Bulletin - Fall 1979 - North American Rock Garden Society

Bulletin - Fall 1979 - North American Rock Garden Society

Bulletin - Fall 1979 - North American Rock Garden Society

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

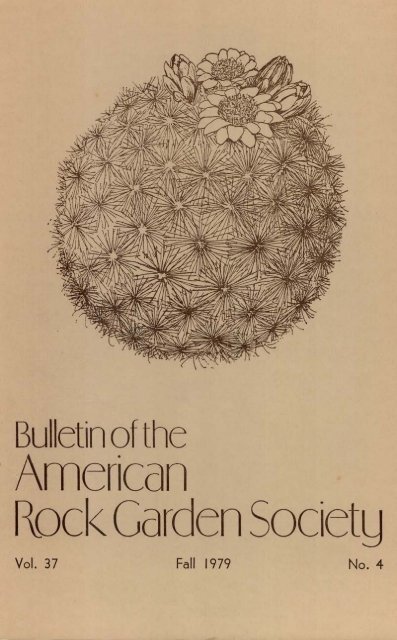

<strong>Bulletin</strong> of the<strong>American</strong>Vol. 37 <strong>Fall</strong> <strong>1979</strong> No. 4

The <strong>Bulletin</strong>Editor EmeritusDR. EDGAR T. WHERRY, Philadelphia, Pa.EditorLAURA LOUISE FOSTER, <strong>Fall</strong>s Village, Conn. 06031Assistant EditorHARRY DEWEY, 4605 Brandon Lane, Beltsville, Md. 20705Contributing Editors:Roy DavidsonAnita KistlerH. Lincoln Foster Owen PearceBernard HarknessH. N. PorterLayout Designer: BUFFY PARKERBusiness ManagerANITA KISTLER, 1421 Ship Rd., West Chester, Pa. 19380Contents Vol. 37 No. 4 <strong>Fall</strong> <strong>1979</strong>Cacti: America's Foremost <strong>Rock</strong> Plants, Part I—Allan R. Taylor and PanayotiCallas 157Aphidicide—Milton S. Mulloy 164Al Fresco in Petropolis: Alpine Newport News—Norman T. Beal; Alpine NewYork City—Dr. Alan Nathans; Alpine Chicago—Vaughn Aiello; AlpineHartford—E. LeGeyt Bailey - 165Dwight Ripley, Plantsman—H. Lincoln Foster 178Edith Hardin English 187A Short Shortia Story—Roy Davidson 188Ralph Bennett—In Memoriam 192Eunomia Oppositifolia—John P. Osborne 193Never Use a <strong>Rock</strong> If You Can Help It—George Schenk 194Book Reviews: Gentians by Mary Bartlett; Asiatic Primulas, A <strong>Garden</strong>ers Guideby Roy Green; Wild Shrubs, Finding and Growing Your Own by JoySpurr 198Of Cabbages and Kings: Report on Animal Repellents; Horticultural Archaeology—LarryHochheimer 199Front Cover Picture—Pediocactus simpsonii—Panayoti Callas, Boulder, ColoradoPublished quarterly by the AMERICAN ROCK GARDEN SOCIETY, incorporated under the lawsof the State of New Jersey. You are invited to join. Annual dues {<strong>Bulletin</strong> included) are:Ordinary Membership, $9.00; Family Membership (two per family), $10.00; Overseas Membership,$8.00 each to be submitted in U.S. funds or International Postal Money Order;Patron's Membership, $25; Life Membership, $250. Optional 1st cl. delivery, U.S. and Canada,$3.00 additional annually. Optional air delivery overseas, $6.00 additional annually. Membershipinquiries and dues should be sent to Donald M. Peach, Secretary, Box 183, Hales Corners,Wi. 53130. The office of publication is located at 5966 Kurtz Rd., Hales Corners, Wi. 53130.Address editorial matters pertaining to the <strong>Bulletin</strong> to the Editor, Laura Louise Foster, <strong>Fall</strong>sVillage, Conn. 06031. Address advertising matters to the Business Manager at 1421 Ship Rd.,West Chester, Pa. 19380. Second class postage paid in Hales Corners, Wi. and additionaloffices. <strong>Bulletin</strong> of the <strong>American</strong> <strong>Rock</strong> <strong>Garden</strong> <strong>Society</strong> (ISSN 0003-0864.)

Vol. 37 <strong>Fall</strong> <strong>1979</strong> No. 4<strong>Bulletin</strong> of themetican<strong>Rock</strong> Catden <strong>Society</strong>Cacti: America's Foremost <strong>Rock</strong> PlantsPart IALLAN R. TAYLOR and PANAYOTI CALLASBoulder, ColoradoDrawings by Panayoti CallasCacti are an integral part of thenatural rock gardens of America; ourindividual rock gardens are necessarilypoorer without them. This statementmay strike the alpine gardening puristas unorthodox at best and hereticalat worst, but we hope to demonstratethat it is neither, that it is, in fact,an obvious truth.If cacti and our native monocotyledonoussucculents are exotic in the eyesof Europeans, they are rather commonplacein this hemisphere. Thefamily extends to practically every stateand province of the Americas fromthe Southern Andes to the windsweptprairies of Alberta and Saskatchewan.No family of plants in this hemisphereis more widespread or characteristicof a broad range of saxatile habitatsthan the cacti. Why saxatile? Becausecacti are most at home among rocks.A few species are restricted to sandyhabitats or grassy plains, but the overwhelmingbulk of the family prefersto grow on well-drained rocky sites.One can travel through countless milesin the heartland of cactus country andscarely encounter a single one amidthe endless flats of Creosote Bush, Mesquiteand Saltbrush. But climb ontothe first rocky ridge and dozens ofspecies will suddenly make an appearance.157

The Cactus Family is not withoutalpine developments. Especially in theSouthern Hemisphere, there are dozensof cactaceous vegetable sheep — porcupinesand hedgehogs in sheep's woolreally —• that haunt the highest screesof the Andes. Even in the United Statesthere are a number of cacti that climbto the tops of the higher desert ranges.An intensely spiny form of Opuntiaerinacea, for instance, hobnobs with theoldest Bristlecone Pines at 11,500 feeton the dolomitic summits of California'sWhite Mountains. Dozens of other speciesare restricted to the high, dry,steppes, plateaus and foothills of Utah,<strong>North</strong>ern Arizona, New Mexico, Coloradoand Oklahoma where sub-zerotemperatures are a yearly phenomenon.Literally hundreds of distinct forms ofcactus might yet be selected fromamong these, as well as fromChihuahuan, Sonoran and Majaveanendemics that stray beyond their subtropicalrange into this or that chilldesert valley.Yet, in spite of their diversity ofranges and forms, in spite of a relativeease of cultivation, rock gardeners findthemselves speaking furtively about thisglorious family of <strong>American</strong>wildflowers. Evidently there is somethingwrong with cacti. It is difficultto comprehend what might be wrongwith them as subjects for the rockgarden. After all, is the body of thecactus plant that much more succulentthan a sempervivum? Is its flowerany more showy, say, than that ofa lewisia? Its spines are only morepainful in degree than the spines ofa host of choice rock garden brooms,thistles and buns. Cacti are really nomore unfriendly than these, or a goodlynumber of other accepted alpines. Indeed,they are a good deal morefriendly than Aretian Androsaces,eritrichium and their ilk, that altogethershun our gardens with pathologicalobstinacy.The ambiguity and condescensiondisplayed by alpine gardeners towardscacti has resulted in an ironic twist:where in America is rock gardeningpracticed more extensively or with morestriking effect than in the desertSouthwest? Who can pass through ElPaso, Tucson, Phoenix, Las Vegas, LosAngeles — even Santa Fe — and notbe struck by the hundreds o fnaturalistic plantings featuring cacti artisticallyplaced among rocks and awealth of interesting desert wildflowersand shrubs that accompany them inthe wild? Of course the dryness andsubtropical climate in most of thesecities precludes the use of many conventionalrock plants in gardens there.But neither rocks nor gardens arelimited to tundra. Neither, in fact, arethe plants that most of us grow inour rock gardens. Cacti, too, it shouldbe remembered, are by no meanslimited to the southwestern desert.It is our contention that in spiteof persistent prejudices, the ARGS isa natural body to foster interest inthese plants and to serve as a repositoryfor information about them. No otherhoricultural organization on this continentcan boast larger numbers oftalented gardeners who are skilled indealing with difficult plant material.No other national horticulturalorganization in America has as its purposethe encouragement of naturalisticgarden plantings employing wild plantmaterial. No one is better suited thanalpine gardeners for the ordeal of coaxinga hardy cactus from seed tomaturity, and they can make a realcontribution by selecting superior clonesand compiling and disseminating informationon the culture of hardy cactiin cold climate gardens.The dryland rock garden is an ideal158

setting for cactus plants. Here they canmingle with lewisias, manzanitas, penstemonsand a welter of composites andbulbs just as they do in nature. Theindividual cactus is far more interestingwhen viewed in such a setting,among rocks and complementary,unrelated plants. Crowded too thicklywith their own kind, a cactus plantingmay end up resembling a rock concertmore than a rock garden. No sightin nature can impress a hiker morethan the sudden apparition of a solitarymound of cactus in full bloom. If youcan contrive this effect in the rockgarden, you can probably charge admission.While we readily admit that it isimpossible to recreate entire deserts ona city lot, we do maintain (and wehave proven) that it is possible to capturean essential part of the spirit ofthis fascinating natural complex. Thebalance of this article is a descriptionof the plant material apt for such anundertaking. Perhaps in another contextwe might detail the procedures forcreating an appropriate habitat for theplants.Which species of cacti are hardy,and how can they be grown? If welimit our scope solely to the membersof the family that grow north of theMogollon Rim in Arizona, east of theSierras as far as the Great Plains andcolder stretches of the Chihuahuandesert, the numbers of species availableto us is impressive. Cactus nomenclaturerivals the taxonomic confusion of Potentilla,Salix and Astragalus. Speciesnames especially are a bloody battlefieldfor botanists, now that a clearer conceptionof generic affinities has antiquatedthe clutter of micro-genera that onceconfounded amateurs. Botanists mayfret about whether some entity is worthyof specific, merely varietal or just"form" status, but the horticulturistmust necessarily apply a differentyardstick to judge its worth. Withoutworrying too much about specificnames, it is fairly easy to delineatethe broad outlines of certain groups,or complexes, of cacti that can be usedin the rock garden.Size is an excellent criterion to usein dealing with the more interestinghardy cacti. As often happens in thePlant Kingdom, two altogether unrelatedplants can resemble eachother closely in the eyes of a novicewhile different forms of the same speciesmay look vastly different. Sinceour art is more concerned with thehabit of plants than with their geneticrelationships, it is convenient to dealwith cacti on the basis of their habit:we will begin with the "ball cacti"— comprising many, distantly relatedplants — then discuss the cylindric"hedgehogs" (Echinocereus); concludingwith the much maligned PricklyPears (Opuntia). Since nature is thesupreme gardener, we will stress thenatural settings where we have seencacti growing. This can provide hintson how to grow them in the gardenand underscore the message of this article:rock gardeners owe it to themselvesto grow cactus.The "Ball Cacti"No better cactus can begin this accountthan the Mountain Ball Cactus,Pediocactus simpsonii. It is largelyrestricted to mountainous terrain athigher altitudes (in spite of itsridiculous generic name that means"Plain's Cactus") in almost every statewest of the Great Plains. It is the mostwidespread example of a group of cactithat almost never descend below fivethousand feet, in the south. They demanda rather mesic, temperate climateto grow at all. In the dry, intermountainranges of the West, this cactus can159

climb above 10,000 feet. While thisparagraph was being composed a temperatureof -52°F was recordedin a mountain valley west of Denverwhere Pediocactus simpsonii is especiallyabundant. Perhaps nowhere over itsrange does it grow as profusely ason the top of a nine-thousand foothigh plateau in western Colorado wherefor miles on end the exposed sandstonebedrock between islands of PonderosaPine and Gambel's Oak is a veritablesea of Pediocactus tangled in denseswards of Ericopsis Penstemons, phloxin variety, bright purple Alliumacuminatum, Townsendia glabella andselaginella. This species (as is so oftenthe case with cacti) actually comprisesa variable complex of forms. All aredensely armed with centimeter longspines so that the body of the cactusis invisible. Most forms grow singly,others form clumps. The spiny spherescan grow from a mere three inchesin diameter of the type variety intomonsters eight or more inches acrossin other forms. The loveliest form isundoubtedly the "Snowball Cactus", acommon variation in some localities,in which the normally amber spinesare of purest white.The flowers of the Mountain Ballare highly variable. The best formshave inch-wide chalices of rose whichopen widely and are fragrant. Cream,yellowish, flesh-colored and greenishtints predominate in the more westerlypopulations. This is the first hardy cactusto bloom in the garden, often openingits buds in March here in Boulder.Typically, it occurs among rocks andscant grass of the Ponderosa Pine beltof the Montane Zone. It will descendonto plains and valleys only in moisterregions where alkalis have been leached.In one valley in southern Wyoming,granite outcrops are studded withPediocactus at 8,000 feet elevation. Inearly June the steep, south-facingmeadows between these outcrops arefilled with dwarf sagebrush (Artemisiatridentata), many buttercups, andThlaspi montanum forming drifts ofwhite interspersed with the brillantblue patches of the local representativeof mertensia (M. bakeri? M. viridis?a M. lanceolata variety? Nothing keysout.) Bitterroots are just opening theirfirst buds as the Mountain Ball finishes,while directly opposite, on the northfacingslope, the Lodgepole Pine forestis dotted with calypsos.Pediocactus simpsonii var. robustioris the most distinctive race of the MountainBall. It forms giant, multi-headedclumps in restricted portions of thedry prairies in the <strong>North</strong>ern Great Basin.In this unusual race the spinesare blackish in hue. The impact ofa cluster of several six or seven-inchdiameter heads is striking year around,even if the flowers are less brightlycolored than those of its southernrelatives.A half-dozen more species o fPediocactus have been described fromrestricted ranges in the deserts of theSouthern Great Basin and NavajoanDesert. This austere landscape has beenso overgrazed and threatened by damming,electrical power plants andmining development that these impossiblyrare cacti are in real dangerof extinction. Most are adapted to extremedesert conditions or else occurin special habitats that are difficultto duplicate in gardens. Until these areavailable in seedling stock from responsiblenurserymen, it would be criminalto advocate the use of these endangeredplants in gardens.Coryphantha vivipara is even morewidespread and variable over most ofthe West than the Pediocacti. It extendsfurther south than any Pediocactus.How such a beautiful wildflower, still160

Coryphanthaviviparagrowing abundantly over such a vast,populated area, can remain without afitting common name is a mystery. Buddingcactophiles sometimes confuse itwith the Mountain Ball Cactus, but thetwo are really quite different in bothshape and spination. Although theflowers in both are produced at theapex of the stem (Coryphantha, in fact,means "flowering at the apex"), thoseof the Coryphanthas are usually twicethe size of the Mountain Ball's bloom,161

which they follow by as much as amonth in the garden. Coryphanthas mayhave over thirty, narrow petal-like segmentsin each flower, while in Pediocactusthe segments are blunt, much shorterand fewer in number. The flowers inthe former are generally much brighter,varying from pink to virulent magentasand vibrant purples. Although they areproduced on low plants, often halfhiddenin dense stands of Buffalo Grass,they can nonetheless make quite a showin nature. Coryphanthas generally prefermore alkaline conditions of openprairie at lower elevations but can climbwell over 6,000 feet even in the northernreaches of their range. They oftenbloom after the first rush of springflowers, joining in with a spectacularcanvas of eriogonums, Calochortus nuttallii,Lithospermum incision, Sphaeralceacoccinea and the ubiquitous rabbleof castillejas, astragalus and oxytropisof the West. Cattle have effectivelytrampled countless millions of theseplants out of existence in the last century.In pastureland they can oftenbe found only under fence wires, growingin pitiful rows not of their ownchoosing.The variation in the complex is almostridiculous. The name has beenused to lump varieties with incrediblydense, interlocking white spines (var.neomexicanus) that occur in thesouthern portion of its range; singlebarrel-like plants that can attain nineinches in height in the upper Mojavewith pale pink flowers and variablycoloredspines (varieties deserti androsea); and of course the thicklycaespitose plants (responsible for thename "vivipara") that produce dozensof offsets — resembling Sempervivumarachnoideum from a distance — thatabound in the high parks and on theGreat Plains.These forms and others all intergrade,so that the accurate determinationof varieties is difficult. Growingany of these from seed is a slowand tricky process, as the seed germinatesunevenly and matures at ratesto satisfy the most patient alpine gardeners.Unlike Pediocactus, which shedsits seeds from dry capsules promptlyafter ripening, Coryphanthas producea juicy, sour fruit that ripens late inthe summer and usually persiststhrough the winter on the plant. Asa result, it is easy to collect.Occuring over much the same rangeas the eastern varieties of Coryphanthavivipara is a similar ball cactus,Neobesseya missouriensis. This littlemammillary is more prominently tubercledthan even Coryphantha andhas sometimes been called the "NippleCactus" because of this. It, too, prefersthe Buffalo Grass prairie to mountainousterrain, but it is easily distinguishedfrom Coryphanthas growing nearbybecause of its flattened rather thanconeshape body and the bright redfruits that persist even longer than thegreenish or russet capsules of Coryphantha.The brownish or straw-yellowblossoms, with a darker central stripeon each narrow segment, are of coursequite different —• easily distinguishingthe plants when they are in bloom.Fabulously rare pink-flowered colonieshave also been reported in Montanaand Oklahoma, but we have never seenthem. The Nipple Cactus rarely growsin such dense stands as one often encounterswith the other Ball Cacti.One can easily overlook a plant infull bloom, and if one finds a smallcolony it is usually because one noticesthe bright red fruits contrasting withthe deep green body of a plant buriedin a clump of grass.The plants are small, usually onlythree inches across. Patriarchs sixinchesacross can be found where grow-162

Neobesseyamissouriensising conditions are optimal. It offsetssparingly in its northern forms, whichalso tend to be smaller. The southernforms of this cactus have sometimesbeen segregated under the name ofNeobesseya similis. This robust developmentoccurs from Oklahoma southwardand appears to be almost as hardyin cultivation as the northern form.The flowers are produced in an amazingprofusion over a much longer periodin the early summer than in the northern163

Al Fresco in PetropolisPeople who live in cities do not livethere because they dislike nature. Theflight to and from cities has little todo with horticulture. But most citydwellers,deprived of a naturallandscape, probably have an evengreater need for gardens than thosewho live in the suburbs or the country.Much of the beauty of our citiesis the direct result of a universal longingfor a green and picturesque environment.The aesthetic contributionof landscape architecture to the urbanscene equals or exceeds that of structuralarchitecture. Alfred Geiffert, Jr.,the landscape architect, said, "Asbeautiful as Charleston is architecturally,stripped of her gardens shewould lose much of her charm."Fortunately, the city-dweller can enjoynature even if he does not livein Edens like Charleston or Carmel.The beautiful parks of our concrete-andsteeliestmetropoli are proof of that.And for those who lack a neighborhoodpark, or who desire greater privacythan parks permit, there is always thechallenge of making one's own oasis,one's own Paradise, for appreciation,contemplation, release and fulfillment.An enormous literature, including aninfinity of magazine articles and many,many books, is devoted exclusively tothe urban garden. Many of the books,and a few of the articles, deal withsome aspects of urban rock gardening,in anywhere from a sentence to a fewpages. However, they yield little detailedinformation; the comments on rockgardens are, as a rule, brief andgeneralized. The articles that follow donot, of course, present a systematictreatment. However, they do depict theefforts of city rock gardeners to achievewhat we are all trying to do. Theadjustments they have made to cityconditions may be interesting orinstructive to those who are similarlysituated. Two of the authors have evenengineered a scree, with running water,indicating a willingness to go to whatthe average city gardener might considerdesperate efforts in order toachieve beauty. As many rock gardenersknow, and as these particular onestestify, the rewards of such labor aregreat indeed. — Ass't Ed.ALPINE NEWPORT NEWSNORMAN T. REALNewport News, VirginiaNorman Beal is a horticulturist workingfor the Virginia PolytechnicInstitute Extension Service in NewportNews, which has a population of 130thousand. In his small, townhouse gardennear the center of the city, hehas grown or is growing most of theplants mentioned.In the country a rock garden is often"lost" or, at least, of secondary interestamong the oaks, beeches, pines andvast lawns of a fifty acre residence.But in the city center, where buildinglots are small, it is easier and betterto display and enjoy up close the multitudesof small treasures available to165

us. Certain small, slow-growing ordwarf plants will thrive in every sectionof the nation.In southern Virginia, transplantednortherners often bemoan their inabilityto grow lilacs, rhododendrons, yews andother familiar landscape plants. Howlucky their visiting kinsmen considerthem when they see growing quitehaphazardly the incomparable CrepeMyrtle, Southern Yew, Live Oak,camellia and gardenia. Likewisetransplanted northern rock gardenersbemoan the death of imported saxifragesand heathers during our muggysummers instead of facing reality andselecting from the wealth of readilyavailable, hardy native and introduceddwarf plants. With these they can constructrock gardens that will be superb,even though different from those foundin Connecticut. The red winter matof Vaccinium vitis-idaea minor is notfor us; instead we have the equallybrilliant buns of Nandina domestica'Nana Purpurea Dwarf, starting theirfiery glow as early as September. Saxifrages,no; sempervivums and someechevarias, yes. Many regionallyoverlapping plants tie our gardens tothose of our <strong>North</strong>ern confreres,notably the dwarf conifers, the maplesand innumerable small creeping andblooming mats.The city rock garden should beenclosed by a fence or wall upon whichcan be grown non-invasive floweringvines. Clematis, Cross Vine (Bignoniacapreolata), and Trumpet Honeysuckle(Lonicera sempervirens) are good localchoices. A southern boundary fence willgive a northern exposure for plantspreferring it. If the soil is not welldrained,it should be made so witha goodly proportion of humus andcoarse sand mixed in. Ground-level rockgardens require back-breaking work,are monotonous to look at and harderto see. Raised beds or mounds alleviatethese problems. <strong>Rock</strong>s are not indispensableto rock gardening, but are greatlyto be preferred; but not your averagerock-hound's collection of one fromevery state and all colors of the rainbow.Decide upon one type and colorof rock and stick with it. It will notonly unify the garden, but appear tohave been there all along. To thosewho object that it is unnatural to placerocks in an area where none appearnaturally, I reply: Balderdash. It makesas much sense to apply that logic tohouses, in which case we would allbe living in trees and caves. However,each to his own taste.My preference is for the pale gray,water-rounded limestone rock thatabounds in the mountains of Virginia.Landowners in that area are oftendelighted to give away as many rocksas possible, and I, for one, am alwaysready to oblige. <strong>Rock</strong>s may be gradedinto sizes that can be comfortably movedby various assemblages of men, thus1-man, 2-man, and 3-man rocks. Thosesmall enough to be carried by childrenand most women are too small to makean impact and should be thrown back.When collecting, be picky. <strong>Rock</strong>s allthe same size and shape will look likepeas scattered upon a field. Of course,we can enhance the apparent size ofone by placing it high upon a moundof soil so that more of it appearsto be hidden than actually exists. Don'thesitate to place a nice rock into afinished garden at a later date. Afterdeciding where it belongs, carefully digout the soil, insert the rock, turn ituntil it presents its best aspect, thenfill in around it, tamping the soilfirmly. It will immediately look as ifit had been there forever.Sometimes a steeply sloping moundwill present problems of soil erosion.I've found that a mulch of shredded166

hardwood bark (stone-chips are lesslikely to harbor slugs,, fungus/diseasespores, and insects -—- Ed.), besidesbeing most attractive, will be proofagainst the heaviest downpour, althoughnot against the digging of squirrelsand racoons, as indeed nothing is.Everyone knows there are more of themin the city than the country, so wejust have to re-firm the soil after them.The small maples look exceedinglyat home in an alpine garden, and ifyou don't wish them to attain theirnormal height of up to twenty feet,they can easily be maintained at alesser size by judicious application ofthe secateurs. Most would agree thatthe natural-looking small gardens ofJapan would not look that way at allwithout the unnatural help of theshears. This is also an excellent wayto care for bonsai and use them toaugment the rock garden. Place themrandomly among your rocks and keepthe tops pruned as you would normallyduring the growing season. The trunkswill develop much faster than in a pot,and watering and other chores will bemuch simplified. Of course you canroot prune periodically as needed, andpot them up when desired for specialoccasions or effects. One of my mostdramatic "trees" is an old privet, eighteeninches tall, with a trunk as thickas your upper arm. Like all privets,it requires a lot of pruning and wouldnot meet a purist's qualifications, yetit arrests the eye. Another is a collectedScrub Pine (Pinus virginiana), witha twisting, sinuous trunk and layeredmounds of foliage. Too oriental? Sobe it.Most dwarf conifers thrive inthis area (excepting the true firs). Thebest are the dwarf Hinoki Cypresses,which never seem to be bothered byany pests. Most others do not longsurvive the predations of spider mitesunassisted. Forceful hosing down withwater knocks them off, and the littlecritters are so small it takes them thelongest time to crawl back on.In the South we are fortunate tohave a rich variety of dwarf broadleafevergreens to choose from. The peerof this group is Henry Hohman's selectionof Buxus microphylla compacta,which he named 'Kingsville'. It wantsto plod comfortably along at a half-inchannual growth rate. Those of you wholike to run with the hare for a whilecan speed it up to eight times normalwith periodic applications of liquidfertilizer (I use Peters 9-45-17) afterhot weather arrives to stay, discontinuingthem by late September. Frequentdrenching with water helps during thistime. Don't let its slow growth ratediscourage you from starting cuttings.True, a one-inch cutting will take someyears to appear in the field of vision;however, if you can gain access tolarge plants, take large cuttings. Mybest results were obtained by takingthem during the Twelve Days ofChristmas, growing them in darknessfor one to two weeks, then stickingthem under mist where roots magicallyproliferated within three weeks. Successwas in the range of 99 percent, whereassimilar cuttings in a Wardian caserooted much more slowly and in therange of 25 percent. Nandina 'HarborDwarf makes nice little groves as itproliferates from rhizomes. Minebloomed and fruited this past year,and the normal size berries lookedridiculously fat and pompous, perchedon their six-inch hosts. Satsuki Azaleas(the Japanese pronounce it "Satski")are great for small spaces. Naturallylow and spreading, they can be greatlyassisted by annual shearing near bloomingtime. As most flower buds arewell down inside the foliage, there willbe ample, indeed overwhelming, bloom167

after shearing. Shape them to matchtheir nearby companion rocks.Several dwarf Japanese Hollies (Ilexcrenata) are of interest. Two relativelynew forms look and feel as if carvedfrom stone. The male is 'Green Dragon',the female 'Dwarf Pagoda', the lattermore compact, both growing less thanfour inches a year. The I.e. 'Helleri'selection called 'Witch's Broom' hasbeen a disappointment, growing morevigorously and upright for me thanits parent. The yellow foliaged formof I.e. 'Helleri' provides a nice touchof winter color for those who likeyellow, although I prefer the dwarfgold Thread-leaf Cypress for pure gold.Pittosporum 'Wheeler's Dwarf makesa shining mound of bright green inshade. Abelia 'Edward Goucher', whiledwarf, needs periodic shearing to maintaincompactness. One of the best plantsfor shade is Sweet Box (Sarcococca),and its winter bloom is pleasantlyfragrant. Pieris japonica 'Pygmaea' isdelightfully miniature in all aspects;P.j. 'Bisbee's Dwarf, with reducedleaves, has a healthy pink winter color;P.j. 'Wada' is slower growing and morecompact than the species, has pinkblooms and pink winter leaves.Osmanthus heterophyllus 'Rotundifolius'with one-inch rounded leaves,and the even dwarfer 0. delavayi withholly-like leaves are both collectables.0. heterphyllus 'Variegatus' has crispwhite-margined foliage.Euonymus fortunei 'Minima' ('Kewensis')is a common landscape shrub,appearing box-like with tiny leaves. Itis most suitable for the rock garden.Rosmarinus officinalis 'Lockwood deForest' is a charming, twisted dwarfevergreen shrub, peppered in fall andwinter with stars of bright blue.Serissa foetida (Popcorn Plant),usually considered a houseplant, makesa stout-stemmed treelet in local gardens.The double-flowering form is morecompact than the species and isevergreen in normal winters. The tinyleavedHokkaido Elm, an Ulmus parvijoliaselection, is almost evergreen,shedding its mantle for a brief periodin late winter. With a growth ratesimilar to that of Kingville Box, itmakes a billowing, mounded littleshrub.A rock garden in the city? Yes!it's a natural.ALPINE NEW YORKCITYDR. ALAN NATHANSBronx, New YorkDr. Nathans is a retired biology andphysiography teacher of circa fortyyears. Currently he is a dedicated alpinegardener and an inveterate travelerseeking why a plant grows where itgrows — especially saxicole. flora.My active interest in rock gardensbegan in July 1972 while I was ona tour of the European continent. Ata rest stop near a peak in SwitzerlandI saw an alpine version of our nativebull thistle explosively thrusting a doublefloral head through the snow. Almostsimultaneously it was envelopedby a swarm of tiny insects from outof nowhere, a flower-to-fruit cycleerupting in a few minutes (or seeminglyso)!This display of dynamism had a pro-168

found influence on me. My determinationto pursue the mysteries of alpinehorticulture dates from that moment.But I have a thirty-two-foot byeighty-foot back yard in a brick andconcrete northeastern city at sea level.There is a temperature distribution of47 °F. in the spring, 63° in the fall,75° in the summer and 40° in thewinter, with a year-round average of54.5°. We rarely reach down to 20°in the winter; a bit more often, butstill rarely, we go up to the 90's. NewYork City has a year-round rainfallof 40.19 inches, with snow and frostamounting to 29.6 inches. There is morethan enough daylight with twelve hoursin the spring and fall, fifteen hoursin the summer, and a weak ten inthe winter. Wind offers little concernto the backyard garden, so surroundedis it by buildings.How then to grow alpines and rockgarden plants at sea level under suchclimate conditions? To answer thisquestion, I have spent six years instudy, built six different versions ofa free-standing rock garden (raisedbed), and travelled to eight Europeancountries. I have tested the nature ofsoil mix and mass, the form, heightand position of the raised bed, plantingdepth and positioning, nutritional additives,the watering cycle and winterprotection needs. I am still testing, butthe current version (about six feetwide, twenty feet long, and about twofeet high) has provided some answersto basic questions. Questions relatingto watering, nutrition, grooming andwinter protection are discussed in thefollowing paragraphs. A list of plantstested completes these notes.WateringAll other factors are secondary to~]the question of watering and drainage. [The very physical structure and constructionof the raised bed is totallypredicated on the manipulation ofwater.The site selected for the raised bedshould be either on a slight crest oron a gradient permitting constant watermovement, not in a depressed area.I first dig out the area to about eighteeninches below ground level, and fillthis excavation with a bottom layer ofthree inches of pea stone (bluestone,etc), pounded down, and the spaces filledwith course sand. Above this I placerock rubble in a vertical stance, andagain fill with pea stone and sand.Then, above this I scatter crushedunglazed red building bricks that act asslow release aquifers. At all levels, sandis filled in and watered down before thenext stratification.A three-inch layer of sand to actas a filter is then positioned. This layerwill also be an inducement to rapiddrainage. Above this sand layer goesthe planting medium. This consists ofa mix of two parts (two heaping shovelfuls)of sand and grit, one part ofrotted leaf mold, one part of mediumloam, eight ounces of dolomitic lime,four ounces of superphosphate, threeflat shovelfuls of course charcoal andtwo shovelfuls of finely chipped (1/4")bluestone.This soil combination, well mixed,is layered in as one builds up thevertical walls of the raised bed, usingsedimentary flat rocks. The rock wallhas a split bonding (each rock coveringthe crack between the two below it).Each stratum is carefully kept tiltedinward and down by firm insertionsof bits of rock chips between the rocks(for lateral water flow and air movement,and to insert wall plants). Thiscreates a funnel effect. There is nocementing of any rock.Counter to the common practice ofa slight inward plumb from the base,169

the plumb is kept true from top tobottom. It was found that such a strutureavoids the erosive effects of cascadingwater, permits the wall plants tobe freely pendulous, and encouragesair movement around them. It looksmore natural and is pleasing.The plants themselves are designedto catch water. As a result of eonsof Darwinian evolution, alpine plantshave developed survival characteristics.These include tightly overlappingrosette leaf patterns, slight or no internodalseparations, a wrinkled exterior,succulence, hairy protective coverings,etc. In the main, these devicesconserve or catch water in droplet ormist form.Watering of alpines in nature resultsfrom the passage of low clouds, condensationthat occurs when mists reachcritical night-time dew points, the slowrelease of snow melt, and drenchingsummer squalls. In the rock gardenthese natural actions can be approximatedby heavy mid-morning and midafternoonmistings, as well as by heavywaterings (with mist attachments) tosoak interior aquifers when required.These watering practices are dependenton the weather, especially thepresence of the sun. Watering shouldnever be done by the calendar, butshould depend on need. The wateringprogram should continue until frost setsin. The soil mass of the raised bedmust always have a reservoir of wateravailable.An automatic misting system mightbe hidden in the raised bed. This hasnot been tried.NutritionInitially, ideal growth conditionswere provided by fertilizers. The svelte,tight mounds and compact rosettesbegan rampant vegetative growth, withlong internodal spaces and few (if any)flowers. The saxifrages became looseand sprawling. They no longer resembledthose delightful little plants one seesin the mountains peeking out of snowor rocky places, where the alpineecology (a reduced level of nutrients,lower temperatures, and a shorter growingseason) permit little more than survival.Thus, to emulate these spartan conditions,over-feeding was abandoned andthe regular rich nitrogenous diet wasreplaced by small amounts of a slowrelease organic fertilizer. Offerings ofnitrogenous food became fewer andwere limited to early spring and latefall. A light, late-fall dolomitic-limedusting and a light sprinkling of bonemeal or superphosphate and potash inspring supplemented the nitrogen feedings.A raised bed should be positionedwhere plant or animal organic detrituscannot fall onto the soil, as these wouldundesirably increase the nitrogen intake.It should be out in the open,with no tree overhang, particularly notdeciduous trees. Open placement assuresthe raised bed of constant sun, all butthe north-facing areas receiving acreditable amount of sunlight. Openplacement also provides free air movementaround the growing area.Grooming<strong>Rock</strong> gardens appear to require lessgrooming than annual, perennial orvegetable gardens.A key technique is the use of afine rock mulch. Quarter-inch sieved,clean rock chips or gravel placed abouta half-inch thick over the bed cutsdown on surface evaporation andreduces capillarity from the interior.It also minimizes the compacting actionof rain, watering, and wind movement,and keeps roots cool. It reduces theneed for weeding almost to zero. A170

thicker mulch, about an inch, is carefullytucked under the cushion, rosetteand mat-forming plants. This reducesthe potential for contamination by bacterial,viral or fungus organisms, andkeeps the plants drier. The rock mulchprovides a convectional air flow to keepthe rock garden plants dry and warm,diminishes soil-splashing onto leavesand lets the plants look their prettiest.Why not pine needles, or otherorganic mulches? These add extranitrogen and increase the chances forinfection.In lieu of washed bluestone chippingone might use small cinders, or crushed,finely sieved slate. Black crushed slateseems to provide more convectional airmovement around the plants.The vertical rock walls of the raisedbed require grooming, i.e. the soil insertedin the crevices does need occasionalreplacement. Sod is set aside,inverted, and kept apart from the compostheap. Suitably sized plugs of sodare pressed firmly into the crevices.Their fibrous nature acts with a spongeeffect, gives body, and can providenewly-imbedded plants with a firm anchorage,and also protection for theirroots. When the plug breaks downit will supply a bit of decomposednitrogen. <strong>Rock</strong> ferns, campanulas, sedums,saxifrages and other plants arehappy with such moorings.To compensate for loss of sand asit sinks into the soil mass, leaf moldshould be mixed with an equal volumeof sand when it is replenished.Pruning to maintain compactness,removal of dying flower heads and deadleaves are recommended as part of thegrooming process.Winter ProtectionThe main thing is to achieve thewinter protection that the plants areaccustomed to in their native habitats.In true alpine condititions, plants survivehappily in the only slightly subfreezingtemperatures that prevail undersnow cover. The winter climate in NewYork City, where there is little or nosnow cover, certainly differs. In thecity occasional warm spells in winterleave plants unprotected and directlyexposed to fluctuating temperaturesgoing far below freezing, even downto zero. Winter rains, occasionallyheavy, also have a disastrous effectby eroding the soil as well as the snowcover. These devastatingly violent fluctuationsare partly the result of thefact that New York City's winterweather sometimes comes from Canadaand sometimes from the Gulf of Mexico.Furthermore, that very characteristicmorphological structure of alpines, thetap root, delving deep between therocks, must continue to be winterfunctionalat all times. It must drawwater from the normally slow butsteadily trickling snow melt above tomaintain turgidity, and to prepare forthat explosive spring need of nutrients,enzymes, and phytohormones for therapid flower-to-fruit survival cycle ofspring and summer. If there is no snowcover, the tap root may dry out fromlack of moisture. Dryness can resulteither from actual drying out of thesoil or from freezing of the soil todepths below tap-root level: the taprootssimply cannot "tap" the moisture,because it is frozen. Winter-long snowcover would prevent such deep subsurfacefreezing.The so-called winter rest is actuallycoupled with growth dynamics, and aslow vernalization, increasing in latewinter, is necessary to complete thecyclic demands of survival. Withoutwinter mulching and protective effort,such dynamics would be nonexistent.Prior to using any of the wintermulching techniques there should be171

a pruning back and grooming of anyrampant, straggly or dead growth. Thecushions, mounds and rosettes need tobe tightened up.Winter weather brings many specialproblems, e.g. soil and plant heaving(resulting from fluctuating temperaturesabove and below freezingpoint), sunburn of exposed plants, increasedsurface evaporation of waterfrom exposed soil, erosion and compactionby rains, destruction of plants bysquirrels burying or digging for theirsecreted nuts, and the danger of prematuregrowth brought on by inopportuneand untimely warm spells.In addition, an inherent physicaldrawback of the raised bed results fromits having a vertical surface on allfour sides. These vertical surfaces makeit easier for cold air to get into theinterior, damaging the roots of creviceplants. These wall plants must be protectedfrom wind, sun and freezing.Still another factor, not significanton a flat surface or in warmer climates,but profoundly so in alpine ecology,is the need for immediate availabilityof nutrients for that precipitous springgrowth. One should put down aboutan inch of well-granulated leaf moldon the first snow surface, followed byweather-proof winter mulching (stonechips) to keep it from being blownaway, leached out or disturbed. Whenspring temperatures permit bacterialbreakdown, a strong survival-growthfood supply is available.The following procedures are suggested.In late fall (November 1-15),a covering of Scotch Pine needles isscattered on the horizontal surface ofthe raised bed. The long very rigidneedles provide, by their support, amodicum of insulation, reduce erosion,and permit any early snows to filterthrough and lightly blanket the surface.It is at this stage that finely granulatedleaf mold is tossed over the top.Sometime in the first half of December(preferably after a snow deposit) ablanket of three to four inches of firmWhite Pine needles is placed over theScotch Pine-snow-mulch combination,on the top and along the sides. Thisis lightly tamped down. The verticalsurfaces will hold insignificant amountsof the white pine needles; thereforethese surfaces present a special need.It is anticipated that a greater volumeof snow will fall subsequently. Shortlyafter New Year's Day, discardedChristmas trees are picked up. Longbranches are lopped off and drapedintertwined over the vertical surfacesof the raised bed. The shorter branchesare positioned (intertwined) over thetop. The remaining bole of the treeis placed over the middle to add weightand prevent the wind from blowingthe tree branches away.An effective deterrent to squirrel tunnelingis the use of rose canes thatwere pruned in the fall. They are crosshatched over the top of the bed underthe evergreen branches.The removal of the mulches is donein stages. Circa February 15-28 theevergreen boughs are removed (but notthe rose canes). In the first week ofMarch most, but not all, of the Whiteand Scotch Pine needles are taken off.All of these chores are subject to variationsin the weather.PlantsAn effort was made to test the adaptabilityof particular alpine and rockgarden flora before final placement inthe raised bed. A special raised bed,situated in direct and constant sunlight,and with free air movement, was usedfor the test plants. This testing siteincluded, side by side, plants fromIsrael, China, Switzerland, Yugoslavia,Scotland, Greece, etc.172

Some parameters determiningsuitability for the rock garden includedrampancy, nodal growth, leaf size, diseaseresistance, flower production,beauty of foliage or form, ability togrow with controlled minimal feedings,etc. These tests usually lasted over atwo year growth cycle, and are stillgoing on for many plants.The list tested and discarded wouldbe lengthy, so only a limited numberof the successful plants are noted here.Plants for the top of the raised bed:Almost all forms of dwarf Narcissus,e.g. 'Chloris', 'Dainty'; Iris reticulata,I. danfordiae, I. cristata; Muscari armeniacum;Ornithogalum umbellatum;P uschkinia scilloides (libanotica);Dianthus plumarius and hybrids; Androsacesarmentosa; Arabis procurrens;Aubrieta columnae; Saxifraga sarmentosa;Armeria maritima; Anemonepulsatilla (Pulsatilla vulgaris); Aethionemasaxatile; Achillea taygetea;Muelenbeckia axillaris; Stachys byzantina;Penstemon hirsutus pygmaeus;Gypsophila aretiodes; Veronica spicata'Nana'; Iberis sempervirens 'Nana', /.pruitti; Potentilla alba, P. villosa;Primula japonica; and a number of varietiesof Calluna, Erica and hardy dwarfconifers.Plants for the vertical rock walls: varietiesof thyme; Saxifraga stolonifera;Campanula poscharskyana; Dryopteriserythrosora; Asplenium platyneuron;Phlox subulata; Sempervivum tectorum,S. t. calcareum, S. arachnoideum; Sedumewersii, S. acre; Ramonda myconi alba;small leaved varieties of Hedera helix.Plants for the border that mergeswith the patio or lawn adjacent tothe raised bed: Hosta tardifolia; Aspleniumebenoides; Athyrium goeringianum;Epigaea repens; Ajuga reptans,Bergenia cordifolia, B. stracheyi; Iristectorum, I. cristata; Iberis sempervirensand its smaller yellow Italian relative /.pruitti; Epimedium pinnatum; andEuonymus fortunei 'GracihV.ALPINE CHICAGOVAUGHN AIELLOChicago, IllinoisMr. Aiello, chairman of the Wisconsin-Illinois Chapter of ARGS, is a sculptorby vocation.I was born in Chicago. Some yearslater we moved to the suburbs, wherewe were surrounded by open prairiesand ungrazed wooded areas. It wasthere that I developed my interest innative plants. Some of them I stillkeep near me; they are such joys thatI would hate to be without them. Bythe time I finished high school mostof the prairie had been turned overto developers, and I moved back intothe city.With mv involvement in the arts,I quickly met Eldon Danhausen, whosehouse and garden have won much acclaim.I then met Ruth Tichy and RoseVasumpaur. The four of us have beengardening together and attending mostof the national ARGS meetings since1970. Since I did not have a garden173

of my own I just gazed at all thedifferent types of plants and soon hadan idea of which ones I preferred.When buying a house began to seempossible, I decided the site would haveto be within the limits of the cityat the time of the 1871 Chicago fire.This is quite near the heart of thecity now. I bought a Victorian brickrow house, built in 1884 on undevelopedvirgin prairie. In 1900, aCatholic church had bought the landsouth of the house and built a nunnery,school and church. The nunnery andschool have since been torn down, leavinga vacant lot for parking. This hasafforded full sun for the garden, itsbest asset. Another asset is the soil.It has not been moved since the lastglaciation. The glacier laid soil twoand a half feet thick on a bed ofpure lake sand going thirty feet clownto bed rock (at one time Lake Michiganhad covered this land), providing gooddrainage. The house took possessionof me on April Fool's Day, 1974.The garden could be only thirty-fivefeet by twenty-five feet, so I had toplan carefully. Any trees would haveto be on the north side so as notto interfere with the full sun. The alpineplants would be in the middle andon the south side. A few of the plantsI wanted would like a moraine andin full sun definitely would need theunderground water. As this would bea special construction, I decided towork other areas and see the effectsof the full sun. Later, because I thoughtit would interfere eventually, I movedone tree (Diospyros virginiana) thatI had driven all the way to southernIndiana for. I even moved the telephoneand electrical lines.The weather around Chicago isgreatly affected by Lake Michigan. Wehave our own micro-environment withinthat of the Midwest. We have the normalMidwest weather that created andmaintained the prairies, where the temperaturedrops in winter sometimes tominus fifteen degrees or lower withthe humidity near five percent. In summerthe temperature can be over ahundred degrees with ninety percenthumidity. In January we can have sixtydegree weather, then severe snowstorms. Spring arrives practically overnight.Autumn is usually magnificent,though sometimes we need rain. Withinthat context is Lake Michigan.What a difference it can make! Thedogwoods that flower so terrifically eastof Lake Michigan will not bloom westof it. The lake also moderates the dailytemperature, summer and winter. Eldonlives three blocks from the water, Ilive one-and-a-half miles away, whileboth Rose and Ruth live about fifteenmiles from the lake. A typical winterday is, for Eldon and me, about fifteendegrees; for Rose and Ruth about five.A typical summer day is, for Eldonand me, about eighty-two degrees; forRose and Ruth about ninety-eight. Thisis only because of the lake. Rose andRuth experience frost a good monthbefore Eldon and I do. But when heand I are hit with frost it usuallystays until the following spring. Awayfrom the lake, the temperature risesso high during the day and drops solow at night that Rose and Ruth havespring at least two and sometimes threeweeks before Eldon and me. Thismoderating influence of the lake givesme a milder winter, and allows meto grow plants that will not grow awayfrom the lake. The west side of LakeMichigan is even given a different zonerating from that of the Midwest area.Most of the native prairie plantsaround Chicago have been destroyed.However, I hunted and found a smallpiece of open woodland and broughtback some Phlox divaricata, Lilium174

canadense, Sanguinaria canadensis, arotted tree stump and a few other plantsfor a woodland area next to the churchgarage. I added a Canadian Hemlockmy mother had collected as a seedlingin Wisconsin. A friend who has a quakingbog on his property donated aLarix decidua and a group of Cypripediumcalceolus. A Hino-crimson Azaleaplaced under the hemlock has been thebest performer in the area. Several differentvarieties of primroses were added,along with a few forms ofAnemonella thalictroides. Sanguinariacanadensis multiplex was added andhas been divided several times for increase.Hepatica acutiloba and H.triloba americana along with Trilliumgrandiflorum and T. sessile were addedand have increased. A Trillium undulalatumcollected in the wild has survivedand flowered again. Seed was sent tothe ARGS seed exchange. The hepaticashave seeded also. Thalictrum kiusianumdoes very well and I have divided itfor our Wisconsin-Illinois Chapter plantsales. To make a woodland type soil,I collected pine needles, coffee groundsand tea leaves, then mixed them alltogether with peat moss and native soil.For three years I collected Christmastrees from the alley for this purpose.After spending the first year onremodeling the house and in soil preparation,I decided that several collectingtrips would have to be made. Istarted by visiting the garbage dumpin Door County in northern Wisconsinto bring back several clumps of Cypripediumcalceolus. From two trips to thelakeside resort of a friend outsideDetroit, I brought back many graniteboulders in a rented trailer. Fromanother trip to northern Wisconsin, Ibrought back limestone rocks. The nextspring I placed mail orders to SiskiyouRare Plant Nursery and Alpenglow <strong>Garden</strong>s.That is when the rock gardenstarted to take shape. One trip to NewYork with a stop at Walter Kolaga'swas disheartening as his nursery wasalready sold, but I stopped near Detroitfor more boulders. Our local Wisconsin-Illinois Chapter plant sales greatly addedto the variety of alpine plants. Butit was the summer trips with Eldon,Rose and Ruth to the annual ARGSconventions with their plant sales thatreally began to fill the garden. Thesetrips also took us to many nurseriesand we all brought back many choiceplants. I know of no sources for alpinematerial for many miles aroundChicago.In 1975, the four of us travelledto the Four Corners area of Colorado.I collected Geum triflorum (a realfavorite) and Erigeron pinnatisectus(the best-performing erigeron I haveseen, and it has produced seed). I collectedand am quite proud of Ipomopsis(Gilia) aggregata with its spike ofbrilliant red tubular flowers. This hasflowered every year in very sandy acidsoil; I also collected a few others thatoutgrew their space and have had tobe placed in other gardens. Since thisexperience, I have not added any morecollected material because it seems togrow too vigorously in the garden andI want more alpines anyhow.In April of 1976 I started themoraine. A large hole about two-and-ahalffeet deep by eight feet long andfive feet wide was excavated. Daily walksto a nearby old industrial area produceda large pile of discarded bricks. Theywere broken into small pieces and putinto the pit. Sand, rubble and soil werethrown over this and watered to settlethe mixture. Then I shaped the rubblemixture into a peak in the center sothe water could run down both sidesas I wanted acid and alkaline sides.A heavy sheet of metal enclosed invinyl was cut and laid on top of this175

form. The edges were cut so the waterwould drop into the rubble before itcould reach the surrounding scree area.Sand and large granite pebbles werethen laid down. A copper water pipedrilled with holes along its bottom surfacewas laid on the peak and connectedto the water system. The water wentdown both sides so I put down theappropriate soil mixtures on top ofthe pebbles. This was watered untilit all settled, but it had leaks. Themost common type of leak occurredwhere boulders sat too close to thewater pipe. Water finds the easiest pathand it would come up under the rock.By moving the rock and fill this wasstopped in the first week and it hasnot leaked since. I was then eager forplants that I could use in the moraine.In July, we went to Seattle for thefirst Interim International Plant Conference.Our first stop was Dickson'sNursery in Chehalis, Washington, whichwe had visited in 1970 and 1972. Thishusband and wife team are probablythe most hospitable gardenersanywhere. I acquired Papaver alpinumalbum, Aquilegia saximontana (whichhas provided many seedlings for Chapterplant sales and the <strong>1979</strong> ARGSconvention), a Gentiana acaulis type,eight different dwarf conifers, severalsaxifrages, Campanula cochearifoliaand its white form, and a Lewisia x'Edithae.' Potted plants bought at anursery are superior to mail orderplants.The ARGS tour of an estate gardenin Seattle brought me face to leaf withthe plant I had wanted most, Dryasoctapetala 'Minor.' While I was leaningover it, Lincoln Foster noticed my appreciationand mentioned where I couldacquire it, but added "It probablywould not do well in your area." Putnam'sPlant Farm provided the specimen.In Chicago, I planted it in screetype conditions and it has performedquite well. It has more than tripledin size and flowers from mid-May untilNovember. It is never more than threedays without a flower. Cuttings rooteasily in spring and early summer. Ihighly recommend it. Other plants acquiredat Putnam's included Sileneacaulis, Campanula dasyantha (pilosa),Phlox subulata ssp. brittonii rosea, Saponariacaespitosa and Asperula nitidassp. puberula. There were four of usbuying plants, so the car was quite fulland low to the ground. We also had anassortment of collected rocks. Once home,I began to plant the moraine. The nextspring saw a vastly increased floweringperiod. The 1977 ARGS meeting in ValleyForge, our Chapter plant sales, andraising seed from the ARGS Seed Exchangehave since increased that bloom.After two and a half years, I havenoticed that seedlings occur in themoraine more than in any other areaof the garden. This occurs only alongthe border edge with the scree. HereHutchinsia alpina, Asperula nitida ssp.puberula, A quilegia saximontana,Draba aizoides, Papaver alpinum,Erigeron pinnatisectus, Dianthus glacialisand Oenothera species seed freely.The only two that I have not hadto remove by weeding are the hutchinsiaand the asperula. In fact Imay have weeded the Alpine Poppiescompletely out. The plants that thrivein the moraine are few, but well worththe effort. They are Campanulacochlearifolia, C. dasyantha (pilosa), C.planijlora, Gentiana acaulis, G. decumbens,Androsace sarmentosa, Sileneacaulis, Phyteuma comosum, Haberlearhodopensis and Papaver alpinum (tolist the most successful). So I haveleft the moraine as it is and haveadded to the scree areas.I am fascinated by tight buns andthey occur only in the scree. It was176

suggested I add even more gravel andI did. It seems that the plants withstandour hot, muggy summers if they sprawlon a rocky surface, producing theirown shade to cover their root systems.The best of the scree plants are Armeriajuniperifolia in all its varieties,Asperula lilacijlora (which flowers allsummer until frost), Draba aizoides,D. rigida, Dianthus 'Mars' (a blood-reddouble), Lewisia cotyledon in severalforms, Asperula gussonei, Silene quadridentata.,Dianthus alpinus, Aquilegiabertolonii, Saponaria caespitosa, S.pumilio and S. x 'Olivana', not to mentionfive varieties of dryas and twovarieties of edraianthus. Oddly, severalE. pumilio have failed to make itthrough the summer here, while theyhave succeeded in another Chicago areascree. All in all, it is the scree thatproduces the healthiest plants and thebest performers in this Chicago garden.ALPINE HARTFORDE. LE GEYT BAILEYHartford, Connecticut<strong>Rock</strong> gardening in the city on ahundred square feet presents problemsof adjustment which you would nothave to make if you gardened on anacre or two. For example: the ninefeet between my house and theneighbor's driveway was ideal for ashady garden, but the household fuelhose had to be dragged through thisarea to the intake pipe at the backof the house. What to do?I dug a trench nine inches deep andthe width of a wheelbarrow from thestreet to the back of the house. Threerailroad ties and some flat rocks formedraised beds on either side of the trenchto accommodate the soil I had dugout. I filled the trench with leaf-moldand gravel. To my surprise, within afew years seedlings of Erinus alpinus,Viola labradorica, Hutchinsia alpina,and Draba aizoides began to appearin the gravel path. My greatest pleasurewas the appearance of many Lysimachiajaponica minutissimaseedlings in the gravel. The path, builtoriginally to accommodate the oilmanand his hose, has become an additionalgrowing area I did not expect.Not having a wall or crevice facingeast or north where I could grow lewisiasin a vertical position, I sank concreteblocks in a sunny position. Iput leaf-mold in the bottom of the holesand filled them with gravel well uparound the plants and edges of theblocks. I feed the plants with fish emulsionand thev grow beautifully.Mrs. Herbert Sheppard of Burlington Rd., Harwinton, Conn. 06791would like to buy or swap color forms of Asclepias tuberosa.Ill

DWIGHT RIPLEY—PLANTSMANH. LINCOLN FOSTER<strong>Fall</strong>s Village, ConnecticutAs an inadequate in memoriam I wouldlike to tell you a little about DwightRipley, a rare plantsman. He, and hislife-long friend, Rupert Barneby, wereawarded the <strong>American</strong> <strong>Rock</strong> <strong>Garden</strong><strong>Society</strong>'s Marcel LePiniec Award in1974, but unhappily Dwight Ripley diedon December 17, 1973 before the awardcould be presented.Dwight was born in London,England, October 28, 1908, to an<strong>American</strong> father and an Irish mother.His paternal forebears and relatives hadfor many years lived in Litchfield, Connecticut,as does still his cousin, S.Dillon Ripley, the Secretary of theSmithsonian. Dwight was christenedHarry Dwight Dillon Ripley, a cumbersomename he soon shortened toDwight, except occasionally, for partialconcealment, when he became in thetelephone book or ARGS membershiplist, H. D. D. Ripley.One knows little about his early yearsin England except from a few revealingreferences in his later writings aboutplants. For instance, I find this in mylittle red book — something I willrefer to on and off. This volume isthe bound copy of articles that Dwightwrote for the Alpine <strong>Garden</strong> <strong>Society</strong>during the 1930's and '40's — atreasured gift to Timmy and me fromRupert.He wrote in an account of a tripthrough Oregon in 1945:To the author there has always been somethingspecial about the Umbelliferae, or Parsleys,and a patch devoted to their culture wasbegun at the tender age of nine. Coriander,chervil, sweet cicely and fennel were at thattime accorded the lavish care I would probablybestow today on Kelseya uniflora, and aweek-end guest of my mother's was known tohave packed his bags precipitately after tastingone of my terrifying salads. Yet I'm wellaware that Ogden Nash spoke for the horticulturalworld when he wrote his immortaltwo-line poem:"ParsleyIs gharsley."As far as the rock gardener is concerned, theUmbelliferae (except for Seseli caespitosumand the South <strong>American</strong> Azorellas) are gharsleyindeed. ...This reminiscence may suggest thathis early attention was solely to edibleherbs. Far from it. From Rupert Ilearn that Dwight had fallen in lovewith plants as a small boy and bythe age of sixteen had committed tomemory the Latin names of all theBritish wildflowers listed in Benthamand Hooker's Manual.Dwight's father died when he wassix and his mother when he was twelve.At about that age he was sent by hisguardian, the family solicitor, to Harrowbut who knows what was expectedof him. It is likely that his devotionto the playing fields of that preparatoryschool was not the sort to prepare himfor any future Battle of Waterloo. Whilethere, enduring what must have beenin the 1920's a typical English boardingschool existence, he did meet a fellowstudentof congenial temperament,Rupert Barneby, who has since indicatedhis initial amazement atDwight's prodigeous knowledge ofplants with their Latin names. Thisfriendship endured a separation whileDwight went off to Oxford to pursuecourses in languages and Rupert offto Cambridge to steep himself in178

The Cliff House in Horam, Sussexhistory.During his years at Harrow, Ripleybegan experimenting at home with avariety of gardens. In Horam, Sussex,he had inherited his first rock gardenand a small greenhouse. As his experienceand enthusiasm grew so didhis imaginative innovations in horticulture.By 1935 there were specialsand-beds and water-gardens and threealpine houses, one of which containedthe still reknowned limestone cliff builtagainst a rear brick wall with a cantileveredglass roof and removable glasspanels on the front and sides. Youcan read of its continuing influencein Roy Elliott's accounts in the Alpine<strong>Garden</strong> <strong>Society</strong>'s <strong>Bulletin</strong>.Dwight's innovative structures wereprompted largely by his annual botanicalexplorations and collecting tripswith Rupert into remote areas of theMediterranean basin which began in1927. Many of these trips include foraysCrowboroughinto Spain until that country was closedoff by the Civil War.In preparation for these journeys,Dwight and his friend, Rupert, poredover botanical literature in a wide rangeof languages and studied rare plantsin herbaria. The record of these tripsand unusual plants discovered andrediscovered are to be found eloquentlyset forth in the pages of the AGS<strong>Bulletin</strong> from 1930 to 1948. He startedmodestlv with an article of three anda half pages titled "Some Plants ofSouthern Europe." He dives right in:"The following is a brief descriptionof Mediterranean plants now beinggrown in a cold greenhouse at Horam,in Sussex, the majority of which Ibelieve to be new to cultivation in thiscountrv."There are twenty-two plants preciselyand elegantly described, none of whichI believe, even today, are in generalcultivation. This first article was follow-179

ed by a longer one titled "Plants forthe Cold Greenhouse," this time describingtwenty-seven plants collected in<strong>North</strong> Africa, the south of Europe, andin California (and this provenance isprophetic.) As a sample of Dwight'sability to capture in words the essenceof a species let me quote from thisarticle:Astragalus coccineus. This is not only byfar the most sensational member of its genus,it is also one of the very finest alpines to befound anywhere in the United States; thoughmany may take exception to the epithet "alpine"as applied to a species of the highdeserts of California. It occurs here and therefrom Inyo County to the western edge of theColorado Desert, at an altitude of 3,000-8,000feet, growing for preference on apparentlybone-dry slopes almost devoid of vegetation,but with the soil quite damp a few inchesbeneath the surface, round the long, deeplyburrowing taproot. The leaves are clothed indense white silk (as are also the seed-pods),and from their snowy mats rise up in earlyspring, on short stems, the heads of comparativelyfew pea-flowers, nearly two incheslong, of intense scarlet. One's first glimpse ofthis plant is unforgettable, an excitement hardto match and harder still to communicate toothers. The finest specimens I ever saw weregrowing on the sides of a small canyon nearLone Pine, at the eastern base of Mt. Whitney,where the desert sand had not yet cededto the influence of the mountain conifers.There it was obviously happy, revelling in thedeep gravel that contained not a trace of humus— undisputed king of that particularcastle except for an annual Gilia or two anda bright red Castilleja, faint echo of its owninimitable splendour. It may be grown, notwithout difficulty, in a very deep pot filledwith granite chips and coarse sand, plungedto the rim in ashes; and the crown should beguarded from water as rigorously during thesummer as in the darkest days of winter.He rounds out the alphabetical paradeof plants from diverse areas with thisaccount:Statice (Limonium) asparagoides. This Staticeis a native of the sea-shore at Nemours,Astragalus coccineusR. Barneby180

in Algeria, whence it extends to a single pointjust over the Moroccan border; and its rarityis only equalled by its beauty. Would that onecould say the same of Nemours! For here indeedis a plague-spot, as hideous and profoundlydepressing as the drabbest of thoseSpanish fishing-villages which display for thepassing tourist, between the sea and the southernbase of the Sierra Nevada, their ownpeculiar horror. In order to reach the Staticeone has to pass the local slaughter-house,jumping lightly (handkerchief to nose) overthe gully that drains its unnameable foulnessesinto the bright waters of the Mediterranean.But there, waiting in the shadow,lurks the prize, a few young plants perchedwithin reach upon their steep escarpment ofred gypsum. The older plants are out ofreach: enormous black trunks sprawling andtwisting over the cliff's face, from which eruptat intervals the long leafless branches as fineas filigree and rimed with blue, more intricateeven than the fronds of Asparagus acutifolius.In reality they are composed of verymany minute branchlets, interminably dichotomous,covered all over with little cladodesof the same length as themselves. The basalleaves are small and ovate, dying away soonafter the branches begin their growth; theinflorescence is produced in August, and turnsout to be a generous panicle of cerise. Cuisin'splate of this Statice in the "lllustrationesFlorae Atlanticae" is among the most inspiredtours de force to be found in any of thegreat botanical works.One can forgive, I think, his flourish ofscholarship at the end.His next piece, titled simply "In theMediterranean", is a more leisurely accountof yet another journey withRupert Barneby, who is now officialphotographer. There are two ofRupert's superb photos illustrating Matthiolatricuspidata and Iberis candoleanaaccompanying the article.Dwight begins his essay:In January of last year, accompanied by myfriend Rupert Barneby, who took the photographsillustrating this article, I visited CapePalinurus, famed locality of the unique PrimulaPalinuri, lying more than eighty milessouth of Naples on the way to Calabria — aremote and undramatic promontory isolatedbetween stretches of mountainous coast,marked only by a little striped lighthouse anda cluster of fishermen's huts. Centola, perchedon a hill a short way inland, is the nearestvillage, and if you descend from here thePrimula is almost the first plant you see onarriving at the shore. It is worth the fivehours' journey from Salerno to witness thebizarre spectacle of an Auricula, so essentiallyalpine in appearance, growing down bythe very edge of the Tyrrhenian. The largeglandular rosettes, usually single, more rarelyseveral to the trunk, sit quite happily a fewfeet above the dark blue sea, listening, not tocow-bells or the chatter of excited spinsterson their first trip to the Engadine, but tofishermen's more ordinary talk and the musicof waves falling on a southern beach. Thearchdeacon of rock-gardening, who never sawthis plant in situ, describes it with what canonly be called genius as occurring on "limestonecliffs . . . where it lies baked and dustcoveredin the fine dry silt of the grottoes".In point of fact the Primula affects openbanks, so steep as to be almost vertical, of acurious orange-coloured sand, known technicallyas friable arenaceous tufa, which characterisesthis piece of coast and which I havenever seen elsewhere in the Mediterranean.But then the word "grotto" is irresistible.and ends:Returning home last summer, we stayed forseveral days in the Puy-de-Dome, prosaic yetto us exciting, while Rupert tracked downcritical Biscutellas among the scoriae of deadvolcanoes or in small granite gorges by theside of streams. A wind was blowing over thehigh plateaux, unbelievably cool after thestifling heat of Provence, and as we scuttledhappily from puy to puy, with the air becomingfresher and more bracing every day,we told each other that the Mediterraneanwas quite definitely overrated. That inn atCavaillon, for instance, had been beyond ajoke. And then, the mosquitoes. . . . Back inEngland, we revelled in the sight of lawnsand elm-trees, river-beds that ran with water,and the large grey clouds. Never again, wevowed, would we leave this paradise on earth.Two months later I found my friend poringover a road-map of Morocco. His bagswere almost packed, he said. It seemed therewas a Trachelium near Fez. . . .Again one can forgive his measuredthrust at Farrer.Then as a sort of final farewell tohis Old World explorations he has along piece called "A Journey ThroughSpain" about which he confesses:The following notes, to be frank, are nothingmore nor less than an expression of uncontrollednostalgia, a prolonged harping ona set of all too precise memories acquiredover a period of years spent in the moun-181

Cymopterus ripley R. Barnebytainous regions of Spain. ... It is the selfindulgenceof one who has been exiled far toolong —• almost a decade, in fact — from theleast understood and most arrogantly beautifulcountry in Europe.Yet in spite of more than a dozen visits tothe Peninsula, some lasting several months,there are still many sierras that I have nevereven glimpsed, or that remain in the mind'seye merely as intriguing contours seen inpassing from the train or bus, shapes of momentousindigo lying on horizons as cold andvirtuous as the seas's; the marble gorges ofYunquera, for instance, or dank Riopar withits caves and cataracts poised high above thewhite dust of Murcia. . . .The whole essay is a magnificentrecherche du temps perdu, erudite andbotanically precise but most fancifullystructured.From there on the pages of the AGS<strong>Bulletin</strong> record accounts of the Ripley-Barneby expeditions into the flora ofthe United States and adjacent Mexico.They had taken up residence in BeverlyHills, California in 1936. But we shallsee later that the beauty of the Mediterraneanworld still haunted them.Here in America was a new world,wide and inviting. Over the years thesetwo explorers chased down many aplant recorded only once years beforein diverse botanical publications. Andthey discovered a number of utterlynew and unknown ones. There are fivespecies in four different genera named"ripleyi" and several "barnebyana."'At the time of the early <strong>American</strong>explorations, the gardens and alpinehouses at the Spinney in Sussex werestill there to receive collected plants,though during the war they did receivesome damage from bombing. The receptionand care of the new plants fromAmerica, plus the management of theestablished collection under increasinglytrying circumstances was entrustedto the care of a series of gardenersunder the guidance of the elderW. E. Th. Ingwersen. Mr. Ingwersen,noted nurseryman and himself a plantexplorer, was a devoted admirer ofRipley's as is evident from the series of182

letters dispatched by him to Americarecounting the affairs at Horam. I havebeen privileged to read these Ingwersenletters and was told I might throw themaway after reading but they are toofascinating for such a fate. I have, therefore,sent them back to the present generationof Ingwersens for possible biographicaluse.Eventually it fell to the elder Ingwersen'slot to arrange for an auctionof the plant collection at the Spinney.This sale was carried out November12, 1951. I have a copy of the salecatalog with notes of prices given foreach lot, an amazing document. I canvisualize the formidable gathering ofnotable horticulturists of the Alpine<strong>Garden</strong> <strong>Society</strong> and others cagily biddingagainst one another. Prices rangefrom five shillings for Lot 108 containingBupleurum plantagineum, Sedumtuberosum and three others, allthe way to seven pounds, one and sixfor Lot 96 that included Lepidium nanum.,Salvia vivacea, Cyclamen creticumand three others.During their prolonged absences fromEngland and until Ripley's finaldisposal of the Spinney at Horam, thetwo friends made numerous botanicaltrips in the United States, primarilyin the southwest. They were frequentlybased in California and deposited theirherbarium specimens at the CaliforniaAcademy of Sciences there or at theNew York Botanical <strong>Garden</strong>. Ripley'selegant accounts of these explorations,with magnificent pictures by Barnebyare to be found in ten articles in theAlpine <strong>Garden</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>Bulletin</strong> from1940 through 1948.There are such titles as "TheLimestone Areas of Southern Nevadaand Death Valley", "Rarities ofWestern <strong>North</strong> America", "Utah in theSpring", "A Trip Through Oregon".These are all wonderful reading, fullof plants and their discovery. I can'tresist giving you just a brief sample.On the morning of June the 1st, 1945, Iawoke in a small, battered bedroom of theonly hotel in Mountain Home, Idaho, with afeeling of exasperation and one of those moderatehangovers half-way between a simpleheadache and the condition, described so accuratelyby S. J. Perelman, in which "partiesunknown seem to have removed one's corneasduring the night, varnished and replacedthem, and fitted one with a curious steel helmetseveral sizes too small." I had spent theprevious evening pounding a piano in a barfor the amusement of the local cowboys, andthese innocent souls, inflamed no doubt bythe novelty of my urban tempo after a lifetimeof "Home on the Range" and similarforthright compositions, had kept me well suppliedwith refreshments.But sleep, when I finally dragged myself tomy pallet, refused to come: all night long thecowboys tramped up and down the creakingstairs of the hotel or shouted happily to eachother in the corridors, while the less virileretired to their rooms to pass out, breathingpeacefully with the quiet, regular rhythm ofpneumatic drills. Shortly after dawn I fell intoa fitful doze, and at six-thirty, wide awakeand pondering on the world and its follies, Igot up and dressed.A little later a knock sounded on the door.It was my friend Rupert Barneby, lookingenviably crisp, with a stack of drying papersunder one arm and our camera and tripodunder the other. Together we descended tothe hotel cafe, where I forced my teeth tognash sullenly for a few minutes on somethingyellow accompanied by two slices of salt pork,and gulped down a large cup of coffee inpreparation for the day's collecting. By seveno'clock, armed with a thermos and some sandwicheswrapped in cellophane, we were in thecar and off. . . .Near the end of these years of <strong>American</strong>botanical explorations recorded inthe AGS <strong>Bulletin</strong> and in some <strong>American</strong>scientific journals, the two explorerssettled permanently in the United States,first at Wappingers <strong>Fall</strong>s, N.Y. There,on extensive outcrops of Hudson Valleyshales, they devised a large rock gardenand erected an alpine house where theygrew a continuing introduction of plantsfrom their annual pilgrimages acrossthe country and into Mexico. FromWappinger's <strong>Fall</strong>s came a few Ripley183