JK PANORAMA SEPTEMBER ISSUE

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

the military junta that used to rule Myanmar, and<br />

they have suffered decades of repression under the<br />

country's Buddhist majority, including killings and<br />

mass rape, according to the United Nations. A new<br />

armed resistance is giving the military more<br />

reasons to oppress them.<br />

But the past week's exodus of civilians caught in<br />

the middle, which the United Nations said had<br />

reached nearly 76,000 on Saturday, dwarfs<br />

previous outflows of refugees to Bangladesh in<br />

such a short time period. Friday's influx alone was<br />

the single largest movement of Rohingya here in<br />

more than a generation, according to the United<br />

Nations office in Dhaka.<br />

Person after person along the trail into Bangladesh<br />

told of how the security forces cordoned off<br />

Rohingya villages as the fire rained down, and<br />

then shot and stabbed civilians. Children were not<br />

exempt.<br />

Mizanur Rahman recalled how on Aug. 25 he had<br />

been working in a rice paddy in his village, known<br />

in Rohingya as Ton Bazar, in Buthidaung<br />

Township in Myanmar, when helicopters roared<br />

into the sky above him.<br />

“Immediately, I had fear in my heart,” he said. His<br />

wife came running out of their house with their<br />

son, less than a month old.<br />

They escaped to a nearby forest and watched as<br />

the choppers' weapons engulfed the village in<br />

flames. Myanmar security forces descended, and<br />

the sound of gunfire reached the forest.<br />

Mr. Rahman's extended family fled the next day,<br />

but not before seeing his brother's body lying on<br />

the ground, along with seven others. Three days<br />

later, as they climbed a hill near the border with<br />

Bangladesh, Mr. Rahman's mother was shot dead<br />

by a Myanmar border guard.<br />

“Now we are supposed to be safe in Bangladesh,<br />

but I do not feel safe,” Mr. Rahman said, as he<br />

wandered through a market in the Kutupalong<br />

refugee camp, with no money in his pocket.<br />

What the survivors are fleeing into is no haven.<br />

Bangladesh is itself poor, overcrowded and<br />

waterlogged, and has been reluctant to take on<br />

more displaced Rohingya. Around 400,000 already<br />

lived here before the exodus, according to<br />

government figures.<br />

An urgent humanitarian disaster is brewing here in<br />

a country hard-pressed to feed itself, much less a<br />

new influx of refugees that one Bangladeshi<br />

official estimated could soon surpass 100,000<br />

people.<br />

For now, the Border Guard Bangladesh is mostly<br />

turning a blind eye and allowing the Rohingya to<br />

stream across the border.<br />

But there is little help for them here, as they push<br />

on in hopes of reaching some of the grim refugee<br />

camps further in.<br />

n an open letter to Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi, nearly a<br />

dozen of her fellow Nobel Peace Prize laureates<br />

labeled last October's military offensive “a human<br />

tragedy amounting to ethnic cleansing and crimes<br />

against humanity.”<br />

“Some international experts have warned of the<br />

potential for genocide,” said the letter, signed by<br />

Desmond Tutu and Malala Yousafzai, among<br />

others. “It has all the hallmarks of recent past<br />

tragedies: Rwanda, Darfur, Bosnia, Kosovo.”<br />

Standing at the edge of a muddy path to Rezu<br />

Amtali, after a five-day journey with only a few<br />

handfuls of ruined rice to sustain them, a 6-yearold<br />

girl named Roufaja tugged at her mother's<br />

sleeve. “Are we in Bangladesh yet?” she asked.<br />

Her mother, Fatima Khatun — whose husband was<br />

presumed dead and sister had been raped by the<br />

security forces who had besieged their village —<br />

replied that they were.<br />

“What are we going to do now?” her daughter<br />

asked, pulling at her sleeve again. “I'm hungry.”<br />

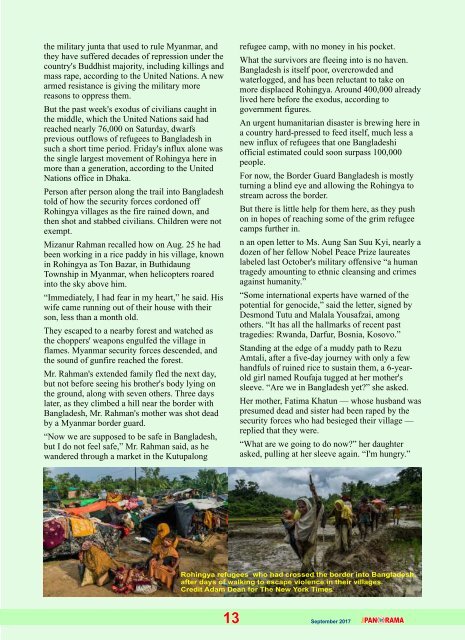

Rohingya refugees who had crossed the border into Bangladesh,<br />

after days of walking to escape violence in their villages.<br />

Credit Adam Dean for The New York Times<br />

13 September 2017 <strong>JK</strong>