An 11-year-old Girl Who Has Left Leg Pain

An 11-year-old Girl Who Has Left Leg Pain

An 11-year-old Girl Who Has Left Leg Pain

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

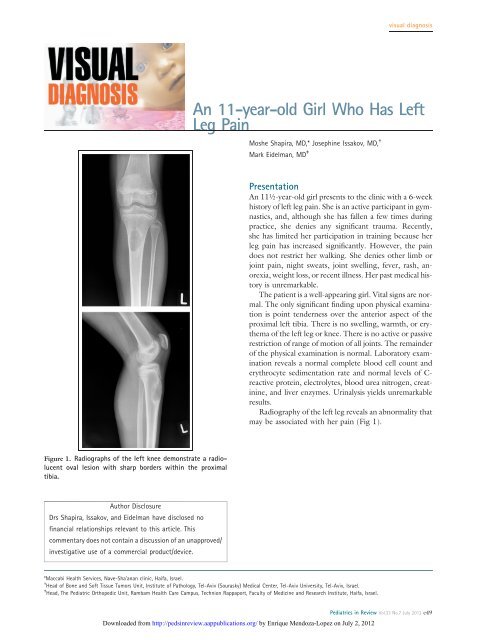

visual diagnosis<strong>An</strong> <strong>11</strong>-<strong>year</strong>-<strong>old</strong> <strong>Girl</strong> <strong>Who</strong> <strong>Has</strong> <strong>Left</strong><strong>Leg</strong> <strong>Pain</strong>Moshe Shapira, MD,* Josephine Issakov, MD, †Mark Eidelman, MD ‡Presentation<strong>An</strong> <strong>11</strong>½-<strong>year</strong>-<strong>old</strong> girl presents to the clinic with a 6-weekhistory of left leg pain. She is an active participant in gymnastics,and, although she has fallen a few times duringpractice, she denies any significant trauma. Recently,she has limited her participation in training because herleg pain has increased significantly. However, the paindoes not restrict her walking. She denies other limb orjoint pain, night sweats, joint swelling, fever, rash, anorexia,weight loss, or recent illness. Her past medical historyis unremarkable.The patient is a well-appearing girl. Vital signs are normal.The only significant finding upon physical examinationis point tenderness over the anterior aspect of theproximal left tibia. There is no swelling, warmth, or erythemaof the left leg or knee. There is no active or passiverestriction of range of motion of all joints. The remainderof the physical examination is normal. Laboratory examinationreveals a normal complete blood cell count anderythrocyte sedimentation rate and normal levels of C-reactive protein, electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine,and liver enzymes. Urinalysis yields unremarkableresults.Radiography of the left leg reveals an abnormality thatmay be associated with her pain (Fig 1).Figure 1. Radiographs of the left knee demonstrate a radiolucentoval lesion with sharp borders within the proximaltibia.Author DisclosureDrs Shapira, Issakov, and Eidelman have disclosed nofinancial relationships relevant to this article. Thiscommentary does not contain a discussion of an unapproved/investigative use of a commercial product/device.*Maccabi Health Services, Nave-Sha’anan clinic, Haifa, Israel.† Head of Bone and Soft Tissue Tumors Unit, Institute of Pathology, Tel-Aviv (Sourasky) Medical Center, Tel-Aviv University, Tel-Aviv, Israel.‡ Head, The Pediatric Orthopedic Unit, Rambam Health Care Campus, Technion Rappaport, Faculty of Medicine and Research Institute, Haifa, Israel.Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by Enrique Mendoza-Lopez on July 2, 2012Pediatrics in Review Vol.33 No.7 July 2012 e49

visual diagnosisDiagnosis: Bone Cyst of Proximal TibiaRadiography reveals a radiolucent oval lesion; it is mostlikely a unicameral bone cyst (UBC). There is no evidenceof a fracture. The patient is referred to a pediatricorthopedist for further evaluation.DiscussionDescribed by Virchow in 1876, a UBC (also known asa simple bone cyst, solitary bone cyst, or juvenile bonecyst) is a benign fluid-filled cavity found primarily in themetaphyseal region of the long bones, especially in skeletallyimmature children. This type of cyst tends to expandand weaken the bone, thereby predisposing it to a pathologicfracture. (1)(2) UBCs appear more frequently inmales than in females (2.5:1), and occur primarily in patientsunder age 20 <strong>year</strong>s (85%), with a peak incidenceat age 10 <strong>year</strong>s. (1)(3) This lesion accounts for 3% ofbiopsied bone tumors. Typical cyst locations include thehumerus, femur, tibia, and fibula. (2)(3) Less commonlocations include the calcaneus (2%–3% of cases), (2)distal radius, (4) and spine. (5)Etiology and PathogenesisThe cause of formation of a UBC is unclear, but theoriesinclude venous obstruction, development of an intraosseoussynovial cyst, dysplastic bone formation in responseto trauma, and localized failure of ossification during a periodof rapid growth. (1)(2)(3) The fluid within the cystcontains oxygen-free radical scavengers, prostaglandins,interleukin-1, and proteolytic enzymes that cause bone resorption,thereby contributing to the formation andgrowth of the cyst. (1) Microscopic examination of thecyst walls reveals primarily fibrous tissue with occasionalgiant cells. (1)(2)Clinical and Radiologic FeaturesThe UBC usually is asymptomatic and is detected oftenby incidental radiographic imaging of a limb for reasonsnot related to the cyst, such as minor trauma or limp.<strong>An</strong>y associated pain may be due to a pathologic fracturethrough the cyst or to microfractures not yet detectedby radiograph.On radiograph, the bone cyst appears as a round orovoid lucent lesion with an overlying thin, expanded corticalbone. Occasionally, when there is a fracture, a fragmentof the cyst wall appears within the fluid cavity, evident asa “fallen leaf” radiographic sign. (1)(2) Computed tomographyand magnetic resonance imaging will show the lesionto be fluid filled with a thin enhancing wall, but are oftennot necessary for diagnosis due to the characteristic appearanceof UBC on plain radiographs. Sometimes a few septationsare present. (2)Seventy-five percent of patients who have UBC presentwith a pathologic fracture. (6) Although the proximalmetaphysis is the classic location of most UBCs, therehave been reports of epiphyseal involvement. Ovadiaand associates (7) reported eight children with a medianage at diagnosis of 8.4 <strong>year</strong>s having bone cysts crossingthe growth plate. All children had more than two pathologicfractures; seven patients had growth disturbancewithout functional impairment.A UBC is defined as active if the cyst has increased inlength or width by 25% in serial radiologic studies, if thepatient has functional pain, if pathologic fractures appearwithout resolution of the cyst, or if the cyst is associatedwith cortical thinning (impending fracture). (6) In addition,a cyst is considered active if it has close proximity tothe epiphyseal plate, and is considered latent if it is >0.5 cmdistal from the physis. (6) Wilkins states that it is radiographicallydifficult to assess the current stage (growthversus involution) of the cyst at the time of diagnosis,a status that has implications regarding treatment andpossible complications. (1)Differential DiagnosisThe differential diagnosis for UBC includes an aneurysmalbone cyst, which is a benign osteolytic boneneoplasm characterized by expansive hemorrhagic,lobulated tissue arising in bone, and fibrous dysplasia,which is a benign disorder characterized by presence ofintramedullary fibro-osseous tissue that arises in the diaphysis.(6)TreatmentConservative management with close outpatient followupis the treatment of choice for the asymptomatic,physically active child who has a small cyst with thickenedwalls (asymptomatic UBC), because chances aregood that the cyst is in its involutional stage and willsoon disappear. (1)(3) However, if there is increasedrisk for a pathologic fracture through the thin cortex,treatment should occur to prevent fracture and possiblecomplications, such as residual skeletal deformity. (1)(3)Sites of particular concern are lesions in the proximal femurand the dominant throwing arm of athletes, due tothehighstressesattheselocationsandanelevatedriskof pathologic fracture. If presentation involves a pathologicfracture, fracture treatment occurs first, reservinge50 Pediatrics in Review Vol.33 No.7 July 2012Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by Enrique Mendoza-Lopez on July 2, 2012

visual diagnosisFigure 2. Axial and sagittal computed tomographic sectionsof left leg confirming UBC morphology.treatment of the cyst for those that persist after fracturehealing.Treatment options are (1) percutaneous aspiration andlocal corticosteroid or autogenous bone marrow injectionFigure 4. <strong>Left</strong> leg radiograph confirming surgical filling of UBC.Figure 3. Histology of UBC. The cyst wall is composed offibrous membrane (black arrow) bordered by bony trabeculae.Fibrin-like material and a few osteoclast-like giant cells arepresent within the cyst (red arrow).and (2) open curettage and bone grafting (autografting,allografting, or use of an artificial bone substitute suchas calcium sulfate). A new modified procedure consistingof minimally invasive curettage, ethanol cauterization,disruption of the cystic boundary, insertion ofa synthetic calcium sulfate bone graft substitute, andplacement of a cannulated screw to provide drainagehas been described recently. This operative procedureshowed the highest radiographic healing rate in comparisonwith the other methods discussed. (3) Donaldson,in a review of treatment options, states that corticosteroidinjection is the only evidence-based treatment for UBCs,but treatment strategies that include opening the medullarycanal, disrupting the cyst wall, and filling the lytic defectwith a bone substitute may be preferable; however,evidence is still lacking. (8)Successful healing of a UBC after surgical interventionas judged by radiograph ranges from 29% to 100%. Complicationsinclude physeal injury and cyst recurrence.Children who received instrumentation as part of theirtreatment eventually require implant removal. (3) Longtermclinical and radiographic follow-up is recommended,because recurrence of UBC has been reported in 18% to88% of patients at 6 months to 7 <strong>year</strong>s after the initialDownloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by Enrique Mendoza-Lopez on July 2, 2012Pediatrics in Review Vol.33 No.7 July 2012 e51

visual diagnosistreatment. (3) Subsequent fracture after surgery is anothercomplication and can affect a child’s quality of life adversely;a child may avoid physical activities for fear ofcausing a fracture. (1)Patient CourseBased on the clinical examination and the radiographic picture,the diagnosis of UBC was established and the patientwas asked to restrict physical activities. She returned 3months later complaining of pain, even without physicaleffort. Computed tomography demonstrated a hypodenselesion with a sclerotic border measuring 22 52 21 mmlocated in the metaphysis (Fig 2). A repeat radiograph ofthe leg showed a slight increase in the cyst’s size withoutevidence of an obvious pathologic fracture. The patientunderwent cyst curettage with bone grafting. Pathologicexamination confirmed the diagnosis of UBC, showingthat the wall of the cyst was composed of fibrous membranesbordered by the bony trabeculae. Fibrin-like materialand a few osteoclast-like giant cells were seen focally as well(Fig 3). The postoperative period was uneventful. Two<strong>year</strong>s later, the patient no longer has leg pain and has returnedto full physical activities. A follow-up radiographconfirmed filling of the cavity without complications(Fig 4).Summary• Unicameral bone cysts (UBCs) in children usually areasymptomatic. Most UBCs are discovered whena radiograph is performed on a child who has hadaccidental trauma to a limb.• Symptomatic cysts typically present with pain, oftenthe result of pathologic fracture through a large cystor occult stress fracture within the thinned cortexaround the cyst.• Simple radiography is the best method for detectingsuch cysts, which typically are located within the longbone (femur, tibia, fibula, humerus), but can appearelsewhere.• Cysts typically appear in the proximal metaphysis, butsome involve the epiphysis and growth plate, therebyaffecting bone growth.• If clinically necessary to confirm the diagnosis,computed tomography or magnetic resonanceimaging can delineate the cyst better or demonstratean occult fracture.• For the asymptomatic UBC, close follow-up is therecommended course of action. However, surgicalintervention by corticosteroid or autogenous bonemarrow injection or open curettage with bonegrafting is recommended if the cyst is symptomatic,carries an increased risk for pathologic fracture(weight-bearing bone or dominant arm of a throwingathlete), or shows signs of an impending pathologicfracture.• Clinical and radiographic follow-up is recommendedafter surgical intervention, because UBC recurrenceafter initial surgery is reported to occur in18% to 88%of patients.References1. Wilkins RM. Unicameral bone cysts. J Am Acad Orthop Surg.2000;8(4):217–2242. Schwartz D. <strong>An</strong> <strong>11</strong>-<strong>year</strong>-<strong>old</strong> boy with ankle trauma: unicameralbone cyst of the calcaneus. Pediatr <strong>An</strong>n. 2009;38(3):132–134,1343. Hou HY, Wu K, Wang CT, Chang SM, Lin WH, Yang RS.Treatment of unicameral bone cyst: a comparative study of selectedtechniques. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(4):855–8624. Cohen N, Keret D, Ezra E, Lokiec F. Unusual simple bonecyst of the distal radius in a toddler. Isr Med Assoc J. 2002;4(2):137–1395. Ha KY, Kim YH. Simple bone cyst with pathologic lumbarpedicle fracture: a case report. Spine. 2003;28(7):E129–E1316. Ortiz EJ, Isler MH, Navia JE, Canosa R. Pathologic fractures inchildren. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;432(432):<strong>11</strong>6–1267. Ovadia D, Ezra E, Segev E, et al. Epiphyseal involvement ofsimple bone cysts. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23(2):222–2298. Donaldson S, Wright JG. Recent developments in treatment forsimple bone cysts. Curr Opin Pediatr. 20<strong>11</strong>;23(1):73–77Suggested ReadingGereige R, Kumar M. Bone lesions: benign and malignant. PediatrRev. 2010;31(9):355–363e52 Pediatrics in Review Vol.33 No.7 July 2012Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by Enrique Mendoza-Lopez on July 2, 2012

Articlegastrointestinal disordersConjugated Hyperbilirubinemia in ChildrenDavid Brumbaugh, MD,*Cara Mack, MD*Author DisclosureDrs Brumbaugh andMack have disclosedno financialrelationships relevantto this article. Thiscommentary does notcontain a discussion ofan unapproved/investigative use ofa commercial product/device.Education Gaps1. Awareness of telltale signs and performance of appropriate diagnostic testing canhelp clinicians identify neonatal cholestasis in time to ameliorate its potentiallycatastrophic outcomes.2. The success of the Kasai procedure to restore bile flow is directly related to patient age:at less than 60 days after birth, two-thirds of patients benefit from the procedure;however, at 90 days after birth, chances for bile drainage diminish markedly.Objectives After completing this article, readers should be able to:1. Understand the metabolism of bilirubin, the differences between conjugated andunconjugated bilirubin, and the relationship of conjugated hyperbilirubinemia tocholestasis.2. Delineate the causes of cholestasis in the newborn and know how to evaluate thecholestatic neonate.3. Manage the infant who has prolonged cholestasis.4. Understand the causes of conjugated hyperbilirubinemia in the <strong>old</strong>er child andadolescent and know how to assess children who have conjugated hyperbilirubinemia.IntroductionCentral to human digestive health are both the production of bile by hepatocytes and cholangiocytesin the liver and the excretion of bile through the biliary tree. By volume, conjugatedbilirubin is a relatively small component of bile, the yellowish-green liquid that alsocontains cholesterol, phospholipids, organic anions, metabolized drugs, xenobiotics, and bileacids. In most cases, the elevation of serum-conjugated bilirubin is a biochemical manifestationof cholestasis, which is the pathologic reduction in bile formation or flow.Complex mechanisms exist for the transport of bile componentsfrom serum into hepatocytes across the basolateralAbbreviationscell surface, for the trafficking of bile components throughthe hepatocyte, and finally for movement of these bile componentsacross the apical cell surface into the bile canaliculus,AIH: autoimmune hepatitisALT: alanine aminotransferasewhich is the smallest branch of the biliary tree. From the bileAST: aspartate aminotransferasecanaliculus, bile then flows into the extrahepatic biliary tree,A1AT: alpha-1 antitrypsinincluding the common bile duct, before entering the duodenumat the ampulla of Vater (Fig 1). Isolated gene defectsBA: biliary atresiaBRIC: benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasisin proteins responsible for trafficking bile components canBSEP: bile salt excretory proteinlead to cholestatic diseases.CDC: choledochal cystERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatographyGGT: gamma glutamyltransferaseMCT: medium chain triglyceridesMRCP: magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatographyPFIC: progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasisPN: parenteral nutritionPSC: primary sclerosing cholangitisDiagnosisUnconjugated bilirubin is the product of heme breakdown,and this molecule, poorly soluble in water, is carried in thecirculation principally as a water-soluble complex joined withalbumin. Unconjugated bilirubin is then taken up into hepatocytes,where a glucuronic acid moiety is added, renderingthe conjugated bilirubin water soluble. Conjugated*Digestive Health Institute, Children’s Hospital of Colorado, University of Colorado <strong>An</strong>schutz Medical Campus, Denver, CO.Pediatrics in Review Vol.33 No.7 July 2012 291

gastrointestinal disordersconjugated hyperbilirubinemiaFigure 1. Biliary drainage with magnification of portal triad. (Courtesy of Robert E. Kramer, MD.)hyperbilirubinemia is defined biochemically as a conjugatedbilirubin level of ‡2 mg/dL and >20% of the totalbilirubin. There are two commonly used laboratory techniquesto estimate the level of conjugated bilirubin. Thefirst uses spectrophotometry to measure directly conjugatedbilirubin. The laboratory may also estimate a “direct”bilirubin, which reflects not just conjugated bilirubin butalso delta-bilirubin, which is the complex of conjugatedbilirubin and albumin. Hence, the “direct” bilirubin willtend to overestimate the true level of conjugated hyperbilirubinemia,and in neonates is less specific for the presenceof underlying hepatobiliary disease. (1)With the exception of Rotor and Dubin-Johnson syndromes,discussed later in this article, the elevation ofserum-conjugated bilirubin reflects cholestasis. The presenceof cholestasis may be a manifestation of generalizedhepatocellular injury, may reflect obstruction to bile flow atany level of the biliary tree, or may be caused by a specificproblem with bile transport into the canaliculus. Systemicdisease leading to hypoxia or poor circulatory flow also canimpair bile formation and lead to cholestasis.Recognition of the Cholestatic NewbornOwing to immaturity of the excretory capability of theliver, the newborn is particularly prone to the developmentof cholestasis. The challenge for the primary care clinicianis prompt recognition of the cholestatic infant. Observationof stool color is a necessary component of the initialassessment, because acholic stools represent significantcholestasis. Furthermore, hepatomegaly, with or withoutsplenomegaly, often is identified in the setting ofcholestasis.292 Pediatrics in Review Vol.33 No.7 July 2012

gastrointestinal disordersconjugated hyperbilirubinemiaforms of BA. The embryonic form of BA, which is associatedwith other congenital anomalies such as heterotaxysyndrome and polysplenia, accounts for w15% to 20%of BA.The acquired form of BA is far more common (w85%);the etiology of this disease is unclear. The pathophysiologyof acquired BA is that of a brisk inflammatory response involvingboth the intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts. Theducts are destroyed gradually and replaced with fibrous scartissue. The lumen of the bile duct is eventually obliterated,and normal bile flow is impaired, leading to cholestasis.Infants who have acquired BA typically are asymptomaticat birth and develop jaundice in the first weeks afterbirth. Typically, they feed well and thrive. As the bile flowdiminishes, the stool color loses its normal pigmentationand becomes acholic, or clay-colored. The finding ofacholic stools in the setting of a jaundiced newborn shouldprompt expedient evaluation for BA. Light-colored stoolsmay not be appreciated by the inexperienced parent,and the stool should be examined by the primary care providerto assess pigmentation.In Taiwan, which has one of the highest incidences ofBA in the world, a universal screening program providesparents with a stool color card on discharge from the newbornnursery (Fig 2). At 1 month of age, the parents returnthe stool card to their provider after marking the picture ofthe stool color that most closely resembles the infant’s stool.The universal screening program has led to improvement ofearly detection of infants who have BA, which has resultedin dramatic improvement in surgical outcomes. (4)Evaluation for BA includes abdominal ultrasonographyto rule out other anatomic abnormalities of the commonbile duct, such as choledochal cyst (CDC), and to identifyanomalies associated with the embryonic form of BA.A liver biopsy often is performed, and histopathologicfindings consistent with BA include bile ductular proliferation,portal tract inflammation and fibrosis, and bile plugswithin the lumen of bile ducts. The g<strong>old</strong> standard in confirmingthe diagnosis of BA is the intraoperative cholangiogram,which shows obstruction of flow within a segmentor the entirety of the extrahepatic bile duct.A Kasai portoenterostomy is then performed in an attemptto reestablish bile flow. This operation entails excisionof the fibrous bile duct followed by anastomosis ofa loop of jejunum to the base of the liver in a Roux-en-Yfashion. The success of this surgery, which is the restorationof bile flow to intestine, is directly related to the age of thepatient. Early Kasai procedure, defined as

gastrointestinal disordersconjugated hyperbilirubinemiapoor weight gain, ascites, acholic stools, and vomiting.Ultrasonography typically reveals ascites and fluid aroundthe gallbladder. Bile-stained ascitic fluid is a hallmarkfinding. The treatment of both of these conditions involvessurgical intervention.Stagnant flow of bile leading to cholestasis is seen oftenin the setting of intestinal disease and parenteral nutrition(PN) in the neonate. Precipitation of cholesterol and calciumsaltswithinbilecanresultintheformationofsludge.Bile sludge can be detected by ultrasonography. Whensludge builds up and leads to biliary obstruction and the developmentof cholestasis, the patient is said to have inspissatedbile syndrome. Inspissated bile can be managedconservatively with ursodeoxycholic acid, a bile salt that actsas a choleretic agent to promote bile flow. Because inspissatedbile syndrome can mimic biliary atresia, the diagnosissometimes is made at the time of intrahepatic cholangiogram,and saline flushes of the biliary tree by the surgeon canprovide the definitive therapy. The use of third-generationcephalosporin antibiotics, in particular ceftriaxone, has beenassociated with the formation of bile sludge in newborns.InfectionsNeonatal cytomegalovirus infection,vertically acquired from themother, is the most common congenitalinfectious cause of neonatalcholestasis. <strong>An</strong>y of the conditionsformerly identified as the “TORCH”family of infections (toxoplasmosis,rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpesvirus,syphilis) can lead to a similarpattern of cholestasis and growthrestriction. Acquired infections afterbirth can lead to cholestasis, inparticular Gram-negative infectionsassociated with urinary tract infectionsand sepsis, because hepatic bileflow is very sensitive to circulatingendotoxins.The characteristic finding on liver histology is paucity ofbile ducts. The clinical course of liver disease in infantswhohavealagillesyndromeishighlyvariable,withsomechildren experiencing a gradual improvement in cholestasisin childhood, whereas others progress to cirrhosis, requiringliver transplantation in childhood. Infants born withTrisomy 21 also are at increased risk for development ofa paucity of intrahepatic bile ducts; however, this situationusually is very mild, with resolution of cholestasis in infancy.Cystic fibrosis is another genetic disorder that canpresent with neonatal cholestasis and often is associatedwith meconium plug syndrome. Early diagnosis is aidedby the availability in all 50 states of newborn screeningfor cystic fibrosis by measurement of immunoreactivetrypsinogen levels.Along the apical surface of the hepatocyte, there arespecific transporter proteins that are responsible for trafficof bile components into the bile canaliculus (Fig 3). (5)Defects in these proteins are associated with cholestaticdisease. For instance, a mutation in the gene coding forbile salt excretory protein (BSEP) interferes with bile salttrafficking into the canaliculus, leading to reduced bileflow and the toxic accumulation of hydrophobic bile acidsGenetic DisordersAlagille syndrome is an autosomaldominant mutation of the Jagged 1gene on chromosome 20. There isvariable penetrance of this mutation,which can lead to abnormalities ofthe liver (cholestasis), heart (peripheralpulmonary stenosis), skeletal system(butterfly vertebrae), kidneys,and eyes (posterior embryotoxin).Figure 3. Canalicular membrane surface proteins, their substrates, and knownassociations with pediatric disease. (For a recent review, see Wagner M, Zollner G,Trauner M. New molecular insights into the mechanisms of cholestasis. J Hepatol.2009;51:565–580.)Pediatrics in Review Vol.33 No.7 July 2012 295

gastrointestinal disordersconjugated hyperbilirubinemiawithin hepatocytes. This mutation produces the clinicalphenotype of cholestasis and pruritis in the first <strong>year</strong> afterbirth, a condition known as PFIC2.A defect in the gene coding for FIC1, another canalicularsurface protein, produces the clinical phenotypePFIC1, which, in addition to cholestasis, can present withdiarrhea and growth failure. Pruritis, a dominant clinicalfeature of both PFIC1 and PFIC2, typically is not problematicuntil after 6 months of age.PFIC3 is a syndrome caused by a defect in the genecoding for the transporter MDR3, which is responsiblefor phosphatidylcholine secretion into the bile canaliculus.The onset of cholestasis is variable in PFIC3 but typicallyoccurs later than in PFIC1 and PFIC2. In contrast toPFIC1 and PFIC2, which are featured by a GGT levelin the low or normal range, the GGT in PFIC3 is elevated.Metabolic DisordersA range of metabolic diseases can present initially as cholestasisin the newborn period and are associated withgene mutations in most cases (thus, these diseases couldalso fall under the category of genetic disorders). Persistentjaundice in the newborn period is one of the earliestpotential clinical manifestations of alpha-1 antitrypsin(A1AT) deficiency, a defect in the “ATZ” molecule thatresults in abnormal accumulation of A1AT in the endoplasmicreticulum of hepatocytes. The abnormal retentionof A1AT within the hepatocyte leads to abnormalbile formation and secretion.Inborn errors of metabolism, which include disordersof fatty acid oxidation, tyrosinemia, and galactosemia,among others, can present in the neonatal period with aspectrum of liver disease that includes cholestasis. Finally,bile acid synthesis defects often present with neonatal cholestasis.As the production of bile acids from cholesteroland their subsequent export into the canaliculus are therate-limiting steps in bile flow, defects in a number of enzymaticsteps within this pathway result in abnormal bileacid synthesis and cholestasis. Bile acid synthesis defectsgenerally can be treated effectively by oral bile acidsupplementation.EndocrinopathiesCongenital endocrinopathies must be considered in thedifferential diagnosis of neonatal conjugated hyperbilirubinemia.Neonatal cholestasis is a well-recognizedmanifestation of congenital hypothyroidism. Congenitalpanhypopituitarism is manifested by deficiencies in cortisol,growth hormone, and thyroid hormone. These hormoneshave been shown to promote bile formation or secretionand chronic deficiencies lead to cholestasis. Other clinicalfindings associated with panhypopituitarism include opticnerve hypoplasia, septo-optic dysplasia, and, in male patients,microphallus. In contrast to most of the cholestaticdiseases, which lead to an elevation in serum GGT concentrations,the GGT level in hypopituitarism typically is normal.Hypoglycemia can complicate prolonged fasts in theseinfants.Drug HepatotoxicityDependent on the maturity of the neonate, there is variabilityin the activity of members of the drug-metabolizingcytochrome P450 family in the newborn period. Thus, thenewborn infant may be particularly susceptible to druginducedhepatotoxicity, which can take a predominantlycholestatic form. The most common drug-induced liverinjury is caused by PN, used in the newborn period for avariety of indications. The liver injury caused by PN ismultifactorial, but in particular the phytosterol present insoy-based lipid formulations is a known antagonist of thenuclear receptor FXR, which is a regulator of the BSEP,an essential protein involved in bile acid transport. (6)Initial experience using fish oil–based sources of intravenouslipids has been promising, but larger clinical trialsin neonates have not yet been performed. There are casereports of neonatal cholestasis associated with maternal useof prescribed medications (carbamazepine) and illicitdrugs (methamphetamine). Postnatal infant exposureto antimicrobial agents, particularly ceftriaxone, fluconazole,and micafungin, has been associated with the developmentof cholestasis.Management of the Infant <strong>Who</strong> <strong>Has</strong>Prolonged CholestasisFailure to thrive is found commonly in infants who havechronic cholestatic conditions. The cause of poor weightgain is multifactorial. Reduced bile flow to the intestine resultsin poor solubilization of dietary fats in mixed micelles,leading to fat malabsorption and steatorrhea. Mediumchaintriglycerides (MCT) do not require bile for intestinalabsorptionandthusarepreferredininfantswhohavecholestasis.Several commercially available formulas have highlevels of MCT as their fat source, and there are supplementscontaining exclusively MCT that can be used for delivery ofadditional calories.Infants who have chronic liver disease may have an increasedbaseline caloric need coupled with demands for additionalcalories for catch-up growth. Unfortunately, manyof these infants are anorexic, justifying the use of nasogastricfeeds for caloric delivery. Fat-soluble vitamin deficienciesare pervasive in infants who have chronic cholestasis andshould be managed aggressively with frequent monitoring296 Pediatrics in Review Vol.33 No.7 July 2012

gastrointestinal disordersconjugated hyperbilirubinemiaof serum vitamin levels and use of oral fat-soluble vitaminsupplements.Ursodeoxycholic acid is a hydrophilic bile acid that isuseful in managing many cholestatic conditions. This bileacid has two purported benefits. First, it can stimulate bileflow and reduce cholestasis; second, it may displace moretoxicbile acids from the hepatocyte, thus potentially lesseningthe hepatocyte injury associated with cholestasis. Forsevere pruritis seen in cholestasis, which is caused by thedeposition of bile acids in the skin, oral antihistamines provideno benefit. Ursodeoxycholic acid can be helpful, andthe oral antibiotic rifampin often is added for refractorypruritis. The action of this agent in reducing itching is stillincompletely understood; but rifampin has been shown toprovide dramatic relief for affected infants.Approach to the Child and Adolescent <strong>Who</strong><strong>Has</strong> Conjugated HyperbilirubinemiaOutside of infancy, conjugated hyperbilirubinemia is amuch less common laboratory finding. Depending onthe cause of the hyperbilirubinemia, clinical manifestationswill vary and can include scleral icterus, jaundice, fatigue,pruritis, abdominal pain, and nausea. Chronicity of diseasecan be assessed by the history, keeping in mind that in thesetting of hepatobiliary disease, a nonspecific symptom,such as fatigue, may be present months before the developmentof more objective symptoms of cholestasis, such asjaundice and pruritis.The physical examination should include assessment ofliver size and texture. A firm, nodular liver suggests chronichepatobiliary disease and the development of cirrhosis.Physical stigmata of portal hypertension and cirrhosis includesplenomegaly, ascites, palmar erythema, caput medusae,and spider angioma. Normal metabolism of thesteroid intermediate androstenedione to testosterone typicallyoccurs in the liver. In end-stage liver disease, moreandrostenedione is eventually converted to estradiol, leadingto the development of gynecomastia in male patients.In female adolescents, secondary amenorrhea may resultfrom chronic liver disease.Initial laboratory assessment will include the measurementof serum aminotransferases (AST, ALT), GGT,and bilirubin (including conjugated, or direct bilirubin),as well as performing tests of liver synthetic function, includingprothrombin time and serum albumin level. Patientswho have poor liver synthetic function, manifestedas an elevated prothrombin time or low serum albuminlevel, should be referred urgently to a center with expertisein pediatric hepatology.If the physical examination and initial laboratory findingsdo not support chronic liver disease, but there is anelevated direct bilirubin fraction, consider a defect in thecanalicular transport of bilirubin. (7) Dubin-Johnson syndromeis a defect in the anion transporter gene ABCC2,inherited in an autosomal recessive fashion, which leadsto elevation both of unconjugated and conjugated bilirubinlevels. Rotor syndrome has a similar presentation tothat of Dubin-Johnson syndrome, but the underlying geneticdefect is unknown. These syndromes involve problemsin the storage/excretion of conjugated bilirubin andpresent with normal aminotransferase levels and the absenceof pruritis. The principal clinical objective is to distinguishthese benign conditions from the serious hepatobiliary diseasesdiscussed later in this article.The initial evaluation of a child or adolescent who hasconjugated hyperbilirubinemia should include abdominalultrasonography to assess for obstruction of the biliary tree.Typical symptoms reported with biliary obstruction includejaundice, abdominal pain (reliably reported as right upperquadrant or epigastric pain in <strong>old</strong>er children and adolescents),nausea, and vomiting. A more acute presentationis seen when biliary obstruction is accompanied by cholangitis,which is a bacterial infection of the biliary tree causedby stasis of bile upstream from the obstruction. Patients afflictedwith cholangitis usually will have fever and leukocytosisand can develop bacterial sepsis.Gallstone DiseaseThe most common cause of biliary obstruction in <strong>old</strong>erchildren and adolescents is gallstone disease (termed cholelithiasis).Little is known about the epidemiology ofgallstone disease in pediatrics. The pigmented stone isthe most commonly identified type of gallstone in children;however, overweight adolescent girls are at particularrisk of developing cholesterol stones. Identified risk factorsfor the development of gallstones in children include hemolyticdisease, existing hepatobiliary disease, cystic fibrosis,Crohn disease, chronic PN exposure, and obesity. Ifa gallstone becomes lodged within the common bile duct(termed choledocholithiasis), obstructive jaundice will resultand anticipated laboratory findings include elevationsin conjugated bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, and GGT.AST and ALT levels may or may not be elevated. Shouldthe gallstone impact distally at the junction of the commonbile duct and pancreatic duct, the patient may be symptomaticwith both obstructive jaundice and pancreatitis.Plain abdominal radiographs and computed tomographyare poor tests for the detection of gallstones becausemost stones are not calcified and therefore will not be visibleusing these techniques. Ultrasonography is highly sensitiveand specific for the detection of gallstones >1.5 mmin diameter within the lumen of the gallbladder; however,Pediatrics in Review Vol.33 No.7 July 2012 297

gastrointestinal disordersconjugated hyperbilirubinemiathe sensitivity drops off substantially for the detection ofgallstones within the common bile duct. The common bileduct will dilate in the setting of obstruction, and the diameterof the bile duct is readily measured by the ultrasonographer.The combination of a dilated common bile ductwith clinical and laboratory evidence of obstructive jaundiceis highly suspicious for a common bile duct stone.Many of these common bile duct stones will pass spontaneously,resulting in both clinical improvement in the patientand a decrease in the conjugated bilirubin level. Ifsymptoms persist, however, intervention is required urgentlybecause patients are at risk for development of cholangitisand bile duct perforation. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography(ERCP) is the methodology of choice forthe investigation and treatment of common bile duct stones.ERCP can visualize the presence of the stone (Fig 4), andthen deploy a balloon catheter to sweep the stone out of thecommon bile duct. Typically, a sphincterotomy of the ampullaof Vater is performed to enlarge the opening of thecommon duct and allow for passage of the stone. Regardlessof whether or not a patient passes a common duct stonespontaneously or requires therapeutic intervention, all patientswho have symptomatic gallstone disease will requiresurgical cholecystectomy when clinically stable.Choledochal CystA CDC is a congenital anomaly of the biliary tract characterizedby cystic dilatation of some portion of the biliarytree. CDCs can present in the newborn period asconjugated hyperbilirubinemia and a palpable abdominalmass. Outside of the neonatal period, the classic triad ofsymptoms includes fever, right upper quadrant abdominalpain, and jaundice, symptoms that may be easily confusedwith gallstone disease. Stones and sludge can formin the dilated biliary tree, leading to obstruction and thedevelopment of cholangitis as well as pancreatitis. Thereare several anatomic subtypes of choledochal cyst, with themost common being type I, which represents cystic dilatationof the common bile duct.The diagnosis of CDC is made most often with abdominalultrasonography, which demonstrates a cystic massnear the porta hepatis that is in continuity with the biliarytree. For better anatomic definition and classification ofthe CDC, as well as for surgical planning, a more robustradiographic test often is desired. Previously, ERCP wasthe preferred method for visualization of the CDC; however,because of the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis as wellas exposure to ionizing radiation, magnetic resonancecholangiopancreatography (MRCP) has replaced ERCPas the g<strong>old</strong> standard for characterization of CDCs.CDC is considered to be a premalignant state with aFigure 4. Contrast imaging of common bile duct via endoscopicretrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in a12-<strong>year</strong>-<strong>old</strong> girl who has right upper quadrant abdominalpain and conjugated hyperbilirubinemia. Arrows show fillingdefects in the lumen of a dilated common bile duct, representingmultiple gallstones in the common bile duct.significant lifetime risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma.Thus, for management of both acute biliary symptoms andfor cancer prevention, the treatment for a CDC is surgicalexcision and Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy.Other Causes of Obstructive JaundiceIn the setting of the acute onset of jaundice and fever,hydrops of the gallbladder should be suspected if abdominalultrasonography demonstrates a distended gallbladderwithout stones and with normal extrahepatic bileducts. Hydrops of the gallbladder in children is associatedwith Kawasaki disease as well as with acute streptococcaland staphylococcal infections.Tumors of the liver and biliary tract may present initiallywith jaundice, but jaundice rarely is an isolated finding andmore often is accompanied by abdominal pain and an abdominalmass. The possibility of tumor reinforces the importanceof the initial abdominal ultrasonography, whichwill suggest a mass, leading to subsequent computed tomographyor magnetic resonance imaging to evaluate thelesion further. Hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome,previously referred to as hepatic veno-occlusive disease, isseen in both children and adults receiving treatment298 Pediatrics in Review Vol.33 No.7 July 2012

gastrointestinal disordersconjugated hyperbilirubinemiafor cancer, particularly hematologic malignancy. Throughmechanisms that are not fully understood, the developmentof microthrombi in hepatic sinusoids leads to hepaticdysfunction that often is severe. Patients present with jaundice,hepatomegaly, ascites, and laboratory evidence ofhepatic synthetic dysfunction in addition to conjugatedhyperbilirubinemia and elevation of aminotransferase levels.Diagnosis is suggested by abdominal ultrasonographywith Doppler measurement, which shows a decrease or reversalof portal venous blood flow.Infectious HepatitisThe acute onset of jaundice, typically associated with rightupper quadrant pain, hepatomegaly, nausea, and malaise,with variable fever, is suggestive of an infectious hepatitis.Elevation of AST and ALT levels, usually at least 2 to 3times the upper limit of normal, is always seen in an infectioushepatitis, although the degree of hyperbilirubinemiacan be variable. A broad range of viral agents can lead toinfectious hepatitis. The incidence of hepatitis A infectionin the United States has plummeted drastically since theuniversal implementation of vaccination. Both hepatitisB and hepatitis C can cause jaundice at the time of acuteinfection, and thus it is important to measure serologicmarkers for hepatitis A, B, and C viruses in any child oradolescent who have hepatitis. Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirusboth can cause hepatitis and cholestasis inthe context of a mononucleosislike illness. Adenovirus, influenzavirus, parvovirus, members of the enterovirus family,herpes simplex virus, and varicella virus also can lead tohepatic involvement, usually in the context of other clinicalsymptoms typical of the individual virus.Autoimmune Disease of the Liverand Biliary SystemAutoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is characterized by a chronicactive hepatitis and non–organ-specific autoantibodies. (8)Without treatment, this chronic hepatitis progresses to cirrhosisand end-stage liver disease over time. AIH can presentat any age in children and adults, although the incidence increaseswith age during childhood and adolescence. AIH ismore common in girls, and the spectrum of clinical presentationis wide. AIH can present insidiously as fatigue, malaise,and recurrent fevers or fulminantly as acute liverfailure. Depending on the chronicity of disease, physicalfindings of portal hypertension may be present at diagnosis.Typically, there is elevation of AST and ALT levels, althoughwith considerable variation in the degree of elevation.Conjugated hyperbilirubinemia, a low albuminlevel, and an elevated prothrombin time indicate extensivechronic disease. The serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) levelusually is elevated, and 90% of patients will test positive forat least one of the associated autoantibodies: antinuclearantibody (ANA), anti–smooth muscle antibody (ASMA),and anti-liver, kidney microsomal antibody (LKM).Two distinct subtypes of AIH have been described andcan be distinguished by serologic autoantibody tests. Thefirst, AIH type I, is the most common, includes 80% of allpatients who have AIH, and is characterized by positiveANA or ASMA or both. AIH type 2 is more prevalentin younger children and is characterized by anti-LKM positivity.Children who have AIH type 2 are more likely topresent with acute hepatic failure. AIH can be associatedwith the autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasisectodermaldystrophy syndrome, one of the polyglandularautoimmune syndromes characterized by mucocutaneouscandidiasis, hypothyroidism, and adrenal insufficiency.Liver biopsy remains the g<strong>old</strong> standard in the diagnosisof AIH. Histologic features include a dense inflammatoryinfiltrate in the liver, consisting of mononuclear andplasma cells, that begins in the portal areas and extends beyondthe limiting plate into the parenchyma of the liver.Piecemeal necrosis of hepatocytes also is observed frequently.The treatment of AIH involves the use of immunosuppressiveagents. Conventionally, remission (definedas the normalization of AST and ALT levels) is inducedby using corticosteroids with a taper over several months.Corticosteroid-sparing agents, in particular the immunomodulatorazathioprine, are given long term to maintainremission of AIH.Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a progressive,autoimmune-mediated disease targeting both the intraandextrahepatic bile ducts, resulting in significant scarringof the biliary tree. Patients present with laboratory evidenceof bile duct injury, having elevations of GGT andalkaline phosphatase levels. AST, ALT, and conjugated bilirubinconcentration may be elevated as well. Imaging ofbile ducts, either with MRCP or ERCP, shows evidence ofstricturing and dilation of affected portions of the biliarytree.PSC usually is associated with inflammatory bowel disease,particularly ulcerative colitis, and can progress slowlyto cirrhosis. Several features distinguish PSC in childrenfrom adult disease. (9) In a subgroup of children who havePSC, there is elevation of IgG levels, autoantibody titers,and histologic features on liver biopsy similar to AIH,known as “overlap syndrome.” These children may favorablyrespond to immunosuppressive therapy. However, formost children and adults with PSC, there is a disconcertinglack of immunomodulatory therapies that can reverse thecourse of PSC.Pediatrics in Review Vol.33 No.7 July 2012 299

gastrointestinal disordersconjugated hyperbilirubinemiaDrug- and Toxin-Induced CholestasisDrug hepatotoxicity can manifest in many forms, rangingfrom a systemic drug hypersensitivity syndrome to isolatedcholestasis. Although some forms of hepatotoxicity are predictable,most are idiosyncratic owing to genetic variabilityin drug metabolism, making it difficult to understand thepathogenesis of hepatotoxicity in a given patient. (10)Some drug-induced cholestasis can present as an isolatedelevation of conjugated bilirubin; however, often there isa mixed hepatitic-cholestatic reaction with elevation of aminotransferasesand conjugated bilirubin. Commonly usedmedications in pediatrics that potentially can present withcholestatic liver injury include amoxicillin/clavulanic acid,oral contraceptives, and erythromycin. In any patientwho has cholestasis of unknown origin, it is critical to obtaina comprehensive medication history that includes recreationaluse of drugs. Ecstasy, in particular, has been associatedwith hepatotoxicity and the development of jaundice. Usein adolescents of anabolic steroids for bodybuilding has beenreported to cause cholestasis. Questioning also should be directedat therapies that are not regulated by the Food andDrug Administration, such as nutritional supplements andhomeopathic treatments, because hepatotoxic metabolitesof these substances have been described.Wilson DiseaseWilson disease is caused by an autosomal recessive inheriteddefect in the ATP7B gene, which codes for a hepatocyteprotein responsible for trafficking of copper into bile.(<strong>11</strong>) If the liver cannot excrete copper, the metal accumulatesin the liver, brain, kidneys, and eyes. Copper toxicitythen produces the end-organ dysfunction seen in Wilsondisease. Wilson disease rarely presents before 5 <strong>year</strong>s ofage, but its age of presentation and clinical manifestationsvary. With age, the likelihood of liver involvement at presentationdecreases, whereas the likelihood of neuropsychiatricdisease increases.The spectrum of the hepatic presentation of Wilsondisease includes an acute syndrome with nausea, fatigue,and elevated aminotransferases, mimicking infectious hepatitis.Long-standing liver injury may present with jaundiceand conjugated hyperbilirubinemia. Other common hepaticpresentations of Wilson disease include chronic hepatitis,cirrhosis with portal hypertension, and fulminant hepaticfailure. A clue to Wilson disease in the laboratory evaluationis a low alkaline phosphatase level in the setting of elevationof serum aminotransferase and conjugated bilirubin levels.Wilson disease also can affect the kidneys, manifesting asproximal tubular dysfunction with urinary loss of uric acidand subsequent low serum uric acid levels. Wilson diseaseaffects the hematologic system, leading in some patients toa direct antibody test (Coombs)-negative hemolytic anemia.Because of the varied presentation of this disease,a high degree of suspicion for Wilson disease must be keptin every school-age child or adolescent presenting with anytype of hepatic injury.The practitioner must rely on interpretation of a numberof diagnostic studies in the evaluation for Wilson disease.The sensitivity and specificity of these tests can varydepending on the clinical presentation. Diagnostic testsinclude measurement of serum ceruloplasmin, which istypically low (40 mg issuggestive of the disorder. Liver tissue can be sent for quantitativecopper measurement, and genetic testing is available.Prompt diagnosis of Wilson disease is important because theinstitution of copper chelation therapy can halt progressionof the disease, which is uniformly fatal if untreated.Benign Recurrent Intrahepatic CholestasisAutosomal recessive mutations in canalicular transportproteins FIC1 and BSEP produce the phenotypes PFIC1and PFIC2, respectively, which typically present in infancyor childhood and may progress to liver failure early in life.Less severe mutations in these genes can produce the diseaseknown as benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis(BRIC). Importantly, BRIC does not lead to progressiveliver disease, cirrhosis, or hepatic dysfunction. BRIC is anepisodic disorder and presents in the first or second decadeafter birth with pruritis, often severe, and jaundice. Episodesmay be precipitated by viral illnesses and typicallyare heralded by the onset of pruritis, followed weeks laterby the development of jaundice. Nausea and steatorrheaalso may be present. Laboratory tests of liver function revealnormal or mildly elevated serum AST and ALT, withelevation of both conjugated bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase.The GGT concentration typically is normal ormildly elevated. The prothrombin time may be mildly prolongedbecause of vitamin K malabsorption and deficiencyin the setting of cholestasis. Episodes can last weeks tomonths, and patients are completely well with normal livertesting in the intermediary periods. Treatment is directedtoward relief of pruritis, typically with ursodeoxycholicacid and rifampin, and correction of any fat-soluble vitamindeficiencies.300 Pediatrics in Review Vol.33 No.7 July 2012

gastrointestinal disordersconjugated hyperbilirubinemiaWith the initial episode of pruritis and jaundice, anatomicand histologic tests may be required to distinguishBRIC from PSC and other causes of intrahepatic cholestasis.Detailed imaging of the biliary tree, with either ERCPor MRCP, will be normal. During an episode, the dominanthistologic finding in the liver is centrilobular cholestasis.Hepatic lobular or portal inflammation is anunusual finding in the liver. In contrast to other inflammatorydiseases of the liver, such as AIH and PSC, liverhistologyinBRICwillreturntonormalinasymptomaticperiods.Summary• A variety of anatomic, infectious, autoimmune, andmetabolic diseases can lead to conjugatedhyperbilirubinemia, both in the newborn period andlater in childhood.• The pediatric practitioner is most likely to encounterconjugated hyperbilirubinemia in the neonatalperiod.• It is crucial to maintain a high degree of suspicion forcholestasis in the persistently jaundiced newborn. Thegoal is recognition of conjugated hyperbilirubinemiabetween 2 and 4 weeks after birth, allowing for theprompt identification and management of infants whohave biliary atresia, which remains the most commoncause of neonatal cholestasis.References1. Davis AR, Rosenthal P, Escobar GJ, Newman TB. Interpretingconjugated bilirubin levels in newborns. J Pediatr. 20<strong>11</strong>;158(4):562–565. e12. Matte U, Mourya R, Miethke A, et al. <strong>An</strong>alysis of genemutations in children with cholestasis of undefined etiology.J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51(4):488–4933. Hartley JL, Davenport M, Kelly DA. Biliary atresia. Lancet.2009;374(9702):1704–17134. Lien TH, Chang MH, Wu JF, et al; Taiwan Infant Stool ColorCard Study Group. Effects of the infant stool color card screeningprogram on 5-<strong>year</strong> outcome of biliary atresia in Taiwan. Hepatology.20<strong>11</strong>;53(1):202–2085. Wagner M, Zollner G, Trauner M. New molecular insights intothe mechanisms of cholestasis. JHepatol. 2009;51(3):565–5806. Carter BA, Taylor OA, Prendergast DR, et al. Stigmasterol, a soylipid-derived phytosterol, is an antagonist of the bile acid nuclearreceptor FXR. Pediatr Res. 2007;62(3):301–3067. Strassburg CP. Hyperbilirubinemia syndromes (Gilbert-Meulengracht,Crigler-Najjar, Dubin-Johnson, and Rotor syndrome). Best PractRes Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24(5):555–5718. Mieli-Vergani G, Heller S, Jara P, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis.J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;49(2):158–1649. Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D. Unique features of primarysclerosing cholangitis in children. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26(3):265–26810. Navarro VJ, Senior JR. Drug-related hepatotoxicity. N EnglJ Med. 2006;354(7):731–739<strong>11</strong>. Roberts EA, Schilsky ML; Division of Gastroenterology andNutrition, Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.A practice guideline on Wilson disease. Hepatology. 2003;37(6):1475–1492Suggested ReadingSuchy FJ, Sokol RJ, Balistreri WF, eds. Liver Disease in Children.3rd ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2007PIR QuizThis quiz is available online at http://www.pedsinreview.aappublications.org. NOTE: Since January 2012, learners cantake Pediatrics in Review quizzes and claim credit online only. No paper answer form will be printed in the journal.New Minimum Performance Level RequirementsPer the 2010 revision of the American Medical Association (AMA) Physician’s Recognition Award (PRA) and creditsystem, a minimum performance level must be established on enduring material and journal-based CME activities thatare certified for AMA PRA Category 1 Credit TM . To successfully complete 2012 Pediatrics in Review articles for AMAPRA Category 1 Credit TM , learners must demonstrate a minimum performance level of 60% or higher on thisassessment, which measures achievement of the educational purpose and/or objectives of this activity.Starting with 2012 Pediatrics in Review, AMA PRA Category 1 Credit TM can be claimed only if 60% or more of thequestions are answered correctly. If you score less than 60% on the assessment, you will be given additionalopportunities to answer questions until an overall 60% or greater score is achieved.Pediatrics in Review Vol.33 No.7 July 2012 301

gastrointestinal disordersconjugated hyperbilirubinemia1. A 3-month-<strong>old</strong> boy is jaundiced and is found to have conjugated hyperbilirubinemia; however, his gammaglutamyltransferase level is in the low normal range. Which of the following conditions is most likely tobe present?A. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiencyB. Biliary atresiaC. Cystic fibrosisD. Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasisE. Rubella infection2. A 14-<strong>year</strong>-<strong>old</strong> girl presents with a history of intermittent right upper quadrant pain over the last 2 months. Herlaboratory evaluation reveals a direct bilirubin of 2.3 mg/dL. Of the following, what is the most appropriatenext study?A. Abdominal ultrasonographyB. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatographyC. Hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid scanD. Liver biopsyE. Targeted mutation analysis of the uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase 1-1 gene to assess forGilbert syndrome3. You are examining a jaundiced 1-month-<strong>old</strong> girl and hear a heart murmur consistent with peripheral pulmonicstenosis. A blood test reveals conjugated hyperbilirubinemia, causing you to suspect this condition:A. Alagille syndromeB. Biliary atresiaC. Cystic fibrosisD. HypothyroidismE. Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis4. A toddler who has chronic cholestasis has pruritus that is refractory to ursodeoxycholic acid. Which of thefollowing medications may be helpful in reducing symptoms?A. AmoxicillinB. DiphenhydramineC. OndansetronD. RifampinE. Sulfisoxazole5. A 5-week-<strong>old</strong> boy has been found to have biliary atresia. His parents are hesitant to authorize surgery andprefer “to see how he progresses. If he does not do well, he can always have surgery later.” Which of thefollowing statements regarding Kasai portoenterostomy is true:A. Age at the time of the Kasai procedure is not associated with surgical outcome.B. Approximately 50% of children with biliary atresia have spontaneous resolution of their disease and do notrequire a Kasai procedure.C. The Kasai procedure involves insertion of an prosthetic bile duct.D. The Kasai procedure is curative and most patients do not require follow-up of their liver disease.E. The Kasai procedure, when performed at

Articlecollagen vascular disordersJuvenile Idiopathic ArthritisMaria Espinosa, MD,*Beth S. Gottlieb, MD, MS*Author DisclosureDrs Espinosa andGottlieb havedisclosed no financialrelationships relevantto this article. Thiscommentary does notcontain a discussion ofan unapproved/investigative use ofa commercial product/device.Educational GapJuvenile idiopathic arthritis affects around 294,000 children in the United States. In 2001,a new classification of the disorder and its subtypes was created. Current therapies, includingthe use of biologic medications, have improved the prognosis of this condition significantly.Objectives After completing this article, readers should be able to:1. Understand the pathophysiology of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA).2. Recognize the clinical features of the different types of JIA.3. Be aware of the complications of JIA.4. Know the treatment of JIA.IntroductionJuvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is a broad term used to describe several different forms ofchronic arthritis in children. All forms are characterized by joint pain and inflammation.The <strong>old</strong>er term, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, has been replaced by JIA to distinguish childhoodarthritis from adult-onset rheumatoid arthritis and to emphasize the fact that arthritisin childhood is a distinct disease. JIA also includes more subtypes of arthritis than did juvenilerheumatoid arthritis.JIA is the most common rheumatologic disease in children and is one of the more frequentchronic diseases of childhood. The etiology is not completely understood but is known to bemultifactorial, with both genetic and environmental factors playing key roles. Without appropriateand early aggressive treatment, JIA may result in significant morbidity, such as leg-lengthdiscrepancy, joint contractures, permanent joint destruction, or blindness from chronic uveitis.DefinitionArthritis is defined as joint effusion alone or the presence of two or more of the followingsigns: limitation of range of motion, tenderness or pain on motion, and increased warmth inone or more joints. JIA is broadly defined as arthritis of one or more joints occurring for atleast 6 weeks in a child younger than 16 <strong>year</strong>s of age. JIA isa diagnosis of exclusion. A number of conditions, such asAbbreviationsinfections, malignancy, trauma, reactive arthritis, and connectivetissue diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosusANA: antinuclear antibody(SLE), must be excluded before a diagnosis of JIA can beARF: acute rheumatic fevermade (1) (Table 1).AS: ankylosing spondylitisJIA is subdivided into seven distinct subtypes in the classificationscheme established by the International League ofIBD: inflammatory bowel diseaseIL: interleukinAssociations for Rheumatology in 2001 (Table 2). The subtypesdiffer according to the number of joints involved, pat-IV: intravenousJIA: juvenile idiopathic arthritistern of specific serologic markers, and systemic manifestationsMAS: macrophage activation syndromepresent during the first 6 months of disease. These categoriesNSAID: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugwere established to reflect similarities and differences amongRF: rheumatoid factorthe different subtypes so as to facilitate communicationSLE: systemic lupus erythematosusamong physicians worldwide, to facilitate research, and toTNF: tumor necrosis factoraid in understanding prognosis and therapy. (2)*The Steven and Alexandra Cohen Children’s Medical Center of New York, North Shore Long Island Jewish Health System, NewHyde Park, NY.Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by Enrique Mendoza-Lopez on July 2, 2012Pediatrics in Review Vol.33 No.7 July 2012 303

collagen vascular disordersjuvenile idiopathic arthritisTable 1. Differential Diagnosis ofArthritisReactiveInflammatoryInfectionSystemicMalignancyBenign bone tumorsImmunodeficiencyTraumaPoststreptococcalRheumatic feverSerum sickness“Reiter syndrome”Juvenile idiopathic arthritisInflammatory bowel diseaseSarcoidosisSeptic jointPostinfectious: toxicsynovitisViral (eg, Epstein-Barr virus,parvovirus)Lyme diseaseOsteomyelitisSacroilitis, bacterialDiscitisSystemic lupuserythematosusHenoch-Schönlein purpuraSerum sicknessDermatomyositisMixed connective tissuediseaseProgressive systemic sclerosisPeriodic fever syndromesPsoriasisKawasaki diseaseBehçet diseaseLeukemiaNeuroblastomaMalignant bone tumors (eg,osteosarcoma, Ewingsarcoma, rhabdosarcoma)Osteoid osteomaOsteoblastomaCommon variableimmunodeficiencyAdapted from Weiss JE, Illowite NT. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis.Rheum Dis Clin N Am. 2007;33:441–470.EpidemiologyIt has been estimated that JIA affects w294,000 childrenbetween the ages of 0 and 17 <strong>year</strong>s in the United States.The incidence and prevalence of JIA vary worldwide.This difference likely reflects specific genetic (eg, HLAantigen alleles) and environmental factors in a given geographicarea. The incidence rate has been estimated as 4to 14 cases per 100,000 children per <strong>year</strong>, and the prevalencerates have been reported as 1.6 to 86.0 cases per100,000 children. JIA tends to occur more frequently inchildren of European ancestry, with the lowest incidencerates reported among Japanese and Filipino children.In white populations with European ancestries, oligoarticularJIA is the most common subtype. In children ofAfrican American descent, however, JIA tends to occurat an <strong>old</strong>er age and is associated with a higher rate ofrheumatoid factor (RF)-positive polyarticular JIA anda lower risk of uveitis.Different subtypes of JIA vary with respect to age andgender distributions (Table 2). Oligoarticular JIA, forexample, occurs more frequently in girls, with a peak incidencein children between 2 and 4 <strong>year</strong>s of age. PolyarticularJIA also occurs more frequently in girls and hasa biphasic age of onset; the first peak is from 1 to 4 <strong>year</strong>sof age and the second peak occurs at 6 to 12 <strong>year</strong>s of age.(1)(3)PathogenesisThe cause of JIA is not well understood, but is believed tobe influenced by both genetic and environmental factors.Twin and family studies strongly support a genetic basisof JIA; concordance rates in monozygotic twins rangebetween 25% and 40%, and siblings of those affectedby JIA have a prevalence of JIA that is 15- to 30-f<strong>old</strong>higher than the general population.Strong evidence has been reported for the role of HLAclass I and II alleles in the pathogenesis of different JIAsubtypes. HLA-B27 has been associated with the developmentof inflammation of the axial skeleton with hip involvement,and often is positive in patients who haveenthesitis-related arthritis. HLA-A2 is associated withearly-onset JIA. The class II antigens (HLA-DRB1*08,<strong>11</strong>, and 13 and DPB1*02) are associated with oligoarticularJIA. HLA-DRB1*08 is also associated with RFnegativepoly JIA.Clinical features of systemic-onset JIA mostly resembleautoinflammatory syndromes, such as familial Mediterraneanfever, and there is a lack of an association betweensystemic-onset JIA and HLA genes. As a result, many concludethat systemic-onset JIA should be considered a separateentity, distinct from the other JIA subtypes. (4)Cell-mediated and humoral immunity play a role inthe pathogenesis of JIA. T cells release proinflammatorycytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor a (TNF-a),interleukin-6(IL-6),andIL-1,whicharefoundinhighlevelsin patients who have polyarticular JIA and systemiconsetJIA. Evidence for the role of T cells in JIA comesfrom studies that show oligoclonal expansion of T cells anda high percentage of activated T cells in the synovium ofpatients who have JIA.304 Pediatrics in Review Vol.33 No.7 July 2012Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by Enrique Mendoza-Lopez on July 2, 2012

collagen vascular disordersjuvenile idiopathic arthritisTable 2. International League of Associations for Rheumatology Classification of JuvenileIdiopathic ArthritisCategory DefinitionFrequency(% of all JIA) Age of Onset Sex RatioSusceptibilityAllelesSystemic onsetjuvenileidiopathicarthritis (JIA)Arthritis in one or more joints with or precededby fever of at least 2 weeks’ duration that isdocumented as daily (“quotidian”) for at least3 days and accompanied by one or more of thefollowing: (1) rash (evanescent), (2)lymphadenopathy, (3) hepatomegaly orsplenomegaly, (4) serositisOligo JIA Arthritis affecting one to four jointsduring the first 6 months of disease• Persistent Affects no more than four jointsthroughout the disease course• Extended Affects more than four joints after thefirst 6 months of diseasePolyarthritis Arthritis affects five or more joints in the(RF-negative) first 6 months of disease. Tests for RFare negativePolyarthritis(RF-positive)Arthritis affects five or more joints in thefirst 6 months of disease. Tests for RF arepositive on at least two occasions that are3 months apartPsoriatic arthritis Arthritis and psoriasis, or arthritis and at leasttwo of the following: (1) dactylitis, (2) nailpitting, (3) family history of psoriasis in afirst-degree relativeEnthesitis-relatedarthritisUndifferentiatedarthritisArthritis or enthesitis with at least two of thefollowing: (1) sacroiliac tenderness orlumbosacral pain, (2) presence of HLA-B27antigen, (3) onset of arthritis in a male >6<strong>year</strong>s <strong>old</strong>, (4) acute anterior uveitis,(5) family history in a first-degree relativeof HLA-B27–associated diseaseArthritis that fulfills criteria in no categoryor in two or more of the above categories4%–17% Childhood F[M HLA-DRB1*<strong>11</strong>27%–56% Early childhood;peak at 2–4 <strong>year</strong>s<strong>11</strong>%–28% Biphasic distribution;early peak at 2–4 <strong>year</strong>sand later peak at 6–12<strong>year</strong>s2%–7% Late childhood oradolescence2%–<strong>11</strong>% Biphasic distribution;early peak at 2–4 <strong>year</strong>sand later peak at 9–<strong>11</strong><strong>year</strong>s3%–<strong>11</strong>% Late childhood oradolescence<strong>11</strong>%–21%F>>>M HLA-DRB1*08HLA-DRB1*<strong>11</strong>HLA-DQA1*04HLA-DQA1*05HLA-DQB1*04HLA-A2 (earlyonset)F>>M HLA-DRB1*0801F>>M HLAB1*04HLA-DR4F>M HLA-B27IL23R † (newassociation)M>>F HLA-B27ERAP1 † (newassociation)Adapted from Ravelli A, Martini A. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Lancet. 2007;369:767–768.† Hinks A, Martin P, Flynn E, et al. Subtype specific genetic associations for JIA: ERAP1 with the enthesitis related arthritis subtype and IL23R with juvenile psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 20<strong>11</strong>;13:R12. HLA¼human lymphocyte antigen; JIA¼juvenile idiopathic arthritis; RF¼rheumatoid factor.Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by Enrique Mendoza-Lopez on July 2, 2012Pediatrics in Review Vol.33 No.7 July 2012 305

collagen vascular disordersjuvenile idiopathic arthritisRecently, inflamed joints in patients who have JIAhave been shown to have high levels of IL-17–producingT cells; IL-17 induces the production of other interleukinsand matrix metalloproteinases that are all involvedin joint damage. The role of humoral immunity in JIApathogenesis is supported by the increased level of autoantibodies,such as antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) andimmunoglobulins, by complement activation, and by thepresence of circulating immune complexes. (5)Other possible factors that have been implicated in thepathogenesis of JIA include immunologic dysregulation,psychological stress, trauma, hormonal abnormalities, andinfectious triggers.Clinical FeaturesJIA is divided into seven subtypes defined by clinical featuresduring the first 6 months of disease. The InternationalLeague of Associations for Rheumatology classification ofJIA includes the following subtypes: (1) Systemic-onsetarthritis, (2) oligoarticular arthritis, (3) polyarticular RFpositivearthritis, (4) polyarticular RF-negative arthritis,(5) psoriatic arthritis, (6) Enthesitis-related arthritis, and(7) undifferentiated arthritis, or “other.” Each subtypevaries with respect to clinical presentation, pathogenesis,treatment outcomes, and prognosis. All subtypes of JIA,however, share common symptoms, such as morningstiffness or “gelling phenomenon” (stiffness after a jointremains in one position for a prolonged period) thatimproves throughout the day, limp, swollen joints, limitationof activities because of pain, and periods characterizedby disease remission interspersed with disease flares.There is no diagnostic test for JIA; therefore, othercauses of arthritis must be excluded carefully before thediagnosis is made.The rash in systemic JIA is described typically as an evanescent,salmon-colored macular rash that accompaniesfebrile periods (Fig 1). The rash generally is nonpruriticand occurs most commonly on the trunk and proximalextremities, including the axilla and inguinal areas. (2)Other extra-articular manifestations that can be seen insystemic JIA include hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy,pulmonary disease, such as interstitial fibrosis,and serositis, such as pericarditis. The febrile period andother systemic features may precede the onset of arthritisby weeks to months. A definite diagnosis of JIA, however,cannot be made until arthritis is detected on physical examination.(6)Laboratory abnormalities typically observed in systemicJIA include anemia, leukocytosis, thrombocytosis,elevated liver enzymes, and acute-phase reactants, such aserythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, andferritin. ANA titer is usually negative and is not helpfulin making the diagnosis.Complications of systemic JIA include infection fromimmunosuppressive therapy, growth disturbances, osteoporosis,cardiac disease, amyloidosis (rare in NorthAmerica compared with other parts of the world), andmacrophage-activation syndrome (MAS) (Table 3). MASoccurs in about 5% to 8% of children who have systemicJIA and is characterized by persistent fever, pancytopenia,hepatosplenomegaly, liver dysfunction, coagulopathy,and neurologic symptoms. Bone marrow examinationSystemic-Onset JIASystemic-onset JIA is distinct compared with the othersubtypes in that it is characterized by the presence ofhigh-spiking fevers of at least 2 weeks’ duration in additionto arthritis. The disease affects 10% to 15% ofchildren who have JIA, and tends to affect boys andgirls equally, with a peak age of onset between 1and 5 <strong>year</strong>s. Early in the disease course, patients canpresent with fatigue and anemia. The fever in systemicJIA is characterized by temperatures >39°C that occurdaily or twice daily, with a rapid return to baseline or belowbaseline (quotidian pattern). Fever spikes usually occur inthe late afternoon or evening. Children often appear illduring febrile periods and look well when the feversubsides.Figure 1. Salmon-colored rash in systemic juvenile idiopathicarthritis. (Courtesy of Charles H. Spencer [http://www.rheumatlas.org].)306 Pediatrics in Review Vol.33 No.7 July 2012Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by Enrique Mendoza-Lopez on July 2, 2012

collagen vascular disordersjuvenile idiopathic arthritisTable 3. Macrophage ActivationSyndromePhysical findingsLaboratory findingsBone marrowTreatmentBruising, purpura, mucosalbleedingEnlarged lymph nodes,enlarged liver and spleenElevated: AST, ALT, PT, PTT,fibrin degradation products,ferritin, triglyceridesDecreased: white blood cell andplatelet counts, erythrocytesedimentation rate,fibrinogen, clotting factorsActive phagocytosis bymacrophages and histiocytesIntravenous glucocorticoid,cyclosporineALT¼alanine aminotransferase; AST¼aspartate aminotransferase; PT¼prothrombin time; PTT¼partial thromboplastin.Adapted from Cassidy JT, Petty RE, Laxer RM, Lindsley CB. Textbook ofPediatric Rheumatology. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Inc.; 2005.in patients who have MAS reveals phagocytosis of hematopoieticcells by macrophages. (2) Triggers of MAS includeviral infections and certain changes in medications.Laboratory abnormalities include pancytopenia, prolongationof the prothrombin time and partial thromboplastintime, and elevated levels of D-dimer, triglycerides,and ferritin. Contrary to what would be expected, theerythrocyte sedimentation rate typically falls in MAS becauseof the low fibrinogen levels resulting from a consumptioncoagulopathy and hepatic dysfunction. Because MAScarries a significant mortality rate of approximately 20% to30%, early recognition and treatment of MAS with corticosteroidsor cyclosporine is important to prevent multisystemorgan failure. (6)Diagnosis of systemic JIA involves the exclusion ofother conditions, such as infections, malignancy, collagenvascular diseases, and acute rheumatic fever (ARF). Infectionstend to have less-predictable fever patterns than systemicJIA. Children who have leukemia tend to haveleukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated lactic dehydrogenaselevels. In ARF, the fever tends to be persistent,the arthritis is migratory and asymmetric, cardiac involvementoften is associated with endocarditis, and the rash(referred to as erythema marginatum) is associated withan expanding margin. <strong>An</strong>tistreptolysin O titers can be elevatedin any inflammatory condition; however, the morespecific antibodies for streptococcal infection, such asantideoxyribonuclease b, antistreptokinsase, and antihyaluronidase,would be elevated only in ARF, indicatinga recent group A streptococcal infection.The prognosis of systemic JIA depends on the severityof the arthritis. Most systemic symptoms resolve overmonths to <strong>year</strong>s, and mortality, which is

collagen vascular disordersjuvenile idiopathic arthritisgrowth plate at sites of inflammation, which leads to overgrowth.This complication is most common with knee arthritisand it leads to a leg length discrepancy. Later in thedisease course, growth disturbances can result also fromgrowth plate damage or premature fusion of the epiphysealplates, leading to undergrowth of an affected extremity. (6)One of the most serious complications of JIA is iritis.Approximately 15% to 20% of children who have oligoarticularJIA are found to have iritis. The iritis tends tobe a chronic, anterior, nongranulomatous inflammationaffecting the iris and ciliary body and often is asymptomatic.This complication tends to occur in girls affectedwith oligoarticular JIA at a young age who have positiveANA titers. Appropriate ophthalmologic screening evaluationis imperative in all children who have JIA, especiallythose who have oligoarticular JIA and are ANA-positive(Table 4). If left untreated, complications include cornealclouding, cataracts, band keratopathy, synechiae, glaucoma,and visual loss (Fig 3). The outcome depends onearly diagnosis and treatment. (2)The differential diagnosis of a child with oligoarthritisincludes trauma, septic arthritis, Lyme disease, postinfectiousarthritis, and malignancy. In a child who presentswith features of an infectious illness, synovial fluid analysisand cultures are important to distinguish inflammatoryfrom infectious processes. In a septic joint, for example,there usually are more than 100,000 white blood cells/mm 3 , with 90% being polymorphonuclear neutrophils.Lyme arthritis can occur weeks to months after the initialinfection, and children typically will present with acuteonset of a large, swollen joint, typically the knee.In children who have oligoarticular JIA, laboratoryevaluation may be normal or indicate a mild increase ininflammatory markers. Tests for RF often are negative,and tests for ANA may be positive in low titers in 70%to 80% of children who have oligoarthritis, especially girlsand those who have iritis. (2)Among children who have JIA, those with oligoarthritishave the best prognosis. Children who develop a morecomplicated disease, characterized by joint space narrowing,bone erosions, and flexion contractures, are more likelyto be those who have a polyarticular course.Polyarticular JIAChildren affected by arthritis in five or more joints duringthe first 6 months of disease are diagnosed as having polyarticularJIA. Polyarticular JIA can be either RF-positive(seropositive) or RF-negative (seronegative). RF-positivedisease affects approximately 5% to 10% of patients whohave JIA and mainly affects girls in late childhood or earlyadolescence. Seropositive patients tend to develop an arthritissimilar to adult rheumatoid arthritis, having a moreaggressive disease course. There tends to be symmetric,small joint involvement of both the hands and feet andthe cervical spine and temporomandibular joints alsomay be affected (Fig 4). Rheumatoid nodules and a moresevere erosive disease characterized by joint deformities(ie, Boutonnière and Swan neck contractures) also mayoccur in patients who are RF-positive. (1) Patients withRF-negative arthritis tend to have involvement of fewerjoints and have a better overall functional outcome.Children who have polyarticular JIA may present withmorning stiffness, joint swelling, and limited range ofmotion of the affected joints. In addition, they also mayexperience fatigue, growth disturbances, elevated inflammatorymarkers, and anemia of chronic disease. Iritis maydevelop, although less frequently than in patients whohave oligoarticular disease.The differential diagnosis of patients presenting withpolyarthritis includes infection, malignancy, and othercollagen vascular diseases such as SLE. Polyarthritis inan adolescent girl could be an initial manifestation ofSLE; serologic tests for lupus must be sent.Table 4. American Academy of Pediatrics Guidelines for Screening EyeExaminationsJuvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA) Subtype Risk of Iritis Examination FrequencyOligoarticular or polyarticular, onset 7 <strong>year</strong>s of age regardless of antinuclear antibody Medium riskEvery 6 monthsstatusSystemic onset JIA Low risk Every 12 monthsAdapted from Ravelli A, Martini A. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Lancet. 2007; 369:767–768.308 Pediatrics in Review Vol.33 No.7 July 2012Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by Enrique Mendoza-Lopez on July 2, 2012