Summer Investor Magazine - St James's Place

Summer Investor Magazine - St James's Place

Summer Investor Magazine - St James's Place

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

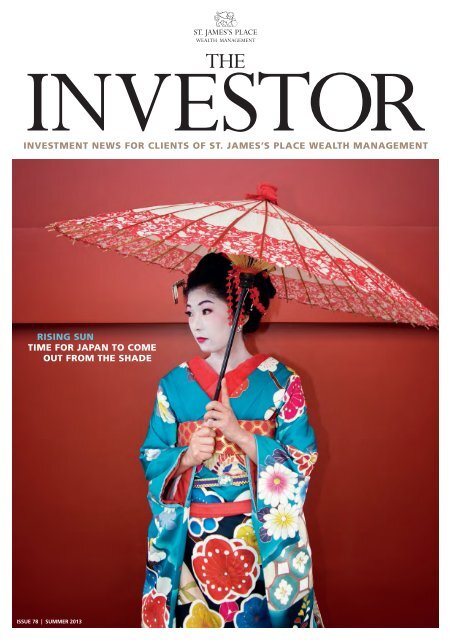

ising suntime for japan to comeout from the shadeISSUE 78 | SUmmEr 2013

analysisanalysisnewsEuROpEausTERiTy plans EnTER ExTRa TimEstock markets buoyant despite additional measuresneeded to boost anaemic economiesUSfed aims to ease the painIt is no exaggeration to say that the most important decision facingthe US Federal Reserve is when, and how, to end quantitativeeasing (QE). The prolonged programme of economic support, whichhas seen more than $2.3 trillion pumped into the US economy inthe past five years, may not have sent growth soaring – the IMF’sprojection for 2013 is 1.9%, well below the average for the decadeprior to the financial crisis – but it has been one of the key factorsin preventing growth slipping even lower.The importance that the markets attach to the QE decision isclear from the reaction to remarks by Fed chief Ben Bernanke inMay, which appeared to hint that an end to the programme wasin sight: the Nikkei in Japan, which has started its own versionof QE, dropped 7% in just one trading day while other Westernmarkets also fell.The uncertainty has also led to a weakening dollar andrising bond yields as investors started to place their bets onhow much longer the QE liquidity dip can last. That has ledto the situation where economic news can be interpreted assimultaneously good, because it shows that the US economy isrecovering; and bad, because a strengthening recovery brings anend to QE closer.Of course, this is likely to be just what the Fed wants. By simplymaking vague hints that the programme will eventually end, the Fedhas encouraged investors to factor its demise into their expectations.That should mean that the impact on markets, when it does finallycome, will be less dramatic: investors can cope with good news andbad, but they deeply dislike the unexpected.How the US economy can continue its recovery without theQE life support will, of course, remain uncertain until it is finallyswitched off.While the US authorities debate when andhow to switch off quantitative easing (QE), inEurope the debate remains focused on whethermore support is needed. The IMF is counsellingan easing of the austerity programme in theUK, while the European Commission is givingsix member states – including France, Spain,Portugal and the Netherlands – extra time tocomplete their austerity plans.Growth across the eurozone does remainanaemic, at best, with the IMF predicting a0.3% fall in output this year, recovering to just1.1% next; in the UK, while we have avoideda triple-dip recession – and revisions to someeconomic statistics suggest we may not evenhave had a double dip – we are hardly enjoyingcOmmOdiTiEsgOld lOsEs iTs sHinERampant over-valuation and rising economic confidence arepossible reasons for a steady decline in the price of goldGold is no longer quite as glittering: havingspent much of the past decade rising steadily 1 ,for much of this year it has been trendingsteadily lower 2 .Just as the rise of gold had no single rationalexplanation, so its decline does not appearto have one simple explanation, with expertsattributing it to everything from rampant overvaluationto a gradual increase in confidenceabout the global economic outlook.It is not just gold: oil and other industrialcommodities have also been weaker this year,1, 2 www.goldprice.org (June 2013)a robust recovery. All the more surprising,then, that the FTSE 100 has managed areasonable performance so far this year, atone point coming within a whisker of its all-timehigh, while Germany’s DAX and the US S&P 500are also near, or at, their peak.But good economic performance is notnecessarily reflected in soaring stock markets– China’s Shanghai Composite Index has beenlacklustre over the past five years, despiterobust economic growth, albeit that the index isdriven less by the fundamental performance ofits listed companies than the equivalent in manyother markets.The disconnect between economies andstock markets reflects three key things. First,investors are forward-looking: they wantto know what company profits will look likein the future and, while Western economiesmay be dismal, markets are relieved that theworst catastrophes – a bankrupt country,or a euro break-up, for example – havebeen avoided.Second, companies have spent the bestpart of a decade cutting costs, reducing theirdebt and seeking out new markets so manyare, in fact, in pretty good health and payingdecent dividends.Third, the vague hint that QE could beending has reduced the attractions ofgovernment bonds, which had been thesafe haven for investors; in the search foralternatives, equities have started to looka bit more attractive.Markets remain nervous and there couldeasily be more stock market hiccoughs tocome, but investors have started to hope thatthe worst is over.in part because of the gradual slowdown inChina’s growth.Unlike gold, the price of these commoditieshas a direct effect on our own economicprospects because they are the raw materialsfor practically everything we buy.Just as a rising oil price fuelled inflation, soits decline and that of other commodities –should they continue to fall – should help tomoderate inflation. And that can only be goodnews for Mark Carney as he takes over asgovernor of the Bank of England.Getty Images04 | the inVestoRTHE inVEsTOR | 05

analysisaNalySISSPECIAL REPORTis the babyboomergenerationlosing itslustre?Ageing parents and cash-strapped children are putting pressureon the finances of the baby boomers, as Heather Connon explains30adults over 50 with a child still living at home3,000,00027 35average age of that childaverage age of first-time house-buyer86 1565 and at least one child basic expenseslife expectancy of manpercentage of people aged betweenpercentage of those supporting anaged 65 in 201340 and 59 supporting a parent overelderly parent who are just meetingGetty ImagesThey are called the ‘babyboomers’ because they wereborn during the post-warsurge in births, but the‘boomer’ epithet couldequally apply to their financial position. Thoseborn between 1945 and 1965 or so look likemembers of a golden generation. They haveenjoyed an era in which unemployment wasrelatively low and jobs for life, often withgenerous final salary schemes, were common;an era of growing home ownership – in 1953,just 32% of people owned their own homes,half the level of 2011 1 ; and an era of surginghouse prices – average prices in England andWales have risen from £5,774 in 1971 tomore than £233,000 in May 2013, notallowing for the effect of inflation 2 .The result is a generation heading intoretirement with significant wealth. DavidWilletts, the Conservative MP who thinks itis time for the baby boomers to give some oftheir wealth back to their children, reckonsthat the over-65s own more than a third of thenation’s £6.7 trillion of wealth and theover-45s more than 80%.But the new age of austerity in the wakeof the financial crisis is rubbing some of thegilt off the boomer generation. Indeed, manyare finding themselves being transformedinto the sandwich generation as they carefor elderly parents as well as continue tofinance their children for far longer thanhas been traditional.The Pew Research Center has carried outextensive research into this phenomenon in theUS. It estimates that, in 2012, 15% of peopleaged between 40 and 59 were supporting aparent aged over 65 and at least one child, upfrom 12% in 2005. There are no similarstatistics for the UK, but it is likely that agrowing number will find themselves in thatposition as the economic squeeze tightens onboth the young and the elderly.Our children are already costingsignificantly more, but are able to contributeless. As from last September, university tuitionfees effectively trebled as the governmentallowed annual charges of up to £9,000. Thosewho choose to support their children, ratherthan leaving them to take out loans, couldtherefore have to find as much as £53,000 infees and living costs for a three-year degree 3 .Even an expensive degree is no guaranteeof financial security, however. Data from theOffice for National <strong>St</strong>atistics shows that, atthe end of 2011, 15% of those who hadgraduated within the previous six years wereunemployed compared with 10% a decadeearlier, while 36% were in low-skilled,and therefore low-paid, jobs compared with27% in 2001.Rising house prices mean children areliving at home for longer. A recent survey bySaga suggested that as many as three millionover-50s had adult children living at home,and the average age of these offspring was27. Indeed, the average age of first-timehouse-buyers is now 35, compared with 28a decade ago 4 . With the average house pricefor the entire UK now almost at £168,000 5 –and substantially more than that in areas suchas London – and mortgage lenders requiringhigh deposits, getting children to leave home islikely to mean parents funding deposits to helpthem to buy their first house. Most lendersnow want deposits of 20% or more, whichmeans £32,000 for the average-priced house.Increasing longevity and the rising costsof social care mean that elderly parents arealso becoming more expensive.A couple of decades ago, baby boomerswould have been looking forward to a healthyinheritance from their parents; these days, thefamily house may need to be sold to pay forthe costs of care home fees and otherexpenses, with one in ten facing a bill of£100,000, according to health secretaryJeremy Hunt in a February statement on socialcare funding.The richer you are, the more likely you areto face these twin costs. The Pew ResearchCenter found that 43% of those with annualincomes of $100,000 (£67,000) or morehave a living parent aged 65 or over and adependent child, compared with just 17% ofthose earning less than $30,000 (£19,000).Being the filling in this sandwich is ratheruncomfortable. The Pew Research Centerfurther found that 30% of those who weresupporting an elderly parent were justmeeting their own basic expenses, and 11%don’t even have enough for that, while only28% felt comfortably off.So it is no surprise that baby boomers’view of retirement is changing. Today’sretirees can expect to live longer than anyprevious generation, with the life expectancyof an average man aged 65 in 2012 now 86,compared with 79 three decades ago 6 .That means a phased retirement is likely tobecome the norm. Indeed, figures for 2011show that more than a fifth of men agedbetween 65 and 69 were still working, upfrom 12% in 1993, according to research bythe Pensions Policy Institute, and evenamong those aged between 70 and 74, thefigure was one in ten.The lesson is clear: far from stealingfrom the next generation, the babyboomers will increasingly find themselvessupporting both the next and previousgenerations. Those who want to avoidthe risks of joining the ranks of theimpecunious should be carefully planningtheir retirement expenditure and the waythey will cover it.1 www.ons.gov.uk (april 2013)2 www.acadametrics.co.uk (may 2013)3 www.lv.com (august 2012)4 www.postoffice.co.uk (september 2012)5 www.nationwide.co.uk (may 2013)6 www.pensionspolicyinstitute.org.uk (april 2012)Balance sheet With high employment and growinghome ownership, baby boomers were seen as thegolden generation. But now, thanks to an ageingpopulation and financial pressure, they find they arehaving to support both parents and children.06 | THE inVEsTORTHE INVESTOR | 07

analysisANALYSISPhilanthropists such asBill and Melinda Gates,Mark Zuckerberg andWarren Buffett areamong the newgeneration of benefactorSPECIAL REPORTThe benefactor can specifyhow he or she wants themoney to be usedAlexandra Loydonhow your givingcan achieve moreYou don’t need the wealth of Bill Gates or Warren Buffettto become a philanthropist, but where do you begin?Corbis,Corbis,GettyGettyImages,Images,RexRexFeaturesFeaturesThe wealthy have a longtradition of philanthropywith today’s generousbenefactors, like Bill andMelinda Gates and LordSainsbury, continuing the traditionestablished by industrialists like JosephRowntree and Andrew Carnegie.Their generosity is on a magnificent scale:the Carnegie Corporation and the JosephRowntree Trust are still funding the samekind of projects more than a century afterthey were originally established, while thesize of the legacies by the Gateses and LordSainsbury – $28 billion so far for the formerand more than £1 billion from the latter– means they are also likely to endure. Buta growing number of those of relativelymore modest means are also keen to leave anenduring legacy through philanthropy, andthey want to be sure that their donations areused to create maximum benefit.The statistics bear out the increasedgenerosity among the moderately wealthy.The Charities Aid Foundation’s (CAF)World Giving Index found that, althoughgeneral consumer giving has fallen globallyduring the economic crisis, from 29.8% oftotal donations in 2007 to 28% in 2011, italso shows that giving by high net worthindividuals has increased.The survey also found that like-for-likegiving among the top 100 philanthropistsin 2012, as measured by the proportionof their total wealth given away in the pastyear, showed a £305 million increase on theprevious year, rising from £1,467 million to£1,772 million.Amy Clarke, head of advisory at CAF,says: ‘In the toughest times you see some ofthe brightest philanthropists step up and dosome incredible things.’Serious philanthropy needs carefulplanning. Recent research by the fiduciarymanagement services company, SEI, foundthat the wealthy are intrinsically generous,driven mostly by the need to give purposeto their wealth. However, many of the200 questioned for the survey would bewilling to give even more – almost twice asmuch – if they were able to move beyondan impulsive approach to a well-consideredgiving strategy.Benefactors who have made their moneyby being professional and organised in theirapproach to their business activities want toexert the same discipline on their charitabledonations so, if they are giving away largeamounts of money, they want to be sure thatit is being used wisely.Alexandra Loydon, head of private clientservice for <strong>St</strong>. James’s <strong>Place</strong>, says manybenefactors prefer to establish a trust orfoundation rather than make direct donationsas this enables them to retain better controlover how the money is distributed and used.‘This has benefits for both philanthropistsand charities. The benefactor can specifyexactly how he or she wants the money to beused, and to invest the money so it can growand provide further funds for distributionto good causes,’ she says. ‘It also enablesmoney to be given to smaller charities orprogrammes which might benefit more fromsmall but regular donations rather than alarge one-off payment.’CAF will help new philanthropists get abetter understanding of what they want toachieve and how to maximise the value ofwhat they do. This starts with identifyingthe individual’s background, includingany health issues, their heritage, familybackground and career.CAF itself does not favour one charityabove another but once a benefactor hasidentified the causes he or she wants tosupport, it will draw up a shortlist ofpotential beneficiaries and do due diligenceto make sure they are delivering on theirpromises. It can also advise benefactors onthe level of impact that charities are achievingwith the money raised, although this is notdone as a standard part of the service.While many of the biggest benefactorshave trusts and foundations bearing theirname, not everyone likes their donations toTHE ST. JAMES’SPLACEFOUNDATION<strong>St</strong>. James’s <strong>Place</strong> has established its ownfoundation with the aim of making asignificant difference in three areas: to thelives of children and young people,combatting cancer, and supporting hospices.The vast majority of funds contributed tothe Foundation come through fundraising ordonations made by the Partners andemployees of <strong>St</strong>. James’s <strong>Place</strong>. These fundsare matched pound for pound by thecompany, and in the past 20 years the<strong>St</strong>. James’s <strong>Place</strong> community has raised anddistributed more than £30 million to goodcauses. To find out more about the<strong>St</strong>. James’s <strong>Place</strong> Foundation visitwww.sjpfoundation.co.ukbe that high profile: one of the key decisionswill be whether to retain anonymity orwhether to use their own generosity toencourage the same behaviour in others.‘We never discuss our private clientsby name, and their trust or foundation canremain anonymous or have a name thatwould not identify them,’ says Clarke. ‘Butmany people like to have their trust namedafter a specific person, or for their foundationto take the family name. If someone hasa brand name, it can be used to galvanisesupport for the causes that they are helping.’The advisory process also enablesbenefactors to work out what kind ofinvolvement they would like. ‘This shouldhelp develop a strong emotional andintellectual connection. This can takeanything from a couple of hours to months,’says Clarke. ‘We have one high net worthindividual who, one year on, is still workingon this. The value of the assets undermanagement is very significant and he reallywants to take care that he gets this right.’Balance sheet Although consumer giving has fallenduring the economic crisis, philanthropic activitiesfrom high net worth individuals are on the rise. A newservice from <strong>St</strong>. James’s <strong>Place</strong> looks to help thosewishing to set up a charitable trust or foundation.08 | THE inVEsTORTHE INVESTOR | 09

ANALYSISANALYSISSPECIAL REPORT20% 70%SINCE SHINZO ABE (RIGHT) TOOK OFFICE LASTDECEMBER, THE PREVIOUSLY OVERVALUED YENHAS TUMBLED BY MORE THAN 20%JAPANESE CONFIDENCE IS RETURNING –DURING THE SAME PERIOD SHARE VALUES ONTHE NIKKEI 225 HAVE SOARED BY NEARLY 70%can abenomics setjapan on the pathto recovery?The new Japanese prime minister is taking radicalsteps to get the economy moving again.Jonathan Gregson assesses his chances of successGetty Images, Rex FeaturesAlmost as soon as he took officelast December, Japan’s primeminister Shinzo Abe set outradical new plans to jolt hiscountry out of nearly twodecades of deflation and underperformance.Known as ‘Abenomics’, this Keynesian-inspiredapproach combines ultra-loose monetarypolicy and quantitative easing (QE) on a scalepreviously undreamt of: a hefty fiscal stimuluspackage of ¥20 trillion (£135 billion), withincreased government spending oninfrastructure and longer-term structuralreforms intended to make Japan’s protectedindustries – from farming to pharmaceuticals– more open and competitive.Abe brought in a new central bankgovernor, Haruhiko Kuroda, who is notconstrained by the old orthodoxies. He haslaunched a monetary stimulus programme ofbuying Japanese government bonds at a raterelative to the size of the economy that is nearlythree times that of the US Federal Reserve.Nearly £1 trillion is to be injected into theeconomy within two years to reverse decadesof deflation and move towards a targeted 2%inflation rate. ‘The hope is to jump-start theeconomy by massively increasing liquidityand channelling new funds into investments,’says Dr Dimitrios Tsomocos at Oxford’sSaïd Business School.After two ‘lost decades’ the Japanese areready for change. Janet Hunter, saji professorof economic history at the London School ofEconomics, points out that such a long periodof deflation, with prices and wages falling inreal terms, has had a profound psychologicalimpact – both on consumers who have beenunwilling to spend and on corporates which,despite banks making credit available, havebeen cautious about borrowing to makefurther investments. Abenomics seems to havechanged all that. Since Abe took office, thepreviously overvalued yen has tumbled morethan 20%, exports and corporate profits havesurged, share values on the Nikkei 225 rosemore than 25% from the start of 2013 tomid-June and consumers have started spendingagain. During the first quarter, the economygrew by 3.35% year on year.The main risk of such drastic reflationarypolicies is that inflation will get out of control.But whereas the Germans are still haunted bythe hyperinflation of the 1930s, Japanese historyteaches another lesson. Professor Hunter says:‘Japan came out of the Great Depression fasterthan any other industrialised nation by followingsimilar policies. The yen was allowed to float andfall by a third against other currencies, and fiscalstimulus was applied earlier.’ The Bank of Japanhad previously tried monetary easing on severaloccasions to reflate the economy, without muchsuccess, as indeed have most other central banksover the past six years. ‘Expansionary monetaryand fiscal policies are fairly conventional thesedays,’ observes professor Hunter. So what’sdifferent about Abenomics?‘In terms of scale, it is dramatic,’ says DrTsomocos. But in terms of what they are doingit is much along the same lines as what the USFed and the Bank of England have implemented.However, he adds: ‘Expansionary monetarypolicy to boost demand does not furnisha sufficient basis for growth by itself.Conventional fiscal stimulus will also beneeded. The macro-economic consequencesof the tsunami still need addressing.’The government is boosting its spending,particularly on infrastructure (includingbridges, tunnels and earthquake-resistantroads), and aims to create an additional600,000 jobs within two years. Given Japan’sageing population and shrinking workforce,which has contracted by 6% in the pastdecade 1 , this necessarily means more jobs forwomen. But, says professor Hunter: ‘Attemptsto draw more women into the workplace aredeeply problematic because the governmentalso wants to redress Japan’s shrinkingpopulation by their having more children.’Abe has also declared that Japan will join theTrans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a proposedregional free-trade agreement being negotiatedbetween the US, Canada, Australia, Mexico,Malaysia, Singapore and others. For Japan,this would mean removing high tariffs onagricultural imports and opening up otherprotected sectors to greater competition.Such reforms are intended to boost Japanesecompanies’ competitiveness – quite apartfrom the weaker yen.For the time being, Abe’s ‘shock and awe’tactics seem to be working – at least politically.Approval ratings have risen to near 70%. Butwith the Bank of Japan printing so muchmoney and actively targeting higher inflation,the once-solid market in Japanese governmentbonds is becoming jittery. Yields have alreadydoubled to more than 0.8% and, with higherstate spending adding to the already hugenational debt (245% of gross domesticproduct), the economy must pick up rapidly sothat stagnant tax receipts increase to preventJapan descending into a debt spiral. ‘Shouldgovernment debt markets get out of control,’says professor Hunter, ‘it would be disastrous.’Supporters of Abenomics argue that it willcreate a virtuous circle. Greater confidence andhigher corporate profits will lead to risingwages, encouraging consumers to spend moreand companies to invest in the future for thefirst time in years. Others point out that higherbond yields will erode the capital adequacy ofJapanese institutions that hold them, includingbanks, and so deter further lending. And theyen’s depreciation is already drawing threatsfrom regional competitors such as China thatthis could trigger currency wars.What is clear is that it is a bold initiative,though not without its attendant risks. ‘At thisjuncture, I wouldn’t worry about hyperinflation,’says Dr Tsomocos. ‘I’d worry aboutrecovery.’ But should things go wrong in Japan– which remains the world’s largest creditornation and ranks third in terms of GDP – theeffects will be felt everywhere.1 blogs.reuters.com/breakingviews (March 2013)All fi gures quoted cover the period December 2012 to May 2013Balance sheet After two decades of stagnation,Japan is ready for change. New prime minister ShinzoAbe has launched a monetary stimulus programme –dubbed ‘Abenomics’ – with the aim of jump-starting theeconomy. But the measures are not without their risks.10 | THE INVESTORTHE INVESTOR | 11

interviewinterviewTrent McMinnintroducingthe thinkerVenezuelan-born sculptor Orlando Salamanca Torres opens his studio doorsand shares his observations of the world. By Heather Farmbroughorlando salamanca torresThe first thing that strikes you when walking into Orlando Salamanca Torres’ studio inSouth East London is a red ladder with a series of small grey men trying to climb itssteps. Every clay figure is different. If they fall, they break. Each is modelled withprecision. There are fewer at the top than the bottom, I observe. ‘Yes, the top is only forthe special people,’ Salamanca Torres jokes. ‘Other people don’t make it.’Some are climbing up boldly, others are scrambling. One man looks sad; he ishunched over, looking at the floor. He is based on a homeless man Salamanca Torres hasseen in Soho. ‘He’s there, but he’s not there,’ explains Salamanca Torres. ‘The ideacomes from the concept of time in our daily lives. We all have a ladder to climb. It’s allabout the rush to arrive somewhere, the hurry.’The next thing that catches your eye is the reclining sculpture of a young manlistening to music on his headphones, his eyes shut. The colour is striking: deep pink,inspired by a trip to India. It lights up the studio and the grey skies outside thewindow. Salamanca Torres has intentionally captured the man’s detachment from hisenvironment. ‘With headphones on, you are in another world,’ he observes. ‘I see peopleon the Tube with their headphones on and they are not aware of what is happeningaround them. When I see young women at 10 or 11 o’clock in the evening walking outof a station completely unaware of their surroundings, I think they are vulnerable. I ask,what are we missing when we detach ourselves from our surroundings?’Salamanca Torres describes his work as a series of postcards, capturing how peoplebehave in cities. ‘Culturally, we are getting more homogenous – that’s globalisation,’ henotes. ‘We wear the same things from city to city; we behave in a similar way. Yet thereality is that we also detach ourselves more and more from our environment.’He was born in Venezuela, but regards London, where he lives with his partner, ashome. He has had a studio at Acme, the largest affordable artists’ studio in London, for13 years. It has no central heating and is freezing, even in summer.Salamanca Torres qualified as an artist at Central <strong>St</strong> Martins College of Art andDesign and as an architect at London Metropolitan University. Everything he makes isunique and although he will use the little grey figures again, it will be in a different way.Each work takes a long time to complete; the ladder and the men took two years.The studio is his shop window – he sells everything he makes. How does he cope withwhat is a very uneven income stream? ‘You build a following of clients over the years,’ hereplies. ‘You have to have a group of works that are in evolution. You don’t have a goodmonth and a bad month; you have a good year and a bad year. It’s about planning.’A friend of Salamanca Torres’ partner recommended <strong>St</strong>. James’s <strong>Place</strong> in 2007 andhe has been a client ever since. ‘You have to manage whatever you have and you have tohave a professional and non-emotional portrayal of what is happening economically andfinancially. You need to have someone with a cool head and to be very aware of the facts.I think <strong>St</strong>. James’s <strong>Place</strong> is very good at that. You develop a sense of trust with your<strong>St</strong>. James’s <strong>Place</strong> partner; mine is Nick Cummins.’Salamanca Torres pays particular attention to building up his pension. ‘You have toplan well, especially as an artist. In other countries, artists have far more support – notentirely financially, but with legislation that developers have to include art in theirdevelopments, and investment in art in public spaces and that kind of thing.’He is a careful listener and thinks very deeply about issues; he welcomes debate butis reluctant to impose his own views. In this sense, he is ideally suited to his profession.‘Once you are in this profession one of the first things you have to do is to learn toobserve. The difficult part is trying not to take sides. I am very cautious of makingstatements that influence people. I am just someone who is reflecting what I see andother professions could probably benefit from that kind of lateral thinking.’INFOprINcIpal EXhIbITIONs2013‘View from the Tip of the Dog’sNose’, Royal Opera Arcade,London1998‘Hands in the Forest’ installation,Barrandov <strong>St</strong>udios, Prague1995‘Unknown’, The London Groupbiennial Open, Barbican, London1994‘Movimiento’ combinedexhibition, The ArchitecturalAssociation Gallery, London1994Cohn and Wolfe Exhibition,London – first prize for sculpturewith ‘1+1=1’Peak 201312 | tHe inve<strong>St</strong>OrNEXTtHe inve<strong>St</strong>Or | 13

ANALYSISANALYSISan engaging way toboost performanceThe financial crisis has sparked pressure for shareholders to take a more active role inthe companies they own. Anthony Hilton looks at what this might mean in practiceHistory tells us that stockmarkets came into beingbecause people withbusiness ideas neededsomewhere to find peopleprepared to back them. <strong>St</strong>ock markets were theplace where they met and where otherwise-idlecapital was put to work in search of profit.But history also tells us that the worldmoves on and when professor John Kaypublished his report into the workings of theequity markets last year – commissioned bybusiness secretary Vince Cable – he concludedthat stock markets are no longer about raisingcapital. These days, companies finance most ofwhat they want to do either out of retainedprofits or by borrowing. He suggested,therefore, that the primary focus of a stockexchange today was corporate governance.The stock market provides a mechanismthrough which shareholders can gain access tomanagement, monitor their performance and,if necessary, gee them up a bit.This was what the government wanted tohear because one of its central themes is theneed for British business to become morecompetitive. The hope was that shareholderpressure would spur managements to raisetheir game. It was also defensive. Thegovernment wanted to know why shareholdershad not sought to rein in bank managements inthe months leading up to the financial crash,stopping banks from over-reaching themselvesand therefore avoiding the ensuing disaster.Shareholder activism is nothing new. Morethan 20 years ago Alastair Ross Goobey, theman then running the British Telecom pensionfunds, was an early convert to shareholderengagement. He felt that sellingunderperforming shares was not really anoption for him because his fund was simplytoo big to exit a holding easily. If an investmentdisappointed he really had to do somethingabout it, so he pioneered working withmanagements to change strategy, boost profitsand add value that way.Engagement means different things todifferent people. For some shareholders,engagement is about ensuring that theapproved board structures are in place: thatthe roles of chairman and chief executive areseparate, the key committees of the board havecredible leaders, and so on. The idea is that ifthe control structures are right, then thebusiness should be all right – and it is aplausible argument, though not bulletproof.It failed with the banks because they weretoo big and too complex for their boardsto understand what was going on.For other shareholders the correct boardand governance structures are taken as a given.What they also want is to understand thethrust of corporate strategy, to challenge whatthey do not like and to be convinced that thecompany has the necessary management indepth to execute what the board decides.Then there are some who say they simplydo not have the expertise to challengemanagement, or that it is not financiallyworthwhile – that the costs of engagementoutweigh the benefits, even if it does result inan improvement in the share price. But thebiggest hurdle of all from a UK perspective isthat around half of UK shares are now inforeign hands – held, for example, by overseasfund management groups or sovereign wealthfunds, and they really do not want to getinvolved in the nitty-gritty that effectiveengagement requires. It is possible that thiswill be addressed by the new overarchingshareholder committee, which has beenadvocated by professor Kay as a way forshareholders to voice concerns and agreea co-ordinated course of action againstunderperforming management teams.Despite all these obstacles, there isgrowing evidence that shareholders havebecome less passive and more demanding inrecent times. They have been more willing toblock mergers where they did not like thestrategy, as with the British and continentalEuropean defence giants, BAe and EADS, ordemand a better deal, as with Glencore’sacquisition of Xtrata. They have pressedmanagement teams to shed underperformingbusinesses and to return cash to shareholders,and most of all, they question the value ofmanagement and levels of remuneration.Activists such as Knight Vinke have shown howwell-researched criticisms can shake up eventhe mighty HSBC.Confident management teams, for the mostpart, welcome the increased shareholder interest– though not perhaps the ousting of AndrewMoss at Aviva, Sly Bailey at Mirror Group andDavid Brennan at AstraZeneca last year, andSir John Bond at Glencore earlier this year, all ofwhich marks the end of shareholder passivity.We all get complacent from time to timeand need a kick to spur us on. Managementteams are no different; so more prodding fromshareholders must be a good thing, not just forthose being prodded, but for anyone with aninterest in the stock market. The better Britishbusiness performs, the better for all of us.Balance sheet Shareholder activism is nothing new,but there is evidence that shareholders are becoming lesspassive and more demanding. Management teams arecoming under scrutiny to raise their performance, whichcan only be a good thing for the stock market.Gallery <strong>St</strong>ock14 | THE INVESTORTHE INVESTOR | 15

ANALYSISanalysisSPECIAL REPORTThe annual globalconsumption ofluxury goods (€bn).Source: Bain &Company andAltagamma20092010201120120 50100 150 200 250rising abovethe recessionThanks to demand from emerging markets, luxury brandscontinue to prosper in tough economic conditions.Helen Power examines the sectorAlamyFor the past two decades, luxurygoods, an industry dominated bylong-established European andNorth American brands, hasbeen a runaway growth story.According to figures from Bain & Companyand industry body Altagamma, luxury goodsconsumption has grown every year since1995, with the exception of 2003 and 2009.In 2010, when the West remained mired inrecession, global luxury goods consumptiongrew by 13%, and by more than 10% in thesubsequent two years as emerging marketconsumers, anxious for a slice of the Westerndream, made up the difference. Greater China(mainland China, Hong Kong, Macao andTaiwan), with its double-digit GDP growthand burgeoning middle class, was the realengine of that expansion.So with this Far Eastern desire forWestern luxury goods in mind, it wastherefore surprising when China’s first ladyaccompanied her husband on a state visitto Moscow dressed head to toe in homegrown,logo-free couture.With consumers in Europe – still luxury’sbiggest market – also counting their centsamid widespread austerity in 2013, PengLiyuan’s sartorial choice left observerswondering about whether the luxury goodsindustry could continue to register suchhealthy growth.Some experts believe that China isentering a new phase. Claudia D’Arpizio,a partner at Bain & Company, whichproduces regular reports on the luxurymarket, says Chinese ‘gifting’ – a longstandingcorporate tradition that hasbolstered the luxury market – has been hitby a government anti-corruption campaign.Bain predicts that growth in luxury goodsspending in Greater China will now slowfrom 30% in 2011 to 7% this year.Others, however, think the Chinesedragon still has some way to go. <strong>St</strong>uartMitchell, founder of specialist fund managerS. W. Mitchell Capital, argues that theslowdown in gifting was linked to theuncertainty created last year when Chinaappointed its new government.‘Over the election period it was unclearwho to encourage with gifts,’ he says. ‘Nowthat all the junior positions are in place, youknow whose palm you need to cross withsilver. Gift-giving is so deeply ingrained inChinese culture, it’s not going to disappearsimply because growth slows a little. I thinkChina will always want Western brands.There are a number of quite nice domesticbrands in China now, but they cost just 10%of the price of the Western brands.’Gift-giving is soingrained in Chineseculture, it’s not goingto disappear becausegrowth slowsChina’s growth may be slowing, but witha forecast of 7.75% this year, it is still veryhealthy. Its population of 1.4 billion, and thegrowth of a middle class keen to demonstrateits increasing wealth through Western labels,mean the appetite for Western luxury goodsshould not wane significantly.Mitchell believes that if growth slowsin Greater China, other regions will pick upthe baton – a theory supported in the recentreport on the luxury goods market byBain & Company and Altagamma, whichare forecasting global growth of 4-5%for the sector this year. Waning Chineseinterest, they say, will be compensated forby booming South-East Asian nations such asMalaysia and Indonesia, steady growth in theMiddle East and South America, anda resurgent US luxury consumer.But many experts are predicting apolarisation of consumer attitudes,with true luxury still booming whilebrand-based businesses, which rely moreon being fashionable than top quality, willbegin to struggle. ‘There is a fatigue ofthe logo business. Aspirational consumersare shifting to more accessible luxury andpremium [quality] brands, which are alsobenefiting from the rise of a new middleclass,’ says D’Arpizio.As the middle classes in emerging marketsbecome more established, they are alsolikely to become more discerning about thebrands they choose. That is already reflectedin the fact that some of the more high-fashionbrands, and particularly those based mainlyon clothing, are suffering. One example isclothing group Hugo Boss, while Mulberry,the English maker of womenswear andhandbags, has also warned that its profitswill be hit by cutbacks among its franchisepartners in Asia.Mitchell is backing the quality materialsstratum of the market, although he continuesto believe high-end leather goods will remainin demand. ‘Hermes and [Louis] Vuitton makeabout 50 per cent return on equity. The bestof the best is Hermes – a beautiful companyand the family manage it with a really carefuleye,’ he says.‘A company like Hermes is particularlyimpressive in the way it prepares the marketfor entry. In China it was done in a careful,well-organised way, whereas others have beenpushing for all-out growth at the expense ofthe cachet of the brand.’Overall, the waxing and waning of youngerbrands and a maturing Chinese customer-baseseem unlikely to diminish the central appealof luxury. ‘At the end of the day, people wantthe real thing,’ says Mitchell. ‘The allure ofluxury, when people start to make a bit ofmoney, is huge. They see European brands andwant to be part of that international club ofsuccessful people, and that’s not over.’Balance sheet Despite the global recession, luxurygoods appear resistant, with emerging markets suchas China fuelling their continued growth. But withconsumers becoming more discerning, some of the lessdesirable brands could face a period of struggle.16 | THE INVESTORTHE inVEsTOR | 17

IN YOUR INTERESTIN YOUR INTERESTwhere there’s a will,there’s a wayLeaving a will is becoming even more essential following changes inthe rules about inheritance. Neasa MacEerlean explainsLaws governing familyinheritances are in a state offlux as legislators try to keepup with new trends. For allof us, it means we need to makesure we leave robust wills.Most of us appear to be leaving ourlegacies to the vagaries of inheritancelegislation. According to the LawCommission, some two-thirds of people inGreat Britain have not made a will. Whensomeone dies without a valid will, his orher estate is divided in accordance with theintestacy rules.Under these regulations the estate isdistributed mainly between spouses, civilpartners, children, parents and siblings. Butthe application of these rules can result inconsiderable injustice in individual cases –leaving money to estranged husbands andwives, ignoring needy children and, in somecases, going to the Crown rather than friendsand relatives.Many people, especially the young, willfeel that their assets are so insignificant thatthey do not merit the effort of making a will.The vast majority of us have children –according to the Office for National <strong>St</strong>atistics,80% of women have had a child by the ageof 45 – and wills are the ideal vehicle forplanning their care and wellbeing shouldwe die young, and for ensuring they inheritaccording to our wishes.If someone dies without leaving a validwill in England and Wales, the first £250,000of the estate goes to the spouse or civilpartner. If there are children, then the spousegets a ‘life interest’ in half the remainder,which means they receive the income onthe assets, but cannot touch or control thecapital. In Scotland, the threshold went upfrom £300,000 to £473,000 in February2012 and Scottish widows and widowerscan get up to another £118,000 in furniture,home contents and other assets. Thereare various formulae written into the law,depending on whether the person is marriedor in a civil partnership, and has children.Putting up the Scottish threshold to£473,000 is clearly of help to spouses orcivil partners. However, it also means thatsurviving children will lose out.In England and Wales, the governmentpublished a draft Inheritance and Trustees’Powers Bill in March, through whicha spouse or civil partner would get their halfof the remainder of the estate, after thefirst £250,000, to invest and spend asthey wished, without the ‘life interest’restriction. This could leave the survivormuch better off, but again could diminishwhat is left over for children.Anyone who wants to take care of theirindividual family members, rather thanleaving the division of their assets to theluck of the draw in a changing legal system,should, therefore, make sure they leave a will.But that will needs to be carefully drawn up,especially if there are previous marriages orother complications.For instance, another change that isplanned south of the border is reform ofthe Inheritance (Provision for Family andDependants) Act for the first time since it wasintroduced in 1975.Fay Copeland, head of the private clientteam at London-based solicitor, Wedlake Bell,explains that this law enables cohabitees ofmore than two years’ standing, and peoplewho can claim that they were ‘financiallymaintained by the deceased’, to make claimson wills from which they have been excluded.The reform will make this type of claim‘easier’, she says. In Scotland, however,claims on wills are altogether more difficultto make. David McIndoe, Glasgow-basedprivate client partner in law firm HarperMacleod, says: ‘It is very difficult to overturna properly constructed will in Scots law.’There are provisions in Scots law thatoverrule any wills that exclude spouses andchildren, but apart from that, competentlycomposedwills should stand.In England and Wales, however, litigation– often from disenfranchised children –is ‘increasingly common’, according toCopeland. ‘I am seeing a huge increase incases,’ she says.‘As asset values have fallen [in theeconomic downturn], there is less to goaround and people are inclined to fightto protect what they consider they areentitled to.’A way to reduce the likelihood of litigationis to attach a ‘letter of wishes’, she says –especially if one child is to receive a largerinheritance than another.‘Without such an explanation,’ shecontinues, ‘children will see this as theirparent’s last word and will assume it meansthey were regarded or loved less’, and thatwill lead to upset and, possibly, to the lawcourts. Drawing up a robust will can take daysof thought and discussion, but it could saveyears of pain and litigation.If you would like more information onwills and inheritance planning, please contactyour <strong>St</strong>. James’s <strong>Place</strong> partner.Balance sheet Some two-thirds of people in GreatBritain have not made a will. But with litigation fromdisenfranchised children increasingly common – andfollowing changes to inheritance legislation – drawingup a robust will can save years of pain.Plainpicture18 | THE INVESTORTHE INVESTOR | 19

Together,we can turn yourgood intentionsinto exceptionaloutcomesWe recognise the importance of charitable giving;the new <strong>St</strong>. James’s <strong>Place</strong> Philanthropy Service can helpyou make a difference to the causes you care aboutFor more information, please contact your <strong>St</strong>. James’s <strong>Place</strong> Partner

AWARD-WINNINGWEALTH MANAGEMENT EXPERTISE2013 WEALTH ADVISER‘BEST PRIVATE CLIENTMANAGER UK’WINNER2013 FT/INVESTORS CHRONICLE‘BEST WEALTH MANAGER FORTAX EFFICIENT INVESTMENTS’WINNER2013 CITY OF LONDON‘WEALTH MANAGEMENTCOMPANY OF THE YEAR’WINNERWe are delighted to have won these awardsTHANK YOU TO EVERYONE WHO VOTED FOR USUK members of the <strong>St</strong>. James’s <strong>Place</strong> Wealth Management Group are authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.The ‘<strong>St</strong>. James’s <strong>Place</strong> Partnership’ and the titles ‘Partner’ and ‘Partner Practice’ are marketing terms used to describe <strong>St</strong>. James’s <strong>Place</strong> representatives.<strong>St</strong>. James’s <strong>Place</strong> Wealth Management Group plc Registered Office: <strong>St</strong>. James’s <strong>Place</strong> House, 1 Tetbury Road, Cirencester, Gloucestershire, GL7 1FP.Registered in England Number 4113955.