Untitled - Beeldbibliotheek

Untitled - Beeldbibliotheek

Untitled - Beeldbibliotheek

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

nia

Ex LibrisC. K. OGDENTHE LIBRARYOFTHE UNIVERSITYOF CALIFORNIALOS ANGELES

CARAVAN DAYS

CARAVAN DAYS

AFTER LABOUR, REFRESHMENT

CARAVANDAYSBYBERTRAM SMITHAUTHOR OF "THE WHOLE ART OF CARAVANNING"ETC.Xont>onJAMES NISBET & CO. LIMITED22 BERNERS STREET, W.

First Published in 1914

CHAPTERCONTENTSFACEI. WHAT CARAVANNING Is . . . iII. THE CAMPAIGNING SIDE ... 9III. THE DOMESTIC SIDE . .18IV. THE HUMAN SIDE . .28V. THE CARAVAN " SIEGLINDA " .39VI. CREW AND EQUIPMENT ... 48VII. THE TROUBLES OF THE CARAVANNER 52VIII. To JOHN o' GROAT'S : I . .-57IX. To JOHN o' GROAT'S : II .-67X. To JOHN o' GROAT'S : III .76XI. OTHER JOURNEYS. . .86XII. How THE DAY is SPENT ... 92XIII. INCIDENTS AND PREDICAMENTS .97XIV. MINCED SCOTLAND . . . .noXV. SAM AND SIMON . .118XVI. SPECIMEN DAYS .... 127XVII. ALL SORTS OF CARAVANNERS . .140XVIII. MEMORABLE CAMPS . . ..151XIX. OUR MARCH TO THE WEST ..159XX. ROAD-GAMES AND SHORT CUTS . 168XXI. THE ENEMY 181

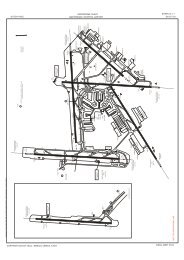

. TheVICHAPTERCONTENTSPACKXXII. MEALS AND SUPPLIES . . .188XXIII. ENCOUNTERS 195XXIV. CLOTHES 207XXV. COUNTIES AND CORNERS . ..214XXVI. CAMPERS' LUCK .... 220XXVII. RAIN AND LACK OF RAIN . .225XXVIII. MEMBERS OF THE UNDERWORLD .242XXIX. THE JOURNEY'S END . . .246XXX. CARAVAN DAYS .... 255ILLUSTRATIONSAFTER LABOUR, REFRESHMENT .A WEEK-END CAMPTHE ARRIVAL AT GAIRLOCHLEAVING LOCH MAREE. . Frc>Htisf>irctto face page 04162226PLAN OF CARAVAN " SIEGLINDA "MAP OF AUTHOR'S ROUTE40end

Shall we make a journey?There's a highway that 1 knowIn a country where the heather meets the sky,Where the hillsides are ablaze with the bracken s autumn glow.Shall we make a journey You and I?There's a littlewhispering burn there t running peaty from the hill,And the shepherd's rich in poultry and in kye:So you may have poached eggs and batter pudding if you will.Shall we make a journey You and I?You will make the beds, Dear, and I shall make the tea ;And we'll hang our wee bit washing out to dry ;And we'll black our boots for Sunday, though there's no one thereto see.Shall we make a journey You and I?And though we may turn homeward when this littlejoumty'* dene,There's a gey long road before MS, Dear,forbye.So take my hand, my Comrade, and we two shall be as one.Shall we make a journey You and I?

CARAVAN DAYSCHAPTER IWHAT CARAVANNING ISIT is sixteen years since myfirst caravan TRIUMVIRwas built and made her first journey in the countyof Cheshire. But although those April days inDelamere Forest made it clear to me that ina caravan I had found the very instrument andprovision that I needed, the tour was no verysudden departure for myself or the members ofmy crew. For I had made many journeys beforethat, that were free of railways, luggage andhotels.I had travelled often across country witha knapsack, though that was a most imperfectequipment which failed to deal with lodging forthe night. And the same is true of sportivego-as-you-please tours in which one had to makeone's way from point to point by every means ofprogression that occurred. But other expedi-

2 CARAVAN DAYStions were more complete.I used to travel witha tent and pony-cart. I used to go down riverswith a fleet of small punts and make an entrancinglittleencampment at night upon the bank, everyman sleeping in a bale of straw in his own boat,with a tent to cover the whole. And the factthat I have never yet actually driven acrossScotland in the sleigh that I built with that endin view must be put down solely to the climate,which has refused me opportunity.I am not sure that I ought not to go evenfurther back to find the origin of my present zealfor caravanning, in the love of a very small boyfor secret habitations of all sorts. For I was notcontent with caves and man-holes, with the darkcorner above the rafters in the hay-loft or thelittle clearingthat I made in the heart of thethicket. Perhaps I took the first decisive steptoward the attainment of the caravan SIEGLINDAon the well-remembered day when Iset to workto build a house in a tree. It was neatly fittedin,high among the swaying branches, where nogrown-up could hope to follow : there I spentgolden hours, shut in by sunlit greenery : andit was a heavy blow to me when at last the oldholm-oak was felled to make wayfor a newtennis lawn. Even in SIEGLINDA I doubt if I

WHAT CARAVANNING IS 3have ever quite recapturedall that was lost onthat most fateful day.By degrees my love for caravanning hascrowded out all other forms of enterprise andleft no room for them.enough of TRIUMVIR. IAt first I could not havewas in a Liverpool officeat that time, but I fled to her precipitatelywhenever it was possible, and I kept her alwaysin commission, well stocked with clothing andprovisions,so that I could reach her at theshortest notice. I made a number of curiouslittle zigzag journeys in those days,a bit at atime, leaving the van just where she happenedto be when I had to return and often not rejoiningher for many weeks.And at last I took the bullby the horns and camped her permanently by acountry railway station, where I settled downand lived in her and travelled back and forwardevery day.There has hardly been a summer since then inwhich I have not been out in a caravan, either inTRIUMVIR or in one of her successors. I havetoured in Wales, in the South of England andin Dumfries and Galloway. Sometimes I haveset up a stationary camp for a week or two, andonce, when SIEGLINDA had been added to thenumber, I realized my old ambition of laying

4 CARAVAN DAYSout a village of caravans and tents, which houseda considerable population for a fortnight in ameadow by a stream. But until the summer of1912 I had in reality been wasting my time.In those early days caravanning was partly anadventure, but chiefly a means of escape. WhatI wanted was to get away, to harness my horseand drive off, to enter a new world where all myold habits were broken and all my old occupationswere suspended. The important matterwas not so much what I found before me as whatI left behind. I cared very little where I wentor indeed whether I travelled or remained incamp.I wandered about at will, toying withalternatives at everycross-road. I had nodestination and no reason for travelling North orSouth, if anything invited me to East or West.I would have no letters or newspapers or maps.I stopped my watch and lost the time of day.All that I wanted was to look for adventure andfollow it when found, wherever itmight lead.Thus I went lounging about the country, knowingno spur but the spur of the moment. And I fedmy sense of freedom by overturning all establishedtimes and seasons, going to bed at 2 p.m. ortravelling all night and camping at the dawn,taking afternoon tea at midnight or breakfast-

WHAT CARAVANNING IS 5ing in the afternoon. And I got what I wanted,for those were good days, rich in glowingmemories.But caravanning means something quite differentto me now. SIEGLINDA has not spent herdays in loitering and dawdling in pleasant places.Igo out now to make a journey. I must havean aim before me. I must feel all the way thatI am eating up the miles, sweeping across themap, drawing nearer to my goal. I am a closestudent of contour books, gradients and surfaces.Every night I mark down the course of the day'smarch upon the map and add the day's performanceto the tally of the miles. I do not meanto say that I travel rigidly according to a settledroute, refusing to turn aside. But I am rulednone the less by the main line of advance. I mustget forward with the campaign.Now that I come to sum itupI find that I havechanged my opinion on almost every point ofpractice. The caravan SIEGLINDA represents thenew order of things. She was built for ourwedding journey some years ago. We travelledabout two hundred miles through Galloway, in aceaseless downpour.It was then that my Partnerand I learned to handle our craft, to work intoeach other's hands and to fit ourselves for the long

6 CARAVAN DAYScampaign of which I have to tell.It was not tillMay, 1912, that the way was clear before us forthe dash to John o' Groat's.Ihave never been able quite to lose my firstsense of wonder in regard to caravanning and theway of life that makes it possible both to traveland to stay at home. It is enough to look overSIEGLINDA, lying now dismantled in her shed,and to think of where she has been in these lasttwo summers, of her hundred camping-grounds,of the long trail of hill and dale that she has leftbehind. For the fulness and romance of caravanninglie in the fact that you do not simply goto see a place and come away. You bring yourhouse and home and live there as a settled citizen.All the way you have made your journeyinto theunknown among familiar things. Every nightyou have the same house with a new garden, newviews from the windows, a new aspect to the sun,new neighbours and surroundings. Yet vourrooms and all about you are the same. You areliterally at home in the strangest places.Caravanningis sometimes attacked for itscomplexity and elaboration, compared withcamping-out. But it is of a different orderto livealtogether. By all means if you are goingin a tent and I am myself a keen lover of canvas

WHAT CARAVANNING IS 7cut down your necessities and simplify to thelast degree. But the special charm of a caravanis in complexity and completeness, the whole funof itis to bring with you a dwelling fitted out inevery detail, even to shoe-horns and paperknives.For this little home and all that itcontains isopen to competethat merely carry goods or passengers.with other vehiclesThink ofwhere she has been and where she still may go.I may perform the offices of my daily life in anyplace where wheels will carry me. I may drawup and make my tea and drink it in the heart ofPiccadillyor the Strand. In the thick of thedensest traffic or far on the lonely moor, into anycorner of these islands where there runs a reasonableroad I may take myself-contained community,my private habitation,and no matterwhere I may be I shall be able to lay my handupon the frying-pan, to take down the book whichI left overnight in the rack above my head, to gointo the bedroom and strop my razor or changemy shoes.I am often asked what I do when I am caravanning,if I fish or play golf or collect beetles, orwhat. But I have never looked upon a caravanas supplementing other pursuits. It is far toobig and beautiful a thing in itself to act as an

8 CARAVAN DAYSauxiliary.these things.I can only reply that no, I do none ofI am too busy caravanning.It appeals to me on three different sides. Thereis the Campaigning side the journey, the countryand the road. There is the Domestic side theinternal economyand matters of the household.And there is the Human side, with its wide varietyof encounters. For there isnothing when thetour isover and one's gains are added up thatcounts for half as much as the people one has metupon the way.I propose to discuss the matter in my nextthree chapters from these three points of view.

CHAPTER IITHE CAMPAIGNING SIDETHERE are some who find fault with caravanningand I believe I was myself among them in daysof long ago because its scopeis restricted to theroad. With a knapsack and a portable tent orwith a donkey and a sleeping-bag you may leavethe beaten track for unfrequented by-paths andpenetrate into far recesses of the country. Witha caravan your choice is closely circumscribed.But to argue in this manner is onlyto showthat you have misunderstood. The attempt toavoid the road by travelling across country isentirely foreignto the caravanner's intention.For he belongs to the road. Even if it werepossible for him to scamper up hillsides or wendhis way down narrow glens the result would onlybe to leave a gap in his record at the point wherehe had deserted it. He is quite free on campingdays to wander where he will, and he is not soclosely bound to the caravan that he cannot breakaway for a mile or two to explore. But the9

ioCARAVAN DAYSplace of the caravan is always on the beatentrack : it demands no preferential treatment : itfalls into its stride amongother travellers ofevery degree upon the common highway.Of course it does. The road iseverything tothe caravanner. It isincomparablythe mostinteresting, the most thrilling thing in the landscapeit is the key to the : country, the onegreat common possession: it is history, andgeography and a running commentary on theaffairs of the district : it is the entrance and theexit and the stage.Ifthe caravanner cannot love the road for itsown sake and cannot feel itspower to lead himon he need not hope to make much of it. Forthe road is his element ;he can never think of itas so much solid, stationary macadam. It is tohim a living, fluid thing, rolling on into theunknown, ready to carry him round a hundredbends and corners, over a hundred hills, bybridges and cuttings and embankments, by levelstretches and sweeping undulations, changing itswhole nature repeatedly, daily confronting himwith new problems, daily bringing him newrewards, till at last it shall deliver him up at thejourney's end.All his fortunes are bound up with it, and the

THE CAMPAIGNING SIDEnmain questions with which he must concernhimself are those of gradients and surfaces.Forin a long campaign through difficult country itisimperative to look ahead, to know very clearlywhat you are in for, and the art of making outroutes is largely in studying how best to takethe bad hills the right way on and to avoid steeproads where the surface is soft or stony. Withregard to gradients it may be taken as a generalrule that anything above i in 20 is easilytravelled :by the time we get down to i in 15we must be prepared for heavy collar-work :i in 12 isdangerously steep. I have seldomclimbed anything much worse than that.At the very root of the matter, then,is thisstrong compuls-'on to follow the road, to get onwith the task in hand and the need of that newdaily panorama that will unfold itself, discovering,as you go forward, what isbeyond theforest, what is behind the hill, what new thingeach bend of the road has kept in store for you.In the old idle days I used to look for campinggrounds in remote and hidden places.I was veryfastidious about my nightly settlement, and itwas not till I had decided upon it that I gave athought to stabling. But that was literally toputthe cart before the horse.With an arduous

12 CARAVAN DAYSmarch to carry through the prime considerationis to find good quarters for the horses. There istime enough to look for a " seat " for the vanafter. Thus I am generally to be found in campnot far from a farm.Imay have lost somethingin my free choice of neighbourhood.I havegained much in freer intercourse with my neighbours.And I have learned the solid worth ofstackyards.There is one factor in estimating the conditionsof the march that I prefer to leave out altogether,and that is the weather.For I am always on theside of the climate and know very well thatalmost all weather isgood for caravanning, andthat indeed we need allsorts and conditions ofweather to complete the full tale of experienceand adventure on the road. There are fourmonths in the year in which I have never beenout in a caravan, and I stillhope to remedy thatomission. But there is one day above all othersthat invites me forth the First of May. Despiteitsmany broken promisesI still look to itas theday above all others to yoke up and drive away,and it was on the First of May that we set outfor John o' Groat's. There is no good day forcoming back. All that can be said is that somedays are better than others. If you can keep out

THE CAMPAIGNING SIDE 13till the weather breaks finally in the autumn andyou drive home in wind and rain you may findit the easier to settle down. That was why Iarranged the journey of last summer so that itended in October. For I had been profoundlydiscontented on my return from John o'Groat's.The grip that caravanning takes upon you asthe days run on and you become more and moreestablished in this way of life, is most easilyestimated by the keenness of your reluctance toreturn. My Partner and I always try to look onthe bright side of it. We make up and exchangecharming visions of all the compensations thatawait us." Think of hot tubs," my Partner will say...." And electric light," I chime in." Andregular posts and newspapers."..." And breakfast will be waiting when weget down in the morning."..." And we won't ever have to wash up."..." And we can use as much hot water aswe like without having to carry it."..." And we can play the pianola."..." We can play tennis for that matter."..." And after a while the sheen will comeoff my hands," I say.recognize me as a cook.""People will no longer

14 CARAVAN DAYSWe do not of course persuade one another, butwe do come to think after a time that there mustbe something to be gotout of it.All that comfortable line of argument is vanity.Perhaps some of these new sensations help for ashort time to stave off the inevitable conclusion.But it isn't any good. We are discontented andill at ease. For every morning when " yokingtime " comes round it isbrought home to us thatthere is no journey before us to-day, nor tomorrow,nor on any future day, that we must becontent with the same old view from our windows,that this is our only camping ground.And there are all manner of practical inconveniences.We have been living with all our dailynecessities within reach : now they are scatteredand dispersed. It seems that one must be alwaystramping along passages, moving from one roomto another, climbing stairs. The furniture isrid of it.clumsy and there is no way of gettingWe can no longer shut down tables and chairs.Pianos and writing-desks and vast sofas cumberthe ground. There are so many clocks to windup on Monday morning:so manyso much too much of everything.doors to lock atnightAnd we can no longer control and manipulateour surroundings:they are out of hand. We

THE CAMPAIGNING SIDE 15lose that comfortable sense of intimacy with allour minor chattels which had been worth so muchto us.For my part I have a maddening desireto burst into the kitchen and see what isgoing on,to lend a hand with the boots or help to beat thecarpets.But the root cause of our discontent is ofcourse that we are not moving on, that we havelost our daily panorama. We are suffering simplyfrom " horizon hunger."" The pauses are also music often the best ofthe music," my singingmaster used to tell me.And the same may be said of the camping dayson a long caravan tour.they are not the best of the music. IfI am not at all sure thatthey areindulged in too frequently they will lose theirsavour, for they are only worth the having whenthey come with a record of solid achievementbehind them. But after a full week on the roadit is delightful to rise half an hour later than usualwith no sense of urgency or dispatch,to sit onafter breakfast for a while and smoke a pipe,while one calculates how manyhave gathered up since last theyof the letters thatwere answeredit will be possible to neglect.Not that a camping day in SIEGLINDA hasabout itany flavour of idleness. The day's work

16 CARAVAN DAYSdoes indeed get slowly under way, but itrises intime to a fever of activity. It is Herbert's greatopportunity, with mop and broom and chamoisleather. (I shall introduce Herbert to you shortly :he is driver and handy man.)Inside and out thecaravan must be purged of all the stains of traveland the dust of the road. The first rite is thewashing of the floor, in preparation for which allmovables must be ejected in chaos and put backlater on in their due order.Then stoves, pots andpans, boots and shoes, curtain-rods, candlesticksand brasses must be made to shine. For my partIout the boxesam rotfnd at the back, cleaningand considering the state of the stores, re-arrangingand repacking. It is not until the evening whenHerbert has transferred his energies to the harnessthat peace descends upon the camp.Much depends upon the country and the roads,but generally a hundred miles a week isgoodgoing. Allowing for the many delays which arebound to occur, in watering the horses, shopping,enquiring about camping -ground, perhaps mendingharness or holding up a baker's cart, one doesnot reckon upon travelling more than three milesan hour : and six or seven hours on the roadevery day is rather more than enough.I do notgenerally travel more than five days a week,

THE CAMPAIGNING SIDE 17stopping for Sunday and one other day, with alonger pause about once a month for overhauling.At her very best SIEGLINDA travels at four milesan hour. That is on a sharply undulating roadwhere she is takingthe short rises at a trot.When I have to time her from point to point I amquite safe in estimating her paceat three and ahalf. And three and a half miles an hour isexactly the speed at which to travel if you wouldsee all that is to be seen, talk to everyone whohas anything to tellyou and absorb and digestevery stretch of the road, so as to make out bitby bit that perfect mental mapof the wholecountry which shall be yours when the journeyis complete.

CHAPTER IIITHE DOMESTIC SIDEIHAVE already spoken of the comfortable senseof intimacy with his minor chattels that belongsto the caravanner. It is the good workman'slove for the feel of the tools that have been wornby long use to his hand. It is very good,opening ofat thea tour, to be back again among thedear, familiar things, the small contrivances, thespecialinstruments and utensils that have lainidle through the winter, and to meet again theold problems where you left them, as to whetherthe fruit-bag should be hungbeside the windowor beneath the candlesticks, as to which fryingpanshould be reserved for omelettes, as to whichhook must be kept for the wheel-key.I am thenin the position of a collector who has been restoredafter a long absence to his possessions.I cannotpoint to an ivory drinking-cup which I picked upin India or a calabash pipe from Johannesburgor an Italian statuette, as some may do. But Ihave the small, squat,blue kettle that came out18

THE DOMESTIC SIDE 19of a village shop in Cheshire, the Sevenoaks teapot,the tumbler with the scratched inscriptionupon it, which, if everyone had his rights, belongsto a small public-house in Cumberland. I havewhat I believe to be the only really efficient pairof housemaid's gloves, which I found in an ironmonger'sshop in Beauly and my best corkscrew;hails from Aberdeen. Memories cluster about eachtea-infuser and cruet-stand. My belongings havebeen lovingly accumulated in all parts of the land.And it isalways good to be back among them.There are allsorts of preliminary stepsto betaken in these first few days.The cook is helplesstill he has begun to build up his dripping-bowl :the rough-paper bag must lay in stock : sodawatermust be made : a small glass jar must beinaugurated as an ash-tray,for when you havebeen at the game as long as I have youknock off cigarette ash into cupswill notor saucers :there are oil-tanks to fill, new wicks to stretch,cloths and cleaners to apportion. All theseintroductory operationslaying of foundation stones.are full ofpromise, likeEspecially I should like to tell you of my housemaid'sgloves. They are a remarkable pair,peculiar I should say to the Beauly neighbourhood,for I have never seen their like elsewhere,

20and there is of course enormous range in thequality of housemaid's gloves. I think if I werea millionaire I should always use chamois leatherand order them in dozens of pairs. There isnothing to compare with them in comfort andappearance, and it is a delightful sensation towash them, soapily. They also fit so close thatyou have the satisfaction of being nearer to yourjob in them than in the other sorts. But they arefeeble to protect you in the lifting of hot plates,and they simply will not stand the wear that Iputon them. Ihave tried many of the toughersorts. Some remain clammy after washing :some are too clumsy some grow hard and :crack,and many shrink. My Beauly pair alone havenone of these failings. They have already seenlong service and are all the better for it. Theyare strong and tough and soft and generouslylarge, of a fine buff colour, and their special meritis in the fact that like Norwegian ski-bootsthey are built with the seams outside.I am myself the cook. Throughoutof my experience of caravanningthe wholeI have heldabsolute sway in the kitchen. For years Imaintained the right to throw out of the doorwayany unauthorized pot or pan that appeared uponthe hob, and that I now admit a certain measure

THE DOMESTIC SIDE 21of co-operationis due to the decided talents thatmy Partner has displayed in the matter of theSweets a department that I had perhapsneglected.I shall never be a good plain cook.I sometimeswonder if,even in these days of rising wages, Ishould be worth twenty pounds a year to anyone.For there are great gaps in my experience.My fixed determination to have nothing to dowith cookery books and to spurn the advice of theexcellent Mrs. Beeton has restricted my knowledgeof the common fare of e very-day life.itButmay, I think, with truth be said that with allmy shortcomings there is about my cookingsomething of that dash and originality whichcharacterizes the amateur in every branch ofsport. I pride myself on making much of humblethings, for it is when the forager has failed andsupplies are low that the caravan cook must riseto his best efforts.I should think little of him ifhe could not make fish-cakes without fish.Aboveall, I like to deal with the potato and the egg.Theyare both a constantstand-by, but widelydifferent in character one of a grand consistency,apt to be carved or chipped or shredded,mashed or moulded : the other with a wide rangeof body and fluidity, from the merest froth to an

22 CARAVAN DAYSalmost leathery slab. One is dour and slow tocook, the other active and responsive. Whilethe potato must be goaded and pushed forward,the egg must be retarded and held back.Perhaps the hour or two before supper, on anight when I have a big campaign on hand, isthe time that I recall most gratefully in the cycleof the caravanner's day.The period of preparation,cutting up, mixing, peeling, buttering,blending is well over and everything is under way,each member with its proper handicap, so that allwill reach the post together. Delicious hiddenprocesses are going forward in the oven, simmeringpots crowd the top of the stove. Only the pancakesremain for a final spurt on the Primusstove when the table is alreadyset. There isplenty of quiet occupation in stirring, flavouring,peering into the oven, lifting a lid now and then,moving a pot from one station to another. Thefront of the van isopen and I have ample timeto contemplate the traffic of the stackyard in thetwilight,to watch Herbert putting up his tent,or exchange a few words with a passing ploughman.And before the final rite of dishing up Ispend hilarious minutes, with gloved hands andfrying-pan, tossing pancakes, slithering them toand fro, rolling and punching and building them

23into a pyramid. And if, as is most likely, I havean experiment in the oven, there will be plenty ofexcitement when we come to dishing up.Caravanning contains no more delightful featurethan itspower of elevating and ennobling sordiddomestic jobs. I have often told myselfthat itcannot really be any fun to peel potatoes,or itwould have been discovered long ago. And yetas I sit on the door-mat by the side of the streamwith a pointed knife and a bucket I am quiteunconscious of any lack of interest in my work.On the contrary, as long as potatoes continue toshow the magnificent variety in substance andcontour that Ihave always found in them, thisis an engrossing pursuit. The filling of oil-tanksand trimming of wicks, a dutythat falls tomylot early in the day, might possibly repel theunaccustomed.But I rather like to feel the wickscrunch as I rub it down, and it calls for a goodeye and some sense of balance to succeed andget a clear white flame, quite free from peaks andundulations.The important matter of shoppingalso ceasesto be a necessary evil and becomes a delightfulexploit. I like nothingbetter than to come totown, draw up at the post office and, dividing thelist among the members of the crew, assume my

24 CARAVAN DAYSmarket basket. The ironmongerisalways ahappy hunting-ground for fresh discovery, butgenerally my most important item is the visit tothe butcher. I am not now very easily taken inon the question of meat. You will not find mecarrying away a sirlointhat does not stand upor steak that is cut too thin. With the grocer Ilook forward to some pleasant discussion while heis slicing the bacon, and there are sundry oldwomen in dairies who are worth a visit. WhenI have looked round and exclaimed with enthusiasmwhat a delightful shop this is, I generallyfind we are on terms and she must see the interiorof SIEGLINDA before Idrive away.in theBy degrees I have lost all shame about shopping.It isnothing to me now to pull uphigh street of a popular resort and open my backlarder for all the world to see, while I kneel downand fill my egg-box: or to set off across the roadwith an oil-can in one hand and a case of emptybottles in the other. A caravan has a way ofexplaining these things, even as it explains one'scostume and appearance. It is a safe passportto the goodwill of the neighbourhood.But despite my love for myutensils there aretimes when they exasperate me beyond measure.For with all my ingenuity and with all my years

THE DOMESTIC SIDE 25of practice I cannot keep them still. There isno more baffling problem in a caravan than theprevention of the twin visitations of jibbing andchittering. The wind cannot be entirely to blame :I often feel that it is no more than a pretext.Forthe thingisbrought about by some sort of evilconspiracy among my goods and chattels. Otherwisehow is it that an oil-can on a hook will remainsilent for half the tour and then suddenly lift upits voice in the dead of night in response to thegentle knocking of the frying-pan against thekitchen wall ?Of all the adversities that we have to face thisis the only one that reduces me to despair. Forthings only jib and chitter in the night, and theynever start till the light is out. I am thinking ofa night at Melvich, on the way to John o' Groat's,when we were in an exposed position and the windwas high. I waited and listened long beforeputting out the candle and I found about me thesilence of the tomb. But a quarter of an hourlater, just when I was on the verge of sleep, thefun began. I heard a subdued and rhythmiccreaking just below my head. That was theroller swinging. Had I been new to the game Isuppose I should have got up at once and silencedit, but I knew better. I faced the fact that I was

26 CARAVAN DAYSin for one of those periods of hectic and variedactivity, known in a caravan as a night's rest.And so I waited for a bit that I might kill twobirds or more with one stone. Soon I heard theplaintive moan of a restless bucket, and after thatone of the cups on its hook in the corner cupboardbegan to tap very gently and at irregular intervals.Then I got up and fixed these three.The next effort was a sort of scraping, scoringnoise, a rubbing, a grinding, a swaying back andforth. This I could not place at all. I did noteven know if it was inside the van or out, andevery time I got up to look for it, it heard mecoming and stopped. My Partner made somehelpful suggestions as that it was something onthe roof which might be reached with the ladderif it was near the :edge but it was a long timebefore I ran it to earth. It was the whip swingingagainst the side of the van where some idiot hadhung it. I flungit as far as I could across themoor and got back to bed. Then the door beganto chatter and had to be wedged. . . .As the night wore on I grew more and moredetermined. When I fixed a thing I did not haveto fix it twice. I was soon crawling about witha hammer and nails, a few wedgesand a ball ofstring. There are all sorts of ways of jamming

27things. Perhaps the . things that simply flap. .are the worst. I caught my razor-strop at thatgame. I do not think that it will do it again, butit is true that it was not improved as a stropby the four-inch screw that I put through it.And at last I succeeded, long after dawn, andwent to bed with a fine sense of stringency andtautness all about me. But when Herbert greetedme in the morning and wanted to know if I hadhad a good night I told him that I was thinkingof a plan of having a little chamber made in thegarden at home, hewn out of the living rock, witha lid a place where I could crawl in and spendthe first night after my return.

CHAPTER IVTHE HUMAN SIDEAND of course the road is the place to meetpeople, and caravanning stands almost alone inits faculty for fortunate encounters. Those whoare of a morose or solitary habit would do well totry some other way of life, for the caravannerfalls in with all sorts and conditions of men andhe has everything in his favour to put him on goodterms with them. He does not, as some may do,fling his dust in their faces and rush on, nor doeshe pride himself on avoiding other wayfarers by"keepingoff the beaten track." And if hetravels with an open mind, fullof curiosity andready for adventure, he will let slip no opportunityfor making new acquaintances.I can look back upon a vast and variouscompany of them, made up of caravanners likemyself, of tinkers, stone-breakers, road surveyors,policemen, farmers, schoolmasters, ministers,shopkeepers of every degree, artists, sportsmen,gamekeepers, school children, tramps, magnificent28

THE HUMAN SIDE 29people in motor-cars, grubby people in donkeycarts,railway porters and hotel proprietors, andthere are veryfew of them who have not donesomething to help me on my way.It is a mosthappy relation, this of the caravanner to thepeople of the country where he travels. Itcreates an atmosphere of hospitality. For thecaravanner isimmensely dependent upon theinhabitants. He islooking for favours, notdemanding rights. Every camping-ground is aconcession. He is the guest of a whole neighbourhood.And I do not know how it is but there isthat about him that touches the hearts especiallyof kindly and comfortable old ladies.to feel that there issomethingThey seemforlorn in hisposition, travelling as he does without a properroof over his head. And they want to ministerto him.This hospitable spirit works both ways. Fora caravan itself is the most approachable ofdwellings. It has no high hedges or trellises orfrowning gateways to keep out the passer-by, andeveryone, without exception,what it is like inside. So that we have manycallers. One of the queerest of them alldroppedin one evening when I was camped in the cornerof a stackyard at Bonar Bridge. My Partneris curious to see

30 CARAVAN DAYSwas lying down for half an hour before supper,and I was at work at the stove when I wassuddenly aware of someone sitting on the stepand peering into the van, with his head just on alevel with my feet." Are yer fond o' toorin' ? " he asked, withoutany further introduction. I told him that I was :and he sighed. He had had a caravan himselfat one time, he explained, and had lived in itfortwo years. But he had tired of it. He was ashabby little, dried-up, disconsolate-looking man,an Englishman.I asked him about himself,and he told me that he was an itinerant photographerand was walking through the villages,taking " growps." His heart seemed to be full ofpity for me." It's allvery fine and large fer a time fer aweek or two. But you'll tire of it, same as I did."" Oh, I don't think so," said I." Yes yer will. Stands to reason. Ye'll tireof it in time. Ye'll feel a a a sort of atameness."He shifted his position and rested his elbowon the floor. "I 'ed to give it up, yer see, so Iknow."" But why did you give it up ? " I asked." Didn't itpay ? "

THE HUMAN SIDE 31" Paid like smoke. But it worn't any good."There was a pause, and then he added, confidentially,in an undertone, " Couldn't stand themonopoly."" Oh, that was it ? "" Yes : week after week. Yer wouldn'tbelieve 'ow itmonopolous were.ter think of a way out."I've often triedI assured him that I had never suffered in thatrespect, that, on the contrary, I found itveryentertaining. But he stillregarded me with aneye of deep compassion. He clearly wanted tohelp me if he could. At last it came to him." "I'll tell yer wot I sh'd do," he said, if I wosyou. If I wos youI sh'd either (it'd be quitesimple, yer know )I sh'd either run a little bitof a circus or 'old religious meetin's. It don'tmatter w'ich.That's wot I sh'd do."I had to turn away to put the hot plates on thetop of the copper, and when I looked round againhe had gone, which was a pity, as I should haveliked to have had some further conversation withhim, and I think my Partner would have beenpleased to meet him.It is not in the nature of things that all ourencounters should be entirely friendly, but theonly time that I found myself seriously at

32 CARAVAN DAYSvariance with my neighbours was on the greatoccasion of Sam's night out. I shall have muchto tell you of the horses, and you will learn thatthis incident was quite in keeping with Sam'scharacter, while Simon's behaviour was exemplarythroughout. We were camped at a little villagein Inverness-shire, and the horses were put upin the hotel stable along with a small, lean, whitepony belonging to the Postman. There was ofcourse no eye-witness of the dark doings of thatnight, but as far as we could judge from theevidence that remained in the morning, thiswas what happened. First Sam broke loose :then he went over and liberated Simon who,however, took no part in the affair.After that,with some ingenuity, he opened the door thatled to an adjoining shed. There he disposed ofthe greater part of a bag of oats and topped offwith a square meal of potatoes (which were not atallgood for him).Then he turned his attentionto the Postman's pony, in a spirit, I am convinced,of pure playfulness ; but Sam is a gooddeal more heavy-handed than he knows. Thepony was marked somewhat conspicuously onthe scruff of the neck, which rather looked as ifSam had picked him up and shaken him, as adog might shake a rat. ThereafterSam got both

THE HUMAN SIDE 33feet jammed in the rack, so that he was quiteunable to move, and waited patiently for thedawn.Early the following day which we spent incamp the Postman appeared, demanding heavydamages.I did not like to commit myself to adefinite figure, but suggested that as a basis ofcalculation we should try to arrive at the valueof the pony when enjoying normal health.There we disagreed, for he putit at Ten Poundswhile I putweek or less the pony would be ready for the road.But meantime he must run the mails. He mustit at Three. He admitted that in ahire from the Hotel Proprietor.him Fifty Shillings.That would costIt is needless to follow all the negotiations.The village was soon split into two camps.TheHotel Proprietor sided with the Postman, but theBlacksmith, with a small following, came overto us. And the matter was by no means simplifiedby the arrival of the Postman's Father, who putin a plea (which appeared to be groundless) thatthe pony belonged to him.The great scene occurred when the horses werebrought out of the stable the following morning.The whole village was there, and the yard wasin a ferment. Herbert, whose part had beenD

34 CARAVAN DAYSrehearsed overnight, handed the Postman thesum of One Pound. It was not a question ofany damages or compensation, he pointed out.But the poor man had had his pony hurt, and thiswas a little present for him." I think," put in the Blacksmith ponderously,that Mr. Smith is one in a thousand"toat all."pay anythingThen followed a torrent of argument fromthe Hotel Proprietor (who had already been paidfor his oats and potatoes) with many threats ofan action at law. It was the Blacksmith'sopinion, however, that if it was a question oflaw there was a good case against a landlordwho provided rotten halters in his stables, sothat horses got loose and poisoned themselveswith potatoes. To this startling declaration headded impressively," To my mind he's one ina thousand in a thousand to pay anythingat all."At that point the Postman dropped out.Hewas but a weakling at the best, and he wentoff to the stables, pretty well content withthe spoils. But this was not the end of it,so the Hotel Proprietor assured us. This wasby no means the end of it. It was only thebeginning. He was boldly confronted by the

THE HUMAN SIDE 35Blacksmith for the principals on both sideshad now retired from the arena. The crowd wasveering round, and there were even some whosuggested that the Postman had gone to harnessthe pony. At last Herbert advanced with ahorse in either hand, and the crowd made way forhim to pass. At that dramatic moment theBlacksmith broke the tense silence, as ifsummingup."The plain truth is," he said," he's one in athousand."And so we drove away, and Ineed not dwellupon our encounter with the Postman's Mother,who met us on the road, protesting that the ponyin reality was her private property.Even in the most pleasant wayside conversationson a caravan tour one cannot, I suppose,always expect to meet with original views, andthere is a certain bogy of reiteration which pursuesme. If I relate to you what happened when I wentshopping in Aberfeldy you are to understandthat this isonly a fair sample of what alwayshappens equally elsewhere, except that this wasthe only time that I rebelled.I had started with the butcher, who had beenkeeping his eye upon the expedition through hiswindow ever since it arrived.

36 CARAVAN DAYS" It must be a nice way to see the country," heremarked cheerfully." Oh, yes," I agreed." It's an ideal holiday.I want a square little sirloin about six pounds."" I dare say you like that better than motoring,"he went on, " "because" Because," said I (for I know the answer tothat one by heart)," you are not in too great ahurry and have plenty of time to look about you.Very well, six and a half, ifyou like. Better putin some suet."I had to go to the baker next." It must be an ideal holiday," said the youngwoman, as soon as she had established myconnection with the caravan." " Oh, yes, yes," said I. That is so.By allmeans."" And such a nice way to see the country.""Quite," said I. "I want a half -loaf, and Imust have one that doesn't bulgeor itwon't fitmy tin." I got off with that, but I passed aflorid old gentleman with a stick, as soon as Igot out of the shop, who was maintaining, inconversation with Herbert, that in his opinionit was a long way better than a motor, asifyoucame to think of ityou were able, not being intoo great a hurry, to look about you and see

THE HUMAN SIDE 37the country. I hastened on, with avertedhead.When the grocer concluded that it was an idealway to see the country I felt that he was mixingthings up rather. However, I put in the littlebit about the motor and not being in a hurry.And I thought that that had finished him. I wasdisappointed when he reverted, jumped back andbegan again in the middle of the bar." I think it must be a perfect holiday," he said,as he handed me the parcel" er er ideal.""Quite," said I mournfully. He was apleasant fellow, this grocer. I felt that, nowthat we had exhausted the preliminaries, it was apity not to have more conversation with him.But Ihad to move on to the chemist and beginall over again. They had nearly worn me outamong them, and I felt at first that I couldhardly face it. But I pulled myself together andwent in." "Do you see that caravan out there ? I askedsternly." Yes ? Are you sure ? Well, it belongsto me. I travel in it. I want to make it clearto you that it is an ideal holiday." He tried tobreak in, but I talked him down. " I think youwill agree with me that it is a nice way to see thecountry. I prefer it to motoring, and do you

38 CARAVAN DAYSknow why ? Because I am not in too great ahurry, and thus have plentyof time to lookabout me. And now " I took a long breath" I wish you would let me inspect your stock oftooth-brushes."

AND now ICHAPTER VTHE CARAVAN " SIEGLINDA "shall have to describe the CaravanSIEGLINDA. It is not without a certain emotionthat I present her to you, for you will understandthat she is worth something more to me than thesum of her component parts, after all we havebeen through together. She issimply my idea ofthe Perfect Caravan, and I do not believe thatthere isany point in which I can improve uponher. I have only arrived at her by a long andcomprehensive process. She is the last of aseries of caravans, each of which has been tested,altered, adapted and superseded in its turn,and she has now gone through the final and mostnecessary stage of long experience. For I havelived and toured in her for many months,travelling by all sorts and conditions of roads,camping in all manner of places, encounteringall varieties of weather and making smallimprovements and modifications all the way.Perhaps I have done my work too well.39When

40 CARAVAN DAYSnext I take the road I am afraid that a coat ofvarnish is all that will be called for, and I shallmiss something in those pleasant feverish weeksof " fitting out," which used to be so full ofsearching tests and fresh inventions.She is nearly eighteen feet long, six feet sixbroad, three feet six high, to the floor, and tenfeet to the roof. She is built of three-ply oakpanelling, three-sixteenths of an inch thick, witha frame of oak, and a roof of red Oregon Pine,covered with white canvas. She has one screwbrake, worked from the front, and since myjourney to John o' Groat's I have fitted anotherbehind (operating on the back of the back wheels,so that they are gripped on either side)for usein emergency. This has taken the place of theslipper. The under-carriage projects about twofeet in front of the body of the van, forming alittle platform. She has a full lock, sound axlesand springs and strong carriage wheels, aboutthree feet in diameter, with steel tyres of twoand a half inches breadth. The wheels are setwell below the body.We shall now have to have a ground plan of theinterior. I have shown it with the tables foldeddown and the chairs up, so that we may haveroom to move about, and I should explain that it

THE CARAVAN "SIEGLINDA" 41contains no mysteries or complications. Withthe exception of the tables and chairs and thewashstand, there isnothing that folds or tilts,or collapses or disappears. I cannot of courseget everything into my plan, without confusion,but I have shown the general arrangement.The Kitchen is a small compartment, entirelyopen, in fine weather, to the front. There is arecess in the partition wall, which holds theRippingille stove, with its six-inch wicks ateither end and large oven in the middle. On thetop of this rests a square copper box, holdingfive gallons of water, which can be heated to theboiling point in about a coupleof hours. Thatis an excellent innovation, as the demand forboiling water used to keep my hobs closelycrowded with kettles all the evening. Below thestove is a drawer full of treasured cookingutensils, an egg-whisk, grater, apple-corer, alarge pair of scissors and many more.Here alsois a dripping-bowl and sundry flavourings. Upone side of the stove run a series of little leatherpouches (made out of the fingers of an old pairof gloves) which hold my private knife, fork andspoon, and salt and pepper dusters. Above thestove the recess is filled with rods and hooks fordrying clothes and shoes. There is a folding

42 CARAVAN DAYStable at my left hand and over to the right, ifstretch a long arm, I can reach the cold-watertank (which also holds five gallons) and chargemy beaker at the tap. In this way all the haulingabout of cans and buckets inside the van, whichis apt to make life a burden, has been eliminated.Above the cold tank is a corner cupboardIfull ofcrockery, and below it the housemaid's pantry,screened by a curtain. Finally, far above myhead, as I sit on my camp-stool at the stove, areone or two hooks for my housemaid's gloves,kitchen towels and the members of the underworld(of whom I shall have more to tell).ThePrimus stove is set on the floor when in action.It is chiefly called upon for quick frying. Andslnng on the wall by leather straps is my seasonedbrace of wooden spoons known to me as Sweetand Savoury.Ibelieve that all highauthorities on caravanninghave condemned the Rippingille stove, andevery other oil stove with wicks, as obsolete.Some uphold the " duck " oven and cookers ofthat type: others are in favour of coal. For mypart I have tried them all and returned withgratitude to the Rippingille. The coal stovewhich used to occupy the kitchen of SIEGLINDAwas not abandoned without a pang.I doubt if

THE CARAVAN "SIEGLINDA" 43she has ever looked so well as she used to do ona stormy night, with the smoke whisking awaybefore the wind, from her little white-bonnetedchimney. And in bad weather there was muchcomfort in the glowing coals, not to speak of thetoast they made, that was not to be lightlyforgotten.But that tiny kitchen range had toomany drawbacks, and it was given up after theJohn o' Groat's journey. It necessitated notonly carrying a chimney, but a ladder to takethe chimney off and on. It was heavy in itself,and called for heavy, dirty fuel :and it was noteasy in remote places to get coal. Further, theoven could not be kept up without insistentattention, and a hot oven is the backbone ofsuccessful cookery. With my old ally, theRippingille, the oven is hot in ten minutes, andmaintains an even heat thereafter. And it isvery hot, for it soon runs my oven thermometerto its limit of 400 degrees. The Rippingille alsocan be perfectly regulated, turned down andsafely left. By leaving one lamp very low atnight I can count on a supply of hot water, inmy copper box, in the morning. And that is agood long step into the routine of a new day.The Primus stove, the faithful servant of allwho must get their own meals in a hurry,is a

44 CARAVAN DAYSvaluable second string. But I should like toexpress my hearty contemptserious cooking with spirit lamps.for all efforts atI would aboutas soon try to carve with a penknife or digpotatoes with a spoon.Let us now look into the Middleroom. Itswalls are of dark green painted canvas, and thewoodwork is white. It is almost square, butone of the corners, as you will see, is missing,owing to the bite taken out by the kitchen recess.There are three folding chairs and tables on eitherside. The windows on both sides slide up anddown.But the strong point of the middleroomis the complete and ingenious occupation of itswall-space. It would not be easy to lay yourhand upon any part of the wall that is notrendering special service. Above my Partner'shead is a small corner cupboard (salt, pepper, tea,coffee, etc.), and below that an ink-bottle andpen, slung in leather loops. Near the roof, in theOld Campaigner's corner, is a light railway rack,corresponding to a similar one above my ownhead. On the side walls are a bag for fruit, ahook for candlesticks, a satchel for unansweredletters. The wall at the back of the recesscarries a knife-and-fork box lined with greenbaize, carvers, corkscrews, tin-openers in leather

THE CARAVAN "SIEGLINDA" 45loops, and at the floor a canvas rough-paper bag.Above there are many leather loops, for map,diary, contour-book, letters for post, newspapers.Finally, in each corner hangs a pot for flowers"on a hook, an institution which greatly sets" off the room without adding to the number ofloose properties. For the small, exasperatingtraffic in minor chattels, with no fixed place ofabode, must always be cut down. Everythingdayyou are likely to need in the course of theshould be at hand, and even visible, but it shouldbe well out of your way and firmly fixed.Thatiswhy we have so far developed the wall-worksof the middleroom.I am afraid that there is not much more to bedone to this room.The Head Mechanic sits andponders on it sometimes in the quietof theevening, trying to devise improvements ; butthere is little scope for him left.The Bedroom is about eight feet by six and ahalf, and I do not think that more solid comfortwith so little confusion could be packed into thespace. For I count the bedroom to be the creamof SIEGLINDA. A double bed, four feet in breadth,made of wooden slats like those often used onboard ship, occupies the far end. A broad shelf,capable of being used as a bed, crosses the foot

46 CARAVAN DAYSof it, some twenty inches higher. This carriesall the extra bedding belongingto the tents.Between the end of this shelf and tne partitionis a tall, narrow chest of drawers, above that abookcase, while below the shelf (between thechest of drawers and the bed)is a wardrobe,covered by a curtain.The only window is on the opposite side. Ithas a sliding shutter that obscures the lower halfof it.In the large angle of wall-space above thebed there are many thingsa corner cupboard,a railway rack, a swinging candle-lamp, a coupleof long bags of strong linen, divided into compartments,which carry all the boots and shoes.These are generally out of place on the floor,and have a horrid faculty for getting kicked awayinto inaccessible corners and beneath low-lyingobstacles.Below the window isa table, and beside thata folding wash-stand, whose disused water-tankhas been divided up to carry bottles.Under thebed is a linen-chest in the form of a huge drawer,which contains an immense amount of stuff.There isspace behind that where all such thingsare stowed as are not likely to be wanted in everydaylife. There is also room at the end of thechest for camp beds.

THE CARAVAN "SIEGLINDA" 47On the roof above the shelf is a hat-rack ofcords.The clock isstrapped to the wall above the washstand.There is a tight little corner beside the windowfor fishing-rods and The Umbrella.Pipes go on the top of the bookcase ;therolling-pin and board on the top of the linenchest;the writing-board on the wall above theshelf ;and all wandering odds and ends are flunginto the railway rack.There are elegant curtains.At night a perpetual draughtis secured bychaining back the door and opening the windowsof the middleroom as well as that of the bedroom.But that programme may be modified by thedirection of the rain.A carpet cannot possibly be kept going in acaravan, where all the muddy traffic is confinedto a few square feet. The floor of SIEGLINDA iscovered with cork matting, and she carries acharming little woolly rug, which makes its soleappearance at dinner parties.

CHAPTERVICREW AND EQUIPMENTMY PARTNER and I divide the duties of our householdso that there is no overlapping and we neverget into each other's way. I am Cook, Scullionand Head Mechanic : she is Chambermaid, Seamstressand Official Photographer.I am on myown ground in the kitchen, while she rules witha rod of iron in the bedroom. In the middleroomwe maybe said to meeton equal terms.I am not quite able to explain why the making ofmustard rests with her, while the charging of thesoda-water syphon is in my hands, but such finedistinctions are well understood between us, andwe are perhaps both a little jealous of our ownspecial jobs and resent encroachments.When we have visitors with us they sleep in aand we can manage pretty comfortably totent,accommodate four at table in the middleroom, myPartner sitting on a camp-stool. In an emergencythe middleroom can be converted into a bedroomfor two,48

CREW AND EQUIPMENT 49We carry two tents,one for Herbert and onefor visitors. These are Alpine tents of a floorspace of about seven feet square, and are builtwith the floor-cloth sewn on and the poles sewninto the corners, so that they can be instantlyrolled up, all in a piece, and slung in the crutch.The crutch isthe back of the van, hingeda barred structure, like a gate, atat the bottom andswung out as far as is necessary on chains. Itcarries a sack of oats besides the tents, horsecloths,nose-bags and so on.Under the van at the back is a larder and boxfor pots and pans, and the whole of the restthe space beneath the floor is taken up by a net,which holds camp furniture and odds and ends.We take three camp beds, two small tables, somechairs and camp-stools. Buckets and oil-canshang on hooks, along with a bag for vegetables.On my last journeyI took also a new andspecial invention in the form of a camp-stable,to be used when we wanted to stop in lonelyplaces where there was neither stabling nor grassfor the horses. It is a sturdylittle structure,about seven feet high, in shape like the letter H,and supported by pegged ropes. The horses aretied to the cross-bar face to face, cloths are puton them, boxes of oats slung to the bar and a netEof

50 CARAVAN DAYSfull of hay suspended overhead.As it turned outthis stable was never used, as we always foundgood accommodation, so that its efficiency hasnot yet been tested. It remains an open questionwhether Sam would have contrived to wreck itin the watches of the night or not.We also carry a spade, a scythe, a bag of tools,rope, a few spare straps, polish for harness, brass,boots and stove ; dubbin, nails, and extra brakeleathers.I shall have so much to sayof the horses in thecourse of my story that here no more is necessarythan a bare introduction. Sam has been on thefarm for several years, though he was new to thecaravan. He stands a full seventeen hands highand is of a rich dark grey, with a most appealingcountenance. He is a horse of great power andof a most lively disposition.There isnothing hefears so much as being bored. Simon, who wasonly bought a week before we started, as a matchfor Sam, isof a lighter greyand a more slenderbuild. He is a willing, dogged soul with a constitutionalobjection to rain in his face, whichfusses and irritates him beyond measure. Wehave more than once discussed the question offitting him out with an umbrella.Herbert looks after the horses, brings water and

CREW AND EQUIPMENT 51supplies, and the rest of his time is given overfor the most part to polishing, rubbing, shining,furbishing to keeping the caravan itself, theharness, boots and shoes, candlesticks, lamps,knives, forks and spoons and half a hundred otherthings bright and clean.

CHAPTER VIITHE TROUBLES OF THE CARAVANNERAND now before we start together upon our dashto John o' Groat's and thereafter we shall discussmy other journeys of the last two summers itoccurs to me that there may be something moreto be said upon the general question. It ispossible that the reader may look to me for adviceupon some points which do not happen to bedealt with in the narrative, especiallyif he isquite without experience of caravanning. AndI have so often met with beginners who have gotinto trouble on their first tour that Imay be ableto help him with a few suggestions.The first and most difficult questionand Where to hire a Caravan. It is almostis Howessential to obtain one in the neighbourhoodwhere the tour is to take place, as it is awkwardand expensive to send them about the countryby rail. And the supply so far is very inadequate.I have given you my idea of what a caravan shouldbe, and I can only advise you to apply52to the

TROUBLES OF THE CARAVANNER 53Secretary of the Caravan Club (83 AvenueChambers, 42 Bloomsbury Square, W.C.), who hasa list of caravans for hire in various parts of thecountry, and there to try to find what you want.As to horses, the most likely field is to be foundin the small country towns. A horse that comesfrom the city is rather out of his element oncountry roads and consuming country fare.Every town of two thousand inhabitants or morehas a carting contractor among its tradesmen,with horses accustomed to just the sort of journeysthat you are to make. Prices vary greatly indifferent parts of the country, but I have alwaysheld about 22s. 6d. a week a fair charge for horseand harness (of a strong dogcart type)if both areequal to the work. As a general rule your horseshould be stabled at night, but there is no reasonwhy he should not lie out in good weather,provided he gets plenty to eat. But if grass is tobe substituted for hay in this manner it should beplentiful and good.It is not enough to turn yourhorse into a bare pasture field, full of weeds, afterhis day's journey.If he is stabled he should haveas much long hay as he can eat, and in either casetwo feeds a day morning and evening sayabout a stone to a stone and a half of oats in all.If you stop when your horse is overheated you

54 CARAVAN DAYSwill not omit to throw a cloth of some sort overhim, and it is better to water him just beforestarting again than to allow him to stand a whileafter drinking.I find on an average, in continuous travelling,that horses need to be shod about once a month,and wheels and lock should be oiled at about thesame interval.Never tie the horse to the van at night, or youwill get no sleep. Never tie the reins to the bodyof the van when the horse is in. If you have to tiethem, tie them to the undercarriage in front.Otherwise, if the horse turns, as the lock swingsround the reins may tighten suddenly and nearlystrangle him.In selecting camping-ground, gates are a firstconsideration. Remember that your principalinterest is not \vhat the front of the van is doing,but what isgoing to happen at the far end of it.The breadth of the road out of which you areturning is quite as important as the breadth ofthe gate itself.Many novices in the art get thecaravan horribly scarred and mauled by chargingincautiously through gates, without any nicecalculation. It isonly necessary to go slow, and,ifyou see trouble before you, to back out andstart again. In camping avoid soft ground and,

TROUBLES OF THE CARAVANNER 55ifyou find your wheels are going to sink, look outfor four short boards or'planks (which are generallyto be picked up not far away) and draw on tothem. Otherwise you are in for trouble in themorning. Be careful to camp with your back tothe wind. If you have rain driving into the vanat the front itcomplicates matters.Give lamp-posts a wide berth.To show thenecessity of that injunction I may say that Iknow of four several lamp-posts that wereknocked down by caravans one of them bymyself. It isvery easily done, as if the wheelis close up to the kerb the topof the vanprojects some inches over it.Avoid a field with cattle in it.They arevexatious neighbours.I have never myself got into trouble throughcamping by the road-side, but it is well to avoidit, except of course on the openmoor. Thereare local by-laws regulating the number of feetof clearance on each side of the road which mustnot be encroached upon. And ifyouare everforced to remain overnight too near the road forabsolute safety, do not fail to leave out a lamp.There are also by-laws in some counties, enjoininga rear light, if the vehicle is more than eighteenfeet in length.

56 CARAVAN DAYSare toFinally you may want to know ifyoutake a bicycle. It is sometimes useful for forag-:ing and it is a terrible nuisance at other times.I shall never take one again. There seems to beno room for it in the scheme of things. I carriedone to the far corner of Sutherland, on the wayto John o' Groat's, by which time it was in no fitcondition to use, thoughI had never had it downoff the crutch. And there I gratefully sent ithome. It is easy, in an emergency, to borrow abicycle at almost any cottage.

CHAPTER VIIITO JOHN:o' GROAT'SiWE did not set out for John o' Groat's with thesingle aim of reaching our goal by the easiestroute. We travelled, as will be seen by the map,in a series of great zigzags up the heart of Scotland,exploring the country far and wide as wewent. For we had gaily concluded, when firstthe project was discussed, that we would go upby the West and come back by the East : andour erratic course was due to our determined andpathetic endeavours to reach the West Coast.This West Coast, North of Glasgow, provedfor us. Ialtogether too tough a problem hope itmay be possible to do it some day with a ponycartand a tent, but it is almost beyond the scopeof a caravan. At every point as we approacheditdangers and difficulties increased about us.Not only are the roads generally bad, with manybarbarous gradients, but the whole of that side ofScotland is so torn into rags and tatters by armsof the sea that the traveller is often confronted57

58 CARAVAN DAYSby ferries, most of which are incapable of carryinga caravan of the size of SIEGLINDA. Thus we werecontinually boring into the West, only to bepulled sharply back again. We stuck to it to thelast, and it was in the extreme North-West cornerof Scotland that we made our final attempt. Butit was not till the following summer that wesucceeded.The great moment of our departure lost somethingof its effect through gloomy weather thatdid not make for enthusiasm. But it was with aheavy cargo of good wishes that we turned up thelane among the dripping beech trees,picked upa milk bottle and a last coil of rope at the corner,and drove away to the North. We had a thousandfeet to climb before lunch, and all the way up theOld Edinburgh Road from Moffat we rolled alongin the centre of a small moving circle of streamingtrack and glistening sodden moor, shut in bymist and rain.That was a long, slow, steady pull, but whenwe stopped to water the horses at the summit wefelt that we had made a bold start upon ourenterprise. Already we had reached a higheraltitude, with one single exception, than any thatwe were to attain on our whole journey. Alreadywe had crossed our first watershed from the

TO JOHN O' GROAT'S: I 59Southern to the Eastern slope of Scotland.I liketo divide the whole of Scotland into the fourslopes to East, West, North and South, accordingto the flow of the rivers, when I speak of ourroute to John o' Groat's.Seven times were we tocross main watersheds from one slope to anotherbefore we reached our goal, and these crossingswere the chief landmarks of our journey. Forthis was a real campaigning march, such as I havenever undertaken before or since. Our chiefpreoccupation was in gradients and altitudes,and it is in such terms that I remember it. Theother journeys that I have to describe were of adifferent order. I look back upon them rather ason a great map of the country that has come tolife ;I am not much concerned with the rise andfall of the land. But on the road to John o'Groat's I always think of SIEGLINDA as toiling upor down.We camped the first night at Tweedsmuir, andthen left the Edinburgh Road and travelledthrough Biggar to Thankerton. For the caravanner'sfirstproblem in making for the North ofScotland is to cross the bad belt of country lyingbetween the Forth and Clyde, which is rich inmines and factories and other useful things thatare by no means in his line. Thereare three ways

60 CARAVAN DAYSto cross this belt.You may ferrythe Forth atQueensferry or the Clyde at Erskine, or youmay take the Great North Road between thetwo. On this occasion we crossed by ErskineFerry.On the following night we camped on the veryedge of the mining district, near Larkhall, andafter that we had our first encounter with electriccars. We have no very pleasant recollections ofthe two days that followed through Hamiltonand Paisley for we travelled most of the wayunder riotous and exasperating circumstancesand at an abnormal speed, with Simon in a stateof terror and revolt at the whistling of the overheadwires. All things considered we werefortunate to come through that ordeal withouta scratch on the van. Cars stillpursued us on theNorth side of the river, and it was not till wereached Loch Lomond that our anxieties were atan end.We had wonderful days upon Loch Lomond,of sun and shower and flying cloud, and theseason was that of the grandcrescendo of thefoliage when every day brings forth fresh harmoniesof green. Near Tarbet we came upon oneof the greatest camps of our journey. There wasa long, broad-backed rock, tufted with herbage

TO JOHNO' GROAT'S: I 61on the top and running out into the loch. It wasjust of a size to accommodate the van, withample margins on every side, and it was partlyscreened from the road by trees. Gingerly webacked her on to it till she rested on a level keel,and there she remained with water all about her,while the fine outline of Ben Lomond filled thebedroom window.We were only two milesfrom the county ofArgyll that night, but that is another story anddoes not concern us now.We spent the Sunday at Ardlui, at the Highlandend of Loch Lomond. The other end of the lochis of a gentle Lowland type of beauty :one feelsthat it would not be out of place among theEnglish Lakes. But its character changessuddenly toward the Northern end : the hillsidesspring more abruptly from its banks : theroad issqueezed close between rock and water,and at the top there is a strong impression ofwidening distances and expanding space. Birchwoods appear, flung far up the mountain-sides,and rolling tracts of moor.At Crianlarich we were forced to turn to theEast, the road by Oban and Fort William beingheld up, as far as we were concerned, by the ferryat Ballachulish. And thus our course lay along

62 CARAVAN DAYSa naked hillside to Killin, where we spent Mondaynight, and thereafter, by the fine forest road thatfollows the whole length ofLoch Tay, throughKenmore to Aberfeldy. These were days ofjoyous travel in perfect weather and with no greatdifficulties to meet. But when, at Ballinluig, weturned again to the North-West and, after passingthrough Pitlochry (where we spent a night) andBlair Atholl, advanced up the Grampian Pass toDalnaspidal, we had pretty heavy goingall theway. This is the one main road up the heart ofScotland to the North. It makes its way throughthe only gap in the great barrier of the Grampians,and it is a long and stiff ascent, with an indifferentsurface, rising, through bleak country, with sharplittle undulations for thirteen miles to the summit.And we were impeded by a strong head wind,which added much to the weight of the van. Wespent the night near Dalnaspidal, and an easyhalf-day on the Friday took us to comfortablequarters at Dalwhinnie.We were now of course travelling upon theEastern Slope, but at Dalwhinnie we made asensational plunge over to the West.I have neverbeen able to discover the gradient of the hill thatleads out of Dalwhinnie to the Spey Valley(which perhaps is just as well, as Imight have

TO JOHN O' GROAT'S: I 63funked it if I had known the truth), but it leapsheadlong up the mountain-side in the moststartling manner, and as the surface was bothrough and gravelly it took us just all our time toreach the top, which we did at a single burst.We remained up there for three or four adventurousmiles, and as we approached the steep descenton the farther side a magnificent view opened outbefore us. That is the whole beauty of thesecross-country marches from one valley to another.They are often very severe, but they are generallywell worth it. One has the finest sensation ofbeing perched on the top of things during the fewmiles across the ridge, in bleak, uninhabitedcountry. And there is no way to enter upon anew neighbourhood that you are to explore to becompared with this of coming down from theWe leftheights above into the very heart of it.the Spey upon our right and joined company witha little stream, quaintly called the Pattack Water,which was going our wayto the West. Itbrought us soon to Loch Laggan, where we closeda long week of 105 miles in an exquisite littlecamp among the birches.And now we travelled due West, along acuriously level road which runs across Invernessshirefor thirty miles without ever rising or falling

64 CARAVAN DAYSto any extent from its mean altitude of eighthundred feet, to Spean Bridge.Again we swung sharply round to the North-East and headed up the Caledonian Canal, alongthat strange cleft in the mountains from coast tocoast as if Scotland had been split by a singleblow from an axe which they call the " Great"Glen." It is, I am told, a grave geologicalfault," but though geologists may shake theirheads over it, it has no other fault that I couldfind. For those were memorable days. Thescenery was magnificent and the road, almost thewhole way along the canal, difficult and evendangerous. There are any number of watercoursesto ford, though fortunately (after a spellof dry weather) there was little water in them ;there are some awkward, narrow bridges, and atthe head of Loch Oich the road loses itself to allintents and purposes in a great bed of gravel,continually reinforced by floods from the steephillsides above. As there was a fairly sharpgradient at this point it was only with the greatestdifficulty that we could pull across it, the wheelsploughing in a full six inches deep. Just aboveFort Augustus we found a little quarryfull ofgorse, where we drew in for the night.The next day's march along Loch Ness was

TO JOHN O' GROAT'S: I 65even more difficultcountry.and lay through even finerThe road for a full ten miles isextremelyhilly, narrow and twisty, with some surprisingcorners, and we were fortunate to meet the motorbus, that plies between Fort Augustus andInverness, in open groundnear Invermoriston.Otherwise we were bound to have arrived atstate of stalemate. For the early part of the daywe were steadily burrowing through woods, butsuddenly in the afternoon after climbing aprecipitous little hill we shook off the trees andcame out, three hundred feet above the waterside,with a grand view of the Great Glen and thelong steel ribbon of Loch Ness, Though I am afarmer myself and belong to a hill country, I amstill at a loss to understand how the fields to rightand leftof us were ever ploughedaor harvested.Especially those on the lower side seemed to slantperilously to a sheer cliff above the loch.I fell towondering if the turnips ever rolled over into thewaters below when they were being shawed.That night we camped at Drumnadrochit.There we leftthe canal and tacked once moreto the West (though this time we never crossedthe watershed), up Glen Urquhart and downStrath Glass. We met with a long and dangeroushill down to Invercannich, where we camped forF

66 CARAVAN DAYSthe night, with a gradient of i in 9. At onepoint I must own that we very nearly purledover into the young birch wood below, which mightwell have set a term to our ambitions. My newback brake was not fitted then, and at the bestof times Ido not care greatly about single-figuregradients.That Saturday was the longest march of thetour. We had hoped to stop just beyond Beauly,but we could find no camp to suit us, and it wasnot till we had passed through Dingwall andreached the coast that we at last drew in to alittle open space between the railway and the seaat the head of the Cromarty Firth. Twentysevenmiles. Fortunately it had been an easylevel road, but the horses had clearly had enoughof it,and Simon for the last half-hour had had allthe air of walking in his sleep.We had reached the Eastern limit of the mapby now, but we were to make one more bold bidfor the West in the week that followed.

CHAPTER IXTO JOHNo' GROAT'S: nWE had now circumvented Inverness. I hadalways thought of Inverness as being somewhereat the top of Scotland, but in the next few weeks, aswe pushed on and the trail lengthened out behindus, we were able to look back on it as dwindlingin the distance to the South. In the meantimewe had some welcome days of easy travel,through the fat and level lands of Easter Ross,a noble country of heavy pastures and splendidroads. On the Monday we touched the coast atmany points and camped a mile or two inland,not far from Tain, and the next day our courselay along the Dornoch Firth to Bonar Bridge.There we entered Sutherland a land bare ofsupplies, with few and meagre roads and, accordingto our brief experience,Arctic climate.with an almostI know very well that it was anexceptional summer, but I shall always think ofSutherland in June as providing a penetrating67

68 CARAVAN DAYSqualityin the Alps.of cold that is quiteunknown in winterAfter a fine march up the valley of theShin, where the road hugs the rushing riverclose and whips about round boulders andover ridges of rock in the most sensationalmanner, we arrived at Lairg, which was tobe our base for a fortnight to come, and afterloading up larders, boxes and lockers, forwe had little idea when we might see a shopagain, camped in a wood by the road-side, a mileout of the town. It was there that we fell in withthe Tinker and his family, who occupied a littleshanty on the opposite side of the road, whenthey were not on tour. The whole of his tribecalled in the evening to see the " gorryvon," andhe himself did his best to dissuade us from ourjourney to the West." There's nothing to see at Scourie," he told me." I wouldn't goto Scourie if I was blind of halfan eye."I do not know if I have succeeded in persuadingyou to look upon Scotland, through my eyes, asdivided into four slopes to North, South, Eastand West. But perhaps a simple diagram willmake the matter clear. Reduced to these plainterms, and seen, let us suppose, from a height on

TO JOHN O' GROAT'S: II 69the coast of Norway, the contour of the countrywould be represented thus :r Ta/rfmu;>

70 CARAVAN DAYSAgain she comes in view half-way up the GreatGlen, and this time reaches the very foot of theslope at Dingwall. And now she has crept up tothe top for the last time, on her way to Scourie.When she returns from this excursion she willhead finally for the North.We had no hope or intention of getting roundthe top left-hand corner of Scotland, for theroads as you draw near Cape Wrath are altogetherbarbarous. If we could but reach the coast wewere quite ready to retrace our steps for thirtyor forty miles. On the firstday the road wasremarkably level, though it had no other virtue.It was very narrow and the surface was alltornto pieces, soft and gravelly and covered with loosestones. We found itweary work, for many daysto come, bumping along with little relief from thecontinual jarring and churning of the wheels.The country also that surrounds the chain oflochs, by which the road passes, is bleak andunkind and monotonously bare. Loch Shinsprawls half-way across the county without doinganything to improve the situation. Every mileof itisremarkably like the mile that went beforeand still more like the mile that follows.On the second day, after toiling far over thecrumbling track, we found most fortunate