Remembering Bob Carter A GSNZ Tribute

GSNZ%20Newsletter%2019A%20July%202016

GSNZ%20Newsletter%2019A%20July%202016

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Remembering</strong> <strong>Bob</strong> <strong>Carter</strong>: A <strong>GSNZ</strong> <strong>Tribute</strong><br />

9 March 1942 – 19 January 2016<br />

Photo source: Anne <strong>Carter</strong><br />

Geoscience Society of New Zealand<br />

Newsletter 19A (Supplement) July 2016<br />

Compiler: Cam Nelson<br />

ISSN 1179-7983 (Print)<br />

ISSN 1179-7991 (Online)

<strong>Remembering</strong> <strong>Bob</strong> <strong>Carter</strong>: A Geoscience Society of NZ <strong>Tribute</strong><br />

Contents<br />

Page<br />

Introduction - Cam Nelson (Compiler) ………………………………………………….. 2<br />

<strong>Tribute</strong>s ...................................................................................................................... 4<br />

#1 Eulogy (24 January 2016) for <strong>Bob</strong> <strong>Carter</strong>, 1942-2016 - Bill Lindqvist 5<br />

#2 A supreme field geology mentor – Steve Abbott ............................... 8<br />

#3 Molluscan fossil collectors together – Alan Beu ……………………… 11<br />

#4 Temporarily being a petrophysicist - Greg Browne, Martin<br />

Crundwell , Craig Fulthorpe, Kathie Marsaglia ………………….…….. 13<br />

#5 A trilogy (A-C) of <strong>Bob</strong> <strong>Carter</strong> remembrances - Hamish Campbell …. 15<br />

#6 All at sea with <strong>Bob</strong> <strong>Carter</strong> - Lionel <strong>Carter</strong> .......................................... 20<br />

#7 Livening up geological discussions - Penny Cooke …………………. 21<br />

#8 A family of young academics - Alan Cooper ………………………….. 23<br />

#9 He sure made you think critically- Dave Craw ………………………... 24<br />

#10 He underpinned my career development - Barry Douglas ………….. 24<br />

#11 An influential Australasian ODP/IODP proponent - Neville Exon ...... 26<br />

#12 An insightful and inspirational geologist - Ewan Fordyce .................. 27<br />

#13 ‘Go-to’ person for A Continent on the Move - Ian Graham …………. 28<br />

#14 Two <strong>Bob</strong> <strong>Carter</strong> field stories - Bruce Hayward ……………………….. 29<br />

#15 An inspirational teacher and research mentor - Doug Haywick ……. 32<br />

#16 Evolution of JCU Marine Geophysics Laboratory - Mal Heron .......... 34<br />

#17 Tough field experiences - Fiona Hyden ............................................. 35<br />

#18 What a stimulating colleague - Chuck Landis ................................... 35<br />

#19 Spruce up your attire Piers! - Piers Larcombe .................................. 36<br />

#20 Bold ideas about New Zealand geology - Daphne Lee ..................... 38<br />

#21 Unstoppable, generous and legendary - Keith Lewis ……………….. 39<br />

#22 The wilds of Westland and Fiordland - Jon Lindqvist ……………….. 41<br />

#23 A masterful writer and editor - David Lowe …………………………… 42<br />

#24 ODP Leg 181 Co-Chiefs - Nick McCave …………………………….... 43<br />

#25 Partners in crime in Whanganui Basin - Tim Naish ........................... 45<br />

#26 Sailing with <strong>Bob</strong> - Helen Neil …………………………………………… 47<br />

#27 An exceptional sedimentary/marine geologist - Cam Nelson ………. 48<br />

#28 What a stimulating collaborator - Richard Norris …………………….. 50<br />

#29 Architect of JCU’s Marine Geophysics Laboratory - Alan Orpin …… 51<br />

#30 A quiet beer or two - Brad Pillans ...................................................... 52<br />

#31 The global warming issue - Ian Plimer ………………………………… 53<br />

#32 An incomparable teacher and communicator - John Rhodes ………. 56<br />

#33 Advancing Great Barrier Reef shelf sedimentology - Peter Ridd …... 57<br />

#34 ’Climate skeptics’ together - Gerrit van der Lingen ............................ 58<br />

Publications of <strong>Bob</strong> <strong>Carter</strong> – Cam Nelson ……………………………………………… 61<br />

Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………………………… 73<br />

Geoscience Society of New Zealand 1

Introduction<br />

Cam Nelson (Compiler)<br />

School of Science, University of Waikato<br />

Private Bag 3105, Hamilton, New Zealand 3240<br />

c.nelson@waikato.ac.nz<br />

New Zealand (NZ), Australian and many other geoscientists were saddened to learn<br />

of the sudden death of Professor Robert (<strong>Bob</strong>) M. <strong>Carter</strong> in Townsville on 19 January<br />

2016. During his long teaching and research career, based first at the University of<br />

Otago (Dunedin 1968-1980) and later at or associated with James Cook University<br />

(Townsville 1981-2013). Undeniably, <strong>Bob</strong> made significant contributions in advancing<br />

our knowledge and understanding of many aspects of the geosciences in New<br />

Zealand and the wider SW Pacific region, especially in the fields of paleontology and<br />

paleoecology, stratigraphy and paleoenvironments, marine geology and<br />

paleoceanography, and environmental and climate change science.<br />

<strong>Bob</strong> always maintained a very close association with the Geoscience Society of NZ<br />

(<strong>GSNZ</strong>), including as a long-time member and frequent annual conference attendee,<br />

as organiser and leader of several NZ field trips, through the supervision of many<br />

postgraduate research students on NZ projects, as a prolific publisher of peerreviewed<br />

papers on NZ geosciences, including being a major contributing author to<br />

the Society’s recent monograph A Continent on the Move, as the Society’s<br />

Hochstetter Lecturer in 1975, as an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of NZ since<br />

1997, and as a member/leader of 12 scientific research cruises in NZ waters,<br />

including notably as Co-Chief Scientist on ODP Leg 181 (Southwest Pacific<br />

Gateway) in 1998. In appreciation of these remarkable contributions to NZ and SW<br />

Pacific geosciences, and with my prompting, the Society approved the preparation of<br />

this special <strong>GSNZ</strong> Newsletter Supplement dedicated to <strong>Bob</strong> <strong>Carter</strong>.<br />

I agreed to act as the Compiler of the Supplement. Colleagues, students and friends<br />

of <strong>Bob</strong>, past and present, in NZ, Australia and elsewhere, were invited by email or<br />

advertisement [<strong>GSNZ</strong> Newsletter 18 (2016), p. 29] to submit some personal<br />

recollections about <strong>Bob</strong> for publication in the Supplement. By deadline, 34<br />

contributions had been received and, with typically only a small amount of editing to<br />

maintain some consistency in content, style and format, they follow this Introduction.<br />

Most will know that over the past decade or more <strong>Bob</strong> became heavily involved in<br />

researching and debating climate science issues, and he refused to accept the idea<br />

of any major influence by humans on global warming. His significant contributions in<br />

this regard are well documented on The Heartland Institute website which, following<br />

his death, also hosted many tributes for <strong>Bob</strong> from climate colleagues all over the<br />

world (see https://www.heartland.org/robert-m-carter). In comparison, the tributes<br />

appearing here for <strong>Bob</strong> focus more on his contributions to NZ, Australian (especially<br />

Great Barrier Reef shelf) and the wider Southwest Pacific geosciences field, but<br />

nevertheless do include some documenting his climate-related work.<br />

<strong>Bob</strong>’s CV and professional work history are already well documented online at<br />

http://members.iinet.net.au/~glrmc/new_page_3.htm, and again by Wikipedia at<br />

2 Issue 19A Supplement

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_M._<strong>Carter</strong>, where interested readers can get<br />

further specific information. Using these sources, as well as personal contacts, I have<br />

produced a biographical synopsis for <strong>Bob</strong> <strong>Carter</strong> in Table 1 that provides a summary<br />

background and context for several of the articles appearing in the Supplement.<br />

Table 1 - Biographical synopsis for <strong>Bob</strong> <strong>Carter</strong>.<br />

Full name<br />

Robert Merlin <strong>Carter</strong><br />

Born<br />

9 March 1942, Reading, England<br />

Died 19 January 2016, Townsville, Australia (aged 73)<br />

Usual first name <strong>Bob</strong><br />

Citizenship<br />

British, Australian<br />

Nationality<br />

English<br />

Emigration To New Zealand (NZ) in 1956; to Australia in 1981<br />

Secondary education Roysses Grammar School, Abingdon, UK (1952-1955)<br />

Lindisfarne College, Hastings, NZ (1956-1959)<br />

Married Anne Catherine (nee Verngreen) in 1964<br />

Children Susan (born 1969)<br />

Jeremy (born 1972)<br />

Degrees * BSc(Hons First Class) in Geology, Otago, NZ 1963<br />

* PhD in Paleontology, Cambridge, UK 1968<br />

PhD thesis The Functional Morphology of Bivalved Mollusca (1968)<br />

Main career positions * Assistant Lecturer, University of Otago, NZ (1963-1964)<br />

* PhD research, University of Cambridge, UK (1965-1967)<br />

* Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, University of Otago, NZ (1968-1980)<br />

* Professor/Head of Department of Geology, James Cook<br />

University, Townsville, Australia (1981-1999)<br />

* Adjunct Research Professor, Marine Geophysical Laboratory,<br />

James Cook University, Townsville, Australia (1999-2013)<br />

* Adjunct Research Professor, Geology & Geophysics, University<br />

of Adelaide, Australia (2000-2005)<br />

* Emeritus Fellow, Institute of Public Affairs (IPA, Melbourne)<br />

(2010-2013)<br />

Main research fields Cenozoic paleontology and paleoecology, stratigraphy and<br />

paleoenvironments, marine geology and paleoceanography, and<br />

sea-level and climate change science<br />

Research cruises >15, mainly in NZ and Queensland waters (e.g. Fig. 1)<br />

Some committee and * Member then Chair, Earth Sciences Discipline Panel of<br />

other positions Australian Research Council (ARC) (1987-1992)<br />

* Chair, Australian Marine Sciences and Technologies Advisory<br />

Committee (AMSTAC) (1996-?)<br />

* Director, Australian Office of the Ocean Drilling Program (ODP)<br />

(1995-1997)<br />

* Co-Chief Scientist, Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) Leg 181<br />

(Southwest Pacific Gateways) (1998)<br />

* Chief Science Advisor, International Climate Science Coalition<br />

(ICSC) (2007-2016)<br />

* Scientific Advisor, Science and Public Policy Institute,<br />

Washington (2007-2016)<br />

* Director, Australian Environment Fdn, Melbourne (2011-2015)<br />

* Expert witness and invited speaker on many occasions in several<br />

countries on geological and especially climate science issues<br />

Geoscience Society of New Zealand 3

Table 1 (Continued)<br />

Some awards<br />

Some Society<br />

memberships<br />

* Commonwealth Scholarship, British Council, University of<br />

Cambridge, UK (1964-1967)<br />

* Nuffield Fellow, University of Oxford, UK (1974)<br />

* Hochstetter Lecturer, Geological (now Geoscience) Society of<br />

New Zealand (1975)<br />

* Bennison Distinguished Overseas Lecturer, American<br />

Association of Petroleum Geologists (1992)<br />

* Honorary Fellow, Royal Society of New Zealand (1997)<br />

* Special Investigator Research Award, Australian Research<br />

Council (1998)<br />

* Outstanding Research Career, marine geology, <strong>GSNZ</strong> (2005)<br />

* Lifetime Achievement Award, Heartland Institute, USA (2015)<br />

* Geological (now Geoscience) Society of New Zealand (<strong>GSNZ</strong>)<br />

* Geological Society of Australia (GSA)<br />

* Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy (AusIMM)<br />

* Geological Society of America (GSA)<br />

* American Geophysical Union (AGU)<br />

* American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG)<br />

* Society of Sedimentary Geology (SEPM)<br />

* New Zealand Climate Science Coalition (NZCSC)<br />

Publications * 137 peer-reviewed scientific articles (1965-2015)<br />

* 2 books and 6 major reports on ‘climate change’ (since 2010)<br />

* Numerous conference presentations/abstracts (1965-2015)<br />

* 266 newspaper/popular articles (mainly since 2002)<br />

* 25 radio interviews (mainly since 2002)<br />

* 21 video presentations (mainly since 2002)<br />

Fig.1. <strong>Bob</strong> reviewing some core<br />

logs on the JOIDES Resolution<br />

IODP Expedition 317 off eastern<br />

South Island, New Zealand in<br />

late 2009. Photo source: William<br />

Crawford, IODP.<br />

<strong>Tribute</strong>s<br />

The following personal tributes for <strong>Bob</strong> <strong>Carter</strong> (#1 - #34) have been arranged in<br />

alphabetical order of the surnames of contributors, except that the eulogy given at<br />

<strong>Bob</strong>’s funeral by Bill Lindqvist, <strong>Bob</strong>’s brother-in-law, has been placed first as it covers<br />

many facets of <strong>Bob</strong>’s life.<br />

4 Issue 19A Supplement

#1 - Eulogy (24 January 2016) for <strong>Bob</strong> <strong>Carter</strong>, 1942-2016<br />

Bill Lindqvist (<strong>Bob</strong>’s brother-in-law)<br />

3 Cazadero Lane, Tiburon<br />

California 94920, USA<br />

william_lindqvist@yahoo.com<br />

I first met <strong>Bob</strong> some 53 years ago. The year was 1962. He was a 3 rd year honours<br />

geology student at Otago University in Dunedin, New Zealand, and I was doing 1 st<br />

year geology as part of a mining engineering degree.<br />

I soon got to know <strong>Bob</strong> quite well since, being one of the most dynamic and<br />

enthusiastic of the senior students, he was asked to assist the teaching staff on 1 st<br />

year geological field trips. One early memory is that <strong>Bob</strong>, in addition to his geological<br />

skills, was able to roll cigarettes with one hand while driving the departmental land<br />

rover with the other.<br />

It was obvious early on that <strong>Bob</strong> had a passion for fieldwork on soft rocks and fossils<br />

and this was a love that never left him.<br />

And talking of love, <strong>Bob</strong> began courting a beautiful young arts student from<br />

Invercargill with the name of Anne Verngreen. And as luck would have it and quite<br />

independently, I started courting an equally striking young science student with the<br />

name of Helen Verngreen – Anne’s younger sister.<br />

<strong>Bob</strong> and Anne graduated in 1963 and shortly thereafter married. A few months later<br />

they set off for England where <strong>Bob</strong>, with a Commonwealth Scholarship tucked in his<br />

pocket, started a PhD on Functional Studies of Bivalvia at Cambridge. Anne took a<br />

teaching job at the Bell School of Languages to help keep <strong>Bob</strong> in red wine.<br />

Meanwhile Helen and I graduated and also married and two years later we arrived in<br />

London where I started a PhD at Imperial College. It wasn’t long before we met up<br />

with the <strong>Carter</strong>s again.<br />

A deciding moment, or I should say deciding month, came along as the four of us<br />

embarked on a four week long camping trip to Scandinavia. Needless to say we all<br />

got along swimmingly and this experience cemented a close and valued friendship<br />

that has continued to this day.<br />

We have several memories of this trip and here is one. It was in a forest in southern<br />

Sweden infested with hordes of tiny biting flies known as ‘noseums’. <strong>Bob</strong> and I, being<br />

true gentlemen, retreated to the tents to smoke and drink beer in a valiant attempt to<br />

keep flies at bay – while the ladies stayed outside to cook dinner surrounded by<br />

clouds of the nipping insects. We never quite lived that down.<br />

After Cambridge, <strong>Bob</strong> and Anne returned to Otago University in Dunedin where <strong>Bob</strong><br />

was appointed to a lectureship in Geology, and in the years that followed two bright<br />

young children came along – first Susan and then Jeremy.<br />

Geoscience Society of New Zealand 5

And so our lives diverged once again. I became an exploration geologist in the<br />

mining industry, started work in the UK and in the early 1970s we moved to the USA.<br />

Along the way Helen and I also came up with two children in the same order – first a<br />

daughter and then a son.<br />

Over the decades that followed we shared many adventures and family gatherings<br />

with the <strong>Carter</strong>s – in New Zealand, Australia and the States, and on several<br />

occasions we had the three sisters – Anne, Helen and Clare - present with their<br />

families. <strong>Bob</strong> liked to refer to the sister trio as “The Three Graces” – which of course<br />

they all lapped up.<br />

During one visit by the <strong>Carter</strong>s to Denver, where we lived at the time, <strong>Bob</strong> and I<br />

spent an exciting day looking at the spectacular geology along the Front Range of<br />

the Rockies. But on the drive home we were stopped by the county sheriff amidst a<br />

flurry of sirens and flashing lights, ordered out at gun point and told to stand at the<br />

back of the car with our arms raised high while they searched the vehicle. Fifteen<br />

minutes later we were told to stand down since they had nabbed the bearded purse<br />

snatcher at the same quarry where we had looked at the rocks. Two innocent but<br />

frightened geologists breathed a sigh of relief and headed home for a stiff, single<br />

malt scotch.<br />

<strong>Bob</strong> was a great travelling companion and he was a huge fund of knowledge whether<br />

it be sports, arts, politics, science or gadgets. He and I had an easy going<br />

relationship and were frequently bragging and debating as to whom had the longer<br />

telephoto lens, whose binoculars were better, who was the better birder (he won<br />

hands down), pcs versus macs, who had the best single malts (I won that one) and<br />

other subjects that are not appropriate to mention here.<br />

He also liked to quip that I was the Economic Geologist while he had to settle for<br />

being the family Uneconomic Geologist.<br />

<strong>Bob</strong> had a very distinguished teaching career at Otago University (NZ) and later<br />

James Cook University (Queensland) which spanned some 35 years. And not<br />

surprisingly he left his mark for the better at both institutions.<br />

<strong>Bob</strong> always retained a passion for fieldwork but his own interests broadened and<br />

expanded with time especially into Marine Science. He participated in several<br />

scientific cruises both in New Zealand waters overlying the continental shelf with NZ<br />

based groups and in the southern Pacific with the big time Ocean Drilling Program<br />

research ships funded by the USA (e.g. Figs 1, 2).<br />

Over the last 15 years, as we all know, he has been increasingly involved with<br />

climate science and the climate record, both recent and historic, much to the chagrin<br />

of the believers and large segments of the academic community that preach free<br />

speech and tolerance but act otherwise.<br />

Whatever <strong>Bob</strong> tackled, he did so with gusto and focus and incredibly hard work – and<br />

he invariably excelled. But somehow he always made time for home projects<br />

including his recent marathon genealogy study covering all sides of the family.<br />

6 Issue 19A Supplement

Fig. 2. <strong>Bob</strong> and Xuan Ding sampling sediment core on IODP Expedition 317 of the<br />

JOIDES Resolution in 2009 off the Canterbury coast, New Zealand. Photo source:<br />

William Crawford of IODP.<br />

Fig. 3. <strong>Bob</strong> in field mode against a backdrop of Paleogene Red Bluff Tuff in northern<br />

Chatham Island, offshore eastern South Island, 2008. Photo source: Bill Lindqvist.<br />

However, without the dedicated help and support from his loving wife Anne, <strong>Bob</strong>’s<br />

endeavours may not have reached the heights we have witnessed. Anne often<br />

Geoscience Society of New Zealand 7

ecounts the many times she was on her hands and knees bagging and labelling<br />

fossil specimens in such exotic locations as vineyards in France, precipitous slopes<br />

in the Dolomite mountains in Italy and hot, dusty deserts in Turkey. Anne’s knees tell<br />

the story!<br />

Over his 50-year career of teaching, research, lecturing and academic leadership,<br />

<strong>Bob</strong> has travelled the world, often with Anne and their two children (when they were<br />

younger) by his side. He has studied, done field research and/or lectured in Australia<br />

and New Zealand (e.g. Fig. 3), the UK and most of Europe, North and southern<br />

Africa, parts of the Middle East and Asia (including Japan and China), Antarctica and<br />

across the USA and Canada. His scientific papers are almost endless and he wrote<br />

and had published two climate books to boot. What energy that man had!<br />

Not many of you may know that at the tender age of 21 he joined a scientific<br />

expedition to Pitcairn Island and was the first ever geologist to map that remote<br />

terrain. Rumor has it that he also acted as part-time cook on the island. That’s <strong>Bob</strong><br />

<strong>Carter</strong>!<br />

Over the years <strong>Bob</strong> has mentored hundreds of students, has been honoured with<br />

many awards and, judging by the avalanche of tributes that have come in following<br />

his death, he is renowned, respected and loved across the globe.<br />

Helen and I accompanied <strong>Bob</strong> and Anne to three International Climate Conferences<br />

in recent years where we witnessed first-hand <strong>Bob</strong>’s extraordinary reputation<br />

amongst his peers. At the Heartland Climate Conference in Washington DC in June<br />

2015 he received the prestigious Lifetime Achievement Award. That was quite an<br />

emotional evening for us all.<br />

To sum up, <strong>Bob</strong> has had a distinguished and very productive academic career,<br />

supported by Anne and family, and as our brother-in-law and long time friend and the<br />

uncle to our children, he has always been a stimulating companion and mentor. Our<br />

eight year old grandson likes to call <strong>Bob</strong> “Uncle Fossil”.<br />

His family, relatives and friends will all hugely miss <strong>Bob</strong>’s quick wit, the twinkle in his<br />

eye, his mischievous grin, his infectious laugh, his generosity and gentle nature, his<br />

sense of fairness and, above all, the sheer pleasure of his company.<br />

#2 - A supreme field geology mentor<br />

Steve Abbott<br />

Geoscience Australia<br />

GPO Box 378, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia<br />

steve.abbott@ga.gov.au<br />

My involvement with <strong>Bob</strong> began in 1987 at James Cook University (JCU) when I was<br />

a newly arrived student in search of a PhD project. I recall meeting a welcoming,<br />

although slightly officious, individual whose appearance (walk shorts, long socks and<br />

immaculately groomed beard) contrasted with the colourful tee shirt and jandals<br />

8 Issue 19A Supplement

world of the tropical JCU campus. On a number of occasions I was summonsed to<br />

<strong>Bob</strong>’s office with its distinctive décor (masonry block with a hint of Cambridge). There<br />

he could be found tapping away on his new 286 personal computer as if playing a<br />

piano accompaniment to the classical music playing in the background, replete with<br />

punctuational flourishes.<br />

I settled on my PhD project when <strong>Bob</strong> showed me cross-sections of the coastal<br />

Castlecliff section in Charles Fleming’s Bulletin 52 on the Whanganui Subdivision. At<br />

that point he sent me away with his copy of Bulletin 52, a copy of Menard’s Science:<br />

Growth and Change, and touch typing tutorial software. He more or less told me not<br />

to come back until I had mastered the latter! I arrived at JCU as <strong>Bob</strong> was developing<br />

a research programme on the sequence stratigraphy of the New Zealand Plio-<br />

Pleistocene and resuming his passion for New Zealand field geology.<br />

By the mid-1980s <strong>Bob</strong> recognised that the Plio-Pleistocene basins of New Zealand<br />

presented an opportunity to contribute to the rapidly developing sub-discipline of<br />

sequence stratigraphy. A prominent school of thought controversially asserted, in the<br />

absence of compelling evidence, that eustasy was the main control on sequence<br />

development. <strong>Bob</strong> would gleefully point out at every opportunity that Plio-Pleistocene<br />

strata provided a true test of sequence stratigraphic principles because, rather than<br />

assumed, the glacioeustatic control on strata of this age had been established<br />

independently from oxygen isotope studies of deep-sea cores.<br />

The research programme ran for about a decade and a half and was initially based<br />

around PhD projects in the Hawke’s Bay (Doug Haywick), Whanganui (Gordon Saul<br />

and I), and Wairarapa (Paul Gammon) basins. <strong>Bob</strong> enjoyed renewing his interaction<br />

with the New Zealand Geoscience community including Brad Pillans (stratigraphy),<br />

Alan Beu (molluscs and stratigraphy), Norcott Hornibrook (forams), and Ian Graham<br />

(Be isotope stratigraphy). Along the way there were numerous journal articles<br />

published as well as a Geological Society of NZ conference field trip, field<br />

workshops, a visit to JCU by ESSO Distinguished Lecturer Peter Vail (a co-inventor<br />

of sequence stratigraphy), <strong>Bob</strong>’s AAPG Distinguished Lecturer tour, and poster<br />

presentations at the 1996 AGU meeting in San Francisco. In the late 1990s Tim<br />

Naish (then a JCU Post-Doctoral Fellow), led the synthesis of the Whanganui Basin<br />

work that culminated in a series of papers that presented an integrated<br />

cyclostratigraphy for the basin. The New Zealand outcrop work conceived and<br />

overseen by <strong>Bob</strong> continues to be well cited in the sequence stratigraphic and<br />

Quaternary science literature.<br />

Some of my fond memories of <strong>Bob</strong> derive from my orientation tour of the Whanganui<br />

Basin. Our road trip around the Whanganui hinterland and Castlecliff coast included<br />

key geological sites from Bulletin 52 and a visit to <strong>Bob</strong>’s Honours field area in the<br />

Pohangina Valley. During our travels I received instruction on everything from<br />

terraces and lahars to the features of Maori Pa sites, all to the soundtrack of<br />

classical music from the car stereo. Book shops, bakeries, antique shops and corner<br />

shops called dairies, and a special type of sandwich called a “jammie”, rounded out<br />

my introduction to the New Zealand fieldwork experience.<br />

Geoscience Society of New Zealand 9

Fig. 4. <strong>Bob</strong> (white cap at top), while precariously perched, professing the<br />

paleoecological and sequence stratigraphic significance of the Tainui Shellbed,<br />

Castlecliff coast section, Whanganui, on a Geological Society of NZ field trip,<br />

November 1991. Photo source: Steve Abbott.<br />

Fig. 5. <strong>Bob</strong> pointing to the rootlet bed and erosion surface (NC11 sequence<br />

boundary) between the Middle Maxwell Formation and Mangahou Siltstone,<br />

Nukumaru coast section, Whanganui, 2003. Photo source: Steve Abbott.<br />

10 Issue 19A Supplement

During that orientation trip and subsequent fieldwork <strong>Bob</strong>’s endless enthusiasm for<br />

stratigraphy and fossils was always on display. He could hardly contain the<br />

excitement of scrutinising the ecosystem of a shellbed (Fig. 4), documenting a<br />

sequence bounding unconformity (Fig. 5), liberating a delicate Poirieria with all of its<br />

spines intact, or diagnosing a beach environment of deposition from a bed of<br />

Paphies to the refrain of “because that is where it lives today on the beach behind<br />

you!”<br />

<strong>Bob</strong>’s formal university persona melted away in the field to reveal his warm soul and<br />

(at times disconcertingly wicked) sense of humour. He was a generous mentor who<br />

not only guided his students through the various stages of their studies, but taught us<br />

by example the powers of observation and critical thought (including in his role as a<br />

peerless devil’s advocate). It is satisfying to reflect on how we produced such an<br />

important contribution to sequence stratigraphy based on careful field observations<br />

recorded with a pencil, notebook, and camera (actually two 35 mm SLR cameras,<br />

one for colour slides and the other for black and white prints).<br />

#3 - Molluscan fossil collectors together<br />

Alan Beu<br />

GNS Science<br />

PO Box 30368, Lower Hutt, New Zealand 5040<br />

a.beu@gns.cri.nz<br />

My first memory of <strong>Bob</strong> was a long time ago – in January 1963. While starting a<br />

degree at Victoria University, Wellington, I worked as Professor <strong>Bob</strong> Clark’s “lab boy”<br />

in the Geology Department, with the grand salary of £300 per year, and felt flush<br />

enough to buy a little Morris Minor. Over the Christmas holidays Graeme Wilson and<br />

I set off to collect fossils around much of the North Island. At Te Piki – with very<br />

diverse Haweran molluscs in a cutting on the road between Waihau Bay and Hicks<br />

Bay, East Cape – I was happily collecting molluscs and Graeme was collecting the<br />

dinoflagellate samples that allowed him to become an early expert in the group. Up<br />

rattled a tiny Morris 8, and out got a chap who introduced himself as <strong>Bob</strong> <strong>Carter</strong>. He<br />

was working for Charles Fleming in Paleontology, NZ Geological Survey, over the<br />

university recess, and decided to visit the remote Te Piki locality while he was up in<br />

the North Island. He was dismayed to see us there before him, assumed all the<br />

useful fossils had been collected, shared a beer or two, and then drove on. It was the<br />

beginning of a long but very friendly philosophical tussle between <strong>Bob</strong> and me about<br />

the interpretation of fossils, whether we need New Zealand stages, how stages<br />

should be defined, and so on, throughout the rest of our careers.<br />

Much later <strong>Bob</strong> introduced us all in GNS Science to the power of sequence<br />

stratigraphy and the poverty of the “global sea-level curve”, in a course he held (with<br />

the aid of some of his students such as Steve Abbott) in a rough little motel near the<br />

beach at the north end of Castlecliff, Whanganui, handy to real examples. <strong>Bob</strong> was<br />

one of the most accomplished lecturers I ever met, with flair and skill, and impressed<br />

me with little “extras” such as leaving an obvious question out of the talk, and then<br />

Geoscience Society of New Zealand 11

having an extra slide ready to answer the question when someone in the audience<br />

raised it. The course was as enjoyable as it was illuminating. Ironically, <strong>Bob</strong> later<br />

recalled to me an event when he was at Cambridge carrying out his PhD in<br />

paleontology on bivalve form and function under Martin Rudwick during 1965–1967.<br />

He was invited to a party held in the flat of a student who he later realised was Nick<br />

Shackleton. A long graph on endless A4 sheets of paper had been pinned up around<br />

the tops of the walls of the flat. This was the original data for Shackleton’s paradigmchanging<br />

paper on Milankovitch cycles in core V28-238 (Shackleton & Opdyke<br />

1973). The party was to celebrate the completion of the lab work for the fundamental<br />

rewriting of all our concepts of climate and sea-level cyclicity, the timescale of the<br />

Pleistocene and the development of sequence stratigraphy, although its significance<br />

was completely lost on <strong>Bob</strong> at the time!<br />

More recent reminiscences are of the Chatham Islands, where we both took part in<br />

Hamish Campbell’s CHEARS expeditions for several years. One year, <strong>Bob</strong> and I<br />

walked along the north coast of Chatham Island westwards from Cape Young so I<br />

could show him the Tioriori Paleocene succession, with its dinosaur remains and<br />

other interesting fossils. While walking along the cliff edge, we encountered a lone<br />

crested penguin chick sitting by itself in the sun. It was nearly fully fledged, with<br />

brilliant yellow crests well developed on its temples, but still with grey down around<br />

its neck. <strong>Bob</strong> got up really close to photograph it, but it gave out such a sudden,<br />

immensely loud braying noise that we both nearly fell over! It is the only such large<br />

penguin we ever encountered in the Chathams. We went on and examined the<br />

Tioriori section, where it was interesting to see <strong>Bob</strong> struggle to fit the stratigraphy<br />

into his preconceived ideas of sequences in the early Cenozoic succession in the<br />

eastern South Island – he assured me he had managed it.<br />

The outlying islands are some of the most interesting Chathams localities to visit.<br />

<strong>Bob</strong> became quite an ornithologist in later life, and his main interest was to see the<br />

rare birds. On Mangere Island he spent a lot of time photographing the red-crowned<br />

parakeets that are so abundant there, but nowhere else. He was also very solicitous<br />

about a Chatham Islands snipe that was nesting not far behind the hut, right on the<br />

edge of the track, where it was passed several times each day by all seven members<br />

of our party. The snipe was obviously put out by all the attention, and seemed as if it<br />

might leave its nest, but in the end it stayed, because <strong>Bob</strong> pointed out that we should<br />

be quiet near it. <strong>Bob</strong> and I both struggled with the climb up to the summit plateau of<br />

Mangere (287 m straight up! – or so it seemed) but lying about in the flax on the<br />

plateau, with that incredible view to Pitt Island and all the southern islets, made it all<br />

worthwhile. As we were a little low on food there, <strong>Bob</strong> excelled himself with his<br />

culinary flare, concocting a curious mixture of soups and “dehi” one evening from the<br />

DOC emergency supplies, to everyone’s enjoyment. We even found some useful<br />

fossils! – including scallops in blocks of Onoua Limestone that had come up through<br />

the Mangere Island volcano and lay around on the beach. We always had a hilarious<br />

time with <strong>Bob</strong> along, with endless semi-serious discussions – about almost any<br />

subject you can think of, not only geology – with <strong>Bob</strong> acting as devil’s advocate and<br />

pointing out why what we suggested was complete nonsense. His excellent<br />

knowledge of molluscs meant that he and I always had a similar interest in<br />

Chathams stratigraphy and fossils, such as collecting molluscs together from<br />

Titirangi Sand at Lake Te Wapu, near Kaingaroa, at an outcrop discovered by Kat<br />

Holt and Deb Crowley in 2009 (Fig. 6). But <strong>Bob</strong> always thought about the wider<br />

12 Issue 19A Supplement

scientific context, and would be trying to extract a story about Pleistocene sea-levels<br />

out of vague slope changes behind the outcrop, etc., as well as studying the obvious<br />

lithostratigraphy. We always had richly enjoyable times when <strong>Bob</strong> was along, and I<br />

will remember them always as fondly as I will <strong>Bob</strong>.<br />

Fig. 6. <strong>Bob</strong> examining a molluscan shellbed in the Pleistocene Titirangi Shellbed<br />

Formation, NE Chatham Island, SW Pacific, 2011. Photo source: Bill Lindqvist.<br />

#4 – Temporarily being a petrophysicist<br />

Greg Browne 1 , Martin Crundwell 1 , Craig Fulthorpe 2 , Kathie Marsaglia 3<br />

1<br />

GNS Science<br />

2<br />

Instit. Geophysics<br />

3<br />

Geol Sciences<br />

Lower Hutt, New Zealand Univ Texas, USA Calif State Univ, USA<br />

g.browne@gns.cri.nz, m.crundwell@gns.cri.nz, craig@ig.utexas.edu, kathie.marsaglia@scun.edu<br />

Expedition 317 in late 2009 and early 2010 to the Canterbury margin was <strong>Bob</strong>’s last<br />

voyage on the JOIDES Resolution and his last formal involvement with IODP<br />

operations. He had of course been involved with previous deep water drilling<br />

expeditions, especially ODP 181. But unlike that voyage <strong>Bob</strong>’s involvement on<br />

Expedition 317 was not as a Co-Chief Scientist. However, Expedition 317 derived<br />

from research led by <strong>Bob</strong> many years before and he wrote the earliest version of the<br />

IODP proposal. <strong>Bob</strong> did not sail as a sedimentologist, or paleontologist, as might be<br />

expected, but rather as a scientist working on physical properties (Fig. 7).<br />

Petrophysics was a new area for <strong>Bob</strong> but such was his interest in learning new<br />

things in science. <strong>Bob</strong> contributed hugely to this expedition with his tireless energy,<br />

experience and expertise, his probing questions at the daily science meetings, and<br />

Geoscience Society of New Zealand 13

his generosity in helping others out. How could you forget the light-coloured shorts,<br />

his grey or white coloured long socks, and the hand-lens around the neck! He had an<br />

incredible ability to recall facts and publication details. He performed many roles in<br />

addition to undertaking the petrophysical measurements while on board (e.g. Fig. 2),<br />

most notably his identification of macrofossils when such material was recovered in<br />

the cores, his advice to younger scientists, and involvement with media<br />

engagements. <strong>Bob</strong> would commonly predict what we were going to drill into next,<br />

coming up with the first interpretation of the well logs, relating the sediment on the<br />

description table to the seismic, and using his knowledge of Whanganui stratigraphy<br />

to predict the next cycle boundary!<br />

Following Expedition 317 <strong>Bob</strong> continued to remain in contact, and performed a major<br />

role in helping to organise the post-cruise workshop field trip to Canterbury and<br />

Oamaru, enjoying visiting locations in South Canterbury such as Otaio River which<br />

he had not frequented for many years. He will be remembered for his wit and<br />

humour, his thought provoking thinking, even if not always accepted by all, his ability<br />

to consider issues outside-the-box, his respect for others, and his energy and drive<br />

in science. It was a huge surprise therefore that we learned of <strong>Bob</strong>’s passing, and he<br />

will be remembered with fond memories by all of us on Expedition 317.<br />

Fig. 7. <strong>Bob</strong> analysing the physical properties of a sediment core on IODP Expedition<br />

317 of the JOIDES Resolution off eastern South Island in late 2009. Photo source:<br />

William Crawford, IODP.<br />

14 Issue 19A Supplement

#5 - A trilogy (A-C) of <strong>Bob</strong> <strong>Carter</strong> remembrances<br />

Hamish Campbell<br />

GNS Science<br />

PO Box 30368, Lower Hutt, New Zealand 5040<br />

h.campbell@gns.cri.nz<br />

(A) Robert Merlin <strong>Carter</strong>: Strong on ‘Getting a grip’<br />

That middle name is so apt. He was a highly energised trick, just such fun to be with,<br />

full of surprises and always generous in thought, spirit and kind. Here is one of my<br />

early memories of <strong>Bob</strong>.<br />

There is probably a law concerning defacement of railway property but on 31 May<br />

1962, <strong>Bob</strong> did it big time. He would have researched the matter to the nth degree,<br />

have organised a team of willing fully-briefed fellow student associates and then<br />

executed the project with split-second precision (probably with musical<br />

accompaniment), commencing operations within a minute of the Bluff to Lyttleton<br />

Express arriving at Dunedin Station. Our family was on its way to England for a<br />

sabbatical year by ship (Rangitiki) from Wellington. Pretty much the entire Otago<br />

University Geology Department was on the platform to see us off. There were<br />

speeches. <strong>Bob</strong> gave a farewell speech on behalf of the students and presented my<br />

father JD (Doug) Campbell, with a magnificent parting gift: an expensive new watch.<br />

It was then time to board the train and find our seats. I was just 9 and my brother<br />

Neil 7, Joanna just 5 and Rosemary almost 3. Imagine our astonishment when we<br />

discovered head and shoulder portrait photographs of our father neatly sellotaped to<br />

every single window in every carriage on the train! Furthermore, there were two<br />

photos back to back so Dad’s smiling face beamed both inward and outward of the<br />

glass. Every photo was perfectly aligned and the sellotape was the strongest<br />

industrial-strength adhesive on the market. <strong>Bob</strong> was always fastidious with<br />

presentation. There was little prospect of removing these photos. My father would<br />

have been mortified on the one hand, tickled pink on the other. He knew <strong>Bob</strong> better<br />

than <strong>Bob</strong> new himself, but the platform antics were so powerful that Dad’s vigilance<br />

must have been compromised.<br />

I say this because within 5 minutes of the express departing, my parents established<br />

that one piece of luggage, the ‘pig skin grip’, was missing. It contained essentials<br />

such as shaving gear, medicines and contraceptives. This was serious. Dad was<br />

coerced by my mother (…of course, and rightly so; she was a chronic asthmatic with<br />

no need of further children*...) into pulling the emergency stop. The express came to<br />

a halt near St Leonards. The ever so slightly irritated Guard decided that a message<br />

could be sent from Port Chalmers station. Who to? <strong>Bob</strong>. Who else? It was ringleader<br />

<strong>Bob</strong> and associates who had failed to load the grip on the train. Besides, <strong>Bob</strong><br />

was a natural leader of men and totally reliable. The message eventually got<br />

through. The bag was found in the Lost Property office and extricated. The next<br />

problem was how to get it to Lyttleton and the interisland ferry prior to its over-night<br />

sailing that evening? Whatever transpired, it failed. So, the next challenge was to<br />

transport the grip to Wellington from Lyttleton over-night so as to connect in time with<br />

the Rangitiki prior to its departure at 10:30 am on 1 June. A small plane was<br />

Geoscience Society of New Zealand 15

involved. But my father had to go to Wellington Airport to collect the grip and, as a<br />

consequence, he was the last person to run up the gangway moments prior to<br />

departure. Some of us never recovered from this emotional trauma. On discussing it<br />

with <strong>Bob</strong> he was always dismissive, as if it was of no great consequence. He would<br />

say: ‘So what? That is what life is about surely! And besides, it all ended happily.’<br />

[*We left England bound for New Zealand on the Himalaya, departing 7 May 1963,<br />

with new baby Fergus aged 2 months.]<br />

(B) Being on time with <strong>Bob</strong><br />

As a child, I remember going on my first one-day field trip with <strong>Bob</strong> and my father<br />

(Doug Campbell) to Oamaru. I was about 11, so it probably was in 1964. Specifically,<br />

we went to search and collect a shell-bed at Target Gully. As I recall it was a<br />

disappointment. The famous locality had been highly modified by farming practice<br />

and there was little outcrop available for fossil collecting. There was much animated<br />

discussion about the significance of this predicament because it is (or was) an<br />

important type locality. We travelled in <strong>Bob</strong>’s Morris 8. He would have been dressed<br />

for the part, closely resembling Toad of Toad Hall. I recall being anxious on our way<br />

home because I had a 5:30 pm swimming lesson at the Dunedin Municipal Pool in<br />

Moray Place. <strong>Bob</strong> assured me we would make it in plenty of time. However, we only<br />

just made it. The road had been washed out at the ‘big dip’ between the top of the<br />

‘new’ motorway over Mount Cargill and Pigeon Flat. It seemed to take us ages to<br />

inch our way through. <strong>Bob</strong> delivered me with panache at precisely 5:30 with the<br />

exclamation: “There you are! I told you we would be on time.” That may be so but I<br />

still received the full wrath of the swimming instructor for not being in the water at<br />

exactly 5:30! Timing is everything.<br />

I commenced my BSc (Hons) in geology at Otago University (OU) in 1971, and <strong>Bob</strong><br />

was one of my lecturers, spanning five years (I took a ‘gap’ year in 1974). At the<br />

beginning of my 3 rd year, in early 1973, I was a field assistant to Chris Badger, doing<br />

a 4 th year honours project in the head of Edwardson Sound, Fiordland. It so<br />

happened that <strong>Bob</strong> was the master-mind of a multi-faceted project in SW Fiordland<br />

that summer using the OU research vessel Munida. Some others involved were John<br />

Begg as a field assistant to another 4 th year, Gary Post. After a false start on board<br />

the Munida from Dunedin (the alternator packed up off the coast of Brighton…),<br />

Chris and I were flown in to Fiordland by float-plane from Te Anau. We did so on a<br />

superb summer’s day. Our only one! It started raining the next day and stayed that<br />

way forever after. About 10 days later, now with a dead radio and virtually no food, a<br />

naked <strong>Bob</strong> <strong>Carter</strong> suddenly appeared at our tent door. By way of explanation he said<br />

that ‘clothes are pointless in this rain’ (he was always best-dressed). Our great<br />

mentor and leader, and the Munida, had miraculously found us! They were only a<br />

week late.<br />

Chris abandoned that project. After all, we had only found one rock (float) in 12 days.<br />

He was given another project area on Chalky. Meanwhile I spent some days on the<br />

Munida helping <strong>Bob</strong> and John Coggon with a magnetic survey chasing the Last<br />

Cove Fault. It took us a long time to figure out that the crazy data we were collecting<br />

was entirely due to <strong>Bob</strong>’s pragmatism: he had carefully screwed on a metal handle to<br />

the fibre-glass ‘torpedo’ housing for the magnetometer so as to make life easy<br />

16 Issue 19A Supplement

deploying it. Not much came out of this Fiordland campaign. It was bad timing and<br />

bad luck.<br />

At the beginning of 1975, I was now field assisting for Bruce Houghton in the<br />

Takitimus. He and I were delivered to the Wairaki Hut by <strong>Bob</strong> on one of his many<br />

field trips exploring the Waiau Basin. After a very long demanding drive from<br />

Dunedin in the OU Geology Department short-wheel-base Landrover, <strong>Bob</strong> reached<br />

the end of his tether and declared that he was ‘taking us no further’. He leapt out and<br />

opened the back door thus releasing all three dozen eggs that had been perched as<br />

fragile items on top of all else. The whole lot was smashed. Hence that low hill to the<br />

immediate west of the Tin Hut Fault Zone and Wairaki River is affectionately known<br />

as ‘<strong>Carter</strong>’s Egg’.<br />

<strong>Bob</strong> ran a lecture course on ‘integrated’ stratigraphy in my 4 th year called ‘4i’.There<br />

were just two of us in the class: Tom Loutit and myself. We critically analysed the<br />

latest publications on ‘new-fangled’ stratigraphic approaches to the rock record,<br />

namely magnetostratigraphy, oxygen isotope stratigraphy and chronostratigraphy. It<br />

was an exercise in first principles. Every statement would be examined and all<br />

assumptions and error ranges explored and every reference checked. It was<br />

exacting, revealing and damning. We shredded paper after paper on that course! To<br />

me <strong>Bob</strong> was a terrific teacher and he came across as very well read, an outstanding<br />

critical thinker and a sucker for innovative new ways of doing things. I enjoyed his<br />

style and approach immensely. His lectures were about ideas rather than facts, and<br />

hence always difficult to construct notes from. He was just so stimulating and made<br />

you think. However, he often played the devil’s advocate, much to the annoyance of<br />

many students, and it was never easy determining what he really thought. But that<br />

was his point: what he thought was irrelevant. To him, what was important was your<br />

ability (as a student) to make sense of observations using rational thought and logic.<br />

Did I mention showman?! Very few of us come close to <strong>Bob</strong>’s amazing ability to hold<br />

an audience. I think that I am right in saying that <strong>Bob</strong> is the only Hochstetter Lecturer<br />

to use recorded orchestral accompaniment. He always had something profound to<br />

say and his talks were always well-rehearsed and to time.<br />

(C) <strong>Bob</strong> in the Chatham Islands<br />

<strong>Bob</strong> visited the Chatham Islands with me and my many and varied field companions<br />

on six occasions: 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009 and 2011. <strong>Bob</strong> would come for 5 to<br />

10 days at a time. He participated entirely on his own free will and expense. This<br />

was some commitment…coming especially all the way from Townsville. He greatly<br />

enjoyed the Chatham Islands and came for four main reasons: to escape the<br />

summer heat of northern Queensland, to indulge in two of his many enthusiasms of<br />

bird watching and photography, to apply his considerable geological knowledge and<br />

experience in a remote part of New Zealand, and to relax in congenial and<br />

stimulating intellectual company (fellow geologists, biologists and research students<br />

in their element: the field….but not necessarily like-minded note) within a ready<br />

back-drop of real people (i.e. Chatham Islanders) who, like him, lived off their wits<br />

and lived well off the land and sea (red wine and fine cuisine dominated by blue<br />

cod).<br />

Geoscience Society of New Zealand 17

To some extent, the Chathams offered respite for an embattled <strong>Bob</strong>, so intensely<br />

committed and embroiled in keeping climate change science honest. Where better to<br />

hide for a few days and recharge the batteries but at the very end of the weather<br />

forecast?! Needless to say, it fell on us his erstwhile companions to try and keep him<br />

honest. A constant battle in itself but boldly addressed by the likes of Chuck Landis,<br />

John Begg, Alan Beu and everyone else when needs be. On two of these trips <strong>Bob</strong><br />

was accompanied by his brother-in-law and close friend Bill Lindqvist, a Californiabased<br />

consulting geologist, married to Anne’s sister Helen.<br />

Every moment with <strong>Bob</strong> was memorable and he contributed greatly to our<br />

experiences in the Chathams and our geological understanding. On his first trip (25-<br />

30 Jan, 2005), he joined us on a one-day trip to the Forty Fours (27 Jan), an<br />

albatross colony far to the east of Chatham Island, but sadly <strong>Bob</strong> chose not to<br />

attempt to land claiming that his ‘upper body strength was not up to it’. We had to<br />

negotiate a near-vertical 60 m cliff aided with ropes. I am quite sure that he would<br />

have managed just fine. The party included: Chris Adams, Bill <strong>Carter</strong>, Steve Trewick,<br />

John Begg, Rowan Emberson, David Given, Paul Scofield, Mark Bellingham, Peter<br />

Johnston and myself.<br />

<strong>Bob</strong>’s second visit (27 Jan-3 Feb, 2006) involved an ambitious 4-day trip to The<br />

Horns at the SW tip of Chatham Island with John Begg, Chuck Landis, Alan Beu,<br />

Jeremy Titjen and Chris Consoli. This letter from <strong>Bob</strong> just prior to the trip says it all:<br />

24/1/06<br />

Hamish, honeybun<br />

I did not realise that you had dobbed me in for the doubtless magnificent experience<br />

of sleeping under canvas on tussock again.<br />

As I am now in transit (passing through Brisbane airport) I can't grab a sleeping bag<br />

(which is probably a good thing, given the amount of clobber that I'm already<br />

carrying).<br />

I'm staying with Lionel [<strong>Carter</strong>] tomorrow and Thursday nights, and will see if I can<br />

borrow one from him. Failing that, you may get a phone call asking if you can throw<br />

in an extra.<br />

Torch? Persons of my age have specially well-developed sixth senses which enable<br />

them to avoid pissing on others when they creep out for their nightly visit. Besides,<br />

we don't want to scare the petrels.<br />

See you soon. <strong>Bob</strong><br />

It demonstrates classic <strong>Bob</strong>: his natural collegiality, charming his way around<br />

authority, following instructions in a timely fashion and revealing the main reason for<br />

his visit: bird watching!<br />

The third trip (31 Jan-9 Feb, 2007) involved another very memorable visit this time to<br />

Southeast Island (6-7 Feb), home to millions of seabirds not to mention the Black<br />

18 Issue 19A Supplement

Robin, Chatham Snipe and Shore Plover. The party included Alan Beu, Alex<br />

Malahoff, Nigel Miller, Phil Sirvid and myself.<br />

The fourth visit (29 Jan-6 Feb, 2008) involved two nights on Pitt Island staying at The<br />

Bluff (James & Annette Moffett) with Bill Lindqvist, Alex Malahoff, Alan Beu, Nigel<br />

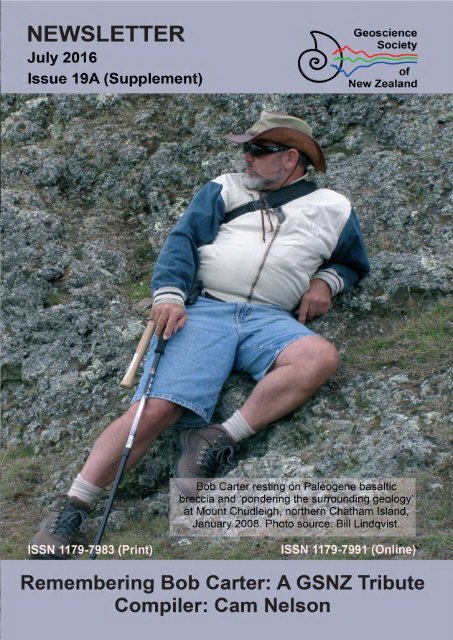

Miller and his son Oliver, Peter Cook and myself (e.g. Figs 3, Front cover).<br />

The fifth visit (26 Jan-4 Feb, 2009) was another very memorable visit, this time to<br />

Mangere Island (2-3 Feb) with Alan Beu, Nigel Miller, Kat Holt, Deborah Crowley and<br />

myself. <strong>Bob</strong> made a spectacular landing on his hands and stomach, as he misjudged<br />

the leap from the boat. His flesh wounds required the combined services of both<br />

doctor (Nigel) and nurse (Deborah). A lasting memory I have of this trip is assisting<br />

<strong>Bob</strong> with DOC’s demands to rid his field clothing and gear of undesirable seeds. It<br />

took many hours for the whole team to de-seed <strong>Bob</strong> to an acceptable standard!<br />

<strong>Bob</strong>’s last visit was in 2011 (26 Jan-2 Feb), again with Bill Lindqvist. The party<br />

included Alan Beu, Alex Malahoff, David Johnston and his wife Carol Stewart and<br />

their son Joshua, Deborah Crowley, Alexa van Eaton and myself. We visited Pitt<br />

Island (Fig. 8), staying at The Bluff with the Moffetts again (27-30 Jan), but this time<br />

we had our very own French cook, Nathalie Robert-Peillard.<br />

Fig. 8. Hamish Campbell and <strong>Bob</strong> <strong>Carter</strong> aboard the Chatham Express vessel on a<br />

trip from Chatham Island to Pitt Island in 2011. Photo source: Bill Lindqvist.<br />

Geoscience Society of New Zealand 19

#6 - All at sea with <strong>Bob</strong> <strong>Carter</strong><br />

Lionel <strong>Carter</strong><br />

Antarctic Research Centre, Victoria University of Wellington<br />

PO Box 600, Wellington, New Zealand 6012<br />

lionel.carter@vuw.ac.nz<br />

As the research ship Tangaroa I sailed south from Wellington Harbour on a wintery<br />

day 4 August 1977, little did we know that this was the start of a research<br />

collaboration between <strong>Bob</strong> <strong>Carter</strong> and myself that lasted over 25 years. And let me<br />

set the record straight from the start, <strong>Bob</strong> <strong>Carter</strong> and Lionel <strong>Carter</strong> were neither<br />

brothers nor father and son; we were the cliché….”just good friends”!<br />

In the halcyon days of the 1970s, the New Zealand Oceanographic Institute (NZOI)<br />

allocated ship time for the universities and in 1977 it was Otago University's turn with<br />

<strong>Bob</strong> as the cruise leader. We both had a deep interest in the research, which was to<br />

establish the dispersal of sediment along and across the Otago continental margin<br />

into the Bounty Trough. But my main role was to represent the Oceanographic<br />

Institute to ensure the voyage ran smoothly. This became a life lesson, namely that<br />

sailing with <strong>Bob</strong> was anything but dull. On this voyage an altercation broke out<br />

amongst two crew members. This required Tangaroa I to return to Port Chalmers<br />

where the police met the ship and retained the crew members. The cook was also<br />

taken away in an ambulance due to burns sustained in the galley following a<br />

particularly severe roll of the ship. The unscheduled port call was prolonged by a<br />

search for replacement crew who eventually arrived from Auckland. The follow-up<br />

voyage in 1979 was accompanied by the loss of a Klein side-scan sonar - a towed<br />

seabed mapping system, which in those days was worth a year's salary. When the<br />

ship returned to Wellington, the Oceanographic Institute truck was waiting for us,<br />

complete with a hangman's gibbet and noose. This subtle hint indicated whose<br />

salary was in peril - mine. However, <strong>Bob</strong> came to the rescue with a NZ$5,000<br />

contribution that assuaged the NZOI administration and ensured his presence on<br />

future voyages. Yet again, the <strong>Carter</strong> curse struck, this time in 1990 on the Rapuhia -<br />

Tangaroa's successor. The main winch broke down while coring in 4000 m of water.<br />

For the next 31 hours, Rapuhia drifted in moderate seas with 4 km of heavy wire<br />

attached to a one ton corer hanging over the side. Positioning was also a problem<br />

because it was the time of the Gulf War and the satellites that formed the nascent<br />

global positioning system were realigned to cover the Middle East.<br />

While it is fun to reminisce over a beer, these events were in reality a mild distraction<br />

from the science. Between 1977 and 1998, five voyages off the eastern South Island<br />

revealed the evolution of a remarkable sedimentary system from its inception in the<br />

Cretaceous through the Quaternary climatic cycles to the present day. It was the first<br />

Source-to-Sink analysis that traced the passage of river sediment from the coast,<br />

across the continental shelf, down the continental slope via submarine canyons and<br />

into the Bounty Channel system where turbidity currents transferred South Island<br />

debris over 1000 km eastward to feed the vast submarine Bounty Fan. Sediment did<br />

not stop there. The Pacific deep western boundary current entrained fan sediment<br />

and carried it another 3000 km to accumulate in the Kermadec subduction zone.<br />

20 Issue 19A Supplement

Thanks to <strong>Bob</strong>'s expertise and great enthusiasm, plus help from his friends, we were<br />

beginning to learn how undersea New Zealand functioned. Over 20 papers appeared<br />

under the co-authorship of <strong>Carter</strong> and <strong>Carter</strong> (and many colleagues). One wit<br />

compared C and C to Thomson and Thompson in the Tintin chronicles, but hopefully<br />

the publications of the former were a little more factual than the comic books.<br />

As the eastern South Island marine geology became clearer, <strong>Bob</strong> noted that it would<br />

be a suitable topic for the Ocean Drilling Program (ODP). That was in 1993. Five<br />

years later, ODP Leg 181 came to fruition with the drilling of 7 sites off eastern New<br />

Zealand. This furthered our knowledge of paleoceanography and marine geological<br />

evolution of the key region of the SW Pacific Ocean where tectonic plates and major<br />

ocean currents collide. That research continues today using the cores archived from<br />

Leg 181 and other ocean drilling legs. Leg 181 would not have happened without<br />

<strong>Bob</strong>'s energy and persuasive skills. At the time, New Zealand was not a member of<br />

ODP and thus could not develop and lead voyages. However, Australia was a<br />

member and <strong>Bob</strong>, who was then domiciled in Queensland, could begin the long<br />

proposal process. The proposal received a major boost when Nick McCave<br />

(Cambridge University, UK) joined. This brought the UK membership to bear. <strong>Bob</strong>'s<br />

"people skills" were much needed in light of the political and competitive elements of<br />

large multinational programmes. My contribution was to keep the proposed drilling<br />

site data and science components on cue. This called for reflex responses to phone<br />

calls along the lines "Hello. <strong>Bob</strong> here. I'm in College Station, Texas. An ODP<br />

scientist has just noted that waves on the Chatham Rise are too large for safe<br />

drilling. Can you run an analysis of the wave climate and get back to me within the<br />

hour?" Such was life with RMC.<br />

Following the undeniable success of Leg 181, <strong>Bob</strong> expanded his interest in<br />

sequence stratigraphy, the marine geology of the Great Barrier Reef and of course<br />

climate change. While our views differed regarding the last topic, the friendship<br />

endured. Without doubt, Robert Merlin <strong>Carter</strong> was a major contributor to New<br />

Zealand marine geology through his research, enthusiasm and ability to make things<br />

work (apart from ship's winches). It is a fine legacy.<br />

#7 - Livening up geological discussions<br />

Penny Cooke<br />

Brookes Bell Group (Marine Consultants & Surveyors)<br />

Walker House, Exchange Flags, Liverpool, UK L2 3YL<br />

cooke.penelope@gmail.com<br />

My memories of <strong>Bob</strong> are somewhat intermittent as they focus around the annual<br />

conference of the Geoscience Society of New Zealand (<strong>GSNZ</strong>). I recall him being<br />

very friendly and inclusive, and louder than many. I recall annual conference dinners<br />

being improved by his contributions to discussions, even after several bottles of wine<br />

had been consumed by all involved (Fig. 9). In addition, he was the external<br />

overseas examiner for my PhD thesis on Neogene paleoceanography in the Tasman<br />

Sea, about which he was very complimentary, and he only required minor changes<br />

for which I was most grateful.<br />

Geoscience Society of New Zealand 21

Fig. 9. Participants engrossed in ‘deep stimulating conversation’ with <strong>Bob</strong> (and wine<br />

drinking) at the BBQ at <strong>GSNZ</strong> annual conference in Kaikoura, 2005. People<br />

recognised are (left to right) Alan Orpin, Cam Nelson, Penny Cooke, unknown, <strong>Bob</strong><br />

<strong>Carter</strong>, David Smale and Anne <strong>Carter</strong>. Photo source: Unknown.<br />

I became aware some years later that <strong>Bob</strong> was being described as a 'humaninduced<br />

climate change skeptic' and had been presenting his views on this matter to<br />

government committees. I have to say I was a little surprised as he had been<br />

involved over the years in research dealing with marine sediment records and the<br />

climate records they contain. I understand and commend the independence of<br />

scientists to interpret the data they see in the way they deem appropriate, and <strong>Bob</strong><br />

certainly did this over his long and distinguished career. The news released in May<br />

2016 by NASA that April was the seventh month in a row that broke global<br />

temperature records would have made for interesting discussions with <strong>Bob</strong> I suspect.<br />

I can only hope that all those still employed in climate science are able to include a<br />

little skepticism into their research as it is only by questioning the accepted views<br />

that we can progress. Having read many of <strong>Bob</strong>'s articles on climate change, I<br />

personally still remain convinced that humans are influencing our global climate, but<br />

to what extent remains debatable. I shall be enjoying my glass of wine in the warm<br />

spring 2016 sunshine in the UK and will be thinking very fondly of <strong>Bob</strong> and his major<br />

contributions to New Zealand geosciences over many decades.<br />

22 Issue 19A Supplement

#8 - A family of young academics<br />

Alan Cooper<br />

Geology Department, University of Otago<br />

PO Box 56, Dunedin, New Zealand 9054<br />

alan.cooper@otago.ac.nz<br />

In the late 1960s to early 1980s, during the <strong>Carter</strong>’s stay in Dunedin, the Geology<br />

Department at Otago was a dynamic and enjoyable place to work. It included a<br />

group of other young families (Reay, Landis, Norris, Henley, Bishop and Cooper)<br />

busy bringing up young children and building careers. Despite that, there was time<br />

for socialising and, regardless of the heavy teaching loads for the guys, even time for<br />

the occasional Wednesday afternoon round of golf! <strong>Bob</strong> and I worked at opposite<br />

ends of the geological spectrum, but we were mates and took an interest in what the<br />

other was doing (Fig. 10). <strong>Bob</strong> even spent time with me in an appropriately named<br />

Roaring Swine tributary of the Haast River during my PhD. For a week we huddled<br />

under a three-sided, plastic-sheeted shelter while the heavens opened and the valley<br />

filled with water and the creek lived up to its name. The upper echelons of the<br />

Department were somewhat taken aback when RMC’s princely field allowance of $2<br />

per day was subsequently claimed for ‘field supervision’ (in metamorphic petrology!).<br />

<strong>Bob</strong> was one of our leading lights, energetic, innovative, inspirational and an<br />

excellent communicator. We missed the <strong>Carter</strong>s when they moved to Townsville and<br />

we will miss him now.<br />

Fig. 10. <strong>Bob</strong>, interested in ‘all<br />

things geological, including<br />

metamorphic rocks’, examining a<br />

sample of Alpine Fault mylonite.<br />

Photo source: Alan Cooper.<br />

Geoscience Society of New Zealand 23

#9 – He sure made you think critically<br />

Dave Craw<br />

Geology Department, University of Otago<br />

PO Box 56, Dunedin, New Zealand 9054<br />

dave.craw@otago.ac.nz<br />

<strong>Bob</strong> was one of the most inspiring lecturers I had as a student at Otago in the 1970s.<br />

He even managed to make paleontology interesting to this physical scientist, by<br />

bringing in a wide range of ideas and different threads to his accounts of how the<br />

biological world works. He made me THINK, which was quite an achievement. His<br />

enthusiasm and energy were boundless around the Geology Department, and he<br />

was innovative in everything he did. I was sorry to see him leave, and that was<br />

definitely James Cook University's gain. I kept in touch with him over the years as I<br />

evolved into an economic geologist, and always admired his enthusiasm and<br />

foresight in setting up the Economic Geology Research Unit in Townsville. This was<br />

the right move at the right time, a very astute step that did a great deal to help the<br />

Townsville department expand and appear on the international radar of an important<br />

industry to Australia. <strong>Bob</strong> was still making me think in his later years when he<br />

entered the controversial world of climate change, and I thoroughly enjoyed talking to<br />

him about these things, even if I didn't always agree with him. He brought some<br />

serious science to that debate, especially with regard to sea levels, and I found his<br />

research and ideas fascinating in that general area. I last saw <strong>Bob</strong> when he visited<br />

Otago recently to talk about climate change, and he was in excellent form then, still<br />

enthusiastic, stimulating, a great lateral thinker, and an excellent public speaker.<br />

That's the <strong>Bob</strong> <strong>Carter</strong> that I will always remember.<br />

#10 - So influential on my career development<br />

Barry Douglas<br />

Douglas Geological Consultants<br />

14 Jubilee Street, Belleknowes, Dunedin, New Zealand 9011<br />

barrydouglas@xtra.co.nz<br />

Fresh from his PhD research at Cambridge, <strong>Bob</strong> <strong>Carter</strong> returned in 1968 to the<br />

Otago Geology Department as a lecturer in Cenozoic paleontology and stratigraphy.<br />

I was fortunate to be among the first group of students to attend <strong>Bob</strong>’s lectures.<br />

<strong>Bob</strong> made an immediate impact in his teaching at Otago. His lectures on functional<br />

morphology, taxonomy, paleoecology, stratigraphy, Recent and ancient sedimentary<br />

environments and paleoclimate change with relevance to New Zealand strata were<br />

the conceptual roots from which I and many of his students formulated their<br />

approach to postgraduate research. <strong>Bob</strong> was an inspiring lecturer and he involved<br />

24 Issue 19A Supplement

his students in his research interest. In those early years <strong>Bob</strong> also forged the link<br />

between the Geology Department and the University’s Portobello Marine Biological<br />

Station through his close association with the then Director Dr Betty Batham. He took<br />

his research students to sea, out over the Otago shelf on the University research<br />

vessel Munida, to observe at first hand the sediment-fauna relationships of modern<br />

communities as retrieved from sea-floor grab samples. Under heavy swell, <strong>Bob</strong> was<br />

a better sailor than I was!<br />

<strong>Bob</strong>’s dedication to facilitate excellence in research was exemplified by the energy<br />

and enthusiasm he exuded in his self-driven task of updating and further developing<br />

the molluscan collection in the Geology Department Museum at Otago. He worked<br />

tirelessly in the evenings and weekends in the museum or in the adjoining curator’s<br />

room under the watchful portraits of Marwick, Finlay, Hutton and Fleming, as he<br />

catalogued specimens and developed a formidable illustrated reference card system<br />

(pre-computers). His new specimens were foraged from field collections from both<br />

North and South Island (NZ) and elsewhere. <strong>Bob</strong> never missed an opportunity to<br />

improve the collection. I recall, in 1971, when he dispatched me to collect type<br />

section specimens from the bed of the Waiau River at Clifden during a temporary<br />

controlled low river level. It was a case of one eye on the task and one eye on the<br />

rising water level! Long after his departure from Otago the curatorship and welfare of<br />

the molluscan fossil collection was of foremost concern to <strong>Bob</strong>. Our last conversation<br />

specifically related to this matter.<br />

<strong>Bob</strong> often invited his students to accompany him in the field and this was also<br />

generally the case when he was in the company of a visiting distinguished<br />

researcher. He generously offered his students every opportunity. He introduced his<br />

students to the key field sections of the regional Cretaceous-Cenozoic sequence.<br />

<strong>Bob</strong>’s observations were acute, his commentary informative and his questions<br />

thought provoking. I have had the opportunity to revisit many of those sections over<br />

the years and without exception I am reminded of the occasion of my first visit to<br />

those sites with <strong>Bob</strong>. Such was the influence of <strong>Bob</strong> and his teaching, that in the<br />

years gone by, there is hardly a day when logging a cored bore or measuring a<br />

stratigraphic section in southern New Zealand that I have not thought of <strong>Bob</strong> <strong>Carter</strong><br />

and been grateful for the skills of observation and detailed recording I developed<br />

from his teaching.<br />

<strong>Bob</strong> supervised my MSc investigation of the South Canterbury Tengawai River<br />

section. In 1973, on a day trip to Lauder to collect oncolites he introduced me to the<br />

non-marine sediments of Central Otago. That same year we co-authored a report on<br />

the Otago lignite deposits for ICI (NZ) Ltd. in collaboration with associated work<br />

carried out at the Otago School of Mines. The thrust of my future research and<br />

employment specialisation was nurtured in those early discussions with <strong>Bob</strong> on<br />

Otago-Southland non-marine sedimentary environments.<br />

<strong>Bob</strong> was one to quip a cheeky remark. I vividly recall the occasion around 1977 on<br />

the isolated Doolans Saddle track between the Gibbston Coalpit Saddle and the<br />

Lower Nevis Valley where we bogged the Land Rover to the axle and were almost<br />

immediately accosted by an enraged high country station owner. Infuriated with<br />

<strong>Bob</strong>’s quip in defence of the situation the frustrated landowner swung at <strong>Bob</strong>. <strong>Bob</strong><br />

Geoscience Society of New Zealand 25

dodged the blow, but the fist made contact with <strong>Bob</strong>’s tartan cap which was sent<br />

flying through the air.<br />

<strong>Bob</strong> stood tall in defence of good science practice and honesty. I was grateful for his<br />

support in1977 during my challenges to aspects of the Upper Clutha hydro scheme<br />

and again in the late 1970s when I was embroiled in argument with the Mines<br />

Department over the Central Otago coal drilling fiasco. <strong>Bob</strong>’s departure from Otago<br />