Encyclopedia of Buddhism Volume One A -L Robert E. Buswell

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF<br />

BUDDHISM

EDITORIAL BOARD<br />

EDITOR IN CHIEF<br />

<strong>Robert</strong> E. <strong>Buswell</strong>, Jr.<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Buddhist Studies and Chair, Department <strong>of</strong> Asian Languages and Cultures<br />

Director, Center for Buddhist Studies<br />

University <strong>of</strong> California, Los Angeles<br />

BOARD MEMBERS<br />

William M. Bodiford<br />

Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Buddhist Studies<br />

University <strong>of</strong> California, Los Angeles<br />

Donald S. Lopez, Jr.<br />

Carl W. Belser Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Buddhist and Tibetan Studies<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Michigan<br />

John S. Strong<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Religion and Chair, Department <strong>of</strong> Philosophy and Religion<br />

Bates College<br />

Eugene Y. Wang<br />

Gardner Cowles Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> History <strong>of</strong> Art and Architecture<br />

Harvard University

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF<br />

BUDDHISM<br />

<strong>Volume</strong> <strong>One</strong><br />

A-L<br />

<strong>Robert</strong> E. <strong>Buswell</strong>, Jr., Editor in Chief

<strong>Encyclopedia</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

<strong>Robert</strong> E. <strong>Buswell</strong>, Jr., Editor in Chief<br />

©2004 by Macmillan Reference USA.<br />

Macmillan Reference USA is an imprint <strong>of</strong><br />

The Gale Group, Inc., a division <strong>of</strong><br />

Thomson Learning, Inc.<br />

Macmillan Reference USA and<br />

Thomson Learning are trademarks used<br />

herein under license.<br />

For more information, contact<br />

Macmillan Reference USA<br />

300 Park Avenue South, 9th Floor<br />

New York, NY 10010<br />

Or you can visit our Internet site at<br />

http://www.gale.com<br />

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED<br />

No part <strong>of</strong> this work covered by the copyright<br />

hereon may be reproduced or used<br />

in any form or by any means—graphic,<br />

electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying,<br />

recording, taping, Web distribution,<br />

or information storage retrieval<br />

systems—without the written permission<br />

<strong>of</strong> the publisher.<br />

For permission to use material from this<br />

product, submit your request via Web at<br />

http://www.gale-edit.com/permissions, or<br />

you may download our Permissions Request<br />

form and submit your request by fax or<br />

mail to:<br />

Permissions Department<br />

The Gale Group, Inc.<br />

27500 Drake Road<br />

Farmington Hills, MI 48331-3535<br />

Permissions Hotline:<br />

248-699-8006 or 800-877-4253 ext. 8006<br />

Fax: 248-699-8074 or 800-762-4058<br />

While every effort has been made to ensure<br />

the reliability <strong>of</strong> the information presented<br />

in this publication, The Gale Group,<br />

Inc. does not guarantee the accuracy <strong>of</strong> the<br />

data contained herein. The Gale Group, Inc.<br />

accepts no payment for listing; and inclusion<br />

in the publication <strong>of</strong> any organization,<br />

agency, institution, publication, service, or<br />

individual does not imply endorsement <strong>of</strong><br />

the editors or publisher. Errors brought to<br />

the attention <strong>of</strong> the publisher and verified<br />

to the satisfaction <strong>of</strong> the publisher will be<br />

corrected in future editions.<br />

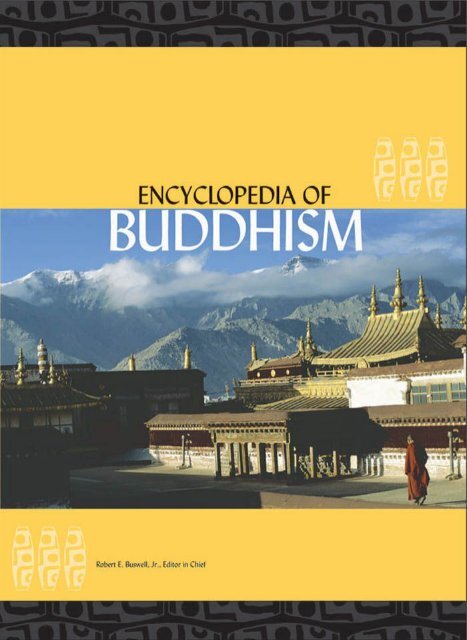

Cover photograph <strong>of</strong> the Jo khang<br />

Temple in Lhasa, Tibet reproduced by<br />

permission. © Chris Lisle/Corbis.<br />

The publisher wishes to thank the<br />

Vergleichende Sprachwissenschaft (Institute<br />

<strong>of</strong> Comparative Linguistics) <strong>of</strong> the University<br />

<strong>of</strong> Frankfurt, and particularly Dr. Jost<br />

Gippert, for their kind permission to use<br />

the TITUS Cyberbit font in preparing the<br />

manuscript for the <strong>Encyclopedia</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Buddhism</strong>.<br />

This font was specially developed<br />

by the institute for use by scholars working<br />

on materials in Asian languages and enables<br />

the accurate transliteration with diacriticals<br />

<strong>of</strong> texts from those languages. Further<br />

information may be found at<br />

http://titus.fkidg1.uni-frankfurt.de.<br />

<strong>Encyclopedia</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Buddhism</strong> / edited by <strong>Robert</strong> E. <strong>Buswell</strong>, Jr.<br />

p. cm.<br />

Includes bibliographical references and index.<br />

ISBN 0-02-865718-7(set hardcover : alk. paper) — ISBN 0-02-865719-5<br />

(<strong>Volume</strong> 1) — ISBN 0-02-865720-9 (<strong>Volume</strong> 2)<br />

1. <strong>Buddhism</strong>—<strong>Encyclopedia</strong>s. I. <strong>Buswell</strong>, <strong>Robert</strong> E.<br />

BQ128.E62 2003<br />

294.3’03—dc21<br />

2003009965<br />

This title is also available as an e-book.<br />

ISBN 0-02-865910-4 (set)<br />

Contact your Gale sales representative for ordering information.<br />

Printed in the United States <strong>of</strong> America<br />

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS<br />

Preface. .............................................................vii<br />

List <strong>of</strong> Articles ........................................................xi<br />

List <strong>of</strong> Contributors ..................................................xix<br />

Synoptic Outline <strong>of</strong> Entries ...........................................xxvii<br />

Maps: The Diffusion <strong>of</strong> <strong>Buddhism</strong> .....................................xxxv<br />

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF BUDDHISM<br />

Appendix: Timelines <strong>of</strong> Buddhist History ................................931<br />

Index ..............................................................945<br />

v

EDITORIAL AND PRODUCTION STAFF<br />

Linda S. Hubbard<br />

Editorial Director<br />

Judith Culligan, Anjanelle Klisz, Oona Schmid, and Drew Silver<br />

Project Editors<br />

Shawn Beall, Mark Mikula, Kate Millson, and Ken Wachsberger<br />

Editorial Support<br />

Judith Culligan<br />

Copy Editor<br />

Amy Unterburger<br />

Pro<strong>of</strong>reader<br />

Lys Ann Shore<br />

Indexer<br />

Barbara Yarrow<br />

Manager, Imaging and Multimedia Content<br />

Robyn Young<br />

Project Manager, Imaging and Multimedia Content<br />

Lezlie Light<br />

Imaging Coordinator<br />

Tracey Rowens<br />

Product Design Manager<br />

Jennifer Wahi<br />

Art Director<br />

GGS, Inc.<br />

Typesetter<br />

Mary Beth Trimper<br />

Manager, Composition<br />

Evi Seoud<br />

Assistant Manager, Composition<br />

Wendy Blurton<br />

Manufacturing Specialist<br />

MACMILLAN REFERENCE USA<br />

Frank Menchaca<br />

Vice President<br />

Hélène Potter<br />

Director, New Product Development<br />

vi

PREFACE<br />

<strong>Buddhism</strong> is one <strong>of</strong> the three major world religions, along with Christianity and Islam,<br />

and has a history that is several centuries longer than either <strong>of</strong> its counterparts.<br />

Starting in India some twenty-five hundred years ago, Buddhist monks and nuns almost<br />

immediately from the inception <strong>of</strong> the dispensation began to “to wander forth<br />

for the welfare and weal <strong>of</strong> the many, out <strong>of</strong> compassion for the world,” commencing<br />

one <strong>of</strong> the greatest missionary movements in world religious history. Over the next<br />

millennium, <strong>Buddhism</strong> spread from India throughout the Asian continent, from the<br />

shores <strong>of</strong> the Caspian Sea in the west, to the Inner Asian steppes in the north, the<br />

Japanese isles in the east, and the Indonesian archipelago in the south. In the modern<br />

era, <strong>Buddhism</strong> has even begun to build a significant presence in the Americas and<br />

Europe among both immigrant and local populations, transforming it into a religion<br />

with truly global reach. Buddhist terms such as karma, nirvana, sam sara, and koan<br />

have entered common parlance and Buddhist ideas have begun to seep deeply into<br />

both Western thought and popular culture.<br />

The <strong>Encyclopedia</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Buddhism</strong> is one <strong>of</strong> the first major reference tools to appear in<br />

any Western language that seeks to document the range and depth <strong>of</strong> the Buddhist<br />

tradition in its many manifestations. In addition to feature entries on the history and<br />

impact <strong>of</strong> <strong>Buddhism</strong> in different cultural regions and national traditions, the work<br />

also covers major doctrines, texts, people, and schools <strong>of</strong> the religion, as well as practical<br />

aspects <strong>of</strong> Buddhist meditation, liturgy, and lay training. Although the target audience<br />

is the nonspecialist reader, even serious students <strong>of</strong> the tradition should find<br />

much <strong>of</strong> benefit in the more than four hundred entries.<br />

Even with over 500,000 words at our disposal, the editorial board realized early on<br />

that we had nowhere nearly enough space to do justice to the full panoply <strong>of</strong> Buddhist<br />

thought, practice, and culture within each major Asian tradition. In order to accommodate<br />

as broad a range <strong>of</strong> research as possible, we decided at the beginning <strong>of</strong> the<br />

project to abandon our attempt at a comprehensive survey <strong>of</strong> major topics in each<br />

principal Asian tradition and instead build our coverage around broader thematic entries<br />

that would cut across cultural boundaries. Thus, rather than separate entries on<br />

the Huichang persecution <strong>of</strong> <strong>Buddhism</strong> in China or the Chosŏn suppression in Korea,<br />

for example, we have instead a single thematic entry on persecutions; we follow a<br />

similar approach with such entries as conversion, festivals and calendrical rituals, millenarianism<br />

and millenarian movements, languages, and stupas. We make no pretense<br />

to comprehensiveness in every one <strong>of</strong> these entries; when there are only a handful <strong>of</strong><br />

vii

P REFACE<br />

entries in the <strong>Encyclopedia</strong> longer than four thousand words, this would have been a<br />

pipe dream, at best. Instead, we encouraged our contributors to examine their topics<br />

comparatively, presenting representative case studies on the topic, with examples<br />

drawn from two or more traditions <strong>of</strong> <strong>Buddhism</strong>.<br />

The <strong>Encyclopedia</strong> also aspires to represent the emphasis in the contemporary field<br />

<strong>of</strong> Buddhist studies on the broader cultural, social, institutional, and political contexts<br />

<strong>of</strong> Buddhist thought and practice. There are substantial entries on topics as diverse as<br />

economics, education, the family, law, literature, kingship, and politics, to name but<br />

a few, all <strong>of</strong> which trace the role <strong>Buddhism</strong> has played as one <strong>of</strong> Asia’s most important<br />

cultural influences. Buddhist folk religion, in particular, receives among the most<br />

extensive coverage <strong>of</strong> any topic in the encyclopedia. Many entries also explore the continuing<br />

relevance <strong>of</strong> <strong>Buddhism</strong> in contemporary life in Asia and, indeed, throughout<br />

the world.<br />

Moreover, we have sought to cross the intellectual divide that separates texts and<br />

images by <strong>of</strong>fering extensive coverage <strong>of</strong> Buddhist art history and material culture. Although<br />

we had no intention <strong>of</strong> creating an encyclopedia <strong>of</strong> Buddhist art, we felt it was<br />

important to <strong>of</strong>fer our readers some insight into the major artistic traditions <strong>of</strong> <strong>Buddhism</strong>.<br />

We also include brief entries on a couple <strong>of</strong> representative sites in each tradition;<br />

space did not allow us even to make a pretense <strong>of</strong> being comprehensive, so we<br />

focused on places or images that a student might be most likely to come across in<br />

reading about a specific tradition. We have also sought to provide some coverage <strong>of</strong><br />

Buddhist material culture in such entries as amulets and talismans, medicine, monastic<br />

architecture, printing technologies, ritual objects, and robes and clothing.<br />

<strong>One</strong> <strong>of</strong> the major goals <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Encyclopedia</strong> is to better integrate Buddhist studies<br />

into research on religion and culture more broadly. When the editorial board was<br />

planning the entries, we sought to provide readers with Buddhist viewpoints on such<br />

defining issues in religious studies as conversion, evil, hermeneutics, pilgrimage, ritual,<br />

sacred space, and worship. We also explore Buddhist perspectives on topics <strong>of</strong><br />

great currency in the contemporary humanities, such as the body, colonialism, gender,<br />

modernity, nationalism, and so on. These entries are intended to help ensure that<br />

Buddhist perspectives become mainstreamed in Western humanistic research.<br />

We obviously could not hope to cover the entirety <strong>of</strong> <strong>Buddhism</strong> in a two-volume<br />

reference. The editorial board selected a few representative monks, texts, and sites for<br />

each <strong>of</strong> the major cultural traditions <strong>of</strong> the religion, but there are inevitably many<br />

desultory lacunae. Much <strong>of</strong> the specific coverage <strong>of</strong> people, texts, places, and practices<br />

is embedded in the larger survey pieces on <strong>Buddhism</strong> in India, China, Tibet, and so<br />

forth, as well as in relevant thematic articles, and those entries should be the first place<br />

a reader looks for information. We also use a comprehensive set <strong>of</strong> internal cross-references,<br />

which are typeset as small caps, to help guide the reader to other relevant entries<br />

in the <strong>Encyclopedia</strong>. Listings for monks proved unexpectedly complicated. Monks,<br />

especially in East Asia, <strong>of</strong>ten have a variety <strong>of</strong> different names by which they are known<br />

to the tradition (ordained name, toponym, cognomen, style, honorific, funerary name,<br />

etc.) and Chinese monks, for example, may <strong>of</strong>ten be better known in Western literature<br />

by the Japanese pronunciation <strong>of</strong> their names. As a general, but by no means inviolate,<br />

rule, we refer to monks by the language <strong>of</strong> their national origin and their name<br />

at ordination. So the entry on the Chinese Chan (Zen) monk <strong>of</strong>ten known in Western<br />

writings as Rinzai, using the Japanese pronunciation <strong>of</strong> his Chinese toponym Linji,<br />

will be listed here by his ordained name <strong>of</strong> Yixuan. Some widely known alternate<br />

names will be given as blind entries, but please consult the index if someone is difficult<br />

to locate. We also follow the transliteration systems most widely employed today<br />

viii E NCYCLOPEDIA OF B UDDHISM

P REFACE<br />

for rendering Asian languages: for example, pinyin for Chinese, Wylie for Tibetan, Revised<br />

Hepburn for Japanese, McCune-Reischauer for Korean.<br />

For the many buddhas, bodhisattvas, and divinities known to the Buddhist tradition,<br />

the reader once again should first consult the major thematic entry on buddhas,<br />

etc., for a survey <strong>of</strong> important figures within each category. We will also have a few<br />

independent entries for some, but by no means all, <strong>of</strong> the most important individual<br />

figures. We will typically refer to a buddha like Amitabha, who is known across traditions,<br />

according to the Buddhist lingua franca <strong>of</strong> Sanskrit, not by the Chinese pronunciation<br />

Amito or Japanese Amida; similarly, we have a brief entry on the<br />

bodhisattva Maitreya, which we use instead <strong>of</strong> the Korean Mirŭk or Japanese Miroku.<br />

For pan-Buddhist terms common to most Buddhist traditions, we again use the<br />

Sanskrit as a lingua franca: thus, dhyana (trance state), duhkha (suffering), skandha<br />

(aggregate), and śunyata (emptiness). But again, many terms are treated primarily in<br />

relevant thematic entries, such as samadhi in the entry on meditation. Buddhist terminology<br />

that appears in Webster’s Third International Dictionary we regard as English<br />

and leave unitalicized: this includes such technical terms as dharan, koan, and<br />

tathagatagarbha. For a convenient listing <strong>of</strong> a hundred such terms, see Roger Jackson,<br />

“Terms <strong>of</strong> Sanskrit and Pali Origin Acceptable as English Words,” Journal <strong>of</strong> the International<br />

Association <strong>of</strong> Buddhist Studies 5 (1982), pp. 141–142.<br />

Buddhist texts are typically cited by their language <strong>of</strong> provenance, so the reader will<br />

find texts <strong>of</strong> Indian provenance listed via their Sanskrit titles (e.g., Sukhavatlvyu hasu<br />

tra, Sam dhinirmocana-su tra), indigenous Chinese sutras by their Chinese titles (e.g.,<br />

Fanwang jing, Renwang jing), and so forth. Certain scriptures that have widely recognized<br />

English titles are however listed under that title, as with Awakening <strong>of</strong> Faith, Lotus<br />

Su tra, Nirvana Su tra, and Tibetan Book <strong>of</strong> the Dead.<br />

Major Buddhist schools, similarly, are listed according to the language <strong>of</strong> their origin.<br />

In East Asia, for example, different pronunciations <strong>of</strong> the same Sinitic logograph<br />

obscure the fact that Chan, Sŏn, Zen, and Thiê`n are transliterations <strong>of</strong> respectively the<br />

Chinese, Korean, Japanese, and Vietnamese pronunciations for the school we generally<br />

know in the West as Zen. We have therefore given our contributors the daunting<br />

task <strong>of</strong> cutting across national boundaries and treating in single, comprehensive entries<br />

such pan-Asian traditions as Madhyamaka, Tantra, and Yogacara, or such pan-<br />

East Asian schools as Huayan, Tiantai, and Chan. These entries are among the most<br />

complex in the encyclopedia, since they must not only touch upon the major highlights<br />

<strong>of</strong> different national traditions, but also lay out in broad swathe an overarching<br />

account <strong>of</strong> a school’s distinctive approach and contribution to Buddhist thought and<br />

practice.<br />

Compiling an <strong>Encyclopedia</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Buddhism</strong> may seem a quixotic quest, given the past<br />

track records <strong>of</strong> similar Western-language projects. I was fortunate to have had the<br />

help <strong>of</strong> an outstanding editorial board, which was determined to ensure that this encyclopedia<br />

would stand as a definitive reference tool on <strong>Buddhism</strong> for the next generation—and<br />

that it would be finished in our lifetimes. Don Lopez and John Strong<br />

both brought their own substantial expertise with editing multi-author references to<br />

the project, which proved immensely valuable in planning this encyclopedia and keeping<br />

the project moving along according to schedule. My UCLA colleague William Bodiford<br />

surveyed Japanese-language Buddhist encyclopedias for the board and constantly<br />

pushed us to consider how we could convey in our entries the ways in which Buddhist<br />

beliefs were lived out in practice. The board benefited immensely in the initial<br />

planning stages from the guidance art historian Maribeth Graybill <strong>of</strong>fered in trying to<br />

E NCYCLOPEDIA OF B UDDHISM<br />

ix

P REFACE<br />

conceive how to provide a significant place in our coverage for Buddhist art. Eugene<br />

Wang did yeoman’s service in stepping in later as our art-history specialist on the<br />

board. Words cannot do justice to the gratitude I feel for the trenchant advice, ready<br />

good humor, and consistently hard work <strong>of</strong>fered by all the board members.<br />

I also benefited immensely from the generous assistance, advice, and support <strong>of</strong> the<br />

faculty, staff, and graduate students affiliated with UCLA’s Center for Buddhist Studies,<br />

which has spearheaded this project since its inception. I am especially grateful to<br />

my faculty colleagues in Buddhist Studies at UCLA, whose presence here gave me both<br />

the courage even to consider undertaking such a daunting task and the manpower to<br />

finish it: Gregory Schopen, William Bodiford, Jonathan Silk, <strong>Robert</strong> Brown, and Don<br />

McCallum.<br />

The <strong>Encyclopedia</strong> was fortunate to have behind it the support <strong>of</strong> the capable staff<br />

at Macmillan. Publisher Elly Dickason and our first editor Judy Culligan helped guide<br />

the editorial board through our initial framing <strong>of</strong> the encyclopedia and structuring <strong>of</strong><br />

the entries; we were fortunate to have Judy return as our copyeditor later in the project.<br />

Oona Schmid, who joined the project just as we were finalizing our list <strong>of</strong> entries<br />

and sending out invitations to contributors, was an absolutely superlative editor, cheerleader,<br />

and colleague. Her implacable enthusiasm for the project was infectious and<br />

helped keep both the board and our contributors moving forward even during the<br />

most difficult stages <strong>of</strong> the project. Our next publisher, Hélène Potter, was a stabilizing<br />

force during the most severe moments <strong>of</strong> impermanence. Our last editor, Drew<br />

Silver, joined us later in the project, but his assistance was indispensable in taking care<br />

<strong>of</strong> the myriad details involved in bringing the project to completion. Jan Klisz was absolutely<br />

superb at moving the volumes through production. All <strong>of</strong> us on the board<br />

looked askance when Macmillan assured us at our first editorial meeting that we would<br />

finish this project in three years, but the pr<strong>of</strong>essionalism <strong>of</strong> its staff made it happen.<br />

Finally, I would like to express my deepest thanks to the more than 250 colleagues<br />

around the world who willingly gave <strong>of</strong> their time, energy, and knowledge in order to<br />

bring the <strong>Encyclopedia</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Buddhism</strong> to fruition. I am certain that current and future<br />

generations <strong>of</strong> students will benefit from our contributors’ insightful treatments <strong>of</strong><br />

various aspects <strong>of</strong> the Buddhist religious tradition. As important as encyclopedia articles<br />

are for building a field, they inevitably take a back seat to one’s “real” research<br />

and writing, and rarely receive the recognition they deserve for tenure or promotion.<br />

At very least, our many contributors can be sure that they have accrued much merit—<br />

at least in my eyes—through their selfless acts <strong>of</strong> disseminating the dharma.<br />

ROBERT E. BUSWELL, JR.<br />

x E NCYCLOPEDIA OF B UDDHISM

LIST OF ARTICLES<br />

Abhidharma<br />

Collett Cox<br />

Abhidharmakośabhasya<br />

Collett Cox<br />

Abhijña (Higher Knowledges)<br />

Patrick A. Pranke<br />

Abortion<br />

George J. Tanabe, Jr.<br />

A gama/Nikaya<br />

Jens-Uwe Hartmann<br />

Ajanta<br />

Leela Aditi Wood<br />

Aksobhya<br />

Jan Nattier<br />

A layavijñana<br />

John S. Strong<br />

Alchi<br />

Roger Goepper<br />

Ambedkar, B. R.<br />

Christopher S. Queen<br />

Amitabha<br />

Luis O. Gómez<br />

Amulets and Talismans<br />

Michael R. Rhum<br />

Anagarika Dharmapala<br />

George D. Bond<br />

A nanda<br />

Bhikkhu Pasadika<br />

Ananda Temple<br />

Paul Strachan<br />

Anathapindada<br />

Joel Tatelman<br />

Anatman/A tman (No-self/Self)<br />

K. T. S. Sarao<br />

Ancestors<br />

Mariko Namba Walter<br />

Anitya (Impermanence)<br />

Carol S. Anderson<br />

An Shigao<br />

Paul Harrison<br />

Anuttarasamyaksam bodhi<br />

(Complete, Perfect Awakening)<br />

William M. Bodiford<br />

Apocrypha<br />

Kyoko Tokuno<br />

Arhat<br />

George D. Bond<br />

Arhat Images<br />

Richard K. Kent<br />

A ryadeva<br />

Karen Lang<br />

A ryaśura<br />

Peter Khoroche<br />

Asaṅga<br />

John P. Keenan<br />

Ascetic Practices<br />

Liz Wilson<br />

Aśoka<br />

John S. Strong<br />

Aśvaghosa<br />

Peter Khoroche<br />

Atisha<br />

Gareth Sparham<br />

Avadana<br />

Joel Tatelman<br />

Avadanaśataka<br />

Joel Tatelman<br />

Awakening <strong>of</strong> Faith (Dasheng<br />

qixin lun)<br />

Ding-hwa Hsieh<br />

Ayutthaya<br />

Pattaratorn Chirapravati<br />

Bamiyan<br />

Karil J. Kucera<br />

Bayon<br />

Eleanor Mannikka<br />

Bhavaviveka<br />

Paul Williams<br />

Bianwen<br />

Victor H. Mair<br />

Bianxiang (Transformation<br />

Tableaux)<br />

Victor H. Mair<br />

Biographies <strong>of</strong> Eminent Monks<br />

(Gaoseng zhuan)<br />

John Kieschnick<br />

Biography<br />

Juliane Schober<br />

Bka’ brgyud (Kagyu)<br />

Andrew Quintman<br />

Bodh Gaya<br />

Leela Aditi Wood<br />

xi

L IST OF A RTICLES<br />

Bodhi (Awakening)<br />

<strong>Robert</strong> M. Gimello<br />

Bodhicaryavatara<br />

Paul Williams<br />

Bodhicitta (Thought <strong>of</strong> Awakening)<br />

Luis O. Gómez<br />

Bodhidharma<br />

Jeffrey Broughton<br />

Bodhisattva(s)<br />

Leslie S. Kawamura<br />

Bodhisattva Images<br />

Charles Lachman<br />

Body, Perspectives on the<br />

Liz Wilson<br />

Bon<br />

Christian K. Wedemeyer<br />

Borobudur<br />

John N. Miksic<br />

Bsam yas (Samye)<br />

Jacob P. Dalton<br />

Bsam yas Debate<br />

Jacob P. Dalton<br />

Buddha(s)<br />

Jan Nattier<br />

Buddhacarita<br />

John S. Strong<br />

Buddhadasa<br />

Christopher S. Queen<br />

Buddhaghosa<br />

John S. Strong<br />

Buddhahood and Buddha Bodies<br />

John J. Makransky<br />

Buddha Images<br />

<strong>Robert</strong> L. Brown<br />

Buddha, Life <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Heinz Bechert<br />

Buddha, Life <strong>of</strong> the, in Art<br />

Gail Maxwell<br />

Buddhanusmrti (Recollection <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Buddha)<br />

Paul Harrison<br />

Buddhavacana (Word <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Buddha)<br />

George D. Bond<br />

Buddhist Studies<br />

Jonathan A. Silk<br />

Burmese, Buddhist Literature in<br />

Jason A. Carbine<br />

Bu ston (Bu tön)<br />

Gareth Sparham<br />

Cambodia<br />

Anne Hansen<br />

Candrakl rti<br />

Roger R. Jackson<br />

Canon<br />

Paul Harrison<br />

Catalogues <strong>of</strong> Scriptures<br />

Kyoko Tokuno<br />

Cave Sanctuaries<br />

Denise Patry Leidy<br />

Central Asia<br />

Jan Nattier<br />

Central Asia, Buddhist Art in<br />

Roderick Whitfield<br />

Chan Art<br />

Charles Lachman<br />

Chan School<br />

John Jorgensen<br />

Chanting and Liturgy<br />

George J. Tanabe, Jr.<br />

Chengguan<br />

Mario Poceski<br />

China<br />

Mario Poceski<br />

China, Buddhist Art in<br />

Marylin Martin Rhie<br />

Chinese, Buddhist Influences on<br />

Vernacular Literature in<br />

Victor H. Mair<br />

Chinul<br />

Sung Bae Park<br />

Chogye School<br />

Jongmyung Kim<br />

Christianity and <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

James W. Heisig<br />

Clerical Marriage in Japan<br />

Richard M. Jaffe<br />

Colonialism and <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

Richard King<br />

Commentarial Literature<br />

Alexander L. Mayer<br />

Communism and <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

Jin Y. Park<br />

Confucianism and <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

George A. Keyworth<br />

Consciousness, Theories <strong>of</strong><br />

Nobuyoshi Yamabe<br />

Consecration<br />

Donald K. Swearer<br />

Conversion<br />

Jan Nattier<br />

Cosmology<br />

Rupert Gethin<br />

Councils, Buddhist<br />

Charles S. Prebish<br />

Critical <strong>Buddhism</strong> (Hihan Bukkyo)<br />

Jamie Hubbard<br />

Daimoku<br />

Jacqueline I. Stone<br />

Daitokuji<br />

Karen L. Brock<br />

D akinl <br />

Jacob P. Dalton<br />

Dalai Lama<br />

Gareth Sparham<br />

Dana (Giving)<br />

Maria Heim<br />

Dao’an<br />

Tanya Storch<br />

Daoism and <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

Stephen R. Bokenkamp<br />

Daosheng<br />

Mark L. Blum<br />

Daoxuan<br />

John Kieschnick<br />

Daoyi (Mazu)<br />

Mario Poceski<br />

Death<br />

Mark L. Blum<br />

Decline <strong>of</strong> the Dharma<br />

Jan Nattier<br />

Deqing<br />

William Chu<br />

Desire<br />

Luis O. Gómez<br />

xii E NCYCLOPEDIA OF B UDDHISM

L IST OF A RTICLES<br />

Devadatta<br />

Max Deeg<br />

Dge lugs (Geluk)<br />

Georges B. J. Dreyfus<br />

Dhammapada<br />

Oskar von Hinüber<br />

Dharanl <br />

Richard D. McBride II<br />

Dharma and Dharmas<br />

Charles Willemen<br />

Dharmadhatu<br />

Chi-chiang Huang<br />

Dharmaguptaka<br />

Collett Cox<br />

Dharmakl rti<br />

John Dunne<br />

Dharmaraksa<br />

Daniel Boucher<br />

Dhyana (Trance State)<br />

Karen Derris<br />

Diamond Sutra<br />

Gregory Schopen<br />

Diet<br />

James A. Benn<br />

Dignaga<br />

John Dunne<br />

Dl pam kara<br />

Jan Nattier<br />

Disciples <strong>of</strong> the Buddha<br />

Andrew Skilton<br />

Divinities<br />

Jacob N. Kinnard<br />

Divyavadana<br />

Joel Tatelman<br />

Dogen<br />

Carl Bielefeldt<br />

Dokyo<br />

Allan G. Grapard<br />

Doubt<br />

<strong>Robert</strong> E. <strong>Buswell</strong>, Jr.<br />

Dreams<br />

Alexander L. Mayer<br />

Duhkha (Suffering)<br />

Carol S. Anderson<br />

Dunhuang<br />

Roderick Whitfield<br />

Economics<br />

Gustavo Benavides<br />

Education<br />

Mahinda Deegalle<br />

Engaged <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

Christopher S. Queen<br />

Ennin<br />

David L. Gardiner<br />

Entertainment and Performance<br />

Victor H. Mair<br />

Esoteric Art, East Asia<br />

Cynthea J. Bogel<br />

Esoteric Art, South and Southeast<br />

Asia<br />

Gail Maxwell<br />

Ethics<br />

Barbara E. Reed<br />

Etiquette<br />

Eric Reinders<br />

Europe<br />

Martin Baumann<br />

Evil<br />

Maria Heim<br />

Exoteric-Esoteric (Kenmitsu)<br />

<strong>Buddhism</strong> in Japan<br />

James C. Dobbins<br />

Faith<br />

Luis O. Gómez<br />

Famensi<br />

Roderick Whitfield<br />

Family, <strong>Buddhism</strong> and the<br />

Alan Cole<br />

Fanwang jing (Brahma’s Net Sutra)<br />

Eunsu Cho<br />

Faxian<br />

Alexander L. Mayer<br />

Faxiang School<br />

Dan Lusthaus<br />

Fazang<br />

Jeffrey Broughton<br />

Festivals and Calendrical Rituals<br />

Jonathan S. Walters<br />

Folk Religion: An Overview<br />

Stephen F. Teiser<br />

Folk Religion, China<br />

Philip Clart<br />

Folk Religion, Japan<br />

Ian Reader<br />

Folk Religion, Southeast Asia<br />

Michael R. Rhum<br />

Four Noble Truths<br />

Carol S. Anderson<br />

Gandharl , Buddhist Literature in<br />

Richard Salomon<br />

Ganjin<br />

William M. Bodiford<br />

Gavam pati<br />

François Lagirarde<br />

Gender<br />

Reiko Ohnuma<br />

Genshin<br />

James C. Dobbins<br />

Ghost Festival<br />

Stephen F. Teiser<br />

Ghosts and Spirits<br />

Peter Masefield<br />

Gyonen<br />

Mark L. Blum<br />

Hachiman<br />

Fabio Rambelli<br />

Hair<br />

Patrick Olivelle<br />

Hakuin Ekaku<br />

John Jorgensen<br />

Han Yongun<br />

Pori Park<br />

Heart Sutra<br />

John R. McRae<br />

Heavens<br />

Rupert Gethin<br />

Hells<br />

Stephen F. Teiser<br />

Hells, Images <strong>of</strong><br />

Karil J. Kucera<br />

Hermeneutics<br />

John Powers<br />

Himalayas, Buddhist Art in<br />

Roger Goepper<br />

E NCYCLOPEDIA OF B UDDHISM<br />

xiii

L IST OF A RTICLES<br />

Hl nayana<br />

John S. Strong<br />

Hinduism and <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

Johannes Bronkhorst<br />

History<br />

John C. Maraldo<br />

Honen<br />

James C. Dobbins<br />

Honji Suijaku<br />

Fabio Rambelli<br />

Horyuji and Todaiji<br />

Karen L. Brock<br />

Huayan Art<br />

Henrik H. Sørensen<br />

Huayan jing<br />

Mario Poceski<br />

Huayan School<br />

Mario Poceski<br />

Huineng<br />

John R. McRae<br />

Huiyuan<br />

Mark L. Blum<br />

Hyesim<br />

A. Charles Muller<br />

Hyujŏng<br />

Sungtaek Cho<br />

Icchantika<br />

<strong>Robert</strong> E. <strong>Buswell</strong>, Jr.<br />

Ikkyu<br />

Sarah Fremerman<br />

India<br />

Richard S. Cohen<br />

India, Buddhist Art in<br />

Gail Maxwell<br />

India, Northwest<br />

Jason Neelis<br />

India, South<br />

Anne E. Monius<br />

Indonesia and the Malay Peninsula<br />

<strong>Robert</strong> L. Brown<br />

Indonesia, Buddhist Art in<br />

John N. Miksic<br />

Indra<br />

Jacob N. Kinnard<br />

Ingen Ryuki<br />

A. W. Barber<br />

Initiation<br />

Ronald M. Davidson<br />

Inoue Enryo<br />

Richard M. Jaffe<br />

Intermediate States<br />

Bryan J. Cuevas<br />

Ippen Chishin<br />

William M. Bodiford<br />

Islam and <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

Johan Elverskog<br />

Jainism and <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

Paul Dundas<br />

Japan<br />

Carl Bielefeldt<br />

Japan, Buddhist Art in<br />

Karen L. Brock<br />

Japanese, Buddhist Influences on<br />

Vernacular Literature in<br />

<strong>Robert</strong> E. Morrell<br />

Japanese Royal Family and<br />

<strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

Brian O. Ruppert<br />

Jataka<br />

Reiko Ohnuma<br />

Jataka, Illustrations <strong>of</strong><br />

Leela Aditi Wood<br />

Jatakamala<br />

Peter Khoroche<br />

Jewels<br />

Brian O. Ruppert<br />

Jiun Onko<br />

Paul B. Watt<br />

Jo khang<br />

Andrew Quintman<br />

Juefan (Huihong)<br />

George A. Keyworth<br />

Kailaśa (Kailash)<br />

Andrew Quintman<br />

Kalacakra<br />

John Newman<br />

Kamakura <strong>Buddhism</strong>, Japan<br />

James C. Dobbins<br />

Karma (Action)<br />

Johannes Bronkhorst<br />

Karma pa<br />

Andrew Quintman<br />

Karuna (Compassion)<br />

Roger R. Jackson<br />

Khmer, Buddhist Literature in<br />

Anne Hansen<br />

Kihwa<br />

A. Charles Muller<br />

Kingship<br />

Pankaj N. Mohan<br />

Klong chen pa (Longchenpa)<br />

Jacob P. Dalton<br />

Koan<br />

Morten Schlütter<br />

Koben<br />

George J. Tanabe, Jr.<br />

Konjaku Monogatari<br />

William M. Bodiford<br />

Korea<br />

Hee-Sung Keel<br />

Korea, Buddhist Art in<br />

Youngsook Pak<br />

Korean, Buddhist Influences on<br />

Vernacular Literature in<br />

Jongmyung Kim<br />

Kuiji<br />

Alan Sponberg<br />

Kukai<br />

Ryuichi Abé<br />

Kumarajl va<br />

John R. McRae<br />

Kyŏnghŏ<br />

Henrik H. Sørensen<br />

Laity<br />

Helen Hardacre<br />

Lalitavistara<br />

John S. Strong<br />

Lama<br />

Alexander Gardner<br />

Language, Buddhist Philosophy <strong>of</strong><br />

Richard P. Hayes<br />

Languages<br />

Jens-Uwe Hartmann<br />

Laṅkavatara-sutra<br />

John Powers<br />

xiv E NCYCLOPEDIA OF B UDDHISM

L IST OF A RTICLES<br />

Laos<br />

Justin McDaniel<br />

Law and <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

Rebecca French<br />

Lineage<br />

Albert Welter<br />

Local Divinities and <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

Fabio Rambelli<br />

Logic<br />

John Dunne<br />

Longmen<br />

Dorothy Wong<br />

Lotus Sutra (Saddharmapundarl kasutra)<br />

Jacqueline I. Stone<br />

Madhyamaka School<br />

Karen Lang<br />

Ma gcig lab sgron (Machig<br />

Lapdön)<br />

Andrew Quintman<br />

Mahabodhi Temple<br />

Leela Aditi Wood<br />

Mahakaśyapa<br />

Max Deeg<br />

Mahamaudgalyayana<br />

Susanne Mrozik<br />

Mahamudra<br />

Andrew Quintman<br />

Mahaparinirvana-sutra<br />

John S. Strong<br />

Mahaprajapatl Gautaml <br />

Karma Lekshe Tsomo<br />

Mahasam ghika School<br />

Paul Harrison<br />

Mahasiddha<br />

Andrew Quintman<br />

Mahavastu<br />

John S. Strong<br />

Mahayana<br />

Gregory Schopen<br />

Mahayana Precepts in Japan<br />

Paul Groner<br />

Mahl śasaka<br />

Collett Cox<br />

Mainstream Buddhist Schools<br />

Collett Cox<br />

Maitreya<br />

Alan Sponberg<br />

Mandala<br />

Denise Patry Leidy<br />

Mantra<br />

Richard D. McBride II<br />

Mara<br />

Jacob N. Kinnard<br />

Mar pa (Marpa)<br />

Andrew Quintman<br />

Martial Arts<br />

William Powell<br />

Matrceta<br />

Peter Khoroche<br />

Medicine<br />

Kenneth G. Zysk<br />

Meditation<br />

Luis O. Gómez<br />

Meiji Buddhist Reform<br />

Richard M. Jaffe<br />

Merit and Merit-Making<br />

George J. Tanabe, Jr.<br />

Mijiao (Esoteric) School<br />

Henrik H. Sørensen<br />

Mi la ras pa (Milarepa)<br />

Andrew Quintman<br />

Milindapañha<br />

Peter Masefield<br />

Millenarianism and Millenarian<br />

Movements<br />

Thomas DuBois<br />

Mindfulness<br />

Johannes Bronkhorst<br />

Miracles<br />

John Kieschnick<br />

Mizuko Kuyo<br />

George J. Tanabe, Jr.<br />

Modernity and <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

Gustavo Benavides<br />

Mohe Zhiguan<br />

Brook Ziporyn<br />

Monastic Architecture<br />

Nancy Shatzman Steinhardt<br />

Monasticism<br />

Jeffrey Samuels<br />

Monastic Militias<br />

William M. Bodiford<br />

Mongolia<br />

Patricia Berger<br />

Monks<br />

John Kieschnick<br />

Mozhao Chan (Silent Illumination<br />

Chan)<br />

Morten Schlütter<br />

Mudra and Visual Imagery<br />

Denise Patry Leidy<br />

Mulasarvastivada-vinaya<br />

Gregory Schopen<br />

Murakami Sensho<br />

Richard M. Jaffe<br />

Myanmar<br />

Patrick A. Pranke<br />

Myanmar, Buddhist Art in<br />

Paul Strachan<br />

Nagarjuna<br />

Paul Williams<br />

Nara <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

George J. Tanabe, Jr.<br />

Naropa<br />

Andrew Quintman<br />

Nationalism and <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

Pori Park<br />

Nenbutsu (Chinese, Nianfo;<br />

Korean, Yŏmbul)<br />

James C. Dobbins<br />

Nepal<br />

Todd T. Lewis<br />

Newari, Buddhist Literature in<br />

Todd T. Lewis<br />

Nichiren<br />

Jacqueline I. Stone<br />

Nichiren School<br />

Jacqueline I. Stone<br />

Nine Mountains School <strong>of</strong> Sŏn<br />

Sungtaek Cho<br />

Nirvana<br />

Luis O. Gómez<br />

Nirvana Sutra<br />

Mark L. Blum<br />

Nuns<br />

Karma Lekshe Tsomo<br />

E NCYCLOPEDIA OF B UDDHISM<br />

xv

L IST OF A RTICLES<br />

Om mani padme hum<br />

Alexander Gardner<br />

Ordination<br />

John R. McRae<br />

Original Enlightenment (Hongaku)<br />

Jacqueline I. Stone<br />

Oxherding Pictures<br />

Steven Heine<br />

Padmasambhava<br />

Jacob P. Dalton<br />

Pali, Buddhist Literature in<br />

Oskar von Hinüber<br />

Panchen Lama<br />

Gareth Sparham<br />

Paramartha<br />

Daniel Boucher<br />

Paramita (Perfection)<br />

Leslie S. Kawamura<br />

Parish (Danka, Terauke) System in<br />

Japan<br />

Duncan Williams<br />

Paritta and Raksa Texts<br />

Justin McDaniel<br />

Path<br />

William Chu<br />

Persecutions<br />

Kate Crosby<br />

Philosophy<br />

Dale S. Wright<br />

Phoenix Hall (at the Byodoin)<br />

Karen L. Brock<br />

Pilgrimage<br />

Kevin Trainor<br />

Platform Sutra <strong>of</strong> the Sixth Patriarch<br />

(Liuzu tan jing)<br />

John R. McRae<br />

Poetry and <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

George A. Keyworth<br />

Politics and <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

Eric Reinders<br />

Portraiture<br />

Karen L. Brock<br />

Potala<br />

Andrew Quintman<br />

Prajña (Wisdom)<br />

Roger R. Jackson<br />

Prajñaparamita Literature<br />

Lewis Lancaster<br />

Pratimoksa<br />

Karma Lekshe Tsomo<br />

Pratl tyasamutpada (Dependent<br />

Origination)<br />

Mathieu Boisvert<br />

Pratyekabuddha<br />

Ria Kloppenborg<br />

Pratyutpannasamadhi-sutra<br />

Paul Harrison<br />

Prayer<br />

José Ignacio Cabezón<br />

Precepts<br />

Daniel A. Getz<br />

Printing Technologies<br />

Richard D. McBride II<br />

Provincial Temple System<br />

(Kokubunji, Rishoto)<br />

Suzanne Gay<br />

Psychology<br />

Luis O. Gómez<br />

Pudgalavada<br />

Leonard C. D. C. Priestley<br />

Pure Land Art<br />

Eugene Y. Wang<br />

Pure Land <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

Daniel A. Getz<br />

Pure Lands<br />

Luis O. Gómez<br />

Pure Land Schools<br />

A. W. Barber<br />

Rahula<br />

Bhikkhu Pasadika<br />

Realms <strong>of</strong> Existence<br />

Rupert Gethin<br />

Rebirth<br />

Bryan J. Cuevas<br />

Refuges<br />

John Clifford Holt<br />

Relics And Relics Cults<br />

Brian O. Ruppert<br />

Reliquary<br />

Roderick Whitfield<br />

Rennyo<br />

James C. Dobbins<br />

Renwang jing (Humane Kings<br />

Sutra)<br />

A. Charles Muller<br />

Repentance and Confession<br />

David W. Chappell<br />

Ritual<br />

Richard K. Payne<br />

Ritual Objects<br />

Anne Nishimura Morse<br />

Rnying ma (Nyingma)<br />

Jacob P. Dalton<br />

Robes and Clothing<br />

Willa Jane Tanabe<br />

Ryokan<br />

David E. Riggs<br />

Saicho<br />

David L. Gardiner<br />

Sam dhinirmocana-sutra<br />

John Powers<br />

Samguk yusa (Memorabilia <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Three Kingdoms)<br />

Richard D. McBride II<br />

Sam sara<br />

Bryan J. Cuevas<br />

Sañcl <br />

Leela Aditi Wood<br />

Saṅgha<br />

Gareth Sparham<br />

Sanjie Jiao (Three Stages School)<br />

Jamie Hubbard<br />

Sanskrit, Buddhist Literature in<br />

Andrew Skilton<br />

Śantideva<br />

Paul Williams<br />

Śariputra<br />

Susanne Mrozik<br />

Sarvastivada and Mulasarvastivada<br />

Collett Cox<br />

Sa skya (Sakya)<br />

Cyrus Stearns<br />

Sa skya Pandita (Sakya Pandita)<br />

Ronald M. Davidson<br />

Satipatthana-sutta<br />

Patrick A. Pranke<br />

Satori (Awakening)<br />

<strong>Robert</strong> M. Gimello<br />

xvi E NCYCLOPEDIA OF B UDDHISM

L IST OF A RTICLES<br />

Sautrantika<br />

Collett Cox<br />

Scripture<br />

José Ignacio Cabezón<br />

Self-Immolation<br />

James A. Benn<br />

Sengzhao<br />

Tanya Storch<br />

Sentient Beings<br />

Daniel A. Getz<br />

Sexuality<br />

Hank Glassman<br />

Shingon <strong>Buddhism</strong>, Japan<br />

Ryuichi Abé<br />

Shinran<br />

James C. Dobbins<br />

Shinto (Honji Suijaku) and<br />

<strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

Fabio Rambelli<br />

Shobogenzo<br />

Carl Bielefeldt<br />

Shotoku, Prince (Taishi)<br />

William M. Bodiford<br />

Shugendo<br />

Paul L. Swanson<br />

Shwedagon<br />

Paul Strachan<br />

Śiksananda<br />

Chi-chiang Huang<br />

Silk Road<br />

Jason Neelis<br />

Sinhala, Buddhist Literature in<br />

Ranjini Obeyesekere<br />

Skandha (Aggregate)<br />

Mathieu Boisvert<br />

Slavery<br />

Jonathan A. Silk<br />

Soka Gakkai<br />

Jacqueline I. Stone<br />

Sŏkkuram<br />

Junghee Lee<br />

Soteriology<br />

Dan Cozort<br />

Southeast Asia, Buddhist Art in<br />

<strong>Robert</strong> L. Brown<br />

Space, Sacred<br />

Allan G. Grapard<br />

Sri Lanka<br />

John Clifford Holt<br />

Sri Lanka, Buddhist Art in<br />

Benille Priyanka<br />

Stupa<br />

A. L. Dallapiccola<br />

Sukhavatl vyuha-sutra<br />

Mark L. Blum<br />

Sukhothai<br />

Pattaratorn Chirapravati<br />

Śunyata (Emptiness)<br />

Roger R. Jackson<br />

Sutra<br />

John S. Strong<br />

Sutra Illustrations<br />

Willa Jane Tanabe<br />

Suvarnaprabhasottama-sutra<br />

Natalie D. Gummer<br />

Suzuki, D. T.<br />

Richard M. Jaffe<br />

Syncretic Sects: Three Teachings<br />

Philip Clart<br />

Tachikawaryu<br />

Nobumi Iyanaga<br />

Taiwan<br />

Charles B. Jones<br />

Taixu<br />

Ding-hwa Hsieh<br />

Takuan Soho<br />

William M. Bodiford<br />

Tantra<br />

Ronald M. Davidson<br />

Charles D. Orzech<br />

Tathagata<br />

John S. Strong<br />

Tathagatagarbha<br />

William H. Grosnick<br />

Temple System in Japan<br />

Duncan Williams<br />

Thai, Buddhist Literature in<br />

Grant A. Olson<br />

Thailand<br />

Donald K. Swearer<br />

Theravada<br />

Kate Crosby<br />

Theravada Art and Architecture<br />

Bonnie Brereton<br />

Thich Nhat Hanh<br />

Christopher S. Queen<br />

Tiantai School<br />

Brook Ziporyn<br />

Tibet<br />

Ronald M. Davidson<br />

Tibetan Book <strong>of</strong> the Dead<br />

Bryan J. Cuevas<br />

Tominaga Nakamoto<br />

Paul B. Watt<br />

Tsong kha pa<br />

Georges B. J. Dreyfus<br />

Ŭich’ŏn<br />

Chi-chiang Huang<br />

Ŭisang<br />

Patrick R. Uhlmann<br />

United States<br />

Thomas A. Tweed<br />

Upagupta<br />

John S. Strong<br />

Upali<br />

Susanne Mrozik<br />

Upaya<br />

Roger R. Jackson<br />

Usury<br />

Jamie Hubbard<br />

Vajrayana<br />

Ronald M. Davidson<br />

Vam sa<br />

Stephen C. Berkwitz<br />

Vasubandhu<br />

Dan Lusthaus<br />

Vidyadhara<br />

Patrick A. Pranke<br />

Vietnam<br />

Cuong Tu Nguyen<br />

Vietnamese, Buddhist Influences on<br />

Literature in<br />

Cuong Tu Nguyen<br />

Vijñanavada<br />

Dan Lusthaus<br />

E NCYCLOPEDIA OF B UDDHISM<br />

xvii

L IST OF A RTICLES<br />

Vimalakl rti<br />

Andrew Skilton<br />

Vinaya<br />

Gregory Schopen<br />

Vipassana (Sanskrit, Vipaśyana)<br />

Patrick A. Pranke<br />

Vipaśyin<br />

Jan Nattier<br />

Visnu<br />

Jacob N. Kinnard<br />

Viśvantara<br />

Reiko Ohnuma<br />

War<br />

Michael Zimmermann<br />

Wilderness Monks<br />

Thanissaro Bhikkhu (Ge<strong>of</strong>frey<br />

DeGraff)<br />

Women<br />

Natalie D. Gummer<br />

Wŏnbulgyo<br />

Bongkil Chung<br />

Wŏnch’ŭk<br />

Eunsu Cho<br />

Wŏnhyo<br />

Eunsu Cho<br />

Worship<br />

Jacob N. Kinnard<br />

Xuanzang<br />

Alexander L. Mayer<br />

Yaksa<br />

Jacob N. Kinnard<br />

Yanshou<br />

Albert Welter<br />

Yijing<br />

Alexander L. Mayer<br />

Yinshun<br />

William Chu<br />

Yixuan<br />

Urs App<br />

Yogacara School<br />

Dan Lusthaus<br />

Yujŏng<br />

Sungtaek Cho<br />

Yun’gang<br />

Dorothy Wong<br />

Zanning<br />

Albert Welter<br />

Zen, Popular Conceptions <strong>of</strong><br />

Juhn Ahn<br />

Zhanran<br />

Linda Penkower<br />

Zhao lun<br />

Tanya Storch<br />

Zhili<br />

Brook Ziporyn<br />

Zhiyi<br />

Brook Ziporyn<br />

Zhuhong<br />

William Chu<br />

Zonggao<br />

Ding-hwa Hsieh<br />

Zongmi<br />

Jeffrey Broughton<br />

xviii E NCYCLOPEDIA OF B UDDHISM

LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS<br />

Ryuichi Abé<br />

Columbia University<br />

Kukai<br />

Shingon <strong>Buddhism</strong>, Japan<br />

Juhn Ahn<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Michigan<br />

Zen, Popular Conceptions <strong>of</strong><br />

Carol S. Anderson<br />

Kalamazoo College<br />

Anitya (Impermanence)<br />

Duhkha (Suffering)<br />

Four Noble Truths<br />

Urs App<br />

University Media Research, Kyoto,<br />

Japan<br />

Yixuan<br />

A. W. Barber<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Calgary<br />

Ingen Ryuki<br />

Pure Land Schools<br />

Martin Baumann<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Lucerne, Switzerland<br />

Europe<br />

Heinz Bechert<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Göttingen<br />

Buddha, Life <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Gustavo Benavides<br />

Villanova University<br />

Economics<br />

Modernity and <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

James A. Benn<br />

Arizona State University<br />

Diet<br />

Self-Immolation<br />

Patricia Berger<br />

University <strong>of</strong> California, Berkeley<br />

Mongolia<br />

Stephen C. Berkwitz<br />

Southwest Missouri State University<br />

Vam sa<br />

Carl Bielefeldt<br />

Stanford University<br />

Dogen<br />

Japan<br />

Shobogenzo<br />

Mark L. Blum<br />

State University <strong>of</strong> New York, Albany<br />

Daosheng<br />

Death<br />

Gyonen<br />

Huiyuan<br />

Nirvana Sutra<br />

Sukhavatlvyuha-sutra<br />

William M. Bodiford<br />

University <strong>of</strong> California, Los Angeles<br />

Anuttarasamyaksam bodhi<br />

(Complete, Perfect Awakening)<br />

Ganjin<br />

Ippen Chishin<br />

Konjaku monogatari<br />

Monastic Militias<br />

Shotoku, Prince (Taishi)<br />

Takuan Soho<br />

Cynthea J. Bogel<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Washington<br />

Esoteric Art, East Asia<br />

Mathieu Boisvert<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Quebec at Montreal<br />

Pratltyasamutpada (Dependent<br />

Origination)<br />

Skandha (Aggregate)<br />

Stephen R. Bokenkamp<br />

Indiana University<br />

Daoism and <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

George D. Bond<br />

Northwestern University<br />

Anagarika Dharmapala<br />

Arhat<br />

Buddhavacana (Word <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Buddha)<br />

Daniel Boucher<br />

Cornell University<br />

Dharmaraksa<br />

Paramartha<br />

Bonnie Brereton<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Michigan<br />

Theravada Art and Architecture<br />

Karen L. Brock<br />

Albuquerque, New Mexico<br />

Daitokuji<br />

Horyuji and Todaiji<br />

Japan, Buddhist Art in<br />

Phoenix Hall (at the Byodoin)<br />

Portraiture<br />

Johannes Bronkhorst<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Lausanne, Switzerland<br />

Hinduism and <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

Karma (Action)<br />

Mindfulness<br />

Jeffrey Broughton<br />

California State University, Long<br />

Beach<br />

Bodhidharma<br />

Fazang<br />

Zongmi<br />

xix

L IST OF C ONTRIBUTORS<br />

<strong>Robert</strong> L. Brown<br />

University <strong>of</strong> California, Los Angeles<br />

Los Angeles County Museum <strong>of</strong> Art<br />

Buddha Images<br />

Indonesia and the Malay Peninsula<br />

Southeast Asia, Buddhist Art in<br />

<strong>Robert</strong> E. <strong>Buswell</strong>, Jr.<br />

University <strong>of</strong> California, Los Angeles<br />

Doubt<br />

Icchantika<br />

José Ignacio Cabezón<br />

University <strong>of</strong> California, Santa<br />

Barbara<br />

Prayer<br />

Scripture<br />

Jason A. Carbine<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Chicago<br />

Burmese, Buddhist Literature in<br />

David W. Chappell<br />

Soka University <strong>of</strong> America<br />

Repentance and Confession<br />

Pattaratorn Chirapravati<br />

California State University,<br />

Sacramento<br />

Ayutthaya<br />

Sukhothai<br />

Eunsu Cho<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Michigan<br />

Fanwang jing (Brahma’s Net<br />

Sutra)<br />

Wŏnch’ŭk<br />

Wŏnhyo<br />

Sungtaek Cho<br />

Korea University<br />

Hyujŏng<br />

Nine Mountains School <strong>of</strong> Sŏn<br />

Yujŏng<br />

William Chu<br />

University <strong>of</strong> California, Los Angeles<br />

Deqing<br />

Path<br />

Yinshun<br />

Zhuhong<br />

Bongkil Chung<br />

Florida International University<br />

Wŏnbulgyo<br />

Philip Clart<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Missouri–Columbia<br />

Folk Religion, China<br />

Syncretic Sects: Three Teachings<br />

Richard S. Cohen<br />

University <strong>of</strong> California, San Diego<br />

India<br />

Alan Cole<br />

Lewis and Clark College<br />

Family, <strong>Buddhism</strong> and the<br />

Collett Cox<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Washington<br />

Abhidharma<br />

Abhidharmakośabhasya<br />

Dharmaguptaka<br />

Mahlśasaka<br />

Mainstream Buddhist Schools<br />

Sarvastivada and<br />

Mulasarvastivada<br />

Sautrantika<br />

Dan Cozort<br />

Dickinson College<br />

Soteriology<br />

Kate Crosby<br />

University <strong>of</strong> London, United<br />

Kingdom<br />

Persecutions<br />

Theravada<br />

Bryan J. Cuevas<br />

Florida State University<br />

Intermediate States<br />

Rebirth<br />

Sam sara<br />

Tibetan Book <strong>of</strong> the Dead<br />

A. L. Dallapiccola<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Edinburgh, United<br />

Kingdom<br />

Stupa<br />

Jacob P. Dalton<br />

International Dunhuang Project,<br />

British Library<br />

Bsam yas (Samye)<br />

Bsam yas Debate<br />

D akinl<br />

Klong chen pa (Longchenpa)<br />

Padmasambhava<br />

Rnying ma (Nyingma)<br />

Ronald M. Davidson<br />

Fairfield University<br />

Initiation<br />

Sa skya Pandita (Sakya Pandita)<br />

Tantra<br />

Tibet<br />

Vajrayana<br />

Max Deeg<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Vienna, Austria<br />

Devadatta<br />

Mahakaśyapa<br />

Mahinda Deegalle<br />

Bath Spa University College, United<br />

Kingdom<br />

Education<br />

Karen Derris<br />

Harvard University<br />

Dhyana (Trance State)<br />

James C. Dobbins<br />

Oberlin College<br />

Exoteric-Esoteric (Kenmitsu)<br />

<strong>Buddhism</strong> in Japan<br />

Genshin<br />

Honen<br />

Kamakura <strong>Buddhism</strong>, Japan<br />

Nenbutsu (Chinese, Nianfo;<br />

Korean, Yŏmbul)<br />

Rennyo<br />

Shinran<br />

Georges B. J. Dreyfus<br />

Williams College<br />

Dge lugs (Geluk)<br />

Tsong kha pa<br />

Thomas DuBois<br />

National University <strong>of</strong> Singapore<br />

Millenarianism and Millenarian<br />

Movements<br />

Paul Dundas<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Edinburgh, United<br />

Kingdom<br />

Jainism and <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

John Dunne<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Wisconsin, Madison<br />

Dharmaklrti<br />

Dignaga<br />

Logic<br />

Johan Elverskog<br />

Southern Methodist University<br />

Islam and <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

Sarah Fremerman<br />

Stanford University<br />

Ikkyu<br />

Rebecca French<br />

State University <strong>of</strong> New York, Buffalo<br />

Law and <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

David L. Gardiner<br />

Colorado College<br />

Ennin<br />

Saicho<br />

xx E NCYCLOPEDIA OF B UDDHISM

L IST OF C ONTRIBUTORS<br />

Alexander Gardner<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Michigan<br />

Lama<br />

Om mani padme hum<br />

Suzanne Gay<br />

Oberlin College<br />

Provincial Temple System<br />

(Kokubunji, Rishoto)<br />

Rupert Gethin<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Bristol, United Kingdom<br />

Cosmology<br />

Heavens<br />

Realms <strong>of</strong> Existence<br />

Daniel A. Getz<br />

Bradley University<br />

Precepts<br />

Pure Land <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

Sentient Beings<br />

<strong>Robert</strong> M. Gimello<br />

Harvard University<br />

Bodhi (Awakening)<br />

Satori (Awakening)<br />

Hank Glassman<br />

Haverford College<br />

Sexuality<br />

Roger Goepper<br />

Cologne Museum, Germany<br />

Alchi<br />

Himalayas, Buddhist Art in<br />

Luis O. Gómez<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Michigan<br />

Amitabha<br />

Bodhicitta (Thought <strong>of</strong> Awakening)<br />

Desire<br />

Faith<br />

Meditation<br />

Nirvana<br />

Psychology<br />

Pure Lands<br />

Allan G. Grapard<br />

University <strong>of</strong> California, Santa<br />

Barbara<br />

Dokyo<br />

Space, Sacred<br />

Paul Groner<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Virginia<br />

Mahayana Precepts in Japan<br />

William H. Grosnick<br />

La Salle University<br />

Tathagatagarbha<br />

Natalie D. Gummer<br />

Beloit College<br />

Suvarnaprabhasottama-sutra<br />

Women<br />

Anne Hansen<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Wisconsin, Milwaukee<br />

Cambodia<br />

Khmer, Buddhist Literature in<br />

Helen Hardacre<br />

Harvard University<br />

Laity<br />

Paul Harrison<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Canterbury, New<br />

Zealand<br />

An Shigao<br />

Buddhanusmrti (Recollection <strong>of</strong><br />

the Buddha)<br />

Canon<br />

Mahasam ghika School<br />

Pratyutpannasamadhi-sutra<br />

Jens-Uwe Hartmann<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Munich, Germany<br />

A gama/Nikaya<br />

Languages<br />

Richard P. Hayes<br />

University <strong>of</strong> New Mexico<br />

Language, Buddhist Philosophy <strong>of</strong><br />

Maria Heim<br />

California State University, Long<br />

Beach<br />

Dana (Giving)<br />

Evil<br />

Steven Heine<br />

Florida International University<br />

Oxherding Pictures<br />

James W. Heisig<br />

Nanzan Institute for Religion and<br />

Culture, Nanzan University, Japan<br />

Christianity and <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

John Clifford Holt<br />

Bowdoin College<br />

Refuges<br />

Sri Lanka<br />

Ding-hwa Hsieh<br />

Truman State University<br />

Awakening <strong>of</strong> Faith (Dasheng qixin<br />

lun)<br />

Taixu<br />

Zonggao<br />

Chi-chiang Huang<br />

Hobart and William Smith Colleges<br />

Dharmadhatu<br />

Śiksananda<br />

Ŭich’ŏn<br />

Jamie Hubbard<br />

Smith College<br />

Critical <strong>Buddhism</strong> (Hihan Bukkyo)<br />

Sanjie Jiao (Three Stages School)<br />

Usury<br />

Nobumi Iyanaga<br />

Tokyo, Japan<br />

Tachikawaryu<br />

Roger R. Jackson<br />

Carleton College<br />

Candraklrti<br />

Karuna (Compassion)<br />

Prajña (Wisdom)<br />

Śunyata (Emptiness)<br />

Upaya<br />

Richard M. Jaffe<br />

Duke University<br />

Clerical Marriage in Japan<br />

Inoue Enryo<br />

Meiji Buddhist Reform<br />

Murakami Sensho<br />

Suzuki, D. T.<br />

Charles B. Jones<br />

The Catholic University <strong>of</strong> America<br />

Taiwan<br />

John Jorgensen<br />

Griffith University, Australia<br />

Chan School<br />

Hakuin Ekaku<br />

Leslie S. Kawamura<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Calgary<br />

Bodhisattva(s)<br />

Paramita (Perfection)<br />

Hee-Sung Keel<br />

Sogang University, South Korea<br />

Korea<br />

John P. Keenan<br />

Middlebury College<br />

Asaṅga<br />

Richard K. Kent<br />

Franklin and Marshall College<br />

Arhat Images<br />

George A. Keyworth<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Colorado<br />

Confucianism and <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

Juefan (Huihong)<br />

Poetry and <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

E NCYCLOPEDIA OF B UDDHISM<br />

xxi

L IST OF C ONTRIBUTORS<br />

Peter Khoroche<br />

Cambridge, United Kingdom<br />

A ryaśura<br />

Aśvaghosa<br />

Jatakamala<br />

Matrceta<br />

John Kieschnick<br />

Institute <strong>of</strong> History and Philology,<br />

Academia Sinica, Taiwan<br />

Biographies <strong>of</strong> Eminent Monks<br />

(Gaoseng zhuan)<br />

Daoxuan<br />

Miracles<br />

Monks<br />

Jongmyung Kim<br />

Youngsan University, South Korea<br />

Chogye School<br />

Korean, Buddhist Influences on<br />

Vernacular Literature in<br />

Richard King<br />

Liverpool Hope University College,<br />

United Kingdom<br />

Colonialism and <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

Jacob N. Kinnard<br />

College <strong>of</strong> William and Mary<br />

Divinities<br />

Indra<br />

Mara<br />

Visnu<br />

Worship<br />

Yaksa<br />

Ria Kloppenborg<br />

Utrecht University, Netherlands<br />

Pratyekabuddha<br />

Karil J. Kucera<br />

St. Olaf College<br />

Bamiyan<br />

Hells, Images <strong>of</strong><br />

Charles Lachman<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Oregon<br />

Bodhisattva Images<br />

Chan Art<br />

François Lagirarde<br />

Ecole Française d’Extrême-Orient,<br />

Bangkok, Thailand<br />

Gavam pati<br />

Lewis Lancaster<br />

University <strong>of</strong> California, Berkeley<br />

Prajñaparamita Literature<br />

Karen Lang<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Virginia<br />

A ryadeva<br />

Madhyamaka School<br />

Junghee Lee<br />

Portland State University<br />

Sŏkkuram<br />

Denise Patry Leidy<br />

Metropolitan Museum <strong>of</strong> Art, New<br />

York<br />

Cave Sanctuaries<br />

Mandala<br />

Mudra and Visual Imagery<br />

Todd T. Lewis<br />

College <strong>of</strong> the Holy Cross<br />

Nepal<br />

Newari, Buddhist Literature in<br />

Dan Lusthaus<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Missouri–Columbia<br />

Faxiang School<br />

Vasubandhu<br />

Vijñanavada<br />

Yogacara School<br />

Victor H. Mair<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Pennsylvania<br />

Bianwen<br />

Bianxiang (Transformation<br />

Tableaux)<br />

Chinese, Buddhist Influences on<br />

Vernacular Literature in<br />

Entertainment and Performance<br />

John J. Makransky<br />

Boston College<br />

Buddhahood and Buddha Bodies<br />

Eleanor Mannikka<br />

Indiana University <strong>of</strong> Pennsylvania<br />

Bayon<br />

John C. Maraldo<br />

University <strong>of</strong> North Florida<br />

History<br />

Peter Masefield<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Sydney, Australia<br />

Ghosts and Spirits<br />

Milindapañha<br />

Gail Maxwell<br />

Los Angeles County Museum <strong>of</strong> Art<br />

Buddha, Life <strong>of</strong> the, in Art<br />

Esoteric Art, South and Southeast<br />

Asia<br />

India, Buddhist Art in<br />

Alexander L. Mayer<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Illinois at Urbana-<br />

Champaign<br />

Commentarial Literature<br />

Dreams<br />

Faxian<br />

Xuanzang<br />

Yijing<br />

Richard D. McBride II<br />

The University <strong>of</strong> Iowa<br />

Dharanl<br />

Mantra<br />

Printing Technologies<br />

Samguk yusa (Memorabilia <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Three Kingdoms)<br />

Justin McDaniel<br />

Harvard University<br />

Laos<br />

Paritta and Raksa Texts<br />

John R. McRae<br />

Indiana University<br />

Heart Sutra<br />

Huineng<br />

Kumarajlva<br />

Ordination<br />

Platform Sutra <strong>of</strong> the Sixth<br />

Patriarch (Liuzu tan jing)<br />

John N. Miksic<br />

National University <strong>of</strong> Singapore<br />

Borobudur<br />

Indonesia, Buddhist Art in<br />

Pankaj N. Mohan<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Sydney, Australia<br />

Kingship<br />

Anne E. Monius<br />

Harvard University<br />

India, South<br />

<strong>Robert</strong> E. Morrell<br />

Washington University in St. Louis<br />

Japanese, Buddhist Influences on<br />

Vernacular Literature in<br />

Anne Nishimura Morse<br />

Museum <strong>of</strong> Fine Arts, Boston<br />

Ritual Objects<br />

Susanne Mrozik<br />

Western Michigan University<br />

Mahamaudgalyayana<br />

Śariputra<br />

Upali<br />

A. Charles Muller<br />

Toyo Gakuen University, Japan<br />

Hyesim<br />

Kihwa<br />

Renwang jing (Humane Kings<br />

Sutra)<br />

xxii E NCYCLOPEDIA OF B UDDHISM

L IST OF C ONTRIBUTORS<br />

Jan Nattier<br />

Indiana University<br />

Aksobhya<br />

Buddha(s)<br />

Central Asia<br />

Conversion<br />

Decline <strong>of</strong> the Dharma<br />

Dlpam kara<br />

Vipaśyin<br />

Jason Neelis<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Washington<br />

India, Northwest<br />

Silk Road<br />

John Newman<br />

New College <strong>of</strong> Florida<br />

Kalacakra<br />

Cuong Tu Nguyen<br />

George Mason University<br />

Vietnam<br />

Vietnamese, Buddhist Influences on<br />

Literature in<br />

Ranjini Obeyesekere<br />

Princeton University<br />

Sinhala, Buddhist Literature in<br />

Reiko Ohnuma<br />

Dartmouth College<br />

Gender<br />

Jataka<br />

Viśvantara<br />

Patrick Olivelle<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Texas at Austin<br />

Hair<br />

Grant A. Olson<br />

Northern Illinois University<br />

Thai, Buddhist Literature in<br />

Charles D. Orzech<br />

University <strong>of</strong> North Carolina,<br />

Greensboro<br />

Tantra<br />

Youngsook Pak<br />

University <strong>of</strong> London, United<br />

Kingdom<br />

Korea, Buddhist Art in<br />

Jin Y. Park<br />

American University<br />

Communism and <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

Pori Park<br />

Arizona State University<br />

Han Yongun<br />

Nationalism and <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

Sung Bae Park<br />

State University <strong>of</strong> New York at<br />

Stony Brook<br />

Chinul<br />

Bhikkhu Pasadika<br />

Philipps University, Marburg,<br />

Germany<br />

A nanda<br />

Rahula<br />

Richard K. Payne<br />

Institute <strong>of</strong> Buddhist Studies,<br />

Graduate Theological Union,<br />

Berkeley, California<br />

Ritual<br />

Linda Penkower<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Pittsburgh<br />

Zhanran<br />

Mario Poceski<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Florida<br />

Chengguan<br />

China<br />

Daoyi (Mazu)<br />

Huayan jing<br />

Huayan School<br />

William Powell<br />

University <strong>of</strong> California, Santa<br />

Barbara<br />

Martial Arts<br />

John Powers<br />

Australian National University,<br />

Australia<br />

Hermeneutics<br />

Laṅkavatara-sutra<br />

Sam dhinirmocana-sutra<br />

Patrick A. Pranke<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Michigan<br />

Abhijña (Higher Knowledges)<br />

Myanmar<br />

Satipatthana-sutta<br />

Vidyadhara<br />

Vipassana (Sanskrit, Vipaśyana)<br />

Charles S. Prebish<br />

The Pennsylvania State University<br />

Councils, Buddhist<br />

Leonard C. D. C. Priestley<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Toronto<br />

Pudgalavada<br />

Benille Priyanka<br />

University <strong>of</strong> California, Los Angeles<br />

Sri Lanka, Buddhist Art in<br />

Christopher S. Queen<br />

Harvard University<br />

Ambedkar, B. R.<br />

Buddhadasa<br />

Engaged <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

Thich Nhat Hanh<br />

Andrew Quintman<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Michigan<br />

Bka’ brgyud (Kagyu)<br />

Jo khang<br />

Kailaśa (Kailash)<br />

Karma pa<br />

Ma gcig lab sgron (Machig Lapdön)<br />

Mahamudra<br />

Mahasiddha<br />

Mar pa (Marpa)<br />

Mi la ras pa (Milarepa)<br />

Naropa<br />

Potala<br />

Fabio Rambelli<br />

Sapporo University, Japan<br />

Hachiman<br />

Honji Suijaku<br />

Local Divinities and <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

Shinto (Honji Suijaku) and<br />

<strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

Ian Reader<br />

Lancaster University, United Kingdom<br />

Folk Religion, Japan<br />

Barbara E. Reed<br />

St. Olaf College<br />

Ethics<br />

Eric Reinders<br />

Emory University<br />

Etiquette<br />

Politics and <strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

Marylin Martin Rhie<br />

Smith College<br />

China, Buddhist Art in<br />

Michael R. Rhum<br />

Chicago, Illinois<br />

Amulets and Talismans<br />

Folk Religion, Southeast Asia<br />

David E. Riggs<br />

University <strong>of</strong> California, Los Angeles<br />

Ryokan<br />

Brian O. Ruppert<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Illinois at Urbana-<br />

Champaign<br />

Japanese Royal Family and<br />

<strong>Buddhism</strong><br />

E NCYCLOPEDIA OF B UDDHISM<br />

xxiii

L IST OF C ONTRIBUTORS<br />

Jewels<br />

Relics And Relics Cults<br />

Richard Salomon<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Washington<br />

Gandharl, Buddhist Literature in<br />

Jeffrey Samuels<br />

Western Kentucky University<br />

Monasticism<br />

K. T. S. Sarao<br />

Chung-Hwa Institute <strong>of</strong> Buddhist<br />

Studies, Taiwan<br />

Anatman/Atman (No-Self/Self)<br />

Morten Schlütter<br />

Yale University<br />

Koan<br />

Mozhao Chan (Silent Illumination<br />

Chan)<br />

Juliane Schober<br />

Arizona State University<br />

Biography<br />

Gregory Schopen<br />

University <strong>of</strong> California, Los Angeles<br />

Diamond Sutra<br />

Mahayana<br />

Mulasarvastivada-vinaya<br />

Vinaya<br />

Jonathan A. Silk<br />

University <strong>of</strong> California, Los Angeles<br />

Buddhist Studies<br />

Slavery<br />

Andrew Skilton<br />

Cardiff University, United Kingdom<br />

Disciples <strong>of</strong> the Buddha<br />

Sanskrit, Buddhist Literature in<br />

Vimalaklrti<br />

Henrik H. Sørensen<br />

Seminar for Buddhist Studies,<br />