Embroidery Basics Articles

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

TECHNICAL BULLETIN<br />

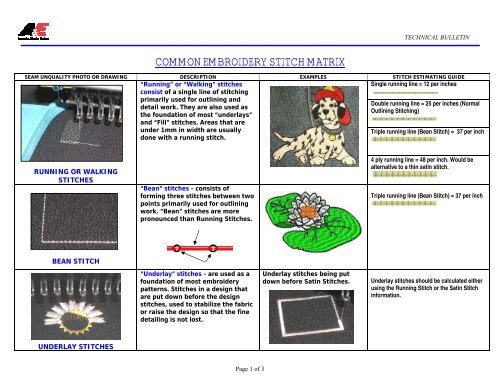

COMMON EMBROIDERY STITCH MATRIX<br />

SEAM UNQUALITY PHOTO OR DRAWING DESCRIPTION EXAMPLES STITCH ESTIMATING GUIDE<br />

“Running” or “Walking” stitches<br />

consist of a single line of stitching<br />

primarily used for outlining and<br />

detail work. They are also used as<br />

the foundation of most “underlays”<br />

and “Fill” stitches. Areas that are<br />

under 1mm in width are usually<br />

done with a running stitch.<br />

Single running line = 12 per inches<br />

Double running line = 25 per inches (Normal<br />

Outlining Stitching)<br />

Triple running line (Bean Stitch) = 37 per inch<br />

RUNNING OR WALKING<br />

STITCHES<br />

“Bean” stitches - consists of<br />

forming three stitches between two<br />

points primarily used for outlining<br />

work. “Bean” stitches are more<br />

pronounced than Running Stitches.<br />

4 ply running line = 48 per inch. Would be<br />

alternative to a thin satin stitch.<br />

Triple running line (Bean Stitch) = 37 per inch<br />

BEAN STITCH<br />

“Underlay” stitches - are used as a<br />

foundation of most embroidery<br />

patterns. Stitches in a design that<br />

are put down before the design<br />

stitches, used to stabilize the fabric<br />

or raise the design so that the fine<br />

detailing is not lost.<br />

Underlay stitches being put<br />

down before Satin Stitches.<br />

Underlay stitches should be calculated either<br />

using the Running Stitch or the Satin Stitch<br />

information.<br />

UNDERLAY STITCHES<br />

Page 1 of 3

TECHNICAL BULLETIN<br />

COMMON EMBROIDERY STITCH MATRIX<br />

“Fill” or “Tatami” stitches - are used<br />

to cover large areas. There are<br />

many different “Fill” stitch patterns<br />

and they can differ in direction,<br />

angle, and pattern. “Fill” stitches<br />

are used to cover large areas.<br />

1 square inch of “Fill” stitches at a<br />

normal density with a stitch of<br />

6mm = 1000 stitches.<br />

This would be a basic “Fill” to cover an area<br />

with no stitching on top.<br />

FILL STITCHES<br />

“Fill” or “Tatami” stitches – With<br />

today’s modern digitizing programs,<br />

there are many “Fill” stitch patterns<br />

that can be selected to give varying<br />

design appearance.<br />

Some “Fill” patterns are very<br />

complex, while other patterns are<br />

relatively simple. On certain<br />

fabrics, it is sometimes desirable<br />

to run the “Fill” on an angle so<br />

that the thread does not lay down<br />

in the weave of the fabric.<br />

1 square inch of “Fill” stitches at a<br />

normal density with a stitch of<br />

4 mm = 1500 stitches.<br />

This is normally used as a basic “Fill” to cover<br />

an area that would then have lettering or other<br />

stitching on top. The stitch length is<br />

shortened to prevent the stitches from pulling<br />

apart when the additional stitching is put on<br />

top.<br />

FILL STITCHES<br />

“Fill” or “Tatami” stitches -<br />

Curved “Fills” are also becoming<br />

more popular in the industry.<br />

Using a “Fill” stitch in a curve<br />

can add more dimension to a<br />

design. This type of stitch is very<br />

useful for hair and water.<br />

FILL STITCHES - CURVED FILL<br />

Page 2 of 3

TECHNICAL BULLETIN<br />

COMMON EMBROIDERY STITCH MATRIX<br />

SATIN STITCHES<br />

“Satin” stitches or “Column”<br />

stitches - consists of zigzag stitches<br />

laid down very close together at any<br />

angle and with varying stitch<br />

lengths. Common-ly used for<br />

lettering and outlining. Satin<br />

stitches can range in width from 1.5<br />

mm to 8 mm, however, the wider<br />

the satin stitch, the more susceptible<br />

they are to snagging and<br />

abrasion.<br />

Wider “Satin” stitches are more<br />

susceptible to snagging and<br />

abrasion and are not generally<br />

recommended for<br />

childrenswear.<br />

6 – 8 mm in width = 175 stitches<br />

per running inch. 200 stitches with<br />

underlay.<br />

4 – 6 mm in width = 150 stitches<br />

per running inch. 180 stitches with<br />

underlay.<br />

3 – 4 mm in width = 138 stitches<br />

per running inch. 165 stitches with<br />

underlay.<br />

2 – 3 mm in width = 125 stitches<br />

per running inch. 150 stitches with<br />

underlay<br />

1 mm satins = 100 stitches per<br />

running inch. 115 with underlay.<br />

“Satin” stitch lettering- stitch width<br />

and stitch density are very<br />

important in giving quality<br />

lettering. Corners should be sharp<br />

and crisp and not bulging. “Short”<br />

stitches can be digitized to<br />

minimize bulging corners.<br />

5 mm letter in Height = 100<br />

stitches.<br />

SATIN STITCHES<br />

CONVERSION INFO.<br />

3.2 mm = 1/8”<br />

6.4 mm = 1/4"<br />

9.5 mm = 3/8<br />

12.7 mm = 1/2"<br />

19.1 mm = 3/4"<br />

25.4 mm = 1”<br />

Page 3 of 3

<strong>Embroidery</strong> / Digitizing Glossary - 123Digitizing<br />

about:reader?url=http://www.123digitizing.com/embroidery-digitizing-gl...<br />

1 of 8 10/28/2016 12:11 AM<br />

123digitizing.com<br />

3D <strong>Embroidery</strong> Also known as Puff <strong>Embroidery</strong>, is a special technique to give three dimensional<br />

appearance to embroidery. A layer of foam is placed under the area where the design will be embroidered. A<br />

high stitch density is used to cut the foam for easy removal, and the foam beneath the design will not show<br />

through.<br />

Appliqué French term meaning applying. Decoration or trimming cut from one piece of fabric and stitched<br />

to another to add dimension and texture and reduce stitch count.<br />

Backing Woven or non-woven material used underneath the item or fabric being embroidered to provide<br />

support and stability for the needle penetration. Best used when hooped with the garment, but can also be<br />

placed between the item to be embroidered and the needle plate on flat bed machines. Available in many styles<br />

and weights with two basic types - Cutaway and Tearaway.<br />

Bean Stitch Three stitches placed back and forth between two points. Often used for outlining because it<br />

eliminates the need for repeatedly digitizing a single-ply running stitch outline.<br />

Birdnesting (Birdnest, Birds Nest) Accumulation of thread caught between the embroidered item and<br />

the needle plate, often caught in the needle plate hole and hook assembly. Formation of a birdnest prevents free<br />

movement of goods and may be caused by inadequate tensioning of the top thread, top thread not through<br />

take-up lever, top thread not following thread path correctly or flagging goods.<br />

Bobbin Spool or reel that holds the thread used to form the underside stitching. Bobbin thread works with<br />

upper thread to create stitches.<br />

Bobbin Case Small, round metal device for holding the bobbin. Used to tension the bobbin thread, it is<br />

inserted in the hook for sewing.<br />

Boring Embroidered goods that have been punctured with a sharp pointed tool known as a bore, the edges of<br />

the hole produced by the bore are embroidered, the hole is enlarged by the embroidery.<br />

Buckram or Buckram Lining Coarse, woven fabric, stiffened with glue, and used to stabilize fabric for<br />

stitching. Commonly used in caps to hold the front panel erect.<br />

Chain Stitch Stitch that resembles a chain link, formed with one thread fed from the bottom side of the

<strong>Embroidery</strong> / Digitizing Glossary - 123Digitizing<br />

about:reader?url=http://www.123digitizing.com/embroidery-digitizing-gl...<br />

2 of 8 10/28/2016 12:11 AM<br />

fabric. Done on a manual or computerized machine with a hook that functions like a needle.<br />

Chenille Type of embroidery. Commonly found in appliqué and athletic applications characterized by a<br />

design surface comprised of heavy loops of thread; sewn with heavy threads or yarns, chenille is created on<br />

specialized embroidery equipment.<br />

Column Stitch Typically used to form borders around fill areas and for rendering text, the column stitch<br />

consists of closely spaced satin stitches.<br />

Compensation <strong>Embroidery</strong> digitizing technique used to counteract/compensate the distortion (pull or<br />

push) caused by the interaction of the needle, thread, backing and machine tensions. Also a programmable<br />

feature in some software packages.<br />

Complex Fill Similar to standard fill. Refers to an embroidery digitizing technique that allows digitizer to<br />

'knock out' area(s) within fill, creating openings or negative space (visualize Swiss cheese). The design can thus<br />

be digitized as one fill area, instead of being broken down into multiple sections.<br />

Condensed Format Method of embroidery digitizing where a design is saved in a skeletal form, so a<br />

proportionate number of stitches may later be placed between defined points after a scale has been designated.<br />

If a machine can read condensed format, the scale, density and stitch lengths in a design may be changed. See<br />

"expanded format".<br />

Cutaway One of two basic types of backing materials. Another type is Tearaway.<br />

Density Number of stitches in a specific area. Determines the total thread coverage in a design.<br />

Digitizing or <strong>Embroidery</strong> Digitizing Modern term for punching. <strong>Embroidery</strong> Digitizing is the process of<br />

taking any form of artwork and transforming it into a language that the commercial embroidery machine or<br />

home sewing machine can understand and stitch it out. <strong>Embroidery</strong> Digitizing is a complex process which uses<br />

stitch types including running stitch, satin stitch and fill stitch to create an embroidery design. It requires many<br />

steps from starting with a simple clip art to a stitched out design. <strong>Embroidery</strong> Digitizing Software is needed for<br />

this process. Software vendors often advertise auto-digitizing capabilities. However, if high quality embroidery<br />

is essential, then industry experts highly recommend either purchasing solid designs from reputable digitizers<br />

or obtaining training on solid digitization techniques.<br />

Digitizer or <strong>Embroidery</strong> Digitizer A person who creates embroidery designs is known as an embroidery<br />

digitizer or puncher. A digitizer uses digitizing software to create an object-based embroidery design, which can<br />

be easily reshaped and edited. These files retain important information such as object outlines, thread colors,<br />

and original artwork used to punch the designs. When the file is converted to a stitch file, it loses much of this

<strong>Embroidery</strong> / Digitizing Glossary - 123Digitizing<br />

about:reader?url=http://www.123digitizing.com/embroidery-digitizing-gl...<br />

3 of 8 10/28/2016 12:11 AM<br />

information, rendering editing difficult or impossible.<br />

Digitizing Tablet The platen or surface on which original art to be digitized is placed; holds the artwork flat,<br />

allowing digitizer to specify various design characteristics by 'tracing' and otherwise designating them with a<br />

digitizing 'puck' (input device similar to a computer mouse).<br />

Editing Changing aspects of a design via a computerized editing program. Most programs allow the user to<br />

scale designs up or down, edit stitch by stitch or block by block, merge lettering with the design, move aspects of<br />

the design around, combine designs and insert or edit machine commands.<br />

Emblem Also known as Crest or Patch. Embroidered design with a finished edge, commonly an insignia of<br />

identification, usually worn on outer clothing. Historically, an emblem carried a motto, verse or suggested a<br />

moral lesson.<br />

<strong>Embroidery</strong> Refers to Machine <strong>Embroidery</strong> here, or more precisely, Computerized Machine <strong>Embroidery</strong>. A<br />

process whereby a computer-controlled embroidery machine is used to create patterns on textiles. It is used<br />

commercially in product branding, corporate advertising, and uniform adornment. Hobbyists also machine<br />

embroider for personal sewing and craft projects. Most modern embroidery machines are equipped with<br />

computers specifically engineered for embroidery. Depending on their capabilities and usages, these machines<br />

range from signle-needle, single-head sewing machines for home use and hobbyists, to industrial and<br />

commercial embroidery machines that are multi-headed (6 to 20 heads are common), with multi-needles (9 to<br />

15 are common) under each head. They all have a hooping or framing system that holds the framed area of<br />

fabric taut under the sewing needle(s) and moves it automatically to create a design from a pre-programmed<br />

digitizing file prepared by an embroidery digitizer.<br />

Expanded Format A design program where individual stitches in a design have been specifically digitized<br />

for a certain size. Designs digitized in this format cannot generally be enlarged or reduced more than 10 to 20<br />

percent without distortion because stitch count remains constant. See "condensed format".<br />

File Format <strong>Embroidery</strong> file formats broadly fall into two categories. The first, source formats, are specific<br />

to the software used to create the design. For these formats, the digitizer keeps the original file for the purposes<br />

of editing. The second, machine formats, are specific to a particular brand of embroidery machine. Machine<br />

formats generally contain primarily stitch data (offsets) and machine functions (trims, jumps, etc.) and are<br />

thus not easily scaled or edited without extensive manual work.<br />

Fill or Fill Stitch Also known as Tatami stitch. Relatively large design area covered by series of running<br />

stitches, the pattern of which may be varied in terms of stitch length, angle and density.<br />

Finishing Processes performed after embroidery is complete. Includes trimming loose threads, cutting or

<strong>Embroidery</strong> / Digitizing Glossary - 123Digitizing<br />

about:reader?url=http://www.123digitizing.com/embroidery-digitizing-gl...<br />

4 of 8 10/28/2016 12:11 AM<br />

tearing away excess backing, removing topping, cleaning any stains, pressing or steaming to remove wrinkles or<br />

hoop marks and packaging for sale or shipment.<br />

Flagging Up and down motion of goods under action of the needle, so named because of its resemblance to a<br />

waving flag. It is often caused by improper framing (hooping) of goods. Flagging may result in poor<br />

registration, unsatisfactory stitch formation and birdnesting.<br />

Frame Holding device for insertion of goods under an embroidery head for the application of embroidery.<br />

May employ a number of means for maintaining stability during the embroidery process, including clamps,<br />

vacuum devices, magnets or springs. See "hoop" for more information.<br />

Guide Stitch Running stitches used to assist in placement of an applique or in the placement of a die for<br />

cutting of emblems, also called a cut line.<br />

Hook Holds the bobbin case in the machine and plays a vital role in stitch formation. Making two complete<br />

rotations for each stitch, its point meets a loop of top thread at a precisely-timed moment and distance (gap) to<br />

form a stitch.<br />

Hook Timing Proper synchronization of hook's rotary and needle's up/down movement; necessary to form<br />

stitches.<br />

Hoop Device made from wood, plastic or steel with which fabric is gripped tightly between an inner ring and<br />

an outer ring and attached to the machine's pantograph. Machine hoops are designed to push the fabric to the<br />

bottom of the inner ring and hold it against the machine bed for embroidering.<br />

Hooping Aid or Hooping Device Device that aids in hooping garments or items for embroidery, in order<br />

to enhance hooping efficiency and consistency. Especially helpful for hooping multi-layered items and for<br />

uniformly hooping multiple items.<br />

Jump Stitch Movement of the frame without stitching but with take up lever and hook movement.<br />

Lettering <strong>Embroidery</strong> using letters or words. Lettering, commonly called “keyboard lettering,” may be<br />

created using an embroidery lettering program on a PC or from circuit boards that allow variance of letter style,<br />

size, height, density and other characteristics.<br />

Lock Stitch Also known as lock-down or tack-down stitch, a lock stitch is formed by three or four consecutive<br />

stitches of at least a 10-point movement. It should be used at the end of all columns, fills and at the end of any<br />

element in your design where jump stitches will follow, such as color changes or the end of a design. Lock<br />

stitches may be sewn in a triangle, star or in a straight line. Lock stitch is also the name of the type of stitch

<strong>Embroidery</strong> / Digitizing Glossary - 123Digitizing<br />

about:reader?url=http://www.123digitizing.com/embroidery-digitizing-gl...<br />

5 of 8 10/28/2016 12:11 AM<br />

formed by the hook and needle of home sewing machines, as well as computerized embroidery machines.<br />

Logo Graphic mark or symbol commonly used by companies, organizations and even individuals to aid and<br />

promote instant public recognition. Logos can be purely graphic symbols/icons (logomark - e.g. Apple) or just<br />

the name of the organization (logotype or wordmark - e.g. Google) or the combination of the two (lockup - e.g.<br />

McDonald's Golden Arches with their name underneath or across).<br />

Looping Loops on the surface of embroidery generally caused by poor top tension or tension problems.<br />

Typically occurs when polyester top thread has been improperly tensioned.<br />

Machine Language or Machine Format The embroidery digitizing codes and formats used by different<br />

machine manufacturers within the embroidery industry. Common formats include Barudan, Brother, Fortran,<br />

Happy, Marco, Meistergram, Melco, Pfaff, Stellar, Tajima, Toyota, Ultramatic and ZSK. Most embroidery<br />

digitizing systems can save designs in these languages so the computer disk can be read by the embroidery<br />

machine. Also see "file format"<br />

Merrowed Edge A merrowed edge is a 3/16" overlocked sewn edge done to secure the cut fabric from<br />

unravelling. Usually used for the bottom edge of emblems, pant cuffs or garment interior cut edges.<br />

Monogram Embroidered design composed of one or more stylized letters, usually the initials in a name.<br />

Needle Small, slender piece of steel with a hole for thread and a point for stitching fabric. A machine needle<br />

differs from a handwork needle; the machine needle's eye is found at its pointed end. Machine embroidery<br />

needles come with sharp points for piercing heavy, tightly woven fabrics; ball points, which glide between the<br />

fibers of knits; and a variety of specialty points, such as wedge points, which are used for leather. See<br />

"<strong>Embroidery</strong> Tips and Techniques" page for more information.<br />

Nippers Small, scissors-like cutting tool specifically designed for thread trimming, during finishing of<br />

embroidery.<br />

Puckering Result of the fabric being gathered into small folds or wrinkles by the stitches, caused by incorrect<br />

density, loose hooping, having no backing, incorrect tension or a dull needle.<br />

Push Compensation and Pull Compensation Deliberate counteraction digitized into a design to<br />

compensate for thread push and/or pull effect that would otherwise cause a 10mm wide stitch (for example) to<br />

shrink to a 9mm stitch. Also see Compensation and Push and Pull below.<br />

Push and Pull The distortion of design elements caused by the interaction of the needle, thread, backing and<br />

machine tensions. In most cases the element and/or the fabric are causing either push or pull, but not both. The

<strong>Embroidery</strong> / Digitizing Glossary - 123Digitizing<br />

about:reader?url=http://www.123digitizing.com/embroidery-digitizing-gl...<br />

6 of 8 10/28/2016 12:11 AM<br />

exception to this rule tends to be in satin stitch columns, whether in a letter, outline or otherwise. Satin columns<br />

can pull in on the ends (thus reducing column width) and push out on the sides (thus increasing column length).<br />

To counteract these distortions, digitizers use a technique call Compensation.<br />

Registration Correct registration is achieved when all stitches and design elements line up correctly.<br />

Running Stitch Sometimes called 'walking' stitch, used for fine detail, outlining, and quickly covering space<br />

between separate design elements; used primarily for underlay.<br />

Satin Stitch Closely spaced stitches, similar to zigzag, except that they alternate between straight stitches<br />

and angled stitches (rather than all angled) of varying length, angle and density. A satin stitch is normally<br />

anywhere from 2mm to 10mm<br />

SPI Stitches per inch; system for measuring density or the amount of satin stitches in an inch of embroidery.<br />

SPM Stitches per minute; system for measuring the running speed of an embroidery machine. Ranging from<br />

as slow as 60 SPM to as high as 1500 SPM.<br />

Scaling Ability within one design program to enlarge or reduce a design. In expanded format, most scaling is<br />

limited 10 to 20 percent because the stitch count remains constant despite final design size. Condensed or<br />

outline formats, on the other hand, scale changes may be more dramatic because stitch count and density may<br />

be varied.<br />

Scanning Scanners convert designs into a computer format, allowing the digitizer to use even the most<br />

primitive of artwork without recreating the design. Many embroidery digitizing systems allow the digitizer to<br />

transfer the design directly into the embroidery digitizing program without using intermediary software.<br />

Short Stitching An embroidery digitizing technique that places shorter stitches in curves and corners to<br />

avoid an unnecessary bulky build-up of stitches.<br />

Special Fill A function available in some embroidery digitizing software that automatically incorporates<br />

special patterns, motifs or textures into fill areas.<br />

Stability The property of a bonded fabric that prevents sagging, slipping or stretching. This is conducive to<br />

ease of handling in manufacturing, and helps the fabric to keep its shape in wear, dry cleaning and washing.<br />

Stitch Count The total number of stitches in a particular design.<br />

Stitch Editing <strong>Embroidery</strong> digitizing feature that allows one or more stitches in a pattern to be deleted or

<strong>Embroidery</strong> / Digitizing Glossary - 123Digitizing<br />

about:reader?url=http://www.123digitizing.com/embroidery-digitizing-gl...<br />

7 of 8 10/28/2016 12:11 AM<br />

altered.<br />

Stitch Processing The calculation of stitch information by means of specialized software, allowing scaling of<br />

expanded format designs with density compensation. A trademarked software feature developed by Wilcom<br />

Pty. of Australia.<br />

Stock Designs Digitized generic embroidery designs that are readily available at a cost below that of<br />

custom-digitized designs.<br />

Swatch A stitched out sample of an embroidery design used for inspection, comparison, construction, color,<br />

finish and sales purposes.<br />

Tackle Twill Letters or numbers cut from polyester or rayon twill fabric that are commonly used for athletic<br />

teams and organizations. Tackle twill appliqués attached to a garment have an adhesive backing that tacks<br />

them in place; the edges of the appliqués are then zigzag stitched.<br />

Tearaway One of two basic types of backing materials. Another type is Cutaway.<br />

Tension Tautness of thread when forming stitches. Top thread tension, as well as bobbin thread tension,<br />

needs to be set and balanced. Proper thread tension is achieved when about one-third of the thread showing on<br />

the underside of the fabric on a column stitch is bobbin thread.<br />

Thread Fine cord of natural or synthetic material made from two or more filaments twisted together and<br />

used for stitching. Machine embroidery threads come in rayon, which has a high sheen; cotton, which has a<br />

duller finish than rayon but is available in very fine deniers; polyester, which is strong and colorfast; metallic<br />

thread, which have a high luster and are composed of a synthetic core wrapped in metal foil; and acrylic, which<br />

is purported to have rayon's sheen.<br />

Thread Clippers Small cutting utensil with a spring action that is operated by the thumb in a hole on the top<br />

blade and the fingers cupped around the bottom blade. Useful for quick thread cutting, but unsuitable for<br />

detailed trimming or removal of backing.<br />

Topping Also known as facing. Material hooped or placed on top of fabrics that have definable nap or surface<br />

texture, such as corduroy and terry cloth, prior to embroidery. The topping compacts the wale or nap and holds<br />

the stitches above it. Includes a variety of substances, such as plastic wrap, water-soluble plastic “foil” and<br />

open-weave fabric that has been chemically treated to disintegrate with the application of heat.<br />

Trimming Operation in the finishing process that involves trimming the reverse and top sides of the<br />

embroidery, including jump stitches and backing.

<strong>Embroidery</strong> / Digitizing Glossary - 123Digitizing<br />

about:reader?url=http://www.123digitizing.com/embroidery-digitizing-gl...<br />

8 of 8 10/28/2016 12:11 AM<br />

Underlay Stitches applied prior to other design elements to either A) neutralize fabric-surface<br />

characteristics (see also topping); or B) to create special design effects such as depth and dimensionality.<br />

Variable Sizing Ability to scale a design to different sizes.<br />

Zigzag Stitches that progress in an alternating-angle (zigzag) fashion; typically used for final stitching on<br />

appliqué and tackle twill.

10/28/2016 Digitizing Glossary Eagle Digitizing<br />

Email Address •••• Login<br />

My<br />

status Live Chat Forgot Your Password Create Account<br />

Home Order Online Digitizing Vector ART Payment Information Samples Testimonials Send to a Friend<br />

ABOUT US<br />

Eagle Digitizing has been in the<br />

embroidery industry since the early<br />

1990s.Our collective working ...<br />

HELP CENTER<br />

Find answers to Frequently Asked<br />

Questions.<br />

SUPPORT<br />

Formats Available | Digitizing Fonts<br />

| Color Chart | Digitizing Glossary |<br />

Size Conversion | Vector service<br />

CONTACT US<br />

Email: sales@eagledigitizing.com<br />

Phone: 18662424888<br />

Home >> Support >> Glossary<br />

Jump Stitch: Movement of the frame without stitching but with take up lever and<br />

hook movement.<br />

................................................................................................................................<br />

Lettering: <strong>Embroidery</strong> using letters or words, either made completely with stitches,<br />

or a combination of cutout applique pieces and stitching.<br />

................................................................................................................................<br />

Lock stitch: Commonly referred to as a lockdown or tackdown stitch, a lock stitch<br />

is formed by three or four consecutive stitches of at least a 10point movement. It<br />

should be used at the end of all columns, fills and at the end of any element in your<br />

embroidery design where jump stitches will follow, such as color changes or the<br />

end of a design. Lock stitches may be stitched in a triangle, star or in a straight line.<br />

Lock stitch is also the name of the type of stitch formed by the hook and needle of<br />

home sewing machines, as well as computerized embroidery machines.<br />

................................................................................................................................<br />

Machine Language: The codes and formats used by different machine<br />

manufacturers within the embroidery industry.<br />

https://www.eagledigitizing.com/en/glossary.asp?page=3 1/3

10/28/2016 Digitizing Glossary Eagle Digitizing<br />

................................................................................................................................<br />

Monogram: Embroidered digitizing design composed of one or more letters, usually<br />

the initials in a name.<br />

................................................................................................................................<br />

Needle: Small slender sewing instrument with an eye at one end to pass the thread<br />

through.<br />

................................................................................................................................<br />

Outline: 1.Running, double or bean stitch used to define embroidery details in<br />

embroidery designs. 2. <strong>Embroidery</strong> digitizingcapability to input points to define<br />

the perimeter of the embroidered area.<br />

................................................................................................................................<br />

Push and pull: The terms push and pull are used together so often, it seems at<br />

times people believe they happen together. They do sometimes, but in most cases<br />

the element and/or the fabric are causing either push or pull, but not both. The<br />

exception to this rule tends to be in satin stitch columns, whether in a letter or<br />

otherwise. Satin columns can pull in on the ends and out on the sides.<br />

................................................................................................................................<br />

Running Stitch: Running stitches or walk stitches are single line stitches which run<br />

one stitch between two needle penetration point. A running stitch goes from point A<br />

to point B. They are used for very fine detail and also for underlay.<br />

................................................................................................................................<br />

Satin Stitch: Satin stitches are nothing more than zigzag stitches. A satin stitch can<br />

range in thickness from just over 1mm to usually a maximum of 12mm. A satin stitch<br />

is normally used for nice detail and for most normal size lettering.<br />

https://www.eagledigitizing.com/en/glossary.asp?page=3 2/3

10/28/2016 Digitizing Glossary Eagle Digitizing<br />

................................................................................................................................<br />

1 2 3 4 Pre Next<br />

Home | Digitizing Samples | Pricing | Payment Information | About Us | Contact Us | Testimonials | Help Center | Formats | Digitizing Glossary<br />

Digitizing Fonts | Color Chart | Size Conversion | Blog | Order Online | Free Monthly Download | Login | Site Map | Privacy & Security Policy<br />

Link: Embroidered blankets ,Wholesale blankets<br />

Copyright © 2009201 1 Eagle Digitizing. All rights reserved.<br />

Services and products: digitizing , embroidery digitizing , embroidery designs , vectorization<br />

https://www.eagledigitizing.com/en/glossary.asp?page=3 3/3

10/28/2016 Needles Getting To The Point <strong>Embroidery</strong> Article<br />

15 Reviews<br />

Needles Getting T o The Point<br />

By Bonnie Landsberger on June 12, 2014<br />

Share Your Project<br />

(Click Image to Enlarge)<br />

0 0 0<br />

Needles Getting To The Point<br />

Confused about needles? Beginning the work with a new needle, and choosing the right size and type of needle for the design and<br />

fabric that you are stitching on, can make a world of dif ference in the quality of the finished embroidery . When the wrong needle is<br />

chosen for the work or the needle is in poor condition, the threads can loop, skip stitches, or break. As well the fabric might pucker<br />

around the design and stitches may distort and appear shabby . Learning a bit about needles can help you solve many problems<br />

that would otherwise be quite frustrating, as well as costly when the wrong needle causes damage to the garment. Let's take a<br />

closer look.<br />

Click on the small thumbnail images to enlarge .<br />

Parts of the Needle<br />

Shank: the top part of the needle that fits into the needle bar and its shape reveals whether the<br />

needle is for a commercial machine or a domestic machine. If the shank is completely round in<br />

circumference, it is for a commercial machine, and if it's flat on one side, it is for a domestic<br />

machine.<br />

Blade or Shaft: the part of the needle that extends from the bottom of the shank to the point.<br />

Scarf: curved indent above the eye on the back of the needle. This indent allows room for the<br />

hook that comes up and around and catches the top thread, locking it with the bobbin thread to<br />

form a stitch.<br />

Groove: straight indent on the front of the needle between the eye and the base of the shank that<br />

allows for the thread to lie close against the shaft while the needle passes through the fabric.<br />

Eye: the hole where the thread passes through.<br />

Point: the tip of the needle at the bottom below the eye that pierces the substrate, such as fabric,<br />

leather, paper, etc.<br />

Needle Points<br />

At left is a commercial Ball Point, and at right is a domestic Universal Point.<br />

Ball: the point is slightly rounded to push between the fabric fibers without cutting them,<br />

eliminating runs and tears in fabric like knits, nylon and fleece. A Light Ball Point, such as<br />

Universal, is not quite a sharp point and not quite a ball point, landing somewhere in between.<br />

Sharp: the point will cut through the fibers allowing for a more accurate penetration on the fabric<br />

without causing puckers and it's suitable for fabrics that don't usually run like denim, terrycloth,<br />

and tightly woven fabrics, as well as leather and paper . An Acute Round Point id the sharpest<br />

point needle.<br />

https://www.embroiderydesigns.com/emb_learning/article/923/needlesgettingtothepoint.aspx 1/3

10/28/2016 Needles Getting To The Point <strong>Embroidery</strong> Article<br />

Needle Sizes and Types<br />

Most needle packages list both European and American sizes. A high number indicates a thicker<br />

needle and larger eye, and a lower number indicates a thinner needle and smaller eye. On<br />

commercial machines an average size of DBxK5 75/1 1 ball point or light ball point (SES) often<br />

works best for most fabrics when stitching with 40 WT thread, whereas, a larger size would be<br />

best for the thicker 30 WT thread.<br />

Needles for domestic machines include the size number , but many that can be used for both<br />

embroidery and normal sewing are marked for the job, such as “T opstitch” or “Universal”.<br />

You will also find specialty needles, such as the W edge Point that has a Vshaped sharp point,<br />

used to cut a larger hole in leather and allow the thread to pass through without shredding. T eflon<br />

Coated needles will make stitching with metallic threads less dif ficult by reducing the friction on<br />

the thread and keep it from fraying, and they also work well for stitching coated or waterproof<br />

fabrics. Denim needles are designed for tightly woven fabrics like denim or similar , and will also<br />

stitch through multiple layers of fabric, such as for quilting. T win needles are handy for stitching a<br />

doubleline topstitch, such as for hems. Double eye needles have two eyes in one needle for<br />

stitching with two spools of thread at the same time; used for decorative stitching. Selfthreading<br />

needles have a notch in the side of the needle to slip the thread through the eye, instead of<br />

threading directly through center and are helpful to those with impaired vision.<br />

Needle Condition<br />

This damage is dif ficult to recognize, but when viewed through a magnifying glass, it's revealed<br />

this needle was bent slightly when striking a pin; as indicated when compared against the blue<br />

horizontal guideline. You should never start stitching without first examining the needle. Problems<br />

like a dull, bent or chipped point are not always obvious and can result in a poor sewout or<br />

damaged goods. A dull needle can be the cause of stitches looping on the top, flagging in the<br />

hoop (fabric bouncing up and down with the needle), as well as loose bobbin stitches and<br />

birdnesting.<br />

Birdnesting:<br />

A collection of tangled thread between fabric and needle plate that resemble the nest of a bird,<br />

usually caused by poor top tension, top thread not through takeup lever , incorrect thread path,<br />

needle not seated properly or fabric flagging. Removal consists of carefully snipping away the<br />

threads between the fabric and the needle plate; threads can be pulled away from the needle<br />

plate with a tool like a small needle nose pliers or hemostat (locking clamp), and then cut with an<br />

XActo utility knife.<br />

Schmetz Needles advises, “The operator should check the needle point regularly for damage.<br />

This can be done with the fingernail of the pointing finger or with a piece of nylon stocking. The<br />

best effect is achieved if the check is done every hour . This check is essential when you are<br />

sewing knitwear because only this measure together with a needle change policy will maintain a<br />

good quality garment.” When new needles continue to break, be sure that the needle is inserted<br />

correctly, the needle clamp screw is tightened and the needle is straight with the eye facing front<br />

to back. Any slight collision of the needle can cause it to bend, such as hitting the hoop, striking a<br />

pin or the needle plate, or even when the hoop is held a bit too high when removed, allowing the<br />

fabric or hoop to scrape the point.<br />

Needle Use Chart<br />

Canvas: 80/12 sharp<br />

Coated/waterproof: 80/12 sharp/ball point<br />

Corduroy: 75/11 sharp/ball point<br />

Cotton Sheeting: 70/10, 75/11, 80/12 sharp<br />

Denim: 75/11 sharp<br />

Dress Shirt: 70/10, 75/11, 80/12 ball point<br />

https://www.embroiderydesigns.com/emb_learning/article/923/needlesgettingtothepoint.aspx<br />

Duck Cloth: 75/11 sharp<br />

2/3

10/28/2016 Needles Getting To The Point <strong>Embroidery</strong> Article<br />

Duck Cloth: 75/11 sharp<br />

Golf Shirt: 70/10, 75/11, 80/12 ball point<br />

Knits: 75/11 ball point<br />

Lace: 75/11 sharp point<br />

Leather: 80/12, 90/14 sharp point or 75/1 1, 90/14 wedge point<br />

Lingerie & Silk: 60/8, 70/10, 75/11 sharp/ball point<br />

Lycra, Spandex: 70/10, 75/11, 80/12 ball point<br />

Nylon Wind breaker: 70/10, 75/11, 80/12 ball point<br />

Organza: 65/9 ball point<br />

Paper: 75/11 sharp point<br />

Rayon: 75/11 ball point<br />

Satin Jacket: 75/11 ball point<br />

Sweatshirt: 70/10, 75/11, 80/12 ball point<br />

Taffeta: 65/9 ball point<br />

Terry cloth towel: 75/11 sharp/ball point<br />

Water Soluble Stabilizer (for FSL): 75/11 sharp<br />

Velvet: 65/9 ball point<br />

Vinyl: 75/11 sharp point or 75/1 1 wedge point<br />

Test The Needle<br />

Always stitch the design on same or very similar fabric as the final garment, using the needle<br />

recommended for the substrate. Examine the sample and if you see any large needle<br />

penetrations, switch to a smaller needle, or if the thread is shredding or breaking, switch to a<br />

larger needle. If the fabric is puckering around the design or the stitches appear distorted, it might<br />

be caused by a ball point needle pushing at and stretching the fabric; if so, switch to a sharp<br />

point. If you are using a sharp point and see fabric fibers fraying next to the stitches, or fill stitches<br />

in the design are shredding as top elements stitch, switch to a ball point.<br />

More From This Author<br />

Dish Soap Bottle Apron By Bonnie Landsberger<br />

Computer <strong>Basics</strong> for the Machine Embroiderer Part 1 By Bonnie Landsberger<br />

Computer <strong>Basics</strong> for the Machine Embroiderer Part 2 By Bonnie Landsberger<br />

Share this project:<br />

0 0 0<br />

Meet The Author: Bonnie Landsberger<br />

Bonnie Landsberger has been a crafter and hand embroiderer since childhood and a<br />

machine embroiderer and digitizer since 1986. She was the inhouse head digitizer for a 50<br />

head embroidery shop for 1 1 years and later of fered custom digitizing services and stock<br />

design sales through her web site for Moonlight Design since 1993. She currently also holds<br />

a position as a customer service representative at <strong>Embroidery</strong>Designs.com. Bonnie has won<br />

several awards for digitizing, including a gold medal in the 2002 Digitizing Olympics and<br />

grand prize in all categories & first place for Winter Holidays category in the Stitches<br />

Magazine Great Greeting Card Contest 2003. Her embroidery and digitizing technical<br />

articles can be found in various trade magazines and she is currently a contributing writer and Editorial<br />

Advisory Board Member for Stitches Magazine. You can also find more of her articles online at<br />

<strong>Embroidery</strong>Designs.com and will continue to contribute articles to our Learning Center .<br />

https://www.embroiderydesigns.com/emb_learning/article/923/needlesgettingtothepoint.aspx 3/3

10/28/2016 Thick and Thin: So Many Fabrics...So Many ays W <strong>Embroidery</strong> Article<br />

(Click Image to<br />

Enlarge)<br />

Not Yet Rated<br />

Thick and Thin: So Many Fabrics...So<br />

Many Ways<br />

By Barbara Geer on August 01, 2008<br />

Share Your Project<br />

0 0 0<br />

So Many Fabrics...So Many Ways<br />

As embroiderers, we get customers of all kinds. W ell, at least we do in our shop. In this very small town that I live in, we don’t turn<br />

anybody away. Whether the buyer is looking for one Grandma shirt or hundreds of items, we take the order . Consequently, we need<br />

to know how to handle all dif ferent types of fabrics, or perhaps I should call them substrates, because not all embroidery is on<br />

fabric!<br />

For example, in a typical day, we may be required to embellish polo shirts, polar fleece blankets, leather jackets, denim shirts,<br />

caps, bags, sweatshirts, T s…you name it. We even embroidered a wheel cover one time! Just today we had a request to put a<br />

name on a gun case.<br />

In other words, substrates of varying weights, thicknesses and stability go under the needle all day long. Some are thick and some<br />

are thin!<br />

For the purposes of this article, let’ s assume that a restaurant owner has come in and requested twill chef ’s coats, polos for<br />

waiters and waitresses, six panel caps, tshirts and various items for the gift shop, including fleece blankets, CD cases and a sport<br />

bag, all decorated with the company logo.<br />

A number of considerations are required to achieve the best embroidery on various articles using the same logo. Let’ s take a look<br />

at digitizing for garment types, editing to make a design work, backing the embroidery and hooping techniques. Assuming that the<br />

embroidery machine is in good working order , with proper tensions set, those factors must be conquered to achieve quality<br />

embroidery.<br />

Digitizing<br />

As a digitizer, I know full well that the easiest person to blame for substandard embroidery is me. Therefore, I take my job very<br />

seriously in terms of creating a design specifically for the fabrics upon which it will be placed.<br />

In this order, we have three distinct categories of substrates. The easiest and least likely to give us problems are the solid fabrics<br />

that are in the twill chef ’s coat, the CD cases and the bags. My favorite theme here is ef ficiency. As any other good digitizer would<br />

do, I try to achieve the best results with the least amount of stitches. After all, that’ s where the money is. A minimal amount of<br />

underlay is necessary to secure the fabric to the backing. Because these fabrics are solid, stitches do not sink into them as they<br />

would to less stable substrates. I would try to use each thread color only once, walking from one color block to the next, avoiding<br />

timewasting trims whenever possible. The only time I would repeat a color would be if there were apparent layers in the design<br />

that couldn’t be achieved any other way.<br />

The second category includes the knits. The stretchy properties of polos, T shirts, sweatshirts and polar fleece make them<br />

unstable surfaces upon which to embroider . Couple that with the fact that many knit fabrics have a nap that is more dif ficult to cover<br />

when the threads sink into them, and you have what many would term a digitizing nightmare! The common misconceptions that<br />

adding more density to the design and the end result of having many more stitches can be laid to rest, though. Proper underlay is<br />

the key to great embroidery on knits. Because the stitches will certainly sink into the fabric, what we need here is a way to make<br />

them stand up above the material. A fill underlay , running the opposite direction of the stitches will prevent the sinking. In the case<br />

of polar fleece and other napped fabrics, it may even be necessary to use a secondary underlay in addition to the primary underlay ,<br />

each running at fortyfive degree angles from the stitch direction of the fill. Columns may need an edge walk underlay rather than a<br />

center walk, or maybe in addition to the center walk.<br />

Of course, all that underlay will definitely add to the stitch count in the design, but it will never add as many stitches as increasing<br />

the density of the fill. Plus, the embroiderer will avoid the unsightly buckling of the fabric that can be caused by too many stitches.<br />

https://www.embroiderydesigns.com/emb_learning/article/559/thickandthinsomanyfabricssomanyways.aspx<br />

The last category in our diverse order is the caps. Headwear is a dif ferent breed of cat when it comes to digitizing. I’ve devoted<br />

1/4

10/28/2016 Thick and Thin: So Many Fabrics...So Many ays W <strong>Embroidery</strong> Article<br />

The last category in our diverse order is the caps. Headwear is a dif ferent breed of cat when it comes to digitizing. I’ve devoted<br />

whole articles to this subject, but space does not permit that extensive a review here. Let me just say this, ef ficiency be hanged!<br />

Cap designs perform best when they are digitized from the center out and from the bottom to the top. Why? Though caps are<br />

usually constructed from stable fabrics, most are flimsy and hard to hoop. The most stable part of the cap is near the seam that<br />

secures the crown to the bill, followed by the area of the center seam. W orking up and out from those two stable portions pushes<br />

the fabric the same distance with each pass of the embroidery machine, allowing for better registration in the design.<br />

Other than the digitizing for caps, which is usually something that needs to be done separately , editing a design can usually<br />

provide the changes necessary to move from one fabric type to another . In today’s world of sophisticated digitizing and editing<br />

software, a click of the mouse is all it takes to add underlay when needed.<br />

§<br />

This design, a chef outline, has a center walk underlay , which is suf ficient in making the columns<br />

stand up from the garment in most cases. However , soft knits might need an edge walk to prevent<br />

the stitches from sinking.<br />

Zigzag is the term that seamstresses are familiar with, and is comparable to a light density<br />

column. When this underlay is combined with a center walk or edge walk on satin columns, it<br />

serves the purpose of laying down the “pile” on fabrics such as terrycloth or polar fleece. While the<br />

underlay adds stitches to the design, it saves cleanup time when the embroiderer can eliminate<br />

the use of a topping.<br />

The stitched version, or sewout, of the chef outline.<br />

A filled design generally has underlay stitches that run the opposite direction of the fill patterns.<br />

For most fabrics, this is enough underlay to serve the purposes of tacking the backing to the<br />

garment and making the fill stand up from the garment. This particular design has a satin stitch<br />

that cleans up the edges, as well.<br />

A great way to tame pile that tends to poke its way through fill patterns is to add a secondary<br />

underlay running the opposite direction of the primary underlay . When this is done, both should<br />

run at 45 degree angles to the fill. Since the design has many fill patterns, I chose to digitize a<br />

separate underlay that would encompass the entire design, duplicate that pattern and change the<br />

fill direction of the second to run the opposite direction of the first. In this case, the underlay in the<br />

design is additional, and should take care of any unruly threads that would still try to rear their way<br />

through the both the fill patterns and the columns.<br />

The stitched version of a chef design that combines fill patterns, walk stitches and columns.<br />

§<br />

Hooping<br />

https://www.embroiderydesigns.com/emb_learning/article/559/thickandthinsomanyfabricssomanyways.aspx<br />

Military precision! That’s the term that comes to mind when I think about hooping. Sloppy hooping presents more problems in<br />

2/4

10/28/2016 Thick and Thin: So Many Fabrics...So Many ays W <strong>Embroidery</strong> Article<br />

Military precision! That’s the term that comes to mind when I think about hooping. Sloppy hooping presents more problems in<br />

embroidery than any other oversight, in my opinion.<br />

When a garment is properly hooped, the tension of the fabric will present a firm structure on which to place the design. In the case<br />

of knits, this must be done without stretching the fabric at all.<br />

Achieving an even tension in the hoop is easy enough. Just place the bottom portion of the hoop on the inside of the garment,<br />

centering it where the embroidery is going to be placed. The backing of choice should be between the hoop and the garment. On<br />

the outside of the garment, insert the top portion of the hoop. This placement is easy if you have a hooping aid. If not, the eye works<br />

well, too. Once the hoop is in place, a gentle tug on the fabric outside the hoop will increase the tension of the fabric. It is at this<br />

point that one must be careful not to pull the knits too much! When the hooping is complete, check to make sure that the lines<br />

created by the weave, commonly called the grain of the fabric, are straight in both directions, vertically and horizontally .<br />

Backing and Topping<br />

There are many backings available and experienced embroiderers will easily tell you about their favorites. They are divided into two<br />

categories, cutaway and tearaway . Our backing of choice is most often a medium cutaway . Cutaway backings provide more stability<br />

than tearaway, simply because they do not pull apart in the embroidery process. T earaway backings weaken, especially around the<br />

edges of the design, with each needle penetration. The nice part of using a tearaway , though, is that removal is easy and the inside<br />

of the garment looks nicer and is more comfortable against the skin when there is no unsightly backing left around the edges of a<br />

design.<br />

Because of the properties of the dif ferent types of fabrics in our order , we will choose dif ferent types of backing. Medium tearaway<br />

backings will be suf ficient for the stable fabrics in the twill coats, the bags, and the caps. The CD cases would present a dif ferent<br />

problem in that they cannot be hooped with ordinary methods. They could either be embroidered with a specialty frame or by<br />

placing them on sticky backing using a standard frame.<br />

Knit fabrics need a stronger foundation to prevent movement during the embroidery . In general, a good rule to follow is that the less<br />

stable a fabric is, the more stable the backing must be. The fear when embroidering polo shirts or lightweight T shirts is that the<br />

backing will show through the garment. Another concern is that, in most cases, the embroidery will lie against the skin when the<br />

garment is worn, and very heavy backings are often uncomfortable. Mesh backings are great when the embroiderer needs the<br />

stability of a cutaway backing, but is also concerned that the backing will show through the garment. The mesh is translucent, and<br />

is lightweight, allowing for better draping of the garment than traditional heavier backings.<br />

There are many choices and it takes a bit of research and experimenting to find what works best for you.<br />

Finishing<br />

When my mom was teaching me to sew as a young child, she would always tell me that the inside of the garment should look as<br />

good as the outside. I also remember , when entering the 4H competitions at the local county fairs, the agonizing moments when<br />

the judge would turn that garment inside out and inspect the stitches of every seam, making sure that the construction techniques<br />

were done correctly, that the stitches were even, that the upper and lower tension of the machine were set correctly and that all<br />

ends of the thread were clipped.<br />

This is the same care that should be taken in the finishing of a garment that comes of f the embroidery machine. Backing should be<br />

removed. With tearaway, that is simple. It is usually already cut away by the stitches, and a little tug will remove the excess from the<br />

edges of the design. Cutaway requires more care in that you need to cut close to the design without actually clipping any of the<br />

stitches. As for the rest of the design, the machines should have been properly set before embroidery , but clipping any unsightly<br />

threads will also make the design picture perfect.<br />

…And isn’t that what we are trying to achieve? Picture perfect embroidery on every piece!<br />

More From This Author<br />

Redwork Baby Quilt By Barbara Geer<br />

Redwork Baseball Quilt By Barbara Geer<br />

Play Food By Barbara Geer<br />

Share this project: 0 0 0<br />

https://www.embroiderydesigns.com/emb_learning/article/559/thickandthinsomanyfabricssomanyways.aspx 3/4

10/28/2016 Thick and Thin: So Many Fabrics...So Many ays W <strong>Embroidery</strong> Article<br />

Meet The Author: Barbara Geer<br />

Barbara Geer, Creative Director/Digitizer, Grand Slam Designs, an embroidery stock<br />

design and contract digitizing operation, has been in the decorated apparel industry<br />

since 1990. She is a popular speaker at commercial decorated apparel and home<br />

embroidery events. She also is a frequent contributor to commercial and home<br />

embroidery publications such as EMB, Stitches, and Printwear . You may reach Barbara<br />

at 2182223501; email barb@grandslamdesigns.com or visit her W eb site at<br />

www.grandslamdesigns.com.<br />

https://www.embroiderydesigns.com/emb_learning/article/559/thickandthinsomanyfabricssomanyways.aspx 4/4

Pattern Fill Angles<br />

TruE 3 Create<br />

Angle<br />

0º<br />

45º<br />

90º<br />

135º<br />

Pattern Fill areas created with Pattern 2 and Density 3.<br />

Vary the angle of stitching in QuickStitch and Freehand Fill areas to any degree. Altering the fill<br />

angle changes the way light reflects off the stitching, for a different look and texture.<br />

This effect is different from the pattern in continuous satin, which follows the contours of the<br />

shape.<br />

To see all the available fill patterns, refer to the Fill Patterns Guide.<br />

Pattern Fill Angles TruE 3 Create Stitch Guide 1

Pattern Fill Density<br />

TruE 3 Create<br />

Density<br />

2<br />

4<br />

6<br />

8<br />

Pattern Fill areas created with Pattern 5 and Angle 135º.<br />

Density is determined by the distance between stitches. The lower the number, the more<br />

stitches in an area or the closer together the stitches are.<br />

Select from 2 to 40 for all fill areas in a design or specific fill areas.<br />

Use gradient density with fill patterns for beautiful shading effects.<br />

Low, Medium or High Underlay may be selected for individual fill areas. This is different from<br />

Design Underlay for QuickCreate embroideries in the QuickCreate Assistant, which creates a<br />

layer of underlay for the whole design before any other part of the design is created. Hence, it is<br />

possible to have both Design Underlay and then individual areas with underlay in the same design.<br />

Pattern Fill Density TruE 3 Create Stitch Guide 2

Multigradient Density<br />

TruE 3 Create<br />

Multigradient<br />

single color<br />

Multigradient<br />

Multicolor<br />

Pattern and Spiral fill areas may have density gradients. Pattern fills may also have multicolor<br />

gradient density.<br />

Use Single Color Gradient to change the density across a fill with only one color. Set a value for<br />

the start and end density markers for the fill. Add multiple markers for a more complex pattern.<br />

Use Multicolor Gradient to change the color across a fill. Set colors for any number of markers<br />

for the fill, and the color gradually changes between them.<br />

Multigradient Density TruE 3 Create Stitch Guide 3

Fill Areas with Line<br />

TruE 3 Create<br />

Border Width<br />

3mm<br />

6mm<br />

9mm<br />

Fill areas created with Pattern 12, Density 3 and Angle 0º.<br />

Any fill area (whether Pattern Fill or one of the other types such as Motif or Shape Fill) may have<br />

a satin, stitch or motif line surrounding it. Appliqué options may also be used.<br />

Select satin line width between 1 and 12mm. Select the underlay option to automatically generate<br />

edge walk underlay when the border width is 2mm or more. Select satin line density between 2<br />

and 15.<br />

Fill Areas with Line TruE 3 Create Stitch Guide 4

Compensation<br />

Compensation Satin or Fill<br />

TruE 3 Create<br />

0<br />

20<br />

Because some stitches pull the fabric along their length, rows of stitching that look close together<br />

on the computer screen may have gaps between them when embroidered. Compensation<br />

overcomes this.<br />

Add compensation to individual areas of a design or a whole design.<br />

Select from 0 to 30 for satin, 0 to 20 for fill.<br />

This feature is especially useful on heavier fabrics.<br />

Compensation is set automatically for QuickCreate embroideries created in the QuickCreate<br />

Assistant, according to choices in the Fabric and Stitch Options.<br />

Compensation Satin or Fill TruE 3 Create Stitch Guide 5

Motif Fill Areas<br />

Motif and Other Fill Effects<br />

TruE 3 Create<br />

Single Motif with<br />

Satin Line<br />

Two Motifs<br />

Created in TruE 3 Create as motif fill areas. Choose any single motif or any two motifs to fill<br />

the area. Adjust motif size and orientation. Horizontally and vertically adjust gap and spacing.<br />

For a full list of the hundreds of motifs available, refer to the Motif Guides.<br />

Other Fill Areas<br />

Curved QuiltStipple<br />

Fill<br />

Radial Fill<br />

Spiral with Gradient<br />

Density<br />

Crosshatch Fill;<br />

Double with Zigzag<br />

Return<br />

Contour Fill<br />

Shape Fill with Motifs<br />

and Border<br />

MultiWave Fill<br />

Echo Fill with External<br />

and Internal lines and<br />

a border<br />

QuiltStipple is available as curved or straight style, with adjustable spacing. Crosshatch Fill is<br />

available as diamond, square, parallel or with a choice of angles. With MultiWave Fill, adjust the<br />

density, or use a motif. Adjust density and move the origin for Radial, Spiral and Shape fills for<br />

different effects. Hundreds of fill effects are available.<br />

Motif and Other Fill Effects TruE 3 Create Stitch Guide 6

TruE 3 Create<br />

Shape Fill<br />

1 2 3<br />

4 5<br />

6 7 8<br />

9 10<br />

Shape Fill Areas created in TruE 3 Create at Density 14.<br />

Satin Line width is 2.0mm with Density 4.<br />

Shape Fill TruE 3 Create Stitch Guide 7

TruE 3 Create<br />

11 12 13<br />

14 15<br />

16 17 18<br />

19 20<br />

Shape Fill Areas created in TruE 3 Create at Density 14.<br />

Satin Line width is 2.0mm with Density 4.<br />

Shape Fill TruE 3 Create Stitch Guide 8

TruE 3 Create<br />

21 22 23<br />

24 25<br />

26 27 28<br />

29 30<br />

Shape Fill Areas created in TruE 3 Create at Density 14.<br />

Satin Line width is 2.0mm with Density 4.<br />

Shape Fill TruE 3 Create Stitch Guide 9

TruE 3 Create<br />

31 32 33<br />

34 35<br />

36 37 38<br />

39 40<br />

Shape Fill Areas created in TruE 3 Create at Density 14.<br />

Satin Line width is 2.0mm with Density 4.<br />

Shape Fill TruE 3 Create Stitch Guide 10

TruE 3 Create<br />

41 42 43<br />

44 45<br />

46 47 48<br />

49 50<br />

Shape Fill Areas created in TruE 3 Create at Density 14.<br />

Satin Line width is 2.0mm with Density 4.<br />

Shape Fill TruE 3 Create Stitch Guide 11

TruE 3 Create<br />

51 52 53<br />

54 55<br />

56 57 58<br />

59 60<br />

Shape Fill Areas created in TruE 3 Create at Density 14.<br />

Satin Line width is 2.0mm with Density 4.<br />

Shape Fill TruE 3 Create Stitch Guide 12

TruE 3 Create<br />

61 62 63<br />

64 65<br />

66 67 68<br />

69 70<br />

Shape Fill Areas created in TruE 3 Create at Density 14.<br />

Satin Line width is 2.0mm with Density 4.<br />

Shape Fill TruE 3 Create Stitch Guide 13

TruE 3 Create<br />

71 72 73<br />

74 75<br />

Shape Fill Areas created in TruE 3 Create at Density 14.<br />

Satin Line width is 2.0mm with Density 4.<br />

Shape Fill TruE 3 Create Stitch Guide 14

TruE 3 Create<br />

Density<br />

Satin Areas<br />

Density 4 Density 6<br />

Density 9 Density 12<br />

Density may be varied between 2 and 40 and compensation between 0 and 30.<br />

Zigzag and edge walk underlay are available, suitable for use with denser satin areas.<br />

Satin Fill Pattern<br />

No Satin Pattern Satin Pattern 6<br />

Satin Pattern 9<br />

Stitch angle lines show<br />

the angle of stitches<br />

across the area<br />

Satin areas may be created in any of the 12 satin fill patterns.<br />

The satin fill pattern is perpendicular to the stitch angle lines in the satin area. Stitch angle lines<br />

may be adjusted as desired.<br />

Satin Areas TruE 3 Create Stitch Guide 15

Continuous Columns<br />

TruE 3 Create<br />

Continuous Satin<br />

Feathered Satin<br />

Richelieu Bars<br />

Tapered Motifs<br />

Place alternate points to define a continuous column of any length. Four types of continuous<br />

column are available:<br />

Continuous Satin<br />

Use Continuous Satin to create a straight or curved column of parallel stitches. The column may<br />

be of any length.<br />

Feathered Satin<br />

For lifelike realistic feathers or fur, use Feathered Satin, where the start and end points of the<br />

stitches are random rather than all parallel.<br />

Richelieu Bars<br />

Use Richelieu Bars to create a column of short sections of satin perpendicular to the direction of<br />

the column, typically used for cutwork designs. Choose the number of bars, and the width of the<br />

satin.<br />

Tapered Motifs<br />

Use Tapered Motifs to create a line of motifs that vary in size according to the width of the<br />

column.<br />

Tapered motifs are often used in lace designs.<br />

Continuous Columns TruE 3 Create Stitch Guide 16

Satin Fill Patterns<br />

TruE 3 Create<br />

Pattern Density is 4<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5<br />

6<br />

7<br />

8<br />

9<br />

10<br />

11<br />

12<br />

All satin (satin areas and continuous satin) may be created in any of the 12 satin fill patterns. For<br />

continuous satin, the pattern follows the contours of the shape of the satin column.<br />

Density may be varied between 2 and 40 and compensation between 0 and 30.<br />

Satin Fill Patterns TruE 3 Create Stitch Guide 17

TruE 3 Create<br />

Satin Density<br />

Satin Density<br />

4<br />

6<br />

10<br />

15<br />

Density is determined by the gap between stitches. The lower the number, the more stitches in<br />

an area; that is, the closer together the stitches are.<br />

Select from 2 to 40 for satin areas and continuous column satin. Select from 2 to 15 for satin<br />

lines.<br />

To embroider on heavy knitwear or terrycloth, select a lower density value for more stitches<br />

than on lighter weight fabric such as twill.<br />

For embroidery with light colored thread on a dark fabric select a lower density value for better<br />

coverage.<br />

Satin Density TruE 3 Create Stitch Guide 18

Feathered Satin<br />

TruE 3 Create<br />

Stitch Length<br />

Density<br />

2mm<br />

4 — Feather Both<br />

Sides<br />

4mm<br />

8 — Feather Both<br />

Sides<br />

6mm<br />

12 — Feather Side A<br />

(First point placed on<br />

top edge)<br />

8mm<br />

16 — Feather Side B<br />

(First point placed on<br />

top edge)<br />

Create special embroidery effects with random edge satin stitches.<br />

Add texture and lifelike stitching to fur and feathers in animal designs, landscape and wearable art.<br />

Choose feathering on one or both sides. Set length of stitches from 2 to 30mm. Select density<br />

from 2 to 40.<br />

Feathered Satin TruE 3 Create Stitch Guide 19

TruE 3 Create<br />

Line Types<br />

2mm<br />

Running Stitch<br />

4mm<br />

6mm<br />

2mm<br />

Double Stitch<br />

4mm<br />

6mm<br />

2mm<br />

Double Stitch with<br />

Zigzag Return<br />

4mm<br />

6mm<br />

2mm<br />

Triple Stitch<br />

4mm<br />

6mm<br />

Running Stitch<br />

Create as part of a design or to stabilize sections of stitching.<br />

Double Stitch<br />

Most often created to outline or mark out a design.<br />

Double Stitch with Zigzag Return<br />

Gives stability to lace designs; an option for Crosshatch Fill.<br />

Triple Stitch<br />

Create quilting designs and other techniques where a bold stitched line is desired.<br />

Line Types TruE 3 Create Stitch Guide 20

Satin vs. Fill Stitch | Applique Cafe Blog<br />

about:reader?url=http://appliquecafeblog.com/satin-fill-stitch/<br />

1 of 4 10/28/2016 12:04 AM<br />

appliquecafeblog.com<br />

Rosemary<br />

I had someone ask me after my Stabilizer post yesterday what the difference is between satin stitch and fill<br />

stitch. I mentioned that when I monogram towels, I like to use a fill stitch (and that is my personal preference,<br />

not a requirement). Maybe this will help? Basically a satin stitch is the same as the finishing stitch on appliques.<br />

It’s a back and forth FLAT stitch and this is what it looks like below. When you see the fill stitch photo hopefully<br />

you will see the difference! This is Monogram Wizard Plus Serif Block.<br />

Here is a 3 letter monogram done in a satin stitch. I use Monogram Wizard Plus and the below font is<br />

Arabesque. When you’re using MWP, it gives you the option of fill stitch or satin stitch for your monogram<br />

(below ‘system functions’ box where you save your files). If you buy font files off the internet, then they may<br />

come either way (probably) depending on how big the letters are.

Satin vs. Fill Stitch | Applique Cafe Blog<br />

about:reader?url=http://appliquecafeblog.com/satin-fill-stitch/<br />

2 of 4 10/28/2016 12:04 AM<br />

Here is a fill stitch and this is also MWP Serif Block font. As you can see, it’s not a back and forth stitch, but<br />

rather a filled in stitch (hence the name?). Hopefully you see the difference? Fill stitch requires more thread<br />

and takes longer to sew, but for certain projects I prefer a fill stitch (like I mentioned ~ towels, blankets). It<br />

really depends on how big the monogram is – if it’s big and you’re using satin stitch, then you run the risk of the<br />

thread looping or getting caught or pulled.

Satin vs. Fill Stitch | Applique Cafe Blog<br />

about:reader?url=http://appliquecafeblog.com/satin-fill-stitch/<br />

3 of 4 10/28/2016 12:04 AM<br />

Here is a fill stitch 3 letter monogram ~ same as above MWP Arabesque. As you may see below, parts of the R<br />

look a little more like satin and it does sew that way if the font is thin enough. I upped the boldness of these so<br />

you could really see how filled in the monogram was.<br />

Hopefully that makes sense?

Satin vs. Fill Stitch | Applique Cafe Blog<br />

about:reader?url=http://appliquecafeblog.com/satin-fill-stitch/<br />

4 of 4 10/28/2016 12:04 AM<br />

Like I said, MWP gives you the option of satin or fill and some other programs may do the same. But, if you<br />

purchase fonts from websites who sell them, they usually come satin and/or fill but you can’t change them.<br />

Here is a font from www.jolsonsdesigns.com, and as you can see the bigger letters are fill and the smaller letters<br />

are satin. Here is the font: http://www.jolsonsdesigns.com/servlet/the-330/305-Georgie-Girl-Satin/Detail.<br />

I have several fonts from Jolson’s and they all stitch great! They are really affordable too and I just found this<br />

picture on their website! This may better explain what I’m trying to explain:<br />

I have also heard the term ‘column stitch’ and based on what I’ve read, that is another name for a satin stitch. I<br />

have also seen fonts that are so thick the sew in 2 side-by-side attached columns, so I guess that term could<br />

apply there as well!

<strong>Embroidery</strong> Settings<br />

Normal Fill Recipe<br />

Normal fill is used to fill irregular or<br />

complex shapes. Normal fill utilizes a<br />

common stitch inclination and almost<br />

always will use some sort of step as the<br />

stitch type. This fill method is sometimes<br />

referred to as Complex Fill and is the most<br />

common method used to define large<br />

areas.<br />

• Stitch Type:<br />

The stitch type selection selects how the object will be filled. Different stitch types are used to<br />

give a specific appearance to the embroidery.<br />

➢<br />

Satin:<br />

Satin stitches are stitches that travel from one edge of the<br />

object to the opposite edge of the object in one step. A<br />

normal satin uses one straight stitch and one angled stitch. A<br />

Zig Zag Satin uses angle stitches of equal length. The<br />

maximum effective distance for a satin stitches is about 6mm<br />

for general embroidery. Satin stitches longer than this tend to<br />

pull out and unravel<br />

➢<br />

Step:<br />

Step stitches appear much flatter and can fill large areas as<br />

the distance is divided in to steps of a predetermined<br />

distance.(Step Length) Step fills are created by using<br />

parallel rows of stitching. Different effects can be achieved<br />

by changing the step length in a fill area There are<br />

practically unlimited possibilities for filling with step fill

• Hole Stitch Type:<br />

The type of stitch that applies to the hole. Normally holes are voided of stitches or empty.<br />

However , there are instances when you would want the hole filled with stitches of a different<br />

type.<br />

Note: Only compatible stitch types are allowed as the hole stitches sew in line with the parent block<br />

stitches. For instance, you cannot use step satin as the fill area with a hole stitch type of Motif as these<br />

stitches use different densities.<br />

General Settings:<br />

The general settings are parameters that apply globally to the recipe selected.<br />

• Respect Modifications:<br />

A block of stitches may contain several sub layers, the<br />

system provides the ability to edit the sub layers outlines.<br />

This setting keeps the sub layers changes when the top<br />

layer is later edited or changed. If this setting is unchecked<br />

and the top layer is edited, the sub layers that were<br />

changed will snap back to their original shape. Sub layers<br />

could include such parts as underlay or outline stitches.<br />

These sub layers are discussed in detail in the Advanced<br />

Area Edit Section.<br />

• Overlap:<br />

Determines how many stitches or rows of stitches overlap in a fill<br />

area or column. In the simple illustration at the right, the digitizer<br />

determined they wanted the stitching to start on the left and finish<br />

in the center. The system starts stitching up to the point where<br />

the end point in determined, then makes a ½ step to the center<br />

of the column and walks to the right where it stitches back to the<br />

center point C. Depending on the type of fabric that this will be<br />