Grandmothers: A Learning Institution - Basic Education and Policy ...

Grandmothers: A Learning Institution - Basic Education and Policy ...

Grandmothers: A Learning Institution - Basic Education and Policy ...

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

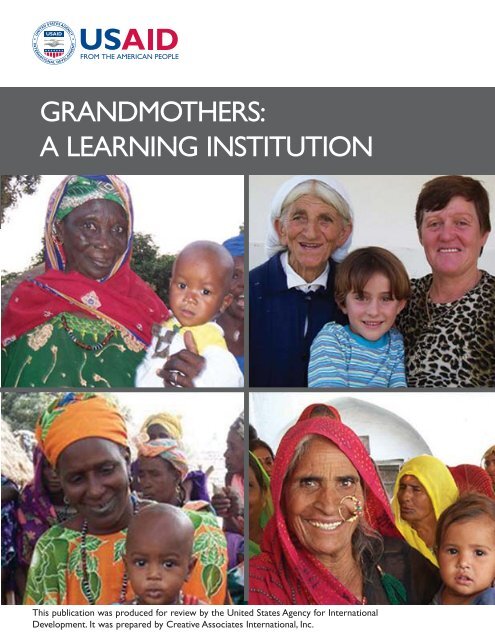

GRANDMOTHERS:A LEARNING INSTITUTIONThis publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for InternationalDevelopment. It was prepared by Creative Associates International, Inc.

Prepared by:Judi Aubel, PhD., MPHThe Gr<strong>and</strong>mother ProjectPhoto Credit:Judi AubelPrepared for:Creative Associates International, Inc.<strong>Basic</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>Policy</strong> Support (BEPS)United States Agency for International Development (USAID)Contract No. HNE-1-00-00-0038-00August 2005ACKNOWLEDGMENTSThe author would like to especially thank Don Graybill <strong>and</strong> Sean Tate for their commitment tothe realization of this publication. Thanks also go to Vicky Franz, Sean Tate <strong>and</strong> Cynthia Pratherfor their editing assistance. Special thanks to Jim Hoxeng at USAID without whose support itwould not have been possible to produce this publication.

GRANDMOTHERS:A LEARNING INSTITUTIONDISCLAIMERThe author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agencyfor International Development (USAID) or the United States Government.

CONTENTSACRONYMS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .viiEXECUTIVE SUMMARY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .ixI. INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1II.WHY INCLUDE GRANDMOTHERS IN CHILD DEVELOPMENTPROGRAMS? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3Conceptual Framework . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5Factors Limiting the Inclusion of <strong>Gr<strong>and</strong>mothers</strong> inChild Development Programs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7<strong>Gr<strong>and</strong>mothers</strong>’ Roles in Different Cultures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .10Core Roles of <strong>Gr<strong>and</strong>mothers</strong> Across Cultures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14Development Policies Support <strong>Gr<strong>and</strong>mothers</strong>’ Inclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .19III. HOW HAVE CHILD DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMS INVOLVEDGRANDMOTHERS? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .21Programs Involving <strong>Gr<strong>and</strong>mothers</strong> . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .21Early Childhood Development <strong>and</strong> Primary <strong>Education</strong> . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .21Newborn Health . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .22Maternal <strong>and</strong> Child Health <strong>and</strong> Nutrition . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .23HIV/AIDS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .25Community Responses to Including <strong>Gr<strong>and</strong>mothers</strong> . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .26IV.A CLOSER LOOK AT INVOLVING GRANDMOTHERS: MALI . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .29Developing a Gr<strong>and</strong>mother-Inclusive Strategy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .29Utilizing Nonformal <strong>Education</strong> Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .30Results of the Nonformal <strong>Education</strong> Activities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .34V. GRANDMOTHERS:A LEARNING INSTITUTION SUMMARYOF CONCLUSIONS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .39VI. RECOMMENDATIONS FOR BASIC EDUCATION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .43Questions for <strong>Education</strong> Program Planners . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .43Recommendations for <strong>Basic</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Planners . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .43APPENDIX A: METHODOLOGY USED IN THIS REVIEW . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .53APPENDIX B: ANNOTATED REFERENCES ON THE ROLE OFGRANDMOTHERS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .55REFERENCES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .71GRANDMOTHERS:THE LEARNING INSTITUTIONv

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYSociety itself fails when it isolates the young <strong>and</strong> the old from one another.Teresa Scott Kincheloe,Native American EducatorThe educational needs of children inAfrica, Asia, Latin America, <strong>and</strong> ThePacific are immense. A major chalgovernments, civil society organilenge forzations, <strong>and</strong> international developmentagencies is to develop strategies to promotethe educational development ofthese children, most of whom live in economicallypoor environments.To address this challenge there has beenconsiderable investment <strong>and</strong> many successesin identifying research-based interventionsto promote children’s educationaldevelopment as part of their overallgrowth. In many cases, however, efforts tointegrate these interventions into family<strong>and</strong> community contexts have not systematicallybuilt on <strong>and</strong> optimized existingroles, values, <strong>and</strong> resources at the locallevel.Since education is an integral aspect ofchildren’s development, this paper examinesexisting evidence regarding the role ofsenior women, referred to in this paper as“gr<strong>and</strong>mothers,” 1 in children’s overalldevelopment, 2 including education, in nonwesternsocieties (in Africa, Asia, LatinAmerica,The Pacific, Aboriginal Australia,<strong>and</strong> Native North America).The paperalso identifies the extent to which policiespromoting the well-being of children supportgr<strong>and</strong>mothers’ inclusion in childdevelopment programming. It highlightsprograms around the world that haveexplicitly involved gr<strong>and</strong>mothers <strong>and</strong>explores in some detail how one of theseprograms was designed to ensure gr<strong>and</strong>mothers’involvement. It concludes byexploring strategies to ensure the involvementof gr<strong>and</strong>mothers in future basic educationinitiatives for children.The review of the literature, policy, <strong>and</strong>programs is framed by several key conceptsthat are not always taken intoaccount in the design of child developmentprograms around the world. Theyinclude: a systems approach; an assetsbasedapproach; cultural roles <strong>and</strong> valuesas a foundation for program design;respect for elders <strong>and</strong> their experience;<strong>and</strong> social capital. The perspective on childdevelopment programming that emergesfrom the combination of these conceptspoints to the need to view gr<strong>and</strong>mothersas key actors in family systems <strong>and</strong> as aninvaluable resource for promoting optimalchild development at that level.1 In this paper, the term “gr<strong>and</strong>mothers” refers to experienced, senior women in the household who are knowledgeable about allmatters related to the health, development <strong>and</strong> well-being of children <strong>and</strong> their mothers. This includes not only maternal <strong>and</strong>paternal gr<strong>and</strong>mothers, but also aunts <strong>and</strong> other older women who act as advisors to younger men <strong>and</strong> women <strong>and</strong> who participatein caring for children.2 Child development, as used throughout this paper, refers to the development <strong>and</strong> continued growth of a child’s emotional, intellectual,<strong>and</strong> physical well-being.GRANDMOTHERS:THE LEARNING INSTITUTIONix

Given the relatively limited published literatureon this topic, the sources of informationreviewed include not only publishedmaterial but also unpublished gray literature3 <strong>and</strong> key informant interviews with avariety of academics, anthropologists, educationalists,international developmentagency staff, <strong>and</strong> NGO field staff in differentcountries. From analysis of the availableinformation, a series of core roles ofgr<strong>and</strong>parents, <strong>and</strong> specifically of gr<strong>and</strong>mothers,were identified that appear toexist across cultures:• All cultures recognize the critical roleof gr<strong>and</strong>parents as guides <strong>and</strong> advisorsto the younger generations.• In all cultures gr<strong>and</strong>parents play gender-specificroles related to childdevelopment.• <strong>Gr<strong>and</strong>mothers</strong> are responsible fortransmitting cultural values.• <strong>Gr<strong>and</strong>mothers</strong>’ child-rearing expertiseis acquired over a lifetime.• In all cultures gr<strong>and</strong>mothers areinvolved in multiple aspects of thelives of children <strong>and</strong> families at thehousehold level.• The roles of gr<strong>and</strong>mothers appear tobe universal whereas much of theirknowledge <strong>and</strong> practices are culturally-specific.• <strong>Gr<strong>and</strong>mothers</strong> are both directly <strong>and</strong>indirectly involved in promoting thewell-being of children.• <strong>Gr<strong>and</strong>mothers</strong> influence the attitudes<strong>and</strong> decisions made by male familymembers regarding children’s wellbeing.• Some of gr<strong>and</strong>mothers’ practices arebeneficial for child development,whereas others are not.• <strong>Gr<strong>and</strong>mothers</strong> have a very strongcommitment to promoting thegrowth <strong>and</strong> development of theirgr<strong>and</strong>children.• Compared to younger women,gr<strong>and</strong>mothers generally have moretime to spend <strong>and</strong> patience withyoung children.• Most gr<strong>and</strong>mothers are interested inincreasing their knowledge of “modern”ideas about child development.• <strong>Gr<strong>and</strong>mothers</strong>’ knowledge comesprimarily from their own mothers<strong>and</strong> their peers.• Many gr<strong>and</strong>mothers have a collectivesense of responsibility for children<strong>and</strong> women in the community.• Some gr<strong>and</strong>mothers feel that theirstatus as advisors in child <strong>and</strong> familydevelopment is diminishing.The overarching conclusion that emergesfrom the review of the available literatureis that gr<strong>and</strong>mothers are present in all cultures<strong>and</strong> communities, that they have considerableexperience <strong>and</strong> influence relatedto all aspects of child development, <strong>and</strong>that they are strongly committed to promotingthe well-being of children, theirmothers <strong>and</strong> families.The review then examines policy guidelinesfrom key international agencies thatsupport child development programmingat the community level. <strong>Policy</strong> statementsfrom UNICEF, the internationalConsultative Group on Early Childhood3 Internal company documents or unpublished documents, such as project reports.xUNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT

<strong>Education</strong>, the Bernard Van LeerFoundation, <strong>and</strong> UNESCO all advocate forstrengthening the capacity of family membersto respond to children’s needs. Forexample, UNICEF states that programsshould identify “existing strengths of communities,families, <strong>and</strong> social structures” <strong>and</strong>“build on local capacity, encourage unity,<strong>and</strong> strength” (2001, 17). <strong>Policy</strong> statementssuch as these suggest, but do not explicitlystate, that gr<strong>and</strong>mothers should be involvedin child development programs.Unfortunately, such policy guidelines supportinggr<strong>and</strong>mother inclusion are reflectedto a very limited extent in actual programs.The second part of the review involvesidentifying child development programs thatexplicitly involve gr<strong>and</strong>mothers. In spite ofthe fact that gr<strong>and</strong>mothers play a significantrole in all aspects of child health <strong>and</strong> developmentat the household level, few programshave explicitly identified <strong>and</strong> involvedthem as key actors. Often in programs thatfocus on younger “mothers” some gr<strong>and</strong>mothersmay participate. However, thenumber of child development programstrategies that have deliberately includedgr<strong>and</strong>mothers as a priority communitygroup is miniscule when compared with thevast number of programs implementedacross the world.This is especially true inbasic education programs.A small number of projects were identifiedthat have involved gr<strong>and</strong>mothers in someway. The gr<strong>and</strong>mother-inclusive projectsreviewed deal with a variety of child developmentissues including early childhooddevelopment (ECD), primary education,newborn health, maternal <strong>and</strong> child health<strong>and</strong> nutrition, <strong>and</strong> HIV/AIDS. 4 Short summariesare presented on each of theseprojects. Although few in number, <strong>and</strong>often poorly documented, these experiencesillustrate how programs can acknowledgegr<strong>and</strong>mothers’ role <strong>and</strong> past experience,actively involve them, <strong>and</strong> in so doingstrengthen their knowledge <strong>and</strong> skills. Inprograms where a gr<strong>and</strong>mother-inclusiveapproach has been adopted, there hasbeen very positive feedback from gr<strong>and</strong>mothers,from other community members,<strong>and</strong> from development staff. In most casestheir involvement appears to have contributedto increased program results.The paper then looks closely at one projectin particular.The experience of Helen KellerInternational in Mali illustrates how childdevelopment programs can work withgr<strong>and</strong>mothers in order to improve thehealth <strong>and</strong> well-being of children <strong>and</strong> theirmothers. This case study describes theactivities of the project <strong>and</strong> details the nonformaleducation methodology that was akey to engaging gr<strong>and</strong>mothers, gaining theirconfidence, <strong>and</strong> helping them to learn. It isthrough this methodology that gr<strong>and</strong>mothersfelt empowered in their roles as communityhealth advisors.CONCLUSIONSBased on the review of the literature onthe roles of gr<strong>and</strong>mothers in different nonwesterncultures, analysis of the policies ofkey international organizations that promotechild development, <strong>and</strong> a review ofchild development projects that haveexplicitly engaged gr<strong>and</strong>mothers, a series ofover-arching conclusions was formulated.These include:4 The projects identified predominantly fall in the category of health-related interventions, but as demonstrated by this paper’srecommendations, the roles played by gr<strong>and</strong>mothers in these health-related interventions are potentially transferable to basiceducation projects.GRANDMOTHERS:THE LEARNING INSTITUTIONxi

THERE IS LIMITED DOCUMENTATION OFGRANDMOTHERS’ ROLES.Analysis <strong>and</strong> documentation of gr<strong>and</strong>mothers’roles in different societies is quite limited.The results of many studies on differentchild development topics either completelyignore, or give minimal attention to,gr<strong>and</strong>mothers’ roles <strong>and</strong> influence at thehousehold level. This can be explained inpart by negative stereotypes of gr<strong>and</strong>mothersheld by many developmentorganizations <strong>and</strong> in part by the narrowmodels used as a basis for data collection.PREVALENT ASSESSMENT METHODOLO-GIES FAIL TO EXAMINE HOUSEHOLDROLES AND RELATIONSHIPS.The methodologies used in formative studieson child development topics mostoften focus narrowly on individual knowledge,attitudes, <strong>and</strong> practices (KAP) ofwomen/mothers. There is a need foralternative assessment methods based ona more systemic, anthropological frameworkthat looks at social structures, roles,<strong>and</strong> relationships in households that influenceattitudes <strong>and</strong> practices related tochild development. In a more systemicapproach, gr<strong>and</strong>mothers’ experience <strong>and</strong>roles at the household level would certainlybe analyzed.GRANDMOTHERS CONTRIBUTE TO CUL-TURAL CONTINUITY.The cultural dimension of developmentprograms has generally been neglected,though there is a growing concern that thisis a dangerous trend that can contribute tothe loss of cultural values <strong>and</strong> identity.<strong>Gr<strong>and</strong>mothers</strong> play a critical role in transmittingcultural values <strong>and</strong> practices toyounger generations, thereby contributingto the maintenance of cultural identity inan increasingly culturally homogeneousworld.GRANDMOTHERS’ PLAY AN INFLUEN-TIAL ROLE IN CHILDREN’S DEVELOP-MENT ACROSS CULTURES.While documentation on gr<strong>and</strong>mothers’roles is relatively limited, the available evidencedoes show that in virtually all nonwesternsocieties in Africa, Asia, LatinAmerica,The Pacific, <strong>and</strong> in indigenous culturesin North America <strong>and</strong> Australia, seniorwomen, or gr<strong>and</strong>mothers, play a centralrole in child-rearing. In all of these societiesthey are looked to as advisors of theyounger generations based on their age<strong>and</strong> experience, though in many cases theirstatus is diminishing. Across cultures thereare a series of core roles played by gr<strong>and</strong>motherswhile at the same time there isconsiderable variability in their culture-specificbeliefs <strong>and</strong> practices.FEW CHILD DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMSEXPLICITLY INVOLVE GRANDMOTHERS.In spite of the fact that gr<strong>and</strong>mothers playa significant role in all aspects of childhealth <strong>and</strong> development at the householdlevel, few child development programshave explicitly identified <strong>and</strong> involved themas key actors. This review analyzes theextent to which they have been involvedin five key program areas related to childdevelopment: early childhood development,primary school education, maternal<strong>and</strong> child health <strong>and</strong> nutrition, childhygiene, <strong>and</strong> HIV/AIDS. It was concludedthat in all of these areas the involvementof gr<strong>and</strong>mothers has been very limited.xiiUNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT

SEVERAL FACTORS CONTRIBUTE TO THELIMITED INCLUSION OF GRANDMOTH-ERS IN CHILD DEVELOPMENT PRO-GRAMS.Several factors appear to contribute to thefact that few programs have identifiedgr<strong>and</strong>mothers as priority communityactors <strong>and</strong> actively involved them in communitystrategies. First, many developmentagencies <strong>and</strong> staff have negative biasesagainst gr<strong>and</strong>mothers related to their ‘age,’‘inability to learn’ <strong>and</strong> ‘resistance to change.’Second, the models used as a basis fordesign of child development programs,borrowed from the west, tend to focus on‘mothers,’ <strong>and</strong> sometimes ‘parents,’ whileignoring the significant role <strong>and</strong> influenceof elder household actors in virtually allnon-western societies.A FEW SUCCESSFUL GRANDMOTHER-INCLUSIVE CHILD DEVELOPMENT PRO-GRAMS DO EXIST.Although there are relatively few examplesof child development programs that haveexplicitly involved gr<strong>and</strong>mothers, thoseexperiences do illustrate how programscan acknowledge gr<strong>and</strong>mothers’ roles <strong>and</strong>past experience, actively involve them, <strong>and</strong>in so doing strengthen their knowledge<strong>and</strong> skills. In programs where a gr<strong>and</strong>mother-inclusiveapproach has been adopted,feedback from gr<strong>and</strong>mothers, fromother community members, <strong>and</strong> fromdevelopment staff has been very positive<strong>and</strong> in most cases their involvementappears to have contributed to increasedprogram results.THERE IS A GAP BETWEEN POLICYSTATEMENTS AND GRANDMOTHERS’INCLUSION IN CHILD DEVELOPMENTPROGRAMS.<strong>Policy</strong> statements from key internationalagencies involved in children’s developmentadvocate for strengthening thecapacity of all family members to respondto children’s needs. By extrapolation, suchpolicy priorities imply that programsshould involve senior family members,including gr<strong>and</strong>mothers. In reality, thereare few programs in which gr<strong>and</strong>mothersare explicitly <strong>and</strong> actively involved. Thenon-inclusion of gr<strong>and</strong>mothers in childdevelopment programs represents a significantinconsistency with international policyguidelines.GRANDMOTHER LEADERS AND NET-WORKS SHOULD BE VIEWED AS SOCIALCAPITAL.Social capital is defined as “the glue thatkeeps communities together <strong>and</strong> that isrequired for a collective <strong>and</strong> sustainedresponse to community needs.” Whilethere is much discussion of the need to“strengthen existing community structures”in community development programs, limitedattention has been given to thepotential represented by natural gr<strong>and</strong>motherleaders <strong>and</strong> their social networksfor promotion of children’s development.Several experiences empowering thesegroups show how efforts to strengthenthem can contribute to enhancing a community’ssocial capital <strong>and</strong> to sustainingcommunity action for children’s development.GRANDMOTHERS:THE LEARNING INSTITUTIONxiii

GRANDMOTHERS ARE RECEPTIVE TO THEUSE OF NONFORMAL EDUCATIONAPPROACHES THAT BUILD ON THEIREXISTING KNOWLEDGE.In experiences in several countries, nonformal,adult education methods have beenvery successfully used with groups ofgr<strong>and</strong>mothers. They were very receptiveto these methods <strong>and</strong> their positiveresponse can probably be explained by thefact that the approach reinforced their culturally-definedrole as respected advisors ofyounger women <strong>and</strong> children while helpingthem to acquire new knowledge <strong>and</strong> practicesrelated to child health <strong>and</strong> development.All of these conclusions support the needto more actively involve gr<strong>and</strong>mothers inchild development projects in the future,given their critical role in child developmentin non-western societies, the internationalpolicies that support this orientation, <strong>and</strong>the positive outcomes of community programsthat have adopted a gr<strong>and</strong>motherinclusiveapproach.RECOMMENDATIONSThe paper concludes with a number of recommendationsfor ways to increase gr<strong>and</strong>mothers’involvement in basic educationstrategies. Around the world, families <strong>and</strong>communities acknowledge that gr<strong>and</strong>mothersplay an influential role in the socialization,acculturation, <strong>and</strong> care of children asthey grow <strong>and</strong> develop. However, basiceducation programs have not seriouslytaken this role into consideration. The recommendationsincluded in the paper aremeant to stimulate thought on how toinvolve gr<strong>and</strong>mothers, utilize their acceptedroles within a community, <strong>and</strong> account fortheir influence on children’s educationaldevelopment. The following recommendations,grouped into five categories <strong>and</strong> summarizedbelow, are not meant to be definitivebut rather to stimulate thought on howto involve gr<strong>and</strong>mothers <strong>and</strong> utilize theirrole <strong>and</strong> influence on children’s educationaldevelopment in the family <strong>and</strong> community.INCREASE TEACHER AND STUDENTAWARENESS OF GRANDMOTHERS’ ROLEAND POTENTIAL CONTRIBUTION.• Develop participatory training exercisesto help teachers reflect on therationale for including gr<strong>and</strong>mothersas partners in school educationalactivities <strong>and</strong> then develop strategiesfor including them.• Analyze family <strong>and</strong> community systemsas an input to program development.• Create alternative assessment tools.• Generate criteria for inter-generationalsensitivity.INTEGRATE TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGEAND SKILLS IN SCHOOL CURRICULA.• Interview gr<strong>and</strong>mothers concerningtheir roles in education.• When revising curricula or developingteaching materials, pictures of gr<strong>and</strong>mothers,quotes from gr<strong>and</strong>mothers,<strong>and</strong> characters in stories should beincluded.• Use components of “Service-<strong>Learning</strong>” <strong>and</strong> constructivist approachesto collect data from gr<strong>and</strong>mothers<strong>and</strong> incorporate them into the curriculum.xivUNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT

– Who am I? Assign children to askfamily members, including gr<strong>and</strong>mothers,to answer the child’s question:“Who am I?”This is an activityto help children define their ownidentity, in the family, <strong>and</strong> in thecommunity.– Living History. Assign children tointerview elders in their family orneighborhood, including gr<strong>and</strong>mothers,on a topic related to the historyof the neighborhood or village.Teachers can make this a part of thehistory curriculum.– Make curriculum relevant.– Build Ownership of the school curriculumby the community.– Making connections between the“old way” <strong>and</strong> the “new”.INTEGRATE TRADITIONAL VALUES INTOTHE CURRICULUM.• Collect stories, proverbs, <strong>and</strong> songs,<strong>and</strong> analyze the values expressed inthem. Use these traditional materialsas a basis for discussion of cultural values<strong>and</strong> of the similarities <strong>and</strong> differencesbetween traditional <strong>and</strong> modernvalues.DEVELOP PARTNERSHIPS BETWEENGRANDMOTHERS AND SCHOOLS.• Encourage families to create homeenvironments that support success inschool.• Encourage gr<strong>and</strong>mothers, who oftenhave more free time than mothers, towalk children to school to assure theirsafety.• Identify stories told by gr<strong>and</strong>mothersin the community that relate to thecurriculum <strong>and</strong> use these stories asteaching tools. Invite these seniorwomen to tell stories in special storytellingsessions at schools or in informalsettings.USE PARTNERSHIPS TO PROMOTESCHOOL IMPROVEMENT.• Empower parents to participate inschool planning for curriculum content,school climate, <strong>and</strong> staff development.• Identify gr<strong>and</strong>mother leaders <strong>and</strong> networks.• Form Gr<strong>and</strong>parent-Parent-TeacherAssociations.• Empower families to learn to use theircollective power to advocate forschool change.• Involve community elders, includinggr<strong>and</strong>mothers, gr<strong>and</strong>fathers, <strong>and</strong> religiousleaders, in providing input forquality control of schools <strong>and</strong> teacherperformance.Many of these recommendations do notdepend on large amounts of financialresources. They simply introduce newapproaches to project development thatutilize the knowledge, experience, <strong>and</strong>enthusiasm gr<strong>and</strong>mothers have for children’sdevelopment. By exploring theserecommendations, child development programswill be able to access a wider rangeof resources—including gr<strong>and</strong>mothers’experience, their networks, <strong>and</strong> their influenceover families—<strong>and</strong>, therefore, generategreater potential for sustainability.GRANDMOTHERS:THE LEARNING INSTITUTIONxv

I. INTRODUCTION“There is probably no other role that is so nearly universal yet soheterogeneously defined as gr<strong>and</strong>parenthood”SmolakPromoting the education, health, <strong>and</strong>well-being of children in developingcountries is a priority for governments, many civil society groups, <strong>and</strong> internationalorganizations. While almost allchildren are embedded in family <strong>and</strong> communitystructures, in most cases developmentprograms narrowly target children,often mothers, <strong>and</strong> in some cases parents.Gr<strong>and</strong>parents are present in all communities,<strong>and</strong> in all societies they are expectedto contribute significantly to the growth<strong>and</strong> development of children. The roles ofgr<strong>and</strong>fathers <strong>and</strong> gr<strong>and</strong>mothers are gender-specific<strong>and</strong> it is the senior women, orgr<strong>and</strong>mothers, who are expected to play apredominant role given their own experiencebearing <strong>and</strong> educating children. Childfocuseddevelopment efforts, however,rarely acknowledge or involve these experiencedresource persons in programs.The Swedish communicologist, AndreasFuglesang (1982) referred to gr<strong>and</strong>mothersas a veritable “learning institution,”alluding to their vast experience <strong>and</strong> theroles they play in transmitting to youngergenerations the knowledge <strong>and</strong> skillsrequired to survive in each society.While there appear to be few developmentprograms that have explicitlyinvolved gr<strong>and</strong>mothers as resource persons,in the community health field therehave been several recent <strong>and</strong> very positiveexperiences. In Laos, Senegal, <strong>and</strong> Mali,gr<strong>and</strong>mothers played key roles in healthpromotion strategies.The results of each ofthese experiences revealed that gr<strong>and</strong>motherswere open to new ideas <strong>and</strong>practices when appropriate nonformaleducation methods were used <strong>and</strong> thatthey were able to learn <strong>and</strong> change theiradvice <strong>and</strong> practices.Evaluations of these community healthprograms showed that the involvement ofgr<strong>and</strong>mothers contributed to improvinghousehold maternal <strong>and</strong> child health practices.For example, in a nutrition educationprogram in Senegal, in households wheregr<strong>and</strong>mothers were involved in the nonformalactivities, more than 90 percent ofall infants were appropriately breastfed(they were given only breast milk for thefirst six months; exclusive breastfeeding).Conversely, in families where gr<strong>and</strong>motherswere excluded from educational activitieswith younger women, only about 30percent of these women reported thatthey were able to exclusively breastfeedtheir infants (Aubel et al, 2004). Positiveresults using a gr<strong>and</strong>mother-inclusiveapproach were also documented in Maliwhere gr<strong>and</strong>mothers were involved innonformal education activities on newbornhealth, <strong>and</strong> in Laos where they participatedGRANDMOTHERS:THE LEARNING INSTITUTION1

in educational activities on home treatmentof childhood illnesses.The over-arching conclusion drawn fromthese several experiences using a gr<strong>and</strong>mother-inclusiveapproach is that communitystrategies that harness the support ofgr<strong>and</strong>mothers can contribute to increasingthe impact of development programs. Inaddition, involving them in developmentprograms can lead to greater appreciationof the contribution of elders to family <strong>and</strong>community well-being, increased recognitionof positive cultural values <strong>and</strong> traditions,<strong>and</strong> stronger inter-generational communication.Efforts to strengthen theknowledge <strong>and</strong> leadership skills of gr<strong>and</strong>mothersto promote family <strong>and</strong> communitywell-being contribute to increasing asociety’s social capital, a critical componentof sustainable development.Based on these positive outcomes workingwith gr<strong>and</strong>mothers, Creative AssociatesInternational, Inc. decided to support theexploration of ways in which gr<strong>and</strong>motherscould similarly be involved in basiceducation initiatives. In this context, it wasdecided to carry out a review of existingliterature, first, on the role played bygr<strong>and</strong>mothers in different societies in children’soverall growth <strong>and</strong> development,<strong>and</strong> second, on development programsthat have explicitly involved gr<strong>and</strong>mothersas resource persons <strong>and</strong> the strategies <strong>and</strong>methodologies they employed to do so.This review had three objectives:• To explore the relevance of includinggr<strong>and</strong>mothers in child developmentprograms;• To identify child development programsthat have explicitly involvedgr<strong>and</strong>mothers <strong>and</strong> explore theapproaches used to elicit their participation;<strong>and</strong>• To formulate recommendations forincreasing involvement of gr<strong>and</strong>mothersin future basic education programs.The findings related to these objectivesshape this publication.2 UNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT

II. WHY INCLUDE GRANDMOTHERS INCHILD DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMS?“When an old person dies it is as though a whole library had burned down.”Amadou Hampâté Ba,Malian philosopher 1900-1991The education <strong>and</strong> developmentneeds of children, <strong>and</strong> of poor familiesin general in Africa, Asia, LatinAmerica, <strong>and</strong> The Pacific are enormous.Ensuring optimal growth in both needssectors represents a particularly complex<strong>and</strong> difficult challenge. In order to easethis burden, many international agencies,governments, civil society groups, <strong>and</strong> communitynetworks are investing in education<strong>and</strong> development programs to supportchildren’s overall development.Yet, frequentlythese programs are missing fundamentalelements that are critical to thedevelopment of effective <strong>and</strong> sustainableprojects. One such element is the need tobuild on existing family <strong>and</strong> communitystructures <strong>and</strong> strategies (UNICEF 2001).At the global level there is also a broadconsensus regarding the need to strengthenthe capacity of families <strong>and</strong> communitiesto optimize children’s development.<strong>Policy</strong> statements of various internationalorganizations involved in child developmentprojects support the need to bolsterexisting family <strong>and</strong> community actors <strong>and</strong>resources. For example, UNICEF assertsthat successful programs for children arecharacterized by strategies that “use theexisting strengths of communities, families,<strong>and</strong> social structures… respect cultural values,build on local capacity, encourage unity<strong>and</strong> strength” within families <strong>and</strong> communities(2001, 17).While international policy guidelines clearlyarticulate the need for child developmentprograms to build on existing family <strong>and</strong>community systems, in many cases thesepriorities have not been fully translatedinto programming strategies. By ignoringthis need, programs are under-utilizingavailable resources at the family <strong>and</strong> communitylevels <strong>and</strong> ultimately limiting theirprospects of sustainability.This weakness in many national <strong>and</strong> internationalchild development programsappears to stem from the fact that programdevelopment is not based on anaccurate <strong>and</strong> holistic underst<strong>and</strong>ing of family<strong>and</strong> community systems in different culturalcontexts (Bronfenbrenner 1979;Berman et al. 1994). In most cases, relativelylimited attention is placed on underst<strong>and</strong>ingthe roles, authority, <strong>and</strong> decisionmakingpatterns among various householdactors that influence practices contributingto children’s growth <strong>and</strong> development.There is often only superficial underst<strong>and</strong>ingof the socio-cultural dimensions of famGRANDMOTHERS:THE LEARNING INSTITUTION3

“A gr<strong>and</strong>mother’s underst<strong>and</strong>ingof Indian identityis an invaluable perspectivethat she is ableto pass on to her gr<strong>and</strong>children.<strong>Gr<strong>and</strong>mothers</strong>as-culture-transmittermay be one of the mostsignificant contributionsto the perpetuation ofthe Indian community.”M.M. SchweitzerAmerican Indian<strong>Gr<strong>and</strong>mothers</strong>:Traditions<strong>and</strong> Transitionsily systems, including the social hierarchywithin families associated with age <strong>and</strong>experience that dictates individualbehavior to a great extent.Along with the absence of adequateassessment of the components <strong>and</strong>dynamics of family systems in differentsocio-cultural contexts, there is a tendencyto erroneously project onto nonwesternsocieties western concepts ofnuclear families, <strong>and</strong> of autonomouswomen <strong>and</strong> couples who operate independentlyof family systems. This orientation/tendencyis seen in education programsthat involve only “parents,” definedas children’s mothers <strong>and</strong> fathers, <strong>and</strong>child health programs that narrowlyfocus on women of reproductive age oron the mother-child dyad. Limited focushas been directed at underst<strong>and</strong>ing theroles of <strong>and</strong> including other non-parentalfamily <strong>and</strong> community actors in childdevelopment strategies. In almost allcases, in child development programs,both at the initial assessment phase <strong>and</strong>in the design of community-orientedstrategies, senior household <strong>and</strong> communitymembers, including gr<strong>and</strong>parents,are excluded.Anthropologist Margaret Mead (1970)was among the first social scientists topoint out the critical role played bygr<strong>and</strong>parents in transmitting from onegeneration to the next the “model” ofhow things should be done in life, includinghow children should be nurtured <strong>and</strong>taught how to survive in each society.Similarly communicologist, AndreasFuglesang (1982) discussed the multifacetedrole that gr<strong>and</strong>mothers play inthe socialization process of the youngergenerations <strong>and</strong> asserted that gr<strong>and</strong>mothersconstitute a veritable “learninginstitution” in the community.Professor Scarlett Epstein, from theInstitute of Development Studies at theUniversity of Sussex, has pointed out thecritical role played by gr<strong>and</strong>mothers ininculcating in children the moral, social,<strong>and</strong> cultural norms that determine individualbehavior later in life (Epstein 1993,2003). She states that in most developingcountry settings, gr<strong>and</strong>mothers’ influenceis great, given that they live close totheir offspring <strong>and</strong> are respected bythem. <strong>Gr<strong>and</strong>mothers</strong> provide ongoing“informal training” both to their children<strong>and</strong> gr<strong>and</strong>children. Epstein has been anoutspoken advocate of the need fordevelopment activities related to children<strong>and</strong> women’s health <strong>and</strong> developmentto acknowledge <strong>and</strong> build on therole of gr<strong>and</strong>mothers.In the so-called “developed” world, thereis a tendency for gr<strong>and</strong>parents to bemuch less involved in the socialization<strong>and</strong> care of gr<strong>and</strong>children than was historicallythe case. Nevertheless, in allcultures, gr<strong>and</strong>parents continue to beinvolved <strong>and</strong> to influence, to a greater orlesser extent, the lives <strong>and</strong> developmentof the younger generations. Recentefforts to promote intergenerationallearning in western countries, for exampleby involving elders in school programs,is a sign of the recognition of thecontribution gr<strong>and</strong>parents can make tothe development of the youngest membersof society. In most parts of Africa,Asia, Latin America, <strong>and</strong> The Pacific,4 UNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT

gr<strong>and</strong>parents continue to play a criticalrole in guiding <strong>and</strong> supervising the youngergenerations; parents <strong>and</strong> children alike. Invirtually all cases it is the gr<strong>and</strong>motherswho play a greater <strong>and</strong> more direct role ina child’s development than do gr<strong>and</strong>fathers,though this does not deny theinvolvement of gr<strong>and</strong>fathers in someaspects of a child’s overall development.It is important to note that in this review“gr<strong>and</strong>mother” is used as a “generic” termto refer not only to biological or paternalgr<strong>and</strong>mothers but to all of the older, experiencedwomen in a family who serve asadvisors to younger family members onmultiple aspects of child <strong>and</strong> family development.In addition to the veritablegr<strong>and</strong>mothers, this can include aunts <strong>and</strong>unmarried senior women who play a roleas family advisors. In patrilineal societies,the child’s gr<strong>and</strong>mother is the woman’smother-in-law.Clearly traditional family <strong>and</strong> communitystructures are in transition in virtually allsocieties. In this context, it is important toask ourselves, “Do child development programsserve to bolster traditional family<strong>and</strong> community structures, roles <strong>and</strong> values,including the role of experienced, seniorfamily members, for the benefit of children<strong>and</strong> their families?” Or, “Are childdevelopment programs merely acquiescingto the increasing rift between local, traditionalroles, values, <strong>and</strong> resources <strong>and</strong> globalizingforces of ‘modernity’ <strong>and</strong> ‘individualism’that is contributing to breaking downthe social cohesion of more traditionalcommunities systems around the world?”CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORKThis review of literature, policy, <strong>and</strong> programsis framed by several key conceptsthat are often not given much attention inthe design of child development programs.These concepts include a systemsapproach; an assets-based approach; culturalstructures; roles <strong>and</strong> values as a foundationfor program design; respect for elders<strong>and</strong> their experience; <strong>and</strong> social capital.Each of the concepts is explained below,along with its relevance to the discussionof gr<strong>and</strong>mothers’ involvement in childdevelopment programs. As will be seen,each of these concepts has implications forhow child development strategies <strong>and</strong> programsare designed, both in terms of analyzingcommunity realities <strong>and</strong> in developinginterventions.• Systems ApproachIn many past child development programsthere has been a tendency toadopt a reductionist approach thatfocuses only on children, or on thechild-mother dyad. This approach simplifiesthe parameters dealt with bothin initial assessments <strong>and</strong> in programdesigns. However, such an approach isinadequate in so far as it provides alimited vision of the household systemof which children are a part. Thisrestricted focus on only certain membersof the household necessarily concealsthe roles of household actors inaddition to mothers, namely older siblings,men, <strong>and</strong> senior women, <strong>and</strong> theinfluence they have on each otherrelated to children’s well-being. In contrast,in a systems approach children’sneeds are analyzed <strong>and</strong> addressed in" Successful programsuse the existingstrengths of communities,families, <strong>and</strong>social structures….toprovide the best forchildren."UNICEFThe State of theWorld's Children:Early ChildhoodGRANDMOTHERS:THE LEARNING INSTITUTION5

“Culture tells peoplehow to view the world,how to experience itemotionally <strong>and</strong> howto behave in relationto other people, supernaturalforces <strong>and</strong> inrelation to their environment.It is the ‘lens’through which peopleperceive <strong>and</strong> underst<strong>and</strong>the world inwhich they live.”J. Sengendo“Culture <strong>and</strong> Health”in F. MatrassoRecognizing Culture:ASeries of BriefingPapers on Culture <strong>and</strong>DevelopmentUNESCOrelation to the roles, attitudes <strong>and</strong>practices of all key family <strong>and</strong> communityactors. In this more holisticapproach, program strategies aim toreinforce the various actors within thefamily system, including gr<strong>and</strong>mothers,who influence children’s well-being.• Assets-based ApproachWhile all families <strong>and</strong> communitieshave inadequacies <strong>and</strong> problems, theperception of those weaknesses byprograms <strong>and</strong> staff significantly determinetheir attitudes toward them <strong>and</strong>the type of interventions developed.Kretzmann <strong>and</strong> McKnight (1993) suggestthat often in social programs thefocus is put on the problems or“deficits” in a community, while inthose same communities there areundoubtedly certain resources, or“assets” on which to build.They referto the latter option as an “assetsbasedapproach.” Applied to childdevelopment programs, this latterapproach implies that programsshould, first, identify existing family<strong>and</strong> community resources that contributeto child development, <strong>and</strong>second, aim to strengthen them.<strong>Gr<strong>and</strong>mothers</strong> constitute one of theexisting resources that can bestrengthened in such programs.• Cultural Structures, Roles, <strong>and</strong> Valuesas a Foundation for ProgramDevelopmentWhile lip service is often given to theimportance of cultural realities todevelopment programs, often thecultural dimension is absent fromdevelopment planners’ frameworks<strong>and</strong> program designs (Serageldin1994). In the past few years, itappears that this dimension of developmentplanning is being givensomewhat greater attention. FormerWorld Bank Vice President IsmailSerageldin argues that “A culturalframework is … a sine qua non tohave relevant, effective institutionsrooted in authenticity <strong>and</strong> traditionyet open to modernity <strong>and</strong> change”(Serageldin, 19).To some extent the cultural dimensionhas been taken into account indevelopment projects, yet too often“culture” is considered in a verysuperficial way <strong>and</strong> is equated with acultural practice (i.e. how initiationceremonies for young girls are organized)(Pelto 2003). In this regard,social psychologist Pepitone (1981)proposes a more inclusive definitionof “culture” composed of two interrelatedfacets. First, there are thesocial structures <strong>and</strong> organizations inwhich individuals exist in relation tothe family, kinship, roles, hierarchies,<strong>and</strong> communication nets. Second,there are the normative systems thatinclude the values <strong>and</strong> beliefs promotedwithin the family system thataffect behavior. In child developmentprograms, <strong>and</strong> development programsin general, the tendency hasbeen to ignore the first facet. Ifchild development programs aim tobuild on existing culturally-definedfamily <strong>and</strong> community roles, hierarchies,<strong>and</strong> communication nets, thisimplies that gr<strong>and</strong>mothers <strong>and</strong> gr<strong>and</strong>6 UNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT

mother networks should be involvedin efforts to improve the well-beingof children. In addition, building onexisting cultural systems is more likelyto contribute to the sustainability ofchild development strategies, includingbasic education initiatives.• Respect for Elders <strong>and</strong> Their Age <strong>and</strong>ExperienceIn contrast to western societies,where youth is glorified, in virtually allnon-western societies there is muchmore respect for elders, their age,<strong>and</strong> their experience. In Mali there isan often-heard proverb in bamana 5that refers to the wisdom of the elders:“Whatan elder can see sittingunder a tree, a younger person cannotsee even if he/she climbs up tothe top of the tree.”In virtually all non-western societies, from ayoung age children are taught that theyshould respect, listen to, <strong>and</strong> learn fromtheir elders. This traditional cultural valuestill holds considerable weight in mostnon-western societies but it is being jeopardizedby the encroachment of alternative,often foreign, values that aggr<strong>and</strong>izeyouth <strong>and</strong> accomplishment in the formalschooling system <strong>and</strong> give less credence tothe wisdom of the elders. For example, inMalian communities, many gr<strong>and</strong>parentssaid (Touré <strong>and</strong> Aubel, 2004) that mostdevelopment programs that have come totheir villages only involve “young people”<strong>and</strong> “those who have gone to school”thereby excluding most elders in the community.Such an approach contradicts traditionalvalues in which the elders areexpected to play an advisory role withyounger members of the society.• Social CapitalMany development programs aim tostrengthen “human capital” i.e., theskills <strong>and</strong> capacity of individual communitymembers. In contrast,“socialcapital” refers to the strength of therelationships between people. It hasbeen referred to as the “glue” thatkeeps a community together <strong>and</strong> thatis required for a collective <strong>and</strong> sustainedresponse to community needs.Social capital refers to the networkswithin a community that are basedon trust <strong>and</strong> mutual support thatcontribute to a sense of belonging,promote inclusion <strong>and</strong> involvementof different community factions, <strong>and</strong>are empowered to promote selfreliance.Increased social capital is anasset for promoting <strong>and</strong> sustainingchildren’s development within thecommunity.In the past, gr<strong>and</strong>mothers were not systematicallyinvolved in child developmentprograms at the community level. Each ofthe concepts discussed above supports theidea that gr<strong>and</strong>mothers constitute a valuablecommunity resource that needs to betaken into consideration in the design ofchild development programs. In this review,these several concepts will be referred toin the subsequent discussions of gr<strong>and</strong>mothers’roles, child development policies,<strong>and</strong> programs.FACTORS LIMITING THEINCLUSION OF GRANDMOTHERSIN CHILD DEVELOPMENTPROGRAMS.The explanation for the relatively limited“This is a rule in oursociety, you must listento what your eldersadvise. Sincetime began peoplehave learned fromtheir elders.”Community Leader,Navoi, Uzbekistan“Social capital is acommunity’s humanwealth. It is a powerfulmotor for sustainabledevelopmentbecause it harnesseslocal capacity,indigenous knowledge,<strong>and</strong> selfreliance.”H. Gould“Culture <strong>and</strong> SocialCapital” in F.Matrasso, RecognizingCulture: A Series ofBriefing Papers onCulture <strong>and</strong>Development,UNESCO5 Bamana is the language spoken by the Bambara people of Mali.GRANDMOTHERS:THE LEARNING INSTITUTION7

attention given to gr<strong>and</strong>mothers’ roles inthe development literature, <strong>and</strong> their limitedinclusion in community developmentprograms, appears to be related both to aseries of negative biases toward them <strong>and</strong>programming models that tend to excludethem. In this section, these constrainingfactors are explored, after which evidenceof gr<strong>and</strong>mothers’ roles in different societiesaround the world is presented.In all societies around the world, seniorwomen, or ‘gr<strong>and</strong>mothers,’ are present incommunities <strong>and</strong> neighborhoods, <strong>and</strong> theyare part of most extended families. Giventhis reality, it is surprising that there is verylittle discussion in the development literatureof their role <strong>and</strong> influence on the livesof children, families, <strong>and</strong> communities. Ofthe numerous documents that have beenwritten dealing with ECD, education, nutrition,health, <strong>and</strong> hygiene of young children,very few even mention the role of gr<strong>and</strong>mothers.When they do, they are oftenreferred to in a negative light.There are a series of negative stereotypes,or biases, regarding the role of olderwomen, which tend to discredit theirexperience <strong>and</strong> limit their inclusion in childdevelopment programs.First, there is a widespread belief thatolder women do not really influence thechild development practices of youngerfamily members, including older siblings.This attitude can be attributed, in part, tothe curricula used in professional trainingschools in most developing countries onchild development, education, health, <strong>and</strong>nutrition. These curricula are based primarilyon imported, western programs. Suchtraining programs are, therefore, based onthe western, nuclear family in which youngparents are responsible for their own children<strong>and</strong> in which elders play a relativelylimited role. In numerous instances <strong>and</strong>countries, child health/development staffhas denied the significance of the role <strong>and</strong>contribution of gr<strong>and</strong>mothers until theywere presented with empirical evidencesupporting that substantive role.The second often-heard bias is that whileolder women may be influential in thefamily, their influence is generally “negative.”It is often said that their ideas <strong>and</strong> practicesare “old fashioned,” “out-of-date,”<strong>and</strong>/or “harmful.” This attitude is oftenexpressed by child health/developmentworkers in developing countries as well asby program managers in developmentorganizations. For example, health workersoften criticize older women for theiruse of “harmful traditional remedies” <strong>and</strong>consequently discredit gr<strong>and</strong>mothers’ rolein child <strong>and</strong> family health matters. Similarlyearly childhood development practitionersoften criticize gr<strong>and</strong>mothers because theirchildcare practices do not reflect “modernapproaches.”A third bias, that exists particularly wherethere are high illiteracy levels amongstolder women, is that women who are illiterateare not intelligent <strong>and</strong>, therefore,they are unable to comprehend new ideas.This unfortunate bias equates schoollearning with superior intelligence <strong>and</strong>undervalues experiential life learning.Yet a fourth stereotype, which afflictsgr<strong>and</strong>mothers <strong>and</strong> gr<strong>and</strong>fathers alike, is thewidespread belief that older people are8 UNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT

incapable either of learning new things orchanging their ways due to their age. Theessence of the saying in English about olddogs not being able to learn new tricksexists in many cultures. For example, inLaos it is frequently said that “you cannotbend an old piece of bamboo.” Based onthe belief that gr<strong>and</strong>mothers are by natureresistant to change, many developmentpractitioners assume that gr<strong>and</strong>mothersare both unwilling <strong>and</strong> unable to assimilatenew child development knowledge <strong>and</strong>practices.The last factor is the restricted perceptionof older women as being “needy” <strong>and</strong>“dependent” that ignores the many gr<strong>and</strong>motherswho are active <strong>and</strong> resourcefulmembers of households <strong>and</strong> communities.In developing countries where mostwomen marry <strong>and</strong> have their first child bythe time they are twenty, most womenbecome gr<strong>and</strong>mothers at an early age <strong>and</strong>remain active in this role until they are atleast sixty or older. In this sense, the perceptionof gr<strong>and</strong>mothers as generallydecrepit <strong>and</strong> dependent is inaccurate.All of these stereotypes are reinforced byattitudes of ageism, which gerontologistsdefine as the “unwarranted application ofnegative stereotypes to older people”(Fennell et al l988, 97). Ageist attitudes areembedded in western, youth-focused cultures,<strong>and</strong> they appear to influence thethinking of many western-oriented developmentagencies, their policies <strong>and</strong> programs.The combination of these several stereotypesseem to explain the rather negativeattitude in development programs towardgr<strong>and</strong>mothers’ roles <strong>and</strong> experience <strong>and</strong>toward their potential to promote optimalchild development in households <strong>and</strong> communities.While these biases against gr<strong>and</strong>mothersappear to be quite widespread,they can be overcome. In several of thechild development programs (discussedlater) in which an explicit effort was madeto help development staff reexamine theirattitudes toward these senior women, verypositive changes have been observed intheir perceptions of <strong>and</strong> attitudes towardgr<strong>and</strong>mothers.A second factor that works against theinclusion of gr<strong>and</strong>mothers in child developmentprograms comes from the restrictivemodels, or frameworks, typically used bothto assess children’s developmental needs<strong>and</strong> to design program strategies. Asintroduced in the conceptual frameworkused for this review, in most cases,whether programs address ECD, nutrition,health, cognitive development, or otherissues, there is a tendency to assess children’sneeds only at the level of the childor the child-mother dyad. Most programsare not based on a holistic analysis of theinterface between children <strong>and</strong> householdactors, resources, values, <strong>and</strong> interactionrelated to a child’s development.The predominant concepts <strong>and</strong> modelsthat underpin most programs promotingECD, health, nutrition, <strong>and</strong> other developmentissues are rooted in North Americanconcepts from behavioral psychology. Thisis a field that focuses on individuals isolatedfrom their social environment. The moresystemic perspectives on the growth <strong>and</strong>development of children—from ecology,anthropology, community psychology, <strong>and</strong>GRANDMOTHERS:THE LEARNING INSTITUTION9

social work, including family systems theory—havetraditionally had much less influenceon the conceptual orientationsadopted in child development programs.For example, in the child health <strong>and</strong> nutritionfield, there is very limited discussion offamily systems theory (Hartman & Laird1983), which provides tools for <strong>and</strong>insights into intra-household interaction,influence, <strong>and</strong> decision-making.The resultof this predominant orientation is thatmost child development programs adopt anarrow focus on children, their mothers,<strong>and</strong> occasionally their parents, while ignoringother significant family members, suchas gr<strong>and</strong>mothers.In conclusion, it appears that the combinationof several negative stereotypes aboutgr<strong>and</strong>mothers <strong>and</strong> the narrow conceptualmodels used in child development programshave contributed to obscuring therole played by gr<strong>and</strong>mothers, discreditingtheir involvement in children’s developmentat the household <strong>and</strong> communitylevel, <strong>and</strong>, finally, excluding them from childdevelopment programs.Alternatively, as proposed above, if oneadopts a systems approach to the designof child development programs, strategiesshould aim to strengthen the knowledge<strong>and</strong> practices of all key family memberswho are involved, either directly or indirectly,in promoting child health, growth,<strong>and</strong> development.GRANDMOTHERS’ ROLES INDIFFERENT CULTURESIn this section, the roles of senior womenor gr<strong>and</strong>mothers in families <strong>and</strong> communitiesin diverse cultural settings around theworld is reviewed. This includes discussionof the available literature from Africa, Asia,Latin America <strong>and</strong> The Pacific, as well asfrom Native American nations <strong>and</strong>Aboriginal Australia. Many other annotatedreferences from each region of theworld are found in Appendix B.The lastsection in this chapter presents a summaryof what appear to be generic roles ofgr<strong>and</strong>mothers that exist across cultures.AFRICAIn a discussion of child-rearing roles <strong>and</strong>practices in African societies, Apanpa(2002) discusses the constant interactionof gr<strong>and</strong>mothers, aunts, <strong>and</strong> other family<strong>and</strong> community members with African childrenfrom their first days of life. All of thisstimulation contributes to children’s socialization<strong>and</strong> development. Apanpa reportsthat studies conducted in Ug<strong>and</strong>a, Senegal,Botswana,Tanzania, Nigeria, Zambia, <strong>and</strong>South Africa have all shown that Africaninfants’ psychomotor development is precociousas compared with that ofEuropean children. Researchers associatethis with the intense h<strong>and</strong>ling by familymembers, especially by senior women,who interact constantly with infants.In most African societies, in all mattersrelated to the well-being of women <strong>and</strong>their children, there is a clear hierarchy ofauthority in the household of seniorwomen over younger women. For example,Castle (1994) discusses the “hierarchicaltransmission of knowledge” from mother-in-lawto daughter-in-law in the householdcare of sick children in Fulani <strong>and</strong>Humbebe households in Mali. She alsorefers to the “authority <strong>and</strong> superior status10 UNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT

of senior female household members”over younger females in the household(1994, 330). These same patterns arefound in numerous ethnic groups acrossAfrica.ASIAIn Chinese culture, a traditional <strong>and</strong> centralfunction of older women is to care forchildren in the family. Studying Chinesefamily systems in both Singapore <strong>and</strong>Taiwan, Jernigan <strong>and</strong> Jernigan (1992) foundthat this task not only provides an essentialservice to families but it also contributesto older women’s sense of validation <strong>and</strong>purpose in life. According to Dr. Pang(l998), a former Vice-Minister of Health incontemporary mainl<strong>and</strong> China, gr<strong>and</strong>motherscontinue to play an important advisoryrole with their daughters <strong>and</strong> daughters-inlaw.She notes that the advisory roleplayed by gr<strong>and</strong>mothers can be explained,first, by the important Chinese culturalvalue of respect for elders, <strong>and</strong> second, bythe fact that with the “one child policy”most women giving birth are first-timemothers <strong>and</strong> need advice from moreexperienced women on various childcarematters.In line with Dr. Pang’s analysis, recentresearch in Eastern China has revealed theextensive role of paternal gr<strong>and</strong>mothers.In most cases this role involves childcarewhile their daughter-in-laws are workingoutside the home (Yajun et al 1999).<strong>Gr<strong>and</strong>mothers</strong> play a leading role in variousaspects of child development, includingnutrition, hygiene, <strong>and</strong> toilet training, as wellas informal teaching related to Chinese values<strong>and</strong> traditions. When children are sick,gr<strong>and</strong>mothers also play a role in advising<strong>and</strong> treating, often using traditional remedies.In Thail<strong>and</strong>, Professor Sakorn, of theInstitute of Nutrition at Mahidol Universityin Bangkok, a prominent nutritionist inSoutheast Asia, points out the very importantrole played by gr<strong>and</strong>mothers in contemporaryThai society (Sakorn 2003).She states that an important value in Thaiculture is respect for age <strong>and</strong> experience.In this context gr<strong>and</strong>mothers are lookedto for their advice <strong>and</strong> guidance in all mattersrelated to children’s health <strong>and</strong> wellbeing.With many women working eitheroutside the home or in another part ofthe country, the role of gr<strong>and</strong>mothers inchildcare is significant.Available evidence suggests that in CentralAsia, paternal gr<strong>and</strong>mothers play a veryinfluential role in all children’s developmentalmatters <strong>and</strong> have strong influence ontheir daughter-in-laws. In a rapid assessmentconducted recently in southernUzbekistan (Aubel et al 2003) it was concludedthat Uzbek families view the gr<strong>and</strong>mothersas knowledgeable <strong>and</strong> important“general managers” of day-to-day familylife. In matters related to the well-being ofchildren <strong>and</strong> women, both husb<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong>women alike consider them to be thehousehold authorities <strong>and</strong> seek theiradvice. From the time that a child is born,the daughter-in-law is expected to followthe advice of her mother-in-law regardingthe care <strong>and</strong> education of the child.Furthermore, husb<strong>and</strong>s expect their mothersto play this role <strong>and</strong> they expect theirwives to follow the advice provided tothem. In the same region, anecdotal inforGRANDMOTHERS:THE LEARNING INSTITUTION11

mation from Azerbaijan (McNulty 2003;Capps 2004) <strong>and</strong> Kyrgyzstan (Dolotova2003) provides evidence of the stronginfluence of mother-in-laws on the socialization<strong>and</strong> management of children <strong>and</strong>younger women at the household level.In southeast Europe, evidence fromAlbania (HDC 2002; Waltensperger 2004)reveals that the mother-in-law’s centralrole in infant care <strong>and</strong> child rearing is culturally-dictated<strong>and</strong> supported by otherfamily members. The influence of seniorwomen in the family extends to fertilitydecisions, care-seeking during pregnancy,newborn care, <strong>and</strong> socialization of youngchildren in the family <strong>and</strong> community. Inhouseholds where mothers-in-law arepresent, they provide advice <strong>and</strong> oversightto their son’s wives <strong>and</strong> guidance to theirsons on all matters related to the wellbeingof children <strong>and</strong> women.LATIN AMERICAEvidence from several countries in LatinAmerica also shows that in various culturalcontexts older women play an advisoryrole on child development issues at thehousehold level. In Saguaro Indian communitiesin Ecuador, Finerman documentedthe leading role played by senior femalefamily members in health promotion <strong>and</strong>illness management (1989a & 1989b).Similarly, describing household dynamicsaround illness episodes in the Ecuadorianhighl<strong>and</strong>s, McKee (1987) refers to gr<strong>and</strong>mothersas the ”primary medical specialists”within the family, suggesting the essentialrole they play in child <strong>and</strong> family healthmatters. While there is considerable culturaldiversity between the multiple ethnicgroups across Central <strong>and</strong> South America,anecdotal evidence from key informantssuggests that the core roles played bygr<strong>and</strong>mothers in socialization <strong>and</strong> childrearingare similar in Bolivia (Fern<strong>and</strong>ez2000), El Salvador (Velado 2003),Nicaragua (Alvarez 2003) <strong>and</strong> Ecuador(Escobar 2003).NORTH AMERICASchweitzer <strong>and</strong> colleagues (1999) discussthe central role played by gr<strong>and</strong>mothers inchild development in seven contemporaryNative American cultures.Their analysisreveals two critical dimensions of gr<strong>and</strong>mothers’role in child development. First,they are “almost universally engaged inchildcare <strong>and</strong> childrearing” (Schweitzer 8)<strong>and</strong> second, they play a central role in theenculturation process of young NativeAmericans based on their knowledge ofIndian traditions <strong>and</strong> values. They concludethat this second dimension is of invaluableimportance to these minority cultures inNorth America.While it might be assumed that the role ofgr<strong>and</strong>mothers is diminishing in NativeAmerican cultures, Schweitzer’s conclusionrefutes this assumption, “The importanceof gr<strong>and</strong>mothers in earlier times is echoedin gr<strong>and</strong>mothers’ lives today….the continuingimportance of the gr<strong>and</strong>motheringrole” (18). Another significant, <strong>and</strong> perhapssurprising, observation of theseresearchers is that while Native Americangr<strong>and</strong>mothers are committed to preservingtradition, they are simultaneously interestedin adapting to change.Native American educationalist, Sam Suina(2000), discusses the vital teaching role ofNative American gr<strong>and</strong>mothers in convey12 UNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT

ing to children their connectedness withtheir elders, their ancestors, <strong>and</strong> the earth.He discusses the problems of disconnectedness(with traditional values <strong>and</strong> ceremonies)<strong>and</strong> dysfunction in contemporaryNative American families <strong>and</strong> schools <strong>and</strong>the role of wise gr<strong>and</strong>mothers in promotinginterrelatedness <strong>and</strong> continuity inNative beliefs, values, <strong>and</strong> practices. It islargely through storytelling that gr<strong>and</strong>mothershelp children connect with Nativepeople’s language, values, <strong>and</strong> cultural traditions.In various Native American culturesthe vital teaching role of gr<strong>and</strong>mothers isdepicted in a visual image, reproducedeither on paper or in clay, of a large gr<strong>and</strong>motherwith numerous small children ontop of <strong>and</strong> around her. This image profoundlyreflects the dual teaching <strong>and</strong> nurturingrole of gr<strong>and</strong>mothers in NativeAmerican cultures.Similarly, in Sioux culture gr<strong>and</strong>parents playa vital role “as cultural links to the traditionsof the past <strong>and</strong> as isl<strong>and</strong>s of certaintyin ever-changing society.” Native Americaneducationalist Kincheloe (Kincheloe &Kincheloe 1983) describes the importantrole of gr<strong>and</strong>mothers in child developmentfrom the time of birth, as child-care supportfor busy mothers <strong>and</strong> as educatorson all aspects of life. The authors lamentthe fact that formal schools do not incorporatethe knowledge <strong>and</strong> wisdom of theelder, traditional Sioux educators. “Theschools must not contribute to Americansociety’s tendency to push olderAmericans into the background” (136).She asserts that most formal teachersignore the fact that gr<strong>and</strong>parents constitutea valuable resource <strong>and</strong> ensure the“cultural link” in the development of Siouxchildren. She poignantly argues, “Societyitself fails when it isolates the young <strong>and</strong>the old from one another” (135).AUSTRALIA AND THE PACIFICIn all Aboriginal societies in Australia,respect for the family, tradition, <strong>and</strong> theelders are important precepts. Within thisframework, senior Aboriginal women areexpected to serve as advisors <strong>and</strong> guidesfor young women <strong>and</strong> families (Wilson1999; Koori Elders et al. 1999). As regardsthe health <strong>and</strong> well-being of women <strong>and</strong>children, senior women are expected toshare their expertise <strong>and</strong> pass on to themtraditional ways of promoting health <strong>and</strong>healing.In The Pacific there has been virtually nopublished research on the role of gr<strong>and</strong>mothersin children’s development, accordingto well-known public health doctors,Biuwaimai (1997) <strong>and</strong> Kataouanga (1998),public health nutritionist, Susan Parkinson(2003), <strong>and</strong> community development practitioner,Wanga (2002). On the otherh<strong>and</strong>, all four of these key informants stateunequivocally that in all Pacific isl<strong>and</strong> cultures,older women have played in thepast, <strong>and</strong> continue to play, a significant roleat the household level in all matters relatedto child health <strong>and</strong> development.Parkinson states that in both rural, <strong>and</strong> socalled“urban contexts,” senior women playan important role in childcare, <strong>and</strong> particularlywith infants (2003). She states that inboth major ethnic groups in Fiji, theIndigenous Fijians, <strong>and</strong> Indo-Fijians, bothgrannies <strong>and</strong> aunties in the family areimportant household advisors <strong>and</strong> teachGRANDMOTHERS:THE LEARNING INSTITUTION13

“The status of eldersin traditional societiesreflects the fundamentalrole theyplay in the functioning<strong>and</strong> survival ofthose societies.”FugelsangAbout Underst<strong>and</strong>ing:Ideas <strong>and</strong>Observations onCross-CulturalUnderst<strong>and</strong>ingers. She laments the fact that these seniorwomen have generally been excludedfrom health, nutrition, <strong>and</strong> childrearing programsoften on the pretense that they areilliterate.The literature reviewed above shows thatin numerous non-western cultures inAfrica, Asia, Latin America <strong>and</strong> The Pacific,as well as in indigenous cultures in NorthAmerica <strong>and</strong> Australia, gr<strong>and</strong>mothers playa significant role in children’s health <strong>and</strong>development. Based on this review, thefollowing section is a discussion of a seriesof core roles of gr<strong>and</strong>mothers that wouldappear to be universal.CORE ROLES OFGRANDMOTHERS ACROSSCULTURESBased on a synthesis of the literaturereviewed above, as well as that included inAppendix B., on gr<strong>and</strong>mothers’ roles inchild development in different non-westernsocieties, several conclusions emergerelated to a series of core roles <strong>and</strong>expectations of gr<strong>and</strong>mothers that appearto be common across these cultures.While the focus of our discussion is on therole of “gr<strong>and</strong>mothers” given their genderrelatedspecialization in child developmentissues, in some cases the core roles <strong>and</strong>expectations refer more broadly to therole of “gr<strong>and</strong>parents.” The core roles <strong>and</strong>expectations identified across cultures areas follows:• All cultures recognize the critical roleof gr<strong>and</strong>parents as guides <strong>and</strong> advisorsto younger generations.Family members expect gr<strong>and</strong>parentsto play a role in teaching, guiding, <strong>and</strong>advising the younger generations.Resonating Margaret Mead’s words,gr<strong>and</strong>parents are expected to passonto the next generation the“model” for how things should bedone whether it is in Nepal,Colombia, or Nigeria. Furthermore,in virtually all of the non-western culturesrepresented in the reviewed literature,age <strong>and</strong> experience are valued<strong>and</strong> family members are expectedto show respect for the status<strong>and</strong> advice of gr<strong>and</strong>parents.• In all cultures gr<strong>and</strong>parents play gender-specificroles related to childdevelopment.In all societies, different roles are designatedto gr<strong>and</strong>fathers <strong>and</strong> to gr<strong>and</strong>mothers,just as gender-specific rolesare assigned to younger men <strong>and</strong>women. Senior women have primaryresponsibility for socializing youngerfemales to their role in the family <strong>and</strong>society, while senior men have analogousresponsibility for providing informaltraining to male family membersonce they pass childhood, often fromthe age of seven or eight. While inall cases gr<strong>and</strong>mothers are moreinvolved in the care of children <strong>and</strong>women in the family than are gr<strong>and</strong>fathers,given their lifetime experience,the degree of involvement ofgr<strong>and</strong>fathers in childcare varies considerablyfrom one society to another.• <strong>Gr<strong>and</strong>mothers</strong> are responsible fortransmitting cultural valuesWhile gr<strong>and</strong>fathers too, are involvedin this important task, in most soci14 UNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT