Private Pleasures

Private Pleasures

Private Pleasures

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

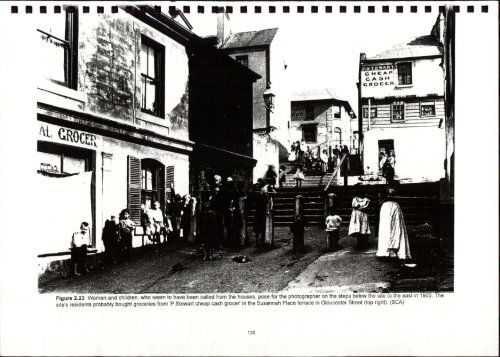

Figure 2.23 Women and children, who seem to have been called from the houses, pose for the photographer on the steps below the east<br />

site's residents probably bought groceries from 'P.Stewart cheap cash grocer' in the Susannah Place terrace in Gloucester Street (top right). (SCA)<br />

135<br />

\,. • I

GODDEN<br />

MACKAY<br />

More than two decades earlier, the Byrne's daughter Catherine married a mariner<br />

named John Winch in 1827. The Winchs bought one of the two-roomed houses on<br />

Cumberland Street, No.122, which was built in as part of the Nicholas development<br />

of the old Cribb land in 1834. Catherine remained here, close to her parents and<br />

childhood home, until her death in 1841, and John stayed on until 1861, about the<br />

same time that the old Byrne house was pulled down. This proximity thus infuses<br />

the small, speculatively built house with meaning: the importance of family ties, and<br />

of locality.<br />

Among the things retrieved from a refuse pit at this house, too, was a bone 'convict'<br />

kit issue knife handle with '23' incised on one side. It was found in deposits dating<br />

to the 1830s or 1840s, that is, the early years of Catherine and John Winch's<br />

occupation. The knife dates from no earlier than the 1830s, and was of the sort<br />

typically issued to convicts under sentence. It may have been purchased from the<br />

Commissariat by the Winchs and seems to have been used until it was broken and<br />

then thrown out. While the 1840s marked the end of transportation and a<br />

groundswell of passionate public opposition to its reintroduction, the association of<br />

this article with convictism apparently had no negative connotations for the nativeborn<br />

Catherine and John. After all, their own parents had been convicts. 35<br />

We have seen that the women of the site came to one anothers' assistance when<br />

their many babies were born, and to help lay out the bodies of their dead. There<br />

were spiritual as well as practical dimensions to the rituals following death, in<br />

particular. Spiritual belief was also materially expressed in the numerous and<br />

varied religious medals, jewellery and rosaries which seem to be particularly<br />

associated with women. The religious medals would appear to be the later<br />

nineteenth century equivalents of the ceramic religious plaques found in the earlier<br />

contexts. Iacono observes their talisman function as 'household protectors', their<br />

inscriptions denoting humility and resignation, yet a belief that the Virgin Mary,<br />

Saint Joseph or guardian angels would intercede pleading for protection and<br />

mercy: and of course their peculiarly Catholic character. That such meaning could<br />

be attached to commodities which were mass-produced in their millions is a good<br />

example of the way people used modern manufactured objects in traditional, very<br />

personal ways. The fact that they were found across the site, and at other sites<br />

such as Lilyvale, suggests that such religious beliefs were also communally shared<br />

and we have parallel evidence for this communality in the documentary record.<br />

The Registers of St Patrick's and St Michael's churches on the Rocks show that<br />

when the babies were brought to be baptised, for their spiritual redemption and<br />

protection, the sponsors, or godparents, who promised to watch over the child's<br />

spiritual welfare were frequently neighbours from the site, fellow Catholics and<br />

evidently trusted friends. Andrew Fennelly, the son of Patrick and Catherine, was<br />

sponsored by Sarah Murphy, who lived nearby in Gloucester Street, in 1865.<br />

Butcher William Mitchell who had lived close to the Hoseman family for twenty<br />

years sponsored the son of Alfred and Rosetta Hoseman in 1887; he had also been<br />

Karskens, Report 136

GODDEN<br />

MACKAY<br />

a witness at their wedding. Thomas and Mary Conwell's son Thomas Denys was<br />

sponsored by the midwife Mary Ann Meddows in 1893; Thomas and Jane Cotter<br />

were the godparents of Lily Sarah White, the daughter of the corner grocers<br />

Thomas and Mary White in 1887. The Whites in turn sponsored the son of Joseph<br />

and Mary Awlsbury in 1889. The Awlsburys lived at 4 Carahers Lane in the<br />

following year and later ran a lodging house at the old Whaler's Arms hotel. 36<br />

The site, then speaks of people drawn together by family relations, by the day-today<br />

transactions in the shops, by the rituals of birth and death, by Catholicism, by<br />

friendship. All of these were expressed, reinforced or even created by the simple<br />

fact of living close by one another.<br />

2.3.4 Clean, Comfortable ... and Respectable?<br />

'Clean, comfortable and respectable' were the key working class values and<br />

aspirations identified by Kerreen Reiger in her review of the 1920 Royal<br />

Commission on the Basic Wage. 37<br />

It seems from the material record that these<br />

were values handed down from the nineteenth century generations of working<br />

people, particularly those of the closing decades. We have seen the unmistakable<br />

evidence for domesticity, comfort, pleasantness and cleanliness, and for the care of<br />

personal appearance through clothing, jewellery and grooming, often against<br />

considerable odds. The 'moralising china' designed to guide and educate children<br />

in moral behaviour, temperance, frugality, industriousness, and 'good humour'<br />

(which 'makes them happy' and 'gives them power to bless') is a startling contrast<br />

to notions of steadfast 'working class' rejection to such 'middle class' cultural<br />

values. We could add a handsome bowl printed with the head of John Wesley to<br />

this collection. It was found at 128 Cumberland Street and was very likely the<br />

possession of Elizabeth Lipscombe and her husband W J Lipscombe, a clerk and<br />

accountant, who lived there between 1861 and 1870. Although tracing these<br />

individuals has been difficult, a check on the religion of other Lipscombe families<br />

revealed that they were all Wesleyans. Wesleyanism attracted the humbler folk of<br />

the working and lower middle classes and was characterised partly by<br />

sabbatarianism, strict morals and the prohibition of drinking and dancing, as well a<br />

belief that God rewarded those who worked hard. Material success was therefore a<br />

sign of God's grace. This bowl, like the presence of the Lipscombes themselves,<br />

reflects the continued blurring of middling and working people, and hence<br />

overlapping culture, which had been a feature of the early Rocks, was still occurring<br />

well into the 1860s. 38<br />

Karskens, Report 137

---------- ---- - ----·· ------------- - ------- --- - ---------- -----<br />

Figure 2.24 Religious medals and jewellery were most likely the possessions of the many Catholics<br />

who lived on the site. The medals bear inscriptions of faith and prayers for protection ; the jewellery<br />

includes a cross intricately carved from bog oak and remains of rosary sets. (Ionas Kaltenbach 1996<br />

138<br />

•<br />

•

GODDEN<br />

MACKAY<br />

A considerable number of artefacts from the site are associated with personal<br />

hygiene and care: they date from the very period when reporters like Jevons<br />

described the people there as having 'dirty clothes, slovenly manner and repulsive<br />

countenance'. Besides the enormous range of dress accoutrements and jewellery,<br />

there are combs made of wood, tortoiseshell, casein and vulcanite. A bone<br />

clothes, hat or furniture brush and tortoiseshell shoe horn kept possesions in good<br />

condition. A delicately-carved fish with rotating fins found under the floor of No.5<br />

Carahers Lane appears to be a rather novel nail cleaner. Ceramic ewers,<br />

washbowls and soap dishes carried on the traditions of cleanliness established in<br />

the convict period. From the 1830s, men slicked down their hair with oil from<br />

rectangular bottles and women daubed themselves with perfume from bottles<br />

which were identified only by manufacturers name before the 1860s, but later came<br />

in an enormous range of indulgent, ornate shapes. 39<br />

There is evidence that, towards the end of the century, working men began to take<br />

more interest in their appearance. Iacono notes amongst the considerable amount<br />

of women's jewellery, rising numbers of men's jewellery items - the collar and cuff<br />

studs, handsome and even extravagant 'bachelor buttons' and so on. Men also<br />

seem to have taken a liking to wearing non-prescriptive spectacles which would<br />

have given them a sober, respectable, dignified appearance. Stretched across<br />

their stomachs and looped through buttonholes in their waistcoats were Albert<br />

chains attached to handsome watches tucked in side pockets. Pocket watches had<br />

been made 'cheap, sturdy and reliable' from the 1870s, and time-keeping had<br />

become both portable and democratised, among men at least. They seem to have<br />

been a particularly male symbol of respectability and status. Bars from the chains,<br />

and watch keys and parts were recovered from the site; clearly these are the<br />

working men whom Graeme Davison described when he wrote:<br />

But on high days and holidays, when he donned his best suit, and<br />

joined his fellows at a trade union picnic, or took his family on an outing,<br />

he would also be likely to wear ... this special badge of the selfregulated,<br />

provident, punctual workingman. 40<br />

While we may consider the rise of domesticity as a sign of 'turning inwards', a<br />

means by which the wider world and the outside environment could be shut out, all<br />

sorts of manufactured artefacts carried images and slogans of issues, topics and<br />

distant places into the home, suggesting that people were curious and interested in<br />

what was happening beyond their own circles. Dinner plates had picturesque<br />

scenes from romantic places, from home and foreign lands, a different view for<br />

each place setting. A copper alloy buckle clasp commemorated the Crimean War<br />

with a scroll and inscription, figurines placed Napoleon and Sir John and Lady Jane<br />

Franklin on the mantelpieces. A mug bearing the image of a bound African woman<br />

with the legend 'She walks in beauty' demonstrates that the site's people were<br />

participants in the world-wide circulation of anti-slavery objects. Ceramic pipes<br />

Karskens, Report 139

GODDEN<br />

MACKAY<br />

stamped 'Uncle Tom's Cabin' after Harriet Beecher Stowe's immensely popular<br />

novel (1852}, suggest that they also belonged to an international culture of<br />

romantic Christian sentimentalism. 41<br />

Wilson has identified two other streams of popular interest and concern in the<br />

ceramic pipe assemblage: pipes which declare support for 'Reform', the English<br />

Reform Bill of 1832, which extended the franchise to all but the very poor; and a<br />

large number of pipes which assert the political and cultural allegiances of Irish<br />

people. The Reform pipes, manufactured in large numbers in Sydney by Samuel<br />

Elliot, are important because they may well express the user's identification with the<br />

classes of people who were given the vote, and, conversely, their clear<br />

disassociation with those who were excluded from the franchise. The Reform Bill<br />

widened the social and political gap between the very poor, and other ranks of<br />

working people. Those who were destitute and in workhouses were affected<br />

instead by the Anatomy Act of 1832, which gave over their bodies to the doctors for<br />

dissection, a fate widely feared among working people. But in other hands and<br />

mouths were sturdy, short-stemmed pipes which called for 'Repeal', the repeal of<br />

the English-Irish union, in effect a slogan and catch-cry for Irish independence.<br />

Others, bearing the Harp of Erin or words such as 'Cork' or 'Colleen' were less<br />

overtly political, yet still instantly recognisable as signs of Irish affiliation. The site<br />

database of occupants includes a large number of Irish names, and research<br />

reveals that many of the immigrants were from Ireland. In this the site is typical of<br />

the Rocks, which Mullens has shown had a higher than average number of Irish<br />

residents overall. It seems likely that commercially mass produced clay pipes<br />

demonstrated allegiance, or identification, or simply the unconscious habits brought<br />

from the old country. 42<br />

Among the residents, too, were people with an interest in and knowledge of<br />

science, for while some used the natural beauty of shells as decorative objects,<br />

others painstakingly built up collections of shells which included examples of the<br />

different species. The curatorial impulse to arrange, identify, class the natural<br />

world, to render it knowable, and thus controllable, was not restricted to the<br />

genteel, leisured men and women of science; at least some tradespeople and<br />

labourers were hunters and collectors too. 43 Like their neighbours on the Lilyvale<br />

site further south, they also collected all sorts of curious things, simply for the<br />

pleasure of having them: a naturally formed hematite cube; whimsical backscratchers<br />

in the shape of a hand with a flounced cuff. A number of reed boxes<br />

were recovered, so it seems that people probably still gathered together to sing<br />

popular songs, accompanied by mouth organs or concertinas, or to listen to airs<br />

played on them.<br />

Although some of the older people, like the Hosemans and Margaret Doyle, were<br />

illiterate, the literacy of residents is documented in the pens, nibs, pencils (and a<br />

fancy Japanese pencil sharpener}, ink bottles, slate and slate pencils, and a hand-<br />

Karskens, Report 140

Figure 2.25: Rising literacy: writing slates and slate pencils, remains of a pen nib, a fancy Japanese<br />

pencil sharpener, and a reading glass to magnify print. (Ionas Kaltenbach 1996)<br />

142

Figure 2.26 Charles Carlson's name stamp, small and elegant, with a handle shaped like a Greek<br />

goddess, was discarded. (Ionas Kaltenbach 1996)<br />

143

GODDEN<br />

MACKAY<br />

The culture of later nineteenth century working people had in many ways departed<br />

considerably from that of the preceding convict and ex-convict generations.<br />

Besides the sheer increase in the number, variety and nature of possessions, some<br />

of the assemblages speak of new notions of individual moral improvement and<br />

personal self control which went beyond external appearances and material wellbeing.<br />

The educative and gentle pastimes are a marked departure from the earlier<br />

often brutal sports and pastimes of sheer pleasure, enjoyed for their own sake.<br />

Yet in some ways the strands of the more traditional attitudes survived. 47 We saw<br />

that the houses and possessions of the earlier generations seemed to exist in a<br />

loosely bisected world: the public and private domains, the outside and the inside,<br />

the appearance of material respectability versus the often unrestrained, impolite,<br />

sometimes violent personal and communal behaviour.<br />

If we look below the floorboards of the later nineteenth century houses we find<br />

other habits which diverge from those of cleanliness and comfort. Rocks people<br />

commonly used their underfloor spaces to deliberately dispose of household<br />

rubbish, by lifting a floorboard and sweeping or throwing it underneath. Broken<br />

glass and china, huge lumps of coral, food scraps, including meat which then<br />

putrefied, and a great number of smaller objects, built up over the years and<br />

choked the underfloor spaces, adding to the already severe problems of damp,<br />

ventilation and unpleasant smells. Dead dogs and cats were disposed of in this<br />

way in 128 Cumberland Street and No.5 Carahers Lane. What is evident here, and<br />

at the Lilyvale site, is an 'out of sight, out of mind' mentality, a culture of disguise, of<br />

covering over or hiding of the problems of high density living. As Wendy Thorp<br />

points out, this may be seen as a practical measure, a response of the lack of<br />

regular garbage collection services, which were not improved until the last decades<br />

of the century. Yet the last families in No1 Carahers Lane - the Hines, Foys and<br />

Morans- seem to have continued the practice even in these years. 48<br />

We might consider the pretty perfume bottles and vases of flowers in the same<br />

way: attempts to cover over bodily and household smells. The evidence for habits<br />

of bodily cleanliness is clear enough in the washbasins and so on, but chronic<br />

water shortages, inconvenience and lack of space may have made full body<br />

bathing difficult, probably a weekly event. It is also possible that habits of dental<br />

hygiene (involving the inside of the body), had not yet been taken up among<br />

working people, though as Wilson points out, tooth decay was observed at all levels<br />

of colonial society. Some toothpaste jars were found in post-1860 contexts, while<br />

the number of toothbrushes recovered were 'surprisingly low', and none at all were<br />

found in the Carahers Lane terraces. Many of the human teeth recovered display<br />

huge cavities, often exposing the root pulp, as well as evidence of abscesses and<br />

severe gum disease. Found in cesspits and underfloor deposits, they had either<br />

fallen out or been self-extracted. A fancy little box of 'Hooper's Cachous' or breathfreshening<br />

lozenges, probably served the same purpose as the perfume. 49<br />

Karskens, Report 144

GODDEN<br />

MACKAY<br />

Although the bellowing beasts and the stench of Cribb's slaughteryard were<br />

banished, large animals such as horses still shared the rather constricted rear<br />

yards of the shops with humans. Horses are recorded both in the bankruptcy<br />

papers for the bakers and butchers who went bust on this site, and also in metal<br />

harness pieces from the well in area H and a 'Farmers Friend' bottle, found in yard<br />

space, which contained medicine for 'bovine or equine complaints'. Cats and small<br />

to medium sized dogs were kept as J'ets as well as for the control of mice and rats<br />

throughout the Nineteenth Century. 5<br />

The proportion of the glass assemblage which was related to alcohol consumption,<br />

together with the hotels which stood on the site, indicate that notions of temperance<br />

probably did not involve teetotalling, or total abstinence from alcohol. While some<br />

families, like the Lipscombes, the Hines, who appear to have married in the<br />

Wesleyan chapel in Princes Street, and perhaps the Briggs, probably shunned<br />

alcohol altogether, drinking remained an important part of Rocks socialising, as it<br />

had been from the early days. The site's people drank wine, beer, champagne,<br />

schnapps, and brandy. This presence of bottles, decanters and hotels, however,<br />

does not automatically give credence to the images of the working classes as<br />

hopelessly debased by intemperate habits. These images were more the product<br />

of middle class obsessions with working people's drinking habits. Temperance<br />

and alcohol consumption could run together, for temperance, or sobriety, in the<br />

earlier sense meant moderation, and the avoidance of drunkenness. Waterhouse<br />

notes this rise in moderation over the Nineteenth Century, and it may be declining<br />

consumption, as well as improved garbage services, which account for the<br />

diminishing numbers of bottles from late nineteenth century contexts. 51<br />

Gambling also remained a popular pastime among working people, one which<br />

continued the traditions of pleasure for its own sake. While this is clear from<br />

historical accounts, archaeological evidence tends to suggest possibilities rather<br />

than incontrovertible evidence. The many gaming pieces manufactured from lead<br />

or shaped from broken ceramics and slate may have been used in 'innocent'<br />

games, children's or adult's; equally they may have been used as counters for<br />

games involving wagering. Wayne Johnson suggests that the numerous Chinese<br />

brass coins, 'cash' or 'half cash', found across the site, with slight concentrations in<br />

the Carahers Lane terraces, were used as gambling counters in games such as<br />

Fan Tan. Their low face value makes their use as money unlikely, while evidence<br />

gathered in 1891-92 on Chinese (and European) gambling described Fan Tan as<br />

'played on a table with the aid of a square sheet of metal, a cup, and a few dozen<br />

brass coins'. 52<br />

Beneath the floorboards, too, were some of the thirty spent cartridges from .22 and<br />

.45 calibre guns, lead shot and gun flints. The presence of such weapons and<br />

their potential violence and danger seems at odds along with the lamps, shell<br />

collections and figurines, making one consider the limits of domesticity and moral<br />

Karskens, Report 145

Figure 2.27 Dental hygiene? Two of the relatively few toothbrushes recovered; the lid from a<br />

toothpaste jar; a metal box for 'Hoopers' breath-freshening lozenges; some of the heavily decayed<br />

teeth, self-extracted and thrown under floorboards or into cesspits; pliers which might have done the<br />

job; and a section of denture which replaced lost teeth. (Ionas Kaltenbach 1996)<br />

146

GODDEN<br />

MACKAY<br />

order. Simon Cooke, in a recent paper exploring nineteenth century suicides,<br />

reflected upon the widespread and completely unregulated availability and use of<br />

all types of guns in the period. The short .22 cartridges from No.1 Carahers Lane<br />

also suggest that women as well as men were gun owners and users, for they are<br />

likely to have come from the small, easily concealed 'Ladysmith', also known as the<br />

'prostitute's favourite'. 53<br />

For all the evidence of respectable culture amongst tradespeople, labourers and<br />

wives, there are also concurrent signs of older cultural streams - less polite, less<br />

inhibited, not entirely pious and proper - and evidence of liveliness, of pleasures, of<br />

certain dangers and risks. But there were other risks -sickness and death - which<br />

were simply part of everyday life, for they still fell outside the sphere of human<br />

intervention and control, and had to be endured and managed by people as best<br />

they could, using the material things at hand.<br />

2.3.5 Babes in the Wood : Sentiment, Grief and the Culture of Consolation<br />

One of the ceramic figurines recovered from the cesspit fill of 122 Cumberland<br />

Street shows two children sheltering under the wings of a now headless angel.<br />

Wilson recounts the tale behind this image: its origins were a rather bleak and<br />

brutal sixteenth or seventeenth century story in which the children are lost in the<br />

forest, and perish of cold and hunger. In the nineteenth century version, revived<br />

in the 1840s and depicted in a famous and much reproduced painting, the lost<br />

children, rather than enduring horrifying deaths, are taken to heaven by an angel.<br />

The story was given an Australian dimension by the tale of the three Duff children<br />

who really were lost in the bush in Victoria in 1864, were rescued, and became the<br />

subject several paintings and an illustrated book for children The Australian Babes<br />

in the Wood: A True Story told in Rhyme for the Young (1866). The figurine, also<br />

dating from the 1860s, encapsulates certain peculiarly Victorian attitudes to death,<br />

particularly child death. In the early period in Sydney, children's deaths were<br />

reported and memorialised in very frank ways, often dwelling on the circumstances<br />

and horror of death, the grim fact of mortality, and the grief of bereaved parents.<br />

The rise of 'sentiment' seems in part to have been an attempt to mitigate, to cover<br />

over or disguise the harsh facts of disease, death and bodily decay. Figurines such<br />

as this one were not merely commercialised commodities, bereft of meaning, but<br />

represent a culture of consolation. At least the poor 'Babes' were now safe in a<br />

'better place' with the angels; they were spared the torments and tribulations of life;<br />

they would remain innocent forever. 54<br />

If we examine the family histories of many of our residents, the reasons for such a<br />

culture become clear. Among the impersonal infant mortality figures of the<br />

Nineteenth Century, the victims of summer intestinal diseases, dehydration, and<br />

the terrible epidemics, are five of the ten children of Catherine Fennelly, born in<br />

various Gloucester Street terraces between 1857 and 187 4. Ellen Hoseman at 114<br />

Karskens, Report 147

Figure 2.28 Babes in the wood: two children shelter under the wings of a now headless angel. Other<br />

figurines include the heads of Mother Goose and a gnome. Nappy pins and bone spoon suitable for<br />

feeding babies also bespeak the great numbers of infants born in the site's houses.(lonas Kaltenbach<br />

1996)<br />

148

GODDEN<br />

MACKAY<br />

Cumberland Street lost six of her twelve infants. Margaret Doyle lost two<br />

daughters before her daughter Margaret was born. Florence Lathrope, who<br />

probably ran the old Bird in Hand hotel as a boarding-house between 1903 and<br />

1904, had lost three of her five children and her husband before she came to live<br />

on the site.<br />

These losses, and the grief they entailed, the sickbeds, small coffins and the<br />

funerals, were thus very common occurrences, typical rather than atypical<br />

household experiences. That the same households should also display artefacts of<br />

consolation and sentiment, buffering the direct and constant interface of life and<br />

death, is not surprising. Mourning jewellery made of costly jet and its imitation,<br />

vulcanite, were also worn by the site's women. They were large, striking pieces,<br />

designed to be seen against heavy, voluminous, black mourning clothes. These<br />

pieces are also signs that the site's women were participants in the intricate and<br />

formalised mourning rituals developed to deal with both public mourning and<br />

private grief over the Nineteenth Century. Like the rise of the sentimental itself,<br />

such practices were newly adopted rather than traditional, since there is no<br />

indication that the lower orders of the convict period had such formalised mourning<br />

periods or material accoutrements. Again, it would seen that such modern rituals<br />

of propriety crossed the boundaries of social status. 55<br />

We might then think of the culture of domesticity and comfort as a whole in a<br />

similar way. The firm control and shaping of household interiors by women, the<br />

adoption of what was held to be 'proper, should be considered against the<br />

precariousness of both physical health and economic stability. The latter were of<br />

fundamental importance, and both were often beyond ·the control of working<br />

people. Although they now turned more often to doctors {though not, apparently, to<br />

dentists) medical science had not yet developed to the stage where many diseases<br />

or injuries were treatable or at least mitigated. The archaeological evidence<br />

indicates that people also continued the earlier traditions of self-help, dosing<br />

themselves with emetics like salts and cod liver oil, and the patent medicines which<br />

became popular from the 1860s. The site also yielded various glass syringes and<br />

even a cupping glass for bleeding patients. 56<br />

So the determined domesticity - lace curtains, colourful sets of china, the pretty<br />

vases and figurines of poodles or ladies or lambs-, and the good and fashionable<br />

clothing, were a kind of defiance, and a defence, against bouts of unemployment,<br />

the sickbeds, and the deathbeds. Let us consider the experiences of labourers<br />

like Joseph Duncan {who had lived in 122 Cumberland Street, where the 'Babes'<br />

figurine was found, in 1867 -1870) and Searight Newton, a wharf labourer who<br />

occupied 4 Cribbs Lane in 1896. Both these men went bankrupt as a result of illhealth<br />

and under, or unemployment. Duncan, who filed for bankruptcy in 1878<br />

over debts totalling forty-five pounds, had already lost all of his household furniture<br />

(worth only six pounds) and attributed his situation to 'being laid up with a poisoned<br />

Karskens, Report 149

GODDEN<br />

MACKAY<br />

finger and afterwards with broken ribs'. He had a wife and five children, and the<br />

family was left with only their clothing. Searight Newton, who had a flowing<br />

copperplate signature, filed for bankruptcy in 1896 when he lived on the site. He<br />

also had a wife and five children and was being pressed by creditors for debts of<br />

sixty-eight pounds, and hounded by the landlord, Peter MacManus, for rent. Again,<br />

he had been laid up for eighteen months and had no work. He reckoned his<br />

earnings had been less than one pound a week in the past year. The family's<br />

furniture was worth only £1.5s so they were allowed to keep it. The Newtons were<br />

among the many families who quickly moved on from the site. 5 7<br />

The site's people would have been well aware of their neighbours' predicaments,<br />

and they knew such misfortunes could befall almost any family. Such example<br />

might well move people to cling ever more tightly to the known, the controllable, the<br />

ordered. On the other hand they would also have observed Charles and Catherine<br />

Carlson's success, and the success of other immigrant families who became<br />

property owners. It is likely that most people's experience fell between these<br />

extremes of success and distress, but their everyday social observations were<br />

Janus-faced, they could see evidence of both oppression and opportunity.<br />

We have seen evidence that working people took measures to control their own<br />

destinies- these are potently symbolised in the wharf labourer's union token and in<br />

the measures taken for birth control. But the household assemblages retrieved<br />

from the site also speak, in part, of older streams and attitudes, of resignation and<br />

of consolation, of artefacts purchased, arranged and used as ways of coping with<br />

things that were as yet beyond human control, of softening the blows, of making<br />

misfortune more bearable. They are the private inversions, the reverse side, of<br />

those images and artefacts of the bustling, optimistic city life, the gas-lit streets<br />

crowded with a throng of well-dressed working people, the gleaming new<br />

department stores, the theatres and sporting venues where the crowds were<br />

increasingly well-behaved. 58<br />

Archaeology from the Cumberland and Gloucester Streets site reveals the culture<br />

of working people to be marked not by homogeneity, but diversity, by strands of<br />

belief and behaviour which overlap, qualify or contradict one another, and by the<br />

movements of people, ideas and things. These divergences speak more of<br />

working classes, of ethnic, cultural, economic and generational differences, than of<br />

a single working class. Yet streams of commonality may also be observed in the<br />

broad acceptance of mass-produced commodities, and in the many ways these<br />

were transformed into meaningful possessions. Those meanings were shaped, in<br />

turn, by the particular situation of working people: responses to the problems and<br />

the excitements of urban life, the miseries and joys of high density living, the<br />

search for security, the search for consolation.<br />

Karskens, Report 150

GODDEN<br />

MACKAY<br />

The perspective from the neighbourhood and households reveals that people were<br />

also drawn together by kinship ties, by Catholicism, by small scale and personal<br />

relationships with shopkeepers, and by friendships and common experiences and<br />

habits. These things - personal, intimate, day-to-day - mattered to them (especially<br />

women) at least as much as workplace experiences, and perhaps shaped 'identity'<br />

and allegiances more directly than the broader, more abstract concept of 'the<br />

working class'.<br />

Another way to explore how 'class' and class distinction were perceived, and thus<br />

created, is through the eyes of outsiders. The next chapter will examine what they<br />

thought they saw in places like the Rocks.<br />

Karskens, Report 151

2.3.6 Endnotes<br />

GODDEN<br />

MACKAY<br />

1 For general accounts of the industrial revolution and the rise of the working class in<br />

Australia see Buckley and Wheelwright, No Paradise for Workers; R.W. Connell and T. H.<br />

Irving, Class Structure in Australian History. Documents, Narrative and Argument,<br />

Melbourne, Longman Cheshire, 1986, fp 1980. See also E.P. Thompson, Making of the<br />

English Working Class.<br />

2 Wheelwright and Buckley, No Paradise for Workers, Chapter 9; see also Fox, Working<br />

Australia, Chapter 6<br />

3 Fitzgerald, Rising Damp, p143ff; Fox, Working Australia, p54ff; Waterhouse, <strong>Private</strong><br />

<strong>Pleasures</strong>, p53.<br />

4 Peter Proudfoot, Seaport Sydney The Making of the City Landscape, NSW University<br />

Press, Sydney, 1996, pp37-68; interview with Mr Herbie Potter, 12 December 1995; pers.<br />

com. Mr Bill Ford, October 1996.<br />

5 Fitzgerald, Rising Damp, conclusion; quote p3.<br />

6 Waterhouse, <strong>Private</strong> <strong>Pleasures</strong>, Chapter 3; see also 'Popular Culture and Pastimes' in<br />

Neville Meaney (ed.), Under New Heavens : Cultural Transmission and the Making of<br />

Australia, Heineman, Melbourne, 1989, pp237-285, see p270.<br />

7 Analysis of Residents Database; the spread of industrial development to the west of the<br />

city around Darling Harbour is well-described, in microcosm, in Thorp, 'Market City<br />

Development Paddy's Market Archaeological Excavation, Volume 2 Main Report'.<br />

8 Mullens, citing Terry Kass, 'Socio-Economic History of Miller's Point NSW, also makes<br />

this point, see 'Who are the People', pp 99, 103.<br />

9 Analysis of Residents Database. The idea that back-lane houses might have been<br />

occupied by different types of people from the buildings along the main streets, was<br />

suggested in Karskens and Thorp, 'History and Archaeology in Sydney', p70. However both<br />

the archaeological assemblages from the site, and the analysis of the Residents Database<br />

show that no such clear distinction existed.<br />

10 Analysis of Residents Database; Mullens, 'Who are the People', pp87; 84-85; James<br />

Broadbent, 'The Push East: Woolloomooloo Hill: the first suburb', in Max Kelly (ed.), Sydney,<br />

City of Suburbs, New South Wales University Press, Sydney, 1987, pp12-29.<br />

11 See discussion of mariner publicans in Karskens, 'Historical Discourse', pp54-56;<br />

Residents Database, entries for Cox, Fay and Berry families and for William Mitchell;<br />

Bankruptcy Files, William Adams, 18 August 1883; James Laing, 6 September 1877<br />

AONSW.<br />

Karskens, Report 152

GODDEN<br />

MACKAY<br />

25 Wilson, AR- Ceramics p1 00; Thorp, 'Report on Lilyvale' Section 4.3; and her 'Market City<br />

Development Paddy's Market Archaeological Excavation, Volume 2 Main Report', p96.<br />

26 For discussion of the impact, role and uses of advertising, brand names and<br />

standardisation, see Carrier, Gifts and Commodities, Chapter 4.<br />

27 Iacono, AR-Misc. pp51 , 54; Wilson, AR-Ceramics p94; Holmes, AR-Metal p11 0; James<br />

Laing, bankruptcy papers, 6 September 1877, AONSW.<br />

28 Steele, AR-Bone p96; Holmes, AR-Metal p113; Carney, AR-Giass pp97-99.<br />

29 Wilson, AR-Ceramics p1 01 ; re eggs, Wilson pers. com. October 1996; Holmes, AR-Metal<br />

p96; Barnes, AR-Building Mat. pp11, 63, 69.<br />

30 Wilson, AR-Ceramics pp96,105; Iacono, AR-Misc.p62; Carney, AR-Giass p135 and pers.<br />

com; Holmes, AR-Metal pp22 ; Bower, 'Leather', p5.<br />

31 See Bankruptcy Files on William Adams, 18 August 1883; James Laing, 6 September<br />

1877, AONSW; compare with discussion of shopkeeper/neighbourhood relations in England<br />

and America in Carrier, Gifts and Commodities, pp71-72, 87-88, 92; Johnson, 'Coins,<br />

Medals and Tokens' pp21, 29; Thorp, 'Report on Lilyvale', Section 4.3.<br />

32 Residents Database, entries for Berry and Share families; note the striking resemblance of<br />

this progression to the female-centred stories told by Derry in 'Daughters and Sons-in-Law of<br />

King Cotton'.<br />

33 Residents Database, entries for these families; bankruptcy papers for Stephen Doyle, 2<br />

September 1859 AONSW; and data on the MacNamara family courtesy Margaret Bettison.<br />

34 Richard Burne Cumberland Street to Margaret Burne & Others, No 58 1816, Old<br />

Registers; RAB; Garner, 'Irish on the Rocks', pp.83-84.<br />

35 Iacono, AR-Misc. p85; Wilson, pers. com. re kit knife, October 1996; Hirst, Convict society<br />

and its enemies, pp211 ff.<br />

36 Iacono, AR-Misc. p69; some of these beliefs and habits related to faith in the intercession<br />

of saints are similar to those described by Shulamith Shahar in Childhood in the Middle<br />

Ages, London, Routledge, 1992, p143; Residents Database, see entries for these<br />

individuals and families.<br />

37 Kereen M. Reiger, ' "Clean and Comfortable and Respectable": Working Class Aspirations<br />

and the Australian 1920 Royal Commission on the Basic Wage', in History Workshop, 27<br />

1989, 86-105.<br />

Karskens, Report 154

GODDEN<br />

MACKAY<br />

38 Waterhouse, <strong>Private</strong> <strong>Pleasures</strong>, pp99-1 00,1 08; Wilson, AR-Ceramics p95; Brighton also<br />

notes such artefacts in the Five Points assemblage: the 'Father Mathew Temperance<br />

teacup', for example, 'Prices Suit the Times' p8.<br />

39 Stanley Jevons, cited in Iacono, AR-Misc. p84; re artefacts, see pp83-85; Wilson, AR<br />

Ceramics p102; Carney, AR-Giass p108. Inventories of household goods in bankruptcy<br />

papers also usually list wash sets.<br />

40 Iacono, AR-Misc pp76-77; Graeme Davison, The Unforgiving Minute: How Australia<br />

Learned to Tell the Time, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1993 pp66-70.<br />

41 Compare with discussion in Thorp, 'Report on Lilyvale' Sections 4.3 and 5.1.2; and<br />

'Market City Development Paddy's Market Archaeological Excavation, Volume 2 Main<br />

Report', pp95ff; 118; Wilson, AR-Ceramics pp95-96; Iacono, AR-Misc pp63. On 'Uncle<br />

Tom's Cabin' see Waterhouse, <strong>Private</strong> <strong>Pleasures</strong>, pp68-69, 73; and From Minstrel Show to<br />

Vaudeville, pp70-74.<br />

42 Wilson, AR-Ceramics pp98-99; compare with Gojak and Iacono, 'Sydney Sailors Home',<br />

p31 and Denis Gojak, 'Ethnicity and nationalism in nineteenth century Sydney: two examples<br />

from Cadman's Cottage, The Rocks', paper presented to the 1991 Rocks and Millers Point<br />

Historical Archaeology seminar. Re Anatomy Act and Reform Bill see Ruth Richardson,<br />

Death, Dissection and the Destitute , Routledge and Kegan Paul, London, 1987; Mullens,<br />

'Who are the people', pp80, 81, 85, 88.<br />

43 Steele, AR-Bone pp13-14, Table 2.3, pp15-17, 90,114 and pers. com; compare with<br />

Thorp, 'Report on Lilyvale', Section 4.3. Compare with the profiles of collectors in Tom<br />

Griffiths, Hunters and Collectors: The Antiquarian Imagination in Australia, Cambridge<br />

University Press, Melbourne, 1996, p67ff.<br />

44 Iacono, AR-Misc pp 78,82; Carney, AR-Giass Type Series List p46; Martin Lyons and<br />

Lucy Taksa, Australian Readers Remember, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1992 pp7-<br />

8.<br />

45 Holmes, AR-Metal p136 (reed boxes) p135 (name stamp); Iacono, AR-Misc. p79<br />

(collectibles); Residents Database, entries for Charles and Catherine Carlson, compiled from<br />

RBDM, Naturalisation Papers, AONSW, death and funeral notices in SMH.<br />

46 Family data on Portugese residents courtesy Margaret Bettison; Holmes, AR-Metal p137;<br />

Iacono, AR-Misc. p89; Residents Database, entries for Henry and Sarah Ann Briggs,<br />

compiled from RAB, RBDM; and Wilson. 'Cumberland Street/Gloucester Street List of Site<br />

Occupants'.<br />

47 See Waterhouse, <strong>Private</strong> <strong>Pleasures</strong>, Chapters 1-3.<br />

48 Holmes, TR-B pp17-19; and AR-Metal p86; Steele, AR-Bone, pp84, 90; Thorp, 'Report on<br />

Lilyvale', Section 4.3. By contrast, the only rubbish purposely thrown under the floorboards<br />

Karskens, Report 155

GODDEN<br />

MACKAY<br />

at Lindesay, Darling Point, was probably put there by the tradesmen undertaking<br />

renovations, see Lavelle, 'Lindesay', pp.35, 36, 41.<br />

49 See David Clark, 'Worse than Physic: Sydney's Water Supply 1788-1888', in Max Kelly<br />

(ed.), Nineteenth Century Sydney. Essays in Urban History, Sydney University Press,<br />

Sydney, 1978, pp54-65. Re teeth, transcript of interview with Dr Sam Malek, dental<br />

surgeon, 12 June 1996. Dr Malek examined the teeth from the site. Wilson, AR-Ceramics<br />

p1 02; Iacono, AR-Misc p84; Holmes, AR-Metal p31 (Metal Box 1 ).<br />

50 Bankruptcy papers, James Laing and William Adams; Iacono, AR-Misc. pp62, 64;<br />

Carney, AR-Giass p118; Steele, AR-Bone p90.<br />

51 Carney, AR-Giass pp97-99, 109 and pers. com; Waterhouse, <strong>Private</strong> <strong>Pleasures</strong>, pp63,<br />

99.<br />

52 Waterhouse, <strong>Private</strong> <strong>Pleasures</strong>, pp80-81; compare with MacCalman, Struggletown;<br />

Wilson, AR-Ceramics p105; Iacono, AR-Misc p82; Barnes, AR-Building Mat. p59; Johnson,<br />

'Coins, Medals and Tokens', pp29-30.<br />

53 Holmes, AR-Metal p114ff; Simon Cook, 'Violence and the body: methods of suicide,<br />

gender and culture in Victoria, 1841-1921', paper presented at the Australian Historical<br />

Association Biennial Conference, Melbourne, July 1996.<br />

54 Wilson, AR-Ceramics p97; and pers. com. August 1996; Leigh Astbury, City Bushmen:<br />

The Heidelberg School and the Rural Mythology, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1985,<br />

p158ff; Karskens, 'The Rocks and Sydney', pp230-232; John Morley observes the panoply<br />

of Victorian death-related rituals and artefacts with a kind of horrified fascination in Death,<br />

Heaven and the Victorians, University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, 1971.<br />

55 Residents Database, entries for the Fennellys, Hosemans, Doyles and Florence Lathrope;<br />

Iacono, AR-Misc p75ff.<br />

56 Many of the Bankruptcy Files examined included debts owed to doctors for medical<br />

consultation and treatment; Carney, AR-Giass pp105, 134. Compare to evidence for selfhelp<br />

in the convict period, Karskens, 'The Rocks and Sydney', pp113-114. Further<br />

comparative research on the occurence of patent medicines, and their purpose, would throw<br />

more light on health and attitudes to the body and illness; compare to Bonasera, 'Good for<br />

What Ails You: Alternative Medicinal Use at Five Points'.<br />

57 Bankruptcy Files, Joseph Duncan, Laborer, 23 September 1878; and Searight Newton,<br />

Wharf Laborer, 6 July 1896, AONSW.<br />

58 See Waterhouse, <strong>Private</strong> <strong>Pleasures</strong>, Chapter 3 and discussion, note 11 p88; compare with<br />

Patrick Joyce, Visions of the People. See also Yamin, 'From Tanning to Tea': 'the working<br />

class residents of Block 160 used material possessions to express their rights as members<br />

of a society increasingly divided by class .. .', pp12-13.<br />

Karskens, Report 156

GODDEN<br />

MACKAY<br />

tasty sauces and condiments, tea, alcohol and perhaps more sugar than was good<br />

for their teeth 4 .<br />

The artefact record offers evidence that people had leisure time and disposable<br />

income to indulge in pastimes and hobbies, and to delight, entertain and educate<br />

children; and also artefacts which speak directly about moral standards and<br />

behaviour and religious beliefs and commitments. In the context of the sheer<br />

numbers and quality of material culture, the reuse and reshaping of disposable<br />

commodities seems to be a cultural habit rather than an economic measure, a<br />

continuation of the tradition of practicality, handiness and the avoidance of waste;<br />

or again, habits learned in times of want. Stephen Doyle's use of a ginger beer<br />

bottle as a pestle, for example, may be considered alongside the highly ornate,<br />

finely crafted gold earring set with faceted beryl stones found in the house, which<br />

may have belonged to his wife, Margaret 5 .<br />

Analysis of the cesspit deposits located some examples of parasite eggs<br />

(roundworm and whipworm), but their numbers seem quite low in comparison with<br />

the levels in American cities, where they occurred at a rate of 20,000 eggs per<br />

gram of soil in the Eighteenth Century, and in the hundreds per gram of soil at the<br />

end of the Nineteenth Century. Other comparisons with the crowded working<br />

people's areas of United States cities are also instructive. The 1970s excavation of<br />

late eighteenth century privies in Philadelphia's New Market recovered the bones<br />

of two infants, while John P. McCarthy's excavation of a late nineteenth century<br />

Minneapolis privy 'associated with a "skid row" of boarding houses and bars',<br />

recovered the bones of a six-month-old child. No parallel evidence of such<br />

desperate measures of disposal, and possibly infanticide, have been found here or<br />

on any other Sydney archaeological site 6 .<br />

There is one significant change in the ceramic assemblage, however, which seems<br />

to indicate a decline in standards, or at least consumer purchasing power in the<br />

period 1880-1890. The appearance, from the 1880s of thick, heavy, rather<br />

inelegant white 'hotel-style' ware, decorated with only paired bands, marks a<br />

complete departure from the traditional taste for fine or pleasant china, with<br />

elaborate patterns in a great many colours. Here we have an indication that at least<br />

some families could no longer afford to buy what they preferred, a situation which<br />

would have been exacerbated by widespread unemployment during the 1890s<br />

Depression 7 .<br />

The artefact assemblages must also be set within the context of the small size of<br />

some of these houses, and their close proximity to one another, measurable and<br />

observable on the site. Clearly the houses were sometimes (though not<br />

necessarily always) overcrowded, particularly when considered in the light of<br />

research which showed that some families had up to twelve children. Let us revisit<br />

No.1 Carahers Lane where Elizabeth and Thomas Hines lived between 1877 and<br />

Karskens, Grace 158

GODDEN<br />

MACKAY<br />

works, from horse droppings,cesspits and so on, would have been commonplace,<br />

at least in the 1850s, 1860s and 1870s, and they must have combined to assail the<br />

noses of the middle class observers and visitors. Miasmic smells were also<br />

thought to cause disease, hence the conflation of such areas, and their people,<br />

with ill-health and death.<br />

In reality it was not the smells, but the conditions of high-density urban life which<br />

allowed diseases to sweep through the population. In spite of evidence of<br />

domesticity, comfort, self-respect and measure of personal cleanliness, the families<br />

of unskilled labourers and skilled tradesmen of neighbourhoods such as these<br />

bore the heaviest suffering and losses during each terrible nineteenth century<br />

epidemic 12 .<br />

But the site also offers some signs of considerable improvement in standards of<br />

living in the last decades of the century, precisely the period which historical<br />

sources and interpretations suggest were characterised by decline and decay. The<br />

connection of the houses to the sewerage system, and to water and gas mains,<br />

improved hygiene and comfort enormously, while enclosed stoves eliminated the<br />

hazards and mess of open fires (though not the heat and smells). Streets and<br />

lanes were paved in hard surfaces, drains and gutters were built of stone.<br />

Caraher's soap and candle works just to the south were shut down and demolished<br />

in 1881. As we shall see, Rocks people were themselves active over the decades<br />

in lobbying the Sydney Corporation for improvements in their local urban<br />

environments. Rubbish removal services improved towards the end of the<br />

century, as is indicated by the fall in numbers in some types of artefacts. Although<br />

Rocks houses were almost always described as cheap and poorly built, those on<br />

the site were quite solid or substantial, and many showed signs of having been<br />

repaired and improved over the years. There were numerous attempts to deal with<br />

the drainage problems inherent in the location and topography of the site, and paint<br />

and mortar were applied to combat damp walls 13 . While infant mortality was still<br />

shockingly high overall, the rate actually fell considerably in the inner city<br />

neighbourhoods from 1880, while it rose in the outlying suburbs. The improved<br />

chances of city-born babies were most likely a result of better sanitary facilities and<br />

practices 14 •<br />

What the artefact assemblages and building foundations reveal, in balance, is that<br />

sweeping generalisations over time about 'slums' and 'slum dwellers' are<br />

unfounded. These are derogatory stereotypes which tell us more of the fears,<br />

language and shared understandings of the observers than the people they<br />

'observed'. This does not mean that there were no problems of social and<br />

economic inequity, poverty, disease, or poor living conditions in Sydney. There<br />

were certainly difficulties in the processes of urban consolidation and growth on<br />

this site, as on others, though they were partly mitigated in time. The point is that<br />

these were not necessarily connected to, or the same as, widespread, constant<br />

Karskens, Grace 161

GODDEN<br />

MACKAY<br />

and severe poverty, filthy bodies, low morals or criminal behaviour in a sinister<br />

other- or underworld. There were undoubtedly pockets or alleys or courtyards of<br />

extreme poverty and degradation in other parts of the Rocks and Sydney; they too<br />

may have changed for the better or worse over time. It seems that the middle<br />

class observers and improvers sought out and visited the worst of places, selected<br />

and focused upon certain aspects of what they saw, and employed a well-known<br />

stock of rhetoric to synthesise these into images of 'slums'. These images were<br />

then expanded to portray the morals and lifestyles of working people as a whole.<br />

Some observers even noted signs of cleanliness, domesticity and community, as<br />

we have found on this site, but failed to alter their prejudicial judgements of working<br />

people's neighbourhoods 15 .<br />

It appears likely, then, that nineteenth century class barriers may have had more to<br />

do with the construction of such images, than with actual habits and lifestyles of<br />

working people themselves. The cultural and physical separation of working from<br />

middle class people was accompanied by a hardening of middle and upper class<br />

attitudes, to the extent that fear and loathing of working people made them seem<br />

scarcely human.<br />

But if working people lived in many other parts of Sydney, some of which might well<br />

have endured much worse conditions, why was the Rocks so often singled out for<br />

moral and social condemnation? Why was this particular neighbourhood invested<br />

with such notoriety? Was there something in the cultural behaviour or social profile<br />

of the people there which marked the Rocks out as separate, different from other<br />

places? Had they perhaps held on to the old habits of the convict generations<br />

which the rest of Sydney had left behind?<br />

At one level, it is clear that the site's people had the same material possessions<br />

and habits (matched up-to-date china, typical glassware and cutlery assemblages,<br />

fashionable beads and buttons and so on) as any other neighbourhood in Sydney,<br />

and even strands which indicate that notions of domesticity and moral order were<br />

similar to those of the middle class. Other signs speak of a distinctly working<br />

people's neighbourhood: evidence of working at home; clay pipes of the sort<br />

commonly associated with working people throughout the Nineteenth Century; 16<br />

proximity to workplaces; the close configuration of houses; a certain pragmatism in<br />

the re-use and reshaping of some of the artefacts and in rubbish disposal patterns.<br />

These would probably be found in any neighbourhood of similar social profile.<br />

But overlaying the 'typical' assemblages were some subtle patterns of distinction.<br />

There was a higher occurrence of glass decanters, particularly the ring-necked<br />

'Irish decanters', evidently in use here well after they had fallen out of favour<br />

generally. This is a striking continuity with the communal drinking patterns of the<br />

early period, when people are often glimpsed with decanters or bottles in their<br />

hands, fetching rum from nearby hotels and returning to their homes to share it with<br />

Karskens, Grace 162

GODDEN<br />

MACKAY<br />

family and friends. There appears to be much larger number of oyster shells than<br />

is generally found on domestic sites elsewhere in Sydney. Again, this represents an<br />

unbroken thread throughout the occupation of the site, for oysters remain a<br />

constant staple in Rocks diets and may perhaps be considered as food particularly<br />

associated with waterfront neighbourhoods 17 .<br />

Some of the houses and pubs which stood on the site during most of the<br />

Nineteenth Century had been built in the 1810s and 1820s. With their oldfashioned,<br />

simple lines and plain faces they would have seemed ugly and crude to<br />

outsiders more accustomed to the splendours of modern Victorian architecture.<br />

Moreover, they were direct visual, perhaps sinister, links with the convict period, a<br />

subject of increasing shame and embarrassment as the century progressed. The<br />

Rocks itself, although much pared-down and built up over the century, nevertheless<br />

retained the distinctive steep and rocky topography which had given it its commonuse<br />

name, and which shaped the crooked streets, odd intersections, steep<br />

connecting flights of stairs and narrow lanes. It was a townscape which seemed to<br />

outsiders to be the negation of all that was orderly and controlled, gridded and<br />

knowable; the fearful manifestation of a city expanding out of control, and into<br />

chaos 18 .<br />

The significance of other artefact patterns and presences becomes still clearer<br />

when we note that the Rocks in the latter half of the Nineteenth Century actually did<br />

have a higher than average proportion of Irish and Chinese people. Mariners and<br />

others whose working lives revolved around the sea and shipping also lived there in<br />

large numbers, as they had done since the beginning of European settlement. The<br />

Rocks thus had high proportion of immigrants, and this was demonstrated by the<br />

database compiled on the site's residents 19 . Not only were foreign languages and<br />

strange clothes, and a sense of constant movement inward and outward, part of<br />

the Rocks streetlife, but visual symbols of allegiance, like Irish pipes or decanters,<br />

jewellery made of bog oak or decorated with Celtic designs, or popish, superstitious<br />

little medals with foreign inscriptions, may well have caught the eye of the fearful,<br />

yet fascinated outsider. On the site, too, there appear to be parallel patterns of<br />

Irish association: Irishman Owen Caraher tended to let his houses in Carahers<br />

Lane to his countrymen and women, to people with names like Duffy, O'Shea,<br />

O'Brien, Murphy and MacNamara 20 .<br />

Jane Lydon's recent study of the Chinese of the Rocks explores both below the<br />

surface of the European representations of Chinese as 'secret, dark, dirty and<br />

immoral', and beyond the rather narrow historiographical confines of racism and<br />

oppression. She weaves together the distinctive artefacts of Chinese culture found<br />

on archaeological sites, such as cooking pots and medicine phials, and the range<br />

of cultural and social strategies (resistance, gestures of goodwill, appropriation, the<br />

maintenance of public and private persona) employed by the Chinese to make<br />

their way in a repressive society, to survive, and even 'beat the system'. Lydon ·<br />

Karskens, Grace 163

GODDEN<br />

MACKAY<br />

also examines the way that the material culture of Chinese and Europeans,<br />

particularly ceramics, moved both ways, as it had done since the Seventeenth<br />

Century. While English earthenware is found associated with Chinese artefacts,<br />

Chinese ceramics, including bowls, ginger jars, and storage vessels, with their<br />

exotic patterns and mysterious characters, reappear on the<br />

Cumberland/Gloucester Streets site from the 1850s, as they do on other Rocks<br />

sites, reflecting rising Chinese immigration in that decade. Sherds of alabaster<br />

and steatite suggest Chinese scenic figurines, such as those found at Lilyvale;<br />

Chinese coins or 'cash' used in fantan were also found on the site 21 .<br />

The continued presence of mariners and those associated with the sea-going<br />

trades is signalled by artefacts dating from early period to at least the 1860s. A<br />

sailor's palm, used to protect the hands while repairing sails had been lost in<br />

George Cribb's well, while the Williams well contained a marlin spike used in<br />

ropemaking, and a grappling hook. The site, like other Rocks sites, Lilyvale and<br />

Reynolds Cottage, also yielded whale teeth, including whole and worked items, and<br />

sawn tip or root section offcuts. Steele points out that sperm whale teeth were<br />

valuable trade items between whalemen and Pacific Islanders; they were also<br />

'divided up among the crew members during long whaling voyages', and used as<br />

'spare change by the ship's purser and crew alike to pay for provisions and repairs<br />

to ships'. Mariners, with their distinctive language and lore, skills and clothes, were<br />

another group traditionally regarded with distrust and suspicion. They were 'men<br />

apart' whose lifestyles seemed to transgress every principle of social order and<br />

stability (though in reality, their lives at sea were utterly bound, minutely divided,<br />

and highly disciplined). They tended to be characterised either as foolish, rather<br />

childlike spendthrifts, 'Jack Tar' at the mercy of the 'land sharks of the Rocks' and<br />

in need of care and protection; or alternately as wild, dangerous strangers given<br />

completely to the pursuit of drink and sex, who were in need of Christianisation and<br />

moral reform. The Sailor's Home, associated with the Christian philanthropic<br />

Bethel Union Society, was opened in George Street below the Rocks in 1864. This<br />

institution offered both shelter and moral influence, though, as suggested<br />

elsewhere, the presence of numerous gin bottles among the sailor's refuse<br />

suggests that calls to sobriety and tea drinking was not entirely heeded. The<br />

Sailor's Home, airy, orderly, regularly divided, also constituted the reverse of the<br />

sort of cramped back-lane lodging house which No.5 Carahers Lane appears to<br />

have been. A large proportion of the worked whale teeth occur in the same<br />

underfloor deposits as a inordinate number of clay pipe fragments, and a large<br />

range of middling to cheap cutlery, which suggest that the tenants here sublet to a<br />

number of seamen and other itinerants 22 .<br />

There are those objects which speak of immigrants who settled, at least for a time,<br />

on the Rocks -the Carlson name stamp, the Briggs measure, the anonymous F.<br />

Chapman's inscribed tag. The Rocks was a gateway, an entrepot, a place of<br />

coming and going, a first foothold. A well-preserved billycan lid and a pannikin<br />

Karskens, Grace 164

2.4.1 Endnotes<br />

GODDEN<br />

MACKAY<br />

1 See Fitzgerald, Rising Damp, p229; see also Max Kelly, 'Picturesque and Pestilential: The<br />

Sydney Slum Observed 1860-1900', in Kelly, Nineteenth Century Sydney, pp66-80.<br />

2 Mayne, Representing the Slum; David Englander cited in Mayne, 'A barefoot childhood: so<br />

what?'; see also The Imagined Slum: Newspaper Representation in Three Cities 1870-<br />

1914, and the H-Net Urban History Discussion List, contributions from John P. McCarthy,<br />

Alan Mayne, John Stobo, and David C. Hammack, 1995-1996<br />

3 Iacono, AR-Misc p59ff; Bower, 'Leather', pp5-8<br />

4 Steele, AR-Bone p14; Everett, 'Parasites', Sections 4 and 5,pp5-8; Carney, AR-Giass<br />

pp97-99, 115-116, 118; Holmes, AR-Metal p113; Wilson, AR-Ceramics p102.<br />

5 lacono, AR-Misc p73; Wilson, AR-Ceramics p105.<br />

6 Parasite egg-counts cited by John P. McCarthy (Institute for Minnesota Archaeology), H<br />

Urban 14 March 1996. McCarthy reports that 'Analysis of parasite eggs from privy<br />

deposits ... reveals incredible levels of round worm infestation in most eastern cities [of the<br />

United States] into the early 20th century' (H-Urban 7 March 1996). Claire Everett expresses<br />

some reservations about these findings, arguing that the number of people who used the<br />

privies analysed is unknown; pers. com. September 1996. The survival rate of parasite eggs<br />

may also differ on sites in the two countries. Compare also with the residents of Five Points,<br />

New York, who appear to have 'suffered from trichinocis as well as dysentery', Yamin, 'From<br />

Tanning to Tea', p9.<br />

7 Wilson, AR-Ceramics p1 00-101 .<br />

8 Holmes, TR-B pp15-16.<br />

9 Population growth figures cited in Kelly, 'Picturesque and Pestilential'; The 'hidden'<br />

occupants came to light via baptismal and death records, as well as the 1879 Electoral Roll.<br />

10 On yards see Wilson, TR-A pp16, 25; Holmes, TR-B pp12, 16, 18; Carney, TR-C p19;<br />

Iacono, TR-E p12; on drains, see Wilson, TR-A p17; Holmes, TR-8 pp10, 17-19; Carney,<br />

TR-C pp14, 19; Steele, TR-F p9; and TR-G pp11, 12-13; Karskens and Thorp, 'History and<br />

Archaeology in Sydney', p70; see also Thorp, 'Report on Lilyvale'.<br />

11 Clarke, 'Worse than Physic'; Iacono, AR-Misc. p67; Wilson, TR-A p17 (barrel in yard of<br />

126 Cumberland Street); Steele, AR-Bone pp84, 90; Holmes, TR-B p17ff, 24.<br />

12 Peter H. Curson, Times of Crisis : Epidemics in Sydney 1788-1900, Sydney, Sydney<br />

University Press, 1985, pp64, 67, 86, 102.<br />

Karskens, Grace 166