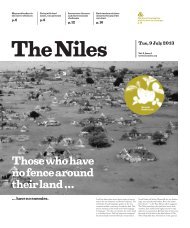

When two elephants fight...

...it is the grass that suffers. On the 9 July 2012 the two youngest countries in the world celebrate their first birthdays. To mark the occasion, journalists from Sudan and South Sudan came together to report on the development of both nations in the second edition of The Niles. The proverb about the two elephants, which is popular in both countries, has become a fitting leitmotif. How much the grass actually suffers, how the elephants are affected and what that has to do with relationships between people, are all explored in the collection of stories, pictures and songs from Sudan and South Sudan.

...it is the grass that suffers. On the 9 July 2012 the two youngest countries in the world celebrate their first birthdays. To mark the occasion, journalists from Sudan and South Sudan came together to report on the development of both nations in the second edition of The Niles. The proverb about the two elephants, which is popular in both countries, has become a fitting leitmotif. How much the grass actually suffers, how the elephants are affected and what that has to do with relationships between people, are all explored in the collection of stories, pictures and songs from Sudan and South Sudan.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

16 The Niles | Media<br />

“We <strong>fight</strong> for the<br />

impossible”<br />

Mahjoub Mohamed Salih is the “grey eminence” of Sudanese<br />

journalism and editor-in-chief of the newspaper Al-Ayyam. Here<br />

he explains the strength of the press in Sudan, the lack of investigative<br />

journalism and the secret of writing critically about the<br />

government without being arrested.<br />

Q: Mr. Salih, you are the most experienced editor-in-chief in<br />

Sudan and have been working for more than 70 years as a journalist.<br />

Do you ever regret your choice of profession?<br />

A: At the beginning, I didn’t consider journalism as a profession.<br />

Those days, Sudan was a relict type of colony under Anglo-Egyptian<br />

rule and under colonial rule, the press is an advocacy tool. I<br />

come from a working class family and wrote my first article at the<br />

age of 12. I later joined a Marxist group and became one of the<br />

leaders of the student movement.<br />

Q: So your professional aspirations were initially politically motivated?<br />

A: We wanted to get across to the people our wishes for the future.<br />

Journalism to me was a way to express my political views specifically<br />

for liberating the country from foreign rule. So that’s why I became<br />

a journalist.<br />

Q: Expressing political views under colonial rule – this sounds like<br />

a mission impossible.<br />

A: Several people were imprisoned. I went to jail because I took<br />

part in demonstrations but also because I was a junior reporter. At<br />

that time, it didn’t take much to get incarcerated.<br />

Q: One must not even go back to the colonial era. This year,<br />

the Sudanese press reported the temporary suspension of the dailies<br />

Alwan, Al Tayar and even Akhir Lahza. Many journalists have<br />

been detained. Isn’t working in this profession just like tilting<br />

at windmills?<br />

A: Absolutely not. The strength of the press in Sudan is that<br />

it affects the public opinion, the discourse, and those who make<br />

the decisions – despite confiscations and political repression. The<br />

majority of Sudanese are illiterate and they’d rather listen to the<br />

radio. But for the elite, the press is a major point of reference. And<br />

as such, it is looked upon by the ordinary man as a very important<br />

organ in his hands, reflecting his views and educating him.<br />

Q: Balance and education – is this also the philosophy of your<br />

newspaper Al Ayaam?<br />

A: Definitely. I think what makes our newspaper special is the<br />

different types of views people find in it. We try to address issues<br />

in depth and in a very open manner. I think people who read us<br />

look for that. And I believe that this was one of the privileges of Al<br />

Ayaam since it started in 1953. We are broken, but outspoken and<br />

very good. This combination is important.<br />

Q: Is it really as easy as that? After all, Al Ayaam was closed<br />

down by the authorities from 1989 to 2000 and then again in 2003<br />

for a couple of weeks.<br />

A: I was over 60 years old by that time, so I relaxed a bit. No,<br />

seriously speaking, I think good journalism needs to be credible.<br />

You have to cover all events and views, even those you don’t like.<br />

But you are free to express your views decently and correctly, whatever<br />

they are. You can go against the government 100 percent, but<br />

you can’t accuse persons for things they haven’t done. That’s why we<br />

need investigative journalism in Sudan, more than ever before.<br />

Q: But investigative journalism implicates the unveiling of a<br />

hidden truth, which leads to the question of access to information.<br />

A: Freedom of information is definitely lacking in the shape<br />

of the Sudanese legal framework. We need a law that demands that<br />

everyone who runs an institution, private or governmental, must<br />

make information available. We suggested a law to this government<br />

five years ago and they didn’t do it. We don’t expect them to do it.<br />

We know it is impossible, but we <strong>fight</strong> for the impossible.<br />

Q: Meaning?<br />

A: Al Sudani recently published an article about a government<br />

official who broke the rules through his business links. The government<br />

issued orders to prevent us from commenting on this affair<br />

because the guy is under investigation. We continue <strong>fight</strong>ing for our<br />

right to report on this case. Being under investigation should not<br />

mean we stop publishing. So it is possible to have investigative journalism,<br />

but I would say that it is difficult.<br />

Q: Looking at the Sudanese newspaper market, the variety of<br />

publications seems to underpin your argument.<br />

A: This is not a unique phenomenon for Sudan. <strong>When</strong>ever you<br />

have a dictatorial regime, the society is closed down. But as soon as<br />

it begins to open up a little, the right to express yourself becomes<br />

predominant, because people have been kept silent for such a long<br />

time. This happened in Eastern Europe, after the fall of the communist<br />

system. This happened in Iraq after Saddam Hussein as well.<br />

Q: So, going back to my initial question: Have you never thought<br />

of giving up and becoming a doctor or an engineer instead?<br />

A: I decided to stay in journalism with all of the ups and downs. It<br />

has never been lucrative, it is even a poverty profession, but I persist.<br />

”<br />

Mahjoub Mohamed Salih is the editor-in-chief of Sudan’s second<br />

oldest, independent and liberal daily newspaper, Al-Ayyam. He was<br />

born in 1928 and his first articles were published in 1940 in the pupil’s<br />

section of the daily newspaper Sawt Al-Sudan. After studying at<br />

Gordon College, he founded Al-Ayaam in 1953, a daily newspaper<br />

that was shut down twice by the Sudanese authorities during the<br />

1960s, leading him to become an editor for the English newspaper<br />

Morning News and work as a correspondent. During the Nimeiry<br />

Era, (1969 – 1985), he was a stringer for newspapers outside of Sudan.<br />

Al-Ayaam was closed from 1989 to 2000 and again from November<br />

2003 until January 2004 for covering the war in Darfur. Salih was<br />

imprisoned several times for his coverage of critical topics<br />

“I’m not radical,<br />

I’m flexible”<br />

by Waakhe Simon Wudu<br />

A year since South Sudan gained its independence, journalists and<br />

rights activists still express concern about inadequate press freedom,<br />

even as officials underscore the role of media in building a strong,<br />

democratic society. An interview with one of South Sudan’s most<br />

outspoken independent journalists and publishers, Nhial Bol,<br />

editor-in-chief of the daily, The Citizen.<br />

Q: Mr. Bol, recently Atem Yaak Atem, the Deputy Minister of<br />

Information and Broadcasting, said: “One of the important aspects<br />

of the struggle was to establish a better society where there is justice,<br />

equality and freedom of expression.” Has press freedom improved<br />

since independence?<br />

A: If you have observed the cases of journalists who have been<br />

beaten, arrested, harassed and humiliated since independence, it is<br />

clear that we are heading for the worst. We cannot say that there<br />

is press freedom when we do not have a legal instrument or a law<br />

that regulates it.<br />

Q: The South Sudanese Information Minister, Barnaba Marial<br />

Benjamin, described the media environment in South Sudan as<br />

“hostile and dangerous,” due to the absence of the legal framework<br />

you mentioned. The media bills have been passed by the National<br />

Council of Ministers and await legislation by the National Parliament.<br />

Why did the president order the withdrawal of the bills?<br />

A: The intention was to allow stakeholders to participate. But until<br />

today, the stakeholders, especially the media, say they have not been<br />

consulted and their views have not been taken into consideration.<br />

Q: But the Minister of Information and Broadcasting said during<br />

the commemoration of this year’s World Press Day that these laws<br />

were withdrawn from parliament at the request of some media<br />

activists and that consultations about the laws were being held?<br />

A: As far as I know, the directors of the Ministry of Information<br />

and Broadcasting and the directors of the Ministry of Telecommunication<br />

and Postal Services were the ones who discussed our draft<br />

bills and we were not consulted. I protested this. Even if these laws<br />

are proper and up to international standards, press freedom will<br />

be limited. It should have been a package of bills that relate to civil<br />

rights in general, but media bills without civil rights laws will<br />

prolong the current crisis.<br />

Q: What are the most pressing challenges that the independent<br />

media is facing as a result of the current situation?<br />

A: The security people have been calling us about stories they do<br />

not want published— that we should not touch the president and his<br />

personal life for example. We invite them to sit down and interact<br />

but they do not turn up, so they are exercising indirect censorship.<br />

Q: South Sudan has media umbrella institutions, such as the<br />

Association for Media Development in South Sudan (AMDISS)