Children - Terre des Hommes

Children - Terre des Hommes

Children - Terre des Hommes

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

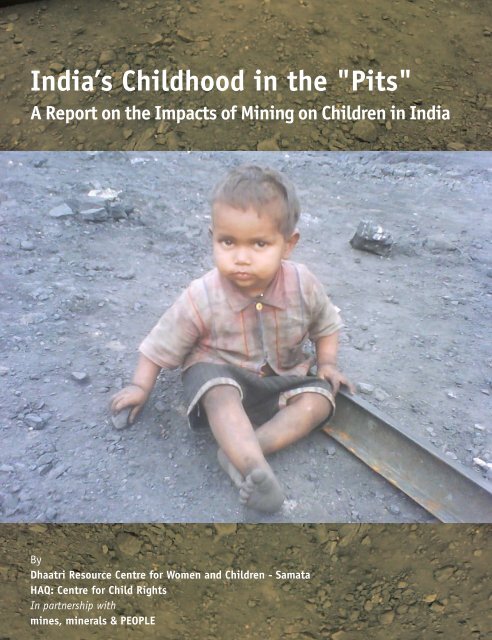

India’s Childhood in the "Pits"A Report on the Impacts of Miningon <strong>Children</strong> in Indiai

iiPublished by:Dhaatri Resource Centre for Women and <strong>Children</strong>-Samata, VisakhapatnamHAQ: Centre for Child Rights, New DelhiIn partnership with: mines, minerals & PEOPLE,Supported by: <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong> Germany, AEI & ASTM LuxembourgMarch 2010ISBN Number: 978-81-906548-4-5Any part of this report can be reproduced with permission from the following:Dhaatri - Samata,14-39-1, Krishna Nagar,Maharanipet, Visakhapatnam-530002Email: samataindia@gmail.comHAQ:Centre for Child RightsB1/2 Malviya NagarNew Delhi-110017Email: info@haqcrc.orgwww.haqcrc.orgCredits:Research Coordination:Field Investigators:Documentation Support:Bhanumathi Kalluri, Enakshi Ganguly ThukralVinayak Pawar, Kusha GaradaRiya Mitra, G.Ravi Sankar, Parul ThukralReport: Part 1-Part 2-Enakshi Ganguly Thukral and EmilyBhanu Kalluri, Seema Mundoli, Sushila Marar, EmilyDesign and Printing:Aspire Design

iiiAcknowledgementsThis report, called, India’s Childhood in the ‘Pits’: The Impacts of Mining on <strong>Children</strong> in India, had its beginnings in thefact-finding exercise that the organisations involved in this research had undertaken in April 2005. Had it not been for thechildren we met then, we would never have known how deeply affected they are by mining. We thank the children of Bellaryfor opening our eyes to the problems of mining affected children.The core focus of this report is the primary data and information gathered from the mine sites and communities affected bymining. The organisations that directly helped us are Santulan (Maharashtra), Sakhi (Karnataka), Mine Labour ProtectionCampaign (Rajasthan), Pathar Khadaan Majdoor Sangh (Madhya Pra<strong>des</strong>h), Ankuran (Orissa), Gangpur Adivasi Forumfor Socio-Cultural Awakening (Orissa), Swaraj Foundation ( Jharkhand), Jan Chetna (Chhattisgarh) and Grameena VikasaSaradhi & MASS (Andhra Pra<strong>des</strong>h). Additionally, organisations including READS (Karnataka), SEEDS (Karnataka),Don Bosco (Karnataka) and Lutheran World Service (Orissa) provided extra support with data collection. Individually,we received help for organising our field visits or in accompanying us to the field from friends and activists like Mr. Kumar(Kolar), Mr. Dayanidhi Marandi, Mr. Santosh Kumar Das, Mr. Niladri Mishra, Mr. Samit Carr, Mr.Vijay Kumar, Mr.Kishore Kujur and Mr. Naveen Naik. We thank all the member organisations of mm&P alliance that helped us withundertaking field research in the eight states that were covered for the case studies.This report would not have been possible without the financial support of <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong> (tdh) Germany, AEI &ASTM Luxembourg. We thank them for giving priority to this issue <strong>des</strong>pite several constraints. We particularly appreciatethe support from Ravi and George Chira of tdh, Germany during the process of the study and for their inputs in review andfinalisation of the report.This report is dedicated to all the children of India — dalit, adivasi and marginalised children driven out of their lands, childmine workers working in the most hazardous conditions, all children living around mine sites braving bulldozers and copingwith the inhuman conditions they are pitted against in order for India to compete as a global contender for economic andpolitical power.Most of all, we wish to thank the research team and the administrative teams of Samata and HAQ for their highly motivatedwork all through the study.We thank Rukmini Sekhar for her yeo-woman support in copyediting the national report in such a short time. NishantSingh and Sukvinder Singh for not saying NO even as it seemed impossible to <strong>des</strong>ign and print the report in the time wegave them.We hope this report will help put the “mining child” on the national agenda and ensure that some attention is paid tothem.Bhanumathi KalluriDhaatri-SamataEnakshi Ganguly ThukralHAQ:Centre for Child Rights

ivList of AbbreviationsAEI – Aide à l’Enfance de l’IndeANM – Auxiliary Nurse cum MidwifeARI – Acute Respiratory IllnessASER – Annual Status of Education ReportASTM – Action Solidarite Tiers MondeAWC – Anganwadi CentreBCCL – Bharat Cooking Coal LimitedBGML – Bharat Gold Mines LimitedBHEL – Bharat Heavy Electricals LimitedBIFR – Board for Industrial and Financial ReconstructionBPL – Below Poverty LineBPO – Business Process OutsourcingBRC – Block Resource CoordinatorBSL – Bisra Stone Lime Company LimitedCCL – Central Coalfields LimitedCHC – Community Health CentreCICL – Child in Conflict with LawCMPDI – Central Mine Planning and Design InstituteCNCP – Child in Need of Care and ProtectionCSE – Centre for Science and EnvironmentCSR – Corporate Social ResponsibilityCu m – cubic metresCWSN – <strong>Children</strong> With Special NeedsDISE – District Information System for EducationDP camp – Displaced Persons’ CampECL – Eastern Coalfield LimitedEIA – Environmental Impact AssessmentFDI – Foreign Direct InvestmentFIR – First Information ReportFPIC – Free Prior and Informed ConsentGAFSCA – Gangpur Adivasi Forum for Social and CulturalAwakeningGDP – Gross Domestic ProductGSDP – Gross State Domestic ProductHa – hectareHAL – Hindustan Aeronautics LimitedHDI – Human Development IndexHIV/AIDS – Human Immunodeficiency Virus/AcquiredImmuno Deficiency SyndromeICDS – Integrated Child Development SchemeIIPS – International Institute for Population SciencesILO – International Labour OrganizationIMR – Infant Mortality RateIPEC – International Programme on the Elimination of ChildLabourIT – Information TechnologyKGF – Kolar Gold FieldsKMMI – Karignur Mineral Mining IndustryLWSI – Lutheran World Service IndiaMASS – Mitra Association for Social ServiceMCL – Mahanadi Coalfields LimitedMDGs – Millennium Development GoalsMLPC – Mine Labour Protection Campaign.mm&P – mines mineral and PEOPLEMMDR Act – Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation)ActMP – Madhya Pra<strong>des</strong>hMW – MegawattNACO – National AIDS Control OrganisationNALCO – National Aluminum CompanyNCLP – National Child Labour ProjectNCRB – National Crime Records BureauNFHS – National Family Health SurveyNGO – Non–Governmental OrganisationNIOH – National Institute for Occupational Health and SafetyNMDC – National Mineral Development CorporationNREGA – National Rural Employment Guarantee ActNSSO – National Sample Survey OrganisationOBC – Other Backward ClassesPAP – Project Affected PersonsPDS – Public Distribution SystemPHC – Primary Health CentrePIO – Public Information OfficerPKMS – Pathar Khan Mazdoor SanghPOSCO – Pohang Iron and Steel CompanyPSSP – Prakrutiko Sampado Surakshya ParishadREADS – Rural Education Action Development SocietyR&R – Rehabilitation and ResettlementRs – RupeesRTI – Right to InformationSAIL – Steel Authority of India LimitedSCCL– Singareni Collieries Company LimitedSC – Scheduled CasteSDP – State Domestic ProductSEEDS – Social Economical Educational Development SocietySEZ – Special Economic ZoneSGVS – Society of Gram Vikasa SaradhiSHG – Self Help GroupSOP – Superintendent of Planning and ImplementationSq km – square kilometresSTD – Sexually Transmitted DiseaseST – Scheduled TribeTB – TuberculosisTDH – <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong>UAIL – Utkal Alumina International LimitedUCIL – Uranium Corporation of India LimitedUSA – United States of AmericaVRDS – Vennela Rural Development SocietyVRS – Voluntary Retirement Schemes

Table of ContentsAbout the Study 3Mining <strong>Children</strong> — Intoroduction and Overview 5Part I 13National OverviewPart II 45State Reports1. Karnataka 472. Maharashtra 653. Rajasthan 794. Madhya Pra<strong>des</strong>h 935. Chhattisgarh 1036. Jharkhand 1157. Orissa 1278. Andhra Pra<strong>des</strong>h 165Part III 177Summary and RecommendationsPart IV 189Appendix- Our Experience with Right to Information ActAnnexuresa) Tables 199b) Glossary of Terms 205

3About the StudyThis study has been conducted jointly by HAQ: Centrefor Child Rights and Samata in close partnership with thenational alliance, mines, minerals and People (mm&P)network and Dhaatri Resource Centre for Women and<strong>Children</strong>, and supported by <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong> Germany(tdh), AEI & ASTM Luxembourg. The work follows onfrom an earlier fact-finding mission that was carried out inthe iron ore mines of Bellary district, Karnataka. As well asbeing the first study to cover these issues in a comprehensiveway, the study aims to form the basis for mobilisationand advocacy on this issue. We hope that, along with themm&P network, we will be able to take forward this workand to campaign to bring real improvements in the lives ofchildren affected by mining in India.This report aims to cover the three phases of mining — preminingareas (where projects are being proposed and landneeds to be attained), current mining areas (where mining isalready taking place) and post-mining areas (where miningoperations were significant but have now ceased).Field research was carried out in eight states to cover arange of different mining situations, as well as a range ofminerals being mined in India today. The states coveredwere: Karnataka, Andhra Pra<strong>des</strong>h, Maharashtra, MadhyaPra<strong>des</strong>h, Rajasthan, Orissa, Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand. InOrissa we undertook case studies in a number of differentsites as Orissa is a state most impacted by mining and hasbeen the focus of further mineral expansion.MethodologyThis report is compiled from a combination of informationgathered in the field and from secondary data. The sites forfieldwork were chosen to ensure a range of minerals, bothminor and major minerals, were covered as well as a widegeographic space. One of the most important factors wasthe presence of a local organisation or an mm&P partner.This was a priority for two reasons, to secure local supportwith the research, and to ensure that local groups willtake the campaign forward and use the study as a basis formobilisation and advocacy in their states.Not all background data was available through Censusstatistics or in other public domains. Therefore, the decisionwas made to use the Right to Information (RTI) Act togather missing information. RTIs were sent to a numberof government departments, including state-owned miningcompanies, to find out the number of children working inmines, the number of people displaced by projects, varioushealth statistics for people living in these districts and otherinformation that is not readily available. (See end of Part 2for responses to RTIs filed).The main methodology used for field case studies wasto understand the overall development indicators of thechildren living around the mines while also identifying thechildren working in the mines, the nature of their work andworking conditions and how their social life is impacteddue to the external influences of the complex ad hoccommunities of workers, truckers, contractors, traders andother players who form an amorphous and unscrupulousfloating population around the mines. This was done throughvisits to villages, schools, anganwadi centres, primary healthcentres, orphanages, company run schools and hospitals,meetings with panchayat leaders, village elders, women’sgroups, workers’ unions, local officials and NGOs, as well asvisits to the mine sites.

4List of states and districts visitedChallengesOver the course of the research, the study team faced anumber of challenges.The first challenge was the choice of sites. A first list ofsites based on choice of minerals, location and presence ofan mm&P partner organisation was made. However, someof these sites had to be later dropped, either due to a lack ofadequate information or lack of capacity of the partner toprovide the necessary support.This was a time-bound research project. That meantthat the project period coincided with the monsoons,which rendered some of the mining sites originally choseninaccessible.Despite seeing the overall impact of mining on their lives,communities were not always able to identify those thatdirectly impacted children only. Since this study focussedon the impacts on children, this proved a major challengefor the team. It is difficult even for local organisationscampaigning on rights of mining affected communities toprovide tangible data with respect to children as impacts andproblems are not directly visible on children. Althoughlocal groups are knowledgeable about the presence of childlabour and other issues, threats from mining and politicalpowers make it dangerous for them to directly confront thestate on issues concerning children.Mining operations are politically sensitive and highlypoliticised making it difficult to collect information relatedto children and mining because of the sensitive nature of thisissue. People were nervous to talk, as they feared negativeconsequences. In terms of direct access, it is always difficultto get the opportunity to talk to children first-hand andthis is certainly the case with regard to mining. Researcherswere cautious to approach children at mine sites, in case ofrepercussions for these children. When communities wereinterviewed in their villages, it tended to be the elders whowere most vocal in answering questions. In addition to this,primary health centres were unable to provide quantitativedata on illnesses or diseases. Schools, where they existed,as in many other parts of the country were often withoutteachers present at the time of the fieldwork. Therefore, thedifficulty in collecting quantitative data and figures meantthat we only managed to get indicative information aboutthe impacts of mining on children.Non-availability of secondary information was yet anotherchallenge. Applications under the Right to Information Actwere filed to get relevant information. However this did notprove easy. To be able to get information under the RTIAct, 2005, it is critical to send the application to the rightperson. Interestingly this experience itself proved to provideimportant learning in the context of the study.About this reportThis report combines both secondary data as well asprimary data. It has been presented in two parts. Part I is thenational overview which aims to provide a summary of thehuge quantity of data obtained during field research. Part IIconsists of state reports based on both secondary informationabout the state and its mining activities as well as case studiesfrom mining sites where field work was undertaken. Part IIIis summary and detail reccommendation and Part IV is theappendix that details our experience with using the Right toInformation Act for this study.

5Mining <strong>Children</strong> —Introduction and OverviewIndia is endowed with significant mineral resources. Theconstant endeavour of humans to mine more and moreresources from the earth has been going on for centuries.Metals, stones, oil, gas and even sand are all mined. Indeed,steel, aluminium and other plants have come to be a symbolof progress and industrial growth, while fossil fuels and coalare mined for our ever-increasing need for energy. Every timea mining operation begins, it is with promises of growth anddevelopment, yet these promises are rarely delivered.Mining has, throughout history, been a symbol of thestruggle between human need and human greed; thehuman need to dig into the earth and take control over itsresources. Industry, infrastructure and investments have beendecisively stated as basic vehicles to drive India into this race,which automatically translates into mineral extraction andprocessing being of utmost importance to implement thisdream. Further, development visions are based on certainpremises built into public thought processes. The first of thesepremises is that mining brings economic prosperity at alllevels of the country — national and local. It has been basedon the principle that the high revenues generated by miningactivities will convert poverty stricken and marginalisedcommunities and workforce into economically groundedcommunities with positive developments in employmentgeneration, health, education, local infrastructure and thecreation of a diversified opportunity base.Overview on Mining fuel minerals, 11 metallic, 52 non-metallic and 22 minorminerals (such as building stones). Mining for fuel, metallicand non-metallic industrial minerals is currently undertakenin almost half of India’s districts. 1 Coal and metallic reservesare spread across Madhya Pra<strong>des</strong>h, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand,Orissa, Maharashtra and Andhra Pra<strong>des</strong>h. Iron ore depositsare located in Orissa, Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand in thenorth, and Goa and Karnataka in the south. Limestone isfound in Himachal Pra<strong>des</strong>h in the north, to Andhra Pra<strong>des</strong>hin the south and from Gujarat in the west to Meghalaya inthe east. In terms of mineral deposits, Jharkhand, Orissa andChhattisgarh are the top three mineral bearing states. 2The contribution of the mining and quarrying sector to 3 However, the demandfor metals and minerals in India and in other developingcountries has led to a steady growth in the country’s mineralindustry. preceding period and with the global recession hitting India,the mining and quarrying industry was the only segment ofthe economy not to experience steep deceleration of growthrates. 5 However, what needs to be remembered is that interms of the galloping Indian economy, mining makesonly a marginal contribution.In the 2008 National Mineral Policy, the governmentrecognises that:“As a major resource for development, the extraction andmanagement of minerals has to be integrated into the overallstrategy of the country’s economic development. The exploitationof minerals has to be guided by long-term national goals andperspectives.”1. Centre for Science and Environment, “Rich Lands, Poor People,” State of India’s Environment: 6, 2008, pp. 3,2.3.Ibid.Ministry of Mines, Annual Report, 2008-2009, pp. 10.4. U.S. Geological Survey, 2007 Minerals Yearbook: India, pp. 11.1.5. Rediff.com, India’s GDP falls to 6.7 per cent in FY09, http://business.rediff.com/report/2009/may/29/bcrisis-indias-gdp-falls.htm, 29 May, 2009.

6However, closer observation of the current mining sectorreveals that mineral production is being viewed by boththe central and state governments as a means of short-termrevenue generation and to fuel current economic growthrates, as opposed to being considered holistically as partof the country’s wider, more long-term development goals,human development indicators and preservation of theenvironment and other natural resources such as water.With the new economic policy in India, there have beena number of changes in the mining sector. Althoughtraditionally in the hands of the public sector, there has beenincreasing privatisation and more mines are now privately owned. Foreign directinvestment has been a thrust area for the sector, with boththe central and state governments pushing for liberalisationand deregulation in not only the Coal Nationalisation Actand labour laws, but also in other related areas such as theenvironment. It has also impacted employment due to theenforcement of Voluntary Retirement Schemes (VRS) onmine workers. The Fifth Scheduled Areas, areas which areconstitutionally demarcated for tribal populations, arebeing opened up for foreign direct investment and privateindustries, primarily mining, leading to deforestationand displacement of tribals. Most alarmingly, there hasbeen a huge increase in the informal sector mining activitiesthrough sub-contracting mining and quarrying.But mining is not the subject of this study. This studyis about the relationship between children’s rights andmining. It attempts to address the question — what isthe impact of mining on children? According to the mostrecent Indian Census carried out in 2001, children constitutemining areas. These we refer to as “Mining <strong>Children</strong>” in thisreport.A fact-finding study in 2005 in the iron ore mines ofHospet in Bellary District, Karnataka, for the first time,brought home to the organisations involved in this study,the immense impact mining has on the lives of children. Itbecame imperative to follow that fact-finding study with amore systematic research to gain a better understanding.India boasts of several legal protections for children, withthe Right to Education being the latest fundamental right.These laws are strengthened by positive schemes to bringchildren out of poverty and marginalisation. The paradoxof mining lies in the fact that the mining industry orthe mining administration is not legally responsible forensuring most of the rights and development needs ofchildren. The mess that is created in the lives of children asa result of mining is now addressed by other departmentslike child welfare, education, tribal welfare, labour andothers, which makes for an inter-departmental conflictof interest and leaves ample room for ambiguities in stateaccountability. In this process, the child is being forgotten.Hence, the glaring heart-rending impacts of mining onchildren have technically few legal redressal mechanisms tobring the multiple players to account.While there is some documentation and research availableon the impact of mining on communities in general, apartfrom scattered and anecdotal information, very littleinformation is available on the impact of mining on childrenin all its dimensions. Research on mining and children hastended to focus solely on the aspect of child labour, whichagain is restricted to minerals that are normally exportedand have the potential to shock the western consumer. Themultitude of other ways in which children are impactedby mining have been completely neglected. Needless tosay, neither the groups and campaigns that focus on miningissues, nor those working with children, have paid this issuethe attention it <strong>des</strong>erves.This report provi<strong>des</strong> but a glimpse into the lives of childrenliving, working, affected by and exploited by mining in India.We hope that the microcosm of children we touched throughthis report evokes a national reflection on what could be theplight of millions of children affected by mining in India.It is hoped that this report will yet again bring to nationaldebate the paradox of “India’s inclusive growth” that stillignores the majority of children. When national sentimentsare stirred by the rhetoric of children being the future of ournation, it is important to assess for ourselves whether ourdevelopment models are actually geared towards creating afuture for India’s children, or are instead, providing a nationwith little present or future for the majority of our children.It therefore asks the question, “How do we as a nation wantto measure ourselves as achieving human development?”This study shows how the development aspirations createdby our policy makers and political leadership create a stronglikelihood for future divi<strong>des</strong> between the children of thiscountry, furthering both the socio-economic divide and theurban-rural divide. Among the adivasi and dalit children,the displacement, impoverishment and indebtedness caused

7by mining and its ancilliary activities shows a dearth ofopportunities for them to access even basic rights such asprimary education and healthcare. That they are being forcedto take on adult economic roles in the most exploitativeconditions in order to help their families survive, is certainlynot an indicator that sets us on track to achieve theMillennium Development Goals (MDG) goals emphasisedin the 11th Five Year Plan especially for these social groups.This paves the route to socio-economic disparities in India’schildren.This study also shows that children and their communitiesare not part of the growth and development that miningpromises. For example, it is over 30 years since the NALCOmining project, a public sector undertaking in the KoraputDistrict of Orissa began. In these 30 years, the data from thecase study reveals that there has been little upward mobilityfor the children of affected families, either educationally oreconomically. This is the fate of those affected by a publicsector project where social responsibility is intended tobe the principal agenda. There does not appear to be asingle mining project that has fulfilled the rehabilitationpromises in a manner that has improved the life of affectedcommunities nor have they set a precedent for best practicesthat the government can set as a pre-condition to privatemining companies. Moreover, there has been no assessmentor stock taking of the status of rehabilitation especially withregard to the status of children.The findings from this study provide a strong reason for anurgent comprehensive assessment of the status of childrenin mining areas — children of mine workers as well as oflocal communities, child labour engaged in mining and thestatus of the institutional structures for them. It also callsfor addressing the glaring loopholes in the law, policy andimplementation related to mining in general, and privateand small scale/rat hole mining in particular that are relatedto children, to develop guidelines for migrant labour and theun-organised sector and pre-conditions that need to be fixedbefore mining leases are granted. Foremost is the need forstrengthening protection mechanisms for children andcampaigns against child labour in these regions.What is the Definition of a“Child”?A key challenge for child rights work in India is the confusionaround the definition of a child in terms of age. The UNConvention on the Rights of the Child, which was adopted “every human being below the age of 18.” Indian legislationalso makes 18 years the general age of majority in India. However, other laws passed in India cause confusion inthis area, with many laws defining childhood as only up tillbanned from working in hazardous occupations, whichinclu<strong>des</strong> mining and quarrying, for this purpose, a child isbetween 15 and 18, there is no applicable regulation. This has also been witnessed with the passing of the all but no such guarantee exists for children 15 and above.As organisations committed to the rights of all childrenin India, in this study, HAQ and Samata will considerthe impacts of mining on children up to the age of 18years. However, there are serious limitations in terms ofstatistics, as the majority of statistics, such as the Census2001, only calculates the number of working children up tillLaw And PolicyInternational StandardsThe UN Convention on the Rights of the Child inclu<strong>des</strong> therights for children to be protected from hazardous work.<strong>Children</strong> have the right to be protected from economicexploitation and from performing any work that is likely tobe hazardous or interfering with the child’s education, or tobe harmful to the child’s health or physical, mental, spiritual,moral or social development. The Convention also recognisesthe right of the child to education and requests State Partiesto take measures to encourage regular attendance at schoolsand the reduction of dropout rates, which is a frequentproblem among working children.6. Ministry for Women and Child Development, Definition of the Child, http://wcd.nic.in/crcpdf/CRC-2.PDF, uploaded: 10 August 2009.7.Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, 1986.

8In addition, almost all work performed by children in miningand quarrying is hazardous and considered to be one of theworst forms of child labour, defined by the Worst Forms of 8 India has notratified this convention, and indeed activists and campaignsagainst child labour too are not in favour of ratifying aconvention that distinguishes between hazardous and nonhazardousforms of labour. Their argument is that all formsof labour or indeed, work that denies children their basicrights, is exploitative and hence hazardous, and hence mustbe banned.Mining leads to forced evictions. adopted by the UN Committee for Economic Cultural andSocial Rights on Forced Evictions encourages State Partiesto ensure that “legislative and other measures are adequate toprevent and if appropriate, punish forced evictions carried outwithout appropriate safeguards by private persons or bodies.” National Laws and PolicyThe Constitution of India, along with a whole host of lawsand policies, recognise and protect the rights of all childrenrecent National Plan of Action for <strong>Children</strong> 2005, alongwith the Eleventh Five Year Plan, lay down the roadmap forthe implementation of these rights. These include the rightsto be protected from exploitation and abuse and the right tofree and compulsory education. These laws are strengthenedby positive schemes to bring children out of poverty andmarginalisation. But then these are for all children. Very fewlaws provide any protection or relief to mining childrenin particular or address their specific situation. Thisis because the principal job of the Ministry of Mines isto mine. Hence, many of the violations and human rightsabuses that result from mining, especially with respectto children, are not the mandate of the mines ministry toaddress. The responsibility lies elsewhere, and thereforeleads to conflict of interest between departments, in whichthe child falls between the cracks.In the laws that deal with mining, many do not addressthe needs and rights of children, or even human beings ingeneral. For example, there are several laws and policiesthat govern mining in the country, 10 which include centralas well as state laws and policies. There are also policiesand laws that deal with rehabilitation and resettlement ofthose displaced by the mining project, 11 as well as policesfor specific minerals such as coal. 12 Although people are themost affected, directly or indirectly, when mining operationstake place, most of these laws and policies that deal withmining mention little or nothing about people except aslabour.Not surprisingly, children find absolutely no mention,although they may lose access to education, healthcareand other facilities; be affected by pollution and otherenvironmental impacts; be pushed into joining the labourforce and end up unskilled and illiterate forever as a resultof mining.Child labour is one of the most vicious impacts of miningthat one sees. However, laws to address the employment ofchildren in such hazardous conditions are weak. The Child(underground and underwater) and collieries (SchedulePart A). It also prohibits employment of children in certainmining related processes listed in Schedule B. 13 This is ahuge gap in the law because it does not unilaterally banemployment of children in all mining, thereby leaving themvulnerable to abuse and exploitation. Even while prohibitingthe employment of children in mines, the Mines Act leavesopen a window of opportunity for exploitation. While thelay down that no person below 18 years of age shall be8.9.10.11.12.13.The worst forms of child labour comprises, inter alia, work which, by its nature or the circumstances in which it is carried out, is likely to harm the health,safety and morals of children.For more information see A Handbook on UN Basic Principles and Guidelines based on Development–based Evictions and Displacement by Amnesty InternationalIndia, Housing and Land Rights Network and Youth for Unity and Voluntary Action. http://www.hic-sarp.org/UN%20Handbook.pdfSuch as the Mines Act, 1952 (Amendment Act 1983); Mines And Minerals (Development And Regulation) Act, 1957 (As Amended Up To 20th December, 1999);Government Of India Ministry Of Mines National Mineral Policy, 2008 (For Non - Fuel And Non - Coal Minerals); as well as state polices such as KarnatakaMineral Policy 2008.National Policy for Rehabilitation and Resettlement, 2007.There are a number of acts and policies which specifically govern the coal industry in India. For further details, see: http://coal.nic.in/acts.htm, and http://policies.gov.in/department.asp?id=76.Mica-cutting and splitting; manufacture of slate pencils (including packing); manufacturing processes using toxic metals and substances, such aslead, mercury; fabrication workshops (ferrous and non-ferrous); gem cutting and polishing; handling chromite and manganese ores; lime kilns and limemanufacturing; stone breaking and crushing; etc.

9in any operation connected with or incidental to any miningIt also leaves it to the discretion of the Inspector to determinewhether the person is a worker or apprentice/trainee andone line under its section on infrastructure developmentthat “a much greater thrust will be given to development ofhealth, education, drinking water, road and other relatedfacilities…”, failing to mention who will do it and how.The law that can be most effective in dealing with childlabour in mining as well as any other form of vulnerabilityarising out of mining, is the Juvenile Justice (Care andProtection) Act 2000, Amended 2006, which defineschildren as persons up to the age of 18 and deals with twocategories of children — the Child in Need of Care andProtection (CNCP) and the Child in Conflict with Law(CICL). Section 2d defines a child in need of care andprotection as one who is exploited or abused or one who isvulnerable to being abused or exploited. It inclu<strong>des</strong> childrenalready or vulnerable to displacement and homelessness,trafficking, labour etc.Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation)and use of minerals in a “scientific” manner. This is the primaryAct, which is slated for amendment, concerned with miningin India under the National Mineral Policy framework.The rules laid under this Act mainly relate to mine planning,processes of mining, the nature of technology, proceduresand eligibility criteria for obtaining mining leases and allaspects related to mines. It does not give any reference tothe manner in which mining is to take place, from thesocial context, except for some broad guidelines in termsof environment, rehabilitation and social impacts. Giventhe huge negative impacts of mining on children, specificpre-conditions should be clearly laid out prior to grantingof mining leases, where mining companies have to indicateconcrete actions for the development and protection ofchildren. In order to undertake responsible mining, unlesssome of the following social impacts and accountability,particularly, with regard to children, are incorporated withinthe Act and the Mine Plan, violation of children’s rights willcontinue in mining areas.not become an Act. As with all generic laws and policies,there is no special recognition accorded to children exceptto mention educational institutions as part of social impactassessment and orphans in the list of vulnerable persons. It says that while undertaking a social impact assessment take into consideration facilities such as health care, schoolsand educational or training facilities, anganwadis, children’sparks 15 etc. and this report has to be submitted to an expertgroup in government, which must include “the Secretary ofthe departments of the appropriate government concernedwith the welfare of women and children, Scheduled Castesand Scheduled Tribes or his nominee, ex officio.” 5(2b).In a letter to the Minister for Rural Development, theChairperson of the National Commission for Protectionof Child Rights had pointed out that a review of the statusof children in areas of displacement due to developmentprogrammes as well as disaster and conflicts, shows thatmost rehabilitation programmes do not take into accountthe impacts on children. Because displacement can lead toa violation of rights of children in relation to their accessto nutrition, education, health and other facilities, it callsfor an impact assessment on children and their access toentitlements. This has to be gender and age specific. The National Rehabilitation and Resettlement Policyneglects to mention children as affected persons andtherefore fails to recognise or acknowledge the ways inwhich children are specifically impacted by displacementfor any project including mining. Impacts on children aredifferent from those on adults. Yet no mention is made inthis policy of the effect this displacement will have on theiraccess to food, education and healthcare, as well as theiroverall development.14.In Section 21(2-iii and iv) it states that vulnerable persons such as the disabled, <strong>des</strong>titute, orphans, widows, unmarried girls will be included in the surveyas also families belonging to Scheduled Castes and Tribes15. 4 (2) “While undertaking a social impact assessment under sub-section (1), the the appropriate government shall, inter alia, take into consideration theimpact that the project will have on public and community properties, assets and infrastructure; particularly, roads, public transport, drainage, sanitation,sources of drinking water, sources of water for cattle, community ponds, grazing land, plantations, public utilities, such as post offices, fair price shops, foodstorage godowns, electricity supply, health care facilities, schools and educational or training facilities, anganwadis, children’s parks, places of worship, landfor traditional tribal institutions, burial and cremation grounds.”16. National Commission for Protection of Child Rights, Infocus, Volume 1.No. 4

10Impacts<strong>Children</strong> are affected directly and indirectly by mining.Among the direct impacts are, the loss of lands leadingto displacement and dislocation, increased morbiditydue to pollution and environmental damage, consistentdegeneration of quality of life after mining starts, increase inschool dropouts and children entering the workforce.The indirect impacts of mining, often visible only after aperiod of time, include a fall in nutrition levels leading tomalnutrition, an increase in diseases due to contamination ofwater, soil and air, and increased migration due to unstablework opportunities for their parents.It is paradoxical that while mining is touted as heraldingprosperity and growth and if it is meant to bring in a betterlife, then why is this not visible in the lives of local people– men women and children – whose lands are beingmined, or who have been brought there as labour to minethe lands?“MINING HAPPINESS FOR THE PEOPLE OF ORISSA”promises one mining company. “STEEL IN EVERY STEP,SONG IN EVERY HEART” promises another. Yet why thenare people affected by mining asking, “the governmentis telling us that this mining is going to be profitable tothe country and that this is for India’s development...But if this is India’s development, are we not a part ofIndia? Why is the government not considering us?”Sources:1. Mining company signboards in Orissa.2. Person about to be displaced for lignite mining project, BarmerDirect and Indirect Impacts of Mining on <strong>Children</strong>1. Increased morbidity and illnesses: Mining children are faced with increased morbidity. <strong>Children</strong> are prone to illnessbecause they live in mining areas and work in mines.2. Increased food insecurity and malnutrition: While almost 50 per cent of children in many states across the country aremalnourished, mining areas are even more vulnerable to child malnutrition, hunger and food insecurity.3. Increased vulnerability to exploitation and abuse: Displaced homeless or living in inadequate housing conditions,forced to drop out of schools, children become vulnerable to abuse, exploitation and being recruited for illegal activitiesby mafia and even trafficking.4. Violation of Right to Education: India is walking backwards in the mining affected areas with respect to its goalof education for all. Mining children are unable to access schools or are forced to drop out of schools because ofcircumstances arising from mining.5. Increase in child labour: Mining regions have large numbers of children working in the most hazardous activities.6. Further marginalisation of adivasi and dalit children: Large-scale mining projects are mainly in adivasi areas and theadivasi child is fast losing his/her Constitutional rights under the Fifth Schedule, due to displacement, land alienationand migration by mining projects. As with adivasi, children it is the mining dalit children who are displaced, forced outof school and employed in the mines.7. Migrant children are the nowhere children: The mining sector is largely dependent on migrant populations wherechildren have no security of life and where children are also found to be working in the mines or other labour as a resultof mining.8. Mining children fall through the gaps: <strong>Children</strong> are not the responsibility of the Ministry of Mines that is responsible fortheir situation and the violation of their rights. The mess that is created in the lives of children as a result of mining hasto be addressed by other departments like child welfare, education, tribal welfare, labour, education and others. Withoutconvergence between various departments and agencies, the mining child falls through the gaps. All laws and policiesrelated to mining and related processes do not address specific rights and entitlements of mining children.

RecommendationsSpecific for children ecognise that children areimpacted by mining in a number of ways, and theseimpacts must be considered and addressed at all stages ofthe mining cycle pre-mining, mining and post- mining in all laws and policies on mining- National MineralPolicy 2008; the Mines and Minerals (Developmentand Regulation) (MMDR); Mines (Amendment) Act, governance structure are the responsibility of severaldepartments in the State and Ministries in the Centre, itis essential to ensure convergence both in law and policylevel, as well of services to ensure justice to the miningchild.institutions the National Commission for Protectionof Child Rights as well as the State Commissionsfor Protection of Child rights with children affectedby mining and the establishment of a state level anddistrict level monitoring committee consisting of allthe concerned departments that have responsibilities toprotect the child responsible for monitoring as well asgrievance redressal. denial regarding the existence of children in labourin mines and amend the laws accordingly. Given theextreme hazardous nature of the activity, the Mines Act,amended to ensure that children below 18 years of ageare not working in the mines as trainees and apprenticesfrom the age of sixteen. The lacunae in the Child Labour to children working in mines must be addressed byamending the law to include all mining operations inSchedule A of Prohibited Occupations. policies, amendments to the existing laws on miningand those that are being proposed by the respectiveministries, whether with regard to the RehabilitationBill, the Social Security Bill, the Land Acquisition Bill,to name a few.hunger and food insecurity in mining areas, as has beenfound in this study and in keeping with the SupremeCourt Orders in the Right to Food Case 18 through stocktaking and implementation of ICDS projects in miningareas.migrant, adivasi and dalit mining children receive specialattention. abuse that mining brings to children, the governmentmust prioritise the implementation of its flagship schemeon child protection called the Integrated Child protectionScheme (ICPS) on vulnerable areas such as the miningareas. The aim of the scheme is to reduce vulnerability asmuch as to provide protection to children who fall out ofthe social security and safety net.to address the condition of the children in the miningareas in a manner relevant to their specific situationsthrough the provision and strengthening of protection,monitoring and grievance redressal mechanisms orsupport structures for protection of mining childrensuch as the Child Welfare Committees.way) by the Juvenile Justice Boards, the Child WelfareCommittees (CWCs) and the State Juvenile PoliceUnits to adivasi children in areas where displacementand landlessness has led to their exploitation or broughtthem in conflict with law. and Universal Compulsory Elementary Education isa right for all children through the targeted provisionof accessible and quality education, the same as thatavailable to the children of the mining officials. Number,quality and reach of primary and elementary schools,including infrastructure and pedagogic inputs, have tobe adequately scaled up.be extended to all children working in mines, whichmeans it must be upgraded substantially in terms ofnumbers, financial allocations and quality of deliveryas well as monitoring and ensure mainstreaming of allchildren attending NCLP schools into regular schools1117.18.At present mining and collieries are the only forms of mining included in Schedule A.Ibid.For details see- http://www.righttofoodindia.org/icds/icds_orders.html (accessed on 13 March 2010)Interviews with mining-affected communities, Kasipurdistrict, Orissa, June 2009.

12is mandatory and this must be ensured from childrenrescued from labour in mines. health impacts on children living and working in miningareas and considering the high levels of environmentalpollution and occupational diseases as a result ofmining the Ministry needs to have delivery servicesthat will address critical child health and mortalityissues, especially related to pollution, contamination,toxicity, disappearance of resources like water bodiesthat have affected the nutrition and food security of thecommunities, etc. agreement and the Rehabilitation Plan should clearlyspecify the impacts on and plans for children which mustbegin before the mining project begins in a time-boundmanner. This inclu<strong>des</strong> decent and adequate housing withtoilet and Potable drinking water, good quality schoolswithin the rehabilitation/resettlement colony, electricity,anganwadi centre with supplementary nutrition topregnant women and single mothers, colleges, healthinstitutions, roads and transport. result in the cancellation of the lease. Penalties should bedefined for non-implementation of rehabilitation as perprojected plans and assessments with recommendationsmade by the monitoring committee.caused to children and their environment in the existingmines with a clear time frame which will be scrutinisedby the independent committee at regular intervals asagreed upon. The clean up should also state the budgetallocated by each company for this purpose and providedetails of expenditure incurred, to the committee. established so that it is not restricted to immediateshort term monetary relief, but should show longterm sustainability of the communities and workers,including post-mining land reclamation and livelihoodprogrammes that have measurable outputs. A sharefrom the taxes or profits shared by the companies shouldbe ploughed into institutions for children.clean up and institutional mechanisms are in place. Noprivate mining leases should be granted in the ScheduledAreas and the Samatha Judgement should be respectedin its true spirit. Sector which is proposing the new Social SecurityBill should take into cognizance, the above legal andpolicy recommendations, particularly with respect tothe migrant mine workers and include adequate socialsecurity benefits that directly support development andprotection of children.Overarching Recommendationsappropriate local governance institutions (district, block)and the community with clarity in terms of quantity andquality of ore that will be extracted, the extent of areainvolved, demographic profile of this region, economicplanning for extraction that inclu<strong>des</strong> number of workersrequired, nature of workers (local, migrant), type oftechnology, social cost including wages, estimate ofworkers and assured work period, providing (in the caseof migrant workers) residential facilities like housing,basic amenities like drinking water, electricity, earlychildhood care facilities, quality of education, toilet, PDSfacility and other requirements for a basic quality of life.The resources for these must not be drawn upon frompublic exchequer but recovered from the promoter.first clean up the situation and redress the <strong>des</strong>truction

Part INational Overview13

15National OverviewMining has impacts on people at different stages in itsdevelopment. By its very nature it is fundamentallyunsustainable, as all natural resources are finite and willeventually run out. Mining obviously has the most impactson people working in the sites, but the local community isalso impacted in terms of health problems and other negativeinfluences the activity may introduce or exacerbate in theregion. In the pre-mining phase, communities are displacedfor mining activities and they may lose their farmland oreven their homes.The length of the active mining phase depends on thequantity of minerals available in the area. But eventually allmines have to be closed. The post-mining phase also posesits own distinct problems. Mining companies very rarelydevelop adequate closure plans, to put in place mechanismsto protect the community once mining ceases. Mining andquarry sites are often simply abandoned by companies oncethe minerals have dried up, and this land is generally useless,as it cannot be easily transformed back into agriculturalland. Therefore the local community is often left landlessand jobless.Working conditions are very different in the formal andinformal mining sectors. The average daily wage for workers Theywill often receive other benefits, such as paid holidays andsometimes healthcare and education for their families.Hazards/ risks in the living environmentTable 1.1: Hazards and riskd in the general mining environentExposure to:subhuman living conditions (lacking sanitation,drinking water, extreme gegraphical and climaticlocations);complicated dependency relations;degrading social environment (criminality,prostitution);exposure to STD, AIDS, etc.;inequality between men and women (mendispose of economic resources); erosion of familyand social structure;violent behaviour towards child workers;violent conflicts among miners and withsurrounding communities;lack of law and orderPossible Consequencesdeterioration of ethical value systeminjuries or death due to crime or violenceomission of schooling and education;vulnerability to diseases due to lack of hygiene andsanitationexacerbation of injuries and illnesses due to lack ofhealth servicesSource: International Programme in Elimination of Child Labour, International Labour Office, Eliminating Child Labour in mining and Quarrying - BackgroundDocument, World Day Against Child Labour, 12 June,2005; pp 1319. Ministry of Labour and Employment, Government of India, Selected State-wise Average Daily Earnings of Workers in Mining Industries by Sex-Age in India, 2007.

16However, the number of people employed in the formalsector is relatively small — in 2005, this amounted to 20 Instead, the majority of people working inmining and quarrying in India are engaged in the informalsector, which is more labour intensive, less mechanised andless organised. Rather than being paid a daily wage for theirlabour, their earnings are usually according to what theyproduce. They often have no formal contracts and thereforeno employment rights. Many are migrant labourers livingin makeshift housing close to mine sites. Villagers inMariyammnahalli in Bellary district, Karnataka, explainedhow there are no facilities provided for mine workers. Allthe facilities provided — such as schooling for their children,houses, water and health facilities — are only available fortechnical workers and officers in the large mining companies.Informal mineworkers are provided with nothing, and theyare too afraid to join a union or complain about the situationin case they lose their jobs. 21 The nature of the work isfundamentally unsustainable.Illegal miningIllegal mining is rampant across India. It is estimated that inMaharashtra, at least 25% of the stone quarries are operatingillegally. 22 A similar situation was observed in all other statesvisited — in some areas, almost 50 per cent of mines andquarries are either illegal, or illegal extraction of mineralsis taking place there. For instance, in Jambunathahalli, asmall village near Hospet, in Karnataka, the research teamfound over 100 acres of land being used for small-scaleillegal mining. The researchers visited three sites wheremainly migrant labour from other parts of the state were illegally operating mines here but the numbers reduced dueto economic recession. 23 According to the District Miningreality reports show that there are double this numberoperating illegally. It was unofficially accepted that betweenTable 1.2 shows an estimate of the number of illegal minesoperating across the country as reported by the stategovernments.This table clearly shows the huge number of illegal mines thathave been identified by the state governments. In Andhrafound in 2008. However, no real action was taken followingtheir discovery — there was not a single First InformationReport (FIR) or court case filed. And in other states therehas been a noticeable increase in the number of illegal mines 2008.Mine closuresVery little attention has been given to “post mining” situationsand in particular, the ways in which local communitiesare impacted when mines shut down. Most mine closureplans do not address the impact of closure on workers orthe communities dependent on mining activities for theirsurvival. Attention is rarely paid to the rehabilitation of theseworkers and communities. In Jaisalmer district, Rajasthan,stone quarries have ceased operations in several localitiesand with no alternative livelihoods, former mine workers areforced to leave their villages and seek work in other states. In the Kolar district of Karnataka, the closing down of goldmining operations of the Kolar Gold Fields (KGF) has lefta large community with no livelihood options. When thecompany was closed down suddenly in 2002, the entirepopulation of KGF fell into a crisis with no alternativesource of income or livelihood. Workers stated that althoughtheir salaries were not very high, infrastructure and freeservices provided to them by the company ensured that thebasic needs of health, education and public services weremet, but when the company shut down, not only were thesalaries withdrawn but also all basic amenities. After theclosure, the company withdrew all amenities to the workers.State institutions did not take over as workers were not ina position to pay for these services. <strong>Children</strong> of workers’families were the most affected by the company’s decision.<strong>Children</strong>’s education and social security faced the axe. Aseducation was no longer a free service, many of the workerscould not pay school fees during the period of the strike.<strong>Children</strong> faced humiliation at school and many of them hadto drop out and take on the responsibility of sustaining theirfamilies, forcing many of them to travel out to Bangalore in20. Ministry of Labour and Employment, Government of India, Selected State-Wise Average Daily Employment and Number of Reporting Mines in India, 2002 – 2005.21.22.23.24.Interviews with mineworkers, Mariyammnahalli, Bellary district, Karnataka, June 2009.Interview with Mr. Bastu Rege, Director, Santulan, September 2009.Interviews carried out in Hospet area, Bellary, Karnataka, June 2009.Interviews with residents of Jethwai village, Jaisalmer district, Rajasthan, July 2009.

17Table 1.2: Number of illegal mines detected in India, 2009State Nos. of cases detected by state governments Action Taken by state sovernmentsYEAR 2006 2007 2008 2009 Vehicle FIRs Lodged Court cases FineUp to June seized filed realised2009Andhra Pra<strong>des</strong>h 5385 9216 13478 7332 844 ---- ---- 2112.95Chhattisgarh 2259 2352 1713 599 ---- ---- 2181 309.16Gujarat 7435 6593 5492 3720 106 114 8 7085.67Haryana 504 812 1209 416 103 138 2 133.33Goa 313 13 159 2 322 ---- 15.68Gujarat 7435 6593 5492 3720 106 114 8 7085.67Haryana 504 812 1209 416 103 138 2 133.33Himachal Pra<strong>des</strong>h 478 ---- 503 375 ---- ---- 464 21.04Jharkhand 631 82 225 ---- 5592 202 39 108.41Karnataka 3027 5180 2997 692 43585 931 771 3630.13Kerala 1595 2593 2695 802 ---- ---- ---- 532.7Madhya Pra<strong>des</strong>h 5050 4581 3895 2542 ---- 05 14831 1057.98Maharashtra 4919 3868 5828 3285 15212 13 ---- 1129.01Orissa 284 655 1059 365 1242+ 57 86 2309.3675 cyclesPunjab 218 26 50 48 ---- ---- ---- .96Rajasthan 2359 2265 2178 1130 368 441 59 413.49Tamil Nadu 2140 1263 1573 98 18722 133 155 6369.96Uttarakhand --- ---- 191 683 ---- ---- 38.50West Bengal 80 426 315 51 3680 897 167 ----adults leave for work to Bangalore by these trains and returnonly late in the night. The study team saw packed crowdsa majority of these daily commuters. When interviewed, theyoung girls, who commute by these trains, admitted that theyare vulnerable to physical and sexual abuse as the trains areovercrowded, but they brush it aside as unavoidable as theyhave no other choice but to sustain their families. Some ofthe women and young girls from the workers’ families turnedto prostitution to keep their families from starving. Whatwas more, young boys were getting into criminal activitiessuch as petty thefts and youth were getting hired by politicaland criminal groups which operate in Bangalore, for violentand criminal activities. However, people of KGF prefer notto have such news highlighted as it only sensationalises KGFwithout actually addressing their core problems. One of theglaring problems reported by the people themselves is theft.Young boys operate as petty criminals and steal parts of thecompany infrastructure like metal sheets from mine shafts,machinery and other scrap. (For more details see state reporton Karnataka in Part 2)

18How do the mining districtsin India fare in terms of childdevelopment?In order to examine the impact of mining on children inIndia, it is relevant to look at some of the child-relateddevelopment indicators in the key mining districts acrossthe country. The Table 1.3 brings together some of thesestatistics for the 15 districts where field research has beencarried out during the course of this study, and for anadditional nine districts, identified as being amongst themost heavily mined areas of the country. The situation ofchildren will be discussed in more detail for the majorityof these districts in the state overview section of the casestudies. However, a cursory glance at the table reveals thatin many of the districts, mineral wealth is not leading tobetter development outcomes for children. In the districtsmore dependent on mining, the majority have a lower thannational average literacy rate; more than 10 percent of high rate of child labour. In a national study on under fivemortality rates in India, these districts have also rankedclose to the bottom (see: Dantewada, Chhattisgarh;Panna, Madhya Pra<strong>des</strong>h; Koraput and Rayagada, Orissa).In contrast, the districts which have more diversifiedeconomies and are less dependent on mining can be seento have better development outcomes for children acrossthe board, for example, Cuddalore (Tamil Nadu) and Pune(Maharashtra).Who is affected by mining?Mining areas tend to be occupied by the poorest and mostmarginalised sections of society. Indeed, it is a twistedirony that the poorest people live on the lands richestwith natural resources. This is because a vast majority ofmining in the country is taking place in tribal areas. Adivasichildren lose their constitutional rights under the FifthSchedule over their lands and forests when their familiesare displaced from their lands.Despite the passing of the Samatha Judgement in 1997,which is intended to protect the rights of tribal peopleto their lands, violations continue and over 10 millionadivasis have lost their land in India. Across the country,Samatha JudgementThe Fifth Schedule of the Constitution of India deals withthe administration and control of Scheduled Areas and ofScheduled Tribes in these areas. It covers tribal areas inten states of India: Andhra Pra<strong>des</strong>h, Jharkhand, Gujarat,Rajasthan, Himachal Pra<strong>des</strong>h, Maharashtra, MadhyaPra<strong>des</strong>h, Orissa, Chhattisgarh and Sikkim. Essentially, theSchedule was intended to provide a guarantee to adivasipeople and protect the lands in the Scheduled Areas frombeing transferred to persons other than tribal. However,violations of this Schedule in Andhra Pra<strong>des</strong>h, whenlands in the scheduled area of Visakhapatnam districtwere transferred to Birla Periclase and 17 other miningcompanies, led the NGO Samatha to initiate a court casein the Supreme Court against the state government forleasing out tribal lands to private mining companies. Thisled to the historic Samatha Judgement in July 1997, whichrendered all leases to mining companies in Scheduled Areasnull and void and prohibited the future lease of lands inthese areas to non-tribals. Fifth Schedule Areas. 25 The Fifth Schedule covers tribalareas in ten states in India, and it guarantees prevention oftransfers in the form of mining leases to private companies.However, violations of this constitutional safeguard aretaking place by transfer of lands in the Scheduled Areas topersons other than the Scheduled Tribes, for which controlthe State is instrumental. It has allowed transfer of land mining companies, either as joint ventures with statebodies holding the majority ownership (as was done withRio Tinto and Orissa Mineral Development Corporation)or as private joint ventures (as in Utkal Alumina Limitedin Kasipur, Orissa) or directly to a private company (as inVedanta/Sterlite in Lanjigarh, Orissa). By opening up moreland for private mining companies, tribal communitiesare facing forcible displacement.A very conservative estimate indicates that in the last 50 years,approximately 20.13 million people have been displacedin the country owing to big projects, such as mines anddams. Of these, at least 40 per cent are indigenoustribal people. Only one-fourth of these people have beenresettled. 25. Samata, Fifth Schedule Areas, http://www.mmpindia.org/Fifth_Schedule.htm, uploaded: 11 December 2009.Shanti Sawaiyan,26. Forcible Displacement and Land Alienation is Unjust: Most of the Forcibly Displaced in Jharkhand are Adivasis, A paper for the III InternationalWomen and Mining Conference, 2004.

19Table 1.3: Key indicators in mining districtsDistrict / StateChild population*(0-14 years)SC % to total *populationST % to total *populationLiteracy rate*% children 6-14 years #out of schoolNumber of child labour*(0-14 years)NCLP district +Under 5 mortality rate ^(ranking out of593 districts)Backward district ~Adilabad, Andhra Pra<strong>des</strong>h 902,720 18.54 16.74 52.68 8.1 48,974 Yes 122 YesBastar, Chhattisgarh 496,762 2.96 66.31 43.91 6.0 49,289 No 496 YesDantewada, Chhattisgarh 283,002 3.36 78.52 30.17 N/A 30,121 Yes 578 YesRaigarh, Chhattisgarh 430,372 14.20 35.58 70.17 3.2 14,599 Yes 443 YesSarguja, Chhattisgarh 763,783 4.81 54.60 54.79 7.3 55,788 Yes 393 YesHazaribagh, Jharkhand 937,835 15.02 11.78 57.74 1.5 26,079 Yes 193 YesEast Singhbhum, Jharkhand 644,316 4.75 27.85 68.79 4.6 14,781 No 189 YesWest Singhbhum, Jharkhand 811,610 4.88 53.36 50.17 N/A 45,663 Yes 362 YesBellary, Karnataka 749,227 18.46 17.99 57.40 14.1 66,897 Yes 380 NoGulbarga, Karnataka 1,240,869 22.92 4.92 50.01 13.6 98,912 Yes 224 YesKolar, Karnataka 803,954 26.49 8.11 62.84 0.7 44,354 No 117 NoPanna, Madhya Pra<strong>des</strong>h 349,322 20.00 15.39 61.36 1.5 13,113 No 587 YesChandrapur, Maharashtra 646,241 14.34 18.12 73.17 1.6 10,259 No 311 YesNashik, Maharashtra 1,737,036 8.62 50.19 64.86 1.9 55,927 Yes 87 NoPune, Maharashtra 3,769,128 10.53 3.62 80.45 0.9 34,768 Yes 4 NoYavatmal, Maharashtra 832,599 10.28 19.26 73.62 3.7 20,732 Yes 220 YesWest Khasi Hills, Meghalaya 140,566 0.01 98.02 65.15 0.0 6,882 No 419 NoKeonjhar, Orissa 548,357 11.62 44.50 59.24 7.7 13,171 No 455 YesKoraput, Orissa 423,358 13.04 49.62 35.72 17.0 23,903 Yes 540 YesRayagada, Orissa 303,760 13.92 55.76 36.16 17.7 16,893 Yes 565 YesSundargarh, Orissa 611,228 8.62 50.19 64.86 4.8 19,537 No 372 YesBarmer, Rajasthan 847,335 15.73 6.04 58.99 11.4 58,320 Yes 407 NoJaisalmer, Rajasthan 216,264 14.58 5.48 50.97 15.0 12,869 No 332 NoJodhpur, Rajasthan 1,170,568 15.81 2.76 56.67 12.1 51,206 Yes 249 NoCuddalore, Tamil Nadu 655,105 27.76 0.52 71.01 0.8 11,961 No 104 YesSonbhadra, Uttar Pra<strong>des</strong>h 618,672 41.92 0.03 49.22 6.5 16,418 Yes 460 YesIndia 363,610,812 16.2 8.2 61 - 12,666,377 - - -Source: * Census 2001; # Pratham’s ASER 2008; + http://labour.nic.in/cwl/ChildLabour.htm;^ Jansankhya Sthirata Kosh; ~ Planning Commission

20area affected by the Vedanta project in Orissa are fromScheduled Tribes. Coal is considered one of the most polluting miningactivities and has serious implications on climate changeconcerns. Yet India’s agenda of coal expansion in the comingwill be met from coal-based power — is bound to haveserious long term impacts on a large population of children,especially Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe children,who live in the coal mining region of the central Indianbelt, which consist of some of the most backward states likeChhattisgarh, Madhya Pra<strong>des</strong>h, Bihar, Jharkhand, WestBengal, Orissa and Andhra Pra<strong>des</strong>h and parts of the NorthEast like Meghalaya.Specific situation of tribalchildrenEven under usual circumstances, statistics show that tribalchildren in India still struggle to access basic services suchas education and healthcare. According to the Ministry forTribe children remain out of school. 28 Continued exclusionand discrimination within the education system haveresulted in dropout rates remaining the highest amongstScheduled Tribe children as compared to all other socialgroups. The majority of health indicators show far poorer results forchildren from Scheduled Tribe populations as compared tothe national average. The most recent National Family Health infant and childmortality rates remain very high amongst tribals. Tribalchildren are also still less likely to receive immunisation. 30The Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, Jean Zielger,in his report based on his mission to India in August 2005,wrote that most victims of starvation are women andchildren of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes,with their deaths mainly due to discrimination in the foodbased schemes. According to his report, this was because ofdiscrimination in access to food and productive resources,evictions from lands, and a lack of implementation of foodbased schemes <strong>des</strong>pite laws prohibiting discriminationand “untouchability.” 31 Given that tribal children still faceenormous challenges in terms of access to food, educationand healthcare, displacement by mining projects increasestheir vulnerabilities further and renders their survival anddevelopment even more precarious. Displacement also has aserious psychological impact on children, who need a degreeof security and stability in their upbringing.One of the fundamental concerns with regard todisplacement of adivasi communities for mining projectsis the loss of constitutional protection for their children.The rehabilitation policy and the new tribal policy havebeen diluted from the earlier position of land-for-land ascompensation, to a mere monetary compensation if there wasno possibility of providing land. Further, the rehabilitationpolicy also specifies that no rehabilitation will be undertakenin the Scheduled Areas where less than 250 families areproposed to be affected. This, at one stroke, deprives the nextgeneration of adivasi children of the land transfer regulationsunder the Fifth Schedule, whose families are alienated fromtheir lands for mining projects. As these families eitherThe situation of tribal children in the mining areas ofJodhpur, Rajasthan, is a case in point. The residentsof Bhat Basti had previously been nomadic, roamingaround the countryside with their livestock. However,lack of available land for animal grazing, as a result ofurbanisation and industrialisation, forced them to settlein one location almost 20 years ago, where all the adultsand many of the children now work as daily wage labourersin the local stone quarries. None of the 200-odd childrenin the village attended school and all were illiterate. Theylived in kachha housing, made of stones and coveredwith black tarpaulin sheets. There was no running water,electricity or sanitation available in the village. Thechildren had received no vaccinations apart from polio andall are malnourished. The research team met one severelymalnourished boy who was claimed to be two years old butlooked like a baby of no more than nine months.27. Tata AIG Risk Management Services Ltd, Rapid environmental impact assessment report for bauxite mine proposed by Sterlite Industries Ltd near Lanjigarh,Orissa, August 2002, p. 7 of the executive summary.28. For a full overview on Scheduled Tribe children and education, see Status of <strong>Children</strong> in India: 2008, published by HAQ: Centre for Child Rights.29. Ministry of Human Resource Development, Chapter on Elementary Education (SSA and Girls Education) for the XI th Plan Working Group Report, 2007, pp. 14.30. For a full overview on Scheduled Tribe children and health, see Status of <strong>Children</strong> in India: 2008, published by HAQ: Centre for Child Rights.Paradox of Hunger amidst Plenty.31. Report of the Special Rapporteur on Right to Food, Jean Ziegler, on his Mission to India (August 20-September 2, 2005.Combat Law Volume 5 Issue 3. June-July 2006.

21migrate to plain areas or are converted to landless labourerseven if they continue to live in the Scheduled Areas, theyno longer enjoy the privilege of the Fifth Schedule as far asland is concerned. This is a constitutional violation of therights of the adivasi child. 32DisplacementMining areas are inhabited by people. Taking over land formining means displacing them. These forced evictions, whenland is taken over for extraction, or for setting up plantsand factories, uproots and dislocates entire communities.<strong>Children</strong> are forced out of schools, lose access to healthcareand other basic services and are forced to live in alien places.Most often, there is little or no rehabilitation effort madeby the government. This has a long-term impact on thedisplaced children.Across the world, tribal (or indigenous) populations arebeing displaced for mining activities. Mining struggles inindigenous communities have been witnessed in numerouscountries, from Canada to the Philippines, and from Ugandato Papua New Guinea and to the USA, which massacrednative Indians, 33 first for the gold rush and later, for otherminerals like coal and uranium. Mineral resources areoften found in places inhabited by indigenous populations.Therefore, when mining activity begins, these communitiesare displaced from the hills and forests where they live. Theythen lose access not only to their homes and land, but also totheir traditional livelihoods. In most places, compensationhas been wholly inadequate and tribal communities are forcedinto poverty. Their capacity for subsistence survival is often<strong>des</strong>troyed — tribal symbols of prosperity in subsistence arenot recognised as anything that have worth or value. Minesand factories have reduced self-reliant, self-respecting tribalfamilies to living like refugees in ill-planned rehabilitationcolonies, while rendering many others homeless. 35The National Mineral Policy, 2008, recognises that“Mining operations often involve acquisition of land heldby individuals including those belonging to the weakersections.” It highlights the need for suitable Relief andRehabilitation (R&R) packages and states that “Specialcare will be taken to protect the interest of host andindigenous (tribal) populations through developingmodels of stakeholder interest based on internationalbest practice. Project affected persons will be protectedthrough comprehensive relief and rehabilitation packagesin line with the National Rehabilitation and ResettlementPolicy.” However, several problems with respect to theR&R policy, such as under-estimation of project costs andlosses, under-financing of R&R, non-consultation withaffected communities and improper implementation of thepromised rehabilitation, are some of the glaring failures onthe part of the state with respect to mining projects. This iswell reflected, for example, in the case study of the resettledcamps of NALCO in Orissa. Despite the grand statements made in the NationalMineral Policy, 2008, and the existence finally of a NationalRehabilitation and Resettlement Policy, thousands of peoplewill continue to lose their land and end up in worse situationsof poverty if the government continues to prioritise profitsfrom mining over the rights of communities to live ontheir land. One recent example of this has been the struggleby the Dongria Kondh tribe in Orissa to prevent a Britishmining company, Vedanta, from displacing them. Thegroups have lived for many generations in this area and theNiyamgiri mountain is considered by them to be a sacredRajesh (name changed) is fifteen years old and comesfrom the village of Janiguda. He works in a roadsiderestaurant at Dumuriput of Damanjodi. His family lostall their land for the NALCO project, which converted hisfather, who did not get a job in the company, into analcoholic. Having spent all the compensation money onliquor, the father left the family on the streets. Rajeshdropped out of school and had to come to Damanjoditown in search of work to support his family. He earnsaround Rs. 1,200 per month working in the hotel andsends home around Rs. 1,000 every month. He says, “Workin the hotel is difficult and there is no time for rest exceptafter 12 in the night every day.”Source: Interview carried out in Damanjodi, Orissa, 3 February 2010.32. Samatha, A Study on the Status and Problems of Tribal <strong>Children</strong> in Andhra Pra<strong>des</strong>h, 2007.33.34.35.Carlos D. Da Rosa, James S. Lyon, Philip M. Hocker, Golden Dreams, Poisoned Streams, Published by Mineral Policy Center, August 1997.Bhanumathi Kalluri, Ravi Rebbapragada, 2009, Displaced by Development - Confronting Marginalization and Gender Injustice - The Samatha Judgement -Upholding the Rights of Adivasi Women, Sage PublicationsVidhya Das, Human Rights, Inhuman Wrongs – Plight of Tribals in Orissa, Published in Economic and Political Weekly, 14 March 1998.36. Government of India, National Mineral Policy, 2008.37.See case study report on NALCO project-affected community in Koraput, Orissa.