Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

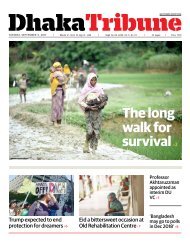

DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, <strong>September</strong> 7, <strong>2017</strong><br />

“But instead of crossing over you lie dreaming/<br />

of the woman, and the border:/ perfect knife<br />

that slices through the earth/ without the earth’s<br />

knowing”<br />

<br />

Border, Kaiser Haq

Tribute<br />

Before going to the saloon<br />

August 28 marked the poet’s first death anniversary<br />

Editor<br />

Zafar Sobhan<br />

Editor<br />

<strong>Arts</strong> & <strong>Letters</strong><br />

Rifat Munim<br />

Design<br />

Mahbub Alam<br />

Alamgir Hossain<br />

Shahadat Hossain<br />

Cover<br />

Syed Rashad Imam<br />

Tanmoy<br />

Illustration<br />

Syed Rashad Imam<br />

Tanmoy<br />

Priyo<br />

Colour Specialist<br />

Shekhar Mondal<br />

Shaheed Quaderi<br />

(Translated by Shawkat Hussain)<br />

My hungry hair flies wildly in the air<br />

Not easily tamed.<br />

Many times, many times,<br />

Have I tried to feed it well<br />

And put it to sleep. “The monster is coming…sleep my baby,”<br />

But nothing works.<br />

My hair stands sleepless<br />

Like a santal sardar with his lean muscular body, unclad;<br />

Or like some motionless, unblinking rebel<br />

Unbent by storms or bowed down by the rain,<br />

He stands for ages, for ages.<br />

This mad, black horse<br />

Terrifies everyone, threatens to disrupt<br />

Afternoon traffic, injure friends and relatives.<br />

Everybody says the same thing,<br />

“It’s grown too long, cut it down to size,”<br />

It’s grown too long, past the ears,<br />

Down to the shoulders.<br />

There’s nothing to do.<br />

It’s my hair, but not within my control.<br />

It grows on its own, moves and scatters,<br />

Flies like a rasping crow,<br />

Invades someone else’s sky<br />

Like its own, uses it with reckless abandon.<br />

My hair is like some truant schoolboy’s<br />

Covered with dust from head to foot,<br />

Obsessed with the dream of possessing a football;<br />

It is like some maverick player<br />

Dominating the field<br />

Like a stubborn monarch,<br />

Heedless of the referee’s whistle.<br />

So this is my hair, my ruffled, unruly hair,<br />

Somehow sticking to my perplexed skull.<br />

Suddenly, like a traffic signal,<br />

My wild, disorderly hair will be tamed<br />

When the barber’s firm, active scissors<br />

Snip them off—And so I would go to the best saloons,<br />

To discipline my hair.<br />

The arrogance of my hair<br />

Is not acceptable to members of civilized society,<br />

It has to be cut, shortened.<br />

My head has to be like ten other heads,<br />

Like ten other heads in society,<br />

And so it must be cut down,<br />

Trimmed and flattened, silenced over my skull,<br />

It must lie quietly plastered over my head<br />

Like a cold mat.<br />

Still, it is my hair!<br />

Blind, silent, and deaf,<br />

It springs up again<br />

Like an injured horse<br />

Even before the month is past.<br />

Shawkat Hussain is a writer and translator.<br />

to this squalid frontier town:<br />

a one-legged rickshahwallah takes round<br />

to a six-by-eight room, the best in the best hotel.<br />

But instead of crossing over you lie dreaming<br />

of the woman, and the border:<br />

perfect knife that slices through the earth<br />

without the earth’s knowing,<br />

severs and joins at the same instant,<br />

runs inconspicuously through modest households,<br />

creating wry humour – whole families<br />

cat under one flag, shit under another,<br />

humming a different national tune.<br />

The border<br />

Kaisr Haq<br />

You lie down on the fateful line<br />

under a livid moon. You<br />

and your desire and the border are now one.<br />

Let us say you dream of a woman,<br />

and because she isn’t anywhere around,<br />

imagine her across the border.<br />

You raise the universal flag<br />

of flaglessness. Amidst bird anthems<br />

dawn explodes in a lusty salute.<br />

You travel hunched and twisted in a crowded bus,<br />

on a ferry through opaque night<br />

lacerated by searchlights,<br />

[From Published in the Streets of Dhaka, published by University Press<br />

Limited. Reprinted with permission. An enlarged edition of the book will<br />

be launched at this year’s Dhaka Lit Fest.]<br />

2<br />

ARTS & LETTERS DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, <strong>September</strong> 7, <strong>2017</strong>

Tribute<br />

India’s Jewish general and the<br />

liberation of Bangladesh<br />

• Bernard-Henri Lévy<br />

It’s quite a story.<br />

This story may seem unlikely in<br />

this era of generalised war between<br />

cultures, civilisations, and religions.<br />

And I am grateful to British journalist<br />

Ben Judah for having brought it to<br />

light in an article that appeared in<br />

the Jewish Chronicle the day after the<br />

visit to Israel of Indian Prime Minister<br />

Narendra Modi.<br />

The time is December 1971.<br />

The place is the territory then<br />

known as East Pakistan.<br />

Separated by 1,600 kilometres<br />

from West Pakistan, this Bengali part<br />

of Pakistan has been in rebellion<br />

since March.<br />

The central government in<br />

Islamabad, rejecting the secession<br />

of what will eventually become<br />

Bangladesh, is engaged in a merciless<br />

repression, the cost of which, in lives, remains unknown even today, almost<br />

a half-century later. Half a million people may have died, or perhaps a million<br />

or two, or more.<br />

On December 3, India decides to enter the conflict, to “interfere,” as one<br />

would put it today, in the domestic affairs of its neighbour so as to stop the<br />

bloodbath.<br />

The fighting rages.<br />

The Bengali freedom fighters, known as the Mukti Bahini, now supported<br />

by India, become increasingly daring.<br />

New Delhi’s strategy is to build up slowly and gradually, a decision. This<br />

strategy seems to many ill-suited to the Bangladesh of the day, a terrain of<br />

few roads, major rivers, and innumerable marshes. Thirteen days into the new<br />

phase of the war, with the Pakistanis having massed 90,000 troops around<br />

Dhaka, the capital, against the Indians’ 3,000,New Delhiappears to be stuck<br />

and has hardly boxed itself into the beginnings of a siege. And it is at this<br />

moment that a high-ranking Indian officer, without notifying his superiors,<br />

takes a plane, lands in Dhaka, presents himself to General Niazi, head of the<br />

Pakistani forces and pulls off one of the most spectacular bluffs in modern<br />

military history: “You have 90,000 men,” the Indian officer tells Niazi. “We<br />

have many more, plus the Mukti Bahini, who are full angry with the loss of<br />

their people and will give no quarter. Under the circumstances, you have<br />

only one choice: To persist in a fight that you cannot win or to sign this letter<br />

of surrender that I have drafted in my own hand, which promises you an<br />

honourable retreat. You have half an hour to decide; I’ll go have a smoke.”<br />

Niazi, falling into the trap, chooses the second option.<br />

To the world’s amazement, three thousand Indian soldiers accept the<br />

surrender of 90,000 Pakistanis.<br />

Tens of thousands—no—hundreds of thousands of lives on both sides are<br />

spared.<br />

And Bangladesh is free!<br />

The story might have ended there.<br />

Except that the general behind the masterly coup that makes him godfather<br />

to a new Muslim country is Jewish.<br />

His name is Jack Jacobs.<br />

He was born in 1924 in Calcutta into a Sephardic family that had arrived<br />

there from Baghdad two centuries<br />

before, leaving behind two<br />

thousand years of history.<br />

In 1942, learning of the ongoing<br />

extermination of Europe’s Jews,<br />

he enlists in the British army in<br />

Iraq, fights in North Africa and<br />

then moves on to Burma and<br />

Sumatra in the c<strong>amp</strong>aign against<br />

the Japanese.<br />

And remaining in the military<br />

after the independence of India in<br />

1947, he is the only Jew to rise high<br />

in the country’s military services,<br />

eventually coming to command<br />

the eastern army that, in<br />

December 1971, will be mounting<br />

the offensive against Islamabad’s<br />

legions.<br />

It so happened that I met this<br />

man 46 years ago.<br />

I was in rebellious Bangladesh,<br />

having responded to French<br />

novelist André Malraux’s call for the formation of an International Brigade to<br />

fight for a Bengali land still in limbo but suffering mightily under the hand of<br />

West Pakistan.<br />

I had just entered Dhaka with a unit of the Mukti Bahini.<br />

In the company of Rafiq Hussain—eldest son of the first Bangladeshi family<br />

to welcome me into their home in the Segun Bagicha neighbourhood, and who<br />

later became my friend—I saw Jacob at Race House on December 16, standing<br />

behind (and letting himself eclipsed by) his colleague, General Jagjit Singh<br />

Aurora, signing, in Niazi’s presence, the act of surrender that he had penned.<br />

The next day, I happened to see him again with a handful of journalists and<br />

heard him speak of Malraux, whom he was reading; of Yeats, whose poems he<br />

knew by heart; of his twin Jewish and Indian identity; of Israeli General Moshe<br />

Dayan, whom he worshipped; and of the liberation of Jerusalem, which he<br />

held as an ex<strong>amp</strong>le of military skill. But to my recollection he said nothing<br />

about the intensely dramatic, stirringly romantic, face-to-face encounter with<br />

Niazi in which the war of personality carried a thousand times more weight<br />

than the war between armies - an encounter that determined the fate of the<br />

young Bangladesh.<br />

I can picture his mischievous look.<br />

His rather heavy silhouette, unimposing in itself though emanating an<br />

incontestable authority.<br />

And his strange and reticent way of remaining a step or two behind his<br />

comrades in arms, generals Aurora and Manekshaw, as if reluctant to claim<br />

any credit for a feat of audacity that I now know was his alone.<br />

He appeared to me, that day, like a representative of one of the lost tribes,<br />

spreading the genius of Judaism.<br />

He might have been a Kurtz from Kaifeng, Konkan, Malabar,or Gondar,<br />

newly returned from the heart of darkness but ready to head back up the river.<br />

Or a biblical Lord Jim or Captain Mac Whirr, done for good with typhoons and<br />

ready to forge an alliance with the coolies.<br />

People who save Jews are known in Judaism as righteous. How should one<br />

refer to a Jew who saved, raised to nationhood, and baptized a people who<br />

were not his own? •<br />

(Translated from the French by Olivier Litvine)<br />

Bernard-<br />

Henri Lévy is a<br />

French public<br />

intellectual,<br />

media personality<br />

and renowned<br />

author. In 1971,<br />

Lévy travelled<br />

to the Indian<br />

subcontinent,<br />

and was based<br />

in Bangladesh<br />

covering the<br />

Bangladesh<br />

Liberation War<br />

against Pakistan.<br />

This experience<br />

was the source<br />

of his first book,<br />

Bangladesh,<br />

Nationalisme<br />

dans la révolution<br />

(“Bangladesh,<br />

Nationalism in the<br />

Revolution”, 1973).<br />

The translator is<br />

former director<br />

of Alliance<br />

Fraicaise, Dhaka.<br />

3<br />

DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, <strong>September</strong> 7, <strong>2017</strong><br />

ARTS & LETTERS

Book review<br />

Romantic melancholy in the<br />

poetry of Nadeem Rahman<br />

Rebecca Haque<br />

is Professor,<br />

Department of<br />

English, University<br />

of Dhaka. A poet,<br />

translator, and<br />

literary critic ,she<br />

has published two<br />

books of literary<br />

criticism, and a<br />

book of creative<br />

writing. She<br />

regularly writes<br />

Op-Ed and nonfiction<br />

essays for<br />

The Daily Star.<br />

4<br />

• Rebecca Haque<br />

In my hands I hold a sleek copy of Nadeem Rahman’s new volume of<br />

poetry. The title, One Life Is Not Enough, captivates me with felt echoes<br />

of the labyrinthine travails of the mythic “hero of a thousand faces.” The<br />

deceptively simple title resonates with the passion and complexity of<br />

a Beethoven symphony: It is spoken poetry<br />

incarnate, with its rhythm of a rise and fall of<br />

a lung full of air inhaled and exhaled, sighing<br />

with dreams and yearnings even in ripe<br />

old age. It is suffused with hopes and desires<br />

innate to the mortal human struggle, bound<br />

in time and space, eternally battling the elemental<br />

forces. Allusion to life’s tragicomic<br />

journey evokes a subliminal melancholy, an<br />

elegiac mood. In defining the state of human<br />

existence, it makes me bond with the poet in<br />

universal sympathy.<br />

One Life Is Not Enough, published in November<br />

2016 by the select house of writers.<br />

ink, contains sixteen poems which draw us<br />

into the creative spiral of the poet’s psyche.<br />

The honest confessional mode makes us<br />

identify with Rahman in separate stages of<br />

his mapping of life’s moments of strife and<br />

sweetness. We are led upward and onward<br />

through the developing arcs of his growth<br />

into introspective middle age. Rahman’s<br />

books depict an odyssey spanning thirty<br />

years of a mature man’s journey, and this volume<br />

is the final arc which completes the circle<br />

of poetic self-discovery begun in youthful<br />

exploration of lived experience.<br />

One Life Is Not Enough reveals a man of<br />

charm, wit, and piquancy: Well-read, articulate,<br />

contemplative, often blasé and ironical,<br />

as is the way with men of a philosophical<br />

mind. The poems are self-reflexive, and<br />

formal unity is maintained by adherence<br />

to ritual: Each poem is composed on his birthday. In the prefatory essay, “A<br />

Birthday Ritual,” Rahman provides an account of the process of composition:<br />

“By sheer chance, I happened to write a poem on my forty seventh birthday.<br />

I liked it so much, that I once described it as ‘something of a signature tune,’<br />

and I have included it in all my books of poems so far. It’s the last poem in<br />

this collection. Since then, equally by chance, it has become a birthday ritual.<br />

I have no explanation for this odd occurrence, but it never ceases to surprise<br />

me, every year, and is a source of considerable satisfaction to the creative urge<br />

in my generic composition. Once a year, I am happily reminded that my dwindling<br />

poetic instincts have not yet demised. The candle dims, but the flame<br />

still burns. … “<br />

Rahman’s “signature poem” in One Life Is Not Enough is titled “Our Last<br />

Rendezvous”, and was first composed on 17th May, 1991. It is a passionate<br />

poem, heroic in its melancholy acceptance of flux and finite existence, yet redolent<br />

with the romance of having drunk deep the draught of Life’s immanent<br />

spirit. The title and the sublime metaphysical conceit of this poem bring to<br />

my mind the lyric eloquence of Robert Browning’s “The Last Ride Together”.<br />

Like Browning’s poem, Rahman’s poem is also a dramatic monologue, and<br />

has the same quiet intensity and sacred beauty of the image of two embraced<br />

souls. Like Browning, Rahman also idealises and apotheosises his beloved:<br />

“Let this be our last rendezvous/ when the rivers cease to run/here will you<br />

find me/ in this valley of dying stars/ where my songs have fallen, one by one,<br />

/ and my soul, lies softly crying, …/In my book / of squandered dreams/ and<br />

forfeited schemes/ will I haunt you/from the<br />

shattered/jaws of time, until/ eternity/ here/<br />

in my heartbeat / of wordless speech,/ will I<br />

call you/ to embrace,/ my unrequited/ ghost/<br />

and let my lost hopes/ be the venue, of our<br />

last/ rendezvous.”<br />

The Romantic sensibility has used the motif<br />

of the Wanderer, the questing Traveller to<br />

signify the primordial role of the bard-seer,<br />

be it the quasi-spiritual poetic scop/ minstrel<br />

of Western medieval Courtly tradition, or the<br />

Sufi ‘baul ‘ of Eastern mysticism. Elements of<br />

such mystic self-reflection creep into many<br />

of Nadeem Rahman’s mature poems. For<br />

ex<strong>amp</strong>le, in “When I am Dead and Gone”, he<br />

writes, “When I am dead and gone/ I will have<br />

left one last song,/ …because/ dying is a poem<br />

/ of the undying/heart.” In ”You Who Think”,<br />

Rahman captures the quintessence of mortal<br />

desire: “You, who think, that I in my old<br />

age/ can teach you nothing of love,/ consider<br />

for a moment/ the infant moons that light<br />

my path/ are wrought from the nebula of my<br />

soul/ -- as true a lover’s gift as any, from/ the<br />

black hole of my infernal firmament,/ and the<br />

love that burns your blood, is distilled / from<br />

stars called hope and disappointment,…” In<br />

the 2010 birthday poem, ”Today Is My Birthday”,<br />

Rahman is self-assured and confident,<br />

and mature acceptance of personal failures<br />

makes it a poem of courageous dignity and<br />

not a vehicle for mere braggadocio: “every<br />

birthday is a resurrection,/…I am in no hurry,<br />

for/ fate to shut the door./ I look into the mirror, and I no longer see / the different<br />

faces I have seen before—the curiosity/ the impatience, the anticipation<br />

and the wander lust, / …the flamboyant arrogance of youth have all faded,…”<br />

Rahman’s poetry betrays the influence of major poets in the English and European<br />

Romantic tradition. All writers write under the “anxiety of influence”<br />

to some degree, however, and a poet becomes note-worthy when his unique<br />

“voice” speaks to us directly through his poems. William Wordsworth’s definition<br />

is cogent: “What is a poet?...He is a man speaking to men: a man, it is<br />

true, endued with more lively sensibility, more enthusiasm and tenderness,<br />

who has a greater knowledge of human nature, and a more comprehensive<br />

soul, than are supposed to be common among mankind;…” Nadeem Rahman<br />

is such a man. And even though, in “A Birthday Ritual,” Rahman writes, “I<br />

don’t expect to be read even a quarter century from now….it’s enough that<br />

I have lived. It’s enough that I have loved … It’s enough that I leave my poems,<br />

like the fragrance of my flesh and blood, the essence of my never-ending<br />

dreams”, I am certain that much of his poetry will be read again and again for<br />

their sustained lyric power and sympathetic vision.•<br />

ARTS & LETTERS DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, <strong>September</strong> 7, <strong>2017</strong>

Tribute<br />

Shankhachil’s Shaheed Quaderi issue:<br />

A fitting tribute to the poet<br />

• Junaidul Haque<br />

Shankhachil, an art and literature magazine, dedicates its January <strong>2017</strong> issue<br />

to poet Shaheed Quaderi, who died in August, the month of his birth, in 2016.<br />

Work had started three months before his death. Mahfuz Pathak and Iqbal<br />

Mahfuz, the editors, had written to the poet in June 2016. The poet’s wife,<br />

Neera Quaderi; his niece, Sadaf Quaderi; poet Rifat Chowdhury, writer Adnan<br />

Syed and artist Rajiv Dutta helped the editors to bring out the issue.<br />

The 350-page magazine has a portrait of<br />

the young poet on its cover. There is a child<br />

Shaheed Quaderi on page 10 and a boy Quaderi<br />

on page 51. There are a few rare and wonderful<br />

photographs. The articles and poems are<br />

divided into eighteen sections. The contents<br />

are certainly rich.<br />

“Smritimegh” (Clouds of Memories) has<br />

thirteen reminiscing articles on the poet.<br />

The writers include Al Mahmud, Alokeranjan<br />

Dasgupta, Abdullah Abu Sayeed and<br />

Nirmalendu Goon. Neera Quaderi, Sadaf and<br />

Simone Quaderi are also there. So are Kabir<br />

Sumon and Helal Hafiz. Quaderi began to write<br />

in his childhood, almost playfully. His father<br />

inspired him and suggested corrections to his<br />

writing. I wonder, though, why Al Mahmud<br />

calls his close friend “Shaheed Quaderi Saheb”<br />

in his short essay. Dasgupta first met him in<br />

Germany’s Cologne in 1978. His essay is short<br />

too. Neera Quaderi’s “Amar Bandhu, Amar<br />

Priyotomo” comes straight from her heart. So<br />

do Sadaf and Simone’s recollections. Simone<br />

almost brought tears to our eyes. Abdullah Abu<br />

Sayeed speaks about Quaderi’s sorrow and wit.<br />

One day Sayeed had asked him about his not<br />

giving importance to academic education. He<br />

could be an international celebrity! Quaderi<br />

sadly replied that as a young man he had<br />

thought he would be a Tagore and wouldn’t need degrees! Yes, friends<br />

confirm that Quaderi was a prodigy. Akhter Hussain’s weeping photo over<br />

Quaderi’s coffin, also, brings tears to our eyes.<br />

“Jolchhaya” (Shades of Water) has twelve essays on him. Humayun<br />

Ahmed the popular novelist attracts our attention with a good one. Rifat<br />

Munim’s English essay is well-written. The “Adda” section wins my heart<br />

with five lovely articles. Shaheed Quaderi’s brilliant friends read a lot and<br />

spent a lot of time together. Adda was necessary for their creativity. “Bish<br />

Minuter Adda” between Syed Shamsul Haq and Shaheed Quaderi on July 07,<br />

2010 wins my heart. Excerpts:<br />

SSH: What literature does … didn’t know own brothers and sisters, knew<br />

…<br />

SQ: Friends.<br />

SSH: Friends. Hahaha, life is gone.<br />

Belal Chowdhury, a famed addabaz himself, gives a lovely account of<br />

Shaheed’s adda. Shihab Sarkar’s tribute is superb. He compares Quaderi to<br />

Sudhin Dutta. He calls him the wonder boy of Bangla poetry. Only four books<br />

and a few scattered poems will keep Quaderi immortal, he feels. Iqbal Hasan<br />

and Neera Quaderi are also quite interesting.<br />

The “interview” section is good. Adnan Syed’s interview of novelist<br />

Mahmudul Huq on Shaheed Quaderi is a nice one. Tamizuddin Lodhi,<br />

Shams Al Momin and Shikha Ahmed’s interviews of the poet are interesting.<br />

The poet calls Kazi Nazrul Islam “our Neruda,” talks of the inspiration he<br />

received from Shamsur Rahman and his brilliant poetry and confesses that<br />

it was suicidal for him to leave Bangladesh, his motherland. Twenty one<br />

poets are included in the “Poems Dedicated” section. I wonder why Abul<br />

Hasan’s name comes ahead of Shamsur Rahman’s. This won’t be liked by<br />

many a reader. Rafiq Azad, Sikder Aminul Huq and a host of younger poets<br />

are there. Shamsur Rahman, in his poem, asks the self-exiled poet if he<br />

“suddenly woke up during sleepy moments<br />

at the smell of Beauty Boarding and Luxmi<br />

Bazar.” Faruk Alamgir and Faruk Foysal<br />

dedicate long poems to him. Two sonnets by<br />

Mohiuddin Mohammad and Rabiul Alam Nabi<br />

are also there. There are eight portraits of the<br />

poet by noted artists like Qaiyum Chowdhury,<br />

Murtaza Baseer, Mashuk Helal, Nazib Tareq<br />

and Rajib Dutta. “Chitrakabya” has a few more<br />

sketches. “Chitrakotha” has sketches in words<br />

by Nirmalendu Goon, Nasir Ali Mamun, Kabir<br />

Sumon and Imdadul Huq Milon. The poet,<br />

who has declared that poetry was his kingdom,<br />

speaks about his Beauty Boarding days.<br />

“Music” talks about songs based on his<br />

poems. “Anugalpa” or seven micro-stories are<br />

based on his poems. Kuloda Roy and Afsana<br />

Begum are impressive. “Translation” has five<br />

very good poems translated nicely by Farida<br />

Majid, Shawkat Hussain and Sayeed Abubakar.<br />

“The Last Descendant” and “My Brother<br />

Answers The Door” are by Farida Majid. “Left<br />

Right Left” and “You Know” are by Shawkat<br />

Hussain. “Poet” and “We Three” are by Sayeed<br />

Abubakar. The “Mulyayan” or Evaluation<br />

section has thirteen essays, ranging from<br />

stalwarts like Abdul Mannan Syed and Kaiser<br />

Haq to young writers. Mannan Syed is thoughtprovoking<br />

as usual. Kaiser Haq’s 1974 review<br />

of Tomake Abhibadan Priyotoma is outstanding. Anu Hossain and Ahmad<br />

Mostofa Kamal have contributed two good essays. “Daakghar” has a few<br />

letters written to Shaheed Quaderi and a few written by him. Letter writers<br />

include Shawkat Osman and Fazal Shahabuddin.<br />

The last section “Kobir Bhubon” or The World of the Poet includes three<br />

lovely essays by Quaderi, a few of his best poems and a life-sketch by Faruk<br />

Mohammad. Quaderi’s essays on Buddhadev Bose and Pablo Neruda are<br />

wonderful pieces. One of our finest modernists was a very erudite man too.<br />

Very scholarly and very witty. The magazine winds up with seven previous<br />

reviews of Sankhachil.<br />

Sankhachil’s Shaheed Quaderi issue will attract many readers. They have<br />

thrown light on every aspect of the gifted poet’s life and works. The poet was<br />

and still is loved by Bangladeshis. This issue will also be loved by them. He<br />

was one of the best poets produced by this land. •<br />

Shankhachil<br />

An art and literature magazine<br />

Shaheed Quaderi issue, Poush-<br />

Magh 1423<br />

Pages 350, price Taka 150<br />

Editors: Mahfuz Pathak and<br />

Iqbal Mahfuz<br />

Junaidul Haque<br />

is a bilingual<br />

writer of fiction<br />

and essays. Born<br />

in 1955, he did<br />

his MA in English<br />

Literature from<br />

the University<br />

of Dhaka. He<br />

has published<br />

two novels<br />

(Asambhaber<br />

Paye and Bishader<br />

Tarunya), four<br />

volumes of<br />

stories and two<br />

volumes of short<br />

essays. Pathak<br />

Samabesh is the<br />

publisher of his<br />

Nirbachito Galpa.<br />

5<br />

DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, <strong>September</strong> 7, <strong>2017</strong><br />

ARTS & LETTERS

Book review<br />

The Newlyweds:<br />

A pseudo ‘Bangladeshi’ novel<br />

with a real heart<br />

6<br />

• Neeman Sobhan<br />

I<br />

have to confess that I picked up Nell Freudenberger’s The Newlyweds<br />

because the protagonist was from my country of birth. With all the<br />

concerns about cultural appropriation raging in recent times, I was<br />

curious about a white American writer dealing with a Bangladeshi<br />

protagonist who meets an American engineer through an online dating<br />

service and marries him to migrate to the USA.<br />

Before I unpack my opinions, I should make it clear that I count Kazuo<br />

Ishiguro’s Remains of the Day as one of the finest books I have ever read. A first<br />

generation British-Japanese writing -- an authentic ventriloquist novel in the<br />

voice of Stevens, an English butler who represents a quintessentially British<br />

institution. So, my position on the debate about who “owns” a culture, and<br />

who might or might not be “allowed” to write about it, should be apparent.<br />

Yet, it’s not easy when it’s your Sacred Cow that’s being milked. My<br />

approach is to use the “Appreciator versus Appropriator” binary. If an<br />

empathetic outsider chooses to represent my culture, I have no objections, as<br />

long as it’s done artistically and accurately. Herein lies my basic problem with<br />

Freudenberger’s book.<br />

Every page of The Newlyweds, however heartfelt in its writing, has<br />

some major or minor discrepancies regarding Bangladeshi culture that is<br />

unlikely to occur at the hands of a native writer. Naturalistic fiction such<br />

as Freudenberger’s novel relies on verisimilitude, which is undermined<br />

by factual errors.*(A partial list is appended at the end of this essay) When<br />

parts of the depicted world and its inhabitants do not feel real or convincing,<br />

how can you take a fiction seriously and focus on its redeeming artistic or<br />

philosophical sides?<br />

None of the past reviewers of the book, I notice, were from Bangladesh.<br />

Not surprisingly, most of them concentrate on the artistic issues, accepting<br />

at face value Bangladesh’s culture as the exotic spice that adds piquancy. “A<br />

marvelous book,” extols Kiran Desai on the cover. Desai is an Indian author<br />

and she does not notice the factual flaws; she only deals with the aesthetics<br />

of the narrative. She found the bouquet pretty. For me, however ardently the<br />

florist wants me to accept the bunch as real, I know that many of the flowers<br />

are fake.<br />

I have not read Freudenberger’s previous novel, The Dissident, which<br />

shot her to acclaim as one of the New Yorker Under 40 writers and Granta’s<br />

Best Young American Novelists. I did, however, read her impressive fictional<br />

debut, a collection of short stories, Lucky Girls, which deserved the literary<br />

accolades it won. But after reading her present novel, I would safely hazard<br />

that Freudenberger’s literary strength lies in the field of short fiction and not<br />

in novel writing; certainly, not a novel about a world she only knows sketchily.<br />

Freudenberger has lived in India but not in Bangladesh. She probably<br />

thought that the fictional leap from Delhi to Dhaka could not be such an<br />

insurmountable distance, aided by some historical research and socio-cultural<br />

observations. Unfortunately, it was a bridge too far.<br />

Freudenberger presumed to tell the story of her Bangladeshi protagonist,<br />

Amina, based on a real life encounter with a Muslim Bengali woman<br />

whose unconventional story inspired the novel. But Amina is a half-baked,<br />

unconvincing creature, not reflecting any real, modern-day woman living in<br />

the Dhaka of 2005. In just the first few chapters of the book, where we get<br />

to know Amina as she tries to create her American life in the suburbia of<br />

Rochester, we trip over many inconsistencies about her past life.<br />

But even as my quarrel with the writer was that she was not getting the<br />

details right, I could sense the sincerity in her portrayal of Amina, and her<br />

sympathetic and respectful treatment of cultural and religious diversity,<br />

and the vulnerabilities of the migrants’ life. What softened my heart was the<br />

realisation that she was fully aware of being on shaky grounds on matters<br />

related to Bangladesh, and in subtle ways, she created grounds for us to look<br />

at her approach differently.<br />

For ex<strong>amp</strong>le, the character of Kim, Amina’s husband George’s bohemian<br />

Yoga instructor-cousin, seems expressly created to represent Freudenberger.<br />

Early in their friendship, Amina is made to think this on behalf of all<br />

potentially critical native readers like me: “There were a lot of things about<br />

village life she thought might surprise her new friend, but she didn’t want to<br />

undermine Kim’s admiration for her culture, which she thought was genuine<br />

if not especially well informed.”<br />

My copy of the book is underlined on every page with a question mark or<br />

comment in the margins. Often I was frowning, but in the end, I burst out<br />

laughing. This novel is an unintentional comedy of errors, and only insiders<br />

like us Bangladeshi readers would know the truth. And that is the unfunny<br />

part involving cultural appropriation. An established writer, with the power<br />

of the publishing world behind her, gets away with telling a flawed story of my<br />

culture, and wins plaudits for her performance.<br />

The redeeming feature, however, is that the errors were mostly innocent,<br />

and even when she does not get the facts right, there are truths aplenty.<br />

“You thought you were the permanent part of your own experience, the net<br />

that held it all together, until you discovered that there were many selves,<br />

dissolving into one another...”<br />

Still, I itch to edit and correct the silly mistakes. But the important question<br />

I ask myself is that even with the errors, is the story something that makes the<br />

world a better place? I think it does. If an outsider reaches out to understand a<br />

nation unrelated to her own world, it brings us all closer. Freudenberger wrote<br />

with genuine compassion and a desire to embrace an unknown world through<br />

her imagination.<br />

In the novel we encounter the notion of adoption. Kim is an adopted child,<br />

and she, in turn, adopts an Eastern ethos that is incongruous with her western<br />

upbringing. Much of her yogic life style is a mixed-up, pseudo-philosophy.<br />

But it is her version of Indian spirituality. She claims ownership by dint of her<br />

genuine ardency and humanity.<br />

The book ends with a winning essay written for a Starbucks writing<br />

competition. The essay, I feel, is the metaphor for the novel. Unbeknownst to<br />

Amina, Kim writes Amina’s story, using her words, images and dreams. She<br />

knows she does not own this borrowed story, but she shapes it lovingly, then<br />

gives it away as a gift.<br />

I think it is unfair of me to call Freudenberger’s creation a “pseudo” novel.<br />

It may not be my Bangladeshi novel. But this is her version of a borrowed<br />

Bangladeshi story, written from her heart.<br />

The last sentence of the Starbucks essay is also the last line of the novel,<br />

the bobbing message-in-a-bottle:“It is only by sharing our stories that we truly<br />

become one community.”<br />

*Some anomalies in The Newlyweds<br />

Historical:<br />

1. Amina’s father was a freedom fighter and he recalls how a fellow guerilla,<br />

towards the end of the war, “got through the awful street battles here in<br />

Dhaka.” We know that there were guerilla operations, but no pitched<br />

ARTS & LETTERS DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, <strong>September</strong> 7, <strong>2017</strong>

attles were fought on the streets of Dhaka, especially towards the end<br />

when the city -- the last bastion of the Pakistani forces -- fell under attacks<br />

from advancing mukti-joddhas (freedom fighters) and the Indian Air force.<br />

The mistake is not grave. But it is the responsibility of a writer to verify<br />

all historical facts. When the writer is a foreigner this becomes even more<br />

important.<br />

2. Amina is thinking about her maternal uncles: “The elder, Khokon, had been<br />

Mukti Bahini like her father...” A native writer would say that “he had been<br />

IN the Mukti Bahini or had joined it.” Or, that “He had been a mukti joddha.”<br />

Sociological errors<br />

1. Amina has studied at Maple Leaf International School in Dhaka, tutored<br />

O-level students, and applied to American universities, but is not sure<br />

what “dumbstruck,” “hamster,” or “thank my lucky stars” mean. MLIS<br />

is an English medium school, a reputed one at that, which follows the<br />

Cambridge IGCSE curriculum. Even a mediocre student from that school<br />

would know the meanings of those expressions, not to mention someone<br />

who’s tutored O-level students.<br />

2. She presents her parents with a TV when she is seventeen, so she must have<br />

watched American TV shows, like my generation had. Since the late sixties<br />

when Television started in Dhaka, shows such as Star Trek, Dr Kildare, The<br />

Lucy Show and Dallas were broadcast. Yet America is a totally unfamiliar<br />

territory to her.<br />

3. Unbelievably, even India is unfamiliar to her (despite ZEE TV or all those<br />

other Indian channels offering all the latest and classic Bollywood films!):<br />

“Her own idea of India encompassed the Taj Mahal, the great Saint’s tomb<br />

at Ajmer…the rest of the country was simply coloured shapes on a map, and<br />

she had only the vaguest notion of yoga as a Hindu religious ritual.”<br />

4. A bundle of contradictions is Amina’s mother who helps her pass O-level<br />

exams by underlining unfamiliar words for her to review. She reads the<br />

Lifestyle page on The Daily Star’s website, doesn’t speak any English,<br />

but later “surprises” Amina by asking about her son-in-law’s work:<br />

‘“Engineering job?’ her mother said in English. She hadn’t known her<br />

mother knew those words.”<br />

5. The mother’s ambitions for her daughter do not really resonate with anything<br />

Bangladeshi. She “had always hoped to make her a famous singer, and<br />

when they discovered that Amina hadn’t inherited her mother’s beautiful<br />

voice, they had tried ballet, the Bengali flute, and even ‘Ventriloquism:<br />

History and Techniques.’” Despite all the hegemonic presence of many<br />

European influences, ballet and ventriloquism are way too far-fetched for<br />

any Bangladeshi mother who does not speak English.<br />

6. Amina goes to the British Council in the mornings to check emails from<br />

George “before her tutoring responsibilities began.” Note the logistical<br />

anomalies in these traffic-congested times: Amina lives in Tejgaon (where<br />

internet cafes abound), has to go to Gulshan to tutor her pupil Sharmila<br />

(where she has free use of her student’s computer, having used it to<br />

navigate the dating website), yet she proceeds first to the British Council,<br />

which, again, involves another commute of one or two hours just to use<br />

the computer!<br />

7. Her father studied engineering at Rajshahi University but he does not speak<br />

any English. So much so that Amina is anxious about letting her parents<br />

travel alone and not being able to “find the connecting flight to New York<br />

once they left the Bangla-speaking attendants from the first flight.” Yet he<br />

is the one who helps her with the technical parts of the “administrative<br />

processing” form for the visa given at the American embassy.<br />

8. Freudenberger uses the term “Desh” and “Deshi” with a capital “D” as<br />

if these were officially accepted abbreviations and synonyms for the<br />

name of our country and nationality! The name of the political entity of<br />

Bangladesh cannot be shortened to Desh, just as Pakistan cannot become<br />

Stan. A Pakistani might refer to his land as “mulk,” “watan,” or “des.” But<br />

this term, Desh, can be used even by an Indian Bengali to refer to West<br />

Bengal or India. Furthermore, people inside Bangladesh often say “Desh e<br />

gechhilam” to mean s/he visited their ancestral home to spend time with<br />

family. So, Bangladesh and Desh cannot be used interchangeably. Yet this<br />

happens repeatedly in the novel: (Kim emails Amina) “I’m not allowed to<br />

go anywhere… that might be unsafe. They laughed when Ashok brought<br />

up the idea of a trip to Bangladesh. Of course I know Desh is perfectly<br />

safe...”<br />

9. Amina glances at a bookshelf in an educated middle class home: “She<br />

recognised Tagore, Mukhopadhyay and Nazrul Islam.’ Mukhopadhyay?<br />

There are several Mukhopadhyays in Bengali literature. Perhaps the writer<br />

indicated Sharatchandra Mukhopadhyay. Unlike the American tradition,<br />

in Bengali culture and literature, the first name of a writer is usually picked<br />

up to refer to him/her; it is more so when the last name is common to many.<br />

Names:<br />

In real life people are free to use whatever name they fancy. But a storyteller,<br />

to maintain the illusion of reality must give characters culturally accepted<br />

names to impart a true flavour of a society. In this novel, most names are<br />

strange and un-Bengali, a fact which ruins the credibility of the story. Odd<br />

female names: Ghaniya; Micki, Mokta (Mukta?) Asah (Asha?) Botul (Bokul or<br />

Batul?). Male names: Fariq (Tariq?) Ghoton (Choton?) Shajar. Uncle Noresh,<br />

and great-uncle Sudir (Sudhir?)Haji.<br />

Food:<br />

1. “…she added too much paprika to the rice.”<br />

2. “…the pulao was fragrant with anise…”<br />

3. Amina at her father’s hospital bedside “… fed him three spoonfuls of the<br />

dal…”<br />

4. Bemoaning a less than perfect wedding meal: “…the mutton had been<br />

overcooked…” Imagine a biryani in which the meat was not falling off the<br />

bone but under-done!<br />

5. She is carrying back to Dhaka, among other things, “… six Dole pineapple<br />

juice boxes.”<br />

There, however, are many more instances of such inaccuracies. •<br />

Neeman Sobhan is<br />

a writer, poet and<br />

columnist. She lives<br />

in Italy and teaches<br />

at the University<br />

of Rome. Her<br />

published works<br />

include a collection<br />

of her columns,<br />

An Abiding City:<br />

Ruminations<br />

from Rome (UPL);<br />

an anthology<br />

of short stories,<br />

Piazza Bangladesh<br />

(Bengal<br />

Publications);<br />

a collection of<br />

poems, Calligraphy<br />

of Wet Leaves<br />

(Bengal Lights).<br />

7<br />

DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, <strong>September</strong> 7, <strong>2017</strong><br />

ARTS & LETTERS

Short story<br />

The imminent, the impending<br />

• Kayes Ahmed<br />

(Translated by Parveen K. Elias)<br />

8<br />

Anwar saw a grayish fox dig its teeth into his shoulders and tear at<br />

his flesh. As he felt the searing pain, he lifted his hand to push the<br />

fox away. At that moment, he awakened.<br />

Just like the hose which lies on the ground and spurts out water<br />

to wet the ground, so too pain spurted from Anwar’s left shoulder and armjoints<br />

and spread across.<br />

In his head, he felt numerous blunt saws hacking through his brain.<br />

And just behind the retina of his eyes a hook now pulled, now slackened.<br />

Anwar turned his head this way and that way as he lay. His eyelids fell<br />

down heavily from under which he watched with burning red eyes. Where<br />

was the fox?<br />

Above him clusters of bamboo hung down on all sides. Crickets chirped<br />

intermittently. In the suffocating grove of pineapples, his body itched, not to<br />

speak of mosquito bites. Anwar lay flat and groped with eyes shut. He felt the<br />

stony coldness of the rifle.<br />

Hafiz and the others must have certainly become stiff by now. Having<br />

become wet in the rain, would the rotting start right away? This soon? Who<br />

knew?<br />

Anwar held his breath in the suffocating heat full of foul stench, the wet<br />

ground, his wet, hot body, the closed confinement of the trees. He believed<br />

that if he didn’t hold his breath, he would be bound to smell the stench coming<br />

from wet corpses of his comrades lying by the bank of the canal.<br />

For a few seconds he remained in a dilemma. Then he closed his eyes and<br />

took a full, deep breath. Somewhere pineapples had ripened. That sweet smell<br />

penetrated his head. Some of it managed to enter his stomach also. It seemed<br />

as if the fox of his dream had now entered his stomach, and was ripping away<br />

at his intestines.<br />

Anwar swallowed and his throat felt absolutely dry. His hot, wet tongue<br />

tasted bitter. His mouth was sticky. Anwar licked his lips. He felt a salty taste<br />

and kept licking over and over to savour this taste. Sand particles gritted at his<br />

teeth. He opened his mouth wide, took a breath, licked his lips again. If only<br />

he could eat something to fill up, then his head would lighten and he could sit<br />

up and look at his surroundings clearheadedly.<br />

Maybe, he should just get up, sling his rifle on his shoulders and look for<br />

the ripe pineapple. This was a large pineapple grove. Surely there was more<br />

than one ripe pineapple!<br />

He would rip off ripe pineapples from the plants, slash and thrash them and<br />

then eat to his heart’s content.<br />

Anwar’s insides yearned for food. Lying with closed eyes, Anwar saw that<br />

he was surrounded by numerous golden pineapples and he was ferociously<br />

snatching and gulping down one after the other. The slightly yellow juice drooled<br />

from the sides of his mouth and fell through his fingers on to the ground.<br />

Anwar could not stand it anymore. With closed eyes he jerked his body and<br />

sat up straight. The wound in his shoulder woke up with a searing pain and he<br />

felt dizzy and suffocating. His heavy head swung like a football on a finger-tip,<br />

numerous yellow bubbles danced before his eyes and darkness set in.<br />

He fell flat on the pineapple plant and the sharp-edged leaves cut through<br />

his cheeks, ears, neck and hands.<br />

Anwar bit his lips as tears flowed from his eyes. His body trembled a little,<br />

then became still.<br />

When Ratan’s head burst open and his skull opened from near his forehead<br />

like the lid of a box, Ratan fell and at once his whitish-brown brain slumped<br />

out on to the ground. You could not see his face, his rifle lay beside, it seemed<br />

a torrent of bullets just stirred his lifeless body and vanished into the mud.<br />

Lying in the pineapple grove, Anwar groaned and rubbed his face. His body<br />

heaved and his face started to turn blue.<br />

With the piercing pain in his shoulder where the bullet had hit, Anwar kept<br />

running on and on. Was there no end to these jute fields that were stretched<br />

out before him?<br />

The track between fields was narrow and at places very muddy. Sometimes<br />

hard sticks of stooping jute-plants had come over the track. Patches of grass<br />

were there on the slopes of the track, weeds of all kinds entangled his feet. In<br />

the darkness, nothing --neither mud nor barrier-- was visible, and the steps<br />

were missed. In addition, there was hardly any air between thickly grown jute<br />

plants nine feet tall. This wall seemed to have choked even the normal space<br />

of breathing.<br />

Anwar scrambled to rise like a man who is drowning under deep water. His<br />

feet wouldn’t move. He fell over in the field. The jute branches scratched at<br />

his face and he opened his eyes. He saw a long shadow and felt the touch of a<br />

hand on his forehead. He was about to shriek in fear but a hand closed over his<br />

mouth. He heard, “Anwar, keep quiet, I’m Hafiz!”<br />

Anwar tried to sit up in great agitation “You . . .you . . .!” Hafiz lay him down<br />

again, “You have a very high fever.”<br />

Anwar shook violently, his heart palpitated fast. He held Hafiz’s hand and<br />

kissed it again and again, his eyes filled with tears.<br />

“You are alive! How amazing!” He got up and touched Hafiz again and again<br />

as if to make sure of his presence. Hafiz laughed silently.<br />

“What about the others - Barkat, Hormuz, Mian?” “I don’t know; they’re<br />

probably gone.” Hafiz spoke between pauses, in a solemn voice.<br />

Somewhere a bird fluttered its wings. The crickets screeched ceaselessly,<br />

the mosquitoes buzzed. In the deep darkness of the last hours of the night,<br />

two war comrades sat silently beside each other. Through the shoots and<br />

leaves of the bamboo grove came the very faint moonlight and the fragmented<br />

shadows of the two friends fell on the pineapple plants. As he looked at the<br />

shadows, Hafiz saw himself standing in the dirty, neck-deep water of the canal<br />

with hyacinth leaves on his head.<br />

Anwar could not keep sitting any longer. If he lay on one side his mouth<br />

filled with salty water. A surge of vomit seemed to push it up. But nothing<br />

came out of his empty stomach, only salty-bitter glutinous saliva. Hafiz<br />

caressed his head. Anwar lay gasping with his mouth wide open. His mouth<br />

got dried up quickly. From his mouth down to his throat and chest persisted<br />

ARTS & LETTERS DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, <strong>September</strong> 7, <strong>2017</strong>

a dryness which was worse than the dry pools and puddles in the month of<br />

Chaitra. At least some dust rose from those puddles but nothing emerged<br />

from the dryness within Anwar.<br />

Hafiz looked around and said, “I can smell ripe pineapple, let me go and see<br />

what I can find.” Hafiz got up and left. His footsteps on pineapple leaves made<br />

a rustling sound, and as they became fainter, Anwar began to feel drowsy once<br />

again.<br />

Anwar was being lifted into space slowly, up above the heads of bamboo<br />

trees. From up there he saw the fox pulling out the intestines from Hormuz<br />

Ali’s stomach. Anwar began to come down, and seeing him, the fox fled.<br />

“Look Anwar, look! This way, see how many shaplas there are!” The little<br />

boy Barkat was laughing in his boat as he called out. Shapla flowers filled his<br />

boat to the brim.<br />

Waving his hands like a flag, Barkat rowed his boat further and further<br />

away. Anwar wondered how Barkat had become so little again.<br />

“Listen, Barkat . . .”<br />

“No, I can’t-- I’ll be late for school.”<br />

Anwar opened his eyes and saw Hafiz standing beside him, holding out a<br />

piece of unskinned pineapple.<br />

“There are no houses around here, only jute fields. The condition you are<br />

in, I’m not sure how far I can carry you by myself. If the bullet in your shoulder<br />

is not taken out soon . . .” Hafiz looked very worried. Then he changed his tone<br />

and asked, “Has your nausea disappeared”? Anwar replied, “Huh?”<br />

“Isn’t it strange that there should be a pineapple grove in this place? Does<br />

the owner get anything for his fruit?” Hafiz laughed.<br />

“Thank God for the grove. I never imagined I would find you like this.<br />

I stopped when I heard the sound of someone groaning in pain. I felt<br />

instinctively that it must be one of us. It was such a thrill! You were groaning<br />

and scratching your face. Your shoulder was wet with blood. I felt and saw<br />

that the bleeding was now normal, but you were burning with fever. Anwar,<br />

have you fallen asleep? Listen . . . Anwar!”<br />

“Huh . . .?”<br />

“It might be a good idea to take off your wet shirt. The fever is so high.”<br />

Anwar opened his eyes. The aches and pains in his entire body plus the<br />

heat- it would really help if he could take off the sticking wet shirt. But that<br />

was impossible in his condition. He couldn’t do it.<br />

“Here, eat this,” Hafiz gave him another piece of pineapple.<br />

They sat silently, eating pineapple.<br />

“Ugh! What an awful lot of mosquitoes!” Hafiz slapped another mosquito.<br />

Anwar tried to remove the buzzing gang of mosquitoes away from his face as<br />

if he were trying to scrape the layer of dirt and moss from a pond. His hunger<br />

pangs had vanished, just a blunt leaden weight lay in his stomach. The raging<br />

pain in his shoulder had also decreased somewhat, but his head still felt heavy<br />

as if someone were working an axe through it, and heavy eyelids kept drooping.<br />

Hafiz had stopped eating and was lost in thought. His shoulder-long hair<br />

had not known the touch of oil for a long time. The moustache and beard on<br />

his tanned face, the slight bulge in his belly which lent a look older than his<br />

years.<br />

What is Hafiz thinking of? His comrades?<br />

Anwar realised that he was sweating profusely. This meant that the fever<br />

was coming down. He called, “Hafiz!”<br />

“Huh! What is it?”<br />

“Couldn’t it be that the other two are alive, just like us?”<br />

“I doubt it,” Hafiz’s quiet and calm voice appeared to come from a great<br />

distance. “Even after I had given order for retreat, I saw them climbing up<br />

with grenades in hand. I have no idea what happened afterwards. I had to<br />

crawl to avoid the onrush of bullets, and finally I fell into the canal.”<br />

Hafiz stopped. He was lost in deep thought again. Suddenly he said, “Could<br />

you try a little? Remember Doctor Amanullah-- the one at whose house we<br />

spent the night when we were put on a mission to Narsingdhi?”<br />

Anwar’s head felt a little lighter. He said, “Of course I remember. It’s really<br />

amazing that such an educated person could spend his entire life in a village.”<br />

Hafiz said, “His house is probably not more than three miles from here.”<br />

Hafiz looked at Anwar, but it was difficult to discern his facial expression in<br />

the hazy light. Hafiz’s shadow covered Anwar and extended to the pineapple<br />

plant.<br />

“Moreover, we have not gone very far from our spot. I have a feeling that<br />

this area might be attacked towards dawn. Because we fled through bushes<br />

and woods, we could not see properly, but there must be villages nearby. After<br />

what took place, I’m sure, the bastards will not sit idle, their witch hunting<br />

will begin soon.”<br />

Hafiz placed his hand on Anwar’s forehead. Right then a booming sound<br />

hit and the earth moved. Hafiz sprang to his feet. Anwar sat up, then with<br />

Hafiz’s support, he stood on his feet. His weak body trembled, he felt lightheaded,<br />

and beyond the dense woods he saw intermittent sparks of red. Ta-tata,<br />

thush, thush, thush, drim, drim, tra-ra ra -- a variety of noises kept coming.<br />

Some timid animal fled through the pineapple grove. Strange birds fluttered<br />

wings and flew over the heads of bamboo trees into the darkness. From a great<br />

distance came the collective shrieking of thousands of people. Mingled with<br />

those shrieks was the constant flow of bullets.<br />

Anwar commented, “It seems like thousands of people.”<br />

“Yes, a large radius has come under attack.”<br />

The inside of his chest kept scraping. The pain in the shoulder would not go<br />

away. His eyes became dazed with staring. Hafiz focused his eyes beyond the<br />

jute fields into the vast space and said absent-mindedly, “I guess we will just<br />

have to take position here and wait.”<br />

Anwar whispered, “No way out.” His words could not be heard.<br />

The place was quite high. Hafiz looked in all directions and asked, “Do you<br />

think you can fire a rifle with one hand?”<br />

“I guess I must.”<br />

“It may be that you will not need to fire at all. No one may come this way at<br />

all. We may just have to wait here quietly all day long. By dusk their mission<br />

will have ended and they will return. Then we can leave.”<br />

Was Hafiz trying to console him? Was the group leader giving moral support<br />

to his comrade? He even punched in a little humour, “We do have plenty of<br />

pineapples, so why worry?”<br />

In the midst of bullet shots and the screaming of people, Hafiz’s words<br />

sounded very odd. Shots were being fired, people were dying, and here were two<br />

freedom fighters who had arms but who could do nothing to give the people any<br />

protection. Wasn’t there any pain, any guilt, any shame on their part?<br />

This story was<br />

titled ‘Aashonno’<br />

in Bangla.<br />

Parveen K Elias<br />

has translated<br />

many stories from<br />

Bengali literature.<br />

9<br />

DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, <strong>September</strong> 7, <strong>2017</strong><br />

ARTS & LETTERS

Short story<br />

10<br />

Anwar knew that in such situations Hafiz could detach himself very easily.<br />

May be he derived his strength from within this wall of detachment. He did<br />

not want his comrades to be affected by the gloom and feel d<strong>amp</strong>ened in<br />

spirit. That is why his words were always morally uplifting.<br />

Anwar lay face down behind a bamboo grove and took position with rifle<br />

in one hand.<br />

Hafiz commented, “Good! I’ll be on the other side. I’ll move as the situation<br />

demands.”<br />

Hafiz took his LMG and took position behind a bamboo grove far left of<br />

Anwar.<br />

Near them was a slope, then a small canal. On the other side of the canal<br />

was a wide and high ridge surrounding the pineapple grove and beyond the<br />

ridge were jute fields.<br />

The pain in the shoulder gnawed intermittently, but it wasn’t severe.<br />

Lightheadedness was the same as before. But at least he could open his eyes<br />

wide and look around. His body remained weak but his eyesight was more<br />

important right now.<br />

The sound of bullets seemed to be coming nearer. The cries of people were<br />

also clearer than before. Lying still and listening to the mass wailing, Anwar<br />

began to remember his home. His eyes closed as familiar faces passed by as on<br />

a screen. A flash penetrated his closed eyelids and he was startled.<br />

Anwar opened his eyes. A fire had started sometime ago. From a distance,<br />

at first a black cloud could be seen twisting and turning towards the sky and<br />

absorbing its blue. Then suddenly red flames would burst into the open space<br />

and redden everything.<br />

From so far off, the above sequence was not evident, but now the horizon<br />

was red with flames. The waves of wailing lashed closer and closer. About half<br />

a mile on both left and right and behind these the bone-penetrating sound of<br />

machine-gun fire. Fields which looked like a dense, dark wall cast in stone<br />

were now softening in the emerging light and branches and leaves could be<br />

discerned.<br />

Sprawled flat on his back, Hafiz was<br />

gasping. One side of his chest was bathed<br />

in blood. A confounded Anwar rushed and<br />

put Hafiz’s head on his lap<br />

The darkness was falling off silently from the leaves, from the branches as<br />

if the surrounding trees were sucking in the juice of darkness and transporting<br />

it to their roots.<br />

As the darkness was receding slowly, a single, detached and fearful cry<br />

gradually came nearer and fell over in the fields ahead, shaking the heads of<br />

jute-plants violently.<br />

Behind this was the sound of heavy boots, and crazy, insane male laughter.<br />

Then frenzied shrieks of a woman like that of an animal that had suddenly<br />

been trapped. Then an abraded, hushed groaning. The jute plants over a wide<br />

area kept moving. The whirlpool from under kept them twisting and turning<br />

and they kept bending down. There was a lustful, saliva-drooling male voice<br />

followed by a piercing shriek. The shriek was distinctive. It was as if some<br />

one had lost her core of being and was completely shattered. At intervals<br />

came trembling groans as if some one were being assaulted. The jute-plants<br />

were uprooted as by a severe earthquake in which the earth had burst open.<br />

Suddenly a cyclone seemed to move through the field. A young girl, totally<br />

naked, emerged followed by a pursuer, a big, helmeted man like a lion in<br />

pursuit of a prey which had just escaped him. One could not see their faces,<br />

just their silhouettes.<br />

A loud ringing sound rang through the pineapple grove. The pursuer with<br />

hands held out towards the naked girl in unfulfilled lust, gave out a strange<br />

cry and fell backwards in the field. The alarmed girl looked back at the fallen<br />

soldier for a moment and vanished rapidly into the jute field.<br />

Beyond the wide ridge, at the mouth of the narrow ridge dividing the fields,<br />

one could glimpse those two only for a moment. Within seconds each moved<br />

to one side of the narrow ridge and disappeared into the field, crawling on<br />

their stomach and blending into the earth. They were shielded by the wide<br />

ridge in front of them. Protecting themselves with drawn helmets, they kept<br />

on firing their LMGs.<br />

The entire episode of the two soldiers coming forward, jumping down<br />

to take positions, and their firing of machine-guns all took place with such<br />

unpredictable speed that Hafiz was totally taken aback.<br />

Ah, if only the pineapple grove extended a little further! Then this spot<br />

would be directly in line with the narrow ridge and here would be the ideal<br />

spot to shoot from. It would be easy to shoot them before they reached the<br />

wide ridge.<br />

Now it would not be easy to overcome these two skilled LMG holders<br />

who had clung to the earth and taken positions. These two would be a real<br />

pain. The way they were brush-firing 303 in hand, it could be fatal for injured<br />

Anwar. It would be difficult to do anything from here even with an LMG. The<br />

bullets kept flying near the roots of bamboo trees in front of Anwar.<br />

Hafiz crawled closer to Anwar and said, “You must go back!”<br />

Anwar moved further back into the pineapple grove.<br />

Hafiz took out a grenade from his pocket, started the LMG5 rapidly, took off<br />

the pin, and rising up a little, charged.<br />

The grenade burst with a great noise. The earth near the ridge flew upwards<br />

like a fountain. A shriek could be heard from there.<br />

There was a short interval, but the rounds of reply from below began once<br />

more. The two hiding in the pineapple grove realised that now only one LMG<br />

was functioning. The other one had stopped.<br />

Hafiz took out another grenade from his pocket and prepared to charge<br />

again. But before he could do so, he fell down groaning in pain.<br />

Anwar dragged himself closer and closer. Hafiz bit his lips and said in<br />

gasping voice, “I’m all right! Charge! Hurry!” As Anwar took the grenade from<br />

Hafiz and prepared to charge, he saw the soldier retreating with his arms.<br />

Anwar picked up his rifle. He jumped up behind the bushes, placed the butt<br />

under his arm, bit his lips and pressed the trigger desperately. Resting his back<br />

against a bamboo tree he withstood the jerking and fired another round.<br />

The figure which had almost vanished into the jute-field sprang up,<br />

convulsed like a slaughtered chicken and became still.<br />

The tense alertness now gave way and Anwar felt he would collapse. The<br />

rifle lay heavily laden in his arms. He sat down with the rifle, leaned against<br />

a bamboo tree, closed his eyes and breathed in and out. Then he leapt up<br />

suddenly and came back to Hafiz.<br />

Sprawled flat on his back, Hafiz was gasping. One side of his chest was<br />

bathed in blood. A confounded Anwar rushed and put Hafiz’s head on his lap.<br />

He called, “Hafiz!”<br />

Hafiz looked at him once with hazy eyes, his lips moving, but the words<br />

could not be understood. Anwar put his hands on Hafiz’s chest, bent down<br />

and called again, “Ha fee z!”<br />

Hafiz’ eyelids were closed. He saw a dense wide expanse of greenery. A<br />

large striped tiger waved its tail and walked through with a calm majestic<br />

tread.<br />

A happy serene smile came across Hafiz’s face as he watched the tiger.<br />

When Anwar gently laid Hafiz’s head on the ground, that smile remained on<br />

his face.<br />

Anwar could not bear to look again at that face. He just looked down once<br />

at the sprawled body, then picked up the LMG and threw it deep into the<br />

pineapple grove. With his own rifle hanging by the shoulder, he walked down<br />

the slope into the jute-fields. He ran and threw all three LMGs into the jutefields.<br />

Then he himself vanished into the dense vegetation.<br />

He must make sure to take out the bullet in his shoulder as soon as<br />

possible.•<br />

ARTS & LETTERS DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, <strong>September</strong> 7, <strong>2017</strong>

1947<br />

Kitabistan:<br />

A forgotten tale of partition<br />

• Mofidul Hoque<br />

Sometime in 2007, at a seminar at Independent University in Dhaka,<br />

when a paper titled “Kitabistan: Remembering a pre-partition<br />

publisher” was being read, most people in the audience shifted in<br />

their seats. The presenter, Ali A Rehman, an English professor of<br />

Rajshahi University, grabbed all the attention as he read out in palatable prose<br />

the success story of a publishing house, Kitabistan, and its untimely tragic<br />

demise. His personal account left a permanent mark on my mind though I<br />

never got around to knowing more about this. We get carried away by the<br />

tide of life, and we get busy. Ultimately the wonderful story of Kitabistan got<br />

buried in my mind.<br />

Nearly a decade later, while reading The Daily Star sometime in 2016, I came<br />

across a review of a book titled Literature, History and Culture: Writings in<br />

Honour of Professor Ali Arifur Rehman. A photo of the professor was attached<br />

to the review and under the photo was brightly written the dates of his birth<br />

and death: August 29, 1950 – March 13, 2013. I soon realised that the writer<br />

of that paper on Kitabistan and this Mr Ali Rehman were the same person.<br />

How I’d desired to meet with him and talk about Kitabistan in detail! I had<br />

not taken any initiative, though. Now<br />

he’s beyond our reach, so there’s no way<br />

I can fulfil my desire. Even then, I think I<br />

should do my part in recounting the story<br />

of Kitabistan to readers because this is<br />

not just a woeful story of a publishing<br />

house; this is also a story that helps us<br />

understand the price at which partition<br />

came – the pangs and traumas that it<br />

stands for.<br />

Kitabistan was a book publication<br />

house founded in 1930 in Allahabad,<br />

India by Ali A Rehman’s father Mutatz<br />

Obaidur Rehman and Uncle Muktadir<br />

Kolimur Rehman. In ten years, it rose to<br />

fame surprisingly all over India and even<br />

set up an office in London. But the next<br />

decade came with a massive set-back<br />

that ultimately led to its disintegration<br />

and the displacement of Rehman’s<br />

family. In 1949 the Indian government<br />

marked the publication house as<br />

evacuee property, citing as reason that<br />

one of its publishers (Muktadir Kolimur<br />

Rehman) had migrated to West Pakistan.<br />

Obaidur Rehman stayed back with<br />

his family and fought the legal battle<br />

against the government but the house<br />

received another blow in 1955 when the<br />

government auctioned it off. A heartbroken Obaidur Rehman moved to East<br />

Pakistan along with his family for good. Ali A Rehman studied in Rajshahi.<br />

Later he obtained a PhD from British Columbia University in Canada. Upon<br />

his return from Canada, he took up a teaching position at Rajshahi University.<br />

The title page of this book shows Kitabistan’s name as the publisher. The photo was collected from the internet<br />

It was much later in his life that Ali came to know about<br />

his father’s publication house and became involved in<br />

exploring its glorious past. With the death of his father<br />

and without any record of the books, it proved a daunting<br />

task for Ali to assemble the titles published by Kitabistan.<br />

His relentless effort bore fruit and he could come up with<br />

a list of nearly sixty titles. Mostly he recorded the books<br />

published between 1933 and 1949.<br />

From the list, it became evident how fast Kitabistan<br />

attained success and even set up an office in London with<br />

further plans. Kitabistan’s target was to create an Indian<br />

book market in England. To do so, works of Indian writers<br />

needed to be published from Britain and vice versa. The<br />

vision of the publisher-brothers, no doubt, was far ahead<br />

of their time, incomprehensible to the mass people.<br />

The list of publications by Kitabistan would surprise<br />

anyone. It featured unique titles by renowned writers as<br />

well as emerging ones, by social workers and philosophers.<br />

Sarojini Naidu, Jawaharlal Nehru, Subhas Chandra Bose,<br />

historian Ramesh Chandra Dutt and poet Toru Dutt, to<br />

name just a few. The Rehman brothers had a reputation<br />

for encouraging eminent personalities to write on their<br />

respective fields. They took the responsibility of printing<br />

them as well. This type of venture resulted in books like<br />

Prajesh Banerjea’s Folk Dance of India (1944), GAC Pande’s<br />

Art of Kothakoli (1943), and Premkumar’s The Language of<br />

Kothakoli: A Guide to Madraz (1948).<br />

In 1930, Kitabistan gained the right to publish the<br />

second edition of Jawaharlal Nehru’s A Father’s <strong>Letters</strong> to his Daughter. Later<br />

they published Nehru’s Where are you? (1939), China, Spain and the War:<br />

Essays and Writings, and Glimpses of World History.<br />

See page 13<br />

11<br />

DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, <strong>September</strong> 7, <strong>2017</strong><br />

ARTS & LETTERS

1947<br />

Partition in Banglades<br />

Mofidul Hoque is a<br />

co-founder and one<br />

of eight Trustees<br />

of the Liberation<br />

War Museum.<br />

He is a writer,<br />

researcher and<br />

publisher based in<br />

Dhaka. His books<br />

include Deshbagh,<br />

S<strong>amp</strong>radayikata<br />

Ebong S<strong>amp</strong>reetir<br />

Sadhana<br />

(University Press<br />

Limited, 2012).<br />

12<br />

The Slaughter by Somnath Hore<br />

• Mofidul Hoque<br />

Many aspects of the partition of Punjab and Bengal cannot be<br />

explained with sound arguments, at least the arguments put<br />

forward by politicians – be they British rulers or leaders of the<br />

Congress and the Muslim League – turned out to be hollow<br />

and absurd with the benefit of hindsight, though they might have appeared<br />

to be substantial during the turbulent days of 1947. Irrespective of how the<br />

politicians viewed or manipulated partition, the way writers have examined<br />

it is illuminating and does not underlie any motive of<br />

gaining some immediate advantage. Which is precisely<br />

why Pakistani poet Fayez Ahmed Fayez thought this<br />

was not the dawn of independence (in 1947) that we had<br />

been waiting for; this dawn was marked with palls of<br />

darkness. Saadat Hasan Manto, with a heart torn apart<br />

by the wounds of communal violence during partition,<br />

had written some formidable short stories on the<br />

subject. In his story “Tobatek Singh,” people suddenly<br />

realise that though they’ve distributed assets of all<br />

kinds between the two countries, they could not decide<br />

on how to divide the inmates of a mental asylum. One of<br />

the inmates is called Tobatek Singh whose inconsistent<br />

utterances do not reveal much about the country he<br />

belongs to. In the end, however, his dirty, insane curses<br />

make sense while the cold arguments of the distributors<br />

sound insane and absurd …<br />

Recently a book has been published from Islamabad,<br />

compiling articles from writers of both parts of Punjab.<br />

The book is called Operation without Anaesthesia; it<br />

is so because the dissection was done even before<br />

anaesthesia could be applied and the terrible pain that it caused was vivid in all<br />

the articles in the book ... The magnitue of violence in the partition of Bengal<br />

was perhaps not as big as it was in Punjab, though it is not justified to compare<br />

riots (involving bloodshed) on a bigger or smaller scale. But the wounds of<br />

Bengal’s partition are still festering and the bleeding has not stopped yet, and<br />

the agony emanating from those wounds still strikes us, assuming new forms<br />

of violence or repeating old ones on the religious minorities in Bangladesh.<br />

After the riot in Kolkata in mid-August, 1946, and the subsequent ones in<br />

Noakhali and Bihar, politicians had thought that partition would put an end to<br />

the bloodletting. They were proved wrong. Furthermore, partition came with<br />

an entirely new phenomenon that none could have predicted: Thousands<br />

and thousands of people were uprooted from their land overnight. A sea of<br />

people had left their homes for unknown destinations. The refugee crisis<br />

overwhelmed and crippled both countries. One of the biggest refugee crises<br />

of the 20th century had thus set in.<br />

Partition of Punjab deeply affected writers in India and Pakistan. Saadat<br />

Hasan Manto, Krishan Chander, Khuswant Singh, Kamleshwar, Ismat<br />

Chughtai, Khaja Ahmed Abbas, Qurratulain Hyder, Ajeet Cour, among others,<br />

have written many famous works of fiction about partition. In spite of her bias<br />