Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Autumn 2016<br />

A Publication based at St Antony’s College<br />

<strong>Identity</strong> & <strong>Culture</strong><br />

in the 21 st Century Gulf<br />

Featuring<br />

H.E. Salah bin Ghanem Al Ali<br />

Minister of <strong>Culture</strong> and Sports<br />

State of Qatar<br />

H.E. Shaikha Mai Al-Khalifa<br />

President<br />

Bahrain Authority for <strong>Culture</strong> & Antiquities<br />

Ali Al-Youha<br />

Secretary General<br />

Kuwait National Council for <strong>Culture</strong>,<br />

Arts and Letters<br />

Nada Al Hassan<br />

Chief of Arab States Unit<br />

UNESCO<br />

Foreword by<br />

Abdulaziz Saud Al-Babtain

OxGAPS | Oxford Gulf & Arabian Peninsula Studies Forum<br />

OxGAPS is a University of Oxford platform based at St Antony’s College promoting<br />

interdisciplinary research and dialogue on the pressing issues facing the region.<br />

Senior Member: Dr. Eugene Rogan<br />

Committee:<br />

Chairman & Managing Editor: Suliman Al-Atiqi<br />

Vice Chairman & Partnerships: Adel Hamaizia<br />

Editor: Jamie Etheridge<br />

Chief Copy Editor: Jack Hoover<br />

Arabic Content Lead: Lolwah Al-Khater<br />

Head of Outreach: Mohammed Al-Dubayan<br />

Communications Manager: Aisha Fakhroo<br />

Broadcasting & Archiving Officer: Oliver Ramsay Gray<br />

Research Assistant: Matthew Greene<br />

Copyright © 2016 OxGAPS Forum<br />

All rights reserved<br />

Autumn 2016<br />

Gulf Affairs is an independent, non-partisan journal organized by OxGAPS, with<br />

the aim of bridging the voices of scholars, practitioners, and policy-makers to further<br />

knowledge and dialogue on pressing issues, challenges and opportunities facing the six<br />

member states of the Gulf Cooperation Council.<br />

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily<br />

represent those of OxGAPS, St Antony’s College, or the University of Oxford.<br />

Contact Details:<br />

OxGAPS Forum<br />

62 Woodstock Road<br />

Oxford, OX2 6JF, UK<br />

Fax: +44 (0)1865 595770<br />

Email: info@oxgaps.org<br />

Web: www.oxgaps.org<br />

Design and Layout by B’s Graphic Communication.<br />

Email: abarboza@bsgraphic.com<br />

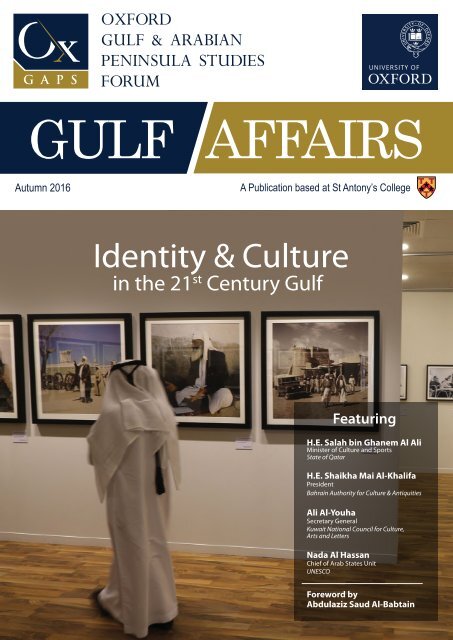

Cover: A visitor looks at photographs from Sheikh Hamdan bin Mohammed bin Rashid<br />

Al Maktoum’s, the Crown Prince of Dubai, personal collection at the Dubai Photo Exhibition<br />

on 19 March 2016.<br />

Photo Credits: Cover - Karim Sahib/AFP/Getty Images; 2 - Pool/Bandar Algaloud/<br />

Anadolu Agency/Getty Images; 6 - Xinhua/Alamy Stock Photo; 10 - Rabih Moghrabi/<br />

AFP/Getty Images; 13 - Nelson Garrido; 17 - Yasser Al-Zayyat/AFP/Getty Images; 22 -<br />

Marwan Naamani/AFP/Getty Images; 38 - REUTERS/Alamy Stock Photo; 42 - BACA;<br />

45 - NCCAL; 49 - UNESCO.

The Issue ‘<strong>Identity</strong> & <strong>Culture</strong> in the<br />

21 st Century Gulf’ was supported by:

Table of Contents<br />

Foreword<br />

Abdulaziz Saud Al-Babtain<br />

iv<br />

iv<br />

I. Overview<br />

<strong>Identity</strong> and <strong>Culture</strong> in the 21 st Century Gulf<br />

Magdalena Karolak, Theme Editor<br />

vi<br />

vi<br />

II. Analysis<br />

Khaleeji <strong>Identity</strong> in Contemporary Gulf Politics<br />

by Gaith Abdulla<br />

“Emiratization of <strong>Identity</strong>”: Conscription as a Cultural Tool of Nation-building<br />

by Eleonora Ardemagni<br />

Saruq Al-Hadid to Jebel Ali: Dubai’s Evolving Trading <strong>Culture</strong><br />

by Robert Mogielnicki<br />

IconiCity: Seeking <strong>Identity</strong> by Building Iconic Architectures in Kuwait<br />

by Roberto Fabbri<br />

The Banality of Protest? Twitter Campaigns in Qatar<br />

by Andrew Leber and Charlotte Lysa<br />

Monolithic Representations and Orientalist Credence in the UAE<br />

by Rana AlMutawa<br />

1<br />

2<br />

6<br />

10<br />

13<br />

17<br />

22<br />

III. Commentary<br />

27<br />

Challenges of Cultural <strong>Identity</strong> in the GCC<br />

by Ahmad Al-Dubayan<br />

The Gulf States’ National Museums<br />

by Sultan Al Qassemi<br />

The Local Evolution of Saudi Arabia’s Contemporary Art Scene<br />

by Alia Al-Senussi<br />

Understanding the Evolution of the Khaleeji <strong>Identity</strong><br />

by Lulwa Abdulla Al-Misned<br />

28<br />

30<br />

32<br />

34<br />

ii Gulf Affairs

Table of Contents<br />

IV. Interviews<br />

H.E. Salah bin Ghanem Al Ali<br />

Minister of <strong>Culture</strong> and Sports<br />

State of Qatar<br />

H.E. Shaikha Mai bint Mohammed Al-Khalifa<br />

President, Bahrain Authority for <strong>Culture</strong> & Antiquities<br />

Kingdom of Bahrain<br />

Ali Al-Youha<br />

Secretary General<br />

Kuwait National Council for <strong>Culture</strong>, Arts and Letters<br />

Nada Al Hassan<br />

Chief of Arab States Unit<br />

UNESCO<br />

37<br />

38<br />

42<br />

45<br />

49<br />

V. Featured Photo Essay and Timeline<br />

54<br />

Featured Photo Essay: Walls of the GCC<br />

by Rana Jarbou<br />

Timeline<br />

54<br />

56<br />

<strong>Identity</strong> & <strong>Culture</strong> in the 21st Century Gulf |Autumn 2016<br />

iii

Foreword<br />

Foreword<br />

by Abdulaziz Saud Al-Babtain<br />

In the 1960s, the Gulf states experienced a cultural renaissance<br />

and the start of intellectual modernization. Khaleeji society<br />

has evolved over the ensuing 50 years due to four key<br />

reasons. First is the progressive vision of civil society. This includes<br />

cultural foundations, institutions, clubs, and non-profit<br />

organizations as well as poets, sheikhs, thinkers, artists, and<br />

writers from the region. They all believe in culture and its value<br />

in evolving society’s virtues, principles, and wisdom. The<br />

second is communication. Across the region, daily editorials,<br />

columns, analyses, interviews, TV programs, radio programs<br />

and more recently, social media have all focused on cultural<br />

activities, and the cultural dimension of these societies has become<br />

a facet of daily life. It orients common opinion and adds<br />

understanding and value to our view of life.<br />

A third factor that has promoted cultural production and exchange<br />

across the GCC region is the development of printing<br />

and translation and the explosion of information available to a<br />

large segment of the population. Finally, governments of the Gulf states all play an important, central role<br />

in promoting local cultural production. Through the allocation of funds and encouragement of local societies,<br />

competitions, awards, and other efforts, public institutions have supported a well-entrenched tradition<br />

of indigenously-produced arts and culture. Today, the Arabic culture is much more universal than before<br />

because it has been disseminated internationally through cultural and civilizational centers for dialogue<br />

established in the big historical cities.<br />

My own efforts should be understood within the framework of civil society and corporate social responsibility.<br />

In 1989, I established the Abdulaziz Saud Al-Babtain Foundation, which now functions through<br />

six bodies: the Prize of Poetic Creativity, the Centre of Intercultural Dialogue, the Institute of Peace, the<br />

Centre of Communication, the Centre of Social Development, and the Directorate of Libraries.<br />

We organize and co-organize a number of cultural events with international institutions and finance others,<br />

forming a bridge between the Arab world and countries in Africa, Asia, and Europe. Recently, we were<br />

honored by re-endowing the Abdulaziz Saud Al-Babtain Laudian Chair in Arabic at the University of Oxford,<br />

which is one of seven other chairs ensuring the same mission in different universities in Chad, China,<br />

Comoros Islands, France, Italy, Spain, and Togo.<br />

After 25 years, the foundation is known all over the world, and we have organized 15 conferences and sessions<br />

in Arabic poetry and intercultural dialogue. We work closely with governmental institutions, international<br />

bodies, and NGOs, as the goals of the foundation resonate deeply with their missions. For example,<br />

in 2006, during the Foundation’s 10 th session held in Paris, France, under the auspices of His Excellency<br />

iv Gulf Affairs

Foreword<br />

the former French President Jacques Chirac and in coordination with UNESCO, we organized a seminar<br />

which was described by the former Director-General of UNESCO Koichiro Matsuura as an “excellent opportunity<br />

to reflect on the notion of intercultural dialogue, as well as on the role of the poet in encouraging<br />

mutual understanding and respect among cultures.” We are, Matsuura added, “encouraging creativity,<br />

and enabling it to flourish in a spirit of diversity and freedom. This is one of the best ways of promoting<br />

cultural vitality and sustaining human development.”<br />

Abdulaziz Saud Al-Babtain is a prominent Kuwaiti businessman and founder of the Abdulaziz Saud Al-Babtain<br />

Foundation. He is also a renowned poet and his first book Bauh Al-Bawadi (Intimations of the Desert) was published<br />

in 1995. Al-Babtain holds 14 honorary doctorates, has received numerous awards, honors, and medals<br />

including the Kuwait Order of the Sash from the Amir of Kuwait, Order of Civil Merit from the King of Spain<br />

and National Order of the Cedar from the President of Lebanon.<br />

<strong>Identity</strong> & <strong>Culture</strong> in the 21st Century Gulf |Autumn 2016<br />

v

I. Overview<br />

<strong>Identity</strong> and <strong>Culture</strong> in the 21 st Century Gulf<br />

Overview<br />

by Magdalena Karolak, Theme Editor<br />

The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries entered the 21 st century with greater maturity. Across the<br />

region, these states consolidated the many political, economic, and social projects that had been in progress<br />

since independence and state formation in the 20 th century.<br />

New challenges abound, however, as Gulf millennials enter a rapidly changing world facing regional conflicts<br />

and socioeconomic pressures. One of the core questions likely to shape the coming decades in the Gulf<br />

is the issue of identity. States must continue to forge strong national identities, while the creation of the<br />

GCC has paved the way for the growth of a pan-khaleeji identity. Formation of national identities in the<br />

Gulf has not been an easy project, as exemplified elsewhere in the Middle East. Religious, ethnic, tribal,<br />

and settlement cleavages that cut through the population are factors that make identification and loyalty<br />

with non-state structures more salient. The structures of power often determine these specific patterns of<br />

identification. Yet, it is also clear that identities, once crystallized, in turn impact the social structure.<br />

The creation of strong national identities requires anchoring the nation’s history in founding myths shared<br />

by all citizens. Indeed, a community exists thanks to a shared perception of the past, present, and future<br />

events that transcends individuals, linking their lives to those of their predecessors and their successors in<br />

a meaningful way. Attempts to revive and, most importantly, reconstruct history based on present needs,<br />

are widely observed in the Gulf. New museums, monuments, archaeological sites, and the revival of tradition<br />

all testify to this need. In the process, new meanings and national narratives are formed.<br />

However, in search of uniformity and consolidation, what is inscribed in the collective memory often omits<br />

minority identities that do not easily fit the mainstream. Such strong national identities have been actively<br />

sought as the GCC attempts to move away from the rentier model and new generations of citizens are<br />

asked to contribute to their countries in various ways. Gulf newspapers often celebrate the talents and<br />

achievements of young citizens in various disciplines, while Saudi Arabia recently called on its citizens to<br />

sacrifice for their country with salary cuts in public jobs. Other types of sacrifice may be even more palpable<br />

as GCC countries intervene militarily in conflicts at home and abroad. Sacrifice for the country is, in turn,<br />

cherished through public celebrations of citizens’ commitments and achievements, further strengthening<br />

national narratives.<br />

The needs of the present also dictate another trend that shapes the Gulf, that of construction. Lacking<br />

monuments that could rival others in the Middle East, the GCC countries have embarked on extravagant<br />

building programs that put Gulf cities on the map among the most impressive architectural undertakings.<br />

With the tallest building in the world in Dubai (soon to be overshadowed by Jeddah Tower), and many other<br />

daring constructions and developments on the way, the Gulf cities have been transformed from somewhat<br />

sleepy trading towns to world centers, places to see and to be seen. The glamour that is a by-product<br />

of modernity does not undermine the fact that the Gulf strives to continue the legacy of Middle Eastern<br />

achievements. Many iconic buildings in the GCC stand out juxtaposed with the Egyptian pyramids in the<br />

Priceless Arabia MasterCard advertisement for the MENA region, for example. So far, facilitated by oil re-<br />

vi Gulf Affairs

I. Overview<br />

sources, the Gulf further sets itself as a center of world banking, tourism, trade, shopping, and innovation,<br />

projecting its identity toward the future with a sense of pride.<br />

Indeed, in a Middle East torn by conflicts and upheavals, the Gulf seems to hold a special place characterized<br />

by stability and progress. This search for stability was the reason for the creation of the GCC in the<br />

first place and makes “othering” from neighboring states easier. Yet, the khaleeji identity tied to the GCC<br />

project is characterized by fluidity, with cooperation at times closer or further away. However, the need<br />

for security and preservation of the Gulf’s political systems may dictate closer ties in the future. It is not a<br />

coincidence that the proposal of a Gulf union followed the GCC intervention in Bahrain. With the rising<br />

rivalry between Saudi Arabia and Iran over dominance in the Middle East, the GCC project, and hence<br />

khaleeji identity building, remains as valid as ever.<br />

Lastly, it is clear that individuals need to self-identify with specific communities, practices, and institutions<br />

with which they form attachments. The study “Psychological Effects of Globalisation on Young Women<br />

and Men” conducted by the Dubai School of Government concluded that bilingual students in the UAE<br />

and Saudi Arabia are bicultural, as they identify with both local and global cultures. The GCC has some<br />

of the highest per-capita rates of internet use in the world and offers a particularly interesting case study.<br />

While at this point the internet has not eradicated local cultures, appropriation of cultural elements from<br />

elsewhere will have important effects in the future. This may raise interest in institutionalizing the protection<br />

of local cultures, taking into account the large presence of expatriates. In addition, networking<br />

opportunities offered by the internet have already proved important in the creation of collective identities<br />

on national and regional levels. The shift towards responsible and active citizenship will no doubt create<br />

more grassroots activism facilitated by the use of internet. Collective activism may ultimately be based on<br />

identities of groups that feel left out of the mainstream, bringing us back to the question of strong national<br />

identities.<br />

This volume is a fine selection of analyses highlighting the many debates and multi-dimensional developments<br />

that are taking place. These extremely interesting intersections invite us to closely follow the subject<br />

of Gulf identities, no doubt leaving us with more questions than answers, which makes the reading even<br />

more rewarding.<br />

Dr. Magdalena Karolak is Assistant Professor of Interdisciplinary Studies at Zayed University, UAE. She<br />

has published more than 30 journal articles and book chapters on various aspects of social, political and<br />

economic transformations in the GCC.<br />

<strong>Identity</strong> & <strong>Culture</strong> in the 21st Century Gulf |Autumn 2016<br />

vii

II. Analysis

II. Analysis<br />

Saudi Arabia’s Defense Minister and Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman chairs the meeting of defense ministers of the GCC<br />

states in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia on 15 November 2016.<br />

Khaleeji <strong>Identity</strong> in Contemporary<br />

Gulf Politics<br />

by Gaith Abdulla<br />

haleeji identity has great potential to explain the contemporary politics and international relations of<br />

the Gulf. However, it is by no means a widely recognized concept; you’d be hard pressed to find even<br />

passing reference to the term in the literature on Gulf politics. 1 Khaleeji (meaning ‘of the Gulf’ in Arabic)<br />

denotes a socio-political regional identity that is shared by citizens of the six Gulf Cooperation Council<br />

(GCC) states. Khaleeji identity is the next step in the evolution of political identity in the Gulf, which began<br />

with tribal identities and developed to include national identities with the advent of nation-states in the<br />

region in the mid-20 th Century.<br />

Khaleeji identity builds on strong cultural homogeneity within the Gulf states, the result of a long history<br />

of sustained social engagement and intermarriage. It also features prominently in popular culture, music,<br />

television, sports, civil society, and reaches all the way to the top decision-making levels of government.<br />

In the regional milieu, khaleeji identity has had a defining role in the creation and durability of the GCC,<br />

what is today the most stable and highly functional regional institution in the Middle East. 2 Although fear<br />

of an expansionist post-revolution Iran was one of the primary motivations behind the establishment of<br />

this regional architecture, 3 the underlying khaleeji identity common to the Gulf states was the social glue<br />

that allowed such regionalization to take place. What’s interesting about the GCC is that since its creation<br />

2<br />

Gulf Affairs

II. Analysis<br />

in 1981 it has become a key driver of khaleeji identity. The GCC is the most tangible manifestation of the<br />

regional identity and this international institution has “contributed decisively to the creation of a khaleeji<br />

persona in international relations.” 4<br />

Khaleeji – in theory<br />

Despite its significance and potential, khaleeji identity has remained an under-theorized term. This is primarily<br />

the result of the overriding influence of oil on the conceptualization of the politics of the Gulf. Many<br />

of the existing theories of the socio-political structures of the Gulf have developed with oil as a central unit<br />

of analysis. As these conceptions reflect the strategic, political, and economic security concerns of great<br />

powers (namely the US) in the region, it is only natural that oil has had such a defining role in shaping the<br />

theories and perceptions of Gulf politics. 5<br />

Because elite and ruling social classes in the Gulf are the most relevant to oil production and policy, they<br />

are the most notable classes to account for in the oil-centric theories. And these theories, which are mostly<br />

concerned with security and oil output from a great power perspective, content themselves by discussing<br />

the internal dynamics of Gulf states as a relationship of the elite/ruling classes with the rest of ‘society’<br />

measured in terms of material resources. 6 The inflated influence of oil, great power strategic interests, and<br />

the elite/ruling classes on existing theories points to the importance of developing concepts such as khaleeji<br />

identity that open avenues to constructivist approaches to the politics of the Gulf as opposed to the hawkeyed<br />

realist conceptualizations.<br />

<strong>Identity</strong> and the interests of the state<br />

Realism plays a big role in the behavior of khaleeji states given the region’s strategic significance. But<br />

among other nebulous state-society relationships, institutional policy production is often mired in self-interests.<br />

Hence taking a step back and re-theorizing could possibly yield a better understanding of policy<br />

production and state behavior in the Gulf. On the other hand, with a sight set beyond material interests<br />

and security concerns, constructivism recognizes that states are social actors, seeing identity and other<br />

“ideational forces” as important motivators “on political interests and thus on national security policies.” 7<br />

From a constructivist perspective, khaleeji identity forms a vital component of Gulf politics and would<br />

be a cornerstone in any project of regional integration in the Gulf. Constructivism defines regionalism<br />

as a product of “regional awareness, a shared sense of belonging to a particular regional community. . .<br />

Therefore, sub-regional integration is dependent on the compatibility of major values relevant to political<br />

decision-making.” 8<br />

The potential of a shared regional identity, like khaleeji identity, for policy production and grass-roots regionalization<br />

is evident. However, bygone failed integration projects based on the perception of a shared<br />

identity (e.g. Arabism) call for caution. The issues that plague Arabism are for the most part the same problems<br />

faced in the Gulf, that the project of integration exists at the level of states, is informed by the ruling/<br />

elite classes, and lacks functioning democratic avenues. These factors hinder the effective representation<br />

of the social dimension. 9<br />

However, the homogeneity of the socio-political climate in the Gulf states is something that did not feature<br />

in the Arab integration project. This is where khaleeji identity comes to play: it represents not only<br />

common popular culture, history, traditions and heritage, but also complements the existent prevailing<br />

<strong>Identity</strong> & <strong>Culture</strong> in the 21st Century Gulf |Autumn 2016<br />

3

II. Analysis<br />

Khaleeji identity forms a vital component of Gulf politics<br />

and would be a cornerstone in any project of regional<br />

integration in the Gulf.<br />

elite classes.<br />

socio-political identities, namely Arab, Islamic,<br />

tribal and national identities. This<br />

regional identity represents a shared political<br />

culture amongst citizens and not<br />

only common ideals limited to the ruling/<br />

The Middle East today is probably in the worst shape in its modern history. Amidst this, the Gulf states<br />

contrast starkly with their surroundings. Although by no means unscathed by the turmoil, the six members<br />

of the GCC find themselves as the most stable and coherently functional states in the region. As the<br />

rest of the Arab world has ground to a halt, Gulf cities are argued to be the new centers of the region. They<br />

are now the “nerve center of the contemporary Arab world’s culture, commerce, design, architecture, art<br />

and academia.” 10 The Gulf states need to reflect on their particularities, strengths, and weaknesses as they<br />

find themselves occupying positions of power and influence in the Middle East that they are unaccustomed<br />

to. Khaleeji identity is an invaluable particularity to the Gulf states, both shaping and being shaped by actions<br />

and policies. It acts as a dynamic force strengthening intra-GCC relations at the elite and grass roots<br />

levels and informs more coherent and consistent regional interaction.<br />

The relationship between identity, the state, and society has become more complex and pronounced than<br />

ever in the history of the Gulf. The roles, actions, and attitudes of the Gulf states are changing, and with<br />

that the role of identity becomes ever more salient. It is necessary to appreciate the role that khaleeji identity<br />

plays in the social milieu as a fundamental driver of domestic attitudes and regional and international<br />

policy positions, as doing so will create more strategic, sustainable, and perhaps democratic policies. Indeed,<br />

khaleeji identity will remain highly dynamic as it defines the societies and states of the Arab Gulf in<br />

the 21 st Century.<br />

Gaith Abdulla is a doctoral candidate at Durham University focusing on khaleeji identity, youth and regionalisation<br />

in the Gulf.<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5<br />

A notable exception is Adam Hanieh’s conceptualization of khaleeji capital in his book Capitalism and Class in the Gulf Arab States<br />

(Palgrave Macmillan: London, 2011). In defining khaleeji capital he explains “The Arabic word khaleej is literally translated as “Gulf” but<br />

goes beyond a geographic meaning to convey a common pan-Gulf Arab identity that sets the people of the region apart from the rest of the<br />

Middle East.” (p.2).<br />

Abdullah Al Shayji, “Salman doctrine is the best option,” Gulf News, April 3, 2016.<br />

Kristian Ulrichsen, Insecure Gulf: The End of Certainty and the Transition to the Post-Oil Era (London: Hurst, 2011).<br />

Matteo Legrenzi, The GCC and the International Relations of the Gulf: Diplomacy, Security and Economic Coordination in a Changing<br />

Middle East (London: I.B. Tauris, 2011), p.153. In his book, Legrenzi argues that the GCC has been responsible for a Gulf popular identity<br />

becoming a substantive reality and “working its way into the political and economic landscape of the six Gulf monarchies.” (p.2)<br />

Current Gulf politics are clearly shaped by U.S. policy and oil security. For example, the U.S. ‘pivot to Asia’ is seen as one of the main<br />

driving forces behind Saudi Arabia’s newfound assertiveness and hard power projection in the region, the Saudi-led military campaign in<br />

Yemen being the prime example of this. And the perception is that current record low oil prices have motivated the governments of the<br />

Gulf states to seek to expedite processes of economic diversification and escape the dependency on oil. See Roberts, David, “Shake up for<br />

the sheikhs as the oil slump hits home,” Chatham House, June/July 2016.<br />

4 Gulf Affairs

II. Analysis<br />

6<br />

7<br />

8<br />

9<br />

10<br />

Commonly referred to as the ‘ruling bargain’, in which the elite/ruling classes use their oil money to subsidize their societies in return<br />

for political acquiescence. See Davidson, Christopher, “Diversification in Abu Dhabi and Dubai: The Impact on National <strong>Identity</strong> and<br />

the Ruling Bargain,” in Popular <strong>Culture</strong> and Political <strong>Identity</strong> in the Arab Gulf States, Alsharekh, A.&R (Springborg London: Saqi<br />

Books, 2008), 143-153.<br />

Legrenzi, 46.<br />

Ibid, 46-47.<br />

Although Arabism and Arab integration was a populist ideal and had huge popular support in its heyday, the lack of functioning<br />

democratic apparatus meant this popular dimension was never able to manifest itself in policy production. The contagion effect of the<br />

Arab Spring is a great example of these deeply ingrained shared attitudes amongst Arabs. See Lynch, Marc. “The Big Think Behind<br />

the Arab Spring.” Foreign Policy. November 28, 2011.<br />

Sultan Al-Qassemi, “Thriving Gulf Cities Emerge as New Centers of Arab World,” Al-Monitor, October 8, 2013.<br />

<strong>Identity</strong> & <strong>Culture</strong> in the 21st Century Gulf |Autumn 2016 5

II. Analysis<br />

A service man talks with a child during a military show to celebrate the 43 rd anniversary of the founding of the UAE in Abu Dhabi on 1<br />

December 2014.<br />

“Emiratization of <strong>Identity</strong>”: Conscription as a<br />

Cultural Tool of Nation-building<br />

by Eleonora Ardemagni<br />

n 2014, the United Arab Emirates introduced compulsory military service for nationals. However,<br />

this new requirement will not change the fundamental factors shaping the UAE’s security reality.<br />

First, Emiratis comprise a tiny percentage of the country’s total population, representing only 20 percent<br />

of the UAE’s total inhabitants. Secondly, persistent coup-proofing strategies remain fundamental to preserving<br />

regime stability. The Emiratis maintain a small army that is directly controlled by Abu Dhabi’s<br />

royal family and contains a mix of ‘asabiyya-based officers and foreign manpower. In addition to a strict<br />

military rationale, the government’s plan for conscription has a deep cultural intent: the “Emiratization<br />

of identity.” Emiratization is “a policy of national unity”, 1 and with the introduction of the military draft,<br />

the government aims to enhance the collective national Emirati identity, which remains fragmented by<br />

different tribal affiliations, emirate-specific identities, social classes, and the overwhelming numbers of<br />

expatriates in the country. In recently-unified states, conscription has often helped central institutions to<br />

build a national political discourse. 2 National identity, as a dynamic set of shared beliefs and historical<br />

legacies, is a theoretical concept, but at the same time it is an incessant social construction. 3 Looking at<br />

post-colonial state-building in Arab republics, compulsory military service was a driver of nationalism and<br />

enhanced regime security. In a time of multidimensional challenges, the UAE’s conscription and military<br />

engagement abroad may be seen as practical devices to forge a recognizable group identity and a modern<br />

6 Gulf Affairs

II. Analysis<br />

and effective national discourse.<br />

From a federation towards a nation<br />

The UAE federation-building process has succeeded through top-down policies, even if<br />

state-centralization is still ongoing. In the 1970s, the UAE’s state-building process was primarily<br />

rent-driven, but armed forces became late federation-building drivers from the 1990s<br />

onwards. 4 In 1997, Dubai integrated its military system into a federal one. The modern integration<br />

into a single force allowed Abu Dhabi to include members from the northern emirates,<br />

which was important because at least 61 percent of Emirati nationals live in the north. 5 However,<br />

this did little to expand national identity, as the step was primarily used to expand Abu<br />

Dhabi’s neo-patrimonial leadership over the whole federation. Today, nation-building is still a<br />

“work in progress.”<br />

This work in progress is geared towards nurturing<br />

a national mythomoteur built on perceived<br />

myths, memories, and symbols. For example, the<br />

Bedouin mythology is a fundamental heritage, although<br />

it is sometimes stereotyped. 6 But it alone<br />

has not been successful in conveying a sense of belonging among contemporary young Emiratis.<br />

The politics of militarization has gradually differentiated the UAE from its neighbors. Emirati<br />

foreign policy is currently driven from a geopolitical and security viewpoint. As a matter of fact,<br />

the security sector has recently become a pillar of the UAE’s institution-building. The UAE’s<br />

military engagement in Yemen represents an unprecedented effort in terms of regional security,<br />

and economic diversification projects target the defense sector more and more, as confirmed<br />

by the development of Abu Dhabi’s military industrial complex.<br />

Conscription and geopolitics<br />

The Emirati government’s decision<br />

to introduce conscription as a tool<br />

of nation-building has to be framed<br />

in a specific geopolitical context.<br />

In the UAE, compulsory military service involves male citizens between the ages of 18 and 30.<br />

The service is optional for women, who can serve for nine months with the consent of their parents.<br />

Federal Law 6/2014 has extended national service from nine to 12 months for high school<br />

graduates, while it remains two years for nationals with lower levels of education. The 2015-<br />

2017 Emirati Strategy for the National Service establishes three batches each year of between<br />

5,000 and 7,000 total recruits. The first phase of national service is about study, exercises, and<br />

lectures on patriotism. 7 Recruits then join the Presidential Guard for practical training.<br />

The Emirati government’s decision to introduce conscription as a tool of nation-building has to<br />

be framed in a specific geopolitical context. Currently, the Middle East is marked by several<br />

intertwined variables of insecurity which have a direct impact on national identity. First of all,<br />

the Arab uprisings have introduced into the Emirati public debate ideas such as active citizen<br />

participation in the decision-making process and government accountability.<br />

Secondly, the phenomenon of jihadi transnational networks, such as the self-proclaimed Islamic<br />

State, challenges Arab states, suggesting the physical presence of the imagined umma.<br />

The objective of these non-state actors is to erode the political legitimacy of traditional states,<br />

labeling them “un-Islamic” and contesting established boundaries. Such challenges press state<br />

<strong>Identity</strong> & <strong>Culture</strong> in the 21st Century Gulf |Autumn 2016 7

II. Analysis<br />

institutions to implement intricate counter-narratives. In the UAE’s case, military service symbolizes<br />

the rhetoric of a nation that citizens want to proudly defend.<br />

Thirdly, the political rivalry between Saudi Arabia and Iran for regional hegemony, where<br />

sectarianism is a tool of power politics, exacerbates national spirits, prompting states to choose<br />

alliances and produce counter-alignments. With regard to the Yemeni conflict, the UAE aligned<br />

with Saudi Arabia from the beginning despite considerable economic interests with Iran, the<br />

presence of a remarkable Iranian diaspora within the federation, and Dubai’s traditional commercial<br />

and cultural relations with Tehran. The mission, which serves geopolitics and nation<br />

building, took precedence over other important interests.<br />

The Yemeni laboratory: militaries as identity-mobilizers<br />

The UAE’s military intervention in Yemen has bolstered a sense of national identity among<br />

Emirati citizens. The federation has been operating in Yemen since March 2015, participating<br />

first in airstrikes against Shia militias, then heading de facto ground operations in the southern<br />

regions, with a specific focus on counterterrorism (anti-AQAP operations) within Aden,<br />

Mukalla and the Abyan region. In the summer of 2015, Abu Dhabi’s Presidential Guard and<br />

some drafted soldiers were deployed to Yemen, and more than eighty Emirati soldiers have lost<br />

their lives in Yemen so far. On September 4, 2015, forty-five Emirati soldiers were killed by a<br />

Houthi attack near Mareb, an unprecedented number of single-day military casualties for the<br />

federation.<br />

Since the beginning, UAE official declarations and media coverage framed the unexpected event<br />

through a patriotic lens: the ‘collective mourning’ was immediately juxtaposed with references<br />

to the ‘epic of sacrifice’ and the ‘celebration of the Nation,’ evoking the “soldiers martyred<br />

in Yemen.” 8 To commemorate what happened in Mareb, a day of National Celebration was<br />

established on November 30. The day also emphasizes the novel nature of the UAE’s military<br />

commitment abroad, which transcends traditional internal security tasks and marks a “paradigm<br />

shift” for Gulf military forces. 9 The ‘heroic militaries’ have enhanced a ‘rally around the<br />

flag’ feeling. They might become identity-mobilizers, the government’s best example of Emirati<br />

identity. By analyzing the recent Federal National Council’s elections, we see that military<br />

prestige has started to play a mobilizing role in the electoral competition—of 341 candidates, 46<br />

came from a police or military career, 10 as well as five out of the 20 who were eventually elected.<br />

One of those elected, former Dubai chief of the police Matar bin Amira Al-Shamsi, campaigned<br />

with the slogan “military service and patriotism.” 11 Soldier Khalifa Al-Hamoodi from Fujairah,<br />

injured in Yemen, received extensive media coverage while he was at the electoral poll to cast<br />

his ballot. 12 The government hopes that Emiratis will develop communal bonds and an in-group<br />

awareness by looking at their soldiers, a mindset that would modernize and bolster the Emirati<br />

mythomoteur. Moreover, the “mediatization” of the militaries sheds light on their new social<br />

role, which also includes a counter-radicalization message against the phenomenon of foreign<br />

fighters. From this perspective, the shahid is the heroic soldier or pilot who sacrifices himself to<br />

protect the nation, not the suicide bomber who kills “the infidels.”<br />

Conclusion<br />

It is possible to identify a circular relationship between the UAE’s armed forces and the domes-<br />

8 Gulf Affairs

II. Analysis<br />

tic realm. Militaries contribute to a sense of federal belonging and national consciousness. At<br />

the same time, the country’s institutions are attempting to maximize this bottom-up popular<br />

phenomenon, introducing top-down measures, such as military conscription, aimed to shape a<br />

shared collective identity and cope with rising internal security threats. Through military service,<br />

the federal government aims to promote nationalism above Islamism, the Muslim Brotherhood,<br />

and jihadism.<br />

For the UAE, yesterday’s challenge was passing from ‘many tribes’ to a ‘unified federation.’<br />

Nowadays, the aspiration is instead to construct ‘the Nation,’ where identity generates social<br />

cohesion and nurtures state legitimacy. 13 The geopolitical context is highly unstable, and the<br />

UAE has also been confronting the domestic effects of globalization—among them expatriate<br />

communities which claim for naturalization—raising fear of identity dilution and, to a lesser<br />

extent, cultural assimilation. Bedouin ancestry and khaleeji culture are essential pillars of the<br />

UAE’s national identity. Nevertheless, the national mythomoteur seeks new symbols, beliefs,<br />

and shared myths to face post-modernity, especially now that the Arab Gulf region is marked<br />

by growing and sometimes competing nationalisms. Therefore, in line with the government’s<br />

aspirations, conscription is not only a military institution, but rather a cultural tool of nation-building<br />

and the Emiratization of identity.<br />

Eleonora Ardemagni is a Gulf Analyst at the NATO Defense College Foundation and a regular<br />

contributor for the Aspen Institute Italy and the Italian Institute for International Political Studies<br />

(ISPI, Milan).<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5<br />

6<br />

7<br />

8<br />

9<br />

10<br />

11<br />

12<br />

13<br />

Karen E. Young, The Political Economy of Energy, Finance and Security in the United Arab Emirates: Between the Majilis and the Market<br />

(Palgrave Macmillan: 2014), p. 33.<br />

See for instance the case of Italy. Vanda Wilcox, “Encountering Italy: Military Service and National <strong>Identity</strong> during the First World<br />

War”, Bulletin of Italian Politics, Vol.3, No.2, 2011, 283-302.<br />

Benedict Anderson, Imagined communities: reflections on the origins and spread of nationalism (London: Verso, 1991).<br />

Eleonora Ardemagni, “United Arab Emirates’ Armed Forces in the Federation-Building Process: Seeking for Ambitious Engagement,”<br />

International Studies Journal 47, vol.12, no.3, Winter 2016, pp.43-62.<br />

Victor Gervais, “Du pétrole à l’armée: les stratégies de construction de l’état aux Émirats Arabes Unis,” Institut de Recherche Stratégique<br />

de l’Ecole Militaire (IRSEM), Études de l’IRSEM 8, 2011.<br />

Ronald Hawker, “Imagining a Bedouin Past: Stereotypes and Cultural Representation in the Contemporary United Arab Emirates,”<br />

Beirut Institute for Media Arts conference paper, Lebanese American University, 2013.<br />

Samir Salama, “National service will reinforce patriotism, national identity, says FNC Speaker,” Gulf News, 16 June, 2014.<br />

“UAE salutes 45 soldiers martyred in Yemen,” Khaleej Times, 5 September, 2015; The National, “UAE news in review 2015: A year of<br />

sacrifice and honour for Armed Forces,” 30 December, 2015.<br />

On this topic, refer to David B. Roberts, “A New Era for Gulf Military Forces,” Gulf Affairs, Oxford Gulf & Arabian Peninsula Studies<br />

Forum, University of Oxford, Spring 2016, pp.6-8.<br />

Samir Salama, “Revealed: Names of 341 FNC poll candidates,” Gulf News, 31 August, 2015.<br />

“Profiles: Meet the preliminary 20 newly elected FNC members,” The National, 4 October, 2015.<br />

“FNC Election 2015: as it happened,” Gulf News, 3 October, 2015.<br />

Mehran Kamrava, “Weak States in the Middle East,” in Fragile Politics: Weak States in the Greater Middle East, ed. Mehran Kamrava<br />

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 1-28.<br />

<strong>Identity</strong> & <strong>Culture</strong> in the 21st Century Gulf |Autumn 2016 9

II. Analysis<br />

A cargo ship is docked at Jebel Ali port in Dubai, UAE on 14 March 2006.<br />

Saruq Al-Hadid to Jebel Ali: Dubai’s Evolving<br />

Trading <strong>Culture</strong><br />

by Robert Mogielnicki<br />

ecent discoveries at the Saruq Al-Hadid archeological site located outside of Dubai in the United<br />

Arab Emirates (UAE) demonstrate the emirate’s connection to key trading routes dating as far back<br />

as 4,000 years ago. In light of the July 2016 inauguration of the Saruq Al-Hadid Archeology Museum by<br />

Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al-Maktoum, Ruler of Dubai, it is clear that the government is making<br />

a conscious effort to reconstruct this early trading identity and promote it broadly to the public. Sheikh<br />

Mohammed’s comments at the museum’s opening reinforced the links between the archeological museum<br />

and Dubai’s trading culture: “Museums reflect the culture of the nation.” 1<br />

Saruq Al-Hadid<br />

While the museum links the region’s early trading culture to that of today, it is important to note the continual<br />

evolution of Dubai’s mercantile traditions, which can be broadly categorized into three distinct phases: i)<br />

Saruq Al-Hadid, ii) Dubai Creek and iii) the proliferation of free zones. The evolution in the location of trading<br />

hubs and nature of trade over these periods had clear implications for the infrastructure of modern Dubai<br />

and for the identity of its inhabitants. Indeed, Dubai’s free zones are the modern-day manifestations of the<br />

trading culture that started in Saruq Al-Hadid and further developed around Dubai Creek.<br />

10 Gulf Affairs

II. Analysis<br />

The fortuitous position of Saruq Al-Hadid between strategic trading routes shaped Dubai’s early trading<br />

culture. The ancient Iron Age site of Saruq Al-Hadid is located in the Rub Al-Khali desert area of Dubai’s<br />

southern border. Nestled further inland than the coastal cities of Dubai and Abu Dhabi, the area flourished<br />

as a center for metalwork manufacturing. Evidence from the site suggests that its inhabitants used<br />

domesticated camels to facilitate trade to current day Egypt, Syria, Iran, Oman, Bahrain, India, Pakistan,<br />

and Afghanistan. Rashad Bukhash, director of the Heritage Department of Dubai Municipality, explained<br />

that the site “shows the age-old tradition of Dubai being a hub for trade even in those days.” 2 Appropriately,<br />

the Saruq Al-Hadid Archeological Museum is located along the historic Dubai Creek in the Shindagha<br />

district of Dubai.<br />

Dubai Creek<br />

Before the discovery of Saruq Al-Hadid, historians tended to trace the early history of Dubai to the 18 th century<br />

settlements around Dubai Creek. The arrival of the Al-Maktoum tribe to Dubai in the 1830s helped<br />

formalize much of the commercial activity around the creek and also encouraged the immigration of new<br />

waves of Indian and Persian merchants. This early influx of non-Arab merchants helped to shape the modern<br />

socio-economic demographics of Dubai. Today, Indians serve as the largest national demographic of<br />

residents in Dubai, with Indians and Pakistanis contributing<br />

25 and 12 percent respectively to the emirate’s population<br />

of approximately 2.5 million residents. 3 Similarly,<br />

Iranians continue to play key roles in social, business<br />

and advisory circles, and estimates suggest that Iranians<br />

may account for 16-20 percent of Dubai’s population. 4<br />

v<br />

Located in the northeastern corner of the emirate, the Dubai Creek area consists of the historic districts of<br />

Bur Dubai and Deira. The original spice and gold markets, poignant remnants of the area’s more promising<br />

past, are situated near the northern shore of the creek in Deira.<br />

Although it served as a bustling commercial hub for centuries, the creek’s shallow waters prevented the<br />

trading hub from receiving large maritime vessels. After various attempts to dredge the creek throughout<br />

the later part of the 20 th century, as well as the opening of Port Rashid in 1972, Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed<br />

Al-Maktoum commenced plans to construct the Jebel Ali Port a further 50 kilometers along the coastline<br />

toward Abu Dhabi.<br />

Free Zones<br />

The evolution in the location of trading<br />

hubs and nature of trade over these<br />

periods had clear implications for the<br />

infrastructure of modern Dubai and<br />

for the identity of its inhabitants.<br />

The Jebel Ali Port heralded a new age in Dubai’s trading legacy—the Free Zone Era. The Jebel Ali Free<br />

Zone Authority (JAFZA), originally created in 1985 to facilitate the warehousing and storage of shipments<br />

entering the port, became the first free zone to operate in Dubai. Today, the free zone hosts over 7,000<br />

companies and houses approximately 60,000 residents. The success of Jebel Ali served as a model for other<br />

well-known free zones, including the Dubai Airport Free Zone Authority (DAFZA) and the Dubai Multi<br />

Commodities Centre (DMCC). And while earlier trading cultures in Dubai naturally developed around<br />

strategic locations, the rise of free zones represented a more direct, pragmatic development of Dubai’s trading<br />

culture on the part of the government.<br />

<strong>Identity</strong> & <strong>Culture</strong> in the 21st Century Gulf |Autumn 2016 11

II. Analysis<br />

Table 1: Free Zone Distribution in the UAE<br />

Broadly speaking, a free zone is a duty-free area<br />

outside of customs control. The traditional free zone<br />

model consists of a physical location wherein firms<br />

are incentivized to increase domestic exports, generate<br />

foreign direct investment (FDI), employ locals,<br />

and transfer new technologies and skills to the national<br />

workforce. However, a critical component of<br />

free zones in Dubai involves the right for foreign investors<br />

to maintain 100% ownership of their companies,<br />

rather than sharing ownership with a local<br />

Emirati citizen. Currently, there are approximately<br />

24 functioning free zones operating in Dubai, and<br />

the number of Dubai-based free zones vastly outnumbers<br />

those in neighboring emirates (Figure 1). 5<br />

Yet not all free zones in the emirate conform to the standard free zone definition or emulate the Jebel Ali<br />

Free Zone model. TECOM Group, a developer and operator of business communities and member of Dubai<br />

Holding, manages eleven free zones that contain 5,100 companies and employ 76,000 people. The group<br />

refers to these free zones as ‘business communities,’ and they tend to be less involved with imports and exports.<br />

Instead, these business communities function as knowledge hubs that attract a diverse demographic<br />

of human capital and offer a varied set of commercial, tourist, and residential services. 6 For example,<br />

Dubai residents can live, work and shop in Dubai Media City. When compared to more traditional zones<br />

like Jebel Ali Free Zone and the Dubai Airport Free Zone, TECOM Group’s free zones are seamlessly integrated<br />

into the social fabric of Dubai.<br />

While the traders of Saruq Al-Hadid and Dubai Creek settled in strategic overland trading routes or along<br />

natural saltwater inlets, the trading culture of 21 st century Dubai was shaped predominantly by manmade<br />

projects. Technological innovations in cargo shipping, commercial aviation, and services further changed<br />

the nature of trade, and Dubai’s government responded by developing the most advanced free zone sector<br />

in the region. Free zones shifted the nexus of trade away from Dubai Creek and distributed commercial<br />

activity more broadly throughout the emirate. At the same time, these new commercial hubs attracted<br />

foreign professionals, tourists, and residents from across the globe. Free zones will continue to dominate<br />

Dubai’s trading culture for the foreseeable future, but it is important to remember that these zones are<br />

intrinsically linked to a much older trading legacy.<br />

Robert Mogielnicki is a DPhil candidate in Oriental Studies and member of Magdalen College where he<br />

examines the political economy of free zones in GCC countries.<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5<br />

6<br />

“Mohammed bin Rashid inaugurates Saruq Al Hadid museum at Al Shindagha,” Emirates News Agency, July 4, 2016.<br />

Sajila Saseendran, “Dubai’s trade links date back 4,000 years,” Gulf News, July 22, 2016.<br />

Statistics from Euromonitor; reported in Khamis, Jumana, “Indians, Pakistanis make up 37% of Dubai, Sharjah, Ajman population,” Gulf<br />

News, August 6, 2015.<br />

Jure Snoj, “UAE’s population – by nationality,” Business Qatar Magazine, April 12, 2015.<br />

Based on the author’s latest D.Phil research on free zones in the GCC. However, it is important to note that new zones are often emerging<br />

and announcements for new zones appear regularly.<br />

Well-known free zones operated by TECOM Group include Dubai Internet City, Dubai Media City, Knowledge Village and Dubai International<br />

Academic City.<br />

12 Gulf Affairs

II. Analysis<br />

View of Sharq district with Al-Hamra tower in the center. Kuwait City, Kuwait, 2015.<br />

IconiCity: Seeking <strong>Identity</strong> by Building Iconic<br />

Architectures in Kuwait<br />

by Roberto Fabbri 1<br />

he Emirates Airlines website welcomes visitors by stating that Dubai’s iconic architecture is not only<br />

encouraged, but “actively pursued.” A subsequent list of evidence describing extreme heights, unconventional<br />

shapes, and cutting-edge materials supports the claim. 2 The Gulf states have turned to architecture<br />

as a way to build globally-recognized skylines. This wave of new, iconic buildings is often an attempt to<br />

build an urban uniqueness which, moreover, is part of the quest for a stronger national and social identity.<br />

A landmark is traditionally a symbol that raises a sense of belonging in the local population, but normally<br />

monuments are few in the urban fabric, and they are limited to specific spaces of public interest. But what<br />

happens when the city itself becomes composed of a significant number of icons, and the urban fabric is<br />

just the “in between”? Kuwait is an interesting case in the Gulf because it has a more consolidated pre-existing<br />

urban form, and these ‘new objects’ are not related at any level, neither in scale nor in language to<br />

the surrounding context. The current transformation process focuses on the development of isolated elements,<br />

self-standing on their own plot and auto-referential. Around them, the connective fabric is left with<br />

poor design and modest construction quality.<br />

<strong>Identity</strong> & <strong>Culture</strong> in the 21st Century Gulf |Autumn 2016 13

II. Analysis<br />

Icon & media<br />

The architectural press normally welcomes these ‘photogenic’ buildings and presents the city not by its<br />

‘nature’ but by its ‘suit.’ One can argue that, apart from the different layers of reading or meaning that a<br />

building can generate, architecture is the expression of the society that produces it. In other words, architects<br />

and clients are transforming the building into a sort of ‘tridimensional logo’ implementing a series of<br />

design choices: an unusual, unique, and symbolic shape different from any other ‘competitor.’ There are<br />

certain requirements: The icon shall be a technical challenge that raises engineering to an extremely high<br />

standard, where complexity consolidates its identity. Size is another crucial aspect, and specifically the<br />

vertical dimension. Iconic architecture has to be big to stand out in the city fabric. Furthermore, the name<br />

and the fame of the designer are also major factors in establishing an iconic building.<br />

This design approach often brings these buildings very close to an industrial-design object, self-centered<br />

and self-referent. Consequentially iconic architecture has, in most cases, a conflicting dialogue with its<br />

context, because it is meant to communicate to a worldwide audience, while the local ‘assimilation’ is more<br />

problematic.<br />

Iconizing Kuwait<br />

Iconic buildings are a worldwide phenomenon, and the examples in the Gulf are not too different from<br />

what is happening in the rest of the world. One could argue that prestige projects are more prevalent in the<br />

region due to the lack of pre-existing local monuments which can catalyze the sense of belonging. However,<br />

this would not entirely reflect reality, since at the very initial inception of the urban and social modernization<br />

in the Gulf in the mid-20 th century, the construction of representative buildings was at the center<br />

of every governmental plan. 3 Today, Abu Dhabi, Doha and Dubai have all become archetypes for cities in<br />

transformation in the region, while Kuwait, on the other hand, is somehow different from its neighbors.<br />

Kuwait has a more complex urban fabric and a longer urban history, one punctuated by a large number<br />

of highly experimental projects since the early 1950s. 4 The city is also in transformation, but the vision is<br />

less evident, cohesive, and advertised than in the other Gulf states. In the last decade many projects were<br />

announced to modernize the city and keep pace with the region, including a new airport, two new towers<br />

for the Central Bank and the National Bank of Kuwait, and a new hospital center, among others.<br />

The city center is now also in transformation, and despite the fact that this part of the city would need<br />

more consolidation than ‘intrusions,’ the construction of skyscrapers is now mostly focused here, where<br />

large plots are abandoned or under-used. These are mostly initiatives by private actors investing in separate<br />

plots without a coordinated vision. The ‘in between’ is a non-space left with no integrated functions or<br />

quality: a very loose and undefined canvas amid vertical objects unrelated to each other or the city itself.<br />

In contrast, Yasser Mahgoub’s reading of the build environment of Kuwait concludes that multiple identities<br />

should be accepted as a natural result of the actions of different groups in the society, and architecture<br />

is the representation of this local contemporary condition and desire. 5 In principle, this argument is convincing,<br />

but the quid pro quo is the acceptance of a heterogeneous approach to shapes, forms, and languages.<br />

This tradeoff was well described in the early 1960s by Saba George Shiber in his critique of Kuwait City’s<br />

transformation: “Architecture became an exercise in acrobatics and not an endeavor in creation, economics<br />

and organicism. . . . It has become rare to find lines anchored to the earth. Instead, they all seem pivoted<br />

14 Gulf Affairs

II. Analysis<br />

to point restively to outer space.” 6 Paraphrasing<br />

Shiber, proportions, shapes, materials, colors, and<br />

placements are so different that it is very difficult<br />

to perceive urban unity.<br />

In 2011 Kuwait City received its own internationally<br />

recognizable iconic building: Al-Hamra tower.<br />

It has everything necessary to be considered an icon: a prominent designer, oversized structure, technical<br />

challenges, and a unique shape. It is not difficult to imagine the role that this 400-meter high business hub<br />

plays in the skyline of the city. Its sculptural shape and flaring walls demanded extreme engineering work<br />

and placed Al-Hamra among the world’s most complex tall buildings.<br />

The official company brochure highlights a long list of technical data and new records achieved: the tallest<br />

carved skyscraper in concrete, the largest office building in the country, and the largest stone façade. 7<br />

Among other technical marvels, one specific design solution is worth mentioning. The tower is, in a way,<br />

site-specific. Its design is still not related to the urban scale nor to the city context, but it is partially the result<br />

of solar condition studies. The tower is oriented so that the inclined flaring wall protects and shades the<br />

southern elevation, where the desert sun can be more powerful. Nevertheless, when the building touches<br />

the ground there is no sign of urban mitigation or integration with the fabric. It sits on its own plot just like<br />

any other object in the surrounding area, demonstrating once again the lack of urban design of this part of<br />

the city.<br />

Gary Haney, from the design firm SOM, 8 defines Al-Hamra as “a statement (that) will be the landmark of<br />

Kuwait for the next generation.” 9 In general, the local population seems to have embraced Al-Hamra as a<br />

new landmark. On the contrary, tenants did not find it completely attractive: the high-end shopping mall<br />

on the lower levels provides a vast array of restaurants and boutiques, but a large number of office floors<br />

are still empty. So what kind of statement does Haney refer to? Which ideals or which shared feelings<br />

will the future generations of Kuwait see in this tower? An answer comes from the brochure issued by the<br />

building management company: “Hamra is a business monument!” 10 So the icon is a monument, and in a<br />

contemporary commercial-oriented society the monument is essentially a ‘business memorial.’<br />

Connecting the past to the present<br />

Iconic architecture has, in most cases, a conflicting<br />

dialogue with its context, because it<br />

is meant to communicate to a worldwide audience,<br />

while the local ‘assimilation’ is more<br />

problematic.<br />

In the same brochure a picture showcases Al-Hamra facing the sea with the Kuwait Towers, the country’s<br />

1970s national monument, in the background. The intention probably was to present a sense of continuity<br />

with the past despite the fact that to make space for the new tower, one of the oldest cinemas in town, a<br />

vivid expression of 1960s modern heritage, was demolished. All this leads to a few considerations on how<br />

much the two towers reflect the changing needs of Kuwaiti society in their current time. Just like Al-Hamra,<br />

the Kuwait Towers are definitely an icon representing the country’s goals of modernization, but the<br />

latter also form a narrative space recounting the motivations behind a project of public interest. The towers<br />

are a water reservoir with all the meanings that water has in a desert land like Kuwait. With their shape,<br />

materials, position, and scale, the Kuwait Towers are evocative objects that bring back memories of the<br />

past, reminding the country of its roots.<br />

On the other end, Al-Hamra does not show any sense of continuity with the past. It is presented to the<br />

public as a display of current financial power, but it could be better interpreted as an expression of a higher<br />

<strong>Identity</strong> & <strong>Culture</strong> in the 21st Century Gulf |Autumn 2016 15

II. Analysis<br />

level of confidence in the country. The lack of trust and the uncertain international situation in the aftermath<br />

of the 1990 Iraqi invasion of Kuwait virtually froze, with a few exceptions, major investments for<br />

more than a decade.<br />

This traumatic event and its long tail arrested the drive toward modernization that had been consistently<br />

pursued for over 40 years through the erection of highly symbolic architecture. Unlike other Gulf countries,<br />

recent iconic architecture in Kuwait seems to express a general feeling of recovered confidence, perfectly<br />

reflected in bald technical features, more than the quest for a national identity or the homogenized vision<br />

of a contemporary city.<br />

Dr. Roberto Fabbri is an architect and professor at University of Monterrey; he worked five years in Kuwait<br />

and is the co-author of Modern Architecture Kuwait 1949-89 (2016).<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5<br />

6<br />

7<br />

8<br />

9<br />

10<br />

Acknowledgement: This research and paper was developed during a fellowship research program at the Center for Gulf Studies – American<br />

University of Kuwait.<br />

“Iconic Dubai Architecture | Sightseeing in Dubai | Discover Dubai | Emirates,” www.emirates.com, accessed 01 September, 2016.<br />

Compare for example Todd Reisz’s analysis of the World Trade Center in Dubai, in Structures of Memory, catalogue of the exhibition of<br />

the National Pavilion United Arab Emirates, La Biennale di Venezia, 2014, pp. 81-82.<br />

Regarding Kuwait’s architectural production in the recent past, see Roberto Fabbri, Sara Saragoça Soares, and Ricardo Camacho, Modern<br />

Architecture Kuwait 1949-89 (NiggliVerlag: Zurich, 2016).<br />

Yasser Mahgoub, “Hyper <strong>Identity</strong>: the Case of Kuwaiti Architecture,”Archnet-IJAR, International Journal of Islamic Architecture, 1:1<br />

(March 2007): 84.<br />

Saba George Shiber, “Architecture and Urban Aesthetics in Kuwait: Significance or Superficiality,” The Kuwait Urbanization: Documentation,<br />

Analysis, Critique (Governmental Press: Kuwait, 1964), 306.<br />

Al Hamra Business Tower Facts and Figures, www.alhamra.com.kw, accessed 2 October, 2016.<br />

Skidmore, Owings & Merrill was the lead consultant, together with Al Jazeera as local partner, Al-Ahmadiah as contractor, and Turner<br />

as project manager.<br />

“Record breaker,” Gulf Construction Online, accessed 22 Sept. 2016<br />

Al-Hamra Tower, Company Brochure, undated, p.20<br />

16 Gulf Affairs

II. Analysis<br />

Kuwaiti men rally in front of the parliament building to demand the dissolution of the 2009 parliament in Kuwait City, Kuwait on 1<br />

October 2012.<br />

G<br />

The Banality of Protest? Twitter Campaigns in Qatar<br />

by Andrew Leber and Charlotte Lysa<br />

iven restrictions on public protest and political organizing across much of the Arab Gulf, a New York<br />

Times reporter noted in 2011 that social media seemed “tailor-made for Saudi Arabia” and its fellow<br />

monarchies. 1 In the midst of the Arab Spring, online pages for the now-defunct Eastern Province Revolution<br />

helped coordinate protests in the Kingdom, even as @angryarabiya—now in exile in Denmark after<br />

repeated arrests—documented the violent suppression of demonstrations in Bahrain on Twitter.<br />

In the years since, though, protests have disappeared as Gulf governments have variously deterred activists<br />

with harsh crackdowns and forestalled grievances with generous handouts. Subsequent portrayals of<br />

Gulf social media have shifted to emphasize the online expression of collective identities over the potential<br />

for collective action, however much the two may be linked. Alexandra Siegel has highlighted the Gulf as<br />

a key nexus of polarizing sectarian rhetoric on Twitter, driven by the regional rivalry between the mostly<br />

Sunni Gulf monarchies and Shia Iran. 2 At the opposite extreme, social media platforms are presented as<br />

windows into the region’s conspicuous consumption, exemplified by young and restless Kuwaiti men posing<br />

with exotic animals in the VICE documentary “The Illegal Big Cats of Instagram.” 3<br />

Beyond broad sectarian clashes and individual excess, the enduring image of GCC nationals as “rentier<br />

<strong>Identity</strong> & <strong>Culture</strong> in the 21st Century Gulf |Autumn 2016 17

II. Analysis<br />

citizens” prevails, supposing quiescent subjects content to receive handouts fuelled by state-controlled oil<br />

and gas revenue. The dearth of formal institutions of accountability—aside from a dysfunctional parliament<br />

in Kuwait and a few minor elected bodies—militates against most individuals effecting meaningful<br />

political or policy change through official channels.<br />

Yet discontent, though muted, is far from absent online. Citizens lodge many claims and complaints with<br />

‘the government’ on Twitter, Facebook, and even Snapchat. Much as these online campaigns can seem<br />

banal, only reinforcing a transactional relationship between ruler and subject, they lead Gulf citizens to<br />

articulate a sense of political and social identity from below, in contrast with top-down visions engineered<br />

by the region’s ruling elites.<br />

On the campaign trail<br />

This dynamic has played out even in Qatar, which is domestically quiet and has less of the overt online surveillance<br />

increasingly visible in the neighboring United Arab Emirates. 4 Unlike elsewhere in the MENA<br />

region, where various formal parliaments (however unrepresentative) have been operational for decades,<br />

Qatar has no tradition of formal political representation beyond a heavily circumscribed Municipal Council.<br />

One article by Justin Gengler, among the few insightful articles on Qatar’s body politic, outlines the many<br />

factors that militate against political activism, from a small native population to the country’s extreme<br />

per-capita resource wealth. 5 To be sure, collective protests against foreign oil companies helped foster a<br />

sense of a “Qatari” national identity in the 1950s and 1960s, linking merchants, slaves, and free Qataris on<br />

the peninsula. 6 For more than 30 years, though, most citizens’ public complaints about government agencies<br />

and regulations have been channeled through a state-run call-in radio show entitled “Good Morning,<br />

My Beloved Country.” 7<br />

The challenge for researchers interested in<br />

Gulf political identities is to document and analyze<br />

discussions of rights and responsibilities<br />

across a wide range of online communities.<br />

When semi-official complaints go nowhere,<br />

though, Qataris on Twitter and other social<br />

media often act in tandem with influential columnists<br />

and cartoonists to push back against<br />

corporations and state agencies they portray as<br />

unresponsive, incompetent, and even corrupt.<br />

As Hootan Shambayati noted in the case of Iran, the largesse of oil-rich states can often channel citizens’<br />

discontent along moral and ideological vectors rather than quelling it outright. 8 Accordingly, many Twitter<br />

campaigns in Qatar are instances of “moral panic,” denouncing cultural displays deemed to cater to an elite<br />

image of Qatar as a cosmopolitan “world city” at the expense of its conservative native population.<br />

In early 2016, a widespread Twitter protest targeted the British-American film “The Danish Girl,” which is<br />

about a transgender woman in the 1920s, on the hashtag #No_To_Showing_The_Danish_Girl. The Ministry<br />

of <strong>Culture</strong> soon tweeted back that they had decided to ban the movie. 9 Similar controversy has attended<br />

other performances, such as Australian singer Kylie Minogue, with events coordinators going so far as<br />

to announce performers at the last possible minute to forestall the potential for protest. 10<br />

While rarely straying into overt political demands, citizens also regularly criticize the performance of government<br />

agencies and state-owned enterprises. Qatar Airways was subject to an online campaign driven<br />

by customers demanding better service and more employment opportunities for Qataris. 11 Schools, hospi-<br />

18 Gulf Affairs

II. Analysis<br />

tals, and roads frequently attract criticism, with proposed fee hikes in government schools almost provoking<br />

a boycott in 2013. 12<br />

Instead of quietly accepting their government’s stewardship, citizens ratchet their development expectations<br />

ever-higher in the knowledge that their country possesses vast financial resources. The more these<br />

online discussions link government missteps to a perceived lack of accountability and transparency, the<br />

more they reinforce the idea of a Qatari body politic denied real input on key matters of social and economic<br />

development.<br />

Death and denial<br />

Two recent online protests exemplify these processes and reflect an online political presence that is far<br />

more populist and conservative than the liberal, cosmopolitan image often presented by Qatar’s rulers.<br />

This past May, one Twitter campaign stemmed from the death of Qatari Shorooq Al-Sulaiti in a government-run<br />

women’s hospital following complications from childbirth. When her husband’s official inquiries<br />

into the circumstances of her death went nowhere, he reached out to prominent columnist Faisal Al-Marzuqi.<br />

13 Al-Marzuqi in turn targeted the Ministry of Public Health (MOPH) Twitter account with criticisms,<br />

popularizing hashtags such as #We_Are_All_ Shorooq_Al_Sulaiti. Ultimately, the online campaign attracted<br />

coverage from Arabic newspapers Al-Raya and Al-Arab as well as the English-language website<br />

Doha News, in addition to a number of pointed satirical cartoons. 14 The Ministry finally issued a public update<br />

on the investigation on July 14 th , which was followed by a brief lull in online activity (Figure 1). Sulaiti’s<br />

husband as well as Al-Marzuqi and other Qataris have continued their online criticisms, though, with<br />

the public prosecutor’s office finally opening an investigation into the ongoing case this past September. 15<br />

Figure 1: Twitter activity mentioning Shorooq Al-Sulaiti,<br />

July 2016.<br />

Figure 2: Hashtags targeting Doha News,<br />

August 2016.<br />

# of Tweets<br />

0 100 200 300 400 500<br />

All Tweets<br />

Targetting MOPH<br />

Al-Raya<br />

Article<br />

MOPH<br />

Response<br />

Jul 01 Jul 04 Jul 07 Jul 10 Jul 13 Jul 16 Jul 19 Jul 22 Jul 25 Jul 28<br />

July 1-28, 2016<br />

# of Tweets<br />

0 100 200 300 400 500<br />

Doha News op-ed<br />

published<br />

Response op-eds<br />

published<br />

Aug 01 Aug 03 Aug 05 Aug 07 Aug 09 Aug 11 Aug 13<br />

August 1-14, 2016<br />

A more recent incident of “moral panic” occurred after Doha News published an opinion piece about the<br />

difficulties of being Qatari and gay. 16 This provoked a furious online response by many Qatari Twitter-users<br />

outraged by the perceived assault on public morality and Qatar’s Islamic character. First, one minor<br />

commentator for Al-Sharq touched off #We_Demand_The_Investigation_Of_Doha_News, with some users<br />

tagging the Ministry of Interior (@MOI_Qatar) trying to provoke a more forceful response from the<br />

state. 17 Columnist Maryam Al-Khater stoked further calls for government action through an article in<br />

<strong>Identity</strong> & <strong>Culture</strong> in the 21st Century Gulf |Autumn 2016 19

II. Analysis<br />

Al-Sharq and on Twitter with the hashtag #Stop_Promotion_Of_Vice_In_Qatar. In both, she implored<br />

the government to take firm action to shut down the website. 18 Despite an intense spate of initial activity,<br />

though, the hashtags failed to gain much momentum or high-level support on Twitter, dropping from use<br />

just a few days later (Figure 2).<br />

Conclusion<br />

Various aspects of a nebulous “rentier state theory” have dominated academic discussion of the Gulf for<br />

decades, expressing the sense that the vast oil wealth of these monarchies has allowed them to “buy off”<br />

discontent time and again. Yet even in Qatar, which is wealthiest per-capita in the GCC and has practically<br />

no organized political opposition, nationals have come to use online forums such as Twitter to express<br />

and reinforce a sense of Qatari identity. The challenge for researchers interested in Gulf political identities<br />

is to document and analyze discussions of rights and responsibilities across a wide range of online communities,<br />

as GCC citizens migrate to newer platforms such as Instagram and Snapchat.<br />

At their core, these discussions contribute to a sense of citizenship that demands accountability in state<br />