Why Jamal Can't Get a Job - The University of Chicago Booth ...

Why Jamal Can't Get a Job - The University of Chicago Booth ...

Why Jamal Can't Get a Job - The University of Chicago Booth ...

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Economists and sociologists have long agreed that African Americanshave more trouble landing a job than their white counterparts do. Butwhat stops employers from opening the door to candidates who lookgood on paper? Associate pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> economics Marianne Bertrandand Sendhil Mullainathan say it’s all in the name.Looking for a job is hard work, nomatter what shape the economy is in.It all starts with the resumé—a onepagechance to sum up a lifetime <strong>of</strong> accomplishmentsin a way that stands out from ahundred others. But many employers neverget past the name, according to a study byBertrand and Mullainathan, associate pr<strong>of</strong>essor<strong>of</strong> economics at M.I.T., titled, “AreEmily and Brendan More Employable thanLakisha and <strong>Jamal</strong>? A Field Experiment onLabor Market Discrimination.”Between June 2001 and May 2002, theysent out about 5,000 resumés in responseto 1,300 help-wanted ads in Boston and<strong>Chicago</strong>. <strong>The</strong>y found that resumés withwhite-sounding names received 50 percentmore calls than those with AfricanAmerican–sounding names, despite identicalqualifications.<strong>The</strong> result didn’t surprise them. “In the1960s, [<strong>University</strong> Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Economicsand <strong>of</strong> Sociology] Gary Becker wrote abouttaste-based discrimination, which is thatemployers are prejudiced and that theyhave a real dislike for dealing with AfricanAmerican employees,” she said. But economictheory also takes into account statisticaldiscrimination, Bertrand added. “Weknow that, on average, African AmericansDan DryMarianne Bertrand, a member <strong>of</strong> theGSB faculty since 2000, is associatepr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> economics. Bertrand’sresearch interests include corporatefinance and labor economics.Summer/Fall 2003 <strong>Chicago</strong> GSB15

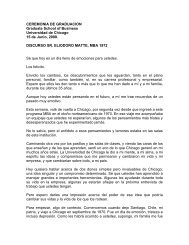

FEATURE FACULTY RESEARCHhave lower education. People use race as a signal <strong>of</strong> theseunobserved characteristics. In our study, the names areclearly triggering race, but the issue is that they mightalso be triggering social background. And you’ve got tobe careful there because African Americans, on average,are more likely to be unemployed, earn lower wages,and have less education than whites.”But the authors were alarmed by another aspect <strong>of</strong>the study. Improving the credentials on the resumésbrought more responses for white applicants, but it hadno effect for black job seekers, Bertrand said. “What isthe incentive, being African American, to invest in thoseextra skills—to take that evening class, to really fight toget that extra experience? What we’re finding is that youhave much less reward for engaging in all those investments.That was the most distressing thing we found.”Creating the “Candidates”To generate fictitious job candidates, Bertrand and Mullainathanculled actual resumés that had been posted onWeb sites six months earlier from various job categories:sales, administrative support, clerical, and customer service.<strong>The</strong>y kept the structure, such as number <strong>of</strong> jobs andlevel <strong>of</strong> education. “But we replaced the Boston schools“<strong>The</strong> names are clearly triggering race,but the issue is that they might also betriggering social background.”with <strong>Chicago</strong> schools, and the Boston employers with<strong>Chicago</strong> employers <strong>of</strong> the same industry, size, and category,”Bertrand said.To choose names, they reviewed birth certificate datafrom Massachusetts from 1974 to 1979, noting whichnames were given most <strong>of</strong>ten to African Americans and towhites (all <strong>of</strong> whom would now be in their mid– to late20s). Student assistants headed to local train and bus stationswith lists <strong>of</strong> the names to check the public perception<strong>of</strong> which names were considered distinctively AfricanAmerican and distinctively white. Bertrand and Mullainathanthen omitted some names, including Maurice andJerome, which didn’t strike people as distinctively AfricanAmerican even though they were more <strong>of</strong>ten given toblack men.In creating fictitious addresses for the candidates,the researchers used every residential neighborhood in<strong>Chicago</strong> and Boston. <strong>The</strong>y also chose schools that wereintegrated. “We made sure not to put a white person in a100-percent-black high school. This was totally balanced,and that was essential to us because if you start puttingpeople with African American names in worse schools,then you’re back to, ‘Maybe that’s not discrimination. Iknow this person must have lower human capital, or alower education, than a white person,’” Bertrand said.Finally, Bertrand and Mullainathan also decided toboost qualifications on two <strong>of</strong> the four resumés theysent in response to each ad. “<strong>The</strong>re was an extra year<strong>of</strong> experience, some honors at school . . . small manipulationsthat would make the resumé look better butwould not make the person too qualified for the job,”Bertrand said.<strong>The</strong>y then randomly allocated two white-soundingnames and two African American–sounding names. “Thatwas the only thing that differed across the two groups.”Bertrand and Mullainathan found various forms <strong>of</strong>discrimination. “I think the most clearthing is that there’s name discrimination,”she said. “Andour inclination is to jump from namediscrimination to racial discrimination.”<strong>The</strong> researchers also found social discrimination.“Whoever you are, whateveryour resumé is, we find people wholive in ‘worse’ neighborhoods—meaninglow income, black, low education—those people havelower response rates. What was interesting was that thiswas not different for whites and blacks. Living on theSouth Side [<strong>of</strong> <strong>Chicago</strong>] hurts you whether you’re whiteor black.”Corporate CultureWhile most <strong>of</strong> the help-wanted ads did not list a companyname, the researchers were able to identify several <strong>of</strong> theemployers. But Bertrand said they were not interested inindividual company names, only statistics about the firm—the type <strong>of</strong> industry, the size, the company’s location. Com-16 <strong>Chicago</strong> GSB Summer/Fall 2003

What’s in a NamePolling the public, researchers determined that names theyused in their study—both first names and surnames—areperceived as “typically white” or “typically African American.”White FemaleBlack FemaleWhite MaleBlack MaleWhite Last NamesBlack Last NamesEmilyAishaNeilRasheedBakerJacksonAnneKeishaGe<strong>of</strong>freyTremayneKellyJonesJillTamikaBrettKareemMcCarthyRobinsonAllisonLakishaBrendanDarnellMurphyWashingtonSarahTanishaGregTyroneMurrayWilliamsMeredithLatoyaTodd<strong>Jamal</strong>O’BrienLaurieKenyaMatthewHakimRyanCarrieLatonyaJayLeroySullivanKristenEbonyBradJermaineWalshpanies located on <strong>Chicago</strong>’s South Side, which has a largeAfrican American population, might be more likely toemploy black human resources managers, which wouldaffect the callback rate slightly. “Employers located in aneighborhood that was slightly more African American wereslightly more likely to call blacks,” she said. But it neverreached a rate that would point to reverse discrimination. Infact, she said, “[An African American would] have to be in aneighborhood that’s about 97 percent black to get equaltreatment.”<strong>The</strong> study drew a strong response from the media,including mentions in the New York Times and <strong>Chicago</strong>Tribune and on CNN. Bertrand also received dozens<strong>of</strong> phone calls and e-mail messages from individualswho told her the study had struck a chord. “I got loads<strong>of</strong> e-mail from people with those African Americannames we used, explaining how difficult it’s been. Eventhe reverse—people who were African American withvery white names, telling me how terrible it is for themwhen they get called for an interview. <strong>The</strong>y get there andfeel like they’re being stared at, like, ‘Are you really EmilyWalker?’ I got a lot <strong>of</strong> e-mail from those people.”Bertrand also heard from one man with an Arabicname who said he got little response after sending outhis resumé. “He changed the name on his resumé, toneddown the qualifications a bit and sent it out again, andhe got plenty <strong>of</strong> responses,” she said. “This is just onedata point, but it’s interesting that the study resonatedwith lots <strong>of</strong> people’s personal experiences as well.”She and Mullainathan would have liked to includeHispanic, Asian, and Middle Eastern names in the study,but logistics prevented it. “I think it would have beengreat to do other ethnic groups. For instance, there aredifferent theories floating around Asians, with somepeople saying they perform better than whites. But wewould have had to double the size <strong>of</strong> the study, and itwould have been a really long process,” she said.Bertrand also received calls from people who trainhuman resources managers, wanting to see the study,as well as other researchers interested in applyingthe methodology to other work, like testing medicalstudents by putting white- and black-sounding nameson medical records.While the results <strong>of</strong> Bertrand and Mullainathan’sstudy illustrate how discrimination continues to affectthe corporate landscape, she cautions that it does notmean there has been no progress in race relations.“We don’t have a benchmark. I don’tknow what this would have looked like 20 or 30 yearsago.” SOUND ■ OFF!What do you think about Bertrand’s findings?For more on Bertrand’s E-mail us research, at editor@gsb.uchicago.edu.visit gsbwww.uchicago.edu/news/gsbchicago/facultylinks.html.Summer/Fall 2003 <strong>Chicago</strong> GSB17