Ripcord Adventure Journal 1.4

After only four issues we appear to have been exiled voluntarily to beautiful Siberia, a region as vast as it is geographically diverse; from the pen of the first woman to cycle across the "new" Russia we travel the old stock route across Australia, from well to well and from story to story broadening our understanding of this island continent. The drive to explore, the reason to adventure is discussed before taking us underground to the vaulted caverns and flooded passages of the deepest cave system in the Americas to emerge suddenly back in to the full light of an Andean stratovolcano summit, the nearest point to space on earth that two companions can reach, until finally, the long road that this issue takes, brings us to the last place in Yemen. We aim to be the home of authentic, adventurous travel, which serves as a starting point for personal reflection, study and new journeys.

After only four issues we appear to have been exiled voluntarily to beautiful Siberia, a region as vast as it is geographically diverse; from the pen of the first woman to cycle across the "new" Russia we travel the old stock route across Australia, from well to well and from story to story broadening our understanding of this island continent. The drive to explore, the reason to adventure is discussed before taking us underground to the vaulted caverns and flooded passages of the deepest cave system in the Americas to emerge suddenly back in to the full light of an Andean stratovolcano summit, the nearest point to space on earth that two companions can reach, until finally, the long road that this issue takes, brings us to the last place in Yemen.

We aim to be the home of authentic, adventurous travel, which serves as a starting point for personal reflection, study and new journeys.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Volume 1 | Number 4 | September 2015<br />

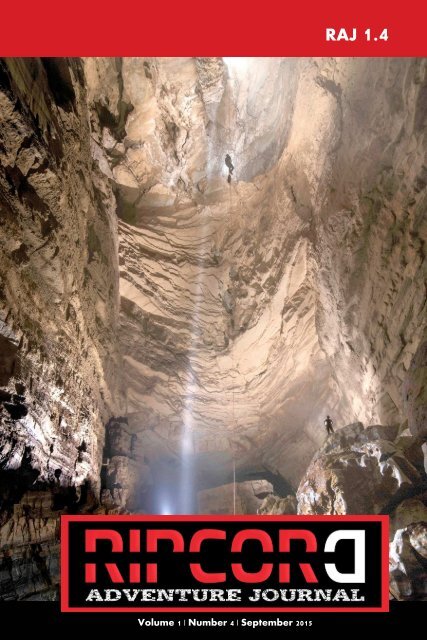

RAJ <strong>1.4</strong>

A Letter from the Editor<br />

Welcome to <strong>Ripcord</strong> <strong>Adventure</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>.<br />

After only four issues we appear to have been exiled voluntarily to<br />

beautiful Siberia, a region as vast as it is geographically diverse; from<br />

the pen of the first woman to cycle across the "new" Russia we<br />

travel the old stock route across Australia, from well to well and<br />

from story to story broadening our understanding of this island<br />

continent. The drive to explore, the reason to adventure is discussed<br />

before taking us underground to the vaulted caverns and flooded<br />

passages of the deepest cave system in the Americas to emerge<br />

suddenly back in to the full light of an Andean stratovolcano<br />

summit, the nearest point to space on earth that two companions<br />

can reach, until finally, the long road that this issue takes, brings us<br />

to the last place in Yemen.<br />

We aim to be the home of authentic, adventurous travel, which<br />

serves as a starting point for personal reflection, study and new<br />

journeys.<br />

On behalf of the editorial, writing and design team I wish to thank<br />

our sponsors Redpoint Resolutions (particularly Thomas<br />

Bochnowski, Ted Muhlner and Martha Marin), the World Explorers<br />

Bureau USA (Charlotte Baker-Weinert) and the team at<br />

<strong>Adventure</strong>.com for their continued support.<br />

Tim Lavery<br />

General Editor, <strong>Ripcord</strong> <strong>Adventure</strong> <strong>Journal</strong><br />

www.ripcordadventurejournal.com<br />

www.ripcordtravelprotection.com

<strong>Ripcord</strong> <strong>Adventure</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> © February 2015 by Redpoint<br />

Resolutions & World Explorers Bureau. All articles and images ©<br />

2015 of the respective Authors and photographers.<br />

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,<br />

distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including<br />

photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical<br />

methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher,<br />

except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews<br />

and certain other non-commercial uses permitted by copyright law.<br />

For permission requests, general enquiries or sponsorship<br />

opportunities, contact the publisher:<br />

<strong>Ripcord</strong> <strong>Adventure</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>: info@ripcordadventurejournal.com<br />

Supporting the following Organisation

"The memory of a cave I used to know at<br />

home was always in my mind, with its<br />

lofty passages, its silence and solitude, its<br />

shrouding gloom, its sepulchral echos, its<br />

flitting lights, and more than all, its<br />

sudden revelations of branching crevices<br />

and corridors where we least expected<br />

them."<br />

Mark Twain<br />

"Innocents Abroad"

RIPCORD<br />

ADVENTURE<br />

JOURNAL<br />

<strong>1.4</strong><br />

Editorial Team<br />

Shane Dallas<br />

Tim Lavery<br />

Ami Gigi Alexander<br />

Terry Sharrer<br />

Paul Devaney<br />

Featuring<br />

Sophie Ibbotson<br />

Max Lovell-Hoare<br />

Tor Torkildson<br />

Robb Saunders<br />

Kate Leeming<br />

Bill Steele<br />

John Lavery<br />

Jonathan Sterck<br />

Tim Mackintosh-<br />

Smith<br />

Publishers<br />

Redpoint Resolutions<br />

& World Explorers<br />

Bureau<br />

WWW.RIPCORDADVENTUREJOURNAL.COM

Contents<br />

Guest Editorial:<br />

The Long Road to <strong>Adventure</strong><br />

Robb Saunders<br />

Fifty years of continuous<br />

exploration<br />

Bill Steele<br />

Out there and back<br />

Kate Leeming<br />

50<br />

Jonathan Sterck<br />

Self Exile in Siberia<br />

Sophie Ibbotson & Max Lovell-<br />

Hoare<br />

The last place in Yemen<br />

Tim Mackintosh-Smith<br />

Book review: Mad, Bad &<br />

Dangerous to Know<br />

Book review: The Flying Carpet<br />

Contributors and credits<br />

1<br />

17<br />

35<br />

79<br />

93<br />

111<br />

131<br />

135<br />

139

The long road<br />

to adventure<br />

Robb Saunders<br />

1

2

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

11am, I was certain that I must have travelled well over ten<br />

kilometers since I left this morning. There could be no way that I<br />

had been walking for less than that. There was only one road to<br />

travel on for the next few days. Its gradient forever changing, like<br />

the sun trying its utmost to make itself known through the thick<br />

grey clouds that were sprinkling its watery remnants down upon<br />

me. Snow too had become more frequent as I made my way along<br />

the winding, lonesome road. I would stop occasionally to take<br />

photos of the vast, unpopulated landscape, and one or two selfies of<br />

myself to hopefully one day prove my adventurous nature to my<br />

future grandchildren. With the fast paced lives we currently live<br />

who knows if they will ever see such wonders as this.<br />

I was becoming concerned by this stage, the road was slowly<br />

becoming the only terrain for me to travel, and yet was also<br />

becoming the most dangerous. Bridges were more apparent the<br />

higher up the mountain I went, they supplied no space for<br />

pedestrians and thus forced me into the driving lanes. If cars, or<br />

worse, trucks were to appear whilst on these bridges I would have<br />

no place to move but hang myself over the railing and hope the<br />

residual force of the big metal vehicles wouldn’t thrust me off.<br />

It was then that I decided to try my luck at climbing down into the<br />

gully and crossing the river below. “How hard could it be?” I<br />

thought to myself whilst standing on the nice solid road. I stepped<br />

into the muddy grass and shrubbery laden wilderness, leaving the<br />

makings of civilization behind. Getting down needed to be carefully<br />

thought out, and slowly executed. One misstep or wrong grasp at a<br />

weak hanging tree branch and down the hill like Humpty Dumpty I<br />

will go. No one knowing I would be down there, most likely<br />

discovered first by the supposed brown bear I had been told about<br />

since arriving.<br />

Everything was wet and slippery. It smelt like moss and petrichor. I<br />

looked up and quickly realised that the bridge was now high up<br />

above me. A new feeling of terrified freedom that I have never<br />

known was both confronting and sensational. In that moment, no<br />

3

one on this enormous planet knew I was there. I could have held up<br />

there for weeks and never see a human soul, only to hear them echo<br />

over the bridge in the distance above. I was however on a schedule<br />

and needed to make ground quickly as this detour was eating time.<br />

When I came closer to the river I discovered something, I was stuck.<br />

In order to continue, I needed to get down to the river bed, the<br />

obstacle was manmade of vertical concrete. It resembled the walls of<br />

a dam. I contemplated jumping down but with my heavy 25kg pack<br />

it would either end badly for myself or worse, my precious<br />

expensive equipment, hence why I wasn’t going to drop my pack<br />

down first and try and climb freely. My best shot was a tree I<br />

spotted in the distance. I figured if I were to fall accurately toward<br />

the thickest part of the tree, leaving my feet firmly placed on the<br />

edge I would then be able to parkour style my way down using it as<br />

support against the concrete wall.<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

At this point I could no longer tell if it was sweat or rain on my<br />

palms. Everything was wet and the sky was on the cusp of pouring.<br />

I stopped over analyzing my actions and leaned forward over the<br />

edge, arms out ready for impact. What was I doing here!<br />

The auction of my apartment didn’t go well, a handful of potential<br />

buyers and not one made an offer. I wanted to scream I was so<br />

frustrated. The planning was complete, everything was mapped out,<br />

and all I needed was the funds to put it into fruition. The funds I<br />

had hoped to receive from the sale, the sale that had been promised<br />

to me by the real estate agent, who was losing his credibility by the<br />

day.<br />

My body was still stuck in Australia, my mind was already trekking<br />

the vast landscapes of an unknown world. I had made it, my first<br />

time traveling alone, my first proper adventure! I could dictate<br />

everything I wanted to do, and what I wanted to do was walk. My<br />

goal was to land at the top and walk for three months down this<br />

ancient landscape.<br />

I landed on the 17th of May. It was wintery cold and the air was<br />

4

5

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

filled by a thick fog. I decided I would spend the weekend<br />

composing myself before beginning my trek. One, to let everything<br />

sink in, and two, to spend some time exploring the strangely<br />

familiar but somewhat different city that I was in. So when I arrived<br />

at the hotel I decided that instead of recuperating in my room I<br />

would throw my bags down and head out. To which I discovered<br />

that the main social hub nearest me was the train station. Over time<br />

it dawned on me that having a shopping and restaurant district<br />

intertwined with the railway system was a common occurrence and<br />

it surprises me that they have not quite picked up on that logical<br />

enterprise back home. I walked around the restaurant district for<br />

somewhere to eat and came upon an Irish pub. Mainly out of a<br />

traveler’s curiosity to see how they portrayed it, I went in and<br />

ordered a pint and sat at the bar. The smell of tobacco infused with<br />

cooked meat and stale beer consumed the air. It was dark and had<br />

the feel of an old establishment even though it was inside a shopping<br />

mall and could not have been older than ten years. I heard many<br />

English speaking westerners in the bar. As I had just arrived I had<br />

no desire to socialize with them. I was also content with being alone<br />

with my thoughts.<br />

A little while later the barman approached to inform me that I was<br />

invited to sit with a group at the nearby table. I turned to see they<br />

were all women, around my age, enjoying after work refreshments<br />

and snacks. They waived me over so I kindly obliged.<br />

“Hello.” I said trying to enunciate as clearly as possible.<br />

“Hello.” They replied gleefully and as cautiously as possible to not<br />

embarrass themselves with the foreign tongue.<br />

I pulled up a chair and sat down. I can only recall one name of the<br />

women. Seiko, she was strongest at English so she was most curious<br />

to know my intentions about why I was in her homeland. To which<br />

I began explaining that I had just arrived this evening and about to<br />

embark on a three month journey walking south. Once Seiko<br />

relayed what I said back to her friends they seemed confused, they<br />

6

could not understand the purpose of such a trip. “Why not take a<br />

train, a bus, a car or fly to the destinations you want to see?” What<br />

they didn’t understand and I guess myself at the time was that I had<br />

not really thought about where I was going to go, the adventure<br />

itself was the destination.<br />

The impact was hard, but my hands stayed true, my arms however<br />

underestimated the added weight and almost failed me. I shimmied<br />

down and was back on solid ground. The rain was well and truly<br />

making its presence known but being wet was not a concern I<br />

carried with me. I traversed the river’s edge looking for a safe and<br />

shallow way across. There was a line of tall rocks about ankle deep<br />

that were situated the full length across. I was happy to be able to<br />

put my new waterproof hiking boots through some proper tests<br />

during this challenging event. I stepped onto the first rock. The<br />

water was moving a lot quicker than anticipated but nothing to<br />

worry myself over. I moved to the next rock. Success! I managed to<br />

frolic my way across rock to rock like a gazelle, I was becoming so<br />

proficient that my socks were not yet wet, which, as is Murphy’s<br />

Law, due to my overconfidence I forgot a key point. It is said that a<br />

rolling stone gathers no moss. So what do stones that don’t move<br />

do? It was the last rock, which was above the surface of the water, I<br />

hopped, skipped and slipped on its mossy face and submerged my<br />

legs into the water. My perfect game was ruined, it had happened,<br />

the socks were wet!<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

I pulled myself into the river bank and began climbing my way back<br />

up to the road. I was now on the other side of the bridge. I decided<br />

after that time consuming endeavor that I would risk it on the next<br />

bridge and try and make a run for it, but first, I needed to a new pair<br />

of socks!<br />

From where I lay, on a hard, sterile and cold bed in the emergency<br />

department of the Epworth hospital in Melbourne, Australia, my<br />

outlook didn’t look promising. Everything could be over before it<br />

began. Unable to sit up, unable to move at all without my spine<br />

feeling like it was trying to rip itself out of my body, I lay there, the<br />

7

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

hospital curtain closed but never enough to give me the privacy I<br />

needed to quietly sob. In only a few months I was supposed to be<br />

on an adventure, now it may not happen.<br />

I had damaged my back that evening. Twenty minutes into starting<br />

my shift at work. A task I undertake every day, a task that I had<br />

mentioned many times to my superiors that it is hazardous to do<br />

alone. You would think something as simple as moving a table<br />

wouldn’t be difficult, but these are crafted from a thick glass with<br />

long, solid timber legs. This particular day I moved it and the dam<br />

leg broke! I instinctively thrust down to catch it before the glass<br />

broke on the floor, good thing was I caught the glass; the only thing<br />

that broke was me. I was stuck in a dark, moldy and humid concrete<br />

store room for twenty minutes before I was discovered, placed into<br />

a wheelchair and driven to the hospital. In the past I guess we have<br />

all wished for a small minor injury to get us out of work. This was<br />

not one of those days.<br />

The doctor came back in. Gave me some strong painkillers and<br />

orders to go home and rest for a couple of weeks and check in with<br />

my doctor. I asked about how it would affect my travel plans...<br />

It was not good news.<br />

I decided that camping may not be as fun as everyone makes it out<br />

to be. Can you still be an adventurer and not like camping? I woke<br />

up, saturated by the watery dew from the inside of the tent, it must<br />

have dropped to below 5 degrees Celsius overnight. I had put my<br />

thermal undergarments and all my other items of clothing on during<br />

the night to stay warm. I even put my rain jacket on in the hopes of<br />

staying dry, but the cold weather and the humidity from my body<br />

heat was causing some extreme indoor climate issues. The sleep I<br />

had was more broken than I anticipated but I hadn’t been killed by<br />

the strange noises outside my tent, so that was a plus. I could not<br />

tell if the sun had risen or if that was just a streetlight shining<br />

through, the sound of children became more apparent the longer I<br />

lingered so it must have been morning. How late in the morning<br />

8

9

10

was answered once I stepped out of the tent and discovered the<br />

grass I had made camp in last night was actually a baseball field, and<br />

it was game day. Great!<br />

Ten days had gone by. My back was straining at every physical<br />

movement but bearable to walk slowly around the house. The pain<br />

didn’t want to leave so eagerly like I had hoped. Maybe I’ve<br />

overestimating myself. By this stage the stabbing sensations were<br />

hurting my sense of adventure more than my body. “I should be at<br />

work, I should be planning my trip now!” I had an abundance of<br />

time at home to plan for the trip, but all I achieved was binge<br />

watching episodes of Game of Thrones, The Walking Dead and<br />

eating too much delicious ice cream. My motivational jar was as<br />

empty as a tip jar at a bank.<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

The trip was over before it begun.<br />

My damn back! Three weeks into my walk and it was all starting to<br />

trouble me once more. I had some painkillers in my first aid kit with<br />

the hopes that I would not need them, or at the very least not for<br />

my back, I had to power through, I trekked close to forty<br />

kilometers the previous day, back pain will not defeat me!<br />

Camping in a baseball field for the night wasn’t exactly comfortable<br />

so the fatigue was setting in. I had walked almost eighteen<br />

kilometers this morning from where I departed in front of the<br />

shocked parents and utterly intrigued and excited young baseball<br />

players. I was only planning on averaging that distance a day, but<br />

my destination was eighty kilometers away, and I needed to get<br />

there in 48 hours.<br />

Having passed the mountainous terrain and with winter now<br />

winding to a close the sun was taking advantage. I was becoming<br />

tiresome and hot. I had changed my socks once already and<br />

bandaged up my blistered feet. I was walking along the coast now<br />

and the smell of the ocean reminded me of home. Sitting on the<br />

beach in Australia and digging trenches in the sand for the water to<br />

11

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

travel through. Yes I’m an adult. The sand on this beach however<br />

didn’t feel like home. It felt more solid, like it had been mixed with<br />

clay. The colour was also a dark brown instead of a breezy yellow.<br />

The good thing was it definitely made walking easier, and when a<br />

gust of wind came along the sand wouldn’t give in and fly up to<br />

attack my eyes like microscopic Hulks. I was making ground<br />

quickly and forgot myself, due to getting lost in the moment I lost<br />

the road I was following, which was no longer in sight.<br />

The human body is a strange and wonderful machine. One minute<br />

you are struggling with body movement and the next its back up to<br />

being fully functional. In my case I was back to training, walking<br />

the two hour stroll home from work every day, only minor soreness<br />

along the way. The light at the end of the tunnel was becoming<br />

much larger. All I needed to accomplish now was finding the money<br />

to make it through.<br />

Bang! Smash!<br />

The sound that shot me out of the hotel bed and onto my shaking<br />

feet. Disorientated, for a second I thought I was still back home in<br />

my old room, in the apartment I had once owned, the apartment I<br />

sold to be right here, experiencing this terrifying stuff.<br />

Crack! Kick!<br />

I knew dipping into my budget to splurge a little extra cash for a<br />

hotel room with a fluffy double bed would come back to haunt me,<br />

I didn’t think it would be literal. A shadowy figure was peering<br />

under my door from the hotel hallway. Constantly turning the<br />

locked door handle whilst banging the wood. I stood, frozen in fear<br />

and confusion. I thought to myself, “I have worked for hotels for<br />

almost ten years, I have witnessed many strange things during my<br />

time, and I’ve even had to break into rooms on many occasions”.<br />

Which made me realize, this isn’t an employee, this is someone<br />

trying to get into my room, maybe to me, maybe he wants my<br />

camera, my laptop, my ice cream! In those small minute seconds<br />

12

that I was frozen, all kinds of terrible thoughts entered my mind. I<br />

grabbed my pocket knife from the desk and walked over to the<br />

door. A few more minutes and this person will be inside. In a tone<br />

of voice so deep it could have been mistaken for James Earl Jones<br />

these words sprayed out of my mouth…<br />

“HEY! GET LOST!”<br />

The shadow was motionless, some silent phrases were said that were<br />

too soft, and also not English for my ears to decipher. The silence<br />

became more terrifying than the banging, I was paralyzed once<br />

more. It felt as though we were staring at one another through the<br />

solid wooden door. Both motionless, like a game of chicken,<br />

whoever moved first would lose and the victor would get the<br />

comfort of the soft warm bed, and my ice cream. As I was awoken<br />

in the middle of a REM cycle my mind was contemplating all<br />

possibilities, be it the logical reality or the supernatural. What felt<br />

like an eternity went by and still no movement, soon frustration was<br />

beginning to push my fears aside and prepare myself for<br />

confrontation. I wanted to go to bed, I wanted to sleep, this time I<br />

needed some Clint Eastwood style vocals.<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

“Hey, get out of here asshole!” I said sternly.<br />

I walked over to the door and began to make door handle noises. I<br />

knew if that didn’t work the next move would be to open the door<br />

and hope this person was smaller than me, didn’t have a weapon,<br />

and didn’t know karate.<br />

The shadow disappeared from under the door. I heard the sounds of<br />

footsteps fading in the distance. With my frustration now pounding<br />

on my ego to go do something about this disturbance, I opened the<br />

door. The hallway was so brightly lit it took a moment for my eyes<br />

to adjust. I began to walk towards the elevators where my disturber<br />

would be waiting when suddenly I realized something. I’m hardly<br />

clothed, and my hotel key was sitting smugly on the cabinet in my<br />

room laughing to itself at my stupidity. I hadn’t heard the door close<br />

13

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

yet, I ran back to my room at top speed. I could see the gap closing<br />

between two universes, one with me in my warm, sleep filled<br />

solitude and the other of me, explaining my embarrassment barely<br />

clothed to the front desk attendant.<br />

April 2014, after over six months on the market, my apartment was<br />

finally sold. It was my ticket out. My Walter Mitty moment. Over<br />

the next month I quit my job, collected my travel gear and said<br />

farewells to my loved ones. It was time.<br />

Time for me to disappear.<br />

To a distant land over the seas.<br />

To a land that thrives on respect and honor. A civilization centuries<br />

old before my country had even been discovered by the British.<br />

To a land where tradition meets innovation.<br />

To the land of the rising sun.<br />

Japan.<br />

Having spent three months in this wonderful country, my time here<br />

was near its end. The experience will not leave me any time soon<br />

and I will be forever grateful to the people I met and who helped me<br />

along the way.<br />

Like the kind man at the convenient store who saw me sitting<br />

outside during one of my many breaks, who had taken it upon<br />

himself to come outside and bring me a cold bottle of sparkling<br />

water, asking nothing in return but a smile.<br />

To the women working at a petrol station who saw me walking late<br />

one afternoon, noticeably tired. They asked me where I was going<br />

to which I replied I was looking for a hotel nearby. They asked me<br />

to wait, they brought me some water and ten minutes later a taxi<br />

14

arrived for me. Perplexed I looked around to see the women smiling<br />

and waving.<br />

To the two fish mongers in the early days of my journey, my body<br />

still was adjusting to the food, which introduced an issue that<br />

requires immediate attention in the form of a restroom. As I walked<br />

into your shop I fell, to which you both helped me to my feet<br />

without hesitation as to why a strange man was entering. When<br />

discovering of my predicament you invited me into your home in<br />

the back, introduced me to your family and let me use your private<br />

bathroom, no questions asked. Upon leaving you would not accept<br />

what little currency I had on me at the time, you gave me a cold<br />

drink and sent me on my way.<br />

When looking back on my adventure in Japan, from Sapporo to<br />

Osaka, it won’t be the landmarks, the tourist attractions or the<br />

landscape that will bring a smile to my face. It will be small<br />

moments such as these that I will cherish with fond memories.<br />

15

"As soon as you have crossed your doorstep<br />

or the county line, into that place where<br />

the structures, laws, and conventions of<br />

your upbringing no longer apply, where<br />

the support and approval (but also the<br />

disapproval and repression) of your family<br />

and neighbors are not to be had: then you<br />

have entered into adventure, a place of<br />

sorrow, marvels, and regret."<br />

Michael Chabon<br />

"Gentlemen of the Road"<br />

16

50 years of<br />

continuous<br />

exploration:<br />

Sistema Huautla, the<br />

Deepest Cave in the<br />

Americas<br />

Bill Steele<br />

8<br />

17

18

In the summer of 1965 three young Texas weekend spelunkers<br />

drove a low riding car up a newly constructed dirt road in the Sierra<br />

Mazateca of the northern part of the southern Mexico state of<br />

Oaxaca. They were seeking caves with the potential to be the<br />

deepest in the Americas. They had it right. As soon as they got in<br />

the vicinity of Huautla de Jimenez, they started finding cave<br />

entrances.<br />

The next year they returned with ropes and drove to the other side<br />

of the mountain town of Huautla. Immediately they found two<br />

large cave entrances in the bottom of deep sinkholes. These are the<br />

primary entrances of Sistema Huautla, a mega cave system with 20<br />

entrances, 7<strong>1.4</strong> km (44 miles) in length, 1,554 m (5,097 feet) in<br />

depth, making it the deepest known cave in the Western<br />

Hemisphere, the 8th deepest cave in the world, the longest of the 16<br />

deepest caves in the world, and what many cavers feel is the greatest<br />

cave on Earth.<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

Fifty years later, over thirty expeditions, seven of them Explorers<br />

Club flag expeditions, these exploration of these caves has renewed<br />

momentum. Late March to early May 2015 forty-seven speleologists<br />

from seven countries: USA, Mexico, Great Britain, Australia,<br />

Poland, Switzerland, and Romania participated in a six week<br />

expedition in varying lengths of stay. There was a long list of<br />

objectives, including exploring unexplored passages by “checking<br />

out leads” indicated in past underground survey field notes.<br />

The restarted project exploring and studying the caves of the<br />

Huautla de Jimenez, Oaxaca, Mexico has been given the name of<br />

Proyecto Espeleologico Sistema Huautla (Huautla system<br />

speleological project), or PESH for short. PESH was launched in<br />

2013 with the objectives of extending the mapped length of the cave<br />

system from the then 65 km to over 100 km, the depth from the<br />

current 1,554 m to 1,610 m (a vertical mile, or 5,280 feet), and all the<br />

while maintaining “full speleology”, meaning studies and papers<br />

written on the various study disciplines of speleology: geology,<br />

hydrology, biology, paleontology, archaeology, and exploration<br />

19

techniques.<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

The exploration of the Huautla caves has gone through phases. The<br />

years 1965-1970 saw several expeditions organized by cavers from<br />

the USA and Canada, and the establishment of the cave Sotano de<br />

San Agustin as the deepest cave in the Americas at 600 m in depth. It<br />

was felt that the cave was fully explored.<br />

In 1976 a group went to see this cave and check out a “lead”<br />

indicated on the map published by the Canadians a few years<br />

before. In caving jargon a “lead” is a possible unexplored passage. A<br />

lead is indicated on a cave map with broken continuing lines and a<br />

question mark. Maybe it goes on, and maybe it doesn’t. The reason<br />

the lead had not been entered eight years before was that it was very<br />

remote, taking two days of underground travel to get to it, and there<br />

was a very difficult overhung climb about five meters high. This<br />

climb was successfully climbed, a passage did indeed continue, and<br />

since then the cave has been explored from a length of two miles<br />

then to 44 miles now and the depth is two and a half times deeper.<br />

After the 1976 expedition there was one expedition after another<br />

most years until 1994. The 1994 expedition was a major three<br />

month-long effort that resulted a book being written about it,<br />

“Beyond the Deep”. The farthest the 1994 expedition reached was a<br />

deep pool of water at a depth of 1,475 m below the highest point<br />

reached in the cave system. The pool was extremely remote and<br />

required not only hundreds of meters of technical rope work, but<br />

long dives underwater too, with rebreathers and sophisticated scuba<br />

gear, and camping in the cave beyond the reach of any means of<br />

communication with the surface.<br />

Between 1994 and 2007 there were a few scattered expeditions to the<br />

Huautla caves, but several of those years saw no activity. The<br />

Huautla cavers were exploring caves elsewhere in Mexico, USA,<br />

China, Puerto Rico, etc.<br />

Then came 2013 and the big British-led expedition. Young, very<br />

20

active, British cave explorers sought logistical information from me<br />

and others to mount their own expedition to dive in the deep pool,<br />

called a “sump” in caver parlance, at the bottom of the cave.<br />

Through the years leading up to this expedition Sistema Huautla<br />

had been surpassed in depth by a cave not far south of it, on a high<br />

mountain range separated from the Huautla plateau by a deep<br />

canyon, and this cave, Sistema Cheve, had a surveyed depth only<br />

nine meters deeper than Sistema Huautla.<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

The Brits had a successful expedition and explored 80 m deep in the<br />

pool of water, using mixed gases for breathing. Eighty meters was<br />

the limit what they could do with the gases they were breathing so<br />

they ended the dive there, with the water-filled passage descending<br />

at least another 20 meters they could see with powerful underwater<br />

dive lights. Sistema Huautla was once again the deepest cave in the<br />

Western Hemisphere at 1,554 m from the highest point humanly<br />

reached in the cave, to the lowest point humanly reached. That’s the<br />

way it’s figured in a deep cave.<br />

Tommy Shifflett from Virginia and I joined the British expedition<br />

for the last part of it. We had our own<br />

area to look at, looking for unexplored passages, and found over<br />

half a kilometer of lovely decorated, unexplored passages after<br />

doing an aid climb across the top of a shaft.<br />

Tommy and I talked while we were there together about how much<br />

we love the caves and the area of Huautla, Oaxaca, and there is<br />

much remaining to do. So in the airport in Oaxaca, as we waited for<br />

our respective flights back to the USA, we sketched out a plan for a<br />

restart of annual expeditions to Sistema Huautla and other caves of<br />

the area.<br />

We decided to give our project a new name – in Spanish this time –<br />

Proyecto Espeleologico Sistema Huautla, and wrote down our<br />

goals:<br />

- To explore, survey, and conduct a comprehensive speleological<br />

21

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

study of the Sistema Huautla area caves.<br />

- Conduct speleological studies to include exploration and mapping,<br />

cartography, geology, hydrology, biology, paleontology,<br />

archaeology, and equipment and technique development.<br />

- Support Mexican cave scientists in field research.<br />

- Conduct annual springtime expeditions for ten years 2014-2023.<br />

- Survey data kept current.<br />

- Goal of reaching 100 km in length.<br />

- Goal of reaching 1,610 m in depth, which is 5,280 ft., a vertical<br />

mile.<br />

- All results published.<br />

All of this is easy to say, but to say we’re going to have annual<br />

expeditions for ten years, it’s very important that the first one be<br />

successful. The first PESH expedition, in 2014, was successful on<br />

several fronts. Diplomacy at the state, municipio, and agencia levels<br />

was for the most part fruitful, with permission granted to go caving<br />

in the area for three years. One area remains a challenge due to the<br />

resident Mazatec people’s beliefs in cave spirits and what might<br />

happen if they are angered by foreigners going in caves no one has<br />

ever entered. A plan has been formulated to do diplomatic work to<br />

deal with this issue, but it’s going to take several years to overcome,<br />

if it’s ever overcome.<br />

The area to the east of the known passages of Sistema Huautla, was<br />

an objective, to search for new cave entrances that might descend<br />

deep and connect with the cave system below. Around 20 new pits<br />

and caves were explored and mapped, without anything going very<br />

far or deep. A cave southeast of known passages in the system<br />

shows promise with strong airflow and the exploration of it will<br />

continue during the 2016 expedition.<br />

Oscar Franke, Ph.D., professor of biology, a noted arachnologist<br />

and scorpion expert and a professor at the National Autonomous<br />

University of Mexico (UNAM) in Mexico City, joined our<br />

expeditions in 2014 and 2015 and brought along three graduate<br />

students each time. They are thrilled that they have collected twelve<br />

22

new species of cave life, including new species of tarantula, new<br />

species of harvestmen spiders, and a new species of scorpion in the<br />

caves. They will return in 2016.<br />

An important paleontological site was found in a cave as well. In a<br />

series of large adjoining rooms in a cave we had not visited in over<br />

30 years, not far from the village where we rent houses, large bones<br />

were noticed in a talus cone of dirt on the floor. We think there must<br />

have been an entrance above the bones at one time in the distant<br />

past. Based on photographs taken with scale and sent to a<br />

professional paleontologist in Mexico City, he feels that at least one<br />

of the animals is an extinct Pleistocene ground sloth. A graduate<br />

student of his joined us for a week this year and plans to return for a<br />

longer amount of time in 2016 to excavated the 1 ½ m tall cone of<br />

bones and other ancient surface debris.<br />

Halfway through the first PESH expedition in 2014, five cavers<br />

arrived with packs already prepared to go underground and camp in<br />

the La Grieta section of Sistema Huautla. La Grieta, meaning “the<br />

crack”, is a significant section of Sistema Huautla. It’s over 700 m in<br />

depth to where it connects to the system and has tributaries feeding<br />

into it that were initially explored in 1977, but no one had been back<br />

to them since then.<br />

Taking underground backpacks, five cavers went into La Grieta to<br />

stay underground for nine days. They set up a remote camp and<br />

explored an upstream tributary initially explored without finding an<br />

end in 1977. They succeeded in discovering and mapping 1.6 km of<br />

new passages. This was Kasia Biernacka of Poland, Gilly Elor,<br />

Corey Hackley, John Harman, and Bill Stone of the USA. Three of<br />

them camped underground for seven days and two of them for nine.<br />

Their most significant discovery was a passage extending over 1.5<br />

km to the north, directly toward the highest topography in the area.<br />

They turned around in 20 X 20 m borehole passage because they<br />

were running low on food and battery power for their lights. This<br />

continuing passage is a major objective for 2016.<br />

23

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

The second annual PESH expedition took place from March 23 –<br />

May 5, 2015 with 47 speleologists and support people from ten<br />

counties; the United States, Mexico, England, France, Germany,<br />

Poland, Switzerland, Austria, Romania, and Australia.<br />

Cavers explored the upstream sump (a sump is a cave passage with<br />

water to the ceiling (necessitating scuba gear) in Red Ball Canyon at<br />

the 700 m (2,296 foot) deep Sotano de San Agustin section of<br />

Sistema Huautla, an area not seen since 1979. On the far side of<br />

three sumps, 30 m, 30 m, and 5 m long, two cavers, Andreas<br />

Klocker of Australia, and Zeb Lilly of Virginia in the USA, direct<br />

aid climbed 180 m (590 feet) vertically beyond it. It continues to go<br />

up into the unknown and is getting bigger.<br />

They also discovered a new and potentially extensive new part of<br />

the La Grieta section of Sistema Huautla. Dubbed Mexiguilla due to<br />

its similarity with New Mexico’s (USA) Lechuguilla Cave (one of<br />

the world’s most beautiful caves), the area has the best formations<br />

yet found in the 44 mile long cave system.<br />

Besides Sistema Huautla, teams explored and mapped small caves in<br />

the area in hopes of opening up new sections of Sistema Huautla.<br />

Progress was also made with public relations efforts to gain access<br />

to unexplored entrances where local Mazatec Indians believe cave<br />

spirits reside and fear offending them, resulting in their corn not<br />

growing well or their children getting sick. At the suggestion of a<br />

local government official, PESH designed, created, and installed a<br />

USA National Park visitors’ center quality display in the local<br />

government building, with 16 excellent photographs as large prints<br />

informative text in Spanish, and a profile map with scale of the cave<br />

showing it to be as deep at four Empire State Buildings in New<br />

York City stacked on top of each other.<br />

Another focus of the 2015 expedition was underground<br />

photography. Six excellent cave photographers were part of the<br />

team: Karis Biernacka of Poland, Liz Rogers of Australia, Dave<br />

Bunnell, Steve Eginoire, Chris Higgins, and Matt Tomlinson of the<br />

24

25

26

USA. A coffee table book of the best Huautla cave photographs<br />

through the years is being planned for the future.<br />

PESH 2016 Expedition<br />

Planning and preparing for our next expedition is underway in early<br />

September 2015. The dates are set: basically the month of April with<br />

a week of preparation in the field prior to that. Preparation in the<br />

field includes three days of driving from Texas to southern Mexico,<br />

visiting local government officials and getting permits and<br />

permissions, renting houses in a small village near the entrance to<br />

the section of the cave system we will concentrate on, and setting<br />

the houses up, which means getting the kitchen operating, buying<br />

groceries, and preparing for twenty more people to arrive in a few<br />

days. Then it will be four weeks of high energy activity with<br />

unexpected and usually surprising news reports from underground<br />

explorations.<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

We have a long list of exploration and study objectives for the next<br />

expedition, but then there is the possibility of the unexpected<br />

happening. The unexpected happened on the first two PESH<br />

expeditions, and they both happened late in the expeditions. “The<br />

unexpected” is something almost unique to cave exploration in these<br />

modern times. Since satellite photos are not available because caves<br />

are beneath the earth’s surface, and no technology exists that can<br />

penetrate thick layers of rock in mountains to see where cave<br />

passage lie, you literally don’t know until you go, in other words,<br />

pure exploration is still possible on Earth. The unexpected in cave<br />

exploration is usually when a surprising discovery is made where<br />

the geology of the cave as it is understood did not hold true and<br />

there is an unusual variation in the geologic structure.<br />

Near the end of the 2014 expedition, on the last day of a seven day<br />

stay deep in the cave, explorers working from a remote camp, 400 m<br />

below the surface, broke out into a 20 meter diameter tunnel<br />

bearing due north. It’s probably been there for five million years,<br />

but no one had ever reached it before. As much as it pained the team<br />

27

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

of five that found it, after exploring ahead a few hundred meters and<br />

mapping it, they took a photo to show its grandness and turned<br />

around to head out. That continuing passage is the number one<br />

objective in 2016. A team of five is already making plans to remain<br />

deep underground for one month and explore that passage as far as<br />

they can.<br />

Two other main objectives are in the same cave and will require<br />

other teams to camp deep and far in the cave to explore them. One<br />

was discovered late in the 2015 expedition. Three cavers had gone<br />

deep into the cave to “winterize it”, meaning pull ropes up shafts as<br />

they exited the cave, and leave the ropes coiled there where flood<br />

waters in the coming rainy season would not wash them away or<br />

damage them.<br />

Their plan was to camp one night in the remote underground camp,<br />

using sleeping bags and stoves already staged there for use in 2015,<br />

and the next day climb out of the cave and pull the fixed ropes up as<br />

they did. The problem was that one of them got sick once they got<br />

to the camp. He was going to need a day to recuperate, so the other<br />

two decided to do some exploring and mapping. They looked at the<br />

survey notes from the year before and picked a minor “lead”, a side<br />

passage noted but not yet explored, and decided it was close enough<br />

to the camp where the sick caver would be left, and they would give<br />

it a few hours and probably finish it.<br />

That’s not what happened. As soon as these two got on their hands<br />

and knees in soft sand in the low passage, they felt a strong breeze<br />

and smiled at each other. Cavers know, “if it blows, it goes.”<br />

Barometric exchanges with the changing air pressure on the surface<br />

cause breezes, sometimes even strong winds in caves, and cavers get<br />

good at detecting these clues and following them.<br />

And follow the wind these two did, to a new section with the most<br />

beautifully decorated passages found in all of the caves in Huautla.<br />

These two explorers, Gilly Elor and Derek Bristol, marveled at the<br />

wonderment of perhaps one of the most beautiful places on earth,<br />

28

or rather inside earth. Derek has done a fair amount of exploring in<br />

Lechuguilla Cave, New Mexico, said by many to be the most<br />

beautiful cave known. He thinks the section of Sistema Huautla<br />

they found that day in late April 2015, is as good. So, in thinking<br />

hard for a name for it, he coined the name Mexiguilla, combining<br />

the words Mexico and Lechuguilla. Mexiguilla will be explored,<br />

mapped, and photographed in 2016.<br />

Another top objective for 2016 is in this same section of Sistema<br />

Huautla. It’s over 700 m deep. Seen only once in 1977, there is a<br />

gigantic dome with a waterfall named Doo Dah Dome. It’s as wide<br />

and soaring as the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica, but much taller. The<br />

passage followed to get to it is named the Wind Tunnel, there is so<br />

much wind blowing through it. Doo Dah Dome is of unknown<br />

height. The lights of today are so much better than they were in<br />

1977, so perhaps in 2016 explorers will be able to see the top of the<br />

dome. But then again, maybe not. The plan is to climb it, using<br />

direct aid, and explore up-trending passages toward the surface,<br />

possibly as much as 1,000 m (3,300 feet) above.<br />

Gear and techniques<br />

A lot has changed gear-wise in the 50 years the caves of Huautla<br />

have been explored. In 1965 the first cavers wore denim pants and<br />

jackets and work boots. Their helmets were construction hard hats<br />

and their headlamps were carbide lights. Every three to five hours<br />

they had to refuel their carbide lamps. If they got wet, and the<br />

Huautla caves are wet even in the driest time of the year, their<br />

cotton pants and jackets sapped their body heat.<br />

Cavers not shun cotton completely. Synthetic materials make<br />

underwear warm even when wet. For outerwear nylon or PVC<br />

coveralls are worn. These are very durable and protect the caver<br />

from the often sharp walls. For boots most cavers wear lugged<br />

rubber canyoneering boots. Wet caves soften leather and leather<br />

boots die off quickly.<br />

29

A couple of years ago I wrote an article and got it published in a<br />

cavers’ journal titled “The Light is the Future is Here Now”. In it I<br />

recalled being miles from the entrance, deep in a cave, as a teenager,<br />

taking a break, waiting for someone to refuel his carbide lamp<br />

before it was my turn, and discussing how someday, someday way<br />

off the distant future, we will have very rugged headlamps with<br />

different settings to switch from 180 degrees of full periphery light<br />

to a beam that could reach the bottom of a deep, perhaps 500 foot<br />

deep shaft, to see if the rope we had just rigged reaches the bottom.<br />

It will be totally waterproof with batteries that last so long you can<br />

go on a long, maybe even 20 hour, non-stop caving trip and not<br />

have to change batteries. We laughed and someone said, “Like I’ll<br />

live long enough to see that!” I hope that he has. I have.<br />

I have a top of the line Scurion headlamp. Its Swiss engineered and<br />

made, very futuristic-looking, and does all of those things. Your<br />

headlamp is your primary piece of gear in caving. If you are out of<br />

light, you are stuck or you are borrowing a light. My Scurion is just<br />

one of four lights I always have with me in a cave. More often than<br />

not I have loaned a light to someone before I needed a backup light.<br />

The Scurion has never failed me.<br />

The ropes the first Huautla cavers had in the 60s were of a laid<br />

construction, meaning three strands twisted very tightly together, a<br />

rope named Goldline, which was known and dreaded for spinning<br />

anytime a caver could not stop the spinning by reaching out to the<br />

wall. If the rope hung in free space, a caver would spin round and<br />

round. Sometimes they got motion sick from the spinning.<br />

Packs were army surplus made of canvas. Canteens were also army<br />

surplus, or sometimes left over from when the caver was a Boy<br />

Scout.<br />

All the early Huautla cavers were male. That was in the 60s. In the<br />

70s it changed and about a fourth were female. Now it sometimes<br />

approaches 50%. This is a very welcome development.<br />

30

31

32

The ropes also changed in the 70s from the laid, twisted<br />

construction of Goldline rope, to the kernmantle, braided design of<br />

modern caving ropes, which don’t spin in free fall and don’t stretch.<br />

They are also very tough and abrasion resistant.<br />

Over the past twenty years the European technique of rigging<br />

rebelays, deviations, and using smaller, 9mm ropes has been adopted<br />

in Mexico and in much of the USA. Rebelays are when a rope is<br />

anchored on the wall of a shaft so that the rope does not make<br />

contact with a sharp place on the wall. A deviation is when a sling or<br />

a runner is used so the rope passes through a carabiner and is held<br />

away from the wall or sharp edge.<br />

Rappelling devices are exclusively either a rappel rack, or a bobbintype<br />

rappelling device, usually a Petzl Stop or Simple. The latter<br />

type is quicker when passing a rebelay and it has to be taken off the<br />

rappel rope in mid-shaft.<br />

Rope ascent is done by a technique called frogging. It’s a sit/stand<br />

technique, where a Petzl Croll ascending device is attached to a low<br />

slung seat harness and lifted by a chest harness when a climbing<br />

caver stands. Once seated they kick their heels back under their<br />

fanny, slide up an upper mechanical ascender which has a loop for<br />

their feet, and then stand up and do it again, moving like an<br />

inchworm. Once learned, it’s quite efficient, and since you are<br />

standing with both legs at once, it’s possible to haul a fairly heavy<br />

load as you climb a rope.<br />

Full speleology<br />

Speleology is the study of caves. Full speleology means conducting<br />

studies in all of the sub-disciplines of speleology: geology,<br />

hydrology, biology, paleontology, and archaeology. Huautla cavers<br />

even had a psychological study done on them in the mid-90s by a<br />

NASA researcher. After all, they were going to be in a remote place<br />

with a small team, no outside stimulus or distractions, doing<br />

difficult tasks in a risky environment and dependent on technology.<br />

33

In 2005 (and updated in 2012) the “Encyclopedia of Caves” was<br />

published in the USA by Elsevier Press. Editors William White and<br />

David Culver invited Jim Smith and me to co-author a chapter for it<br />

about Sistema Huautla. We decided to convey in our chapter not<br />

only a brief history of the exploration, mapping through the years<br />

and generally how it sizes up with the caves of the world, but we<br />

also listed the various disciplines of speleology and cited theses<br />

written and published, papers in journals, and books written about<br />

the exploration including “Beyond the Deep” by William C. Stone,<br />

Barbara AmEnde, and Monte Paulsen, and “Huautla: Thirty Years<br />

in One of the World’s Deepest Caves” by me.<br />

<strong>Adventure</strong><br />

There is no denying that the exploration of Sistema Huautla has<br />

been a grand adventure. Sit around a campfire with Huautla cavers<br />

and the stories pour forth. Two books have been written, countless<br />

articles in journals, and there is more to come. There are videos on<br />

You Tube and a movie was even made in the 90's that is on Vimeo<br />

(Huautla: The Mexican Cave). Portions of it have made to US<br />

television on NOVA, National Geographic Explorer, and How’d<br />

They do That? The Brits’ 2013 expedition shot video which is also<br />

on the web.<br />

I’m 66 years old. I was “bitten by the bug” to explore caves when I<br />

was 13. I’ve been in over 2,500 caves in the USA, Mexico, Belize,<br />

Guatemala, and China, but my masterpiece is Sistema Huautla. I’ve<br />

been on twenty expeditions there and my 21st is coming up in a few<br />

months. I think of myself as fortunate, fortunate to be among a<br />

group of world-class explorers who have hammered away,<br />

regardless of the difficulties and danger, to be the original explorers<br />

of what many feel is the greatest cave on Earth.<br />

34

Out there<br />

and back<br />

Kate Leeming<br />

8<br />

35

36

A myriad of thoughts flitted through my mind as I devoured Ken’s<br />

generous breakfast at the Club Hotel in Wiluna. I packed the<br />

calories in as if it was my last supper. Before leaving, I took the<br />

opportunity to make a few final calls as this was my last chance for a<br />

few weeks to speak on a land line. I called Arnaud and also my<br />

mother, to wish her happy birthday. I would be able to use the<br />

satellite phone to ‘check in’, but as it was incredibly expensive, I<br />

planned to make only short calls once a week unless there was an<br />

emergency.<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

Departing from the ‘Welcome to Paradise’ sign, I headed north,<br />

keen not to lose too much time. The day was already warming up,<br />

as were my legs which had benefitted from two days off, although<br />

they had not fully recovered. The dreaded muscle spasms returned,<br />

and I had no choice but to cycle through the pain.<br />

The first 38 km was a properly maintained gravel road servicing the<br />

Kutkabubba Community and Cunyu Station. To reach Well 1 I had<br />

to turn off the main track 4 km from Wiluna and venture 3 km west<br />

along a Gunbarrel Highway- like corrugated track, where it was<br />

impossible to avoid the corrugations on the firm surface. Kerrie and<br />

her grand-daughter followed, rattling along in their ute (a pickup<br />

truck), as did Don in his laden 4WD.<br />

Starting at Well 1 seems obvious, but most drivers, including Don,<br />

usually leave it out, preferring to head straight for the turn-off from<br />

the station road near Well 2 to the rough 4WD track. This they<br />

consider the Canning Stock Route ‘proper’. I felt that Well 1 was an<br />

important landmark and the most appropriate place for an official<br />

start. The last of an estimated thirty-one mobs of cattle were driven<br />

down the Stock Route in 1959. Since then, the condition of the<br />

watering points has deteriorated and about three-quarters of the<br />

wells, including Well 1, are now derelict and unfit for use by stock<br />

let alone humans. Only a handful of wells have been restored to<br />

supply drinkable water.<br />

The limited reliable water and food supplies were the main reasons I<br />

37

needed to travel with a support vehicle. With up to 400 km between<br />

supplies of good water, it was impossible to carry a week’s needs<br />

through the heat, especially over deep sand. We could carry 120<br />

litres or six days’ worth in the vehicle and planned to replenish<br />

supplies at Wells 15, 26, 33, 46 and 49. The next time we could buy<br />

food would be at the Kunawarritji Community, 1000 km from<br />

Wiluna.<br />

Well 1, sunk to a depth of 45 feet (13.5 metres) according to Snell’s<br />

journal, was built to supply good water for stock as they were kept<br />

there for extended periods of time before heading off to market, or<br />

new pastures if they were more fortunate. I wandered around the<br />

well and the water tanks, situated by Cockarra<br />

Creek, which were now in disrepair. The stagnant water which halffilled<br />

the wooden shaft appeared more like a murky black soup. The<br />

head of the windmill and the decapitated base of the Southern Cross<br />

frame lay rusting on the ground nearby, and the two galvanised iron<br />

water tanks sat empty and decaying on their concrete bases.<br />

Back on the well-graded road, my bike felt a bit like a racehorse. I<br />

positively flew over the dirt at more than 20 km an hour. Minus all<br />

the bags, I slammed into all the road imperfections harder than<br />

before and my wheels were tossed around at the even slightest<br />

bump or stone. Perhaps my bike was more like a bucking bronco -<br />

and this was the good road! Apart from a few essential items,<br />

everything else was in the vehicle. It almost felt like I was cheating.<br />

In the single rear pannier I carried my camera, basic tool kit, spare<br />

tubes, pump, snack food, extra water bottles, map and a two-way<br />

radio. The plan was that we would meet up for breaks and<br />

obviously to camp, but most of the time I would be alone, out of<br />

sight. The two-way radio was an important piece of equipment as<br />

long as we were within range. For the radio to work we had to be<br />

within 12 km as the crow flies. It was vital that we tested all our<br />

equipment and practised communicating on the first day so we<br />

could work as a team when things became more demanding.<br />

38

I had to get used to cycling on my own. In general, I quite liked the<br />

feeling of being free to move at my own pace. Although Greg and I<br />

were relatively equal in ability, we both had had to compromise.<br />

Where strength was a major factor - up steep inclines or pushing the<br />

heavy bikes through deep sand on the Gunbarrel - Greg was<br />

generally stronger. I was usually better at sustaining a steady pace,<br />

especially over the longer days. Now it was totally up to me. I had<br />

to listen to my body and adapt my work rate accordingly. At this<br />

point it was all positive. I wondered if this would change later on<br />

when the notoriously soft sand ridges kicked in and I would have to<br />

rely on self-motivational techniques to keep moving forward.<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

It didn’t seem to take long to carve a path through the scrubland to<br />

the turn- off to the track. We paused for lunch under the valued<br />

shade of the mulga bushes, the wattle Acacia aneura which had<br />

provided protection through most of the semi-arid country Greg<br />

and I had already travelled. The mulga leaves were a valuable source<br />

of protein for stock while the timber was used by Canning and Snell<br />

to build some of the wells. I passed pockets of everlasting flowers<br />

which formed carpets of brilliant yellow with splashes of pink and<br />

white.<br />

The track was sign-posted as the Canning Stock Route Heritage<br />

Trail. Next to this was a warning stating that the track is<br />

recommended for 4WD vehicles only, that there is no water, fuel or<br />

services between Wiluna and Halls Creek, a distance of over 1900<br />

km in length, and that motorists are advised to obtain adequate<br />

supplies and spares before venturing on this road. No mention of<br />

bicycles.<br />

Travelling with a support vehicle proved an utter luxury compared<br />

with having to carry everything on the bike. Previously Greg and I<br />

had to make do with sitting on a piece of shadecloth or a log for<br />

lunch, whereas Don pulled out two folding chairs. In catering for<br />

the journey, Don’s plan was to carry as much fresh food as would<br />

keep. He decided to bring a freezer rather than a refrigerator. The<br />

vehicle could only power one appliance and we could carry more<br />

39

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

major food items in a freezer over the four weeks, especially meat,<br />

which would be important for recovery and maintaining strength<br />

over the time. I enjoyed the deluxe avocado, tomato and cheese<br />

sandwiches followed by yoghurt, appreciating the fact that our<br />

sustenance would soon cease to be so varied and fancy.<br />

The Canning Stock Route is not an official gazetted road, and<br />

therefore most of it has never seen a grader. Canning’s original<br />

survey tabled a tract of land about eight kilometres wide. The broad<br />

band which connected the fifty-two watering points was wide<br />

enough to allow stock to graze on the limited vegetation.<br />

While a few vehicles had made it as far as Well 11 as early as 1929,<br />

the entire CSR was not conquered by vehicle until as late as 1968.<br />

Surveyors Russ Wenholz, Dave Chudleigh and Noel Kealley had to<br />

arrange for three fuel dumps along the way to supply their heavily<br />

laden Land Rovers. They averaged 75 km a day at 6.5 km per hour,<br />

covering 2600 km in thirty-four days. It was five years before<br />

another vehicle traversed the entire route. In 1980, a visitors’ book<br />

was placed at Well 26 and over one hundred people signed it the<br />

following year.<br />

Since then, numbers have steadily increased to at least one thousand<br />

annually - there may be many more, as some travelers do not<br />

register their intentions at Wiluna or Halls Creek as they should.<br />

The tyres of their 4WDs have formed the track, as drivers have<br />

searched for the best path through the different types of terrain. At<br />

this point, just before Well 2, the track simplified to merely two<br />

wheel ruts. Occasionally it diversified into extra options where<br />

vehicles had searched for alternative routes to avoid becoming<br />

bogged after rain, which turns the ground to the consistency of<br />

putty. The first eight kilometres wound through the bush on<br />

gravelly conglomerate and clay. I made good progress and at that<br />

stage was planning to reach Well 3 by the end of Day 1.<br />

Well 2 was in ruins and overshadowed by the newer windmill and<br />

water tank. We took a few minutes to check it out. Graffiti on the<br />

40

tank announced that “Jesus is coming - so look busy!” Beyond the<br />

well and without warning, the protected scrubland petered out into<br />

a plain of endless sand supporting only sparse vegetation cover. This<br />

was bad news for me as the track quality disintegrated with it into<br />

loose sand and corrugations. Any minor straight stretch of about 20<br />

metres or more would present me with a washboard surface. This<br />

was smooth on the bends, but speeding vehicles had sprayed sand<br />

outwards as they accelerated away from the turns and caused ruts<br />

with soft banks 30-40 cm deep. Had I been carrying a full load as<br />

before, I would have had to walk sections of the track as the wheels<br />

would have sunk too far.<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

Don appeared quite exasperated when we stopped for a breather.<br />

He had never known this section of the track to be so rough and cut<br />

up. I hadn’t imagined that I would have to struggle so much at this<br />

early stage. There had obviously been an unsustainable number of<br />

vehicles over the track during the season, many of the drivers<br />

unaware of the damage they caused by travelling too fast. As the<br />

track is not maintained in any way, this is not only dangerous, as<br />

they may not have time to react to unforeseen obstacles or bulldust,<br />

but it is also the cause of the horrific corrugations which are no<br />

good for drivers or cyclists.<br />

Don was worried that the track condition would damage his shock<br />

absorbers before he reached Halls Creek. The only shock absorbers<br />

I possessed were the fat tyres I had chosen to combat sand and<br />

corrugations, and either my knees or backside. Shock absorbers<br />

would have significantly smoothed my ride on unsealed tracks (they<br />

are a hindrance on tarmac). They certainly would have been part of<br />

my equipment had I been solely cycling the Canning Stock Route.<br />

Here it was only Day 1, and already I was longing for anything that<br />

would make my task more comfortable.<br />

Travelling was slower than expected and, due to my late start, I<br />

realised by mid-afternoon that reaching Well 3 that day was an<br />

unrealistic goal. I adjusted the target to Tank 2A. In the late<br />

41

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

afternoon, just before my destination, I spotted a wild cat<br />

wandering along the track. Feral cats are responsible for killing<br />

more native animals than any other vermin, causing great damage to<br />

many of Australia’s endemic species. Being down-wind of the black<br />

feline, I was able to creep up to within about 10 metres before the<br />

animal, which is a larger version of a domestic cat, sensed my<br />

presence and darted off through the spinifex and bushes. In earlier<br />

days, pastoralists were unable to keep dogs because large numbers<br />

of poison baits had been laid to control the fox and dingo<br />

populations.<br />

Many chose to keep cats instead, the descendants of which roam<br />

wild in alarming numbers. Don drove on ahead to start setting up<br />

camp at Tank 2A. The Granites was the last watering point to be<br />

constructed by Canning in 1910. The storage tank was blasted out<br />

of solid granite rock and at one time had a capacity of 40 000 litres.<br />

Transporting the dynamite had been a task to be handled with kid<br />

gloves. Reaching the final well with the volatile explosive intact was<br />

testimony to good management and a little luck. The quietest camel<br />

drew the short straw (which, if the plan went wrong, could have<br />

been the straw that broke the proverbial camel’s back), and carried<br />

the dynamite at the tail end of the train. At each camp the explosive<br />

was placed in a hole in the ground and covered with branches to<br />

keep it cool.<br />

After they had finished Tank 2A, the construction team wearily<br />

returned to Wiluna after two seasons on the job. The Canning Stock<br />

Route was ready for use, completed at a cost of 22,000 pounds.<br />

Today, a crumbling stone fence partially protects the water source<br />

which is now half-caved in. Mosquitoes revelled over the stagnant<br />

pool as the sun melted into the horizon. We camped a good distance<br />

away from the water-hole so animals could get to the tank to drink<br />

overnight.<br />

Compared with the lightweight model I had been carrying up until<br />

then, the heavy-duty canvas tent I was to use for the duration of the<br />

42

43

44

CSR was palatial. Don showed me how to erect it, the single<br />

extendable pole pushing up the centre so I could actually stand up<br />

in it. I would have had room to swing that wild cat! The selfinflating<br />

mattress was also far more luxurious than I was used to.<br />

Don insisted that very soon I would need all the comfort I could<br />

get. All these little luxuries, which most would not appreciate as<br />

much as I did in these circumstances, were to help maintain morale<br />

further down the track. Dinner was steak, potatoes and fresh salad<br />

with mini-pavlovas, cream, strawberries and kiwi fruit for sweets. It<br />

was not going to last, but it was a civilised celebration of our first<br />

night on the Canning Stock Route.<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

Day 2, Friday 24 September<br />

The Granites to Well4A<br />

Distance - 100 km<br />

Daily temperatures were now consistently in the mid-to-high 30s,<br />

averaging about 37°C (100°Fahrenheit on the old scale). I dragged<br />

myself away from the comfortable mattress at S.4Sam and pedalled<br />

off about an hour and a half later.<br />

I had planned to get away earlier, but being the first morning on the<br />

road, we hadn’t developed a routine. I never like to be hurried first<br />

thing in the morning. It always takes time to prepare for the day.<br />

The plan was to get breakfast organised, pack my personal<br />

belongings, eat and go, leaving Don to pack up camp, load and<br />

prepare his vehicle. He could afford to take his time whereas I had a<br />

sense of urgency to make best use of the daylight, especially in the<br />

relative cool. Don had remembered the section of track to Well 3 as<br />

being good quality; this report, together with the solid surface for<br />

the first four kilo metres through the scrub, buoyed my<br />

expectations for what was to come. As I moved away from the<br />

protection of the trees, it was therefore disheartening to find the soft<br />

plains return and with them a track quality similar to the section<br />

between Wells 2 and 2A.<br />

As on the Gunbarrel, occasional ancient sand ridges which had<br />

45

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA<br />

compacted over thousands of years rose above the plain, providing a<br />

brief respite. Of the 31 km to Well 3, approximately 21 km were<br />

bad. My average speed had dropped from about 22 km per hour on<br />

the maintained gravel road to 13.9 km per hour. While this gives an<br />

indication of the relative decrease in track standard, it doesn’t,<br />

however, give an idea of the amount of extra energy used to<br />

maintain balance and push through the sand. Tank 2A to Well 3<br />

took two hours and fifteen minutes.<br />

The benefit of travelling so slowly was that I could identify various<br />

animal tracks, which became more frequent as I approached Well 3<br />

and the more productive land around the dry creek bed. Within a<br />

few kilometres I identified emu, cat, goanna, snake, small lizard and<br />

various bird tracks. The colourful display of flowers was similarly<br />

diverse. Large red kangaroos darted in front of me as I approached<br />

the turn-off to the well. A flock of white cockatoos, twenty- eight<br />

parrots and pink and grey galahs squawked noisily from their<br />

perches in the towering river red gums, announcing my presence.<br />

Well 3 sits beside the banks of Sweeney Creek, named after James<br />

Sweeney, farrier on John Forrest’s 1874 expedition from Perth to<br />

Adelaide via a northerly route. Water was drawn from a depth of 23<br />

feet (about 7 metres) but the well only yielded about 4000 gallons<br />

(18,000 litres) per day. In 1929, the water quality was classed as<br />

excellent.<br />

The well was restored by the Foothills 4WD Club of Western<br />

Australia, which in 1998 had made two trips to complete its<br />

refurbishment. The members had done a good job, fixing a pair of<br />

trapdoors over the top and building a protective fence around the<br />

shaft. But even after restoration, the quality of the stagnant water<br />

was questionable and certainly smelt unfit to drink. When I opened<br />