Neither Here Nor There

Neither Here Nor There

Neither Here Nor There

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Table of ContentsIntroductionWar in the BalkansBosnia-HerzegovinaSerbiaWorld War II to 1992 - Fueling the Balkan WarBosnian RefugeesUnited Nations FailureDayton Peace AccordsBosnia-Herzegovina FlagBosnian ElectionsInternational Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP)The International Criminal Tribunal for the former YugoslaviaSummaryResourcesQuestions to ConsiderWhat You Can Do3444577788889910112

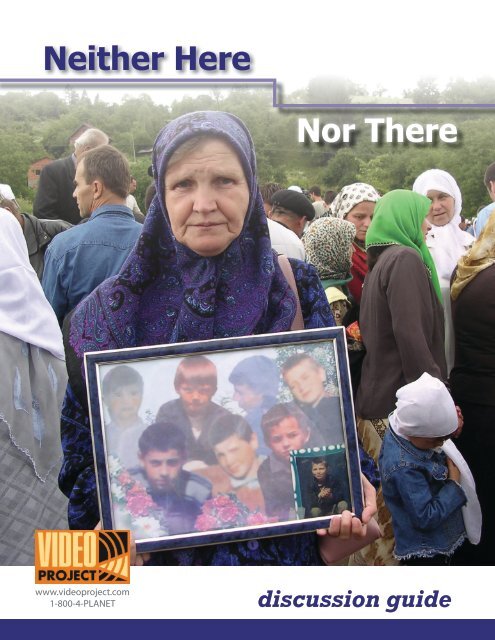

Introduction<strong>Neither</strong> <strong>Here</strong> <strong>Nor</strong> <strong>There</strong>is an intimate portrayal ofthe Selimovic family fromSrebrenica in Eastern Bosnia,who resettled in Columbia,Missouri after the fall of the former United Nations “safe area” that resulted in Europe’sworst massacre since World War II. The story follows a Bosnian War widow, FatimaSelimovic, and her family living in the heartland of America and still searching for home.Filmed over a three-year period, <strong>Neither</strong> <strong>Here</strong> <strong>Nor</strong> <strong>There</strong> traces the complexities ofstarting over in a new place when ties to the past remain unbreakable.In July 1995, more than eight thousand Muslim men and teenage boys were murderedin the small town of Srebrenica, Bosnia during a five-day period by Bosnian Serbs. Sincethen, Missouri has become home to the largest Bosnian population outside of theirhomeland, which includes approximately 60,000 Bosnians refugees living in St. Louis,Mo. Having survived one of the bloodiest battlegrounds of the Balkans and the massexecution of their family and friends, Fatima Selimovic and her family find themselvesstruggling to resettle in a peaceful middle-class college town.Fatima works as a house keeper at the Holiday Inn and her teenage daughter worksnights, full-time at a book factory while attending high school by day. Her oldestdaughter is hoping her husband can join their family in the U.S. Meanwhile, she mustbe the single parent to their one-year old son. The past comes back to haunt the familywhen Fatima learns that her father is identified in a mass grave in Bosnia. The film followsthe family back to their homeland for the first time to bury her father at a mass funeralin Srebrenica. Fatima’s father, including 600 newly-identified remains, are buried at thememorial, which is attended by thousands of mourners, including world leaders.<strong>Neither</strong> <strong>Here</strong> <strong>Nor</strong> <strong>There</strong> is an example of the strength of women and an intimate portrayalof the U.S. refugee program. The Selimovic’s story is told from the viewpoint of thefilm’s co-director, also a refugee caseworker, as she tries to help the family become selfsufficient.Would it be better if Fatima and her children stayed in Bosnia? Or, is Americatruly the land of opportunities? Sometimes a refugee’s home is neither here nor there. It’ssomewhere in-between.Produced by Refugee Films - www.refugeefilms.org3 3

War in the Balkans(1992-1995)Excerpts from Center for Balkan DevelopmentThe former Yugoslavia consisted of six republics,including Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia,Slovenia, Macedonia, Serbia, and Montenegro.As Communism collapsed in the 1980’s, EasternEurope looked for solutions to provide economicand political stability in a post Cold War world.Serbia’s Communist Party leader, SlobodanMilosevic, began pandering to Serb nationalism,and through his control of the state-run media, hebecame the most powerful figure in Yugoslavia.During the Balkan Wars of the 1990’s, four of therepublics declared independence while Serbia andMontenegro remained part of Yugoslavia. In 2006,Montenegro and Serbia declared independence,ending their union and the last remaining vestigesof the former Yugoslavia.Bosnia-Herzegovina(pre-war population 4.4 million): Bosnia has the most complex mix of religious traditionsamong the former Yugoslav republics: 44% Bosniaks (Muslims), 31% Bosnian Serb(Eastern Orthodox), and 17% Bosnian Croat (Roman Catholics). Bosnian Muslims areSlavs who converted to Islam in the 14th and 15th centuries after the Ottoman Empireconquered the region. From World War I until the end of the Cold War, Bosnia was part ofthe newly-created country of Yugoslavia. Bosnia declared independence in March 1992.Serbia(including Kosovo and Vojvodina with pre-war population 9.8 million): This republic isthe largest and most populous. Sixty-six percent are ethnic Serb of traditionally EasternOrthodox religion. Until 1989, Serbia also had two autonomous regions,” Kosovo andVojvodina. Kosovo, bordering Albania, was the historic seat of a traditional Serbiankingdom and the site of the famous Battle of Kosovo in 1389, when the Serbs wereconquered by Ottoman forces. Today, Kosovo’s population is 90% ethnic Albanian, mostof them Muslims. In 2008, Kosovo’s Albanian leadership declared independence fromSerbia, which is recognized by many members of the United Nations, including the U.S.Still, the process of the UN General Assembly adopting a formal resolution is on-going.China and Russia have indicated they would veto membership of Kosovo.4

World War II to 1992 – Fueling the Balkan WarDuring World War II, armed groups claiming allegiance to various ethnic factionsfought against each other and against the Nazi occupiers. By 1945, almost one millionYugoslavs had lost their lives, most of them at the hands of other Yugoslavs. Croatianfascists (Ustashe) were the most notorious for killing Serbs, Jews, Gypsies, Communists,and political opponents, but Serb Chetniks were also responsible for many mass killings.The Communist-led Partisans fought against both groups and were victorious (withAllied support) at the war’s end. The Partisan leader, Josip Broz (Tito), ruled the countryas a one-party socialist state. Despite using repressive tactics and centralized control,Tito understood the importance of apportioning power evenly among the Yugoslavethnicities and he kept the peace. Under Communist rule, it was a serious crime to openlyexpress ethnic aspirations of any kind.After Tito’s death in 1980, the nation slid into economic and political decline as acollective leadership began to squabble over power and the allocation of shrinkingresources among the republics. With the final collapse of Communism in the 1980s,Serbia’s Communist Party leader, Slobodan Milosevic, quickly became the unchallengedruler of Serbia. One of Milosevic’s first acts was to change Serbia’s constitution andvoid the autonomy of Kosovo. He began a campaign of repression against the ethnicAlbanian Kosovars, making him a hero in the eyes of Serb nationalists throughout theformer Yugoslavia.Milosevic’s attempts to seize control of the federal government and his repressivetactics in Kosovo drove the newly elected non-Communist governments of Slovenia,Croatia, and Bosnia to seek independence. The Yugoslav National Army (JNA) respondedwith brutal attacks supported by Serb nationalist militias in Croatia and Bosnia. Ironically,when the war began in Croatia in 1991 and Bosnia in 1992, many Croats and Bosniansthought the Yugoslav National Army would protect them. They soon learned that thenational army --the fourth largest in Europe --was clearly in the hands of Milosevic andbeing used to create Greater Serbia.5 5

In March 1992, Bosnia’s Muslims and Croats called for a referendum for Bosnianindependence. Fierce propaganda from Serbia, depicting Muslims as extremistfundamentalists, caused many Bosnian Serbs to support Milosevic’s plan for ethniccleansing as a means of creating Greater Serbia. Since the Bosnian Serbs did not inhabita single specific territory in Bosnia and lived alongside Muslim and Croat neighbors,the stage was set for war throughout the country. On April 6, 1992, the Bosnian Serbsbegan their siege of Sarajevo. Through three cold winters, Sarajevans dodged sniperfire as they collected firewood, searched for food, and tried to get to their jobs. Morethan 12,000 residents were killed, 1,500 of them children.Throughout Bosnia, Bosnian Serb nationalists and the Yugoslav National Army begana systematic policy of genocide to establish a “pure” Serb republic. They drove out allother ethnic groups by terrorizing and forcibly displacing non-Serbs through directshelling and sniper attacks. Entire villages were destroyed. Thousands were expelledfrom their homes, held in detention camps, raped, tortured, or summarily executed.Those on the outside watched passively as multi-ethnic communities were violentlytorn apart. While ordinary Bosnians suffered and died for months that turned to years,opportunities to effectively intervene were greatly ignored by Europe and abroad.6

United Nations FailureThe failure of the UN to stop the killing in Bosniaseriously harmed its credibility. When Sarajevocame under attack by Serb artillery in April 1992,the UN forces pulled out to avoid casualties,leaving behind only a small and lightly armedcontingent of peace-keepers to discourageattacks by Serbian nationalists.Bosnian RefugeesFew people could have predicted that the warwould last for almost four years, and with suchbarbarism. More than 200,000 Bosnians out ofa population of 4.4 million were killed. Some200,000 were injured, 50,000 of them children.Millions of people were deported or forced to fleetheir homes. Sixty percent of all houses in Bosnia,half of the schools, and a third of the hospitalswere damaged or destroyed. Power plants, roads,water systems, bridges, and railways were ruined.Throughout these horrors, the internationalcommunity failed to respond. It resulted in theworst case of genocide in Europe since WWII.The United Nations declared a “safe-zone” of theEastern Bosnian town of Srebrenica to be underpeace-keeping protection of poorly-equippedDutch soldiers. By July, 1995, Srebrenica easilyfell to Bosnian Serb militias. Within a week,8,000 Bosnian Muslim civilian men and boys inthis “safe zone” were murdered. The world learned of the atrocities through the courageousefforts of print and TV. Wrenching scenes were broadcast around the world showing hundredsof emaciated men and women behind barbed wire with their eyes hollow from hunger anddespair. Following the massacre of Srebrenica, a NATO (<strong>Nor</strong>th Atlantic Treaty Organization)bombing campaign against the Army of the Republika Srpska helped bring the war to an end.Dayton Peace AccordsThe Dayton Peace Accords, signed on December 14, 1995, by Presidents Milosevic,Izetbegovic, and Tudjman, carved Bosnia into two autonomous and ethnic-based entities,separated by a demilitarized zone. Despite their unbridled aggression, the Serbs, in controlof the Republika Srpska, received 49% of the territory of Bosnia. The Bosnians were grantedthe remaining 51% of the country, called the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, anuneasy alliance of Bosnian Muslims and Croats. Each entity has its own government,military, and police. A central government handles banking and foreign policy. Most non-Serbs have been cleansed from Serb-held areas and are not welcome or safe to return totheir homes. The same is true for many Serbs who have left Federation-controlled territories.77

Bosnia-Herzegovina FlagBosnian ElectionsAlthough elections after the war were held to select a three-member presidency(a representative of Croats, Bosniaks, and Serbians) and a national parliament, mostinternational observers claim there was widespread voter fraud and intimidation. Thepolitical system set-up after the Dayton Peace Accords was meant to be a short-term fix.Still, this flawed system exists today, well more than a decade later.International Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP)ICMP was established to support the Dayton Peace Agreement. Its primary role is toensure the cooperation of governments in locating and identifying those who havedisappeared during armed conflict or as a result of human rights violations. SinceNovember 2001, ICMP has led the way in using DNA as a first step in the identification oflarge numbers of persons missing from war. ICMP has developed a database of relativesof missing people, and bone samples taken from human remains exhumed from massgraves in the countries of former Yugoslavia. By matching DNA from blood and bonesamples, ICMP has been able to identify more than 15,000 people who were missingfrom the Bosnian War. In addition to its work in the Balkans, ICMP is involved in helpinggovernments in various parts of the world to establish effective identification systems inthe wake of conflict or natural disaster.The International Criminal Tribunal for the former YugoslaviaThe United Nations Security council establishedThe International Criminal Tribunal for theformer Yugoslavia in 1993. Based in The Hague,the Netherlands, it has announced indictmentsof hundreds of individuals, including formerYugoslavian President Slobodan Milosevic,excused of genocide and crimes againsthumanity during the war. In 2006, the formerSerb leader died of a heart attack in prisonbefore a verdict was reached in his five-yearlong trial. Today, many war criminals have notbeen brought to justice and are in hiding, andthere has been a lack of will by the internationalcommunity to push for their arrest.8