</strong> castle battlements butonly to Hamlet <strong>in</strong> his mo<strong>the</strong>r’s bedchamber. In <strong>the</strong> words of E.H. Seymour: “If we judge bysheer reason, no doubt we must banish ghosts from <strong>the</strong> stage altoge<strong>the</strong>r, but if we regulateour fancy by <strong>the</strong> laws of superstition, we shall f<strong>in</strong>d that spectres are privileged to be visibleto whom <strong>the</strong>y will (E.H. Seymour “Remarks, Critical, Conjectural, <strong>and</strong> Explanatoryon Shakespeare” <strong>in</strong> Macbeth A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare [New York: DoverPublications Inc., 1963] 211).Shakespeare’s audiences, <strong>and</strong> his plays, were <strong>the</strong> products of <strong>the</strong>ir culture. S<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> validityof any literary work can best be judged by its public acceptance, not to mention its last<strong>in</strong>gpower, it seems that Shakespeare’s ghosts <strong>and</strong> witches were, <strong>and</strong> are, enormously popular.If modern audiences <strong>and</strong> critics f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong>mselves a bit skeptical, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong>y might considerbr<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g along a supply of Coleridge’s “will<strong>in</strong>g suspension of disbelief.” Elizabethans simplyhad no need of it.<strong>Utah</strong> Shakespeare Festival351 West Center Street • Cedar City, <strong>Utah</strong> 84720 • 435-586-788021

Shakespeare’s Day: What They WoreThe cloth<strong>in</strong>g which actors wear to perform a play is called a costume, to dist<strong>in</strong>guish itfrom everyday cloth<strong>in</strong>g. In Shakespeare’s time, act<strong>in</strong>g companies spent almost as much oncostumes as television series do today.The costumes for shows <strong>in</strong> Engl<strong>and</strong> were so expensive that visitors from France were alittle envious. K<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>and</strong> queens on <strong>the</strong> stage were almost as well dressed as k<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>and</strong>queens <strong>in</strong> real life.Where did <strong>the</strong> act<strong>in</strong>g companies get <strong>the</strong>ir clo<strong>the</strong>s? Literally, “off <strong>the</strong> rack” <strong>and</strong> from usedcloth<strong>in</strong>g sellers. Wealthy middle class people would often give <strong>the</strong>ir servants old clo<strong>the</strong>s that<strong>the</strong>y didn’t want to wear any more, or would leave <strong>the</strong>ir clo<strong>the</strong>s to <strong>the</strong> servants when <strong>the</strong>ydied. S<strong>in</strong>ce cloth<strong>in</strong>g was very expensive, people wore it as long as possible <strong>and</strong> passed it onfrom one person to ano<strong>the</strong>r without be<strong>in</strong>g ashamed of wear<strong>in</strong>g h<strong>and</strong>-me-downs. However,s<strong>in</strong>ce servants were of a lower class than <strong>the</strong>ir employers, <strong>the</strong>y weren’t allowed to wear richfabrics, <strong>and</strong> would sell <strong>the</strong>se clo<strong>the</strong>s to act<strong>in</strong>g companies, who were allowed to wear what<strong>the</strong>y wanted <strong>in</strong> performance.A rich nobleman like Count Paris or a wealthy young man like Romeo would wear adoublet, possibly of velvet, <strong>and</strong> it might have gold embroidery. Juliet <strong>and</strong> Lady Capuletwould have worn taffeta, silk, gold, or sat<strong>in</strong> gowns, <strong>and</strong> everybody would have had hats,gloves, ruffs (an elaborate collar), gloves, stock<strong>in</strong>gs, <strong>and</strong> shoes equally elaborate.For a play like Romeo <strong>and</strong> Juliet, which was set <strong>in</strong> a European country at about <strong>the</strong> sametime Shakespeare wrote it, Elizabethan everyday clo<strong>the</strong>s would have been f<strong>in</strong>e—<strong>the</strong>audience would have been happy, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>y would have been au<strong>the</strong>ntic for <strong>the</strong> play.However, s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong>re were no costume shops who could make cloth<strong>in</strong>g suitable for, say,medieval Denmark for Hamlet, or ancient Rome for Julius Caesar, or Oberon <strong>and</strong> Titania’sforest for A Midsummer Night’s Dream, <strong>the</strong>se productions often looked slightly strange—canyou imag<strong>in</strong>e fairies <strong>in</strong> full Elizabethan collars <strong>and</strong> skirts? How would <strong>the</strong>y move?Today’s audiences want costumes to be au<strong>the</strong>ntic, so that <strong>the</strong>y can believe <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> world of<strong>the</strong> play. However, Romeo <strong>and</strong> Juliet was recently set on Verona Beach, with very up-to-dateclo<strong>the</strong>s <strong>in</strong>deed; <strong>and</strong> about thirty years ago, West Side Story, an updated musical version of<strong>the</strong> Romeo <strong>and</strong> Juliet tale, was set <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Puerto Rican section of New York City.Activity: Discuss what <strong>the</strong> affect of wear<strong>in</strong>g “special” clo<strong>the</strong>s is—to church, or to a party.Do you feel different? Do you act different? How many k<strong>in</strong>ds of wardrobes do you have?School, play, best? Juliet <strong>and</strong> Romeo would have had only one type of cloth<strong>in</strong>g each, nomatter how nice it was.Activity: Perform a scene from <strong>the</strong> play <strong>in</strong> your everyday clo<strong>the</strong>s, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>n <strong>in</strong> moreformal clo<strong>the</strong>s. Ask <strong>the</strong> participants <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> spectators to describe <strong>the</strong> differences between<strong>the</strong> two performances.22<strong>Utah</strong> Shakespeare Festival351 West Center Street • Cedar City, <strong>Utah</strong> 84720 • 435-586-7880

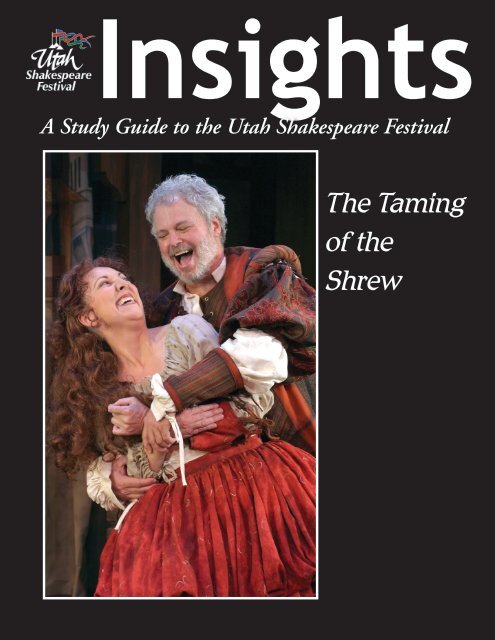

Synopsis: The Tam<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> ShrewBefore <strong>the</strong> play beg<strong>in</strong>s, a lord <strong>and</strong> his huntsmen discover Christopher Sly, a beggar, asleep<strong>and</strong> drunk. They play a trick on him when he wakes up by pretend<strong>in</strong>g that Sly is <strong>the</strong> lord <strong>and</strong><strong>the</strong>y are his servants. To help him recover from his “amnesia,” <strong>the</strong>y present <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g play:*Baptista, a rich gentleman of Padua, has two daughters. The elder, Ka<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>a or Kate, is sobad-tempered that she is known throughout Padua as Kate <strong>the</strong> Shrew (an Elizabethan word foran unpleasant woman). Baptista’s younger daughter, Bianca, is gentle <strong>and</strong> sweet, <strong>and</strong> has twosuitors, Hortensio <strong>and</strong> Gremio. However, Baptista won’t let Bianca get married until someoneagrees to marry Ka<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>a first.Two visitors to Padua arrive with <strong>the</strong>ir servants. The first, Lucentio, <strong>in</strong>stantly falls <strong>in</strong> lovewith Bianca, <strong>and</strong> disguises himself as a teacher so he can see her more often. The second visitor,Petruchio, has come to Padua <strong>in</strong> search of a rich wife <strong>and</strong> hears that Kate is rich <strong>and</strong> pretty, buthas an awful temper. Petruchio resolves to marry this famous wildcat <strong>and</strong> teach her how to bean agreeable wife. Baptista, with some misgiv<strong>in</strong>gs, gives his permission.Then follows <strong>the</strong> famous woo<strong>in</strong>g scene. Whatever Ka<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>a says, Petruchio is gentle withher <strong>and</strong> tells her he’s determ<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>the</strong>y shall marry. They fight—she loudly <strong>and</strong> angrily, show<strong>in</strong>gwhy she was called a shrew. He, on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r h<strong>and</strong>, praises her sweet <strong>and</strong> courteous words. Atthat po<strong>in</strong>t, Baptista arrives <strong>and</strong> Petruchio announces that he <strong>and</strong> Ka<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>a are to be marriedSunday.On Sunday, Petruchio arrives late for <strong>the</strong> wedd<strong>in</strong>g, dressed like a clown, <strong>and</strong> behaves rudely<strong>in</strong> church. But <strong>the</strong> marriage is performed anyway. Then Petruchio refuses to stay for <strong>the</strong> wedd<strong>in</strong>gd<strong>in</strong>ner <strong>and</strong> sets out for his house with Ka<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>a.They have an awful journey, with Petruchio behav<strong>in</strong>g like a maniac. When <strong>the</strong> newlywedsarrive home, Petruchio is even stranger. He throws <strong>the</strong> d<strong>in</strong>ner on <strong>the</strong> floor, pretend<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong>food is not good enough for Kate, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>n dismantles <strong>the</strong> bed, say<strong>in</strong>g it’s a mess as well. Ino<strong>the</strong>r words, he behaves just like Ka<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>a used to.The next day Petruchio behaves <strong>the</strong> same way, yell<strong>in</strong>g at <strong>the</strong> servants <strong>and</strong> forbidd<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>mto give his new wife anyth<strong>in</strong>g to eat or let her rest. By this time, she is will<strong>in</strong>g to be nice toher husb<strong>and</strong>, because she is both very tired <strong>and</strong> very hungry. She also f<strong>in</strong>ds herself stick<strong>in</strong>g upfor <strong>the</strong> servants, when before her marriage she’d found fault with everyth<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> everyone.Petruchio tempts her with some food but, s<strong>in</strong>ce she isn’t quick enough to say thank you, takes itaway aga<strong>in</strong>.He <strong>the</strong>n decides to take her back for a visit to Baptista <strong>and</strong> orders a new gown for her. (Herold one had got spoiled on <strong>the</strong> journey.) Aga<strong>in</strong> Petruchio f<strong>in</strong>ds fault with it, <strong>and</strong> won’t let Katewear her new cloth<strong>in</strong>g, but says <strong>the</strong>y’ll travel <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir old clo<strong>the</strong>s.Next Petruchio orders his horses be readied, say<strong>in</strong>g it was only seven o’clock. Kate correctshim, say<strong>in</strong>g it is noon. Petruchio replies: Are you still disagree<strong>in</strong>g with me? Until you agree,we’re not leav<strong>in</strong>g. Petruchio, you see, is try<strong>in</strong>g to teach Kate that life is more comfortable ifpeople agree with each o<strong>the</strong>r.F<strong>in</strong>ally <strong>the</strong>y set out <strong>and</strong> have ano<strong>the</strong>r disagreement Petruchio say<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> moon is sh<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<strong>and</strong> Kate argu<strong>in</strong>g it is <strong>the</strong> sun. He threatens to take her back to his house unless she agrees withhim <strong>and</strong> Kate, weary of all this argu<strong>in</strong>g, says he can call it <strong>the</strong> moon if he wants.Petruchio has one last test for her: <strong>the</strong>y meet an old man <strong>and</strong> Petruchio calls him a “fairmaiden,” look<strong>in</strong>g at Kate. She agrees <strong>the</strong> old man is fair, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>n Petruchio contradicts heraga<strong>in</strong>. So she changes her op<strong>in</strong>ion to agree with him <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>y cont<strong>in</strong>ue <strong>the</strong>ir journey.<strong>Utah</strong> Shakespeare Festival351 West Center Street • Cedar City, <strong>Utah</strong> 84720 • 435-586-788023

When Petruchio <strong>and</strong> Kate arrive <strong>in</strong> Padua, <strong>the</strong>y go to Baptista’s to celebrate Bianca’s marriageto Lucentio, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> marriage of one of Bianca’s former suitors, Hortensio, to a richwidow.Petruchio bets Lucentio <strong>and</strong> Hortensio that Kate is more agreeable than <strong>the</strong>ir wives. Theo<strong>the</strong>r two husb<strong>and</strong>s agree, sure of w<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g. Lucentio sends his servant <strong>in</strong> search of Bianca,but she sends back word that she was busy. Then Hortensio sends for his wife, but <strong>the</strong> widowreplies that if Hortensio wants her, he should come to her. Petruchio <strong>the</strong>n comm<strong>and</strong> Kate tocome, <strong>and</strong>, to everyone’s amazement, Kate comes immediately, br<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r two wives,<strong>the</strong>n proceeds to <strong>in</strong>struct <strong>the</strong> women on how to have a happy marriage.The play ends happily, with everyone agree<strong>in</strong>g that Petruchio <strong>and</strong> Kate have made a happymarriage.*The action to this po<strong>in</strong>t is called The Induction <strong>and</strong> is not <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> many productions.24<strong>Utah</strong> Shakespeare Festival351 West Center Street • Cedar City, <strong>Utah</strong> 84720 • 435-586-7880

Characters: The Tam<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> ShrewChristopher Sly: A drunken t<strong>in</strong>ker, Sly is brought unconscious to a rich nobleman’s house,where <strong>the</strong> nobleman <strong>and</strong> his household dress him <strong>in</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ery, give him good food <strong>and</strong> evena “wife,” <strong>and</strong> conv<strong>in</strong>ce him he is <strong>the</strong> lord of <strong>the</strong> house. When a troupe of travel<strong>in</strong>g playersarrives at <strong>the</strong> house, it is for him that <strong>the</strong>y perform The Tam<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> Shrew.Baptista M<strong>in</strong>ola: A weathy gentleman of Padua <strong>and</strong> Ka<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>a <strong>and</strong> Bianca’s fa<strong>the</strong>r, Baptista isa harried fa<strong>the</strong>r, hav<strong>in</strong>g difficulty marry<strong>in</strong>g his two daughters because <strong>the</strong> older one is anotorious shrew. He is not, however, an object of sympathy. He ignores <strong>the</strong> question ofhis daughters’ happ<strong>in</strong>ess <strong>in</strong> seek<strong>in</strong>g mates for <strong>the</strong>m, <strong>and</strong> Ka<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>a may be a shrew chieflybecause of <strong>the</strong> way he treats her.V<strong>in</strong>centio: An old merchant of Pisa <strong>and</strong> Lucentio’s fa<strong>the</strong>r, V<strong>in</strong>centio is extremely fond ofhis son <strong>and</strong> is grief-stricken when he discovers that Lucentio may have come to harm.He arrives <strong>in</strong> Padua amidst much confusion <strong>and</strong> is almost jailed as an imposter beforeLucentio arrives <strong>and</strong> clears matters up.Lucentio: A young student <strong>in</strong> love wtih Bianca, Lucentio changes clo<strong>the</strong>s with his servant<strong>and</strong> offers himself as Bianca’s tutor, thus ensur<strong>in</strong>g he can woo Bianca privately. He ultimatelydoes w<strong>in</strong> her h<strong>and</strong>, although both he <strong>and</strong> Bianca are immature <strong>and</strong> no match forPetruchio <strong>and</strong> Ka<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>a.Petruchio: A gentleman of Verona, Petruchio arrives <strong>in</strong> Padua look<strong>in</strong>g for a wife <strong>and</strong> is soonpo<strong>in</strong>ted toward Ka<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>a, whom he roughly courts <strong>and</strong> quickly marries. His characterhas two levels. On <strong>the</strong> surface, he appears to be rough <strong>and</strong> unfeel<strong>in</strong>g, but underneath itall he is <strong>in</strong>telligent <strong>and</strong> underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g--<strong>and</strong> deeply <strong>in</strong> love with his new wife. Certa<strong>in</strong>ly heis somewhat less than gentle, but he has a keen sense of humor <strong>and</strong> is <strong>the</strong> perfect matchfor Ka<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>a.Gremio: An elderly <strong>and</strong> wealthy suitor of Bianca, Gremio gets “Cambio” (<strong>the</strong> disguisedLucentio) <strong>the</strong> pose as tutor to her, on <strong>the</strong> underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g that he will woo her on hisbehalf; however, Lucentio woos <strong>and</strong> w<strong>in</strong>s her for himself.Hortensio: Ano<strong>the</strong>r suitor for Bianca’s h<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> an honest friend of Petruchio, Hortensio isbasically a good man but perhaps a bit foolish. He cont<strong>in</strong>ues his suit of Bianca withoutencouragement from her, but f<strong>in</strong>ally ab<strong>and</strong>ons it, declar<strong>in</strong>g “k<strong>in</strong>dness <strong>in</strong> women, not<strong>the</strong>ir beauteous looks, / Shall w<strong>in</strong> my love” (4.2.41-42).Tranio: Lucentio’s ligh<strong>the</strong>arted <strong>and</strong> mischievous servant, Tranio changes clo<strong>the</strong>s <strong>and</strong> positionswith Lucentio so his master can woo Bianca. He accepts this with some reluctance <strong>in</strong>itially,but soon warms to <strong>the</strong> role.Biondello: Lucentio’s servant, Biondello assumes <strong>the</strong> role of Tranio’s servant when Tranioassumes <strong>the</strong> role of <strong>the</strong>ir master.Grumio: Petruchio’s comic servant, Grumio is ra<strong>the</strong>r dense, but not stupid. He has a keensense of humor <strong>and</strong> a great love of jokes <strong>and</strong> tricks.Curtis: Petruchio’s servant.PedantKa<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>a: Baptista’s daughter <strong>and</strong> Bianca’s older sister, Ka<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>a is known throughout Paduaas “Kate <strong>the</strong> Curst”; however, she has a much deeper character than <strong>the</strong> term wouldimply. She appears mean to Bianca, but only because she has cont<strong>in</strong>ually been second<strong>in</strong> her fa<strong>the</strong>r’s affections. The transformation which she undergoes after she marriesPetruchio is not one of character, but one of attitude. She alters dramatically from <strong>the</strong>bitter <strong>and</strong> accursed shrew to <strong>the</strong> obedient <strong>and</strong> happy wife when she discovers that her<strong>Utah</strong> Shakespeare Festival351 West Center Street • Cedar City, <strong>Utah</strong> 84720 • 435-586-788025

husb<strong>and</strong> loves her enough to help her, <strong>in</strong> contrast to those who treated her badly. Beneath<strong>the</strong> surface <strong>the</strong> shrew is not a shrew at all.Bianca: Baptista’s daughter <strong>and</strong> Ka<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>a’s younger sister, Bianca is an unk<strong>in</strong>d sister <strong>and</strong> later adisobedient wife. She fosters her fa<strong>the</strong>r’s attitude of favoritism for herself <strong>and</strong> dislikefor Ka<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>a by play<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> part of a noble victim. Her disregard for <strong>the</strong> wishes of hernew husb<strong>and</strong>, Lucentio, leads to grim speculation as to what her behavior may be when<strong>the</strong>y have been married longer. Ironically, as <strong>the</strong> play ends, she is more of a shrew than hersister.Widow: The third wife <strong>in</strong> this play of comparisons, <strong>the</strong> Widow marries Hortensio after hef<strong>in</strong>ds he has lost Bianca to Lucentio. At Lucentio’s banquet she loses her husb<strong>and</strong> a wagerwhen she does not come obediently when he calls.26<strong>Utah</strong> Shakespeare Festival351 West Center Street • Cedar City, <strong>Utah</strong> 84720 • 435-586-7880

About <strong>the</strong> PlayThe Tam<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> Shrew was written sometime between 1590 <strong>and</strong> 1594. It is rooted <strong>in</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rpopular stories of <strong>the</strong> time. A play titled The Tam<strong>in</strong>g of a Shrew was popular <strong>in</strong> London at <strong>the</strong> sametime as Shakespeare’s own play. Humorous “he verses she” battle stories have been popular throughouthistory from <strong>the</strong> Greek play Lysistrata to our modern romantic film comedies, like The Proposal.Shakespeare touches on this <strong>the</strong>me aga<strong>in</strong> with ano<strong>the</strong>r of his popular comedies, Much Adoabout Noth<strong>in</strong>g.In Shakespeare’s full script, <strong>the</strong> story of Kate <strong>and</strong> Petruchio’s love is presented as a play with<strong>in</strong>a play. A group of players put on <strong>the</strong> show as part of a prank <strong>the</strong>y are pull<strong>in</strong>g on tavern drunkardcalled Christopher Sly. This device allows Shakespeare to br<strong>in</strong>g an Italian comedy closer to homeby hav<strong>in</strong>g it presented as if <strong>in</strong> Engl<strong>and</strong>. Padua is located <strong>in</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn Italy <strong>and</strong> was know as a placeof easy liv<strong>in</strong>g with rich food <strong>and</strong> materialistic people. Shakespeare used Italy for several of his plays<strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g deceit, romance, <strong>and</strong> little s<strong>in</strong>ful pleasures.As appeal<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> humorous as <strong>the</strong> play is, it touches on some very important <strong>the</strong>mes forShakespeare’s time, <strong>and</strong> our own, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> delicacy of fa<strong>the</strong>r-daughter relationships, <strong>the</strong> nature<strong>and</strong> dangers of physical, verbal, <strong>and</strong> emotional abuse, <strong>the</strong> plausibility of love at first sight, <strong>and</strong> whatreally makes a happy marriage.In <strong>the</strong> last fifty years <strong>the</strong> play has become a battleground for fem<strong>in</strong>ists, some of whom feelPetruchio’s treatment of Kate is cruel <strong>and</strong> debas<strong>in</strong>g; however, few can argue that Kate did notdeserve at least a small taste of her own medic<strong>in</strong>e. Once <strong>the</strong> play has ended it becomes <strong>the</strong> audience’spart to decide who are <strong>the</strong> w<strong>in</strong>ners <strong>and</strong> who are <strong>the</strong> losers <strong>in</strong> this battle of <strong>the</strong> sexes.<strong>Utah</strong> Shakespeare Festival351 West Center Street • Cedar City, <strong>Utah</strong> 84720 • 435-586-788027