THE ADVENT OF ASIAN CENTURY IN FOLKLorE - Wiki - National ...

THE ADVENT OF ASIAN CENTURY IN FOLKLorE - Wiki - National ...

THE ADVENT OF ASIAN CENTURY IN FOLKLorE - Wiki - National ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

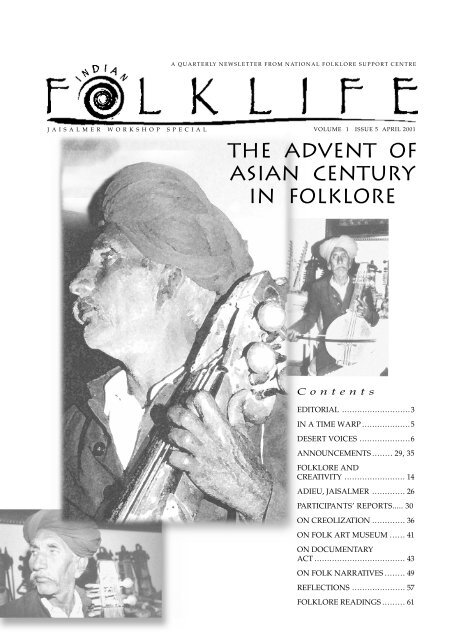

A QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER FROM NATIONAL FOLKLORE SUPPORT CENTREJAISALMER WORKSHOP SPECIALVOLUME 1 ISSUE 5 APRIL 2001<strong>THE</strong> <strong>ADVENT</strong> <strong>OF</strong><strong>ASIAN</strong> <strong>CENTURY</strong><strong>IN</strong> <strong>FOLKLorE</strong>1Contents<strong>IN</strong>DIAN FOLKLIFE VOLUME 1 ISSUE 5 APRIL 2001EDITORIAL ...........................3<strong>IN</strong> A TIME WARP ...................5DESERT VOICES ....................6ANNOUNCEMENTS ........ 29, 35FOLKLORE ANDCREATIVITY ........................ 14ADIEU, JAISALMER ............. 26PARTICIPANTS’ REPORTS..... 30ON CREOLIZATION ............. 36ON FOLK ART MUSEUM ...... 41ON DOCUMENTARYACT.................................... 43ON FOLK NARRATIVES ........ 49REFLECTIONS ..................... 57FOLKLORE READ<strong>IN</strong>GS ......... 61

<strong>National</strong> Folklore Support Centre (NFSC) is a non-governmental,non-profit organisation, registered in Chennai dedicated to thepromotion of Indian folklore research, education, training, networkingand publications. The aim of the centre is to integrate scholarshipwith activism, aesthetic appreciation with community development,comparative folklore studies with cultural diversities and identities,dissemination of information with multi-disciplinary dialogues,folklore fieldwork with developmental issues and folklore advocacywith public programming events. Folklore is a tradition based onany expressive behaviour that brings a group together, creates aconvention and commits it to cultural memory. NFSC aims to achieveits goals through cooperative and experimental activities at variouslevels. NFSC is supported by a grant from the Ford Foundation.2S T A F FProgramme OfficerN. Venugopalan, PublicationsAdministrative OfficersD. Sadasivam, FinanceT.R. Sivasubramaniam,Public RelationsProgramme AssistantsR. Murugan,Data Bank and LibraryJasmine K. Dharod,Public ProgrammeAthrongla Sangtam,Public ProgrammeSupport StaffSanthilatha S. KumarDhan Bahadur RanaV. ThennarsuC. KannanRegional Resource PersonsV. JayarajanMoji RibaK.V.S.L. NarasamambaNima S. GadhiaParag M. SarmaSanat Kumar MitraSatyabrata GhoshShikha JhinganSusmita PoddarM.N. Venkatesha○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<strong>IN</strong>DIAN FOLKLIFE - EDITORIAL TEAMM.D. Muthukumaraswamy, EditorN. Venugopalan, Associate EditorRanjan De, Designer○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○<strong>IN</strong>DIAN FOLKLIFEThe focus of April special issue is on NFSC’s Jaisalmerworkshop on Documenting Creative Processes of Folklore,held at Hotel Dhola Maru, Jaisalmer, from February 5 –19, 2001. We acknowledge our gratitude to Mrs. VidyaSigamany (vidyasigamany@eth.net) for patiently anddiligently transcribing audio recordings of the workshop.We invite submissions of articles, illustrations, reports,reviews offering historical, fieldwork oriented, articlesin English on works in other languages, multidisciplinaryand cultural approaches to folklore. Articlesshould confirm to the latest edition of MLA style manual.Cover Illustration:Zakhar Khan in different poses playing KamaichaBack Cover Photo Courtesy: L.N.KhatriBOARD <strong>OF</strong> TRUSTEESAshoke ChatterjeeB-1002, Rushin Tower, Behind Someshwar 2, Satellite Road, AhmedabadN. Bhakthavathsala ReddyDean, School of Folk and Tribal lore, WarangalBirendranath DattaChandrabrala Borroah Road, Shilpakhuri, GuwahatiDadi D. PudumjeeB2/2211 Vasant Kunj, New DelhiDeborah ThiagarajanPresident, Madras Craft Foundation, ChennaiJyotindra JainSenior Director, Crafts Museum, New DelhiKomal KothariChairman, NFSC.Director, Rupayan Sansthan,Folklore Institute of Rajasthan,Jodhpur,RajasthanMunira SenExecutive Director, Madhyam,BangaloreM.D.MuthukumaraswamyExecutive Trustee and Director, NFSC, ChennaiK. RamadasDeputy Director,Regional Resources Centre for Folk Performing Arts, UdupiP. SubramaniyamDirector, Centre for Development Research and Training, ChennaiY. A. Sudhakar ReddyReader, Centre for Folk Culture Studies, S. N. School, HyderabadVeenapani ChawlaDirector, Adishakti Laboratory for Theater Research, Pondicherryhttp://www.indianfolklore.orgNEXT ISSUETheme for the July issue would be Religion, Folklore andFolklife. Closing date for submission of articles for thenext issue is June 15, 2001. All Communications shouldbe addressed to:The Associate Editor, Indian Folklife, <strong>National</strong> FolkloreSupport Centre, No: 7, Fifth Cross Street,Rajalakshmi Nagar,Velachery, Chennai - 600 042. Ph: 044-2448589, Telefax: 044-2450553, email: venu@indianfolklore.orgOn SyncretismApril, 2000On City Landscapesand FolkloreJuly, 2000On Ecological Citizenship, LocalKnowledge and FolklifeOctober, 2000On Arts, Craftsand FolklifeJanuary, 2001<strong>IN</strong>DIAN FOLKLIFE VOLUME 1 ISSUE 5 APRIL 2001

EDITORIALAll of them vigorously participated in the discussionsand enriched the learning process enormously.Reflecting back I am inclined to think that Jaisalmeritself contributed to the spirit and dynamism of theworkshop. As the westernmost town inside India’sborder Jaisalmer has an extraordinarily medieval andMiddle Eastern feel, with its crenulated goldensandstone walls and narrow streets lined withexquisitely carved buildings. With four major gatewaysto the town and founded by Prince Jaisal in 1156,Jaisalmer grew to be a major staging post on the famoussilk route. On the roughly triangular shaped Trikuta hill,the Golden Fort (called so because of the colour of thesandstone) stands 76 meters above the town enclosedby a 9-meter wall with 99 bastions. When you walkthrough the narrow streets within the fort you oftenget blocked by an odd goat, cow or a camel cart and itof lack of rain. He shared with us a wealth of informationon how the desert supports a variety of plant, animaland bird lives. After his lecture it was very easy toperceive hardships of living in the desert as well as toappreciate human ingenuity in the built water ways andconservation systems (in Khuldara villages), artificiallakes, city plans, food habits, cow and camel herding,grass growing and indigenous medicinal systems.Komal Kothari has been presenting this perceptionabout Rajasthani life all through out the workshopthrough innumerable instances and living in Jaisalmerfor fifteen days made us realise that folklore studies gobeyond studies of expressive behaviour to gain insightsinto life situations. Folklore as a discipline holds a visionof human life in existential terms beyond the corridorsof power and it is important to maintain that visionwhile addressing the questions of art and creativity also.Function for distributing musicalinstruments to young folkmusicians of Rajasthan4is amazing to see even today how about a 1000 turbanclad men, veiled but bejewelled women and schoolgoing children live in tiny houses inside the fort oftenwith beautiful carvings on doors and balconies. Througha mere walk through the town you meet with musicians,puppeteers, weavers, jewellers, potters, toy makers andironsmiths. With an abandoned aircraft kept as a publicmuseum piece on a roadside park with a piles of potson the opposite side, the puppeteers dwellings twostreets away, havelis with their beautifully carved facades,jali screens and oriel windows visible at the other endof street, the camel carts pushing their way throughand the fort in the background when you sip a cup oftea at the roadside shop you tend to think Jaisalmerdefies time.It was astounding to learn from Ramsingh Mertia’slecture that the entire Thar Desert must have beenunderneath the sea ages ago and the desert was a resultThe same vision made us understand that while desertis both a metaphor and reality Rajasthani folk music isnot only an artistic expression but also more of anexistential necessity. It was not at all difficult for us tosee why music and so Sarangi and Kamaicha are centralto Rajasthani folk life. It was not at all difficult for us tounderstand why Komal Kothari was lamenting thatthese two musical instruments had not been made inthe last one century. I am most grateful and mostdelighted that the board of <strong>National</strong> Folklore SupportCentre and the Ford Foundation approved making ofthese two musical instruments with the little excessmoney we had for the workshops and distribution ofthem to the child musicians of traditional communities.The making of these musical instruments was not aseasy as it appeared to be. Despite Komal Kothari’s fourdecades of research in musicology and easy access totraditional communities it was difficult to make theinstruments as it called for knowledge of the woods<strong>IN</strong>DIAN FOLKLIFE VOLUME 1 ISSUE 5 APRIL 2001

EDITORIAL / <strong>IN</strong> A TIME WARPand carpentry skills apart from a collaboration betweenfolklorist, carpenter and traditional musicians. Thestrenuous and adventurous collaboration headed byKomal Kothari lasted for several months and just beforethe workshop they were able to complete only sevensarangies and three kamaichas. As I am writing these linesthe project is still going on to achieve the target of onehundred instruments.What a grand finale the distribution ceremony turnedout to be! All the musicians, who were performing allthese days for us either at Hotel Dhola Maru or in thevillages, were all present. By then we had realised thatZakar Khan, Anwar, Barkat, Gazi, Sagar, Ghewar,Perupa, Buchi, Mehra, Mayat and Gazi Barner were allworld-class musicians. The scintillating performance ofthe child musicians, Yassin, Mehboob, Abdul Rashid,Sikander, Kutla, Shankara, kheta, Darra and Roshanwas lingering in the memory.We were remembering the haunting voice of RukmaDevi, Kherati Ram Bhatt’s skillful puppetry, Kalveliadance of Sukmi Devi, Teratali dance of Chanda, Kamala,Rukmani and Gazi Khan’s institute of music in the villageof Bharna. In the midst of a sudden avalanche ofpowerful evocations, Sharada Ramanathan of the FordFoundation began distributing musical instruments tothe child musicians. They were historic moments filledwith unknown emotions and sentiments. Those werethe moments one normally feels contentment, fulfilmentand satisfaction.My colleagues, Athrongla, Jasmine, Murugan and Venujoin me in thanking the Ford Foundation, the facultymembers, the participants, all the artists (includingB.D.Soni, the jeweller), Kuldeep Kothari and the staffof Rupayan Sansthan our collaborative partner for thisworkshop, Naval Kishore Sharma of Jaisalmer museum,Rajasthani Patrika which carried the news of theworkshop everyday, Major General Bhandari, his familyand the staff of hotel Dhola Maru and the administrativestaff of NFSC who stayed back home to give usbackground support.We are especially grateful to GowherRizvi, Representative of the FordFoundation’s New Delhi office withoutwhose help we would not haveidentified three participants from otherAsian countries and expanded the scopeof this workshop. Although I feel thesense of an ending for this introductoryessay, I do not have the satisfaction ofhaving said everything. Let me say inexasperation: O Jaisalmer!○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○In a time warpKamaicha5Henry GlassieThe musical instruments that are lined on the table today set the mood. The mood is one of transfer,of making it possible for people to continue to do what it is that they wish to do. We should have no desire tomake people continue to do what they don’t wish but if musicians want to make music, if they want to celebratethe universe through sound then we should make it possible for them. Our giving musical instruments to thenext generation, allowing that generation to accomplish its own world in its own way, today establish the mood.So think of those musical instruments as the proper metaphor for everything that’s happened in this workshop.This is the moment of conclusion, it’s a moment of transfer, it’s a moment of gift; it’s a moment when anothergeneration rises to receive, rises to go forward, rises to make possible the continuity of culture. So just as we aremaking it possible for a group of young musicians, by the possession of musical instruments, to carry forward thebeautiful, astonishing and deep music of Rajasthan, so too has this workshop worked in exactly the same way.The idea being a group of elders transfering to a new generation a hope for possibility for a new idea of folkloreresearch; and so just as the musicians will be able to make such music as they want, we hope we who have beenteaching in this workshop that we have transferred to you the instruments with which you can make the musicthat you choose to make, not it is to be hoped the music that we made, but better and more beautiful music.But at the core of that act of transfer there is the hope for a kind of continuity, a kindof continuity that can be expressed in this very simple way–echoing in reverse, aspoint of complexity. And that it’s what could be simpler and what at the same timemore complex than the idea of folklore. I would say that the idea of folklore isnothing more or less than this – it is that time when a human being elects to act withsincerity, nothing more. Meaning that a human being will inevitably work towardsthe expression of the self, will work towards the preservation of the society, willwork towards the preservation of the world, and will work towards honouringwhatever sense of the transcendent visits that individual…(these excerpts were takenfrom Henry Glassie’s concluding remarks…Editor)<strong>IN</strong>DIAN FOLKLIFE VOLUME 1 ISSUE 5 APRIL 2001Henry Glassie

DESERT VOICESDocumenting creative processes of folklore: desert voicesWelcome address: Komal Kothari6It is a big opportunity for me to welcomeArunaji, Henry Glassie, Lee Haring, Pravinaji and allother friends who have come over from all parts of thecountry and a few of them from outside the countryalso. It was in Shillong a year back that a workshop onFrom Fieldwork to Public Domain was held and it wasdecided at that point that next time we would meet inJaisalmer. It was something, which we were doing inShillong, was totally east and now what we are trying todo is totally west. What we were doing in the hills, nowwe will be doing the same type of exercise in the desert.So, this type of a workshop is practically to conceive asort of an in-house, in-depth discussion about thepossibilities folklore presents to human society. We willbe here for another two weeks and will try to come incontact with people who are involved in creating lot ofartefacts, lot of life objects, lot of life material throughwhich they pass and we will try to look into it and thatwill give us opportunity to go among the people, staywith them, try to understand them, try to understandtheir creative processes as that is what is required.We would welcome people from Jaisalmer who wouldbe ready to exchange or know about the processes withwhich the folklore discipline is attached in one way orthe other. They are welcome to join us at any particularmoment. But let me hope that I should be able to takelot more time later on and I welcome you all and it is agreat opportunity to have met here in the desert, whichas you see, has its own silence but silences also have lotof meaning. Let us try to get the meaning out of silence.Thank you.Chief guest address: Aruna RoyI would like to thank NFSC and the Rupayan Sansthanfor inviting me today. I am particularly glad to be withKomalda, we all affectionately call Komal Kothari,Komalda or Komal kaka in Rajasthan depending onour ages. It has always been a privilege to be whereverKomalda has worked, in whatever form. He has alwaysbeen with us whether we have worked with politicalactivism, with social activism, with folklore, with folkmusicians or getting folk people together. He has alwayshad a great sympathy for people who struggle againstoppression, who struggle for justice. So I feel privilegedto be with you all here today and honoured thatKomalda has thought me good enough to inauguratethis session. So I would like to, with all my humility,say that I come here to share my thoughts, not withthe arrogance that they may be right ones, but feelingthat I owe a great debt of gratitude to Komalda and hisvarious folk artists and friends who have always foundtime for us. So I think it is necessary in this world tofind time to communicate with each other from ourvery different worlds.I work with an organisation that is extremely small,which is based in central Rajasthan called the MazdoorKisan Shakthi Sanghatan. It is a small organisation, whichis a non-party people’s organisation. In India today,because all systems have failed us, whether it is thepolitical system of parties or whether it is the system oftrade unions, for poor unorganised people living in thevillages of Rajasthan and elsewhere in India, we feel itis extremely important to understand that in democracypolitics is everybody’s business; to re-shape democracy,to make it our democracy, make it participatorydemocracy and make it something that will fulfil ourdreams, our needs and our vision.It is true that we in our specialisations have differentareas of interests–some look at folklore, some look atfolk tradition, and people like me who work with ruralpeople have, in a certain sense, to look at themholistically, though I may have to concentrate on theirparticipation in political processes, to see that they havemore power to decide for themselves what kind of worldthey want to live in. And I think if we look at the earthand its enormous resources and the way it is goingtoday, and the way people’s initiative, small processes,small groups of traditions that exist, are all beingsteamrolled into one standard uniform culture, thenwe are all important in our different ways, to see thatall these individual small traditions exist, and they notonly exist but have a right to exist. And in that right toexist they make their expression an important form ofexpression to communicate, to entertain, to teach andalso to form a big political statement on the need forexistence of sub-cultures.We cannot have one uniform culture all over the world.We have institutions in India, which are specialisedinstitutions for higher culture, which exist, but I do notthink that there are many institutions in this country,which exist for the smaller cultural groups. Rupayanhas made a substantial difference to this perception. Ifyou look at the crafts, if you look at singing traditions,if you look at creative traditions in India, we could seethey have been expressions from people whom we callDalits, whom we call Dastakars, whom we call the lowerstrata of our caste-ridden society. It has been importanttherefore to not only look at the expression of thesevarious communities but also to give them some placein our social fabric, to give them some importance, toalso accept that they have a right to live other than theexpression of their medium.<strong>IN</strong>DIAN FOLKLIFE VOLUME 1 ISSUE 5 APRIL 2001

DESERT VOICESI do not know how many of you are familiar, who havecome from abroad, but those of us who live in thiscountry well know that when the performance takesplace we accept, for that particular moment, the equalityof the performer with us, but when it comes to feeding,when it comes to living, we always differentiate betweenourselves and them. One of the fundamental thingsthat the Rupayan Sansthan has done is to break thosedifferences. And I think it is a major contribution thatit has made to our lives in Rajasthan.In India, we have a country divided by many things,we are divided by language, we are divided by tradition,different kinds of tradition, different kinds of culturalpatterns and though in a sense we are one country, itis these differences that make this country really a richtradition, a rich heritage, a rich cultural texture. Thereare attempts today, even from amongst us, to make usa uniform whole. Politically we talk of one Hinduatva,of one Hindu party. It is wrong, in my opinion, to talkabout culture in those terms. I think in the course ofthe fifteen days that you will meet here you will seeand understand the kinds of different textures anddifferent kinds of cultural forms that exist. But I willmake a plea and the plea that I will make for you and Iknow that you are interested but I would still like tomake a plea that in our work I have found when wetalk about political alternatives today in this country oralternatives of social reform, I find that the middle classis really pulverised.We damn the whole lot as illiterate, we damn them asnon-creative, we damn them as people who do not knowanything, and I think we do the greatest harm to themand to ourselves.The oral tradition that exists in Rajasthan, I am sure itexists in all parts of India, has contributed enormouslyto our understanding of us, to the understanding oftradition and to the understanding of knowledge.Though I extol tradition as extremely important, I wouldalso like to bring to bear upon us the negatives oftradition. In Rajasthan, we have also seen a womanburnt at the stake not very long ago with her husband’sbody in a funeral pyre when the Roop Kanwar’s Satitook place. We also see all kinds of atrocities on womenin the name of tradition. I am not saying that tradition,in and of it, is wonderful. I am saying tradition is amixed bag, just as development and modernisation is amixed bag, so one is not talking of one versus the other,one is talking of preserving those forms of traditionand those forms of modernisation which are for socialjustice and equality, which also perpetuate culture inthe form that we want to define it. I am not willing,and I am sure most of you are not willing; to let theelectronic media or newspapers that are now in thehands of multinational corporations define what cultureshould be. I think we have a right as people in a livingsociety to define what culture we need to subscribeand I will be very interested to know what comes outas a result of your fifteen days’ deliberation on it.7I think no great major ideas have emerged from themiddle class in the last 50 years. They have only rehashedvarious things. If you look at the political status of Indiatoday, I do not think we can claim any great contributionto the nature of politics or the nature of economics ofthis country. It is important at this juncture, for peoplelike me and many of my friends in this country, to lookat and understand the nature of knowledge that existsamongst people whom we dismiss generally as illiterate.I think though literacy is an extremely important tool fordevelopment, it is a toolwhich is important, for it isa living skill and here comemy friends who are thegreatest of performers, whomay be illiterate, but who intheir performance, in theirknowledge of musical notes,in their knowledge ofvarious things, have thegreatest understanding ofmathematics in theunderstanding of beats, they have theunderstanding of rhythm which originates froman understanding of timing, which originatesin mathematics. We have the most marvellousweavers in this country who weave the mostexquisite fabrics in which the precisionin terms of mathematical calculation exist.Pravina Shukla: Keynote addressInaugural functionI have just come back from Brazil and where, WorldSocial Forum held an alternative social summit to theeconomic summit held at Davos. In Davos, the WTOmet to see how the world could be standardised, howeverything could be under the normative pattern of onegroup of people who decide how the world will workeconomically. As an alternative, the World Social Forumwhich organised itself in Brazil invited people who arenot in the mainstream of decision-making today butwho are the large majority of this earth’s population.The meeting discussed what kind of<strong>IN</strong>DIAN FOLKLIFE VOLUME 1 ISSUE 5 APRIL 2001alternative modes could prevail in theworld to decide and protest against thestandardisation and steamrolling ofeconomics and of culture. If you lookat the way multinationals are comingin, it will not only be in the selling ofsoap and the selling of tea and theselling of goods, it will also be in whatwe will read in thenewspapers, what we willread in magazines, what willbe shown on the television,and its going to be a bigstruggle for all of us whosupport the marginalized, socalledmarginalized groups ofpeople, whether it is thepeasant or whether it is the

DESERT VOICES8folklorist, whether it is the singer, whether it is theperformer, against this massive inroad and the amountof money that is being spent on it is colossal. But wepeople who are on the other side have one greatadvantage and that is the numbers that we are. We areenormous numbers of people and they are very few ifyou look at the comparison in terms of numbers.The problem is that in India, and I am sure in the restof the world but I only know India well, the peoplewho protest are few, the people who promote thosethings are also few, the large numbers of us do not sayanything, we keep quiet. Here in Rajasthan, there is afavourite phrase, whenever I went to the village andtalked about things which were community properties,which were community heritages, which werecommunity things, there was a famous saying especiallyin economic terms when you talk about governmentspending, they used to say badhbadoji, badhbado, marutho ko na - it isn’t mine, let it burn. I do not think I willtake much time but I will just mention it because that isthe reason why I am here with you all today, and ourcampaign for right to information and transparency ofgovernment funds and of all people dealing with publicmoney has now become a national issue.It is one way in which we can make the governmentaccountable to its people and we can make the peopleresponsible for political action in a democracy. In ademocracy people cannot just cast a vote and say thatthe five years between one vote and the next is theresponsibility of the politician we sent to power andthe bureaucrat who looks after us. We have realisedthat in a democracy if we want real power, we will haveto speak, we will have to monitor. We will have tohave continuing accountability of the government tous. We have to make the people’s voice stronger. Icome to you with a final plea that ethics whether it is inthe business of public life and politics or ethics in thequestion of cultural choices is not in the depiction orjust in the mode of depiction or the purity of thedepiction of a certain form.Many years ago, I had the good fortune to study danceat Kalakshetra in Madras, and I know what it means tohave a purist form because in the school that I studiedin, we were not even allowed to see performances ofBharatanatyam by people who are not considered puredancers. And the people who came and taught us thedance form were in the pure tradition, in which therewas no interpolations of any cinematic mode, of anymodern mode but came in the true tradition of whatthe Bharatanatyam system was. We did not hear anyclassical music in which there was any infiltration ofany other thing. I am not talking of purism, which initself has its own value. I am talking about ethics of thepeople who perform. I think the lives of those people,the kind of life they lead economically, and the kind oflife they lead socially are as important as the forms thatthey project.I will just end with a simple quotation not from one ofthe great people in the world we know but from LalSingh who is a comrade and a friend of mine, whoworks with the Mazdoor Kisan Shakthi Sanghatan. Sowhen we were invited to speak in an institution in Jaipurwhich organises training for people in the civil service,they invited me and they invited another person whois also bilingual, both English and Hindi speaking, andwe took with us three farmers and workers. After all,my organisation translates into a workers’ and peasants’organisation and I am neither a worker nor a peasant.So they thought that Lal Singh had just come as a sortof a totem to say that, you know, there are peasants andworkers we work with. As usual, they gave me fifteenminutes to speak but they said to me at three minutesthat time was up. So Lal Singh said to them he neededonly one minute.When Lal Singhji was given that one minute to talk,three minutes to talk, he said I would speak in oneminute, that’s all I need. And what he put succinctlyin that one minute, it will take me half-an-hour to explainwith all my verbosity. So like all other cultural folklorists,our peasants are also people who are gifted with thegift of language, of thought and I will translate what hesaid in Hindi. With all these to-be bureaucrats andcivil servants sitting in front of him, he said to them; wewonder if we do not have the right to information andtransparency whether we poor will exist in India at all. Youas people who are going to sit and rule over us as a state, youwonder if you give the right to information, whether you willbe in control or not, whether you will sit on that chair or notliterally, because your power will be distributed, because onceyou share information, you share power and you will loseyour seat and your control over power. But actually what weshould all do is to collectively think whether the country willexist or not exist if there is no transparency or right toinformation, if there is no ethics in public life. So, friends,I come to you with all humility to share the fewthoughts. Thank you.Keynote address: Henry GlassieIt is a great delight for me to be here. I have spentmany years of research in Bangladesh, visited Pakistan,toured in Tamil Nadu, this is my very first visit to northIndia, therefore I pretend no expertise, I know nothingat all about your place, I come here humbly to learnfrom you. Not to teach but to learn. I need, inexpressing my delight, to thank a friend who have mademy visit possible. In M. D. Muthukumarasamy, an oldand dear friend, a great folklorist, a man with whom Ifeel great kinship and who have made this conferencepossible. We need to remember Sharada Ramanathanof the Ford Foundation in Delhi who has providedsupport to NFSC. I consider it a great honour to behere with my colleagues, the great Komal Kothari andmy colleagues from America, my old, close belovedfriend Lee Haring and Pravina Shukla who teaches withme at Indiana University.<strong>IN</strong>DIAN FOLKLIFE VOLUME 1 ISSUE 5 APRIL 2001

DESERT VOICESI come in the very beginning to make a fairly simple setof propositions. Here is the first one: I teach you alittle bit about the history of our discipline. We can divideits history into three great phases. The first one is theEuropean phase. In the European phase, folkloristswere primarily interested in history. Their eyes wereturned backward, they were concerned with distanttimes, distant places, the movement of ideas, and themovement of peoples and as they looked backward,they first discovered something about their nationalheritage. But the more the folklorists concentrated ontheir national heritage, the more the Germans wereinterested in Germany, the more that the Irish wereinterested in Ireland, the Italians in Italy, they began todiscover the proposition of the international. They losttheir concern with nationaldestiny and began to think,however humbly, howevercrudely, and from whateversuperior perspective thatthey adopted, they began tothink about an internationalview, an international viewthat through various seriousresearch ultimately broughtthe folklorists into anunderstanding of one greatland mass that lay on the west in Irelandand on the east in India and the greatThomson in his day titled the mostimportant chapter of the most importantbook, From India to Ireland. Note the wayin which the folklorist’s interest in theorigins of folklore in India that then movedwestward was precisely counter to all theforces of colonialism. The forces ofcolonialism were suggesting that all ideaswere moving from Europe to Asia; theAruna Roy: Chief GuestKomalda: Welcomeaddressfolklorist was arguing that all the great ideas had in factmoved from Asia to Europe.Humble, small, marginal, of no great importance, thelittle discipline of folklore took as its task, from the veryinception, to countering the proposition of colonialismby arguing in behalf of the world moving against thesun and all of the ideas moving with the course of theuniverse from east to west. In its first days, its Europeancentury, folklore was primarily concerned with the pastand as it was concerned with the past, it was primarilyconcerned with the reconstruction of a history thatwould be for modern people a better, more democratic,more comprehensive history than the history that waswritten in history books. It started this discipline offolklore in pure opposition to the force of history, theforce of history being that force that supported colonialendeavours, that supported oppression, that supporteddivision, that attempted to work against the entirenotion of democracy. In its first century, folklore wascommitted to an understanding from the past aboutpossibilities of a democratic future.In its second century, folklore shifted from Europe tothe United States, and in shifting from Europe to theUnited States folklore began to be concerned not somuch with the past as with the present. As itreconstructed itself as a view of the present, folklorelost the value structures that had committed folklore toa countering of colonialism; it began to look at thepossibilities of a universe made up of equal civilisations,of equal cultures, of cultures each of them with theirintegrity, of cultures each of them with their power, ofcultures each of them with their beauty. Folklore thenbecame the celebration of the integrity of distinctcultures, the ways in which small groups of people hadthrough speaking well, through making well, throughthinking well, had constructed for themselves ways oflife that answered their needs, that fit their ecology,that fit their hopes for the future. In a sense, in itssecond century, its American century, folklore devaluedvalues, deconstructed historical propositions and movedtowards the notion of a universe made up of separatesocieties, each with its own integrity, and each with itsown purpose.We are, you and I, involved in a very powerfulhistoric process because we are at the verydawn of folklore’s third century. Its first centurywas a century of Europe and history; it was acentury of looking backward in order toreconstitute a history that could be useful forthe future. In its second century, its Americancentury, folklore is primarily oriented to thepresent, looking out uponthe present and fragmentingthe globe into a thousand,thousand small societies,each of them with theirLee Haring: Keynoteaddressbeauty. We are nowstanding at the verybeginning of folklore’s thirdcentury, which will be notits European, not itsAmerican century but itsAsian century. We are at thevery dawn of folklore’s Asiancentury and folklore’s Asian century will not be a centurythat orients to the past, it will not be a century thatorients to the present, it will be a century that orientsitself to the future, that begins to look forward and toimagine how all of that learning that we have developedabout history, all of that learning that we have developedabout culture can be put into action. No longer will wesuspend judgement; we will be obliged to makejudgements. No longer will we be involved in pureresearch, we will be involved in impure research andimpure research that allows us to rethink the entireproposition of scholarship, the entire proposition ofscience and allows us to realise that what we should bedoing is putting into play, applying, ameliorating,making the world better for the world’s people by usingpure research to develop means by which we can9<strong>IN</strong>DIAN FOLKLIFE VOLUME 1 ISSUE 5 APRIL 2001

DESERT VOICES10improve the lot, not only of the poor, but of the rich,the way that we can improve the lot of all the peoplewho live on the world.During its American century what folklorists did wasto dismantle the value structures by which history wasconstructed and attempt to eliminate values on behalfof equality. What I would like is to think about it assomething beyond equality, beyond somethingegalitarian, something that might even propose thefrightening notion of a new aristocracy, a newaristocracy of the mind, of the heart, of the soul, a newaristocracy that might allow in its Asian century forfolklorists to solve the problems that the West has notsolved – the problem of gender, the problem of class,these are the problems that lie before us; we have failed,it is my hope that with God’s power that you willsucceed. So my mission in coming to you is to help thetransition from the century of America to the centuryof Asia. And in this mission what I imagine is a changein folklore, a change in folklore as you just heard thenotion that we might reshape democracy, I wouldimagine us reshaping the entire proposition of ideologyand in that reshaping what it is my hope that can happenis that Asian scholars who receive from western scholarsall of those things that westerners have learnt and thennot only adjust those things to a new territory butcompletely rebuild the discipline of folklore. I am hereto give you the discipline of folklore with my blessingand my hope that you will do a better job with it thanwe did. We brought it to a certain point but at thispoint we in the West have failed.My first statement of my mission is that what I am hereto do is to learn from you and to hand to you all of thatwhich is of value in the discipline of folklore so thatyou can reconstruct the discipline and not only make itfit for Asia but so that Asians can now begin to lead theentire world, to do folklore better than we did folklore,to do better than the Europeans did folklore, to takefolklore to new glorious heights in which pure researchwill be dedicated not merely to the accumulation ofknowledge, but pure research will be dedicated to thesolving of serious problems. There are serious problemsthat lie before us and the folklore can be the very means,it being so crucial to the way human beings constructtheir lives, the folklore can be the very means by whichyou construct a new discipline and you can, I wish,you can lead the world better than we have. Americapresumptuously calls itself the most powerful nationon the face of the earth; I see America as a great giantthat does not know yet that it is dead. It is still stumblingaround on the face of the earth as though it had energy.America’s energy lies entirely in the past; Europe’senergy is not even a dream in the mind of a dying soul.The whole hope of the future, in my opinion, lies withyou in Asia. I am very delighted to be able to; I wish tosurrender to you such virtue as remains in the disciplineof folklore. My first mission is to give you folklore andmy second mission is to follow you into the future, notto lead you but to follow you. My third mission is tohope that with you we can dismantle this monstrousneo-colonial proposition called globalisation;globalisation that can seem like a positive force,globalisation which is nothing but colonialism in a wholenew, more insidious guise. What I would like to do isto say to you first of all, as an American, for heaven’ssake, do not follow America. For heaven’s sake, pleasebegin to lead America. America needs your directionand folklore needs your direction too.What we need to do is to work against the propositionof globalisation on behalf of freedom, on behalf ofjustice. Folklore is not marginal to those endeavours.Our understanding of folklore is absolutely dead centralto those endeavours; there will be no possibility for usunderstanding the world unless we study closely, soclosely the people who have mastered tradition, thatwe do not consider those people to be our equals butwe humbly accept those people to be our superiors andat last we learn to follow them and their wisdom intothe future. I am, I repeat, delighted to be here. I amlooking forward to these two weeks with you; I amexcited in the ways in which I will be able to learn fromyou but more importantly what I would like us to do isto be able to develop between ourselves, amongourselves with all the powers that lie behind us in ourcivilisations, to be able to develop for the world a bettermodel of what the future can be like. The Europeancentury was about history and the past, the Americancentury was about the present, the Asian century willbe about the future and whether the future will be betterthan the past is largely up to you. I say at the end ofthis little rant that I am perfectly happy, delighted tobe following you into the future, pleased to be here, Ithank my friends.Keynote address: Lee HaringDear colleagues and members of the workshop, I takea moment now to express to you my immense gratitudefor the invitation to me to travel here to Rajasthan andto be among you for the two weeks in this workshop.It was a year ago that I was privileged to attend theTwentieth Indian Folklore Congress held at Patiala.There I met many Indian folklorists and was impressedby the great importance that the study of folklore holdsin the past and present and future, as my dear friendHenry Glassie has said, of this great country. It was anAmerican anthropologist, Milton Singer, who pointedout, almost fifty years ago, India’s strong interest in therecovery or reinterpretation of India’s traditional culture.Singer also gave us this challenge, I quote, and theprofessional student of culture and civilization may contributesomething to this inquiry through an objective study of thevariety and changes in cultural traditions. That is thecontribution we all hope to make through thisworkshop.<strong>IN</strong>DIAN FOLKLIFE VOLUME 1 ISSUE 5 APRIL 2001

DESERT VOICESWriting about African-American blue songs, the greatnovelist Rod Ellison remarked that any viable theoryabout part of a culture obligates us to fashion a moreadequate theory of the whole of that culture. Blues, hewrote, cannot be isolated from other kinds of music,whether African-American or other, cannot be isolatedfrom other kinds of American expression or other partsof American culture. Ellison’s logic if we take it to aglobal scale implies the reverse as well. Any viabletheory of world culture in our time obligates us toassemble facts about local cultures, more facts indeedthan globalisation theorists usually acknowledge.Folklorists are uniquely positioned to direct attentionto local cultural situations. And that is a large part ofour study in this workshop – identifying the new genres,tools and insights that arise in the studies, the centraltask of folklore is to take its place where it belongs atthe centre of the human sciences. I am glad to be withyou as a new millennium begins. Last year, manypeople celebrated an ending as though it were a newbeginning. But new beginnings are always possible forus. I try to start over each morning, so I greet you withgratitude and excitement, and I wish all of you, all ofus, a happy and fruitful time of working together.Keynote address: Pravina ShuklaGood Morning. I am going to keep my comments verybrief because you have lots of opportunity to hear metalk in the next two weeks. First of all, I want to thankM.D. Muthukumaraswamy for being here. It is a veryimportant personal pleasure for me to be here in India,participating in this workshop. I am also honoured asa new professor to be in the company of my heroes,people who have proven and inspired me in folklore. Isee my presence here at this folklore conference/workshop as symbolic. I see myself imbibing theconnections between India and America. I am of Indianheritage, my parents are from India; I was born andbrought up abroad; I have done fieldwork in both Indiaand Brazil, where I grew up. So I study both the newworld and the old world, both areas of my background,countries and cultures that make up who I am today. Ithink what we have to do is take the abstract of whatHenry and Lee talked about and make it concrete.We need now, we continue to need, compassionateunderstanding outside those perspectives. Still, we alsoneed perspectives that bridge, a friend of mine justrecently called me, saw me as a bridge between eastand west, between Asia and America or Europe. I thinkwe need the perspectives of the bridge, people who areboth insiders and outsiders simultaneously, which Iconsider myself. And then we need to add theimportant insider’s perspectives to this. That would beyou talking about studying India. All three of theseperspectives are needed for us to come to a betterunderstanding of the dynamics of Indian folklore. I donot think we are using the insider’s perspective, I sayyours, the kind of bridge perspective, I say mine, theoutsider’s perspective, I say theirs. One is not betterthan the other, one is not replacing the other in thischronology of centuries; I think we need all of themsimultaneously. As I hope for the future in makingthis abstract specific, we are currently in the final stagesof developing international folklore connection betweenIndiana University and India. We have Indian scholarsand contemporary folklore theory. Henry Glassie and Iwould be the co-directors of that. This is an officialconnection; in the meantime while this happens wecan engage in all kinds of unofficial connections. It is apleasure to be here, I look forward to getting to knowyou. Thank you.Vote of thanks: M.D. MuthukumaraswamyAruna Roy, the Chief guest of this function, HenryGlassie, Lee Haring, Komal Kothari, Chand, Bhandari,the Director of the Folklore Museum, Jaisalmer, anddistinguished members from Jaisalmer anddistinguished participants, it is my pleasure to thankyou all for coming over here. This has been a verydifficult workshop for us to organise, in the sense thatwe are sitting there in the city of Chennai and then weare organising something in Jaisalmer. This workshopwould not have been happened without thecollaboration of Rupayan Sansthan headed by KomalKothari and his staff. They made all the localarrangements here and we were coordinating betweenthe international faculty, the participants who appliedto us and also with so many other people. One of themajor tragedies that happened on January 26, the IndianRepublic Day, the major earthquake in Gujarat, thatset us really in a bad mood and many participantswondered whether we would be able to hold thisworkshop. The tragedy was colossal and the wholenation went through depression. On TV, the imagesshown were depressing and it was purely because ofthe encouragement I received from Komalda I wentahead with all the preparations. I am also glad for allthe participants who enquired with us whether thisworkshop was to happen in the first place, who believedmy assurances and then came over here.I would like to make a few comments about thisworkshop and its organisation and also thank all thecolleagues who are to participate. We began theplanning for this workshop in December 1999 when Iinvited Glassie to come over for our Shillong workshop.But at that time he could not make it because he hadsome other commitments in Bangladesh and then webegan a conversation about this workshop and purelydue to Glassie’s commitment to the Asian century ofthe future that we were able to put together acurriculum, put together the faculty and I am gratefulto Henry Glassie for being associated with me and thenguiding me for the workshop for nearly one and a halfyears. That kind of a preparation went into this, allthrough emails: of course email is a blessing. Email andinternet have revolutionised information sharing.11<strong>IN</strong>DIAN FOLKLIFE VOLUME 1 ISSUE 5 APRIL 2001

DESERT VOICES12That brings me to the idea Shrimathi Aruna Roy broughtto us today, the right to information, the right to havethe transparency installed in government, nongovernmentand other organisations. <strong>National</strong> FolkloreSupport Centre receives a grant from the FordFoundation. We at NFSC believe that the funds availableto us from the Ford Foundation are public funds. It isa public fund we are handling and NFSC standscommitted to the accountability of receiving publicfunds. At NFSC I strive hard to keep the centre,egalitarian. We have no hierarchy in the organisation;we have only roles to play, and we have only work toaccomplish. And I have distinguished, hard-workingcolleagues with me, Venugopal, Jasmine K. Dharod andAthrongla Sangtam and Murugan. Then we have theblessing of working with the colleagues from RupayanSansthan, Kuldeep Kothari and Rajinder.All of us are participants, we are students of folklore,we are here to learn and as organisers we have secondroles to play. We are here to learn from you and alsolearn from the place, Rajasthan. Another thing I wouldlike to talk about is the kind of faculty we have in thepresence of Lee Haring and Shukla. I entirely agreewith Glassie when he says the future of folklore as adiscipline is in the hands of Asian scholars. I hesitateto say Indian scholars because we planned to have SouthAsian and South-East Asian participants for thisworkshop. Unfortunately when we initially conceivedof this workshop, we conceived of it only as a nationalworkshop. Then we thought we have a largerconnectivity with the South Asian and South-East Asiancountries and we needed participants from there also.But we could not provide them with the travel fundsand Glassie said he would relinquish his travel fundsto give that to candidates from Bangladesh or otherSoutheast Asian countries. We found although we arevery eager for a conversation with our colleagues in theSouth Asian and South-East Asian countries,communications between us are dismal. So givinginformation was difficult, we could get only very fewapplications and once we asked them to come over,they had difficulty finding travel funds. This is one ofthe problem we need to take into consideration inbuilding up an Asian century for folklore. However wewere able to get three scholars, Phuong Lethi fromVietnam, Tulasi Diwasa and Bandhu from Nepal. Thestructure of the curriculum, the course, we thought,should address transnational ways of seeing folklore.Transnational in the sense how cultures mingle andhow cultures offer ways of all the time creating newpossibilities, all the time creating possibilities of genre,possibilities of life forms, possibilities of expression, thepossibilities of wisdom.Without expression, there is no possibility of wisdom.Without wisdom, there is no possibility of learning andwithout learning there is no possibility of building anation of democracy and the nation of democracydepends on learning from the people as we all agreedand then for learning from the people, we need tools,we need theoretical tools, we need people who havestudied them. So we have Lee Haring and PravinaShukla, both of them are experts in studying howcultures mingle and how new possibilities emerge.These are very important to us in the context ofglobalisation as Glassie mentioned, in the context ofgrassroots expression as Aruna Roy mentioned and thenin the context of listening to the silences as KomalKothari mentioned. So along with distinguished facultyI think we also have distinguished participants for thisworkshop; most of them are senior to me in this fieldand I look forward to a great listening and great learningexperience with all of you. We, I hope, to spend fruitfultime here in Rajasthan; let us explore Rajasthani culturealso when we are here for the next fifteen days. Withthat, I thank every one of you, I thank the FordFoundation, I thank my colleagues, I thank mycolleagues at the Rupayan Sansthan, and I thank ourlearned teachers.Workshop Participants and FacultyStanding (from L to R): Murugan, Nima, Geeta, Muthu, Pravina, Lakshmi, Jasmine, Simon, Khubchandani,Kuldeep, Aruna, Jayathirtha, Tulasi Diwasa, Sawai, Phuong Le Thi, N.K. Sharma, Moji RibaSitting (from L to R): Bandhu, Gayatri, Komalda, Munira, Guy, Shikha, Athrongla, Ashok Alva<strong>IN</strong>DIAN FOLKLIFE VOLUME 1 ISSUE 5 APRIL 2001

FIELD VISITS / EVEN<strong>IN</strong>G PERFORMANCESField visitsDatePlace6 February Jaisalmer fort, Jain temples, Haveli sculptures and khadi bhandar8 February Kalakar colony to Kherati Ram Bhatt’s place where the whole process of puppet makingand a puppetry show were performed9 February Folklore museum and Garisar lake11 February Visited Bharna and Gazi Khan’s Institute, listened to folk music concerts, went forcamel safari and visited the sand dunes13 February Visited goldsmith B.D. Soni’s work place and observed the various stagesof making jewellery14 February Visited Hamira village for traditional pottery and later to Gazi, Anwar and Zakar ‘splace where they sang folk songs and visited the traditional fair related tomother goddess Kale Doongri16 February Visited village Khuldara, abandoned villages by Pallival Brahmin community andlater went to the sunset point○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○Evening performancesDate Artists Description Contact Addressof performance13Feb 5 Child Artists: Yassin, Mehboob, C/o Kheta KhanAbdul Rashid, Sikander, Folk Songs Manganiyar,Kutla, Shankara,Village Post Hamira,Kheta, Darra, RoshanDist- Jaisalmer, Rajasthan.Ph: (02992) 51285Feb 7 Rukma Devi Solo artist (song) Payachi, Rajasthan,Near Hotel Dhola Maru,Jaisalmer, RajasthanFeb 7 Kherati Ram Bhatt Puppetry Katputliwala, Houseno. 47, Kalakar colony,Jaisalmer, RajasthanFeb 9 Ghewar, Anwar, Barkat, Gazi Folk Songs Village Hamira,(Hamira)Dist. Jaisalmer, RajasthanFeb 11 Ghazi, Sagar, Perupa, Buchi, Folk songs Village BharnaMehra, Mayat, Anwar, Gazi, (Bharna) Dist. JaisalmerGazi Barner, Satar, BarkatRajasthanFeb 12 Sukmi Devi, Suva Devi, Kalvelia Dance Sheshnath Lok KalakarSatar Khan (Dholak)House no. 55, Sanjay CColony, Pratap Nagar,Jodhpur, RajasthanFeb 13 Anwar, Gazi Bharni, Ghewar, Folk Songs Village Hamira,Barkat Khan, MehraDist. Jaisalmer, RajasthanFeb 14Chanda, Kamala, Narayan Das,Rukmani, Gaffur Teratali Dance Gaon DholTehasil Gokurda,Dist. Udaipur, Rajasthan<strong>IN</strong>DIAN FOLKLIFE VOLUME 1 ISSUE 5 APRIL 2001

FOLKLORE AND CREATIVITYParticipant report: folklore and creativityGuy Poitevin is Director, Centre for Cooperative Researchin Social Sciences, Pune, India14The workshop on documenting creative processesof folklore, was meant to bring together people activelyconcerned with folklore issues in India in order to initiatea process of interaction among them, and as a followupexplore possibilities of cooperation between the<strong>National</strong> Folklore Support Centre (NFSC) and theparticipants, in whatever form and context deemedappropriate to the objectives of NFSC. The deliberatechoice of Jaisalmer is to focus on the culturalpotentialities and artistic capacities of deprivedcommunities and popular performers. To this effect,NFSC intends to cooperate with Indian Universities andsupport folklore researchers.The Far-East regions having been neglected by Indiasince Independence, NFSC purposely organised a firsttraining workshop in Shillong in May 2000 for mid careerIndian folklorists to reflect upon their practice. Thesecond one was decided to be at Jaisalmer with RupayanSansthan. The workshop was organised to offer anopportunity of intense exchange of views andexperiences to selected participants, either in generalsessions through immediately reacting to thepresentations made by the faculty members or in thesmall groups of five which were arranged as their followupand animated by a rotating faculty member. Thesesmall groups were recomposed every five days. Fieldvisits were generally arranged in the afternoons to getacquainted with various facets of folklife and interactwith them in their life environment. Evenings wereearmarked for performances of music, puppetry anddances. The latter again gave opportunities to personallyrelate with the performers and express our appreciationfor an expertise, which often compared with that ofprofessionally trained artists.Guy PoitevinThis report deals withthe general sessionsonly. It does not intendto be an objectiverecapitulation of thelectures made byfaculty members andfollowing generaldebates. The richnessof these lectures anddiscussions would onlymake this taskimpossible. I meansomething else,namely, to point out afew issues, which seemto me particularlyrelevant in the field offolklore studies and practices in India. I intend on theone hand to stress points which should become matterof consensus and be remembered as significantlandmarks for reference by the participants keen onproceeding further along ways chalked out by theworkshop. I shall on the other hand take thisopportunity to occasionally raise critical questions onissues, which in my opinion remain problematic andrequire further consideration.Identification of core issuesThe workshop was meant to possibly identifyprogrammes to be further carried out with NFSCsupport. This implied that basic perspectives be sharedin order to work actively upon whatever be the fieldsof social involvement or the domains of research. Itwas essential to that effect that right at the outset theconcerns and expectations of every one be spelt out inorder to facilitate a broad homogeneity of perspectives.The participants were therefore requested to make ashort self-presentation and state their main fields ofinvolvement or areas of research. This gave an initialidea of what actually folklore means for them, practicallyand theoretically.The concerns of most participants can be categorisedas follows: (1) the publication of articles, documents,books, video-tapes, visual and audio-documents andfilms on folk traditions; (2) the promotion of folk artsand support to performances, sometimes theorganisation of traditional artists’ melas, talks and meets,one of the significant aims of such activities being ofpresenting these living traditions to a large public whichignores or even looks down upon them; (3) thepreservation and reactivation of people’s traditions andknowledge for the next generations at a moment wheretheir survival is problematic, but their heritagesignificantly relevant. The aim of most of the participantsis of strengthening such potentialities, enhancing theirresilience, propounding their social relevance andavailing of them as assets for cultural activities in frontof destructive social challenges.Issues of theoretical concernThe preliminary self-introduction pointed to a fewtheoretical issues bearing on methods, perspectives andthe clarification of which motivated the wish of theparticipants to come and attend the workshop. Theirhope was that workshop would provide fruitful insights.The particular expectation expressed by severalparticipants was of discovering through a direct contactwith the rich Rajasthan folklore especially its music,<strong>IN</strong>DIAN FOLKLIFE VOLUME 1 ISSUE 5 APRIL 2001

FOLKLORE AND CREATIVITYcraft, tales, songs, dances, etc. The holding of theworkshop in Jaisalmer was indeed meant to offer asingular opportunity of personal experience andexposure to Rajasthani folk traditions through directlyrelating with artists and their communities at home inthe course of the field work visits arranged in theafternoon, and evening performances.With Hamira village musiciansWith Hamira village musiciansKherati Ram Bhatt’s homeThe preliminaryquestion raisedby many was:What is folklore?The questionof thetheoreticalstatus offolkloreas aconstituencyo fknowledgeproves a crucialand pervasiveissue, at thecognitive as wellas at thepractical level.Those who tryto enhancethe validityand survivalof oraltraditionsespeciallyin tribalcommunities raisedanother importantissue: What doescreative processmean? Thequestion hasreference tolanguage,social forms,marriagecustoms,tales andmyths,melodicheritage, etc.Aruna Roy and others, not as afact to be deplored but a boon to beworked out, naturally stressed the question ofmultiplicity of cultures alive and vibrant in the wholeIndian subcontinent.Folklore is a matter of speech and not of pure textualtraditions, which possibly exist only as mental fictions.(The word text is being used in this report in the senseit was later defined by the Faculty as a metaphorborrowed from the world of weaving to mean what hasbeen woven together, that is to say, elements thatsomebody puts together as to shape a distinct object).In this regard several questions arise. First, what areorality and its function versus the written? What canpeople’s oral traditions mean in the context of presentday development and in general with reference tocultures and civilisations grounded in the written textwhich use to entertain disregard for the oral texts ofprimitive societies? Secondly, what cognitive status andauthority do we recognise to oral texts when ourdocumentation means and procedures are guided byprinciples and concepts framed by systems ofknowledge based on the predominant authority of thewritten text? In other words, we may try and knowhow to let performers of oral texts speak for themselveswith an authority of their own, but to what extent arewe able to apprehend the logic of their oral regime ofexpressivities? Thirdly, human rights and the rights toinformation were strongly stressed by Aruna Roy andbrought forward time and again by the participants asa core issue directly connected with our interest infolklore. How would we figure out this politicalconnection between peoples’ traditions and democraticrules of social communication?From the outset questions were raised about what do wedo when we document? What is the meaning ofdocumentation? How and why do we document? Thequestion is an ethical one. It bears on the rapportbetween the scholars, the research worker, or, for thatmatter, the activist, and the people with a differentculture and a much lower social status. How would welike to qualify and figure out this rapport? The questionis one of the core issues to be addressed by a workshopon documentation. Why do we collect songs and wishto archive oral traditions? What are our motives? Whatare we looking for? How to secure continuity andsurvival for disappearing traditions (songs, tunes, tales,crafts)? What are the means to preserve them? Whyand how to preserve them when styles of living changedrastically and changes do not care for continuity. Howdo we manage or negotiate such ruptures? What arethe means to reactivate traditions? How can we base onthem processes of cultural action in the modern context?How do we concretely figure out the continuity or oftradition and modernity in the case of folk-tales, songs,myths, music, etc? How do they enter in and berepresented by our modern discourses? Traditionalsocieties are swept away off their social and culturalmoorings (family customs, ways of living, culturalwealth, occupational skills, etc.). How can we reactivatea collective cultural memory found fading away, andsave its relevance, if any, and, if so, which one, in amodern environment, to the benefit of the overall polityand culture of India to-day? Are we only enjoying arole of mourners with no other purpose than thedubious pleasure of an aesthetic contemplation of thebeauty of the dead?15<strong>IN</strong>DIAN FOLKLIFE VOLUME 1 ISSUE 5 APRIL 2001

FOLKLORE AND CREATIVITY16Cultural memory may draw upon the inner dynamicsof old folk forms and incorporate their semantics andvalues in a new life style, in different systems of socialrelations. Why should we not even continue using oldinstruments and react against their falling out of use?A mental shift is needed to prompt new people to adjustto old instruments on account of their musical potentials.Why not create this opportunity and device a new leaseof life for them in our times? remarked Komal Kothari.From the outset, a kind of principle for action wasstressed, namely, that at a time when many traditionalforms are disappearing, these forms should be carefullydocumented and systematically studied for whateverthey are worth for (social form, musical tune, myth,tale, etc.). Save one percent in your budget for pure folkstudies is the motto and request of Komal Kothari to allsocial action groups. But how to solve such difficultiesas the availability of time and funds, have concernedand competent people, of means and methods?Then how to do good work and do justice to thetraditions themselves? This applies to musicalknowledge as well as to mythological logic. This impliesfirstly that forms be studied in their whole humancontext, not as isolated folklore item. There is no morepure music or pure technical craftsmanship withoutconcrete human social communication, humanexpression and as a consequence constant variation arethe three characteristic modes of living oral traditions.Pure excellence is always defined out of context. Folktraditions have their own life; they constantly changeaccording to time and historical transformations. Theyare never fixed and isolated objects. They are historicallyconditioned inventions. The workshop was preciselymeant to examine ways and methods of documentingthe particularly significant dimension of creativity ofpeople’s traditions.Careers and concernsUnder this title faculty members shared introspectivereflections about their individual journey as folkloristsso that the lessons that they drew from their professionalcareer may help us to avoid dead ends and suggest away to us. Lee Haring was initially a performer of banjoand singer of traditional American songs. He realisedlater on that songs were coming from country people whomI had no connection with. We had no concern for their context.We were selling ourselves as guardians of authentic Americansongs taken often from commercial productions. A secondlesson is the discovery of the importance of music inthe European songs that his students, sons of migrants,were learning at home as part of their culture. Whenfolklore became a reality in the North America in the60s, another discovery was the retrieval and theinvestigation of the text as a form of creative process.In Kenya, in India and in Madagascar, I discoveredcomplicity between the ignorance of their folklore by peopleand European colonialism. Their folklore became less isolatedand ultimately appeared to me as equivalent to people’s culture,and culture equivalent to history. Folklore studies becamethen a way to acquaint people with their own heritage.Ultimately, ethnicity and nationalism appeared to me narrowapproaches, if not altogether wrong perspectives. Notions ofendangered species and pure forms were also discarded asmisleading, as there is only mixture, métissage, diversityand hybrids. This would apply to situation in the USA also,confirmed Lee Haring in reply to a question. There is ahistory of the concept of folklore in the USA as well,with the same need to transcend concepts of ethnicity,otherness, purity, and nation.Pravina Shukla reflected upon her professionalexperience as folklorist in Brazil (carnival), Benares(women’s practices of body adornment) and inorganising exhibitions and museums in the USA (seePravina Shukla’s article in this issue–Editor). She pointedout practical difficulties encountered in fieldwork whiletaking photos or shooting to document the carnival,in particular to gender constraints.Documentation from collectingmaterial anddisplayingobjects topresent thefindings andthe ultimateresults of aninvestigationwith possiblythe help ofvisual and audiomaterial orexhibition ofobjects and textsraises a number of questions. Venugopal wonderedabout the cognitive status and extent of validity of adocument, which claims to actually represent the reality.There is in a document more than what one sees. Thereis first what we selected and choose to present, andhow and why we gave it a definite signification. Usuallythis is not spelt out when we write a book. What isbeyond or behind? G. Poitevin raised the point ofanother distinction to be made especially with referenceto documenting through visual material, to twocognitive processes, the one of the scholar constructinga document and the other one of the receiver whoseinsights depends on the symbolic values that the imageshave for him. The image has an uncontrollableeffectiveness of its own. Here are two separate worldsof meaning construction. Henry Glassie sharedreflections on the nature of folk creativity. His experiencetaught him to move from a song text and singer’s songtowards the whole life environment and culture of thoseconcerned (housing, cloth and dresses, cooking andfood habits, architecture and material culture in general),which are consonant with the song. People sing songs asGarisar Lake gate<strong>IN</strong>DIAN FOLKLIFE VOLUME 1 ISSUE 5 APRIL 2001

FOLKLORE AND CREATIVITYtheir house looks. The best way to protect people anddocument their potentialities is, first, to reveal theirnames and identity as individuals with reference to theirenvironment, instead of hiding them under emptygeneralisations or deleting their personal lifefeatures. Extractinga performance outof the performer’slife space andsocial relationsc a n n o tapprehendindividual’screativity. Aperformer’screativitylies in theirrapport.Secondly,with regard to theperformance itself, no tune repeatsitself two times absolutely equal to itself. A storyonce repeated will adapt to each particular situationand only variants exist. The storyteller’s creativity isrealised when we listen several times to the same storyin different moments and situations. The tale is affectedby the interaction of the teller with his audience, andthe ethnographer as well, while being narrated.Creativity is the function of interaction. There is nopure, original folk-tale. The text of a tale or song thatremains with the ethnographer is only an abstract, anemblem or a short sample of the reality of the singerand his culture.Kherati Ram Bhatt’s homeAll theories arebound todisabuseFolklore is notan anonymouscultural item.We oftenassume thata folktraditionsuch as asong or atale is acollectivewealth and has nocomposer. Even when the composer’sname is not known, a great poet composer willbe credited with the song creation, as is the case inIreland. It was felt that the issue of the individual versusthe collective in respect of oral traditions should not beviewed only with reference to a western approach tofolklore, in which the concept is applied to modernpractices and innovations which are launched byindividuals before becoming popular in the opinion; asAt Ghazi Khan’s Institute-Bharnaa consequence legal questions of authorship andcopyright are to be acknowledged once the product hasbecome a commodity. The example of a song composedby a Rajasthani traditional singer and shared by thewhole community of Manganiyar singers for decades inRajasthan before being commercially appropriated bymass media with an immense and profitable successbecomes a legal question of authorship and copyrightin a modern context only. The previous popularity ofthe song was not credited to an individual’s rights andconsciousness against the collective consciousness ofhis community. This does not mean that folk songs inIndia are cultural goods, which belong nowhere andstand as nobody’s property; the performers own themas the common heritage of their community. Even whenno name can be mentioned as the author of a givenfolklore, this does not mean that the latter can beconsidered as an aesthetic item isolated from mooringsin a concrete community and surviving withoutperformers or carriers.This issue of individual carriers or performers versus acommunity was unsatisfactorily discussed. Let us referto two instances of traditional practices. The story-tellerof an oral narrative will put his name as being thenarrator or carrier but not the author of the tale or mythwhich the whole community owns as his wealth; thenarrative does not stand by itself as anybody’s ornobody’s story, but neither as a singular individual’sproperty. Similarly, the formula of identification andthe signature of authentification of the collectivetradition of the grind mill songs in India are spelt outby the phrase: I tell you, woman. This implies a sharedappropriation of the tradition by an individual womansinger in the performance itself, through embeddingherself and incorporating her testimony within thecommon heritage; the question of ascribing the song toan individual artist’s name never occurs and would seemincongruous. Artist’s anonymity points simultaneouslyto a commonly shared heritage and a deeplypersonalised identification of oneself within the commonheritage in the moment it is received and commonlycarried over.Should we not conceive of a process of individualisationor personalisation growing abreast with an increasingsymbiotic interaction of each carrier with the othermembers of his community, each one reaching in eachperformance a deeper stage of himself/herself or shapinga new a material heritage through his/her identificationwith the very collective heritage of the community? Theindividual and the collective seem to be better construedinteractively and communicatively than antitheticallywhen we deal with traditional forms of tangible orintangible culture. This issue is crucial as it has adeterminant bearing on methods and procedures ofdocumentation. It calls for further elaboration as thecreativity and fate of people’s traditions dependconstitutively on the interaction of all members throughmodes of symbolic communication and systems of oral17<strong>IN</strong>DIAN FOLKLIFE VOLUME 1 ISSUE 5 APRIL 2001

FOLKLORE AND CREATIVITY18transmission of knowledge specific to cohesive societies.Here the process of cultural creativity of the individualagent significantly differs from that of a modernindividual in a modern context where orality is no morethe determinant and sole regime of communication.Issues of documentation practices and documentationethics, as well as issues of collective vitality and survivalof traditional oral cultures are to be conceived alongspecific conceptual constructs. A debate remainsnecessary on the concept of living collective traditionand singular ways of traditional creativity with referenceto the multitude of Indian communities, their systemsof mutual relations and symbolic communication, theirindigenous or autonomous knowledge, their expertisein crafts, and last but not the least their every daywisdom. Processes of creativity vary with each of thesedomains and should be documented in minute detailfor each of them. In Japan, folk traditions are alive inplenty. Japan is extremely rich in folktales. Folk can bevibrant with high standard of living. It is equally wrongto connect folk creativity with illiteracy. Why then folksurvive when comfort and high literacy are not adverseto folk traditions and may not mean their extinction?According to Henry Glassie, folk creation emerges whenan individual feels furious against the collective. Threefactors are required for folk to exist: 1) a brave individualready to stand up and refuse the fashion of the many,2) a group of people surrounding him and ready to betaught something else, and 3) a belief in a transcendenceor an ideology, that is to say, a constitutive link betweenoneself and something beyond.Religion is the substratum of folkloreWhen clarification was sought in a small groupdiscussion about the third factor, Henry Glassie definedtranscendent belief as a conviction transcendent toethnicity, environmental constraints, economics andpolitics. Something deep provides a resource fromwithin and is distinct from everyday constraints. Thisresource is usually sought in philosophy or religion.This transcendent resource offers a language differentfrom ordinary language and allows us seeing lifedifferently. That transcendent element is an ideologicalconception in the control of people, not imposed fromoutside. Folk creativity rests upon language or art asmetaphorical form of expression and symboliccommunication. The performers have the ability notonly to make artefacts; they are moreover able to speakabout their art with a language of their own. Thatlanguage helps them to control, transform, and interprettheir art as a system of significance, which helps themto defend it.For instance, potters in Turkey have a language todiscuss life borrowed from Sufi poetry, which is notpart of orthodox Islam, but these sets of poems allowpeople to have a practical and different language oftheir own. When their art of potters is threatened, andthe majority of the potters of Bangladesh or Turkeydecide to discontinue the tradition, many pottersdisappear, but their beautiful language offers a defencewhich a minority avails of, finding in it inspiration andways to overcome. This creativity is not economicallyor politically ground. They avail a means of their ownto protect their art: it is a transcendent force that makessome of them continue their art practices.The person engages himself increating somethingnot only forhim butalso in thename ofoneness witha supremepower or toplease thatpower. Thesame is the casewith weaversand theirweaving. Theidiom is taken fromIslam and notf r o meconomics.Atranscendentideologyprevents theirart fromdisappearing, aresult that asimple economicor utilitarianargument wouldnot be able toperform. Folkforms aresymbolicforms. Thisexplainstheir survivalin the midstof adverseeconomicconstraints.Process of puppet makingFolklore Museum, JaisalmerThis theory ofemergence offolklore wasunfortunately not discussed. It appears amazinglyidentical to theories of popular culture as counter culturewhich flourished in the West some decades ago, forwhich the people, namely, small insurgent groups arethe source of innovation; they are moreover understoodas individuals from low status community, or repressedminorities. It sounds as if the term folklore is justbrought in to replace the term popular. This subjectsGarisar Lake<strong>IN</strong>DIAN FOLKLIFE VOLUME 1 ISSUE 5 APRIL 2001