The Freeman 1972 - The Ludwig von Mises Institute

The Freeman 1972 - The Ludwig von Mises Institute

The Freeman 1972 - The Ludwig von Mises Institute

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

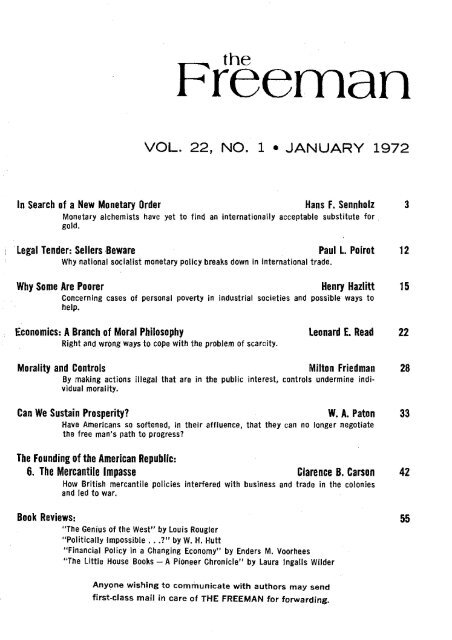

<strong>Freeman</strong>theVOL. 22, NO.1. JANUARY <strong>1972</strong>In Search of a New Monetary Order Hans F. Sennholz 3Monetary alchemists have yet to find an internationally acceptable substitute forgold.Legal Tender: Sellers ,Beware Paul L. Poirot 12Why national socialist monetary policy breaks down in international trade.Why Some Are Poorer Henry Hazlitt 15Concerning cases of personal poverty in industrial societies and possible ways tohelp.Economics: ABranch of Moral PhilosophyRight and wrong ways to cope with the problem of scarcity.Leonard E. Read 22Morality and Controls Milton Friedman 28By making actions illegal that are in the pUblic interest, controls undermine individualmorality.Can We Sustain Prosperity? W. A. Paton 33Have Americans so softened, in their affluence, that they can no longer negotiatethe free man's path to progress?<strong>The</strong> Founding of the American Republic:6. <strong>The</strong> Mercantile Impasse Clarence B. Carson 42How British mercantile policies interfered with business and trade in the coloniesand led to war.Book Reviews: 55"<strong>The</strong> Genius of the West" by Louis Rougier"Politically Impossible ...?" by W. H. Hutt"Financial Policy in a Changing Economy" by Enders M. Voorhees"<strong>The</strong> Little House Books - A· Pioneer Chronicle" by Laura Ingalls WilderAny~me wishing to communicate with authors may sendfirst-class mail in care of THE FREEMAN for forwarding.

the<strong>Freeman</strong>A MONTHLY JOURNAL OF IDEAS ON LIBERTYIRVINGTON·ON-HUDSON. N. Y. 10533 TEL: (914) 591·7230LEONARD E. READPAUL L. POIROTp1resident, Foundation forEconomic EducationManaging EditorTHE F R E E MAN is published monthly by theFoundation for Economic Education, Inc., a nonpolitical,nonprofit, educational champion of privateproperty, the free market, the profit and loss system.,and. limited government.Any interested person may receive its publicationsfor the asking. <strong>The</strong> costs of Foundation projects andservices, including THE FREEMAN, are met throughvoluntary donations. Total expenses average $12.00 ayear per person on the mailing list. Donations are invitedin any amount-$5.00 to $10,000---as the meansof maintaining and extending the Foundation's work.Copyright, <strong>1972</strong>, <strong>The</strong> Foundation for Economic Education, Inc. Printed inU.S.A. Additional copies, postpaid. to one address: Single copy, 50 cents;3 for $1.00; 10 for $2.50; 25 or more, 20 cents each.Articles from this journal are abstracted and indexed in HistoricalAbstracts and/or America: History and Life. THE FREEMAN also isavailable on microfilm, Xerox University Microfilms, Ann Arbor, Mich·igan 48106. Permission granted to reprint any article from this issue,with appropriate credit, except "Why Some Are Poorer" and "Moralityand Controls."

ij~ ~I\~©~ @~ ~ ~m~@~~~~W @~[ID~~HANS F. SENNHOLZEVER SINCE President Nixon suspendedgold payments, on August15, 1971, the question of realisticpar values of the world's currencieshas become a vexing internationalpclitical issue. Governments andCEntral banks are searching fornew rules that permit "more flexible"currency fluctuations. Somethingbeyond dollars and gold isneeded, they believe, to provide asolid base for a new monetary order.Return to the old systemspawned at Bretton Woods, N. H.,in 1944, is out of the question. Itwas a gold and dollar standard,with the U.S. dollar payable ingold ,at $35 an ounce while othercountries pegged their moneys tothe dollar, holding them within arange of 1 per cent up or downDr. Sennholz heads the Department of Economicsat Grove City College and is a notedwriter and lecturer on monetary and economicprinciples and practices.from the parity registered withthe lIB-country InternationalMonetary Fund.Now, since the suspension ofgold payments, the world has beenwaiting for monetary authoritiesto find a new monetary system..<strong>The</strong> process must necessarily beslow, as a political solution issought to economic problems thatwere generated by various politicalconsiderations. After all, thedepreciation of the U.S. dollar,which finally led to the gold paymentsuspension, was a politicalact by the monetary authorities ofseveral Federal administrations.<strong>The</strong> decision to "float" the dollarrather than face the humiliationof a formal devaluation was alsoa political act. Similarly, the othergovernments are motivated politicallyin their attempts at monetarymanagement.3

4 THE FREEMAN JanuaryWhile most "experts" make thegovernment, its powers and objectives,their point of departure formonetary deliberation, a few scholarscontinue to base their inquirieson the fundamental principlesthat flow from individual choiceand action. In their judgment, thefactors that affect the exchangerelations between various nationalcurrencies rest on the economicprinciples that determine the purchasingpower of each and everytype of medium of exchange,whether it is a precious metal orgovernment fiat money.As they see it, the purchasingpower of any monetary unit dependson the relation between thedemand for and the quantity ofmoney in individual cash holdings.<strong>The</strong> demand for money is purelyindividual, although a great manyextraneous factors may influencethis demand. <strong>The</strong>re is, for' instance,the expectation of futurechanges in the exchange value ofmoney. An expected fall tends toreduce the demand for money andthus its purchasing power; an expectedrise brings about the opposite.Also, the availability of goodsaffects the demand for money. Inan expanding economy when moreand better goods are offered onthe market, the demand for moneytends to rise; in a declining economy,where capital is consumedand the division of labor breaksdown, the demand for money tendsto decline.!<strong>The</strong> Stock of Money<strong>The</strong> supply of money is thestock of money available for exchange.During the ,age of thegold standard it consisted of goldbullion, gold coins and their varioussubstitutes, such as banknotes, tokens, and demand deposits.In this age of governmentcurrency, it consists of fiat moneyand its substitutes, such as tokensand demand deposits. <strong>The</strong> substitutesmay either be fully backedby money proper or else they arefiduciary, Le., uncovered. Thus, anexpansion or contraction of fiduciarymedia directly a,ffects thetotal quantity of money availablefor exchange.A change in the money relationthrough changes in either the demandfor money or the stock ofmoney affects changes in the purchasingpower of money. As onefactor of demand or supply cannotperfectly offset changes in theother factors, money can never beneutral. Now, if there a.re two ormore media of exchange, such asgold or silver, or va.rious fiat currencies,what determines the exchangeratio between the various'1 <strong>Ludwig</strong> <strong>von</strong> <strong>Mises</strong>, <strong>The</strong> <strong>The</strong>ory ofMoney and Credit (Irvington-on-Hudson,N. Y.: <strong>The</strong> Foundation for Economic Education,Inc., 1971), p. 97 et seq.

6 THE FREEMAN Januarybetween the various currencyunits consisting of gold thus weredetermined by their relative measuresof gold.International Acceptability<strong>The</strong> world had an internationalcurrency while on the classicalgold standard. It evolved withoutinternational treaties, conventionsor institutions. Noone had tomake the gold standard work asan international system. When theleading countries had adoptedgold as their standard money theworld had an international currencywithout problems of convertibilityor even parity. <strong>The</strong>fact that the coins bore differentnames and had different weightshardly mattered. As long as theyconsisted of gold, the nationalstamp or brand did not negatetheir function as an internationalmedium of exchange.<strong>The</strong> purchasing power of gold,tended to be the same the worldover. Once it was mined, it renderedexchange services throughoutthe world market, moving backand forth and thereby equalizingits purchasing power except forthe costs of transport. It is true,the composition of this purchasingpower differed from place toplace. A gram of gold would buymore labor in Mexico than in theU.S. But as long as some goodswere traded, gold, like any othereconomic good, would move to seekits highest purchasing power andthereby equalize its value throughoutthenworld market. As an coinsand bullion were traded in termsof weight of gold, there were no"exchange rates" such as thosebetween gold and silver, or variousfiat monies.<strong>The</strong> Exchange-Rate Dilemma<strong>The</strong> departure from the goldcoinstandard, set the stage forthe present exchange-rate dilemma.At first, governments beganto restrict the actual circulationof gold. <strong>The</strong>y gradually establishedthe gold-bullion standard inwhich government or its centralbank was managing the country'sbullion supply. Gold coins ,verewithdrawn from individual cashholdings and national currencywas no longer redeemable in goldcoins, but only in large, expensivegold bars. This standard then gaveway to the gold-exchange standardin which the gold reserveswere replaced by trusted foreigncurrency that was redeemable ingold bullion at a given rate. <strong>The</strong>world's monetary gold was held bya few central banks, such as theBank of England and the FederalReserve System, that served as thereserve banks of the world. 3 But3 Cf. Leland B. Yeager, InternationalMonetary Relations (New York: Harper& Row, Publishers, 1966), p. 251 et seq.

<strong>1972</strong> IN SEARCH OF A NEW MONETARY ORDER 7after World War II, the Bank ofEngland which was holding thegold reserves for more than 60countries, commonly called thepound sterling area, gradually lostits eminent position. It began tohold most of its reserves in U.S. dollarclaims to gold, which made theFederal Reserve System the ultimatereserve bank of the world;thus the gold-exchange standardbecame a de facto gold and dollarstandard. Finally, during the acceleratinginflation and credit expansionof the 1960's in the U.S.,the dollar gradually fell from itsrespected position. Several monetarycrises which triggered worldwidedemands for dollar redemptiongreatly depleted the Americanstock of gold, and createdprecarious payment situations.Altogether, in less than fouryears, we experienced seven currencycrises that foretold the endof the international monetary system.In November, 1967, GreatBritain devalued the pound and anumber of other countries immediatelyfollowed suit. In Marchof 1968, under the pressure ofmassive pound sterling liquidation,the nine-nation gold pool wasabandoned and the two-tier systemadopted. <strong>The</strong> third crisis occurredin France in May, 1969,when political riots, followed byrapid currency expansion, greatlyweakened the franc which waslater devalued. <strong>The</strong> fourth crisiserupted in September, 1969, whenmassive dollar conversions to WestGerman marks forced the Germancentral bank to "float" the markand then revalue it upward by 9.3per cent. <strong>The</strong>·. fifth crisis occurredin March and early April, 1971,when a new flight from the dollarthreatened to inundate severalEuropean central hanks. In a concertedeffort, the U.S. Treasuryand the Export-Import Bank endeavoredto "sop up" the dollarflood. <strong>The</strong> sixth crisis began inMay, 1971, when a new flow ofdollars into German marks, Swissfrancs, and several other currenciescaused the mark to float anew,the Swiss franc to be revalued upwardby 7.07 per cent, and severalother currencies to be allowed tofloat or be revalued. <strong>The</strong> seventhand last crisis was of such massiveproportions that PresidentNixon was forced to announce thecollapse of the· old monetary order.Why the Breakdown ofInternational Monetary Relations?What had caused this gradualdeterioration of international monetaryrelations? An understandingof the causes may provide an answerto the dilemma, preventfurther deterioration, and hopefullyfind a cure to all its somberconsequences.<strong>The</strong> popular. explanation usually

8 THE FREEMAN Januaryruns as follows: <strong>The</strong> rapid 'worseningof the U.S. international balance-of-paymentdeficit was theproverbial straw that broke thesystem's back. From a small surplusof $2.7 billion in 1969,achieved mainly through variousgovernment manipulations thatamounted to window dressing, the1970 payments deficit soared to anall-time record deficit of some$10.7 billion, on official settlementbasis, i.e., official settlements betweengovernments only. <strong>The</strong>n, inMay, 1971, the U.S. Commerce Departmentannounced that the firstquarter 1971 deficit had grown toa record $5.4 billion. 4 And finally,private sources estimated that in1971, up through mid-August, some$22 billion more dollars flowed outof the country than came in.<strong>The</strong>se new payment deficitswere added to the accumulated unpaiddeficits of the U.S. for manyyears. U.S. dollars and short-termclaims to dollars in foreign handsamounted to $43 billion at the endof 1970. After deducting U.S.short-term claims on foreignersour net obligations exceeded $32billion, plus the current deficitsmentioned above. And while theU.S. gold stock stood at $11 billion,the lowest level since World WarII, it became obvious that the U.S.4 Federal Reserve Bulletin, Sept., 1971,p. A75.could not meet its foreign obligationsin gold. 5Dr. Arthur F. Burns, Chairmanof the Federal Reserve Board,probably reflected the official positionof the U.S. government when,on May 20, 1971, he blamed foreigngovernments for the precarioussituation. He urged them torelease their restraints on importsand American investments, and tohelp us with our foreign militaryoperating expenses. Raising ourinterest rates, he asserted, was notthe right way to improve the ailingdollar. He advocated more U.S.borrowing from the Eurodollarmarket through Treasury certificatesand, in order to become morecompetitive in world markets, an"incomes policy" that would restrainthe cost-push momentum ofAmerican labor. 6 Less than threemonths later President Nixon announceda 90-day price and wagefreeze, to be followed by some governmentcontrol thereafter, and a10 per cent surtax on imports tostem the floodgoods.of cheap foreignIINafional Balance of Payment llAcademic theories basically concurredwith Dr. Burns' explanationalthough some offered differentsolutions, such as a crawling5 Ibid., p. 94.6 <strong>The</strong> Commercial and FinancialChronicle, June 9, 1971, p. 16.

<strong>1972</strong> IN SEARCH OF A NEW MONETARY ORDER 9peg, a wider bank, flexible exchangerates, or the creation ofnew reserve assets, such as SpecialDrawing Rights by the InternationalMonetary Fund. 7 But nomatter what solution they proffer,their point of departure is.the collectivistconcept of the "national"balance of payment. Without anyreference to individual actions andbalances, they build ambiguousstructures that ignore the causes.Balance of payments of a countryis that very small segment of thecombined balances of millions ofindividuals, the segment that is7 Cf. William Fellner "On Limited ExchangeRate Flexibility," Chapter 5 ofMaintaining and Restoring Balance inInternational Payments, Princeton UniversityPress, 1966; George N. Halm,"<strong>The</strong> Bank Proposal: <strong>The</strong> Limit of PermissibleExchange Rate Variations,"Princeton Special Papers in InternationalEconomics, No.6; John H. Williamson:"<strong>The</strong> Crawling Peg," Princeton Essays inInternational Finance, l'fo.50; FrancisCassell, International Adjustment andthe Dollar, 9th District Economic InformationSeries, Federal Reserve Bank ofMinneapolis, June, 1970; Walter S. Salant,"International Reserves and PaymentsAdjustment;" Banca Nazionale delLavoro, Quarterly Review, Sept., 1969;Thomas D. Willet and Francesco Forte,"Interest Rate Policy and External Balance,"Quarterly Journal of Economics,May, 1969; Friedrich A. Lutz, "MoneyRates of Interest, Real Rates of Interest,and Capital Movements," Chapter 11 ofMaintaining and Restoring Balance inInternational Payments, Princeton UniversityPress, 1966; Milton Gilbert, "<strong>The</strong>Gold-Dollar System: Conditions of Equilibriumand the Price of Gold," PrincetonEssays in International Finance, No. 70.based on personal exchangesacross national boundaries. As anindividual may choose to increaseor decrease his cash holdings, somay the millions of residents of agiven country. But when they increasetheir holdings, that iscalled "favorable" in balance ofpayments terminology. And whenthey choose to reduce their cashholdings, that is called "unfavorable."<strong>The</strong> fact is that drains ofgold are not mysterious forcesthat must be managed by wisegovernments, but are the result ofdeliberate choices by people eagerto reduce their cash holdings.Wherever governments resort toinflation, people tend to reducetheir cash holdings through purchasesof goods and services. Whendomestic prices begin to rise whileforeign prices continue to be stableor rise at lower rates, individualslike to buy more foreign goods atbargain prices. <strong>The</strong>y ship some oftheir money ab!oad in exchangefor cheaper foreign products orproperty. Thus, an outflow of foreignexchange and gold sets in. Itis the inevitable result of a rate ofdomestic inflation that exceedsthat of the rest of the world andsets into operation "Gresham'sLaw."During the 1960's, the decade ofthe "Great Society," and againduring 1970 and 1971, money andcredit were created at unprece-

10 THE FREEMAN Januarydented rates prompted by recordbreakinggovernment deficits. Privatedemand deposits, bank creditat commercial banks, and FederalReserve credit, which is fuelingthe credit expansion, often rose atrates of 10 per cent or more a year.<strong>The</strong>refore, in spite of countlesspromises and reassurances by thePresident and his advisers, theU.S. dollar suffered inevitable depreciationat horne and abroad.And the August 15, 1971, defaultof payment was the result of thisdepreciation.Blaming the CreditorRefusal to make gold paymentsby the United States, the richestand most powerful country onearth, casts serious doubt on futuremonetary cooperation. <strong>The</strong>immediate prospect for worldwidemonetary reform is not toobright. <strong>The</strong> U.S., as the defaultingdebtor, is taking· the positionthat it is up to the countries withhuge surpluses in their internationalpayments to adjust theircurrencies upward against the dollar.It is Washington's basic premisethat the U.S. was unfairlytreated in international commerceand that it is time for correction.Convinced of the indispensabilityof the U.S. dollar as a world reservecurrency, the U.S. is defiantlywaiting for the others to act.Bad debtors, when called uponto make payment, often make suchcharges against their creditors. Itis shocking, however, that the U.S.government should prove to besuch a poor debtor. Even its basicassumption, the indispensability ofthe dollar, no longer goes unchallenged.Sterling balances ,lookmore attractive today than dollarholdings. In fact, the holdings ofdeutsche marks by central banksand treasuries probably exceed $3billion. Foreign airlines and shippershave ceased to accept U.S.currency. And Eurodollar bondsare all but unsaleable in Europeancapital markets, while mark, guilder,and Swiss franc securities remainin demand. <strong>The</strong> foreign positiongenerally rejects the Washingtoncharge of unfair treatment.If the U.S. had adopted appropriatedomestic policies, foreign officialsargue, it would not haveaccrued its huge international paymentsdeficits. <strong>The</strong>refore, theywant the U.S. to share the burdenof realignment. <strong>The</strong>y are seekinga devaluation of the dollar alongwith realignment of their currencies.And above all, no one is suggestingthat the U.S. dollar continueto serve as an internationalreserve currency.After all, managed currenciesare the products of political manipulationsby parties and pressuregroups, and all are destined to bedestroyed gradually by. weak ad-

<strong>1972</strong> IN SEARCH OF A NEW MONETARY ORDER 11ministrations yielding to popularpressures for government largessand economic redistribution. Nosuch currency can serve for longas the international reserve currencyto which all others can repair.<strong>The</strong> U.S. dollar is no exception.In the chaotic conditions of late1971, the world may still have thefollowing options:(1) It may continue on its presentroad of fiat money and inflation,government manipulation ofexchange rates, trade restrictions,and exchange controls. <strong>The</strong> goal is"national autonomy" in monetaryand fiscal policies, an essential objectivefor all forms of central economicplanning. On this road weare bound to suffer not only moreinflation and depreciation, but alsoa gradual disintegration of theworld economy and its division oflabor. Our ultimate destination isa world-wide depression.(2) Or the world may choose toturn off this road of self-destructionand seek stability in soundmoney. <strong>The</strong> very monetary authoritiesthat have created thechaos and are now sitting in judgmentover the, international monetaryorder must relinquish theirrights and powers over the people'smoney. This road leads to thevarious forms of gold standard,from the gold-exchange to thegold-bullion, and finally the goldcoinstandard. For gold is the onlyinternational money the quantityof which is limited by high costsof mining and the value of whichis independent of political aspirationsand policies. Only the goldstandard can afford monetary stabilityand peaceful internationalcooperation. ~IDEAS ONLIBERTYFreedom is the AnswerTHERE IS NOTHING wrong with money that freedom will not cure.This is another way of saying that the Good Society which manyreformers have sought by way of monetary reform' cannot beachieved that way; if it is ever to be achieved, it will be done byfreedom. So, then, the fight for sound money, to have meaning,must be related to the broader fight for freedom. It is only oneof the several battles that must be fought.F RAN K C HOD 0 R 0 v, from "Shackles of Gold"

'10PAUL L. POIROTSellers BewareA PLEASANT premise underlyingsocialism is that everyone shouldbe able and willing to pay priceshigh enough to cover costs. <strong>The</strong>n,no one ever would be obliged towork for less than "a living wage."Such is the foolish dream of personswho do not understand theprocess and the advantages of freetrade.True, oue trades in order togain something of greater valueto him than what he gives up inexchange, and so does every othertrader. Each strives to satisfy hiswants with the least effort or expenditure;but the trader differsfrom socialists for he does not expectanyone else to give up somethingfor nothing.A second significant differencebetween a trader and a socialistconcerns their respective viewsabout money. To a trader, moneyis that particular item of commerceso much more universallyacceptable in trade than otherscarce and valuable items that itserves as a useful medium of exchange.It opens up a far widerrange of market opportunitiesthan could possibly be reachedthrough direct barter. It is usefulas money because the overwhelmingmajority of traders are willingand anxious to accept it in paymentfor their wares.An entirely different concept ofmoney is implied in the languageand philosophy of socialism. Thosewho speak of "a living wage" andof "prices high enough to covercosts" are not thinking about willingcustomers, or of a money that

<strong>1972</strong> LEGAL TENDER: SELLERS· BEWARE 13arises naturally out of willing exchangesin the open market. Whatthey seem to have in mind, instead,is a purchasing power to becreated out of thin air - that ancientdream of alchemists andcounterfeiters.Counterfeiters Need ilLegal Tender llNow, it's easy enough to takea base metal and color it "gold,"or to print a slip of paper and callit "money." <strong>The</strong> trick is to makeothers believe it. Counterfeitersand confidence men are indeed anuisance to producers, traders,savers, especially to those who arewilling to venture into shadydeals. But with a bit of experienceand wariness, an honest •tradercan readily spot such risks and directhis business toward men andmoney he trusts.So, what is the poor counterfeiterto do? He will do his bestto have his "money" declared legaltender, which means that the governmentwould force creditors toaccept it when offered in paymentof any debt.Any debt? Including taxes? <strong>The</strong>government that levies and collectstaxes is expected to grant tosomeone a note-printing monopoly?It takes no political geniusto rise to the conclusion that ifanyone is to print notes to be enforcedas legal tender, surely thatmonopoly had best be exercised bythe government itself! And that issocialist monetary policy in a nutshell:the government in full controlof the "money machine."If government expenditures rise,just print additional bogus money.Soon enough,. this bogus-moneydeclared-legal-tenderwill havedriven into hoarding or hidingany more substantial or trustworthymedium of exchange. AsSir Thomas Gresham observed:"Bad money drives out good."This is the monetary manifestationof the more general law thatpeople always.will use the cheapestand easiest means available toobtain their various ends. In otherwords, if the government decreesthat a piece of paper or an alloyedcoin is equal in purchasing powerto the precious metal that themarket had chosen as money, thencustomers will do their best tomake sellers take the bad money.And even the most honest andscrupulous of men will gladly usethe bad money to meet his taxpayments.However, a small problem loomsfor a national government: itstaxing power and legal tendermonopoly end at the border. Itmay be able to fool or to browbeatforeign suppliers for a time intoaccepting printed p~per to covertrade deficits ; but eventually, internationaltrade balances are payablein goods of value, such as

14 THE FREEMAN Januarygold. Even an international monetarycartel such as the BrettonWoods a.greement breaks down assoon as the gold runs out - abreakdown which President Nixondeclared official on August 15,1971.It Stops at the BorderAt this point, let us pick up thethread of the labor theory of valuewith which we began this discussionof inflation: the socialisticpresumption that everyone is entitledto "a living wage," whetheror not he earns it. <strong>The</strong> late LordKeynes translated this fallacy intothe language of politics, sayingin effect:. the way to stay in officeis to woo organized labor; if theunions demand higher wages, meettheir demands through use of themoney machine.Some witnesses, seeing that the"money" button is now beingpushed by organized labor, havecome to the remarkable conclusionthat this is a new kind of "costpush"inflation, unlike the old "demand-pull"type; the union wagedemands are pushing prices up,so the money-machine isn't theculprit after all. <strong>The</strong>refore, let'sfreeze wages and let the machinerun until the economy has regainedits health! That, too, wasimplicit in the official declarationof August 15, 1971.Despite all the InternationalBrotherhoods of this and that, thenew "cost-push" inflation has nogreater power over foreignersthan has any other name for thegame. In the markets of the world,it's' still the same: put up, or shutup; if you want our goods andservices, give us your goods oryour gold; worthless paper not acceptedhere; the exorbitant wagedemands of American labor unionsare not legal tender in Japan, sosorry!So, in the final analysis, what anation can do is to inflate itselfout of the world market and practiceits splendid isolationism tothe very brink of its own disaster- if not further. And a citizenrythat will thus demand and toleratesocialism fully deserves it. Nor isit an eff~ctive cure for inflation todemand that the government morestringently regulate the monopolypowers granted to organized labor;of course those powers are usedand abused to everyone's detrimentand ought to be withdrawn.So should numerous other specialprivileges and government-sanctionedinterventions that disruptpeaceful production and trade.However, as long as the governmenthas power to declare thatpaper is legal tender, there is littleprospect that the economy may befree of inflation and socialism. I)

I lyWhySomeArePo - erHENRY HAZLITTTHROUGHOUT HISTORY, until aboutthe middle of the eighteenth century,mass poverty was nearlyeverywhere the normal conditionof man. <strong>The</strong>n capital accumulationand a series of major inventionsushered in the IndustrialRevolution. In spite of occasionalsetbacks, economic progress becameaccelerative. Today, in theUnited States, in Canada, in nearallof Europe, in Australia,New Zealand, and Japan, masspoverty has been pra.ctically eliminated.It has either been conqueredor is in process of beingconquered by a progressive capitalism.Mass poverty is still foundin most of Latin America, most ofAsia, and most of Africa.Yet even the United States, theHenry Hazlitt is well known to FREEMANreaders as author, columnist, editor, lecturer,and practitioner of freedom. This article willappear as a chapter in a forthcoming book, <strong>The</strong>Conquest of Poverty, to· be published by ArlingtonHouse.most affluent of all countries, continuesto be plagued by "pockets"of poverty and, by individual poverty.Temporary pockets of poverty,or of distress, are an almost necessaryresult ofa free competitiveenterprise system. In such a systemsome firms and industries aregrowing or being born, others areshrinking or dying; and many entrepreneursand workers in thedying industries are unwilling orunable to change their residenceor their occupation. Pockets ofpoverty may be the result of afailure to meet domestic or foreigncompetition, of a shrinkageor disappearance of demand forsome product, of mines or wellsthat have been exhausted, of landthat has become a dust bowl, andof droughts, floods, earthquakes,and other natural disasters. <strong>The</strong>reis no way of preventing most of15

16 THE FREEMAN Januarythese contingencies, and no all-encompassingcure for them. Each islikely to call for its own specialmeasures of alleviation or adjustment.Whatever general measuresmay be advisable can best be consideredas part of the broaderproblem of individual poverty.This problem is nearly alwaysreferred to by socialists as "theparadox of poverty in the midst ofplenty." <strong>The</strong> implication of thephrase is not only that such povertyis inexcusable, but that itsexistence must be the fault ofthose who have the "plenty." Weare most likely to see the problemclearly, however, if we stop blaming"society" in advance and seekan unemotional analysis.Diverse and InternationalWhen we start seriously to itemizethe causes of individual poverty,absolute or relative, theyseem too diverse and numerouseven to classify. Yet in most discussionwe do find the causes ofindividual poverty tacitly dividedinto two distinct groups - thosethat are the fault of the individualpauper and those that are not.Historically, many so-called "conservatives"have tended to blamepoverty entirely on the poor: theyare shiftless, or drunks or bums:"Let them go to work." Most socalled"liberals," on the otherhand, have tended to blame povertyon everybody but the poor:they are at best the "unfortunate,"the "underprivileged," if not actuallythe "exploited," the "victims"of the "maldistribution ofwealth," or of "heartless laissezfaire."<strong>The</strong> truth, of course, is not thatsimple, either way. We may, occasionally,come upon an individualwho seems to be poor throughno fault whatever of his own (orrich through no merit of his own).And we may occasionally find onewho seems to be poor entirelythrough his own fault (or rich entirelythrough his own merit).But most often we find an inextricablemixture of causes for anygiven person's relative poverty orwealth. And any quantitative estimateof fault versus misfortuneseems purely arbitrary. Are weentitled to say, for example, thatany given individual's poverty isonly 1 per cent his own fault, or99 per cent his own fault - or fixany definite percentage whatever?Can we make any reasonably accuratequantitative estimate of thepercentage even of those who arepoor mainly through their ownfault, as compared with thosewhose poverty is mainly the resultof circumstances beyond their control?Do we, in fact, .have any objectivestandards for making theseparation?A good idea of some of the older

<strong>1972</strong> WHY SOME ARE POORER 17ways of approaching the problemcan be obtained from the articleon "Poverty" in <strong>The</strong> Encycloped'iaof Social Reform, published in1897. 1 This refers to a table compiledby a Professor A. G. Warnerin his book, Ameri,can Charities.This table brought together theresults of investigations in 1890to 1892 by the charity organizationsocieties of Baltimore, Buffalo,and New York City, the associatedcharities of Boston and Cincinnati;the studies of CharlesBooth in Stepney and St. Pancrasparishes in London, and the statementsof Bohmert for 76 Germancities published in 1886. Each ofthese studies tried to determinethe "chief cause" of poverty foreach of the paupers or poor familiesit listed. Twenty such "chiefcauses" were listed altogether.Professor Warner converted thenumber of cases listed under eachcause in each study into percentages,whereverthis had not alreadybeen done; then took an unweightedaverage of the resultsobtained in the fifteen studies foreach of these "Causes of Povertyas Determined by Case Counting,"and came up with the followingpercentages. First came six"Causes Indicating Misconduct":Drink 11.0 per cent, Immorality4.7, Laziness 6.2, Inefficiency and1 Ed. by Wm. D. P. Bliss (New York:Funk & Wagnalls).Shiftlessness 7.4, Crime and Dishonesty1.2, and Roving Disposition2.2 - making a total of causesdue to misconduct of32.7 per cent.Professor Warner next itemizedfourteen "Causes IndicatingMisfortune" : Imprisonment ofBread Winner 1.5 per cent, Orphansand Abandoned 1.4, Neglectby Relatives 1.0, No Male Support8.0, Lack of Employment 17.4, InsufficientEmployment 6.7, PoorlyPaid Employment 4.4, Unhealthyor Dangerous Employment 0.4, Ignoranceof English 0.6, Accident3.5, Sickness or Death in Family23.6, Physical Defect 4.1, Insanity1.2, and Old Age 9.6 - makinga total of causes indicating misfortuneof 84.4 per cent.No Objective StandardsLet me say at once that as astatistical exercise this table isclose to worthless, full of moreconfusions and discrepancies thanit seems worth analyzing here.Weighted and unweighted averagesare hopelessly mixed. Andcertainly it seems strange, for example,to list all cases of unemploymentor poorly paid employmentunder "misfortune" and noneunder personal shortcomings.Even Professor Warner pointsout how arbitrary most of thefigures are: "A man has beenshiftless all his life, and is nowold; is the cause of poverty shift-

18 THE FREEMAN Januarylessness or old age? . . . Perhapsthere is hardly a single case in thewhole 7,000 where destitution hasresulted from a single cause."But though the table has littlevalue as an effort in quantification,any attempt to name and classifythe causes of poverty does call attentionto how many and variedsuch causes there can be, and tothe difficulty of separating thosethat are an individual's own faultfrom those that are not.An effort to apply objectivestandards is now made by the SocialSecurity Administration andother Federal agencies by classifyingpoor families under "conditionsassociated with poverty."Thus we get comparative tabulationsof incomes of farm and nonfarmfamilies, of white and Negrofamilies, families classified by ageof "head," male head or femalehead, size of family, number ofmembers under 18, educational attainmentof head (years in elementaryschools, high school, orcollege) , employment status ofhead, work experience of head(how many weeks worked or idle),"main reason for not working: illor disabled, keeping house, goingto school, unable to find work,other, 65 years and over"; occupationof longest job of head,number of earners in family; andso on.<strong>The</strong>se classifications, and theirrelative numbers and comparativeincomes, do throw objective lighton the problem, but much still dependson how the results are interpreted.Oriented Toward the futureA provocative thesis has beenput forward by Professor EdwardC. Banfield of Harvard inhis book, <strong>The</strong> Unheavenly' City.2He divides American society intofour "class cultures": upper, middle,working, and lower classes.<strong>The</strong>se "subcultures," he warns, arenot necessarily determined bypresent economic status, but bythe distinctive psychological orientationof each toward providingfor a more or less distant future.At the most future-oriented endof this scale, the upper-class individualexpects long life, looksforward to the future of his children,grandchildren, even greatgrandchildren,and is concernedalso for the future of such abstractentities as the community,nation, or mankind. He is confidentthat within rather wide limits hecan, if he exerts himself to do so,shape the future to accord withhis purposes. He therefore hasstrong incentives to "invest" inthe improvement of the futuresituation - i. e., to sacrifice somepresent satisfaction in the expectationof enabling someone (him-2 Boston: Little Brown, 1970.

<strong>1972</strong> WHY SOME ARE POORER 19self, his children, mankind, etc.)to enjoy greater satisfactions atsome future time. As contrastedwith this:"<strong>The</strong> lower-class individual livesfrom moment to moment. If hehas any awareness of a future, itis of something fixed, fated, beyondhis control: things happen tohim, he does not make them happen.Impulse governs his behavior,either because he cannot disciplinehimself to sacrifice a present fora future satisfaction or becausehe has no sense of the future. Heis therefore radically improvident:whatever he cannot consumeimmediately he considersvalueless. His bodily needs (especiallyfor sex) and his taste for'action' take precedence over everythingelse - and certainly overany work routine. He works onlyas he must to stay alive, and driftsfrom one unskilled job to another,taking no interest in the work."3Professor Banfield does not attemptto offer precise estimates ofthe number of such lower-class individuals,though he does tell us atone point that "such ['multiproblem']families constitute a smallproportion both of all families inthe city (perhaps 5 per cent atmost) and of those with incomesbelow the poverty line (perhaps 10to 20 per cent) . <strong>The</strong> problems thatthey present are out of proportion3 Ibid., p. 53.to their numbers, however; in St.Paul, Minnesota, for example, asurvey showed that 6 per cent ofthe city's families absorbed 77 percent of its public assistance, 51per cent of its health services, and56 per cent of its mental health andcorrection casework services."4Obviously if the "lower class culture"in our cities is as persistentand intractable as Professor Banfieldcontends (and no one candoubt the fidelity of his portraitof a sizable group), it sets a limiton what government policy makerscan accomplish.By Merit, or by LuckIn judging. any program of relief,our forefathers usuallythought it necessary to distinguishsharply between the "deserving"and the "undeserving"poor. But this, as we have seen, isextremely difficult to do in practice.And .it raises troublesomephilosophic problems. We commonlythink of two main factors asdetermining any particular individual'sstate of poverty or wealth- personal merit, and "luck.""Luck" we tacitly define as anythingthat causes a person's economic(or other) status to be betteror worse than his personal meritsor efforts would have earnedfor him.Few of us are objective in4 Ibid., p. 127.

20 THE FREEMAN Januarymeasuring this in our own case.If we are relatively successful,most of us tend to attribute oursuccess wholly to our own intellectualgifts or hard work; if wehave fallen short in our worldlyexpectations, we attribute the outcometo some stroke of hard luck,perhaps even chronic hard luck.If our enemies (or even some ofour friends) have done better thanwe have, our temptation is toattribute their superior successmainly to good luck.But even if we could be strictlyobjective in both cases, is it alwayspossible to distinguish betweenthe results of "merit" and"luck"? Isn't it luck to have beenborn of rich parents rather thanpoor ones? Or to have receivedgood nurture in childhood and agood education rather than to havebeen brought up in deprivationand ignorance? How wide shall wemake the concept of luck? Isn'tit merely a man's bad luck if heis born with bodily defects - crippled,blind, deaf, or susceptible tosome special disease? Isn't it alsomerely bad luck if he is born witha poor intellectual inheritancestupid,feeble-minded, an imbecile?But then, by the same logic,isn't it merely a matter of goodluck if a man is born talented,brilliant, or a genius? And if so,is he to be denied any credit ormerit for being brilliant?We commonly praise people forbeing energetic or hard-working,and blame them for being lazy orshiftless. But may not these quaHtiesthemselves, these differencesin degrees of energy, be just asmuch inborn as differences in physicalor mental strength or weakness?In that case, are we justifiedin praising industriousnessor censuring laziness?However difficult such questionsmay be to answer philosophically,we do give definite answers tothem in practice. We do not criticizepeople for bodily defects(though some of us are not abovederiding them) , nor do we (exceptwhen we are irritated) blame themfor being hopelessly stupid. Butwe do blame them for laziness orshiftlessness, or penalize them forit, because we have found in practicethat people· do usually respondto blame and punishment, orpraise and reward, by puttingforth more effort than otherwise.This is really what we have inmind when we try to distinguishbetween· the "deserving" and the"undeserving" poor.What Happens to Incentive<strong>The</strong> important question alwaysis the effect of outside aid on incentives.We must remember, onthe one hand, that extreme weaknessor despair is not conduciveto incentive. If we feed a man who

<strong>1972</strong> WHY SOME ARE POORER 21has actually been starving, we forthe time being probably increaserather than decrea.se his incentives.But as soon as we give anidle able-bodied man more thanenough to maintain reasonablehealth and strength, and especiallyif we continue to do thisover a prolonged period, we riskundermining his incentive to workand support himself. <strong>The</strong>re areunfortunately many people whoprefer near-destitution to takinga steady job. <strong>The</strong> higher we makeany guaranteed floor under incomesthe larger the number ofpeople who will see no reasoneither to work or to save. <strong>The</strong>cost to even a wealthy communitycould ultimately become ruinous.An "ideal" assistance program,whether private or governmental,would (1) supply everyone in direneed, through no fault of his own,enough to maintain him in reasonablehealth; (2) would givenothing to anybody not in suchneed; and (3) would not diminishor undermine anybody's incentiveto work or save or improve hisskills and earning power, butwould hopefully even increasesuch incentives.But these' three aims are extremelydifficult to reconcile. <strong>The</strong>nearer we come to achieving anyone of them. fully, the less likelywe are to achieve one of the others.Society has found no perfect solutionof this problem in the past,and seems unlikely to find one inthe future. <strong>The</strong> best we can lookforward to, I suspect, is some never-quite-satisfactorycompromise.Fortunately, in the UnitedStates the problem of relief isnow merely. a residual problem,likely to be of constantly diminishingimportance as, under free enterprise,we 'constantly increasetotal production. <strong>The</strong> real problemof poverty is not a problem of "distribution"but of production. <strong>The</strong>poor are poor not because somethingis being withheld from them,but because, for whatever reason,they are not producing enough.<strong>The</strong> only permanent way to curetheir poverty is to increase theirearning power. ~IDEAS ONLIBERTYSelf-HelpTHE SPIRIT of self-help is the root of all genuine growth in theindividual; and, exhibited in the lives of many, it constitutes thetrue source of national vigor and strength.SAMUEL SMILES

ECONOMICS:A BranchofMoralPhilosophyLEONARD E. READTHE AUTHOR of <strong>The</strong> Wealth ofNati,ons (1776) is frequentlyclassed as an eighteenth centuryeconomist. 'But Adam Smith wasprimarily a professor of moralphilosophy, the discipline which Ibelieve is the appropriate one forthe study of human action andsuch subdivisions of it as may beinvolved in political economy.Moral philosophy is the studyof right and wrong, good and evil,better and worse. <strong>The</strong>se polaritiescannot be translated into quantitativeand measurable terms and,for that reason, moral philosophyis sometimes discredited as lackingscientific objectivity. And it isnot, in fact, a science in the sensethat mathematics, chemistry, andphysics are sciences. <strong>The</strong> effort ofmany economists to make thestudy of political economy a naturalscience draws the subject outof its broader discipline of moralphilosophy, which leads in turn tosocial mischief.Carl Snyder, long-time statisticianof the Federal Reserve Board,exemplifies an economic "scientist."He wrote an impressivebook, Capitalism the Creator.lI agree with this author thatcapitalism is, indeed, a creator,providing untold wealth and materialbenefits to countless millionsof people. But, in spite of all thelearned views to the contrary, Ibelieve that capitalism, in its significantsense, is more than Snyderand many other statisticians andeconomists make it out to be - farmore. If so, then to teach thatcapitalism is fully explained inmathematical terms is to settle forsomething less than it really is.This leaves unexplained and vul-1 Carl Snyder, Capitalism the Creator(New York: <strong>The</strong> Macmillan Company,1940; Arno Press, <strong>1972</strong>), 492 pp.22

<strong>1972</strong> ECONOMICS: A BRANCH OF MORAL PHILOSOPHY 23nerable the real case for capitalism.Snyder equates capitalism with"capital savings." He explainswhat he means in his Preface:"<strong>The</strong> thesis here presented issimple, and unequivocal; in itsgeneral outline, not new. What isnew, I would fain believe, is theproof; clear, statistical, and factualevidence. That thesis is thatthere is one way, and only oneway, that ,any people, in all history,have ever risen from barbarismand poverty to affluence andculture; and that is by that concentratedand highly organizedsystem of production and exchangewhich we call Capitalistic: onew,ay, and one alone. Further, thatit is solely by the accumulation(and concentration) of this Capital,and directly proportional tothe amount of this accumulation,that the modern industrial nationshave arisen: perhaps the sole waythroughout the whole of eight orten thousand years of economichistory."No argument - none whatsoever- as to the accomplishments ofcapitalism, or that it has to dowith "capital savings." But whatis capital?<strong>The</strong> Ideas Behind Capital<strong>The</strong> first answer that comes tomind is that capital means thetools of production: brick andmortar in the form of plants, electricand water and other kinds ofpower, machines of all kinds includingcomputers and other automatedthings, ships at sea andtrains and trucks and planes - youname it! <strong>The</strong>se things are indeedcapital, but is capital in the senseof material wealth sufficient to tellthe whole story of capitalism andits creative accomplishments orpotentialities'?Merely bear in mind that all ofthis fantastic gadgetry on whichrests a high standard of living hasits origin in ideas, inventions, discoveries,insights, intuition, thinkof-thats,and such other unmeasurablequalities as the will to improve,the entrepreneural spirit,intelligent self-interest, honesty,respect for the rights of others,and the like. <strong>The</strong>se are spiritualas distinguished from material orphysical assets, and always theformer precedes and is responsiblefor the latter. This is capitalin its fundamental, originatingsense; this accumulated wisdom ofthe ages - an over-all luminosity- is the basic aspect of "capitalsavings."It is possible to become awareof this spiritual capital, but not tomeasure, let.alone to fully understandit - so enormous is its accumulationover the ages. Awareness?Sit in a jet plane and askwhat part you had in its m,aking.

24 THE FREEMAN JanuaryVery little, if any, even though youmight be on the production line atBoeing. At most, you presssed abutton that turned on forces aboutwhich you know next to nothing.Why, no man even knows how tomake the pencil you used to signa requisition. <strong>The</strong>se "capital savings"put at your disposal an energyperhaps several hundredtimes your own. This accumulatedenergy - the workings of humanminds over the ages - is capital!"Truly Scientific llWith this concept of capital inmind, reflect on how unrealisticare the ambitions of the "scientific"economists. Carl Snyderphrases their intentions well in theconcluding paragraph of his Preface:"It was inevitable, perhaps, thatanything like a "social science"should be the last to develop. Itsbases are so largely statistical thatit was only with the developmentof an enormous body of new knowledgethat anything resembling afirmly grounded and truly scientificsystem could be established.It is coming; already the mostfundamental elements of thisknowledge are now available, asthe pages to follow will endeavorto set forth." (Italics added)Snyder is, indeed, statistical. Hedisplays 44 charts. Nearly all ofthese show the ups and downsmostlyups - of physical assets indollar terms. This, in his view, isa "truly scientific system." Buthow scientific can a measurementbe if the units cannot be quantifiedand the measuring rod is asimprecise in value as is the dollaror any other monetary unit?And what is truly scientificabout showing the growth in coalproduction, for instance, if therebe a shift in demand favoringsome other fuel? This would beonly a pseudo-measurement withno more scientific relevance than acentury-old chart showing the dollargrowth in buggy whip production.Professor F. A. Hayek enlightensus:"All the physical laws of production"which we meet, e.g., in economics,are not physical laws inthe sense of the physical sciencesbut people's beliefs about whatthey can do.... That the objectsof economic activity cannot be definedin objective terms but onlywith reference to a, human purposegoes without saying. Neithera 'commodity' or an 'economicgood,' nor 'foods' or 'money,'can be defined in physical termsbut only in terms of views peoplehold about things."22 See <strong>The</strong> Counter-Revolution of Scienceby F. A. Hayek (New York: <strong>The</strong>Free Press of Glencoe, <strong>The</strong> Crowell-CollierPublishing Co., 1964), p. 31.

<strong>1972</strong> ECONOMICS: A BRANCH OF MORAL PHILOSOPHY 25National AccountingEconomic growth for a nationcannot be mathematically or statisticallymeasured. Efforts to doso are highly misleading. <strong>The</strong>ylead people to believe that a mereincrease in the measured output ofgoods and services is, in and of itself,economic growth. This fallacyhas led to the forced savings programsof centrally administeredeconomic systems - programswhich decrease the range of voluntarychoice among individuals.This is the heart of the· failure ofthe socialistic policies of the underdevelopednations of Asia,Africa,and Latin America. As Prof.P. T. Bauer has written so eloquently:"I regard the extensionof the range of choice, that is, anincrease in the range of effectivealternatives open to people, as theprincipal objective and criterionof economic development; and Ijudge a measure principally by itsprobable effects on the range ofalternatives open to individuals."3Indeed, even an individual's economicgrowth can no more bemeasured, exclusively, in terms ofhistorical statistics than can hisintellectual, moral,and spiritualgrowth. <strong>The</strong>se ups and downs cannotbe defined in physical terms3 P. T. Bauer, Economic Analysis andPolicy in Underdeveloped Countries(Duke University Press and CambridgeUniversity Press, 1957), p. 113.but only in terms of views peoplehold about things. <strong>The</strong>se viewshighlypersonal - are in constantflux ; you may care nothing tomorrowfor that which you highlyprize today.Once we grasp the point that thevalue of any good or service iswhatever others will give in willingexchange) and that the j udgmentsof all parties to all exchangesare constantly and foreverchanging, it should be plainthat even physical assets - money,food, or whatever - do not lendthemselves to measurements in thescientific sense.And when we further reflect onthe fundamental nature of "capitalsavings,"- that they emergeout of ideas, inventions, insights,and the Iike- the idea of scientificmeasurement becom~s patentlyabsurd.In any event, it is this penchantto make a science of political economy,to reduce capitalistic behaviorto charts, st.atistics, theorems,arbitrary sysmbols, thatleads to such nonsense as theGross National Product (GNP),"national goals" and "socialgains."4 <strong>The</strong> more pronounced this4 For more on the GNP fallacy andhow economic growth cannot be "factually"reported, see "A Measure ofGrowth" in my Deeper Than You Think(Irvington-on-Hudson, N. Y.: <strong>The</strong> Foundationfor Economic Education, Inc.,1967), pp. 70-84.

26 THE FREEMAN Januarytrend, the less will the economicsof capitalism and the free societybe understood - "a dismal science,"for certain. Indeed, couldthe ambitions of the "scientificeconomists" be realized, dictatorshipwould be a viable political system.At the dictator's disposalwould be all the formulae, all theanswers; disregarding personalviews and choices, he would simplyrun his information through computersand thus meet productionschedules.When we grasp the point thatno man who ever lived has beenable to foresee his own futurechoices, let alone those of others,economic scientism, as it might becalled, makes no sense.Man'5 ArroganceHow did we ever get off on thisuntenable course? Perhaps we canonly speculate. A flagrant display:At one point in a recent Seminardiscussion I repeated, "Only Godcan make a tree." And then thisexclamation by a graduate student,"Up until now!" This, it appearsto me, is the reflection of a notion,so prevalent in the eighteenth andnineteenth centuries, that everyfacet of Creation, even life itself,lies within the powers of man.Merely a matter of time!To tear human action asunderand then to assign symbols orlabels to the pieces, as the scientistsproperly do with the chemicalelements, is no service to economicunderstanding. This methodmakes understanding impossiblefor the simple reason that itpresupposes numerous phases ofhuman action that can be mathematicallyor scientifically distinguishedone from the other whensuch is not the case. Why am Imotivated to write this or you toread it? Doubtless, each of us canrender a judgment of sorts but itwill not be, cannot be, in the languageof science.Political economy is as easy or,perhaps, as difficult to understandand practice as the Golden Rule orthe Ten Commandments. Economicsis no more than a study of howscarcity is best overcome, and thefirst thing we need to realize isthat this is accomplished by thecontinued application of humanaction to natural resources.Natural resources are what theyare, no more, no less - the ultimategiven! <strong>The</strong> variable is humanaction.Political economy, then, resolvesitself into the study ofwhat is and what is not intelligenthuman action. It should attemptto answer such questions as:.Is creative energy more efficientlyreleased among free or coercedmen?Is freedom to choose as much aright of one as another?

<strong>1972</strong> ECONOMICS: A BRANCH OF MORAL PHILOSOPHY 27Who has the right to the fruitsof labor - the producer or nonproducer?How is value determined - bypolitical authority, cost of production,or by what others will givein willing exchange?What actions of men should berestrained - creative actions oronly destructive actions?How dependent is overcomingscarcity on honesty, respect ofeach for the rights of others, theentrepreneurial spirit, intelligentintepretation of self-interest?Viewed in this manner, politi-cal economy is not a natural sciencelike chemistry or physics but,rather, a division of moral philosophy- a study of what is rightand what is wrong in overcomingscarcity and maximizing prosperity- the problem to which itaddresses itself.Once we drop the "scientific"jargon and begin to study politicaleconomy for what it really is,then its mastery becomes no moredifficult than understanding thatone should never do to othersthat which he would not have·them do unto him. IIIDEAS ONLIBERTYFreedom, an IllusionFREEDOM is an illusion, though an important one; in any society,restraints and restrictions, obligations and compulsions are therealities."Free as the wind" is such an illusion. Consider the restraintsand restrictions and obligations and compulsions. For wind isnothing but air being pushed from areas of high pressure to low,cold and heavy air displacing warmer and lighter air, its coursemodified by solid objects of nature and man in its path, subject toall the laws of gases, gravity, mass, matter, and so on.<strong>The</strong> illusion of freedom has been broad indeed in America withits unique government of limited and specific powers - limitingthe restraints and restrictions, the obligations and compulsions towhich Americans might be subjected. No such illusions of freedompersist in totalitarian societies, be they Communist, Fascist, Socialistor whatever. For it is made abundantly clear that thepeople subject to these regimes are free only to support and servethe state, with ample restraints and restrictions to shatter anyother illusions of freedom.Why is this illusion of freedom so vitally important? Becausethe more free men feel to serve. themselves, their fellows, andtheir Creator, the better they do in fact serve all.J. KESNER KAHN, Chicago, Illinois

28MORALITYandCONTROLSMILTON FRIEDMANMOST DISCUSSION of the wagepricefreeze and the coming PhaseII controls has been strictly economicand operational: were theyneeded, will they work, how willthey operate. I have recorded myown opposition to them in threecolumns- in N eW8week.<strong>The</strong>re has been essentially nodiscussion of a much more fundamentalissue. <strong>The</strong> controls aredeeply and inherently immoral. Bysubstituting the rule of men forthe rule of law and for voluntarycooperation in the marketplace,the controls threaten the veryfoundations of a free society. Byencouraging men to spy and reporton one another, by making itDr. Friedman, Professor of Economics, Universityof Chicago, needs no introduction toFREEMAN readers.This article was first published in two partsin <strong>The</strong> New York Times on October 28 and 29,1971. © 1971 by <strong>The</strong> New York Times Company.Reprinted by permission.in the private interest of largenumbers of citizens to evade thecontrols, and by making actionsillegal that are in. the public interest,the controls undermine individualmorality.One of the proudest achievementsof Western civilization wasthe substitution of the rule of lawfor the rule of men. <strong>The</strong> ideal isthat government restrictions onour behavior shall take the formof impersonal rules, applicable toall alike, and' interpreted and adjudicatedby an independent judiciaryrather than of specific ordersby a government official to namedindividuals. In principle, underthe rule of law, each of us canknow what he mayor may not doby consulting the law and determininghow it applies to his owncircumstances.<strong>The</strong> rule of law does not guaran-

<strong>1972</strong> MORALITY AND· CONTROLS 29tee freedom, since general laws aswell as personal edicts can be tyrannical.But increasing relianceon the rule of law clearly played amajor role in transforming Westernsociety from a world in whichthe ordinary citizen was literally .subject to the arbitrary will of hismaster to a world in which theordinary citizen could regard himselfas his own master.Contract or Status?<strong>The</strong> ideal·was, of course, neverfully attained. More important, wehave been eroding the rule of lawslowly and steadily for decades, asgovernment has become more andmore a participant in economicaffairs rather than primarily arule-maker, referee, and enforcerof private contracts. It was, afterall, the development of the privatemarket that made possible theoriginal movement from a worldof status to a world of voluntarycontract. As government has. triedto replace the market in one areaafter another, it has inevitablybeen driven to restore a world ofstatus.<strong>The</strong> freeze and even more thepay board and· price board of thePhase II controls are clearly anothermassive step away from therule of law and back toward· therule of men. True, the rule of menwill be under law but that is a farcry from the rule of law - Stalin,Hitler, Mussolini, and now Kosygin,Mao, and Franco all rule underlaw.<strong>The</strong> price that you and I maycharge for our goods or our laboror that we may pay others for theirgoods or their labor will now bedetermined, not by any set oflegislated •standards applying toall alike, but by specific orders bya small number of men appointedby the President. And jf governmentaledict is to replace marketcontract, there is no alternative.<strong>The</strong>re are millions of prices, millionsof wage rates arrived at byvoluntary agreements among millionsof people. <strong>The</strong> collectivisticcountries have been unable in decadesto find simple rules enablingprices and. wages to be establishedby any alternative impersonalmechanism.Politics and PatriotismWe are not likely to succeed.And we are not trying. Instead,the appeal is to the patriotism,civic responsibility, and judgmentof political appointees, must ofwhom represent vested interests.How do patriotism and judgmentdetermine that the price of awidget may rise 2.8 per cent butthe price of a wadget, only 0.3 percent; the wage of a widgeteer by2 per cent but of a wadgeteer, by10 per cent? Clearly they do not.

30 THE FREEMAN JanuaryArbitrary judgment, political power,visibility - these are what willmatter.<strong>The</strong> tendency for such an approachto violate human freedomis even more clearly exemplifiedby the present situation with respectto dividends. <strong>The</strong> Presidenthas requested firms not to raisedividends - he has no legal powerto do more. <strong>The</strong> request has beenaccompanied by surveillance, acalling down to Washington andpublic lambasting of the handfulof corporations that did not conform,and a clear, implied threatto use extralegal powers. <strong>The</strong>semeasures have no legal basis atall. Yet I know of only one smallcompany that has had the courageto refuse to cooperate ·on groundsof principle.<strong>The</strong> full logic of the system willnot work itself out this time. Ourstrong tradition of freedom, theineffectiveness of the controls, theingenuity of the people in findingways around them - these willlead to the collapse of the controlsrather than to their hardening intoa full-fledged straitjacket. Butnonetheless, it is disheartening tosee us take this further long stepon the road to tyranny so lightheartedly,so utterly unaware thatwe are doing something fundamentallyin conflict with the basicprinciples on which this country isfounded. <strong>The</strong> first time, we mayventure only a small way. But thenext time, and the next time?A Nation ollnlormersEnforcement of the price andwage controls, as of the freeze,must depend heavily on encouragingordinary citizens to be informers- to report "violations" togovernment officials.When you and I make a privatedeal, both of us benefit - otherwisewe do not have to make it. We arepartners, cooperating voluntarilywith one another. <strong>The</strong> terms, solong as they are mutually agreeable,should be our business. Butnot any longer. Big Brother islooking over our shoulders. Andif the terms do not correspondwith what he says is O.K., one ofus is encouraged to turn in theother. And to turn him in for doingsomething few people haveever regarded and do not now regardas .in any sense morallywrong; on the contrary, for doingsomething that each of us regards,when it affects us, as our basicright. Am I not entitled to sell mygoods or my labor for what I considerthem worth as long as I donot coerce anyone to buy? Is itmorally wrong for Chile to expropriatethe property of AnacondaCopper - Le., to force it tosell its copper mines for a priceless than its value; but morallyright for the U.S. government to

<strong>1972</strong> MORALITY AND CONTROLS 31force the worker to sell his laborfor less than its value to him andto his employer?By any standards, the edicts ofthe pay board and the price board,like the initial freeze, will be fullof inequities and will be judged tobe by ever increasing numbers ofpeople. You believe that you areentitled to a pay raise, your employeragrees and wishes to giveyou one, yet the pay board says no.Will there not be a great temptationto find a way around theruling? By a promotion unaccompaniedby any change in dutiesbut to a job title carrying ahigher permitted pay. Or by youremployer providing you withamenities you formerly paid for.Or by one or another of the innumerablestratagems - legal,quasi-legal, or illegal - that ingeniousmen devise to protect themselvesfrom snooping bureaucrats.Two W fongs = Two W fongsIn general, I have little sympathywith trade unions. <strong>The</strong>y havedone immense harm by restrictingaccess to jobs, denying excludedworkers the opportunity to makethe most of their abilities, andforcing them to take less satisfactoryjobs. Yet surely in thepresent instance they are rightthat it is inequitable for the governmentretroactively to void contractsfreely arrived at. <strong>The</strong> wayto reduce the monopoly power ofunions is to remove the speciallegal immunities they are nowgranted, not to replace one concentratedpOWE1!" by another.When men do not regard governmental.measures as just andright they will find a way aroundthem. <strong>The</strong>. effects extend beyondthe original source, generate widespreaddisrespect for the law, andpromote corruption and violence.We found this out to our cost inthe 1920's. with Prohibition; inWorld War II with price controland rationing; today with druglaws. We shall experience it yetagain with price and wage controlsif they are ever more thana paper fa

32 THE FREEMAN Januarythe controls are enforced, the moreharm they do. <strong>The</strong>y render behaviorwhich is immoral from onepoint of view socially beneficial.<strong>The</strong>y thus introduce the kind offundamental moral conflict that isutterly destructive of social cohesion.Our markets are far from completelyfree. Monopoly power oflabor and business means thatprices and wages are not whollya product of voluntary contract.Yet these blemishes, real and importantthough they are, are minorcompared to replacing marketagreements by government edict,compared to giving arbitrary powerto a small number of appointedofficials, compared to inculcatingin the public contempt for the law.<strong>The</strong> excuse for the destructionof liberty is always the plea ofnecessity - that there is no alternative.If indeed, the economywere in a state of crisis, of a lifeand-deathemergency, and if controlspromised a sure way out, alltheir evil social and moral effectsmight be a price that would haveto be paid for survival. But noteven the gloomiest observer of theeconomic scene would describe itin any such terms. Prices risingat 4 per cent a year, unemploymentat a level of 6 per centtheseare higher than we wouldlike to have or than we need tohave, but they are very far indeedfrom crisis levels. On the contrary,they are rather moderate by historicalstandard. And·there is farfrom uniform agreement thatwage and price controls will improvematters. I happen to believethat they will make matters worseafter an initial deceptive periodof apparent success. Others disagree.But even their warmest defendersrecognizethat they imposecosts, produce distortions in theuse of resources, and may fail toreduce inflation. Under such circumstances,the moral case surelydeserves at least some attention.IDEAS ON*LIBERTY<strong>The</strong> Abolition of Private PropertyA GOVERNMENT that sets out to abolish market prices is inevitablydriven towards the abolition of private property; it has to recognizethat there is no middle way between the system of privateproperty in the means of production combined with free contract,and the system of common ownership of the means of production,or Socialism. It is gradually forced towards compulsory production,universal obligation to labor, rationing of consumption, and,finally, official regulation of the whole of production and consumption.L U D WIG VON MIS E s, <strong>The</strong> <strong>The</strong>ory of Money and Credit

Can we sustainPROSPERITYW. A. PATONTHOUGHTFUL contemplation of thecurrent scene, supplemented withsome scanning of the historicalrecord, is likely to set the observerto wondering if any nation is capableof achieving and maintaininga broadly affluent society. Toilingup the slope, overcoming obstaclesand adversity, human beingsoften display courage, resourcefulness,endurance, tenacity,ability to cope and continue climbing,but when they reach the topof the hill, have it made, manyseem to have a tendency to shedtheir heroic trappings and becomeconfused, disorderly, unenterprising,and - in some cases- downrightshiftless and dependent.<strong>The</strong> cycle of great progress fol-Dr. Paton is Professor Emeritus of Accountingand of Economics, University of Michigan,and is known throughout the world for hisoutstanding work in these fields. His currentcomments on American attitudes and behaviorare worthy of everyone's attention.lowed by decline seems to be in theprocess of striking illustrationhere in America. As to the fact ofan astonishing advance there canbe no question. In two centuries,roughly, the United States hasmoved from a scattering of settlements,loosely affiliated, along oureastern seaboard to a countrystretching across a continent, andrecognized as a major world power.In this period, too, a primitivetechnology has been transformedinto a productive mechanism placingus in a forefront industrial position,with a· per-capita. standardof living that is unmatched, anywhere.In this· process hardshipsand difficulties were encounteredby our forefathers that looked insurmountableat times, and thatwere mastered only by an amazingdisplay of determination and fortitudeon the part of many individualsand families. <strong>The</strong> commitment33

34 THE FREEMAN Januaryof the founders of the nation to arepublican form of government, asexpressed in our constitution, andthe accompanying atmosphere offaith in individual initiative and afree, competitive market economy,undoubtedly played a great, andperhaps decisive, role in makingpossible the tremendous gains thathave been chalked up in such ashort span of years.But now that we've arrived, soto speak, there are ominous signsof decay and collapse. When onelooks squarely at the prevailingtendencies and conditions it is hardto be optimistic about the future.With the widespread slackening ofthe willingness to work, and workdiligently and well, exemplifiedright and left in absenteeism, carelessperformance on the job, demandsfor ridiculously short weeklyworking hours, to mention a fewof the evidences, a decline in productivityper person can hardly beavoided, even if the momentum ofthe technical march is maintainedfor a time and there is persistentabatement in the rate of populationgrowth. Still more serious is theapparent waxing,among many, ofthe spirit of dependency; thereseem to be few signs of reluctanceto accept a place on the relief rollsand no widespread urge to get offthe list of those who are living atthe expense of the taxpayinggroup. <strong>The</strong> fearful increase in thelevel of serious crime, includingdestruction of both private andpublic property, the growing cancerof drug abuse, the outrageousirresponsibility and disorder onthe educational front, the carnageon the highways, are examples ofother factors that are rampantand that surely are having a negativeimpact on the quality of livingas well as the quantity of commoditiesand services available forconsumers.Before going on I should pointout that it would be difficult todemonstrate that marked materialprogress is inherently bound togenerate a general downhill slide;but it does seem clear that weAmericans have suffered a severeattack of softening-up, particularlyevident among the coddledand unruly young folks but foundin varying degrees among all agesand classes. And it also seemsclear that some of the seriousproblems with which we are confrontedcould hardly germinate, tosay nothing of growing like badweeds, in the absence of a highlevel of economic output and prosperity.<strong>The</strong>re is a chain of evidence,too, of cyclical patterns ofbehavior among both individualsand groups, historically as well ascurrently, although there is roomfor argument as to underlyingcauses of rise and fall in particularsituations.

<strong>1972</strong> CAN WE SUSTAIN PROSPERITY? 35Striding into Socialism<strong>The</strong> problems and difficulties referredto above are by no meansthe whole story of what ails us.During the past forty to fifty yearsthe freedom of initiative andchoice that we have enjoyed, andthat is so substantially responsiblefor the progress made, has beenrapidly eroded. Government interferenceand control have beengrowing like the psalmist's greenbay tree. Fostered by war andpostwar problems', the depressionof the early thirties, and the policiespromoted during the Rooseveltera, we have seen the hand ofthe state, at all levels, bearingdown more and more heavily onthe mechanism of the market,throughout the economic pipeline.Business men and politicians arestill giving persistent lip serviceto "our system of free enterprise,"but the continuing reiteration ofthis phrase is becoming a bit absurdin the light of the actualstate of affairs. <strong>The</strong> most discouragingaspect of the situation, forthose with genuine allegiance tothe view that the free competitivemarket is the effective means ofstimulating and directing the economicapparatus, is the extent ofgeneral acquiescence in the marchtoward a completely socialistic society.Indeed, there seems to be an increasingtide of clamor for moreand more government interventionand dictation in the process of productionand distribution, rangingfrom such fields as specificationsfor motor vehicle manufacture tothe details of cereal packaging.This clamor gives evidence of bothgross ignorance and a form ofmysticism. Many act as if theywere unaware of what the freemarket has accomplished for thiscountry, and are equally lacking inthe ability to distinguish betweenthe essence of a· free economy andthe nature of statism. And a hostof people appear to believe that theordinary humans who operate agovernment agency somehow becomesupermen, wizards, whenthey put on the official cloak. Actuallythere is abundant evidencethat government employment isstill not regarded with great favorby many.of the exceptionallytalented and' ambitious and thatthose entering the service of thestate tend to become' insulated bycivil service and other factorsfrom the kind of pressures thatstill prevail in private business,with resulting impairment of anyurge in the direction of top-flightperformance.• Belief in the superiorityof government operationover that of typical private organizationsis surely one of the mostunjustified of all the familiar delusionsfrom which we are suffering.Experience with the mail

36 THE FREEMAN Januaryservice alone should be sufficientto cure anybody - even .the mostgullible - of such a conviction.<strong>The</strong> Poverty Bugaboo<strong>The</strong> activists in the driveagainst private business undertakingsand an economy depending onthe market for guidance generallystart their attack by questioningthe position that by these meanswe have achieved a genuinely prosperousstatus. <strong>The</strong>y can hardlydeny the fact of an astonishingadvance in technical devices andmethods and an accompanyingsurge in the level of economic output,but they contend that the ma-jor benefit of the improvementgoes to the few rather than themany, and that the injustices inherentin the way the pie is cutand distributed are so serious asto warrant the indictment of thesystem rather than its support.That the mechanism of the marketwill not work out perfectly inpractice, even if not harassed orhamstrung by interventions, mustbe acknowledged. <strong>The</strong> Americanexperience, .although extraordinary,has certainly not been freefrom difficulties and inequities;the results, even from a neutralpoint of view, fall short of achievingan ideal state of affairs. <strong>The</strong>frailties of men have not been overcome;unfairness and predatoryconduct have not been eliminated.But any careful examination ofthe available data will show thatthe radical detractors, the peopledetermined to substitute completecollectivism for a still partiallyfreemarket economy, are way offbase. In the first place they makethe old Marxian mistake of assumingthat you can have mass productionwithout mass consumption.If millions of bathtubs aremade there must be millions ofusers; they can't all be crowdedinto the homes of the very wealthy.<strong>The</strong> truth is that capitalism hasbeen the great leveler. In the industrialcountries generally, andespecially in the United States, themost striking feature of the trekup the hill has been the great improvementin the lot of the ordinary,mine-run individual. Withthe development of machine methods,broad markets, and representativegovernment, it becameno longer possible for a small rulingclass to skim off all the cream,leaving the masses at or near thesubsistence level - the conditionprevailing through most of humanhistory.<strong>The</strong> willingness of those workingto destroy private enterpriseand enthrone government to closetheir eyes to the actual situationis somewhat puzzling, and at timesmakes one question the sincerityof their accusations and protestations.It is true, of course, that