Putting people first: Equality and Diversity Matters 2 - Think Local Act ...

Putting people first: Equality and Diversity Matters 2 - Think Local Act ...

Putting people first: Equality and Diversity Matters 2 - Think Local Act ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

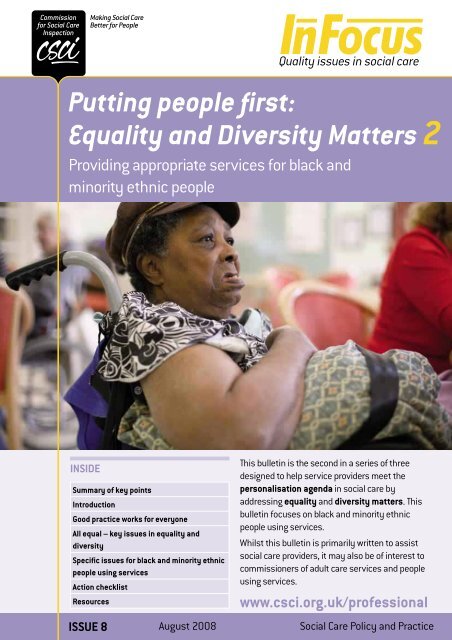

2 <strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 2About CSCIThe Commission for Social Care Inspection (CSCI) was set up in April 2004. Its main purposeis to provide a clear, independent assessment of the state of social care services in Engl<strong>and</strong>.CSCI combines inspection, review, performance <strong>and</strong> regulatory functions across the range ofadult social care services in the public <strong>and</strong> independent sectors.CSCI exists to promote improvement in the quality of social care <strong>and</strong> to ensure public moneyis being well spent. It works alongside councils <strong>and</strong> service providers, supporting <strong>and</strong>informing efforts to deliver better outcomes for <strong>people</strong> who need <strong>and</strong> rely on services toenhance their lives. CSCI aims to acknowledge good practice but will also use its interventionpowers where it finds unacceptable st<strong>and</strong>ards.Reader InformationDocument PurposeFor informationAuthorCommission for Social Care InspectionPublication Date August 2008Target AudienceDirectors of adults' social services, chief executives <strong>and</strong>councillors of councils with social services responsibilitiesin Engl<strong>and</strong>, social care providers, academics <strong>and</strong> socialcare stakeholders.Further copies fromcsci@accessplus.co.ukCopyright© 2008 Commission for Social Care Inspection (CSCI) Thispublication may be reproduced in whole or in part, freeof charge, in any format or medium provided that it is notused for commercial gain. This consent is subject to thematerial being reproduced accurately <strong>and</strong> on proviso that itis not used in a derogatory manner or misleading context.The material should be acknowledged as CSCI copyright,with the title <strong>and</strong> date of publication of the documentspecified.Internet addresswww.csci.org.uk/professionalPriceFREERef. No.CSCI-QSC-157-20000-AHS-092008CSCI-232

<strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 2 3ContentsQuality issues in social care ....................................4The <strong>Equality</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Diversity</strong> <strong>Matters</strong> series....................4How have we developed this bulletin? .........................4Summary of key points .............................................6Introduction ..............................................................81. What is this bulletin about? ...............................82. Important issues .................................................93. How well do social care services respond tothe needs of black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong>using services? .................................................13Good practice works for everyone ..........................174. Assessments <strong>and</strong> care plans that work forblack <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> .................... 175. Choice <strong>and</strong> control ............................................. 21Specific issues for black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic<strong>people</strong> using services.............................................3711. A home from home ............................................3712. Who supports us?..............................................4113. Underst<strong>and</strong>ing each other ................................4514. Connections .......................................................4715. Reaching out ......................................................5116. Checklists for action ..........................................5417. Useful resources ......................................... 5818. Appendix – relevant sections of the CareHome Regulations <strong>and</strong> Domiciliary CareAgencies Regulations ................................. 59All equal – key issues in equality <strong>and</strong> diversity ....246. Management <strong>and</strong> leadership ............................247. Staffing ................................................................268. Monitoring ethnicity ..........................................289. Tackling prejudice <strong>and</strong> discrimination............ 3010. Involving black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> whouse services .......................................................35Social Care Policy <strong>and</strong> Practice

4 <strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 2Quality issues in social carePromoting improvements in social care <strong>and</strong>stamping out bad practice for the benefit of the<strong>people</strong> who use care services are key functionsof the Commission for Social Care Inspection(CSCI). The Commission has a commitmentto promote equality <strong>and</strong> diversity in all that itdoes.The <strong>Equality</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Diversity</strong><strong>Matters</strong> seriesThis bulletin is the second in a series of threedesigned to help service providers meet the newpersonalisation agenda within <strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong><strong>first</strong> 1 by addressing equality <strong>and</strong> diversitymatters. This bulletin focuses on black <strong>and</strong>minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> using services. The otherbulletins cover equality for lesbian, gay, bisexual<strong>and</strong> transgender <strong>people</strong>, published in March2008, 2 <strong>and</strong> disability equality, due in December2008. We are producing these bulletins to: support service providers to ensure thatservices are personalised so they meet theneeds of a diverse range of <strong>people</strong> highlight <strong>and</strong> increase underst<strong>and</strong>ing of thekey issues for diverse groups of <strong>people</strong> usingservices share what we have learnt about goodpractice in equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters from1. Department of Health (2007) <strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong>: ashared vision <strong>and</strong> commitment to the transformationof adult social care. London: Department of Health2. Commission for Social Care Inspection (2008)<strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong>: <strong>Equality</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Diversity</strong> <strong>Matters</strong>1 – providing appropriate services for lesbian, gay <strong>and</strong>bisexual <strong>and</strong> transgender <strong>people</strong>. London: Commissionfor Social Care Inspectioninspecting services <strong>and</strong> from hearing from<strong>people</strong> who use services identify practical steps that can be taken byservice providers to improve the experiencesof <strong>people</strong> who use social care services. Whilst the series is primarily written to assist<strong>people</strong> providing social care services, someof the issues raised are also relevant tocommissioners seeking to ensure that theservices they commission meet the diverseneeds of their communities.How have we developed thisbulletin?We have used a number of sources of informationto write this bulletin, including: Examining the National Minimum St<strong>and</strong>ards(NMS) for care services to look at the keyissues relating to equality <strong>and</strong> diversity. Focus groups with black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic<strong>people</strong>, using a range of services includinghome care, adult placement schemes, carehomes <strong>and</strong> those receiving Direct Payments 3in lieu of services. Individual interviews with black <strong>and</strong> minorityethnic <strong>people</strong> using services, particularlyfocusing on <strong>people</strong> living in care homes. Theinterviews <strong>and</strong> focus groups included 63<strong>people</strong> who identified as African, Chinese,Caribbean, Indian, Pakistani, Irish, Polish <strong>and</strong><strong>people</strong> of dual heritage. We involved older3. Direct Payments are cash payments given to <strong>people</strong>by councils, so that they can purchase social careservices themselves instead of being provided withservices

<strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 2 5<strong>people</strong> <strong>and</strong> younger adults, including <strong>people</strong>with physical <strong>and</strong> sensory impairments,<strong>people</strong> with learning difficulties <strong>and</strong> <strong>people</strong>using mental health services. We included<strong>people</strong> who identified as Buddhist, Christian,Jewish, Muslim, Hindu <strong>and</strong> Sikh as well asthose who do not follow a faith.A representative sample of Annual QualityAssurance Assessment (AQAA) forms (400 intotal) completed by managers of home careagencies <strong>and</strong> care homes, reporting the workthey have carried out to make their servicesaccessible <strong>and</strong> appropriate for a diverse rangeof <strong>people</strong>.Discussion groups with service providers whoare leading the way in providing appropriateservices for black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong>.Social Care Policy <strong>and</strong> Practice

6 <strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 2Summary of key pointsThe key to achieving appropriate social careservices for black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong>is personalised support that addresses theneeds of the individual, rather than adaptingservices based on generalisations about culturalrequirements. Personalisation is at the core of the<strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> protocol, 4 which describes thevision <strong>and</strong> commitment for the transformation ofsocial care.Yet, personalised services cannot be achievedfor black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> by justresponding to individual needs as they arise.Services need to take a systematic approach toremoving barriers that may prevent black <strong>and</strong>minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> receiving appropriatesupport. These barriers include organisationalprocesses or assumptions <strong>and</strong> the behaviourof individual staff, which may amount to eitherintentional or unwitting discrimination.Black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> told us that theywant: accessible information about services leadingto options about which services they use control over decisions about their future services that recognise differences in <strong>people</strong>’scultures, without making assumptions support from staff with positive <strong>and</strong> respectfulattitudes towards them services that enable them to have contact with<strong>people</strong> that are important to them <strong>and</strong> to beconnected to communities to feel safe <strong>and</strong> be free from discrimination opportunities to give feedback <strong>and</strong> to improveservices.Despite race equality legislation being in place for30 years, the experience of black <strong>and</strong> minority4. Department of Health (2007) <strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong>: ashared vision <strong>and</strong> commitment to the transformationof adult social care. London: Department of Health

<strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 2 92. Important issuesDefinitionsThe use of various words <strong>and</strong> phrases in raceequality work has been the subject of muchdebate. Definitions of what constitutes an ‘ethnicgroup’ also change. The list below gives workingdefinitions for this bulletin; it is not possible togive definitions that are agreed universally.Black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic – we have used thisterm to include all groups that are not recordedunder the ‘white British’ ethnic group category,as it is not correct to assume that minority ethnicgroups are only defined by skin colour or race. Thisapproach is supported by the Office for NationalStatistics. Where we have referred to evidencefrom others that relates only to ‘non-white’minority ethnic groups, we have indicated this.Culture – encompasses the culture, artistic <strong>and</strong>intellectual accomplishments, religious beliefs<strong>and</strong> values of <strong>people</strong> who share the same ethnicorigin. 9Direct or intentional discrimination – treating<strong>people</strong> less favourably purely on the basis of theirethnic origin.Institutional racism – the collective failure ofan organisation to provide an appropriate <strong>and</strong>professional service to <strong>people</strong> because of theircolour, culture or ethnic origin. It can be seen ordetected in processes, attitudes <strong>and</strong> behaviourwhich amount to discrimination through unwittingprejudice, ignorance, thoughtlessness <strong>and</strong> raciststereotyping which disadvantage minority ethnic<strong>people</strong>. It persists because of the failure of theorganisation openly <strong>and</strong> adequately to recognise<strong>and</strong> address its existence <strong>and</strong> causes by policy,example <strong>and</strong> leadership. 10Refugee – someone whose asylum applicationhas been successful <strong>and</strong> who is allowed to stayin another country having proved they would facepersecution back home. 11Asylum seeker – a person who has left theircountry of origin <strong>and</strong> formally applied for asylumin another country but whose application has notyet been decided. 12<strong>Diversity</strong> within black <strong>and</strong> minority9 10 11 12ethnic communitiesBlack <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> usingservices are very diverse. There are the obviousdifferences in terms of ethnicity, for examplethe needs of African Caribbean <strong>people</strong> maybe different from the needs of those fromBangladeshi communities. There are particularissues for <strong>people</strong> from smaller or relatively newcommunities. Provision of specific services,or even basic requirements such as access tointerpreters, may be especially limited.However, it is important to look beyond ethnicityor culture alone; otherwise, there is a dangerof replacing a lack of cultural awareness withassumptions <strong>and</strong> stereotypes based on the idea9. Social Services Inspectorate (1998) They look aftertheir own, don’t they? Inspection of community careservices for black <strong>and</strong> ethnic minority older <strong>people</strong>.London: Department of Health10. Macpherson, W (1999) The Stephen Lawrence Inquiry:report of an inquiry by Sir William Macpherson ofCluny. London: the Stationery Office11. The Refugee Council website(www.refugeecouncil.org.uk)12. The Refugee Council websiteSocial Care Policy <strong>and</strong> Practice

10 <strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 2that <strong>people</strong> from the same cultural background allhave the same needs. People’s needs <strong>and</strong> desiresare based on a complex mix of experience,identity <strong>and</strong> preferences.Some studies have shown that the differencesbetween the experiences of men <strong>and</strong> womenfrom minority ethnic groups are sharper than thedifferences between minority ethnic groups. 13There are also differences in terms of age. Foreveryone, expectations of our roles <strong>and</strong> ambitionschange with age. For black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnicolder <strong>people</strong> <strong>and</strong> younger <strong>people</strong> using services,there may also be differences in their knowledgeof how ‘the system works’ <strong>and</strong> familiarity withlanguage, based on whether <strong>people</strong> have beenbrought up in the UK, which affects confidence inusing services.Black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> under 60 weretwice as likely to tell us that they had faceddiscrimination when using services or thatservices did not meet their needs, comparedto older <strong>people</strong>. This may be because youngerblack <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> have higherexpectations of services <strong>and</strong> more confidence tovoice concerns.“[I don’t] feel good about, you know, makingcomplaints or telling <strong>people</strong> what to do. Ithink you won’t be welcome if you do that”Older person living in care homeIf <strong>people</strong> have arrived to the UK as refugeesor asylum seekers, their needs may also bedifferent to those of other black <strong>and</strong> minorityethnic <strong>people</strong> using social care. For example,13. Chahal, K (2004) Experiencing ethnicity:discrimination <strong>and</strong> service provision. Joseph RowntreeFoundation: York

<strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 2 11older refugees may face a greater sense of lossabout their past life, trauma associated with pastexperiences <strong>and</strong> greater poverty, in addition toissues in common with other black <strong>and</strong> minorityolder <strong>people</strong> such as language barriers <strong>and</strong> theloss of social networks. 14A study by the Refugee Council also found thatdisabled asylum seekers had a high level ofunmet need, due to the different framework ofsupport for asylum seekers. 15Where <strong>people</strong> may be subject to discriminationon other grounds, being from a black or minorityethnic group may make discrimination morelikely. For example, black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnicyoung disabled <strong>people</strong> may face low expectationsin education due to a mix of race discrimination<strong>and</strong> disability discrimination. 16 The <strong>first</strong>bulletin in this series indicated that lesbian,gay or bisexual <strong>people</strong> from black <strong>and</strong> minorityethnic communities were more likely to faceprejudice from services on the grounds of sexualorientation than lesbian, gay or bisexual <strong>people</strong>with a white British background. 1714. Patel, B <strong>and</strong> Kelley, N (2007) The social care needsof refugees <strong>and</strong> asylum seekers: race equalitydiscussion paper 2. London: Social Care Institute forExcellence15. Patel, B <strong>and</strong> Kelley, N (2007), Ibid16. Bignall, T <strong>and</strong> Butt, J (2000) Between ambition <strong>and</strong>achievement. London: Joseph Rowntree Foundation<strong>and</strong> Bristol: Policy Press17. Commission for Social Care Inspection (2008)<strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong>: <strong>Equality</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Diversity</strong> <strong>Matters</strong>1 – providing appropriate services for lesbian, gay <strong>and</strong>bisexual <strong>and</strong> transgender <strong>people</strong>. London: Commissionfor Social Care InspectionFor this reason, it is important to read the otherbulletins in the series to underst<strong>and</strong> the way thateveryone using services may experience a varietyof issues relating to equality <strong>and</strong> diversity.What black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong>using services wantThere are obviously dangers in generalising aboutwhat ‘black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> want’. Thestarting point in considering what someone usingservices needs <strong>and</strong> how these needs are metshould always be finding this out from the personhimself or herself.The needs of black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong>using social care are often the same as thoseof other <strong>people</strong>; however, the needs may needmeeting in different ways. 18 Black <strong>and</strong> minorityethnic <strong>people</strong> have shared experiences of racism<strong>and</strong> disadvantage <strong>and</strong>, for many older <strong>people</strong>,shared experiences of migration, which influencetheir interaction with social care services. 19 Anunderst<strong>and</strong>ing of these common factors helps toput individual needs into context <strong>and</strong> to promoteanti-discriminatory practice.Black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> have a rightto expect services that are going to underst<strong>and</strong><strong>and</strong> respond to their individual needs <strong>and</strong> not tosubject them to race discrimination. The <strong>people</strong>taking part in interviews <strong>and</strong> focus groups saidthat they want:18. Social Services Inspectorate (1998), Ibid19. Butt, J, Box, L <strong>and</strong> Cook, SL (1999) Respect – learningmaterials for social care staff working with black <strong>and</strong>minority ethnic older <strong>people</strong>. London: Race <strong>Equality</strong> UnitSocial Care Policy <strong>and</strong> Practice

12 <strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 2Accessible information to enable them tomake choices about services, for exampleDirect Payments, <strong>and</strong> to know their rights,including how to challenge discrimination.Participation in decisions about their future,particularly in assessments <strong>and</strong> reviewing careplans. People said that meant that adequatetime should be given for meeting with theperson, timely <strong>and</strong> clear communicationbetween staff <strong>and</strong> the person using the service,<strong>and</strong> advocacy available if needed.Choice <strong>and</strong> control in the services that theyuse, including good information <strong>and</strong> support ifthey choose Direct Payments <strong>and</strong> the option ofusing specific services for or run by black <strong>and</strong>minority ethnic communities.Their cultures to be recognised, whilstavoiding assumptions based on stereotypes.Services should underst<strong>and</strong> the importance ofproviding culturally appropriate support <strong>and</strong>have knowledge of how this can be done, aswell as engaging with individuals to find outhow they want their support to be provided.To make choices about how they engage withothers including opportunities to take an activerole in their families <strong>and</strong> in their communities<strong>and</strong> to develop friendships. These choices areimportant in reducing isolation, which can havea detrimental impact on well-being.Support from staff that have positive <strong>and</strong>respectful attitudes towards them. Someblack <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> want stafffrom the same community, particularly ifEnglish is not their main language. Someprefer to choose the gender of staff or staffwho they think communicate well <strong>and</strong> havepositive attitudes. Others stressed the needfor staff training to cover race equality issues.To feel safe <strong>and</strong> be free from discrimination,whether this is obvious prejudice or moresubtle discrimination. Where black <strong>and</strong>minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> do experiencediscrimination, they want opportunities toraise concerns easily <strong>and</strong> providers to respondin ways that are supportive to the personmaking the complaintAn opportunity to improve services – forthemselves as individuals <strong>and</strong> collectively.People particularly wanted to meet as groupsof black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> to shareexperiences for peer support <strong>and</strong> to changeservices for the better, including challenginginstitutional racism.

<strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 2 133. How well do social careservices respond to the needsof black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic<strong>people</strong> using services? 94% of services reported that they werecarrying out some general work aroundequality <strong>and</strong> diversity, such as advisingstaff of equality policies or carrying out stafftraining. Some of this activity will undoubtedlyinclude equality work around race equality. 37% of providers gave examples of the specificequality work they have carried out aroundrace equality (this compares to 33% who gavean example relating to disability equality <strong>and</strong>9% who gave an example relating to equalityfor lesbian, gay or bisexual <strong>people</strong>): 24% of services said that they had carriedout work to make their services moreculturally appropriate, for example inthe food that they provide or activitiesorganised. This was the most common typeof activity for care homes. 8% of services said that they had workedon language support for black <strong>and</strong> minorityethnic <strong>people</strong>, for example throughproviding interpreters or translating writtenmaterials. 8% of services said that they had carriedout work on staffing, such as allowing<strong>people</strong> using services to choose supportfrom staff from their own culture. 7% of services said they had carried outwork to enable black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic<strong>people</strong> using services to maintain contactswith their communities. 6% of services said they had carried outwork to positively recruit more black <strong>and</strong>minority ethnic staff. This was the mostcommon type of activity for home careagencies, with 16% of providers havingcarried out this work.The number of providers who said they hadworked specifically on race equality wasSocial Care Policy <strong>and</strong> Practice

16 <strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 2<strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> may also haveparticular anxieties about using a service,fearing it may not meet their needs or thatthey will face discrimination. Providers canincrease take-up from black <strong>and</strong> minorityethnic communities by targeted publicity <strong>and</strong>outreach activities as well as making servicesmore appropriate for black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic<strong>people</strong>.Race equality legislationThe Race Relations <strong>Act</strong> 1976The <strong>Act</strong> defines three types of unlawful racialdiscrimination: direct discrimination, indirectdiscrimination, <strong>and</strong> victimisation. Direct discrimination takes place if a personis treated less favourably than someone froma different racial group. Segregating <strong>people</strong>because of their racial origins is also unlawful. Indirect discrimination takes place when<strong>people</strong> from a particular racial group cannotmeet a rule, condition or practice that shouldapply equally to everyone. If the rule puts<strong>people</strong> from that racial group at a disadvantage,<strong>and</strong> if the rule cannot be justified, this will beindirectly discriminatory. For example, if a localmedical practice refuses to accept tenants froma nearby housing estate as patients, <strong>and</strong> mostof the tenants on the estate are of Bangladeshiorigin, this will be indirectly discriminatory,unless the practice can give good reasons forits policy.The law also protects <strong>people</strong> from beingvictimised for bringing a complaint of racialdiscrimination, or for backing someone else’scomplaint. For example, if a white employeewho has given evidence in her Asian colleague’sracial discrimination case against the companyis penalised in any way, she may be ableto bring a case of victimisation against heremployer. 26The Race Relations (Amendment) <strong>Act</strong> 2000Most public authorities now have a statutorygeneral duty under the amended Race Relations<strong>Act</strong> to promote race equality. This means theymust do whatever they can to: eliminate unlawful racial discriminationpromote equal opportunities, <strong>and</strong>encourage good race relations.Most public authorities also have other specificduties under the <strong>Act</strong>. These cover the way theyprovide services <strong>and</strong> employ <strong>people</strong>, as well ashow they make policy. 27When private or voluntary sector providers enterinto a contract or partnership with a council, <strong>and</strong>the race equality duty applies to that work, thecouncil must ensure that the provider complieswith the duty. Providers therefore will need tounderst<strong>and</strong> the legal duties that councils haveunder this <strong>Act</strong> <strong>and</strong> the practical guidance availableon how to meet those duties.26 2726. CRE (2003) The law, the duty <strong>and</strong> you: the RaceRelations <strong>Act</strong> <strong>and</strong> the duty to promote race equality –a guide for public employees. London: Commission forRacial <strong>Equality</strong>27. CRE (2002) The duty to promote race equality – aguide for public authorities. London: Commission forRacial <strong>Equality</strong>

<strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 2 17Good practice works for everyoneGood practice in assessment, person-centredplanning <strong>and</strong> self-directed services forms animportant foundation for ensuring personalisedservices, appropriate for a wide range of <strong>people</strong>.Current social care reforms, particularly thedrive to increase the personalisation of adultservices, as in <strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> 28 shouldenable more <strong>people</strong> to benefit from theseapproaches in the future.<strong>and</strong> where there is an important need to build uptrust with the person using the service. 29Service providers need to tackle the specificbarriers to race equality in admission procedures,assessment <strong>and</strong> care planning processes. Only6% of service providers gave specific examples of4. Assessments <strong>and</strong> careplans that work for black <strong>and</strong>minority ethnic <strong>people</strong>Good assessments <strong>and</strong> care plans directed bythe person are key to individualised services,yet less than half the <strong>people</strong> that we spoke tofelt that their needs as a black or minority ethnicperson were adequately considered at their lastassessment.Some black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> criticisedthe length of the assessment process orinfrequency of review.“My most recent assessment carried outin November, although culture etc wasconsidered, I am still waiting for the results inMarch”Person with a learning disabilityThese delays have greater significance for black<strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> who have previouslyfaced race discrimination when using services28. Department of Health (2007) <strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong>: ashared vision <strong>and</strong> commitment to the transformationof adult social care. London: Department of Health29. Butt, J, Box, L <strong>and</strong> Cook, SL (1999), IbidSocial Care Policy <strong>and</strong> Practice

18 <strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 2work to promote race equality or consider culturein assessment <strong>and</strong> care planning, though otherslisted ‘culture’ or ‘ethnicity’ as a factor that theywould consider in assessment or care planning.These barriers include:Communication barriers“I was given enough information but not in mylanguage”Focus group participantAs well as obvious language differences, olderCaribbean <strong>people</strong> who use patois or <strong>people</strong>using English as a second language may not beconfident that they underst<strong>and</strong> or have beenunderstood. These difficulties may increase ifsomeone has had a stroke or has dementia. 30Information barriersBlack <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> often faceparticular barriers to obtaining information aboutsocial care services (see section 14) whichmay affect how they advocate for themselves inassessment <strong>and</strong> care planning.As someone moving into residential care, with nofamily nearby, commented:“I have been here once before <strong>and</strong> I took aliking to it <strong>and</strong> then I suppose when theymentioned this place I said yes, I’d like to goback there. But what I suppose I didn’t realiseor take into consideration that I was going tobe here for a long time or for good.... As I say,it’s just that I pay the £500 a week, whichI think is a bit expensive because if you’regoing to be [somewhere] for a long time themoney that I have is going to go down, there’sno doubt about it”Care staff may also be poorly informed due toassumptions about black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic<strong>people</strong> in general, stereotypes about particularcultures or lack of knowledge about appropriateresources or services.Differences in valuesWe all have values; we may not even be awarethat these are affecting our underst<strong>and</strong>ing orjudgement of someone else’s situation.“[In assessment] there is the potential for anethnocentric model becoming dominant... thismeans that the values of one ethnic groupbegin to be seen as natural or normal, <strong>and</strong> ourassessment <strong>and</strong> actions are influenced by this” 31Providing a checklist of values for differentcultures is inappropriate, as it could lead tostereotyping.30. Butt, J, Box, L <strong>and</strong> Cook, SL (1999), Ibid31. Butt, J, Box, L <strong>and</strong> Cook, SL (1999), Ibid

<strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 2 19“The attention given to cultural difference byprofessionals can sometimes compromiseholistic needs assessment <strong>and</strong> care, leadingto the partial <strong>and</strong> inaccurate assessment ofneeds” 32Assessors need to avoid stereotyping orseeing one ethnic group’s lifestyle as the norm.Assessments may focus on ‘difficulties <strong>and</strong>risk’ rather than considering the strengthsof the person or meeting outcomes, if thereare communication barriers or a lack ofunderst<strong>and</strong>ing due to differences in values. 33“I had an assessment from the hospital. I wasput in residential care but I didn’t like that soI got home care instead. It actually costs lessfor the home care <strong>and</strong> I’m happy to be in myown home. I don’t think my culture was takeninto account. It’s just a production line – it’sonly my healthcare needs that they worryabout not me as a person”Older personUnderst<strong>and</strong>ing the experience of racism <strong>and</strong>disadvantageMany black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> haveexperienced racism, which can affect <strong>people</strong>’sself-esteem <strong>and</strong> confidence <strong>and</strong> make themreluctant to approach services or wary of theassessment process.The impact of racism <strong>and</strong> disadvantage iswider than just previous experience of socialcare services. People from Black African orCaribbean, South Asian or Irish backgroundsare likely to experience greater rates of illness<strong>and</strong> impairment than white <strong>people</strong> from Britishbackgrounds. Black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnicdisabled <strong>people</strong> are likely to have lower incomes<strong>and</strong> worse housing than their white Britishcounterparts. 34 Refugees <strong>and</strong> asylum seekersmay have experienced traumatic events suchas detention, torture <strong>and</strong>/or the death of lovedones, <strong>and</strong> once in the UK often face poverty <strong>and</strong>acute anxiety about their legal status as well asisolation, language barriers <strong>and</strong> a lack of socialnetworks. 35This will affect both <strong>people</strong>’s social care needs<strong>and</strong> the range of choices available to meet theseneeds.Though some black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong>have prospered, assessors need to be sensitiveto the potential impact of these wider factors interms of <strong>people</strong> being able to exercise choice <strong>and</strong>control.32. Gunaratnam, Y (2006) Ethnicity, older <strong>people</strong> <strong>and</strong>palliative care. London: National Council for PalliativeCare <strong>and</strong> Policy Research Institute on Ageing <strong>and</strong>Ethnicity33. Butt, J, Box, L <strong>and</strong> Cook, SL (1999), Ibid34. Butt, J (2006), Ibid35. Patel, B <strong>and</strong> Kelley, N (2007), IbidSocial Care Policy <strong>and</strong> Practice

20 <strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 2Good practice pointers – assessment <strong>and</strong>care planningEnsure staff can confidently balanceavoiding stereotypes with a recognition ofcultural needs, including being alert to wheresomeone’s situation may be more unusualwithin their culture or where there areadditional issues due to refugee or asylumstatus.Make sure that <strong>people</strong> have accessibleinformation, in advance of the assessmentor admission, about the process <strong>and</strong> serviceoptions that is clear about what the service canprovide (for example which tasks home carestaff will carry out).Develop staff knowledge about specific supportfor black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> that couldbe part of a care plan.Enable <strong>people</strong> to have access to appropriateadvocates or interpreters <strong>and</strong> find out who elsethe person wants at any meeting, for examplefamily members, but do not use relatives orfriends as interpreters.Allow enough time to establish goodcommunication in face-to-face meetings,especially if there are language or culturaldifferences.Ask <strong>people</strong> open questions to help reinforce<strong>people</strong>’s cultural heritage, <strong>and</strong> enable <strong>people</strong> toexpress any particular concerns about usingservices, for example:who is it important that you stay in contactwith?what support do you need to keep up theserelationships?how do you like to spend your time?what support do you need to keep up theseactivities?what is important to you about any supportthat you have?do you have any particular worries about thefuture that you would like to talk about?Regularly update <strong>people</strong> about the progress ofthe care plan following assessment includingany changes to staff involved.Develop the skills of staff from a range ofcommunities to lead on assessment <strong>and</strong> careplanning. Do not use multilingual staff purelyas interpreters as these are different roles <strong>and</strong>avoid using black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic staff as‘cultural experts’.Make sure care plans have a summary ofthe person’s expectations of how care will beprovided, including any cultural requirements,that is accessible to all staff.Enable <strong>people</strong> to have a ‘trial period’ usinga service <strong>and</strong> review care plans soon aftersomeone starts the service, by asking theperson whether their needs are being met inthe best way.

<strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 2 215. Choice <strong>and</strong> controlPeople having a choice <strong>and</strong> taking control of theirsupport is at the heart of the transformation ofsocial care. The black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong>that we spoke to had mixed views on how wellthey had been able to exercise choice in theservices that they used.“No choice was given, nothing was available”Person with a learning disability“I am well supported in all the choices, I havea chance to work”Disabled person, using home careAccessible information, in an appropriate form<strong>and</strong> language, is an essential requirement toenable black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> to makeinformed choices.Getting the service right <strong>first</strong> timeSeveral of the <strong>people</strong> we spoke to had startedto use services in an emergency, for exampleon hospital discharge. These <strong>people</strong> sometimeshad little choice <strong>and</strong> were initially placed ininappropriate services but were then able to movewhen their care plan was reviewed, to servicesspecifically for their community.“There was no synagogue there, so he feltvery isolated. So that’s why they brought himhere, because they had synagogue here... hisreligious needs are fulfilled here, that’s whyhe got in here <strong>and</strong> as well Polish language,there’s a lot of Polish staff here”Carer of older personOthers moved from one generic service toanother, because they had faced racism fromstaff <strong>and</strong> from others using the service. Gettingthe services ‘right <strong>first</strong> time’ would obviously bepreferable.Generic or specific services?Black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> want tohave a choice of services. Many <strong>people</strong> preferservices provided by the black <strong>and</strong> minorityethnic voluntary <strong>and</strong> community sector, not onlybecause they are culturally specific <strong>and</strong> enablecommunication in the person’s own languagebut because <strong>people</strong> feel that they will be safe<strong>and</strong> understood. Many black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnicorganisations also provide advocacy. 36“The service does take care of my culturalneeds, it is very nice here - everyone is reallygood. There is no need to change anything; Iwould go to the manager if there was. All myneeds are met with regard to food”Older person in a care home for the South AsiancommunityHowever, black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> shouldbe able to choose specific services as a positiveoption, not because mainstream services areunable to meet their needs.36. Chahal, K (2004), IbidSocial Care Policy <strong>and</strong> Practice

22 <strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 2Using Direct Payments <strong>and</strong> IndividualBudgetsThe use of Direct Payments or Individual Budgetsshould increase <strong>people</strong>’s control over the servicesthat they use. A general issue raised, however,was the use by some <strong>people</strong>, particularly older<strong>people</strong>, of Direct Payments to employ youngerrelatives, such as gr<strong>and</strong>children, as personalassistants. Whilst this could meet their needswell, there could also be potential conflictsof interest <strong>and</strong> questions about whetherpaying relatives might reduce the options forindependent living, if the family becomes relianton the income from these payments. Peoplealso raised a number of issues about makingDirect Payments work for black <strong>and</strong> minorityethnic communities that are borne out by otherstudies: 37 Many black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> stillhave little knowledge about Direct Payments;these were not raised as an option in theirassessments. People needed more advocacy <strong>and</strong> support toorganise their care this way. There is a shortage of <strong>people</strong> to work aspersonal assistants. Some black <strong>and</strong> minorityethnic <strong>people</strong> had difficulty in obtainingculturally appropriate personal assistants.37. For example, Stuart, O (2006) Will community-basedsupport services make direct payments a viableoption for black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic service users<strong>and</strong> carers? Stakeholder participation race equalitydiscussion paper 1. London: Social Care Institute ofexcellence

<strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 2 23 People found it difficult to get information onhome care agencies that provided appropriatestaff, as an alternative to employing personalassistants or to cover times when personalassistants were not available because ofholidays or sickness.The <strong>first</strong> bulletin in this series raised factors thatwere valued by lesbian, gay <strong>and</strong> bisexual <strong>people</strong>using Direct Payments that are relevant to othergroups facing prejudice: choice <strong>and</strong> consistency of worker flexibility over times <strong>and</strong> tasks whichenable <strong>people</strong> to maintain contact with theircommunities control in deciding what to do if a worker isdiscriminatory. 38Choice <strong>and</strong> control – good practicepointersProvide accessible information on care <strong>and</strong>support options, including Direct Payments,that addresses the concerns of black <strong>and</strong>minority ethnic <strong>people</strong>.Ensure <strong>people</strong> have appropriate advocacy toexercise choice.Offer any specific services for black <strong>and</strong>minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> as an option but not theonly choice.Home care recruitment agencies shouldpublicise their service, in accessible formats,to black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> consideringDirect Payments <strong>and</strong> should be able to answerquestions such as the language skills ofavailable workers.Give <strong>people</strong> a choice about which staff workwith them (see section 12).Involve <strong>people</strong> using services in staffrecruitment, including assessing staff attitudeson equality issues.Increase flexibility of service times <strong>and</strong> tasksto help <strong>people</strong> maintain contact with theircommunities <strong>and</strong> meet their cultural <strong>and</strong>religious needs38. Commission for Social Care Inspection (2008)<strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong>: <strong>Equality</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Diversity</strong> <strong>Matters</strong>1 – providing appropriate services for lesbian, gay <strong>and</strong>bisexual <strong>and</strong> transgender <strong>people</strong>. London: Commissionfor Social Care InspectionSocial Care Policy <strong>and</strong> Practice

24 <strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 2All equal – key issues in equality <strong>and</strong>diversity6. Management <strong>and</strong> leadership“Research has shown that organisationsthat are successful in this area of diversity[race equality] are in that position because ofeffective leadership” 39Managers have a crucial role in taking action onrace equality; to improve services for <strong>people</strong>,remove institutional racism, set the ethos of theservice <strong>and</strong> to give staff a clear ‘steer’.Many managers are developing specific supportfor black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic staff, workingwith black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic organisations todevelop services <strong>and</strong> using local information tomap future needs for the service. However, this isnot always as part of an overall equality strategy.The Race Relations (Amendment) <strong>Act</strong> 2000 placesa duty on public sector providers to promoterace equality, as well as some specific duties inrelation to service provision <strong>and</strong> employment.Voluntary or private providers with councilcontracts also need to comply with these duties.Guidance to the <strong>Act</strong> provides useful informationon taking a structured approach to race equalitythrough developing an action plan to implementa race equality strategy, as well as other stepssuch as consulting with black <strong>and</strong> minority ethniccommunities. 4039. Race <strong>Equality</strong> Unit (2004) Race equality throughleadership in social care. London: the Association ofDirectors of Social Services, the Social Care Institutefor Excellence <strong>and</strong> the Commission for Social CareInspection,40. Commission for Racial <strong>Equality</strong> (2002) The duty topromote race equality: a guide for public authoritiesLondon: the Commission for Racial <strong>Equality</strong>

<strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 2 25Management <strong>and</strong> leadership – goodpractice pointersInvolve black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong>using services, staff <strong>and</strong> <strong>people</strong> from outsidethe organisation to develop a race equalitystrategy.Link this to your business plan <strong>and</strong> allocateappropriate resources.Use the guidance available for the duties topromote race equality under the Race Relations(Amendment) <strong>Act</strong> 2000.Discuss race equality as a regular item atmanagement meetings <strong>and</strong> develop managerswho are committed <strong>and</strong> confident in dealingwith race equality issues.Cascade race equality objectives into individualperformance plans.Support <strong>and</strong> consult with black workers’ groups.Openly report progress on race equalityobjectives <strong>and</strong> publicise consultations <strong>and</strong> theirresulting actions.Make race equality an explicit part of all qualityassurance processes <strong>and</strong> development work.Identify <strong>and</strong> address both direct <strong>and</strong> indirectracism (see section 9).Assess the effect of all your policies on black<strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> <strong>and</strong> other groupswho may face discrimination or disadvantage.Refer to race equality in communications suchas internal newsletters, management <strong>and</strong> teambriefings <strong>and</strong> external publicity.Work with your local council to map/auditcommunity groups <strong>and</strong> community needs <strong>and</strong>develop new services in response to identifiedneed.Good practice example – Anchor TrustAnchor Trust operates a number of businesses,including care services. In 2006 Anchorcommissioned a corporate review to confirm thatpractices with respect to race equality were fit forpurpose.Each business unit within Anchor carried out a selfassessmentevaluation of their current practicesagainst a list of key criteria relating to race equality.The self-assessment was a ‘gap analysis’ whichhighlighted any areas where current practices couldbe extended <strong>and</strong> developed.This method was informed by an assessmentframework from the Commission for Racial<strong>Equality</strong> <strong>and</strong> so helped Anchor to promoterace equality, as laid out in the Race Relations(Amendment) <strong>Act</strong>.The review enabled good practices to be captured<strong>and</strong> shared, <strong>and</strong> the assessments led to specificaction plans that detailed activities to develop raceequality themes.“The review provided an opportunity to clarify toboth staff <strong>and</strong> customers that Anchor regardsrace equality issues of high importance. A keyoutput of the project was the development of anupdated corporate diversity statement, whichclarifies expectations of behaviours with respectto race equality. By increasing awareness in ourworkforce, our customers can expect high qualityservices from staff who are informed on the keyrace equality issues.”The review process will be revisited at appropriateintervals to ensure that momentum is maintained.Sharing good practice on race equality issues willalso remain to be a feature.Anchor is linking this with work on other diversitytopics, such as disability equality, to ensure thatregular reviews become ingrained into workingpractices.Social Care Policy <strong>and</strong> Practice

26 <strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 27. StaffingTwo-thirds of the black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic<strong>people</strong> using services agreed with the statementthat suitable staff supported them; older <strong>people</strong>tended to agree with this more than younger<strong>people</strong>.<strong>Equality</strong> is everyone’s responsibilityRace equality is the responsibility of everyonedelivering services. Frontline staff shouldbecome:“Confident <strong>and</strong> competent workers whocommunicate effectively, use theirknowledge in a non-stereotypical manner <strong>and</strong>demonstrate flexibility in their approach. Theywill have the resources to draw on <strong>and</strong> haveaccess to managers who are knowledgeableabout diversity <strong>and</strong> are competentsupervisors” 41Learning <strong>and</strong> developmentMore staff training was a frequent request whenwe spoke to black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong>,particularly those using home care. The surveyof service providers indicated that 55% hadensured that their staff had training on equality<strong>and</strong> diversity issues, which is likely to includetraining on race equality. Only 4% of providersmentioned training on race equality or diversityissues specifically relating to ethnicity. Thereis no one ‘best method’ for delivering training41. Butt, J (2006), Ibidthat addresses race equality. 42 Learning is acontinuous process <strong>and</strong> it is therefore importantthat any training is reinforced through, forexample, team meetings, staff supervisionsessions <strong>and</strong> observation of practice.Role of black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic staffThe role of black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic workers indelivering services that meet the needs of <strong>people</strong>from their communities is the subject of muchdebate.Having a diverse workforce will undoubtedlybring additional experiences <strong>and</strong> skills into aservice but there are dangers in assuming thatthe presence of black or minority ethnic staff will,in itself, tackle race discrimination. Often black orminority ethnic staff are not in senior positions tomake change.Using black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic staff as ‘culturalexperts’ can shift the emphasis from tacklingracism to looking at different cultures, whichleaves institutional racism unchallenged. This canalso lead to generalisations that inadvertentlyreinforce stereotypes because it is difficultfor anyone to be an ‘expert’ on all aspects oftheir own culture. This approach can impedethe development of black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnicstaff; the worker’s other skills may not beacknowledged <strong>and</strong> they may have difficultiesmoving beyond specialist roles. 4342. Butt, J (2006), ibid43. Harris, V <strong>and</strong> Dutt, R (2004), Ibid

<strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 2 27Supporting black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnicstaffBlack <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic staff in social caredo play a positive role in the provision of moreappropriate services to black <strong>and</strong> minority ethniccommunities <strong>and</strong> to the improvement of practicewith all <strong>people</strong> who use services. However, theymay face a lack of development opportunities orcareer progression, conflict as a result of bringinga different perspective, racial harassment orviolence, <strong>and</strong> torn loyalties if they are caughtbetween the expectations of black <strong>and</strong> minorityethnic communities <strong>and</strong> the agency that employsthem. 44 Management strategies to retain <strong>and</strong>develop black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic staff need toaddress these experiences.Enabling black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> usinga service to have choice about the staff thatsupport them is covered in section 12.Staffing – good practice pointersAssess attitudes of potential staff to a range ofequality issues, including race equality, as partof the recruitment <strong>and</strong> selection process.Assess training needs on equality regularly <strong>and</strong>ensure all staff receive training which coversrace equality on an ongoing basis, for examplethrough self-directed learning. Considerinvolving black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong>using services in delivering training.Ensure regular <strong>and</strong> consistent messages aboutrace equality are given to staff by managers,<strong>and</strong> there are opportunities for staff to developtheir practice through staff supervision <strong>and</strong>team meetings.All staff should be expected to treat black<strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> fairly <strong>and</strong> withoutprejudice. If they do not, action should be taken.Retention of black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic staffshould be considered before recruitment;review equality <strong>and</strong> harassment policies, careerprogression, <strong>and</strong> staff support <strong>and</strong> supervisionto see how they are working for black <strong>and</strong>minority ethnic staff.Develop ways to gain the views of black <strong>and</strong>minority ethnic staff, including anonymousfeedback, for example through questionnaires<strong>and</strong> exit interviews.Consider establishing a black <strong>and</strong> minorityethnic staff forum, <strong>and</strong> be clear whether it is forpeer support, consultation with management orboth.44. Harris, V <strong>and</strong> Dutt, R (2004), IbidSocial Care Policy <strong>and</strong> Practice

28 <strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 28. Monitoring ethnicity“Service providers can only tell if they aremaking progress in making their servicesavailable to all sections of the population byethnic monitoring <strong>and</strong> by seeking the views of<strong>people</strong> from minority ethnic communities” 45Monitoring ethnicity in service delivery is betterestablished than monitoring other equality areas,such as sexual orientation or faith, but needsto be carried out in a sensitive way. Serviceswill need to establish the best ways to collectmonitoring information, ensure that staff aretrained on how to collect information <strong>and</strong>, mostimportantly, decide how the data will be used toimprove the service.As well as ethnic monitoring of service use, forexample of referrals <strong>and</strong> numbers of <strong>people</strong> usingthe service, it is important to incorporate ethnicmonitoring into quality assurance processes,such as surveys of <strong>people</strong> using services. Thisenables the provider to consider questions suchas: Do we underst<strong>and</strong> the diverse needs of black<strong>and</strong> minority ethnic communities? Do our services meet the diverse needs<strong>and</strong> aspirations of black <strong>and</strong> minority ethniccommunities? Do we provide an appropriate <strong>and</strong> professionalservice to black <strong>and</strong> minority ethniccommunities? Do we achieve equally high outcomes for allethnic groups in all our various activities? 46The Department of Health has produced aPractical guide to ethnic monitoring in the NHS<strong>and</strong> social care 47 for public sector organisations,which may also be useful for voluntary <strong>and</strong>independent sector providers.Ethnic monitoring in services– goodpractice pointersDecide on how you will use ethnic monitoring,for example to improve take-up of services byblack <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong>; then whichprocesses require monitoring, for examplereferrals, admissions, quality assurance.Ensure senior managers explain to staffwhy monitoring is important <strong>and</strong> give stafftraining or guidance on their role in monitoring,particularly if questions are going to be askedverbally.Make the purpose of monitoring clear to<strong>people</strong> completing the form or being asked thequestion.Ask everyone the ethnic monitoring question– self-classification is a fundamental principle.Where this is not possible because the personusing the service is unable to underst<strong>and</strong> thequestion, ask their closest relative or friend.Obtain consent – if someone does not want toanswer any monitoring question, that shouldbe respected.45. Chahal, K (2004), Ibid46. Chahal, K (2004), Ibid47. Department of Health (2005) Practical guide toethnic monitoring in the NHS <strong>and</strong> social care. London:Department of Health

<strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 2 29Make confidentiality clear – tell <strong>people</strong> who willsee the forms <strong>and</strong> ensure that no individual canbe identified from any reporting, for examplereporting back at an organisational level ratherthan a service level.Use the 2001 Census codes for ethnicmonitoring as this is a national st<strong>and</strong>ard butanalyse the ‘other’ category carefully to pick upissues for smaller communities.Monitoring ethnicity should be carried outalongside other monitoring questions, forexample regarding age, gender, sexualorientation <strong>and</strong> disability. Monitoring religion<strong>and</strong> belief should be a separate question toethnic monitoring.Report back to <strong>people</strong> to show how monitoringhas improved services.Social Care Policy <strong>and</strong> Practice

30 <strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 29. Tackling prejudice <strong>and</strong>discriminationRace discrimination manifests itself in manydifferent ways. Service providers need to beaware of <strong>and</strong> sensitive to these in order to tacklediscrimination effectively.Of the black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> that wespoke to, 23% said that they had experiencedprejudice or discrimination whilst using services.Only 13% of the older <strong>people</strong> felt that they hadfaced discrimination compared to 53% of the<strong>people</strong> under 65, with a further 18% of younger<strong>people</strong> not sure if they had faced prejudicecompared to 9% of older <strong>people</strong> who wereuncertain.We cannot conclude that there is morediscrimination in services for younger <strong>people</strong>because there may be various reasons forthis difference, including under-reporting ofdiscrimination by older <strong>people</strong>. These issues areexplored further in this section.Direct discriminationPeople using social care services can face directracism from individual members of staff, such asverbal abuse, racially motivated physical abuse orintentionally poor care, such as being ignored ordeliberately excluded.Some black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> that wespoke to had experienced direct discriminationfrom staff:“Sometimes they [some staff] call me names”Older person“I was more, like, manh<strong>and</strong>led when otherswere more, like, talked to <strong>and</strong> guided, youknow, to a room”Person using mental health servicesThere needs to be a zero tolerance of intentionalracism in order to both protect individual black<strong>and</strong> minority <strong>people</strong> using services from abuse<strong>and</strong> send a clear message to all staff that it isunacceptable. Discriminatory abuse is one of thesix types of abuse identified in the Department ofHealth No secrets guidance; 48 reports of racismmay need to be h<strong>and</strong>led under safeguarding(adult protection) procedures. Some directdiscrimination may also be a criminal offence.In order to tackle direct discrimination, providersmust not rely on <strong>people</strong> using services reportingincidents; they need to encourage other staff touse whistle-blowing procedures <strong>and</strong> to ensurethat supervisory staff observe day-to-daypractice.48. Department of Health (2000) No Secrets: guidance ondeveloping <strong>and</strong> implementing multi-agency policies<strong>and</strong> procedures to protect vulnerable adults fromabuse. London: Department of Health

<strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 2 31Indirect discriminationBlack <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> using servicesmay also experience indirect discrimination orinstitutional racism. 49“Most discrimination <strong>and</strong> racism is subtle, forexample I do not receive much information inmy own language”Focus group participant“I have faced both [race discrimination<strong>and</strong> disability discrimination]. A lot ofassumptions are made at assessment”Disabled personStaff with supervisory responsibility mayneed support to identify <strong>and</strong> deal with poorpractice that may be caused by unconsciousdiscrimination.Discrimination from other <strong>people</strong> usingservicesPeople need to be free from harassment ordiscrimination by others using the service, inorder to be safe.“I have experienced racism in the servicesI use... yes I experience racism from fellowservice users, the staff tell me to take nonotice”Older personSometimes this is more difficult to address th<strong>and</strong>iscrimination from staff, for example if theperpetrator is less aware of their actions through49. See section 2 for definitions of these termshaving dementia or another cognitive impairment.However this type of prejudice cannot be ignored.Each situation needs to be consideredindividually <strong>and</strong> may involve safeguardingprocedures. Providers should ensure that thewishes of the person being discriminated againstare central. They will need to consider whether itis possible to continue providing a service to theperpetrator, whether they must ensure that theydo not have contact with the victim, or how bestto challenge their behaviour. Racial harassmentor violence from <strong>people</strong> using services towardsblack <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic staff should also beincluded in harassment policies.Reporting concerns aboutdiscriminationThere were a number of reasons why black <strong>and</strong>minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> did not always reportdiscrimination to service providers.Some older <strong>people</strong> had lower expectations ofservices <strong>and</strong> described experiences that otherswould define as discrimination but still said, whenasked, that they had not faced prejudice.Everyone may have more fears about raisingconcerns as they get older. If <strong>people</strong> havemigrated to the country, their relationshipto authority may be affected by both theirperception of their position in the host country<strong>and</strong> the role that authorities played in their birthcountry.“They ask me how I feel here, if they ask me Itell but I don’t initiate”Older person living in residential careSocial Care Policy <strong>and</strong> Practice

32 <strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 2Some <strong>people</strong> who did not speak Englishexpressed uncertainty about whether staff <strong>and</strong>other <strong>people</strong> using the service ever said anythingracist about them but assumed that this was notthe case.Others expressed fear of repercussion if theyreported staff, particularly if they were moreuncertain about whether they had experienceddiscrimination.“You feel they don’t want to talk with you, theyjust want to come in <strong>and</strong> out. They might belike that anyway to everyone, I don’t know.But I feel they really don’t want to be there,so it could be racism. They are all white<strong>and</strong> English so far, so maybe. I haven’t saidanything to them, you don’t know what mighthappen if you do”Older person using home careWays <strong>people</strong> using services h<strong>and</strong>leracismBlack <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> using serviceshave developed various strategies for h<strong>and</strong>lingdiscrimination, other than reporting it formally.Some <strong>people</strong> were anxious not to be seen as‘troublemakers’ <strong>and</strong> talked about their ownbehaviour, to avoid overt discrimination:“If you are not difficult to other <strong>people</strong> thenother <strong>people</strong> won’t give you a hard life”Older person living in residential care“I have never faced any racism here. I am agood person <strong>and</strong> get on with others”Older person living in residential care

<strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 2 33Whilst intentions to get on well with others arepositive, this could affect a person’s well-being ifit leads to modifying their own behaviour in orderto avoid racism or seeing any discrimination assomething that they have brought on themselves.Others had ‘voted with their feet’ <strong>and</strong> changedservices if they faced prejudice.“[I faced] subtle racism, which I dealt with ina diplomatic way <strong>and</strong> then stopped using thatagency”Person with a learning disability using home careOthers decided to put up with the discrimination,either for fear of repercussion or because theythought that they did not have any other options.One person living in a care home who hadexperienced verbal abuse said:”If you want to complain you have to go to theoffice <strong>and</strong> complain, <strong>and</strong> that’s difficult to goto them”Older person living in residential careOnly five of the 400 services said they had takenparticular action to improve their mechanismsfor tackling complaints of race discrimination.Information about services <strong>and</strong> rights canprovide <strong>people</strong> with an important safeguardagainst racism, abuse <strong>and</strong> discrimination. 50 Butinformation alone is not enough if <strong>people</strong> are notconfident to come forward. Strategies need to bein place to encourage <strong>people</strong> using services toshare their experiences, to enable staff to identify<strong>and</strong> report discrimination <strong>and</strong> to address howcomplaints are h<strong>and</strong>led if they do arise.Implications of under reportingUnreported discrimination, whether this is dueto uncertainty about whether discrimination hastaken place or because of fear of the implicationsof disclosure, has major implications for serviceproviders. Firstly, it can affect the well-being ofindividual black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> usingservices. Secondly, service providers need toknow when <strong>people</strong> are experiencing racism orother forms of discrimination, in order to takeaction to prevent it happening in the future.50. Social Services inspectorate (1998), IbidSocial Care Policy <strong>and</strong> Practice

34 <strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 2Tackling race discrimination – goodpractice pointersPrevent discrimination by addressing theorganisational culture <strong>and</strong> staff attitudes.Set clear st<strong>and</strong>ards on acceptable staffbehaviour, communicate these to staff <strong>and</strong>monitor practice.Encourage <strong>people</strong> using services to report theirexperiences through both formal <strong>and</strong> informalmethods, for example by enabling <strong>people</strong> to feelconfident to approach the manager.Ensure staff are aware why black <strong>and</strong> minorityethnic <strong>people</strong> using the service may notreport complaints <strong>and</strong> work with individualsto increase trust, their expectations of servicequality <strong>and</strong> to share concerns.Ensure service user guides make clear theorganisation’s expectations of both staff <strong>and</strong><strong>people</strong> using services, around all equality <strong>and</strong>diversity issues.Ensure policies on complaints, harassment<strong>and</strong> discrimination are available to everyoneusing the service in an accessible format<strong>and</strong> that these specifically mention racialharassment <strong>and</strong> discrimination, confidentiality<strong>and</strong> non-victimisation <strong>and</strong> the availability ofindependent advocacy.Always check whether a report ofdiscrimination should be dealt with as asafeguarding issue or requires disciplinaryaction to be taken.Be clear if there are limits on confidentiality, forexample if a complaint is a safeguarding issue,<strong>and</strong> keep <strong>people</strong> informed about the progressof their complaint, as far as possible.Intentional racism, or other intentionaldiscrimination, from staff should be considereda serious disciplinary matter <strong>and</strong> included inthe disciplinary policy.Ensure staff are familiar with whistle-blowingprocedures <strong>and</strong> raise the profile of using theseprocedures when staff witness discrimination.Monitor the types of complaints received <strong>and</strong>actions taken, to see whether these indicatethe need to change any services.Consider a programme of work with <strong>people</strong>using the service to look at prejudice <strong>and</strong>discrimination.

<strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 2 3510. Involving black <strong>and</strong> minorityethnic <strong>people</strong> who use servicesIt is only by engaging with black <strong>and</strong> minorityethnic <strong>people</strong> who use services that providerswill be able to improve their services. Black <strong>and</strong>minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> using services should beviewed as having valuable <strong>and</strong> unique expertise,which cannot be substituted by engaging withblack <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic professionals or‘community leaders’. Building trust <strong>and</strong> allaying<strong>people</strong>’s real fears about getting involved is vital. 51There are different levels of involvement – frominformation, to consultation, partnership <strong>and</strong> ‘usercontrol’. In all these levels, black <strong>and</strong> minorityethnic <strong>people</strong> may face particular barriers to their51. Begum, N (2006) SCIE Report 14: Doing it for themselves:participation <strong>and</strong> black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic service users.London: Social Care Institute for ExcellenceSocial Care Policy <strong>and</strong> Practice

36 <strong>Putting</strong> <strong>people</strong> <strong>first</strong> – equality <strong>and</strong> diversity matters 2involvement. They may face language barriersin the information provided or have to deal withprejudice or stereotyping from others in involvementinitiatives led by <strong>people</strong> using services.Black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> using servicesneed to be involved on the same basis as others,so providers should ensure that all their ways ofinvolving <strong>people</strong> are accessible to them.Providers may also want to consider developingspecific ways of involving black <strong>and</strong> minorityethnic <strong>people</strong>, such as peer support groups. Peersupport groups for young black <strong>and</strong> minorityethnic disabled <strong>people</strong> have been shown toprovide emotional support, the opportunityfor friendship <strong>and</strong> an opportunity to discussissues in a comfortable space. 52 Supportingindividual participation, as well as group-basedparticipation, can also help black <strong>and</strong> minorityethnic <strong>people</strong> to contribute. 5352. Bignall, T, Butt, J, <strong>and</strong> Pagarani, D (2002) Something todo – the development of peer support groups for youngblack <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic disabled <strong>people</strong>. Bristol:Policy Press <strong>and</strong> London: Joseph Rowntree Foundation53. Begum, N (2006), ibidInvolving Black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic<strong>people</strong> who use services – good practicepointersMake sure that existing ways of involving<strong>people</strong> are accessible to the black <strong>and</strong> minorityethnic <strong>people</strong> using the service, for exampleby asking <strong>people</strong> their preferred languagefor materials, whether they want informationin written or audio format <strong>and</strong> by providinginterpreters on request at meetings.Use different tools for feedback includingenabling <strong>people</strong> to express themselves indifferent ways, through talking, writtenformats, etc.Make sure that that you ask <strong>people</strong> using theservice about their views on race equality, forexample in surveys.Work with existing groups of <strong>people</strong> usingservices, for example through residents’meetings on issues of prejudice <strong>and</strong>discrimination, to enable these groups to be amore comfortable environment for a diverserange of <strong>people</strong>.Consider developing specific ways to involveblack <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong> using theservice, such as individual interviews or aninvolvement or peer support group for black<strong>and</strong> minority ethnic <strong>people</strong>.If there are few black <strong>and</strong> minority ethnic<strong>people</strong> using the service, make contact with<strong>people</strong> who could potentially use the service,for example through voluntary or communitygroups, to ask their views on what is importantto them in service provision.