Artenol_Fall_flipbook

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

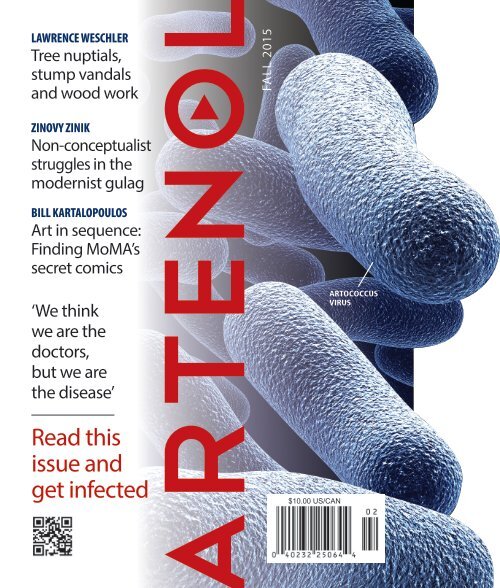

LAWRENCE WESCHLER<br />

Tree nuptials,<br />

stump vandals<br />

and wood work<br />

FALL 2015<br />

ZINOVY ZINIK<br />

Non-conceptualist<br />

struggles in the<br />

modernist gulag<br />

BILL KARTALOPOULOS<br />

Art in sequence:<br />

Finding MoMA’s<br />

secret comics<br />

‘We think<br />

we are the<br />

doctors,<br />

but we are<br />

the disease’<br />

Read this<br />

issue and<br />

get infected<br />

$10.00 US/CAN<br />

ARTOCOCCUS<br />

VIRUS

The taste<br />

of pure<br />

agave.<br />

FIDENCIO MEZCAL<br />

DOUBLE AND TRIPLE DISTILLED “SIN HUMO,” WITHOUT SMOKE, FOR THE PURE<br />

FLAVOR OF AGAVE. MADE FROM BIODYNAMICALLY FARMED ESPADIN AGAVE,<br />

HARVESTED ONLY DURING THE FULL MOON FOR A MORE DELICATE MEZCAL.<br />

fidenciomezcal.com<br />

The perfect way to enjoy Fidencio Mezcal is responsibly. Handcrafted and imported from Mexico.

g a l l e r y<br />

VOHN GALLERY serves as a platform for exhibitions,<br />

intellectual inquiry and cultural exploration. Though<br />

its name is new, the gallery is a continuation of a<br />

journey that was started in 2008.<br />

The group of international artists that VOHN works<br />

with share a strong conceptual underpinning to<br />

their practices. Their work is in the collections of<br />

MoMA, the Metropolitan Museum and The Guggenheim<br />

Museum. VOHN’s projects/exhibitions have<br />

received critical response in The New York Times,<br />

The New Yorker, Wall Street Journal and Interview<br />

Magazine, among others.<br />

VOHN GALLERY launched in September 2014 as a<br />

re-imagining of a project space that ran from 2012<br />

to 2013 in Chelsea, New York. The new gallery’s program<br />

will include upcoming exhibitions in TriBeCa,<br />

off site projects and <strong>Artenol</strong> journal.<br />

vohngallery.com<br />

Exhibition space: 45 Lispenard Street, Ground Floor, Unit 1W, New York, NY 10013<br />

Further information: info@vohngallery.com

Inside<br />

8 Arbor Ardor<br />

Tree art and its controversies by Lawrence Weschler<br />

44 Project: The Answer Machine<br />

Build your own Platometer by <strong>Artenol</strong>’s Tech Staff<br />

17 The Way Out<br />

Escape doom and pestilence with art by Gerald Celente<br />

47 Story: One Year in the Life<br />

A non-conceptual artist takes the cheese by Zinovy Zinik<br />

21 Scene: At the Camel Races<br />

Ships of the desert hitch a ride by David Green<br />

55 Poem: Angels and Ladders<br />

The beauty of language in translation by Gabrielle Noferi<br />

28 Plan: Art Temple<br />

A proposed house of art worship by Alex Melamid<br />

56 Reviews<br />

Essays by David Adler, Alex Melamid, Gary Indiana<br />

4<br />

“<strong>Artenol</strong>, in other<br />

words, seems very<br />

much like a cross<br />

between The New<br />

Criterion and<br />

Mad magazine.”<br />

29 Sun & Moon Comics<br />

Reading MoMA’s secret narratives by Bill Kartalopoulos<br />

34 Beauty by the Numbers<br />

A mathematician’s take on the sublime by Percy Wong<br />

61 The Visitors<br />

An gallery insider reviews the viewers by Anonymous<br />

63 Closer: At the Easel<br />

A little daub will do you by Nick Wadley<br />

– The New<br />

York Times<br />

38 What Is Beauty, and Why It’s Chopin<br />

One pianist’s definition of great art by Kelsy Yates<br />

Departments From the Founder 5 | Contact 6<br />

Contributors 7 | Where to Find <strong>Artenol</strong> 14<br />

118605190<br />

A tip of<br />

the top hat<br />

25<br />

An affectionate look at the rise<br />

and fall of millinery’s masterwork<br />

By Edward Tenner

INFECTIOUS<br />

MUSEUMUCUS<br />

From the Founder<br />

n ‘THERE IS ONE INDICATION THAT INCONTROVERTIBLY SEPARATES TRUE ART FROM<br />

FAKE: ITS INFECTIOUSNESS,’ WROTE LEO TOLSTOY IN HIS TREATISE WHAT IS ART?<br />

As Yale Daily News announced in September 2014:<br />

“Contagion Helps to Explain Art Value.”<br />

Tolstoy’s theory presumes that particles, invisible<br />

to the naked eye, are exuded from “true<br />

art“ objects. These particles attach<br />

themselves to our bodies<br />

and penetrate deep within. Today<br />

we might call them “art microorganisms.”<br />

Everyone who has ever visited<br />

Alex Melamid<br />

a museum has almost certainly<br />

been infected by these microorganisms<br />

because, as we all know, museums<br />

show only true art.<br />

This sounds bad. It is common for some art<br />

lovers to get headaches or become nauseated<br />

after being exposed to art, but this has always<br />

been ascribed to simple exhaustion. This presumption,<br />

however, may be wrong. What is<br />

even more worrisome is that, in certain cases,<br />

art microbial infections may be asymptomatic.<br />

That would mean most of us are likely already<br />

infected but remain unaware of our condition.<br />

Obviously, this art “infection” theory is just<br />

that – a theory, akin to climate change. But it’s<br />

one we shouldn’t discard out of hand. What<br />

better explanation is there for art’s contagious<br />

power? Clearly when contagion levels reach<br />

epidemic proportions, lovers of art become incapacitated<br />

and can no longer discern true art<br />

from false. If the infection theory is correct, we<br />

who appreciate art should be careful with how<br />

we consume it. Perhaps we should consider going<br />

on an art “diet.”<br />

Should we avoid infectious museums and galleries<br />

and stick to the cheap paintings found in<br />

big box outlets and dollar stores? How can we<br />

be certain that what they offer is all bad? What<br />

about the fact that our cities and towns have<br />

lately been flooded with public art? These sculptures,<br />

murals and wall hangings could jeopardize<br />

our health. How can we avoid becoming<br />

infected?<br />

<strong>Artenol</strong> proposes to create art-free zones to<br />

help protect the health of our citizenry.<br />

There was theory put forward by another<br />

Russian, a 19th-century philosopher named<br />

Alexander Herzen. He said, “We think we are<br />

the doctors, but we are the disease.” This, when<br />

applied to the art world, can mean two things.<br />

Either artists have been infected through continual<br />

exposure to true art, and thus there is no<br />

cure for them. Or it could mean that artists were<br />

sick to begin with, and they created art to infect<br />

the rest of population.<br />

Either way, <strong>Artenol</strong> serves as a purgative. Let<br />

the ideas and opinions presented in this magazine<br />

reinfect you with art antibodies. In its<br />

modest way, <strong>Artenol</strong> is helping to return artistic<br />

endeavor to its former good health.<br />

5

ATTORNEY ADVERTISING<br />

FALL 2015 | ISSUE 2<br />

The Law Office of<br />

Katya Yoffe, PLLC<br />

International<br />

Business<br />

& Art Law<br />

Rated by<br />

SuperLawyers<br />

for 2014, 2015<br />

PUBLISHER<br />

MANAGING EDITOR/<br />

ART DIRECTOR<br />

BRITISH EDITOR<br />

ACCOUNTS/<br />

CIRCULATION<br />

ADVERTISING<br />

Gary Krimershmoys<br />

David Dann<br />

Zinovy Zinik<br />

Denise Krimershmoys<br />

Gary Krimershmoys<br />

David Dann<br />

FOUNDER<br />

Alex Melamid<br />

6<br />

77 Water Street, Suite 852<br />

New York, New York 10005<br />

646-450-2896<br />

LEGAL COUNSEL<br />

Katya Yoffe, PLLC<br />

katya@kyoffelaw.com<br />

kyoffelaw.com<br />

PUBLISHED BY<br />

Art Healing Ministry<br />

Suite 8G<br />

350 West 42nd Street<br />

New York, NY 10036<br />

ON THE WEB<br />

artenol.org<br />

facebook.com/<strong>Artenol</strong><br />

CONTACT US<br />

info@artenol.org<br />

<strong>Artenol</strong> is published four times annually by the<br />

Art Healing Ministry, 350 West 42nd Street,<br />

Suite 8G, New York, NY 10036. © 2015 Art<br />

Healing Ministry. All rights reserved.<br />

<strong>Fall</strong> 2015, Issue 2.<br />

Single issues of <strong>Artenol</strong> are $10; a 1-year subscription<br />

is $36. For subscription information,<br />

please go to artenol.org.<br />

For customer service regarding subscriptions, please call<br />

845-292-1679. Reproduction of any part of this publication<br />

is prohibited without written permission from the publisher.<br />

All submissions become the property of <strong>Artenol</strong> unless<br />

otherwise specified by the publisher. Printed in China.<br />

FALL 2015

Contributors<br />

• David Adler | Mr. Enwezor Speaks ... (page 56)<br />

Adler produced the BBC documentary “The People’s<br />

Painting” about Komar and Melamid’s paint-bynumbers<br />

project. His most recent video is “Potlatch,”<br />

about a ceremony that takes place in a prison.<br />

• Gerald Celente | Finding the Way Out (page 17)<br />

A renowned trends forecaster, Celente is the publisher<br />

of Trends Journal. He founded the Trends Research<br />

Institute in Kingston, NY, in 1980.<br />

• David X. Green | At the Camel Races (page 21)<br />

Green is a London-based, travel and portrait photographer.<br />

His projects for magazines, charities and<br />

various clients have taken him around the globe,<br />

most recently Cuba, Thailand and Oman.<br />

• Gary Indiana | The Maestro, Seagrave (page 60)<br />

A long-time art critic at The Village Voice, author, film<br />

maker and playwright Indiana currently covers art,<br />

literature and film as well as politics and the media.<br />

• Gabriele Noferi | Poem: Angels & Ladders (page 55)<br />

Noferi is a translator of literary and scholarly works<br />

into Italian, including “Caravaggio: A Life.”<br />

• Edward Tenner | A High Art, a Higher Hat (page 22)<br />

The author of Our Own Devices and Why Things Bite<br />

Back, Tenner is a former college teacher and book editor<br />

who is now speaks and writes on technology and<br />

society for newspapers, magazines and websites.<br />

• Lawrence Weschler | Arbor Ardor (page 8)<br />

A staff writer for 20 years at The New Yorker and director<br />

emeritus of the New York Institute for the Humanities<br />

at NYU, Weschler recently launched “Pillow of<br />

Air,” a monthly column in The Believer.<br />

• Nick Wadley | Untitled (page 63)<br />

Wadley is a cartoonist and illustrator who has numerous<br />

graphic books, including “Nick Wadley’s Guide<br />

to British Artists” and “Drunk with Pleasure.”<br />

• Percy Wong | Beauty by the Numbers (page 34)<br />

Wong has a Ph.D. in applied mathematics and is<br />

fluent in English, Chinese and Yue (Cantonese). He<br />

is currently employed as an expert in quantitative<br />

analysis for a hedge fund.<br />

• Kelsy Yates | What Is Beauty ... (page 38)<br />

Yates has worked in advertising, wine making and<br />

interior design, and has written for The Writer’s Chronicle.<br />

She is currently at work on a short story collection<br />

and a novel.<br />

• Zinovy Zinik | Story: One Year in the Life ... (page 47)<br />

Zinik, a Moscow native, is the author of eight<br />

books of fiction and short stories. He is the London<br />

editor for <strong>Artenol</strong> and is heard regularly on the<br />

BBC’s The Forum.<br />

Get into the spirit<br />

of New York.<br />

Handcrafted,<br />

award-winning spirits<br />

Available at retailers throughout the tri-state area<br />

catskilldistilling.com<br />

7

Opener<br />

Arbor ardor

By Lawrence Weschler<br />

Tales of controversy<br />

amid sylvan splendor<br />

don’t know, maybe it’s something<br />

in the air, but when it comes<br />

to my interactions with the art<br />

world these past several years,<br />

I’ve been being dogged by trees<br />

(which, granted, is far better than<br />

its Django alternative, but still). Some of<br />

you may remember Houston’s great Art<br />

Guys’ tree wedding kerfuffle of a few seasons<br />

back − in November 2011, to be specific. Oy, do<br />

I remember it, because, dear reader, listen, I was<br />

the rebbe.<br />

Earlier that year, I’d been interviewing the<br />

Guys about something else altogether when<br />

they told me about how a couple years before<br />

that, at a time when Texas politicians were lashing<br />

themselves into a righteous lather over<br />

the prospect of gay marriage (how, in<br />

the inimitable stylings of Gov. Rick<br />

Perry, if you sanctioned gays marrying<br />

each other, the next thing<br />

you knew you’d have people demanding<br />

to marry their dogs), the two<br />

of them had decided to marry a tree. They<br />

insisted, tongues lodged distinctly somewhere<br />

cheekward (though it was not<br />

entirely clear how deep), that their gesture<br />

had nothing to do with Perry or<br />

gay marriage or anything like that –<br />

that, if anything, it nodded in an ecological<br />

direction.<br />

Anyway, they explained how back in 2009,<br />

since the sapling of their desires was still under<br />

age, they’d only gotten engaged (what kind of<br />

deviates did I take them for?), but that now that<br />

the tree in question had come of age, having<br />

reached sufficient height (i.e., theirs), and now<br />

that they had secured the Menil Collection’s<br />

commitment to lodge the bride as part of its collections<br />

in its own lush groves, they were now<br />

intending to hold a full-on wedding ceremony<br />

that coming November, and would I be willing<br />

to help officiate? I informed them that I only<br />

entertained such official functions in my some-<br />

9

time-somewhat role as rabbi, and to their credit,<br />

they did not blink.<br />

10<br />

Paper plane protest<br />

Little did I know, and probably little did any of<br />

us know, but by the time November had rolled<br />

around, the impending ceremony had taken<br />

on the trappings of a full-blown PC meltdown<br />

scandal, with several members of the local gay<br />

constabulary having taken it into their heads<br />

that the Art Guys were making fun of them.<br />

The Houston Chronicle’s art critic at the time<br />

hyperventilated about the way the Menil had<br />

allowed its hallowed name to become involved<br />

in an assault on what was, after all, “the human<br />

rights issue of our time.” At a sort of rally the<br />

night before the Menil ceremony, gay rights advocates<br />

and their supporters gathered at a local<br />

gay strip club, where the critic in question (just<br />

to register the sheer extent of the outraged community’s<br />

umbrage)<br />

By the time November<br />

had rolled around, the<br />

impending ceremony<br />

had taken on the trappings<br />

of a full-blown<br />

PC meltdown ...<br />

subjected himself,<br />

in the time-honored<br />

spirit of civil<br />

disobedience, to<br />

the ultimate sacrifice,<br />

as he put it, to<br />

“marry a woman.”<br />

The celebrants were<br />

thereupon invited to<br />

fold that marriage’s announcements into (very<br />

sharp) paper airplanes and to reconvene the<br />

next morning at the Art Guys’ event.<br />

This is the scene into which I, as rebbe, now<br />

found myself lumbering that gray and drizzly<br />

morn, as several hundred officiants gathered<br />

on the Menil’s grounds, several dozen of those<br />

armed with (very sharp-looking) paper planes.<br />

In any event, things went off quite peaceably.<br />

In my role as rebbe (nobody even noticed how in<br />

the spirit of the festivities I had taken to wearing<br />

a Palestinian kafia in lieu of the traditional Hebrew<br />

tallit), I noted how powerful a thing it was<br />

to be re-consecrating this particular tree in the<br />

wake of the previous season’s record-shattering<br />

heat wave which had decimated a truly dismay-<br />

UP A TREE The Art Guys, Michael Galbreth, left, and<br />

Jack Massing, and their betrothed pose for a formal<br />

portrait in 2011. Everett Taasevigen photo<br />

FALL 2015

LAWRENCE WESCHLER, right, speaks during the planting of a live oak on the grounds of The Menil Collection in<br />

March 2011. The tree was formally accepted into the permanent collection on June 2. The Menil Collection photo<br />

ing portion of the city’s other mature trees. I went<br />

on to invoke the wisdom of my fellow Rebbes<br />

Donald Barthelme (from the dryad-man love story<br />

in his short-tale sequence “Departures”) and<br />

Rabbinahs Denise Levertov (her sublime poem<br />

“A Tree Telling of Orpheus”) and Kay Ryan (her<br />

crisp, short heartbreaker of a lyric, “Tree Heart/<br />

True Heart”), after which the wise-and-wizened<br />

veteran Houston art honcho, James Surls, got up<br />

and asserted quite simply that he’d known the<br />

Art Guys in question for decades and they were<br />

obviously not homophobes. He added that the<br />

art world was way too small and itself way too<br />

threatened for this sort of thing and couldn’t we<br />

all just get along, at which point it seemed that<br />

those very sharp paper planes got stuffed back<br />

into pockets, the wedding ceremony proceeded<br />

to its conclusion, and blithe sanity seemed to<br />

have returned to the garden.<br />

Until a couple of days later, that is, when<br />

someone (no one ever found out exactly who)<br />

went and assassinated the tree.<br />

Or anyway, tried to. (The local media at any<br />

rate immediately took to referring to the Art<br />

Guys as “the widowers.”) And yet, somehow,<br />

the stunted plant survived. The Menil Collection,<br />

for its part, however, apparently freaked<br />

out by this latest turn of events, deaccessioned<br />

and now evicted the blasted tree-now-shrub,<br />

which had to be transplanted to a new home<br />

on a lot behind the Guys’ studio compound −<br />

though look at it now, three years on.<br />

So: maybe that was one of those sorta happy<br />

“life-(and the life of art)-goes-on” sagas after all.<br />

n A woods wounded<br />

Not so, alas, the next one. For exactly one year<br />

later, in November 2012, a disconcertingly similar<br />

series of incidents played out in England.<br />

Earlier that year, David Hockney had been the<br />

subject of a record-breaking exhibition at London’s<br />

Royal Academy of Arts<br />

surveying his prior decade of<br />

work. He had been documenting<br />

the passing of the seasons<br />

in the immediate wheat field<br />

and forest copse surrounding<br />

Hockney<br />

his new home in the small resort<br />

town of Bridlington on the Yorkshire<br />

coast, facing out toward Holland. These<br />

were the very fields and forests across which<br />

he had traipsed as a youngster and then as a<br />

teenaged summer worker on outings from his<br />

See a brief video<br />

about the wedding<br />

at artenol.org.<br />

11

HOCKNEY’S<br />

‘TOTEM’<br />

12<br />

TOTEMIC David Hockney’s painting of the Woldgate Woods, “Winter Timber,” showing the stump that was later<br />

cut down and painted with obscenities by vandals, below. The Associated Press photo<br />

hometown, further inland, of Bradford. Among<br />

the deliriously colorful oils, watercolors and<br />

iPad drawings were all manner of sketchbooks,<br />

and pencil and charcoal drawings − the same<br />

scenes returned to again and again, at different<br />

times of day across different seasons in different<br />

media. One series of these last in particular<br />

stood out for many people: a sequence of charcoal<br />

drawings documenting the thinning out<br />

of a particularly beloved stretch of woodland,<br />

the sort of clearing activity taken up every few<br />

years by the local foresters to ensure the continued<br />

health of the forest. One couldn’t help but<br />

glean a deep sense of mortality across the images<br />

that poured forth across Hockney’s witness,<br />

however − especially when one kept in mind the<br />

terrible swath among his own cohort that AIDS<br />

Hockney had<br />

himself asked the<br />

foresters to spare<br />

the stump, which<br />

he now took to<br />

referring to as<br />

the ‘Totem.’<br />

has scythed over the preceding decades.<br />

And even more moving, in<br />

this context, was the stalwart survival<br />

of one particular tall stump,<br />

which Hockney had himself asked<br />

the foresters to spare, and which<br />

he now took to referring to as the<br />

“Totem” and began portraying<br />

again and again, across all manner<br />

of other media, in the months that<br />

followed, a sort of stand-in, one<br />

couldn’t help but<br />

feel, for his own<br />

weathered self.<br />

In the months after<br />

the Royal Academy<br />

show, increasing<br />

numbers of tourists<br />

began trekking out<br />

to the two- or threesquare<br />

miles outside<br />

Bridlington that<br />

some people thought<br />

of as a sort of “Hockney National Park,” so immediately<br />

recognizable were that swerve of<br />

road, this specific hedgerow, that fold of wold,<br />

this forest path, and of course, that Totem. One<br />

day toward the end of November, Hockney was<br />

felled by a minor stroke and ended up spending<br />

the first night of his 75-year life in a hospital for<br />

observation. During that night, as it happens,<br />

vandals attacked the Totem, slathering it with<br />

pink graffiti, the words “cunt,” caricatures of a<br />

cock-and-balls, some of the imagery arguably<br />

homophobic in nature. When David returned<br />

home from the hospital (his linguistic abilities<br />

temporarily somewhat slurred, though his artistic<br />

ones were completely unscathed), his studio<br />

assistants were afraid to tell him of the vandal-<br />

FALL 2015

ism. But when he finally heard about it, he was<br />

surprisingly unfazed, noting that the coming<br />

winter’s storms would no doubt wash away the<br />

damage. A few weeks later, he traveled down<br />

to London for a minor follow-up operation, and<br />

that night the vandals returned − it is assumed<br />

there were at least two, given the mayhem they<br />

wrought − and completely chopped down the<br />

already-defaced stump.<br />

This time, returning to Bridlington and getting<br />

told of the attack, Hockney was completely<br />

devastated. He couldn’t get over the sheer<br />

gratuitous meanness of the act. “The meanness<br />

of it all,” he kept muttering. He retreated to his<br />

bedroom for two days of grimly defeated desolation,<br />

after which he roused himself and asked<br />

his crew to drive him out to the scene, where<br />

over the next several days, he recorded a suite of<br />

five gorgeously devastated charcoal drawings<br />

as a kind of commemorative tribute. Getting<br />

wind of the attack, the editors of The Guardian,<br />

one of Britain’s premier newspapers, contacted<br />

Hockney for comment. He told them of the<br />

drawings and agreed to let them run a selection,<br />

which they proceeded to do, on page 1, above<br />

the fold.<br />

News that stays new …<br />

n Into the forest<br />

I suppose trees have been back on my mind<br />

these recent days though because of a terrific little<br />

way-out-of-the-way show I happened upon<br />

this past spring, indeed one of the most memorable<br />

I saw all year (this being the time of year<br />

when we’re supposed to start toting up such<br />

nominations, after all).<br />

It was a student show, or rather it was the<br />

product of a graduate exhibition-practices curatorship<br />

seminar at the University of Illinois,<br />

Chicago, and was lodged in the university’s<br />

Gallery 400. I suppose I shouldn’t have been<br />

surprised at the enterprise’s quality, given the<br />

fact that even though the curatorial process had<br />

been exceptionally collaborative (as the catalog<br />

detailed), it had been led on an adjunct basis by<br />

Rhoda Rosen, one of the most dynamic and creative<br />

curators around.<br />

The UIC exhibition was entitled “Encounters<br />

at the Edge of the Forest,” and set out to survey<br />

the work of a range of contemporary artists<br />

who’ve recently been taking up trees as their<br />

subjects. But not trees as conventionally portrayed<br />

− that is, as pastoral emblems of nature<br />

unsullied by man − rather trees as they have in<br />

fact become: contested foci for nationalist assertion<br />

and state formation. As Rosen explained in<br />

her catalog essay:<br />

Modern scientific forest management,<br />

first established during the 18th century,<br />

functioned to connect all aspects of<br />

colonial power. Although its origins lie<br />

in Germany, it is no coincidence that<br />

Dietrich Brandis, whose name is synonymous<br />

with the birth of forestry, worked<br />

for a decade for the British colonial<br />

administration in India where, as Dan<br />

Handel shows, the widespread implications<br />

of forest management for the<br />

colonial agenda were first played out. As<br />

Lord Dalhousie’s superintendent of teak<br />

forests in the Pegu region of east Burma<br />

and, later, as his first inspector-general<br />

of forests, Brandis was directly implicated<br />

in Dalhousie’s project to modernize<br />

India in order to bring it more efficiently<br />

under British control. Further, he was<br />

implicated in Dalhousie’s expansion of<br />

the area of British rule through the largest-scale<br />

colonial land grab to date and<br />

to his endeavor to centralize communications<br />

in order to facilitate the military<br />

and economic exploitation of India’s<br />

natural resources.<br />

Rosen goes on to note that the British brought<br />

similar politico-forestry zeal to their administration<br />

of Palestine, zeal which continued into<br />

the Israeli period (think about the millions of<br />

incongruously Northern European pine saplings<br />

which were brought in, often to cover over<br />

evidence of once-vibrant-though-now-evicted<br />

Arab villages, and the generations-old indigenous<br />

olive groves which ironically were often<br />

being eradicated in the process).<br />

The show’s name derived from the title of a<br />

novella by the Israeli writer A.B. Yehoshua, Facing<br />

the Forest, in which a failed Hebrew scholar,<br />

unable to find meaning in his studies, assumes<br />

the position of a watchman in a remote forest<br />

Learn more about<br />

the exhibit at<br />

gallery400.uic.<br />

edu/exhibitions.<br />

13

14<br />

where he is supposed to be on the lookout for<br />

arsonists. The only other person he encounters<br />

is a mute Arab farmer whose tongue was cut<br />

out by Israeli forces in the 1948 war and who,<br />

by the end of the story, starts a fire. The student<br />

decides not to intervene and instead watches as<br />

the forest burns to the ground and reveals the<br />

ruins of the Arab village it had concealed.<br />

The genius of the show, however, was the way<br />

Rosen and her students were able to uncover similar<br />

sorts of tree deployments by artists working<br />

all over the world. Thus, for example, Ken Gonzales-Day’s<br />

gorgeously composed, Ansel Adams-like<br />

color photographs of magnificent solitary<br />

tree stands from all over the United States.<br />

These turn out to have been the<br />

actual trees from famous earlier<br />

lynching incidents and their<br />

resultant souvenir photographs<br />

− an especially effective way of<br />

solving the problem of alluding<br />

to those photographs without<br />

engaging in the ethically suspect<br />

activity of displaying the actual<br />

dead body.<br />

Elsewhere in the show, Rosen<br />

and her students displayed the video of a truly<br />

haunting 16mm film by the Israeli artist Ori Gershi.<br />

Taken in the Moskalovka forest in the Kosov<br />

region of Ukraine, one of the last great primeval<br />

forests in Europe, the film describes how Jews<br />

had hidden out there from the outset of the Holocaust<br />

until 1942. That year, 2,000 of them were<br />

discovered in the forest and murdered. In the<br />

film, the engrossingly serene beauty of the present-day<br />

forest is repeatedly sundered by the<br />

sound and sight of slicing, crashing trees.<br />

The South African photographer, David Goldblatt,<br />

was represented by his photograph called,<br />

“Remnant of a hedge planted in 1660 to keep the<br />

indigenous Khoi out of the first European settlement<br />

in South Africa,” an image of a hedge<br />

which has in the meantime been transplanted to<br />

and flourishes in one of South Africa’s most renowned<br />

botanical gardens in Capetown, at the<br />

The genius of the show<br />

was the way Rosen and<br />

her students were able<br />

to uncover similar sorts<br />

of tree deployments<br />

by artists working all<br />

around the world.<br />

LINES Andreas Rutkauskas’ “Stanstead Project”<br />

documents the “Cutline,” a clearcut space that<br />

demarcates the boundary between the United<br />

States and Canada. Andreas Rutkauskas photos<br />

FALL 2015

foot of Table Mountain (talk about the pastorally<br />

oblivious).<br />

Borders and barcodes<br />

The Canadian photographer, Andreas Rutkauskas,<br />

trains his lens on the bizarre “Cutline,”<br />

a clean slash of cleared-out forest that now, in<br />

the wake of 9/11, runs the entire length of the<br />

US-Canadian border, often to quite surreal effect;<br />

while the Brit, Philippa Lawrence, in her<br />

photographs, shows trees swathed with the<br />

very barcodes of the lumber for which they are<br />

industrially destined.<br />

Other instances got referenced in the show<br />

and its catalog as well, everywhere from Afghanistan<br />

to the demilitarized zone − or DMZ<br />

− separating North and South Korea. There,<br />

in 1976, a joint US and South Korean mission,<br />

code-named Paul Bunyan, broached the DMZ<br />

in an attempt to “assassinate” a poplar tree that<br />

was blocking the view from an observation post,<br />

a mission which resulted in the death of two US<br />

soldiers.<br />

But arguably the most affecting piece − and<br />

here we come full circle − was a videotape documenting<br />

the Israeli artist Ariane Littman’s intervention<br />

on the Palestinian side of the separation<br />

wall. Starting at dawn, the artist approached the<br />

stunted remains of a once-thriving olive tree in<br />

the middle of a traffic roundabout and proceeded<br />

to wrap it in surgical bandages, an achingly<br />

caring and evocative process which lasted until<br />

evening. The next morning, the catalog informs<br />

us, the bandages had all been stripped away.<br />

Rosen’s essay invokes “Unchopping a Tree,”<br />

W.S. Merwin’s remarkable prose poem from<br />

1970, the year of the first Earth Day. In it the<br />

poet begins the “unchopping” process by suggesting<br />

we “Start with the leaves, the small<br />

twigs, and the nests that have been shaken,<br />

ripped, or broken off by the fall;” he goes on<br />

with truly haunting rigor to lay out all the<br />

steps, one after the next, that would prove necessary<br />

if we were to succeed in righting the<br />

felled arbor. All manner of fixatives and heavy<br />

machinery are adduced across three pages of<br />

densely imagined prose, until<br />

finally the moment arrives when the<br />

last sustaining piece is removed and<br />

TREEAGE Ariane Littman wraps an ancient specimen at the Hizme<br />

checkpoint located at the northeastern entrance of Jerusalem in her<br />

performance called “The Olive Tree.” Rina Castelnuevo photo<br />

the tree stands again on its own. It is as<br />

though its weight for a moment stood<br />

on your heart. You listen for a thud<br />

of settlement, a warning creak deep<br />

in the intricate joinery. You cannot<br />

believe it will hold. How like something<br />

dreamed it is, standing there all<br />

by itself. How long will it stand there<br />

now? The first breeze that touches its<br />

dead leaves all seems to flow into your<br />

mouth. You are afraid the motion of the<br />

clouds will be enough to push to over.<br />

What more can you do? What more<br />

can you do?<br />

But there is nothing more you<br />

can do.<br />

Others are waiting.<br />

Everything is going to have to be<br />

put back.<br />

Put back indeed. Or at the very least toured:<br />

it would be nice if someone would find a way<br />

to travel the University of Illinois students’ remarkable<br />

little exhibit. It deserved a far wider<br />

and longer place in the sun than it got. n<br />

ARTHOPOX<br />

POLLENUS<br />

15

ART INVESTMENT • AUCTION GUARANTEES • ART LENDING<br />

16<br />

“We go where the market goes and are very adaptable”<br />

LONDON | NEW YORK | HONG KONG<br />

willstonemanagement.com<br />

A die-cut<br />

above<br />

the rest<br />

On newsstands,<br />

in bookstores now<br />

For a complete listing<br />

of <strong>Artenol</strong> vendors,<br />

or to purchase a copy,<br />

visit artenol.com

IMAGINE<br />

growing up in a culture of fear,<br />

where your every action and<br />

every written word are recorded, tracked and stored.<br />

IMAGINE<br />

growing up in a world that, while going about<br />

your daily routines, you encounter heavily<br />

armed police officers peering through armored visors as you walk by.<br />

IMAGINE<br />

growing up in a world of such moral<br />

decay that you have abandoned all faith in<br />

your leaders and the governmental rights and processes they<br />

manage – so much so, in fact, that you don’t even know their names.<br />

IMAGINE

Finding a way out<br />

By Gerald Celente<br />

IMAGINE growing up in a world<br />

where war is endless, where images of death and<br />

destruction are so pervasive, you don’t even pay<br />

attention to them any longer – if you ever did.<br />

Imagine growing up in a world where the populous<br />

is so muted, worn and disengaged that it<br />

allows – over and over – its leaders to drag the<br />

masses into brutal wars based on flagrant lies,<br />

repeating the same failed history over and over.<br />

If you were growing up in such a world, how<br />

would you cope? What would you do?<br />

Perhaps you would bow your<br />

head, plug your ears with headphones<br />

and peck away endlessly<br />

on your smart phone. You would<br />

listen to fabricated music, or even<br />

create it on your laptop and call<br />

yourself a musician. You would<br />

dress and present yourself like<br />

your peers, being just fine with<br />

the sameness that prevails around<br />

you.<br />

Your powerlessness would be<br />

reflected in the poor state of your<br />

physical, psychological and emotional<br />

health.<br />

You would rise up against abusive<br />

power when motivated, but it<br />

wouldn’t last long. You’re so beaten<br />

down and defeated by the chronic deception,<br />

lying and self-serving guile of your leaders that<br />

your own self-respect and trust in your leaders<br />

are now counted among the casualties. So<br />

immersed are you in a world where too many<br />

have allowed themselves to become packaged,<br />

processed and homogenized like so much of the<br />

food, fashion, music and media shoved down<br />

Fear consumes the<br />

post-9/11 world just<br />

as it did in the days<br />

following the attacks<br />

– only on a deeper,<br />

more subliminal level.<br />

their throats, your yearning for true, genuine<br />

expression is too difficult to hear.<br />

This is what fear has done to us.<br />

The epidemic of fear<br />

Fear consumes the post-9/11 world just as it<br />

did in the days following the attacks – only on a<br />

deeper, more subliminal level.<br />

As the United States and much of the world<br />

prepared to mark the 13th anniversary of 9/11,<br />

American President Barack Obama addressed<br />

the nation on September 10, 2014.<br />

Obama promised to “degrade,”<br />

“destroy” and “eradicate” the terrorist<br />

Islamic State “cancer” that<br />

posed a “growing threat to the<br />

United States.” It took him a mere<br />

14 minutes to declare a war that<br />

would be fought, in part, in Syria,<br />

which, like Afghanistan, Iraq<br />

and Libya, was innocent of committing<br />

crimes or acts of aggression<br />

against the United States but<br />

were nevertheless attacked and<br />

destroyed. It was the start of what<br />

some said would be a 30-year war.<br />

Thirty years!<br />

I wrote in the summer 2014<br />

edition of Trends Journal, while<br />

dissecting President George W. Bush’s 9/11 addresses<br />

to the nation, “Only a madman would<br />

speak such words. Only frightened people<br />

would believe them. And believe they did.<br />

Scared to death, Americans were dumbstruck<br />

with terror.”<br />

What has changed between Bush’s 9/11 speech<br />

in 2001 and Obama’s 13th anniversary declara-<br />

FALL 2015

tion? Absolutely nothing.<br />

Now, 13 years later, while the United States<br />

and much of the world still suffer from these<br />

9/11 wounds, they’re still victimized by the<br />

mad men and women banging war drums. The<br />

western world’s vulnerability to terror attacks is<br />

greater today than it was on September 10, 2001.<br />

In the post-9/11 era, fear drives everything.<br />

Barricades, video surveillance, police in armor,<br />

metal detectors, cyber hackings, X-ray machines<br />

at airports, and armed guards and terrorist<br />

drills in office buildings just skim the surface<br />

of describing a world in lock-down. The surveillance<br />

state has arrived. And the density and<br />

coldness that abound in our world – from our<br />

music to our architecture, to our craftsmanship,<br />

and to our standards for what passes as creativity<br />

– reflect the effects of living in a state of fear.<br />

The inner spirit<br />

We have to ask ourselves: How low have our<br />

moral standards sunk? When did it become<br />

routine, expected and business-as-usual that we<br />

are led down such destructive roads with so little<br />

accountability and no regard for the history<br />

that’s so obviously and indisputably repeating<br />

itself?<br />

Who’s to blame? How did it happen?<br />

Them, you and me. We all do our part to create<br />

the conditions that exist. And at the heart of<br />

it, at the very core of our collective despondency<br />

and dejection, lies a simple question: What is the<br />

way out?<br />

Art is the way out.<br />

Not the soulless, mass-produced facades of<br />

so-called “art” consuming popular culture, but<br />

genuine art borne out of equal parts vision,<br />

heart, skill and labor. Power-hungry leaders<br />

who govern by lies, stupidity and indifference<br />

– while never being held accountable – are defenseless<br />

against art. They are incapable of finding<br />

it in their hearts. They are powerless in its<br />

presence.<br />

What will it take to reverse negative trends<br />

and replace them with elements of joy, beauty,<br />

grace and prosperity? It begins and ends with<br />

the inner spirit, the sanctum where courage,<br />

purpose, self-awareness and the passion to create<br />

– and appreciate – beauty lives.<br />

Today, a sustained poor global economy, endless<br />

war, immorality among world leaders and<br />

political polarization have compelled us to seek<br />

refuge in technology at our fingertips. Human<br />

embrace, engagement and experience are too<br />

often overwhelmed in this techno world. But<br />

those qualities aren’t lost; they are just muted.<br />

The world will grow tired of the sameness. It<br />

is ready to awaken.<br />

A trend worth tracking<br />

Unique, powerful art movements born in<br />

response to the dreary sameness of the world<br />

that pervasive fear has created are beginning<br />

to emerge. Analysts are tracking how unique<br />

galleries, restaurants, music clubs and creative<br />

gathering spots are clustering in big<br />

and small cities, attracting patrons seeking<br />

reprieve from the homogenized<br />

world. There is growing evidence that<br />

movement is afoot to alchemize entrepreneurism<br />

and creative expression as<br />

a means to inspire a community – and<br />

make a living, too.<br />

Stanley Blum, an artist and poet who lives<br />

in New York, is a fine example of the enduring,<br />

timeless and transformational power of art in<br />

dark times. For the 95-year-old Blum, 9/11 unleashed<br />

“the angst and the creative energy that<br />

lay dormant for years.” Living through the horrors<br />

of that day awakened him to an insight that<br />

changed his life: “It takes courage to accept the<br />

chaos and mindlessness around us. We have to<br />

reach inside ourselves, depend only on the creativity<br />

inside of us, to combat those forces.”<br />

So, at age 80, Blum began expressing himself<br />

– in paintings, poems and by inspiring others of<br />

all age groups. Now, five books later, Blum feels<br />

the ground shaking. He sees it coming.<br />

“The First American Enlightenment movement<br />

is coming,” said Blum. “Periods of growth,<br />

freedom and morality will come to life when<br />

creativity is unleashed, and we have no choice<br />

now but to unleash it.”<br />

The great Swiss psychologist Carl Gustav<br />

Jung stressed that changing the world begins<br />

with finding, expressing and celebrating one’s<br />

own uniqueness. “Individualism means deliberately<br />

stressing and giving prominence to<br />

some supposed peculiarity rather than to collective<br />

considerations and obligation,” he wrote<br />

AESTHETE<br />

GAMETE

CURRENT TRENDS IN ART<br />

Overcoming fear and hate as more discover the beauty of the creative impulse.<br />

ARTS AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATIONS<br />

In the past decade, the number of nonprofit arts organizations has<br />

grown 49%. The breakdown of all arts groups in 2010:<br />

Museums,<br />

galleries<br />

6%<br />

Performing arts<br />

Source: US Census<br />

All others<br />

15%<br />

18%<br />

61%<br />

Arts associations,<br />

councils, collectives, etc.<br />

Total: 113,000<br />

ARTISTS<br />

The number of artists continues<br />

to grow, increasing by<br />

15% from 1996 to 2010.<br />

3M<br />

2M<br />

1M<br />

1.9<br />

million<br />

2.2<br />

million<br />

0<br />

1996 2010<br />

Source: National Arts Index<br />

SALES<br />

$150B<br />

UP<br />

31%<br />

SOLD<br />

Over the last decade, consumer<br />

spending on the arts, a discretionary<br />

expenditure, has climbed to about<br />

$150 billion, increasing from 1.45%<br />

in 2002 to 1.88% in 2010.<br />

Source: National Arts Index<br />

20<br />

See more of<br />

Gerald Celente’s<br />

trends at trendsresearch.com.<br />

INVOLVEMENT IN THE ARTS<br />

Arts involvement began to rebound after the 2008 downturn. In 2013, 32 percent of the adult population attended a performing arts event (up from<br />

28 percent in 2010); 22 percent visited an art museum (up from 12 percent). These are the first strong increases since 2003.<br />

40%<br />

35%<br />

30%<br />

25%<br />

20%<br />

15%<br />

10%<br />

5%<br />

0%<br />

Source: National Arts Index<br />

Attended an arts event<br />

Visited a museum or gallery<br />

Purchased an artwork<br />

2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012<br />

in The Function of the Unconscious. Jung referred<br />

to the purest, highest-quality forms of art as<br />

“supra-personal,” destined to be “constantly at<br />

work educating the spirit of the age.”<br />

That translates into change.<br />

Internationally respected painter Eugene Gregan<br />

described the coming change this way: “The<br />

antidote to fear is beauty. To have satisfaction in<br />

your life, you must have grace. Grace gives life<br />

to creativity. Grace grows out of the discipline<br />

of the self. Discipline gives one dignity. Without<br />

dignity, genuine depth is not possible …”<br />

The sameness I speak of is borne out of a world<br />

consumed with fear, where we hide from it in<br />

our technology. The discipline Gregan speaks of<br />

relates to our ability to express our own creative<br />

impulses, to live outside of the control of others<br />

by embracing true creative expression.<br />

“Without art, the crudeness of reality would<br />

make the world unbearable,” wrote George Bernard<br />

Shaw. One hundred years later, the news is<br />

filled with fear and hate. There is no talk of joy or<br />

beauty. The “crudeness of reality” has made the<br />

world unbearable. As its leaders join in a march<br />

to war, can “the people” give rise to a passion to<br />

live in peace? Where is the music to soothe the<br />

savage breast? Where is the art to bring beauty<br />

to the eyes and meaning to the soul?<br />

The world is ready for a renaissance. If 85 people<br />

can have more money and the power it brings<br />

than 3.5 billion people, or half the world’s population,<br />

then there’s a Medici among the masses.<br />

That’s all it will take. In the absence of the one,<br />

it will take the many who unite in the belief that<br />

art is the way of finding the true meaning of the<br />

human spirit.<br />

n<br />

FALL 2015

Scene<br />

IN KEEPING WITH<br />

my commitment<br />

to travel to a new<br />

country each New<br />

Year’s, this year –<br />

my 33rd such trip<br />

in a row – was to<br />

Oman, where I<br />

managed to locate<br />

one of the surprisingly<br />

elusive camel<br />

races. Although a<br />

widely popular national<br />

event, these<br />

races are rarely on<br />

the tourist itinerary.<br />

The race itself<br />

is a blend of the<br />

magnificent, as<br />

the lean, racing<br />

camels gallop full<br />

speed through<br />

clouds of sand glittering<br />

in the baking<br />

heat, and the<br />

surreal, as they are<br />

guided not by the<br />

recently outlawed<br />

child jockeys but<br />

by tiny “robots,”<br />

operated remotely<br />

by the owners<br />

blazing alongside<br />

the race course in<br />

SUVs parallel. The<br />

two camels in this<br />

image may have<br />

been purchased at<br />

auction that day. I<br />

wonder if Toyota<br />

ever envisioned<br />

this cargo? I did<br />

find it rather<br />

incongruous to<br />

see camels – these<br />

graceful ships of<br />

the desert –<br />

loaded onto the<br />

bed of a pick-up.<br />

David Green<br />

www.davidxgreen.com photo<br />

21

Head Gear<br />

A High<br />

The brilliant career<br />

of the top hat<br />

By Edward Tenner<br />

ROYAL<br />

MARINE<br />

22<br />

Bell Crown<br />

Topper<br />

wikimedia.org<br />

1The top hat took shape in the aftermath of the French<br />

Revolution, a variant of the practical “round hat” worn<br />

by country gentlemen for riding and hunting. One of the<br />

best representations is Jean-Louis David’s portrait of his<br />

brother-in-law, Pierre Sériziat, in the Louvre.<br />

It began its<br />

2 urban life as an<br />

emblem of everything<br />

progressive,<br />

as worn by the<br />

new democratic<br />

era’s leading feminist<br />

author, Mary<br />

Wollstonecraft,<br />

in the National<br />

Portrait Gallery.<br />

National Portrait Gallery, London<br />

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London<br />

Though an international style,<br />

3 the top hat became a favorite of the<br />

English, known throughout the nineteenth<br />

century for the finest craftsmanship. In this<br />

painting, based on an actual shipboard visit,<br />

Charles Eastlake records a Royal Marine<br />

probably assigned to guarding Napoleon<br />

on his voyage to St. Helena. The top hat<br />

was replacing the bicornes and tricornes of<br />

the old regime, announcing the rule of the<br />

British seaborne empire.<br />

FALL 2015

Art, a Higher Hat<br />

My quest for the top hat began over 25<br />

years ago, when Harvard Magazine<br />

displayed a photograph of a magnificent<br />

silk specimen, still worn by<br />

a member of Harvard’s Honorable and Reverend<br />

Board of Overseers, as a cover illustration for my<br />

essay on headgear, “Talking through Our Hats.” I<br />

had begun the piece by invoking this object, and<br />

shortly thereafter, a<br />

woman in Michigan,<br />

wife of a Harvard<br />

alumnus, offered to<br />

send me a<br />

silk hat from her attic. It arrived soon thereafter, in<br />

its original box, with the label of a shop in Albany,<br />

New York in 1846. I began to investigate its riddles.<br />

How was the silk manufactured? What made<br />

it so popular when it was often impractically high?<br />

Some day I hope to organize an exhibition that will<br />

at last do justice to this uncannily durable object.<br />

Meanwhile, here is a preview of its spectacular<br />

metamorphoses.<br />

4<br />

What would<br />

Isambard Kingdom<br />

Brunel, architect of<br />

the colossal steamship<br />

Great Eastern, and his<br />

colleagues wear at her<br />

launch in 1866 but the<br />

high-crowned model<br />

that contemporaries<br />

compared to chimney<br />

pots and factory<br />

smokestacks?<br />

23<br />

BRUNEL<br />

London’s first Metropolitan Police<br />

5 also wore top hats and middleclass<br />

frock coats. To early recruits,<br />

uniforms still carried the demeaning<br />

stigma of domestic servants’ liveries.<br />

Photos provided

24<br />

Perhaps because the<br />

6 silk hats that were replacing<br />

felt and fur models<br />

by 1840 revealed the ability<br />

to pay for special care and<br />

could show off proper bearing,<br />

they were as popular<br />

among upper-class and bohemian<br />

dandies as among<br />

bourgeois professionals.<br />

From the 1840s to the<br />

1890s, not much changed<br />

in the headgear and demeanor<br />

of Count d’Orsay<br />

(likely prototype of the New<br />

Yorker’s fictitious mascot<br />

Eustace Tilley) and of Count<br />

Robert de Montesquiou<br />

(said to be the model for<br />

Marcel Proust’s Charlus).<br />

D’ORSAY<br />

Abe Lincoln<br />

Top Hat<br />

DE MONTESQUIOU<br />

wikimedia.org<br />

Rowdy young urban<br />

7 tradesmen, immortalized<br />

by the actor Frank Chanfrau in<br />

Benjamin Baker’s hit comedy,<br />

“A Glance at New York,” in<br />

1848, parodied middle-class<br />

Photos provided<br />

costume. Here Mose the “Bowery B’hoy” wears his trademark “plug”<br />

hat with studied swagger. The B’hoys’ Philadelphia counterparts were<br />

called “The Killers.” One of them, in a poster of the same year, could<br />

have been the later Abraham Lincoln’s evil twin.<br />

BOOTH<br />

wikimedia.org<br />

FALL 2015

As the silk plush<br />

9 covering decayed,<br />

hats were sold down<br />

market until even the<br />

poorest – deserving<br />

and otherwise –<br />

could afford them, as<br />

illustrated by William<br />

Makepeace Thackeray’s<br />

Book of Snobs (1848)<br />

and an 1860 ambrotype<br />

of a veteran of<br />

the Peninsular Wars<br />

Library of Congress; wikimedia.org and his wife.<br />

Lincoln’s stovepipe hat is the most revered<br />

8 headgear in American history; he appears<br />

to have chosen it in part to look even taller, and<br />

bought a new one from one of New York’s leading<br />

hatters, Knox, for delivering the Gettysburg<br />

Address. John Wilkes Booth’s hat, worn in one of<br />

the carte de visite photographs that he distributed<br />

to his many admirers at the peak of his career, was<br />

the mark of an affluent and fashionable young<br />

man: low-crowned beaver, always costliest of hat<br />

furs. It was headgear with attitude. Lincoln once<br />

owned a similar model and wore it at his first<br />

inaugural address, but interestingly the only clear<br />

engraving on the web of Lincoln and outgoing<br />

President James Buchanan in their carriage shows<br />

Lincoln bareheaded.<br />

Victorian<br />

Top Hat<br />

25<br />

LINCOLN<br />

wikimedia.org

With the decline of the frock coat<br />

10 and the morning coat in the 1870s<br />

in favor of the “lounge suit” (our present<br />

men’s suit) and the bowler, the silk hat came<br />

to represent self-conscious formality and old<br />

school ways, especially in England. An 1887<br />

advertisement in the Century Illustrated Magazine<br />

is typical of the new image.<br />

Photo provided<br />

26<br />

Mid-Crown<br />

Top Hat<br />

A new negative stereotype of the top hat<br />

11 was also emerging, as an emblem of plutocracy,<br />

trusts and financial manipulation. In 1908, following<br />

the panic that was to lead to the creation of<br />

the Federal Reserve and a hundred years before the<br />

Great Recession, the founder and chief cartoonist of<br />

the satirical magazine Puck, Joseph Keppler, reflected<br />

Wall Street’s reputation following the crisis.<br />

Library of Congress<br />

wikimedia.org<br />

While mostly a ceremonial accessory rather<br />

than everyday attire for the most of the<br />

12<br />

wealthy by 1900 or so, especially in the U.S., the<br />

top hat became an indispensable signifier of capitalism<br />

for progressive and socialist satirists. Soviet<br />

poster artists loved to hate their top-hatted villains,<br />

as in this image of “The Final Hour” from the Bolshevik<br />

Revolution’s early years. Since John Bull and<br />

Uncle Sam were traditionally drawn with top hats,<br />

both Russian and Nazi propagandists reveled in the<br />

synergy of stereotypes.<br />

FALL 2015

The Associated Press<br />

Despite or because of its prominence in<br />

13 left-wing propaganda, and more gently in<br />

the 1930s game Monopoly (worn by the dapper<br />

Rich Uncle Pennybags), the top hat has never lost<br />

its magic. John F. Kennedy may have declared in his<br />

1961 inaugural address that “the torch has been<br />

passed to a new generation of Americans – born in<br />

this century ...,” but contrary to urban legend, he<br />

wore a traditionalist silk hat to the ceremony, reversing<br />

his predecessor Dwight Eisenhower’s choice<br />

of a homburg (the talk of an already ailing hat<br />

industry) in 1953 and 1957. Eisenhower and other<br />

dignitaries followed Kennedy’s lead at the events.<br />

Lyndon B. Johnson was the first president hatless at<br />

a public inauguration four years later.<br />

New York Public Library<br />

TOP TOPPER<br />

Hatter Max Fluegelman ran America’s<br />

largest top hat plant from his operations on<br />

6th Avenue in New York City. Commissioned<br />

by the American corporation, H.J. Heinz,<br />

Fluegelman created an enormous shiny silk<br />

top hat to be featured as a visitor attraction in<br />

the Heinz exhibit at the New York World’s Fair<br />

in 1939. Measuring several feet high with a<br />

7½-inch-wide brim and an 18-inch-diameter<br />

crown, the immense top hat covered half a<br />

human’s height if rested atop a person and<br />

was large enough around to sit on four or<br />

more men’s heads.<br />

From Hats and Headwear Around the World:<br />

A Cultural Encyclopedia, by Beverly Chico<br />

Deadman<br />

Top Hat<br />

27<br />

wikimedia.org<br />

By the time the song “Frosty the Snowman” appeared in<br />

14 1950, it was plausible to find an abandoned top hat that<br />

miraculously animated the title character. But vintage models are no<br />

longer discarded casually. It is now impossible to make a genuine<br />

new silk hat; the special plush cloth, always costly to produce, has<br />

not been manufactured for nearly 50 years. Since satin and other<br />

substitutes cannot duplicate the original silk luster, which the French<br />

call “eight reflections,” demand for wear on formal occasions far<br />

exceeds supply. Restored used examples in today’s larger head sizes<br />

can cost thousands of pounds. What Mary Wollstonecraft evidently<br />

considered a radical gesture is still de rigeur, by personal command<br />

of Queen Elizabeth II, in the Royal Enclosure at Ascot.<br />

n

Art<br />

detox<br />

Art meditation<br />

Art<br />

Health<br />

clinic<br />

Art<br />

Army<br />

28 Art Art and<br />

Army Politics<br />

Artist of<br />

the month<br />

Art<br />

diet<br />

plan<br />

Art Army<br />

Art<br />

Army<br />

Art<br />

Dating<br />

art of the day<br />

portico<br />

Celebrities<br />

on art<br />

Visual<br />

prayer<br />

circle<br />

Art<br />

Sentries<br />

Art bishop’s garden<br />

Art Temple<br />

Client: <strong>Artenol</strong><br />

New York, NY<br />

Plan View<br />

Architect: A. Melamid<br />

<strong>Fall</strong> 2015

Although it has no comics<br />

collection, no comics department<br />

and no comics curator,<br />

the Museum of Modern Art<br />

is absolutely full of comics. I<br />

must stress that I do not refer<br />

here to the museum’s few<br />

anomalous holdings from the<br />

history of “comics” proper.<br />

Lyonel Feininger’s 1906 Kin-<br />

Der-Kids newspaper comic<br />

strips, for example, sit in storage<br />

as part of a larger collection<br />

including the Bauhaus<br />

instructor’s paintings, prints<br />

and drawings. The museum<br />

is also strangely in possession<br />

of two original Batman comic<br />

strips from the 1960s, erroneously<br />

attributed to Batman<br />

co-creator Bob Kane and donated<br />

to the museum by Kane<br />

himself (presumably to burnish<br />

his prestige as a kind of<br />

Pop artist avant la lettre at the<br />

height of actor Adam West’s<br />

fame as the TV Batman). No,<br />

the best comics in MoMA’s<br />

collection are typically works<br />

that exist outside of the disciplinary<br />

orthodoxy of comics.<br />

Scattered throughout multiple<br />

areas in which the museum<br />

specializes – drawing,<br />

photography, printmaking,<br />

painting, etc. – these works<br />

perform the essential structural<br />

operation of comics,<br />

even if they’ve never been identified as such.<br />

Comics in North America have frequently<br />

been strongly identified with their most commercial<br />

manifestations and with the now ostentatious<br />

fan culture that has developed around<br />

them. Even self-described comics scholars and<br />

critics have often implicitly accepted and ratified<br />

the self-proscribed boundaries of the discipline,<br />

wherever those boundaries might stand<br />

at any given moment. And yet the artists who<br />

have moved comics forward at every stage —<br />

Robert Crumb, Art Spiegelman, Chris Ware,<br />

SUN &<br />

MOON<br />

COMICS<br />

Uncovering MoMA’s<br />

hidden narratives<br />

By Bill Kartalopoulos<br />

KIN-DER-KIDS One of the few examples<br />

of conventional comic art in<br />

MoMA’s collection. There are others, if<br />

one knows where to look. Library of Congress<br />

to name a few obvious examples<br />

— have always understood<br />

comics to be more<br />

than a tradition, more than<br />

an accumulated history, and<br />

certainly more than a professional<br />

field.<br />

These artists and many<br />

more have understood that<br />

comics represent an elegant,<br />

neutral formal approach<br />

— like collage or assemblage<br />

— that can incorporate<br />

all manner of visual<br />

styles, materials, approaches<br />

and meanings into its<br />

method. At the most basic<br />

level, comics are nothing<br />

more nor less than interrelated<br />

images in sequence,<br />

a conceptual practice that<br />

has functioned without a<br />

name for millennia, from<br />

the cave walls of Lascaux<br />

to the tombs of Egypt; from<br />

narrative tapestries to the<br />

pages of countless illuminated<br />

manuscripts; from the<br />

broadsheets and bilderbogen<br />

that are the forgotten wallpaper<br />

of early modern European<br />

life to the celebrated<br />

18th century print sequences<br />

of William Hogarth, and<br />

beyond. Comics may in fact<br />

have been our first conceptual<br />

art form, whose status<br />

derives not from any material<br />

medium or technology but from a core theoretical<br />

strategy.<br />

Sequence and composition<br />

Comics have sometimes been described as<br />

words and images, but that’s not entirely correct;<br />

at the very least, it’s far too literal. The<br />

comics medium rests upon a linear, syntactical,<br />

language-like arrangement of images (regardless<br />

of whether or not they contain language).<br />

But comics begin to function most powerfully as<br />

art when the global, compositional arrangement<br />

INFECTIOUS<br />

COMICOSIS

of these images produces an ultimate meaning<br />

beyond the expository meaning apprehended<br />

in a step-by-step reading. Great comics derive<br />

their most profound meanings from the dynamic<br />

between the linear, propulsive, expository, typographical,<br />

industrial, Apollonian order of sequence<br />

and the compositional, reflective, global,<br />

pre-modern, Dionysian experience of overall<br />

composition. Comics-as-art are, in other words,<br />

the product of the interaction between the structures<br />

that underlie text and image.<br />

Seen in this light, comics are everywhere in<br />

MoMA’s collection. Artistic works of sequence<br />

BAY WATCH<br />

“Untitled,” by<br />

Jan Dibbets<br />

and Shunk-<br />

Kender, 1971<br />

Photos: Shunk-Kender ©<br />

J.Paul Getty Trust. The Getty<br />

Research Institute, Los<br />

Angeles. (2014.R.20) Gift<br />

of the Roy Lichtenstein<br />

Foundation<br />

in memory<br />

of Harry<br />

Shunk<br />

and<br />

Janos<br />

Kender<br />

held by the museum include many wonderful<br />

pieces by Jennifer Bartlett. These include her<br />

“Drawing and Painting” (1974), which in its<br />

very title, speaks to a dual status. This installation,<br />

consisting of 78 12x12-inch carefully arranged<br />

and painted steel plates, performs a dual<br />

sequence. Arranged in a triangular grid, the<br />

piece articulates, step-by-step, the drawing of a<br />

line in its left-to-right procession, while demonstrating<br />

the variation and application of color<br />

and tone in its vertical dimension.<br />

Peter Halley’s brightly colored 1992-1994 “Cell”<br />

prints, depict, in various permutations, the stages<br />

of a mysterious box-like building or object overheating<br />

and exploding, all flowing from a germinal<br />

1992 iteration simply titled (of course) “Narrative.”<br />

Sol Lewitt’s 37-foot-long colorful abstract<br />

comic strip, “Wall Drawing #1144, Broken Bands<br />

of Color in Four Directions” (2004), is currently<br />

on permanent view on one wall in the entrance to<br />

the museum’s film theater. The sequential linearity<br />

of Lewitt’s piece ushers the museum visitor<br />

from the composition-oriented space of the main<br />

galleries to the expositional world of cinema in<br />

the building’s lower level.<br />

Does this sound like a bit much? Here is Lewitt<br />

talking to Saul Ostrow in a 2003 interview<br />

for BOMB magazine:<br />

Serial systems and their permutations<br />

function as a narrative that has to be understood.<br />

People still see things as visual objects<br />

without understanding what they are. They<br />

don’t understand that the visual part may<br />

be boring but it’s the narrative that’s interesting.<br />

It can be read as a story, just as music<br />

can be heard as form in time. The narrative<br />

of serial art works more like music than like<br />

literature. Words are another thing.<br />

FALL 2015

Sunset semiotics<br />

These abstracted, poetic visual narratives are<br />

everywhere in MoMA. In my most recent visit,<br />

I was struck by two pieces in particular, both of<br />

them photographic sequences. The first was part<br />

of the temporary exhibit, “Art on Camera: Photographs<br />

by Shunk-Kender, 1960–1971,” which<br />

examines the collaborative photographic work<br />

of Harry Shunk and János Kender. The bulk of<br />

the exhibit features photographic documentation<br />

of conceptual performance pieces from the 1960s<br />

and ’70s. These include a presentation of the Pier<br />

18 project first organized by artist and curator,<br />

31 45<br />

Willoughby Sharp, in 1971. Sharp invited a group<br />

of 27 artists (including John Baldessari, Gordon<br />

Matta-Clark, Michael Snow, Lawrence Weiner<br />

and William Wegman) to produce performances<br />

and conceptual works at the then-disused<br />

Manhattan dock. These performances were all<br />

photographically documented by Shunk-Kender.<br />

Needless to say, many of these documents<br />

of time-based physical performance pieces, arranged<br />

as serial images, necessarily present as<br />

photo-comics (as does the duo’s earlier collaboration<br />

with Yves Klein, “Leap into the Void”).<br />

There is much to visually read in this exhibit.<br />

But the piece that drew me the most was<br />

Shunk-Kender’s untitled collaboration with<br />

Dutch artist Jan Dibbets. Unable to physically<br />

participate in the Pier 18 performances, Dibbets<br />

sent Shunk-Kender a note with instructions: He<br />

asked the photographers to set up a camera at a<br />

point on the pier from which the sunset would<br />

be visible. He then provided instructions for<br />

two specific sequences of photographs. The first<br />

would produce a simulated sunset, progressively<br />

darkening the sky using a series of f-stops that<br />

limited the amount of light exposed to film over<br />

the course of 12 images. The second series of images<br />

recorded the actual sunset, the disc of the<br />

sun visible and setting in 12 roughly parallel images.<br />

The paired sets of images were hung in a<br />

two-row grid, progressively going from light to<br />

dark, with the simulation of each phase of sunset<br />

above a consonant image of actual sunset.<br />

The two rows of images present a fascinating<br />

grid. The top row, with its manipulated light,<br />

calls into question the illusory nature of apparently<br />

diegetic sequence while affirming the viability<br />

of a structural approach to sequence. This<br />

recalls various structural comics, including experimental<br />

early work by Spiegelman (such as

“Little Signs of Passion” and “Don’t Get Around<br />

Much Anymore”) inspired by his contact with<br />

filmmakers including Ken Jacobs and Stan Brakhage.<br />

More globally, the two rows together can<br />

be read horizontally as a sequence of vertically<br />

paired images that underline the work’s investigation<br />

into truth and illusion, maintaining a dynamic<br />

balance between artifice and nature.<br />

But the comics-trained eye finds a third reading.<br />

Reading the first row in isolation, with its<br />

apparition of false sunset, from light to dark, the<br />

eye is drawn downward to the tonally connected<br />

final image in the bottom row. The disc of the<br />

and setting in the same westward sky. Where<br />

Dibbets and Shunk-Kender artificially impose a<br />

natural cycle onto a sequence, the second narrative<br />

piece that caught my attention artificially<br />

imposes sequence onto a natural cycle.<br />

Necessary and arbitrary<br />

“Lunar Alphabet II” by Argentine artist Leandro<br />

Katz, is permanently on display in the museum’s<br />

Painting and Sculpture gallery. Approximately<br />

2.5 feet wide and 9 feet tall, the gelatin<br />

silver print presents a 9x3 grid of images of the<br />

moon in consecutive phases, each labeled with a<br />

sun, invisible above except by implication, finally<br />

becomes visible, and the iconic subject draws<br />

the eye from right to left. Step by step, the sun<br />

now rises and illuminates the sky, ending at the<br />

left hand side of the bottom row with a bright,<br />

washed out image nearly identical to that above<br />

it, leading the eye upward again to repeat the<br />

cycle. The two parallel sets of images prompt a<br />

surprising circular reading order, evoking the<br />

endless cycle of sunrise and sunset. But this image<br />

of a celestial rotation is the artificial result of<br />

a process, and quickly startles the mind with its<br />

impossibility: the absurd image of a sun rising<br />

letter of the alphabet, from A to Z (including the<br />

Spanish diacritical Ñ for 27 characters).<br />

Katz’s piece addresses the arbitrariness and the<br />

necessity of both semiosis and sequence. Each<br />

alphabetical character functions like a caption in<br />

a comics panel, and its association with each assigned<br />

phase of the moon is arbitrary, imposed<br />

only by intentional juxtaposition. The harmonious<br />

disjunction between text and image here<br />

brought to mind the détourned comics of the Situationist<br />

movement, which substituted political<br />

texts in the word balloons of banal comic strips,<br />

subverting social messages while pointing out<br />

FALL 2015

semiotic fault lines in hybrid texts. The sequence<br />

of moon images in this piece is both necessary<br />

and also arbitrary; necessary because each subsequent<br />

phase follows that which precedes it,<br />

and arbitrary because the linear representation<br />

of a cyclical pattern must choose beginnings and<br />