BCJ_WINTER17 Digital Edition

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

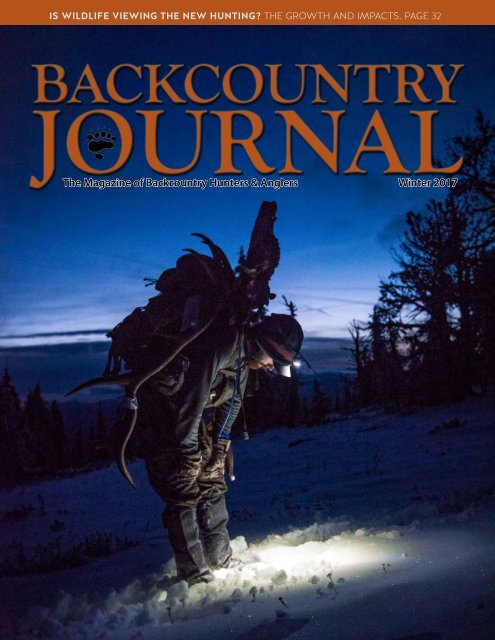

IS WILDLIFE VIEWING THE NEW HUNTING? THE GROWTH AND IMPACTS. PAGE 32<br />

BACKCOUNTRY<br />

JOURNAL<br />

The Magazine of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers Winter 2017

PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE<br />

MOUNTAIN TRYST<br />

HUNTING MAPS FOR EVERY DEVICE<br />

#HUNTSMARTER<br />

WITH THE NEW ERA OF GPS<br />

Search onXmaps<br />

View maps online at huntinggpsmaps.com/web<br />

FINDING NEW LOVE AT 41 IS A GIFT.<br />

When I first saw her, I knew she was the<br />

one. Steep, open slopes with talus slides, old<br />

growth Ponderosa pines and Douglas firs –<br />

a real beauty. I explored every ridge and valley,<br />

finding an elaborate network of sheep<br />

highways and bedding areas. Eventually I<br />

set up camp directly beneath her.<br />

Every morning I rose to gaze upon her<br />

loveliness. Sometimes a veil of fog obscured<br />

her. Other mornings she glowed as light<br />

crept into the valley. But without fail, she<br />

held bighorn sheep. At first only small bands<br />

of ewes, lambs and young rams. Then, larger<br />

groups. Finally, one memorable day, she<br />

delivered to us a group of 30 sheep with five<br />

rams, one of whom had horns that plunged<br />

below his jawline. We named him Dropjaw.<br />

The stalk went badly. Maybe if I had been<br />

more patient instead of pushing them into<br />

the darkness they would have been on the<br />

open face in the morning and I would have<br />

had another chance. But the mountain was<br />

with me through the sweat, the toil and the<br />

ever-present rain. She held me as I slept in<br />

the mid-afternoon sun. She helped me gain<br />

strong lungs and legs with her unforgiving<br />

pitch. And once we had a spat.<br />

Early one morning, I caught a glimpse of<br />

Dropjaw. Almost blindly I raced to the top.<br />

The sheep eluded me and I headed to familiar<br />

ground in search of other bands. I found<br />

two. There were none I wanted to shoot,<br />

but I practiced my approach anyway. Doing<br />

my best not to look like a predator I crept<br />

to 200 yards. Suddenly, a ram emerged.<br />

I found a rest against a fat Ponderosa,<br />

raised my rifle, drew a bead, took the safety<br />

off, breathed out and counted one, two …<br />

and then my rest broke just as I pulled the<br />

trigger. I tumbled face first down the slope,<br />

the butt of the gun hitting the ground at<br />

the same time my chin found the scope.<br />

When the dust settled, there were no sheep<br />

to be found.<br />

After collecting myself, I wondered why<br />

my mountain had reacted this way. It was<br />

getting dark and my mind was getting darker.<br />

Had I wounded a majestic animal? Was<br />

I going to seal the deal? Or was I destined<br />

only for close calls? I spent hours searching<br />

for blood before returning to camp.<br />

That was the low point of my hunt. Not<br />

only did I miss a perfect opportunity; I also<br />

might have wounded a fine ram. I tossed<br />

and turned all night before continuing the<br />

search the next day. Finally, late in the afternoon,<br />

I came to peace with the fact that<br />

that I’d missed. In the fading light, I turned<br />

to the mountain. Thank you, I whispered.<br />

Thank you for being patient and helping<br />

me work through my imprudence. I slept<br />

better that night in part due to the sound<br />

of rain on my tipi. The deluge stopped an<br />

hour before light, just as if I’d asked.<br />

The next morning, she didn’t reveal a single<br />

sheep. My cousin arrived after sunrise,<br />

full of energy. Then the sun broke through<br />

the clouds, and there they were. That’s<br />

when I saw him, a ram all by himself headed<br />

north on the slope. I had a good idea<br />

where he was headed. He disappeared into<br />

the dark timber, and we hustled to intercept.<br />

A rainbow appeared to show us the<br />

way. I was so focused on my destination<br />

that I barely heard my cousin. He finally<br />

had to yell to alert me to the fact that 200<br />

yards above us was a beautiful ram.<br />

I removed my backpack, laid down and<br />

took aim. The ram was quartering away and<br />

then unexpectedly turned broadside at 220.<br />

Without thinking, I thumbed the safety<br />

and squeezed the trigger. It was over. After<br />

16 days of hunting, 14 years applying for<br />

the tag and a lifetime of desire, I’d killed a<br />

bighorn sheep.<br />

As we roasted tenderloins over an open<br />

flame that night I looked up at her once<br />

again. Despite all the time I spent tromping<br />

around my beautiful mountain, I shot<br />

my ram on her neighbor. But that couldn’t<br />

break our bond.<br />

She belongs to all of us, and during my<br />

hunt I shared her with friends, co-workers,<br />

my cousin and other hunters. I shared her<br />

with gray jays, mule deer, elk, three-toed<br />

woodpeckers and pikas. Her name is Sandstone,<br />

and she resides in the Lolo National<br />

Forest up the Rock Creek Road.<br />

She belongs to me just as much as she<br />

belongs to anyone reading this. She defines<br />

our public lands heritage, and my resolve<br />

couldn’t be stronger to protect her.<br />

BHA’s leader with his hard-won, 2016 Montana<br />

bighorn ram, taken on public lands.<br />

Onward and Upward,<br />

Land Tawney<br />

President & CEO<br />

WINTER 2017 BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 3

WHAT IS BHA?<br />

BACKCOUNTRY HUNTERS &<br />

Anglers is a North American conservation<br />

nonprofit 501(c)(3) dedicated<br />

to the conservation of backcountry<br />

fish and wildlife habitat, sustaining<br />

and expanding access to important<br />

lands and waters, and upholding<br />

the principles of fair chase. This is<br />

our quarterly magazine. We have<br />

members across the continent, with<br />

chapters representing 25 states and<br />

provinces. We fight to maintain and<br />

enhance the backcountry values<br />

that define our passions: challenge,<br />

solitude and beauty. Join us. Become<br />

part of the sportsmen’s voice<br />

for our wild public lands, waters and<br />

wildlife. Sign up at www.backcountryhunters.org.<br />

RENDEZVOUS!<br />

TICKETS FOR THE 2017 BHA North<br />

American Rendezvous, April 7-9 in<br />

Missoula, Montana, will go on sale in<br />

early January. A complete schedule<br />

of events, seminars and speakers will<br />

be released soon as well. Confirmed<br />

speakers include national sportsmen<br />

leaders such as TV hosts Steven<br />

Rinella and Randy Newberg, and fly<br />

fishing innovator Kelly Galloup.<br />

The popular Field to Table Dinner<br />

will be returning this year, with five<br />

gourmet chefs preparing wild game<br />

dishes in a camp-style setting. Read<br />

a snowshoe hare recipe by one of the<br />

chefs, Chol McGlynn, on page 17.<br />

Get your North American<br />

Rendezvous tickets early; spots are<br />

limited and will sell out quickly. To<br />

learn more, visit backcountryhunters.<br />

org/rendezvous_2017.<br />

THE SPORTSMEN’S VOICE FOR OUR WILD PUBLIC LANDS, WATERS AND WILDLIFE<br />

Ryan Busse (Montana) Chairman<br />

Ben Long (Montana) Vice Chairman<br />

Sean Carriere (Idaho) Treasurer<br />

Sean Clarkson (Virginia) Secretary<br />

Jay Banta (Utah)<br />

Ben Bulis (Montana)<br />

President & CEO<br />

Land Tawney, tawney@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Campus Outreach Coordinator<br />

Sawyer Connelly, sawyer@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Great Lakes Coordinator<br />

Will Jenkins, will@thewilltohunt.com<br />

Backcountry Journal Editor<br />

Sam Lungren, sam@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Operations Director<br />

Frankie McBurney Olson, frankie@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Membership Coordinator<br />

Ryan Silcox, ryan@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Interns: Travis Cashion, Jack Cholewa, Trey Curtiss,<br />

Alex Kim, Brian Ohlen, Seth Pelkey, Liam Rossier<br />

BHA LEGACY PARTNERS<br />

The following Legacy Partners have committed<br />

$1000 or more to BHA for the next three years. To<br />

find out how you can become a Legacy Partner,<br />

please contact grant@backcountryhunters.org.<br />

Bendrix Bailey, Mike Beagle, Cidney Brown, Dave<br />

Cline, Todd DeBonis, Dan Edwards, Blake Fischer,<br />

Whit Fosburgh, Stephen Graf, Ryan Huckeby, Richard<br />

Kacin, Ted Koch, Peter Lupsha, Robert Magill, Chol<br />

McGlynn, Nick Nichols, William Rahr, Adam Ratner,<br />

Robert Tammen, Karl Van Calcar, Michael Verville,<br />

Barry Whitehill, J.R. Young, Dr. Renee Young<br />

JOURNAL CONTRIBUTORS<br />

BOARD OF DIRECTORS<br />

STAFF<br />

Carol Bibler, Tony Bynum, Sara Evans-Kirol, Michael<br />

Furtman, Bruce Gordon, Hilary Hutcheson, Ken<br />

Keffer, Randy King, David Lien, Ben Long, Jess<br />

McGlothlin, Chol McGlynn, Scott Morrison, Brian<br />

Ohlen, Rob Parkins, Edward Putnam, Paul Queneau,<br />

Ron Rohrbaugh Jr., Tim Romano, Jay Sheffield, David<br />

Stalling, Nick Trehearne, Alec Underwood, Jacob<br />

VanHouten, Jim Watson and Barry Whitehill<br />

Cover photo: Sam Averett<br />

Backcountry Journal writing and photography queries,<br />

submissions and advertising questions contact<br />

sam@backcountryhunters.org<br />

BHA HEADQUARTERS<br />

P.O. Box 9257, Missoula, MT 59807<br />

www.backcountryhunters.org<br />

admin@backcountryhunters.org<br />

(406) 926-1908<br />

Ted Koch (New Mexico)<br />

T. Edward Nickens (North Carolina)<br />

Mike Schoby (Montana)<br />

Rachel Vandevoort (Montana)<br />

Michael Beagle (Oregon) President Emeritus<br />

Joel Webster (Montana) Chairman Emeritus<br />

Donor and Corporate Relations Manager<br />

Grant Alban, grant@backcountryhunters.org<br />

State Policy Director<br />

Tim Brass, tim@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Conservation Director<br />

John Gale, gale@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Montana Chapter Coordinator<br />

Jeff Lukas, jeff@bakcountryhunters.org<br />

Communications Director<br />

Katie McKalip, mckalip@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Northwest Outreach Coordinator<br />

Jesse Salsberry, jesse@crowfly.cc<br />

Chapter Coordinator<br />

Ty Stubblefield, ty@backcountryhunters.org<br />

CONTACT CHAPTER CHAIRS<br />

alaska@backcountryhunters.org<br />

arizona@backcountryhunters.org<br />

britishcolumbia@backcountryhunters.org<br />

california@backcountryhunters.org<br />

colorado@backcountryhunters.org<br />

idaho@backcountryhunters.org<br />

michigan@backcountryhunters.org<br />

minnesota@backcountryhunters.org<br />

montana@backcountryhunters.org<br />

nevada@backcountryhunters.org<br />

newengland@backcountryhunters.org<br />

newmexico@backcountryhunters.org<br />

newyork@backcountryhunters.org<br />

oregon@backcountryhunters.org<br />

pennsylvania@backcountryhunters.org<br />

texas@backcountryhunters.org<br />

utah@backcountryhunters.org<br />

washington@backcountryhunters.org<br />

wisconsin@backcountryhunters.org<br />

wyoming@backcountryhunters.org<br />

JOIN THE CONVERSATION<br />

facebook.com/backcountryhabitat<br />

plus.google.com/+BackcountryHuntersAnglers<br />

twitter.com/Backcountry_H_A<br />

youtube.com/BackcountryHunters1<br />

instagram.com/backcountryhunters<br />

Bruce Gordon photo<br />

BY BRIAN OHLEN<br />

IMAGINE MOUNTAINSIDES SPLASHED YELLOW by aspen<br />

leaves. A stream filled with cold, clean water gurgles on its way<br />

down from the high country. An elk bugles across the drainage,<br />

cutting through the crisp air of a September morning. Not a road,<br />

engine or cell tower in sight or earshot. Those lucky enough to<br />

frequent the Thompson Divide and Gunnison Basin know these<br />

moments well. Located in west-central Colorado and comprised<br />

largely of public lands, these two bordering geographic regions<br />

just may be a backcountry explorer’s paradise. Native cutthroat<br />

trout, trophy mule deer, high success rates among elk hunters –<br />

and with 80 percent of Gunnison County being public land –<br />

these opportunities are free to anyone willing to work for them.<br />

The combination of diverse habitat, roadless areas and lack of human<br />

presence have nurtured one of the nation’s greatest elk herds.<br />

It’s no wonder that the former world record bull was taken on the<br />

slopes of Gunnison Basin.<br />

In recent years, the Thompson Divide and Gunnison Basin have<br />

seen growing pressures from oil and gas exploration, increased<br />

motorized recreation, road building and land development. Left<br />

unchallenged, these risks could result in serious habitat fragmentation<br />

and threaten the landscapes deer and elk need to survive.<br />

Rallied by Colorado BHA Chapter leaders like Adam Gall and<br />

Tony Prendergast, BHA members and other sportsmen are trying<br />

to conserve these special areas. As the owner of Timber to Table<br />

Guide Service, Adam has a vested interest in the Thompson Divide;<br />

it’s his backyard and workplace. Through meetings with Sen.<br />

Michael Bennet, op-eds in local papers and representing BHA on<br />

public land working groups, Adam is helping spread the word<br />

that the benefits of protecting the Thompson Divide far outweigh<br />

those of mineral extraction.<br />

“I’m not anti-drilling,” Adam said. “But there are certain places<br />

where it doesn’t make sense in terms of what you’re going to get<br />

out of it from an economic standpoint – and also what it’s going<br />

to do to the industries that already exist.”<br />

Similarly, Tony Prendergast of Landsend Outfitters has played<br />

a pivotal role for long-term protection for the Gunnison Basin.<br />

As the BHA representative to the Gunnison Public Land Initiative,<br />

Tony is working with county commissioners, ranchers, recreationists<br />

and local communities to create balanced legislation.<br />

“It’s hard for people to see the big picture of the ecosystem,”<br />

Tony said. “We bring perspective about how it is all connected<br />

YOUR BACKCOUNTRY<br />

GUNNISON BASIN AND THE THOMPSON DIVIDE, COLORADO<br />

and how important hunting is to the economy of this region.”<br />

Thankfully, there’s a common understanding that conservation<br />

of the area’s rich wildlife resources and vast tracts of undeveloped<br />

lands are worth standing up for. A host of of community members<br />

ranging from sportsmen, ranchers, hikers, bikers to motorized<br />

users have joined the Gunnison Public Lands Initiative and<br />

Thompson Divide Coalition. They are working towards conserving<br />

high value lands in the region through a variety of land management<br />

designations, including wilderness additions, wildlife-focused<br />

special management areas and mineral lease withdrawals.<br />

Tony and Adam are also working hard to protect their hunting<br />

and fishing heritage by bringing new hunters into the fold. Adam<br />

offers guided, educational hunts for women, youth and first-time<br />

hunters, teaching them everything from the kill to butchering,<br />

processing and cooking wild game meat. He donated a hunt for<br />

auction at the 2016 BHA Rendezvous.<br />

“It’s not about 300 inch bulls every time you go out. It’s about<br />

putting some of the best meat in the world in the freezer to feed<br />

your family,” Adam said. “If every year I can introduce five or six<br />

people to hunting, and they keep hunting on public lands for the<br />

rest of their lives, they have families, and share that with their<br />

kids, now you have more people vested in public lands who will<br />

speak up for them.”<br />

Tony also sees a need to include educational components in<br />

backcountry outfitting. In addition to offering traditional guided<br />

hunts and drop camps, he recently added instructional trips<br />

focused horse packing, game tracking, backcountry survival and<br />

other valuable skills.<br />

Whether introduced to hunting and fishing by a guide, family<br />

member or mentor, we’ve all learned certain things from our time<br />

in the backcountry: self-sufficiency, responsibility and an ethic<br />

that respects the environment and the animals it supports. The<br />

conservation efforts underway in west-central Colorado demonstrate<br />

these values in action, where community-grown solutions<br />

improve public lands management in a way that respects everyone<br />

at the table. The Interior Department heard the unified outcry<br />

from sportsmen, ranchers and community members and withdrew<br />

25 oil and gas leases in the Thompson Divide this November<br />

– a good start toward the goals of these conservation coalitions.<br />

Brian is the Backcountry Journal intern and lives in Cody, Wyoming.<br />

He is leaving soon for a three-month bike tour of the West Coast<br />

to fish for steelhead.<br />

WINTER 2017 BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 5

BHA HEADQUARTERS<br />

BACKCOUNTRY BOUNTY<br />

CALL FOR NOMINATIONS FOR BHA’S ANNUAL AWARDS!<br />

WHO’S YOUR CONSERVATION HERO? Backcountry Hunters & Anglers’ Awards Committee is seeking nominations for our annual<br />

awards, recognizing outstanding conservation efforts on behalf of North America’s backcountry. These honors will be bestowed at<br />

the 2017 Rendezvous in Missoula in April.<br />

BHA announced a new award at the 2016 Rendezvous. In partnership with Orion - The Hunter’s Institute, BHA launched the Jim<br />

Posewitz Award for a group or individual who has advanced ethical, responsible behavior in the hunting and fishing fields by example,<br />

leadership or education. Other award categories include:<br />

• The Aldo Leopold Award, for outstanding effort conserving terrestrial wildlife habitat<br />

• The Sigurd F. Olson Award, for outstanding effort conserving rivers, lakes or wetland habitat<br />

• The Ted Trueblood Award, for outstanding communication on behalf of backcountry habitat and values<br />

• The Mike Beagle-Chairman’s Award, for outstanding effort on behalf of BHA<br />

• The Larry Fischer Award, for outstanding corporate contribution to BHA’s mission<br />

• The George Bird Grinnell Award, for the outstanding BHA chapter of the year<br />

The final deadline for nominations is Friday, Feb. 26. Submit to Jay Banta, (435) 496-3600 or groverite@gmail.com.<br />

HUNTING PHOTO CONTEST WINNERS<br />

STAFF CHANGES<br />

BACKCOUNTRY HUNTERS & ANGLERS continues to grow<br />

and evolve with several recent changes on the staff roster. BHA<br />

hired Will Jenkins as the Upper Great Lakes outreach coordinator.<br />

Born and raised in Virginia,<br />

Will now resides in Hudson,<br />

Wisconsin, with his wife<br />

and three kids. Growing up he<br />

hunted whitetails and turkey<br />

with family. Upon moving to<br />

the Midwest, his love for public<br />

lands and the backcountry was<br />

cemented after chasing South<br />

Dakota mule deer.<br />

Will has been a freelance outdoor writer and blogger for five<br />

years, writing for various publications about hunting, fishing and<br />

conservation. He will be helping with various programs such as<br />

the Adult Learn to Hunt program with Minnesota DNR and the<br />

effort to protect the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness<br />

from sulfide mining.<br />

BHA also hired Jesse Salsberry to be the Northwest outreach<br />

coordinator. Raised in the Pacific Northwest, Jesse was brought<br />

up with a deep appreciation for the wild things and places that<br />

surrounded him. After graduating from Washington State University<br />

with a degree in digital<br />

technology and culture,<br />

Jesse dove into video production.<br />

Cutting his teeth in the<br />

Portland, Oregon area, Jesse<br />

worked with some of the most<br />

innovative brands and creative<br />

agencies in the world.<br />

Now as the creative director<br />

of his own video production<br />

agency, Crowfly Creative, Jesse continues to find ways to bridge<br />

the two passions of his life: video and the outdoors. Jesse, his wife<br />

and kids live in Vancouver, Washington.<br />

Caitlin Twohig-Thompson bid farewell to BHA this fall. Caitlin<br />

began working at BHA in 2013 as Land Tawney’s executive assistant,<br />

shortly after he assumed the role of executive director. As<br />

the organization grew, Caitlin took on a variety of responsibilities<br />

such as planning the North American Rendezvous, rebuilding the<br />

BHA website, managing corporate partnerships and overseeing<br />

office operations. “BHA has been a huge part of my life for the<br />

past three years, and I am so sad to say goodbye to the incredible<br />

team and organization,” Caitlin said. “I will still be very involved<br />

at the state level and with the Rendezvous. Thank you to everyone<br />

who made this job so wonderful.”<br />

BHA thanks Caitlin for her years of tireless service for the backcountry<br />

and wishes her the best in her future endeavors!<br />

A big thank you to the photo contest sponsors,<br />

Vortex Optics and First Lite Clothing, and to<br />

everyone who submitted their photography!<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

Hunter: Ian Isaacson, BHA Member Species:<br />

Pronghorn State: Wyoming Method: Rifle<br />

Distance from nearest road: Six miles<br />

Transportation: Foot<br />

Angler: Cody Ling, BHA Member<br />

Species: Lake Trout State: Minnesota Method:<br />

Fly rod Distance from nearest road: 20<br />

miles Transportation: Canoe<br />

Hunter: Riley Buck, BHA Member<br />

Species: Bighorn Sheep State: Idaho<br />

Method: Rifle Distance from nearest road:<br />

Six miles Transportation: Foot<br />

Twin Hunters: Hailey and Riley Tucillo (10),<br />

BHA Members Species: Whitetail and Mule<br />

Deer State: Montana Method: Rifle Distance<br />

nearest road: Half mile Transportation: Foot<br />

Hunter: Erik Bailey, BHA Member<br />

Species: Moose State: Vermont Method:<br />

Compound bow Distance from nearest<br />

road: Two miles Transportation: Foot<br />

Hunter: Ezra Strohmaier (12), BHA Member<br />

Species: Turkey State: Montana Method:<br />

Shotgun Distance from nearest road: One<br />

mile Transportation: Foot<br />

4<br />

5<br />

4<br />

5<br />

First Place, Jason Powell Second Place, Lyn Hoffman Third Place, Travis Birchfield<br />

6<br />

6<br />

6 | BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL WINTER 2017<br />

Send submissions to sam@backcountryhunters.org<br />

WINTER 2017 BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 7

Protect the Backcountry<br />

FACES OF BHA<br />

FOR LIFE<br />

JOIN TODAY AS A BHA LIFETIME MEMBER AND CHOOSE ONE OF THESE GREAT GIFTS<br />

Backcountry Hunters & Anglers is proud to offer an extraordinary opportunity. For a limited time,<br />

receive a FREE Jackson kayak, Seek Outside tent or Kimber firearm with your BHA Life Membership<br />

commitment. There is no better time to act! Become a leading contributor to a community of<br />

like-minded sportsmen and women who truly value the solitude, challenge and freedom of the<br />

backcountry experience. Help us protect and promote our legacy.<br />

THREE GREAT OPTIONS WITH THREE GREAT GIFTS<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

Join for $2500 and get a Jackson Kayaks Kilroy LT (MSRP $1899) or Coosa HD (MSRP<br />

$1799), a Seek Outside 12-man Tipi Tent with liner and XXL stove (MSRP $2135) or<br />

Kimber Mountain Ascent Rifle in .308 Win, .300 WSM, .300 Win Mag, 7mm Rem Mag,<br />

.270 Win, .270 WSM, .280 Ackley Improved or .30-06 Springfield (MSRP $2040)<br />

Join for $1500 and get a Seek Outside 6-man Tipi with large stove and carbon pole<br />

(MSRP $1494) or a Kimber Stainless II .45 ACP pistol (MSRP $998)<br />

Join for $1000 and get a Seek Outside Cimarron Tent Bundle – medium stove and 6.5-foot<br />

stovepipe and stovejack installed (MSRP $1029) or Kimber Micro Carry .380 pistol (MSRP<br />

$651)<br />

IN ADDITION YOU WILL RECEIVE:<br />

• Subscription to quarterly Backcountry Journal<br />

• Recognition in Backcountry Journal<br />

• Assurance that your dollars are helping conserve<br />

valued backcountry hunting and fishing traditions<br />

WELCOME, NEW LIFE MEMBERS!<br />

Tom Brimer<br />

Tom Carmody<br />

Joseph Furia<br />

Jonathan Graham<br />

Russell Grisbeck<br />

Ross Henshaw<br />

Eric Johnson<br />

Bryan Jones<br />

Patrick Knackendoffel<br />

Joe Lang<br />

Rosemarie Larson<br />

Daniel Laughlin<br />

Mark Mattaini<br />

Brian McElrea<br />

Andrew McLain<br />

Andrew Monaghan<br />

Trace Moorhead<br />

Brian Olson<br />

Rick Potts<br />

Greg Pearson<br />

Brian Preston<br />

Charles Reasoner<br />

Greg Sams<br />

Tim Shinabarger<br />

Evan Vos<br />

Brandon Wynn<br />

INTERESTED? CALL OR EMAIL RYAN SILCOX:<br />

admin@backcountryhunters.org (406) 926-1908<br />

JEFF JONES: Alabama<br />

Environmental Engineer, U.S. Army Reserve Officer, BHA Life Member<br />

HOW DID YOU GET<br />

INTO HUNTING AND<br />

FISHING?<br />

I grew up hunting small<br />

game with my dad in south<br />

Mississippi. We focused on<br />

squirrels, rabbits, bluegills,<br />

catfish and doves.<br />

As a teenager, I became<br />

more interested in bass and<br />

whitetail deer. Now that I’m<br />

older, I find myself fly fishing<br />

for bluegill and hunting rabbits<br />

and squirrels again. It’s<br />

funny how it has come full<br />

circle.<br />

I have a 5-year-old daughter<br />

now, and I took her out for her<br />

first dove hunt this season. I<br />

was able to knock a few down<br />

and she was a great retriever.<br />

I also spent a week in Colorado<br />

chasing elk in the Hermosa<br />

Creek Wilderness. We<br />

had a great encounter with a<br />

large bull surrounded by cows,<br />

but just couldn’t get a shot.<br />

WHAT ATTRACTED<br />

YOU TO BHA?<br />

As I was researching an elk<br />

hunt, I kept coming across<br />

BHA online. I listened to Ty<br />

Stubblefield on the Gritty<br />

Bowmen podcast and it lit the<br />

fire.<br />

We are all looking for a<br />

tribe, and this is the tribe that<br />

I found. I identified with the<br />

BHA mission, the values, and<br />

it was something that lit that<br />

fire. I’m a public land hunter,<br />

and we have some great<br />

hunting opportunities here<br />

in Alabama: national forests,<br />

wilderness areas, national<br />

wildlife refuges and Tennessee<br />

Valley Authority land.<br />

If you are willing to get<br />

out there on the public land,<br />

you’ll have no shortage of<br />

opportunities to hunt. The<br />

mission of protecting and<br />

preserving this land really<br />

drew me to BHA.<br />

DOES THE BHA<br />

MESSAGE RESONATE<br />

IN ALABAMA?<br />

Absolutely, especially when<br />

you frame it as not only a<br />

Western thing.<br />

It matters to us for several<br />

reasons: we’re losing acres here<br />

in Alabama, with our budgets<br />

decreasing every year and<br />

decreasing license sales. The<br />

most important thing we can<br />

do is grow the sport. Without<br />

those license sales, we’ll lose<br />

the land and the management<br />

that was once there. The state<br />

can’t afford to do the browse<br />

management it once did. The<br />

Tennessee Valley Authority<br />

doesn’t even have a management<br />

plan.<br />

The state is looking for partners<br />

in the management of its<br />

land. I see us filling the gap<br />

with both volunteer activism<br />

and as a watchdog.<br />

Our wildlife management<br />

areas are not owned solely<br />

by the state, and we’ve lost<br />

something like 65,000 acres<br />

of WMAs in the last few years.<br />

The era of the big WMA in<br />

Alabama is gone.<br />

WHAT IS THE BIGGEST<br />

THREAT TO HUNTING?<br />

A low percentage of Americans<br />

identify as hunters. It<br />

would be very easy for the<br />

majority to boot us out of the<br />

picture completely.<br />

Presenting the picture of<br />

the true conservation-minded<br />

sportsman is important.<br />

When a bad hunting-related<br />

story goes viral on social media,<br />

it gives us a black eye.<br />

We need to spend more<br />

time talking about all the great<br />

things we are doing: funding<br />

the North American model<br />

of wildlife conservation, supporting<br />

communities. That<br />

directly feeds into our loss of<br />

public lands from congressional<br />

action.<br />

We need to spend more<br />

time telling our story rather<br />

than reacting to the narrative<br />

that’s being forced upon us.<br />

WINTER 2017 BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 9

OPINION<br />

Jess McGlothlin photo<br />

WHOA! Let’s Slow Down on Allowing Bikes in Wilderness<br />

BY JIM WATSON AND CAROL BIBLER<br />

THE EFFORT INVOLVED IN A SELF-GUIDED TRIP is daunting:<br />

planning meals, packing gear and food, trying to anticipate<br />

the weather, the horses’ and mules’ needs. July 2016 marked our<br />

fourth pack trip into the Bob Marshall Wilderness in three years,<br />

and our third unguided trip. Yet preparations were still not easy.<br />

“Why are we doing this?” Carol mused at one point. “Why do<br />

we love this so much?”<br />

“Because it forces us to slow down,” Jim replied.<br />

“Slowing down” is far more than recovering from the stress of<br />

trip planning or escaping life’s hectic routines. Slowing down allows<br />

us to enjoy silence, the songs of birds and the whisper of<br />

wind in the trees. It encourages us to look, listen and even smell.<br />

Slowing down enables us to transcend the cares of everyday existence,<br />

opens our minds to the natural world and invites us to<br />

become part of it.<br />

“I believe we have a profound fundamental need for areas of<br />

the earth where we stand without our mechanisms that make us<br />

immediate masters over our environment,” early wilderness advocate<br />

Bob Marshall wrote. So many mechanisms spring to mind<br />

when we read those words: cars, phones, computers, generators,<br />

chainsaws, bicycles...<br />

Recently, the focus has been on mountain bikes. It is exhilarating<br />

and challenging to ride over and around rocks, stumps and<br />

logs in the fresh mountain air. It’s a thrill to fly downhill. But it<br />

takes concentration to cover ground like that, a focus which is<br />

antithetical to the experience of slowing down.<br />

And certainly it’s antithetical to the Wilderness Act of 1964,<br />

which is fairly clear: “There shall be no ... use of motor vehicles,<br />

motorized equipment, motorboats ... no other form of mechanical<br />

transport ... within any such area.”<br />

The spirit of the act is even clearer. In the early 1930s, Bob<br />

Marshall said, “Areas ... should be set aside by an act of Congress.<br />

This would give them as close an approximation to permanence<br />

as could be realized in a world of shifting desires.”<br />

A world of shifting desires. Bob Marshall, who died in 1939,<br />

probably could not have imagined today’s full-suspension mountain<br />

bikes, wing suits, bungee cords or recreational drones. But he<br />

clearly knew such things would someday arrive. He knew mechanization<br />

would increasingly be at odds with true wilderness.<br />

Our friend Fritz, in his mid-70s, has traveled many thousands<br />

of miles on foot and horseback in and around the Bob Marshall<br />

Wilderness Complex, both for work and pleasure. This summer<br />

he and his wife completed an 11-day, self-guided trip across the<br />

Bob. Considering the idea of bikes in wilderness areas, he said:<br />

“Wilderness is a place where man and his progress is kept to a minimum.<br />

It’s a place where wheels do not belong except those that are<br />

turning in our heads as we appreciate the vistas without interruption;<br />

where we need not fear a wheeled vehicle careening around<br />

the corner running into us, the concern we have in crossing a busy<br />

downtown street. Wilderness is a place where time can slow down<br />

to its own pace, and we participate at that pace, not ours.”<br />

In the United States we are fortunate to have 193 million acres<br />

of national forests, including thousands of miles of roads and<br />

trails. Much of that bike-friendly land is breathtakingly beautiful.<br />

Opportunities abound for increased mountain bike access within<br />

these non-wilderness national forest lands.<br />

Less than 3 percent of national forest land is designated as wilderness.<br />

In a rapidly developing world, that 3 percent is an increasingly<br />

precious legacy for us and all who come after us. Now<br />

more than ever before, our species – not to mention those that are<br />

threatened or endangered – can benefit from places that humans<br />

haven’t conquered.<br />

That’s why we were dismayed to hear that Congress is considering<br />

a bill to allow the use of mountain bikes in designated wilderness<br />

areas. Mountain bikes are mechanical devices that enable<br />

humans to move much faster than otherwise would be possible,<br />

or appropriate, in formal wilderness.<br />

Luckily, there are hundreds of millions of acres outside wilderness<br />

areas where mountain biking is allowed and encouraged.<br />

Most folks, like the members of BHA, appreciate and enjoy<br />

mountain bikes – but in the appropriate places. This nuance is<br />

lost on politicians who have used this issue as a wedge between<br />

mountain bike enthusiasts and those who prefer traditional methods<br />

of transportation. Many mountain bikers and their organizations<br />

see this bill for the ruse it is and have come out against it.<br />

Wilderness areas provide a rare opportunity to step back in<br />

time and experience the world as it was before the mechanisms<br />

we humans created began to dominate existence. Aldo Leopold,<br />

another father of the wilderness movement, said, “Wilderness areas<br />

are first of all a series of sanctuaries for the primitive arts of<br />

wilderness travel, especially canoeing and packing.”<br />

When we have the opportunity to practice these arts in the<br />

absence of modern mechanisms whizzing by, we feel connected to<br />

our ancestors and the ways they experienced the world. Opportunities<br />

for those experiences are diminishing across the globe. It<br />

is little wonder then that more than 12 million people visit U.S.<br />

wilderness areas annually.<br />

The Wilderness Act of 1964 is not broken and does not need to<br />

be fixed. It has protected a relatively small but valuable sanctuary<br />

for those who wish to immerse themselves in truly wild places.<br />

Let’s slow down and look at the consequences before considering<br />

any changes to that visionary act.<br />

Jim and Carol ranch west of Kalispell, Montana. They have devoted<br />

much of the past 10 years to a volunteer-driven effort creating the<br />

34-mile Foy’s to Blacktail Trail System, on public and private lands<br />

in the Salish Mountains. The trail system welcomes cyclists, hikers and<br />

equestrians and is becoming a regional mountain biking destination.<br />

10 | BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL FALL 2016<br />

WINTER 2017 BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 11

KIDS’ CORNER<br />

donate.<br />

COLD AND HUNGRY<br />

Animal Adaptations for Winter Survival<br />

BY KEN KEFFER, PHOTOS BY PAUL QUENEAU<br />

FALLING SNOWFLAKES CAN MEAN ONLY ONE THING:<br />

It’s time to dig out the hats and gloves and have a snowball fight!<br />

But what about the wildlife outside in the cold? Check out the<br />

awesome ways animals survive frigid weather and deep snow.<br />

So Long, Cold Climate!<br />

Creatures that live in different places during summer and<br />

winter are called migrators. Whether traveling 40 miles down a<br />

mountain or 4,000 miles to South America, they’re relocating to<br />

avoid the cold and to find something to eat.<br />

The V-shaped flocks of flying Canada geese have always been<br />

icons of migration, but plenty of other waterfowl migrate, too.<br />

Teal, especially blue-winged teal, often move south at the first sign<br />

of chilly weather. In some years, a cold snap can push these small<br />

dabbling ducks south before the early teal hunting season opens.<br />

Don’t be surprised if you spot some ducks, geese and swans<br />

hanging out up north year-round. If they can find food, many<br />

species have no problem staying warm. The same down feathers<br />

that make your winter coat so cozy keep the birds weatherproof.<br />

Waterfowl also can keep their feet warm, even on a frozen pond.<br />

Big game such as deer, elk and pronghorn migrate across the<br />

landscape, too. Deep snows in the high country make it difficult<br />

to find food, so winter range is necessary for their survival. One of<br />

the longest of these annual mammal migrations takes mule deer<br />

over 150 miles in western Wyoming.<br />

WAYS TO GIVE:<br />

BECOME A LEGACY PARTNER<br />

PLANNED GIVING<br />

BEQUESTS<br />

COMBINED FEDERAL CAMPAIGN<br />

WORKPLACE MATCH<br />

CHARITABLE ANNUITIES<br />

IRA ROLLOVER<br />

photo credit: www.byland.co<br />

Sleep Tight<br />

Another way to avoid winter is<br />

to sleep through it. When animals<br />

are hibernating for the season, their<br />

metabolism slows way down. That<br />

means they need a lot less energy.<br />

They don’t eat or go to the bathroom<br />

at all, and their heart rate and<br />

breathing slows down to a couple of<br />

beats and breaths per minute. Many<br />

species of squirrels, mice, chipmunks<br />

and marmots are hibernators.<br />

Before hibernating, animals often<br />

build up fat reserves. Grizzly bears<br />

gain up to three pounds per day, for<br />

example. The most amazing thing<br />

is they don’t lose much muscle over<br />

winter. If your arm is in a cast for a<br />

few weeks it gets shriveled and weak,<br />

but bears stay strong all winter long.<br />

So, what about the black bears of<br />

the warm Southern states … do you<br />

think they hibernate? Nope! They<br />

stay active all year.<br />

Many reptiles and amphibians<br />

survive the cold by going into a hibernation-like<br />

phase. They bury<br />

themselves in the mud or under<br />

rocks or logs for months at a time.<br />

The wood frogs take this to the extreme<br />

by growing ice crystals inside<br />

their bodies! A high level of glucose,<br />

a form of sugar, in the frogs’ cells<br />

prevents them from turning into<br />

frogcicles.<br />

Winter Warriors<br />

The animals that don’t hibernate or migrate have to be<br />

well equipped for the challenges of winter. They must continue<br />

to find food and stay warm.<br />

Some creatures change coats for the winter as a disguise,<br />

and some do it to protect themselves from the cold. The<br />

ptarmigan, weasel and snowshoe hare all match the season<br />

by growing winter whites for camouflage. Most mammals<br />

that stay active all winter, from fox to caribou, grow coats<br />

that are thicker and much warmer.<br />

Just like people use oversized snowshoes to walk on top<br />

of the snow, animals like the lynx and hare have large feet.<br />

But not all animals live on top of the snow. Mice, shrews<br />

and weasels survive under it by making tunnels. The snow<br />

provides them a blanket of warmth and protection.<br />

Squirrels, beavers, jays and others will store food in the<br />

fall. The animals will have something to eat all winter as<br />

long as these supplies don’t run out before the spring thaw.<br />

Sometimes the effort spent finding food isn’t worth the<br />

nutrients. Moose will settle in and not eat for days to avoid<br />

plowing through the snow. When they do move, their long<br />

legs help them navigate deep snowdrifts. By placing their<br />

hindfeet into the front footsteps, they only have to break<br />

trail once. This helps them save energy.<br />

Winter can be a struggle for animals. Migration is a long<br />

and dangerous journey. Hibernating animals wake up hungry<br />

for their next meal. The animals that stick it out through<br />

winter don’t always make it until spring, either. The hearty<br />

critters that do survive the season are the true winter champions,<br />

and they do it all without boots or snowpants.<br />

Author and BHA member Ken Keffer grew up hunting and<br />

fishing in Wyoming. Now he is a naturalist who has written<br />

six books connecting families to nature. See more of his work at<br />

www.kenkeffer.net.<br />

GO TO BACKCOUNTRYHUNTERS.ORG OR CALL GRANT ALBAN AT 406-926-1908 TODAY!<br />

WINTER 2017 BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 13

POLICY<br />

STATES ATTEMPT TO SELL, TRANSFER LANDS<br />

BY BRIAN OHLEN<br />

SOME BHA MEMBERS ARE IN FOR A SURPRISE next<br />

hunting season when they arrive at a favorite hunting area to find<br />

a gate and private property sign blocking their way. State trust<br />

lands have recently been auctioned in Utah and Wisconsin, forever<br />

barring the American people from accessing these lands and<br />

waters. Wyoming resisted a large land transfer, largely because<br />

of the outcry generated by the Wyoming BHA Chapter. BHA<br />

members have led the charge in raising awareness of these issues<br />

by organizing rallies, creating online petitions and voicing their<br />

opinions to lawmakers. This collective voice can make the difference<br />

between preserving our hunting and fishing heritage and<br />

losing it forever.<br />

Utah:<br />

The Utah Trust Lands Administration held the second land<br />

auction of 2016 in October, selling off nearly 4,000 acres of state<br />

trust lands. The parcels provide excellent deer, elk and upland<br />

hunting. BHA member Ivan James used to hunt one of those<br />

sections.<br />

“On a recent hunt, after getting busted on a stalk and spooking<br />

nine deer off the section, I still had three more stalks that evening,”<br />

James said. “That parcel was up for sale and probably sold<br />

for more than I could ever afford.”<br />

That 640-acre parcel sold at auction for $850,000. This is the<br />

latest example in a long history of Utah’s state land auctions. Utah<br />

has sold more than half of the lands entrusted to it at statehood<br />

– 4.1 million acres now in private hands. This all happens while<br />

Utah considers pursuing a lawsuit against the federal government<br />

for control of U.S. Forest Service and BLM lands within the Beehive<br />

State’s borders. It’s not difficult to guess what would happen<br />

to those public lands if they are transferred, says Utah Chapter<br />

Board Member Joshua Lenart.<br />

Utah BHA members have risen in support of public lands and<br />

have brought attention to the state land sales by hosting the Full<br />

Draw Film Tour, Train to Hunt competition and chapter planning<br />

meetings to energize and inform sportsmen. The chapter<br />

created yard signs taking aim at the lawsuit, which have been a hit<br />

among members and businesses.<br />

“The yard signs were one way we’ve tried to raise public awareness<br />

and get the BHA name out there,” said Lenart. “One of the<br />

local fly shops gave us a significant donation. I’ve never met these<br />

folks, but they want to see sportsmen’s groups get on board with<br />

the public land issues.”<br />

Wisconsin:<br />

In 2012, the Wisconsin legislature passed a bill requiring the<br />

Department of Natural Resources to auction 10,000 acres of state<br />

lands. Since then two sales have taken place, selling more than<br />

7,000 acres. In October, the Natural Resources Board approved<br />

an additional 3,186 acres for sale, 1,344 of which provide public<br />

hunting and fishing opportunities.<br />

“One of the parcels that is recommended for sale has decent<br />

duck hunting,” said Wisconsin Chapter Board Member John<br />

Rennpferd. “Last time I drove by that land hunters were out<br />

there. They’re not going to have that next year.”<br />

Wisconsin BHA members have led the charge against these<br />

land sales. A petition on the BHA website has accumulated more<br />

than 2,000 signatures opposed to the auctions.<br />

“We started reaching out to the NRB with letters and showing<br />

our displeasure with land sales,” Rennpferd said. “The NRB took<br />

notice of the petition and referenced it in a recent meeting. It<br />

proves that we can focus attention on action issues.”<br />

“We can’t assume that other national organizations are going<br />

to stand up for what’s happening in Wisconsin,” Rennpferd said.<br />

“That’s why the state BHA chapter is so important.”<br />

Wyoming:<br />

Business owner Rick Bonander proposed to trade 295 acres of his<br />

property in the Black Hills for 1,040 acres of state land in the Laramie<br />

Range this fall. The transfer also would have isolated an additional<br />

3,000 acres of Forest Service and BLM lands, resulting in a net loss of<br />

more than 4,000 acres of public land presently open to the public. Wyoming<br />

BHA organized a successful campaign resulting in the rejection<br />

of the proposed swap by the Board of Land Commissioners.<br />

“Area 7 is one of the most popular elk areas in the state,” said Wyoming<br />

Chapter Board Member Jeff Muratore. “The land up for transfer<br />

is prime elk and deer country: broken mountains, pockets of trees, rugged<br />

and accessible by foot.”<br />

The 295 acres in the Black Hills offered no new access. It is traversed<br />

by a county road and provides only marginal hunting opportunities.<br />

Resistance to the exchange was substantial and BHA members played a<br />

pivotal role. The Wyoming Chapter brought this issue the attention it<br />

deserved through social media, petitions, and calls to the state land office.<br />

Most importantly, they showed up and testified at public hearings.<br />

“Most Americans will tell you they believe money controls politicians.<br />

I’ve covered these issues too long to disagree,” wrote Bob Marshall<br />

on Field & Stream’s Conservationist blog about this transfer. “But<br />

I’ve also talked to enough politicians and lobbyists on and off the record<br />

to know another truth: If an elected official gets enough response from<br />

constituents opposing what the money guys want, he/she will vote with<br />

the voters every time.”<br />

“BHA has been the leader in rallying the troops and opposing this<br />

land transaction,” Muratore said.<br />

14 | BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL WINTER 2017 WINTER 2016 BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 15

BACKCOUNTRY BISTRO<br />

Michael Furtman photo<br />

BY CHOL MCGLYNN<br />

FRIED SNOWSHOE HARE<br />

Backcountry Skiing with a Recurve Bow<br />

A RECENT VOLUNTARY WINTER<br />

road closure by the U.S. Forest Service to<br />

protect wintering elk populations here in<br />

northwest Colorado has indirectly led me<br />

to some of the best snowshoe hare honey<br />

holes I have ever encountered.<br />

I’m fortunate to live surrounded on<br />

three sides by the Routt National Forest<br />

outside Steamboat Springs. Even with the<br />

mountain known for its “champagne powder”<br />

nearby, I prefer to take my skiing in<br />

the backcountry. But with the closure of<br />

the Forest Service road out my back door,<br />

I’ve actually had to get in my car to earn<br />

those turns. That closure has forced me to<br />

other parts of the national forest and made<br />

my ski tracks cross many hare tracks. Naturally<br />

I’ve started bringing my bow skiing.<br />

Hare hunters typically employ beagles<br />

and shotguns and therefore are more successful<br />

than a lone traditional bowhunter. I<br />

take what I can get, but mostly I go home<br />

empty handed.<br />

I start my hunt by actually going out<br />

skiing for a couple hours after my 3-year<br />

-old son goes down for his afternoon nap.<br />

I get some touring in, carve some turns<br />

and head back toward the car with a stop<br />

along the way. I find some nice hare traffic<br />

areas, take off my sweaty base layer and replace<br />

with a dry layer, find a dark place to<br />

hole up and wait for movement. The other<br />

course of action is to try to spot the hares<br />

under their cover trees (if the snow is not<br />

too deep) and pick them off that way. The<br />

challenge is there and it’s often something<br />

else for dinner, but nothing beats an afternoon<br />

of skiing public land followed by an<br />

evening of hunting.<br />

Once I get home with my hare(s), the<br />

first thing I do after cleaning (and sometimes<br />

before I finish cleaning them) is cook<br />

and eat the heart, liver and kidneys. I fry<br />

them up in some butter or bacon fat sprinkled<br />

with a little sea salt. While I enjoy the<br />

tender little hearts and livers, the kidneys<br />

are my favorite! They taste like seared little<br />

gamey mushrooms. My wife is not much<br />

for the offal, so I usually enjoy these pieces<br />

on my own and I do not mind one bit.<br />

This recipe is a favorite for a snowy winter<br />

day’s lunch. The brine keeps the hare<br />

juicy and tender and helps if the hare is<br />

a larger, older one. If you prefer a lighter<br />

breading, simply coat the hare pieces once<br />

before frying. This makes for a lighter,<br />

more tender crispness. Use the double batter<br />

for real crunch. Dijon mustard is a classic<br />

with rabbit/hare in France and makes<br />

a fine dipper for the pieces. The pickles?<br />

Well, I just love pickles of all types!<br />

THE BEST FRIED HARE<br />

Ingredients:<br />

2 snowshoe hares<br />

Brine, cold (recipe to follow)<br />

Canola oil for frying<br />

2 cups buttermilk<br />

3 cups all-purpose flour<br />

½ cup garlic powder<br />

½ cup onion powder<br />

2 teaspoons paprika<br />

2 teaspoons cayenne<br />

2 teaspoons kosher salt<br />

½ teaspoon fresh ground black pepper<br />

2 sprigs thyme, chopped<br />

For the brine:<br />

2 lemons, halved<br />

4 bay leaves<br />

2 ounces flat leaf parsley<br />

4-5 springs of thyme<br />

2 ounces honey<br />

4 cloves garlic, peeled and smashed<br />

2 tablespoons black peppercorns<br />

2 ounces kosher salt<br />

3 quarts water<br />

¼ cup chopped parsley<br />

Procedures<br />

For brining the hare:<br />

1. In a large pot combine brine ingredients<br />

and bring to a boil. Boil for 1 minute<br />

until the salt is dissolved. Remove from<br />

the heat, cool, and then refrigerate until<br />

chilled.<br />

2. Place the hare in the brine for 8 hours.<br />

When ready to use, remove from brine and<br />

rinse under cold water.<br />

For frying the hare:<br />

1. In a large frying pan, heat the canola<br />

oil to 325 degrees F.<br />

2. Combine the dry ingredients and<br />

then split into two bowls. Add buttermilk<br />

to a third bowl.<br />

3. Dredge the hare pieces in the seasoned<br />

flour, then into the buttermilk, then<br />

into the next seasoned flour.<br />

4. Place the hare in hot oil for 2 minutes<br />

then begin moving the pieces around to<br />

fry evenly for a total of 8-10 minutes, until<br />

hare is golden and cooked thoroughly.<br />

5. Place hare on a platter, sprinkle with<br />

chopped thyme and serve with side of Dijon<br />

mustard and pickled vegetables.<br />

Chol is the executive chef at Vista Verde<br />

Ranch, a AAA rated 4 Diamond dude ranch<br />

north of Steamboat Springs, Colorado, as<br />

well as an avid fly fisherman and (primarily)<br />

bowhunter. He joined BHA in 2012 after<br />

reading about it in a David Petersen book<br />

and quickly became a Life Member, then<br />

Legacy Partner. Chol will be one of the chefs<br />

cooking for the Field to Table Dinner at the<br />

2017 Rendezvous in April. Learn more at<br />

backcountryhunters.org/rendezvous_2017.<br />

WINTER 2017 BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 17

Tim Romano photo<br />

ETIQUETTE<br />

DON’T JUST TAKE OUR WORD FOR IT...<br />

I just wanted to show my appreciatino for a fantastic product as well as great<br />

customer service. I have owned my Kenetrek Grizzly Pacs for 6 years now and<br />

I will never buy another brand of boot! Customer service was second to none<br />

this last year when I needed the boots to be resoled. Any mountain pounders<br />

out there who really hit hard in rough country need to make the permanent<br />

switch to Kenetrek. Thanks again guys!<br />

SAM STEPHENS, CODY, WY<br />

GRIZZLY<br />

PAC BOOTS<br />

When you’re trudging through knee deep snow<br />

on your way to late-season Elk camp, you’ll be<br />

happy you have your Kenetrek Grizzly Pac<br />

Boots. Built for hunting and hiking, utilizing<br />

thick steel shanks for support, and<br />

Thinsulate/wool felt liners, the Grizzlies will<br />

keep you upright and warm, no matter what<br />

Mother Nature throws at you.<br />

800-232-6064<br />

WWW.KENETREK.COM<br />

BY SARA EVANS-KIROL<br />

I PLAYED VOLLEYBALL for a small, four-year college. Each season<br />

would begin with a two-week camp, where we would spend<br />

nine hours a day in the gym in the middle of August honing our<br />

skills. My senior year, our coach decided we needed some team<br />

bonding and asked the other co-captain and me to lead a backcounty<br />

backpacking trip in the Absaroka Mountains.<br />

We geared up and headed out on a sunny morning. Oh, how<br />

wonderful to be outside the gym! We hiked for several hours to a<br />

pristine lake and made camp. With only a few hours of daylight<br />

left, we made dinner and hung out. A few of us took a stroll along<br />

the lake looking for fish and enjoying the orange glow fringing<br />

the rocky peaks.<br />

The next morning I was up early and walked down to the lake.<br />

I was disappointed to find a pile of someone’s garbage tucked in<br />

the grass and reeds along the shore. Sadly, I realized it belonged to<br />

one of my teammates. I called a meeting and asked for whoever<br />

left the items to pick them up. Later, after summiting a nearby<br />

peak I checked and it had been removed. From this incident, I<br />

learned that most people don’t have deliberate intentions to disturb<br />

natural lands; they simply don’t have the skills or education<br />

to prevent it.<br />

Our system of public lands is a point of pride for many Americans,<br />

and many of us take advantage of the opportunities these<br />

wild places provide. Tens of millions of us, in fact. As that visitation<br />

rapidly increased in the latter parts of the last century, land<br />

managers began noticing the ecological toll visitors were taking<br />

on public lands. They started implementing heavy-handed tactics<br />

such as area closures, stringent regulations and developed camp<br />

sites. But it quickly became evident that regulations alone would<br />

not solve the problem. So, land managers took to educational<br />

campaigns instead. You may remember a few: “Take Only Pictures,<br />

Leave Only Footprints,” “Give a Hoot, Don’t Pollute” and<br />

“Wilderness Manners.”<br />

Finally, in the 1990s, with support from management agencies,<br />

the outdoor industry, Boy Scouts of America and prominent outdoor<br />

leadership schools, the Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor<br />

Ethics was incorporated as a nonprofit organization. The mission<br />

of this organization is to sustain healthy natural lands for people<br />

now and in the future. It promotes this vision through several<br />

nation-wide education goals and strategies.<br />

The Leave No Trace principles provide people with a skill set<br />

that to helps to reduce or eliminate inadvertent impacts on the<br />

lands we all love and enjoy. These are outlined in a set of seven<br />

guiding rules for backcountry travel:<br />

LEAVE NO TRACE<br />

Plan Ahead and Prepare: Check with land management agencies<br />

for regulations, avalanche and weather reports. Tell someone<br />

your itinerary and stick with it, use a map and compass or GPS<br />

instead of rock cairns, flagging or marking paint. Unprepared<br />

people often resort to high-impact solutions.<br />

Travel and Camp on Durable Surfaces: Camp at least 200<br />

feet from water. Disperse use to prevent the creation of campsites<br />

and trails. Avoid places where impacts are just beginning. Choose<br />

deep snow to travel on whenever possible and in muddy spring<br />

conditions stay on snow or walk in the middle of the trail.<br />

Dispose of Waste Properly: Pack out everything you bring<br />

with you. Burying trash and litter in snow or the ground is unacceptable.<br />

Drag gut piles well away from trails, water sources and<br />

highly visited areas. Deposit solid human waste in cat holes 6-8<br />

inches deep and pack out toilet paper. Scatter strained dishwater<br />

and pack out all food scraps.<br />

Leave What You Find: Sight in firearms away from hunting<br />

areas. Do not use rocks, signs, trees or non-games animals for<br />

target practice. Leave historical and cultural artifacts intact and<br />

where you found them.<br />

Minimize Campfire Impacts: Stoves are often the best option<br />

as campfires can scar the backcountry. Trash or food does not belong<br />

in the fire pit and usually doesn’t burn completely. Use only<br />

sticks from the ground, don’t break branches off living or standing<br />

dead trees.<br />

Respect Wildlife: Never feed animals because it can damage<br />

their health and alter natural behaviors. Take only clean killing<br />

shots. Store your food and trash in a secure away not to attract<br />

animals. Winter is an especially vulnerable time for animals. Observe<br />

wildlife from a distance.<br />

Be Considerate of Other Visitors: Step to the downhill side<br />

when encountering pack animals, take breaks and camp away<br />

from trails and other visitors, and protect other visitor’s quality<br />

of experience by keeping noise levels down. Separate ski and<br />

snowshoe track where possible. Avoid hiking on ski or snowshoe<br />

tracks. Control dogs at all times.<br />

The gift of public lands comes with an obligation for each of<br />

us to care for what we have been given. Leave No Trace gives us<br />

the tools to shoulder our portion of responsibility in protecting<br />

natural areas, whether it’s the city park or federally designated<br />

wilderness. To learn more visit lnt.org or contact your LNT State<br />

Advocate.<br />

Sara was raised on her family’s cattle ranch in southern Wyoming.<br />

She worked as a river guide on the Colorado River prior to joining the<br />

Forest Service as a wilderness ranger, river ranger and trail crew boss.<br />

She is now the trails coordinator for the Bighorn National Forest.<br />

WINTER 2017 BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 19

BOOTS ON THE GROUND<br />

WHEN PRIVATE LANDS AREN’T<br />

BY RANDY KING<br />

ONE OF MY FATHER’S FAVORITE tales<br />

is about a buck he shot with a muzzleloader<br />

in the Owyhee Mountains of southwest<br />

Idaho. When the camp fire is rolling and<br />

the beer is going down, he tells of spooking<br />

a sleeping 4x4 while taking a pee and<br />

then shooting the buck at about 40 yards.<br />

“Then I look to my left and see a couple<br />

of orange hats. A husband and wife were<br />

watching me with my zipper down,” he<br />

says. “The biggest buck I ever shot with a<br />

muzzleloader was while I was taking a pee.<br />

Too bad that is all private ground now.”<br />

And that is how his story would end.<br />

Epic and hilarious conquest followed by<br />

regret that he could no longer hunt that<br />

spot. Since I was a child that section of<br />

land has been marked by orange paint<br />

along the fence and No Trespassing signs.<br />

Clearly it is private land. Right?<br />

Wrong. It turns out that most of the<br />

area is BLM or state of Idaho ground. So<br />

why is it marked private? Basically because<br />

Idaho has very generous trespassing laws.<br />

If land is unmarked and uncultivated, you<br />

can hunt on it. A landowner can ask a<br />

hunter to leave but can’t prosecute them<br />

for trespassing without having marked the<br />

land. To ease the burden on land owners,<br />

the state allows them to post their property<br />

using orange paint. Landowners can paint<br />

rocks, trees and, most commonly, fence<br />

posts to inform the public.<br />

Most hunters, being law abiding citizens,<br />

recognize the paint for what it means<br />

and do not enter. But some landowners<br />

have figured out that if they mark fence<br />

that is not theirs – a BLM fence in this<br />

case – that the under-funded federal land<br />

management agencies will never notice.<br />

Owyhee County has two BLM officers<br />

covering an area of 7,697 square miles.<br />

So, for 25 years, the area where my father<br />

shot his storied buck has incorrectly<br />

and illegally been marked as private. The<br />

landowner has effectively stolen access to<br />

public property from the community, taking<br />

advantage of hunters’ integrity.<br />

How did I find out? The onXmaps<br />

smartphone app. I recently attended a<br />

BHA meeting in Idaho. Apparently I had<br />

let my membership lapse, but if I renewed<br />

my membership right then I could get a<br />

year subscription to onXmaps. Two birds,<br />

one stone. So I sent in my check and got<br />

my subscription in the mail.<br />

As soon as I installed the app, I took a<br />

gander at some of my favorite hunting locations.<br />

Following a road up a long mountainside,<br />

I could see familiar sections of<br />

land. Lots of yellow BLM property, some<br />

blue state of Idaho property and plenty of<br />

non-colored private property. But when I<br />

took a closer look, at ridges that I knew<br />

well and at gates I frequently opened, I noticed<br />

something fishy. A gate I knew to be<br />

marked, locked and posted was clearly on<br />

state of Idaho land. And the area my dad<br />

always laments losing, due to a “posted”<br />

fence, was on BLM property! I was livid.<br />

The next day I called the BLM in Marsing,<br />

Idaho. I left a message over the phone.<br />

Then I emailed a screenshot of my onXmaps<br />

app and the illegally marked areas to<br />

them. Shortly after, Keith, a BLM employee,<br />

gave me call back.<br />

“A lot of my job this time of year is chasing<br />

these things down,” he said. “Everyone<br />

has those chips [for GPS] now and landowners<br />

are being kept honest with access.”<br />

My father met Keith up on the hill and<br />

showed him both illegally blocked access<br />

This gate was illegally locked and<br />

posted for decades, blocking the<br />

author and his family from their<br />

honey hole.<br />

points. “No question that these are illegal,”<br />

Keith said, taking a pair of wire cutters to<br />

the “No Trespassing” signs and cutting the<br />

lock off the gate. “I can’t actually do anything<br />

about the state land; it’s out of my<br />

jurisdiction. You’ll have to call Owyhee<br />

County for help with that.”<br />

I know the landowner’s name, I know<br />

he is important in the community and I<br />

know how small town politics work. I have<br />

not yet heard back from Owyhee County<br />

about the illegally marked gate on state<br />

land. I asked Keith about consequences for<br />

the landowner.<br />

“Not much right now,” he said. “Usually<br />

we just talk to them and they stop. If they<br />

keep it up the BLM can take away their<br />

lease. They really don’t want that.”<br />

I called Keith a few weeks later. I just<br />

wanted to thank him for his hard work. “I<br />

spoke with the landowner about the gate,”<br />

Keith told me. “And they said, ‘That has<br />

been marked for years, why are they having<br />

a problem with it now?’”<br />

The problem is theft. That land is my<br />

land and your land. Theft of public access<br />

is still theft – and our society has rules<br />

about that.<br />

My son and I went into the formerly<br />

posted area this fall. We had one of our<br />

best encounters ever, with a small herd<br />

of does at 4 yards, drinking from a pond.<br />

Our zippers were up, but we could see the<br />

deer blink, we could see the buttons on<br />

a yearling buck with our naked eye. We<br />

were making new memories, new stories,<br />

on our public lands.<br />

Randy is a husband, father of three boys,<br />

a BHA member and recently published his<br />

first book, Chef in the Wild: Recipes and<br />

Reflections of a True Wilderness Chef.<br />

20 | BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL FALL 2016<br />

WINTER 2017 BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 21

OPINION<br />

Sam Lungren photo<br />

WHITETAIL INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX<br />

BY BEN LONG<br />

AMERICA’S FOUNDING FATHERS HAD THIS FEAR of “the<br />

tyranny of the majority.” That is, if one larger group of people got<br />

too much power, it was bad for the whole democracy. That is why<br />

we have the Bill of Rights – to protect the rights of those who are<br />

outnumbered.<br />

Hunters should think of America’s public lands as a biological<br />

Bill of Rights. Those lands protect us from what I call the tyranny<br />

of the whitetail.<br />

First off, let me vow loyalty to King Whitetail. They are tasty,<br />

beautiful and fun to hunt. The bulk of my hunting time is spent<br />

pursuing whitetails, and they make up most of my protein intake.<br />

According to surveys by the National Shooting Sports Foundation,<br />

some 10 million American hunters pursue whitetail deer<br />

annually. By comparison, all other big game species account for<br />

only 300,000 hunters annually – a mere 3 percent. As a result,<br />

whitetail deer cast a mighty big shadow. They dominate the license<br />

fees (and thus agency priorities), the biological research, the<br />

trophy books, the outdoors media and the hearts and minds of<br />

American hunters.<br />

If whitetail deer did not exist, wildlife managers would probably<br />

genetically engineer a similar creature to thrive in modern<br />

America of industrial agriculture and urban sprawl. Whitetails<br />

need very little space – even a big buck can live its life contentedly<br />

on a single square mile. They breed rapidly to make up for<br />

heavy predation, whether it be by cougar, coyote, automobile or<br />

riflemen. They happily fatten on crops like soybeans or alfalfa.<br />

The ultimate generalists, they thrive in the deserts of Arizona, the<br />

frigid north woods of Canada, the swamps of Florida and city<br />

parks nationwide. If all wildlife were as flexible, we would need<br />

no Endangered Species Act.<br />

Whitetails are an all-American game animal. But they are not<br />

the only one. North America is blessed with more than 20 big<br />

game species, none of them as ubiquitous, but each as special.<br />

Look at it this way: Nothing against Bud Light, America’s most<br />

popular beer, but isn’t America richer for all our myriad of brews?<br />

Not all wildlife is as flexible as whitetail deer, living their lives<br />

in one square mile. Whitetails “fit between the cracks” of civilization,<br />

but many other popular big game species cannot. For<br />

example, some mule deer in Wyoming migrate 150 miles between<br />

summer and winter ranges. Pronghorn populations in Montana<br />

and southern Canada migrate 200 miles. A typical bull elk in the<br />

Rocky Mountains may use a home range of 15 square miles. A<br />

single grizzly bear requires 50 square miles. Bighorn sheep and<br />

mountain goats are habitat obligates – meaning they require a<br />

certain kind of rugged escape cover to survive.<br />

Big game needs big country. Whitetail deer are the exception<br />

that proves the rule.<br />

So where do these non-whitetail big game species live? In short,<br />

they live on public lands – the great national forests, grasslands,<br />

parks, and Bureau of Land Management acres of the American<br />

West (along with adjoining private timber and ranch lands). That<br />

public estate amounts to 640 million acres shared by people and<br />

wildlife alike. Because of the foresight of sportsmen and other<br />

conservationists over the past 100 years, this estate provides the<br />

foundation for North America’s wildlife heritage, even as the human<br />

population surpasses 310 million.<br />

Back in the 1990s, biologist Jack Ward Thomas noted that 80<br />

percent of America’s elk depend on public lands for at least part<br />

of their life cycle. The percentage is probably close to 100 percent<br />

for mountain goat, bighorn sheep, moose and other big game.<br />

In short, our national forests give wildlife the kind of space they<br />

need to thrive, even if they are not whitetail deer.<br />

“Public lands offer the broad expanses necessary for biodiversity<br />

and ecosystem function. You cannot parse up the land into<br />

smaller and smaller pieces and expect it to maintain the fabric<br />

of nature,” said biologist and wildlife advocate Shane Mahoney.<br />

“Having a nation anywhere in the world with millions of acres<br />

available to the citizens is an extraordinary gift and legacy.”<br />

Alarmingly, there are voices today who would liquidate that<br />

legacy. These people have the same anti-public lands philosophy<br />

that Theodore Roosevelt faced when he started to cobble together<br />

America’s network of public lands.<br />

I would also argue that public lands offer a certain authenticity<br />

of the hunt that is eroding rapidly in whitetail country. With the<br />

private-land, intensive wildlife management and food-plot practices<br />

of today, whitetail hunting is increasingly focused on manipulating<br />

the habitat and herds to produce shooting opportunities.<br />

While management can (and should) improve habitat on public<br />

lands, big game on public lands remain primarily as they have<br />

existed for the ages. On public lands, you shape your hunting to<br />

the ecosystem instead of shaping the ecosystem to the hunt.<br />

Thanks to TR and those like him, America’s wildlife heritage is<br />

whitetail deer plus much, much more. If we want to keep it that<br />

way, we’ll need to keep our public lands in public hands.<br />

Idaho outdoor writer Ron Spomer put it this way: “Public lands<br />

personify this idea we call America – which is freedom. The human<br />

animal – the human spirit – is not intended to be confined<br />

to a cage.”<br />

Ben is the vice chairman of BHA’s national board of directors. He<br />

ate whitetail for dinner last night.<br />

22 | BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL FALL 2016 WINTER 2017 BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 23

CHAPTER NEWS<br />

BHA CHAPTER<br />

LEADERS AFIELD<br />

b.<br />

c.<br />

d.<br />

e.<br />

f.<br />

a.<br />

g.<br />

k.<br />

l.<br />

m.<br />

h.<br />

i.<br />

j.<br />

n.<br />

o.<br />

p.<br />

q.<br />

r.<br />

s.<br />

t.<br />

u. v.<br />

w.<br />

a. British Columbia Chapter Chairman Bill Hanlon with his stone sheep b. Alaska Chapter Outreach Coordinator Steve Shannon fishing with his son, Seamus<br />