Divers Paths to Justice - English - Forest Peoples Programme

Divers Paths to Justice - English - Forest Peoples Programme

Divers Paths to Justice - English - Forest Peoples Programme

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

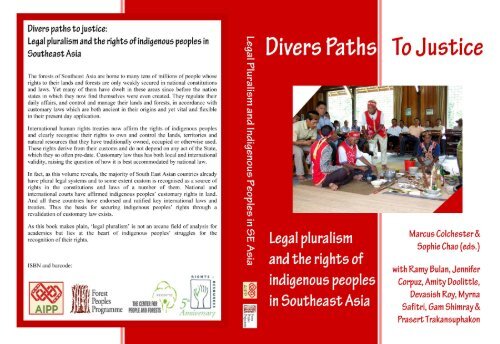

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast Asia<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> To <strong>Justice</strong>Legal pluralism and the rights ofindigenous peoples in Southeast AsiaMarcus Colchester & Sophie Chao (eds.)with Ramy Bulan, Jennifer Corpuz, Amity Doolittle,Devasish Roy, Myrna Safitri, Gam Shimray &Prasert Trakansuphakon1

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast Asia<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> To <strong>Justice</strong>:Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples in Southeast AsiaAsia Indigenous <strong>Peoples</strong> Pact (AIPP)<strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> (FPP)The Center for People and <strong>Forest</strong>s (RECOFTC)Rights and Resources Initiative (RRI)Copyright © AIPP, FPP, RRI, RECOFTC 2011The contents of this book may be reproduced and distributed for noncommercialpurposes if prior notice is given <strong>to</strong> the copyright holders and thesource and authors are duly acknowledged.Published by <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> (FPP) and Asia Indigenous <strong>Peoples</strong>Pact (AIPP)AIPP: www.aippnet.orgFPP: www.forestpeoples.orgRECOFTC: www.recoftc.orgRRI: www.rightsandresources.orgEdi<strong>to</strong>rs: Marcus Colchester & Sophie ChaoWriters: Marcus Colchester, Ramy Bulan, Jennifer Corpuz, AmityDoolittle, Devasish Roy, Myrna Safitri, Gam Shimray & PrasertTrakansuphakonCover design and layout: Sophie ChaoPrinted in Chiang Mai, Thailand by S.T.Film&PlateCover pho<strong>to</strong>: Inaugural meeting of the SPKS in Bodok, Indonesia/MarcusColchesterISBN: 978-616-90611-7-52

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast Asia3

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast AsiaTable of ContentsAcknowledgments …………………………………………………………6Foreword: Legal pluralism in Southeast Asia – insights from NagalandGam A. Shimray…………………………………………………………….81. <strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: legal pluralism and the rights ofindigenous peoples in Southeast Asia – an introductionMarcus Colchester…...……………………………………………………172. Legal pluralism in Sarawak: an approach <strong>to</strong> cus<strong>to</strong>mary lawson their own terms under the Federal ConstitutionRamy Bulan………………………………………………………………..403. Legal pluralism: the Philippine experienceJennifer Corpuz…………..…………………………………………….….664. Native cus<strong>to</strong>mary land rights in Sabah, Malaysia 1881-2010Amity Doolittle………………...…………………………………………..815. Asserting cus<strong>to</strong>mary land rights in the Chittagong Hill Tracts,Bangladesh: challenges for legal and juridical pluralismDevasish Roy………………………………..……………………………1066. Legal pluralism in Indonesia’s land and natural resourcetenure: a summary of presentationsMyrna A. Safitri.…………………………………………….………...….1267. Securing rights through legal pluralism: communal landmanagement among the Karen people in ThailandPrasert Trakansuphakon…………...…………………………………….133About the authors………………………………………………………...158Bibliography……………………………………...………………………1624

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast Asia5

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast AsiaAcknowledgementsThis volume results from the collaboration of many people and we wouldlike <strong>to</strong> thank in particular Yam Malla, James Bamp<strong>to</strong>n, Panisara Panupitakand Ganga Dahal of the Centre for People and <strong>Forest</strong>s (RECOFTC) forsharing the project with us and Naomi Basik, Nayna Jhaveri, Arvind Khareand Augusta Molnar of the Rights and Resources Group for the financialsupport. As well as the authors of the chapters of this book, we would alsolike <strong>to</strong> recognise the many others who helped develop the thinking on whichthis book is based during the workshop held in Bangkok in September 2010.Participants included: Rital G. Ahmad, Andiko, Dahniar Andriani, JamesBamp<strong>to</strong>n, Toon De Bruyn, Ramy Bulan, Johanna Cunningham, GangaDahal, Amity Doolittle, Christian Erni, Taqwaddin Husein, Nayna Jhaveri,Seng Maly, Bediona Philipus, Anchalee Phonklieng, KittisakRattanakrajangsri, Raja Devasish Roy, Chandra Roy, Myrna Safitri, GamShimray, Rukka Sombolinggi, Somying Soon<strong>to</strong>rnwong, Suon Sopheap,Jennifer Corpuz, Prasert Trakansuphakon and Yurdi Yasmi. We would alsolike <strong>to</strong> thank Professor Philip Lewes of Oxford University for peerreviewing the introduction.Marcus Colchester and Sophie ChaoEdi<strong>to</strong>rs6

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast Asia7

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast AsiaForewordLegal pluralism in Southeast Asia: insights from NagalandGam A. ShimrayIndigenous peoples are among the most his<strong>to</strong>rically ancient living culturesof the world and have over time developed their own distinct bodies of lawsand institutions of social organisation, regulation and control. These lawsand institutions are expressed and practised in ways unique <strong>to</strong> their socioculturalcontexts as self-determining peoples since time immemorial. Today,they are commonly referred <strong>to</strong> as cus<strong>to</strong>mary laws (and practices).Cus<strong>to</strong>mary laws govern community affairs, and regulate and maintainindigenous peoples’ social and cultural practices, economic, environmentaland spiritual well-being. However, cus<strong>to</strong>mary laws and practices andgoverning institutions have come under frequent and repeated attack,leading <strong>to</strong> their severe dis<strong>to</strong>rtion and erosion since the period of conquestand colonisation. This situation has continued with the formation of newStates following decolonisation in more recent times. Prejudices againstindigenous peoples and projects of nation-building have led <strong>to</strong> these peoplesbeing marginalised and the practice of their cus<strong>to</strong>mary laws, culturalpractices, beliefs and institutions has become a criminal offence in manyparts of the world, including Asia.Nonetheless, indigenous peoples throughout the world, <strong>to</strong> varying degrees,still continue <strong>to</strong> regulate their social and cultural practices throughcus<strong>to</strong>mary laws even though they live within State systems. They continue<strong>to</strong> administer their own affairs in accordance with their own systems of law.This is made possible by the recognition of cus<strong>to</strong>mary laws in some nationalconstitutions, even though this recognition is still minimal. It is also madepossible by some circumstantial fac<strong>to</strong>rs, whereby weak States are unable <strong>to</strong>enforce national laws. In some cases, traditional authorities hold greater defac<strong>to</strong> control of local affairs and are able <strong>to</strong> override the application ofrestrictive State laws.8

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast AsiaIn a positive development, and as a result of the growing resistance andassertiveness of indigenous peoples’ movements, recent years have seen amove <strong>to</strong>wards a greater acceptance of legal pluralism as part of the searchfor social order and co-existence. This is true in the context of Asiancountries, particularly Malaysia, Indonesia, Philippines, India andBangladesh. In a number of countries—particularly those mentionedabove—cus<strong>to</strong>m is recognised as a source of rights in the nationalconstitutions. In Sabah and Sarawak, the Bornean States of Malaysia, thereare legal and administrative provisions for the exercise of cus<strong>to</strong>mary lawsthrough native courts. In the Philippines, native title <strong>to</strong> lands is recognisedand it is required <strong>to</strong> obtain the Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) ofindigenous peoples by statu<strong>to</strong>ry law for the implementation of anydevelopment projects or programmes in their lands and terri<strong>to</strong>ries. In theNortheastern part of India, the ownership of land, terri<strong>to</strong>ries and resourcesare vested in the communities <strong>to</strong> varying extents, particularly in Nagaland.Furthermore, in the State of Nagaland, according <strong>to</strong> the law, criminal andcivil disputes can be settled through Naga cus<strong>to</strong>mary laws even in Statecourts. This includes the use of community dispute settlement mechanismsand judicial systems instead of introduced statu<strong>to</strong>ry law.Despite the fact that cus<strong>to</strong>m is an active source of law in Asia, theeffectiveness of its implementation on the ground has remained poor. This isequally true whether there is strong or weak recognition and protection ofcus<strong>to</strong>mary rights and laws in the national Constitution. The problem pointspartly <strong>to</strong> weak actualisation or enforcement and lack of respect forcus<strong>to</strong>mary laws. As long as cus<strong>to</strong>mary law is made subservient <strong>to</strong> positivelaw and is dependent on it for its enforcement, it is unlikely that aharmonious coexistence of both legal systems can be achieved. Thechallenge, therefore, is how can this hierarchical relationship be undone <strong>to</strong>secure the equal enforcement of cus<strong>to</strong>mary laws and positive laws? Andhow can meaningful self-determination, a fundamental right of all peoples,be attained by indigenous peoples?To raise these issues and questions is not <strong>to</strong> negate the move <strong>to</strong>wards legalpluralism but rather <strong>to</strong> explore the full potentiality that legal pluralism as aconcept and practice can offer in the context of concrete experiences on the9

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast Asiaground. Legal pluralism informs us as <strong>to</strong> the ways in which the legalframeworks in which societies operate and develop have met and adapted <strong>to</strong>new challenges and how these frameworks are being used by localcommunities and indigenous peoples <strong>to</strong> respond <strong>to</strong> changing spiritual,moral, cultural, social, economic and environmental conditions. Suchadaptability is required of all legal regimes in order <strong>to</strong> maintain legitimacyand effectiveness and the long term well-being of society. The study andexploration of legal pluralism is still in its infancy and there remains a largegap in our understanding of the modalities and mechanisms for buildingfunctional interfaces between legal regimes in pluri-cultural societies. Inorder <strong>to</strong> address the inherent tensions between cus<strong>to</strong>mary and positive lawsystems, it will be necessary <strong>to</strong> develop greater awareness of the distinctionsbetween them, including their respective nature, objectives, principles andcharacteristics.There are several varying definitions of cus<strong>to</strong>mary law but no universallyaccepted definition. Some anthropologists have referred <strong>to</strong> it as ‘primitivelaw’ and have studied it as a part of legal anthropology, in an effort <strong>to</strong>understand indigenous peoples’ institutions of social control. Furthermore,conceptually speaking, cus<strong>to</strong>mary law has tended <strong>to</strong> be perceived by Statesas formless, astructural and thus unsuited <strong>to</strong> the needs of the modern nationState. 1Moreover, taking the case of the Nagas of Northeast India as an example,most definitions and descriptions of cus<strong>to</strong>mary law have omitted twoimportant dimensions, namely:1. The constitutional law of the village2. Laws regarding inter-village and inter-tribal relationsConstitutional village law pertains in particular <strong>to</strong> the authority of theVillage General Assembly and the Council of Elders. It also concerns the1 Boast 199910

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast Asiadivision of jurisdiction or the division of responsibilities and rights. Thisincludes, for example, the right <strong>to</strong> implement forest fire safety regulationsor the responsibility <strong>to</strong> ensure due observance of certain rituals andrestrictions. Constitutional village law also relates <strong>to</strong> associations, in otherwords, the rights of individuals <strong>to</strong> membership of various socialorganisations such as Long (Youth Clubs), age groups etc. On the otherhand, inter-village and inter-tribal laws relate <strong>to</strong> the strict observance ofrules and conducts of hospitality, security, protection of property and useand maintenance of common resources. The serious omission of thesefundamental dimensions in many definitions reflects a lack of depth inunderstanding the scope, purpose, nature, principles and characteristics ofcus<strong>to</strong>mary laws.There are significant differences between the cus<strong>to</strong>mary laws of indigenouspeoples and positive laws. The distinction is not so much in terms ofcus<strong>to</strong>mary laws not being codified whilst statu<strong>to</strong>ry laws are, as has oftenbeen assumed (i.e. written versus oral traditions). The difference is more interms of the nature, rationale and principles of these two legal frameworks.Cus<strong>to</strong>ms and cus<strong>to</strong>mary laws embody the cosmologies and values ofindigenous societies that have evolved from their primordial relationshipwith the land and the crea<strong>to</strong>r(s) of their cosmos. For example, the notion ofproperty ownership as unders<strong>to</strong>od in western legal systems, where the focusis on the right of the individual and is intrinsically economic in nature, doesnot exist within many indigenous communities. The emphasis withinindigenous communities is placed instead on the sacredness, spirituality andrelational value of resources, and the collective ownership andresponsibilities of property.Such significant differences can be observed in the governance of naturalresources, the execution and maintenance of political and social affairs, orthe administration of justice. To take another example, Guisela Mayen 2states, in reference <strong>to</strong> Mayan law that:2 Mayen 200611

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast AsiaCus<strong>to</strong>mary indigenous law aims <strong>to</strong> res<strong>to</strong>re theharmony and balance in a community; it isessentially collective in nature, whereas thewestern judicial system is based onindividualism. Cus<strong>to</strong>mary law is based on theprinciple that the wrongdoer must compensatehis or her victim for the harm that has been doneso that he or she can be reinserted in<strong>to</strong> thecommunity, whereas the western system seekspunishment.This can be further illustrated with reference <strong>to</strong> the Naga community.Within the Naga community, justice is seen as a means of building amityand unity through consultations and men<strong>to</strong>ring. The arbiter takes the role ofa media<strong>to</strong>r between the parties in dispute in order <strong>to</strong> reconcile them andencourage a healing in their social relations. In cases of grave nature,retribution <strong>to</strong>o occurs, but this is seen as a failure of the entire community.Hence, it is natural that the Council of Elders goes through a process ofinformal consultation and mediation which cross-cuts their social structures,such as family and clan affiliations. As a final resort, cases that areextremely grave in nature and are beyond the wisdom of the elders andcommunity are resolved by seeking the intervention of the Crea<strong>to</strong>r 3 <strong>to</strong>transform the conflict and commence the healing process. In this case, theoutcome is seen more in terms of its utility and healing in order <strong>to</strong> preventthe dispute from affecting the integrity of the community. Unlike ‘positive’law, Naga cus<strong>to</strong>mary laws clearly prioritise reconciliation and socialharmony over redress and punishment.3 The Nagas see the Crea<strong>to</strong>r as the only just and supreme being. They believe thatill-fate will befall those who falsely swear in the name of the Crea<strong>to</strong>r on a sacredplace, or bite a piece of soil in the name of the Crea<strong>to</strong>r, or engage in a contest bytaking the Crea<strong>to</strong>r’s name, etc. For example, in the water submergence contest, bothparties in dispute submerge themselves in water in the name of the Crea<strong>to</strong>r. It isbelieved that the one at fault will float <strong>to</strong> the surface first or drift away from thepoint of submergence. The entire community witnesses such events and the outcomemust be accepted with humility and no party must hold any enmity against the other.12

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast AsiaIn political and social affairs, cus<strong>to</strong>ms and cus<strong>to</strong>mary laws ensure thatdecisions are made by following the principle of consensus in decisionmaking.The basic principle at play is the respect of diversity. Therefore, asthe executive head, the Council takes up issues in the role of facilita<strong>to</strong>r inorder <strong>to</strong> achieve consensus, and not as the enforcer of authority and power.Although indigenous peoples are very varied, a considerable degree ofsocial egalitarianism in cus<strong>to</strong>mary law is evidenced by many traditions ofindigenous communities, including those of the Naga, whereby, the rights ofa free member of their tribe are as respected as the rights of the chiefhimself or herself.In natural resource management among indigenous communities, cus<strong>to</strong>marylaws serve as the primary basis for the regulation of rights, and theapplication and management of their collective knowledge over their landsand resources. Commonly, such management is governed by the principlesof ‘use and care’ (reciprocity), the ‘first owner’ 4 , guaranteed usufruct rights 5of community members and the collective responsibility of the communityfor the protection of individual and common property.In terms of scope, indigenous peoples’ ancestral terri<strong>to</strong>ry determines theextent of jurisdiction and of the application of cus<strong>to</strong>mary laws, but spatialfac<strong>to</strong>rs may not limit the relevance of these cus<strong>to</strong>mary laws in a strictmanner. For example, usufruct rights on the use of natural resources oncommunity lands may be guaranteed <strong>to</strong> neighbouring communities, andhunting grounds may be shared by many indigenous communities withneighbouring social groups. Referring back <strong>to</strong> the example of the Nagas,Naga communities have a very elaborate water-sharing scheme for theiragricultural systems that cross-cuts villages and tribes. According <strong>to</strong> thiswater-sharing system, water must be shared equally and it must be ensuredthat downstream communities are not deprived of it. Additionally,communities living in upstream areas must not inundate the paddy fields of4 An individual who has acquired superior rights <strong>to</strong> or responsibilities for collectiveproperty.5 The legal right <strong>to</strong> use and enjoy the advantages or profits of another person'sproperty.13

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast Asiathe downstream villages through irresponsible management of check-dams.The chain of connections between villages in this sense literally goes rightup <strong>to</strong> the source.Similarly, among the Nagas, wars were fought not for the purposes ofconquest or subjugation. Most were fought in order <strong>to</strong> safeguard family andcommunity honour. It was a cus<strong>to</strong>mary practice within some indigenouscommunities <strong>to</strong> have a friendly village that was bigger or stronger as theprotec<strong>to</strong>r of a weaker or small village. Wars were fought under theobservation of strict cus<strong>to</strong>mary rules, moni<strong>to</strong>red by a neutral party. Highnumbers of casualties were never allowed. There were also rituals for thewell-being of the family or community that were preferably performed byanother village or tribe on their behalf.Various types of conventions exist between villages and tribes, such as thosepertaining <strong>to</strong> security and war, dispute resolution, sharing and managemen<strong>to</strong>f resources, hospitality and rituals. Hence, the notion that cus<strong>to</strong>mary lawsare strictly local is based on the wrong premise. Today, there are tribes thathave established cus<strong>to</strong>mary courts from the village level, up <strong>to</strong> the subregionallevel, and beyond, <strong>to</strong> the highest level court of the tribe.Cus<strong>to</strong>mary law in itself is plural, but in the course of interaction betweencommunities, common elements have developed and have establishedfunctional interfaces across communities. However, the greatest challenge is<strong>to</strong> develop modalities and mechanisms in order <strong>to</strong> move <strong>to</strong>wardsestablishing legal pluralism with positive laws in its truest sense. To beginwith, the fundamental distinguishing principles between the two have <strong>to</strong> bewell unders<strong>to</strong>od. This is not <strong>to</strong> overlook the importance of the his<strong>to</strong>ricalrelationship between cus<strong>to</strong>mary law, positive law and natural law. Thesethree inter-related legal concepts continue <strong>to</strong> play an important role in thelegal order and regulation of many countries, whether formally orinformally.Cus<strong>to</strong>mary law regimes have been and continue <strong>to</strong> be flexible systems oflocal governance capable of adapting <strong>to</strong> the changing needs and realities ofthe societies they govern. However, achieving a genuine recognition of14

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast Asiacus<strong>to</strong>mary laws with a renewed vision of legal pluralism will require strongpolitical will and commitment, particularly at the State level. Theeffectiveness of its operational mechanisms and enforcement will depend onthe level of recognition and au<strong>to</strong>nomy given <strong>to</strong> traditional authorities. Thekey issue will be the extent <strong>to</strong> which institutional arrangements and theapplication of cus<strong>to</strong>mary laws will conform <strong>to</strong> the underlying principles ofindigenous legal regimes and their cultural, spiritual and moral beliefs.Often, even in cases where there is strong recognition of cus<strong>to</strong>mary lawsand au<strong>to</strong>nomy is given <strong>to</strong> traditional authorities, the tendency for Statestructures (based on the principles of positive law) <strong>to</strong> undermine andsupersede traditional governance structures (based on the principles ofcus<strong>to</strong>mary law) remains a serious problem. Frequently, bureaucrats andState agencies, who are ill-equipped <strong>to</strong> handle cus<strong>to</strong>mary procedures, arethe final arbiters or authority in matters concerning communities. They arealso responsible for developing and implementing operational mechanismsfor the implementation of the provisions of the Constitution or State law.The tendency <strong>to</strong> au<strong>to</strong>matically assume that bureaucrats and State agencieshave the knowledge <strong>to</strong> develop appropriate institutional modalities andmechanisms as well as the capacity <strong>to</strong> handle cus<strong>to</strong>mary procedures, defeatsthe very purpose of such constitutional provisions. The result is thebureaucratisation of procedures and the deformation of cus<strong>to</strong>marygovernance structures.A genuine legal pluralism framework will require appropriate institutionalsupport mechanisms that facilitate the restructuring of the fragmented legalorder and governance structures, and nurture its growth in accordance withthe underlying principles of cus<strong>to</strong>mary laws and the cultural, spiritual andmoral beliefs of indigenous communities.This publication is the outcome of a regional consultation with the aim ofgaining better insights in<strong>to</strong> some of the fundamental issues and questionsdescribed above. By shedding light on divers Asian countries’ legalexperiences, it is hoped that this publication will help us better understand,and shape, the future of legal pluralism in this region.15

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast AsiaOn behalf of the Asian Indigenous <strong>Peoples</strong> Pact (AIPP), I would like <strong>to</strong> join<strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> (FPP) in thanking our partners, the Rights andResources Initiative (RRI) and the Centre for People and <strong>Forest</strong>s(RECOFTC) for their support and input <strong>to</strong> the Legal Pluralism workshopheld in 2011. I also extend my thanks <strong>to</strong> the indigenous authors of thechapters of this publication for their valuable contributions and insights in<strong>to</strong>the multi-faceted nature of legal pluralism in Southeast Asia.16

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast Asia1. <strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples in SoutheastAsia – an introductionMarcus Colchester 1IntroductionRecent years have seen a move <strong>to</strong>ward legal pluralism as aninevitable concomitant of social and cultural pluralism. In thefinal analysis such legal pluralism will most likely entail acertain degree of shared sovereignty; but any such suggestionclearly opens up possibilities of conflicts between the differentsources of legal authority. While pluralism offers prospects ofa mosaic of different cultures of co-existence, with parallellegal frameworks, it also presents the danger of a clash ofconflicting norms (between state law and cus<strong>to</strong>marypractices). A true pluralistic society must learn <strong>to</strong> cope withsuch conflicts – searching for a modus vivendi that will allowthe state <strong>to</strong> preserve social order (one of its prime tasks), whileyet assuring its citizens of their legal rights <strong>to</strong> believe in andpractise their own different ways of life.Leon Sheleff in The Future of Tradition. 2The rationale for this book, and the wider project of which it is part, stemsfrom a concern for the future of the hundreds of millions of rural people inSoutheast Asia who still <strong>to</strong>day, as they have for centuries, order their dailyaffairs, and make their livelihoods from their lands and forests, guided bycus<strong>to</strong>mary law 3 and traditional bodies of lore. 4 Many of these indigenous1 Direc<strong>to</strong>r, <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> <strong>Programme</strong>, marcus@forestpeoples.org2 Sheleff 1999:63 International law refers <strong>to</strong> both ‘cus<strong>to</strong>m’ and ‘tradition’ in referring <strong>to</strong> indigenousand tribal peoples’ ways of ordering their social relations and means of production.17

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast Asiapeoples, as they are now referred <strong>to</strong> in international law, have had longhis<strong>to</strong>ries of dealings with various forms of the ‘State’ and indeed their socialorders may be substantially evolved <strong>to</strong> avoid and resist these States’depredations. 5 Yet cultural, political and legal pluralism has also been a longterm characteristic of many of the pre-colonial State polities of SoutheastAsia. 6The rise of post-colonial independent States in the region and thepenetration of their economies by industrial capitalism now pose majorchallenges <strong>to</strong> such peoples. On the one hand their lands, livelihoods,cultures and very identities face unprecedented pressures from outsideinterests. On the other hand they have responded in varied ways <strong>to</strong> asserttheir rights and choose their own paths of development according <strong>to</strong> theirown priorities. With growing assertiveness indigenous peoples have beendemanding ‘recognition’ of their rights <strong>to</strong> their lands, terri<strong>to</strong>ries and naturalresources, <strong>to</strong> control their own lives and order their affairs based on theircus<strong>to</strong>ms and traditional systems of decision-making. The <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong><strong>Programme</strong> supports this movement. 7Yet we are at the same time aware that ‘recognition’ is a sword with twovery sharp edges. ‘Recognition’ of cus<strong>to</strong>mary laws and systems ofgovernance by the colonial powers always came at the price of submission<strong>to</strong> the colonial State’s overarching authority. Acceptance of this authoritywould inevitably lead <strong>to</strong> more interference in community affairs than theideal of nested sovereignties might promise. As Lyda Favali and RoyPateman were driven <strong>to</strong> conclude from their detailed study of legalpluralism in Eritrea:Following Favali and Pateman (2003:14-15), we agree it is not very productive <strong>to</strong>try <strong>to</strong> distinguish between the two, although in the <strong>English</strong> vernacular ‘cus<strong>to</strong>m’ tendsbe considered more labile and evolving than ‘tradition’ which is often consideredmore conservative and inflexible.4 Colchester et alii 20065 Scott 20096 Reid 1995 see especially page 51.7 and see AMAN 200618

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast AsiaThe most serious challenge <strong>to</strong> the survival of traditional landtenure practices came when the state gave formal recognition<strong>to</strong> them. The state was then able <strong>to</strong> demarcate the areas wheretradition was <strong>to</strong> be allowed <strong>to</strong> prevail… Recognition oftraditional practices by the colonial masters was in fact thefirst step in a process of cooptation that eventually renderedlocal authorities less powerful than they had been in the past. 8One rationale for this book is thus <strong>to</strong> remind ourselves of the experiences ofcolonialism and distil some of the main lessons that come from this his<strong>to</strong>ry.How can indigenous peoples <strong>to</strong>day secure the State recognition that theyneed <strong>to</strong> confront the interests moving in on their lands and resourceswithout forfeiting their independence and wider rights?The second rationale is more obvious. It is a matter of law that the majorityof Southeast Asian countries already have plural legal systems. Cus<strong>to</strong>m isrecognised as a source of rights in the constitutions of a number of thesecountries. In some States (like Sabah and Sarawak), there are legal andadministrative provisions for the exercise of cus<strong>to</strong>mary law through nativecourts. In others (like the Philippines), laws require that cus<strong>to</strong>m is taken in<strong>to</strong>account in land use decisions, especially in processes which respectindigenous peoples’ right <strong>to</strong> give or withhold their Free, Prior andInformed Consent <strong>to</strong> actions proposed on their lands. In the Philippines,Sabah, Sarawak and Indonesia, cus<strong>to</strong>m is also recognised in law as a basisfor rights in land (though these provisions are neither implementedeffectively nor widely). Moreover, where common law traditions areobserved such as in the Philippines and Malaysia, the courts haverecognised the existence of native title and aboriginal rights. In variousways, therefore, throughout the region, cus<strong>to</strong>m is a living and active sourceof rights not just in practice but also in law. Yet at the same time the currentreality is that in many countries statu<strong>to</strong>ry laws give very little effectiverecognition of these same rights and only weakly protect constitutionalprovisions. How can indigenous peoples secure better enforcement of8 Favali & Pateman 2003:222-22319

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast Asiatarget groups are the indigenous leadership, supportive lawyers, humanrights commissions and social justice campaigners. The logic is that if forestpeoples in Southeast Asia are <strong>to</strong> achieve effective control of their lands andresources based on rights or claims <strong>to</strong> cus<strong>to</strong>mary ownership, selfgovernanceand the exercise of cus<strong>to</strong>mary law, then policy-makers andcommunity advocates need <strong>to</strong> be clear what they are calling for and howsuch measures will be made effective once and if tenure and governancereforms are achieved.The study also takes in<strong>to</strong> account the studies and consultations beingundertaken with funds from the initiative by Epistema in Jakarta, which hasalready undertaken four case studies in different parts of the archipelago andheld several workshops <strong>to</strong> bring <strong>to</strong>gether insights and experiences relevant<strong>to</strong> legal pluralism in Indonesia. 10Indigenous peoples and cus<strong>to</strong>mary lawSince the time of the Romans and probably before, it has been widelyunders<strong>to</strong>od by jurists that cus<strong>to</strong>m can be more ‘binding than formalregulation, because it was founded on common consent’. 11 An early legalauthority of the Roman period, Salvius Julianus, noted:Ancient cus<strong>to</strong>m is upheld in place of [written] law not withoutreason, and it <strong>to</strong>o is law which is said <strong>to</strong> be founded on habit.For seeing that the statutes themselves have authority over usfor no reason other than they were passed by verdict of thePeople, it is right that those laws <strong>to</strong>o which the Peopleendorsed in unwritten form will have universal authority. Forwhat difference does it make whether the People declares itswill by vote or by the things it does and the facts? 12A working convention once current among anthropologists is that ‘cus<strong>to</strong>m’10 HuMA Learning Centre 2010. The HuMA Learning Centre has now been renamedEpistema.11 Harries 1999:3212 Salvius Julianus cited in Harries 1999:3321

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast Asiatakes on the character of ‘cus<strong>to</strong>mary law’ where infractions arepunishable. 13 Yet, so diverse are societies’ systems of governance thatapplying such general definitions <strong>to</strong> varied realities is bound <strong>to</strong> generateconfusion or uncover imprecisions. The reality is that cus<strong>to</strong>mary law isitself plural.For example, Favali and Pateman in their study of legal pluralism inEritrea, discern three distinct layers of cus<strong>to</strong>mary law, the first being thewritten codes of cus<strong>to</strong>mary law which have developed through a his<strong>to</strong>ry ofdealings with the colonial and post-colonial State, the second being the orallaws which are widely followed by members of the various societies.However they observe that:there is a third body of unrecorded legal rules that are deeplyrooted in a particular system… that constitute the mentality,the way of reasoning about the law, the way of building a legalrule. These rules cannot be verbalised. They form part of anunrecorded and unexpressed background that an outsidercannot understand, and certainly cannot supplant. This is oneof the main aspects of a legal tradition. Tradition is notsomething that has been built or invented overnight. Certainlyit cannot be curbed or abolished on short notice. 14In like vein, Bassi’s study of decision-making among the Oromo-Borana ofsouthern Ethiopia shows how the society’s norms are not codified norotherwise set out in an explicit, logical form, but are expressed in asymbolic and metaphorical way, through myths and rituals, which areinvoked or which otherwise inform judgements and decisions made <strong>to</strong>resolve disputes. 15It seems plausible <strong>to</strong> argue that in Southeast Asia in the ‘pre-modern’ era,where the key <strong>to</strong> power in coastal polities lay with control of labour and13 Gluckman 1977. For the Romans ‘cus<strong>to</strong>m referred <strong>to</strong> law which was usuallyunwritten and which was agreed by “tacit consent”’ (Harries 1999:31).14 Favali & Pateman 2003:21815 Bassi 2005:9922

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast Asiatrade 16 and not the control of land per se, discrete bodies of cus<strong>to</strong>mary lawoperated, in which one body of law regulated trade, slavery and the patronclientrelations through which trade was controlled, while a separate body ofcommunity-controlled law related <strong>to</strong> village affairs, land and naturalresources. 17That there were (and are) multiple layers of cus<strong>to</strong>mary law in the societiesof Southeast Asia is also clear from the wider literature. Changing currentsof belief and varied forms of governance mean that cus<strong>to</strong>mary lawsprimarily based on subsistence-oriented livelihoods have been overlain withcus<strong>to</strong>mary laws related <strong>to</strong> trade and <strong>to</strong> wider polities and in turn overlaidwith cus<strong>to</strong>mary laws derived from ‘world’ religious systems and codes.None of these layers of law are impervious <strong>to</strong> the operations of the otherlayers and studies show how remarkably fast cus<strong>to</strong>mary laws and tenurialsystems can evolve in response <strong>to</strong> migration, market forces and theimpositions of the State. 18Social scientists have been slow <strong>to</strong> understand that indigenous peoples areneither struggling <strong>to</strong> reproduce frozen traditions of their essentialisedcultures nor just responding <strong>to</strong> the racialised violence of the colonial andpost-colonial frontier. Rather they are seeking <strong>to</strong> re-imagine and redefinetheir societies based on their own norms, priorities and aspirations. 19 Inthese processes of revitalisation, and negotiation with the State andneighbouring communities, peoples’ very identities will be reforged. 20 It issuch processes of self-determination which this project seeks <strong>to</strong> inform.Cus<strong>to</strong>m and colonialismDuring the 18 th , 19 th and early 20 th centuries it was the case that throughoutthe region the colonial powers that came in and sought <strong>to</strong> take control of16 Sella<strong>to</strong> 2001; 2002; Magenda 201017 Reid 1995; Warren 1981; Druce 201018 McCarthy 200619 Austin-Broos 2009:1220 Jonsson 2002; Harrell 200123

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast Asiatrade and commerce accepted that these varied bodies of cus<strong>to</strong>mary lawswere <strong>to</strong>o deeply embedded in the lives of the people <strong>to</strong> be supplantedoutright. 21 Policies of indirect rule were thus preferred by all these intrudingpowers including the ‘Han’ Chinese in South West China, 22 the British inIndia, 23 Malaya 24 and Sabah, 25 (as also in Africa), 26 the Brooke Raj inSarawak, 27 the French in Indochina and the Dutch in Indonesia 28 (with thepartial exception of Java).Likewise Islamic law (Shari’ah) is, in its bases (Usul al Fiqh), legally pluralderiving both from the Quran and the sayings (Hadith) ascribed <strong>to</strong>Muhamad by his followers, as well as building on local cus<strong>to</strong>ms (urf). Thus‘Muslim conquerors retained the cus<strong>to</strong>ms and practices of the conquered,merely replacing the leaders and key officials’, 29 as in ‘the early days ofIslam, <strong>to</strong>lerance and freedom of religious life was the norm’. 30 In BuddhistThailand, which retained a greater measure of independence than otherSoutheast Asian countries, the modernising governments of the late 19 thcentury developed a plural legal system <strong>to</strong> better rule their tenuouslysecured domains in the Southwest of the country. 31Policies of indirect rule have been explicitly recognised as the mosteffective means of governing previously independent peoples since the time21 Recognition of cus<strong>to</strong>mary law was intrinsic <strong>to</strong> colonial policies of indirect rule(Sheleff 1999:194).22 Mitchell 2004; Sturgeon 2005. Mien (Yao) peoples of Southern China, Thailand,Laos and Vietnam continue <strong>to</strong> justify their right <strong>to</strong> au<strong>to</strong>nomy in governing their ownaffairs by reference <strong>to</strong> an ancient treaty, the ‘King Ping Charter’, that they signedwith the Chinese at an unrecorded date (Pourret 2002).23 Tupper 188124 Loos 2002:225 Doolittle 2005; Lasimbang 201026 Knight 201027 Colchester 198928 Ter Haar 194829 Hasan 2007:530 ibid. 2007:1131 Loos 200224

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast Asiaof the Romans who used indirect rule <strong>to</strong> annex conquered areas throughtreaties with cities, which included provisions for the operation ofcus<strong>to</strong>mary law especially in the Greek East. 32 Later, the same policy wasapplied in western Europe when ‘ruling barbarians, through barbarians’ wasperceived as the best approach <strong>to</strong> extend power over unruly frontierprovinces. 33As Niccolo Machiavelli famously noted in The Prince:When states, newly acquired, have been accus<strong>to</strong>med <strong>to</strong> livingby their own laws, there are three ways <strong>to</strong> hold them securely:first, by devastating them; next, by going and living there inperson; thirdly by letting them keep their own laws, exactingtribute, and setting up an oligarchy which will keep the statefriendly <strong>to</strong> you... A city used <strong>to</strong> freedom can be more easilyruled through its own citizens... than in any other way. 34Another rationale whereby, in 19 th century colonial India, Africa andSoutheast Asia, plural legal systems were developed was that ‘cus<strong>to</strong>mary’law, rather than the laws of the purportedly secular colonial State, were seenas a more appropriate way <strong>to</strong> deal with issues related <strong>to</strong> family and religion,which were considered sources of local cultural authenticity and best notinterfered with <strong>to</strong>o much. 35However, exactly because recognition of cus<strong>to</strong>mary law implies not just thereinforcement of the laws themselves but also of the power relations andinstitutions through which they are developed, transmitted, exercised andenforced, it is essential <strong>to</strong> examine plural legal systems from both politicaland legal perspectives. Recognition may imply not just the continued32 Harries 1999:32. In this the Romans actually <strong>to</strong>ok the lead from the Greeks whorecognised that each polis (city state) had its own laws, immunities and freedoms,which were not Pan-Hellenic but had <strong>to</strong> be recognised as specific <strong>to</strong> each place(Ober 2005:396).33 Heather 2010; Faulkner 200034 Machiavelli 1513:1635 Loos 2002:525

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast Asiaoperation of cus<strong>to</strong>mary laws but also the cooptation and control of the veryfabric of indigenous society.Cooptation of indigenous elitesFor example in colonial Sarawak, the Brooke Raj recognised and reinforcedthe authority of the hierarchy of cus<strong>to</strong>mary headmen and chiefs – penghulu,pemancha, temonggong, tuah kampong – which permitted the colonialpower <strong>to</strong> control and tax native people right down <strong>to</strong> the village level.Exactly because these leaders’ authority was reinforced by colonial Staterecognition, so the same leaders, over time, became increasinglyindependent of, unaccountable <strong>to</strong>, and detached from, the communitymembers over whom they had authority and whose interests they wereexpected <strong>to</strong> represent. In the post colonial era, the division betweentraditional leaders and village people has, in many communities, proven <strong>to</strong>be a fatal weakness as they seek <strong>to</strong> resist the takeover of their lands bylogging, mining, hydropower projects and plantations. 36Likewise in 19 th century colonial Natal, the small white colonial forcesought <strong>to</strong> control the local African polities though simultaneous recognitionand subjugation. As Knight informs us:...under the ‘Sheps<strong>to</strong>ne system’, which dominated the colony’sadministrative approach for more than half a century, theamakhosi (Zulu leaders) were transformed from au<strong>to</strong>nomousrulers in<strong>to</strong> a layer of the colonial government. They appeared<strong>to</strong> govern their people according <strong>to</strong> traditional law and cus<strong>to</strong>m,but in fact had been through a subtle and profound shift inpower; their dictates were now subject <strong>to</strong> the approval of theNatal legislature and their authority remained unchallengedonly so long as it did not conflict with the broader policies andattitudes of the colonial regime. 3736 Colchester 1989; Colchester, Wee, Wong & Jalong 200737 Knight 201026

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast AsiaCodification and controlIn the Dutch East Indies, the colonial State went further than most not onlyin accepting the operation of plural legal systems but then in seeking <strong>to</strong>regularise and thereby control cus<strong>to</strong>mary law itself. 38 The system wascriticised even at the time for being paternalistic and discrimina<strong>to</strong>ry, withone law for the conquerors and their commercial deals and another for thenatives, whose trade relations had been annexed. 39 The process has alsobeen criticised for freezing cus<strong>to</strong>mary law and thereby denying its essentialvitality, which comes from it being embedded in the life and thought of thepeople. 40As Sheleff in his global review of cus<strong>to</strong>mary law and legal pluralism notes:Any approach that sees cus<strong>to</strong>m – particularly of anotherculture – in static terms, dooms that very culture <strong>to</strong> stagnation,and ultimately rejection, by imposing on it rigidity which isgenerally by no means inherent <strong>to</strong> its nature. 41The freezing of cus<strong>to</strong>m in<strong>to</strong> written codes also allows those who write suchcodes down <strong>to</strong> be highly selective about what they choose <strong>to</strong> include andexclude. This may be done inadvertently but may likewise result fromcensorious officials taking it on themselves <strong>to</strong> decide what aspects ofcus<strong>to</strong>m and cus<strong>to</strong>mary law are useful or acceptable and what aspects aredeemed unacceptable or ‘backward’ (and see ‘repugnancy’ below). In effect,the executives of the colonial State have thereby taken over the role of theindigenous peoples’ equivalents of the legislature. 4238 Ter Harr 1948; Holleman 1981; Hooker 1975; Burns 1989; Lev 200039 Reid 199540 Cf Lasimbang 2010 for a comparable process in contemporary Sabah.41 Sheleff 1999:8542 Cornell & Kalt 199227

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast AsiaThe invention of native courtsIn an effort <strong>to</strong> further systematise the administration of justice, it wascommon practice for the colonial powers <strong>to</strong> institute native courts for theadjudication of cus<strong>to</strong>mary law. Thus in Malaya the British created separateIslamic or cus<strong>to</strong>mary courts for settling cases related <strong>to</strong> religion, marriageand inheritance among Malays. 43 However, the degree <strong>to</strong> which such nativecourts really allowed for the operation of cus<strong>to</strong>mary law is contested. InEritrea,Cus<strong>to</strong>mary law used in native courts derived in some degreefrom traditional law, but was often an emasculated or greatlysimplified version of traditional law; it represented the lawthat the colonial government could <strong>to</strong>lerate or allow spacefor. 44Likewise, in the United States, the Courts of Indian Offenses becameincreasingly controlled by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and regulated by a‘Code of Federal Regulation’. As Deloria and Lyle note:When surveying the literature concerning their operation it isdifficult <strong>to</strong> determine whether they were really courts in thetraditional jurisprudential sense of either the Indian or Anglo-American culture or whether they were not simply instrumentsof cultural oppression since some of the offenses that weretried in these courts had more <strong>to</strong> do with suppressing religiousdances and certain kinds of ceremonials than with keeping lawand order. 45Siam (Thailand) followed the colonial approach by creating Islamic courtsin southern Thailand which function <strong>to</strong> this day. 46 Loos interprets thisrecognition as part of an internal colonial process by which the monarch43 Loos 2002:244 Favali & Pateman 2003:1445 DeLoria & Lyle 1983:11546 Loos 2002:628

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast Asiaused the agenda of reform <strong>to</strong> centralise his power, suppress ethnicminorities, strengthen pre-existing domestic class and gender hierarchiesand secure the interests of the elite- dominated Siamese State. 47Native TitleColonial powers sought where possible <strong>to</strong> obtain access <strong>to</strong> and control ofcommerce and resources without costly recourse <strong>to</strong> violence, though thiswas always a last resort. There is thus a long his<strong>to</strong>ry of colonial States’recognising <strong>to</strong> some degree the rights of indigenous peoples <strong>to</strong> their landsand <strong>to</strong> consent. 48 In common law countries this has led <strong>to</strong> the emergence ofthe notions of ‘native title’ and ‘aboriginal rights’ in land, which accept that‘native’ or ‘backward’ peoples have rights in land based on their cus<strong>to</strong>m. 49The advances made by indigenous peoples since this legal principle gainedwide acceptance in recent years, should not however allow us <strong>to</strong> overlookthe way the colonial State sought <strong>to</strong> limit these rights, as these limits are <strong>to</strong>some extent still with us <strong>to</strong>day. These limitations include: the establishmen<strong>to</strong>f inappropriate systems for land registration and taxation whichdiscouraged indigenous land claims; 50 the requirement that all transfers ofland must first entail the cession of such lands <strong>to</strong> the State and; 51 the layingof the burden of proof of aboriginal rights on the people themselves whohad <strong>to</strong> prove continuing occupancy or at least the continuing exercise ofcus<strong>to</strong>mary law over the land. 52Moreover, colonial laws and regulations frequently sought <strong>to</strong> minimiserights in land, diminishing them <strong>to</strong> little more that rights of usufruct on47 ibid. 2002:1548 For a short summary see Colchester & MacKay 2004. The courts established in1832 that a European nation could only claim title <strong>to</strong> land if the indigenous peopleconsented <strong>to</strong> sell (McMillan 2007:90).49 Lindley 192650 Doolittle 200551 ibid. 2005:22-26; McMillen 200752 Culhane 199829

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast AsiaCrown land, which were limited both in extent and in the bundle of rightsassociated with them. On the one hand, the fact that colonial powersrecognised indigenous peoples’ rights in land at all should be seen as apositive thing, but on the other hand the way this notion of native title washemmed in with conditions, limitations and restrictive interpretation couldalso be seen as a legal fiction <strong>to</strong> allow the colonial powers exclusive rightsover native lands. Until 1941 in the USA, the government held that ‘Indiantitle was mere permission <strong>to</strong> use the land until some other use was found forit’. 53Some of these limitations are still with us <strong>to</strong>day. McMillen notes that‘cus<strong>to</strong>mary law can become a trap if, as is becoming the tendency inAustralia, recognition of Aboriginal Title is made conditional on thecontinuing practice of unchanged traditional law’. 54 A ground-breakingstudy looking in<strong>to</strong> the social effects on Native Title in Australia exposessome of the difficulties Aboriginal peoples have had in securing their rights,given the way that the courts have circumscribed the concept. The variouscases show, for example, that titles may have been considered <strong>to</strong> beextinguished where they have been subsequently overlain by titles granted<strong>to</strong> others; be considered void if cus<strong>to</strong>m is judged <strong>to</strong> be attenuated; bediscounted if the Aboriginal descendants are judged <strong>to</strong> be of mixed blood.Landowners also find that the way the law is applied may provoke newinstitutions <strong>to</strong> replace prior ones, simplify or misrepresent peoples’connections with ‘country’ (their terri<strong>to</strong>ries), limit or constrain the exerciseof cus<strong>to</strong>mary law, provoke contests between claimant groups, lead <strong>to</strong> thecodification of cus<strong>to</strong>mary law as part of claims processes and given greaterweight <strong>to</strong> written testimonies than oral statements. 55Even though, the study concludes, overall the recognition of Native Titlehas been positive for Aboriginal peoples compared <strong>to</strong> the alternative of nonrecognition,nevertheless since the Native Title Act was passed:53 McMillen 2007:14954 ibid.:18255 Smith & Morphy 200730

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast Asiamany Indigenous Australians have become increasinglyunhappy with both the strength and forms of recognitionafforded <strong>to</strong> traditional law and cus<strong>to</strong>m under this Act, as wellas the socially disruptive effects of the native title process. 56Specific experiences show that while the courts may confer rights in landthis does not mean they confer meaningful self-determination ‘in the senseof the recognition of the jurisdiction’ of cus<strong>to</strong>mary law, thus imposing thewestern distinction between title <strong>to</strong> own lands and sovereignty <strong>to</strong> controlthem. 57Between self-determination and State sovereigntyThe reason for rehearsing these experiences with colonialism is that thesesame laws, practices and legal doctrines still prevail in many post-colonialStates. On the other hand, it is true that many indigenous peoples <strong>to</strong>day arein very different circumstances from these times. By means of mobilisationand assertive action, and above all through the revitalisation and reinventionof indigenous institutions, they have been able <strong>to</strong> turn the limited optionsoffered by the recognition of cus<strong>to</strong>mary law, aboriginal title, selfgovernanceand native courts in<strong>to</strong> opportunities <strong>to</strong> regain control of theirlands and lives. 58 Examples of this emerge from the experiences presentedin the following chapters. Nevertheless, the pitfalls in legal andadministrative procedures are still there and pose a challenge <strong>to</strong> the unwary.Papua New Guinea (PNG) provides a good example of why indigenouspeoples need <strong>to</strong> be vigilant. Whereas cus<strong>to</strong>mary rights in land in PNG arerecognised in statu<strong>to</strong>ry law, meaning that some 97% of the national terri<strong>to</strong>ryis supposedly under native title, nevertheless it is estimated that some 5.6million hectares of clan lands, some 11% of the terri<strong>to</strong>ry of PNG, have beenfraudulently taken over by logging, mining and plantation companiesthrough contested leases of the clans’ lands <strong>to</strong> third parties, as Special56 ibid.:24.57 Morphy 2007:32.58 Yazzie 1994, 1996; Zion & Yazzie 1997.31

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast AsiaAgricultural and Business Leases (SABL), which have been permitted byState agencies largely due <strong>to</strong> manipulations in the way indigenousinstitutions and land-owner associations have been recognised (or ignored)by government officials. 59 These kinds of manipulations largely explainwhy the indigenous peoples in PNG are now refusing <strong>to</strong> agree <strong>to</strong> agovernment scheme <strong>to</strong> title their lands, as they are convinced that similarmanipulations will ensue which will limit or misallocate clan lands andopen the way <strong>to</strong> other interests.Peru is currently engaged in a similar debate. In the aftermath of bloodyconflicts over land and resources in 2009, the Government has passed a billthrough the Congress which seeks <strong>to</strong> set out how the State will observe ILOConvention 169, <strong>to</strong> which it is a signa<strong>to</strong>ry, with respect <strong>to</strong> the right <strong>to</strong>consultation. 60 The law however, while repeating the provisions of theConvention (which recognises the right of indigenous peoples <strong>to</strong> representthemselves ‘through their own institutions and representative organisations,chosen in accordance with their traditional cus<strong>to</strong>ms and norms’ 61 ), then setsout procedures by which the State will recognise and list these authorities.These limitations are similar <strong>to</strong> those found in the Constitution and laws inIndonesia, which recognise indigenous peoples and some rights, ‘so long asthese peoples still exist’, thereby giving the State the discretion <strong>to</strong> determinewhen or whether <strong>to</strong> recognise the people or not.Even in the operations of the courts a trend is discernible for the rule of lawby the State <strong>to</strong> have gradually expanded, just as the capacity andindependence of the judiciary has increased, and for the legislature <strong>to</strong> passlaws which increasingly restrict the exercise of cus<strong>to</strong>mary law. This isparticularly noticeable in laws directed at conservation and the management59 CELCOR, BRG, GP(Aus) & FPP 2011; Filer 201160 Ley del Derecho a Consulta Previa a los Pueblos Indigenas u OriginariosReconocido en el Convenio No. 169 de la Organizacion Internacional del Trabajo.Ms. (May 2010).61Op cit Article 6 translation from the Spanish by the author. ILO 2009 also setsout a number of examples of how international laws have been used <strong>to</strong> limit theexercise of cus<strong>to</strong>mary law.32

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast Asiaof natural resources which tend <strong>to</strong> place restrictions on cus<strong>to</strong>mary systemsof land use and management just as they are recognised. The trend of‘bureaucratising biodiversity’, as I refer <strong>to</strong> it, actually has the effect oftaking control out of the hands of communities and empowering Stateagents authorised <strong>to</strong> oversee ‘community forests’ and ‘co-managed’protected areas.As Favali and Pateman note, aspects of law which had often been left <strong>to</strong>cus<strong>to</strong>m – such as religious practice, land, marriage and personal ethics – arenow increasingly regulated through statu<strong>to</strong>ry law, by the administration andthrough the operations of the courts. Yet, as they note,Further dilemmasparadoxically it is traditional law which is more flexible in theface of change. While statu<strong>to</strong>ry law requires legal revisionthrough executive and legislative acts, cus<strong>to</strong>mary lawconstantly realigns through the interpretative acts of society.Even common law legal traditions cannot match itsdynamism. 62There are several other major dilemmas with the assertion and recognitionof cus<strong>to</strong>mary law which deserve mention. These include:• The challenge of freezing tradition even as indigenous peoplesthemselves take control of their systems of law and codify their owncus<strong>to</strong>m.• The challenge of clarifying the jurisdiction of cus<strong>to</strong>mary law systems:over which areas and persons do these systems apply; what happens ifdisputes are between indigenous and non-indigenous persons; what is <strong>to</strong>prevent plaintiffs and defendants ‘forum shopping’ <strong>to</strong> find the court mostfavourable <strong>to</strong> them; is that a problem; how do you avoid double jeopardy ordouble punishment from multiple courts; what crimes or <strong>to</strong>rts should be62Favali & Pateman 2003:21533

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast Asiareferred <strong>to</strong> State or federal courts? These are some of the main issuesaddressed by legal specialists examining legal pluralism. 63Between recognition and repugnancyWhen indigenous peoples made recourse <strong>to</strong> the international human rightssystem in 1977 <strong>to</strong> commence the process of gaining recognition of theirrights at the international level, which led after thirty years of sustainedadvocacy <strong>to</strong> the UN General Assembly’s adoption of the UN Declaration onthe Rights of Indigenous <strong>Peoples</strong>, it brought with it a challenge of adifferent kind. By demanding that the international human rights regimegive recognition of their rights, indigenous peoples thereby subscribed <strong>to</strong>these rights and accepted that they themselves should observe theirapplication in their own societies. The principle was explicitly accepted byindigenous representatives negotiating the text of ILO Convention 169 inGeneva in 1989. The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous <strong>Peoples</strong> isalso explicit on this point. 64The question then arises, if indigenous peoples have cus<strong>to</strong>ms, laws orpractices that are seen <strong>to</strong> be violations of human rights, how are these <strong>to</strong> beaddressed? The subject is a delicate one, especially for those of us who arenot indigenous! Favali and Pateman note:It is virtually impossible <strong>to</strong> engage in a critique of traditionand not be accused a priori of being imperialist, or guilty ofcondemna<strong>to</strong>ry language and action. 65Yet, it needs <strong>to</strong> be recognised that the State itself has a duty <strong>to</strong> protecthuman rights, even against the abusive application of cus<strong>to</strong>mary law or6364See bibliography for some relevant sources.The universality of the UN human rights regime has frequently been contested.Indeed the American Anthropological Association itself denounced the UNDeclaration of Human Rights in 1948 on the grounds that it was <strong>to</strong>o western andindividualist in its conception and ignored more collective notions of freedom, rightsand justice of other societies.65Favali & Pateman 2003:19534

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast Asiareligious courts.Indeed it was concern with exactly these duties which was used by colonialadministra<strong>to</strong>rs and justices <strong>to</strong> legitimise their interference in cus<strong>to</strong>mary law.Perceived abuses such as slavery, human sacrifice, cruel and unusualpunishment, witchcraft, unjust property laws, polygamy and female genitalmutilation (FGM) were considered ‘repugnant’ and on these grounds couldbe justly extirpated, by force if necessary. Indeed, in India, colonialinterventions <strong>to</strong> prevent human sacrifice were used as a justification for thewholesale takeover of tribal areas by force, and resulted in huge numbers oftribal people being killed ostensibly <strong>to</strong> save the lives of a few dozen. 66Contrarily, cases are noted where westerners imposed the death penalty,even in societies where this was considered excessive. 67 Indeed, such wasthe prejudice against the ‘backward’ ways of tribal peoples, that it was notrare that the entire upbringing of a child under native cus<strong>to</strong>m wasconsidered ‘repugnant’, justifying the separation of children from theirparents and their being sent <strong>to</strong> boarding schools <strong>to</strong> be brought up <strong>to</strong>understand ‘civilised’ values. 68 Such practices were the norm in NorthAmerica and Australia in the 19 th and early 20 th century, but as late as the1990s government programmes in Irian Jaya pursued the same approach. 69Of course, some of the limitations on cus<strong>to</strong>mary systems imposed in thename of human rights are now widely accepted. Slavery, suttee and humansacrifice have few defenders. Other impositions however are far from beingso widely accepted. A controversial case is that of Female GenitalMutilation (FGM) which was recognised as an expression of violenceagainst women at the UN First World Conference on Human Rights inVienna in 1993 and yet has many defenders as a traditional practice in manysocieties, including by women. FGM was expressly forbidden by the Fourth66676869Padel 1996Sheleff 1999:124Adams 1995; Sheleff 1999:162See also Li 2007 for other cases of Indonesian government intervention in thelives of ‘estranged tribes’.35

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast AsiaWorld Conference on Women held in 1995 which invoked the Conventionof the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). YetCEDAW has also been invoked as a justification for the breakup ofcollective lands on the grounds that land should be titled equally <strong>to</strong> men andwomen.The issue that needs clarifying is who defines, and then who acts <strong>to</strong>extirpate, ‘bad cus<strong>to</strong>m’ and how is this reconciled with the right <strong>to</strong> selfdetermination.With respect <strong>to</strong> cus<strong>to</strong>ms that discriminate against women forexample, the ‘Manila Declaration’ of indigenous peoples has acknowledgedthat:... in revalidating the traditions and institutions of ourances<strong>to</strong>rs it is also necessary that we, ourselves, honestly dealwith those ancient practices, which may have led <strong>to</strong> theoppression of indigenous women and children. However, theconference also stresses that the transformation of indigenoustraditions and systems must be defined and controlled byindigenous peoples, simply because our right <strong>to</strong> deal with thelegacy of our own cultures is part of the right <strong>to</strong> selfdetermination.70Untangling the triangle: ways forward for indigenous peoplesThis short paper has tried <strong>to</strong> set out some of the dilemmas that need <strong>to</strong> beconfronted by those trying <strong>to</strong> make use of the reality of legal pluralism <strong>to</strong>secure justice for indigenous peoples. We see that three bodies of law (withtheir many subsidiary layers) are operating in relative independence of eachother – cus<strong>to</strong>mary law, State law and international law. Societies organisedthrough cus<strong>to</strong>mary law have his<strong>to</strong>rically been confronted by the dualimposition of statu<strong>to</strong>ry laws and international laws, which, by and large,70 The Manila Declaration of the International Conference on Conflict Resolution,Peace Building, Sustainable Development and Indigenous <strong>Peoples</strong>, organised andconvened by Tebtebba Foundation (Indigenous <strong>Peoples</strong>’ International Centre forPolicy Research and Education) in Metro Manila, Philippines on December 6 – 82010. Available at: 36

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast Asiahave been mutually reinforcing and have justified severe limitations of therights and freedoms of indigenous peoples.The international human rights regime that was set in place at the end ofSecond World War was, in large part, developed as a reaction against theabuses of State policies which had discriminated against and sought <strong>to</strong>exterminate whole peoples. The Atlantic Alliance, which was formed duringthe war itself as a counter <strong>to</strong> the Axis powers, emphasised the collectiveright <strong>to</strong> self-determination and gave rise <strong>to</strong> the United Nations as a union ofmember States resolved ‘<strong>to</strong> develop friendly relations among nations basedon respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination ofpeoples’. 71 An early expression of this resolve was thus the adoption of theConvention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide of1948. 72However, the International Covenants laboriously developed during theCold War, as the ‘first generation’ and ‘second generation’ of human rights,gave emphasis first <strong>to</strong> the civil and political rights of individuals against theState, in line with the social contracts that are perceived <strong>to</strong> underlie westerndemocracies, and second <strong>to</strong> the economic, social and cultural rights ofindividuals that socialist States in particular sought <strong>to</strong> uphold throughcentralised government control. Thus whereas both these Covenants gavestrong recognition of the right of all peoples <strong>to</strong> self-determination, they gavelittle further recognition of collective rights. Their effect was thus <strong>to</strong>reinforce the rule of positive law over cus<strong>to</strong>m and facilitate both privateproperty and State control.It has been the extraordinary achievement of indigenous peoples during thelate 20 th and early 21 st centuries <strong>to</strong> have successfully challenged this legalprism and ensure that greater emphasis is given <strong>to</strong> collective human rights. 73International law thus recognises the rights of indigenous peoples including,most pertinent for this study, their rights <strong>to</strong>; self-determination; <strong>to</strong> own and71 Charter of the United Nations.72 UN 1994:67373 For a critical review see Eagle 2011.37

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast Asiacontrol the lands, terri<strong>to</strong>ries and natural resources they cus<strong>to</strong>marily own,occupy or otherwise use; <strong>to</strong> represent themselves through their owninstitutions; <strong>to</strong> self-governance; <strong>to</strong> exercise their cus<strong>to</strong>mary law and; <strong>to</strong> giveor withhold their free, prior and informed consent <strong>to</strong> measures which mayaffect their rights. Indigenous peoples are now practised at invokinginternational law <strong>to</strong> support reforms of State laws so they recogniseindigenous peoples’ rights in line with countries’ international obligationsand in ways respectful of their cus<strong>to</strong>mary systems.Western individualist laws: 1 st and 2 nd generation human rights3 rd generation human rights38

<strong>Divers</strong> <strong>Paths</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Legal pluralism and the rights of indigenous peoples inSoutheast AsiaThis reconfiguration of human rights thus poses a challenge <strong>to</strong> States whoselaws and policies discriminate against indigenous peoples and other peopleswho make up the populations of their countries. By insisting that thesepeoples’ collective rights must also be recognised, secured and protected bylaw, international laws and judgements have reaffirmed the validity ofcus<strong>to</strong>mary rights and the relevance of cus<strong>to</strong>mary law. A substantial volumeof jurisprudence has emerged in the UN treaty bodies, at the Inter-AmericanCommission and Court of Human Rights and, more recently, at the AfricanCommission on Human and <strong>Peoples</strong>’ Rights, which sets out how theserights need <strong>to</strong> be respected and which instruct and advise nationalgovernments on how <strong>to</strong> reform national laws and policies in line withcountries’ international obligations. 74Indeed even during the 1990s, the progressive recognition of indigenouspeoples’ collective rights in international law in response <strong>to</strong> the claims ofthese peoples and pressure from supportive human rights defenders alreadyled many States, especially in Latin America, <strong>to</strong> revise their constitutions,legal frameworks and in particular their land tenure laws <strong>to</strong> accommodatethese rights. 75 The accompanying papers in this volume explore some of thechallenges now being faced in Southeast Asia <strong>to</strong> reconcile these bodies oflaw.There is however some way <strong>to</strong> go before it is generally accepted that:Cus<strong>to</strong>m, then, far from being a problematic aspect of tribal lifein the context of the modern world, becomes an integral aspec<strong>to</strong>f a legal system, not an artificial addition reluctantlyconceded, but an essential component of a meaningful law thatis accepted by the citizenry, because it is deeply embedded intheir consciousness as a living part of their culture. 7674 MacKay (ed.) 2005-2011: four volumes.75 Griffiths 200476 Sheleff 1999:8739