Scythian Culture - Preservation of The Frozen Tombs of The Altai Mountains (UNESCO)

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

PRESERVATION OF THE FROZEN TOMBS OF THE ALTAI MOUNTAINS<br />

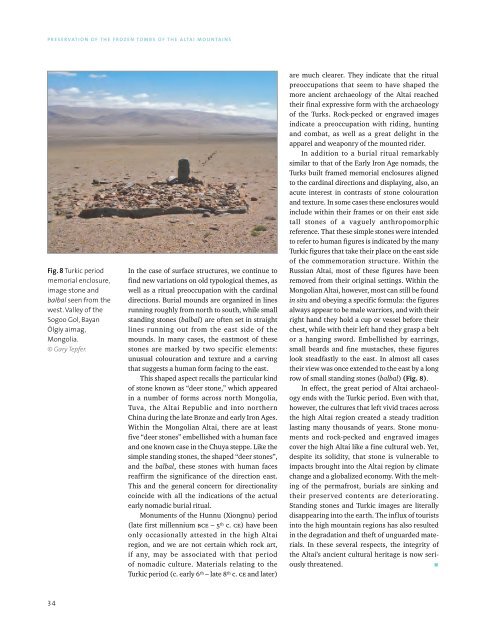

Fig. 8 Turkic period<br />

memorial enclosure,<br />

image stone and<br />

balbal seen from the<br />

west. Valley <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Sogoo Gol, Bayan<br />

Ölgiy aimag,<br />

Mongolia.<br />

© Gary Tepfer.<br />

In the case <strong>of</strong> surface structures, we continue to<br />

find new variations on old typological themes, as<br />

well as a ritual preoccupation with the cardinal<br />

directions. Burial mounds are organized in lines<br />

running roughly from north to south, while small<br />

standing stones (balbal) are <strong>of</strong>ten set in straight<br />

lines running out from the east side <strong>of</strong> the<br />

mounds. In many cases, the eastmost <strong>of</strong> these<br />

stones are marked by two specific elements:<br />

unusual colouration and texture and a carving<br />

that suggests a human form facing to the east.<br />

This shaped aspect recalls the particular kind<br />

<strong>of</strong> stone known as “deer stone,” which appeared<br />

in a number <strong>of</strong> forms across north Mongolia,<br />

Tuva, the <strong>Altai</strong> Republic and into northern<br />

China during the late Bronze and early Iron Ages.<br />

Within the Mongolian <strong>Altai</strong>, there are at least<br />

five “deer stones” embellished with a human face<br />

and one known case in the Chuya steppe. Like the<br />

simple standing stones, the shaped “deer stones”,<br />

and the balbal, these stones with human faces<br />

reaffirm the significance <strong>of</strong> the direction east.<br />

This and the general concern for directionality<br />

coincide with all the indications <strong>of</strong> the actual<br />

early nomadic burial ritual.<br />

Monuments <strong>of</strong> the Hunnu (Xiongnu) period<br />

(late first millennium bce – 5 th c. ce) have been<br />

only occasionally attested in the high <strong>Altai</strong><br />

region, and we are not certain which rock art,<br />

if any, may be associated with that period<br />

<strong>of</strong> nomadic culture. Materials relating to the<br />

Turkic period (c. early 6 th – late 8 th c. ce and later)<br />

are much clearer. <strong>The</strong>y indicate that the ritual<br />

preoccupations that seem to have shaped the<br />

more ancient archaeology <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Altai</strong> reached<br />

their final expressive form with the archaeology<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Turks. Rock-pecked or engraved images<br />

indicate a preoccupation with riding, hunting<br />

and combat, as well as a great delight in the<br />

apparel and weaponry <strong>of</strong> the mounted rider.<br />

In addition to a burial ritual remarkably<br />

similar to that <strong>of</strong> the Early Iron Age nomads, the<br />

Turks built framed memorial enclosures aligned<br />

to the cardinal directions and displaying, also, an<br />

acute interest in contrasts <strong>of</strong> stone colouration<br />

and texture. In some cases these enclosures would<br />

include within their frames or on their east side<br />

tall stones <strong>of</strong> a vaguely anthropomorphic<br />

reference. That these simple stones were intended<br />

to refer to human figures is indicated by the many<br />

Turkic figures that take their place on the east side<br />

<strong>of</strong> the commemoration structure. Within the<br />

Russian <strong>Altai</strong>, most <strong>of</strong> these figures have been<br />

removed from their original settings. Within the<br />

Mongolian <strong>Altai</strong>, however, most can still be found<br />

in situ and obeying a specific formula: the figures<br />

always appear to be male warriors, and with their<br />

right hand they hold a cup or vessel before their<br />

chest, while with their left hand they grasp a belt<br />

or a hanging sword. Embellished by earrings,<br />

small beards and fine mustaches, these figures<br />

look steadfastly to the east. In almost all cases<br />

their view was once extended to the east by a long<br />

row <strong>of</strong> small standing stones (balbal) (Fig. 8).<br />

In effect, the great period <strong>of</strong> <strong>Altai</strong> archaeology<br />

ends with the Turkic period. Even with that,<br />

however, the cultures that left vivid traces across<br />

the high <strong>Altai</strong> region created a steady tradition<br />

lasting many thousands <strong>of</strong> years. Stone monuments<br />

and rock-pecked and engraved images<br />

cover the high <strong>Altai</strong> like a fine cultural web. Yet,<br />

despite its solidity, that stone is vulnerable to<br />

impacts brought into the <strong>Altai</strong> region by climate<br />

change and a globalized economy. With the melting<br />

<strong>of</strong> the permafrost, burials are sinking and<br />

their preserved contents are deteriorating.<br />

Standing stones and Turkic images are literally<br />

disappearing into the earth. <strong>The</strong> influx <strong>of</strong> tourists<br />

into the high mountain regions has also resulted<br />

in the degradation and theft <strong>of</strong> unguarded materials.<br />

In these several respects, the integrity <strong>of</strong><br />

the <strong>Altai</strong>’s ancient cultural heritage is now seriously<br />

threatened.<br />

34