The Snitch System - The Innocence Project

The Snitch System - The Innocence Project

The Snitch System - The Innocence Project

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Northwestern University School of LawCenter on Wrongful Convictions<strong>The</strong> <strong>Snitch</strong> <strong>System</strong>HOW SNITCH TESTIMONY SENT RANDY STEIDL ANDOTHER INNOCENT AMERICANS TO DEATH ROWA CENTER ON WRONGFUL CONVICTIONS SURVEYWINTER 2004–2005Center on Wrongful Convictionswww.law.northwestern.edu/wrongfulconvictionsBLUHM LEGAL CLINICA world-renowned program of the Bluhm Legal Clinicat Northwestern University School of Law

By way of background...<strong>The</strong> history of the snitch is long and inglorious,dating to the common law. In old England, snitcheswere ubiquitous.<strong>The</strong>ir motives, then as now, wereunholy. In the 18th Century, Parliament prescribedmonetary rewards — blood money — for snitches,who were turned back onto the streets wherethey were, in the words of one contemporarycommentator,“the contempt and terror of society.”<strong>The</strong> system produced a cycle of betrayal in whicheach snitch knew he might find himself soon in thedock confronted by another snitch. An examplewas the case of Charles Cane, who had providedevidence that sent two men to their deaths in 1755.A few months later, a snitch did unto him as hehad done unto others. After Cane was hanged atTyburn in 1756, the clergyman who ministered tohim explained that Cane had expected “nothingless than hanging to be his fate at last, but not of theevil day’s coming so soon.”If all cases ended so poetically, perhaps informantdependentprosecutions would be more humorousthan objectionable. In real life, however, O. Henryendings are rare. Consider Joshua Kidden, who cameto a decidedly unpoetic end — convicted andhanged in 1754 for the highway robbery of oneMary Jones. After the execution, it was discoveredthat Mary was a member of a conspiracy tocollect blood money.A cohort planted a coin on thehapless mark, another apprehended him, and Maryidentified the coin as hers.<strong>The</strong> conspirators netted£140 per case, at the expense of an untold numberof innocent lives.<strong>The</strong> snitch system probably arrived in the NewWorld with the Pilgrims.<strong>The</strong> first documentedwrongful conviction case in the United Statesinvolved a snitch.<strong>The</strong> case arose in Manchester,Vermont, in 1819. Brothers Jesse and StephenBoorn were suspected of killing their brother-in-law,Russell Colvin. Jesse was put into a cell witha forger, Silas Merrill, who would testify that Jesseconfessed. Merrill was rewarded with freedom.<strong>The</strong> Boorn brothers were convicted and sentencedto death but saved from the gallows when Colvinturned up alive in New Jersey.Artist’s depiction of Russell Colvin’s murder,as imagined by a jailhouse snitch in 1819America’s most infamous snitch, Leslie VernonWhite, happened along 170 years later in California.A career criminal,White faked confessions in dozensof cases, worming details about the cases out ofpolice and prosecutors by telephone from jail. In aninterview on Sixty Minutes,White joked thatthe snitch system had spawned slogans:“Don’t go tothe pen, send a friend” and “If you can’t do thetime, just drop a dime.”<strong>The</strong> experience shows pretty much what you wouldexpect — that when the criminal justice systemoffers witnesses incentives to lie, they will.This report was researched and written by Rob Warden,Executive Director, Center on Wrongful ConvictionsDesign: Joanna Wilkiewicz.Copyright © 2004, Northwestern UniversityCREDITSIllustrations:This page by an anonymous illustratorof <strong>The</strong> Dead Alive, a novel by Wilkie Collins based on theBoorn-Colvin case and published in the United States by Shepardand Gill, 1874; Page 15 by Rob Warden.Photographs: Cover by Kevin German. Facing page by (variously)Loren Santow, Andrew Lichtestein,Taryn Simon, and JenniferLinzer; Pages 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11 by Loren Santow; Page 12by Jennifer Linzer. Page 13 courtesy of the Illinois Departmentof Corrections.2

<strong>Snitch</strong> Testimony is the Leading Causeof Wrongful Convictions in Capital CasesNational Roster of Death Row<strong>Snitch</strong> VictimsRandall Dale AdamsSentenced to death in 1977 for the murderof a police officer during a traffic stop inDallas. <strong>Snitch</strong>:<strong>The</strong> actual killer who receivedimmunity from prosecution in exchange fortestifying. Exonerated by: Killer’s recantation.Years lost: 13Joseph AmrineSentenced to death in 1986 for the murder ofa fellow prisoner in Missouri. <strong>Snitch</strong>es:Twoprisoners who claimed they saw Amrine killthe victim and a third who claimed Amrineadmitted it. Exonerated by: Recantations byall three prisoners and exculpatory affidavitsfrom two others.Years lost: 10Gary BeemanSentenced to death in 1976 for a murder inOhio. <strong>Snitch</strong>:A prison escapee, who claimedhe saw Beeman with the victim aroundthe time of the crime and later with blood onhis clothes. Exonerated by: Five witnesseswho testified the snitch told them Beemanhad nothing to do with the crime.Years lost: 4Dan L. BrightSentenced to death in 1996 for a murderin New Orleans. <strong>Snitch</strong>:A felon who testifiedin anticipation of leniency. Exonerated by:Disclosure of a suppressed FBI reportindicating someone else committed the crime.Years lost: 8Anthony Siliah BrownSentenced to death in 1983 in Florida.<strong>Snitch</strong>:<strong>The</strong> actual killer, who testified againstBrown in exchange for leniency. Exoneratedby: Killer’s recantation at Brown’s retrial.Years lost: 3<strong>The</strong>se men are among 51 nationally who have been exonerated of crimes for whichthey were sentenced to death based in whole or part on the testimony of witnesseswith incentives to lie — in the vernacular, snitches. For the most part, the incentivisedwitnesses were jailhouse informants promised leniency in their own cases or killerswith incentives to cast suspicion away from themselves. In all, there have been 111death row exonerations since capital punishment was resumed in the 1970s.<strong>The</strong> snitch cases account for 45.9% of those.That makes snitches the leading cause ofwrongful convictions in U.S. capital cases — followed by erroneous eyewitnessidentification testimony in 25.2% of the cases, false confessions in 14.4%, and falseor misleading scientific evidence in 9.9%.Shabaka BrownSentenced to death in 1974 for a robbery andmurder in Florida. <strong>Snitch</strong>:A criminal whotestified that he waited outside in a car while,unbeknownst to him, Brown committed thecrime. Exonerated by:<strong>The</strong> snitch’s admissionthat he fabricated the testimony in exchangefor a previously undisclosed promise ofleniency.Years lost: 143

Verneal JimersonNational RosterWillie A. Brown and Larry TroySentenced to death in 1984 for the murderof a fellow prisoner in Florida. <strong>Snitch</strong>:A prisoner who testified that he saw Brownand Troy leave the victim’s cell shortlybefore his body was discovered. Exoneratedby:A surreptitiously recorded admission fromthe snitch that he had lied about the twomen’s involvement.Years lost: NoneAlbert Ronnie Burrelland Michael Ray Graham Jr.Sentenced to death in 1987 for a doublemurder in Louisiana. <strong>Snitch</strong>:A prisoner whoclaimed Graham admitted committing thecrime with Burrell. Exonerated by:Prosecution’s admission that the snitch lied.Years lost: 13 (each)Joseph BurrowsSentenced to death in 1989 for the robberyand murder of an elderly farmer inIllinois. <strong>Snitch</strong>:<strong>The</strong> actual killer. Exoneratedby: Killer’s confession.Years lost: 6Earl Patrick CharlesSentenced to death in 1975 for a doublemurder in Georgia. <strong>Snitch</strong>:A jailhouseinformant. Exonerated by: Proof that Charleshad been at work when the crime occurred.Years lost: 4Perry Cobb and Darby TillisSentenced to death in 1979 for a doublemurder in Chicago. <strong>Snitch</strong>:A woman whoportrayed herself as an unwitting accomplice.Exonerated by:A prosecutor’s testimony thatthe snitch had told him that her boyfriendcommitted the crime.Years lost: 10 (each)James CreamerSentenced to death in 1973 for a doublemurder in Georgia. <strong>Snitch</strong>:A purportedaccomplice granted immunity from prosecution.Exonerated by: Discovery of tapes withheldat the trial showing that the snitch alone hadcommitted the crime.Years lost: 3In what would become known as the Ford Heights Four case,Verneal Jimerson wasconvicted in 1985 of a double murder in south suburban Chicago. His convictionrested on the testimony of a purported accomplice, Paula Gray.Before Gray agreed to testify, the other members of the Ford Heights Four —Dennis Williams,Willie Rainge, and Kenneth Adams — had been convicted based onother snitch testimony.Williams was sentenced to death, Rainge and Adams tolong prison terms.After Williams and Rainge were granted a new trial, Gray also testified against them,leading to their re-convictions and reimposition of their sentences in 1986. Inexchange for her testimony, Gray was released from prison, where she was serving50 years for her supposed role in the case.A decade later, the Ford Heights Four were exonerated by confessions of the actualkillers corroborated by DNA testing. In 1999, Cook County agreed to pay$36 million to settle lawsuits filed on behalf of the men.That was, and is, the largestcivil rights settlement in U.S. history.Robert Charles CruzSentenced to death in 1981 for a doublemurder in Arizona. <strong>Snitch</strong>:A convictedburglar given immunity in exchange for histestimony. Exonerated by:Acquittal uponretrial.Years lost: 144

Gordon (Randy) SteidlWhen Randy Steidl walked free from the IllinoisCorrectional Center at Danville on May 28, 2004,he became the 18th man to be exonerated andreleased after having been sentenced to death underthe current Illinois capital punishment law. Hisexoneration resulted from new evidence establishingthat he and a co-defendant, Herbert Whitlock, wereinnocent of the murder of newlyweds Karen andDyke Rhoads, whose bodies were discovered onJuly 6, 1986, in their burning home in Paris, Illinois.<strong>The</strong> convictions rested on the testimony of twoinformants — Debra Reinbolt and DarrellHerrington, who claimed to have been presentwhen Steidl and Whitlock repeatedly stabbed thevictims and set their home afire.<strong>The</strong> evidenceagainst Steidl also included the testimony of ajailhouse snitch, Ferlin Wells, who claimed Steidlconfided that, if he had thought Herringtonwould come forward,“he would have definitelytaken care of him.”Steidl was exonerated after it was discovered that aknife that Reinbolt had testified was the murderweapon in fact was not — its blade was too short tohave inflicted the wounds — that a lamp in thevictims’ bedroom that Reinboldt testified had beenbroken during the crime actually was broken byfiremen after they extinguished the fire, and thattime-sheets and witnesses from the hospital whereReinboldt worked established that she couldnot have witnessed the crime because she was atwork when it occurred.For a more complete account of the Steidl case, pleasesee the reprint of the Springfield Journal-Register seriesaccompanying this report.5

Joseph BurrowsNational RosterRolando Cruzand Alejandro HernandezSentenced to death in 1985 for the kidnaping,rape, and murder of a little girl in Illinois.<strong>Snitch</strong>es: Six informants, four of whomclaimed Cruz admitted the crime and two ofwhom claimed Hernandez did. Exoneratedby: DNA indicating the killer was aman who confessed that he alone committedthe crime.Years lost: 12 (each)Muneer DeebSentenced to death in 1985 for the contractmurder of a woman in Texas. <strong>Snitch</strong>:A jailhouse informant who testified that analleged co-conspirator of Deeb’s had admittedthe murder-for-hire scheme. Exonerated by:Acquittal upon retrial.Years lost: 8Charles Irvin FainSentenced to death in 1983 for kidnaping,sexually assaulting, and drowning a9-year-old girl in Idaho. <strong>Snitch</strong>es:Twojailhouse informants. Exonerated by: DNA.Years lost: 18Neil FerberSentenced to death in 1982 for a doublemurder in Philadelphia. <strong>Snitch</strong>:A jailhouseinformant who claimed Ferber had confessed.Exonerated by: Informant’s recantationand discovery of a police conspiracy to frameFerber.Years lost: 5Gary GaugerSentenced to death in 1994 for the murder ofhis parents in Illinois. <strong>Snitch</strong>:A jailhouseinformant who testified that Gauger repeatedlyadmitted the crime. Exonerated by: Discoverythat a Wisconsin motorcycle gang committedthe crime.Years lost: 2<strong>The</strong> body of William Dulan, an 88-year-old retired farmer, was found onNovember 8, 1988, at his home in Sheldon, Illinois. Hours later, Gayle Potter, acocaine addict, tried to cash a check in Dulan’s name and was arrested.<strong>The</strong>rewas a gash on Potter’s head and blood consistent with hers was found at the scene.<strong>The</strong> murder weapon was recovered from her.<strong>The</strong> situation looked bad for Potter, until she implicated Burrows and a mildlyretarded friend of his, Ralph Frye. No physical evidence linked either man to thecrime, and four witnesses placed Burrows 60 miles away when it occurred. Aftera lengthy interrogation, however, Frye corroborated Potter’s version of events.Burrows was sentenced to death, after which Potter and Frye were sentenced30 and 27 years respectively. (Under an Illinois day-for-day good time policy thenin effect, they would serve only half that time.) Two years later, both recantedand Burrows was granted a new trial. Potter then admitted under oath that she alonecommitted the crime, and the prosecution dismissed the charges.Alan GellSentenced to death in 1998 for a murderin North Carolina. <strong>Snitch</strong>es:<strong>The</strong> actual killerswho were allowed to plead to second-degreemurder in exchange for their “truthfultestimony” against Gell. Exonerated by:New alibi evidence.Years lost: 9Charles Ray GiddensSentenced to death in 1978 for a murderin Oklahoma. <strong>Snitch</strong>:A man whom policeinitially had arrested for the crime. Exoneratedby: Dismissal of charges after the OklahomaCourt of Criminal Appeals ordered a newtrial.Years lost: 46

Steven SmithNational RosterLarry HicksSentenced to death in 1978 for a doublemurder in Indiana. <strong>Snitch</strong>es: Two womenwho claimed to be eyewitnesses. Exoneratedby:<strong>The</strong> women’s recantations.Years lost: 2Madison HobleySentenced to death in 1990 for an arson firethat claimed seven lives in Chicago. <strong>Snitch</strong>:A suspect in another arson fire in thesame neighborhood. Exonerated by: Pardonbased on innocence.Years lost: 13Verneal JimersonSentenced to death in 1985 for a doublemurder in Illinois. <strong>Snitch</strong>:A purported accomplicepromised release for testifying.Exonerated by: DNA and convictions ofthree actual culprits.Years lost: 11Richard Neal JonesSentenced to death in 1983 for a murder inOklahoma. <strong>Snitch</strong>: One of the actualkillers. Exonerated by: Confession of one ofthe snitch’s confederates.Years lost: 4Curtis KylesSentenced to death in 1984 for a murder inNew Orleans. <strong>Snitch</strong>:<strong>The</strong> actual killer.Exonerated by: Evidence that the snitch lied.Years lost: 14Fredrico M. MaciasSentenced to death in 1984 for a doublemurder in Texas. <strong>Snitch</strong>:A purportedaccomplice who testified pursuant to a pleaagreement. Exonerated by:A solid alibi.Years lost: 10Steve ManningSentenced to death in 1993 for a murder andarmed robbery in Illinois. <strong>Snitch</strong>:A jailhouseinformant. Exonerated by: Dismissal ofcharges.Years lost: 10Walter McMillianSentenced to death in 1988 for a murder inAlabama. <strong>Snitch</strong>:<strong>The</strong> actual killer.Exonerated by: Exculpatory documents withheldat the trial.Years lost: 10Virdeen Willis Jr., an off-duty assistant warden at the Illinois penitentiary in Pontiac,was shot to death in the parking lot of a Chicago tavern in 1985. Steven Smith, 36,who had been in the bar, as had Willis, was charged with the crime several dayslater after he was identified by Debra Caraway, who claimed to have witnessed themurder. Her testimony persuaded a jury to send Smith to death row.<strong>The</strong> jury, however, was told neither that Caraway’s boyfriend, Pervis (Pepper) Bell,was in custody as the primary suspect when she accused Smith nor that she was highon cocaine when the crime occurred. Caraway’s testimony was all the more dubiousbecause she claimed that only Willis and Smith were in the parking lot, but, in fact,Willis was accompanied by two friends.In 1999, the Illinois Supreme Court reversed the conviction outright, holdingthat Caraway’s testimony was less reliable than the testimony of the men who werewith Willis when he was shot, neither of whom identified Smith.<strong>The</strong>re was nophysical evidence, or evidence of any kind other than Caraway’s testimony, linkingSmith to the crime.Juan Roberto MelendezSentenced to death in 1984 for a murderand armed robbery in Florida. <strong>Snitch</strong>:A convicted felon who testified in anticipationof leniency. Exonerated by:Withheld policereports.Years lost: 188

Gary GaugerGary Gauger was sentenced to death in 1994 for themurder of his parents, Morris and Ruth Gauger,on their farm in northern Illinois the previous year.<strong>The</strong> conviction stemmed primarily from an allegedconfession that the authorities claimed Gaugermade during interrogation. However, the prosecutionalso relied in part on a jailhouse snitch — RaymondWagner, a twice-convicted felon, who testified thatGauger repeatedly admitted the crime.<strong>The</strong> conviction was reversed on appeal in 1996 onthe ground that the purported confession shouldhave been suppressed at the trial because it was thefruit of an arrest made without probable cause.With no remaining evidence, other than Wagner’sdubious testimony, prosecutors dropped the chargesand set Gauger free, although they continuedto insist publicly that he had committed the crime.two members of a motorcycle gang on multiplecounts of racketeering, including the murder of theGaugers. One of the Outlaws, James Schneider,pleaded guilty in 1998, and the other, Randall E.Miller, was convicted in June of 2000. At Miller’strial, federal prosecutors played tape recordings inwhich Miller was heard boasting that the authoritieswould never link him and Schneider to theGauger murders because they had worn hairnetsand gloves to avoid leaving physical evidence.In 2002, Gauger received a gubernatorial pardonbased on innocence.A year later, Gauger’s innocence became apparentwhen a federal grand jury in Milwaukee indicted9

Steven ManningNational RosterAdolph H. MunsonSentenced to death in 1984 for a murder inOklahoma. <strong>Snitch</strong>:A prisoner withwhom Munson was incarcerated. Exoneratedby: Discovery of previously withheld evidenceestablishing that the killer was white, Munsonbeing black.Years lost: 11Larry OsborneSentenced to death in 1999 for murdering anelderly Kentucky couple. <strong>Snitch</strong>:A purportedaccomplice who died in an accident beforethe trial but whose grand jury testimony waserroneously admitted against Osborne.Exonerated by:Acquittal at retrial.Years lost: 4Aaron PattersonSentenced to death in 1989 for the murderof an elderly couple in Chicago. <strong>Snitch</strong>:A cousin of an alternative suspect in the casewho claimed Patterson admitted the crime.Exonerated by: Gubernatorial pardon.Years lost: 14Alfred RiveraSentenced to death in 1997 for a doublemurder in North Carolina. <strong>Snitch</strong>es:Threeinformants who received leniency onpending charges. Exonerated by:Acquittal atretrial based on a credible alibi.Year’s lost: 3James RobisonSentenced to death in 1977 for the conspiracymurder of a Phoenix newspaperman. <strong>Snitch</strong>:A criminal admittedly involved in the murderwho received leniency in exchange fortestifying. Exonerated by:Acquittal at retrial.Years lost: 16Jeremy SheetsSentenced to death in 1997 for a murderin Nebraska. <strong>Snitch</strong>:<strong>The</strong> actual killer, whomade a tape-recorded statement accusingSheets in exchange for promise of leniency.Exonerated by:<strong>The</strong> snitch’s recantation.Years lost: 4Steven Manning, a former Chicago police officer and FBI informant, was sentencedto death in 1993 for the murder of his former business partner, a suburban trucker.<strong>The</strong> conviction rested primarily on the testimony of a jailhouse informant,ThomasDye, a cocaine dealer with a record of ten felony convictions dating to 1978. Dyetestified that Manning admitted the murder to him. In exchange for his testimony, a14-year prison sentence Dye was serving on theft and firearms charges was cut to sixyears already served and he was released into the federal witness protection program.<strong>The</strong> Illinois Supreme Court awarded Manning a new trial in 1997 based on trialerrors and the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office dropped the charges in2000. Manning was then sent to Missouri, where he had been sentenced to prisonon unrelated charges. In 2004, he was exonerated of those charges as well.Manning claimed he had been framed in both cases by his former FBI handlers outof spite because he stopped cooperating with them.Charles SmithSentenced to death in 1983 for a murderin Indiana. <strong>Snitch</strong>:A purported accomplicegranted immunity from prosecution.Exonerated by:An alibi that the judge didnot allow Smith to present because his lawyerfailed to file a pretrial notice.Years lost: 810

Rolando CruzRolando Cruz and Alejandro Hernandez were twiceconvicted of the 1983 abduction, rape, and murderof 10-year-old Jeanine Nicarico in DuPage County.<strong>The</strong>y initially were tried together and sentenced todeath in 1985. After their convictions were reversedin 1988 on the ground that their trials shouldhave been severed, separate re-trials ended in anothersentence of death for Cruz and 80 years forHernandez.In all, six snitches testified at the trials. Four —Stephen Ford, Steven Pecoraro, Dan Fowler, andRobert Turner — claimed Cruz had admitted thecrime, and the others — Jackie Estremera andArmindo Marquez Jr. — claimed Hernandez had.After Ford came forward, prosecutors dismissedburglary charges against him. Pecoraro, Fowler, andTurner denied being offered or receiving anythingin return for testifying, but one of the prosecutorslater testified on Turner’s behalf at a re-sentencinghearing. Estremera was facing contempt sanctions atthe time he implicated Hernandez, and Marquezreceived leniency on pending burglary charges.Shortly after the first trial, Brian Dugan, a repeatsex offender, confessed that he alone committed thecrime.Although his confession was detailed andcompelling, prosecutors insisted he and Cruz andHernandez had committed the crime together.<strong>The</strong>yclung to that theory even after DNA linkedDugan but not Cruz and Hernandez to the rapeafter the second trial.In 1995, Cruz and Hernandez were exoneratedwhen it became obvious that sheriff’s deputies hadfabricated an inculpatory statement that theyattributed to Cruz at both trials. Cruz andHernandez received pardons based on innocencein 2002.11

Madison HobleyNational RosterSteven SmithSentenced to death in 1985 for the murder ofan off-duty prison guard in Chicago. <strong>Snitch</strong>:A cocaine-addled girlfriend of an alternativesuspect in the case. Exonerated by:Outright reversal by the Illinois SupremeCourt.Years lost: 14Christopher SpicerSentence to death in 1973 for a murder inNorth Carolina. <strong>Snitch</strong>:A jailhouseinformant. Exonerated by: Discovery thatSpicer and the informant did not share a cell.Years lost: 2Gordon (Randy) SteidlSentenced to death in 1987 for the murderof an Illinois couple. <strong>Snitch</strong>:A jailhouseinformant and a purported accomplice allowedto plead to lesser charges. Exonerated by:Evidence disproving the purported accomplice’stestimony.Years lost: 17John ThompsonSentenced to death in 1985 for a murderin New Orleans. <strong>Snitch</strong>es:A man originallycharged with the crime but allowed toplead to lesser charges after implicatingThompson, and a second man who claimedthat Thompson had admitted the crime andapplied for a $15,000 reward. Exoneratedby: Exculpatory physical evidence concealed bythe prosecution at trial.Years lost: 9Dennis WilliamsTwice sentenced to death, in 1978 and 1986,for a double murder in Illinois. <strong>Snitch</strong>es:Atthe first trial, a jailhouse snitch; at the second,a purported accomplice who testified inexchange for release. Exonerated by: DNA,recantation of the purported accomplice, andconvictions of the actual killers.Years lost: 16Ronald WilliamsonSentenced to death in 1988 for a rape andmurder in Oklahoma. <strong>Snitch</strong>es:<strong>The</strong>actual killer and two jailhouse informants.Exonerated by: DNA.Years lost: 16At least four men were sentenced to death for murders they did not commit duringthe 1980s based primarily on confessions extracted by a group of rogue Chicagopolice officers later found by their own department to have engaged in “methodical”and “systematic” torture of suspects.<strong>The</strong> convictions of two of the innocent men —Madison Hobley and Aaron Patterson — also rested in part on snitch testimony.Hobley was accused of setting a fire that claimed seven lives, including those of hiswife and infant son, in an apartment building on the south side of Chicago in 1987.<strong>The</strong> snitch was Andre Council, a suspect in another arson fire in the same neighborhood.In exchange for police agreeing to drop the investigation in which he wasa target, Council testified that he saw Hobley purchase gasoline at a filling station anda little later, after hearing fire engines, saw him standing outside the burning building.Hobley was convicted and sentenced to death.Patterson was accused of a double murder on the south side in 1986. A few days afterthe victims’ bodies were discovered, Marva Hall, a 16-year-old cousin of a suspect inthe case, told police that Patterson had admitted the crime to her. She later providedan affidavit saying she had lied to protect her cousin, but not before her testimonyhelped send Patterson to death row.In 2003, both men received pardons based on actual innocence from IllinoisGovernor George H. Ryan and were released from prison.Nicholas YarrisSentenced to death in 1982 for a kidnaping,rape, and murder in Pennsylvania. <strong>Snitch</strong>:A jailhouse informant. Exonerated by: DNA.Years lost: 2212

A Quintessential <strong>Snitch</strong>Darryl MooreNot much good has ever been said of DarrylMoore. He is a hit man, drug pusher, robber, rapist,junkie, parole violator, and, perhaps foremost,perjurer.“For money,” an assistant Cook Countystate’s attorney once told a jury,“Mr. Moore eitherbeats people, maims them, or, if need be, he willkill them for the right price.”Rather than protecting society from Moore,however, prosecutors entered into a pact with him.He would testify for the state concerning an allegedcontract murder. In return, he would be paid cash.Pending drug and weapons charges against himwould be dropped. He would be immunized fromprosecution for a contract murder in which headmittedly participated. And he would be turnedloose on the streets of Chicago.<strong>The</strong> deal seemed ill-advised even to Moore’s mother,who took the stand as a defense witness after herson testified for the prosecution in a murder case.“Do you know Darryl’s reputation … for beingtruthful?” asked a defense lawyer.“Yes,” Ethel Mooreanswered.“Is that reputation good, or is it bad?”“Bad.”“Would you believe Darryl Moore underoath?”“No, I wouldn’t.”If Moore had been convicted of drug andunlawful-use-of-a-weapon charges pending whenprosecutors decided to let him go, he wouldhave faced a long prison term. Because of his priorconvictions for rape and armed robbery, hecould have been sentenced as an habitual criminal.In exchange for the testimony of this man whoseown mother would not believe him, however,prosecutors set him free and spent some $66,000 inpublic funds to, among other things, house himand a woman friend in a Holidome hotel.ironically, were soon rendered moot by naturalcauses — at the time of his trial, Ashley was dyingof cancer. Moore did testify for the state. Ashleywas convicted of murder and sentenced to spend thebrief remainder of his life in prison.Ashley’s co-defendants, James Allen and HenryGriffin, also were found guilty. Allen was sentencedto life, Griffin to death (later commuted to life).As their convictions were appealed, Moore recanted,claiming that the state’s attorney’s office paid himto lie as part of a scheme to frame Ashley. In truth,said Moore, he knew nothing of the crime of whichAshley, Griffin, and Allen had been convicted.Before he recanted, however, with the freedomprosecutors bestowed upon him, Moore descendedon Chicago’s Uptown neighborhood, his home awayfrom jail and the Holidome.<strong>The</strong>re, on a Februaryevening in 1987, he came upon an 11-year-old girlwho was on her way to the grocery store. Hedragged her into an alley, pushed her down, andraped her. For this, Moore was charged, convicted,and sentenced to 60 years.With day-for-day goodtime, he is eligible for release in 2017.Griffin and Allen, who lost their appeals, are servinglife without parole.<strong>The</strong> purpose of the deal was to convict a drugkingpin, Charles Ashley, who allegedly paid twoco-defendants to murder a suspected informant.<strong>The</strong>prosecutors’ efforts to put Ashley out of business,13

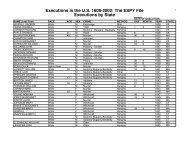

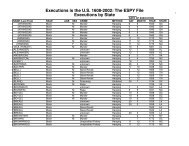

Major Causes of Wrongful Convictionsin U.S. Capital Cases Since 1973CASES ANALYZED: 111*Key:A = <strong>Snitch</strong>: 50 (45%) B = Erroneous identification: 28 (25.2%)C = False confession: 16 (14.4%) D = False or misleading science: 11 (9.9%)name A B C D name A B C D name A B C D name A B C DAdams, Randall Dale ✓ ✓Gauger, Gary ✓ ✓Keaton, David ✓ ✓Poole, Samuel A.Amrine, Joseph✓Gell, Alan✓Keine, Ronald✓Porter,Anthony ✓ ✓Banks, JerryGiddens, Charles✓Kimbell,Thomas H.Prion, Lemuel✓Beeman, Gary ✓ ✓Gladish,Thomas✓Krone, Ray✓Quick,WesleyBloodsworth, Kirk✓Golden, AndrewKyles, Curtis ✓ ✓Ramos, JuanBowen, Henry✓Graham, ErnestLawson, Carl✓Rivera, Alfred ✓ ✓Brandley, ClarenceGraham, Michael Ray✓Lee,Wilbert✓Robison, James✓Bright, Dan L.✓Grannis, David W.Linder, MichaelRoss, Johnny✓Brown, Anthony✓Green, Joseph N.✓Macias, Fredrico M.✓Scott, Bradley✓Brown, Shabaka✓Greer, Richard✓Manning, Steve✓Sheets, Jeremy✓Brown,Willie A.✓Guerra, Ricardo A.✓Manning,Warren D.Skelton, John C.Burrell, Albert R.✓Harris, BenjaminMartinez, JoaquinSmith, Charles✓Burrows, Joseph ✓ ✓Hayes, Robert✓Mathers, Jimmy LeeSmith, Clarence✓Butler, Sabrina✓Hennis,Timothy✓Matthews, Ryan✓Smith, Jay C.Charles, Earl P. ✓ ✓Hernandez, Alejandro ✓ ✓McManus,VernonSmith, Steven✓Clemmons, EricHicks, Larry✓McMillian,Walter✓Spicer, Christopher✓Cobb, Perry ✓ ✓Hobley, Madison ✓ ✓Melendez, Juan R.✓Steidl Gordon✓Cochran, JamesHolton, RudolphMiller, Robert Lee, Jr.Thompson, John✓Cousin, Shareef✓Howard, Stanley✓Morris, Oscar LeeTibbs, Delbert✓Cox, RobertHoward,TimothyMunson, Adolph H.✓Tillis, Darby ✓ ✓Creamer, James✓James, Gary LamarNelson, GaryTreadaway, Jonathan✓Cruz, Robert Charles✓Jarramillo, AnibalNieves,William✓Troy, Larry ✓ ✓Cruz, Rolando ✓ ✓ ✓Jimerson,Verneal ✓ ✓ ✓Orange, Leroy✓Washington, Earl✓Deeb, Muneer✓Johnson, LawyerOsborne, Larry✓Wilhoit, Greg✓Dexter, Clarence R.Johnston, Dale✓Padgett, Randall✓Williams, Dennis ✓ ✓ ✓Drinkard, GaryJones, Richard Neal✓Pitts, Freddie✓Williamson, Ronald ✓ ✓ ✓Fain, Charles I. ✓ ✓Jones, Ronald✓Patterson, Aaron ✓ ✓Yarris, Nicholas✓Ferber, Neil ✓ ✓Jones,Troy LeePeek, Anthony Ray✓* This is a Center on Wrongful Convictions analysis of cases identified as exonerations by the Death Penalty Information Center.<strong>The</strong> criteria are that the defendantwas convicted after 1973 and subsequently restored to a state of legal innocence. Most commonly, the conviction was overturned on appeal and the defendantwas acquitted upon re-trial, the charges were dropped by the prosecution, or the defendant received a gubernatorial pardon based on innocence.When no cause ofthe wrongful conviction is checked above, none of the factors analyzed was present.14

Reining in the <strong>Snitch</strong> <strong>System</strong>Given the unreliability and tragic consequences ofincentivised testimony, some legal authorities — andnot just criminal defense lawyers — have calledfor banishing snitches outright from the courtroom.“If justice is perverted when a criminal defendantseeks to buy testimony from a witness, it is no lessperverted when the government does so,” observedJudge Paul J. Kelly Jr., of the U.S. Court of Appealsfor the Tenth Circuit.“<strong>The</strong> judicial process is taintedand justice is cheapened when factual testimony ispurchased, whether with leniency or money.”*Be that as it may, the reality is that neither legislaturesnor courts are about to ban snitch testimonyin the prevailing tough-on-crime political climate.<strong>The</strong>re are, however, less drastic safeguards againstwrongful convictions based on snitch fabricationsthat may be more politically palatable.Among the ideas are requiring that:• <strong>Snitch</strong>es be wired to electronically recordincriminating statements made by suspects, at leastwhen the relevant conversations occur in jailsor prisons. (<strong>The</strong>re is precedent for wiring snitches.It was done in the Steven Manning case in Illinois,discussed on page 10. Extensive conversationsbetween Manning and the informant,TommyDye, were surreptitiously recorded in jail. Althoughthe conversations were not incriminating,the fact that they were recorded demonstrates thefeasibility of the idea.)• Law enforcement authorities electronically recordtheir discussions with potential snitches andprovide copies of the recordings to the defendant.(This would not be a major imposition on lawenforcement, since most such discussions occur incustodial settings. It merely would be an extensionof the increasingly prevalent practice of recordingcustodial interrogations of suspects.)• Prosecutors disclose to defendants whethersnitches — be they jailhouse informants, purportedaccomplices, or eyewitnesses — have receivedor been promised leniency, immunity fromprosecution, cash, or anything else of value. (<strong>The</strong>impact of this reform might be limited becausethe snitch system sometimes operates on implicitpromises. Even absent a formal understanding,the reward inevitably comes — because failing todeliver in one case would chill prospectivefuture snitches.)No state has adopted either of the first two ideas,but the Illinois General Assembly in November2003 adopted the third, as part of a sweepingpackage of death penalty reform legislation. Also inIllinois, in any capital case in which the prosecutionproffers jailhouse snitch testimony, the reformpackage requires the judge to conduct a pretrialhearing “to determine whether the testimony of theinformant is reliable.” If not, the court must denyadmission of the testimony into evidence.At this writing, it is too early to gauge theeffectiveness of the Illinois measure, but it appearsto have rendered snitches less ubiquitous thanthey were in the recent past. In the first 11 monthsthat the reform was in effect, in fact, prosecutorshave not proffered snitch testimony in any potentialcapital case.* United States v. Singleton, 144 F.3d 1343(10th Cir., 1998).Vacated by rehearing en banc.15

Northwestern University School of LawCenter on Wrongful ConvictionsDedicated to identifying and rectifying wrongful convictions and other serious miscarriages of justiceLawrence C. MarshallLegal DirectorRob WardenExecutive DirectorThomas F. GeraghtyDirector, Bluhm Legal ClinicDavid E.Van ZandtDean, Northwestern UniversitySchool of LawSTAFF ATTORNEYSKaren L. DanielSteven A. DrizinJane E. RaleyJeffrey UrdangenEXECUTIVE STAFFEdwin ColfaxZakia HollyJennifer LinzerKaren RanosA. Sage SmithCOOPERATINGATTORNEYSDanielle CarterJohn H. GalloStephanie HortenJonathan D. KingBetsy Lehman LevisayJoe MatthewsMichael B. MetnickDavid MorrisStuart ReynoldsJudith RoyalRonald S. SaferJennifer L. SchillingJennifer SmileyADVISORY BOARDThomas P. Sullivan*ChairmanJane Beber AbramsonKimball Anderson*Jamie AlterJeanne BishopThomas M. BreenStephen B. BrightStuart J. Chanen*Donald ConneryPhilip H. CorboyPhoebe C. EllsworthMichael FarrellMarshall B. FrontThomas H. GeogheganLeonard C. GoodmanSamuel R. GrossRobert A. HelmanWalter Jones*Michael KurzmanGeorge N. LeightonJeffrey P. Lennard*John G. Levi*Ellen LiebmanTerri L. Mascherin*Donald J. MizerkJoseph T. MonahanGareth Morris*Peter NeufeldR. Eugene PinchamDom J. RizziGeorge H. RyanRonald S. Safer*Barry C. ScheckJohn R. Schmidt*Seymour F. SimonPhillip A.Turner*Dan K.Webb*Wayne W.Whalen*Sheldon T. Zenner* Executive CommitteeBENEFACTORSJane and Floyd AbramsonAce FoundationArca FoundationRichard ArmbrustJohn W. BairdThomas M. BreenSteven CohenPatricia D. CornwellArie & Ida Crown Memorial FoundationJames and Judith K. Dimon FoundationGary M. Elden and Phyllis MandlerFifteen Two Four, LLC (James Newsome)Jason FlomLeonard C. GoodmanRobert GoodmanJenner & BlockJane Kaczmarek and Bradley WhitfordKirkland & EllisKovler Family FoundationLerer Family Charitable FundPeter B. LewisMichael Lynton and Jamie AlterMayer Brown Rowe & MawKenneth F. and Harle G. Montgomery FoundationNew Prospect FoundationOpen Society InstitutePittman Family FoundationIvy Lewis Powell and Marc PowellJay Pritzker FoundationJ.B. and M.K. Pritzker Family FoundationWillie Raines TrustJudith RoyalKeith RudmanSkadden Arps Slate Meagher & FlomSynapses FoundationSonnenschein Nath & RosenthalScott TurowJeffrey UrdangenMike WallaceDonald A.WashburnWinston & Strawn<strong>The</strong> Center on Wrongful Convictions is part of Northwestern University, which is exempt from federal taxationunder Sections 501(c)(3) and 509(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code.BLUHM LEGAL CLINICCenter on Wrongful ConvictionsBluhm Legal ClinicNorthwestern University School of Law357 East Chicago AvenueChicago, Illinois 60611www.law.northwestern.edu/wrongfulconvictions312 503-2391