E-Issue3_Finallydonep

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Table Of Contents<br />

Cover Artist<br />

Statement<br />

42<br />

34<br />

NON<br />

FICTION<br />

30<br />

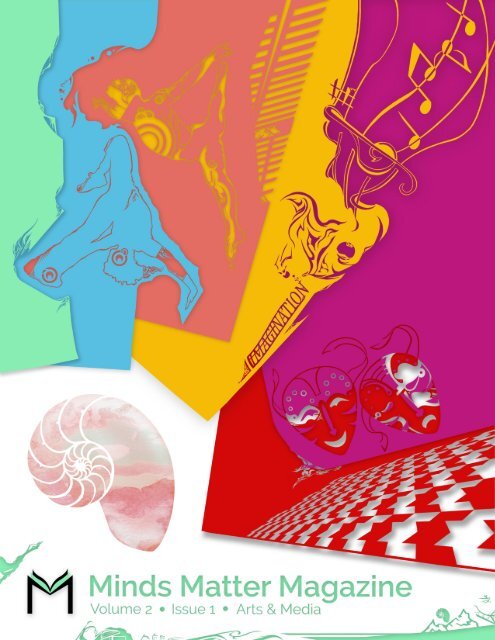

Mental health is a very nuanced topic, with<br />

the kind of many layered complexity that can<br />

be daunting. The same could be said for art<br />

or media; they are both categories that often<br />

intersect with others like politics, philosophy,<br />

and science. The cover image of Volume 2<br />

Issue 1: Arts & Media embraces such intricacy<br />

and celebrates it. Centred on the idea of layers<br />

and intersectionality, spirals and paper art<br />

are the main visual inspirations for this digital<br />

art piece.<br />

The nautilus is a great source of inspiration<br />

and is chosen as a visual cornerstone for<br />

all that it could represent. The nautili are an<br />

ancient species that predates the dinosaurs by<br />

more than 250 million years. Its shell speaks<br />

of math, science, and the human brain’s cerebrum<br />

that recalls that same spiral shape. On<br />

the cover, each paper in the cascade following<br />

that shape features stylized variations on<br />

modes of art and media representation and<br />

recalls something from every article. Every<br />

layer plays on shadow and the<br />

colour of those underneath to form a fuller<br />

picture. The multilateral relationship between<br />

them is a deliberate statement on the frequent<br />

trend of issues and values and symbols<br />

to feed into and off of each other--given<br />

enough time. As with mental health, a closer<br />

look reveals a rich depth of detail: from the<br />

masks beneath the masks, to the boat floating<br />

in nothingness.<br />

Jenny Ann Soriano, Graphic Designer<br />

A fourth year student at UTSC, Jenny Ann<br />

is working towards a major in New Media<br />

Studies and a double minor in Linguistics and<br />

Psychology. An alumna of Norte Dame High<br />

School in Toronto, she credits her artistic skills<br />

to the encouragement and mentorship by a<br />

number of her facilitators and peers.<br />

58<br />

47<br />

STILL<br />

ART<br />

62 FICTION<br />

72<br />

74<br />

POETRY<br />

21<br />

16<br />

MUSIC<br />

13<br />

2<br />

8

Minds Matter Magazine Volume II Issue I Arts & Media<br />

Theme<br />

Advisor<br />

As an educator, there are few things more gratifying than stepping back and enabling students<br />

to independently realize their own creative academic projects. As Theme Advisor, I have had<br />

the pleasure of witnessing the assembly of an issue by a remarkable team of undergraduates<br />

at the University of Toronto Scarborough. Over the past year, Minds Matter Magazine’s student<br />

journalists, graphic designers, illustrators, and editors have worked hard to explore the vast<br />

and challenging issue of mental health. I commend their dedication to presenting some of the<br />

many ways that the arts and media influence perceptions of mental health and illness.<br />

Why “Arts and Media”? For some readers, this issue’s focus on creative activity may<br />

seem like a whimsical, maybe even trivial, approach to the topic of mental health. However,<br />

the growth of arts-based health research methods and interdisciplinary fields of study<br />

like Health Humanities indicate how the human imagination—that is, how we imagine what<br />

mental health and illness is or could be—can enrich conventional therapeutic approaches for<br />

people living with conditions like depression, or enhance health care relationships by making<br />

research accessible beyond academia. In this issue, several articles and creative contributions<br />

address the therapeutic benefits of the arts, including an interview with Workman Arts, a<br />

Toronto-based organization dedicated to empowering artists with mental illness and addiction<br />

issues. A growing evidence base further indicates that participation in the arts is a low-cost,<br />

low-risk, and practical enhancement of conventional mental health care. Arts- and humanities-based<br />

approaches to health may even have benefits for health care workers and informal<br />

caregivers themselves, a phenomenon that UK-based health researcher Paul Crawford calls<br />

“mutual recovery” (2013).<br />

The arts hold the potential to delight,nourish, soothe, and heal. But the therapeutic potential<br />

of the arts must not overwhelm another equivalent reality: that the arts are a powerful<br />

mode of communication that shape, for better and for worse, what it means to live with mental<br />

illness. A range of critical and creative contributions to this issue therefore attend to art’s<br />

unsettling potential to confront, antagonize, intimidate, even traumatize its audience—effects<br />

that may be enhanced by popular art forms that are widely disseminated through media platforms<br />

old and new. As someone with a research background both in the humanities and the<br />

health sciences, I have always been mystified by people who describe the arts and humanities<br />

as “soft” (as opposed to the so-called “hard” sciences). Make no mistake: art is spiky, barbed,<br />

and caustic just as often as it appears otherwise. The essays, poems, and articles of this issue<br />

grapple with this risky reality of art’s relationship to mental health. I encourage you to read on<br />

and consider how we might take better care of ourselves—and each other—as a result.<br />

Dr. Andrea Charise<br />

Assistant Professor of Health Studies,<br />

University of Toronto Scarborough<br />

Associate Faculty,<br />

Graduate Department of English,<br />

Core Faculty, Collaborative Graduate Program in Women’s Health<br />

University of Toronto<br />

Reference:<br />

Paul Crawford, Lydia Lewis, Brian Brown, Nick<br />

Manning. “Creative Practice as Mutual Recovery<br />

in Mental Health.” Mental Health Review<br />

Journal, 18.2 (2013): 55-64.<br />

4 5

Editor In<br />

Chief<br />

Incoming<br />

Editor<br />

Made with lots of love, ‘Arts and Media’<br />

strings together a crafted collection of inhouse<br />

pieces from our own journalists,<br />

student artists from across Canada in our<br />

inaugural #MindMyArt submissions contest<br />

in fiction, non-fiction, poetry, still art, and<br />

music. Our collection this year also celebrates<br />

a special collaboration with University of<br />

Toronto Scarborough (UTSC)’s creative writing<br />

anthology, Scarborough Fair (SF), whereby<br />

MMM and SF both co-publish the top student-written<br />

mental health-related pieces<br />

from SF’s international creative writing contest.<br />

Throughout our e-issue, our aim is<br />

to broaden our freedom of thought, belief,<br />

opinion and expression in creative media. Our<br />

highly collaborative process—involving our<br />

masthead of 26 students and recent alumni;<br />

contest adjudicators from students, recent<br />

alumni, and faculty from the writing center,<br />

department of English, department of arts,<br />

culture, and media; students from 16 Canadian<br />

post-secondary institutions—is highly<br />

credited to the close-knittnedness of the<br />

UTSC campus, of starting small.<br />

The nature of our e-issue theme aims<br />

to spark the conversation of how arts and<br />

media in relation to mental health can preserve<br />

the communal sense of UTSC as our<br />

campus expands over the next 25 to 50 years.<br />

With discussions to continue on what the<br />

UTSC campus will look like, our e-issue hopes<br />

to bring more visibility and attention to the<br />

arts on campus. With scattered pockets of<br />

spaces at UTSC dedicated towards arts often<br />

tucked in unexpected spaces, conversations<br />

about mental health, too, take place in unexpected<br />

places.<br />

Karen Young<br />

Karen finished her undergraduate program<br />

double majoring in psychology and health<br />

studies and is awaiting convocation.<br />

At Minds Matter Magazine, we know we have<br />

succeeded when we convince another person<br />

that they are not alone.<br />

And yet, is this not the case with all art?<br />

To find another person who lies upon another<br />

entirely unique plane of perception, and have<br />

them realize...<br />

….<br />

They see themselves.<br />

In this piece, and in someone else.<br />

And how utterly indispensable is this connection<br />

when you are in pain.<br />

Particularly, an invisible kind of pain.<br />

Keep an eye out for our next edition on ‘culture and transition’ and the surrounding<br />

mental health themes that accompany this.<br />

Alexa Battler<br />

Alexa is a third year student specializing in<br />

journalism and minoring in political science<br />

6<br />

7

Minds Matter Magazine Volume II Issue I Arts & Media<br />

What We<br />

Actually Know<br />

About Psychopathy<br />

By Alexa Battler<br />

Media sources have long since adored stories<br />

about ‘psychopaths,’ including classic cinematic<br />

villains like Hannibal Lector and Alex<br />

DeLarge, more recent television antiheroes<br />

like Dexter Morgan and Frank Underwood,<br />

and real-life examples like Jeffrey Dahmer<br />

and Robert Pickton. The term has come up<br />

repeatedly through the American presidential<br />

race, through accusations that both Donald<br />

Trump and Hillary Clinton may be psychopaths.<br />

But are any of these individuals absolute<br />

examples? Technically no, because no<br />

Illustration by Alice Shen<br />

singular, undisputed definition or diagnosis of<br />

psychopathy even exists.<br />

Psychopathy is a fluid concept with<br />

an equally unstable past. Its most common<br />

understanding was perhaps best surmised in<br />

its first official definition. In the early 1800s,<br />

French psychiatrist Philippe Pinel coined the<br />

term “manie sans délire” (insanity without<br />

delirium) to describe those who showed no<br />

outward signs of psychosis, yet still behaved<br />

with an exceptional moral depravity of which<br />

the general population was incapable. [1] The<br />

actual term ‘psychopath’ was coined by German<br />

psychiatrist J.L.A. Koch in 1888, though<br />

the definition was then broadened to include<br />

anyone who caused harm to themselves or<br />

others. [1] This dismissed the diagnostic roots<br />

in moral depravity that Pinel had established,<br />

and that is now recognized as a central characteristic.<br />

By the 1920s the term broadened<br />

further, and defined anyone exhibiting abnormal<br />

psychology. [1] People who were depressive,<br />

submissive, or notably withdrawn or<br />

insecure were all deemed psychopaths.<br />

"Manie sans délire"<br />

(insanity without delirium)<br />

The meandering definition was<br />

eventually centered in a book by an American<br />

psychiatrist: Hervey Cleckley, “the most<br />

influential figure in the study of psychopathy.”<br />

[2] In the first edition of his 1941 book,<br />

accurately titled The Mask of Sanity: An<br />

Attempt to Clarify Some Issues About the<br />

So-Called Psychopathic Personality, Cleckley<br />

described 21 characteristics that constituted<br />

a psychopath, though these would later be<br />

shortened to 16 in all subsequent five revisions.<br />

[3] In 1980, Robert Hare, a Canadian<br />

professor and criminal psychology researcher,<br />

drew heavily on ideas from Cleckley’s book to<br />

create a determining measure for psychopathy.<br />

In 1991, this test was revised to become<br />

what is now widely considered the “gold standard”<br />

of psychopathy diagnoses, The Hare<br />

Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R). [2]<br />

The Psychopathy Checklist-Revised: [4]<br />

1. Glib and superficial charm<br />

2. Grandiose (exaggeratedly high)<br />

estimation of self<br />

3. Need for stimulation<br />

4. Pathological lying<br />

5. Cunning and manipulativeness<br />

6. Lack of remorse or guilt<br />

7. Shallow affect (superficial<br />

emotional responsiveness)<br />

8. Callousness and lack of empathy<br />

9. Parasitic lifestyle<br />

10. Poor behavioral controls<br />

11. Sexual promiscuity<br />

12. Early behavior problems<br />

13. Lack of realistic long-term goals<br />

14. Impulsivity<br />

15. Irresponsibility<br />

16. Failure to accept responsibility<br />

for own actions<br />

17. Many short-term marital<br />

relationships<br />

18. Juvenile delinquency<br />

19. Revocation of conditional release<br />

20. Criminal versatility<br />

The PCL-R describes 20 traits used to<br />

examine the existence and degree of psychopathy<br />

in adults (Hare also modified a<br />

version of the test for youth, ages 12-18). [4]<br />

Traits are identified through a two-part examination:<br />

a review of collateral information<br />

(e.g. nature of relationships, familial medical<br />

and personal history, stability of education,<br />

8<br />

9

Psychopathy<br />

Alexa Battler<br />

Minds Matter Magazine Volume II Issue I Arts & Media<br />

work, and social life), and a relatively structured<br />

interview with the patient—though,<br />

in the PCL-R, a diagnosis of psychopathy can<br />

also be achieved without the latter. Patients<br />

are then given a score out of 40. A clinical<br />

diagnosis of psychopathy is issued at a score<br />

of 30 or more. People who do not have criminal<br />

backgrounds normally score around<br />

five, while many non-psychopathic criminal<br />

offenders often score around 22. Hare also<br />

asserted that results of the checklist are only<br />

reliable if the testing has been conducted by<br />

a properly licensed clinician, and in a properly<br />

licensed and regulated environment. It is the<br />

PCL-R that is used in courts and institutions in<br />

order to test for psychopathy, likelihood of<br />

recidivism, and necessity of treatment; it also<br />

aids in determining the type and extent of<br />

criminal sentencing.<br />

And yet, true to history, there are still<br />

many that denounce and challenge Cleckley,<br />

and the PCL-R. The PCL-R has been criticized<br />

for having too great a focus on criminality,<br />

and for being too tailored for a typical prison<br />

demographic, instead of for the general public.[5]<br />

Questions have also been raised over<br />

the feasibility of clinicians conducting the<br />

checklist to accurately identify these traits. [5]<br />

To rectify these perceived faults, Dr.<br />

Scott O. Lilienfeld, an American psychologist<br />

and psychology professor, created another<br />

test now among the most frequently used<br />

self-report measures of psychopathy, [6] the<br />

Psychopathic Personality Inventory-Revised<br />

(PPI-R), in 2005 (revised from the original<br />

edition in 1996). The PPI-R is instead self-administered,<br />

and has 154 traits divided into<br />

two categories: fearless dominance and<br />

self-centered impulsivity. In turn, there have<br />

been disputes over this test as well—some<br />

have argued that the fearless dominance<br />

category does not accurately indicate<br />

psychopathy itself, and that the self-administration<br />

aspect of the test is unreliable. [7] Professional<br />

consensus is spread over the many<br />

other significant tests, including the triarchic<br />

model of psychopathy, the categories for<br />

which are boldness, disinhibition, and meanness,<br />

while public consensus darts around the<br />

765,000 results that pop up upon Googling<br />

“psychopathy test.”<br />

"PPI-R is divided into two<br />

categories: fearless<br />

dominance and<br />

self-centered impulsivity."<br />

Despite its notoriety, there is no official<br />

diagnosis for psychopathy in the Diagnostic<br />

and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders<br />

(DSM-V), the standard criteria for diagnosing<br />

and understanding mental disorders in North<br />

America. The DSM has attempted to create<br />

a diagnosis for psychopathy, called Antisocial<br />

Personality Disorder (ASPD), [8] which overlaps<br />

with many of the items that are outlined in<br />

the PCL-R and that are generally agreed upon<br />

in psychiatry. However Hare himself, and<br />

many others in the field, have established<br />

that ASPD is not an apt depiction of what can<br />

commonly be understood as psychopathy.<br />

[9]<br />

Hare and others central to understandings<br />

of psychopathy had made clear that affective<br />

traits, like selfishness, egocentrism, and a lack<br />

of empathy, were fundamental to the<br />

diagnosis. However in the DSM-III, published<br />

in 1980, ASPD was instead characterized<br />

primarily by the ways in which social norms<br />

were broken, such as lying, stealing, and even<br />

traffic arrests, diminishing these traits that<br />

so many saw as crucial. [9] This definition was<br />

also far too broad to constitute psychopathy<br />

as established by other tests and ideas. While<br />

most that are understood to be psychopaths<br />

meet the criteria for ASPD, most people with<br />

ASPD are not actually psychopaths by this<br />

same popular criteria. [9] As it stands, only one<br />

in five people with ASPD could fit a diagnosis<br />

of psychopathy. [10]<br />

And yet, many believe psychopathy to<br />

be a finalized diagnosis supported by<br />

psychiatric certainty, immediately indicative<br />

of an individual’s character. This perception<br />

has been largely influenced by negative<br />

media portrayals, in which psychopaths are<br />

often cast in villainous roles. While these<br />

depictions may ring a vaguely relative<br />

truth—yes, Hannibal Lecter is a psychopath<br />

according to all of the previously mentioned<br />

tests—they are largely overly dramatic, and<br />

imply traits and behaviours that are not<br />

actually associated with psychopathy.<br />

“At the very least the media should<br />

show both sides of psychopathy, not just<br />

showing them as cold-blooded murderers.<br />

Psychopathy does not mean criminality”<br />

clarified Guillaume Durand, a PhD candidate<br />

in neuroscience at Maastricht University.<br />

“[Media] don’t show that there is actually<br />

very little agree ment on what psychopathy<br />

is.”<br />

In 2013, two Belgian psychiatrists<br />

addressed how movies portrayed so-called<br />

psychopaths. They studied over 400 films<br />

released between 1915, beginning with<br />

Birth of a Nation, and 2010, ending with The<br />

Lovely Bones, all of which included a villain<br />

that was portrayed as a psychopath. [11] The<br />

psychiatrists had to eliminate all but 126 of<br />

these films, because most of the portrayals<br />

were “too caricatured and or too fictional” to<br />

constitute even a vaguely correct reflection<br />

of psychopathy. This in itself is a powerful<br />

reflection of how movies choose to portray<br />

psychopathy. What they identify as the<br />

“Hollywood psychopath” encompasses a<br />

variety of symptoms not typical with<br />

psychopathy, including high intelligence,<br />

fascination with fine arts, obsessive<br />

behaviour, and exceptional capacity for<br />

violence and killing. [11] They also clarified<br />

that most characters largely associated with<br />

psychopathy, like Norman Bates from Psycho,<br />

actually suffer from psychosis, which is a<br />

disconnect with reality, not a personality<br />

disorder. [3] The study praised Anton Chigurh<br />

from No Country for Old Men, Henry from<br />

Henry - Portrait of a Serial Killer and Gordon<br />

Gekko from Wall Street for being more<br />

"Psychosis is a disconnect<br />

with reality, not a<br />

personality disorder."<br />

accurate and insightful views on psychopathy.<br />

[11]<br />

“Usually more representation is always<br />

positive—people always fear what they don’t<br />

know. But [the media] only gives one side”<br />

10 11

said Durand.<br />

Psychopathy<br />

This may have adverse effects on not<br />

only interpretation, but actual treatment and<br />

professional relation to psychopathy. Matthew<br />

Burnett, a psychology graduate student<br />

from the University of Saskatchewan, published<br />

a dissertation in 2013 on how psychopathy<br />

as portrayed in Canadian media (in<br />

this case news sources) may adversely affect<br />

widespread interpretation. [12] He found that<br />

news representation often sensationalize<br />

stories regarding psychopaths, and that this<br />

leads to popular misinterpretation of the<br />

disorder, and popular expressions of doubt<br />

over potential for reform. He also found that<br />

media sources overwhelmingly associate psychopathy<br />

with violence and dangerousness.<br />

In sampling a prison, inmates, correctional<br />

officers, and staff interviewed all maintained<br />

“highly negative, distorted, and damning<br />

[views]” of psychopathy. Because prisons are<br />

largely intended to rehabilitate in Canada, [13]<br />

this is only made more disturbing.<br />

“My definition [of a psychopath] is an<br />

individual that lacks remorse, who is in poor<br />

control of their actions, is guiltless and dishonest,<br />

but can also display positive traits,<br />

like fearlessness and painlessness” said<br />

Durand.<br />

References:<br />

[1] Kiehl, K., & Lushing, J. (2014). Psychopathy. Scholarpedia,<br />

9(5), 30835. dx.doi.org/10.4249/scholarpedia.30835<br />

[2] Crego, C., & Widiger, T. A. (2016). Cleckley’s psychopaths:<br />

Revisited. Journal of Abnormal Psychology,<br />

125(1), 75-87. Retrieved from http://myaccess.library.<br />

utoronto.ca/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/<br />

docview/1738484647?accountid=14771<br />

Alexa Battler<br />

[3] Stover, A. (2007). A critical analysis of the historical and<br />

conceptual evolution of psychopathy.<br />

[4] The Psychopathy Checklist - Doc Zone - CBC-TV. (2016).<br />

CBC. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/doczone/features/<br />

the-hare-psychotherapy-checklist<br />

[5] Davey, K. (2013). Psychopathy and sentencing: An investigative<br />

look into when the PCL-R is admitted into Canadian<br />

courtrooms and how a PCL-R score affects sentencing<br />

outcome. Western Graduate & Postdoctoral Studies.<br />

[6] Miller, J. & Lynam, D. (2012). An examination of the<br />

Psychopathic Personality Inventory’s nomological network:<br />

A meta-analytic review. Personality Disorders: Theory,<br />

Research, And Treatment, 3(3), 305-326. http://dx.doi.<br />

org/10.1037/a0024567<br />

[7] Miller, J., Jones, S., & Lynam, D. (2011). Psychopathic<br />

traits from the perspective of self and informant reports: Is<br />

there evidence for a lack of insight? Journal Of Abnormal<br />

Psychology, 120(3), 758-764. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/<br />

a0022477<br />

[8] Personality disorders. (2012). American Psychiatric<br />

Association DSM-5 Development. Retrieved from http://<br />

www.dsm5.org/Documents/Personality%20Disorders%20<br />

Fact%20Sheet.pdf<br />

[9] Hare, R. (1996). Psychopathy and Antisocial Personality<br />

Disorder: A Case of Diagnostic Confusion. Psychiatric<br />

Times. Retrieved 22 September 2016, from http://www.<br />

psychiatrictimes.com/antisocial-personality-disorder/psychopathy-and-antisocial-personality-disorder-case-diagnostic-confusion<br />

[10] Herstein, W. (2016). What Is a Psychopath? Psychology<br />

Today. Retrieved from http://www.psychologytoday.com<br />

[11] Perry, S. (2013). Why psychopathic film villains are<br />

rarely realistic — and why it matters. MinnPost. Retrieved<br />

from https://www.minnpost.com/second-opinion/2014/01/<br />

why-psychopathic-film-villains-are-rarely-realistic-and-whyit-matters<br />

[12] Burnett, M. (2013). Psychopathy: Exploring canadian<br />

mass newspaper representations thereof and violent<br />

offender talk thereon (Graduate). University of Saskatchewan.<br />

[13] About Canada’s Correctional System. (2015). Public<br />

Safety Canada: Government of Canada. Retrieved from<br />

http://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/cntrng-crm/crrctns/btcrrctnl-sstm-en.aspx<br />

“Trying to Save You”<br />

MUSIC<br />

1st Place - UTSC<br />

1st Place - National<br />

by Nitha Vincent<br />

“Rope”<br />

by How do I know that I’m Alive (University of Toronto, St. George)<br />

12<br />

13

Trying to<br />

Save You<br />

By Nitha Vincent<br />

Rope<br />

By How do I know that I’m Alive<br />

Graphic by Phoebe Maharaj<br />

For this contest, I submitted a piece called Trying To Save You. I wrote the song myself and also<br />

did both the vocals and guitar. I wrote this piece in 2012, when I was 14, and wanted it be be a<br />

sort of pick-me-up whenever I felt unhappy or upset. Over the years, I’ve edited the lyrics, but<br />

most of the song is still the same. In 2015, I performed this song at my high school, Cedarbrae<br />

Collegiate Institute, at an anti-bullying assembly we were having, as a tribute to all the people<br />

who have been bullied. I wrote this song to console anyone who is having a bad day and to<br />

remind them that things do get better and to not give up. I’m very glad to have this opportunity<br />

to showcase my piece and I’m very excited to have all of you listen to it.<br />

Nitha Vincent<br />

1 st Place UTSC Winner<br />

Music<br />

Nitha Vincent is an aspiring singer/songwriter<br />

in her first year, and is studying psychology at<br />

the University Of Toronto Scarborough Campus.<br />

Nitha has been singing since the age of<br />

five, became a self-taught guitarist at 14, and<br />

has been writing songs for five years. Nitha<br />

feels that songwriting has always been a very<br />

important outlet to freely and safely express<br />

and describe their feelings, whatever they<br />

may be.<br />

Graphic by Phoebe Maharaj<br />

The song is about hiding pieces of your mental health from a partner and the inevitable issues<br />

that arise from navigating whether to disclose or not. The song is left ambiguous to allow the<br />

listener to place themselves in the shoes of both individuals involved in the relationship. The<br />

ambiguousness allows the listener to focus on the tension between the relationship, rather<br />

than the individuals themselves. This causes the listener to sit with the shame that both parties<br />

are experiencing. This is intended to create an empathetic connection towards the emotionality<br />

surrounding the moment of tension, rather than the individuals involved. The song is titled<br />

Rope because the artist wanted to create imagery that highlighted tension that is created<br />

within the relationship. Eventually the song ends, highlighting the tension in the rope, leaving<br />

the listener to question the fine balance of staying connected or disconnected to both the relationship<br />

and one’s mental health.<br />

How do I know that I’m Alive<br />

1 st Place National Winner<br />

Music<br />

“How do I know that I’m Alive” is working towards<br />

a master of social work at the University<br />

of Toronto. They are currently employed as<br />

a program coordinator at a recreation centre<br />

for senior citizens. Their interests include<br />

research in social work, harm reduction, approaches<br />

to addiction, and post-structuralism.<br />

14 15

Minds Matter Magazine Volume II Issue I Arts & Media<br />

Angels and Demons Within:<br />

Exploring the Meaning of Hearing Voices<br />

By Ioana Arbone<br />

Illustration by Adley Lobo<br />

Academic studies conducted in Europe, New<br />

Zealand, and America during the past 20 ears<br />

have shown that a significant minority of the<br />

world population—5% to 13%—hear voices<br />

that other people cannot [1] . This statistic includes<br />

people who do and do not suffer from<br />

a related physical or mental illness. [1]<br />

It is difficult to describe what it means<br />

to hear voices, because the experience comes<br />

in many different forms—so much so that<br />

to describe them as ‘voices’ is inaccurate for<br />

many who experience them. [2] In a mass, multifaceted<br />

study published in 2015, voice-hearers<br />

were interviewed in order to better understand<br />

their varying experiences. [2] Some<br />

participants described hearing a distinct voice<br />

of someone standing next to them, while<br />

others described experiencing very realistic<br />

thoughts rather than distinct articulations.<br />

[2]<br />

As well, some described hearing a single<br />

voice, while others described hearing multiple<br />

voices. [2]<br />

‘Voices’ itself is not an entirely accurate<br />

term, as voices do not have to be distinct<br />

linguistic expressions of a human. They may<br />

also be sounds, other forms of articulations,<br />

ideas, and can come in many other forms<br />

than voices. [2] In each of these instances, the<br />

voices are interpreted by the hearer as something<br />

foreign, coming from a source outside<br />

of themselves, and as different from a regular<br />

inner dialogue, but are heard only by themselves.<br />

[2]<br />

In current clinical psychiatry, the term<br />

“auditory hallucination” is used to describe<br />

the experience of hearing voices. [3] However,<br />

Dr. Rufus May, a clinical psychologist from<br />

Britain, clarified that the term “hearing<br />

voices” more accurately expresses the personal<br />

experiences of voice-hearers. “Hearing<br />

voices” is also the preferred term of the<br />

the International Hearing Voices Network, a<br />

UK-based charity that fights to change perception<br />

of voice-hearing as an exclusive sign<br />

of mental illness, or as an automatically negative<br />

occurrence. [4] They feel that the term<br />

‘hallucination’ “is inaccurate as it gives the<br />

impression that the experience is unreal and<br />

meaningless.” [4]<br />

“More often than not, hearing<br />

voices is deeply personal, and<br />

many healthy and creative<br />

people experience them.”<br />

It is not currently known why these<br />

voices occur. There is research suggesting that<br />

voice-hearers tend to experience high levels<br />

of chronic stress in their lives, especially in<br />

their childhoods. [5] But voice-hearing is not a<br />

random experience completely unrelated to<br />

the hearer’s past or present life. More often<br />

than not, hearing voices is deeply personal,<br />

and many healthy and creative people experience<br />

them [13, 14, 15] . Neuroscientific studies<br />

also suggest that voice-hearing experiences<br />

arise in the right hemisphere of the brain, and<br />

that voice-hearing is possibly more likely for<br />

those who engage in activities dependent on<br />

this hemisphere, such as “music, art, poetry<br />

and spatial math skills”. [16] Such connections<br />

between creative activities and the way the<br />

brain works may partly explain why artists<br />

sometimes hear realistic voices, or feel creatively<br />

influenced by realistic perceptions or<br />

ideas.<br />

16<br />

17

Angels and Demons<br />

Ioana Arbone<br />

Minds Matter Magazine Volume II Issue I Arts & Media<br />

One study of 15,000 voice-hearers<br />

suggested that one in three people who hear<br />

voices has a psychiatric disorder, whereas two<br />

out of three fit no diagnosis for mental illness.<br />

The study also found that the main difference<br />

between those with and without mental<br />

health diagnoses was their relationship to<br />

their voices. [8] Individuals diagnosed with psychiatric<br />

disorders tended to report that their<br />

voices were critical, malevolent, and frighten<br />

ing. However, individuals that had not been<br />

diagnosed with psychiatric conditions more<br />

often (but not exclusively) reported that their<br />

voices were kind, encouraging, and benevolent.<br />

[8] Despite this, hearing voices can be a<br />

frightening experience, and can lead one to<br />

feel as though they are ‘losing their mind’.<br />

[9]<br />

Yet this fearful reaction is not always the<br />

case, and often seems to be particular to<br />

Western culture. This has been evidenced in a<br />

cross-national comparative study conducted<br />

by Stanford University in San Mateo, America,<br />

the Schizophrenia Research Foundation in<br />

Chennai, India, and the Accra General Psychiatric<br />

Hospital in Ghana, Africa. The three<br />

institutions published the study in 2015, to<br />

explore the experiences of hearing voices<br />

across each of these different cultures. [10]<br />

The study found that Americans often<br />

used distinctly psychiatric language to describe<br />

their experiences, well-evidenced in<br />

one participant’s depiction: “I fit the textbook<br />

on Schizophrenia.” These participants also<br />

more often said that hearing these voices<br />

were very negative experiences, including<br />

hearing “screaming, fighting…[and voices saying]<br />

jump in front of the train.” Meanwhile,<br />

the individuals from India and Africa reported<br />

less violent voices. Citizens of Accra uniquely<br />

perceived hearing voices as the result of spiritual<br />

forces contacting them, and their experiences<br />

appeared overwhelmingly positive.<br />

One individual even stated: “[the voices] just<br />

tell me to do the right thing. If I hadn’t had<br />

these voices, I would have been dead long<br />

ago.”<br />

The sample from Chennai reflected a<br />

balance of positive and negative perceptions<br />

of the voices. Unlike the individuals from San<br />

Mateo and Accra, 11 out of 20 voice-hearers<br />

from Chennai said the voices were of relatives<br />

who had died. These relatives reportedly<br />

made both critical and helpful comments.<br />

For example, one man heard the voices of his<br />

deceased sisters, which would would mock<br />

him at times, yet would also remind him to<br />

engage in certain mundane and healthy activities,<br />

like bathing. Eight of the 20 individuals<br />

studied from Chennai experienced the voices<br />

as highly positive.<br />

“just as dreams can inform us<br />

about our wishes and our<br />

challenges, so can voices.”<br />

But why are these interpretations so<br />

different across nations? One possibility is<br />

that differences in culture lead to different<br />

views of how the voice-hearing itself is commonly<br />

perceived by others. It seems that<br />

Western culture views individuals as being<br />

completely separate from one another, while<br />

other cultures (e.g. sub-Saharan Africanculture)<br />

place more importance on community,<br />

and interpersonal interaction. [10] This<br />

Western, individualistic perspective also<br />

ends to view private thoughts, emotions, and<br />

perceptions as purely biological events occurring<br />

solely within a human body. [10] Therefore,<br />

hearing voices that no one else hears tends to<br />

be seen as a problem arising within the individual,<br />

instead of the consideration that there<br />

might be something that exists that other<br />

individuals cannot perceive.<br />

In Western culture, hearing voices has<br />

no meaning,” says Dr. John Read, a clinical<br />

psychologist at the University of Auckland,<br />

New Zealand.<br />

Indeed, according to the Diagnostic<br />

and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders<br />

(DSM-V), the only meaning they have is that<br />

they could indicate a psychological disorder.<br />

However, these experiences are deeply personal,<br />

and these voices express and reflect<br />

ideas and attitudes. As such, they can offer<br />

the voice-hearer an alternate perspective, or<br />

new ideas around dealing with life events.<br />

Dismissing these voices as devoid of any<br />

useful information, and claiming that they are<br />

indicative of a mental illness without looking<br />

at the content of the voices, may lead one to<br />

avoid addressing important concepts.<br />

Vanessa Beaven, a clinical psychologist,<br />

interviewed 50 voice-hearers in an attempt to<br />

understand what deeper meanings the voices<br />

may carry. [11] Most of the people interviewed<br />

described the content of the voices as personally<br />

meaningful, and saw connections between<br />

what they were going through during<br />

that time and the voices’ comments. Many<br />

of them also had a personal relationship with<br />

the voices, similar to the relationships one<br />

has in everyday life. The voices seemed<br />

real to the participants, and, in this study,<br />

they were able to identify them as specific<br />

people or characters, such as a parent, a<br />

grandparent, a friend, a demon, or God. Participants<br />

also said that hearing voices impacted<br />

them emotionally, in positive and negative<br />

ways.<br />

“crisitunity - an event can be both<br />

a crisis and an opportunity.”<br />

Interpretations of voices can greatly<br />

influence what they mean to the voice-hearer.<br />

Dr. Simon McCarthy-Jones, an established<br />

researcher and author in the field of<br />

voice-hearing, recounted an example of these<br />

underlying meanings in his book, Hearing<br />

Voices. He detailed a conversation with Dr.<br />

Marius Romme, another well-known researcher<br />

and a prominent scholar in the study<br />

of voice-hearing. Romme explained the story<br />

of an individual who heard a voice repeatedly<br />

saying, “you might as well be dead”. [12]<br />

After exploring his experience, and reflecting<br />

on the meaning of voices, the voice-hearer<br />

understood that the voice was actually<br />

telling her that she was not taking care of<br />

herself enough, and that, if this continued,<br />

she “might as well be dead”. [12] As McCarthy-Jones<br />

says, “Voices may thus help us find<br />

parts of ‘ourselves’ which we cannot consciously<br />

access, and further study of this may<br />

help shed light on the creative process”. [12]<br />

As well, Dr. May suggests that hearing<br />

voices is similar to dream analysis; just as<br />

dreams can inform us about our wishes and<br />

our challenges, so can voices. [9] Similarly,<br />

18 19

Angels and Demons<br />

Ioana Arbone<br />

dreams can also be created narratives based<br />

on one’s own life, and paying attention to<br />

their content may be helpful and telling - at<br />

least for some people. Of note is that the<br />

voice-hearers themselves are generally able<br />

to differentiate when hearing voices disrupts<br />

their lives versus when these voices are not a<br />

problem and may even be helpful. [9]<br />

So, what should we do if we or a loved<br />

one hear voices? Both Dr. John Read and Dr.<br />

Rufus May suggest not to be afraid and to<br />

try and understand the experience. Dr. Rufus<br />

May also says that curiosity is a best friend in<br />

this situation, and mentions the word “crisitunity<br />

” – a word he invented – to show that an<br />

event can be both a crisis and an opportunity.<br />

Dr. John Read says that those who hear voices<br />

need to show interest in them, and view<br />

them as a normal variation of human experience.<br />

References:<br />

[1] Beavan, V., Read, J., & Cartwright, C. (2011). The<br />

prevalence of voice-hearers in the general population: A<br />

literature review. Journal of Mental Health, 20, 281–292.<br />

doi:10.310 9/09638237.2011.562262.<br />

[2] Woods, A., Jones, N., Alderson-Day, B., Callard, F. and<br />

Fernyhough, C. (2015). Experiences of hearing voices:<br />

analysis of a novel phenomenological survey. The Lancet<br />

Psychiatry, 2(4), pp.323-331.<br />

[3] Moskowitz, A. & Corstens, D. (2007). Auditory hallucinations:<br />

Psychotic symptom or dissociative experience? The<br />

Journal of Psychological Trauma, 6(2/3), 35-63.<br />

[4] CYMRU, Hearing Voices Network, Wales. (2016, August<br />

13). Hearing Voices Network. Retrieved from: http://hearingvoicescymru.org/positive-voices/famous-voice-hearers/<br />

creative-people<br />

[5] Read, J., Perry, B.D., Moskowitz, A. & Connolly, J. (2001).<br />

The contribution of early traumatic events to schizophrenia<br />

in some patients: A traumagenic neurodevelopmental model.<br />

Psychiatry, 64(4), 319-345.<br />

[6] Shergill, S. S., Brammer, M. J., Williams, S. C., Murray, R.<br />

M., & McGuire, P. K. (2000). Mapping auditory hallucinations<br />

in schizophrenia using functional magnetic resonance<br />

imaging. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57(11), 1033-<br />

1038.<br />

[7] Tien, A.Y. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol (1991) 26:<br />

287. doi:10.1007/BF00789221.<br />

[8] Honig, A., Romme, M. A. J., Ensink, B. J., Escher, S. D.<br />

M. C., Pennings, M. H. A., & Devries, M. W. (1998). Auditory<br />

hallucinations; a comparison between patients and<br />

nonpatients. Journal of Mental and Nervous Disease, 186,<br />

646 - 651.<br />

[9] Kalhovde, A. M., Elstad, I., & Talseth, A. G. (2014).<br />

“Sometimes I walk and walk, hoping to get some peace.”<br />

Dealing with hearing voices and sounds nobody else hears.<br />

International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and<br />

Well-being, 9(1). doi:10.3402/qhw.v9.23069.<br />

[10] Luhrmann, T. M., Padmavati, R., Tharoor, H., & Osei,<br />

A. (2015). Hearing Voices in Different Cultures: A Social Kindling<br />

Hypothesis. Topics in Cognitive Science, 7(4), 646-663.<br />

doi:10.1111/tops.12158.<br />

[11] Beavan, V. (2011). Towards a definition of “hearing<br />

voices”: A phenomenological approach. Psychosis, 3(1),<br />

63-73.<br />

[12] McCarthy-Jones, S. (2013). Chapter 12 - The Struggle<br />

for Meanings. In S. McCarthy-Jones, Hearing Voices: The<br />

Histories, Causes and Meanings of Auditory Verbal Hallucinations<br />

(pp. 315-354). USA: New York: Cambridge University<br />

Press.<br />

[13] Ability Magazine. (2016, August 13). Brian Wilson —<br />

A Powerful Interview. Retrieved from Ability Magazine:<br />

http://www.abilitymagazine.com/past/brianW/brianw.html<br />

[14] CYMRU, Hearing Voices Network, Wales. (2016, August<br />

13). Creative People including writers, artists and musicians.<br />

Retrieved from CYMRU, Hearing Voices Network,<br />

Wales: http://hearingvoicescymru.org/positive-voices/<br />

famous-voice-hearers/creative-people<br />

[15] Carson, S. H., Peterson, J. B., & Higgins, D. M. (2003).<br />

Decreased Latent Inhibition Is Associated With Increased<br />

Creative Achievement in High-Functioning Individuals. Journal<br />

of Personality and Social Psychology, 499-506.<br />

[16] de Leede-Smith, S., & Barkus, E. (2013). A comprehensive<br />

review of auditory verbal hallucinations: Lifetime<br />

prevalence, correlates and mechanisms in healthy and<br />

clinical individuals. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience(JUN).<br />

doi:10.3389/fnhum.2013.00367<br />

“Dysthymia”<br />

1st Place - UTSC<br />

1st Place - National<br />

by Sara Farhat<br />

“An Open Letter to My Family”<br />

by Sabnam Mahmuda (McMaster University)<br />

“The Orange”<br />

2nd Place - National<br />

by m. Rana (University of Guelph)<br />

3rd Place - National<br />

“My Letter to Gaddy”<br />

by Shannon Hui (York University)<br />

Honourary Mentions<br />

“At Song’s End”<br />

by Cassandra Chen (University of Ontario Institute of Technology)<br />

“Closed Book”<br />

POETRY<br />

by Ross Rosales (George Brown College)<br />

20<br />

21

Minds Matter Magazine Volume II Issue I Arts & Media<br />

They murmur and screech,<br />

Pounding at her skull.<br />

Etching black dog graffiti,<br />

Staining mind in a charcoal tinge.<br />

Walls closing in,<br />

Trapped in a cage built by her.<br />

Air unable to break the shackles,<br />

Lungs squeezing against her rib cage<br />

Dysthemia<br />

By Sara Farhat<br />

The poem I wrote called Dysthymia is about a person who suffers from depression. I’ve been<br />

learning about mental illness in my classes, and I just wanted to take what I study and put it<br />

into words. I really like both science and art, I like to combine the two. That kind of unity is<br />

needed; it creates wonder, and that is what inspired me to write this poem. I wanted to try<br />

something new, take on the perspective of someone who has depression, and explain to the<br />

readers how it feels for someone who lives with this condition - that this is real and can really<br />

ruin a person’s quality of life. We need to be aware of these things and really go on in understanding<br />

and giving a helping hand, and treating mental illness just like any other physical<br />

illness.<br />

Entrapped within her caged bones,<br />

Slamming on the walls trying to<br />

escape. The darkness, spreading as she<br />

suffocates<br />

“You’re not good enough.”<br />

“Worthless, helpless, failure.”<br />

These negative thoughts eating away at<br />

her flesh, feeding the demons.<br />

Snap out of it! If only it was that easy<br />

Curtains closed, clips of everything she<br />

despises about herself project at the<br />

back of her eyes<br />

Photograph by Adley Lobo<br />

The demons, shrieking demons<br />

Broken record voices; on repeat<br />

Taunting and teasing,<br />

Delightful dopamine; their hostage<br />

Trembling hands grab a hold of pills,<br />

Pills silencing the monsters<br />

Leaving her lethargic mind,<br />

only to desire sleep.<br />

Drowning all her thoughts,<br />

In a long heavy slumber.<br />

Sara Farhat<br />

1 st Place UTSC Winner<br />

Poetry<br />

Sara Farhat is working towards a double<br />

major in neuroscience and psychology at the<br />

University of Toronto Scarborough. Sara describes<br />

herself as an ordinary girl who enjoys<br />

the little things that life has to offer. I hold on<br />

to that little kid at heart inside of me, letting<br />

my imagination always run wild.”<br />

22<br />

23

Minds Matter Magazine Volume II Issue I Arts & Media<br />

But<br />

You tiptoe around the shadows which bloom within me like wildflowers.<br />

An<br />

Open Letter<br />

to<br />

My Family<br />

By Sabnam Mahmuda<br />

My poem, an open letter to my family, is an attempt to showcase depression through the lens<br />

of culture and family. Perception of those who are close to us can tremendously impact our experience<br />

with depression. From my own experience as a young South Asian woman, I have seen<br />

how truly difficult it is to lend a voice to explain and to understand the non-physical manifestations<br />

of depression upon the body. This is due to the fact that South Asian cultures highly value<br />

endurance and in an attempt to do so, overlook the fact that some illnesses simply cannot be<br />

battled by the force of our willingness to ignore it. This poem is merely my way of portraying<br />

how depression is misperceived in my culture as a non-existent and pretentious illness which is<br />

used as an excuse to escape academic commitments by those who are weak.<br />

Dear baba,<br />

You say to have faith in God to help me through the darkness<br />

But how do I explain to you,<br />

That I can’t even have faith in myself,<br />

Much less in a spirit I’ve never seen.<br />

But<br />

You watch me go through the motions to maintain an illusion of happiness.<br />

Dear ma,<br />

You say that it’s my negativity which is to blame for everything<br />

But how do I explain to you,<br />

That I do not control anything but it controls me<br />

It holds me tight and rocks me to numbness every night.<br />

Photograph by Adley Lobo<br />

Dear brother,<br />

Your say that I am bringing shame to our family name<br />

But how do I explain to you,<br />

That I am not pretending to be sick or staying silent as an act of rebellion<br />

Sometimes my skin feels so tight that it chokes me and sometimes my<br />

skin feels so loose that it drowns me<br />

But<br />

You glance away from me as if in disgust.<br />

Dear my love,<br />

You do not say anything to me<br />

But how do I explain to you,<br />

That when we are together I desperately crave tender words<br />

To pry free my mind from the fist cuffs of fear<br />

But<br />

You remain willingly silent as the void between us continue to grow.<br />

Shanam Mahmuda<br />

1 st Place Nation Winner<br />

Poetry<br />

Sabnam Mahmuda is a graduate student in<br />

health studies at McMaster University, and<br />

an aspiring writer and artist. Sabnam finds<br />

inspiration in nature and in others’ stories<br />

observed during work or while travelling.<br />

Through written and visual art, Sabnam communicates<br />

stories of their own experiences,<br />

and of people who have touched her life.<br />

24<br />

25

Minds Matter Magazine Volume II Issue I Arts & Media<br />

The Orange<br />

By m.Rana<br />

This poem is about identity and, really, what it means to be a person. It was inspired after<br />

facilitating several sessions of group therapy. I saw that each individual has many layers which<br />

makes up who they are, and with each layer there is meaning and there is purpose.<br />

Covered in my own colour<br />

My name is who I am<br />

Orange<br />

Thick skinned and hardened<br />

From the passing of seasons<br />

I have survived days of light and days of darkness<br />

But, I was picked before I was ready to fall<br />

Squeezed to see my strength<br />

Touched and scanned for blemishes and scars<br />

What would you have done if you found any?<br />

I am just the right feel for you<br />

Your appetite craves more<br />

You wish to see what’s inside, and uncover me for who I<br />

am<br />

Digging your thumb deep into my core<br />

Alas you have ripped and torn what was holding me<br />

together<br />

Peeling away peeling away<br />

Piece by piece<br />

Ripping me apart<br />

All that keeps me together, ripping me apart<br />

Photograph by Adley Lobo<br />

Let’s call this first piece memories<br />

Lines and lines of conversations<br />

Tales of being together and letting go<br />

Longing, wanting, desiring Smiling, laughing, crying<br />

Loving, breaking, healing<br />

This isn’t enough for you to swallow<br />

Once again, digging your thumbs deep into my core<br />

Ripping me apart<br />

Let’s call this second piece guilt<br />

For the pain that I may have caused<br />

And the pain that I may have felt<br />

For following my heart, and not following it<br />

It should have never been this way<br />

Yet it was the only way<br />

It all comes in pairs, and never leaves as one<br />

Half way there and you still want more<br />

Digging your thumbs deep into my core, once again<br />

Ripping me apart<br />

Let’s call this one anger<br />

Why is it like this?<br />

Unable to control my fate<br />

Slowly slipping away, one piece at a time<br />

More more more, only once more<br />

Digging deep into my soul<br />

And all that is left of me, is fear<br />

Fear of being alone, empty, naked<br />

Uncovered in my own element<br />

My name is who I am<br />

Orange<br />

- therapy<br />

m. Rana<br />

2 nd Place UTSC Winner<br />

Poetry<br />

m.Rana graduated from the University of Toronto Scarborough in 2015 with a<br />

bachelors of science in psychology, specializing in mental health and neuroscience.<br />

m.Rana then completed a graduate certificate in addictions and mental health<br />

from Durham College, and will now be pursuing a masters of science in couples and<br />

family therapy. Their primary interests are education, psychology, and romance.<br />

26<br />

27

My Letter<br />

to<br />

Gaddy<br />

Minds Matter Magazine Volume II Issue I Arts & Media<br />

Dear Gaddy,<br />

Comes spring melting the bitter cold away,<br />

Yet the ice in your soul has a permanent stay.<br />

You answer its call several times again,<br />

through dancing encounters of silver and<br />

flesh,<br />

but to only be ashamed by the summer sun.<br />

By Shannon Hui<br />

Photograph by Adley Lobo<br />

Dear Gaddy,<br />

Comes summer with a hot, heavy burden<br />

that locks your wrists in chains.<br />

Unable to escape the glaring stares,<br />

You merely hide under long sleeves of cotton,<br />

Waiting for fall to return.<br />

My work, My Letter To Gaddy, is a poem inspired by a personal connection with a friend. It illustrates<br />

the experiences and feelings of an individual who is depressed, and seeks relief through<br />

self harm. As the seasons pass, the individual encounters various difficulties, as they battle with<br />

their mental health. My hope is that this poem will inspire others to reach out to those with<br />

mental illnesses, to show them the simple beauty of life. In use and comparison of the seasons,<br />

I wish to open a window of awareness to increase both understanding and awareness of the<br />

lives of individuals struggling with mental health. I hope that the voice of this letter will not<br />

reach only “Gaddy,” but many others, as issues surrounding mental health are not ones which<br />

can simply be overcome alone, but must be conquered together.<br />

Dear Gaddy,<br />

Comes fall with yellow, orange and red,<br />

But blind you are, as you meet again,<br />

The weight of silver upon your wrist,<br />

Yearning warmth from the red droplets freed,<br />

To only be embraced by the cold of winter.<br />

Dear Gaddy,<br />

Comes winter with the cold of day,<br />

A sensation of a familiar experience,<br />

Which is difficult to ever grow accustomed.<br />

In search of relief from this path astray,<br />

You yearn for the warmth of spring.<br />

Dear Gaddy,<br />

Comes fall, winter, spring and summer.<br />

Such simple things the seasons are,<br />

Yet their beauty lies hidden past you.<br />

So I leave my love, my heart and my soul,<br />

To rest side by side to heal the scars you hold.<br />

Shannon Hui<br />

3 rd Place National Winner<br />

Poetry<br />

Shannon Hui is in her second year of the bachelor<br />

of business administration program at<br />

York University. Shannon says that her journey<br />

surrounding mental health is merely beginning,<br />

as she continue to meet new people and<br />

experience different things, all while trying to<br />

learn the importance of being healthy, both<br />

mentally and physically.<br />

28<br />

29

Minds Matter Magazine Volume II Issue I Arts & Media<br />

Creative Works Studio:<br />

Art and Community for Health<br />

By Ioana Arbone, assisted by Karen Young<br />

Photograph by Marlena Zuber<br />

Some bands are born of positive beginnings. Social Mystics is no exception. Born in 2007, this<br />

group was developed by the arts-based occupational therapy program, the Creative Works<br />

Studio (CWS).<br />

Situated in Toronto, CWS is run by St. Michael’s Hospital, in partnership with the Good<br />

Shepherd Non-Profit Homes Inc. They offer therapeutic arts programming to those struggling<br />

with mental illness and addiction issues.<br />

CWS serves between 80 and 100 members<br />

and hosts 2,500 visits per year. While the<br />

hospital finances approximately 40 percent of<br />

the studio, CWS self-finances the remaining<br />

60 percent. Clients can be referred to CWS<br />

by a health care provider from across Toronto,<br />

though priority is given to clients from St.<br />

Michael’s Hospital. The music group Social<br />

Mystics is just one example of the many CWS<br />

projects.<br />

Apart from participating in larger projects<br />

like the Social Mystics, CWS clients can<br />

find their passion by choosing from a variety<br />

of art forms, including pottery, painting,<br />

sculpture, songwriting, screen printing and<br />

digital photography.<br />

Minds Matter Magazine interviewed<br />

the founder and creative lead of CWS, Isabel<br />

Fryszberg. She is also the creative lead of<br />

band, musical compositions, and rhythm guitar<br />

at Social Mystics. Social Mystics launched<br />

their first album, Coming Out of Darkness, in<br />

early March of this year.<br />

Minds Matter Magazine (MMM): Why the<br />

name Social Mystics?<br />

Isabel Fryszberg (IF): In our group, we collectively<br />

inspire each other and build on each<br />

other’s ideas. One day, someone said ‘oh<br />

yeah, we are the social misfits,’ and then the<br />

word mystic came up and everybody said,<br />

‘yeah, that is a good name.’ In our group, you<br />

sometimes create unconsciously, in that your<br />

ideas, your thoughts and images, are ahead<br />

of you. When you think about Social Mystics,<br />

it is that we are, in many ways, providing a<br />

message that is not always understood or<br />

clear to people. But when we do present our<br />

message, whether it is through music, film, or<br />

art, photography, we appreciate it.<br />

MMM: What are some of the important ideas<br />

that are in your songs?<br />

IF: There are a lot of different messages that<br />

we have, such as acceptance, compassion,<br />

and community. Some of our music is nostalgic<br />

in the style of the melodies, so it kind of<br />

transports you in another time. In “I Could<br />

Build a New World”, we say in the lyrics what<br />

is important. We talk about love, we talk<br />

about talking to each other rather than texting<br />

and being so focused on our iPhones. We<br />

talk about smiling to each other, connecting,<br />

moving slower, breathing with ease. We also<br />

say, ‘hold on to the good.’ When you are dealing<br />

with a mental health challenge, it is hard<br />

to hold on to the good, especially when you<br />

are contemplating hurting yourself or suicide.<br />

So, we say it in the first line, ‘when the world<br />

tears you apart, hold on to the good.’<br />

Photograph by Ioana Arbone<br />

MMM: How do you create that space of mutual<br />

acceptance?<br />

IF: This is done partly over time and partly by<br />

being nonjudgmental. We create a sense of<br />

30<br />

31

Creative Works Studio<br />

Ioana Arbone<br />

Minds Matter Magazine Volume II Issue I Arts & Media<br />

safety, where everybody’s ideas are encouraged,<br />

and we play a lot. It is about how can<br />

we really make an interesting art piece with<br />

this song. Together.<br />

MMM: At CWS, artists can create art through<br />

different mediums. How does the artist decide<br />

which art form they go with? How are<br />

people exposed to the different art forms so<br />

that they are able to choose which one to go<br />

with?<br />

IF: The artists have the opportunity to try<br />

anything. We operate as an open studio. We<br />

have structured programs that people can<br />

participate in. Some are with instruction and<br />

some are not. We work right where someone<br />

is at. People are exposed to music who have<br />

never sang. In this studio, we could have clay<br />

going on, painting going on, and singing going<br />

on at the same time. It is done in a way so<br />

that people are focused on what they are doing.<br />

While some people are painting, they are<br />

hearing live music. There is this lovely back<br />

and forth thing going on. Today, people are<br />

picking up colouring books.This whole studio<br />

is about colouring, and creating, and being<br />

in that kind of zen place. But the difference<br />

between a colouring book and this place is<br />

we have expression. And we encourage expression.<br />

MMM: On your website, CWS produced a<br />

film (What’s Art Got to Do With It?) capturing<br />

an insider’s view of CWS artists in the making<br />

of an annual art show, learning about the<br />

artistic process of the artists interlaced with<br />

their narratives on mental health challenges<br />

and addictions. What inspired the creation of<br />

your film?<br />

IF: A number of things. As an arts-based occupational<br />

therapy program, one of the U of T<br />

occupational therapy students interviewed us<br />

to understand the impact of the studio. After<br />

interviewing our members, she discovered<br />

through these oral stories that consistent<br />

themes came up in terms of their transformation,<br />

in terms of how the environment<br />

affected them, in terms of how they came to<br />

find themselves in becoming artists. She said,<br />

‘This would be a great video.’<br />

I have a background in film, but I didn’t<br />

want to impose it in the studio. So when<br />

people were feeling the trust and safety, I<br />

partnered with a social scientist at St. Mike’s,<br />

Janet Parsons, and we collaborated with our<br />

members. We used a participatory community<br />

research approach and research design,<br />

and got them involved in designing the questions,<br />

and then we also used an arts-based<br />

research approach using film. And because of<br />

my background as a documentary filmmaker,<br />

I really wanted it to be not just a knowledge<br />

translation tool, but a real documentary,<br />

so that it could be accessible to the public<br />

shown at a festival or sold to a broadcaster.<br />

At the end, it was shown at the Toronto Female<br />

Eye Festival, a women’s film festival, and<br />

eventually acquired by the CBC.<br />

MMM: How do patients come to CWS and<br />

transform into artists?<br />

IF: A lot of people come to the program,<br />

many who have never worked in clay or painting<br />

before, and then they discovered that<br />

they can create, that they are an artist, and<br />

that they can move from being a patient to an<br />

artist. People are given a new identity. They<br />

take on the role and culture of being an artist.<br />

It is not art therapy, although it is therapeutic.<br />

My background is as an occupational therapist<br />

as well as an artist, so they are given a<br />

new form of occupation.<br />

MMM: In this media article, they quoted you:<br />

‘Art isn’t a luxury, it’s something that we<br />

need,’ said Fryszberg. “It’s important to have<br />

a space that is creative because together it<br />

creates a place of health.’ [1]<br />

Why is art something that we fundamentally<br />

need?<br />

IF: It gives you permission to express, take<br />

risks, to have a reflection of beauty, to have<br />

a reflection of truth. It is your culture, art<br />

creates culture. And I feel that science, true<br />

science, true math as an art. If you lose your<br />

arts, you lose your humanity. You lose a lot.<br />

You also lose your innovations. And you become<br />

robotic, mechanized and that’s dangerous.<br />

CWS has important goals for the future.<br />

The program plans to develop a toolkit<br />

to replicate their model after receiving numerous<br />

requests from organizations and curious<br />

students. Some could potentially focus on<br />

the needs of specific demographics, such as<br />

postsecondary students.<br />

Fryszberg encourages any student to<br />

volunteer and help with the program. Also,<br />

Social Mystics can be booked for playing by<br />

contacting her at www.creativeworks-studio.<br />

ca. They have their album available for sale,<br />

along with paintings, sculptures, photography,<br />

and more created by the CWS artists<br />

themselves, available through the studio.<br />

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.<br />

Isabel Fryszberg OT Reg.(Ont.)<br />

Creative Lead of Creative Works Studio<br />

St. Michael’s Inner City Health Program<br />

793 Gerrard Ave<br />

416-465-5711<br />

www.creativeworks-studio.ca<br />

Isabel Frysberg is a graduate of the Occupational<br />

Science and Occupational Therapy<br />

Program at the University of Toronto.<br />

Reference:<br />

[1] HealthCanal. 28/09/2013 02:27:00. Toronto mental<br />

health documentary What’s Art Got to Do With<br />

It? Set to screen at TIFF. Mental Health and Behavior.<br />

http://www.healthcanal.com/mental-health-behavior/43398-toronto-mental-health-documentarywhat’s-art-got-to-do-with-it-set-to-screen-at-tiff.html<br />

32 33

NON-FICTION<br />

1st Place - National<br />

“Becoming Silver Girl”<br />

by Larissa Fleurette (University of British Columbia)<br />

2nd Place - National<br />

“A View From the Inside”<br />

by Kelly Aiello (University of Toronto, St.George)<br />

Honourary Mention<br />

Becoming Silver Girl<br />

By Larissa Fleurette<br />

Graphic by Phoebe Maharaj<br />

I wrote this submission, Becoming Silver Girl, about my time in the hospital when I was a<br />

16-year-old who had just been diagnosed with a mental illness. I think it captures a glimpse of<br />

what it’s like to be 16 and in the hospital, feeling out of place and vulnerable, and how the stigma<br />

surrounding mental illness is still very much alive in the world. This story speaks about the<br />

despair and depression that comes with an illness, but eludes to also feeling inklings of hopefulness.<br />

“An Open Letter to the Guy Who Gave<br />

Me Courage”<br />

by Kelly Aiello (University of Toronto, St.George)<br />

We trick-or-treat dressed in our normal<br />

clothes: jeans, t-shirts and hoodies. I feel<br />

queasy as we walk from house to house. I<br />

remember my face in the mirror back in the<br />

mental health unit at the hospital and how<br />

awful it looked. I feel torn between wanting<br />

to go back and hide, and wanting never to go<br />

back there ever again, not back to where it’s<br />

confirmed that I am, in fact, crazy. Being in<br />

there only makes me crazier, anyway.<br />

I grasp at things to make myself feel<br />

better: the smell of the grass? The feel of the<br />

wind against my face? The memory of<br />

trick-or-treating as a child with my parents<br />

and with my siblings, dressed up in the<br />

costumes Mama created with her sewing<br />

machine?<br />

After half an hour, I’ve collected a fair<br />

amount of chocolates and candies and a<br />

random can of Coke. The other patients and I<br />

approach a lit home with a scarecrow hanging<br />

by the mailbox. About seven<br />

twenty-somethings stand in a circle next to<br />

the car parked in the driveway, drinking from<br />

beer bottles. They turn and watch us approach.<br />

“Aren’t you a little too old to be<br />

trick-or-treating?” calls one of the men.<br />

“Trying to take the candies we’ve got<br />

specially for the little ones, eh?”<br />

I’m afraid that someone will answer<br />

him. No one does. We walk past them to the<br />

porch and to the front door.<br />

34 35

Silver Girl<br />

Larissa Fleurette<br />

Minds Matter Magazine Volume II Issue I Arts & Media<br />

The twelve-year- old patient, Jason, rings a<br />

few times. When no one answers after the<br />

third ring, we turn to leave, but the man who<br />

spoke earlier puts down his beer bottle.<br />

“Is no one coming?”<br />

“No,” answers Jason. The man comes<br />

up to the front door, opens it, and suddenly,<br />

the smell of fresh flowers comes wafting<br />

through that front door.<br />

I think of my mother and her flowers,<br />

the flowers she slaves away arranging<br />

through the night in order to make it in time<br />

for the couple who have ordered them for<br />

their wedding the next day. Even more<br />

unexpected is the sound of a piano flowing<br />

from somewhere inside the house. It gives my<br />

heart a twist, unfurls it and leaves it feeling<br />

wrung out and tired of fighting.<br />

The man reappears with a basket of<br />

candy and starts to hand out chocolate bars<br />

as the piano starts to play one of my favourite<br />

songs.<br />

you have better things to do than take c<br />

hocolate and candy meant for little ones?<br />

You’re not even dressed up! If you’re going to<br />

go trick-or-treating at your age, you might as<br />

well make an effort to dress up.”<br />

I feel myself crack a little inside. It’s the<br />

exact same thing I think of when I see<br />

teenagers without costumes at my own door.<br />

Everyone accepts his chocolate bars<br />

and leaves until finally I’m the only one on<br />

the porch. I stand in front of the man, holding<br />

out my limp, half-empty Longo’s plastic bag,<br />

feeling small, pathetic and stupid. I stare at<br />

this stranger before me, at his ruffled hair and<br />

bloodshot eyes, feeling more connected to<br />

him in this moment than I have to the other<br />

patients in the past two weeks, because he<br />

knows what it’s like to feel robbed by<br />

teenagers on Halloween night, and he’s doing<br />

what I’d be doing if I were home right now.<br />

He tosses the candy from where he<br />

stands at the door, but it misses my plastic<br />

bag.<br />

Before I can do anything, he bends<br />

down and picks up the plastic hospital<br />

wristband that the nurses put on me when I<br />

was admitted. It says my name, the hospital’s<br />

name, the unit where I’m staying, and that<br />

I’m allergic to penicillin.<br />

I see his face change.<br />

“Here you go!” he says in a happy<br />

voice. I hold out my palm but he slips the<br />

wristband on. “There! Here—here’s more just<br />

for you!”<br />

He grabs a handful of candy out of his<br />

basket and drops it into my bag.<br />

“Have a nice night, sweetheart!”<br />

His bloodshot eyes stare at me, round<br />

and bulging.<br />

“Thanks. You, too.”<br />

I’m surprised at how normal my voice<br />

sounds.<br />

“I feel the same way. I wish I was Silver Girl,<br />

sailing on by, with a friend right behind me,<br />

waiting to lay his or her life down for me.”<br />

He looks down at me without moving<br />

his head.<br />

“You’re weird,” he says.<br />

“I know.”<br />

I can tell from the look on his face that<br />

he’s confused about what I said about being<br />

Silver Girl, but all the same, I feel like I’ve<br />

made a friend.<br />

Janice waves furiously from down the<br />

block. We jog towards her, swinging our plastic<br />

Longo’s bags in our hands, and when we<br />

catch up, we open the Coke cans that we got<br />

from an old lady a few houses back and drink<br />

to getting out of the hospital.<br />

“Yo, what did that guy say to you?”<br />

Jake asks me.<br />

“Sail on, Silver Girl, sail on by....” He<br />

sings under his breath in time with the piano.<br />

“Your time has come to shine, all your dreams<br />

are on their way… You’re doing great, Dora!”<br />

he shouts.<br />

The piano stops.<br />

“Thanks, Tony,” says a little girl’s voice.<br />

Then the piano starts up once more.<br />

He glances around at us in disapproval.<br />

“Why do you guys go trick-or-treating? Don’t<br />