A Hospital Without Borders - Anna Dubrovsky

A Hospital Without Borders - Anna Dubrovsky

A Hospital Without Borders - Anna Dubrovsky

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

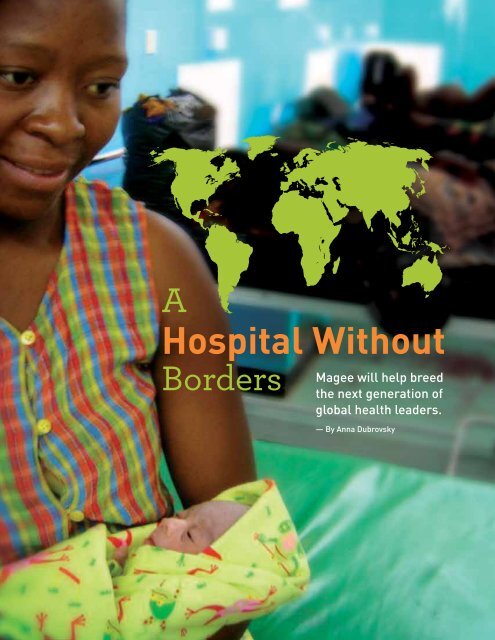

A<strong>Hospital</strong> <strong>Without</strong><strong>Borders</strong>Magee will help breedthe next generation ofglobal health leaders.— By <strong>Anna</strong> <strong>Dubrovsky</strong>

MAGEE: MAGEE-WOMENS RESEARCH INSTITUTE & FOUNDATION PAGE 7University of Pittsburghmedical students learn anawful lot, everything fromanatomy to surgery.But the seven who ventured to Haiti in June werewoefully unprepared for one of their tasks: going tomarket for chickens. “It was quite funny,” says DanielLattanzi, MD, co-director of the Ob-gyn Global HealthProgram at Magee-Womens <strong>Hospital</strong> of UPMC, wholed the trip. “We kind of stood out.”For many of the students, Haiti offered their firstglimpse of health care in the developing world.From malnourished infants to a hospital filled tooverflowing with cholera patients, what they sawdispelled any romanticnotions of the globalhealth field. While thetrip to market may haveprovided comic relief, itunderscored thechallenges of doctoringin impoverished areas.They left the chickensin the care of localfamilies, explaining thatthe eggs would providemuch-needed proteinand maybe even someincome. But they can’tcount on the familiesto stick to the plan.“Under the circumstancesthey live in, it’s going tobe very difficult,” says Dr.— W. Allen Hogge, MDLattanzi, who has beenworking in Haiti for 15years. “We have to convince them that the eggs aremore important than the chickens, because they’regoing to want to eat the chickens.”Despite the challenges, many Pitt medical schoolstudents and Magee residents are eager to participatein the global health movement, which seeks to makehealth care more accessible in countries where deathsfrom preventable and treatable diseases are all toocommon. Though still in its infancy, the Global HealthProgram has an ambitious agenda: to provide themwith firsthand experience, to raise awareness ofdisparities in women’s health care, and to markedlyimprove the wellbeing of women and children in thecommunities it touches. “We don’t want our residentsand students to be simply tourists in a foreigncountry,” says W. Allen Hogge, MD, chairman of theDepartment of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciencesat Magee. “Our goal is to match their interests with the needsof a particular community and to make a difference in the healthand well-being of that community. And we want our efforts tobe sustained, with long-term benefits to our partners.”One of the strengths of the program is its leadership. Dr. Lattanziand co-director Miriam Cremer, MD, have a combined 29 years ofexperience in global health work. And they’re not slowing down.Dr. Lattanzi, a UPMC ob-gyn who practices in Mt. Lebanon, travelsto Haiti about three times a year.“We don’t want our residents and studentsto be simply tourists in a foreign country,”Dr. Cremer hasbeen to El Salvador,Guatemala, theDominican Republic,and Nicaragua sinceshe was recruited toMagee from NewYork’s Mount Sinai<strong>Hospital</strong> inDecember.Participants inthe Global HealthProgram will havethe uniqueopportunity to workalongside them.During this summer’sHaiti trip, medicalstudents participatedin the opening of ahealth clinic in a remote mountain village about 60 miles north of thecapital city of Port-au-Prince. Dr. Lattanzi and several other doctorsfrom western Pennsylvania treated 400 people in the first two days,including many small children. Hundreds more turned out to marvelat the new clinic — the second Dr. Lattanzi has opened in Haiti. “Thepeople were very excited to have a health center,” he says. “It’s the onlycement building other than the school in the whole area. Having aclinic not only gives them access to health care but also gives thema great deal of pride in their community.”The doctors and students also spent a day tending to patients ina village that has no clinic. They made the trip there in the back ofa truck but had to hike out after a downpour washed out the road.The two-and-a-half-hour trek exhausted Dr. Lattanzi, “but the medicalstudents thought it was great to hike in the pouring rain,” he says.“Their mothers would probably kill me.”

MAGEE: PAGE 8Battling Diseases – and Myths – in HaitiDr. Lattanzi made his first trip to the Caribbeancountry in 1997 after hearing the pastor of theLaCroix Haiti New Testament Mission speakat a Pittsburgh church. To prepare, he met withPittsburgh-based administrators of Hôpital AlbertSchweitzer Haiti, built in the 1950s by philanthropistand physician William Larimer Mellon and his wife,Gwen. They told him what to expect, but nothingcould prepare Dr. Lattanzi and the nurse whoaccompanied him for the realities of life in theWestern Hemisphere’s poorest country.“It was very dramatic,” he recalls. “We traveled fromvillage to village, setting up makeshift clinics, andwe saw a lot of tuberculosis, a lot of malaria, a lotof intestinal parasites. Almost all the children hadintestinal worms, and they were big ones. We sawa lot of malnutrition. About 25 percent of the childrendied before they reached age 5. They didn’t even namethe children for the first year of life becauseit was such a bad situation.”After several more trips, Dr. Lattanzi decided to opena permanent clinic on the grounds of the LaCroixmission. Now staffed by one doctor, one dentist, andseveral nurses, theclinic serves about100 people a day, fivedays a week. In 2007,Dr. Lattanzi addeda six-bed birthingcenter. “We’re reallyworking hard todecrease maternaland newbornmortality,” he says.“One of the biggestproblems we haveis that most of thewomen still deliverat home with a birthattendant, who isa very importantperson in thecommunity but hasvery little training. Weget all their problems.”In an average month,the center’s trainedmidwives deliver onlyeight to 10 women but treat as many as 30 or 40whose home births went awry.Dr. Lattanzi has also made a big push to catch malaria andsyphilis in pregnant women. Haitian women are partially immuneto malaria, but the parasitic disease can cause intrauterine growthretardation. At certain times of year, as many as 30 percent ofpregnant women screened at the LaCroix clinic have malaria,which can be treated with antiparasitic drugs. Syphilis is evenmore prevalent – and far deadlier. “In 30 years of practice in theU.S., I’ve seen two cases of syphilis,” Dr. Lattanzi says. “But inHaiti, 8 percent of our pregnant women have it. We thinkcongenital syphilis is the main cause of newborn deaths.”Treating syphilis is easy, but convincing women “that these babiesare dying from something we can prevent is very difficult. Imaginea culture that has developed in the absence of health care. They’realways going to try to explain what happens. So they believe that awerewolf bite causes babies to die. We’re trying to do something thattheir culture is not familiar with, and that’s our biggest challenge.”Taking on a Top Killer in El SalvadorDr. Cremer will never forget the first time she saw someone die froma preventable disease. The year was 1997, and she was a Universityof Wisconsin medical student spending a semester in rural El Salvador.“While I was there, a woman in her early 20s died of cervical cancer.She had metastases allover her body, she wasin horrible pain, andshe bled to death inher home. It was animpressionableexperience for me.”Deborah Landis Lewis, MD, the first GlobalHealth Program fellow, holds a newborn inthe southern African country of Malawi.The center has begun distributing birthing kitsto pregnant women in the hopes of reducingcomplications during home deliveries. They includea cord clamp, sterile gloves, and a plastic sheet.In the U.S. and otherdeveloped countries,deaths from cervicalcancer are virtuallyunheard of, thanks toroutine screening andcutting-edge treatments.But worldwide,more than 500,000women are diagnosedwith cervical cancereach year, and 275,000die from it. In ElSalvador, it’s thenumber one cancerkiller of women.The picturesquelittle town whereDr. Cremer was based didn’t have the equipment to screen for cervicalcancer, let alone treat it. “So I had a friend who came to visit bringa duffel bag full of slides, and we did 87 pap smears,” she recalls.“We brought them back to the University of Wisconsin, and the labread them for free.”www.mwrif.org

MAGEE: MAGEE-WOMENS RESEARCH INSTITUTE & FOUNDATION PAGE 9After medical school, she completed a masters inpublic health at Johns Hopkins University and thenan ob-gyn residency at New York Downtown <strong>Hospital</strong>,spending most of her vacation time leading medicaldelegations to El Salvador. During a fellowship infamily planning in Los Angeles, she founded BasicHealth International, a nonprofit devoted to eradicatingcervical cancer. Since 2006, the group has trainedmore than 100 Salvadoran physicians in pap testingand visual inspection, two basic methods for identifyingcervical disease, as well as cryotherapy, whichdestroys potentially cancerous tissue. They in turnhave screened about 9,000 women for cervical cancer.In the past year, Basic Health International has beeninvited to train physicians in Haiti, Guatemala,Nicaragua, and the Dominican Republic.Among Dr. Cremer’s latest undertakings is a researchstudy to determine if carbon dioxide gas can be usedin place of nitrous oxide in cryotherapy. The formeris significantly cheaper than the latter and is madeat any soda bottling plant. “If you could have locallyavailable, inexpensive gas, it could really expand howmany women you could see and treat, especially invery remote areas,” she says. “No one has everrigorously studied if that could work.” She has enoughfunding to start the project and has applied for grantsto finish it.She has no regrets about moving her family of fourfrom Brooklyn, New York, to Pittsburgh. “At Magee, Ican focus more on global health work, which is reallymy passion,” she says. “People here are very specialized,which was appealing to me, and they really seemto value global health.”Seizing an Opportunity at MageePhysicians with as much experience in third-world medicineas Drs. Cremer and Lattanzi are few and far between, which makesPitt and Magee magnets for the next generation of globetrotting docs.Dr. Cremer has had promising discussions with medical schooladministrators about adding global health work as a clinical rotation.For Magee residents interested in global health, she and Dr. Lattanzihave begun offering a monthly lecture series on topics such asmaternal mortality, fistula, and female circumcision.One of the main components of the new Global Health Programis a two-year fellowship. Deborah Landis Lewis, MD, who completedan ob-gyn residency at the hospital this summer, is the first recipient.Her passion for global health stretches back to childhood, when herparents were working at a mission hospital in the Middle East. As acollege student, she spent a semester in Yemen, screening ruralschoolchildren for a parasitic disease and distributing bed nets tohelp prevent malaria. Later, she spent a year in Syria’s capital, whereshe cared for developmentally disabled adults. During a yearlongbreak from Pitt medical school, she volunteered at a large maternityhospital in the southern African country of Malawi, which has oneof the highest maternal mortality rates in the world. Shorter tripsback to Africa, as well as to Honduras and Guyana in Latin America,round out her global health résumé.Over the past year, Dr. Landis Lewis has surveyed directors of ob-gynresidencies around the U.S. about opportunities for residents toparticipate in global health work. “There’s a lot of interest,” she says.“About 70 to 80 percent of incoming residents in the field of obstetricsand gynecology report having had prior experiences in global healthor want to pursue it in some capacity. But most residency programsoffer very little in the way of global health education.”Magee has the opportunity to fill that gap — and it’s not aboutto pass it up.u u