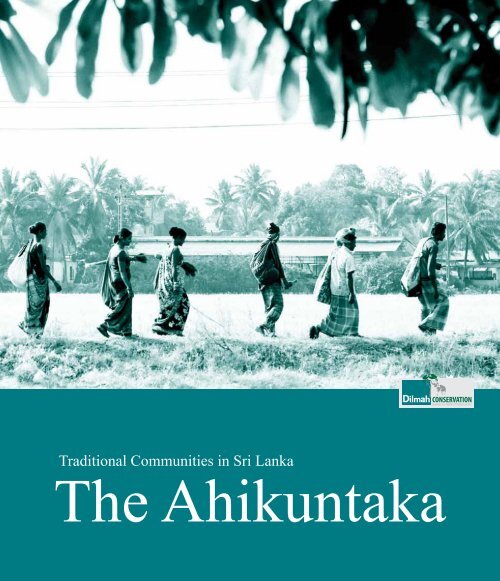

The Ahikuntaka

A publication documenting the lives and livelihoods of the Ahikuntaka or gypsy community in Sri Lanka. A collection of vibrant photographs and a baseline survey on the current socio economic status of the Ahikuntaka conducted by the Colombo University complement this timely publication.

A publication documenting the lives and livelihoods of the Ahikuntaka or gypsy community in Sri Lanka. A collection of vibrant photographs and a baseline survey on the current socio economic status of the Ahikuntaka conducted by the Colombo University complement this timely publication.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

Traditional Communities in Sri Lanka<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

Dilmah Conservation <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> 1

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

Dilmah Conservation

Dilmah Conservation<br />

DS

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

Declaration of Our Core<br />

Commitment to Sustainability<br />

Dilmah owes its success to the quality of Ceylon Tea. Our business was founded therefore on an enduring<br />

connection to the land and the communities in which we operate. We have pioneered a comprehensive commitment<br />

to minimising our impact on the planet, fostering respect for the environment and ensuring its protection by<br />

encouraging a harmonious coexistence of man and nature. We believe that conservation is ultimately about people<br />

and the future of the human race, that efforts in conservation have associated human well-being and poverty<br />

reduction outcomes. <strong>The</strong>se core values allow us to meet and exceed our customers’ expectations of sustainability.<br />

Our Commitment<br />

We reinforce our commitment to the principle of making business a matter of human service and to the core values<br />

of Dilmah, which are embodied in the Six Pillars of Dilmah.<br />

We will strive to conduct our activities in accordance with the highest standards of corporate best practice and in<br />

compliance with all applicable local and international regulatory requirements and conventions.<br />

We recognise that conservation of the environment is an extension of our founding commitment to human service.<br />

We will assess and monitor the quality and environmental impact of its operations, services and products whilst<br />

striving to include its supply chain partners and customers, where relevant and to the extent possible.<br />

We are committed to transparency and open communication about our environmental and social practices.<br />

We promote the same transparency and open communication from our partners and customers.<br />

We strive to be an employer of choice by providing a safe, secure and non-discriminatory working environment for its<br />

employees whose rights are fully safeguarded and who can have equal opportunity to realise their full potential.<br />

We promote good relationships with all communities of which we are a part and we commit to enhance their quality<br />

of life and opportunities whilst respecting their culture, way of life and heritage.

© Ceylon Tea Services PLC<br />

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

This publication may be produced in whole or in part and in any form for<br />

educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the<br />

copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is cited. No<br />

use of this publication may be made for resale or any commercial purpose<br />

whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the copyright holder.<br />

Disclaimer<br />

<strong>The</strong> contents and views in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or<br />

policies of the copyright holder or other companies affiliated to the copyright holder.<br />

Works cited<br />

Gankanda, N. & Abayakoon, A. (2013). Traditional Communities in Sri Lanka -<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong>. Colombo, Sri Lanka: Ceylon Tea Services PLC.<br />

Printed and bound in Singapore<br />

ISBN: 978-955-0081-08-0<br />

Ceylon Tea Services PLC<br />

MJF Group<br />

111, Negombo Road<br />

Peliyagoda<br />

Sri Lanka<br />

Contact<br />

info@dilmahconservation.org<br />

May 2013.<br />

<strong>The</strong> images for this publication were sourced from Darrell Bartholomeusz (DB), Alan Benson (AB), Dhanush De Costa (DD), Dimithri Cruze (DC), Dharshana Jayawardena (DJ), Bree Hutchins (BH), Namal Kamalgoda<br />

(NK), Sarath Perera (SP), Malaka Premasiri (MP), M. A. Pushpakumara (PK), Devaka Seneviratne (DS), Julian Stevenson (JS), Dilhan C. Fernando (DCF), Nuwan Gankanda (NG), Asanka Abayakoon (AA), Dilmah<br />

Graphics (DG)

Traditional Communities in Sri Lanka<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong>

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

An introduction<br />

<strong>The</strong> memory of the <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> walking through my village<br />

is as fresh today as it was sixty years ago. Many a time have<br />

I wondered what has befallen those mystifying and colourful<br />

people, as I realised that over time, their presence in many parts<br />

of the country has dwindled.<br />

With the growth of Dilmah, I was determined to do something<br />

for the people of this country. <strong>The</strong> MJF Foundation and Dilmah<br />

Conservation were founded with the vision of sharing our<br />

bounty with those in need of care and protection. In memory<br />

of those colourful visions of my childhood, I wanted to extend<br />

that care and protection to the fast vanishing <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

(Nomadic) community. With this in mind, a project to preserve<br />

and protect their cultural identity was planned and launched<br />

through Dilmah Conservation.<br />

<strong>The</strong> culture of any given country is made up of the sub cultures<br />

that exist within that country. If, at any given time, the sub<br />

cultures that exist within a country are found to be collapsing,<br />

the ripple effect it would have on the ‘larger’ culture of the<br />

country will be a negative one. <strong>The</strong>refore, the preservation of<br />

sub cultures is of utmost importance to any civilisation. <strong>The</strong><br />

Lankan civilisation is no exception to this phenomenon. <strong>The</strong><br />

culture and the identity of a Lankan is the harnessing of all sub<br />

cultures that exists within the Lankan community.<br />

<strong>The</strong> coming together of the Sinhalese, Tamil, Muslim and<br />

Burgher communties that are grounded by religious traditions<br />

of Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam and Christianity have all<br />

contributed to the larger cultural identity of a Sri Lankan.<br />

In the midst of such rich diversity, the Nomadic community,<br />

though not large in their numbers, take pride of place, adding<br />

colour and value to the Lankan family. I believe that the colour<br />

and value that this Nomadic community adds to the cultural<br />

diversity of Sri Lanka has not been appreciated enough. Through<br />

ignorance and non-appreciation of their different lifestyles, a<br />

great historical injustice has befallen this community. We forget<br />

that the gypsy who is seen roaming the streets with a monkey<br />

and a snake is a sight that is captured by almost every tourist<br />

who visits our island nation. Thus, the gypsy becomes a cultural<br />

ambassador of this country.<br />

Just as much as biodiversity plays the most pivotal part in the<br />

workings of Mother Nature, cultural diversity is considered an<br />

essential guiding factor in the process of human civilisation and<br />

evolution. Indigenous people enrich and enhance the cultural<br />

diversity of the society we live in. I believe it is our duty to help<br />

them live their lives with honour and integrity.<br />

I believe living with dignity is our birthright; and not a<br />

privilege bestowed to us by a societal hierarchy. My wish is for<br />

the dawn of that day when men of all shape, caste and creed<br />

accept this as a basic human truth. I am happy that Dilmah is<br />

able to contribute towards preserving the cultural diversity of<br />

Sri Lanka and thereby help the country take a few steps towards<br />

embracing the beauty that this diversity brings.<br />

Merrill J. Fernando<br />

Founder – Dilmah Conservation<br />

8 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

Dilmah Conservation

Dilmah Conservation <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> 9<br />

AB

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

Foreword<br />

Among the many clans and communities that reside in this<br />

beautiful nation, the Nomadic or gypsy communities have with<br />

them practices that are unique to their community. <strong>The</strong> gypsies<br />

live a lifestyle of a tourist moving from one place to another<br />

together with their props and this itself provides an extreme<br />

example of the unique traditions and practices the gypsies, as<br />

a community, possess. Despite this unique contribution it is<br />

sad to note that there is little or no research conducted on this<br />

community. <strong>The</strong> main criticism against the handful of research<br />

studies that have been conducted on this community is the<br />

fact that it lacks depth both on an angle of human interest and<br />

social science. <strong>The</strong> studies that have been conducted to this day<br />

on this community has either been confined to research done<br />

on a academic platform at a university or a study conducted<br />

by individuals who are enthralled by the nomadic lifestyle.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se studies though small in number, I believe, have been the<br />

guiding lights for further study on the inner workings of this<br />

community.<br />

<strong>The</strong> research work of the renowned Indian human scientist<br />

M.D. Raghavan on the early cultural beginnings of the<br />

nomadic community and the tourist lifestyle of the members<br />

of this community takes pride of place in the handful of<br />

research that has been conducted on the gypsies. <strong>The</strong> work<br />

of Sunil Kularathne (1982) Chandra Shree Ranasinghe, Sepala<br />

Amarasinghe and Nadeera Jayathunga (2009) have all been<br />

illuminating in this regard. <strong>The</strong> constant articles and stories that<br />

have been published both, in news papers and magazines have<br />

also been contributory factors for the further study of the gypsy<br />

community.<br />

However all of the above research work lacks clarity simply due<br />

to the reason that they were not carried out to encompass the<br />

entire system of the Nomadic lifestyle and culture. <strong>The</strong>refore,<br />

the subtleties and differences that exist within the community<br />

have failed to be highlighted. Studies are yet to be conducted<br />

on the historical evolution of the community from the ‘clan’<br />

mentality to what it is today and this I believe is an area that<br />

needs indepth study discussion. <strong>The</strong> Christianisation of the<br />

community spearheaded by the visiting missionaries has directly<br />

resulted in the erosion of traditional beliefs, rituals and practices.<br />

<strong>The</strong> younger generation of the community has lost interest in<br />

continuing with their forefathers beliefs thus endangering the<br />

unique attributes that were a part and parcel of the nomadic<br />

lifestyle.<br />

<strong>The</strong> knowledge of the traditional workings of the community<br />

today is confined to a few members of the older generation,<br />

which if not preserved, would be lost to the world. <strong>The</strong>refore<br />

the very fact that Dilmah Conservation have taken the initiative<br />

to preserve the knowledge on the cultural significance and value<br />

that the gypises possess should be commended. I believe that<br />

Dilmah Conservation has taken this initiative at the most crucial<br />

juncture believing it to be the last chance for any comprehensive<br />

work on the community. <strong>The</strong> task that Dilmah has sought to<br />

complete I believe will be priceless in terms of the value it would<br />

add to the big mix of the Lankan family.<br />

<strong>The</strong> gypsies are a community that prefers living away from<br />

traditional society. <strong>The</strong>ir lineage is traced back to India and<br />

parts of this large gypsy family are scattered in different parts of<br />

the globe. <strong>The</strong> traditional homeland of all these communities is<br />

believed to be India. I believe that the Sri Lankan gypisies should<br />

be considered a part of this larger gypsy community scattered in<br />

10 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

Dilmah Conservation

many parts of the world and must be connected with them.<br />

This will result in the much needed infusion into the culture<br />

and lifestyle of the Sri Lankan gypsy community.<br />

I take this opportunity to thank Dilmah Conservation for<br />

taking the initiative to support and document the lives of<br />

traditional communities in Sri Lanka. It is a timely and<br />

necessary intervention.<br />

Professor Ranjith Bandara<br />

Department of Economics<br />

University of Colombo<br />

SP<br />

Dilmah Conservation <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> 11

Contents<br />

Introduction to Nomadic Communities<br />

Snake charming exhibition methods<br />

exhibition meth<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> caste system in Sri Lanka<br />

Deities and gods of the <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> community<br />

<strong>The</strong> Court system<br />

Traditional methods of medication<br />

A vanishing community Maddili<br />

Mahakanadarawa a village by the tank<br />

Kali Amma the woman who strayed away from tradition<br />

<strong>The</strong> story of Rengasamige Masanna<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> Varigasabha<br />

Kudagama Charter<br />

Preserving their cultural identity<br />

A Baseline Survey of Sri Lankan Nomads<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

18<br />

20<br />

24<br />

28<br />

32<br />

38<br />

40<br />

42<br />

44<br />

48<br />

54<br />

56<br />

60<br />

64<br />

112

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

14 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong>

“W<br />

ith pride we mention that, even though we are a minority community,<br />

our contribution towards nourishing Sri Lankan cultural diversity is<br />

significant. Our cultural identity plays a major role in that context. For a slight<br />

elaboration of our cultural identity, we are pleased to make mention of the snake<br />

charming and monkey performing, fortune telling and gypsy lifestyle which<br />

distinguishes the <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> community from others.”<br />

This is an excerpt from the Kudagama Charter which was ratified on the banks of the Rajangana Tank, in Kudagama,<br />

Thambuttegama during the Dilmah Conservation sponsored <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> Varigasabha held on January 28 th 2011.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Charter was signed by five leaders the of community, Nadarajah of Kudagama, Egatannage Masanna of<br />

Andarabedda, Anawattu Masanna of Kalawewa, M. Rasakumar of Aligambe and Karupan Silva of Sirivallipuram who<br />

represented different clans within the <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> community.<br />

DS<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

15

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

DCF<br />

16 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

Dilmah Conservation

DCF<br />

DCF<br />

Dilmah Conservation<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

17

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

Introduction to Nomadic Communities<br />

Many South Asian countries have clans or tribes that<br />

specialise in ‘snake charming’. In Sri Lanka, they are<br />

known as ‘<strong>Ahikuntaka</strong>’ or ‘Kuthadi’ who engage in snake<br />

charming as a traditional method of livelihood. <strong>The</strong>se clans<br />

have within them the skill to charm a number of snakes<br />

including the most dangerous cobras and vipers; species they<br />

have charmed hereditarily. <strong>The</strong>se charmers make use of a ‘flute’<br />

like instrument which exudes music to which the snake swiftly<br />

responds. India is home to many snake charming clans while<br />

they are also found across Pakistan, Bangladesh, Thailand,<br />

Malaysia and Sri Lanka.<br />

<strong>The</strong> type of snakes that are charmed by these men differ<br />

from region to region; the Indians specialise in charming the<br />

Indian cobra, Russell’s viper, Indian and Burmese pythons and<br />

mangrove snakes. <strong>The</strong> African tribes that practice this art make<br />

use of the Egyptian cobra, Puff Adder, Carpet viper and the<br />

Desert Horned viper, all of whom are extremely venomous.<br />

<strong>The</strong> ‘Abrahmic’ religious traditions which include the three<br />

main religions of the world - Judaism, Christianity and Islam<br />

consider the ‘snake’ to be the embodiment of evil. <strong>The</strong>refore<br />

those who follow these religious traditions believe snake<br />

charmers to be extremely dangerous due to the belief that a<br />

snake charmer has the ability to even charm the devil or satan.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Indians have a very unique culture of snake charming.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y seldom consider a snake to be the embodiment of evil<br />

and many even go as far as giving the snake spiritual status.<br />

<strong>The</strong>refore, the charming of a snake is considered holy and done<br />

purely for entertainment. Like their relatives in Sri Lanka, many<br />

of the nomadic or gypsy tribes practices their trade by migrating<br />

from one city to another, stopping at requests and showcasing<br />

18 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

Introduction to Nomadic Communities

their exhibits. <strong>The</strong>se men, more often than not, are known to<br />

sell herbs that can be used as anti-venom and some of them are<br />

even skilled at treating snake bites.<br />

<strong>The</strong> most ancient and informative readings regarding snake<br />

charmers are found in ancient Egyptian texts. <strong>The</strong> snake<br />

charmers of that era were considered magicians and even<br />

doctors, and are ranked among the most influential in society.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y were known to be literate and had learnt the art of<br />

snake charming as a part of their education. <strong>The</strong> present day<br />

Indian tribes, who practice this art, are intertwined with the<br />

Hindu religious inclination towards the ‘snake’ or ‘nagaya’.<br />

According to this religious ideal, the ‘nagaya’ is considered a<br />

holy and sacred animal and during ancient times these snake<br />

charmers were considered ‘blessed beings’. Ancient Indian snake<br />

charmers were also known to have had the power of healing.<br />

<strong>The</strong>ir guru or guardian saint to this day is ‘Baba Gulabir’<br />

who is considered to be an avatar of the snake gods. He was<br />

instrumental in preaching love towards the snake and was<br />

very vocal about the need for snake conservation. Countless<br />

legends about his ‘miraculous powers’ have been woven<br />

around him and it was at the temple dedicated to him at<br />

Charkhi Dadri, that the snake charmers’ conference was held.<br />

‘Babaji was a reincarnation of Nag Devata,’ informed<br />

Mohinder Pal, a snake charmer from Bhiwandi. ‘He took the<br />

human form to stop people from killing snakes out of fear. He<br />

taught them to love snakes and keep them as their protectors.<br />

It is that legacy we have inherited and are carrying forward.’<br />

DG<br />

Introduction to Nomadic Communities<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

19

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

Snake charming<br />

exhibition methods<br />

Snake charmers use various types of small boxes, or<br />

pouches to carry their snakes. Customarily, the box in<br />

which the snake is kept is inserted into a pouch made of<br />

cloth and is carried on one arm. <strong>The</strong>y use an instrument<br />

which exudes the sound of a flute and move from place to<br />

place exhibiting their wares.<br />

Snake charmers take many precautions against an attack<br />

from the snake they carry. <strong>The</strong> most obvious being the<br />

removing of the venomous teeth. <strong>The</strong> African tradition is<br />

known as ‘sewing’ the mouth of the snake or serpent, which<br />

curtails the jaw movement of the reptile. This restricts the<br />

snakes ability to spit venom and its ability to capture prey.<br />

However, many animal rights activists are up in arms against<br />

this practice as it results in the snake not being able to have<br />

regular food, which could also result in the development of<br />

various infections in the mouth and subsequent death.<br />

20 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

Snake charming exhibition methods

BH<br />

Snake charming exhibition methods<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

21

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

DCF<br />

22 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong>

DCF<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

23

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> caste system in Sri Lanka<br />

<strong>The</strong> entire gypsy population of the country, despite<br />

being limited to around 1000 families have within<br />

them a unique caste hierarchical system. During previous<br />

generations, the caste system was considered important<br />

and had an enormous bearing on marriages, similar to<br />

that of rural Sri Lankan society. However, the present day<br />

gypsies seems to have broken the shackles that had them<br />

restricted even within themselves, with social and economic<br />

factors taking more central roles in their lives. Nevertheless,<br />

to date, the ‘high’ or ‘low’ caste differentiation exists within<br />

the community, when deciding on vital matters. <strong>The</strong> origins<br />

of this caste hierarchy can be traced back to their relatives in<br />

India who pay great emphasis to this factor.<br />

Speaking to us during the research, a member of the gypsy<br />

community Andarabedde Masanna Arachchila, explained<br />

that the caste system had two distinct differences, namely<br />

‘Dugudoru’ and ‘Thapaloru’ which translates as ‘high’ and<br />

‘low’. <strong>The</strong> Dugudorus have four sub clans and the Thapalorus<br />

have five sub clans into which the entire community is<br />

divided. <strong>The</strong>se sub clans are divided according to their<br />

hereditary professions, much like the rural Sinhala folk. <strong>The</strong><br />

higher castes have the more prestigious duties, as cultivation<br />

and decoration of marriage festivals and brides. <strong>The</strong> lower<br />

castes have relatively less prestigious duties including washing<br />

clothes or cutting the hair of community members. <strong>The</strong><br />

laundry and barber duties being considered low are common<br />

among the neighboring Sinhala folk as well.<br />

Upon inspection, the roots of these castes seems to have<br />

been divided based somewhat on their profession and their<br />

appearance. This however is a general view and cannot be<br />

used as an indication for all castes. One strain emanates from<br />

the hereditary profession of the members and the other, is<br />

the physical appearance of a set of members of a certain caste.<br />

Band playing and dancing at weddings is exclusively the duty<br />

of the ‘Burakaya Dugadoru’ tribe, while decorating weddings,<br />

jewellery making are the responsibility of the ‘Kunchammaru<br />

Dugadoru’ caste. Members of the Yaara Thapaloru caste<br />

are known as gypsies with ‘red skin’. However, whether this<br />

distinction is actually based on the colour of their skin or<br />

whether it is based on their profession – dealing in animal<br />

skins – is yet to be determined.<br />

Many older members of the gypsy community would swear<br />

by the fact that they were exclusively nomadic, moving from<br />

one village to another, with no permanent residence. Except<br />

for migrating from village to village, exhibiting their snakes,<br />

there is no evidence to suggest that the gypsies took refuge<br />

in a certain place and practiced another craft. According to<br />

many elders, the caste hierarchy was strongly prevalent until<br />

the early 1990’s and subsequent to the Christian missionary<br />

involvement which resulted in conversions; the impact of the<br />

caste system seems to have dwindled.<br />

24 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> caste system in Sri Lanka

JS<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> caste system in Sri Lanka<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

25

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

26 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong>

During previous generations, the caste<br />

system was considered important and had<br />

enormous bearing on marriages similar to<br />

that of rural Sri Lankan society<br />

BH<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

27

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

Deities and gods of the <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> community<br />

Angates Sami<br />

This is a male god worshipped mainly by the ‘Burakaya’ caste.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re are records of an annual offering made to this Sami<br />

for protection. <strong>The</strong> offering included a clay prototype of the<br />

god into which various ingredients, including rice and sugar,<br />

are mixed. After the offering is made, the members present<br />

during the pooja are said to have shared the offering amongst<br />

themselves.<br />

Kanamma Sami<br />

A female deity worshipped and revered by those of<br />

the ‘Burakaya’ caste. According to a community elder,<br />

Andarabadde Masanna Arachchila, this deity is looked upon<br />

for good health and wealth. <strong>The</strong> offering includes milk and a<br />

concoction of fruits which mainly includes plantains which<br />

the followers offer as pooja.<br />

Masamma<br />

According to Andarabadde Masanna Arachchila, ’Masamma’<br />

is the community’s version of the much revered and feared<br />

‘Kali Amma’, a deity who is looked upon with reverence and<br />

fear by the Sinhalese and Tamils even today. <strong>The</strong> offering<br />

includes a prototype of the god made out of clay onto which a<br />

concoction of rice and sugar is mixed. A red hen is also offered<br />

to the deity. <strong>The</strong> pooja ends with the red hens’ blood being<br />

poured over the prototype. According to community elders,<br />

the last pooja of this nature had taken place in 1953 at of<br />

Thalgaswewa.<br />

Sallapuramma<br />

This deity is worshipped for her healing powers. According<br />

to Andarabadde Masanna Arachchila, Sallapuramma is the<br />

<strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> version of ‘Paththini Amma’, a goddess much<br />

revered and respected by local Sinhalese and Tamils. <strong>The</strong> last<br />

pooja offered to this deity was held in Kudagama in 1990.<br />

Pullayar<br />

One of the main gods of the Hindu religious tradition, the<br />

<strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> community also worships this god. Despite<br />

being converted to Christianity, many community members<br />

still revere and worship this deity. During the dawn of the<br />

traditional New Year on January 1 st , <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> families boil<br />

milk as an offering to him. Once the offering is made, the<br />

community uses the milk to prepare ‘milk rice’ which is shared<br />

with all present. This is seen as a direct result of the Sinhalese<br />

and Tamil communities’ influence upon the gypsies.<br />

Madu Meniyo<br />

According to Andarabadde Masanna Arachchila, the<br />

forefathers of this community have also worshipped ‘Madu<br />

Meniyo’, a saint who is looked upon with great respect by all<br />

communities in the country. However, what can be seen is<br />

that the Madu Meniyo the gypsies worship is different to the<br />

saint that all Christians hold in high esteem. According to our<br />

source, the deity they worship is actually ‘Paththini Amma’<br />

who has a temple dedicated to her in the vicinity of the<br />

original Madu Temple in Mannar.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is also evidence to suggest that these folk paid homage<br />

to Lord Kataragama (Skanda) and a majority of gods revered<br />

in the Hindu tradition.<br />

28 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

Deities and gods of the <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> community

DS<br />

Deities and gods of the <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> community<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

29

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

30 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong>

DCF<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

31

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

<strong>The</strong> Court system<br />

During the years gone by, with the community solely living<br />

a nomadic lifestyle, moving from one place to another, the<br />

community developed a unique system to decide on disputes that<br />

arose amongst them. It can be safely assumed that the system<br />

was a result of a mixture of customs and traditions that existed<br />

within the community and the influence of the neighboring<br />

communities. Rules and regulations were imposed upon the<br />

community by the will of the majority and where a set of elders<br />

well versed in the laws, decided on disputes. This system is similar<br />

to the ‘Panchayath Sabha’ practiced in rural India. <strong>The</strong> head of the<br />

council is the head of the ‘Kuppayama’ (village) and in the event<br />

of a dispute, the aggrieved party complains to the ‘Arachchila’<br />

(head of the village) who in turn decides on a date for the hearing.<br />

<strong>The</strong> most important feature at this hearing, much to the surprise<br />

of many a civilised person, is the pride of place given to alcohol.<br />

<strong>The</strong> plaintiff, prior to the hearing has to entertain the respondents,<br />

the council and those present at the hearing with alcohol. Both the<br />

complainant and the respondent, in addition to providing alcohol,<br />

are obliged to pay the council a fee for the hearing and this fee in<br />

turn is also used to purchase some form of alcohol. Due to this,<br />

a hearing of a dispute is a much looked forward to event by the<br />

villagers.<br />

In the event one party does not agree with the decision arrived at<br />

by the council, there is the remedy of an appeal. For the appeal,<br />

the party disagreeing with the decision has to bear the cost of the<br />

alcohol. If a decision cannot be reached despite the appeal, then<br />

the hearing is shifted to another location.<br />

According to Thimmannage Engatana, if there is no agreeable<br />

decision at the appeal, the parties and those interested in the<br />

outcome, shift locations most often to a land close to a dam. <strong>The</strong><br />

same procedure regarding the distribution of alcohol is strictly<br />

adhered to even during the second appeal. In the event that no<br />

proper judgment is arrived at, the parties then move to another<br />

gypsy village and can complain to the ‘Koralama’ who is considered<br />

as a regional head of a few villages.<br />

Finding the culprit<br />

If in the case of a hearing, the wrongdoer does not agree with<br />

the decision, the community has devised their own method<br />

of ‘swearing’ which involves deities and other transcendental<br />

aspects the community believes in. <strong>The</strong> method of swearing their<br />

innocence is similar to those of the Sinhala swearing methods used<br />

during the times of the kings.<br />

If the council decides that there has to be a swearing, the<br />

community adopts a very customary approach to the ceremony.<br />

<strong>The</strong> swearing is always scheduled to the day after the disputed<br />

decision is given. During that time the accused is kept under<br />

house arrest and held under the watchful eyes of the members of<br />

the council. Prior to the swearing, the accused has to bathe and<br />

cleanse himself. One of the main methods of swearing adopted<br />

by the community is the ‘burning oil’ method. Accordingly, the<br />

accused has to move around a pot of burning oil thrice and then<br />

put his thumb into the pot. If his thumb burns that is taken as an<br />

assurance of his guilt. Another method is making the accused hold<br />

a heated iron bar. If there is no burn on the accused, he is absolved<br />

of the crime. <strong>The</strong> community believes that the gods that be, protect<br />

the innocent during these trials. <strong>The</strong>se trials by torture are not<br />

alien to the Ahikunatakas and have been used time and time again<br />

during Greek and Roman civilisations.<br />

If there are two suspects being accused of the same offence, there is<br />

a somewhat different method used to decide on the culprit. Both<br />

the accused are given similar amounts of rice, water and heat to<br />

boil a pot of rice. <strong>The</strong> first person to have boiled the pot of rice is<br />

considered innocent.<br />

32 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> Court system

Rules and regulations were imposed upon<br />

the community by the will of the majority<br />

and where a set of elders well versed in the<br />

laws, decided on disputes<br />

DS<br />

<strong>The</strong> Court system<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

33

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

DS<br />

34 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong>

DS<br />

DCF<br />

Dilmah Conservation<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

35

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

36 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong>

JS<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

37

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

Traditional methods of medication<br />

Both rural and urban Sri Lankans have strong belief that<br />

the gypsies have with them supernatural powers which<br />

include healing, taming of devils and casting of spells and<br />

charms. <strong>The</strong>refore, the community makes a considerable<br />

income practicing the above. Many of the present day gypsies<br />

possess herbal remedies and stones which are said to suck out<br />

poison. However, there is no scientific basis with regard to the<br />

results that these herbs and stones are said to bring about.<br />

<strong>The</strong> ‘Visha Gala’ or the stone to suck out poison can be<br />

seen as the communities “main product”. <strong>The</strong>re are many<br />

conflicting theories that have emerged with regard to the<br />

preparation of this stone. John Steele in his book Jungle Tide<br />

describes that the stone is made out of animal bone.<br />

However, Andarabedde Masanna Arachchila gave quite<br />

an elaborate description about the making of the stone.<br />

According to him, the stone includes rare herbs found in the<br />

forests and chemicals including mercury. <strong>The</strong> mixture is then<br />

bathed in human urine and lime. This concoction is then<br />

placed in the sun to harden and the resulting product is the<br />

Visha Gala.<br />

According to the gypsies, the stone is placed on the exact<br />

location of the snake bite, and it is said to suck in all the venom<br />

from the blood stream of the victim. Once all the poison has<br />

been sucked, the stone automatically falls off from the body of<br />

the victim. <strong>The</strong> stone is then put into a pot full of milk, to drain<br />

the poison within. <strong>The</strong>reafter it is kept to dry under the sun<br />

which brings the stone back to a usable condition.<br />

<strong>The</strong> use of White Elavara roots<br />

White elavara roots are used as a ‘Kema’ or a local non-scientific<br />

method of healing. It consists of traditional methods of<br />

treatment that appear to be unrelated to the ailment but strongly<br />

believed to be effective. <strong>The</strong> community believes that if you<br />

have the roots planted within the precincts of your dwelling, no<br />

serpent will visit the abode. For this Kema to be effective, the<br />

gypsies believe that the uprooting of the root must be done in<br />

a very holy and sacred manner. <strong>The</strong>y have their unique rituals<br />

when practicing this Kema.<br />

<strong>The</strong> community also uses parts of the Madara tree to ward off<br />

serpents. <strong>The</strong>y use parts of the tree as a cure for headaches and<br />

other bodily ailments alike.<br />

38 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

Traditional methods of medication

DG<br />

Traditional methods of medication<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

39

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

A vanishing community Maddili<br />

Within the Galgamuwa Giribawa electorate, in<br />

Maduragama, resides a special nomadic clan known as<br />

‘Maddili’. <strong>The</strong> clan comprises of 60 families and they live in<br />

land that is owned by the Giribawa Veheragala Purana Raja<br />

Maha Viharaya. <strong>The</strong>y seem to have moved away from their<br />

traditional nomadic lifestyle, and completely intertwined with<br />

the local Sinhalese lifestyle.<br />

To an outsider, the gypsies and Madillis would be one<br />

and the same. Both clans used <strong>The</strong>lingu as their language<br />

of communication and lived the usual nomadic lifestyle,<br />

migrating from one place to another. However, the disparity<br />

between the two groups is such that there was no evidence of<br />

even a marriage taking place between the two communities.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Maddili exhibit ‘Rilawa’- the Macaque , a local version of<br />

the monkey while the <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> are snake charmers. This is<br />

the main difference between the two groups. <strong>The</strong> forefathers<br />

of the two clans were proud of their respective livelihood<br />

and believed that one was below the other in the hierarchical<br />

structure and vice versa, therefore there was seldom an<br />

interconnection between the two exhibits. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

would never exhibit a Rilawa just as the Maddili would never<br />

charm snakes. However, economic constraints mitigated this<br />

disparity within both communities when they realised that<br />

they could earn more money by having two exhibits. Today, a<br />

majority of gypsies, carry both a snake and a monkey as props.<br />

<strong>The</strong> senior most citizen of Maduragama is known as Somasiri.<br />

However, he told us that his original name was Thangayya,<br />

which he later changed in order to integate with the new<br />

environment. According to him, his father migrated to this<br />

area during the 1940’s from a place called Variyapola Bandara<br />

Koswaththe. Upon arrival they have lived in a place called<br />

‘Hambogama’ in the vicinity of a lake. <strong>The</strong>y moved from<br />

place to place exhibiting Rilaw and were engaged in palm<br />

reading. Once they earn their wages, the men always came<br />

back to Hambogama. <strong>The</strong> reason for the shifting of residence<br />

from Hambogama to the current Maduragama was explained<br />

by the chief incumbent of the Raja Maha Viharaya, Ven.<br />

Maradankadawala Nandarama. ‘<strong>The</strong>re was an incident with<br />

a village head during the 1960s, where some traders refused<br />

to sell him palm trees because they were being transported<br />

to the Madillis. This wasn’t taken well by that arachchi. He<br />

called for a council meeting and it was unanimously decided<br />

to chase away these people. <strong>The</strong>y were given notice that<br />

evening to leave the environs of Hambogama. <strong>The</strong>y had left<br />

the place and the next day they were found in the vicinity of<br />

the temple with no place to go. <strong>The</strong> villagers were very angry<br />

with the fact that the order had not been obeyed; they were<br />

insisting that the Madillis should leave the area for good. This<br />

issue was brought to the notice of the then chief incumbent<br />

of the temple who told the Madillis to live in land owned by<br />

the temple. To this day, this is where they live. <strong>The</strong> high priest<br />

did not change his decision despite so many threats from the<br />

villagers.’<br />

<strong>The</strong> chief incumbent of the temple at the time was Ven.<br />

Weehenegama Dharmapala who then sought to transform<br />

this community. Subsequently, they gave up the practice of<br />

palm reading and exhibiting and got into other trades and<br />

industries in order to make a living. <strong>The</strong>y have erased their<br />

original identity completely, with almost all members of the<br />

clan changing their names to local Sinhalese names.<br />

40 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

A vanishing community Maddili

DS<br />

A vanishing community Maddili<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

41

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

Mahakanadarawa a village by the tank<br />

Situated on the bank of the Mahakanadarawa tank, within<br />

the jurisdiction of the Mihintale Urban Council, the<br />

Mahakanadarawa <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> village bears the interesting<br />

postal address - New Telingu village, Seepukulam, Mihintale.<br />

Currently, the village is made up of 34 families amounting to<br />

over 200 inhabitants. <strong>The</strong> village has fairly recent beginnings,<br />

with former Minister S.M. Chandrasena taking measures to<br />

provide the community with permanent housing in 1999.<br />

This resulted in the construction of nearly 30 village houses<br />

on ten perch blocks of land.<br />

Prior to their migration to the present location, the<br />

inhabitants resided in Velangamuwa, also situated in close<br />

proximity to the Mahakanadarawa tank, which is an integral<br />

part of their day to day life.<br />

Among Sri Lanka’s migrating <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> clans, two reside<br />

within this village. A majority of villagers identify themselves<br />

as ‘Lankan Telingu’ people and trace their ancestral beginnings<br />

to a community residing in Puttalam. <strong>The</strong>ir livelihoods are<br />

centered on fishing while the females exercise their traditional<br />

mode of livelihood – palm reading in public places around the<br />

sacred city of Anuradhapura.<br />

Some six families residing within the village derive their<br />

identity from the original gypsy community, tracing their<br />

beginnings to the village of Thambuththegama. <strong>The</strong> men<br />

engage in snake charming and training performing monkeys<br />

as a mode of livelihood while the women continue the<br />

tradition of palm reading.<br />

Despite living in relatively close proximity to one another,<br />

these two clans give attention and priority to preserving their<br />

separate identities. Each clan professes superiority over the<br />

other. However, it also seemed that both groups were guilty of<br />

breaking some of their traditions along the way.<br />

When probed about their religion, many inhabitants told<br />

us that traditionally they have been Buddhists but have now<br />

moved towards the religion of the Bible. Some, mentioned<br />

that they were devotees of Kali Amma. However they didn’t<br />

seem to know which strand of the ‘religion of the Bible’ they<br />

belonged to.<br />

When asked why they converted, their reasoning was very<br />

simple.<br />

‘A big party is held every Christmas and the children are<br />

showered with gifts. <strong>The</strong>y also pray for our sick and the<br />

needy’ they said. Still, many families send their children to the<br />

Buddhist temple for Sunday school.<br />

When we visited the village, the leader of the clan Aloysius,<br />

was cohabiting with a Telingu woman named Thangavelu<br />

Kamalawathie. It is worth to mention that, Aloysius claims he<br />

is a Sinhalese. Both the leader and his partner have children<br />

from separate marriages and there is no record of them being<br />

legally married to each other although they are currently living<br />

together.<br />

42 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

Mahakanadarawa a village by the tank

<strong>The</strong> villagers are burdened with many hardships. Of them,<br />

the constant lack of water is identified as the main issue. ‘<strong>The</strong><br />

closest well is situated around a quarter of a mile away from<br />

the village’ they say. <strong>The</strong>y are also challenged by the herds<br />

of wild elephant who roam the area. We were also made to<br />

understand that they were not welcome on public transport<br />

services in that area. ‘<strong>The</strong> busses don’t like to take us. <strong>The</strong>y say<br />

that we are unclean and that we smell bad’.<br />

DG<br />

Mahakanadarawa a village by the tank <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> 43

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

Kali Amma the woman who strayed away from tradition<br />

While walking towards the partially built hut of Kali Amma, who<br />

resides on the banks of the Mahakanadarawa tank with others from<br />

her community, we heard what seemed like an ongoing session of<br />

prayer.<br />

‘Pray to god to take out the devil that lies within you, Jesus Christ<br />

suffered on the cross because of your sins and he was only 33 years<br />

old. What a young age is that to go through such trauma? I’m<br />

35 now, he was younger than me at the time’ we heard someone<br />

preach.<br />

When we peered into the house we saw a young man conducting<br />

the sermon. Behind him was a picture of Jesus Christ and in front<br />

was what looked like a replica of the holy bible. <strong>The</strong> man was<br />

seated on a chair while a small group of people, including children,<br />

congregated around him. It was within this mini congregation that<br />

we found Kali Amma.<br />

<strong>The</strong> predominantly Telingu speaking population in this village<br />

had migrated to this location an year before the dawn of the new<br />

millennium. When we inquired about their lives, we were told that<br />

the new village had very little infrastructure or facilities to live a<br />

comfortable life.<br />

<strong>The</strong> villagers had sheltered themselves within a few ‘cadjan huts’<br />

and faced threats from marauding herds of wild elephant. Wild<br />

elephants are generally feared by villagers as they raid crops and<br />

cause damage to life and property.<br />

It was during this period that ‘Kali Amma’ rose to fame, speaking<br />

on behalf of the villagers who faced a multitude of obstacles in<br />

continuing their day-to-day lives. She used her eloquence to openly<br />

appeal to the authorities through both the print and electronic<br />

media in order to draw attention to the plight faced by her people.<br />

She was, for a while, representing her village as its sole leader.<br />

<strong>The</strong> moment she knew that we had come to meet her she moved<br />

out of the sermon and greeted us. However she seemed weary of<br />

talking to us, reasons which none of us had any idea about.<br />

‘I have spoken on behalf of our villagers many times and I have<br />

had to face many problems, created not by outsiders who were<br />

supposed to, but by the very people I spoke on behalf of. <strong>The</strong>refore<br />

I decided to move away from this and not to speak again. <strong>The</strong><br />

leader now is a man called Aloysius’ she said.<br />

We were fascinated by her story and intended to pursue it. We<br />

continued with what is normally termed as ‘small talk’ in order to<br />

familiarise with her and after a while she seemed to want to talk.<br />

‘We are Buddhists and our children attend Sunday school at the<br />

temple. However we also receive a lot of help from the Church.<br />

<strong>The</strong> pastor visits us every Sunday and pray for us. He teaches us<br />

the intricacies of the religion itself and pray for those who are<br />

incapacitated. But some villagers do not participate in these prayer<br />

sessions. <strong>The</strong>re is a child who is paralysed below his waist and<br />

despite many appeals to his parents to bring the child for prayers,<br />

they are yet to come’ she said lamenting at the fate that has befallen<br />

the child.<br />

We figured that this confession was indeed a good start to continue<br />

our conversation. It was interesting to note that she didn’t seem to<br />

know if she was a follower of Christianity and simply referred to<br />

her faith as the ‘religion of the Bible’.<br />

We asked her about the traditions and culture surrounding the<br />

society that she is a part of. She was at first reluctant to speak about<br />

it as was evidence by her long silence, and then again she opened<br />

up.<br />

44 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> Kali Amma the woman who strayed away from tradition

‘<strong>The</strong> only things I know about their traditions are the ones that<br />

I have learnt by observing them. <strong>The</strong>re is nothing more that I<br />

know’. This was a strange confession. How could someone be<br />

part of a clan or tribe and know nothing about their traditions<br />

and culture, other than what she has witnessed?<br />

She seemed to be contemplating about what to say next and after<br />

a while she began to speak again. This time she said that she is<br />

about to share something that she has not told anyone. We were<br />

excited and tense at the same time.<br />

‘I haven’t told this to anyone but I don’t see any point in<br />

continuing to hide this fact. I am a Sinhalese from Madatugama,<br />

Kurunegala. My mother passed away when I was a little child<br />

and so did my sister. My father died a little while later and I was<br />

orphaned with no hope. I lived with some of my relatives but had<br />

to undergo many hardships in that house. I was fed up with life.<br />

In April 1974, a trader who sold incense sticks visited our village<br />

and I decided to run away with him. He was a Telingu national<br />

and from that day onwards I decided that I’m going to be one of<br />

them’ she recalled with a sense of nostalgia.<br />

We asked her how she became the leader of the clan and why she<br />

was named Kali Amma.<br />

‘At the time there was no one to speak on behalf of the villagers,<br />

so I decided to take it upon myself to voice the hardships faced<br />

by them. This is how an outsider like me ended up being the<br />

de-facto leader of the clan. Currently many villagers use Sinhala<br />

names. However, when I came here nearly four decades ago, a<br />

Sinhala name was unheard of among them, so I called myself Kali<br />

Amma’ she said. She politely declined to share her real name with<br />

us.<br />

NG<br />

Kali Amma the woman who strayed away from tradition <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> 45

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

46 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong>

DG<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

47

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

<strong>The</strong> story of Rengasamige Masanna<br />

When we first went to meet the head of the Andarabedda<br />

village, Rengasamige Masanna, we were told that he had<br />

gone to the lake beside, in order to fish. <strong>The</strong> house was made<br />

of cement and had only two chairs which could be termed<br />

as furniture. <strong>The</strong>re was a statue of the Buddha and a picture<br />

of the deceased Ven. Gangodawila Soma. We were told that<br />

the picture of the latter was kept in the premises due to the<br />

fact that this house was built and donated to Masanna as an<br />

offering to the venerable thero.<br />

Upon hearing of our arrival Masanna proudly showed us his<br />

wealth in the form of three snakes. We were told that Masanna’s<br />

livelihood was dependent upon the wellbeing of these three<br />

animals. ‘<strong>The</strong> snakes have four castes, namely, Raja, Bamunu,<br />

Weda and Govi. Snakes of the Raja caste are very rare and<br />

I have with me snakes of the other three castes as well’ he<br />

explained.<br />

When we visited him for the second time, he had an addition<br />

to his wealth, a python. He had removed the teeth from the<br />

serpent and now uses it when exhibiting his animals. ‘I was<br />

born when the gypsies were actually migrating from place to<br />

place, with no permanent abode that was back in 1939. I spent<br />

my childhood just like my forefathers did moving from place to<br />

place with our snakes.’<br />

Apparently, he did not know his year of birth until the year<br />

1973. ‘In 1973 I had to get myself a national identity card and<br />

for that I needed my birth date, which I had no clue about.<br />

But, I knew my place of birth which was a village by the name<br />

of Pothasiyambalawa. During my birth, I heard that a healer<br />

by the name of Appuhami attended to my mother’s needs. I<br />

went in search of him. By the time I found his residence, he<br />

was dead and gone but there was a book that he had written<br />

about his healing. This book which was also used as a diary<br />

had a note regarding my birth. It was in the year 1939. That is<br />

how I have a rough idea about my age.’<br />

‘Our group consisted of about 10 to 12 families. We carried<br />

our goods on the backs of donkeys. We also had around thirty<br />

to forty goats with us. We had a few hunter dogs as well.<br />

I spent my childhood looking after the goats and hunting<br />

with my father.’ According to Masanna, he was one of the<br />

first members of the community to have formal schooling.<br />

‘My father could not read or write, but he knew the value of<br />

education. During one of our migrations, my father decided<br />

to stop at a place in Galgamuwa. <strong>The</strong>re he sent me to a<br />

Sinhala teacher who taught me Sinhala for six months. Later<br />

on he enrolled me at the Thalagaswewa School for formal<br />

education.’<br />

Due to his son’s schooling, Masanna’s father decided to make<br />

Thalgaswewa their permanent residence. Both mother and<br />

father would go out in the morning and ply their trade and<br />

then come back home at dusk. ‘My father, after about five<br />

years of living had an altercation with the owner of the land<br />

we lived on and that was the end of my schooling.<br />

48 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> story of Rengasamige Masanna

<strong>The</strong> story of Rengasamige Masanna <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> 49<br />

DS

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

My father could not read or write, but he<br />

knew the value of education<br />

We started migrating from place to place again’. After a brief<br />

sojourn, the clan decided to stay in a place near Nikerawatiya.<br />

‘I was put into the eighth grade at the local school. I was a good<br />

runner and won prizes. Both Prime Minister Bandaranaike<br />

and Sir John Kotelawala visited the school and awarded prizes<br />

to me’, boasts Masanna. His education was short-lived and he<br />

stopped schooling that year.<br />

Subsequently, he tells us ‘I had to find a way to make ends<br />

meet. I didn’t know how to charm snakes because I was<br />

attending school, while the rest learnt the art. But this was my<br />

forefather’s trade, so I started moving about with one of my<br />

elders in order to master the art. One day, when walking along<br />

the paddy fields in Veyangoda, my companion saw a snake. I<br />

watched how he caught it and then removed the poison teeth<br />

from it. <strong>The</strong>n he gave me his old snake and took the new one. I<br />

started walking alone with his snake’ recalls Masanna.<br />

His ‘first catch’ also brings out and interesting story. “Once<br />

I was walking on the roads in Homagama, suddenly a set of<br />

people saw me and shouted, ‘here is a gypsy, here is a gypsy.’ I<br />

had no clue as to why they shouted, until one man approached<br />

me and told me that there was a snake inside the house. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

wanted me to get hold of it. I started sweating because I’ve<br />

never caught a snake in my life. I felt very embarrassed and used<br />

my ‘Dutch courage’. I told myself that it doesn’t matter even if<br />

the snake bites me, I will try and tame it.<br />

Fortunately, the snake was an old one and since I acted exactly<br />

how my companion did the other day. I was able to tame it<br />

and since that day I have had no fear. I have now caught over<br />

1500 snakes” he says.<br />

Masanna married a relative of his and they lived temporarily<br />

in Medawachchiya. <strong>The</strong> whole clan was of the opinion that<br />

they needed to find permanent residence in order to provide<br />

their children with an uninterrupted education. Accordingly,<br />

the state, after many requests resettled them in the year 1969,<br />

giving them land in the District of Vavuniya at a village by<br />

the name of Nochchikulam. This clan, for the first time<br />

in its history, found solace in making a livelihood through<br />

cultivation.<br />

‘On the 17 th of August 1985, the Tamil Tigers attacked our<br />

village. All the Sinhalese people and we left Vavuniya for<br />

Anuradhdapura. We had to live in refugee camps for a few<br />

days and then we moved to Kudagama. Kudagama was also<br />

a place where many of our kind lived. We lived there till<br />

1992. But many of us didn’t like living with them. <strong>The</strong> place<br />

I call home and I know very well is Galgamuwa. <strong>The</strong>refore I<br />

requested land from Galgamuwa. A minister at the time gave<br />

us land from the area. Initially there were some families who<br />

joined me and later on five more joined us. It was in 1996<br />

that we got permanent land in Andarabedda.’ Masanna is very<br />

keen to keep the <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> tradition alive; making sure his<br />

clan adheres to all the rules and regulations.<br />

50 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> story of Rengasamige Masanna

<strong>The</strong> story of Rengasamige Masanna <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> 51<br />

DCF

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

52 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong>

DCF<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

53

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> Varigasabha<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> Community in Sri Lanka was able to hold a tribal<br />

meeting or Varigasabha for the first time in six decades with the<br />

support of Dilmah Conservation. This event took place on the banks<br />

of the Rajangana Tank in Kudagama, Thambuttegama on January 28,<br />

2011. Gypsies from all corners of Sri Lanka met as one community and<br />

spoke to each other about their lives, changing times, concerns and the<br />

need to preserve their unique identity that is disappearing in the face of<br />

modernisation.<br />

Dilmah Conservation supported the Varigasabha to enable the<br />

community leaders to come together and discuss issues that are affecting<br />

the very existence of the community and the ways in which to address<br />

them. <strong>The</strong> meeting was preceded by an elaborate cultural ceremony that<br />

commenced with flute playing and a traditional dance by the womenfolk.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Varigasabha brought together five community leaders to one<br />

platform where they discussed the problems they faced. <strong>The</strong> discussions<br />

among these leaders, K. Nadrajah of Kudagama, Enkatenna Masanna<br />

of Andarabedda, M. Rasakumara of Aligambe, Karupan Silva of<br />

Siriwallipuram and Anawattu Masanna of Kalawewa paved the way<br />

for better understanding among the communities. <strong>The</strong> community<br />

leaders discussed their core issues including the lack of infrastructure<br />

development in their respective villages; lack of employment<br />

opportunities for community members and the need to ensure that their<br />

traditional forms of livelihood are secured in the years to come.<br />

<strong>The</strong> leaders made a pledge to unite in order to strengthen and save<br />

their unique cultural identity. <strong>The</strong> first Charter of the Ahinkuntaka<br />

community, the ‘Kudagama Charter of the Sri Lanka <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

Community’ was brought forward endorsed by the five community<br />

leaders on behalf of their communities. This is regarded as a landmark<br />

event not only for a minority community in Sri Lanka but also for the<br />

worldwide Gypsy community at large.<br />

54 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> Varigasabha

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> Varigasabha <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> 55<br />

DG

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

Kudagama Charter<br />

We belong to the clan called Ahikuntika, and we do hereby issue this<br />

statement on the banks of the Rajangana Tank of Thambuttegama in<br />

the historically acclaimed city of Anuradhapura on this day of 28th<br />

January 2011. First and foremost we take pleasure in elucidating of<br />

our clan which is less exposed to publicity.<br />

We are commonly known as Ahikuntika at present, although we<br />

were called by various other names in the past such as Nai Panikkiyo<br />

and Nai karayo (cobra charmers). Different communities have their<br />

own names for us. To mention a few, people of the Vanni address us<br />

as Kuthandi, while Kurawan, Kuravar, Vahakkuravan or Kattuvasi<br />

are the Tamil names for us. Our culture and identity are based<br />

chiefly on our traditional profession- snake charming and our life<br />

style which is one that is not stagnant at a particular place. It is a<br />

known fact that we have lived a gypsy life. <strong>The</strong> language we speak is<br />

Telungu which is the state language of Andra Pradesh in India. That<br />

fact provides evidence of our tourist life style and the fact that we<br />

arrived in Sri Lanka from another state.<br />

Our mode of transport in the past was carrying goods on donkeys.<br />

We used to travel around the country to engage in our professions.<br />

It is noteworthy to mention that during the middle of the previous<br />

century, the Sri Lankan government took several measures to<br />

settle our community in colonies. As a result of that at present the<br />

Ahikuntika community is settled in Kudagama of Thambuttegama,<br />

Kalaweva, Aligambay, Sirivallipuram of Akkaraipattu in Ampara<br />

and Andarabedda of Kurunegala. Although the highest density<br />

of Ahikuntika people is living in the aforementioned areas, the<br />

population is scattered on a small scale throughout the country. We<br />

are a minority group of people in Sri Lanka of which the number of<br />

families does not exceed thousand.<br />

With pride we mention that, even though we are a minority<br />

community, our contribution towards nourishing Sri Lankan<br />

cultural diversity is significant. Our cultural identity plays a major<br />

role in that context. For a slight elaboration of our cultural identity,<br />

we are pleased to make mention of the snake charming and monkey<br />

performing, fortune telling and gypsy lifestyle which distinguishes<br />

the Ahikuntika community from others.<br />

We are confident that our community is strong enough to live on its<br />

own and in nowhere in history is it mentioned of our conditional<br />

protests against the majority community in Sri Lanka.<br />

Unlike at present, there were lesser amusement oriented events in<br />

the past. It will not be pretentious if our community alone bags that<br />

pride of being the one and only entertainer of the nation during the<br />

past.<br />

We do not deny the fact that our community too has been affected<br />

by the social, religious and economic upheavals during the past<br />

few decades. <strong>The</strong> fact that our community has been unpleasantly<br />

affected by the aforementioned conditions should not be omitted<br />

though the space does not warrant pinning them all down. We can<br />

still cite some examples; due to the rapid urbanization taking place,<br />

we are facing the threat of losing sterile lands which we use to put up<br />

our temporary tents during our tours around the country. As a result<br />

of this, we are compelled to give up our gypsy life style which is one<br />

of our major means of living. This has also adversely affected our<br />

economic status. Moreover it resulted in the erosion of our traditions<br />

and culture.<br />

<strong>The</strong> main purpose of this gathering of the Ahikuntika leaders<br />

from all five villages, on the banks of the Rajangana Tank of<br />

Thambuttegama today is to put forward and address our problems<br />

and grievances. It is also expected to draw the attention of every<br />

potential philanthropist who could assist us in solving our problems.<br />

56 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

Kudagama Charter

We strive towards re-establishing our diminishing culture.<br />

We affirm that we will continue our peace-loving lifestyle with<br />

no involvement in uprisings of any kind against anybody or any<br />

authority.<br />

With this affirmation, we enclose herewith a document consisting<br />

of the issues we are currently facing. It is our sincere hope that the<br />

relevant authorities would pay serious attention to them.<br />

Finally, we put forward our humble request - assist us in preserving<br />

our precious traditions and culture while going hand in hand with<br />

modernization.<br />

We offer our sincere and heartfelt gratitude and honor to Dilmah<br />

Conservation which extended a liberal hand in organizing this<br />

Variga Sabha after a lapse of over sixty years which was a long felt<br />

need. Last but not least, the staff of the Divisional Secretariat of<br />

Thambuttegama is highly appreciated for their hard work towards<br />

the success of our program.<br />

Thank You.<br />

This charter has been discussed and ratified on the banks of the<br />

Rajangana Tank of Kudagama, Thambuttegama at 7.30 pm on<br />

28.01.2011 by our community and signed by the following leaders<br />

on behalf of their communities.<br />

1. Nadarajah of Kudagama<br />

2. Egatannage Masanna of Andarabedda<br />

3. Anawattu Masanna of Kalawewa<br />

4. M. Rasakumar of Aligambe<br />

5. Karupan Silva of Sirivallipuram<br />

DS<br />

Kudagama Charter<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

57

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

58 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong>

DG<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

59

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

Preserving their cultural identity<br />

As a result of the Varigasabha and subsequent discussions<br />

with the <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> community, Dilmah Conservation<br />

undertook to support the preservation of this unique<br />

communities’ cultural identity. As part of these efforts, the<br />

<strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> Resource Centre was built in Kudagama in<br />

Thambuttegama. <strong>The</strong> Centre has an open air theatre and a<br />

museum to house traditional arts and crafts. All these efforts<br />

are aimed at making Kudagama into a tourist hub visited by<br />

locals and foreigners alike. Dilmah Conservation envisages<br />

that the <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> Resource Centre will not only lead to<br />

the preservation of their identity and culture but it will also<br />

lead to the general upliftment of their social conditions.<br />

<strong>The</strong> design and construction of the Centre is handled by the<br />

Department of Architecture of the University of Moratuwa<br />

while the Divisional Secretariat of Thambuttegama is<br />

working in collaboration with Dilmah Conservation to<br />

complete the project.<br />

60 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

Preserving their cultural identity

An architect’s impression of the<br />

Kudagama <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> Resource Centre<br />

Preserving their cultural identity <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong> 61

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

62 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong>

DG<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ahikuntaka</strong><br />

63

www.dilmahconservation.org<br />

A Baseline Survey of Sri Lankan Nomads –<br />

<strong>The</strong> Gypsies in Sri Lanka by Professor Ranjith Bandara<br />

Conducted from March to August 2011.<br />

<strong>The</strong> study was conducted as result of the request made by Dilmah Conservation to the University of Colombo to carry out a<br />

comprehensive study on the socio economic aspects of the Ahikuntika Community in Sri Lanka. It was done as part of Dilmah’s<br />

Culture & Indigenous Communities Programme, which aims to collate information on traditional communities in Sri Lanka and<br />

publish the findings in a series of publications.<br />

Executive Summary<br />

This report is based on a baseline survey of Sri Lankan nomads - “the gypsies in Sri Lanka” carried out by the researcher on all<br />

gypsy families in a government settlement in the village of Kudagama in the North Central Province adopting stratified random<br />

sampling tech¬niques. Baseline information with reference to four main sectors - ethnographic analysis, current socio-economic<br />

condition of the community, issues concerning the upliftment of the socioeconomic conditions of the community without hindering<br />

the cultural heritage of the gypsies and measures to empower them were obtained. In the process of data collection three data collecting<br />

instruments, namely: semi-structured questionnaires, focus group discussions and interactive group sessions were used to elicit the<br />

desired information. As such the research survey is a comprehensive analysis of the Sri Lankan gypsy community with reference to their<br />

culture and society in the chang¬ing world, encompassing all aspects of the life of a gypsy.<br />

<strong>The</strong> researcher has dealt with heads of households with relation to gender and age, the type of abode (residence), family size,<br />

distribution of individuals in the community with relevance to age, level of education and educational attainment, type of occupation,<br />

civil status, gender distribution, number employed in a family, nature of employment, total monthly family income, monthly<br />

expen¬diture as a percentage of the income, borrowing and purpose of borrowing, lending sources, satis¬faction in the socio-economic<br />

status, characterisation of their culture, their opinion with regard to the uniqueness of their culture, whether they feel there is a threat<br />

to their culture, if so why and if not why they feel so. <strong>The</strong>ir reaction to the proposal by the Dilmah conservation in collaboration with<br />

the Sri Lanka Tourism Authority, their expectations of possible further integration into the mainstream society, the extent to which they<br />

have adopted cultural aspects of the mainstream society, their inte¬gration to mainstream society as individuals and as a community<br />

and why they feel they are well integrated into the mainstream society, their access to public amenities, public utilities and their cultural<br />

remnants which could be preserved for the next generation.<br />