RIGHTS FOR WHOM? - Somo

RIGHTS FOR WHOM? - Somo

RIGHTS FOR WHOM? - Somo

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

European Coalition for Corporate Justice (ECCJ)<strong>RIGHTS</strong> <strong>FOR</strong> <strong>WHOM</strong>?Corporations, Communities and the Environment

<strong>RIGHTS</strong> <strong>FOR</strong> <strong>WHOM</strong>?Corporations, Communities and the Environment

AcknowledgementsWe are grateful to all the individuals who in some way or other contributed to this project and inparticular to Antony Loizou.

CONTENTIntroduction5Trapped in ChainsExploitative working conditions in European fashion retailers’ supply chain8The Powerful and The PowerlessUnión Fenosa’s electricity monopoly in Colombia11Failure to CommunicateSteel conglomerate ArcelorMittal in South Africa14Applying the ECCJ’s Proposals for Legislative Change16Conclusion204

INTRODUCTIONA growing body of work is documenting how theoperations of European companies outside theEuropean Union have been implicated in violations ofinternationally accepted human rights andenvironmental standards. The European Coalition forCorporate Justice (ECCJ) has highlighted many ofthese cases, including oil spills committed by Shell inNigeria, chemical poisoning suffered by workers inMotorola’s supply chain, and the forced relocations oflocal communities in Anglo-American’s South Africanoperations. 1 The causes of these and other violationsare complex, but it is clear that significant gaps in theway multinational operations are governed hasexacerbated this behaviour. As Professor JohnRuggie, the Special Representative of the UnitedNations Secretary-General on Business and HumanRights, has stated:“The root cause of the business andhuman rights predicament today lies inthe governance gaps created byglobalization - between the scope andimpact of economic forces and actors,and the capacity of societies to managetheir adverse consequences. Thesegovernance gaps provide the permissiveenvironment for wrongful acts bycompanies of all kinds without adequatesanctioning or reparation. How to narrowand ultimately bridge the gaps in relationto human rights is our fundamentalchallenge” 2The ECCJ believes there is an array of governancegaps that Europe has a unique opportunity to address.Through its power to implement legally bindingreforms, the European Union (EU) can not only leadthe debate internationally, but it is also in the positionto take effective steps to enhance compliance withinternationally agreed human rights and environmentalstandards, and to help those impacted by violations ofthose standards achieve greater access to justice.Current company law allows Multinational enterprises(MNEs) active in the EU with operations outside theEU to operate as a single economic and operationalunit, benefiting from the profits of their subsidiarycompanies and their commercial relationships withother businesses in those countries. Too often1 Ascoly, N. (2008) With Power Come Responsibility: Legislativeopportunities to improve corporate accountability at EU level,European Coalition for Corporate Justice, Brussels:www.corporatejustice.org/IMG/pdf/ECC_001-08.pdf2 Report by the Special Representative of the United NationalSecretary-General on the issue of human rights and transnationalcorporations and other business enterprises, Professor John Ruggie,to the United Nations General Assembly, Protect, Respect andRemedy: a Framework for Business and Human Rights, 7 April 2008,p.6: www.reports-and-materials.org/Ruggie-report-7-Apr-2008.pdfhowever, such benefits are enjoyed by the MNE whilethese operations and commercial relationships haveavoided liability for environmental and human rightsviolations, particularly in countries with a weakenedrule of law.This view has been reflected in the EuropeanParliament’s resolution, Corporate SocialResponsibility: A New Partnership, 3 which urged theEuropean Commission to provide further guidance tobusiness through regulation in key aspects ofcorporate accountability, and to greatly enhancecompliance by business with regard to internationalstandards of human rights and environmentalprotection.More recently, the European Commission (EC) hasaccepted that a more clear view of the current situationis needed and has commissioned a study to theEdinburgh University entitled “Study of the legalframework on Human Rights and the Environmentapplicable to European Enterprise Operating Outsidethe European Union”. The study was in fact one of therequests of ECCJ to the EC as a first step towardsidentifying what could be the role of the EU in order toeffectively implement the so called Ruggie framework,the 3-pillars framework “Protect, Respect, andRemedy: a framework for Business and HumanRights” presented by professor John Ruggie. 4In this report, professor Ruggie elaborates on threecore principles for a common framework for solvingmisalignments in the business and human rightsdomain: the State duty to protect against human rightsabuses by third parties; the corporate responsibility torespect human rights and the need for more effectiveremedies. The above-mentioned EC study has takenthe situation one step further in proposing some stepsthe EU could take in order to contribute to “Protect,Respect and Remedy”.During the last 3 years, the ECCJ has been constantlyinvolved in in-depth research involving input frominternational lawyers, academics and human rights andenvironmental advocates to evaluate the currentgovernance framework and obstacles to accessingjustice, and what the EU could do to improve thecurrent landscape. The conclusions from this research,published in Fair Law: Legal Proposals to ImproveCorporate Accountability for Environmental andHuman Rights Abuses 5 highlighted a range of legalreforms that could help minimise the negative impactof European companies operating outside the EU. It isimportant to highlight that the Edinburgh Universitystudy has arrived at very similar conclusions that ECCJ3 European Parliament, Committee on Employment and Social Affairs,Report on CSR: A New Partnership, (2006/2133(INI)),www.europarl.europa.eu/oeil/FindByProcnum.do?lang+en&procnum+INI/2006/21334 http://www.reports-and-materials.org/Ruggie-report-7-Apr-2008.pdf5 Gregor, F. and Ellis, E. (2008) Fair Law: Legal Proposals to ImproveCorporate Accountability for Environmental and Human RightsAbuses, European Coalition for Corporate Justice, Brussels:www.corporatejustice.org/IMG/pdf/ECCJ_FairLaw.pdf5

This report, Rights for Whom? reviews the potential impact of these legislativechanges through an exploration of three case studies:• Trapped in ChainsIndependent research highlights the working conditions in the factories of a major garment manufacturerfor European retailers such as C&A and Carrefour (India).• The Powerful and The PowerlessCCAJAR reports on claims of lost labour rights and the murder of union members working for UniónFenosa’s operations on Colombia’s Caribbean coast (Colombia).• Failure to CommunicateGroundWork reports how local communities near ArcelorMittal’s steel plant are suffering environmentaldamage and displacement (South Africa).These case studies add to the corporate accountability discourse, and provide further support for thereform of European law to improve compliance with human rights and environmental standards, and toallow those affected by violations of those standards greater access to justice.7

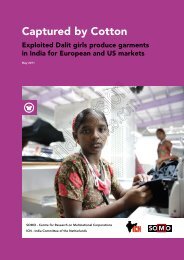

TRAPPED INCHAINSExploitative workingconditions in Europeanfashion retailers' supplychainMany of Europe’s largest clothing retailers buy hugequantities of garments manufactured in India. Theimmense buying power of these European companiesallows them to negotiate contractual terms that areextremely favourable, including very low wholesaleprices and very short production timeframes.While this is commercially beneficial for the retailer,these contractual terms effectively help to determinethe environment and labour conditions for the workerswho are making the clothes.Research by local NGOs in Tirupur, India has exposeddeplorable working conditions in Tirupur's textile andgarment factories that manufacture clothing for bigEuropean fashion companies. This case study willshow how the employment practices of some Indiancompanies in the European supply chain create poorsocial and economic conditions for Indian garmentworkers and their local communities.The Indian textiles and garment industryIndia plays an important role in the global textiles andgarment industry. It is the second largest producer oftextiles and garments and one of the few countries thatcovers the whole value chain - from the production ofcotton to the last stitches. 7After China, India, together with Bangladesh andVietnam, is a major exporter of finished garments tothe US and EU. In 2009 India exported garments worthUSD 5.68 (4.06 billion Euros) to the EU, accounting for55%of the country's total garment exports. 8The textiles and garment value chain is long andcomplex, with a high incidence of subcontracting.Along the supply chain, production units vary fromhuge factories employing thousands of workers tosmall, informal home units. The supply chain isfragmented, with thousands of production units, mostof them specialising in one phase of the value chain.Textiles and garments bring in high foreign currencyrevenue, playing a pivotal role in the Indian economy.In order to attract foreign investment the Indian7 AEPC (Apparel Export Promotion Council) website, " Fact Sheet" , nodate, < http://www.aepcindia.com/adv-Fact-Sheet.asp > (accessed on5 October 2010)8 AEPC (Apparel Export Promotion Council) website, "AEPC News:India-EU FTA to garner extra garment exports worth $3 billion ", nodate < http://www.aepcindia.com/news.asp?id=319&yr=2010 >(accessed on 4 October 2010)Photo: Alessandro Brasilegovernment attempts to create a business friendlyenvironment. It does so by offering businesses variousincentives. For instance, special economic zones havebeen set up where companies are offered variousfinancial incentives. At the same time, implementationand enforcement of labour laws are lagging behind.KPR Mill - Supplier of European FashionRetailersLocated in India’s most Southern state Tamil Nadu,KPR Mill Limited is a leading textile producer andgarment exporter. It is one of the few companies in theregion that has integrated the whole process, fromyarn manufacturing to clothing production. Thecompany has four production units and employs morethan 10,000 workers, of which about 90% is female.It's garment production unit operates under the nameof Quantum Knits. Quantum Knits is a wholly ownedsubsidiary of KPR Mill 9 and its production unit islocated at KPR Mill's Arasur complex.In the fiscal year 2010, the listed company made netprofits of USD11.25 million (€8,21 million). 10 In 2009,the company produced 9.029 metric tons of fabric and20,5 million pieces of clothing. 11 All the clothing thecompany produces is intended for export, mainly forthe European market, where 90% of its exports is sentto. 12 A number of well-known European buyers aresourcing or have sourced from this supplier, such as:H&M from Sweden, Decathlon, Kiabi and Carrefourfrom France, C&A from Belgium/ Germany and Gapfrom the US. 13Sumangali SchemeKPR Mill proudly states to have “one of the lowestemployee cost of the industry". "At 3.3 % of sales,against an industry average of 8.3 %”. 14 Contributing9 Four-S Services, "K.P.R. Mill Limited – Initiating coverage", Four-SServices, October 2009.10 Worldscope, KPR Mill Limited, 2010.11 Four-S Services, "K.P.R. Mill Limited – Initiating coverage", Four-SServices, October 2009.12 Ibid.13 KPR Mill website, "Clientele" (accessed on 7 October2010); Es, van. A., "Indiase textielarbeidsters uitgebuit voor C&A enH&M", De Volkskrant, 3 september, voorpagina, blz.1; Pascual, J. "Lesdamnées du prêt-à-porter" , Libération, 18 September 2010. Due tolack of supply chain transparency, ECCJ is unable to verify the nature14 KPR Mill website, " People"http://www.kprmilllimited.com/people/php KPR Mill has recently deleted this statement from its website8

to its low labour cost is what factory managementeuphemistically calls its 'unique labour model'. 15 Thecompany only employs young, unmarried women.While factory management states 16 to only employgirls aged 18 years or older, the monitoring studylocated girls aged between 15 and 17, and even a 13year-old girl, working at one of the company's spinningmills. Employment of child labourers is a violation ofIndia’s Child Labour (Prohibition and Abolition) Act1986 and a breach of the International LabourOrganisation’s Convention Prohibiting Child Labour. 17To maintain low labour costs the company prefers notto employ any permanent workers. A vast majority ofworkers is hired for a three-year period only.The company specifically targets young, unmarriedgirls mostly coming from socially and economicallymarginalised indigenous communities. These girls areoffered to receive a large amount of money, Rs.30.000 to Rs. 40.000 (approximately €500 to €650),after three years of employment, which could be usedto pay for their dowry. Although legally prohibited, thepayment of a dowry is still commonplace in India,where a girl cannot get married without providingmoney to her groom in exchange for taking her as hiswife. This labour recruitment system has come to beknown as the 'Sumangali scheme' where 'Sumangali'refers to a happy and contented married woman inTamil.This recruitment scheme is widespread in TamilNadu; it is estimated that more than 100.000 girls areemployed under the Sumangali scheme.Exploitative Working ConditionsAlmost all of the 9000 production workers at KPR Millhave migrated for work and are housed in dormitorieslocated on the factory complex. On the Arasur complexin Coimbatore, KPR Mill’s biggest production unit,5000 girls live in such dormitories. Each dormitory isshared by 12 girls at a time and is reused by differentgirls after each shift. It is impossible for anybodywithout permission to enter or exit this walled complexand leave is restricted to a few days a year when thegirls are allowed to visit their families. Workers are thusseverely restricted in their freedom of movement.As the lump sum of money is only paid after threeyears of work, workers feel forced to stay with thecompany for all three years. Local NGOs havedenounced this labour practice as a form of bondedlabour. 18KPR Mill prohibits the existence or formation of a tradeunion even though this contradicts Indian law andinternational treaties. As according to the factory15 Pascual, J. "Les damnées du prêt-à-porter" , Libération, 18September 2010.16 ibid.17 International Labour Organisation, C138, "Minimum AgeConvention, 1973 " and C182, " Worst Forms of Child LabourConvention, 1999". Convention 138 and 18218 See for instance "National Conference on 'Sumangalis: theContemporary Faces of Bonded Labourers", May 28, 2010, Maduarai,concept note, http://www.cecindia.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1962:national-conference-on-qsumangalis-the-contemporary-faces-of-bondedlabourersq-on-may-28-2010-at-madurai&catid=52:labour-and-societymain,management trade unions create a great deal ofunrest, they are denied access to the factories.Moreover, hiring young women is another tactic toprevent unrest. "With girls, it is easy to keepdiscipline", says factory management, they would beless inclined to form unions than boys. By restrictingthe movement of workers, the company effectivelyprevents the girls from reaching trade unions. "Boyswould never keep to that rule, they want to go on thestreets, always wanting more freedom. Girls are simplyhappy with what you give them" explains factorymanagement. 19According to the factory management workers earnabove the legally set minimum wage. Statements ofworkers and ex-workers, however, indicate thatworkers are paid less than the minimum wage. Aconsiderable amount is deducted from the workers'wages to pay for food and to save for the dowry. Theworkers are paid approximately 10 to 25 Euros amonth (Rs. 600 to Rs. 1500). After the completion ofthree years the company pays another 500 to 800Euros (Rs. 30.000 to Rs. 40.000). For textile millworkers the basic minimum wage fixed by theGovernment is 2.3 Euro (Rs. 147) per 8-hour work day.Thus, workers should have to be paid 57.5 Eurosinstead of only 10 to 25 Euros per month.In addition to low wages, workers have been subjectedto excessive working hours. While companymanagement claims that their employees don't workmore than eight hours a day, workers and ex-workerstold the researchers that they have to work 12-hoursshifts several times a week. The work week consists ofsix working days. On Sundays, where the workers aresaid to have the day off, workers would have to cleanthe dormitories and wash their clothes, leaving verylittle time to rest.Due to overwork and lack of sleep the workers areexhausted. There are many complaints of poor foodquality. In March 2009, 24 girls working at theSathyamangalam unit were admitted to the hospital forfood poisoning. Three girls later died. 20 The workers'health is furthermore compromised by work floorconditions. In the spinning area, humidity, heat andswirling cotton fibres all contribute to ill-health andbreathing difficulties. Workers often feel forced to takeoff their face masks to be able to breathe, yet workingwithout protective masks can cause more serioushealth problems. Some of the ex-workers have had toface surgery to remove balls of cotton fibres found intheir bowels. The cotton fibre was presumably ingestedwhile working with raw cotton without the protectivemask. Furthermore, some of the workers in thespinning unit have to work on roller-skates all day -without any protective gear - in order to improveproductivity.Due to the harsh working and living conditions some ofthe workers don't make the three-year mark and leavethe factory earlier. In some cases these girls do notreceive the money they have built up so far. Because19 Es, van. A, "Gevangen tussen fabrieksmuren voor bruidsschat", DeVolkskrant, 4 september 2010, Economie.20 Tamil newspaper Kalai Kathir, reported on one of the deaths, Erodeedition, 19 March, 2009.9

the workers don't receive an employment contract 21 -only an appointment letter - it is difficult to check, whatexactly has been promised to them and to undertakeaction.Legal Protection and Legal RealityWhile India may have laws in place against the typesof malpractice raised in this case study, the reality isthat the researchers could not identify that any actionhas been taken against the manufacturer by the IndianLabour Department or the general administration of theIndian government.For the parents of the girls working in the garmentfactory, most of whom are financially vulnerable andhave not had access to education themselves, allowingtheir daughters to continue to be subjected to theworking conditions means they will at least be givenmeals three times a day. For these reasonscommunities affected by the impacts of this supplier toEuropean companies feel powerless and largelyremain silent.Company ResponsesIn early September 2010, after a fact finding missionby journalists organised by the ECCJ, variousnewspapers reported on labour conditions at KPR Mill.In response to these media articles, some of thesebrands have announced to have ended theircooperation with the supplier or that they areconsidering terminating the relationship. The ECCJbelieves that EU companies have a duty of care toensure that human rights and environment arerespected throughout their operations and relations,including their supply chain. Companies should adhereto this duty by taking all necessary steps to prevent ormitigate violations. In order to be effective andincrease leverage to enable mitigation of the problems,coordination amongst buyers is crucial.Before publishing its findings ECCJ sent the draftreport to those companies mentioned in it, theresponses of these companies are summarised below:India, with the Indian Minister of Textile and with theTirupur Exporters Association.Carrefour:Carrefour explained its decision to end their businessrelationship with KPR Mill. It says no discussion waspossible with KPR Mill about their use of theSumangali scheme.Carrefour teamed up with a local NGO "to identifypossible cases of Sumangali Scheme in its supplychain and avoid starting to work with suppliers usingthis scheme."C&A:C&A claims to have already ended their cooperationwith KPR Mill in 2007 when it discovered the use of theSumangali scheme. It placed a test order (which couldhave led to the order of 58.000 men’s sweaters) withQuantum Knits in 2010, not knowing that in fact it wasdealing with KPR Mill. When this was discovered, C&Astates to have pulled back the order.C&A informed ECCJ that it is currently conductingextensive auditing of its Tirupur supply base in order tobe certain that practices as reported in the above casestudydo not occur in its supply chain.Gap:Gap, in its response to the ECCJ, denied to have anybusiness relationship with KPR Mill.Decathlon:After media reports about labour practices at KPR Mill,Decathlon (now Oxylane) conducted an audit at KPRMill. During this audit some critical non-conformitieswith Decathlon’s code of conduct were identified.Decathlon subsequently suspended its production arKPR Mill. KPR Mill was given the time to set up andimplement a corrective action plan. Decathlon statesthat recent audits have confirmed a strongimprovement (in relation to working hours, freedom ofmovement and hiring practices, amongst others). It hastherefore decided to re-launch its production at KPRMill.Kiabi did not respond.H&M:H&M responded that after several audits they havedecided to end their business relationship with KPRMill's garment division Quantum Knits. H&M states thatthey "don't have the needed trust for a continuedrelationship and has therefore decided to terminate thebusiness relationship."H&M informed ECCJ that it works together with otherbuying companies in the Brands Ethical WorkingGroup. This working group is discussing how buyerscan work together to prevent Sumangali Schemeamong spinning mills. H&M has also addressed theissue with the Apparel Export Promotion Council in21 Es, van. A, "Gevangen tussen fabrieksmuren voor bruidsschat", DeVolkskrant, 4 september 2010, Economie.10

THEPOWERFULAND THEPOWERLESSUnión Fenosa’s electricitymonopoly In ColombiaCase study information researched andprovided by the José Alvear RestrepoLawyers Collective in Colombia (CCAJAR)Colombia has had an armed conflict with legally andillegally armed protagonists for nearly 50 years. Thishas generated such grave consequences as forceddisplacement, forced disappearances and alongstanding humanitarian crisis in which more than 45per cent of the population lives in poverty. 22 In additionto these socio-political problems, the population ofclose to 10 million people in the seven departmentsalong Colombia’s Caribbean coast have had theirproblems exacerbated by the presence of a powerfulcorporate monopoly that provides this region’selectricity supplies - Spain’s commercial energy giant,Unión Fenosa. 23In this case study, CCAJAR reports the claims madeby civil society organisations, trade unions, workersand affected communities in the region that thisEuropean MNE has either committed, or is otherwiseimplicated in, violations to internationally recognisedhuman rights. Yet, as this case study reveals, thefailure of the country’s legal system to properlyinvestigate the company’s activities has left seriousquestions unanswered and many people withoutaccess to justice.MNEs, Paramilitarism and Trade UnionsThe process of privatising the Colombian electricitysector, including the entrance of Unión Fenosa into themarket, took place amid strong opposition by tradeunions to the sale of this vital public service. Thisresistance was brutally silenced however, including22 2008 Annual Report of the United Nations High Commissioner forRefugees (16 June, 2009) and Report by the United Nations HumanRights Commissioner on the situation in Colombia, Bogota, 2007,p.37.23 In 2009, Gas Natural purchased 95% of Unión Fenosa creating oneof the 10 largest utilities in Europe: “Unión Fenosa Aprueba su Fusióncon Gas Natural, que Canjeará Tres de sus Acciones por Cinco de laEléctrica”. Cotizalia Magazine, Madrid, 23 April, 2009. Gas Natural andthe majority of its shareholders are also European companies: AnnualReport by the Gas Natural Corporate Government, 2008, p.4.Photo provided by CCAJARthrough the systematic murders of eight unionmembers who worked at Unión Fenosa subsidiarycompanies, Electrocosta and Electricaribe. CCAJARreports claims by trade unions and others inColombian civil society that members of illegalparamilitary groups were behind the murders, and thata document written by Unión Fenosa companies mayhave played a role in these murders that should befully investigated in a court. 24MNEs operating in Colombia have previously beenimplicated in paramilitary activities with some seniorparamilitary leaders claiming a number of MNEsfinance paramilitary operations in the country. 25 Thecriminal investigations carried out by Colombian publicauthorities in relation to the involvement of companiesin such activities have made little progress, despiteone US company, Chiquita Brands, pleading guilty in aUS court and being fined US$25 million for financingparamilitary activities, and other companies, forexample the Dole Food company, facing an ongoingcivil lawsuit in California. 26 This weakened rule of law24 Documentation by the Central Workers Union (CUT) and theElectricity Workers Trade Union (SINTRAELECOL). See also theRuling for the Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal hearing on public services,Bogota, 8-10 March, 2008.25 For example, “Mancuso Dice que Directivos de Postobón y BavariaTenían Conocimiento de los Pagos de estas Empresas a losParamilitares.” Semana magazine, Bogota, 17 May, 2008. See also:“Nos Quieren Extraditar Cuando Empezamos a Hablar de Políticos,Militares y Empresarios.” Verdadabierta.com, Bogota, 11 May, 2009.26 US vs. Chiquita Brands, US District Court of the District ofColumbia, No. Criminal 07-055, 19.03.07. In 2009, family members ofother victims filed a lawsuit in California (USA) against the Dole FoodCo. for having made million dollar payments to paramilitary groups inColombia, though a ruling has yet to be issued in this case: “Demanda11

and alarming rate of impunity for the most serious ofcrimes is further demonstrated by the conviction rate ofmurdered Colombian union members over the last 23years: of the 2,709 murdered, there have only beenconvictions in 118 cases. 27The failure by the legal system to bring these humanrights violations to justice led segments of Colombiancivil society to convene an international opiniontribunal. The Permanent People’s Tribunal, a nongovernmentalbody that includes experts ininternational law, human rights and internationalhumanitarian law, held sessions based on internationalconventions through several public hearings from 2005to 2008. It considered evidence in the case of the eightmurdered Unión Fenosa trade union members,including a document acknowledged by Unión Fenosato having been written by two of the company’ssubsidiaries in Colombia, Electrocosta andElectricaribe. The document branded members of atrade union to which its workers belonged as part ofextremist guerrilla groups. This is a life-threateningallegation in Colombia, as those branded becometargets, and in numerous cases victims, of paramilitarygroups and even of the public force – something thesubsidiary companies would or should have beenaware of. 28 The Tribunal’s final ruling found thatactivities by companies in the corporate group werecrucial in explaining the deaths of the eight tradeunionists. 29Labour RightsThe murder of unionised workers in Colombia’selectricity sector is not only a grave violation of humanrights, it also has significant consequences for thelabour rights of all workers. Workers who fear joiningunions are denied the ability to exercise their right tofreedom of association, and to participate in alegitimate and democratic process through which theycan stand up for their labour rights. In turn, lowermembership means the collective power of unions torepresent the best interests of workers is alsosignificantly weakened through reduced negotiatingpower.CCAJAR reports that contracts between Electricaribeand its workers include a clause for employees not toAcusa a Dole de Financiar a ‘Paras' en Colombia.” El Nuevo Heraldnewspaper, Miami, 29 April, 2009.27 2009 Annual Report by the International Trade Union Confederation(ITUC), June 2009, and “Informe de la CSI sobre Violaciones deDerechos Sindicales en 2008.” Escuela Nacional Sindical, Medellín,10 June, 2009.28 See for example the case of the Peace Community of San Jose deApartado. Before suffering a massacre of five people in February2005, they had been branded in public as being members of guerrillagroups. “Orden de captura a ex coronel Duque por masacre”.Verdadabierta.com, Bogotá, 24 Agosto, 2009.29 Ruling on Public Services, Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal: Bogotá, 8–10 March, 2008. For more information on the Permanent Peoples’Tribunal, see: www.internazionaleleliobasso.it/index.php?op=6join trade unions in exchange for receiving a bonus, 30which potentially constitutes a violation to theInternational Labour Organisation Convention thatgrants workers the right to freedom of association.Furthermore, the average monthly salary of the 6,000subcontractors working for Unión Fenosa subsidiariesin the country is reported to be less than half theaverage monthly salary in the electrical sector and isnot enough to cover basic family living costs 31 - aviolation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.Abuse of Power and ElectrocutionsCommunities from the Caribbean coast have reportedbeing subjected to power cuts, reconnections,overbilling and undeclared electricity rationing. In socalledmarginalised neighbourhoods, 32 where 69.7 percent of the population live in poverty, there have beenreports of up to 10 unannounced interruptions occuringper day, with some cut-offs lasting up to severaldays. 33 Complaints concerning billing have also beenabundant. In the Las Malvinas neighbourhood inBarranquilla, the population gathered all of the irregularbilling from 2007 and 2008 and documented 160cases, with at least eight different anomalies of adiverse nature. 34Serious claims have also been made about the safetyof the electricity infrastructure provided by UniónFenosa companies, including a failure to protect localcommunities from the risk of electrocutions. Whilethere are no comprehensive official statistics for fatalelectrocutions in Colombia, reports of deadlyelectrocutions are very common. For example, fromJanuary to May 2008 in the area of Barranquilla,Atlantico, 12 people died from electrocutions, with afurther five people electrocuted in the period from Juneto August. 35It is claimed many electrocutions occurred due topoorly installed cables and insufficient maintenance,but the companies deny any responsibility, alleging30 Interview by CCAJAR with the Central Workers’ Union (CUT) –Bolivar Chapter on 19 May, 2009.31 Interview by CCAJAR with SINTRAELECOL member in Cartagenaon 8 July, 2009, and Silverman, J. and Ramírez, M. (October 2008)“Informe: Unión Fenosa en Colombia.” Escuela Nacional Sindical(ENS). Medellín.32 These neighbourhoods are regulated by Resolution 120 of theEnergy and Gas Regulatory Commission (2001) and are affected bydifferent kinds of discrimination, including a single bill being issued foran entire neighbourhood (inhabitants must collectively take onresponsibility for payment, even for late bills); the neighbourhood hasto cover the costs for the installation of community meters, leaks, andthe billing process – none of which has to be done by otherconsumers.33 Material gathered by CCAJAR from interviews in Barranquilla,Cartagena, Monteria and Santa Marta. See also: Mancera, CarlosArturo: “Por Qué las Lluvias Infartan el Sistema Eléctrico deBarranquilla?” El Heraldo newspaper, Barranquilla, 3 May, 2008, p.4a.34 Documentation of the Las Malvinas neighborhood, Barranquilla, May2009.35 Documentation from Red de Usuarios, Barranquilla, presented atthe Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal, Lima Chapter, 13-16 May, 2008. “17Personas Han Muerto por Accidentes Eléctricos.” La Libertadnewspaper, Barranquilla, 24 August, 2008, p.4d.12

that people in poor neighbourhoods are trying toconnect to the electrical grid without authorisation.However, there are multiple cases of electrocutionsthat fall within the responsibility of the subsidiaries ofUnión Fenosa as evidenced by a court order in 2009that found one of the subsidiaries found guilty of failingto maintain the cables at a gas station, which resultedin the electrocution of two people, killing one of them. 36the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Peoples(1976); the Declaration on the Right to Development(1986); and the European Criminal Law Convention onCorruption (2002). However, CCAJAR reports that noMNE has ever been convicted in Colombia for itsresponsibility in the commission of human rightsviolations.Economic and Social RightsGiven the alarming culture of impunity within theColombian legal system, and the absence ofindependent investigation, there is little real chance forthe victims and their families to carry out legal actionsagainst MNEs. Confronted with an environment ofintimidation and financial difficulty, they risk beingstigmatised, threatened and even murdered shouldthey seek justice through Colombia’s legal system forthese human rights violations. 37In addition to its ruling on Unión Fenosa’s eightmurdered trade unionists, the Permanent People’sTribunal also issued a verdict convicting 43 companiesand the Colombian State as responsible for multipleviolations to individual and collective rights; includingthe right to life and physical integrity, the right to healthand food, women’s rights, the right to freedom andfreedom of movement, labour rights, and the right tolive a life with dignity. 38 Unión Fenosa was one of anumber of MNEs notified of the accusations and theruling against it by the Tribunal. In response, however,the company simply stated that it availed itself ofinternationally agreed human rights, labour,environmental and anti-corruption principles forbusinesses established by the United Nations. 39The Colombian government has ratified manyinternational treaties on economic, social, cultural andother human rights. CCAJAR argues that the rights ofthe Colombian people under a number of theseinternational treaties appear to have been violated,including: the Universal Declaration of Human Rights(1948); the International Pact on Economic, Social andCultural Rights (1966); the International Pact on Civiland Political Rights (1966); the Universal Declarationon the Eradication of Hunger and Malnutrition (1974);36 “Electrocosta tendrá que pagar indemnización”. El Universalnewspaper, Cartagena, 10 June, 2009.37 See claims made by the Inter-Church Commission of Justice andPeace (www.justiciaypazcolombia.com), CCAJAR(www.colectivodeabogados.org) and the National Movement of Victimsof State Crimes (www.movimientodevictimas.org).38 Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal Ruling: Bogota, Op cit, 21-23 July,2008.39 For more information about these principles, see:www.unglobalcompact.org13

FAILURE TOCOMMUNICATESteel conglomerateArcelorMittal in South AfricaCase study information researched andprovided by GroundWork – Friends of theEarth South AfricaArcelorMittal is one of the world’s largest steelcompanies. Registered in the European tax haven ofLuxembourg and headed by one of the world’s richestindividuals, the company has operations in more than60 countries. 40 ArcelorMittal’s Vanderbijlpark steelplant near Johannesburg, South Africa, is the largestinland steel mill in sub-Saharan Africa 41 and returnedan operating profit in excess of 12 billion South Africanrand in 2008 despite the global economic downturn.But as groundWork reports in this case study, theactivities of this European steel conglomerate havealso been the centre of serious claims ofenvironmental pollution, displacement and degradationof labour rights.Air and Water PollutionThe history of pollution coming from ArcelorMittal’ssteel plant is formally acknowledged by South Africanpublic authorities and is a matter of public record. 42Pollutants from the plant’s industrial waste havereportedly seeped through the ground, contaminatedlocal aquifers and affected the groundwater of nearbycommunities. 43ArcelorMittal is also one of the top three polluters ofparticulate matter, sulphur dioxide and carbon dioxidein the Vaal Triangle industrial region, where anestimated 65 per cent of chronic illnesses in the areaare reported to be caused by industrial pollution. 4440 See: www.arcelormittal.com/index.php?lang=en&page=941 ArcelorMittal South Africa Limited Sustainability Report 2008, p.8.42 See for example, the Emfuleni Local Municipality IntegratedDevelopment Plan for 2007 – 2012, the West Rand DistrictMunicipality Disaster Management Plan, Revision 8, May 2006, pp.24,32 and 132, and the Department of Environmental Affairs AndTourism, Environmental Quality and Protection Chief Directorate: AirQuality Management and Climate Change: Vaal Triangle AirshedPriority Area Air Quality Management Plan, 2009, p.ii.43 Cock, J. and Munnik, V. (2006) Throwing Stones at a Giant: anaccount of the struggle of the Steel Valley community against pollutionfrom the Vanderbijlpark Steel Works, Centre for Civil Society,University of KwaZulu-Natal.44 Scorgie, Y. (2004) Air Quality Situation Assessment for the VaalTriangle Region, Report for the Legal Resource Centre, South Africa.Withholding InformationPhoto supplied by GroundWorkDespite these serious public health concerns,ArcelorMittal and the South African government areactively withholding information that would help thepublic and civil society to assess recent attempts bythe company to clean up its pollution, and whether thecompany’s plans for reducing environmental damagein the future will be effective. Following mounting publicpressure in the late 1990s, ArcelorMittal was forced topartake in an environmental management planbetween 2001 and 2003. This included determiningthe levels of pollution at that time to use as a baselineagainst which progress in rehabilitating the pollutedareas could be measured. 45The government, however, agreed that theenvironmental management plan could be kept secretand will not allow full public disclosure of theinformation it contains, including the level of pollutioncaused by ArcelorMittal. 46 Without this information thepublic is unable to understand the full extent ofArcelorMittal’s pollution, whether the environment willever be properly rehabilitated and protected fromfurther degradation, or whether the measuresundertaken will address the impacts of past andpresent pollution on the lives of people living in thecommunities near the plant. 47 The withholding of thisinformation is also inhibiting genuine and meaningfulparticipation in legitimate government processes, suchas the ‘waste site public monitoring committee’ thatseeks to monitor the impacts of the ArcelorMittal wastesite on society and the environment. 48Despite various attempts at negotiating access to theenvironmental management plan with the SouthAfrican subsidiary and with the MNE’s head office inLuxembourg, ArcelorMittal has refused to release the45 Cock, J. and Munnik V. (2006) Throwing Stones at a Giant Op Cit.46 Mittal Steel Vanderbijlpark and the Environment, brochure inHallows, D. and Munnik, V. (2006) Poisoned Spaces: Manufacturingwealth, producing poverty, GroundWork, p.142.47 Miskun, A. et al. (May 2008) In the wake of ArcelorMittal:The global steel giant’s local impacts, Czech Republic, p.24.See: http://bankwatch.org/documents/mittal_local_impacts.pdf48 Personal communication between groundWork staff and SamsonMokoena, the coordinator of the Vaal Environmental Justice Alliance.14

information stating it ‘will not be in the best interest ofArcelorMittal South Africa’. 49Retrenchments and RelocationsArcelorMittal’s operations also have impacts beyondthe environment with the company’s activities alsocontributing to popular mobilisation and legalchallenges.Following a large number of retrenchments from thecompany in the late 1990s, 50 a grassroots resistancemovement, called the Vaal Working Class CrisisCommittee, was formed and has successfullychallenged the subsidiary on issues such as unfairlabour practices. For example, the Committee hasreported that ArcelorMittal retrenched workers butpromised to re-employ them when the job marketimproved. When the job market improved, ArcelorMittaldid begin hiring people again, but did not re-employ theretrenched workers. It is also reported thatArcelorMittal has fired those responsible for not reemployingthe retrenched workers as promised – anacknowledgement the company was not properlymonitoring and enforcing its procedures – but theretrenched workers have still not been re-employed,and the company is facing an ongoing court challengefrom the Vaal Working Class Crisis Committee on thisissue. 51Local communities in the region of the steel plant havealso been affected by displacement issues. In additionto the pollution of their groundwater, a series of legalchallenges and out-of-court settlements resulting in‘buy-outs’ by ArcelorMittal, has meant that the localpopulation have effectively been moved off their land. 52ArcelorMittal has then enclosed this land with electricfences to keep the remaining families from grazing onthe land that was in the past used as common landdespite ownership. This area of small holdings is nowbest described as a ‘ghost community’ of abandonedand demolished homes, with only two familiesremaining of the original 500.49 Letter from CEO Nonkululeko Nyembezi-Heita to groundWork, 8July, 2009.50 According to the National Union of Metal Workers of South Africaand Solidarity, the facility’s workforce has been reduced from 44,000 inthe 1980s to 12,200 in 2004. Since ArcelorMittal took operations, theNational Union of Metal Workers has reported further large job losses.51 Discussions between GroundWork staff and Mashiashiye PhineasMalapela, organiser with the Vaal Working Class Crisis Committee, 13August 2009.52 Cock, J. and Munnik, V. (2006) Throwing Stones at a Giant, Op Cit.15

APPLYING THEECCJ’SPROPOSALS<strong>FOR</strong>LEGISLATIVECHANGEThe case studies presented in this report involvemultifaceted political, economic and social issues. Therange and complexity of the human rights violationsand breaches of environmental standards highlighted,mean that no silver bullet can solve all of the issuesraised in each of the case studies. As the analysisbelow indicates however, the ECCJ’s proposals couldsignificantly improve the accountability of Europeancompanies for their actions outside of the EU andassist victims in obtaining redress where thesecompanies are found to have behaved inappropriately.1. Parent CompanyLiabilityThe corporate group structures of MNEs usuallyinvolve the coordination of a number of separatecompanies with a parent company owning shares insubsidiary companies in other countries. Under currentcompany law, each company has its own separatelegal ‘personality’ which means that despite this closerelationship, each company is legally liable for its ownactions, but generally not liable for the civil or criminalactions of other companies in the group.An effective way to improve compliance with humanrights and environmental standards by businesses intheir operations outside of the EU would be to ensurecompanies do not use corporate structures to hidebehind. It is also important to ensure that companieswho benefit from the profits of the behaviour of relatedcompanies also share responsibility for the negativeeffects of those operations. The ECCJ proposes thatthe best way to do this is to reform the current law bysuspending the doctrine of separate legal personalityin relation to human rights and environmental impacts,so that parent companies can be held legallyresponsible for the violations of their subsidiarycompanies. 5353 Gregor, F. and Ellis, H. (2008) Fair Law, p.12, Op Cit.In the cases of ArcelorMittal and Unión Fenosa,affected stakeholders were unable to convincegovernments, local law enforcement and other publicauthorities to take action on allegations of humanrights and environmental violations, and stakeholdershad no legal ability to prosecute subsidiary companiesfor these public offences. The application of the ECCJproposal to enhance the direct liability of parentcompanies would provide affected stakeholders - suchas local communities, workers, and non-governmentalorganisations with interests in preventing human rightsand environmental violations - with the ability to bringan action in European courts against the parentcompany for the public offence of the subsidiary. Byproviding this improved access to justice, this reformwould allow for the activities of the corporate group tobe properly investigated, and those affected byviolations to have their concerns addressed throughdue legal process and to be able to claim damages incivil actions.It should be noted that such reforms are not withoutprecedent, with some recent developments in the lawacknowledging the reality of corporate operations. Forexample, European competition law can now lookbeyond the separate legal entities, and treat thecorporate group as the single economic unit that it is.The European Court of Justice, has made severalcompetition law judgments imposing penalties even onforeign parent companies. 54Furthermore, parent companies are already required toprepare consolidated financial statements that includethe accounts of subsidiary undertakings irrespective ofwhere the subsidiaries are established, in accordancewith the European Seventh Company Directive onConsolidated Accounts. The single economic entityperspective is also a feature of some international softlaw, such as the Guidelines for MultinationalEnterprises set by the Organisation of EconomicCooperation and Development. 55These laws and guidelines are exceptions however,and companies are still legally allowed to use artificialcorporate divisions to avoid exposure to anyresponsibility for the environmental or human rightsconsequences. Given the significance of human rightsand the environment as policy areas, however,particularly in relation to competition law or financialaccounting, the ECCJ sees suspending parent54 For example, the Dyestuffs case, Case 48/69 etc ICI v Commission[1972] ECR 619. While the economic entity doctrine has beencriticised for not respecting the doctrine of separate legal personality,the European courts and Commission have relied on the economicentity approach on subsequent occasions. See for example GenuineVegetable Parchments Association OJ [1978] L 70/54 and Johnsonand Johnson [1981] 2 CMLR 534: Fair Law, p.11, Op Cit.55 Seventh Council Directive 83/349/EEC of 13 June 1983 based onArticle 54 (3) (g) of the Treaty on consolidated accounts (OJ L 193,18.7.1983, p. 1–17): see Art. 1 and 2 of the directive. The duty to drawconsolidated accounts is also recognised in the standards of theUnited States' Financial Accounting Standards Board, and theInternational Accounting Standards Board. See also point I.1 of theGuidelines for Multinational Enterprises available atwww.oecd.org/dataoecd/56/36/1922428.pdf: Fair Law, p.11, Op Cit.16

company liability as essential to ensuring bettercompliance with human rights and environmentalstandards.2. Duty of CareThe Indian case study of KPR Mill differs from the lasttwo case studies in that instead of the mainrelationship being one of a European parent companyand its subsidiary based in a country outside the EU,there is a supply chain relationship. That is, aEuropean company has entered into a contract with asupplier based outside the EU for the supply of goodsor services. Companies structure their businessrelations in this way for many reasons - including fortax purposes, because the companies lack theexpertise to provide the goods and servicesthemselves, and sometimes so that the company canpass on the risks of production to someone else.The strong bargaining power of large MNEs allowsthem to negotiate arrangements with suppliers thatresult in downward pressures on prices and deliverytimes that contribute to higher sustainability risks insupply chains. Despite this significant influence oversuppliers, under existing European laws a companymay be found to have a duty of care with respect to theimpact of the supplier’s operations only in very limitedsituations - where the company is directly involved inthe operations or is driving the supplier’s decisions.Extensive civil society pressure has forced someEuropean MNEs operating in brand-sensitive sectorsto improve their supply chain management but,generally, this limited duty of care has discouragedcompanies from implementing better and moretransparent management of environmental and socialimpact, and those affected find it difficult to obtaininformation proving the company’s direct involvement.The ECCJ believes that even in cases where there isnot a parent-subsidiary relationship, a company shouldstill have a duty of care in situations where thatcompany is able to exercise significant influence overthe operations of a commercial partner and thoseoperations can have an adverse impact upon humanrights or the environment. If this proposal became law,European companies such as those who purchasefrom KPR Mill or others in the Indian garment industrywould have to take reasonable care in ensuring thatviolations involving abuse of young workers did nottake place at any level of the supply chain that fallswithin the company’s sphere of responsibility. 56 TheECCJ’s proposals would also require Europeancompanies supplied by KPR Mill to exercise a duty ofcare through initiating processes to identify risks ofhuman rights and environmental violations in thesupply chain and, most importantly, take steps to avoidtheir consequences. This might include being aware of56 For further discussion about operations within a company’s ‘sphereof responsibility’ see Fair Law, pp.21-26, Op Cit.the wider context of the Indian garment industry andreports of past violations, and assessing the effects ofonerous contractual termson the manufacturer.3. Environmental & SocialReportingA significant obstacle to better protection of humanrights and the environment is a lack of access toinformation about how a company’s operations canimpact on those areas. Without proper information –such as was seen in the South African case study -those affected by the company’s operations and otherstakeholders are unable to make an independentassessment of the true cause and extent of theimpacts. From a company perspective, this lack ofinformation means companies will fail to build trust, orhave proper engagement with, affected communitiesabout issues of risk.The ECCJ’s third key proposal for reform requires anexpansion of the current non-financial reportingobligations under the EU Accounts ModernisationDirective, 57 and various national-level laws 58 to includespecific environmental and social reporting thatprovides accurate, comprehensive and comparableinformation that is appropriate for all relevantstakeholders and not just shareholders. 59An EU-level mandatory requirement for annual socialand environmental reporting would help increasetransparency and assist those seeking to hold acompany accountable for breaches of the primaryobligations set out in the other ECCJ proposals. Itwould also contribute to processes that would helpidentify a company’s risks and impacts on humanrights and the environment, and could transform57 See Directive 2003/51/EC of the European Parliament, and of theCouncil of 18 June 2003, amending Directives 78/660/EEC,83/349/EEC, 86/635/EEC and 91/674/EEC on the annual andconsolidated accounts of certain companies, banks and other financialinstitutions, and insurance undertakings. (OJ L 178, 17.7.2003, p. 16–22). See also Article 46 of Fourth Council Directive 78/660/EEC of 25July 1978 based on Article 54 (3) (g) of the Treaty on the annualaccounts of certain types of companies, and Article 36 of SeventhDirective. (OJ L 222, 14.8.1978, p. 11–31): Fair Law, p.11, Op Cit.58 For example, see: Section 417 of the United Kingdom’s CompaniesAct 2006 which obliges quoted companies to report information suchas policies, and the effectiveness of policies, on: business impacts onthe environment; employees; social and community issues; and aboutpersons with whom the company has contractual or otherarrangements which are essential to the business of the company.See also the Danish Environmental Protection Agency survey ofefficiency and impact on Danish 1995 Green Accounts (EnvironmentalProtection Act as amended in June 14 1995 by Act No. 403, andstatutory order No. 975, of December 15, 1995); Dutch EnvironmentalManagement Act (EMA) as amended on 10 April 1997; Norwegian1998 Accounting Act (Regnskapsloven, LOV-1998-07-17-56), SwedishAccounting Act amended in 1999 (Law of Accounts (1995:1554); andFrench New economy regulations (Loi relative aux nouvellesrégulations économiques n°2001-420 du 15/05/2001 as implementedby Decree 2002-221): Fair Law, p.28, Op Cit.59 Gregor, F. and Ellis, H. (2008) Fair Law, p.29, Op Cit.17

corporate social responsibility reporting into a powerfultool for encouraging positive practice withincompanies.If this reform was in place, it would require each of theEuropean companies mentioned in the case studies toreport their analysis of the potential and actual risks ofcompany operations violating, or being complicit in,violations of internationally agreed human rights andenvironmental standards, and give a clear descriptionof steps taken by the corporate group to prevent andeliminate those risks. For example, in the case ofsupply chain relationships, lack of transparency aboutworking conditions of supply chain manufacturers likeKPR Mill, and about the sources of origin for goods,are major obstacles to the promotion of moreresponsible consumption. Under the ECCJ proposal,European companies buying products sourced outsidethe EU would be required to map their supply andproduction chains, and report information such as thenumber of audits throughout the whole supply chain,the number of non-compliances found, correctiveactions taken, and how stakeholders have beeninvolved.In the ArcelorMittal case study, GroundWork reporteddifficulties in obtaining information about thecompany’s environmental impacts and its plans toaddress these impacts. An obligation on the MNE toproduce a comprehensive environmental report couldprovide communities impacted by pollution from thesteel plant with information to give them a betterunderstanding of the plant’s impact. ArcelorMittal andthe South African government would also havebenefited from a process that supported betterreporting through early identification of risks, as thiswould have allowed violations to be avoided andpossible damages mitigated much earlier. If regularreporting on environmental issues was alreadyavailable, this would have also significantly reducedthe burden of the company and government inpreparing the environmental management plan.In addition to the benefits already outlined, betterreporting would mean companies could decrease coststhrough more efficient environmental operationalmanagement and avoid costly disputes. 60 Mostimportantly of all, it would encourage mutuallybeneficial accountability to all stakeholders, includingthe government. More open reporting would also easethe burden of proof for plaintiffs, which would increasethe ability of local communities to establish their casefor just compensation for the damage suffered.60 For example, Fair Law notes the “Danish Environmental ProtectionAgency has conducted a survey of efficiency and impact on 550Danish companies. According to the survey, 41% of companiesbelieved they had achieved environmental improvements throughgreen accounting. Among these 70% emphasized energy, 50%highlighted water and waste, 40% consumption of resources, 30%wastewater and additives, 20% reduced emissions into the air and10% emissions into the soil, p.28, Op Cit.Additional CrosscuttingProposalsA. Expanding DirectorDutiesThe ECCJ proposes that the company law dutiesimposed on directors of European companies beexpanded to include the requirement to identify andminimise environmental and human rights risks. 61 Thisexpansion of director duties is not uncommon in otherpublic interest laws with some countries alreadybeginning to implement legal reforms. For example,the new Companies Act in the United Kingdom obligesdirectors to have regard for the environmental andsocial impacts of their decisions, while the CanadianEnvironmental Protection Act obliges directors toexercise due diligence on the company’s compliancewith that Act. 62In the Colombian case study, this would mean that themanagement of the European parent company, UniónFenosa, would be required to ensure that members ofthe corporate group implement complementarypolicies, processes and training into their existing riskmanagement frameworks. These procedures shouldproactively anticipate actual and potential human rightsand environmental risks that could result from thebusiness’s operations. These duties would also applyto directors of European companies in significantsupply chain relationships, such as European retailerswho purchase clothes from the Indian garmentindustry.As with all risk management, projects and operationsshould be assessed individually and on an ongoingbasis, but certain companies, geographical regionsand industry operations will involve common types ofrisks. This will also be the case with human rights andenvironmental risks, and accumulated knowledgeacross industries will help minimise the process of riskassessment in these areas. Under the ECCJproposals, companies undertaking this riskassessment would be provided with clear guidance onwhat human rights and environmental standards apply,increasing certainty for business about how toapproach addressing risks in these areas. 6361 Gregor, F. and Ellis, H. (2008) Fair Law, p.18, Op Cit.62 See section 172 of the United Kingdom’s Companies Act 2006.Although the UK requirement would be insufficient on its own in thesesituations, as this duty is only to the company and not to affectedstakeholders: Fair Law, p.18, Op Cit.63 The ECCJ proposes that the appropriate standards are thoseagreed treaties listed in Annex III of the Generalised System ofPreferences as the EU has already identified these treaties asnecessary and desirable for sustainable development and goodgovernance. EU Generalised System of Preferences is set by CouncilRegulation (EC) No 980/2005, of 27 June, 2005. (OJ L 169 30.6. 2005,p. 1-43). A full list of the relevant conventions can be found at18

Once a comprehensive overview of risks is completed,steps to prevent risks of violations occurring, and tominimise the impacts of any violations that do occur,should be taken by the corporate group. Relevantexpertise should be used to formulate an appropriateapproach in each risk area but, in the Colombian case,this might involve actions such as: ensuringenforcement of disciplinary procedures and workingwith public authorities where paramilitary associationsare suspected; worker training and managementleadership on labour rights compliance; and workingmore closely with civil society organisations and publicauthorities.Furthermore, under current company law, directors’duties are normally only owed to a company’sshareholders, meaning that directors are not legallyaccountable to other stakeholders. Under ECCJreforms, however, other interested persons, such asnon-governmental organisations concerned withprotecting public human rights and environmentalinterests, would have the right to bring actions againstdirectors who breach their duties in relation to humanrights and environmental risks.B. Access to RemedyReform of the law in line with the ECCJ proposalsshould, in itself, lead to a reduction in cases ofviolations of human rights and environmentalstandards by subsidiaries of European companies.However, further reductions will also occur if the legalsystem also provides effective mechanisms of redressfor this type of corporate behaviour. The ECCJtherefore proposes that parent companies, companieswith a duty of care in commercial relationships, anddirectors who are convicted of public offences of thisnature, will be liable for effective, proportionate anddissuasive sanctions and remedies.In each of the three case studies, this would meanthat, in addition to sanctions such as fines,undertakings and orders to rectify damage to theenvironment, those affected communities and workerswould be entitled to legal damages if a court decidesthat they suffered damage because a companyviolated human rights or environmental standards.Legal redress for violations can be obtained in twoways. First, the victims might claim remedies in a civilaction in court. Second, the public offence should beinvestigated and punished by the relevant authorities.and to deter further wrongdoing. The courts should bealso able to order a convicted company to compensateall victims of the violation in question and not onlythose who were able to start legal proceedings.Actions for public offences such as breaches of humanrights or environmental standards should normally betaken against a company by the public authorities. Asboth the South African and Colombian case studieshave shown, some countries have a weakened rule oflaw preventing effective enforcement by publicauthorities. Public authorities in European states thenmight be discouraged from taking action because oflack of evidence and remoteness of the case - evenwhen they have legislative basis for such actions asproposed by the ECCJ. Therefore, the ECCJ proposesgiving affected communities and workers, or theirrepresentatives, the right to start court actions inEurope for defined public offences based on breachesof international law or principles.One of the key problems for the people of Colombia,as discussed above, is their inability to take effectivelegal action and receive justice and remedies for thenegative impacts they have suffered. Under theECCJ’s proposals, the legislative changes would allowchallenges for breach of an European statute to bebrought in courts by those with an interest in thealleged offence, particularly those Colombians living inthe affected communities, and where there is evidencesupporting allegations of damage caused by humanrights and environmental abuse.Where the affected communities do not have thefinancial means, or are in other ways intimidated orunable to bring a legal action due to weak rule of law,non-governmental organisations that meet appropriatecriteria for protecting the affected public interestswould also be allowed to bring a challenge. The nongovernmentorganisation could also present evidencethat a company - whether it be a parent or at the top ofa supply chain - and a company’s directors, has notfulfilled its obligations of reasonable care.Allowing private enforcement of public laws in theseways would again be consistent with the EuropeanParliament’s Corporate Social ResponsibilityResolution that called for a new mechanism to make iteasier for victims of corporate abuse to seek redress inEuropean courts.The proposals for parent company liability and duty ofcare would, in principle, enable those who havesuffered to claim damages against parent companiesin European courts through taking civil action.However, it is necessary to ensure that the height ofsuch damages is sufficient to compensate the victimshttp://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2005/june/tradoc_123910.pdf:Fair Law, p.18, Op Cit.19

CONCLUSIONThe case studies presented in this report involvemultifaceted political, economic and social issues. Therange and complexity of the human rights violationsand breaches of environmental standards suffered bythe local communities and workers mean that no singleapproach can solve all the issues that have beenhighlighted.There are, however, some common factors: thepresence or significant influence of Europeancompanies; serious claims implicating the operationsof those companies in the violations and breaches; anda weakened rule of law preventing the companiesbeing called to account for the allegations, andpreventing affected communities and workersaccessing a means to justice.The ECCJ’s proposals for legislative change areintended to help the lives of people who may bepolitically, socially or economically constrained fromenjoying some of the most basic rights that manyEuropean citizens have the privilege of taking forgranted. The ECCJ’s proposals do not recommendnew environmental or human rights standards. Theymerely provide mechanisms to increase the breadthand depth of compliance with standards that alreadyexist, which are enshrined in international treaties thatenjoy strong international consensus. The proposalscould significantly improve the accountability ofEuropean companies for their actions outside of theEU and assist those affected by those actions to obtainredress where these companies are found not to havecomplied with human rights and environmentalstandards.companies, can, however, provide equitable protectionfor all stakeholders. Industry could then use thiscommon foundation as a platform on which to buildcorporate responsibility programs up to best practice,while affected stakeholders would be ensured aminimum standard of protection.While human rights and environmental protection mustremain at the heart of any such legislative change, thebenefits of the proposals for business should not beneglected. Clarity about what human rights andenvironmental standards should be applied will alsoprovide businesses with greater certainty about theirimpact abroad. This will encourage compliance withthose standards, helping to reduce a company’slitigation, operational and reputational risk.Consistently applied rules on corporate accountabilitywill also help provide a more level playing field forcompanies registered in one of the world’s biggestmarkets, and those who want to operate in it. Unlikethe current business environment, more effectiveenforcement laws will mean companies who violatehuman rights and environmental standards will be lesslikely to achieve competitive advantage byundermining those who comply.Through its power to implement legally bindingreforms, the EU has a unique opportunity to not onlylead the debate internationally, but also to takeeffective steps to enhance compliance withinternationally agreed human right and environmentalstandards, and to help those impacted by violations ofthose standards achieve greater access to justice.The ECCJ’s legislative reforms can be achieved bybuilding on well-established precedents andconsolidating progressive regulatory and policyframeworks already in place. From a legal perspective,many of the ECCJ’s proposals mirror laws that haveprecedent in other areas of public policy, such ascompetition law, financial accounting, environmentallegislation and national-level reporting laws. Humanrights and environmental protection are clearly just assignificant as these areas and, by their very nature andconsequence, provide strong justification for extendinga similar regulation framework to them.Years of attempting to address the impact of MNEs onhuman rights and environmental protection solelythrough voluntary initiatives, unenforceable codes ofconduct and non-binding corporate social responsibilityprograms has confirmed the lack of intellectual tractionof such approaches, created cognitive dissonance inthe corporate marketplace, and proven to be evenstarker in practice. Effective guidance for businessthrough regulation, to be applied consistently across all20

PUBLISHED BYCase Study 1 “Trapped InChains: Exploitativeworking conditions inEuropean fashionretailers’ supply chain”As part of the campaign Rightsfor People Rules for BusinessNovember 2010The European Coalition forCorporate Justice (ECCJ) is thelargest civil society networkdevoted to corporateaccountability within theEuropean Union. Founded in2005, its mission is to promotean ethical regulatory frameworkfor European business,wherever in the world thatbusiness may operate. TheECCJ critiques policydevelopments, undertakesresearch and proposessolutions to ensure betterregulation of Europeancompanies to protect peopleand the environment. TheECCJ’s membership includesmore than 250 civil societyorganisations in 16 Europeancountries. This growing networkof national-level coalitionsincludes several Oxfamaffiliates, national chapters ofGreenpeace, AmnestyInternational, and Friends of theEarth; the Environmental LawService in the Czech Republic,The Corporate Responsibility(CORE) Coalition in the UnitedKingdom, the Dutch CSRplatform and the FédérationInternationale des Droits del'Homme (FIDH).For comments or furtherinformation, please contact:The European Coalition forCorporate Justiceinfo@corporatejustice.orgTel: +32 (0)2 893-10-26www.corporatejustice.orgResearch and information forcase study 1 is provided byorganisations of the CampaignAgainst Sumangali Scheme(CASS). CASS is a coalition ofcivil society organisations inIndia that works together toraise awareness about theSumangali Scheme andadvocates for an end to thisexploitative system.Case Study 2 “ThePowerful And ThePowerless: UniónFenosa’s electricitymonopoly In Colombia”Research and information forcase study 2 is provided byCCAJAR - the José AlvearRestrepo Lawyers Collectivewww.colectivodeabogados.orgCCAJAR is a Colombian nongovernmentalhuman rightsorganisation with 26 years ofexperience in the prevention,defence, and promotion ofhuman rights. CCAJARcontributes to the fight againstimpunity and to the constructionof a just and equitable societywith political, social, culturaland economic inclusion, as wellas working toward the respectfor the full development of therights of peoples to sovereignty,self-determination,development, and peace withsocial justice.Case Study 3 “Failure toCommunicate: SteelconglomerateArcelorMittal in SouthAfrica”Research and information forcase study 3 is provided byGroundWork - Friends of theEarth South Africawww.groundwork.org.zaGroundWork is a non-profitenvironmental justice serviceand developmentalorganisation that seeks toimprove the quality of life ofvulnerable people in SouthAfrica, and increasingly inSouthern Africa, throughassisting civil society to have agreater impact onenvironmental governance.groundWork places particularemphasis on assistingvulnerable and disadvantagedpeople most affected byenvironmental injustice.This publication has been produced withthe assistance of the European Union.The contents of this publication are thesole responsibility of the EuropeanCoalition for Corporate Justice (ECCJ)and can in no way betaken to reflect the viewsof the European Union.Cover Art: Diversified Portfolio Options,Casey McKeeReport printed by BeëlzePub,Brussels.This publication has beenprinted on 100% recycled and chlorinefreepaper stock using bio vegetablebasedinks.21

ECCJ SecretariatRue d’Edimbourg 261050 Brussels, BelgiumPhone: +32 (0) 2 893 10 26Fax: +32 (0) 2 893 10 35Email: info@corporatejustice.orgwww.corporatejustice.org