what determines the scope of the firm over time? - CiteSeerX

what determines the scope of the firm over time? - CiteSeerX

what determines the scope of the firm over time? - CiteSeerX

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

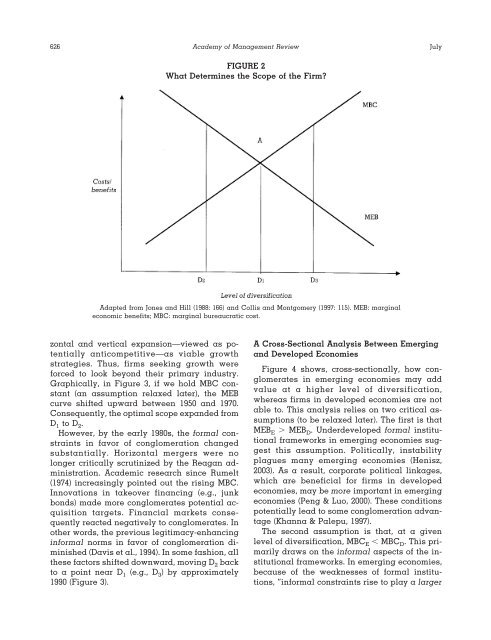

626 Academy <strong>of</strong> Management ReviewJulyFIGURE 2What Determines <strong>the</strong> Scope <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Firm?Adapted from Jones and Hill (1988: 166) and Collis and Montgomery (1997: 115). MEB: marginaleconomic benefits; MBC: marginal bureaucratic cost.zontal and vertical expansion—viewed as potentiallyanticompetitive—as viable growthstrategies. Thus, <strong>firm</strong>s seeking growth wereforced to look beyond <strong>the</strong>ir primary industry.Graphically, in Figure 3, if we hold MBC constant(an assumption relaxed later), <strong>the</strong> MEBcurve shifted upward between 1950 and 1970.Consequently, <strong>the</strong> optimal <strong>scope</strong> expanded fromD 1 to D 2 .However, by <strong>the</strong> early 1980s, <strong>the</strong> formal constraintsin favor <strong>of</strong> conglomeration changedsubstantially. Horizontal mergers were nolonger critically scrutinized by <strong>the</strong> Reagan administration.Academic research since Rumelt(1974) increasingly pointed out <strong>the</strong> rising MBC.Innovations in take<strong>over</strong> financing (e.g., junkbonds) made more conglomerates potential acquisitiontargets. Financial markets consequentlyreacted negatively to conglomerates. Ino<strong>the</strong>r words, <strong>the</strong> previous legitimacy-enhancinginformal norms in favor <strong>of</strong> conglomeration diminished(Davis et al., 1994). In some fashion, all<strong>the</strong>se factors shifted downward, moving D 2 backto a point near D 1 (e.g., D 3 ) by approximately1990 (Figure 3).A Cross-Sectional Analysis Between Emergingand Developed EconomiesFigure 4 shows, cross-sectionally, how conglomeratesin emerging economies may addvalue at a higher level <strong>of</strong> diversification,whereas <strong>firm</strong>s in developed economies are notable to. This analysis relies on two critical assumptions(to be relaxed later). The first is thatMEB E MEB D . Underdeveloped formal institutionalframeworks in emerging economies suggestthis assumption. Politically, instabilityplagues many emerging economies (Henisz,2003). As a result, corporate political linkages,which are beneficial for <strong>firm</strong>s in developedeconomies, may be more important in emergingeconomies (Peng & Luo, 2000). These conditionspotentially lead to some conglomeration advantage(Khanna & Palepu, 1997).The second assumption is that, at a givenlevel <strong>of</strong> diversification, MBC E MBC D . This primarilydraws on <strong>the</strong> informal aspects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> institutionalframeworks. In emerging economies,because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> weaknesses <strong>of</strong> formal institutions,“informal constraints rise to play a larger