HIGHLANDER POINT: A GATEWAY - Floyd County Indiana

HIGHLANDER POINT: A GATEWAY - Floyd County Indiana

HIGHLANDER POINT: A GATEWAY - Floyd County Indiana

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

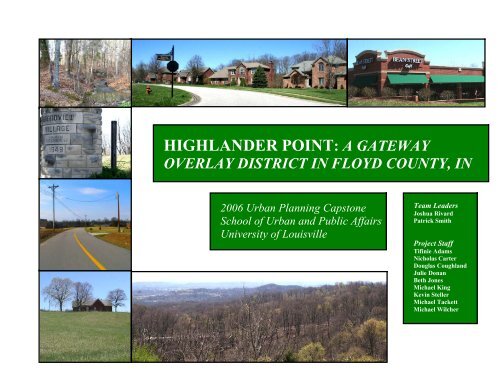

<strong>HIGHLANDER</strong> <strong>POINT</strong>: A <strong>GATEWAY</strong>OVERLAY DISTRICT IN FLOYD COUNTY, IN2006 Urban Planning CapstoneSchool of Urban and Public AffairsUniversity of LouisvilleTeam LeadersJoshua RivardPatrick SmithProject StaffTifinie AdamsNicholas CarterDouglas CoughlandJulie DonanBeth JonesMichael KingKevin StellerMichael TackettMichael Wilcher

TABLE OF CONTENTSProject Overview……………………………………………………………………………………….page 2Planning Process………………………………………………………………………………………page 5Land Use………………………………………………………………………………………………..page 11Transportation…………………………………………………………………………………………..page 16Conservation Design…………………………………………………………………………………...page 23Waste Treatment………………………………………………………………………………………. page 36Greenways, Trails, & Parks……………………………………………………………………………page 45Financing…………………………………………………………………………………………………page 53Special thanks to Don Lopp, J. Martin Rutherford, Carol Norton, and Ted GrossardtMaster of Urban Planning ProgramSchool of Urban and Public AffairsUniversity of LouisvilleMay 2006

PLANNING PROCESS

Planning Process 5IntroductionThe contents of this document wereshaped through a communicative andcollaborative process with various officialorganizations and community members in<strong>Floyd</strong>’s Knobs and <strong>Floyd</strong> <strong>County</strong>. Thefollowing four meetings helped to establishthe recommendations and guidingprinciples of this document:1. <strong>Floyd</strong> <strong>County</strong> Commissioners Meeting2. <strong>Floyd</strong> <strong>County</strong> Plan Commission Meeting3. Community Stakeholder Meeting4. Developers MeetingCommunity Stakeholder Meeting<strong>Floyd</strong> <strong>County</strong> CommissionersMeetingIn a meeting with <strong>County</strong> CommissionersJohn Reisert, Stephen Bush and CharlesA. Freiberger on February 7, 2006, classmembers asked about the Commissioners'vision for the Highlander Point area. Allagreed that the area is currentlyexperiencing a relatively high level ofdevelopment, both commercial andresidential, and that this situation wasexpected to continue into the foreseeablefuture. Mount St. Francis is seen as asignificant positive factor for thecommunity; participants agreed that thislarge parcel should be preserved in itscurrent undeveloped state. A need wasvoiced for more public services, especiallypolice and fire departments, within thearea.There was general agreement thatcommercial development in HighlanderPoint should be confined to sites alongHighway 150, and that any additionalindustrial development is more appropriatefor the Georgetown area.Further residential development was seenas more suitable for parcels "behind"commercial areas and off the mainHighway 150 corridor. Conflicts betweenresidents and business owners hadalready arose in places where the two usesadjoined, and these disputes could beexpected to continue unless preemptiveregulation is put into place. Some sawvalue in developing multi-family and rentalhomes for the area, especially in sitesdirectly adjacent to commercial zones,while others were completely against theidea of any condominiums, lower-incomehousing or apartments. Although there iscurrently virtually no connectivity betweenexisting residential subdivisiondevelopments, the concept was generallyagreed to be a good idea for new projects,especially those in areas within walkingdistance of the commercial core.

Planning Process 6<strong>Floyd</strong> <strong>County</strong> Plan CommissionMeetingIn an informal open discussion with theZoning Ordinance Task Force on February11, 2006, members were asked their viewson current land use issues in theHighlander Point area and their vision offuture development.Several commission members expressedan interest in the possibility of connectingthe area to Kentucky via a bridge thatwould tie Highway 150 to the Gene Snyderloop in Louisville. Members saw futurecommercial development in HighlanderPoint limited to the Highway 150 corridornorth of existing development, but stresseda desire to limit curb cuts and signal lightson the highway. A preference for nodalrather than linear development, to consistof businesses serving the daily needs ofarea residents, was expressed by severalcommission members. There was alsointerest in the establishment of a specialoverlay district to include architectural anddesign standards that would help preservethe rural character of the area.In addition, members raised infrastructureissues related to sewer accessibility andcapacity. They identified a need for furtherstudy of potential expansion of the existingHighlander Point and Georgetownsystems, possibly by connecting theexisting private sewer plants to the publicsystem. They also emphasized a need toidentify potential funding sources forinfrastructure expansion.Participants viewing a design sampleCommunity Stakeholder MeetingFebruary 28th, the 2006 Capstone Studioassisted the <strong>Floyd</strong> <strong>County</strong> Planner’s Officein conducting a stakeholder meeting. Thepurpose of this meeting was to examinesome plan views of hypothetical designscenarios and rate their suitability for theHighlander Point / US 150 corridor. Thehope is that the information gathered fromthe interested members of the communitywill help in determining appropriate landuse for the area.The participants examined a series ofdesign samples, sketched by the 2006 UKLandscape Architecture Capstone,containing varying development patternsand styles. Each sample contained a mixhousing size, commercial activity, streetand sidewalk provision, street networktype, and green space. Accompanying thedesign scenarios were a series of streetlevel sketches also drafted by the UKArchitecture students. With the help of the

Planning Process 7UK Transportation Center, participantsvoted on the suitability of each sampleusing key pad scoring system that allowedfor real-time viewing and discussion of theresults. The following sections examine thehighest and lowest rated design samples.The higher rated samples representdevelopment patterns that participantsfound most appropriate for the HighlanderPoint Gateway.The only negative comments aboutSample #1 included that the housing wasisolated, raising security issues, and that itwas difficult or expensive to gain access toservices like phone or cable television.Sample #1 – Highest rated sampleThe second highest rated sample was #9with a mean score of 5.8 out of 10. Onerespondent commented that this pattern ofdevelopment was a “happy medium”,presumably between development andagricultural space. Another comment wasthat Sample #9 was superior to most of theother samples that depicted higherintensities of land use. Additional positivecomments regarding Sample #9 included:The highest rated sample was #1 with amean score of 7.1 out of 10. Several of theparticipants indicated that this pattern ofdevelopment was the reason they originallymoved to the area. Several communitymembers also advocated against sewerfacilities. The participants made thefollowing additional positive comments inresponse to Sample #1:• Large lots• Not a lot of buildings• No commercial• Less traffic• Less people• No retail• No apartments, no condominiumsSource: 2006 UK Landscape ArchitectureCapstone• An organized version of what we have• Commercial areas are organized• No multi-family• Better that the alternatives• Liked the connectivity• Want to be able to walk to retailParticipants made several negativecomments in regards to Sample #9. Onecommunity member said, ““we don’t like itbut it’s close to the current land use”.Another characteristic that someparticipants did not find suitable was thehigher levels of commercial development.

Planning Process 8Sample #9 – 2 nd Highest rated sampleSource: 2006 UK Landscape ArchitectureCapstoneThe lowest rated were Sample #4 (1.9 outof 10) and Sample #10 (2.3 out of 10).Community stakeholders found theintensity and density of developmentunsuitable for the Highlander PointGateway. Many participants found thedesign scenarios to contain too muchcommercial residential development. Theyfound that density of the residentialdevelopment to be unsuitable for the area.One stakeholder commented that aresidential development with lot sizes lessthan one or two acres would be too dense.Another comment was that the residents ofthe community did not want a bus route.Sketch from Sample #10Source: 2006 UK Landscape ArchitectureCapstoneOverall it seemed that many of thecomments collected at the meeting dealtwith sewage treatment facilities. Many ofthe more vocal community membersindicated that they were against anysewage treatment plant in the <strong>Floyd</strong>’sKnobs or the Highlander Point Gateway.Only a few participants indicated that theyapproved sewage treatment in the area.Several participants were concerned that<strong>Floyd</strong> <strong>County</strong> did not currently have azoning ordinance. Even with the resistanceto higher residential several participantswere interested in “patio-home”development, or similar residentialopportunities that gave retirees furtherhousing options in the area. Onerespondent was adamant that somethingneeds to be done about the traffic onInterstate 64 near US 150Sketch from Sample #4Source: 2006 UK LandscapeArchitecture Capstone

Planning Process 9Developer MeetingOn March 8, 2006, several developerscurrently working projects in the HighlanderPoint area were also asked about theirideas for future commercial and residentialdevelopment. Attendees offered input oninfrastructure, residential and commercialdevelopment and transportation issues.All agreed on a need for higher-densitymixed income housing in the area, to belimited to small, specific sites, as a meansof increasing overall density whilemaintaining the rural character of themajority of developable land. They arealso in favor of Planned Unit Developments(PUDs) and mixed-use development asapproaches that will encourage housingappropriate for residents of diverse agesand income levels and increaseconnectivity. There is also someagreement that regulations encouragingthe use of front porches would helpencourage a sense of community amongHighlander Point residents. As for housingoutside of the limited high-density areas,developers recommend a minimum lot sizeof 12,000 square feet. They expect to seegreen space, continuity and designstandards included in the new countyzoning ordinances. While they anticipatepublic resistance to these ideas, theybelieve that it would be lessened if thepublic were educated as to the positiveaspects of zoning, planning anddevelopment.The developers recommend thatcommercial development be concentratedalong Highway 150 near the I-64interchange, consisting of retail and servicebusinesses to meet the daily needs of arearesidents. Some additional commercialoffice space might be of value, but wouldprobably require some sort of financialincentive to project developers. They sawno need for industrial development in thearea.Transportation was also a major issue fromthe developers' point of view, and theyrecommend that a transportation masterplan be developed. They see the peaktime traffic bottlenecks at the Highway150/I-64 interchange as a majordisincentive to further development, andsuggest that the one-lane ramp fromHighway 150 onto I-64 East be increasedto two. Although they did not object toimpact fees, they seemed to feel that therewas some inequity in the current feeassessment process. They would like tosee a new procedure in place that puts allcounty developers on equal footing.

LAND USE

Land Use 11HousingThe Highlander Point area has a mixture oflow density (one dwelling unit per twoacres) and moderate density (minimum ofone dwelling unit per .85 acre) singlefamilydevelopments that are concentratedalong feeder corridors off US 150. Over 50percent of the housing was developed after1980. The existing housing is insatisfactory condition. The homesgenerally show no major signs ofdilapidation or negligence.Example of Residential Developments found inHighlander PointCurrently the existing developments lackany pedestrian orientated linkagesbetween other residential developmentsand/or the existing commercial core. Thereis a need for pedestrian orientateddevelopments and pathways, asdetermined by visual survey, publiccomments and sound planning principles.This will encourage greater pedestrianaccess and less reliance on vehiculartraffic, cutting down some of thecongestion in the area.Existing Design ElementsThe community has various housing stylesand types within the immediate vicinity ofHighlander Point. The housing styles foundin the community range from typicalsouthern <strong>Indiana</strong> small farmhouses tomore contemporary housing styles. Thehousing stock employs stone, wood andbrick materials, primarily. The area homeare composed of three main forms ofhousing styles: Colonial, Contemporaryand Victorian Style.The Colonial styles do not use typicalmaterials, but employ simple box designwith no fancy architecture. These styles ofhouses fit in well with countryside and ruralsurroundings. The Contemporary style,although modern, does fit into the naturalsurroundings. There is an extensive use ofmixed materials and glass to help thehome conform to the outdoors. The finalstyle common to the area is the CountryStyle. Country style follows the typicalfarmhouse style that typically has pitchedroofs with Gable ends, wood frameconstruction and asymmetrical façades.To preserve and enhance the agreeablecharacteristics found throughout thecommunity; the creation of a pattern bookwould be helpful. The purpose of a patternbook is to encourage quality developmentthat is aesthetically pleasing and enhancesthe architectural quality of neighborhoods.This assist homeowners, builders, andcommunities as they repair, rebuild and

Land Use 12expand their houses and neighborhoods(Northcutt, 2006).Historic StructuresThe area is home to limited historicstructures. The Mt. St. Francis chapel andformer seminary and the Augustus LambHouse US 150 Greek Revival (1860) arethe only known official historical buildingswithin the study area (Sekula 2006).The Highlander Point Gateway Districtlacks a current record of historicallysignificant structures and features. As thecommunity continues to grow, this maybecome a point of contention betweenresidents and developers. An adequateassessment of the historically significantstructures found in the community wouldbe helpful in planning future growth.CommercialThe gateway has a existing commercialnode at the intersection of Old VincennesRoad and US 150. The existingcommercial developments are automobileorientated, with poor pathways forpedestrians. The development consists ofa series of disconnected buildings, withamble parking and connecting lanes. Thereare five entrances into the development,two off Old Vincennes Road and three offSchrieber Road.The development is primarily composed oftypical commercial establishment’srestaurants, dry cleaners, grocery but italso contains some office and retailservices.The existing commercial area has fewpedestrian paths between existingstructures for patrons. As the commercialdevelopment continues to expand, it willbegin to encroach upon the surroundingresidential developments. The new zoningordinances need address settingstandardized buffering requirementsbetween the low-density residential andcommercial uses.Encroaching Commercial DevelopmentIndustrialCurrently there are no existing industrialdevelopments in the Highlander PointGateway.Public/Semi-Public SpacesThe community is home to the Mount SaintFrancis Retreat Center, which has a naturepreserve, including a lake and walkingpaths, which are open to the public. Thefriary is also home to the Mary AndersonCenter for the Arts, founded in 1989. TheMary Anderson Center offers studio spacefor local writers, visual artists, and

Land Use 13musicians. There are three public schoolslocated in this study area: <strong>Floyd</strong> CentralHigh School, Highlander Point MiddleSchool and Galena Elementary School.These serve as community centers as wellas educational institutions.Mount Saint FrancisInfrastructure and PublicServicesFor fire protection, the community reliesupon a collaborative effort from theGeorgetown, Greenville and New Albanyfire departments. The existing fireprotection systems are not proficientenough to protect the addition of newresidential dwellings (McGee 2006). Thecommunity also relies upon the county toprovide police services. The communitydoes not have any immediate facilities forthese services to employ duringemergency events.An updated inventory of the existing waterinfrastructures (water mains, local watersupply, and fire hydrants) would be helpfulin assessing Highland Point’s ability torespond to events. All fire fighting andprotection services should be provided tonew and existing residential developmentsper local fire department codes andjurisdiction (McGee 2006). Conduct an indepthevaluation of all existing fireprotection systems to meet therequirements of local fire codes. Aseparate fire district should be responsiblefor the Highlander Point corridor. Worktoward creating a fire district map, todistinguish all serviceable fire areas for allfire departments.An updated inventory of the existing waterinfrastructures (water mains, local watersupply, and fire hydrants) would be helpfulin assessing the community’s’ ability toadequately respond to emergency events.All fire fighting and protection servicesshould be provided to new and existingresidential developments per local firedepartment codes and jurisdictions

Land Use 14Current ZoningCurrently the entire gateway is under ablanket Agriculture and Residential Zoningordinance. All existing commercialdevelopment in the community has beenpermitted though conditional use permits.The existing commercial developments arepredominately located along the US 150corridor with the major commercial node ofthe gateway located at the HighlanderPoint Commercial Center. The gatewayhas limited agricultural properties currentlyexisting.The current zoning ordinance lacks theability to adequately manage futuredevelopment within the area. Currently theplanning commission is in the process ofevaluating and updating the county zoningordinance. Implementation of strongzoning and possibly an overlay district,would aid county officials in managing thefuture growth expected in the area.The county planning commission andplanner has designated the HighlanderPoint as a growth area.As of summer 2006 the <strong>Floyd</strong> <strong>County</strong>Planning Commission is drafting a zoningordinance. The ordinance is a tool for<strong>Floyd</strong> <strong>County</strong> to guide and manage growthand development in accordance with visionof the <strong>Floyd</strong> <strong>County</strong> Comprehensive Plan.The ordinance should be approved by thefall of 2006.ReferencesComprehensive Plan. (2005).“Cornerstone 2005: A Vision for the future.<strong>Floyd</strong> <strong>County</strong> Comprehensive Land UsePlan Update”Retrieved January 25, 2006 fromhttp://www.floydcounty.in.gov/building_commissioner.aspMcGee, Chuck. Director of <strong>Floyd</strong> <strong>County</strong>Fire Investigative Unit. February 8, 2006.Northcutt, Andrew (2006) Pattern Book forNorfolk Neighborhoods. City of Norfolk.Retrieved April 27, 2006 from:http://www.norfolk.gov/Planning/comehome/Pattern_Book.aspSekula, Greg. Director of SouthernRegional Office, Historic LandmarksFoundation of <strong>Indiana</strong>. February 7, 2006.

TRANSPORTATION

Transportation 16TransportationChart 1: Travel time to work for areaChart Y - Travel time to workIn 2003 the Southern <strong>Indiana</strong> Chamber ofCommerce commissioned a study to gaugehow stakeholders viewed the future of thearea. Members of the community were invitedto provide recommendations on a range oftopics. The final report states that participantsidentified transportation as the most importantissue for southern <strong>Indiana</strong> to address(Southern <strong>Indiana</strong> Chamber of Commerce,2003). The number of reported workers rosefrom 1,979 in 1990 to 2,786 in 2000 for aworkers30%25%20%15%10%5%0%less than 55 - 910 -1415 - 1920 - 2425 - 2930 - 341990 2000minutes35 - 3940 - 4445 - 5960 - 89more than 90Goal 5 of the update seeks to encourageopportunities for multi-modal transportationoptions such as park/ride lots, and pedestrianor bicycle networks. Special considerationshould be directed to the Highlander Pointarea given the very high ratio of single driverautomobile trips to work. Currently mostworkers in <strong>Floyd</strong>s Knobs drive to work, andfrom 1990 to 2000 the area experienced adecrease in workers that carpool (Table 1).growth of 41 percent (U.S. Census Bureau1990, U.S. Census Bureau, 2000). Thesignificant increase in workers resulted froman accelerated increase in residentialdevelopment in the <strong>Floyd</strong>’s Knobs area. Whilethe number of cars on the road hasincreased, the average travel time to workremained almost the same; 21.6 minutes in1990 to 21.3 minutes in 2000 (Chart 1). In2000, the average daily traffic count on Hwy150 adjacent to the Highlander Point retailand office area was 23,035 cars(<strong>Indiana</strong>Department of Transportation, 2000).The 2005 Update to the <strong>Floyd</strong> <strong>County</strong>Comprehensive Plan recommends “SmartGrowth” guidelines for management ofresidential and commercial development(2002). A principle of smart growth is toprovide transportation options for thereduction of traffic congestion, to improve airquality, etc. Smart Growth’s precept ofcreating walk-able communities is ambitiousfor an area hoping to maintain rural character.Table 1 – Means of transportation to workYearDrovealoneCarpool WalkOthermeansWorkedat home1990 86% 9% 1% 0% 4%2000 88% 7% 1% 2% 3%Source: US Census Bureau

Transportation 17The development of commercial and officeuses along Hwy 150 could account for theincrease in workers remaining in the <strong>Floyd</strong>’sKnobs area and the decrease of commutersto Louisville (Chart 2). Commercialdevelopment at Highlander Point hascertainly contributed to an increase in withincountyemployment and within-county homebasedtrips to work.Chart X 2: - Place of of work1990 200049%44%39%34%As a part of the planning process for thisdocument the <strong>Floyd</strong> <strong>County</strong> Commissionersidentified the following transportationconcerns in respect to Highlander PointGateway District:‣‣Limiting signal lights on Hwy 150Setting a limit on the number of curbcuts‣ Coordinating projects and roadimprovements with <strong>Indiana</strong> Departmentof Transportation (INDOT)ConnectivityThere is a lack of connectivity betweenHighlander Point and the surroundingcommunity. Many of the residential areas arelocated on cul-de-sacs. If Highlander Point isto continue to grow with commercial andresidential development, vehicular traffic willtypically increase as well. Poor linkagebetween neighborhoods, commercial areas,and the road network will increase trafficcongestion. Multiple modes of transportationin the county, especially in areas surroundingHighlander Point, are recommended. In termsof functional class, connectivity can beachieved by having the correct progressionform a local feeder road to a collector road toan arterial (City of Bowling Green, 2002).17% 17%in county ofresidenceoutside countyof residenceoutside State ofresidenceSource: US Census BureauLocal roadwayMany areas have no sidewalks

Transportation 18Walking and BicyclingTwo transportation studies that address non-stagesautomobile modes are in the planningfor the area. <strong>Floyd</strong> <strong>County</strong> Public Works isdeveloping a bicycle/pedestrian plan forunincorporated areas in the county (estimatedavailability: 2007). The plan will examinerouting, connectivity to population centers,traffic generation, route identification, priorityof efforts, and estimated costs ofrecommendations (Kentuckiana RegionalPlanning and Development Agency, 2000).The <strong>Floyd</strong> <strong>County</strong> Planner’s office willcomplete a feasibility study regarding usageand facilities requirements of multi-modalfunctions (<strong>Floyd</strong> <strong>County</strong> Comprehensive LandUse Plan Update, 2002). Onerecommendation is to arrange a formalrelationship (MOA) between these offices topool resources for the two multi-modalstudies.The <strong>Floyd</strong> <strong>County</strong> Subdivision ControlOrdinance addresses the need for sidewalks.Subdivisions with a gross area of more thanone lot per acre are required have sidewalkson both sides of all new streets. TheOrdinance also states that if a subdivisionabuts a street that currently has no sidewalks,then the developer must provide exteriorsidewalks within the limit of the subdivision.More opportunities for walking and bikingcould occur through a public greenway or trailsystem. In <strong>Floyd</strong>’s Knobs, the 500-yearfloodplain could serve as the major artery of atrail system. Land for a trail system could beacquired through conservation easements. Aconservation easement (or conservationrestriction) is a legal agreement between alandowner and a land trust or governmentagency that permanently limits uses of theland in order to protect its conservationvalues; it allows landholders to continue toown and use land and to sell it (Land TrustAlliance, 2006). When a conservationeasement is donated to a land trust, thelandowner relinquishes some of the rightsassociated with the land. For example, thelandowner might give up the right to buildadditional structures, while retaining the rightto grow crops (Land Trust Alliance, 2006).Greenways and trails offer improvedconnectivity while promoting active andhealthy transportation options. A linear parksystem that would include shared pedestrianand bike path connections to majordestinations in the community could connectwith existing and improved sidewalk systems.Walking TrailSource: Indy Greenways

Transportation 19Access Management and TrafficCalmingPoorly designed intersections raise safetyconcerns in and around the Highlander Pointshopping center. Traffic is increasingly hard tomanage at the busy intersections at US150/Luther Road and US 150 /Old VincennesRoad. One problem is that there are too manydecision points at these intersections. Forexample, the Highlander Point shoppingcenter has three points of access alongSchreiber Lane. If the area continues todevelop in this manner, congestion andcollisions will progressively continue. It isessential that some form of control beexercised such that benefits can be achievedfrom growth and economic development whilemaintaining transportation safety and mobility(Kentucky Transportation Center, 2004).of safety, capacity and speed. It providesbenefits to the communities, property ownersand developers because it protects the levelof service for thoroughfares and discouragesthe unplanned subdivision of land. A guidingprinciple is to limit the number of points wherethe movement of through traffic can come intoconflict with traffic moving in anotherdirection.Many traffic safety concerns could be solvedwith traffic calming techniques. Reworkingthe I-64 and Hwy 150 interchange withmedians and landscaping would slowmotorists and help reduce speeding. Addinga stop light at Hwy 150 and Luther would slowdown drivers and ease access to and fromthe road to the highway.Figure 1 – Conflict PointsAccess Management is about providing andmanaging access to development whilepreserving the regional flow of traffic in termsSource: City of Bowling Green, 2002

Transportation 20ReferencesCity of Bowling Green. (2002), AccessManagement. Revised May, 2005)<strong>Floyd</strong> <strong>County</strong> Comprehensive Land Use PlanUpdate. (2002). Cornerstone 2005: A Visionfor the Future,<strong>Indiana</strong> Department of Transportation.(2000).Kentuckiana Regional Planning andDevelopment Agency. (2000). Horizon 2030.Kentucky Transportation Center. (2004).Research Results 1(2), pp.3.Land Trust Alliance. (2006). Conservationoptions for owners.Southern <strong>Indiana</strong> Chamber of Commerce.(2003). <strong>Indiana</strong> 2020: Creating Our Future.U.S. Census Bureau. (1990). Census ofPopulation and Housing; SF3 files.U.S. Census Bureau. (2000). Census ofPopulation and Housing; SF3 files.

CONSERVATION DESIGN

Conservation Design 23Rural Conservation andPreservationPreserving the rural landscape of acommunity is an enormously difficultchallenge for planners. Managing growthpatterns in a consistent manner thatcombines methods of preservation withsocial and economic factors is extremelycomplex. In order to determine the mostdesirable elements of a community‘s ruralcharacteristics, unique planning techniquesare required.The primary planning tools most often usedby planners for the preservation of the ruralcharacteristics of a community include, thecomprehensive plan, the land developmentordinance, and the development planreview process. Utilizing these tools inconjunction with additional innovativecommunity planning techniques provideplanners with the ability to manage growthand development and to provide the mostefficient means of preservation for the ruraland scenic resources of a community(Stokes, Watson, and Mastran, 1997).Some of the more common planningtechniques currently used to protect andpreserve rural resources include,conservation subdivisions, clusterdevelopment, overlay zoning, and thetransfer and/or purchase of developmentrights. These tools are becomingincreasingly more popular as ruralpreservation methods and land usedevelopment programs generate positiveoutcomes in communities across thecountry and around the globe.The comprehensive land use plan is theblueprint for future development in acommunity, and provides a visionary planof action detailing what should be doneand how and when to do it. The land useplan serves as the foundation for thepreservation of a community’s natural,cultural, historical, and scenic resourceswhile respecting the importance of itsresidential, commercial, and industrialbased economic resources.Clustering developmentClustering development may consist ofsingle-family detached housing, multifamilyapartment buildings orcondominiums, or a combination of alltypes. Maintenance of the common areascreated by cluster development is typicallycontrolled by a homeowners association,which requires homeowners to contributeequally to the related expense. Thecommon areas may be used asrecreational or agricultural space and aregenerally separated from the residentialareas by a landscape buffer area. (Stokes,1997).Overlay zoningOverlay zoning, also known as critical areazoning, serve to protect ecologicallysignificant lands and to function as ameans of preserving. In addition, serve as

Conservation Design 24safeguards for the unique visual resourcesthat are considered to be in danger ofobjectionable development policies.(Scenic Corridors Design Guidelines,2001.)Overlay zoning districts work to enhanceareas of aesthetic value such as,waterways, shorelines, wetlands,woodlands, historic preservation districtsand natural historic sites. Overlay zoningassure that these unique sites areexcluded from incompatible land uses.Development standards in overlay zoningdistricts require architectural elements tobe of a specific design, color, and material;enhancing the view shed and thearchitectural scheme of the district. Thephysical and structural elements of thedevelopment are organized in a manner tolimit infringement upon scenic value andnatural setting of the existing landforms.Landscaping plans incorporate existingtrees, shrubs, watercourses, and wetlandswhere feasible and new vegetation consistof native plant species and other flora thatis compatible with the surroundingenvironment.Conservation SubdivisionsDevelopmentsConservation Subdivisions Developments(CSD) are an alternative to traditional“cookie-cutter” style subdivisions. Theseconservation subdivisions are a marketorientedapproach to balancing marketdemand and environmental protectionissues.Conservation subdivisions developmentsconcentrate development on those areasmost suitable for development, such asupland areas or areas with well-drainedsoils. The undeveloped portion of aconservation subdivision can include suchecologically or culturally-rich areas aswetlands, forest land, agriculturalland/buildings, historical or archeologicalresources, riparian zones (vegetatedwaterway buffers), wildlife habitat, andscenic view sheds (Stokes, 1997).Reflection of Residential Development nearWetlands in Prairie Crossing.Common features of conservationdevelopments include the integration ofcompact land tracts and common openspaces. In addition, they permit theconstruction of the maximum number ofresidential housing units allowed under

Conservation Design 25community zoning regulations. The finalproduct is a contemporary suburban stylehousing development with tranquillandscape features such as, wetlands,woodlands, and scenic vistas.Typically, the open space is permanentlypreserved via easement or dedication andmanaged through a homeownersassociation, land trust (or otherconservation organization), or localgovernment agency. In some conservationsubdivisions, preserved areas have beenleased to farmers for small-scaleagricultural production, used for communitygardens, and even used as communityownedhorse farms.Conservation subdivision developmentscan be a useful tool in addressing localconcerns regarding the loss ofenvironmental resources, farmland andcommunity character. Local governmentscan also use CSD’s as a vehicle forcreating community open-space networks.Establishing open-space networks andreducing impervious surface cover canbenefit the community by providing newrecreation opportunities, protecting wildlifehabitat, maintaining the ecological andwater filtration functions of wetlands andriparian areas, and reducing storm waterrunoff and flooding (Arnold, Gibbons, &Monahan 1999).To encourage the use of CSD, localgovernments need to modify theircomprehensive plans, zoning ordinances,and subdivision regulations to allowconservation subdivisions and toincorporate the flexibility into keydevelopment codes - such as lot sizes,building setbacks, and road frontages andstandards - needed to implement CSD.Providing incentives such as densitybonuses to developers that incorporateCSD into their projects is further step thatlocal governments can take to promote thistype of high-quality, ecologically sensitivetype of development (Town of Cary 2004).Conservation compared Traditional RuralResidential DevelopmentsThe Comprehensive Plan for <strong>Floyd</strong> <strong>County</strong>includes similar elements for thepreservation of scenic lands under its LandUse Plan Goals and Community Policiessection. This section focuses onpreserving the rural atmosphere of thearea, which describes ten Smart Growthprinciples for land use preservation(Cornerstone 2005, 16).

Conservation Design 26Conservation SubdivisionAttributesDesignated open space should be locatedto protect environmentally sensitivefeatures. In most cases, it can also providenearby residents benefits such as scenicvistas and recreation areas which addvalue and increase marketability.The location and functions of neighborhoodconservation areas should be the first thingthe developer designs, not the last. If theproperty is blessed with a good fishingstream or notable wildlife habitat, theconservation areas should be configured toprotect these resources.perspective and possibly linked to formgreenways.Social and RecreationalAdvantages• Common open space provides attractiveareas for neighbors to meet informallyand socialize.• Common open space may be designatedfor recreational uses such as biking,walking or ball playing all of whichpromote social interaction.• Smaller yards to tend can provideresidents with more leisure time.Environmental Advantages:For Water Quality• Common open space can be designatedas buffers to protect wetlands, streamsand ponds.• Water quality is enhanced whenimpervious surfaces such as streets,driveways and pipes are minimized.• Where appropriate, stormwater andsewage treatment facilities can belocated within the open space.While recreational use of the open area isoften appropriate, locating a ball field onthe banks of a trout stream, where soil andfertilizer might wash to the water, shouldbe avoided. Ultimately, to retain ruralcharacter and protect habitat, conservationareas need to viewed in a regionalIdeal Rural Open SpaceCreated Nature Preserves

Conservation Design 27For Wildlife• Common open space, if properly sitedand managed can provide wildlife habitatwith the three basic requirements ofshelter, food and water.• When linked to other existing open areas,the common open spaces can serve aswildlife corridors and unfragmentedwildlife preserves.• Common open space can be used toprotect “unique or fragile” habitat asidentified by local, regional or statenatural resource surveys.The majority of residents in bothconventional and conservationsubdivisions said that a "nature view fromhome" of wooded areas was their toppriority in a home site, but the view of thewoods was largely unavailable in theconventional developments (Bailey 2004).Conservation subdivision design offerseconomic benefits to residents,developers, local governments and thecommunity.Economic Advantages ofConservation SubdivisionDevelopments1. Lower costs compared totraditional/conventional subdivisiondevelopment, while accommodating thesame number of homes2. More profitable and faster sellingdevelopment in many cases3. Faster home appreciation4. Helps to preserve the tourism economyby preserving land, wildlife and ruralcharacter5. Smoother permit review process6. Protects water quality, reducing oreliminating the need for expensivestormwater pollution treatment7. Reduced infrastructure constructioncosts8. Reduced infrastructure maintenancecosts9. Reduced demand for publicly fundedland and open space10. Enhances the property values ofnearby parcels and neighboring properties11. Marketing and sales advantage asdevelopers and realtors can highlightdistinct benefits such as open space,views, wildlife and trails (Landchoices,2006).

Conservation Design 28Four Successful Steps toImplementing ConservationSubdivision Design:Step One: Identifying ConservationAreas:Identification of green space worthy ofpreservation is divided into two parts:Primary Conservation Areas comprisingregulatory wetlands, floodplains and steepslopes; and Secondary ConservationAreas including those unprotectedelements of the natural and culturallandscape that deserve to be spared fromclearing, grading and advancement.Step Two: Locating House Sites:Locating the approximate sites of individualhouses which for marketing and quality-oflifereasons should be placed at arespectful proximity to the conservationareas, with homes backing up towoodlands for privacy, fronting onto acentral common or wildflower meadow, orStep 1 to Identifying Conservation Areasenjoying long views across open fields orboggy areas. Take maximum advantageof the property’s conservation elements,thereby capturing the added value thoseelements convey.Step Three: Aligning Streets and Trails:Trace a logical alignment for local streetsto access the homes and for informalfootpaths to connect various parts of theneighborhood making it easier forresidents to enjoy walking through thegreen space, observing seasonal changesin the landscape and possibly meetingother folks who live at the other end of thesubdivision.Step Four: Drawing in the Lot LinesDraw in the lot lines. Successfuldevelopers of conservation subdivisionsknow that most buyers prefer homes inattractive park-like settings and that viewsof protected green space enable them tosell lots or homes faster and at premiumprices (Arendt 2001).Final Layout of a Conservation DevelopmentImage of Rural Development

Conservation Design 29Land Use Policies and Methodsfor Land ConservationLand conservation contributes to ruralcharacter by preserving the undevelopedlands and preventing them from becomingsubdivisions. Land conservation allowslocal governments to preserve existingecosystems and environmentally sensitiveareas while managing growth.Effectively management of growth requirescurrent citizen to take proactive actions. Asthe Highlander Point continues to grow,local leaders and citizen need to enact landuse policies to manage this future growth.Approaches to LandConservationThere are manychoices policies for thecitizens of Highlander Point to implementfor conserving land, with each havingvarying levels of government involvement.It is up to the community to decide whichmethods are most appropriate for the area.View of Conventional Development. FromRural by DesignLand TrustsThe least government-intrusive method forland conservation is the establishment ofland trusts. Land trusts are non-profit,private organizations that may purchase oraccept donations of land to hold inperpetuity on the promise that the land willbe developed very lightly, or not at all.Land trusts may hold land in ownerships ormonitor conservation easements. TheSycamore Land Trust and the OakHeritage Conservancy are excellentexamples of land trusts found in <strong>Indiana</strong>.Conservation EasementsAccording to <strong>Indiana</strong> law, a conservationeasement is "a nonpossessory interest of aholder in real property that imposeslimitations or affirmative obligations withthe purpose of (1) retaining or protectingnatural, scenic, or open space values ofreal property; (2) assuring availability of thereal property for agricultural, forest,recreational, or open space use; (3)protecting natural resources; (4)maintaining or enhancing air or waterquality; or (5) preserving the historical,architectural, archeological, or culturalaspects of real property." (<strong>Indiana</strong> Code32-23-5-2)

Conservation Design 30In plain language, a conservationeasement "is a restriction placed on apiece of property to protect its associatedresources." (The Nature Conservancy)The easement is a legal document thatlimits or prevents development on the land,and is permanent because the easementruns with the property.Conservation easements have taximplications, because the value of land thatcannot be developed does decrease.<strong>Indiana</strong> law mandates that property with aconservations easement must be assessedand taxed reflecting the land's decrease invalue. Therefore, if a conservationeasement is donated, the donor mayqualify for a charitable deduction.Conservation easements do not require theinvolvement of local government; the saleand purchase of easements is like any realestate transfer; it is a private act between aland owner and a purchaser.Open Space Development DesignMandatesA third option for citizens who wish topreserve and conserve land involves ahigher degree of local governmentinvolvement. Randall Arendt suggestsmandating open space subdivision designin zoning ordinances, specifically insubdivision regulations. He describesspecific open space development designpolicies in “Growing Greener”. For furtherinformation on specific ordinance languageplease visit the Green Neighborhoods'website.2006)(www.greenneighborhoods.org,Greenways Neighborhood, near Lexington,VirginiaDevelopment RightsThe transfer of, or purchase of,development rights are a planningtechnique that is currently used to protectand preserve natural and rural resourcesand to manage development in areasdeemed to have a high aesthetic value.They are similar to conservationeasements.A transfer or purchase of developmentrights program involves government to alarge degree. A development rightsprogram necessitates a strong political willto either spend a great amount of publicmoney to acquire the development rightsor strong zoning language that provides fortransfer of the development rights from arural area to a location where growth is farmore desirable.The local government typically runs apurchase of development rights (PDR)program. With the PDR’s landowners, salepurchases the development rights but

Conservation Design 31continue to own the land. Becausedevelopment rights can be very valuable, itproves to be fiscally challenging to operatea PDR. In the region, the Lexington-Fayette Urban <strong>County</strong> Government(Kentucky) has a PDR program in place topreserve farmland (www.lfucg.com, 2006).approach. From a governmental approach,the open space development designmandates would be most useful foraccomplishing the residents desire tomaintain the rural character.Far more common in the United States aretransfer of development rights (TDR)programs. TDR programs areadministered by the local government asan growth management tool. Thedevelopment rights of an area can betransferred from a designated "sendingzone" to a designated "receiving zone".The intention is to encourage developmentin areas for more efficient use of existinginfrastructure (Scenic Corridors DesignGuidelines, 2001).Both land trusts and conservationeasements, which can be administered byprivate groups or individuals, could be ahighly affective land conservation

Conservation Design 32Examples of SuccessfulConservation ResidentialNeighborhoods:Example 1: Third Street Cottage inLangley, WashingtonThe city of Langley adopted the CottageHousing Development (CHD) code in1995. This code recognized that homes of975 Square Feet (SF) should not betreated the same as homes of two to threethousand sq. feet.The development is composed of sevenclusters, each organized around theexisting natural farmland, ponds, andoriginal farm buildings.The CHD code allows for 4-12 homes in anarea that usually less than half of thatmany homes could be built. Each cottagehas to be adjacent to a common area. Thedevelopment has minimal parkingrequirements (1.25 spaces per cottage)and requires that parking spaces bescreened from the road.Example 2:Tryon Farm in La Porte <strong>County</strong><strong>Indiana</strong>Picture of Third Street CottageTryon Farm is a 170-acre development,located just one hour outside of Chicago.The development is intent on preservingthe existing farmland and ruralcharacteristics found in this community.Aerial Photograph of Tryon-Farm

Conservation Design 33Example 3:Prairie Crossing in Grayslake,IllinoisPrairie Crossing is a conservationcommunity made up of 359 homes and 36condominiums. The development providesresidents with plenty of opportunity to enjoythe outdoors with public gardens, forest,open public spaces and more than tenmiles of trails. The preserved open spacefound within the development composesover half of the acreage (A ConversationCommunity: Living At Prairie Crossing,2001).ReferencesAbout conservation easements. RetrievedApril 06, 2006, fromhttp://www.natlands.org/categories/article.asp?fldArticleId=85American farmland trust: State programs –<strong>Indiana</strong>. Retrieved April 07, 2006, fromhttp://www.farmland.org/programs/states/<strong>Indiana</strong>.aspArendt, Randall. (2001). EnhancingSubdivision Value Through ConservationDesign. www.Realtor.org Summer 2001.Arendt, R. (1999). Growing greener:Putting conservation into local plans andordinances. Washington, DC: IslandPress.Arendt, R. (1994). Rural by design.Chicago: Planners Press.Arendt, R. (2004). Linked landscapes:Creating greenway corridors throughconservation subdivision design strategiesin the northeastern and central UnitedStates. Landscape and Urban Planning,68(2-3), 241-269.Arnold, Chester; Gibbons, Jim & Monahan,Rosemary. (1999). ConservationSubdivisions. NEMO Fact Sheet 9.University of Connecticut.Bailey, Laura. (2004). New market fordevelopers: homebuyers want view ofwoods, not large lawns. University ofMichigan. Retrieved April 2, 2006 fromhttp://www.umich.edu/news/index.html?Releases/2004/Jun04/r062904aComprehensive Plan. (2005).Cornerstone 2005: A Vision for the future.<strong>Floyd</strong> <strong>County</strong> Comprehensive Land UsePlan Update.Retrieved January 25, 2006 fromhttp://www.<strong>Floyd</strong>county.in.gov/building_commissioner.aspCommon conservation techniques.Retrieved April 06, 2006, fromhttp://www.natlands.org/categories/article.asp?fldArticleId=83Green Print Program: Preserving OurGreen Infrastructure.Retrieved April 5, 2006 fromwww.dnr.state.md.us/greenwaysGreenWay neighborhood.Retrieved April 06, 2006, fromhttp://www.greenwaynews.com/Drawing of Prairie Crossing

Conservation Design 34Land Trust Alliance.Retrieved March 28, 2006, fromhttp://www.lta.org/Landchoices. (2006) Retrieved April 6,2006 from.www.landchoices.orgMaryland Department of NaturalResources. (2000). Maryland’sPrairie Crossing. A ConversationCommunity: Living At Prairie Crossing.(2001)Retrieved April 5, 2006 fromwww.prairiecrossing.com/pc/site/aboutus.htmlOpen space residential design inMassachusetts. Retrieved April 06, 2006,from http://www.greenneighborhoods.orgScenic Corridors Design Guidelines:Design, Engineering & PlanningGuidelines. (2001).Retrieved April 5, 2006 fromhttp://www.scottsdaleaz.gov/design/CorridorPlans/ScenicSmart development for qualitycommunities, Volume 2: A designguidebook for towns and villages inCattaraugus <strong>County</strong>, New York. Preparedfor Cattaraugus <strong>County</strong> by Randall Arendt.Retrieved April 06, 2006, fromhttp://www.cattco.org/planning/planning_info.asp?Parent=12302Stokes, S.N., A.E. Watson, and S.S. Mastran.(1997). Saving America’s countryside: aguide to rural conservation. Johns HopkinsPress, Baltimore, MD.The Cottage Company.comRetrieved April 2, 2006 from(www.cottagecompany.com)Town of Cary. (2004). Open Space andHistoric Resources Plan. ConservationSubdivision Design.Tryon Farm. (2006). A UniqueConservation Community.Retrieved April 2, 2006 fromhttp://www.tryonfarm.com/design.htmlTryon Homes.comRetrieved April 3, 2006 from www.tryonhomes.comTyler Settlement Rural Historic District.Comprehensive Management Plan.(1988). Louisville.Retrieved April 2, 2006 fromwww.jefferson.k12.ky.us/departments/environmentaled/history/histsettling.htmlUniform conservation easement act. I.C.32-23-5. Retrieved March 31, 2006, fromhttp://www.in.gov/legislative/ic/code/title32/ar23/ch5.htmlWhat are conservation easements?Retrieved April 06, 2006, fromhttp://www.nature.org/aboutus/howwework/conservationmethods/privatelands/conservationeasements/about/art14925.html

WASTE TREATMENT

Waste Treatment 36IntroductionThe issue of sewers has been one of greatdebate and concern in the HighlanderPoint community. This is evident thoughpublic comments made at the publicmeeting on February 28, 2006 andcomments from the planning commissionboard members meeting February 10,2006.In order to go forward with any decisionsconcerning waste treatment, it is necessaryto understand the decisions that are beingmade now that will effect future decisions.Georgetown City Council voted on April 3,2006 to purchase 23 acres of property toconstruct a sewage treatment plant. Thefacility will provide sewage service toresidents in and around Georgetown andthus remove its dependence on NewAlbany (Hershberg, 2006)In addition to Georgetown plans forbuilding its own treatment facility, NewAlbany received 350,000 “sewer credits”from the United States EnvironmentalProtection Agency (EPA) to begin addingnew users to its sewer system. A sewercredit is equivalent to one gallon ofwastewater per day. According to the EPA,an average household produces around300 gallons per day. This means that NewAlbany can add just fewer than 1200 newusers once the entirety of the creditsbecomes available. As New Albany makesimprovements to its sewer system, twoadditional installments of credits of 340,000and 334,000 respectively will be issued.This creates a total of over 2,000 additionalnew users (Adams, 2006).For the Highlander Point Gateway, thiscould mean many things. The gatewaycurrently gets its sewer service from NewAlbany. Because New Albany has beenstruggling with the EPA to gain credits thatwould allow more people onto the sewerline, the addition of new sewers has beenlimited. Once the Georgetown facilitycomes online there is the potential foradditional sewage service to becomeavailable for New Albany and thesurrounding areas. This could allow theHighlander Point Gateway to expand itssewer serviceTraditional centralized systems may not bebest suited for Highland Point. There aremultitudes of alternative treatmenttechnologies available to smallcommunities. When deciding upon asuitable alternative community leadersmust weigh their choices carefully sinceeach technology has advantages andlimitations. To choose the right treatmenttechnology, a community must evaluatemany factors and explore each system indepth.Some factors to consider whenevaluating alternative wastewatertreatment systems are the state and localregulatory requirements, current and futurecommunity population trends, the currentenvironmental limiting conditions in the

Waste Treatment 37community and the community’s’ limitingfinical factors (Olson, 2002).According to the <strong>Indiana</strong> State Departmentof Health rules for Residential Sewagedisposal Systems sec 31 (g) & (h):(g)”In order to permit development of newor more efficient sewage treatment ordisposal processes, the commissionermay approve the installation ofexperimental equipment, facilities, orpollution control devices for whichextensive experience or records of usehave not been developed in <strong>Indiana</strong>. Theapplicant for such approval must submitevidence of sufficient clarity andconclusiveness to convince thecommissioner that the proposal has areasonable and substantial probability ofsatisfactory operation without failure.”(h)“No portion of the residential sewagedisposal system or its associated drainagesystem shall be constructed upon propertyother than that from which the sewageoriginates unless easements, which grantpermission for such construction andaccess for system maintenance, havebeen obtained for that property and havebeen legally approved and recorded bythe proper authority or commission.”Citing these two regulations, HighlanderPoint can manage new developments anddirect its design standards toward utilizingopen space more efficiently, whilepreserving the rural feel of the community.This allows Highlander Point to be creativein its design and choice for sewagetreatment services.At the county level the <strong>Floyd</strong>s <strong>County</strong>Cornerstone 2005 Comprehensive Planstates that future development will worktowards following smart growth principles,namely managing future development to“Take Advantage of Compact BuildingDesign.” State regulations can aid inachieving this goal. By utilizingnontraditional but proven effectivedecentralized sewer systems, along withclustering of new developments on suitableland, the community can manage growthwhile preserving environmentally sensitiveareas and maintaining its rural character.Currently the Highlander Point communityis a mix of agricultural (AR), commercial(C) rural (RR) and suburban residential(RS) developments. The community willmove towards denser developments in thefuture as <strong>County</strong> officials have designatedthis area as a managed growth area for thecounty (Cornerstone, 2005).Currently sections of the community havewater and sewage services provided by theNew Albany treatment facility. Theneighboring community of Georgetownplans to begin constructing a new 350,000-gallon treatment facility this summer, whichwill end the Georgetown’s dependence onNew Albany for its sewage treatmentneeds (Hershberg, 2006). The role of thenew Georgetown treatment facility in the

Waste Treatment 38development in Highlander Point is ofconcern and warrants further investigation.Two limiting environmental conditionswithin the Highlander Point area limittraditional types of wastewater treatmentfacilities, centralized and onsite septicsystems. These two environmentalconditions are steep slopes (Map 3) andthe poor soil conditions (Map 4) foundthroughout the community.installing a conventional centralized systemthroughout Highlander Point communityvery cost prohibitive.Traditionally, rural and outlying suburbanareas developments depend uponindividual septic systems for wastewaterdisposal (Hoover, 1997). Problems canarise in certain areas because not all soilscan absorb wastewater or purify it.Improperly functioning septic systemscontaminant surface and groundwater, andcan lead to outbreaks of bacterial and viralillnesses (Hoover, 2001).Conventional central sewer systems aredependent upon gravity to deliver thesewage from each property to thetreatment plant. The pipes mustcontinuously slope downwards at a steepgradient that is uniform throughout thesystem to ensure that the pipes avoidclogging with solid material. The elevationdifferences within found in HighlanderPoint would require a centralized system toemploy numerous lift stations to transportthe sewage to the higher elevation (Olson,1996). These requirements would makeMap3: Slope Limitation Overview for Highlander Point

Waste Treatment 39Within the study area, the soils have a verylimited capacity for septic tank absorptionfields (Map 4 and Table 1). The ratings arebased upon the soil properties that affectabsorption of the effluent, construction andmaintenance of the system, and publichealth. "Somewhat limited" indicates thatthe soil has features that are moderatelyfavorable for the specified use. Ownerscan expect fair performance and moderatemaintenance from the system. "Verylimited" indicates that the soil has one ormore features that are unfavorable forseptic systems. Owners can expect poorperformance and maintenance can beexpected (www.nrcs.usda.gov).Decentralized systemsThere has been much concern voiced inthe public meeting, the planning boardmembers meeting and in the “Southern<strong>Indiana</strong> 2020: Creating Our Future” survey,over health concerns and about the poormanagement of the current decentralizedtreatment facilities found in the area.It has been only in the last few years thatthe EPA acknowledged that decentralizedsystems are as successful as municipal orcentralized systems in treating wastewaterto meet water quality standards in a costeffectivemanner (Anderson and Gustafson1998). In 1997, the EPA concluded that“Adequately managed decentralizedRatingTotal Acresin <strong>Floyd</strong><strong>County</strong>Percent of<strong>Floyd</strong> <strong>County</strong>Very limited 77,838.00 81.3Not rated 17,649.60 18.4Somewhatlimited235.2 0.2Table 1: Soils Septic TankAbsorption Fields ratings for <strong>Floyd</strong>s <strong>County</strong>Map4: Septic Tank Soil Absorption Limitation For Highlander Point

Waste Treatment 40wastewater treatment systems can be acost effective and a long-term option formeeting public health and water qualitygoals, particularly for small, suburban andrural areas." (EPA, 1997)The EPA defines decentralized wastewatertreatment systems as “Individual onsite orclustered wastewater systems (commonlyreferred to as septic systems, privatesewage systems, individual sewagetreatment systems, onsite sewage disposalsystems, or “package” plants) used tocollect, treat, and disperse or reclaimwastewater from individual dwellings,businesses, or small communities andservice areas. Such systems may providean alternative to conventional centralizedwastewater systems” (EPA, 2002).With the limiting environmental conditionsfound in Highlander Point, the installationand proper maintenance of decentralizedsystems are the best options of futuredevelopments. Rural communities thathave limiting environmental conditions andlimited financial capabilities to supportmulti-million dollar sewer projects canutilize decentralized systems as analternative to the expensive, centralizedsewer systems (Hoover, 2001).Decentralized systems require more thanthe usual amount of long-term monitoringnecessary to ensure that these systemsconsistently meet the operating standardsclaimed by manufacturers and proponents(Anderson and Gustafson 1998). To meetthese requirements these systems need tobe operated by a competent, accountablemunicipal, and/or private entity. Properoperation and management of treatmentsystems help dramatically improve thelongevity and performance of any system(Hoover, 2001).To adequately manage decentralizedsystems, many communities have taken aproactive approach by formingdecentralized wastewater managementprograms. These programs oversee themonitoring and maintenance of theseprivately treatment facilities afterconstruction (Anderson and Gustafson,1998).Decentralized ManagementA decentralized management programmust address not only the properfunctioning of these systems, but alsosystem permitting, legal considerations, themaintenance of multiple types of treatmentand collection systems, and setting userfees that fairly reflect different individualcircumstances and system types as well asusage. Developing a system to inventory,permit, manage and maintain septicsystems requires significant staff time andin many cases training (Hoover, 2001).The process of developing a publiclysupported, financially feasibledecentralized management programgenerally involves five steps:

Waste Treatment 41• Needs Assessment• Resource and Land Use Plans• Engineering Assessment• Public Education and Outreach• Management Plan and FinancialStructure DevelopmentDecentralized wastewater management isgrowth neutral. The decentralizedmanagement planning process allowscommunities to select the combination ofwastewater treatment methods that bestserves their land use goals, environmentalresources, and political constraints, ratherthan relying on one-size-fits-all solutions(Hoover, 2001).Linking wastewater management planningto local zoning ordinances, comprehensiveplans, and permitting processes, providecommunities with the opportunity to makewastewater treatment technology servecommunity goals and objectives (Hoover,2001).Future ConsiderationsWhile <strong>Floyd</strong> <strong>County</strong> elected and appointedofficials seek a decision about thewastewater treatment of this area, it will beimportant for them to keep in tune withresident and developers alike. This issuewill continue to be a hot button issue forthe community. To make informeddecisions about sewage treatment options,the <strong>Floyd</strong> <strong>County</strong> government should keepabreast of all of their options, from sewers,to septic, to decentralized systems.The Highlander Point Gateway has beendesignated as an area for growth. Sewagetreatment is a large part of this. Astreatment facilities and systems becomeavailable, more development will be able tooccur. With this expansion, however,growth need not become rampant. Many ofthe area residents have voiced theirconcerns that additional sewers would helppromote sprawl and unchecked growth.However, if <strong>Floyd</strong> <strong>County</strong> institutes stronggrowth regulations, this growth can bemanaged to keep pace with demand andcapacity.<strong>Floyd</strong> <strong>County</strong> is not alone in its decisions tomove from septic to sewers. Locationsaround the country have been dealing withthat issue for many years. A few examplesof other areas from around the country thathave dealt with the transition from septic tosewer can be found in the appendix. Thesearticles show how these communities havedealt with the issue and provide someinsight on how <strong>Floyd</strong> <strong>County</strong> might proceedwith their own treatment decisions.

Waste Treatment 42ReferencesAdams, H J. (2006, March 4). New Albanysewer growth ok’d. The Louisville Courier-Journal: <strong>Indiana</strong>. March 4, 2006.Agnoli, T., 2000. Summary of the Status ofOnsite Wastewater Treatment Systems inthe U.S. during 1998. 2000Arendt, R., E. A. Brabec, H. L. Dodson, C.Reid, and R. D. Yaro. (1994) Rural byDesign: Maintaining Small TownCharacter. American Planning Association.Chicago, IL.Comprehensive Plan. (2005). Cornerstone2005: A Vision for the future. <strong>Floyd</strong>s<strong>County</strong> Comprehensive Land Use PlanUpdate. Retrieved April 6, 2006 fromhttp://www.<strong>Floyd</strong>scounty.in.gov/building_commissioner.aspHershberg, Ben Zion. (2006 April, 5) Plansfor sewage plant proceed. LouisvilleCourier-Journal: <strong>Indiana</strong>. April 5, 2006.Hoover, Juli Beth. (2001) DecentralizedWastewater Management:Linking Land Use, Planning &Environmental Protection. Presented at the2001 APA National Conference.Retrieved April 6, 2006 fromhttp://www.asu.edu/caed/proceedings01/HOOVER/hoover.htmHoover, M.T. (1997) Soil Facts: Investigatebefore purchasing. North CarolinaCooperative Extension Service.Retrieved April 5, 2006 fromhttp://www.soil.ncsu.edu/publications/Soilfacts/AG-439-12/Gates, Patrick T. & Gates, Todd (2004,February 04) Cluster Sewer Systems OfferAlternative. Land Development Today.Retrieved April 6, 2006, fromhttp://www.landdevelopmenttoday.com/index.php?name=News&file=article&sid=58<strong>Indiana</strong> State Department of Health.(1990). Residential Sewage DisposalSystems. <strong>Indiana</strong>polis, IN.Retrieved April 6, 2006 fromhttp://www.nesc.wvu.edu/nsfc/Regulations/IN.pdfJoubert, L., P. Flinker, G. Loomis, D. Dow,A. Gold, D. Brennan, and J. Jobin. (2004)Creative Community Design andWastewater Management. Project No. WU-HT-00-30. Prepared for the NationalDecentralized Water Resources CapacityDevelopment Project, WashingtonUniversity, St. Louis, MO, by University ofRhode Island Cooperative Extension,Kingston, RI.Olsen, K., B. Chard, D. Malchow, D.Hickman. (2002) Small CommunityWastewater Solutions:A Guide to Making Treatment,Management, and Financing Decisions.University of MinnesotaExtension Service. St. Paul, MN.University of Minnesota Extension Service.(1998) Alternative Wastewater TreatmentSystems.Residential Cluster DevelopmentFact Sheet Series. University of Minnesota.St. Paul, MN.US Environmental Protection Agency(EPA). (1997) Response to Congress onUse of Decentralized WastewaterTreatment Systems. EPA 832-R97-001b.Office of Water. Washington, DC.US Environmental Protection Agency(EPA). 2003. Voluntary National Guidelinesfor Management of Onsite and Clustered(Decentralized) Wastewater TreatmentSystems. EPA 832-B-03-001. Office ofWater. Washington, DC.

Waste Treatment 43References (Continued)Berg, R. (2004). When Science CrossesPolitics, II: Getting Down to Earth in theGreat Wastewater Disputes. Journal ofEnvironmental Health, 67(1), 40-50.Fuess, J.V. and R.P. Farrell (1996). Asmall community success story: Howpressure sewers and a community septicsystem are protecting the environment atCuyler, New York. Journal ofEnvironmental Health, 58(10), 18-22.Lake Havasu City begins switch fromseptic systems to sewers (1991).Engineering News-Record, 247(23), 17.Nelson, R. H. (1993). Unholy alliance.Forbes, 152(12), 141.

GREENWAYS, TRAILS, & PARKS

Greenways, Trails, & Parks 45GreenwaysGreenways are networks of land containinglinear elements that are planned, designed,and managed for multiple purposesincluding ecological, recreational, cultural,aesthetic, or other purposes compatiblewith sustainable land use. (Ahern, 1995)Greenways have a long history in theUnited States. Beginning with FrederickLaw Olmsted’s Emerald Necklace inBoston (1875-1895), cities, counties, andregions throughout the nation haveplanned and implemented greenways, trailsystems, and the linkage of regional parksthrough natural corridors (Ryder, 1995).In the late 1980’s a renewed interest ingreenway development was sparked by areport by the President’s Commission onthe American Outdoors. The Commissionpromotes a living network of greenways toprovide people with access to open spacesclose to where they live, and to linktogether the rural and urban spaces in thelandscape, threading through cities andcountryside like a giant circulation system(President’s Commission on the AmericanOutdoors, 1987).Pedestrian trail at an <strong>Indiana</strong>polis Greenway.Photo Source: Indy Greenway FoundationGreenways and trail systems emphasizespatial connectivity of natural systems inthe landscape by linking larger park areasthrough “fingers” or a “necklace” of green.Greenways can be described landscapesstructured by a ‘patch and corridor’ spatialconcept which includes corridors andstepping stones to connect isolatedpatches of open space while counteringthe effects of ecosystem fragmentation(Forman and Godron, 1986).A Greenway system for <strong>Floyd</strong><strong>County</strong>People need green space, parks and trailsfor many uses, including recreation, dogwalking, physical exercise, and even as analternative means of transportation whenpedestrian or bicycle paths are available.The area surrounding US 150 atHighlander Point is an ideal location to setup and implement these services andamenities. This section examinesgreenway planning and the implementation

Greenways, Trails, & Parks 46of a system to link parks for <strong>Floyd</strong>s <strong>County</strong>.Special attention is given to the HighlanderPoint Gateway District as an area withpotential to serve as a hub for thebeginnings of a larger, countywide parkand trail system. Given the currentdevelopment patterns and the naturalsurrounding, the Highlander Point Gatewayprovides the opportunity to implementrecreational facilities including parks andplaying fields for all ages, whilecontributing to connectivity between theresidential areas of <strong>Floyd</strong>s’s Knobs.Greenway and trail networks aredeveloping in and around the cities of<strong>Indiana</strong>polis and Bloomington as well as incounties across the state. A goal of the<strong>Floyd</strong>s <strong>County</strong> Parks Master Plans is toreserve and acquire park space in the ruralfringe of the urban areas within <strong>Floyd</strong>s<strong>County</strong> in advance of expecteddevelopment with the purpose ofinfluencing future growth patterns, assuringfuture residents accessible open spacesand protecting significant natural features(New Albany-<strong>Floyd</strong>s <strong>County</strong>, 2003). Agreenway system could contributespecifically to this goal while supportingsmart growth in <strong>Floyd</strong>s <strong>County</strong> in terms ofboth influencing residential developmentand conserving ecosystems.Greenways efficiently use and preservewetlands, floodplains, and areas withsteeply graded topography. The steepslopes and floodplains of <strong>Floyd</strong>s’s Knobs inparticular are ecologically sensitive areasespecially worthy or protection. Theincorporation of greenway systems thatprotect stream corridors within agriculturallands can solve environmental problems aswell as satisfy demands for open spacepreservation, wildlife conservation, andwetland protection (Schrader, 1995).Parks and greenways can stimulate thelocal economy. Some argue that openspaces do not provide economic benefitsbecause they occupy developable land.The reality is that parks and trail systemsincrease property values. In terms of risingproperty values and increasing the taxbase, a study on greenways commissionedby the City of Bloomington, <strong>Indiana</strong> finds inmany cases that developers receive apremium on lot sales near greenwayssimilar to lot sales close to golf courses(City of Bloomington, 2000).Parks and trails can contribute to healthierlifestyles while strengthening social ties.Parks offer places for a community toexercise and play. Athletic fields, playgrounds and open spaces offer functionalareas that allow people to live moreactively in an outdoor environment. Parksand open spaces offer a meeting groundfor communities that provide for a greatersense of community.

IN-150Greenways, Trails, & Parks 47Planning for GreenwaysGoal determination is a critical element ofgreenway planning. The City ofBloomington <strong>Indiana</strong> set a wide range ofgoals for their area greenway system.These goals included the implementationof highly accessible bicycle and pedestrianpaths, the establishment of linkagesbetween existing parks, the formation offunding strategies, a commitment toenvironmental stewardship, and thepromotion of economic development andtourism (City of Bloomington, 2000). Usefulgoals for greenway planning in <strong>Floyd</strong>s<strong>County</strong> could include promoting furtheropportunities for recreation andconservation, establishing linkagesbetween existing parks and trails, andforming programs that educate thecommunity about the many benefits ofgreenway systems. Initial goals could focuson the identification of links betweenexisting parks, open spaces, andecologically sensitive areas. A complete listof <strong>Floyd</strong>s <strong>County</strong> regional and communityparks is available in the 2003 New Albany-<strong>Floyd</strong>s <strong>County</strong> Parks and RecreationMaster Plan (Appendix A). UsingGeographic Information Systems existingparks are easily compared with thefloodplain; a natural backbone for a4EGalena-Lamb ParkIN-150Garry E. Cavan ParkBUCK CREEK ROADOLD VINCENNES ROADValley View Golf Clubgreenway in <strong>Floyd</strong> <strong>County</strong>. MAP 1compares a proposed greenway made upof ecologically sensitive areas with existingarea parks.MAP 1 - Proposed <strong>Floyd</strong> <strong>County</strong> GreenwayPAOLI PIKEI-64ECORYDON PIKELetty Walter ParkI-64WCherry Valley Golf CourseI-265WSam Peden Community ParkBinford ParkAnderson Park0 12MilesExisting Parks and Open SpaceRoadsProposed Highlander Point GreenwayPotential Greenway Trail

Greenways, Trails, & Parks 48More long term initiatives might involveplans to link up with greenway or trailsystems in neighboring counties. Just northof <strong>Floyd</strong>s <strong>County</strong> is the Knobstone Trail inwestern Clark <strong>County</strong>. The Knobstone Trailis <strong>Indiana</strong>'s longest footpath - a 58-milebackcountry-hiking trail passing throughClark State Forest, Elk Creek PublicFishing Area, and Jackson-WashingtonState Forest that contains more than42,000 acres of rugged, forested land inClark, Scott and Washington counties insouthern <strong>Indiana</strong> (<strong>Indiana</strong> Department ofNatural Resources, 2006) (Map 2).Eventually trails could be developed within<strong>Floyd</strong>s <strong>County</strong> and the Highlander Pointarea to begin linking existing and newlyacquired park space. South of the actualHighlander Point commercial center thereis open land within the flood plain. Usingthis natural corridor it would be possible tolink the <strong>Floyd</strong>s <strong>County</strong> High school to theHighlander Point commercial center. Byconnecting the high school to thecommercial center auto accidents andlevels of traffic congestion might decrease.Such a trail could continue circumnavigatethe Mt. Saint Francis preserve andcontinue south along US 150 (Map 2).Existing transportation infrastructure canplay a role in linking trails and parks.Scenic roads, linear by nature, haveconsiderable potential for contributing togreenway corridors by protecting andconnecting landscapes of particularecological, recreational, and esthetic value(Little, 1990). Old Vincennes Road in the<strong>Floyd</strong>s’s Knobs area is situated roughlyalong a historic buffalo trace (SeeAppendix B).<strong>Indiana</strong>’s Historic Pathways passesthrough 16 counties and comprisesU.S. 50 from Vincennes toLawrenceburg and U.S. 150, whichoverlaps U.S. 50 from Vincennes andextends southeastward to the Falls ofthe Ohio. Portions of the old BuffaloTrace can be found on or south offederal highways connecting Vincennesand Clarksville (Historic Southern<strong>Indiana</strong>, 2006).As components of greenways, parkwaysand scenic routes have potential to providewildlife habitat protection, improvelandscape esthetics, enhance communitypride and identity, and optimize the use oflimited areas for conservation (Kent andElliott, 1995).MAP 2- Hiking Trails of Southern <strong>Indiana</strong>

Greenways, Trails, & Parks 49In terms of land use the <strong>Indiana</strong>polisGreenways Master Plan (2002) providesvaluable strategies for integratinggreenways with neighboring property. (1)Lower density residential developmentshould be developed carefully to provideboth sufficient access to the trail forresidents and appropriate vegetatedbuffers between homes and the trail. (2)Higher density residential developmentshould include a significant buffer areabetween the trail and parking lots orbuildings. (3) Areas of transitional spaceare recommended between greenwaysand commercial areas. (4) Uses includingchurches, schools, and libraries and otherpublic institutions should be linked toresidential areas. This linkage couldprovide a transportation options to countyresidents through pedestrian and bicycletrails (<strong>Indiana</strong>polis Greenways MasterPlan, 2002). Planning strategies that wouldbe of use for a greenway planning processin <strong>Floyd</strong>s <strong>County</strong> include:• Identify, plan and develop these areasat Highlander Point within <strong>Floyd</strong>s<strong>County</strong>• Come to a consensus betweencitizens, environmental groups &businesses.• Establish management strategies aswell as preservation and conservationrequirements• Work with landowners in recognizingpreservation sites, points of access,and rights of way.Making Greenways HappenGreenspace plans are usuallyimplemented either by imposingregulations or offering incentives to privateproperty owners to preserve these openspaces and protect natural habitats(Lindsey and Knaap, 1999). Enforcementof green space requirements may have anegative impact on long term greenwayplanning in communities. The <strong>Floyd</strong>s<strong>County</strong> Comprehensive Plan Updatesuggests an exploration of developmentimpact fees for a long-range parkacquisition program (2004). However,regulating could have adverse effects inregards to future development in the area.Offering incentives for landowners toparticipate in greenways initiatives couldbe the more effective course of action.Greenway incentives might includeconservation easements, transfer ofdevelopment rights, liability insuranceprograms, and other planning andeconomic applications (Ryder, 1995).Potential tax credits, etc. could be madeavailable to companies to donate acreagefor parks facilities on either abandonedsites or adjacent to their location so thatemployees as well as residents can benefitfrom the facilities (New Albany-<strong>Floyd</strong>s<strong>County</strong>, 2003).Residents throughout the United Statesplace a high value on greenwaydevelopment and in several instances havevoted to raise their own taxes in support ofgreenway implementation. In Cheyenne,