5. Access to water resources - Natural Resources Institute

5. Access to water resources - Natural Resources Institute

5. Access to water resources - Natural Resources Institute

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

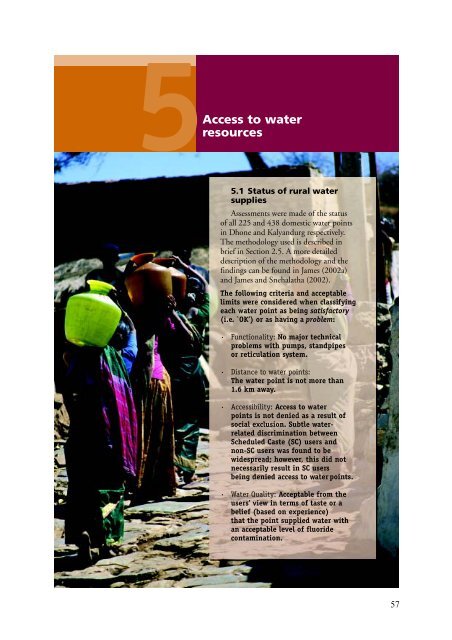

5<strong>Access</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>water</strong><strong>resources</strong><strong>5.</strong>1 Status of rural <strong>water</strong>suppliesAssessments were made of the statusof all 225 and 438 domestic <strong>water</strong> pointsin Dhone and Kalyandurg respectively.The methodology used is described inbrief in Section 2.<strong>5.</strong> A more detaileddescription of the methodology and thefindings can be found in James (2002a)and James and Snehalatha (2002).The following criteria and acceptablelimits were considered when classifyingeach <strong>water</strong> point as being satisfac<strong>to</strong>ry(i.e. `OK’) or as having a problem:· Functionality: No major technicalproblems with pumps, standpipesor reticulation system.· Distance <strong>to</strong> <strong>water</strong> points:The <strong>water</strong> point is not more than1.6 km away.· <strong>Access</strong>ibility: <strong>Access</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>water</strong>points is not denied as a result ofsocial exclusion. Subtle <strong>water</strong>relateddiscrimination betweenScheduled Caste (SC) users andnon-SC users was found <strong>to</strong> bewidespread; however, this did notnecessarily result in SC usersbeing denied access <strong>to</strong> <strong>water</strong> points.· Water Quality: Acceptable from theusers’ view in terms of taste or abelief (based on experience)that the point supplied <strong>water</strong> withan acceptable level of fluoridecontamination.57

· Adequacy of supply: Adequate supply of<strong>water</strong> for domestic uses, from the users’point of view.· Peak summer availability: Water collectiontime and effort not much more during peaksummer months than in other months.· Over-crowding: No more than 250 usersper <strong>water</strong> point.Using these criteria and acceptable limits,Figures 34 and 35 summarise the users’ view ofthe status of <strong>water</strong> points in Kalyandurg andDhone respectively. A <strong>water</strong> point was classifiedas being a “problem” <strong>water</strong> point if, in the view ofthe users, it failed <strong>to</strong> meet the acceptable limits ofany one of the criteria. This assessment indicatedthat, although no <strong>water</strong> point was more than1.6 km away or had more than 250 users, 51%and 24% of <strong>water</strong> points in Kalyandurg andDhone respectively were either not functional orfailing <strong>to</strong> meet the adequacy of supply and <strong>water</strong>quality norms of the Rajiv Gandhi NationalDrinking Water Mission (see Box 11). Thesefigures contrast starkly with official figures for“problem” <strong>water</strong> points that showed only a smallpercentage of <strong>water</strong> points as having a problem.One reason for this is the fact that the officialstatistics concentrate almost entirely on thefunctionality of <strong>water</strong> supply systems and onwhether or not a supply of 40 lpcd can beprovided. Also, the official statistics do not givemuch attention <strong>to</strong> problems of peak summeravailability and the problems experienced bywomen particularly in queuing for <strong>water</strong> duringthese lean times.25 year old man suffering from skeletal fluorosis,Battuvani Palli, KalyandurgFluoride problems in BattuvanipalliIn Battuvanipalli village nearKalyandurg <strong>to</strong>wn, villagers complainedof the symp<strong>to</strong>ms of fluoridecontamination (pain in the joints,falling teeth, bleeding gums and brittlebones), even though the fluoridetesting of the <strong>water</strong> source by the RWSshowed a concentration of only 1.7 ppm(i.e. in excess of the permissible limi<strong>to</strong>f 1.5 ppm). Action was not taken sincethe “operational” limit being used was2.0 ppm. Even worse, subsequentanalysis of this source by the WHiRLProject showed that fluorideconcentration was actually in excess of4 ppm.Washing clothes in the Pennar river58

Figure 34. Users’ view of status of domestic<strong>water</strong> points in KalyandurgFigure 3<strong>5.</strong> Users’ view of status of domestic<strong>water</strong> points in Dhone59

Box 11: Criteria for Identification of Problem HabitationsA habitation which fulfils the following criteria may be categorised as a Not Covered (NC)/No SafeSource (NSS) Habitation:(a) The drinking <strong>water</strong> source/point does not exist within 1.6 km of the habitations in plains or 100m elevation in hilly areas. The source/point may either be public or private in nature. However,habitations drawing drinking <strong>water</strong> from a private source may be deemed as covered only when the<strong>water</strong> is safe, of adequate capacity and is accessible <strong>to</strong> all.(b) Habitations that have a <strong>water</strong> source but are affected with quality problems such as excesssalinity, iron, fluoride, arsenic or other <strong>to</strong>xic elements or biologically contaminated.(c) Habitations where the quantum of availability of safe <strong>water</strong> from any source is not enough <strong>to</strong> meetdrinking and cooking needs. [Estimated at 40 litres per person per day, including drinking(3 litres), cooking (5 litres), bathing (15 litres), washing utensils and house (7 litres) and ablution(10 litres)]Hence in the case of a quality affected habitation, even if it is fully covered as per the earlier norms itwould be considered as a NSS habitation if it does not provide safe <strong>water</strong> at least for the purpose ofdrinking and cooking.Habitations which have a safe drinking <strong>water</strong> source/point (either private or public) within 1.6 km. inthe plains and 100 m in hilly areas but where the capacity of the system ranges between 10 lpcd <strong>to</strong> 40lpcd, could be categorised as “Partially Covered (PC)”. These habitations would, however, be consideredas “Safe Source (SS)” habitations, subject <strong>to</strong> the <strong>water</strong> quality parameter.All remaining habitations may be categorised as “Fully Covered (FC)”.Source: RGNDWM (2000).Figures 36 and 37 provide information on the most common <strong>water</strong> point problems encounteredby users in Kalyandurg and Dhone respectively. It can be seen that unacceptable <strong>water</strong> quality andnon-functional <strong>water</strong> points were the problems that were most frequently cited in Kalyandurgand Dhone respectively.15674Figure 36. Types ofdomestic <strong>water</strong> supplyproblems,Kalyandurg Mandal,Oc<strong>to</strong>ber 20012227Non-functiona l Inadequate supply Poor quality Multiple problems3752076Figure 37. Number of<strong>water</strong> points withdifferent types ofproblems,Dhone Mandal,March 20011Non-functiona l Overcrowdi ng Inadequa tesupplyUnpredicta ble Poor quality Multipleproblems60

The users’ assessments in Kalyandurg alsoconsidered a number of “minor” problems which,following appropriate capacity building, could besolved locally. These were:· Leakage: Many pumps, standpipes, tapsand reticulation systems had leaks;· Malfunctioning hand pumps: Many handpumps were malfunctioningas a result of inadequate maintenance;· Unsanitary conditions around <strong>water</strong> points:Inadequate drainage around many <strong>water</strong>points was the main cause.Misleading Figures:The Case of PathacheruvuOn paper, there is only one functioninghand pump for all 45 households ofPathacheruvu. A visit however showedup two agricultural bore wells near thevillage settlement (closer than the handpump) with sufficient <strong>water</strong> <strong>to</strong> meet alldomestic needs of those households,besides providing irrigation andlives<strong>to</strong>ck needs. However, the handpump that was used most had a fluorideconcentration in excess of 2 ppm.In summary, important findings from theassessment of the status of domestic <strong>water</strong>supplies included:· Users’ views of the status of domestic <strong>water</strong>supplies are not captured by the currentprocedures for moni<strong>to</strong>ring rural <strong>water</strong>supplies;· There is a major disparity between theusers’ views of the status of rural <strong>water</strong>supplies and official statistics;· The nature and intensity of problems varynot only across villages but also withinvillages. Some households were moreaffected than others since the nature of theproblems vary from <strong>water</strong> point <strong>to</strong> <strong>water</strong>point. Moreover, detecting problems withdomestic <strong>water</strong> supply can be quitecomplicated. Water from a <strong>water</strong> point maybe used for different purposes (such as forlives<strong>to</strong>ck, domestic uses, and irrigation)depending on the quality and quantity of<strong>water</strong>. Thus, a large number of <strong>water</strong> pointsin a village and/or adequate quantities of<strong>water</strong> at all <strong>water</strong> points may concealproblems with <strong>water</strong> quality (e.g. fluoridecontamination) or social discrimination..<strong>5.</strong>2 Water-related socialdiscriminationSocial restrictions on use of drinking anddomestic <strong>water</strong> sources by Scheduled Castes (SCs)and Scheduled Tribes (STs) were found in allvillages surveyed. These restrictions <strong>to</strong>ok twomain forms.· SCs and STs cannot <strong>to</strong>uch (‘contaminate’)open-well <strong>water</strong>, but can use public tapsand hand pumps. Wherever scarcity forcesvillagers <strong>to</strong> use open wells as a source ofdomestic supply, SCs and STs bring theirvessels <strong>to</strong> the well but cannot draw <strong>water</strong>from it. They have <strong>to</strong> wait for upper castevillagers <strong>to</strong> fill their pots with <strong>water</strong>.· In many villages, separate hand pumps orpublic taps have been set up in parts of thevillage where SCs and STs stay (commonlycalled ‘SC colonies’). When <strong>water</strong> is scarceand insufficient in the “upper caste” areasof the village, but available in the SCcolony, upper caste villagers come <strong>to</strong> filltheir vessels. The result is the SC and STfamilies have <strong>to</strong> wait till the upper casteshave taken their fill before collecting theremaining <strong>water</strong> from public taps or handpumps installed for their exclusive use.13354Figure 38: Nature ofminor problems,Kalyandurg Mandal,Oc<strong>to</strong>ber 200120Major leakages Unsanitary surroundings Multiple problemsNature of minor problem61

Caste Restrictions in KocheruvuA large cruciform step well inthe centre of the old villagesettlement was being used fordrinking <strong>water</strong> in December2000 because the piped <strong>water</strong>supply was not functioning as aresult of a major pumpbreakdown. Upper caste menand women walked down thesteps and filled their vesselsdirectly from the well. Lowercaste men and women, however,had <strong>to</strong> wait half-way down thesteps for an upper caste person<strong>to</strong> favour them by filling theirvessels. Not all upper castes didthis and sometimes the lowercaste person had <strong>to</strong> wait forsome time.As lower caste villagers are not allowed <strong>to</strong> take <strong>water</strong>directly from the open well, a higher caste woman is fillingthe pot of the lower caste woman, Kocheruvu, DhoneSC Colony in ManirevuIn December 2000, the newlyelectedsarpanch had providedthe SC colony with 4 new publictaps so as <strong>to</strong> improve thecolony’s <strong>water</strong> supply that washither<strong>to</strong> dependent on handpumps. But while public taps inthe main village are outlets fromsmall s<strong>to</strong>rage tanks that are, inturn, supplied by the pipedsystem, the new taps in the SCcolony are not connected <strong>to</strong>s<strong>to</strong>rage tanks. This means that ifand when electricity fails andthe main pump of the pipedsystem s<strong>to</strong>ps working, the tapsin the SC colony run dry whilethe taps in the main villagecontinue <strong>to</strong> flow, using the <strong>water</strong>s<strong>to</strong>red in the s<strong>to</strong>rage tank.<strong>5.</strong>3 Water-related functionalityof village-level institutionsStrong village-level institutions are a vital elemen<strong>to</strong>f the proposed reform of rural <strong>water</strong> supply andsanitation services coordinated by the Rajiv GandhiNational Drinking Water Mission (see Box 13). AndhraPradesh has an impressive his<strong>to</strong>ry in forming women’sself-help groups (SHGs), and it is normal <strong>to</strong> expect thatvillage decision-making has been strengthened by thisdevelopment. The participa<strong>to</strong>ry assessments sought <strong>to</strong>find out the extent <strong>to</strong> which village institutions like thepanchayat and SHGs, respond <strong>to</strong> <strong>water</strong>-relatedproblems.In Dhone, assessments for the 42 villages surveyedindicated that in a majority of villages the panchayatwas unsympathetic <strong>to</strong> problems concerning <strong>water</strong>supply (and sanitation). In Kalyandurg in contrast, itwas found that in almost half the villages the panchayatwas sympathetic and effective as far as <strong>water</strong>-relatedproblems were concerned. The results for Kalyandurgare summarised in Figure 39 along with the questionsthat were used as part of the ordinal scoring system.62

Box 12: RWSS Sec<strong>to</strong>r Reform ProjectThis project is being implemented in 58 districts in 22 states all over the country, includingChit<strong>to</strong>or, Nalgonda, Prakasam and Khammam in Andhra Pradesh. This project advocates fourkey principles for sustainable RWSS systems:1. Changing the role of government from provider <strong>to</strong> facilita<strong>to</strong>r2. Increasing the role of communities in the planning and management oftheir own facilities3. Users paying all operation and maintenance costs, and at least 10% of the capital costsof supply4. Promoting integrated <strong>water</strong> resource managementThe institutional arrangements <strong>to</strong> implement the project include the formation of VillageWater and Sanitation Committees (VWSCs), as sub-committees of the Gram Panchayat, <strong>to</strong>manage implementation and subsequent maintenance at the village level.Source: Note on Andhra Pradesh Pilot Projects: Rural <strong>water</strong> supply and sanitation sec<strong>to</strong>rreforms, Water and Sanitation Program – South Asia, September 2000.2520No. of habitations1510500 25 50 75 100QPA ordinal scores (de tails in accompanying table )Figure 39. Panchayat Response <strong>to</strong> Water Related Problems, Kalyandurg Habitations, 2001QPA Ordinal Scoring Options Ordinal Scores Number ofvillagesListens, but no action is taken 0 9Listens and acts, but no follow up and hence no result 25 11Listens and acts, but results come after a long time 50 8Listens and acts, gets quick results but not effective 75 5Listens, acts, and gets quick and effective results 100 21Two main reasons were identified for the poor response by the panchayat. These were;. Apathetic leaders: These included sarpanches of the revenue village living in one of theconstituent habitations and paying relatively less attention <strong>to</strong> complaints from the otherhabitations.. Fund constraints: Even when sarpanches were interested in taking action, funds wereoften a major constraint.63

180160140120No. of SHGs1008060402000 25 50 75 100QPA ordinal scores (details in accompanying table)Figure 40: Status of SHG functioning: Kalyandurg SHGs, 2001QPA Ordinal Scoring Options QPA Scores Number of SHGsOnly saving; no loans 0 15Saving and loans only for consumption purposes 25 43Saving, effective utilisation of loans & for at least 50 20one productive purpose (no results)Saving, effective utilisation of loans & for at least 75 31one productive purpose (breakeven)Saving, effective utilisation of loans & for at 100 159least one productive purpose (with profits)<strong>5.</strong>4 Functionality of SHGsThe assessment of SHGs indicated that manywere being very successful in terms of thrift andcredit but few had any interest in or experienceof tackling <strong>water</strong>-related problems. This findingcasts some doubt on the proposals from somequarters <strong>to</strong> involve SHGs in <strong>water</strong>-relatedchallenges. In some villages, particularly thosewith weak panchayats, it was found thatspontaneous community action was leading <strong>to</strong>solution of <strong>water</strong>-related problems. This action,however, even when it involved SHG members,was not organised by the SHGs.Figure 40 presents the results of theparticipa<strong>to</strong>ry assessment of the functioning ofSHGs in Kalyandurg. This shows that the villagelevelperception is that 159 of the 268 SHGs (ornearly 60%) fall in<strong>to</strong> category “Saving, effectiveutilisation of loans for at least one productivepurpose (with profits).” Figure 41 presents theresults of the assessment of SHG influence oncommunity decision-making in villages of Dhone.This shows that in 36 of the 42 villages (or 86%)surveyed SHGs were not effective in influencing<strong>water</strong>-related community decision making. Thesefindings suggest that women’s SHGs will needconsiderable strengthening before they can take onthe role of change agents in the habitations in thetwo study mandals.Box 13: Some villagers’ view on theresponse of the panchayat <strong>to</strong> <strong>water</strong>supply problems“Since Sarpanch is residing in Chapiri,he has not taken any interest and noresponse, in spite of people’s request.”(Chapirithanda habitation, Chapirirevenue village).“No response from panchayat, asSarpanch was from other village.”(Mallapuram habitation, Palavoyrevenue village).“Panchayat listens, but no actiontaken, because of no funds <strong>to</strong>panchayat.” (Varli habitation, Varlirevenue village).“When mo<strong>to</strong>r underwent repairs seventimes, on all occasions, the panchayat<strong>to</strong>ok immediate and effective action.”(Duradakunta habitation, Duradakuntarevenue village).“Panchayat listens <strong>to</strong> problem and actsquickly in case of handpump repair atall times.” (Palavoy habitation, Palavoyrevenue village).64

<strong>5.</strong>5 Participation of the poorand women in communitydecision-makingEven if a community decides <strong>to</strong> act on a<strong>water</strong>-related issue, the decision <strong>to</strong> act is notalways made collectively or democratically.The participa<strong>to</strong>ry assessments explored this issueand the results are summarised in Figures 42 and43. Figure 42 shows that in 91% of the villagesin Kalyandurg, the poor participate in meetingsand in 67% of the villages the poor bothparticipate and influence decisions affectingthem. Figure 43 shows that the situation inDhone is not so encouraging, in that the poorparticipate in only 50% of the villages, and thepoor both participate and influence decisionsaffecting them in just 16% of the villages.The relatively high figures for Kalyandurg can beattributed <strong>to</strong> the fact that an NGO, namely theRural Development Trust, has been working inKalyandurg for more than 25 years. One ofthe main thrusts of their work has beenempowerment of the poor.Waiting <strong>to</strong> fill <strong>water</strong> pots, Kocheruvu, DhoneNo. of habitations201816141210864200 25 50 75 100QPA ordinal scores (details in accompanying table)Figure 41. SHG influence on community decision-making, Dhone, 2001QPA Ordinal Scoring Options QPA Scores Number ofHabitationsGroups do not play a role, it is left <strong>to</strong> individual members 0 10Groups represent, but do not pursue, even <strong>to</strong> get assurances 25 8of future actionGroups represent pursue and get assurance of action, 50 18but no effective action occursGroups represent, pursue, and get effective action 75 3Groups listen, act, and get quick and effective results 100 365

Box 14. Some villagers’ views ondecision-making involving the poor,Kalyandurg“Because of disunity, disputes andmisunderstanding, nobodyparticipates in community decisionmaking.”(Balavenkatapuram).“In spite of the large number of poorpeople, we are unable <strong>to</strong> influencethe decisions taken by the non-poor.”(Dodagatta).“Since, it is a single community,all families are relatives.”(Pathacheruvu).“Poor and non-poor participated indecision making and constructed tworatchakattas, one in the SC colonyand the other in the bus stand.”(PTR Palli).Hand pump in Obulapuram, Kalyandurg“The whole village is participating inannual meetings (on every Shri RamaNavami) and they discuss and makedecisions about village problems andthe means <strong>to</strong> solve them.”(Vitlampalli).“Poor could influence in gettinghousing scheme, pipeline, electricityetc.” (Bedrahalli).“Non-poor give preference <strong>to</strong> poorin decision-making; and poor alsoaccus<strong>to</strong>med <strong>to</strong> give their opinions<strong>to</strong> community. Repair work done <strong>to</strong>Mariamma temple, ratchakattaconstructed in SC colony. Poorinfluence decisions concerningthemselves.” (Mudigal).Traditional practice of applying a mix of <strong>water</strong>and dung <strong>to</strong> the ground in front of houses,Pathacheruvu village, Dhone66

Figure 42. Villagewise participation of the poorin community decision-making, KalyandurgFigure 43. Village wise participation of the poorin community decision-making, Dhone67

Figure 44. Villagewise participation ofwomen in community decision-making,KalyandurgFigure 4<strong>5.</strong> Villagewise participation ofwomen in community decision-making,DhoneWomen are not involved in community decision-makingWomen are in committes but do not attendWomen attend meeting but mostly let men take major ddecisionsWomen attend, participate but cannot influence major decisionsWomen attend, participate and are able <strong>to</strong> influence major decisionsNo data68

Figure 44 and 45 summarise findings relating<strong>to</strong> the participation of women in communitydecision-making in Kalyandurg and Dhonerespectively. These figures show that inKalyandurg women were only participating inmeetings in 17% of the villages and participatingand influencing decisions in 4% of the villages.In Dhone, women were participating in meetingsin 14% of the villages and participating andinfluencing decisions in 5% of the villages.For Kalyandurg in particular, there is a starkcontrast between the figures on the participationof the poor and of women in meetings.These findings confirm that, although poor menparticipate in meetings, women, and particularlypoor women, rarely participate in meetings.In summary, despite impressive advances inwomen’s empowerment through the SHGmovement in Andhra Pradesh, women still donot participate effectively in community decisionmaking.Even in a mandal like Kalyandurg,which has a good record in remedial actionby panchayats and community participation,participation by women in community decisionsis low. In a majority of the habitations (allexcept 2), women were either not involved incommunity decision-making, or did notattend meetings or influence major decisionson community issues relating <strong>to</strong> <strong>water</strong> andsanitation.<strong>5.</strong>6 <strong>Access</strong> <strong>to</strong> irrigation <strong>water</strong><strong>Access</strong> <strong>to</strong> reliable <strong>water</strong> supplies for irrigation,lives<strong>to</strong>ck and other productive purposes isextremely important <strong>to</strong> the livelihoods of a largenumber of people living in the study mandals.Although there is some growth in the servicesec<strong>to</strong>r, the majority still rely heavily onagricultural production. There is a strong beliefamongst small and marginal farmers, based onexperience, that gaining access <strong>to</strong> <strong>water</strong> <strong>resources</strong>and becoming an irriga<strong>to</strong>r farmer is a reliablemeans of escaping from poverty. Hence,considerable amounts of money have been andcontinue <strong>to</strong> be invested in borewell constructionin Dhone and Kalyandurg. Private borewellinvestments <strong>to</strong>tal around Rs. 4 crores in Dhoneand around Rs. 22 crores in Kalyandurg (basedon a cost of Rs. 35,000 per borewell at 2002prices). This level of investment reflects therelative profitability of irrigated cropping.However, over-exploitation of ground<strong>water</strong> inboth study mandals has led <strong>to</strong> a situation wherebyinvestments in irrigation have become awidespread cause of poverty (see Box 16).Box 1<strong>5.</strong> Villagers’ views on women’sparticipation in decision-making“Women are not included in communitymeetings. They are scared <strong>to</strong> participate.Women participate only for theirproblems, and are not involved incommunity problem solving.” (Manirevu).“Men are not giving much importance <strong>to</strong>women’s participation in communitymeetings.” (Obalpuram).“Women are not encouraged <strong>to</strong> participatein community decisions, even thoughmost of them have minimum education.”(Kadadarakunta).“Women are not being allowed and alsowomen are not interested inparticipating.” (Venkatampalli).“Women mainly participate in VidyaCommittee meetings. But once they madea dharna for <strong>water</strong> problem at KalyandurgMRO office.” (Vitlampalli).“Women participated in communitydecision-making; asked for communitylatrines. Decision taken and work alsodone.” (Mudigal).“DWCRA groups participated in roadformation by shramadan. Women attendcommunity and Gram Sabha meetings andspeak about their problems.” (Golla).Overhead tank in Kocheruvu, Dhone69

Box 16. Mechanisms that link poverty <strong>to</strong> overexploitation and competition for ground<strong>water</strong><strong>resources</strong> in crystalline basement areasFailed borewell investments. Investment in well construction is a gamble with high risks,particularly in ridge areas and other areas with low recharge potential. Farmers who takeloans <strong>to</strong> construct borewells but are unable <strong>to</strong> find ground<strong>water</strong>, will not be able <strong>to</strong> makerepayments and, in many cases, will quickly spiral in<strong>to</strong> debt.Higher borewell costs of latecomers. Latecomers <strong>to</strong> borewell construction often have <strong>to</strong> makelarger investments than firstcomers. This is because ground<strong>water</strong> levels have already fallen,and siting a successful borewell involves drilling <strong>to</strong> greater depths. Also latecomers oftenhave smaller land holdings and, as a result, the scope for siting a successful well is morelimited. The net result is latecomers have <strong>to</strong> take larger loans and, consequently, are morelikely <strong>to</strong> default.Competitive well deepening. Wells owned by rich farmers tend <strong>to</strong> be more productive and/orgenerate more income. If ground<strong>water</strong> overexploitation takes place and <strong>water</strong> levels decline,richer farmers are more able <strong>to</strong> finance competitive well deepening. Also, as wealthy farmerstend <strong>to</strong> have established their wells before competitive deepening starts, they are in a muchbetter position <strong>to</strong> take new loans. As latecomers are often unable <strong>to</strong> finance competitive welldeepening, their wells fail and they are unable <strong>to</strong> repay loans and often have <strong>to</strong> sell theirland <strong>to</strong> moneylenders, who are in many cases the rich farmers.Impacts on domestic <strong>water</strong> supplies. Overexploitation of ground<strong>water</strong> for irrigation haslowered <strong>water</strong> tables in aquifers that are also sources of urban <strong>water</strong> supply. This has led <strong>to</strong>a reduction in supply, particularly, in peak summer and periods of drought. Collecting <strong>water</strong>takes more time and involves carrying <strong>water</strong> longer distances. In some extreme cases,competition between agricultural and urban users is leading <strong>to</strong> complete failure of thevillage <strong>water</strong> supply. In these cases, villagers sometimes have <strong>to</strong> use <strong>water</strong> sources that arenot safe and suffer illness as a result. Illness usually represents both a loss of income andexpenditure on medical treatment.Crop failure or low market prices. If crops should fail for any reason (e.g. major interruption inelectricity supply, wells running dry) or if there should be a steep fall in market prices ofproduce, farmers with large loans for borewell construction are extremely vulnerable. If theyshould fail <strong>to</strong> make repayments on loans, which typically have interest rates of 2% permonth in the informal money market, they can easily spiral in<strong>to</strong> indebtedness with littlehope of recovery.Falling ground<strong>water</strong> levels. Falling ground<strong>water</strong> levels in many areas have increased the riskof wells failing during periods of drought as there is no longer a ground<strong>water</strong> reserve orbuffer <strong>to</strong> maintain supply during dry seasons and droughts. It is often poor and marginalfarmers that have borewells that are most likely <strong>to</strong> fail albeit temporarily during suchperiods.Impact of intensive drainage line treatment. Intensive drainage line treatment as part of<strong>water</strong>shed development and other programmes can impact on the pattern of recharge.The net result is that, in semi-arid areas, some borewell owners can see the yields of theirborewells increase but others (usually located downstream) see their borewells becomeless productive.Reduction in informal <strong>water</strong> vending. Informal markets for ground<strong>water</strong> have emerged inrecent years in these parts of semi-arid India, as farmers with access <strong>to</strong> surplus supplies sell<strong>water</strong> <strong>to</strong> adjacent farmers who either lacked the financial <strong>resources</strong> <strong>to</strong> dig their own wellsor had insufficient supplies in the wells they did own. Now as well yields decline, <strong>water</strong>markets are becoming less common as well owners keep all available supplies for theirown use.Source: Batchelor et al. (2003)70

Figure 46. Relative profitability of rainfed crops (brown bars) andirrigated crops (green bars), Dhone454035302520151050SetariaSorghumBajraCas<strong>to</strong>rGroundnutSunflowerNet returns (thousands Rs /haRedgramCot<strong>to</strong>nBengalgramBrinjalToma<strong>to</strong>Cot<strong>to</strong>nPaddyChilliOnion<strong>5.</strong>7 Profitability of irrigatedcroppingProfits per hectare from irrigated agricultureare, on average, twice those from rainfed farming.The lowest profit from an irrigated crop is oftenhigher than the highest profit from a rainfedcrop. Using data from Dhone, Figure 46compares the profitability of rainfed and irrigatedcrops. Cultivation of some crops, however, is not`economic’, and farmers continue <strong>to</strong> cultivatelargely because they do not have <strong>to</strong> buy theinputs they require. Compared <strong>to</strong> areas underrainfed cropping, a relatively small proportionof the cultivable area of each mandal is irrigated.Although the large kharif areas under rainfedgroundnut are justified by the high relativeprofits, areas under other crops do not generallycorrelate with the net returns per hectare.Crops with high returns (e.g., mulberry, onions,vegetables) are grown on comparatively smallerareas because of local fac<strong>to</strong>rs such as access <strong>to</strong>market, high cultivation costs, production risksand lack of local s<strong>to</strong>rage and processing facilities.Food crops (e.g., jowar), on the other hand, aregrown on larger areas than warranted by theirrelative profit because they provide other benefits(e.g. food security).Water is not such a big constraint on nonagriculturalactivities such as brick-making,making pottery and operating tea stalls/kiosks.However, ready access <strong>to</strong> small volumes of <strong>water</strong>at times when it is needed is still critical <strong>to</strong> thesuccess of such enterprises. More information onthe economics of different <strong>water</strong> use options canbe found in James (2000b).Con<strong>to</strong>ur trenching71