Wildlife Breeders Journal 2016

The second edition of the well renowned Wildlife Breeders Journal published by Wildlife Stud Services in South Africa.

The second edition of the well renowned Wildlife Breeders Journal published by Wildlife Stud Services in South Africa.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Wildlife</strong> stud services<br />

1

2<br />

<strong>2016</strong><br />

Wildtelers Joernaal<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Breeders</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

WILDLIFE STUD SERVICES<br />

Editorial 6<br />

From the <strong>Wildlife</strong> Stud Services office 8<br />

ECONOMIC FORECAST OF THE GAME<br />

INDUSTRY<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> industry expected to continue<br />

to grow 12<br />

BREEDING<br />

The Golden King Wildebeest 16<br />

Farming with mini antelope 21<br />

The history of the Livingstone eland in<br />

South Africa 32<br />

Good genetic health of African buffalo 38<br />

Inbreeding and disease resistance 42<br />

Using breeding values to improve desired traits in<br />

wildlife 44<br />

The value of large scale genetic<br />

evaluations 48<br />

Ranch lions in South Africa 52<br />

Pioneer game breeder: Piet Warren 56<br />

WRSA <strong>Wildlife</strong> Breeder of the year 2014:<br />

Crous-brothers 58<br />

Good Stockmanship: 4 Daughters Ranching 59<br />

DNA TESTING<br />

Table of<br />

CONTENTS<br />

REPRODUCTION<br />

Fertility evaluation of wildlife:<br />

Interesting findings 76<br />

NUTRITION<br />

Nutritional deficiencies and their effects on<br />

production and coat colour 81<br />

Feeding to optimise horn growth of trophy game 87<br />

Feeding systems for game 94<br />

The importance of fibre in ruminant nutrition 101<br />

HEALTH<br />

An overview of parasites in wildlife 103<br />

GENERAL MANAGEMENT PRACTICES<br />

Game camp systems and layouts 106<br />

Passive handling of wildebeest:<br />

a practical example 116<br />

Passive handling of buffalo: a practical example 119<br />

Farmers’ responses to poached rhino 124<br />

Fencing specifications for wildlife 128<br />

Weed control in a game farming operation: best<br />

practices 132<br />

Legal support for the wildlife sector in<br />

South Africa 138<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> TUT-Biobank 62<br />

Sable antelope nuclear origin testing 65<br />

Essential background information for DNA profile<br />

parentage verification 67<br />

Parentage tests for predators 72<br />

GAME MEAT<br />

The potential of game meat as a local and export<br />

commodity 144<br />

WRSA’s international quality standard for<br />

game meat 148<br />

Game meat processing opportunities 154<br />

INVESTMENTS, MARKETING AND AUCTIONS<br />

Investment opportunities in wildlife industry 158<br />

Best practice when setting up a<br />

sales agreement 162<br />

Principles for composing a business plan for a game<br />

farming enterprise 167<br />

2015 Record game prices 171<br />

CALENDAR<br />

Auction calendar <strong>2016</strong> 174<br />

Important dates 176<br />

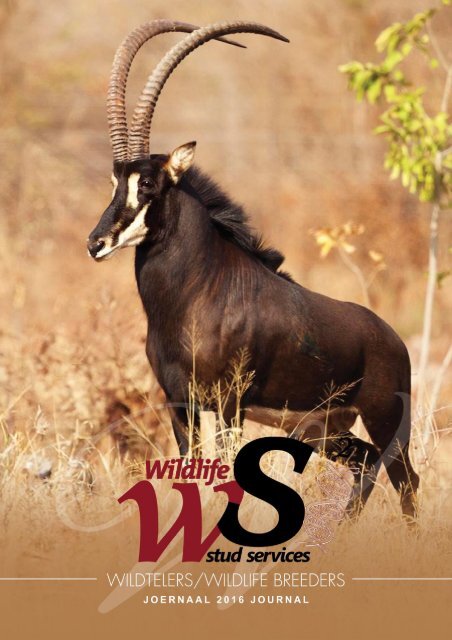

Front Cover: Hercules (48 3/8”)<br />

Owner: Amanzi Private Game Reserve<br />

Breeder: Piet Warren<br />

Photo by: Arcon Media<br />

Back Cover: P29<br />

Owner: Leopard Rock Game <strong>Breeders</strong><br />

Breeder: Leopard Rock Game <strong>Breeders</strong><br />

Photo by: Arcon Media

Adverts<br />

4 Daughters Ranching 60-61<br />

Afrivet 104<br />

Allflex 71<br />

Alzu Feeds 98<br />

Amanzi Private Game Reserve 22-24<br />

AnimalSure<br />

IFC<br />

Avenatus 136<br />

Bateleur <strong>Wildlife</strong> Services 153<br />

Clinomics 64<br />

Crous-brothers 1<br />

DJ Farmer 169<br />

Dreyer van Zyl Game 15<br />

Ekim <strong>Wildlife</strong> 170<br />

Embrio Plus 79<br />

Five Star ID 115<br />

GameLab 166<br />

Gariep Eco Reserve 47<br />

Giraffae Game <strong>Breeders</strong> 163<br />

Hageland <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Breeders</strong> 159<br />

Jan Fourie Wild 29<br />

Karibu Stud 2<br />

Klein Buisfontein Ranch 19<br />

Kwaggashoek Game Ranch 37<br />

Lekkerleef Wild Stoet 121<br />

Lumarie 5<br />

Meadow 86<br />

Oak Lane Farm 10-11; 88-89 & IBC<br />

Obaro 51<br />

Opti Feeds 100<br />

Prinsloo Game <strong>Breeders</strong> &<br />

Louisiana Wildsboerdery 75<br />

RCL Foods: Epol & Molatek 93<br />

SafeTag® 147<br />

SA Predator Association 54<br />

Unistel 69<br />

Van Zyl Boerdery 137<br />

Van’s Auctioneers 175<br />

Vleissentraal Bosveld 173<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> Stud Services 111<br />

Opinions expressed in the <strong>Journal</strong> are not necessarily the view of <strong>Wildlife</strong> Stud Services.<br />

WS 2 does not accept any of the claims made in advertisements.<br />

Brought to you by <strong>Wildlife</strong> Stud Services<br />

(PTY) Ltd.<br />

Tel: +27 (0) 12 804 6118<br />

Fax: +27 (0) 86 552 8552<br />

E-mail: info@ws2.co.za<br />

Web: www.ws2.co.za<br />

Coordination of Publication<br />

Firefly Publications (Pty) Ltd.<br />

Tel: +27 (0) 51 821 1783<br />

E-mail: palberts@telkomsa.net<br />

Design & Layout: Caria Vermaak<br />

Advertisement design: Donovan Heunis

<strong>Wildlife</strong> stud services<br />

5

Editorial<br />

Dr Paul Lubout<br />

Managing Director<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> Stud Services<br />

DNA SEQUENCING<br />

“Crystal ball” or “Curve ball”<br />

The use of DNA sequencing data (SNP,<br />

whole genome, next generation…) of<br />

wildlife in South Africa is in most cases<br />

grossly misunderstood. The sequencing can<br />

be performed locally and globally (SA, USA,<br />

AUS, etc.), “SO WHAT!” Will the results<br />

be useful to yourself and/or your breeding<br />

advisors? This comes from a belief that your<br />

genetic code can predict your animal’s future<br />

value. In very rare instances it can, but for<br />

the majority of animals genetic sequencing is<br />

still not well enough understood to be of real<br />

value. The literature helps us to explain why.<br />

Research conducted by Janssens et al. (2006)<br />

on predictive genetic testing using sequencing,<br />

confirmed that genetic SNP profiling is not a<br />

Yes/No answer but rather a continuous curve<br />

of possibilities - some more strong than others.<br />

Another research team was keen to point<br />

out that the expression of a multiple gene<br />

trait is as much about environmental factors<br />

as genetics. In fact, common traits such as<br />

horn length and animal weight develop as a<br />

result of very complex interactions between<br />

6<br />

<strong>2016</strong><br />

Wildtelers Joernaal<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Breeders</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

<strong>Wildlife</strong> stud services<br />

various genes, many of which we do not fully<br />

understand. Roughly 21% of animals’ live<br />

weight is genetic, while the rest is up to the<br />

game ranchers to optimise the environment,<br />

management, nutrition etc. of their animals.<br />

Very few traits, with exceptions of single<br />

gene traits such as coat colour, have much of<br />

a degree of predictability at this time. In 2008<br />

it was flagged that the complexity of multiple<br />

gene traits, such as animal weight may “limit<br />

the opportunities for accurate prediction of<br />

these traits without expansive pedigree and<br />

performance databases” and we haven’t<br />

moved forward significantly in this regard.<br />

The hope is that in the future we can not only<br />

better predict but also use this information<br />

more responsibly when selecting for these<br />

traits. As soon as I wrote that, I heard the<br />

“anti- selection” bell ringing. The belief that<br />

wildlife breeders will use their increased<br />

knowledge against conservation goals is<br />

always a worry - but we should remember<br />

that better education means better choices,<br />

better decisions, and the ability to change.<br />

If genetic prediction is where we are going<br />

perhaps a smarter response would be to<br />

promote responsible selection (reproduction,<br />

adaption, longevity, disease resistance, horn<br />

length, weight, etc.), while maintaining<br />

genetic diversity based not on old doctrines<br />

but on impact..... We can’t hold back the tide<br />

of progress, but we can get ready for it. The<br />

wildlife breeding industry needs to embrace<br />

this technology to manage genetic diversity<br />

over the fences.<br />

For now wildlife breeders should not be too<br />

concerned about sequencing although it<br />

can be done but does not produce a reliable<br />

prediction of the animal’s genetic value - the<br />

scientific evidence just isn’t there to support<br />

their claims. The science of predictability<br />

does not yet stack up. <strong>Breeders</strong> should<br />

however store DNA samples for future use<br />

once the genetic predictions mature.<br />

So, for a bit of fun, is it worth getting your<br />

animals DNA code examined? Apart from<br />

you “paying for it”, is there any value in<br />

getting your animals’ coding sequence<br />

carried out? There potentially could be.<br />

If you use a company which is based in<br />

America, you are essentially offshoring your<br />

data and these companies are free to sell it<br />

on to other companies and marketers. The<br />

Australians caution that genetic tests are not<br />

always ‘black and white’ and that receiving<br />

information out of context or without support<br />

could have profound adverse effects on your<br />

success.<br />

In summary, if you fancy a quick route<br />

to mapping your animal’s ancestry or an<br />

individual animal’s DNA sequence, go<br />

ahead and get them coded. However, you<br />

won’t be able to make any useful decisions<br />

on what you find out yet, because reliable<br />

predictions of genetic values for multiple<br />

gene traits without extensive pedigree and<br />

performance are not possible. So store your<br />

DNA samples, do DNA profiles for parentage,<br />

record your animals (pedigree), performance<br />

test (measure) and save your money until<br />

genetic predictions can be done and linked<br />

to sequenced data. Then, and only then, can<br />

you use the technology of genome mapping<br />

successfully.<br />

7

From the<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> Stud Services office<br />

Jaqqui Clute<br />

Office Manager<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> Stud Services<br />

2015 proved once again that a very definite<br />

line has been drawn between commercial,<br />

trophy and stud animals based on genetic<br />

potential. The future of game breeding<br />

lies in stud breeding and more emphasis<br />

is being placed on the quality of animals -<br />

as the species’ numbers increase so does<br />

the pressure on game ranchers to breed<br />

superior animals. Quality animals with<br />

DNA verified pedigrees and performance<br />

records maintained their value in the latter<br />

part of 2015 when the wildlife industry was<br />

under pressure. In September, WS 2 member<br />

Piet Warren proved this by hosting the most<br />

successful auction in the history of game<br />

ranching by selling 40 certified sable bulls<br />

for R137 000 000. He attributes his success<br />

to accurate measuring, record keeping and<br />

rigorously selecting accordingly.<br />

Reproduction and fertility are the first factors<br />

that should come to mind when thinking of<br />

breeding superior animals. The importance of<br />

reproduction is often masked by performance<br />

characteristics even though the economic<br />

and genetic value of an animal is determined<br />

by its ability to reproduce. WS 2 member,<br />

Amanzi Private Game Reserve, tagged a<br />

total of 46 sable calves in 2015; they also<br />

recorded a sable cow with an intercalving<br />

period of 9 months! Their selection process<br />

involves choosing the correct combination of<br />

parents from the current generation to make<br />

genetic progress in the next generation and<br />

on average, the offspring must outperform the<br />

parents. This is the foundation of excellent<br />

breeding practices. The time has passed<br />

where one can simply multiply animals in a<br />

camp and harvest those with potential based<br />

on luck.<br />

A number of stud livestock breeders have<br />

entered the wildlife stud breeding market<br />

(Piet Warren - Brahman, Dr. Anndri Garret<br />

– Brahman, Crous Brothers - Bonsmara,<br />

Hardus Steenkamp - Simbra, Paul Michau<br />

– Holstein & Bonsmara, Frans Stapelberg –<br />

Bonsmara, etc.). WS² expects that because<br />

these breeders register all their calves, send<br />

in regular measurements and performance<br />

records, and are experienced in scientific<br />

stud breeding (utilizing genetic tools, ICP,<br />

setting breeding goals, parentage, pedigrees,<br />

indexes, EBV’s, selection, etc.) they will have<br />

a major impact on the wildlife breeding<br />

industry, and will quickly become the<br />

“LEADERS OF THE PACK”.<br />

The partnership between <strong>Wildlife</strong> Stud<br />

Services and the SA Predator Association has<br />

also grown from strength to strength. Predator<br />

farmers have shown tremendous support and<br />

we have already registered the first lions with<br />

DNA proven pedigrees on the WS 2 system in<br />

an effort to breed lions that will improve the<br />

overall genetic diversity of the lion population<br />

in South Africa. It is exciting to see how the<br />

partnership contributes toward conservation<br />

of our predators. Genetic conservation<br />

involves conserving the maximum genetic<br />

8<br />

<strong>2016</strong><br />

Wildtelers Joernaal<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Breeders</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

<strong>Wildlife</strong> stud services<br />

diversity within a species or population<br />

which will thereby preserve the evolutionary<br />

potential as well as provide the basis for<br />

adaptability as environmental conditions<br />

change. It is important to be responsible<br />

stewards of the animals in our possession<br />

so a study will also be done to compare the<br />

genetic diversity of lions in private ownership<br />

to that of free-roaming lions in national parks.<br />

A special thanks to all the breeders that<br />

have joined <strong>Wildlife</strong> Stud Services and<br />

have registered their sable, buffalo and roan<br />

herds on our system. Individually, it would<br />

have taken farmers many years to build a<br />

databasis of +5000 animals with proven<br />

pedigrees, but by being part of a collective<br />

you are contributing to the development of<br />

the wildlife industry. Thanks to this, we now<br />

have sufficient data to do the first genetic<br />

analysis for buffalo, sable and possibly also<br />

roan antelope. The analysis will include<br />

among others: averages, selection indexes<br />

as well as estimated breeding values for<br />

economic important traits per individual<br />

animals and herds, and will be compared<br />

to the averages of the complete database for<br />

each species. This will benefit our breeders<br />

by (i) determining the genetic potential of<br />

their animals, (ii) benchmarking animals<br />

within a herd and on a national level, (iii)<br />

establishing correlations between traits (iv)<br />

calculating genetic variation, and (v) aiding<br />

with animal selections within the herd as<br />

well as when buying new animals. Once the<br />

first genetic analysis is completed, it will be<br />

repeated monthly to ensure that breeders get<br />

quicker feedback on the genetic potential of<br />

their animals and that new data is taken into<br />

account so that new members can also benefit<br />

from the system. Therefore, we encourage<br />

all game ranchers to join the <strong>Wildlife</strong> Stud<br />

Services system and register their animals to<br />

take part in this game breeding revolution.<br />

Remember, the more animals on the system<br />

with repeated measurements the more<br />

effective and accurate the system becomes,<br />

thus a win-win solution. Remember, your<br />

success is our success!<br />

Lastly, <strong>Wildlife</strong> Stud Services wants to thank<br />

the advertisers and authors of the <strong>2016</strong><br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Breeders</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> for making the<br />

second edition possible.<br />

WS 2<br />

Team<br />

Dr. Paul Lubout<br />

D.Sc. Agric. Animal Breeding<br />

Director and Genetic Advisor<br />

+27 71 642 5219 • paul@ws2.co.za<br />

Charné Buitendach<br />

M.Sc. Agric. Animal Science<br />

Technical Advisor<br />

+27 82 928 9387 • tech@ws2.co.za<br />

Jaqqui Clute<br />

Office Manager /<br />

SAPA Representative<br />

+27 72 313 9410 • admin@ws2.co.za<br />

Thunis Cocklin<br />

Namibia Representative<br />

+264 81 127 6791<br />

namibia@ws2.co.za<br />

9

10<br />

<strong>2016</strong><br />

Wildtelers Joernaal<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Breeders</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

<strong>Wildlife</strong> stud services<br />

11

<strong>Wildlife</strong> industry<br />

expected to continue to grow<br />

Ernst Janovsky completed his BSc. Agric Hon. degree in Agri-<br />

Economics of Livestock & Agronomy at the University of the Free State.<br />

He was Head of FNB Agriculture from 1997 to 2008 and is currently<br />

Head of ABSA AgriBusiness where he is responsible for the Agric Sector<br />

within ABSA (Absa Corporate and Business Bank) agricultural strategy,<br />

product development, risk management and financial reporting<br />

Market intelligent as well as Management information.<br />

083 230 1085 ernst.janovsky@absa.co.za www.absa.co.za<br />

The private wildlife industry is comprised of four main segments,<br />

namely: hunting, the breeding of game, wildlife tourism/ecotourism<br />

and game products. The private wildlife industry over the past two<br />

decades has grown tremendously, mainly due to the expansion in<br />

breeding and live sales of plain game species. So what does the future<br />

for the hunting and breeding segments entail?<br />

Hunting<br />

The importance of the hunting sector<br />

within the wildlife industry must not be<br />

underestimated, because it creates the<br />

demand for trophy breeding, contributes to<br />

wildlife tourism as hunters and their families<br />

normally visit wildlife parks and enhances<br />

the demand for wildlife products like<br />

venison. Hunting can therefore be seen as<br />

the backbone of the private wildlife industry<br />

in South Africa and is in principle the market<br />

from which all prices within the wildlife<br />

industry are derived. The hunting industry<br />

is where game is harvested and currently<br />

in South Africa the number of game bred<br />

by far exceeds the number of game hunted,<br />

which implies that the game numbers are<br />

still increasing. Given the limitations of our<br />

natural resources (veldt and bush) in the<br />

long run game breeding numbers need to be<br />

balanced with the number of game harvested<br />

through hunting or venison production.<br />

Before the later part of 2000 the majority of<br />

plains game was bred for hunting, with only<br />

a few animals being sold on the live market<br />

for non-consumptive breeding purposes. The<br />

main driving force for the recent growth in<br />

demand for hunting by international and<br />

local hunters has been the decline in game<br />

numbers internationally as well as the<br />

12<br />

<strong>2016</strong><br />

Wildtelers Joernaal<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Breeders</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

Economic forecast of the game industry<br />

weakening of the exchange rate, making<br />

South Africa more favourable as a hunting<br />

destination. Given the latest research in<br />

2014, approximately 8 950 international<br />

trophy hunters visited South Africa and on<br />

average each hunter spent R138 000 per visit.<br />

There are approximately 200 000 biltong<br />

hunters in South Africa spending on average<br />

R31 000 per annum on hunting. In South<br />

Africa the total turnover for the game hunting<br />

segment of the wildlife industry is therefore<br />

estimated to be R7,5 billion. This estimation<br />

does not include the indirect money spent<br />

on secondary industries like taxidermy, gun<br />

manufacturing and hunting accessories.<br />

The hunting industry is expected to expand<br />

even further as game numbers and hunting<br />

locations in South Africa continue to<br />

grow as a result of private ownership. This<br />

expansion is also supported by the decline<br />

in international hunting locations due to<br />

the dwindling international game numbers.<br />

The growth in the hunting industry has also<br />

been favourably impacted by the growth in<br />

the breeding of game, resulting in improved<br />

volumes, genetics and the availability of<br />

better trophy animals.<br />

The increase in demand for breeding animals<br />

and trophy animals has positively impacted<br />

the hunting prices of plains game. Over the<br />

past year the price of plains game increased<br />

by almost 12% in spite of a drought in certain<br />

areas that lead to an increase in supply as<br />

animals needed to be culled.<br />

Marketing of one’s enterprise as a hunting<br />

destination is however the trick to a successful<br />

enterprise. This will require an investment in<br />

marketing one’s self internationally as well as<br />

domestically because a good return business<br />

is based on a personal trust relation with the<br />

hunter. One can outsource marketing but<br />

this implies no relationship with the client<br />

and therefore no guaranteed return business.<br />

It is like wine marketing, one needs to build<br />

a brand which takes effort. This also implies<br />

an investment in facilities as well as specie<br />

diversification in order to deliver a one stop<br />

service.<br />

Game Breeding<br />

The breeding and sale of high value game<br />

and colour variants led to an approach of<br />

intensification of breeding systems which<br />

has in some instances led to the inefficient<br />

utilisation of the natural resource where<br />

the focus was on the breeding of only one<br />

species. The combination of species in a<br />

breeding program may lead to a more optimal<br />

utilization of the natural resources but needs<br />

to be well managed.<br />

Over the last two decades the game<br />

breeding sector only really got going with<br />

the developments and investment in game<br />

catching, game transporting and game<br />

auctioning facilities. Without this investment<br />

numerous ranchers did not even consider live<br />

sales as a marketing avenue for their game.<br />

Another contributing factor that unlocked the<br />

value of breeding stock was the development<br />

of a game insurance product that can be used<br />

as a risk management tool, especially during<br />

the stress periods such as during capturing<br />

and the adjusting period after the sale of the<br />

game.<br />

The potential negative impact of disease<br />

outbreaks, the high barriers to entry in terms<br />

of capital investment and lack of up to date<br />

information, remains the main weaknesses<br />

within the industry.<br />

In 2014 the total turnover on game auctions<br />

grew by 35% year on year to a historic high<br />

of R1,8 billion. Taking into consideration<br />

that only approximately 20% of game is sold<br />

at game auctions, the turnover of the game<br />

breeding segment of the wildlife industry is<br />

estimated to be R10 billion. This estimated<br />

turnover excludes revenues from secondary<br />

industries like fencing, feed manufacturing,<br />

pharmaceuticals etc.<br />

As previously mentioned the intrinsic value<br />

of breeding stock is for all practical reasons<br />

derived from the price where the animal is<br />

harvested. With cattle the breeding price<br />

for a cow and bull has inadvertently been<br />

determined by the price of slaughter cattle.<br />

For example the prices of the bull is basically<br />

the slaughter price of cattle multiplied by four<br />

13

(R10 000 x 4 = R40 000). This same principle can be used to determine game prices. A buffalo<br />

is for instance hunted for R50 000 to R60 000, which implies that breeding stock should trade<br />

at R200 000 to R240 000. Of course there will be outliers as with cattle where one would pay<br />

R100 000 for specific genetics or R1m for a specific Buffalo bull. If this principle is applied to<br />

all species, colour variants stand out to be trading far above their intrinsic value. It is therefore<br />

expected that the breeding value for colour variants will continue to decrease more severely<br />

than that of other plains game.<br />

Over the past months the prices on game auctions have however started to decline. This is<br />

mainly the result of increases in supply due to severe drought conditions. It could be argued<br />

that the market is getting saturated and that price will tend to soften. In spite of this, further<br />

expansions in the breeding of game can be expected, as the profitability of game breeding is<br />

much higher than that of cattle farming, especially in the scarce game species like Buffalo and<br />

Sable.<br />

To become a breeder is easy. You don’t even need to own land, as you can rent land. All<br />

it takes is a fence, a few females and a male, the question however is does it add value to<br />

diversification and the build of superior genetics. The barrier to enter in the breeding market<br />

is therefore fairly low and given current prices it is expected that more breeding farms will be<br />

established. There will also be a switch from hunting farms to breeding farms.<br />

The following graphs indicate what can be expected in terms of supply and price for the<br />

different groupings with in the game industry:<br />

14<br />

<strong>2016</strong><br />

Wildtelers Joernaal<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Breeders</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

<strong>Wildlife</strong> stud services<br />

15

Colin Engelbrecht<br />

Klein Buisfontein Ranch<br />

THE GOLDEN<br />

KING WILDEBEEST<br />

Colin<br />

Engelbrecht<br />

and his wife<br />

Marisa farm<br />

near the town of<br />

Hartbeesfontein in<br />

the Northwest Province.<br />

Under their management,<br />

the once marginal cattle<br />

farm has been transformed<br />

over the past 11 years into<br />

a successful game farming<br />

operation. During 2009 the first exotic<br />

game was introduced onto the farm.<br />

Presently there are 12 plains<br />

game species; 10 exotic game<br />

species and 10 predator species<br />

to be found on the ranch. Klein<br />

Buisfontein Ranch strives for<br />

breeding excellence through<br />

thorough research and the use of<br />

pure genetics which is the key to<br />

breeding excellence.<br />

083 306 0125<br />

colin@kleinbuisfonteinranch.co.za<br />

www.kleinbuisfontein.co.za<br />

16<br />

<strong>2016</strong><br />

Wildtelers Joernaal<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Breeders</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

eeding<br />

Introduction<br />

Wildebeest, also called gnus or wildebai, seem<br />

to have evolved around 2.5 million years ago and<br />

are a genus of antelopes Connochaetes. They belong<br />

to the family Bovidae, which includes antelopes, cattle,<br />

goats, sheep and other even-toed horned ungulates. They<br />

have lightly built hindquarters but are more robust at their<br />

shoulders and chest. Both sexes possess horns which are shaped<br />

like parentheses and resemble those of the female African Buffalo.<br />

The Golden King Wildebeest, also known as the Chocolate Wildebeest or<br />

Copper Wildebeest (Figure 1.1) originated naturally in the Southern parts of<br />

Botswana and Molopo areas of the North West Province.<br />

Figure 1.2: Crossbred King Wildebeest and Normal<br />

Golden Wildebeest<br />

Figure 1.3: Normal Golden Wildebeest with a large<br />

spot/mark on flank<br />

A Golden King Wildebeest is not a crossbred animal between a King Wildebeest and a<br />

normal Golden Wildebeest (Figure 1.2), as some might believe. Golden King Wildebeest<br />

are not normal Golden Wildebeest with a large mark or spot on their flanks, as is the<br />

beliefs of others (Figure 1.3). Golden King Wildebeest are a NATURAL BREED that<br />

breeds true to their traits.<br />

Description<br />

The Golden King Wildebeest (Figure 3) has similar characteristics to<br />

the King Wildebeest (Figure 2.1 and Figure 2.2). They differ in facial<br />

colour, but have similar body colour, with some animals having a<br />

large spot or mark on their flanks, as in the King.<br />

17

Figure 2.1: King Wildebeest without a spot/mark on<br />

flank<br />

Figure 2.2: King Wildebeest with spot/mark on flank<br />

Figure 3: Golden King Wildebeest with spot/mark on flank<br />

In general all adult animals are grey, tinged<br />

with chocolate brown especially on the<br />

rump. In certain light conditions, the animals<br />

appear to be gold or a reddish copper colour.<br />

There are a number of vertical stripes present<br />

on the neck. They have a gold/reddish copper<br />

mane which runs down the back of the neck<br />

and along the vertebrae (vertebral stripe)<br />

ending in the tail hair of a thick gold/reddish<br />

copper colour (Figure 4).<br />

The facial hair is a thick bush of gold/reddish<br />

copper hair, almost like a fringe, with the<br />

top area light gold between the horns and a<br />

chocolate reddish copper snout. The calves<br />

are born a fawn colour with a darker shade<br />

face. At approximately 2 months of age<br />

the offspring begin to take on their adult<br />

colouration (Figure 5.1 and Figure 5.2).<br />

Habitat<br />

Wildebeest prefer open grassland savanna<br />

and savanna woodland. Despite this they can<br />

survive in arid regions. Access to drinking<br />

water is essential. Animals can be bred<br />

successfully in smaller areas.<br />

18<br />

<strong>2016</strong><br />

Wildtelers Joernaal<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Breeders</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

<strong>Wildlife</strong> stud services<br />

19

Breeding<br />

Golden King Wildebeest can be successfully<br />

bred by pairing a Golden King bull with a<br />

Golden King cow/heifer. The offspring breed<br />

true to the parents in all aspects. Pairing a<br />

Golden King bull with a common or blue<br />

wildebeest cow/heifer will result in splits<br />

being bred. These Golden King split heifers<br />

can then be paired with a Golden King bull<br />

to reproduce Golden King offspring which<br />

are true to the breed (keep in mind the fifty<br />

percent rule).<br />

Reproduction<br />

Wildebeest are prolific breeders and the<br />

Golden King is no exception. Bulls reach<br />

sexual maturity at around twenty four months<br />

and heifers at around eighteen months. The<br />

mating season lasts for approximately three<br />

weeks and coincides with the end of the<br />

rainy season and typically begins on the<br />

night of a full moon. A single calf is born<br />

after a gestation period of about eight and a<br />

half months and between eighty and ninety<br />

percent of calves are born within a three<br />

week period. Calves weigh between eighteen<br />

and twenty two kilograms.<br />

Figure 5.1: Golden King Wildebeest with<br />

offspring<br />

Golden King Wildebeest cannot be<br />

successfully paired with a Golden Wildebeest.<br />

The offspring have the traits of the common<br />

or blue wildebeest. As a result of there being<br />

a small population of Golden King animals in<br />

breeders’ hands at present, pedigrees of these<br />

animals are fairly new, but will increase as<br />

more DNA tests of these animals become<br />

available. This will ensure that the animals<br />

are kept true to their traits.<br />

Figure 5.2: Golden King Calf<br />

Conclusion<br />

The Golden King Wildebeest is a hardy<br />

natural occurring animal which breeds true.<br />

It is not a crossbred animal and it is not a<br />

Golden Wildebeest. Once the numbers of<br />

these animals bred increases, so will the<br />

pedigrees and DNA databases be developed<br />

and expanded further.<br />

The <strong>Wildlife</strong> Stud Services system is based on an adapted version of the International Livestock<br />

Registry system (ILR2) for wildlife with a built in DNA parentage system and wildlife performance<br />

testing system (e.g. horn length, live weights, reproduction traits etc.). The system offers a database<br />

of DNA verified pedigrees to plan mating combination and manage the level of inbreeding. The<br />

“Mating Predictor” can be used to mate animals on paper. The system will calculate the level<br />

of inbreeding based on the DNA verified pedigrees as well as predict the genetic potential<br />

(estimated breeding values) for various performance (horn length, weaning weight) and fertility<br />

traits (scrotal circumference). EBV’s (Estimated Breeding Values) are calculated using the<br />

animals own measurements, measurements of relatives (based on DNA verified pedigree) and<br />

correlations between traits. Genetic tools such as “MateSel” en “GeneProb” can<br />

also be utilised once sufficient data is available to improve genetic gain (e.g.<br />

colours variants and increased horn length) and manage genetic diversity.<br />

20<br />

<strong>2016</strong><br />

Wildtelers Joernaal<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Breeders</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

eeding<br />

Farming with<br />

mini antelope<br />

- Arnaud le Roux & Silke Pfitzer<br />

Arnaud le Roux obtained his National Diplomas in Agriculture and Nature<br />

Conservation; a Higher National Diploma in Nature Conservation, and<br />

a Magister Technologiae: Nature Conservation. He has been farming<br />

with small antelopes for over 15 years near Bela-Bela, Limpopo. Le<br />

Roux is currently self-employed as an Ecology Consultant, developing<br />

environmentally compatible products on behalf of Agrochemical<br />

companies, and wildlife ranching developments. He has managed<br />

several projects on behalf of the Endangered <strong>Wildlife</strong> Trust and also has 13 years<br />

conservation and rangeland research experience in the department of Agriculture in the<br />

Limpopo Province, 7 years experience as national project manager in the Conservation<br />

and Rangeland division at Ecoguard Biosciences Pty Ltd. (DowAgro Sciences). Le Roux is<br />

also the <strong>Wildlife</strong> Management Consultant of Le Petit 5.<br />

082 325 6578<br />

arnaudleroux109@gmail.com<br />

Introduction<br />

Intensive wildlife production has increased<br />

dramatically over the last decade. This<br />

form of game farming has been accepted<br />

throughout the wildlife and conservation<br />

industry. Provincial authorities have adapted<br />

legislation to accommodate this form of game<br />

farming and central government has also put<br />

in place legislation to regulate the industry.<br />

The purpose of implementing this form of game<br />

farming can probably mostly be associated<br />

with economic reasons but the conservation<br />

and proliferation of certain threatened<br />

species have also been advocated. A number<br />

of species are being farmed, generally being<br />

those that have a high monetary value due to<br />

their scarcity. The main species being farmed<br />

in this way are sable antelope, nyala, roan<br />

antelope and buffalo.<br />

Game farming has become an integral part<br />

of the agricultural sector in South Africa. This<br />

has probably led to the present day method<br />

of breeding high profile game species under<br />

intensive management conditions.<br />

In many instances farmers have been<br />

instrumental in saving a number of our wildlife<br />

species. Examples include the bontebok,<br />

black wildebeest and Cape mountain zebra,<br />

each of which has in some or another way<br />

been bred to numbers that have saved them<br />

from possible extinction. Donations of<br />

animals by these forward-thinking farmers to<br />

National Parks and Provincial Reserves have<br />

contributed immensely to the conservation<br />

of these species (Young, 1992).<br />

The actions of farmers over the years have<br />

>> page 25<br />

21

22<br />

<strong>2016</strong><br />

Wildtelers Joernaal<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Breeders</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

<strong>Wildlife</strong> stud services<br />

23

24<br />

<strong>2016</strong><br />

Wildtelers Joernaal<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Breeders</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

eeding<br />

culminated in a new profitable form of<br />

land use: game farming. This activity on its<br />

own has shown that it can succeed and has<br />

been compared to a diamond, thus having<br />

many facets. Examples thereof are tourism,<br />

hunting, research and the production of byproducts<br />

such as biltong, venison and hides<br />

(Young, 1992).<br />

Through an evolutionary process, game<br />

farming has become more focussed in<br />

certain instances leading to intensive wildlife<br />

production. As wildlife production increases,<br />

more rare animals are entering the market,<br />

with major economic and conservation<br />

impact. In extensive production systems<br />

the growth rate of rare wildlife populations<br />

is often retarded. Recent realisation that<br />

such animals can be intensively produced<br />

economically and practicably feasible,<br />

provided new stimulus and input into wildlife<br />

production in southern Africa (Bothma & van<br />

Rooyen, 2006).<br />

There is a growing demand for a diversity<br />

of species in the <strong>Wildlife</strong> Ranching and<br />

Ecotourism Industry. The smaller antelope<br />

have, however, been neglected to date and<br />

their numbers have probably declined in<br />

several areas. Various reasons can be given<br />

for this, one of which is the fact that very<br />

few of these animals are made available to<br />

interested buyers and the breeding of these<br />

species has thus not been tried on and tested<br />

commercially. By now it has been proven by<br />

other species that the most reliable way of<br />

ensuring the future existence of any species<br />

lies in attempts to create a monetary value for<br />

each of them, which in turn should motivate<br />

farmers to breed them, thereby ensuring the<br />

distribution and natural increase in their<br />

population numbers.<br />

animals on land suitable for development<br />

can simply be removed and put into a<br />

captive breeding facility. This may ultimately<br />

work against the objectives of small antelope<br />

conservation, especially considering that<br />

the success of rehabilitation of captive bred<br />

animals into the wild has not been well tested.<br />

Captive breeding must therefore only be seen<br />

as a management tool to ultimately support<br />

the return of animals into natural habitat,<br />

and must not be seen as a conservation tool<br />

in isolation to conserving small antelope<br />

species in their natural habitats.<br />

Source animals are from (1) a population<br />

that is ‘doomed’ i.e. population is under<br />

imminent threat of extinction due to land use<br />

change or poaching, and where there are no<br />

options for natural movement of animals to<br />

contribute to a larger meta-population, (2) a<br />

population at or above maximum productivity<br />

carrying capacity (i.e. at or above 75% of<br />

ecological carrying capacity) or a level at<br />

which Provincial conservation agencies are<br />

prepared to grant a capture permit, or (3)<br />

animals that are injured or imprinted and are<br />

hence non-releasable.<br />

• The purpose is to ensure that there are no<br />

extra negative impacts on wild populations;<br />

it is undesirable to remove animals from<br />

wild populations where these populations<br />

are below carrying capacity, or where<br />

options exist to translocate animals to<br />

other areas of natural habitat.<br />

• In all cases status of populations (doomed<br />

populations, populations above maximum<br />

productivity carrying capacity, and nonreleasable<br />

animals) is to be assessed by an<br />

authorised representative.<br />

The main objective of the Small Game<br />

<strong>Breeders</strong> Association SA (SGBASA) is to<br />

promote the conservation of all the small<br />

antelopes in their natural habitats. One of the<br />

biggest threats to small antelope species is<br />

habitat loss and fragmentation. While captive<br />

breeding may contribute towards achieving<br />

the goals of the SGBASA, there is also a risk<br />

that providing captive breeding as an option<br />

will result in more land transformation and<br />

habitat loss based upon the perception that<br />

25

Table 1: The small antelope of Southern Africa<br />

AFRIKAANS ENGLISH LATIN<br />

Gewone duiker Common duiker Sylvicapra grimmia<br />

Rooiduiker Red duiker Cephalophus natalensis<br />

Blouduiker Blue duiker Cephalophus monticola<br />

Soenie Suni Neotragus moschatus<br />

Klipspringer Klipspringer Oreotragus oreotragus<br />

Steenbok Steenbok Raphicerus campestris<br />

Kaapse grysbok Cape grysbok Raphicerus melanotis<br />

Sharpe se grysbok Sharpe’s grysbok Raphicerus sharpei<br />

Oorbietjie Oribi Ourebia ourebi<br />

Damara dik-dik Damara dik-dik Madoqua kirkii<br />

Bosbok Bushbuck Tragelaphus scriptus<br />

Vaalribbok Grey rhebok Pelea capreolus<br />

Rooiribbok Mountain reedbuck Redunca fulvorufula<br />

Rietbok Reedbuck Redunca arundinum<br />

Three duiker species of South<br />

Africa:<br />

The grey or common duiker (Sylvicapra<br />

grimmia) is widely distributed south of the<br />

Sahara desert. It is very adaptable and can be<br />

found in most types of habitat. It is also often<br />

found close to human habitation and kraals<br />

where it scavenges on leftovers.<br />

Rams are usually smaller than females with a<br />

shoulder height of about 55cm and a mean<br />

bodyweight of about 17kg. Females reach a<br />

shoulder height of about 57cm and average<br />

body weight of 21kg.<br />

The red duiker (Cephalophus natalensis)<br />

belongs to the forest-associated species of<br />

duikers. It prefers riverine habitat but can<br />

also be found in savannah bushveld. The<br />

geographic distribution in South Africa is<br />

limited to the northern and south-eastern<br />

parts of KwaZulu-Natal, Swaziland and the<br />

Lowveld of Mpumalanga. There is also a<br />

population in the Soutpansberg in Limpopo<br />

Province. Red duiker males reach a shoulder<br />

height of 43cm and a body weight of 12kg,<br />

while ewes can be slightly bigger at 45cm<br />

shoulder height and 12 to 14kg body weight.<br />

The blue duiker (Philantomba monticola)<br />

also belongs to the forest-associated species<br />

of duikers. It prefers forests with a dense<br />

canopy in the high rainfall regions of Natal<br />

and along the coastal lowlands along the East<br />

coast of South Africa right into the Western<br />

Cape. It can also be found in the forests<br />

of Swaziland and further north in eastern<br />

Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Malawi.<br />

The blue duiker is the smallest antelope of<br />

southern Africa. Males have an average<br />

shoulder height of 34cm and an average<br />

body mass of 4,5kg, while ewes can stand<br />

1cm taller and have a mass of 5,5kg. The blue<br />

duiker has been classified as “Rare” and is<br />

protected by CITES regulations in terms of<br />

international trade. Blue duikers adapt well<br />

to captivity and there are several successful<br />

breeding projects throughout the country.<br />

For further description of the species and their<br />

habitat, please refer to suitable texts such<br />

as “The Mammals of the Southern African<br />

Subregion” by Skinner and Smithers (1990).<br />

Capture<br />

Capture in the wild is best carried out with<br />

dropnets and beaters. For oribi (Ourebia<br />

ourebi) in grassland habitat, a helicopter<br />

can be used instead of beaters. For mini<br />

26<br />

<strong>2016</strong><br />

Wildtelers Joernaal<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Breeders</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

eeding<br />

antelope the size of red duiker and bigger,<br />

the mesh size should be 100m x 100mm. For<br />

blue duiker the mesh size should be smaller<br />

(50mm x 50mm).<br />

Passive capture is possible where feeding<br />

stations or water holes on a small property<br />

exist. However, since most duiker species<br />

and also most other mini antelope are<br />

territorial or live in small family groups, only<br />

small numbers will be captured at a time.<br />

Capture by darting, especially in forest habitat,<br />

brings with it difficulties of recovering the<br />

animals. Transmitter darts at this stage are still<br />

very heavy and could lead to severe muscle<br />

damage if fired into the small leg muscles<br />

of a mini antelope. Oribi and steenbok<br />

(Raphicerus campestris) in grassland habitat<br />

have been darted successfully at night with a<br />

spotlight and with reflective tape attached to<br />

the dart. Klipspringer (Oreotragus oreotragus)<br />

has been successfully darted on the rocky<br />

outcrops from a helicopter.<br />

A blowpipe or gas charged dart gun and<br />

very light darts are the safest option for small<br />

antelope such as blue and red duiker. So far<br />

one of the best systems in captivity for these<br />

species seems to be the light Telinject darts<br />

for the Telinject blowpipe. The needles are<br />

very small and bend over or break before<br />

causing any severe injury such as bone<br />

fractures. These darts can be combined with<br />

the tail piece of a Dan-Inject dart and shot<br />

through the Dan-Inject dart gun – provided<br />

the barrel is never held down because this<br />

dart would fall out. The drawback is that the<br />

darts do not inject reliably and the distance<br />

is rather short (10 – 15m). However, half<br />

of a full dose is often good enough to get<br />

hold of mini antelope in captivity for further<br />

handling. The small Pneu-Darts or Dan-Inject<br />

darts can be used for the larger sized mini<br />

antelopes. Needles should always be as short<br />

as possible.<br />

Care should be taken that family groups such<br />

as those in klipspringer and oribi populations<br />

as well as pairs in the steenbok population<br />

stay together.<br />

Drug combinations and dosages<br />

Dosages given below are for adult animals,<br />

unless specified.<br />

A3080 works very well for most species of<br />

mini antelope. A dose of 0,5mg A3080 is<br />

sufficient for blue duiker. Red duiker can<br />

be safely darted with 1 - 1,5mg A3080<br />

combined with 10 – 20mg of Azaperone,<br />

while up to 2mg A3080 can be used for grey<br />

duiker. Steenbok can be darted with 0,5mg<br />

A3080 and oribi with up to 1mg A3080 or<br />

a combination of 0,5mg A3080 and 0,5mg<br />

M99.<br />

Zoletil has also been successfully used to<br />

dart mini antelope – especially if painful<br />

procedures such as small operations need<br />

to be performed and gas anaesthetic is not<br />

available. About 100 to 200mg of Zoletil<br />

provides good anaesthesia in red duiker and<br />

grey duiker.<br />

Haloperidol and perphenazine enanthate<br />

are commonly used as tranquillizers in<br />

mini antelope either on their own or in<br />

combination. Haloperidol can be used at a<br />

dosage rate 4 – 6mg for blue duiker, up to<br />

10mg for red duiker and grey duiker, 10mg for<br />

oribi and 5mg for steenbok. For klipspringer,<br />

2mg of haloperidol and 10mg of azaperone<br />

have been used with good success.<br />

Perphenazine can be used at a dosage rate<br />

of 30mg for blue duiker as well as steenbok<br />

and up to 50mg for red duiker, grey duiker<br />

and oribi.<br />

Crates<br />

Wooden crates with a height x width x<br />

length of 80cm x 35cm x 1m can be used<br />

for mini antelope from the size of red duiker<br />

up to oribi. Crates have to be dark to prevent<br />

jumping and air vents can be covered with<br />

a blanket until tranquillizers take effect after<br />

net capture. Blue duiker crates should be<br />

a bit smaller and even apple boxes have<br />

successfully been used to transport captive<br />

bred blue duiker.<br />

If mini antelope are captured from a boma<br />

and loaded directly into a crate, the crate<br />

should have windows through which the<br />

animal can be injected with tranquillizers.<br />

Wild captured mini antelope should always<br />

be transported in individual crates; however,<br />

bigger wooden boxes have successfully been<br />

used as “mass crates”. The grouping of newly<br />

caught animals in existing family groups<br />

27

settles the animals down easier. A low crate<br />

height will help in preventing the animals<br />

from jumping. Males should have PVC pipes<br />

on their horns of appropriate length and<br />

diameter.<br />

Injured duiker and steenbok can be kept in<br />

a large box with access from the top – this<br />

has been successful in keeping and treating<br />

injured animals for several weeks.<br />

Bomas and camps for mini antelope<br />

A conventional boma of about 8m x 8m<br />

with walls of 3m in height, constructed out<br />

of wooden slats has been successfully used<br />

to house grey duiker, oribi and steenbok. Of<br />

importance is a dark roofed section with a<br />

dividing wall, behind which the animals can<br />

hide. For keeping oribi and steenbok, the<br />

addition of little houses made out of bundles<br />

of thatch grass mimic their natural habitat<br />

and also help to provide hiding place to keep<br />

these animals calm.<br />

It is important that any vertical gaps, for<br />

example around doors, are small or covered<br />

by sheeting so that the antelope cannot trap or<br />

injure their feet or hooves if they start jumping.<br />

Steenbok especially try to creep underneath<br />

walls and doors and can trap themselves, so<br />

these gaps should also be covered or small<br />

enough not to tempt an animal. Klipspringer<br />

will use any opportunity to climb or jump up<br />

boma walls and therefore their boma should<br />

be completely covered over at the top with<br />

sheeting, netting or shade cloth, otherwise<br />

they will escape.<br />

Grey duiker and oribi can be kept in groups<br />

as long as only one mature ram is present per<br />

compartment. Oribi are best kept in family<br />

groups, particularly if captured as such in the<br />

veld.<br />

Steenbok should be kept in habituated pairs<br />

or singly.<br />

Wild captured red duiker is extremely<br />

excitable, more so than other mini antelope<br />

species, and will frequently jump against<br />

the sides of bomas if stressed. They are thus<br />

difficult to keep in conventional bomas but<br />

can be held in big dark boxes (2 - 3m long,<br />

1m high and 1m wide) for several weeks.<br />

These “box bomas” should not have any sharp<br />

edges and be divided into two compartments<br />

so that the animals can be cleaned and fed.<br />

Only one animal should be kept per box. As<br />

red duiker tend to produce a lot of faeces<br />

and urine, a thick layer of bedding (e.g. hay)<br />

is necessary. Drainage holes in the floor are<br />

required for urine and spilled water.<br />

Blue duiker is also a forest species, and will<br />

jump in a conventional boma similar to the<br />

behaviour of red duiker, but not to the same<br />

extent. A box system can also be used in this<br />

species.<br />

For recapture, mini antelope in a box boma<br />

can be run directly into their transport crate.<br />

Grey duiker also could be loaded by running<br />

them down a passage and directly into a row<br />

of crates that was made attractive by hanging<br />

some leaved branches behind which they<br />

can hide.<br />

Oribi and steenbok are best darted for<br />

loading.<br />

Captive breeding of mini antelope<br />

Camps for captive breeding should have<br />

a visible boundary as most mini antelope,<br />

especially duiker, are skittish on release and<br />

tend to run into fences and walls. The fence<br />

should be about 1,8m high and the mesh size<br />

of the fence has to be suitable for the species<br />

that the camp should hold and small enough<br />

to also keep in the neonates and sub adults.<br />

Welded mesh with a small mesh size works<br />

very well for this purpose. An overhang to<br />

the inside helps to prevent escapes. Camps<br />

should if possible resemble the natural<br />

environment and have lots of hiding places.<br />

Corners should be rounded and not present<br />

an opportunity for escape. A-frame houses<br />

are accepted by most species and give good<br />

protection from weather as well as from<br />

raptors. Snakes, such as pythons and black<br />

mambas can become a problem in a captive<br />

breeding operation, as they are attracted to<br />

the mice and rats that often are associated<br />

with the feed offered to the antelope. The<br />

camps should thus be inspected for snakes<br />

regularly and vermin should be controlled.<br />

The fence should be constructed in such a<br />

way that no predator can enter the camp.<br />

Feed and water should be offered under a<br />

roof and this structure could potentially also<br />

28<br />

<strong>2016</strong><br />

Wildtelers Joernaal<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Breeders</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

<strong>Wildlife</strong> stud services<br />

29

e used to capture the animals if necessary.<br />

Camp sizes vary. The use of small camps<br />

for blue duiker can result in good breeding<br />

success - they can be kept in camps as small<br />

as 5m x 5m, and should be kept in pairs.<br />

Other mini antelope need more space. A 30m<br />

x 30m camp (or bigger) with many hiding<br />

places works well for breeding red duiker.<br />

One ram can be kept with 1-2 females but<br />

rams should never be mixed as they might<br />

fight to death. For grey duiker and steenbok, a<br />

camp of 30m x 30m should also be sufficient<br />

for 2 - 3 animals. Adult rams should never<br />

be held together and it is recommended that<br />

steenbok should be kept in pairs only. The<br />

camps for oribi should be a bit larger and<br />

one male can be kept together with several<br />

females. The offspring, especially male<br />

offspring, have to be monitored closely and<br />

will have to be removed at the first sign of<br />

aggression by the adult ram.<br />

When planning and constructing a camp,<br />

consideration must be given to management<br />

functions within that camp. Hiding places,<br />

feeding areas water troughs / dishes must be<br />

catered for, as well as methods of re-capture<br />

out of the camp. It is not easy to dart a semi<br />

wild red or grey duiker in a camp of 50m x<br />

50m, so night rooms or boxes that the animals<br />

can be trapped in and caught by hand must<br />

be provided.<br />

Feeding of mini antelopes:<br />

Most mini antelopes are concentrate<br />

selectors. Their diet is thus low in fibre and<br />

is digested quickly. They are very selective<br />

in what they forage on. Steenbok and grey<br />

duiker preferentially select herbs, forbs and<br />

certain plant parts such as the tips or flowers,<br />

while the forest duiker species are mostly<br />

frugivores - their diet contains a lot of wild<br />

fruits, which is often dropped by monkeys<br />

and birds. Oribi seem to depend mainly on<br />

different grass species.<br />

This makes it difficult to find the ideal feed<br />

for mini antelope in captivity. Most modern<br />

literature emphasizes that natural browse is<br />

very important in captivity. Natural browse<br />

is usually the preferred food item that is<br />

taken shortly after capture. The 2 species of<br />

browse that are most readily accepted by<br />

most species that require browse is buffalothorn<br />

(Ziziphus mucronata) and red ivory<br />

(Berchemia zeyheri). However, this might<br />

vary from area to area and it is best to offer a<br />

variety of browse at first to determine which is<br />

accepted. The thorns of the buffalo thorn can<br />

be a problem in the box boma and animals<br />

can get hooked up in them.<br />

In addition, good quality antelope pellets,<br />

A-grade Lucerne hay and a mix of cut-up fruit<br />

and vegetables such as carrots, butternut,<br />

broccoli, spinach and apples should be<br />

offered to mini antelope. If wild fruits such<br />

as marulas, berries and figs are available,<br />

these can also be offered. Fresh water should<br />

always be available even if the animals are<br />

not classed as “water dependant”.<br />

Special anatomic features and<br />

diseases:<br />

The red duiker seems very susceptible to<br />

pneumonia and should not be translocated<br />

during the winter months. If held in<br />

colder climates, an isolated shelter has<br />

to be provided. Crotalaria poisoning has<br />

been reported in grey duiker and lead to<br />

complications such as laminitis, deformed<br />

and overgrown hooves. The natural diet of<br />

duikers can contain a high tannin content<br />

but tannin seems to be very well tolerated by<br />

duiker.<br />

In one case with a red duiker female,<br />

Tumbu fly-like (Cordylobia anthropophaga)<br />

maggots could be found in the tail area on<br />

several occasions. The animal was treated<br />

successfully by removing the maggots, and<br />

disinfecting the wound. In addition, long<br />

acting penicillin and Dectomax ® were<br />

injected. Stress related jaw abscesses have<br />

also been reported in different duiker species,<br />

particularly if too many animals were held<br />

together in one enclosure. These were treated<br />

successfully with antibiotics.<br />

Willette et al. (2002) report a rumen<br />

hypomotility syndrome in several species<br />

of small duiker in captivity. A “sloshing”<br />

sound occurs when the animals make<br />

sudden movements and is possibly cause<br />

by fluid and gas build up in the rumen<br />

due to reduced motility. A change of the<br />

hair coat has been observed in some of the<br />

30<br />

<strong>2016</strong><br />

Wildtelers Joernaal<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Breeders</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

eeding<br />

affected individuals. The hair became lighter<br />

in colour. In addition, the faeces which<br />

normally are pelleted looked clumped and<br />

“dog like”. This condition can be chronic but<br />

it can also eventually lead to death if the gas<br />

build up in the rumen becomes too severe.<br />

Abnormalities reported in blood included a<br />

mild hypocalcaemia, hyperphosphataemia<br />

and hyperglobulinaemia. Serum copper<br />

also was low. This condition could be<br />

prevented by providing more natural<br />

browse and vegetables together with copper<br />

supplementation.<br />

Female blue and red duikers commonly have<br />

horns, which usually are a bit smaller than<br />

the horns of males. This can also be found<br />

regionally in up to 12% of grey duiker where<br />

the females might have short horns. Duikers,<br />

steenbok and oribi have interdigital or pedal<br />

scent glands. These can become infected if<br />

animals are held in a muddy environment.<br />

Duiker, steenbok and oribi have pre-orbital<br />

glands as well. Most mini antelope have<br />

inguinal glands apart from blue and red<br />

duiker.<br />

Gestation Periods<br />

While oribi seem to be seasonal breeders,<br />

lambing during summer, duiker and steenbok<br />

are non-seasonal breeders. Gestation periods<br />

for grey, red duiker and blue duiker are<br />

reported to be around 200 days. The gestation<br />

period for steenbok has been reported to be<br />

around 165 – 175 days, and about 210 days<br />

for oribi.<br />

Grey duiker and red duiker have successfully<br />

mated on several occasions and at least<br />

one male offspring grew up to adulthood.<br />

Whether this male hybrid was fertile is not<br />

known.<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> Ranching SA – Small Game<br />

<strong>Breeders</strong> Association:<br />

Vision:<br />

We strive to provide insightful industry<br />

guidance and inspiration on the most effective<br />

management practices of small antelope<br />

numbers towards sustainable population<br />

levels in southern Africa and thus ensuring<br />

their survival by optimal habitat management<br />

and utilization of natural resources.<br />

Mission:<br />

The Small Game <strong>Breeders</strong> Association<br />

SA strives to promote the development,<br />

sustainability and profitability of commercial<br />

small antelope breeding in southern Africa<br />

through involvement and discerning input on<br />

the conservation, breeding and utilization,<br />

translocation, marketing communication,<br />

policy revision and formulation.<br />

Literature of interest<br />

Bailey, T.A., Baker, C.A., Nicholls, P.K. & Wilson, V.J.<br />

1995. Blood Values for captive grey duiker and blue<br />

duiker. <strong>Journal</strong> of Zoo and <strong>Wildlife</strong> Medicine 26(3):<br />

387-391.<br />

Barnes, R., Greene, K., Holland, J. & Lamm, M. 2002.<br />

Management and Husbandry of Duikers at the Los<br />

Angeles Zoo. Zoo Biology 21: 107-121.<br />

Bowman, V. & Plowman, A. 2002. Captive Duiker<br />

Management at the Duiker and Mini-Antelope<br />

Breeding and Research Institute (Dambari), Bulawayo,<br />

Zimbabwe. Zoo Biology 21: 161-170.<br />

Dierenfeld E.S., Mueller, P.J. & Hall, M.B. 2002.<br />

Duikers: Native Food Composition, Micronutrient<br />

Assessment and Implications for Improving Captive<br />

Diets. Zoo Biology 21: 185-196.<br />

Estes, R.D.1991. The Behaviour Guide to African<br />

Mammals. Russel Friedman Books, South Africa.<br />

Farst, D.D., Thompson, D.P., Stones, G.A., Burchfield,<br />

P.M. & Hughes, M.L. 1980. Maintenance and<br />

breeding of duikers at Gladys Porter Zoo, Brownsville.<br />

International Zoo Yearbook 20: 93-99.<br />

Furstenburg D. 1997. Common Duiker. SA Game and<br />

Hunt Jul-Sept: 6-7.<br />

Furstenburg D. 2000. Blouduiker. SA Game and Hunt<br />

Feb: 6-7.<br />

Furstenburg, D. 2005. The Steenbok. In: Intensive<br />

wildlife production in southern Africa. Ed: J. du P.<br />

Bothma & N. van Rooyen, Van Schaik Publishers,<br />

Pretoria.<br />

Jooste R. 1984. Internal parasites of wildlife in<br />

Zimbabwe: Blue Duiker. Zimbabwe Veterinary <strong>Journal</strong><br />

15: 32.<br />

Pfitzer, S. & Colenbrander, I.A. 2005. The duikers. In:<br />

Intensive wildlife production in southern Africa. Ed: J.<br />

du P. Bothma & N. van Rooyen, Van Schaik Publishers,<br />

Pretoria.<br />

Shipley, L.A. & Felicetti, L. 2002. Fibre Digestibility and<br />

Nitrogen Requirements of Blue Duikers. Zoo Biology<br />

21: 123-134.<br />

Skinner, J.D. & Smithers R.H.N. 1990. The Mammals of<br />

the Southern African Subregion. University of Pretoria.<br />

Willette, M.M., Norton, T.L., Miller, C. L. & Lamm,<br />

M.G. 2002 Veterinary Concerns of Captive Duikers.<br />

Zoo Biology 21: 197-207.<br />

Wilson, V.J. 2001. Duikers of Africa. Chipangali<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> Trust, Bulawayo.<br />

31

Photo: Terry Herholdt<br />

The History of the<br />

Livingstone Eland<br />

i n S o u t h A f r i c a<br />

- Terry Herholdt<br />

Livingstone Estate<br />

32<br />

<strong>2016</strong><br />

Wildtelers Joernaal<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Breeders</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

eeding<br />

Terry Herholdt has been involved with the successful Stud Breeding<br />

of Brahman cattle since 1982 and has provided export quality cattle<br />

to neighbouring countries since 1987. Since 2003, she has worked<br />

under the auspices of SA Stud Book and built the only registered<br />

herd of Charbray cattle in South Africa from base animals to SP (fully<br />

registered stud) in 2015. She was invited to join the Australian Charbray<br />

Cattle Society in 2013. Terry’s other great passion lies in the research<br />

and breeding of Livingstone Eland, which she has been recording<br />

since the first imports arrived at Livingstone Estate in 1994. Her bloodlines are to be found<br />

in many of the current Livingstone Eland herds in South Africa. Comprehensive record<br />

keeping and DNA samples from the original, imported eland have enabled her to provide<br />

proper stud pedigrees and calving records for this unique Livingstone herd.<br />

082 494 4588<br />

terryherholdt@tiscali.co.za<br />

During the years 1993 - 1995, Livingstone<br />

Eland were re-introduced to South Africa by,<br />

amongst others, Boetie Visser, Clem Coetzee,<br />

Vivian Bristow, Kester Vickery and Dr Johan<br />

Kriek. Up until then, the Cape Eland, a sub<br />

species of the Southern African Common<br />

Eland (Taurotragus Oryx), had been the<br />

only Eland seen in National Parks and on<br />

farms, but they were not suited to the harsh<br />

Bushveld regions. Heavy tick infestations by<br />

hard bodied ticks, led to the loss of ears and<br />

teats, and newborn calves died as a result of<br />

starvation soon after birth. Named after the<br />

region where they originally flourished, Cape<br />

Eland were far better suited to the regions<br />

south of the Drakensberg. Bushman paintings<br />

found in caves in the Drakensberg mountain<br />

range, dating back to the Pleistocene era (70<br />

000 - 100 000 years ago), depict Eland with<br />

different coloured coats. One could argue<br />

that these tiny people were using their artistic<br />

ability to create these different colours, but<br />

what is of great significance, is the fact that<br />

some of the red Eland in this rock art, have<br />

very clear white stripes and black markings<br />

behind their front legs. The San could not<br />

have painted something which they had<br />

never seen! This means that the ‘Livingstone<br />

Eland’ (Taurotragus oryx livingstonii), must<br />

have grazed right up to the foot of the<br />

Drakensberg, but due to climate change and<br />

habitat destruction, they eventually migrated<br />

northwards.<br />

These conclusions were noted during the<br />

Danish research by Lorenzen et al., <strong>Journal</strong><br />

of Biogeography 37: 571-581 (2010). Eline<br />

Lorenzen and her team studied the genetic<br />

diversity and movement of African Eland due<br />

to past climate change, whilst researching her<br />

PhD thesis (Population Genetics of African<br />

Ungulates) at the University of Copenhagen.<br />

During the warmer interglacials, simulations<br />

indicate the presence of dense tropical forest<br />

extending from coast to coast across central<br />

Africa. Despite a broad habitat tolerance, the<br />

common Eland avoids dense forest (Estes,<br />

1992) and the presence of a continent-wide<br />

forest would pose a considerable barrier to<br />

gene flow between populations in East and<br />

Southern Africa (Cowling et al., 2008). The<br />

nucleotide distances among the mtDNA<br />

lineages observed in the common Eland<br />

indicate long periods of isolation between<br />

East and South. The southern mitochondrial<br />

lineage in the common Eland coalesced<br />

earlier than the eastern lineage, suggesting<br />

the presence of a longer standing population<br />

in the south. She went on to say, “Common<br />

Eland males have far smaller home ranges<br />

than those of females (Hillman, 1988) and<br />

we predict a corresponding split between<br />

east and south in nuclear genetic markers<br />

reflecting the evolutionary history of both<br />

sexes. The IUCN does not recognize<br />

any subspecies with the common Eland;<br />

33

however, we interpret the marked divide<br />

between mtDNA lineages in East and<br />

southern Africa as indicating independent<br />

evolutionary trajectories in the two regions,<br />

which we argue should be considered in<br />

future management efforts.<br />

Some of the most beautiful Livingstone<br />

Eland were found in the Nuanetse region<br />

of Zimbabwe, on the Nuanetse Ranch<br />

belonging to Brian Kaywood. These<br />

Eland were of the first to be captured and<br />

brought to South Africa. Whilst they were<br />

in quarantine, a group of 20 heifers and<br />

3 bulls were selected and relocated to<br />

Livingstone Estate in Dwaalboom, west of<br />

Thabazimbi, in the Limpopo Province. The<br />

remainder of that Boetie Visser herd were<br />

taken to Ellisras (Lephalale) and both herds<br />

were intensively managed like stud cattle by<br />

Terry Herholdt and the late Machiel Erasmus.<br />

They adapted so well that another three<br />

groups of Livingstone Eland were introduced<br />

to the Herholdt herd at Dwaalboom, after<br />

standing in quarantine. Two of the groups<br />

were from the Mashatu Reserve in Botswana,<br />

and by introducing them, genetic diversity<br />

was ensured. During 2005 – 2008, the<br />

Dwaalboom herd was dispersed and only<br />

a small group were kept on at Livingstone<br />

Estate. These Livingstones were handled<br />

daily and records were kept of calving dates,<br />

paternity and mortality. In April 2012, DNA<br />

samples were taken and sent to Prof Bettine<br />

van Vuuren at the University of Johannesburg<br />

to try and establish whether there was a<br />

separate genetic signature for the Livingstone<br />

Eland from Nuanetse, in conjunction with the<br />

Danish research of Lorenzen et al., referring<br />

to the 3 Intermediate Eland tested at Nuanetse<br />

Ranch. Even though pure Nuanetse genetics<br />